Abstract

Heilongjiang Province, a key ecological barrier in Northeast China, is crucial for regional ecosystem stability. Previous vegetation index research in this region primarily focused on annual or growing-season scales, without comprehensive comparisons of seasonal and interannual variations. This study addresses this gap by analyzing spatiotemporal vegetation dynamics and their driving forces in Heilongjiang Province using MODIS data (2000–2021). The findings reveal: (1) Analysis of MODIS-derived Fractional Vegetation Cover (FVC) from 2000 to 2021 revealed decreasing trends in spring, autumn, and winter, alongside an increasing summer trend. Spatially, FVC was higher in the northwest, central, and southeast regions, indicating significant heterogeneity. (2) Theil-Sen trend and Hurst exponent analyses indicated a declining annual FVC trend in 61.8% of the area, with 54.7% projected for continued future decline. A centroid shift model showed an overall westward FVC movement, except in spring. Coefficient of variation analysis demonstrated highest FVC stability in summer and lowest in winter. The global Moran’s I index indicates that FVC exhibits a highly spatially concentrated distribution. Local Moran’s I analysis primarily reveals two clustering patterns: “high-high” and “low-low” aggregations.(3) Random Forest SHAP analysis identified altitude, land cover type, evapotranspiration (ET), and slope as primary factors influencing FVC. Furthermore. The geographical detector analysis demonstrates that the interactions among factors strengthen their overall impact on FVC.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Vegetationis a crucial component of terrestrial ecosystems, playing a vital role in surface energy exchange, biogeochemical cycling processes, and the hydrological cycle1. It connects the atmosphere, hydrosphere, and pedosphere, facilitates the flow of matter and energy, and supports biodiversity by providing food, habitat, and vital ecosystem services such as water conservation and climate regulation. Due to its high sensitivity to environmental changes, vegetation is widely seen as a key indicator of ecosystem dynamics. Shifts in ecosystem structure and function are often first reflected in changes in vegetation type and spatial distribution. Establishing effective monitoring indicators is therefore essential for ecological evaluation and management. Therefore, establishing effective monitoring indicators is essential for ecological evaluation and management. Among various vegetation indicators, fractional vegetation cover (FVC), defined as the proportion of ground covered by the vertical projection of vegetation elements (e.g., leaves, stems, branches), is widely used to monitor vegetation conditions and ecological change due to its direct reflection of vegetation spatial distribution and dynamics2. Traditional field-based methods yield high accuracy but are constrained by time, labor, and limited spatial coverage. In contrast, remote sensing provides efficient, large-scale, and dynamic monitoring of FVC3, making it an essential tool in vegetation observation and analysis.

Against the backdrop of global climate change, Heilongjiang Province, as a key ecological security barrier in northern China, is characterized by a typical cold-temperate climate and complex geomorphological conditions, and exhibits high sensitivity and responsiveness to climatic variations. Existing studies have examined the spatiotemporal variations of multiple vegetation indicators and ecosystem productivity in Heilongjiang from various perspectives, along with their associated driving factors.For example Wei et al. found higher NDVI values (0.7–0.9) across Northeast China from 2001 to 2020, with precipitation as the primary influencing factor4. Zhao et al. demonstrated a significant upward trend in Heilongjiang’s FVC between 1990 and 2020, primarily influenced by anthropogenic activities5. In contrast, Hu et al. revealed a decline in FVC in the Heilongjiang River Basin from 2000 to 2020, mainly influenced by precipitation and temperature6. Zhang et al. identified an increasing trend in NEP from 2010 to 2020, with altitude and slope as the main factors affecting it7. Xi et al. found that NPP showed an increasing trend from 2001 to 2021, with land use having the greatest impact on NPP8. Liu et al. found that Heilongjiang Province has experienced significant urban expansion and agricultural intensification, which may lead to fragmentation or degradation of natural vegetation9. These studies have laid a solid foundation for understanding vegetation dynamics and their driving mechanisms in Heilongjiang Province, providing both theoretical and empirical foundations. Specifically, different land use types shape the spatial distribution of vegetation indices by altering surface properties and ecological processes, while climate change influences vegetation growth through multiple mechanisms: temperature affects photosynthetic rates, growing season length, and species composition, while precipitation controls water availability for plant growth and nutrient cycling processes. However, these studies have focused primarily on annual or growing season scales, relying mainly on traditional spatial statistics and linear methods, with relatively limited attention paid to the spatially heterogeneous and nonlinear effects of individual environmental and anthropogenic factors across different seasons. To address this limitation, this study introduces an integrated approach that combines a machine learning SHAP method and the interaction detection module of the Geodetector. The SHAP method is used to quantify the single factor contributions of environmental and anthropogenic drivers and to capture their spatial heterogeneity and nonlinear effects across different seasons10,11,12, while the Geodetector interaction module is applied to assess the synergistic effects between these drivers. In this study, MODIS NDVI time series data (2000–2021) were selected due to their strong temporal continuity and broad spatial coverage, making them ideal for long-term monitoring of vegetation dynamics across large areas, with numerous studies confirming the reliability and effectiveness of MODIS data for large-scale vegetation analyses13,14,15,16.

This study aims to: (1) quantitatively assess the seasonal and interannual spatiotemporal characteristics of FVC in Heilongjiang Province from 2000 to 2021; (2) identify significant areas of FVC change in different seasons, detect spatial clustering patterns through autocorrelation analysis, and predict future evolutionary trends through advanced statistical methods. (3) determine the relative importance and interactive effects of environmental and anthropogenic drivers influencing FVC dynamics in different seasons. This research contributes to evaluating and predicting vegetation cover dynamics and their environmental responses in Heilongjiang Province, providing reliable scientific evidence for regional adaptive ecological management.

Materials and methods

Study area

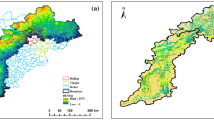

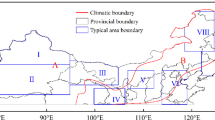

Heilongjiang Province (43°26′–53°33′ N, 121°11′–135°05′ E) is located in northeastern China, bordered by Russia to the east and north, Inner Mongolia to the west, and Jilin Province to the south (Fig. 1). It is the northernmost and easternmost provincial-level administrative region in China, with a land area of approximately 460,000 km². The province’s geographical features are described as “five mountains, one water, one grassland, and three parts field.” The terrain is higher in the northwest, north, and southeast, and lower in the northeast and southwest, consisting of mountains, plateaus, plains, and bodies of water. Heilongjiang spans four major river systems: the Heilong River, the Wusuli River, the Songhua River, and the Suifen River. It has a cold temperate to temperate continental monsoon climate with significant regional climatic differences. The province can be divided from south to north into a mid-temperature zone and a cold-temperature zone, and from east to west into humid, semi-humid, and semi-arid zones based on dryness indices. Annual precipitation ranges from 400 to 650 mm. Heilongjiang Province boasts the largest forested area, total forest stock, and timber output in China, making it an important national forest area and the largest timber production base in the country.

Geographic location map and Dem map of Heilongjiang. Map generated using ArcGIS version10.8 (https://www.esri.com/en-us/arcgis/products/arcgis-desktop). The study area boundary was derived from the China administrative boundary dataset (Source: iGISMap, https://www.igismap.com/download-china-administrative-boundary-gis-data-for-national-province-and-more/). The topographic factors were obtained from (https://lpdaac.usgs.gov/products/srtmgl1v003/).”

Data source

The primary dataset used to derive FVC was the MODIS normalized difference vegetation index (NDVI) product, specifically the MOD13Q1 version 061 (ee.ImageCollection(“MODIS/061/MOD13Q1”)), obtained from the Google Earth Engine (GEE) platform. In addition, auxiliary datasets—including terrain, climatic variables, and socio-economic dataset—were incorporated to support the analysis. The sources of each dataset are listed in Table 1.

Data preprocessing

FVC was estimated using the dimidiate pixel model applied to the MOD13Q1 NDVI time series. To ensure data quality, cloud-contaminated pixels were removed by applying masks based on the SummaryQA quality control flags provided in the MODIS product. Next, the Maximum Value Composite (MVC) method was employed to generate monthly NDVI time series, effectively minimizing the influence of cloud cover, atmospheric scattering, and solar zenith angle13. Subsequently, annual and seasonal NDVI datasets were derived by calculating mean values based on the monthly maximums.The resulting NDVI composites were then used to calculate seasonal and annual FVC for the study area. In this study, we defined the four seasons based on climatic characteristics as follows: spring (March-May), summer (June-August), autumn (September-November), and winter (December-February, including December of the current year and January-February of the following year.

Auxiliary data, including terrain, climate, and socio-economic factors, were incorporated. All datasets were uniformly resampled to 1 km resolution in R to ensure consistency in spatial analysis and modeling. When resampling all data to a 1 km resolution using R software, different interpolation methods are employed based on data characteristics. For land cover type (CLCD) categorical data, nearest neighbor interpolation is selected as it preserves the original unique values, prevents the creation of non-existent intermediate categories, and maintains the discrete nature of categorical data. Although this approach may slightly deform spatial structures or lose small features, it ensures the integrity and clear boundaries of land cover categories. For continuous variables such as DEM and temperature, bilinear interpolation is applied, which calculates weighted averages of surrounding pixels to produce smoother transitions that better represent the continuous variation inherent in natural variables. While this method may attenuate extreme values or modify local variability, it generally preserves spatial trends and gradient patterns more effectively17.

Methods

Dimidiate pixel model

The calculation formula is as follows:

In the formula: NDVIveg represents the NDVI value when vegetation is present, and NDVIsoil represents the NDVI value of bare soil when there is no vegetation cover.This study selects the NDVI pixel cumulative percentage interval of 5–95% as the confidence interval. Specifically, NDVIveg corresponds to the NDVI value when the cumulative percentage of pixels reaches 95%; NDVIsoil corresponds to the NDVI value when the cumulative percentage of pixels reaches 5%. The FVC is then calculated using the dimidiate pixel model The extreme NDVI values (maximum and minimum) in remote sensing imagery are often affected by outliers caused by clouds, snow, water bodies, and other noise, which may not represent the typical conditions of vegetation or bare soil. Using the absolute maximum and minimum values can introduce significant errors due to these anomalies. By selecting the 5% and 95% as NDVIsoil and NDVIveg, the influence of outliers is effectively reduced, and the chosen NDVI extremes become more representative and robust. This approach improves the accuracy and reliability of FVC estimation and has been widely adopted in remote sensing studies for determining NDVI extremes18.

Trend analysis

Sen’s slope estimator is recognized as a robust method for trend analysis and is widely used in the study of long-term time series data19. The calculation formula is presented as follows:

The formula for the Mann–Kendall test is as follows13:

In the formula, 1 < i < j < n, where var represents the computed variance function; sign is a sign function; i and j denote points in the time series; n is the length of the time series.The interannual and seasonal trends of FVC changes in this study are categorized according to Table 2.

The Hurst Index is a statistical method used to quantitatively assess the persistence or anti-persistence of a time series20,21. The Hurst exponent, derived from rescaled range (R/S) analysis, quantifies the long-term memory and self-similarity of a time series, as expressed by:

where C is a constant and H is the Hurst exponent obtained through linear regression. The value of H ranges between 0 and 1: H = 0.5 indicates a purely random process with no temporal correlation; 0.5 < H < 1 suggests persistence, meaning future trends are likely to continue in the same direction; 0 < H < 0.5 implies anti-persistence, indicating a tendency for trend reversal.By integrating the direction and magnitude of Sen’s slope with the persistence level indicated by the Hurst exponent, a deeper understanding of future vegetation dynamics can be achieved. The detailed overlay analysis methodology is presented in Table 3.

Coefficient of variation

The coefficient of variation (CV) is commonly used to assess the fluctuation status of long-term series data, reflecting the stability and relative dispersion of the natural environment in the study area22. This study uses CV to examine the stability of the FVC in Heilongjiang Province, and the formula is as follows:

In the formula, n represents the duration of the study. avg(FVC) denotes the average of FVC. i represents the year.The stability of interannual and seasonal FVC in this article is categorized according to Table 4.

Centroid shift model

The Centroid Shift Model is employed to analyze the spatial migration characteristics of the FVC23,24. This model quantifies the movement of the ecosystem quality’s spatial distribution over time by calculating the centroid coordinates of FVC values within each grid cell and assessing the distance of centroid shifts across different time periods. The calculation method is detailed below:

Where (xk, yk) are the spatial coordinates of the k-th FVC observation within the grid cell. \(\:{\mathbf{F}\mathbf{V}\mathbf{C}}_{\mathbf{k}}\) is the FVC value at the k-th observation point.n is the total number of FVC observations within the grid cell.

\(\:{\mathbf{C}}_{\mathbf{x},{\mathbf{t}}_{1}}\) and \(\:{\mathbf{C}}_{\mathbf{y},{\mathbf{t}}_{1}}\)are the centroid coordinates at time \(\:{\mathbf{t}}_{1}\). \(\:{\mathbf{D}}_{\mathbf{i},\mathbf{j}}\) is the centroid shift distance for grid cell (\(\mathbf{i},\mathbf{j}\)).

Moran’s index

In this study, Moran’s I was used to assess the spatial autocorrelation of FVC in Heilongjiang Province. Spatial autocorrelation is a statistical method for quantifying the clustering or dispersion of geographic variables. Among the most widely used indicators is Moran’s I, which includes two forms: global and local25,26. The global Moran’s I detects overall clustering patterns across the region, while the local Moran’s I identifies specific locations with significant spatial association or spatial outliers.

Random forest shap analysis

In this study, we conducted a comprehensive analysis of multiple driving factors influencing changes in FVC. We first compared the performance of several decision tree-based ensemble learning models, including Random Forest, Gradient Boosting and CatBoost. Each model was configured with 500 decision trees (n_estimators = 500) and applied to explore the relationships between FVC and twelve potential driving factors, including climatic variables, topographic features, and socioeconomic indicators.

To ensure robust model performance evaluation, the dataset was randomly divided into 70% training and 30% validation samples. This process was repeated ten times to account for randomness in data sampling and increase statistical reliability. The final model performance was obtained by averaging the results across the 10 validation runs. Performance metrics included the coefficient of determination (R²), root mean square error (RMSE), and mean absolute error (MAE). As presented in Table 5, the Random Forest model consistently outperformed the other models across all seasons.Due to its superior and stable performance, Random Forest was selected as the primary model for further analyzing the driving mechanisms of FVC variation. Ability to reduce overfitting, handle high-dimensional and heterogeneous data, and capture complex nonlinear interactions makes it particularly suitable for modeling vegetation dynamics in diverse environmental settings.

To accurately quantify the contribution of each factor, we applied the SHAP (Shapley Additive exPlanations) method to analyze the marginal contribution of each driving factor in the Random Forest model. The SHAP method achieves this by calculating the contribution value (Shapley value) of each feature to the prediction results. Specifically, the SHAP method determines the contribution of each driving factor by analyzing the model’s predicted values based on feature subsets and the changes in predictions after adding target features. By accumulating and averaging the marginal contributions of all possible feature combinations, we ultimately determined the overall contribution of each factor to FVC changes. This method effectively quantifies the Importance of various driving factors, providing reliable scientific evidence for understanding the driving mechanisms of FVC changes27.

Geographical detector

Geodetector identifies spatial heterogeneity and its driving factors through discretization of data, extraction of attributes, analytical detection, and interpretation of results28. To explore how climatic and anthropogenic factors jointly influence FVC patterns in Heilongjiang Province, this study employs geodetector methods implemented via the GD package in R.

Results

Temporal dynamics of vegetation FVC

Based on existing research, Fractional Vegetation Cover (FVC) was categorized into five levels: Low FVC [0, 0.1] (Level I), Low-Medium FVC (0.1, 0.3) (Level II), Medium FVC (0.3, 0.5) (Level III), Medium-High FVC (0.5, 0.7) (Level IV), and High FVC (0.7, 1.00) (Level V)29.

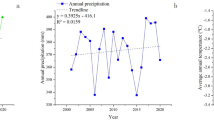

The interannual variation in FVC across Heilongjiang Province from 2000 to 2021 demonstrated a fluctuating downward trend, ranging between 0.43 and 0.49. The multi-year average FVC was 0.461, with an annual decrease rate of 0.008 (10⁻¹/year)(P > 0.05). Notably, the interannual rate of change in vegetation FVC varied significantly across different seasons. Spring and winter exhibited higher rates of change, measured at 0.013 (10⁻¹/year) (P > 0.05) and 0.016 (10⁻¹/year) (P > 0.05) respectively, with corresponding average FVC values of 0.45 and 0.291. In contrast, summer and autumn showed slower rates of change, at 0.009 (10⁻¹/year) (P < 0.05) and 0.004 (10⁻¹/year) (P > 0.05), with average FVC values of 0.665 and 0.441, respectively (Fig. 2). The interannual variation in FVC exhibited no significant downward trend in spring, autumn, and winter, while summer showed a significant upward trend.

Analysis of area transfer between different FVC levels in 2000 and 2021 revealed the following net area changes in FVC levels across Heilongjiang Province (Tables 6, 7):

Annual Low FVC increased by 8,961.33 km² (+ 138.2%), Low-Medium FVC increased by 57,044.93 km² (+ 117.7%), Medium FVC decreased by 52,203.00 km² (− 26.3%), Medium-High FVC decreased by 9,407.30 km² (− 8.1%), and High FVC decreased by 4,395.83 km² (− 5.9%).

In spring, Low FVC area expanded by 6,338.47 km² (+ 106.8%), and Low-Medium FVC area increased by 61,090.56 km² (+ 90.2%). Conversely, Medium FVC area contracted by 82,683.30 km² (− 39.4%), and Medium-High FVC area also decreased by 19,350.02 km² (− 19.4%). High FVC area showed an increase of 34,604.37 km² (+ 57.6%).

During summer, Low FVC area decreased by 395.21 km² (-2.1%). Low-Medium FVC area decreased by 10,225.34 km² (− 40.3%), and Medium FVC area also decreased by 38,312.08 km² (− 49.4%). Conversely, both Medium-High FVC and High FVC areas expanded, increasing by 43,503.10 km² (+ 42.6%) and 4,805.10 km² (+ 2.2%), respectively.

In autumn, Low FVC area expanded considerably by 17,268.59 km² (+ 228.2%), and Low-Medium FVC area increased by 43,777.79 km² (+ 46.6%). Medium FVC area decreased by 47,834.60 km² (− 30.2%). Medium-High FVC area increased by 991.31 km² (+ 1.0%), while High FVC area decreased by 14,692.50 km² (− 16.9%).

Winter exhibited an increase in Low FVC area, expanding by 25,324.90 km² (+ 14.0%). Low-Medium FVC area decreased by 41,044.90 km² (− 28.0%), and Medium FVC area decreased, albeit by 1,113.83 km² (− 2.4%). Medium-High FVC area increased by 15,795.79 km² (+ 55.5%), while High FVC area increased by 1,038.08 km² (+ 2.5%).

Seasonal characteristics of FVC changes

To explore the characteristics of inter-seasonal variations in FVC, Sankey diagrams were created to illustrate the area transfer of FVC across different seasons (Fig. 3). From spring to summer, Low FVC area increased by 8653.07 km² (+ 139.2%), Medium-High FVC area increased by 45495.12 km² (+ 32.5%), and High FVC area increased by 176627.65 km² (+ 227.7%). Concurrently, Low-Medium FVC area decreased by 155229.24 km² (-86.2%), and Medium FVC area decreased by 75546.60 km² (− 57.3%). Subsequently, from summer to autumn, Low-Medium FVC area increased by 140546.18 km² (+ 566.8%), and Medium FVC area increased by 108202.68 km² (+ 192.1%). In contrast, Low FVC area decreased by 5597.03 km² (− 37.9%), Medium-High FVC area decreased by 62577.60 km² (− 33.8%), and High FVC area decreased by 180574.23 km² (− 71.0%). Moving into winter, Low FVC area increased by 109221.82 km² (+ 1146.3%), and Low-Medium FVC area increased by 64364.85 km² (+ 38.9%), while Medium FVC area decreased by 79116.99 km² (− 48.1%), Medium-High FVC area decreased by 68407.19 km² (− 55.7%), and High FVC area decreased by 26062.49 km² (− 35.4%). Overall, from spring to winter, Low FVC and Low-Medium FVC areas exhibited net increases of 112294.95 km² (+ 1477.1%) and 49664.68 km² (+ 27.6%), respectively, while Medium FVC, Medium-High FVC, and High FVC areas showed net decreases of 46460.91 km² (− 35.2%), 85489.66 km² (− 61.1%), and 30009.07 km² (− 38.7%), respectively.

Spatial distribution pattern of vegetation FVC

Based on Fig. 4, the spatial distribution of annual FVC in Heilongjiang Province exhibits a distinct pattern, decreasing from the central region towards the southwest and northeast, indicating significant spatial heterogeneity. Higher vegetation cover is concentrated in the central and northwestern areas, while lower cover is observed in the southwest and northeast. The annual FVC level proportions are as follows: Low FVC accounts for 1.7%, Low-Medium FVC for 22.4%, Medium FVC for 35.2%, Medium-High FVC for 26.7%, and High FVC for 14%. The spatial distribution also demonstrates pronounced seasonal variations. Except for summer and winter, the spatial distribution characteristics of vegetation FVC in other seasons are similar to the annual average FVC distribution. In spring, high FVC areas are primarily concentrated in the central, northwestern, and southeastern parts of the province, whereas low FVC areas are mainly located in the southwest and northeast. The proportions of FVC categories in spring are: Low FVC at 1.5%, Low-Medium FVC at 33.6%, Medium FVC at 24.5%, Medium-High FVC at 26%, and High FVC at 14.4%.

Interannual and seasonal mean FVC distribution maps for Heilongjiang Province. Map generated using ArcGIS version10.8 (https://www.esri.com/en-us/arcgis/products/arcgis-desktop). The study area boundary was derived from the China administrative boundary dataset. (Source: iGISMap, https://www.igismap.com/download-china-administrative-boundary-gis-data-for-national-province-and-more/). The mean FVC was calculated using the MODIS/Terra Vegetation Indices 16-Day L3 Global 250 m (MOD13Q1 Version 6.1) dataset from NASA LPDAAC (https://lpdaac.usgs.gov/products/mod13q1v061/) in R 4.4.0 (https://cran.r-project.org/src/base/R-4/).

In summer, the spatial extent of high FVC areas significantly expands compared to spring, with notable improvements in vegetation FVC in the southwest and northeast. Low FVC areas in summer are primarily distributed in the southwestern region. Summer FVC category proportions are: Low FVC at 2.9%, Low-Medium FVC at 4.6%, Medium FVC at 10.5%, Medium-High FVC at 34.6%, and High FVC at 47.4%.

During autumn, high FVC areas are mainly distributed in the central, northwestern, and southeastern parts of the study area, while low FVC areas are predominantly situated in the southwest and northeast, mirroring the spring distribution pattern. Autumn FVC category distributions are as follows: Low FVC at 1.8%, Low-Medium FVC at 30.9%, Medium FVC at 30.7%, Medium-High FVC at 22.9%, and High FVC at 13.7%.

In winter, high FVC areas remain concentrated in the central, northwestern, and southeastern regions of the study area, consistent with the autumn distribution. Low FVC areas in winter are primarily located in the southwest and northeast. Winter FVC category proportions are: Low FVC at 22.4%, Low-Medium FVC at 42.7%, Medium FVC at 15.9%, Medium-High FVC at 10.1%, and High FVC at 8.9%.

The Moran’s I index values of FVC in Heilongjiang Province for the annual, spring, summer, autumn, and winter periods are 0.903, 0.898, 0.856, 0.901, and 0.906, respectively (Fig. 5). Statistical tests confirmed the significance of this clustering, with z-values > 1.96 and p-values < 0.05, demonstrating a strong positive spatial autocorrelation in the study area.

According to the LISA cluster maps (Fig. 6), the spatial correlation of FVC in Heilongjiang shows seasonal variation. For the annual, spring, autumn, and winter periods, low–low (LL) clustering dominates, accounting for 47.1%, 45.8%, 44.7%, and 51.9% of the total area, respectively, mainly distributed in the southwestern and northeastern regions. In contrast, during summer, the dominant pattern is high–high (HH) clustering, covering 44.9% of the area, primarily located in the northwestern, central, and southeastern regions.

LISA Cluster Map. Map generated using ArcGIS version10.8 (https://www.esri.com/en-us/arcgis/products/arcgis-desktop). The LISA Cluster was calculated using the MODIS/Terra Vegetation Indices 16-Day L3 Global 250 m (MOD13Q1 Version 6.1) dataset from NASA LPDAAC (https://lpdaac.usgs.gov/products/mod13q1v061/) in R 4.4.0 (https://cran.r-project.org/src/base/R-4/).

FVC under different land cover types

FVC varies across different land cover types (Fig. 7). The average annual FVC for each land cover type is as follows: bare land (0.133), cropland (0.320), forest (0.621), grassland (0.285), impervious surface (0.241), water body (0.121), and wetland (0.378). In spring, the FVC values for each land cover type are: bare land (0.172), cropland (0.296), forest (0.615), grassland (0.323), impervious surface (0.250), water body (0.157), and wetland (0.355). Summer FVC values for each land cover type are: bare land (0.126), cropland (0.545), forest (0.812), grassland (0.375), impervious surface (0.347), water body (0.252), and wetland (0.605). Average autumn FVC values for different land cover types are: bare land (0.120), cropland (0.296), forest (0.599), grassland (0.269), impervious surface (0.228), water body (0.162), and wetland (0.408). Winter FVC values for each land cover type are: bare land (0.164), cropland (0.134), forest (0.451), grassland (0.173), impervious surface (0.157), water body (0.0914), and wetland (0.146).

Spatial distribution of FVC under different topographic conditions

To investigate the FVC distribution under different topographic conditions, we categorized slope and elevation into the following levels. Slope was classified into five levels: Level 1 (0–5°), Level 2 (5°-10°), Level 3 (10°-15°), Level 4 (15–20°) and Level 5 (> 25°). Elevation was also classified into five levels: Level 1 (29–200 m), Level 2 (200–400 m), Level 3 (400–600 m), Level 4 (600–800 m), and Level 5 (> 800 m) (Fig. 8). Although FVC reached its maximum value at Level 3 (15°–25°), with annual and seasonal (spring, summer, autumn, winter) values of 0.705, 0.709, 0.847, 0.714, and 0.548, respectively, trend analysis indicated an overall increasing pattern of FVC with increasing slope, with annual (p > 0.05), spring (p > 0.05), summer (p > 0.05), autumn (p < 0.05), winter (p < 0.05), and annual average (p > 0.05).Similarly, while FVC peaked at elevation Level 4 (600–800 m), with average annual and seasonal (spring, summer, autumn, winter) values of 0.688, 0.669, 0.825, 0.668, and 0.586, respectively, the overall trend showed that FVC increased with elevation, with spring (p > 0.05), summer (p > 0.05), autumn (p > 0.05), winter (p > 0.05), and annual average (p > 0.05).

Stability of vegetation FVC

The interannual fluctuation of FVC in Heilongjiang Province is relatively low. Highly stable areas account for 36.6%, medium-high stability areas for 33.7%, medium stability areas for 16.5%, low stability areas for 9%, and extremely low stability areas for 4.2%. Highly stable regions are primarily distributed in the northwest, central, and southeast, while unstable areas are concentrated in the southwest and northeast. Overall, the interannual variation of vegetation in Heilongjiang Province is relatively stable (CV value of 0.133).

In spring, highly stable areas constitute 10%, medium-high stability areas 16%, medium stability areas 15.8%, low stability areas 26.2%, and extremely low stability areas 32%. Regions with higher stability are mainly distributed in the central and northwestern parts of the study area, whereas areas with lower stability are predominantly located in the southwest and northeast. Overall, spring exhibits higher fluctuation (CV value of 0.254).

Summer FVC demonstrates a marked increase in stability, being the most stable season, with highly stable areas accounting for 69.3%. Among these, highly stable regions constitute 47%, primarily concentrated in the central, northwestern, and southeastern areas. Compared to spring, low stability areas in summer are significantly reduced, covering approximately 8.6% of the study area, mainly in the southwest. Overall, summer FVC fluctuation is relatively low (CV value of 0.183).

Autumn FVC exhibits greater fluctuation (CV value of 0.278), with low and extremely low stability areas accounting for 23.5% and 42.5% respectively, predominantly concentrated in the southwest, northwest, and northeast regions. Areas with higher FVC stability account for 22%, mainly concentrated in the central region.

Winter FVC shows the highest fluctuation (CV value of 0.671). Areas with higher FVC stability only account for 7.8%, primarily concentrated in the central region. The remaining areas with lower stability constitute 88.1% (Fig. 9).

Spatial map of interannual and seasonal FVC stability. Map generated using ArcGIS version10.8 (https://www.esri.com/en-us/arcgis/products/arcgis-desktop). The FVC coefficient of variation (CV) was calculated using the MODIS/Terra Vegetation Indices 16-Day L3 Global 250 m (MOD13Q1 Version 6.1) dataset from NASA LPDAAC (https://lpdaac.usgs.gov/products/mod13q1v061/) in R 4.4.0 (https://cran.r-project.org/src/base/R-4/).

Spatial trends of vegetation FVC

According to the results of the Sen’s slope and Mann-Kendall (Sen-MK) test, interannual vegetation change predominantly exhibited a decreasing trend, covering 61.8% of the total area and primarily concentrated in the southwestern and northeastern regions of the province. Similarly, spring, autumn, and winter were also dominated by decreasing trends, affecting 58.5%, 54.1%, and 71.1% of the area, respectively. Among these, the decline in autumn was mainly distributed in the western and eastern regions, while the spatial patterns in spring and winter were generally consistent with the interannual trend. In contrast, summer was characterized by a predominant increasing trend, mainly concentrated in the southwestern and northeastern regions (Fig. 10).

Spatial Variation Trend Map of FVC. Map generated using ArcGIS version10.8 (https://www.esri.com/en-us/arcgis/products/arcgis-desktop). The spatial variation trend of FVC was calculated using the MODIS/Terra Vegetation Indices 16-Day L3 Global 250 m (MOD13Q1 Version 6.1) dataset from NASA LPDAAC (https://lpdaac.usgs.gov/products/mod13q1v061/) in R 4.4.0 (https://cran.r-project.org/src/base/R-4/).

By calculating the centroid shift of annual and seasonal FVC, we observed an overall westward shift in the annual centroid. The largest annual centroid shift occurred between 2005 and 2006, with a southeastern movement of 22.3 km. The spring centroid generally shifted eastward, with the most significant shift between 2003 and 2004, moving 88.8 km southeastward. In summer, the centroid generally shifted westward, with the largest shift between 2003 and 2004, moving 21 km northwestward. The autumn centroid also generally shifted westward, with the greatest shift between 2002 and 2003, moving 98.9 km southwestward. The winter centroid similarly showed an overall westward shift, with the largest shift between 2012 and 2013, moving 68 km northwestward (Fig. 11).

Based on the analysis of Sen’s slope and the Hurst exponent, the future vegetation change in Heilongjiang Province is projected to exhibit a predominantly persistent decreasing trend. Areas showing a persistently decreasing trend on an interannual scale account for 54.7% of the total area, mainly concentrated in the southwestern and northeastern regions. Similarly, future vegetation changes in spring, autumn, and winter are also expected to be dominated by decreasing trends, covering 49.1%, 34.6%, and 47% of the area, respectively. Among these, the spatial distribution of persistently decreasing trends in spring is generally consistent with the interannual pattern, while in autumn, such areas are mainly located in the western and eastern regions. In winter, they are primarily concentrated in the northern and southern parts of the province. In contrast, summer is projected to be dominated by a persistently increasing trend, covering 40.1% of the area, with the majority of these regions located in the southwest and northeast (Fig. 12).

Future Spatial Variation Map of FVC Map generated using ArcGIS version10.8 (https://www.esri.com/en-us/arcgis/products/arcgis-desktop). The future spatial variation map was generated using the MODIS/Terra Vegetation Indices 16-Day L3 Global 250 m (MOD13Q1 Version 6.1) dataset from NASA LPDAAC (https://lpdaac.usgs.gov/products/mod13q1v061/) in R 4.4.0 (https://cran.r-project.org/src/base/R-4/).

Driving factors of FVC

Temporal trends of climatic factors

We analyzed the temporal trends of driving factors for both interannual and seasonal scales from 2000 to 2021(Fig. 13). Interannually, temperature increased at a rate of 0.0243 ℃/year (p > 0.05), with an average of 1.98 ℃. In spring, temperature increased annually by 0.0381 ℃ (p > 0.05,), averaging 3.75 ℃. Summer annual temperature showed a decreasing trend of 0.0149 ℃/year (p > 0.05), with an average of 19.69℃. Autumn annual temperature increased by 0.0253 ℃/year (p > 0.05), averaging 2.70 ℃. Winter annual temperature increased by 0.0501 ℃/year (p > 0.05), averaging − 18.28 ℃.

Interannual precipitation increased at a rate of 6.0939 mm/year (p < 0.05), with an average of 556.06 mm. Spring annual precipitation increased by 0.2465 mm/year (p > 0.05), averaging 95.25 mm. Summer annual precipitation increased by 3.9214 mm/year (p > 0.05), averaging 346.83 mm. Autumn annual precipitation increased by 2.0695 mm/year (p < 0.05), averaging 95.23 mm. Winter annual precipitation decreased by 1.1255 mm/year (p > 0.05), averaging 22.71 mm.

Interannual soil moisture increased at a rate of 0.4608 mm/year (p > 0.05), with an average of 30.55 mm. Spring soil moisture increased at a rate of 0.0469 mm/year (p > 0.05), averaging 28.54 mm. Summer soil moisture increased at a rate of 0.5090 mm/year (p > 0.05), averaging 33.20 mm. Autumn soil moisture increased at a rate of 0.7937 mm/year (p > 0.05), averaging 31.16 mm. Winter soil moisture increased at a rate of 0.5589 mm/year (p > 0.05), averaging 29.48 mm.

Interannual evapotranspiration (ET) increased at a rate of 3.0737 mm/year (p < 0.05), with an average of 497.91 mm. Spring ET increased at a rate of 0.8767 mm/year (p < 0.05). Summer ET increased at a rate of 1.8903 mm/year (p < 0.05), averaging 307.82 mm. Autumn ET increased at a rate of 0.3725 mm/year (p < 0.05), averaging 70.01 mm. Winter ET decreased at a rate of 0.1073 mm/year (p > 0.05, not significant), averaging 29.24 mm.

Interannual shortwave radiation decreased at a rate of 0.5304 W m− 2/year (p < 0.05), with an average of 151.95 W m− 2. Spring shortwave radiation decreased at a rate of 0.6833 W m− 2/year (p < 0.05), averaging 193.62 W m− 2. Summer shortwave radiation increased at a rate of 0.1751 W m− 2 /year (p > 0.05), averaging 218.79 W m− 2. Autumn shortwave radiation decreased at a rate of 0.9350 W m− 2/year (p < 0.05), averaging 114.30 W m− 2. Winter shortwave radiation decreased at a rate of 0.5762 W m−2/year (p < 0.05), averaging 77.79 W m−2.

Interannual SPEI increased at a rate of 0.0163/year (p > 0.05), with an average of 0.22. Spring SPEI decreased at a rate of 0.0091/year (p > 0.05), averaging 0.28. Summer SPEI increased at a rate of 0.0447/year (p < 0.05), averaging 0.07. Autumn SPEI increased at a rate of 0.0441/year (p < 0.05), averaging 0.16. Winter SPEI decreased at a rate of 0.0179/year (p > 0.05), averaging 0.37.

Random forest SHAP analysis

Based on the Random Forest SHAP values, CLCD was identified as themost impactful factor for interannual (0.087) and winter FVC (0.091), and the second most impactful factor for summer (0.058) and autumn (0.045) (Fig. 14). ET had the greatest impact on FVC during spring (0.14) and summer (0.089). For autumn, slope (0.083) was the most impactful factor. Elevation was the second most impactful factor during spring (0.038) and winter (0.061). Precipitation emerged as the second most influential factor affecting interannual FVC variations (0.043).

According to the single-factor dependency plots of the main influencing factors (Fig. 15), regarding land cover types, forests were the only type that positively contributed to FVC (0.12) on an annual basis, while all other land cover types showed negative contributions. Similarly in summer, forests showed positive contributions to FVC (0.068), with other land cover types showing negative contributions. In autumn, forests showed positive contributions to FVC (0.027), while other land cover types showed negative contributions. In winter, croplands were the only land cover type with negative contributions (0.08), while all others showed positive contributions. Regarding climatic and topographic factors, annual precipitation showed negative contributions to FVC when below 580 mm but positive contributions when above 580 mm. In spring, ET showed negative contributions to FVC when below 97.6 mm but positive contributions when above 97.6 mm; elevation showed negative contributions when below 260 m but positive contributions when above 260 m. During summer, ET showed negative contributions to FVC when below 180 mm but positive contributions when above 180 mm. In autumn, slope gradient within 0–5° showed negative contributions to FVC, while slopes above 5° showed positive contributions. Winter elevation showed negative contributions below 273 m but positive contributions above 273 m.

Geographical detector analysis

Geographical Detector was employed to assess whether the explanatory power for FVC change is enhanced when two factors are combined, as individual variables are insufficient to fully account for the variation in FVC (Fig. 16). It is necessary to consider the interactive effects of environmental factors on vegetation change. The results indicate that the combination of any two factors enhanced the explanatory power of individual factors on regional vegetation FVC. This finding suggests that FVC change is a result of the combined influence of multiple factors. Interannually, the interaction between CLCD and precipitation had the greatest impact on annual FVC, with a value of 0.714. In spring, the interaction between Elevation and ET had the largest influence on FVC, with a value of 0.780. During summer, the interaction between ET and CLCD exerted the greatest impact on FVC, with a value of 0.800. In autumn, the interaction between CLCD and Precipitation had the largest influence on FVC, with a value of 0.643. In winter, the Interaction between Temperature and Elevation had the greatest Impact on FVC, with a value of 0.585.

Discussion

Spatial distribution and variation of FVC

Based on MODIS data from 2000 to 2021, this study systematically analyzed the spatiotemporal variations of interannual and seasonal FVC in Heilongjiang Province and projected its future trends. The results show that the annual mean FVC was 0.461, exhibiting a generally insignificant declining trend. Xi and Zhang et al. reported increasing NPP and NEP trends7,8. This apparent contradiction stems from fundamental differences between these indicators: NPP and NEP are cumulative measures of carbon fixation, where high summer productivity significantly influences annual values. In contrast, FVC represents average vegetation cover over time and is more sensitive to seasonal variations, where low coverage in non-growing seasons can offset summer increases, resulting in overall declining trends.

Seasonally, FVC peaked in summer with a significant upward trend, consistent with Hu et al.6, while the lowest values occurred in winter, showing an insignificant decline. The improvement in FVC from spring to summer was mainly attributed to favorable climatic conditions—moderate temperatures, sufficient sunlight, and adequate precipitation—which promoted plant germination and growth. During the summer-autumn transition, FVC declined as vegetation matured and senesced. In winter, FVC further decreased due to low temperatures and snow cover, as most plants entered dormancy30. In contrast, Yang et al. found that FVC in Ethiopia reaches its maximum in autumn31. This difference is mainly attributed to the distinct climate zones.

The spatial distribution and stability of FVC in Heilongjiang Province exhibit a distinct pattern of being relatively high in the northwest, central, and southeastern regions, and relatively low in the southwest and northeast. This distribution pattern is highly consistent with the spatial autocorrelation analysis results.This pattern aligns closely with the spatial distribution of net ecosystem productivity (NEP) reported by Zhang et al.7. The distribution of FVC is closely associated with topographic conditions, generally increasing with rising elevation and slope, and showing a slight decline at the highest levels. Specifically, low-elevation and gentle-slope areas often experience intensive human activities such as agriculture and urban development, leading to lower vegetation cover32,33. In contrast, mid-elevation and moderate-slope regions typically face less disturbance and have more favorable growing conditions, resulting in higher FVC. At very high elevations or steep slopes, harsh environmental conditions and intensified soil erosion may limit vegetation growth, causing FVC to slightly decrease34. The distribution of FVC also varies significantly across different land use types. Forested areas show markedly higher FVC compared to other land types, owing to the presence of tall tree canopies and rich understory vegetation. The complex vertical structure and well-defined stratification of forest ecosystems enable more efficient utilization of space and sunlight, thereby resulting in higher vegetation cover35.

Based on the results of the Sen-MK test, FVC in Heilongjiang Province has exhibited an overall non-significant decreasing trend over the past 22 years, suggesting a slight degradation in vegetation coverage. While areas experiencing a decline in FVC surpass those with an increase in most seasons (with the exception of summer), regions characterized by non-significant changes predominate across all seasons. This spatial distribution pattern suggests that vegetation cover has remained relatively stable overall, without widespread significant degradation—a phenomenon largely attributable to government-led ecological conservation initiatives. Such as the In northeastern Heilongjiang’s agricultural regions, authorities have implemented strict controls on cropland expansion, promoted sustainable farming practices that enhance soil organic matter, and incentivized agroforestry systems along field margins. For the southwestern industrial regions, which showed greater vulnerability to pollution-related FVC decline, targeted policies have included stricter industrial emission standards, establishment of green buffer zones around industrial facilities, and brownfield restoration using pollution-tolerant native vegetation36,37.

During the summer season, FVC primarily exhibits improvement trends; however, these improvements are predominantly non-significant. Future projections indicate continued growth, reflecting the relatively stable and vigorous growth characteristic of vegetation during this season. In contrast, winter FVC demonstrates the lowest level of stability, mainly showing non-significant declining trends, with continued deterioration expected in the future. Notably, the spatial shift of the vegetation cover centroid during winter is the most pronounced among all seasons, displaying a distinct westward trajectory. This significant movement highlights the heightened vulnerability of winter vegetation to environmental stressors.

Driving factor analysis

To comprehensively verify the roles of key environmental drivers of FVC, this study integrates SHAP value analysis based on a random forest model with the interaction detection module of Geodetector. SHAP analysis quantifies the contribution of each environmental factor to the model output, capturing nonlinear responses and the direction of influence, which helps identify major environmental driving forces and clarify their functional pathways. By contrast, Geodetector is applied to examine the interaction effects among environmental variables, thereby quantifying the extent to which these factors interact with each other. While SHAP emphasizes the direct effect of individual environmental factors on prediction outcomes, Geodetector highlights the synergistic interactions among multiple variables. These two approaches offer complementary perspectives: the SHAP method reveals nonlinear single-factor responses, whereas Geodetector uncovers multi-factor coupling mechanisms. The integration of both methods enables a more comprehensive understanding of the environmental processes driving the spatial patterns of FVC.

Based on the SHAP importance ranking, CLCD emerges as the dominant factor influencing FVC in Heilongjiang Province. In contrast, Jia et al. found that precipitation was the primary driving factor for vegetation coverage in the Yellow River Basin. This difference can be attributed to the relatively arid conditions in the Yellow River Basin, where precipitation becomes the main limiting factor for vegetation growth38. The strong explanatory power of CLCD for FVC variation is primarily attributed to the land use composition of Heilongjiang Province, which is dominated by cropland and forest. These land cover types exhibit significant differences in water retention, photosynthesis, and growth patterns39.

From 2000 to 2021, land use in Heilongjiang Province underwent substantial changes [Fig. 17]: impervious surfaces increased by 5,092 km² (+ 53.68%), reflecting accelerated urbanization and infrastructure development; forest areas decreased by 2,805 km² (− 1.25%), grasslands by 1,953 km² (− 23.79%), wetlands by 800 km² (− 66.01%), croplands by 438 km² (− 0.22%), and bare land by 424 km² (− 55.64%), while water bodies expanded by 1,328 km² (+ 23.23%), consistent with the findings of Xi et al.8.

During this same period, Heilongjiang Province experienced GDP growth, alongside increasing population density40. The SHAP analysis revealed that while population density and GDP showed limited direct influence on FVC, as GDP and population density increased, FVC decreased. This negative relationship suggests that human economic activities such as logging and grazing have adversely affected vegetation41. Further analysis of GDP and population density distribution across different land cover types showed that impervious surfaces had the highest values for both of these metrics (Fig. 18).

The Geographical Detector results provided crucial insights, demonstrating that the interaction between land cover changes (CLCD) and socioeconomic factors (population density and GDP) explained FVC variation more effectively than any single factor in isolation. Economic development and population growth drive urbanization processes, leading to impervious surface expansion at the expense of vegetation-rich land cover types, ultimately resulting in FVC decline42.

Analysis of climate factor trends in Heilongjiang Province indicates a lagged response of FVC to climatic variables. Climate change exerts a cumulative impact on vegetation growth, whereby not only current climatic conditions but also antecedent climate conditions measurably influence vegetation health. Vegetation growth requires time to respond to various natural factors, resulting in periodic interactions between vegetation growth and climatic variables that manifest as delayed effects across different temporal scales43.

In spring and summer, ET ranked as the most important factor affecting FVC, with SHAP analysis showing that higher ET values led to consistently increased FVC in both seasons. This is primarily because higher temperatures promote plant growth and transpiration44. Higher ET also consistently promotes FVC in autumn periods, but shows weaker and dual effects in winter due to reduced soil moisture. Cold-resistant plants maintain metabolic activities under limited water conditions through physiological adaptations, while other vegetation may experience exacerbated water stress45.

Slope emerges as the dominant factor in autumn, as steeper areas retain more natural vegetation while low-slope agricultural areas experience substantial FVC decline after the growing season. In contrast, Shen et al. found that soil moisture plays a key role in autumn phenological responses of marsh wetlands on the Tibetan Plateau46. This difference is primarily attributed to the distinct ecosystem types between the two regions. The marsh wetlands on the Tibetan Plateau represent moisture-sensitive wetland ecosystems, where soil moisture directly influences the growth status and phenological changes of wetland vegetation.

Interaction detection results indicated that the interaction between CLCD and precipitation had the strongest influence on interannual and autumnal variations in FVC. Different land cover types exhibit varying capacities for water retention; for example, deep-rooted vegetation such as forests can retain soil moisture more effectively, while grasslands and barren lands have relatively poor water-retention capabilities. These differences amplify the combined effect of precipitation and CLCD on FVC dynamics47. In the Chengdu–Chongqing urban agglomeration, this finding is consistent with their results48. Despite differences in study areas, the interaction between CLCD and precipitation exhibits a high degree of consistency in its impact on FVC across regions, suggesting that this mechanism has broad applicability. However, they did not conduct seasonally stratified analyses, which may have limited their ability to fully reveal the interaction mechanisms operating during different seasons. By contrast, our study conducted seasonally stratified interaction analyses, which revealed that In spring, the interaction between elevation and ET had the greatest influence on FVC changes. As temperatures rise during spring, ET increases, and its rate varies with elevation. Therefore, the interaction between ET and elevation plays a key role in driving springtime FVC changes49. In summer, the interaction between ET and land cover types CLCD was identified as a primary driver of FVC variability. This can be attributed to the differential ET responses across land cover types under conditions of adequate soil moisture and favorable temperatures, which in turn modulate spatial patterns of vegetation cover50. During winter, the interaction between temperature and elevation had the greatest influence on FVC variations. Low temperatures affect soil freeze–thaw cycles and shorten the vegetation growing season, while elevation influences moisture distribution and snowmelt processes. As such, their combined effect plays a key role in driving winter FVC changes51.

Regional management recommendations

The spatiotemporal analysis of FVC in Heilongjiang Province has revealed distinct distribution patterns and change trends, providing significant implications for regional ecological conservation and sustainable development. The identified spatial clustering characteristics of FVC, particularly the low-low aggregation areas in the southwestern and northeastern regions, offer scientific basis for precision ecological governance. These vulnerable areas should be prioritized for ecological restoration through the establishment of eco-compensation mechanisms that engage local residents in conservation efforts. Concurrently, high-high aggregation areas require long-term protection mechanisms to prevent ecological degradation.

Under future climate change scenarios, Heilongjiang Province’s FVC may face increasingly complex variations. Rising temperatures and altered precipitation patterns could intensify seasonal differences in FVC, with summer FVC potentially increasing due to extended growing seasons, while extreme climate events may simultaneously impose stress on vegetation. Anthropogenic influences will persist, with urbanization processes increasing impervious surface area, but green infrastructure development and sustainable agricultural practices mitigate these pressures.

Uncertainties and limitations

This study analyzes the spatiotemporal variations and driving mechanisms of FVC in Heilongjiang Province. Despite valuable findings, several limitations affect the results’ accuracy and generalizability.

The primary uncertainty stems from MODIS-derived NDVI data. While MODIS provides high temporal resolution, its 250 m spatial resolution may miss fine vegetation heterogeneity in fragmented landscapes. Although this resolution is appropriate for large-scale regional analysis as conducted in this study, it presents limitations for capturing small-scale vegetation patterns and changes. Future research could build upon this MODIS-based long-term series analysis by incorporating higher resolution data (such as Sentinel-2, GF-1/2) for detailed verification and supplementary analysis of typical areas, thereby more comprehensively and accurately revealing local vegetation change mechanisms in smaller regions. Meanwhile, NDVI sensitivity to atmospheric conditions, cloud cover, and sensor noise introduces potential errors52,53. Although we applied cloud masking and maximum value compositing through Google Earth Engine, residual noise persists. Limited field validation data further constrains our ability to verify remote sensing results, particularly in areas with complex topography.

Our driver analysis using Random Forest with SHAP interpretation and geographical detectors identified key factors, but important variables were excluded due to data constraints: extreme climate events, soil properties, pest outbreaks, and fire disturbances. Additionally, we did not analyze cumulative or lagged climate effects on vegetation dynamics, which may be crucial for understanding current FVC patterns.

Conclusions

This study focused on investigating the spatiotemporal characteristics and driving factors of Fractional Vegetation Cover (FVC) in Heilongjiang Province across different temporal scales from 2000 to 2021. The principal findings are as follows:

-

(1)

FVC trends in Heilongjiang Province generally exhibit non-significant decreases in spring, autumn, and winter, with a significant increasing trend in summer. The spatial distribution shows high values in the central, northwest, and southeast regions, with substantial heterogeneity. Summer demonstrates the largest improvement area and highest stability. The center of gravity predominantly shifts westward (except in spring). Moran’s I indices indicate significant positive spatial autocorrelation, with low-low clusters dominating in most seasons and high-high clusters predominating in summer.

-

(2)

Random Forest SHAP analysis identified ET, CLCD, ELE and slope factors as key variables influencing FVC dynamics. Forests within the CLCD make positive contributions to FVC enhancement. Geographic detector analysis indicates that combinations of any two factors augment the explanatory power of individual factors regarding regional vegetation FVC, with the interaction between summer ET and CLCD exhibiting the strongest effect.

-

(3)

Limitations of this study include the spatial resolution constraints of MODIS data, insufficient soil characteristic data, and lack of field validation. Future research should focus on ecologically sensitive areas, integrate high-resolution remote sensing data (e.g., Sentinel-2, GF-1/2), incorporate field validation, longer time series data, and soil characteristics, and develop climate-vegetation response models to provide scientific basis for regional precision ecological management.

In conclusion, despite certain limitations, this research provides theoretical support and methodological references for monitoring, restoration, and sustainable management of Heilongjiang’s ecosystems. The findings offer significant guidance for precisely identifying key areas for vegetation improvement in Heilongjiang Province, optimizing land use patterns, and addressing regional ecological risks in the context of climate change.

Data availability

Remote sensing datasets generated and/or analysed during this study are available at Economic DataGDP data: https://www.resdc.cn/ Population Population data: WorldPop (https://www.worldpop.org/) Vegetation Indices NDVI (Normalized Difference Vegetation Index): MODIS/Terra Vegetation Indices 16-Day L3 Global 250 m (MOD13Q1 Version 6.1) from NASA LPDAAC (https://lpdaac.usgs.gov/products/mod13q1v061/) Topographic Data Terrain Elevation (30 m resolution): NASA Shuttle Radar Topography Mission Global 1 arc second (SRTMGL1 Version 3) from NASA LPDAAC (https://lpdaac.usgs.gov/products/srtmgl1v003/) Slope (30 m resolution): Derived from NASA SRTMGL1 Version 3 (https://lpdaac.usgs.gov/products/srtmgl1v003/) Slope Aspect (SA) (30 m resolution): Derived from NASA SRTMGL1 Version 3 (https://lpdaac.usgs.gov/products/srtmgl1v003/) Solar Radiation Sunshine Downward short-wave radiation flux (SWR) (27830 m resolution, 3-hour intervals): `1Global Land Data Assimilation System (GLDAS Noah Land Surface Model L4 3-hourly 0.25° x 0.25° Version 2.1) from NASA GES DISC (https://disc.gsfc.nasa.gov/datasets/GLDAS_NOAH025_3H_2.1/summary) Climate DataPrecipitation (Pre) (1000 m resolution, monthly): Available at (https://data.tpdc.ac.cn/zh-hans/data/faae7605-a0f2-4d18-b28f-5cee413766a2)Temperature (TEM) (1000 m resolution, monthly): China Meteorological Data Sharing Service (https://cstr.cn/18406.11.Meteoro.tpdc.270961)Standardized Precipitation Evapotranspiration Index (SPEI) (0.1° resolution, monthly): China Drought Monitoring dataset (https://figshare.com/articles/dataset/CHM_Drought/25656951/2)Evapotranspiration (ET) (500 m resolution, 8-day intervals): MODIS/Terra Net Evapotranspiration 8-Day L4 Global 500 m (MOD16A2GF Version 6.1) from NASA LPDAAC (https://lpdaac.usgs.gov/products/mod16a2gfv061/)Soil Moisture (SM) (4000 m resolution, monthly): TerraClimate dataset available through Google Earth Engine (https://developers.google.com/earth-engine/datasets/catalog/IDAHO_EPSCOR_TERRACLIMATE) Land CoverLand Cover Types (CLCD) (30 m resolution, yearly): China Land Cover Dataset (CLCD) available at (http://doi.org/10.5281/zenodo.4417809).

References

Zhao, L., Dai, A. & Dong, B. Changes in global vegetation activity and its driving factors during 1982–2013. Agric. Meteorol. 249, 198–209 (2018).

Gan, C. et al. Changes of vegetation coverage during recent 18 years in Lianjiang river watershed. Sci. Geogr. Sin. 31, 1019–1024 (2011).

Li, L. et al. Review of ground and aerial methods for vegetation cover fraction (fCover) and related quantities estimation: Definitions, advances, challenges, and future perspectives. ISPRS J. Photogramm Remote Sens. 199, 133–156 (2023).

Wei, Y., Sun, S., Liang, D. & Jia, Z. Spatial–temporal variations of NDVI and its response to climate in China from 2001 to 2020. Int. J. Digit. Earth. 15, 1463–1484 (2022).

Zhao, N., Zhao, Y. H., Zou, H. F., Bai, X. H. & Zhen, Z. Spatial and Temporal trends and drivers of fractional vegetation cover in Heilongjiang province, China during 1990–2020. Ying Yong Sheng Tai Xue bao = j. Appl. Ecol. 34, 1320–1330 (2023).

Hu, R. & Dong, L. B. Temporal and Spatial variations of vegetation coverage in Heilongjiang basin and its responses to climate change. Ying Yong Sheng Tai Xue Bao. 35, 1518–1524 (2024).

Zhang, H., He, Z., Zhang, L., Cong, R. & Wei, W. Spatial–Temporal changes and driving factor analysis of net ecosystem productivity in Heilongjiang Province from 2010 to 2020. Land 13, 1316 (2024).

Xi, Z. et al. Spatial and Temporal variation of vegetation NPP and analysis of influencing factors in Heilongjiang province, China. Ecol. Indic. 154, 110798 (2023).

Liu, Y. et al. Impacts of climate and land use/land cover change on water yield services in Heilongjiang Province. Water 16, 2113 (2024).

Feng, X. et al. Spatial heterogeneity and driving mechanisms of carbon emissions in urban expansion areas: A research framework coupled with patterns and functions. Land. Use Policy. 143, 107209 (2024).

Huang, X. et al. Exploring the optimal method for quantifying the contribution of driving factors of urban floods. Int. J. Appl. Earth Obs Geoinf. 140, 104597 (2025).

Lv, L. et al. A comparative study of model interpretability considering the decision differentiation of landslide susceptibility models. IEEE Trans. Geosci. Remote Sens (2024).

Qiao, B. et al. Nonlinear threshold effects of environmental drivers on vegetation cover in mountain ecosystems: From constraint mechanisms to adaptive management. Ecol. Indic. 173, 113328 (2025).

Liu, J. et al. Unraveling phenological dynamics: Exploring early springs, late autumns, and climate drivers across different vegetation types in Northeast China. Remote Sens. 17, 1853 (2025).

Chen, L. et al. Estimating the effects of natural and anthropogenic activities on vegetation cover: Analysis of Zhejiang province, china, from 2000 to 2022. Remote Sens. 17, 1433 (2025).

Deng, Y., Gao, S., Liu, L. & Jiang, W. Growing-season NDVI responses to climate change in China’s three major marsh wetland regions. Ecol. Indic. 175, 113581 (2025).

Li, L. et al. Divergent urbanization-induced impacts on global surface urban heat Island trends since 1980s. Remote Sens. Environ. 295, 113650 (2023).

Miao, Z. et al. Global dynamics of grassland FVC and LST and Spatial distribution of their correlation (2001–2022). Plants 14, 439 (2025).

Bandyopadhyay, A., Bhadra, A., Raghuwanshi, N. S. & Singh, R. Temporal trends in estimates of reference evapotranspiration over India. J. Hydrol. Eng. 14, 508–515 (2009).

Gocic, M. & Trajkovic, S. Analysis of changes in meteorological variables using Mann-Kendall and sen’s slope estimator statistical tests in serbia. Glob. Planet. Chang. 100, 172–182 (2013).

Zhang, J. et al. Spatiotemporal variations and its driving factors of NDVI in Northwest China during 2000–2021. Environ. Sci. Pollut Res. 30, 118782–118800 (2023).

Su, Y., Li, T., Cheng, S. & Wang, X. Spatial distribution exploration and driving factor identification for soil salinisation based on geodetector models in coastal area. Ecol. Eng. 156, 105961 (2020).

Liang, J. et al. Impacts of changing climate on the distribution of migratory birds in China: Habitat change and population centroid shift. Ecol. Indic. 127, 107729 (2021).

Zu, K. et al. Upward shift and elevational range contractions of subtropical mountain plants in response to climate change. Sci. Total Environ. 783, 146896 (2021).

Chen, Y. An analytical process of Spatial autocorrelation functions based on moran’s index. PLoS ONE. 16, e0249589 (2021).

Jackson, M. C., Huang, L., Xie, Q. & Tiwari, R. C. A modified version of moran’s I. Int. J. Health Geogr. 9, 1–10 (2010).

Kim, Y. & Kim, Y. Explainable heat-related mortality with random forest and Shapley additive explanations (SHAP) models. Sustain. Cities Soc. 79, 103677 (2022).

Zhang, Z., Song, Y. & Wu, P. Robust geographical detector. Int. J. Appl. Earth Obs Geoinf. 109, 102782 (2022).

Sun, H., Wang, H., Chen, C. & Kong, A. Spatial and Temporal characteristics of vegetation information in Zhejiang Province using the Google Earth engine. Int. Conf. Geogr. Inf. Remote Sens. Technol. (GIRST) 12552, 106–111 (2022).

Yang, Y., Wu, T., Zeng, Y. & Wang, S. An adaptive-parameter pixel unmixing method for mapping evergreen forest fractions based on time-series NDVI: A case study of Southern China. Remote Sens. 13, 4678 (2021).

Yang, S. et al. Vegetation coverage changes driven by a combination of climate change and human activities in Ethiopia, 2003–2018. Ecol. Inf. 71, 101776 (2022).

Wang, R., Wang, H., Wang, C., Duan, J. & Zhang, S. Spatial scale effect on fractional vegetation coverage changes and driving factors in the Henan section of the yellow river basin. Remote Sens. 16, 2575 (2024).

Xu, B. et al. Anthropogenic activities dominated the Spatial and Temporal changes of normalized difference vegetation index (NDVI) in the Hehuang Valley in the Northeastern Qinghai Province between 2000 and 2020. Front. Environ. Sci. 12, 1384032 (2024).

Zhang, J. & Zhang, Y. Quantitative assessment of the impact of the Three-North shelter forest program on vegetation net primary productivity over the past two decades and its environmental benefits in China. Sustainability 16, 3656 (2024).

Terschanski, J. et al. The role of vegetation structural diversity in regulating the microclimate of human-modified tropical ecosystems. J. Environ. Manag. 360, 121128 (2024).

Ma, Y., Huang, L., Li, J., Cao, W. & Cai, Y. Carbon potential of china’s grain to green program and its contribution to the carbon target. Resour. Conserv. Recycl. 200, 107272 (2024).

Xiao, Y., Zhao, J., Zhang, Y. & Wang, S. Grain self-sufficiency in Guangdong, China: Current trends and future perspectives. Foods 14, 1126 (2025).

Liu, C. et al. Detection of vegetation coverage changes in the yellow river basin from 2003 to 2020. Ecol. Indic. 138, 108818 (2022).

Liu, Y., Zhang, Y., Yu, M. & Dai, C. Impacts of climate and land use/land cover change on water yield services in Heilongjiang Province. Water 16, 2113 (2024).

Zhang, Y., Wan, P., Ma, G. & Pereira Uñate, P. A. Price, internet penetration and green food industry development: Based on the interaction between demand and supply. PLoS ONE. 18, e0289843 (2023).

Tuoku, L., Wu, Z. & Men, B. Impacts of climate factors and human activities on NDVI change in China. Ecol. Inf. 81, 102555 (2024).

Wu, Y., Qiu, X., Liang, D., Zeng, X. & Liu, Q. How the characteristics of land cover changes affect vegetation greenness in guangdong, a rapid urbanization region of China during 2001–2022. Environ. Monit. Assess. 196, 1020 (2024).

Zhao, K., Li, X., Zhang, Z. & Liu, X. Phenology of different types of vegetation and their response to climate change in the Qilian mountains, China. J. Mt. Sci. 21, 511–525 (2024).

Wang, Z., Wang, Z., Song, L. & Li, T. Characterization of Spatial and Temporal distribution of evapotranspiration in the Dawen river basin and analysis of driving factors. Environ. Earth Sci. 84, 1–13 (2025).

Mamattursun, A., Yang, H., Ablikim, K. & Obulhasan, N. Spatiotemporal evolution and driving forces of vegetation cover in the Urumqi river basin. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public. Health. 19, 15323 (2022).

Shen, X. et al. Critical role of water conditions in the responses of autumn phenology of marsh wetlands to climate change on the Tibetan plateau. Glob. Chang. Biol. 30, e17097 (2024).

Shi, X., Du, C., Guo, X. & Shi, W. Heterogeneity of water-retention capacity of forest and its influencing factors based on meta-analysis in the Beijing-Tianjin-Hebei region. J. Geogr. Sci. 31, 69–90 (2021).

Zhao, X., Tan, S., Li, Y., Wu, H. & Wu, R. Quantitative analysis of fractional vegetation cover in Southern Sichuan urban agglomeration using optimal parameter geographic detector model, China. Ecol. Indic. 158, 111529 (2024).

Liu, W. et al. Effect of elevation on variation in reference evapotranspiration under climate change in Northwest China. Sustainability 13, 10151 (2021).

Berg, A. & Sheffield, J. Historic and projected changes in coupling between soil moisture and evapotranspiration (ET) in CMIP5 models confounded by the role of different ET components. J. Geophys. Res. Atmos. 124, 5791–5806 (2019).

Satti, Z. et al. Effects of climate change on vegetation and snow cover area in Gilgit Baltistan using MODIS data. Environ. Sci. Pollut Res. 30, 19149–19166 (2023).

Ma, R. et al. Variation of vegetation autumn phenology and its Climatic drivers in temperate grasslands of China. Int J. Appl. Earth Obs. Geoinf. 114, 103064 (202 2).

Shen, X. et al. Spatiotemporal change of marsh vegetation and its response to climate change in China from 2000 to 2019. J. Geophys. Res. Biogeosci. 126, e2020JG006154 (2021).

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

Weidong Chen: Writing review & editing, Writing - original draft. Lei Shi & validation, Resources, Project administration, Investigation.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher’s note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if you modified the licensed material. You do not have permission under this licence to share adapted material derived from this article or parts of it. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Chen, W., Shi, L. Study on the driving mechanisms of spatiotemporal nonstationarity of vegetation dynamics in Heilongjiang Province. Sci Rep 15, 28844 (2025). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-14182-x

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-14182-x