Abstract

To explore the role of aldehyde-keto reductase (AKR) gene family in sweet cherry (Prunus avium L.) responses to abiotic stresses, we identified 38 PaAKR genes via bioinformatics and analyzed their expression under PEG6000 (drought), NaCl (salinity), and ABA (hormone) treatments. Evolutionary analysis classified these genes into 5 subfamilies, with cis-acting elements indicating involvement in stress and hormone signaling. Real-time PCR showed that 8 genes (PaAKR3, PaAKR6, PaAKR10, PaAKR12, PaAKR17, PaAKR24, PaAKR28, PaAKR34) were strongly responsive to all three treatments. These findings highlight the potential of PaAKRs in mediating abiotic stress adaptation in sweet cherry and provide key candidate genes for enhancing stress resistance through functional studies.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Sweet cherry (Prunus avium L.), belonging to the Cerasus subgenus of the Rosaceae family, is a perennial plant. It is widely used in fruit production and landscape gardening due to its unique flavor and high nutritional value. In China, sweet cherries are mainly cultivated in the Bohai Bay region, and high-altitude areas in Southwest China1. With the continuous expansion of cultivation areas to the west and north, soil salinization has intensified, and climate factors such as low average temperatures have limited the quality and yield of sweet cherries. Therefore, improving the adaptability of sweet cherries to harsh environments is crucial for promoting industrial development2.

Throughout the growth and development cycle of plants, their living environments are constantly challenged by diverse abiotic stresses. Environmental adversities such as high temperature3, drought4, and saline-alkali stress5 continuously threaten plant physiological functions and metabolic homeostasis. To cope with these stresses, plants have evolved complex adaptive regulatory mechanisms through long-term evolution, achieving stress responses via multi-level molecular network reconstruction. Among them, the aldehyde-keto reductase (AKR) family, as an important metabolic regulator, plays a core role in plant stress response pathways6. Studies on gene expression regulation under stress conditions have shown that plants can adapt to environmental changes by dynamically regulating the transcriptional levels of AKR genes7. For example, in a drought stress model, 75% of AKR gene family members in tomato plants showed significant upregulation after 24 h of drought treatment, but their transcriptional levels declined after 48 h of stress7. A similar temporal pattern was observed in PaAKR genes under PEG6000 treatment: most genes were upregulated at 12 h but downregulated by 48 h, suggesting conserved stage-specific regulatory mechanisms in AKR-mediated drought response across species. This dynamic expression may enable cherry to rapidly activate stress defenses in early stages and adjust metabolic resources in prolonged stress, providing insights into the evolutionary conservation of stress adaptation strategies. This temporal expression pattern reveals that plants establish stage-specific stress resistance mechanisms by finely regulating the spatiotemporal expression of AKR genes. Molecular genetics studies have further confirmed the indispensability of AKR proteins in stress responses through functional verification experiments. AKR functional knockout mutants constructed using gene knockout technology exhibited obvious phenotypic defects under the same stress conditions, while overexpression of specific AKR genes through transgenic technology significantly enhanced plant stress resistance. These experimental results confirm from both positive and negative aspects that the expression products of AKR genes are key functional components maintaining plant stress adaptability. For instance, the AKR family primarily exerts stress resistance functions by regulating signal transduction networks and metabolic pathways. In oxidative stress responses, AKR proteins participate in the fine regulation of reactive oxygen species (ROS) metabolic pathways by catalyzing the reduction of toxic aldehyde and ketone metabolites, inhibiting excessive ROS accumulation, and thus alleviating oxidative damage such as membrane lipid peroxidation to cells8. In hormone regulatory networks, the expression products of AKR genes can indirectly regulate downstream signal transduction cascades by influencing the metabolism of stress-related hormone precursors such as abscisic acid (ABA) and ethylene (ET), thereby regulating stress resistance physiological processes such as stomatal closure and osmolyte synthesis. This multi-pathway co-rregulation mechanism constitutes the molecular basis for plants to cope with complex stresses. However, research on AKR genes in sweet cherry remains limited. Prior studies have not systematically identified PaAKR family members or their roles in abiotic stress responses, leaving a critical gap in understanding how cherry adapts to harsh environments (e.g., soil salinization in northwest China). This study addresses this gap by characterizing PaAKR genes and their expression under drought, salinity, and ABA stress, laying a foundation for improving cherry stress resistance.

In the field of life science research, studies on AKR genes have been relatively advanced in animal cells and humans9. In contrast, although research in plants has gradually developed, genome-wide identification of this gene family has been completed in species such as tomato7, Medicago truncatula6, and maize10. Given this, this study focuses on the response mechanism of sweet cherry to abiotic stresses, aiming to systematically explore the bioinformatics characteristics of sweet cherry AKR family genes and their expression patterns under abiotic stress conditions. Taking sweet cherry’s response to abiotic stresses as an entry point, this study uses bioinformatics methods to analyze the physicochemical properties and protein structures of sweet cherry AKR family genes, and preliminarily investigates their expression under abiotic stress conditions through qRT-PCR, providing a theoretical reference for improving cherry’s resistance to abiotic stresses.

Materials and methods

Materials and treatments

The experiment used rooting test-tube seedlings of sweet cherry (Prunus avium L.) provided by the Fruit Tree Tissue Culture Laboratory of the College of Horticulture, Gansu Agricultural University. Test-tube seedlings with robust growth and similar vigor, cultured for 40 days, were treated with 15% PEG6000 (simulated drought), 100 μmol·L⁻1 ABA, and 200 mmol·L⁻1 NaCl (simulated salinity) via root irrigation (500 mL per pot), with an equal volume of distilled water as the control. These concentrations were chosen based on prior studies on Rosaceae plants7,11, which demonstrated effective induction of stress responses without causing lethal damage. The culture conditions were 25 °C with 16 h of light (2500–2800 lx) and 20 °C with 8 h of darkness, and the treatment duration was 24 h. Each treatment included 9 cherry plants, with 3 biological replicates. Leaves of treated cherry potted seedlings were collected, quickly frozen in liquid nitrogen, and stored at − 80 °C for later use.

RNA extraction and quality inspection

Cherry RNA was extracted using the plant kit RNAplan-RTR2303 (Zhongkeruitai Biotechnology Co., Ltd., Beijing). The extracted RNA was detected for purity (OD₂₆₀/OD₂₈₀), concentration, and integrity using Nanodrop and Agilent 2100 (Agilent LLC, USA), RNA integrity number (RIN) > 8.0 (Supplementary table S1). After confirmation of qualification, it was stored at − 80 °C12.

Identification of the cherry AKR gene family

Protein sequences of the family genes were downloaded from the genome database (https://www.rosaceae.org/). The hidden Markov model file (PF00248) of the specific AKR domain was downloaded from the Pfam database (Pfam, Home page: xfam.org). The HMMER 3.0 program was used for genome-wide identification of sweet cherry AKR at a preliminary E-value < 1 × 10–6. To avoid redundancy, only the longest transcript was retained for each gene locus, and splice variants were excluded. After domain validation via SMART (https://smart.embl-heidelberg.de/), sequences with incomplete AKR domains (PF00248) were manually removed, resulting in 38 non-redundant PaAKR genes. And named PaAKR1–PaAKR38 according to their chromosomal positions.

Phylogenetic evolution, protein physicochemical properties, and subcellular localization analysis of the cherry AKR family genes

Multiple alignments of amino acid sequences of Arabidopsis and cherry AKR were performed using ClustalX13. The MEGA7.0 software was used to construct a phylogenetic tree of the AKR gene family, and the constructed phylogenetic tree was bootstrapped with parameters set as P-distance, pairwise deletion, and 1000 bootstrap replicates, with other parameters as defaults14. Finally, the online website Chiplot (https://www.chiplot.online/) was used for beautification15. The PotParem tool in the EXPASy database (https://web.expasy.org/protparam/) was used to analyze basic information such as the theoretical isoelectric point, amino acid length, molecular weight, and instability index of proteins. Subcellular localization prediction was performed using WoLF PSORT (https://wolfpsort.hgc.jp/). In addition, the PaAKR28 gene with the stop codon removed was constructed into the pCAMBIA2300-GFP vector, using BamhI as the restriction enzyme site, for the purpose of observing its subcellular localization16,17.

Analysis of gene structure, motif, and related informatics of the cherry AKR family

TBtools was used for visualization of gene structures, Motifs18, and conserved domains. The plan CARE software (http://bioinformatics.psb.ugent.be/webtools/plantcare/html/) was used to analyze and predict cis-acting elements in the 2000 bp upstream of the gene19, and TBtools was used for mapping. The condonW tool was used for codon bias analysis of the PaAKR gene family, and Tbtools was used for visualization20.

Intraspecific and interspecific collinearity analysis and protein interaction analysis

Intraspecific collinear genes in cherry and interspecific collinear genes among cherry, Arabidopsis, and apple were analyzed and mapped using TBtools21. PaAKR proteins were analyzed in the STRING database (https://cn.string-db.org/cgi/input?sessionId=bqa1ej5pJX8z&input_page_active_form=single_sequence)22, and mapped using Cytoscape23.

Real-time fluorescence quantification

qRT-PCR primers for the obtained AKR genes were designed and synthesized using the website of Sangon Biotech (Shanghai) Co., Ltd. (https://store.sangon.com/newPrimerDesign) (Table 1). cDNA was reverse-transcribed using the Prime Script RT reagent Kit (Perfect Real Time) (TaKaRa, Japan), and the reverse-transcribed products were stored at − 20 °C for later use. SYBR Piner Ex TaqTM II (TaKaRa, Japan) kit and Light Cycler®96 Real-Time PCR System (Roche, Switzerland) were used for qRT-PCR. Cherry RPL was used as an internal reference gene, and the reaction program was 30 s at 95 °C for pre-denaturation, 10 s at 95 °C for denaturation, 30 s at 60 °C for annealing, and 30 s at 72 °C for extension, for a total of 40 cycles16.

Data statistics and analysis

Data statistics were performed using Excel 2010, significant differences were analyzed using SPSS22.0, and drawing was performed using Origin 9.0.

Results

Phylogenetic analysis of the cherry AKR family genes

To explore the evolutionary relationships of PaAKR gene family, a phylogenetic tree of 60 genes from cherry and Arabidopsis was constructed using MEGA7.0, which was divided into 4 subfamilies (Fig. 1). Subfamily D contained the most members (25), including 15 PaAKRs. Expression analysis showed that 7 of these 15 PaAKRs (e.g., PaAKR3, PaAKR10) were strongly upregulated under all stress treatments, suggesting functional conservation in stress response within this subfamily, potentially due to subfunctionalization during evolution. Subfamily C had the fewest gene members, with only 5, including 3 from cherry and 2 from Arabidopsis.

Physicochemical property analysis and subcellular localization of sweet Cherry AKR family proteins

As shown in Table 2, the physicochemical properties of different PaAKR family genes varied. PaAKR23 had the highest number of amino acids and molecular weight, with 493 amino acids and 55.08 kD, respectively, while PaAKR7 had the lowest, with 86 amino acids and 9.03 kD. Sixteen PaAKR proteins had a theoretical isoelectric point higher than 7, with PaAKR17 and PaAKR20 having the highest at 9.37; 22 PaAKR proteins had a theoretical isoelectric point lower than 7, with PaAKR7 having the lowest at 4.4. The instability index, aliphatic index, and grand average of hydropathicity ranged from 20.56 to 67.49, 61.63 to 105.58, and − 0.431 to 0.348, respectively. In addition, subcellular localization prediction showed that PaAKR was mainly distributed in chlo, cyto, and nucl. A few genes were present in vacu, extr, mito, plas, etc. Meanwhile, the subcellular localization of PaAKR28 was determined and it was found to be mainly located in the nucleus (Fig. 2), which was consistent with the predicted result. Based on a comprehensive analysis, it can be concluded that PaAKRs with higher hydrophobicity (e.g., PaAKR7, GRAVY = 0.348) were predominantly localized to extracellular regions, while hydrophilic proteins (e.g., PaAKR5, GRAVY = -0.338) were more common in chloroplasts. Additionally, genes with low instability indices (e.g., PaAKR3, 20.56) showed stable upregulation under stress, suggesting structural stability may contribute to consistent stress responses.

Motif, domain, and structure analysis of sweet cherry AKR family genes

As shown in Fig. 3, TBtools software was used to analyze the conserved motifs of 38 proteins in the PaAKR gene family. Ten PaAKR proteins had similar types and numbers of conserved motifs, namely PaAKR11 ~ 15, PaAKR22, and PaAKR25 ~ 28. Meanwhile, 11 PaAKR proteins had similar numbers and types of Motifs, namely PaAKR1 ~ 3, PaAKR6, PaAKR8, PaAKR24, and PaAKR30 ~ 34. PaAKR16, PaAKR18, and PaAKR22 had only 2 Motifs, Motif5 and Motif6. Conserved domain analysis showed that all 38 PaAKR genes contained AKR domains, with 10 different types of domains and long fragments. Furthermore, Motif4 was conserved across all PaAKRs, and stress-responsive genes (e.g., PaAKR3, PaAKR28) contained additional Motif2 and Motif5, which may be involved in stress signaling. This suggests that specific motifs could determine the functional divergence of PaAKRs under stress.

Chromosomal localization of sweet cherry AKR family genes

Visualization analysis of the chromosomal positions of PaAKR family genes using TBtools (Fig. 4) revealed that 38 PaAKR genes were localized on 7 chromosomes, with no PaAKR genes present on chromosome 4 (chr_4). Chromosome chr_1 had the most PaAKR family genes, with 14, accounting for 36.8% of all PaAKR family genes; followed by chromosome chr_6 with 12 PaAKR family genes, accounting for 31.6%. The clustering of 68.4% PaAKRs on chr_1 and chr_6 is likely due to tandem duplications, as indicated by collinearity analysis (Fig. 5A), which showed 3 pairs of tandemly duplicated genes (e.g., PaAKR1 and PaAKR30). This expansion may enhance cherry’s ability to respond to diverse stresses.

Analysis of Cis-acting elements and gene structures in the 2000 bp upstream of sweet cherry AKR family genes

In this experiment, the PlantCARE online software was used to analyze the promoter sequences 2000 bp upstream of PaAKR family genes, and TBtools was used for visualization (Fig. 5). The PaAKR family genes contained various functional cis-acting elements, including multiple environmental signal-responsive elements such as defense and stress response elements (TC-rich repeats), low temperature (LTR), drought induction (MBS), and anaerobic induction (ARE) response elements; multiple hormone-responsive elements such as gibberellin (TATC-box, GARE-motif, P-box), abscisic acid (ABRE), methyl jasmonate (CGTCA-motif and TGACG-motif), salicylic acid (TCA-element), and auxin (AuxRR-core, TGA-element) response elements; plant growth and development-regulating elements such as meristem (CAT-box) elements; and light-responsive (G-box, GT1-motif, GATA-motif, TCT-motif, and MRE) elements and wound-responsive (WUN-motif) elements. This indicates that the PaAKR family genes play important roles in responding to drought stress, hormone regulation, anaerobic induction, and defense and stress responses. Further analysis revealed that PaAKR genes with ABRE elements (e.g., PaAKR3, PaAKR17) showed significant upregulation under ABA treatment, confirming the functional relevance of these elements in hormone-mediated stress responses.

Structural analysis of PaAKR genes showed that the PaAKR24 had a distinct gene structure (fewer exons) and unique expression: it was upregulated under NaCl and ABA but not PEG6000, suggesting functional specialization in salinity and hormone responses. Additionally, the number of exons in PaAKR genes ranged from 2 to 10. Analysis also found that 16 genes (PaAKR2, PaAKR3, PaAKR7, PaAKR12, PaAKR16, PaAKR20, PaAKR21, PaAKR22, PaAKR23, PaAKR29, PaAKR33, PaAKR34, PaAKR35, PaAKR36, PaAKR37, and PaAKR38) lacked 5’ and 3’ UTRs.

Collinearity analysis of sweet cherry AKR family genes

To further understand the evolutionary forces of PaAKR family genes, TBtools was used to analyze 3 pairs of PaAKR gene pairs (Fig. 6A), namely PaAKR11 and PaAKR22, PaAKR1 and PaAKR30. Collinearity analysis of 38 PaAKRs with their corresponding Arabidopsis and apple genes showed that there were 8 pairs and 31 pairs of homologous genes between sweet cherry and Arabidopsis, and between sweet cherry and apple, respectively (Fig. 6B), indicating a closer evolutionary relationship between sweet cherry and apple.

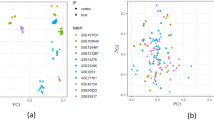

Analysis of codon bias in the ARK gene family of sweet cherry

An analysis of codon bias parameters for the ARK gene family in forest sweet cherry (Fig. 7A, Table 3) revealed that the total GC content in sweet cherry ranged from 0.424 to 0.534, with an average of 0.464. The frequency of guanine (G) or cytosine (C) at the third base position (GC3s) ranged from 0.335 to 0.593, with an average of 0.432. Additionally, the average frequencies of thymine (T), cytosine (C), adenine (A), and guanine (G) at the third base position of codons (T3s, C3s, A3s, G3s) were 0.395, 0.273, 0.301, and 0.282, respectively.

The effective number of codons (ENc), which reflects the degree of codon bias, ranges from 20 to 60. A value closer to 20 indicates stronger codon bias. The ENc values for the ARK gene family in sweet cherry ranged from 42.01 to 61, with an average of 54.595.

Correlation analysis of the third codon base, codon adaptability, codon bias index, optimal codon usage frequency, effective codons, GC content at the third codon base, and overall GC content showed extremely significant correlations between T3s and C3s, T3s and GC3s, C3s and GC3s, A3s and GC3s, CAI and CBI, CAI and Fop, and CBI and Fop (Fig. 7B).

Expression analysis of the AKR gene family in sweet cherry under abiotic stresses

Sweet cherry tissue-cultured seedlings were subjected to stress treatments with PEG6000, NaCl, and ABA for 12, 24, and 48 h, respectively. The expression profiles of 38 PaAKR genes were analyzed by qRT-PCR (Fig. 8). As shown in Fig. 7, after 12 h of ABA treatment, 89.5% of the genes exhibited increased expression levels. At 24 h post-treatment, the expression of most genes decreased, with only 73.6% of the genes maintaining high expression levels. By 48 h, 39.5% of the genes were upregulated, among which PaAKR3, PaAKR17, and PaAKR34 (13 genes in total) showed the highest expression levels.

After 12 h of NaCl stress, 26.3% of the genes were upregulated, with the highest expression observed in PaAKR6, PaAKR10, PaAKR12, PaAKR24, and PaAKR28. At 24 h of NaCl stress, 23 genes showed high expression levels, with PaAKR28 having the highest expression. At 48 h, 28 genes were upregulated, with expression levels higher than those at 12 and 24 h. In most genes, their expression levels gradually decrease after long-term treatment with polyethylene glycol (but still higher than CK). However, PaAKR3 is an exception (with an expression level of 23.21 ± 1.53 times at 12 h) (Supplementary table S2), indicating that it plays a role in rapidly responding to drought stress signals, possibly through unique regulatory elements.

Discussion

In this study, a total of 38 members of the PaAKR family were identified in sweet cherry, which is larger than the number in plants such as tomato (28 members)7 and Arabidopsis thaliana (21 members)11. The larger PaAKR family (38 members) compared to tomato and Arabidopsis may result from tandem duplications (chr_1 and chr_6), enabling cherry to adapt to diverse stresses in its cultivation range (e.g., high altitude, salinity). The variation in the number of AKR family members across species may be attributed to differences in evolutionary processes24. In the phylogenetic tree, closer clustering distances indicate a higher likelihood that these genes perform similar functions. The analysis revealed that AKR family members from Arabidopsis and forest sweet cherry can be divided into five subfamilies, with members distributed across different subfamilies. Notably, subfamilies D and E contain only one Arabidopsis AKR family member each. Physicochemical property analysis showed significant differences in the number of amino acids among PaAKR gene family members, with a maximum difference of 200 amino acid residues between different members. The isoelectric points of proteins encoded by PaAKR family genes range from 5.19 to 9.76, and they are predicted to localize in the cytoplasm, chloroplasts, and nucleus, similar to findings in alfalfa6.

Conserved motif analysis indicated that the distribution order of motifs in the PaAKR family is relatively conserved, with Motif4 being shared by all PaAKR family members. This suggests that Motif4 is the primary motif determining the conserved function of the family. Diverse gene structures play a crucial role in the evolution of multigene families25. Our results showed that PaAKR family genes have varying numbers of exons and introns, indicating potential functional divergence among members. Collinearity analysis revealed that three pairs of genes may exhibit collinear relationships. Collinear gene pairs (e.g., PaAKR11 and PaAKR22) showed similar expression patterns under NaCl stress (both upregulated at 24 h), suggesting conserved functions. This is further supported by shared motif compositions, indicating functional constraint during evolution. Many studies have shown that plants regulate target gene expression by combining transcription factors with cis-acting elements to respond to abiotic stresses. Analysis of the 2000 bp upstream promoter sequences of PaAKR family genes identified cis-acting elements related to environmental signal responses, hormone regulation, plant growth and development, and light reactions, suggesting their potential positive regulatory roles in stressful environments.

Expression profiles of the sweet cherry AKR family under abiotic stresses were analyzed using qRT-PCR. Seven family members showed significantly induced expression by abiotic stresses such as ABA, NaCl, and PEG6000, while three members actively responded to NaCl and ABA stresses. Highly responsive genes (e.g., PaAKR28) contain multiple stress-related cis-elements (e.g., ABRE, MBS) and conserved Motif2/10, which may enhance their transcriptional activation under stress. This suggests that their promoter and motif structures contribute to stress sensitivity. Previous studies have shown that AKR family genes in Arabidopsis are significantly upregulated under high-concentration salt stress11, and alfalfa AKR genes play important roles in the defense system under similar conditions26. Additionally, cloning of tomato AKR genes27. These findings are consistent with the expression patterns of sweet cherry AKR genes under salt stress.

In conclusion, this study identified 38 PaAKR family genes. Expression analysis based on qRT-PCR confirmed the hypothesis that PaAKR genes play important roles in responding to various environmental stimuli and stress conditions in sweet cherry, providing candidate genes for studying growth, development, and stress resistance in sweet cherry.

Conclusion

This study identified 38 PaAKRs, with 8 genes strongly responsive to abiotic stress. Limitations include the lack of functional validation (e.g., CRISPR/Cas9 knockouts or overexpression lines). Future work should focus on characterizing core genes (e.g., PaAKR28) to elucidate their roles in stress adaptation, aiding cherry breeding for stress resistance.

Data availability

All data generated or analysed during this study are included in this published article.

References

Zhang, K. et al. Sweet cherry growing in China (Conference Paper). Acta Horticult. 1235, 133–140 (2019).

Sekse, L. & Lyngstad, L. Strategies for maintaining high quality in sweet cherries during harvesting, handling and marketing (Conference Paper). Acta Hort. 410(410), 351–355 (1996).

Zhou, C. et al. Response mechanisms of woody plants to high-temperature stress. Plants (Basel, Switzerland) 12(20), 3643 (2023).

Ma, W.-F. et al. Changes and response mechanism of sugar and organic acids in fruits under water deficit stress. PeerJ 10, e13691 (2022).

Wei, L. et al. TaWRKY55–TaPLATZ2 module negatively regulate saline–alkali stress tolerance in wheat. J. Integr. Plant Biol. 67(1), 19–34 (2025).

Yu, J. et al. Analysis of Aldo-Keto Reductase gene family and their responses to salt, drought, and abscisic acid stresses in Medicago truncatula. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 21(3), 754 (2020).

Guan, X., Yu, L. & Wang, A. Genome-wide identification and characterization of Aldo-Keto Reductase (AKR) gene family in response to abiotic stresses in Solanum lycopersicum. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 24(2), 1272 (2023).

Huo, J. et al. A novel aldo-keto reductase gene, IbAKR, from sweet potato confers higher tolerance to cadmium stress in tobacco. Front. Agricult. Sci. Eng. 5(02), 206–213 (2018).

Oberschall, A. et al. A novel aldose/aldehyde reductase protects transgenic plants against lipid peroxidation under chemical and drought stresses. Plant J. 24(4), 437–446 (2010).

Sousa, S. M. d. et al. Structural and kinetic characterization of a maize aldose reductase. Plant Physiol. Biochem. 47(2), 98–104 (2009).

Simpson, P. J. et al. Characterization of two novel aldo-keto reductases from Arabidopsis: Expression patterns, broad substrate specificity, and an open active-site structure suggest a role in toxicant metabolism following stress. J. Mol. Biol. 392(2), 465–480 (2009).

Ma, W. et al. Profiling the lncRNA–miRNA–mRNA interaction network in the cold-resistant exercise period of grape (Vitis amurensis Rupr.). Chem. Biol. Technol. Agricult. 11(1), 1–15 (2024).

Larkin, M. A. et al. Clustal W and Clustal X version 2.0. Bioinformatics (Oxford, England) 23(21), 2947–2948 (2007).

Kumar, S., Stecher, G. & Tamura, K. MEGA7: Molecular evolutionary genetics analysis version 7.0 for bigger datasets. Mol. Biol. Evolut. 33(7), 1870–1874 (2016).

Xie, J. et al. Tree Visualization By One Table (tvBOT): A web application for visualizing, modifying and annotating phylogenetic trees. Nucleic Acids Res. 51(W1), W587–W592 (2023).

Ma, W. et al. Analysis of Apple MPC gene family and validation of MdMPC5 improving Arabidopsis salt-tolerance. Sci. Horticult. 342, 342114027 (2025).

Lan, G. et al. Grape SnRK27 positively regulates drought tolerance in transgenic arabidopsis. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 25(8), 4473 (2024).

Bailey, T. L. et al. MEME Suite: Tools for motif discovery and searching. Nucleic Acids Res. 37(Suppl 2), W202–W208 (2009).

Lescot, M., Dehais, P. & Thijs, G. PlantCARE, a database of plant cis-acting regulatory elements and a portal to tools for in silico analysis of promoter sequences. Nucleic Acids Res. 30(1), 325–327 (2001).

Lu, S. et al. Insight into VvGH3 genes evolutional relationship from monocotyledons and dicotyledons reveals that VvGH3-9 negatively regulates the drought tolerance in transgenic Arabidopsis. Plant Physiol. Biochem. 172(Suppl C), 70–86 (2022).

Ren, J. et al. Evolution of the 14-3-3 gene family in monocotyledons and dicotyledons and validation of MdGRF13 function in transgenic Arabidopsis thaliana. Plant Cell Rep. 42(8), 1345–1364 (2023).

Che, L. et al. Identification and expression analysis of the grape pentatricopeptide repeat (PPR) gene family in abiotic stress. Physiol. Mol. Biol. Plants 28(10), 1849–1874 (2022).

Mousavian, Z. et al. StrongestPath: A Cytoscape application for protein–protein interaction analysis. BMC Bioinform. 22(1), 352 (2021).

Velasco, R., Zharkikh, A., Affourtit, J. et al. The genome of the domesticated apple (Malus x domestica Borkh.). Nat. Genet. 42(10): 833-+ (2010).

Lysak, M. A. et al. Chromosome triplication found across the tribe Brassiceae. Genome Res. 15(4), 516–525 (2005).

Eltelib, H. A., Fujikawa, Y. & Esaka, M. Overexpression of the acerola (Malpighia glabra) monodehydroascorbate reductase gene in transgenic tobacco plants results in increased ascorbate levels and enhanced tolerance to salt stress. S. Afr. J. Bot. 78, 295–301 (2012).

Cai, X. et al. Ectopic expression of FaGalUR leads to ascorbate accumulation with enhanced oxidative stress, cold, and salt tolerance in tomato. Plant Growth Regul. 76(2), 187–197 (2015).

Funding

This work was financially supported by Central Guiding Local Science and Technology Development Fund Project (25ZYJE001), Gansu Provincial Key Research and Development Program Project (24YFNE002), Tianshui City Qinzhou District Major Science and Technology Special Project (2023-NCKJG-8373), Gansu Provincial Science and Technology Plan Rural Revitalization Special Project (24CXNE002), the Youth Doctoral Support Program of Gansu Province’s Colleges and Universities (2024QB-124) and Research on Efficient Utilization of Soil Water and Fertilizer in Dryland Orchards (TD22024-4).

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

Conceptualization, Guo Zhigang; methodology, Guo Zhigang, An Xiaojuan and Deng Fei; investigation, Guo Zhigang and An Xiaojuan; data curation, An Xiaojuan, Deng Fei and Zou Yali; writing—original draft preparation, Guo Zhigang; writing—review and editing, An Xiaojuan and Zou Yali; and funding acquisition, An Xiaojuan. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher’s note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Supplementary Information

Below is the link to the electronic supplementary material.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if you modified the licensed material. You do not have permission under this licence to share adapted material derived from this article or parts of it. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Guo, Z., An, X., Zou, Y. et al. Identification of the AKR gene family in sweet cherry and its response to different abiotic stresses. Sci Rep 15, 29251 (2025). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-14284-6

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-14284-6