Abstract

Missing gene expression values are a common issue in RNAseq-based analyses of gene expression. However, an analysis of genetic and environmental factors contributing to data missingness in RNAseq-based assessment of gene expression has never been conducted. In this study we tried to identify factors in RNAseq data missingness. We used RNAseq data from 66 lung adenocarcinoma tumors and corresponding adjacent normal lung tissues. We found a strong negative association between the gene expression level and missingness, supporting the idea that the borderline expression level is a key contributor to missingness. In a more detailed analysis, the relationship between gene expression and missingness was more complex: while the expected negative association between missingness and the expression level was observed for genes with low missingness, mean expression spiked at the right end of the distribution which included genes with very high missingness. We hypothesized that genes with a high missing rate include not only genes with borderline expression but also genes with high expression in some individuals but no expression in others (true biological missingness, TBM). The results of the comparative analysis of missingness in smokers and nonsmokers, an examination of the proportion of known tobacco smoke-sensitive genes by missing rate, and gene enrichment analysis support the hypothesis. We argue that it would be beneficial first to check data for the presence of genes with true biological missingness. The presence of highly expressed genes with missingness is an indication of TBM related to inter-individual variation in gene expression level. The results of our analysis call for caution in indiscriminatory imputation of missing values. When true biological missingness is present, it is advisable to identify genes with true biological missingness and analyze them separately because including such genes in imputation will lead to a bias: expression values will be assigned to a subset of the genes that are not expressed.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

RNAseq technology revolutionized gene expression analysis allowing investigators to reliably quantify the transcriptome1,2. The basic idea behind using RNAseq for the assessment of gene expression is to count the number of RNA fragments mapped to a given gene after accounting for the gene size and sequencing depth3. The common issue with using RNAseq for gene expression analysis is the presence of missing values: in a typical RNAseq study a considerable number of genes may have missing values4,5. Genes with missing values tend to be genes with low expression at or below a borderline level of detection for a given read depth6. Low RNA counts sometimes are considered unreliable and are excluded from downstream analyses by setting some minimal count threshold7. However, excluding genes with a high number of missing values from the analysis is considered disadvantageous due to loss of information and suboptimal statistical power8,9. A number of statistical approaches were developed to impute missing values in RNAseq studies10,11,12.

Bulk RNAseq is commonly used to quantify gene expression2,13. In RNAseq analysis the gene expression level is assessed by the number of sequencing reads mapped to a given gene after processing of the sequencing data14. Data processing includes normalization steps that take into account inter-individual differences in library sizes (the total number of reads) as well as differences in gene size15,16. It is common to have samples where for a given gene, the number of mapped reads is zero – missing data17,18. There is a general agreement that missing data represent technical or analytical artefacts related to the borderline expression level. When the expression level of the gene is low, the corresponding RNA is detected in some samples and not in others. It is generally accepted that it is beneficial to impute missing data since it allows keeping all genes and samples in the analysis19.

The goal of this study is to put forward the idea that missingness can be a real biological phenomenon related to the inter-individual variation in gene expression. When samples are drawn from a heterogeneous group of individuals some of which strongly expressed a given gene while others did not express it at all, it will result in data missingness in the RNAseq analysis. We propose to call it a true biological missingness (TBM). Genes with true biological missingness need to be excluded from imputation of missing data because assigning some expression level to the genes that are NOT expressed will lead to biases in downstream analyses.

The results of this study call for caution in indiscriminate application of imputation in RNAseq analyses. We seek to convince researchers to embrace a more prudent approach to imputation of missing data and propose several intermediate steps to identify genes with natural biological missingness. It will be more beneficial to analyze such genes separately and exclude them from imputation of the missing data.

The goal of our study was to analyze the relationship between missingness and gene expression to identify sources of missingness in RNAseq analyses by using RNAseq data from tumor and corresponding normal tissue samples obtained from surgically resected and well-characterized lung adenocarcinoma patients.

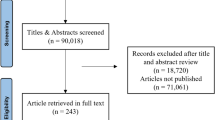

Methods

Samples

This study was performed in accordance with Institutional Review Board protocol at Baylor College of Medicine (H-35782). Informed consent was obtained for the collection of clinical data and biospecimens. A prospectively maintained, single-institution database was retrospectively queried. Eligible patients were patients with histologically confirmed lung adenocarcinoma who underwent complete surgical resection from 2017 to 2021. We used samples from tumor and adjacent normal tissues acquired from the patients diagnosed with stage I-IIIA lung adenocarcinoma and surgically treated at Baylor College of Medicine. A total of 66 patients with qualified paired tumor and adjacent non-neoplastic samples were selected for the study. Table 1 provides a concise description of patient characteristics.

aContinuous variables, mean (SD); categorical, n (%).

RNA sequencing and data processing

Total RNA was extracted from lung tumors and adjacent normal tissues using the RNeasy Plus Kit (Qiagen, Cat# 74134) following the manufacturer’s protocol. The quality of each RNA sample was thoroughly assessed to ensure high purity and integrity. These RNA samples were then used to prepare sequencing libraries, which were sequenced on the NovaSeq 6000 system (Illumina, San Diego) at the Human Genome Sequencing Core, targeting a minimum of 80 million reads per sample. The samples underwent Illumina TruSeq Stranded Total RNA with Ribo-Zero Globin depletion that removed rRNA and globin mRNA. The sequencing data were processed using the STAR aligner20 for alignment and the RSEM quantification tool21 for transcript quantification. For constructing the index, we used the reference genome and corresponding annotation files (FASTA and GTF formats) obtained from the GENCODE database (https://www.gencodegenes.org/human/). Gene expression levels were quantified in transcripts per million (TPM) and fragments per kilobase of transcript per million mapped reads (FPKM) units. These results were further integrated with gene annotation information, including gene names, chromosome coordinates, and other relevant genomic features. To ensure accurate and comparable results across samples, we applied quantile normalization using the scikit-learn library, adjusting the distribution of expression levels to minimize technical biases22. Mean expression levels for all relevant categories were computed, including only non-zero values to avoid skewing the results.

Definition of missingness

We considered expression as missing if no value was reported for the corresponding RNA in a sample, while at least one sample in our set had a non-zero value reported for this RNA. Missing rate (for an RNA or an RNA species) was defined as the number of samples with the missing value for the corresponding RNA over the total number of samples. We also use the term missingness, which is defined as the number of samples with the missing value for the corresponding RNA. To estimate correlation between missingness in tumor and adjacent normal tissue for each gene we obtained the numbers of missing values separately for tumor and adjacent normal tissue and computed Pearson’s correlation coefficient across all gene pairs. This was done separately for the four most common RNA species (protein coding, lncRNA, processed and unprocessed pseudogenes).

Results

Different RNA species differ by missing rate

A total of 29 different RNA species (types) were detected in the study (Table 2). The four most common RNA species were protein coding, long noncoding (lnc) RNA, processed pseudogenes, and unprocessed pseudogenes, together accounting for 92% of all RNAs. We focus on the analysis of missingness in these 4 most common RNA types. There is a significant variation in mean missingness across the four most common RNA species, with protein coding RNA having the lowest missing rate, followed by lncRNA, processed and unprocessed pseudogenes (see Table 2).

There is a strong positive correlation between gene expression in tumor and adjacent normal tissues

We noted a significant positive association between mean expression of the genes in adjacent normal and tumor tissues (Fig. 1). Pearson correlation coefficients between mean expressions in normal versus tumor tissues were computed separately for four most common RNA species: protein coding (N = 19,509), lncRNA (N = 17,141), processed pseudogenes (N = 9,148), and unprocessed pseudogenes (N = 1,879). The correlation measured by Pearson’s ρ was high, varying from 0.82 for processed pseudogenes to 0.93 for protein coding RNAs; all correlation coefficients are extremely significant with p ≤ 2.1 × 10− 34.

There is a very strong positive correlation between missingness in tumor and adjacent normal tissue for protein coding genes: Pearson’s ρ = 0.97, N = 19,509, p ≤ 3.1 × 10− 45. The corresponding correlation coefficients for lncRNA, Processed pseudogenes, and unprocessed pseudogenes were 0.98, 0.95 and 0.97, respectively. Based on these observations, we studied the association between gene expression and missingness jointly for adjacent normal and tumor tissues.

The distribution of missingness across different RNA species

For the four most common RNA species we estimated fractions of genes in each category of missingness. Analysis was done jointly for tumor and adjacent normal samples. Figure 2 shows the distributions of coding, lncRNAs, processed and unprocessed pseudogenes. For lncRNA, processed and unprocessed pseudogenes the distributions are U-shaped, while for protein coding RNAs it is more L-shaped with a high proportion of samples without missing data. The stratified analysis with tumor and adjacent normal samples analyzed separately produced essentially same results (Figure S1 in Supplementary Materials).

Missingness is negatively correlated with the expression level

We categorized four major RNA species by the level of expression using 0.01 increment so the first category included RNAs with the expression levels 0-0.01, second 0.01–0.02, third 0.02–0.03 and so on. As expected, we observed a strong negative association between the missingness rate and expression when analyzing all RNA types together (Fig. 3, top panel). Similar negative relationships were observed in the analyses stratified by RNA types: protein coding, lncRNA, and to a lesser extent processed and unprocessed pseudogenes (Fig. 3 panels 2–5). The results of stratified (adjacent normal and tumor samples analyzed separately) analysis (Figure S2 in Supplementary Materials) are very similar to the results shown on the Fig. 3.

Expression in the genes stratified by number of missing values

We further examined the relationship between missingness and the level of the gene expression by stratifying genes by the number of missing values. Figure 4 shows the results of the analysis. As expected, we found that genes with zero missingness tended to have a higher expression level, and as missingness increases, the mean expression level tends to decrease (left parts of the distribution). Surprisingly, we have observed a clear trend towards a higher expression at the rightmost part of the distributions (genes with highest levels of missingness). The trend is present in all four types of RNAs. In a separate analysis of tumor and adjacent normal tissue samples (Figure S3 in Supplementary Materials) the results were essentially the same as the results shown on Fig. 4.

Modeling of effects of environmental exposures on missingness

We hypothesized that the unexpected spike in expression of the genes with the highest missingness can be explained by the presence of genes whose expression level depends on environmental exposures in heterogeneous population that includes exposed and non-exposed individuals. We considered three types of genes: highly expressed, borderline expressed, and genes that are not expressed or extremely lowly expressed under normal conditions (Fig. 5, panels a, b, and c, respectively). Gene expression values were modeled as random uniformly distributed numbers. To reflect the effect of environmental exposure, expression values of the inducible genes (half of the genes were assumed to be inducible) were further multiplied by a scaling coefficient to scale the average expression level to the detection level (a higher expression level). Likewise, for genes downregulated by exposure, the expression values were scaled down to the detection level. Under normal conditions (no environmental exposure), the only source of missingness is the genes with low, borderline level of expression (panel b). Since there is a natural variation in gene expression levels23, in some samples the expression will be high enough to be detected (those above the detection threshold shown as orange bars) while the genes with the expression level below the detection threshold will not be detected and will contribute to the missingness. In the modeling process we assume that half of the study population undergoes environmental exposure that elevates the gene expression level (middle panels, samples with the exposure are shown in green square). Induction of the gene expression moves genes unexpressed under normal conditions to the category “expressed genes with missing data” (compare panels c and f). The bottom panels depict the situation when exposure suppresses gene expression. In this situation the expression level of genes highly expressed under normal conditions may become too low to be detected, so the overall missingness may increase.

The exact effect of exposure-sensitive genes on missingness depends on how strongly gene expression changes in response to the exposure, which in turn depends on individual variation in exposure sensitivity which can be very high24,25,26. The only source of missingness in exposure-free individuals is the genes with expression close to the detection threshold, since the exposure-sensitive genes are not expressed at all and therefore do not contribute to missingness. On the other hand, in individuals with exposure, both genes with borderline expression and exposure-sensitive genes contribute to missingness, and therefore, one can expect a higher missingness in samples with exposure compared to individuals/samples without exposure. Also compared to genes with the borderline expression level, environment exposure-sensitive genes are likely to have a relatively high expression level (panels f and g) which can explain the observed spike in the gene expression level among genes with missingness.

Modeling of the effect of exposure-sensitive genes on missingness. Each dot represents a sample, the orange horizontal bar shows the detection threshold, and the vertical green bar indicates samples/individuals with environmental exposure. The top 3 panels depict the situation with no environmental exposure, the middle panels show the situation when exposure increases the level of expression, and the bottom panels illustrate the situation when exposure suppresses gene expression. Normal conditions: the only source of missingness is borderline expressed genes (b). Environmental exposure that increases gene expression is present in half of the study population (green square). There are two sources of missingness: borderline expressed genes (e) and the genes that are not expressed under the normal conditions but are expressed in response to an environmental exposure (f). Environmental exposure that decreases gene expression is present in half of the study population (green square). There are two sources of missingness: borderline expressed genes (h) and the genes that are highly expressed under the normal conditions but are suppressed in response to an environmental exposure (g).

Tobacco smoke exposure and missingness

Smoking is an obvious candidate for environmental exposure for lung tissue. It is well known that tobacco smoke exposure leads to global changes in methylation and modulates gene expression in lung epithelium27,28. The analyzed study population includes smokers and nonsmokers (Table 1). Tobacco smoke-inducible genes will be expressed only in smokers and expression level may be high29. There were 45 smokers and 14 never smokers. For 7 individuals smoking status was not available and they were excluded from the analysis.

To test the hypothesis of smoking-related missingness we compared missingness and gene expression in smokers and nonsmokers. For each gene we estimated the percentage of missing values and for each sample estimated mean percentage across all genes. This was done separately for smokers and nonsmokers and sample type: adjacent normal versus tumor tissue. The results of the analysis are shown in the Table 3.

The percentage of missing values is higher in smokers compared to nonsmokers in all RNA species together as well as in RNA type stratified analyses. The simplest explanation of the observation is that smoking increases inter-individual variation in terms of gene expression. Some genes can be up- and other, downregulated in response to tobacco smoke26,30. There is also inter-individual variation in tobacco smoke sensitivity as well as the intensity and duration of the exposure itself. Inter-individual heterogeneity in tobacco smoke exposure contributes to the missingness31,32.

Additionally, we computed log ratios of mean expression in smokers versus nonsmokers and compared log ratios for two approximately equally sized gene categories: genes without missing values and genes with at least one missing value. Mean log ratios were significantly higher in genes with missing data compared to the genes without missing data: -0.061 ± 0.01 versus 0.039 ± 0.03, t-test = 43.9, df = 19,659, p = 1.5 × 10− 42. Figure 6 further illustrates comparative analysis of log ratios in smokers versus nonsmokers.

Analysis of genes with and without missingness in the context of the gene expression level

We stratified all protein coding genes into those without missing data (N = 13,198) and with at least one missing value (N = 6,311) and computed mean expression values for each gene ignoring missing values. Figure 7 shows the Gaussian kernel smoothed distribution for the genes from the two categories by mean expression values. One can see that the distribution for the genes with missing data is shifted to the left – lower expression, while the distribution for the genes without missing data is more spread to the right. The median gene expression value for the genes without missing values was 1.024. Even though mean expression values for genes with missing values clustered around the median (0.07), there are genes with high mean expression in this group. We wanted to look at the genes with high mean expression and missingness. As a threshold for high expression we selected median expression in the genes without missingness. A total of 202 genes, or about 1% of all genes used in the study, were identified as highly expressed with missingness genes (HEWM). The list of the HEWM genes can be found in supplementary table S1.

Distribution of the genes with and without missing data by gene expression level. Blue dotted line indicates the median expression in genes without missing data. Rugs with individual data points as vertical lines are shown at the bottom: dark lines represent genes without missing data and red lines are the genes with at least one missing value.

Highly expressed genes with missingness are the top candidates for the true biological missingness because missingness in those genes cannot be explained by a borderline low level of the gene expression. We wanted to see if HEWM genes were somehow different from other protein coding genes. For this, we first compared smokers and nonsmokers by expression levels. This was done for all protein coding genes used in the study. For each gene we computed.

-

LOG(p) as a measure of gene sensitivity to the smoking exposure. We found that the mean.

-

LOG(p) for HEWM genes was 0.581 ± 0.042 while for non-HEWM genes it was 0.39 ± 0.003: the difference is statistically significant, p = 5.9 × 10− 13. We also checked if HEWM genes are enriched by the genes involved in some specific biological function. We used WebGestalt33 for the gene enrichment analysis. We run 202 HEWM genes against all protein coding genes used in the study. The results of the gene enrichment analysis are shown on the Fig. 8. The most significant gene ontology function was humoral immune response (FDR = 0.004).”

Discussion

As expected, we found that genes with a low level of expression tended to have a higher missingness compared to highly expressed genes (Fig. 3). The unexpected result of this study was that genes with high missingness tend to have higher expression compared to what one can expect based on the negative association between gene expression level and missingness (Fig. 4). We hypothesized that the gene expression spike in high-missingness genes exists because the genes with extreme missingness include not only genes with low expression but also genes whose expression depends on tobacco smoke exposure. Among the latter are genes that are not expressed under normal conditions but become expressed in response to tobacco smoke exposure. A comparative analysis of the missingness in smokers and nonsmokers, the observation that genes with missing data tend to have higher expression in smokers compared to nonsmokers, enrichment of the genes with missing values by known tobacco smoke inducible genes, and the results of the gene enrichment analysis provide strong support for the idea that environmental exposure-inducible genes can contribute to the patterns of missingness in RNAseq-based assessment of gene expression.

Though the majority of missing data in RNAseq analysis of the gene expression result from technical/analytic artefacts and insufficient sensitivity to detect transcripts from low-expressed genes, for some genes missingness can be a real biological phenomenon related to inter-individual variation in gene expression. We have identified 202 genes that are highly expressed but still have missing data. These genes show a stronger difference in the expression levels between smokers and never smokers compared to other genes, which supports the idea that in this case the tobacco smoke exposure may contribute to true biological missingness. We also found that genes which are highly expressed but have missing values identified in our analysis are enriched by the genes contributing to “humoral immune response”. Humoral immune response shows a strong association with smoking in several studies34,35,36. This provides further support to the idea that modulation of gene expression by smoking may contribute to missingness in our sample that includes smokers and never smokers.

The results of our analysis call for changes in how missing gene expression values are treated in RNAseq studies. There is a consensus that excluding genes with a lot of missing values may lead to loss of information and reduce statistical power of downstream analyses37. A number of computational methods were proposed to impute missing gene expression values38,39,40 see Baghfalaki et al. for review41. The results of this study argue for caution when using imputation. There can be a situation when genes with a high missingness rate include two distinct groups: (i) genes with very low expression level and (ii) genes that are not expressed in the majority of individuals but are highly expressed in some individuals in response to environmental exposures or other conditions.

An uncritical application of imputation in such situations will lead to a bias since we will wrongly assign some expression to genes that are not expressed. A more prudent and productive approach will be to examine the rightmost end of the missingness distribution. If there is a spike in expression level of the genes with high missingness, it suggests the presence of environmental exposure- or another condition-inducible genes. Indiscriminatory imputation of missing values for such genes will be misleading. A better approach can be to put efforts towards identification of exposure/condition-inducible genes to understand how such genes are related to the phenotype of interest.

We propose the following steps to identify genes with true biological missingness.

-

1.

Stratify genes into those with and without missing data.

-

2.

Identify the median gene expression in genes without missing data.

-

3.

Identify genes with missing data and the expression level higher than the median in genes without missingness – highly expressed with missingness (HEWM) genes.

-

4.

Explore if HEWM genes differ from other genes in the study: is their expression observed in individuals with an exposure or certain clinical features? A gene enrichment analysis can also be performed.

-

5.

Exclude HEWM genes from imputation of missing data.

Genes with true biological missingness need to be analyzed separately from other genes because the separate analysis of the genes with TBM is likely to provide insight in the study of the phenotype of interest.

Data availability

The datasets used and analyzed in the current study are available from the corresponding author on reasonable request. Gene expression data used in the study were deposited in the GEO database: accession number GSE283245. Data can be downloaded using the following link: https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/geo/query/acc.cgi?acc=GSE283245.

References

Hrdlickova, R., Toloue, M. & Tian, B. RNA-Seq methods for transcriptome analysis. Wiley Interdiscip Rev. RNA 8(1). (2017).

Wang, Z., Gerstein, M. & Snyder, M. RNA-Seq: a revolutionary tool for transcriptomics. Nat. Rev. Genet. 10(1), 57–63 (2009).

Luecken, M. D. & Theis, F. J. Current best practices in single-cell RNA-seq analysis: a tutorial. Mol. Syst. Biol. 15(6), e8746 (2019).

Ou-Yang, L., Cai, D., Zhang, X. F. & Yan, H. WDNE: an integrative graphical model for inferring differential networks from multi-platform gene expression data with missing values. Brief Bioinform. 22(6). (2021).

Soemartojo, S. M. et al. Iterative bicluster-based bayesian principal component analysis and least squares for missing-value imputation in microarray and RNA-sequencing data. Math. Biosci. Eng. 19(9), 8741–8759 (2022).

Huang, M., Ye, X., Li, H. & Sakurai, T. Missing value imputation with low-rank matrix completion in single-cell RNA-Seq data by considering cell heterogeneity. Front. Genet. 13, 952649 (2022).

Deyneko, I. V. et al. Modeling and cleaning RNA-seq data significantly improve detection of differentially expressed genes. BMC Bioinform. 23(1), 488 (2022).

Conesa, A. et al. A survey of best practices for RNA-seq data analysis. Genome Biol. 17, 13 (2016).

Khang, T. F. & Lau, C. Y. Getting the most out of RNA-seq data analysis. PeerJ 3, e1360 (2015).

Rapaport, F. et al. Comprehensive evaluation of differential gene expression analysis methods for RNA-seq data. Genome Biol. 14(9), R95 (2013).

Sarker, B., Matiur Rahaman, M., Alamin, M. H., Ariful Islam, M. & Nurul Haque Mollah, M. Boosting edger (Robust) by dealing with missing observations and gene-specific outliers in RNA-Seq profiles and its application to explore biomarker genes for diagnosis and therapies of ovarian cancer. Genomics 116(3), 110834 (2024).

Song, M. et al. A review of integrative imputation for multi-omics datasets. Front. Genet. 11, 570255 (2020).

Kukurba, K. R. & Montgomery, S. B. RNA sequencing and analysis. Cold Spring Harb Protoc. 2015(11), 951–969 (2015).

Dobin, A. & Gingeras, T. R. Mapping RNA-seq reads with STAR. Curr. Protoc. Bioinform. 51, 11–14 (2015).

Luleci, H. B. et al. A benchmark of RNA-seq data normalization methods for transcriptome mapping on human genome-scale metabolic networks. NPJ Syst. Biol. Appl. 10(1), 124 (2024).

Evans, C., Hardin, J. & Stoebel, D. M. Selecting between-sample RNA-Seq normalization methods from the perspective of their assumptions. Brief. Bioinform. 19(5), 776–792 (2018).

Koch, C. M. et al. A beginner’s guide to analysis of RNA sequencing data. Am. J. Respir Cell. Mol. Biol. 59(2), 145–157 (2018).

Dubey, A. & Rasool, A. Efficient technique of microarray missing data imputation using clustering and weighted nearest neighbour. Sci. Rep. 11(1), 24297 (2021).

Newman, A. M. et al. Determining cell type abundance and expression from bulk tissues with digital cytometry. Nat. Biotechnol. 37(7), 773–782 (2019).

Dobin, A. et al. STAR: ultrafast universal RNA-seq aligner. Bioinformatics 29(1), 15–21 (2013).

Li, B. & Dewey, C. N. RSEM: accurate transcript quantification from RNA-Seq data with or without a reference genome. BMC Bioinform. 12, 323 (2011).

Fabian Pedregosa, G. V. et al. Scikit-learn: machine learning in python. J. Mach. Learn. Res. 12(85), 2825–2830 (2011).

Kedlian, V. R., Donertas, H. M. & Thornton, J. M. The widespread increase in inter-individual variability of gene expression in the human brain with age. Aging. 11(8), 2253–2280 (2019).

Hernandez, A. & Marcos, R. Genetic variations associated with interindividual sensitivity in the response to arsenic exposure. Pharmacogenomics 9(8), 1113–1132 (2008).

Maunders, H., Patwardhan, S., Phillips, J., Clack, A. & Richter, A. Human bronchial epithelial cell transcriptome: gene expression changes following acute exposure to whole cigarette smoke in vitro. Am. J. Physiol. Lung Cell. Mol. Physiol. 292(5), L1248–1256 (2007).

van der Does, A. M. et al. Early transcriptional responses of bronchial epithelial cells to whole cigarette smoke mirror those of in-vivo exposed human bronchial mucosa. Respir Res. 23(1), 227 (2022).

Li, J. L. et al. The association of cigarette smoking with DNA methylation and gene expression in human tissue samples. Am. J. Hum. Genet. 111(4), 636–653 (2024).

Zong, D., Liu, X., Li, J., Ouyang, R. & Chen, P. The role of cigarette smoke-induced epigenetic alterations in inflammation. Epigenetics Chromatin. 12(1), 65 (2019).

Beane, J. et al. Reversible and permanent effects of tobacco smoke exposure on airway epithelial gene expression. Genome Biol. 8(9), R201 (2007).

Billatos, E. et al. Impact of acute exposure to cigarette smoke on airway gene expression. Physiol. Genomics. 50(9), 705–713 (2018).

Creighton, C. J. Gene expression profiles in cancers and their therapeutic implications. Cancer J. 29(1), 9–14 (2023).

Gonzalez, A., Leon, D. A., Perera, Y. & Perez, R. On the gene expression landscape of cancer. PLoS One. 18(2), e0277786 (2023).

Elizarraras, J. M. et al. WebGestalt 2024: faster gene set analysis and new support for metabolomics and multi-omics. Nucleic Acids Res. 52(W1), W415–W421 (2024).

Valeriani, F. et al. Does tobacco smoking affect Vaccine-Induced immune response?? A systematic review and Meta-Analysis. Vaccines (Basel) 12(11). (2024).

Ferrara, P., Gianfredi, V., Tomaselli, V. & Polosa, R. The effect of smoking on humoral response to COVID-19 vaccines: A systematic review of epidemiological studies. Vaccines (Basel) 10(2). (2022).

Choi, W. S. et al. Smoking and serological response to influenza vaccine. Hum. Vaccin Immunother. 20(1), 2404752 (2024).

Linderman, G. C. et al. Zero-preserving imputation of single-cell RNA-seq data. Nat. Commun. 13(1), 192 (2022).

Faisal, S. & Tutz, G. Missing value imputation for gene expression data by tailored nearest neighbors. Stat. Appl. Genet. Mol. Biol. 16(2), 95–106 (2017).

Qiu, Y. L., Zheng, H. & Gevaert, O. Genomic data imputation with variational auto-encoders. Gigascience 9(8). (2020).

Shahjaman, M. et al. rMisbeta: A robust missing value imputation approach in transcriptomics and metabolomics data. Comput. Biol. Med. 138, 104911 (2021).

Baghfalaki, T., Ganjali, M. & Berridge, D. Missing value imputation for RNA-Sequencing data using statistical models: A comparative study. J. Stat. Theory Appl. 15(3), 221–236 (2016).

Funding

This study was supported by Cancer Prevention Research Institute of Texas (CPRIT) RR170048 and RP200443 awards, National Institutes of Health (NIH) awards U19CA203654, R01CA285882, R03CA282953, R37 (R01) CA289419-01, U24 2U24OH009077-15-00, R01CA275762, R01CA243483, R21AI159379, R37 CA248478, a US Department of Defense Impact Award W81XWH-22-1-0657, French National Research Agency award ANR-23-IAHU-007, and the Helis Medical Research Foundation. The Human Tissue Acquisition and Pathology core supports tissue collection with funding from P30 Cancer Center Support Grant (NCI-CA125123).

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

O.Y.G, I.P.G., and C.I.A. designed the original study, O.Y.G, I.P.G., R.T.R., C.C., Y.L., B.P., Y.L., H.S.L., and C.I.A. provided acquisition and interpretation of the data, R.T.R, H.J.J, S.W.K, C.L, P.R, B.M.B., H.S.L., and C.I.A. obtained clinical samples, H.J.J, S.W.K, C.L, P.R, and H.S.L. performed RNA extraction and quality control, O.Y.G, and I.P.G. wrote the original draft, O.Y.G, I.P.G., R.T.R., Y.L., Y.L., H.S.L. and C.I.A. reviewed and edited the manuscript, all authors approved the final submitted manuscript.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Ethics approval and consent to participate

This study was approved by Institutional Review Board protocol at Baylor College of Medicine (H-35782) and performed in accordance with Institutional Review Board protocol at Baylor College of Medicine (H-35782). Informed consent was obtained from all study participants for the collection of clinical data and biospecimens.

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher’s note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Supplementary Information

Below is the link to the electronic supplementary material.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if you modified the licensed material. You do not have permission under this licence to share adapted material derived from this article or parts of it. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Gorlova, O.Y., Gorlov, I.P., Ripley, R.T. et al. Exposure-inducible genes may contribute to missingness in RNAseq-based gene expression analyses. Sci Rep 15, 30889 (2025). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-14395-0

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-14395-0