Abstract

This study examines the association of aortic geometric traits with flow characteristics and disease outcomes in 3204 patients from the Penn Medicine Biobank (PMBB). Using an nnU-Net, the thoracic aorta was segmented from CT scans to measure traits such as diameter and length. A one-dimensional reduced-order Navier–Stokes model (ROM) simulated aortic pulse pressure under various physiological conditions. Phenome-wide association studies (PheWAS) were conducted to link aortic traits to diseases using electronic health records (EHR). Significant associations were identified between aortic pulse pressure and conditions like aortic aneurysms, heart valve disorders, hypertension, and obesity. Notably, pulse pressure—but not aortic diameter—was also linked to diseases such as diabetes mellitus, wheezing, and chronic airway obstruction. The ROM-simulated pulse pressure showed not only previously recognized associations with diseases such as aortic aneurysm and hypertension, but also associations with conditions affecting organs outside the aorta. ROM hemodynamic simulations can be applied to thoracic images at the scale of thousands of patients. The ROM-simulated pulse pressure showed not only previously recognized associations with diseases including aortic aneurysm and hypertension, but also other diseases outside the aorta.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Aortic hemodynamics, defined by blood flow characteristics such as velocity, wall shear stress, and pressure gradients, drive progression of aortic diseases, including aneurysms, dissections, and atherosclerosis1,2,3. Altered hemodynamics leads to abnormal aortic wall mechanical stress, contributing to structural weakness and disease progression1. In addition to aortic disease, aortic hemodynamics are increasingly implicated in diseases of other vascular regions and organs. For instance, disrupted aortic flow has been linked to cerebrovascular diseases, chronic kidney disease (CKD), and systemic inflammatory conditions, suggesting a broader impact of aortic hemodynamics on overall cardiovascular health and disease4,5,6. Identifying these links can reveal underlying mechanisms that span multiple organ systems. Such insights could lead to more holistic treatment strategies and early interventions.

While studies have highlighted associations between altered flow patterns and multiorgan disease, many rely on selective cohorts with limited sample size and do not contain detailed multiorgan disease data5,7,8. The increasing availability of detailed electronic health record data and medical biobanks can enable the discovery of hemodynamically associated multiorgan traits at scale. To address this limitation and uncover hidden links with other pathologies, approaches such as Phenome-Wide Association Studies (PheWAS) can be used, which scan broadly across health phenotypes in a bias-free manner9. This method enables the systematic evaluation of the influence of aortic hemodynamics on a wide spectrum of diseases, potentially illuminating novel risk factors and therapeutic targets. PheWAS can be used to identify novel associations between different risk factors and pathologies, most commonly utilizing genetic data. The bias-free technique was originally developed to determine associations between the phenotype and single nucleotide polymorphisms by assigning different phenotypes values, hereby called phecodes9. The PheWAS tool has been previously applied in the UK Biobank in order to determine associations between COVID-19 outcomes and relevant comorbidities10.

Past epidemiologic studies have primarily focused on the association between geometric traits of the aorta and disease but have not comprehensively described the hemodynamic changes in aortic diseases using 3D computational fluid dynamics (CFD). The application of CFD to large-scale studies has been limited due to its significant computation and time costs, making it sub-optimal for epidemiologic studies of thousands of patients11,12. Alternative approaches such as reduced-order models (ROMs) have been developed to overcome challenges with 3D CFD simulations which approximate the full CFD solution by projecting the governing equations onto a lower-dimensional subspace13. This approach trades some accuracy for the efficiency of simulating a less complex hemodynamic problem. ROMs for pulse wave propagation typically use either zero- or one-dimensional simulations, applying a set of simplifying assumptions to reduce the complex 3D geometry of the vessel to a zero- or one-dimensional spatial domain14,15,16,17. Zero-dimensional simulations (also called lumped parameter models) reduce the vascular simulation to the mathematical equivalent of solving a simple electrical circuit problem and do not have an explicit spatial dependence14,15. Alternatively, a one-dimensional ROM applies a set of assumptions that the pressure and flow parameters are obtained over the cross-sectional area of the vessel, reducing the complexity of the problem from 3D to a 1D spatial dependence16,17,18. When evaluated on a public set of 72 cardiovascular models, both zero- and one-dimensional ROMs were comparable to 3D CFD simulations, showing only a small tradeoff in accuracy with a modest improvement in efficiency19. The accuracy of these models have also been examined closely in tubes and branched arterial models and have been validated both in-vitro and in-vivo20,21,22.

In this work, one-dimensional ROMs were used to perform hemodynamic simulations of the thoracic aorta from computed tomography (CT) scans obtained in thousands of patient participants of the Penn Medicine Biobank (PMBB), which is an Institutional Review Board (IRB)-approved research protocol in which consenting patients provide electronic health record and non-invasive imaging data to be made available for research14. A convolutional neural network (nnU-Net) was used to obtain thoracic aorta anatomy for the CT scans23,24. ROM simulations were performed over a wide range of non–patient-specific conditions by systematically varying boundary conditions, volumetric flow rates, and vascular resistance to explore physiologically relevant scenarios. For each simulation, the pulse pressure was determined, which was defined as the difference between aortic systolic and diastolic pressure25. The PMBB patient electronic health record (EHR) data includes detailed information about the patients and the presence of disease in this population. Past work has been done in which a PheWAS has been conducted to associate diseases with image-derived geometric traits of the aorta26,27,28. However, with pulse pressures simulated using ROMs that incorporated image-derived geometric traits as key input parameters, we were able to discover connections between aortic pulse pressure and diseases in other organ systems that were not previously known.

Objective

The goal of this paper is to apply a PheWAS to hemodynamic values calculated from a ROM utilizing patient data from the PMBB on a large scale. We hypothesized that the ROM-simulated pulse pressures were associated with electronic health record (EHR)-documented diseases in this same cohort. An overview of the experimental design appears in Fig. 1.

Overview of the study design. Thoracic segmentations of the aorta were performed on > 3,000 CT scans using a nnU-Net. Meshes (visualized as “Ao Model”) were constructed from the segmentations using The Vascular Modeling Toolkit (VMTK) 1.4.0 (http://www.vmtk.org/). After segmentation and meshing, aortic anatomic parameters were calculated including the cross-sectional area of the vessel A(x) and the length L of the centerline from the aortic valve to the inferior thoracic vertebrae. Simulations were performed using A(x) and L as an input to the ROM, while resistance and flow conditions were permitted to vary over a physiologic range defined by the literature. Hemodynamic and anatomic traits were associated with diseases codes in the Penn Medicine Biobank (PMBB) obtained from the electronic health record (EHR), adjusting for the age and sex of the patient.

In summary, the main contributions of this paper are thus:

-

1.

We obtained 3D aortic geometries from more than 3,000 patients in a large-scale cohort of patients from the Penn Medicine Biobank using a convolutional neural network segmentation algorithm. In each patient, the 3D aortic geometry is reduced to a one-dimensional geometric model and aortic hemodynamics are simulated from the one-dimensional ROM. We showed that the ROM can efficiently obtain hemodynamic parameters from thousands of patients and over a wide range of physiological and pathological conditions, even when the aortic pressure is not known. We were then able to associate these simulated hemodynamic traits with cardiovascular diseases through a PheWAS.

-

2.

The pulse pressure obtained using ROM simulations was found to be associated not only with aortic disease, but also with a spectrum of diseases throughout the body.

Methods

Penn Medicine Biobank (PMBB)

Medical biobanks are repositories of multimodal patient data collected by hospitals and affiliated research institutions29. PMBB is an institutional initiative medical biobank under which any registered patient of Penn Medicine aged 18 or older is eligible, with no exclusions except an inability to provide informed consent. The PMBB recruits patients in the Penn Medicine Health System (Philadelphia, PA) by enrolling them at the time of outpatient visits. Patients complete a questionnaire, donate a blood sample, and agree to future recontact. It is an ethnically diverse cohort with Black patients comprising nearly 25% of participants. Though the PMBB has recruited over 264,000 patients as of May 31, 2024, this study investigated a cohort of more than 3,000 patients with thoracic CT scans. This study was approved by the Institutional Review Board of the University of Pennsylvania and all patients have given informed consent to participate. All methods were performed in accordance with the relevant guidelines and regulations.

Scan acquisition and segmentation

Thoracic CT scans were performed on PMBB patients as part of routine clinical care using a range of different imaging systems and manufacturers (Siemens, Erlangen, Germany; GE Healthcare, Chicago, IL Systems) and with varying acquisition parameters (e.g. slice thickness = 0.5–1.5 mm). Images were segmented using the TotalSegmentator model to obtain 3D aortic geometries and vertebral bodies24. It uses nnU-Net, a self-configuring deep learning framework used for biomedical image segmentation that packages pre-processing, network architecture selection, training and post processing. nnU-Net uses the U-Net architecture which features a symmetric encode-decoder structure with skip connections. The TotalSegmentator model is publicly available and comes pre-trained using expert-obtained labels from more than 1200 patients. It is robust and has demonstrated high accuracy with a Dice score of 0.943 on a diverse test set of 65 patients with varying pathologies23. A recent study reported a Dice similarity coefficient of 0.934 between thoracic aortas in PMBB chest CT scans in TotalSegmentator’s segmentations and segmentations drawn by two trained medical doctors30. Using this model, the ascending and descending thoracic aorta were labeled. The proximal ascending aorta was labeled at the aortic valve. The distal descending aorta was labeled at the middle axial plane of the T12 thoracic vertebra (T12). The model took approximately 100 h on an Intel® Core™ i5-8500 CPU at 3.00 GHz with 8 GB of RAM to segment the whole cohort in this study.

Aortic model generation

Models were generated from the thoracic aortic segmentations in open-source software (VMTK 1.4.0)31. VMTK was then used to generate the centerline for each model, which was used to calculate the length, diameter, curvature, and torsion. VMTK calculates the centerline of the vessel by determining the shortest path between two external points. The program ensures that the center point lies in the vessel by consulting a Voronoi diagram. If the point runs along the Voronoi diagram for the vessel, it is valid. The aortic diameter D(x) was resampled using a nearest neighbor interpolator (Python 3.11). The tapering angle of the thoracic aorta was defined as

where Dmax, min are the maximum and minimum diameters of the aorta and L is its length32.

Reduced Order Model (ROM) of the Aorta

The ROM is based on a 3-element Windkessel model, in conjunction with the fluid–structure interactions that occur from the distensibility of the aortic vessel wall. The blood flow through the aorta can be modeled using a 1D system defined by three equations: mass conservation, momentum conservation and a relationship between pressure, area and distensibility of the vessel18,33. These can be seen in Eqs. (2), (3) and (4), respectively,

In these equations, A(x,t) is the cross-sectional area of the vessel, Q is the volumetric flow rate, α is a momentum flux correction factor set to 1.1 for parabolic flow, u is the flow velocity, ρ is the density of the fluid and f represents the force of friction. The friction term f accounts for viscous dissipation and is defined as:

with \(\mu\) being the dynamic viscosity of blood.

In Eq. (4) which describes the relationship between pressure and area, p is the pressure inside the vessel, pext is the external pressure and Ao is the area of the vessel at equilibrium. This relationship assumes that the vessel wall behaves as an elastic tube, where the nonlinear relationship between pressure and cross-sectional area is derived from Laplace’s law and elasticity theory. This square-root dependency ensures physiologically consistent vessel expansion under pressure and has been used widely in prior literature to describe hemodynamics33,34. β is a term that is a property of the vessel and is calculated from Eq. 6.

This β term is described by k1, k2, and k3, which are constants that experimentally fit for calculating the ratio between the Young’s modulus and the dimensions of the vessel. The definition of β(x) in Eq. (6) follows the formulation introduced by Olufsen et al. in their study of pressure-wave propagation in large arteries, where the exponential dependence reflects empirically derived relationships between vessel stiffness and geometry21. In the same study, the constants k1 = 2.00 × 107 g s−2 cm−1, k2 = 22.53 cm−1, k3 = 8.65 × 105 g s−2 cm−1 were obtained by fitting experimental data21. These values were used in the simulations for our study as well. \(v\) is the Poisson ratio which was set to 0.5 in this study. A Poisson ratio of 0.5 represents perfect incompressibility; however, arterial walls are often modeled this way due to their nearly incompressible behavior. This simplifying assumption has been employed in prior vascular modeling studies as well33. Altogether, this system of equations describes the pulse wave propagation down the vessel.

To obtain a physiologically accurate outflow waveform, the input flow waveform is passed through a 3-element Windkessel model (as outlined in Eq. 7), which is applied at the outlet boundary of the 1D domain35.

R is the peripheral resistance of the vessels, C is the vessel compliance and Z is the characteristic impedance of the vessel, which was calculated as from a Tau ratio, which is the ratio of the peripheral resistance to the characteristic impedance (τ = R/Z), the Tau ratio was calculated from a previous study36. The 3-element Windkessel model describes the relationship between pressure and flow at the outlets of the aorta. It provides the boundary conditions at the outlets and is thus coupled with the 1D system to ensure that the flow exiting the aorta matches the flow entering the peripheral circulation. The coupled system is then solved numerically to simulate the blood flow and pressure wave propagation at the outlet17,33.

Boundary conditions

Since physiologic data was not known at the time of the CT scans, a range of physiologic boundary conditions were used, including the peripheral resistance, vessel compliance and the inlet volumetric flow rate. At the inlet of the 1D model was a time-varying volumetric flow defined a half sine wave (Eq. 8):

where \(Q\left( t \right)\) is the volumetric flow at time \(t\), \(Q_{peak}\) is the peak amplitude,\(T_{sys} = \frac{2}{5}T\) is the systolic duration and \(T\) is the cardiac cycle period. The peak amplitude \(Q_{peak}\) was set to 200 cm3/s during systole and 0 cm3/s during diastole. This was varied by increasing and decreasing the peak flow rate by 10%, leading to a range of 180 cm3/s to 220 cm3/s.

At the outlet of the 1D model, a three-element Windkessel model was applied which imposes a pressure boundary condition, allowing for realistic pressure-flow dynamics. The physiologic range of aortic peripheral resistance and vessel compliance have been previously reported and were used as a basis for the applied boundary conditions17,36,37. The peripheral resistances were varied between 710 dynes*s/cm5 to 2900 dynes*s/cm5. The compliance was fixed at 0.8 µm/mmHg. Pressure and flow were measured at the level of the T12 thoracic vertebrae.

By considering these non-informative priors over the ROM while the geometry is fixed for each patient, we do not introduce any bias in the correlations between the geometry and the conditions. Thus, the simulations are not confounded by the boundary conditions used and we solely consider the contribution of the patient’s geometry in our analysis. An overview of how the 1D ROM is coupled with the boundary conditions is visualized in Fig. 2.

Schematic overview of 1D model coupled with 3-element Windkessel model. The central schematic illustrates a one-dimensional (1D) model of the thoracic aorta, governed by the equations of mass conservation, momentum conservation, and a pressure-area relationship. Patient-specific vessel diameter (D) and length (L) define the cross-sectional area and spatial domain, influencing wave speed, impedance, and tapering effects. The inlet boundary condition (left) is defined by a pulsatile velocity waveform representative of cardiac output. At the outlet, a three-element Windkessel model (right) is used to capture downstream vascular resistance and compliance, incorporating characteristic impedance (Zc), peripheral resistance (Rp), and compliance (C). This framework allows for physiologically relevant simulation of pressure and flow wave propagation along the vessel.

Phenome-wide association study (PheWAS)

A phenome-wide association study (PheWAS) was performed in 3,204 patients for whom EHR data was available to examine the association between deep learning and CT-derived aortic diameter and ROM-simulated pulse pressure and diseases reported in the EHR using an open-source statistic package (RStudio 2023.09.01). EHR-reported diseases (International Classification of Diseases 9 and 10) were mapped to phecodes9. PheWAS was performed only for phecodes with an incidence greater than 100. Maximum aortic diameter was tested independently using logistic regression adjusted for age, sex and aortic length. ROM-simulated pulse pressure was similarly tested and adjusted for age, sex and maximum aortic diameter. Statistical significance was adjusted for multiple comparisons using Bonferroni correction.

Results

Patient demographics

The investigators identified 3,216 thoracic CT scans from the Penn Medicine Biobank (PMBB). After aortic segmentation and ROM analysis, 12 thoracic CTs were unable to be processed, resulting in a final data set of 3,204 thoracic CTs with imaging traits. Demographic information at the time of the CT scan is in Table 1. Most patients were 40–59 years old (27.5%) or 60–79 years old (52.7%). There was an equal proportion of men and women in the study (50.4% male). The ten most common diseases reported in this cohort were hypertension, disorders of lipid metabolism, hyperlipidemia, other symptoms of the respiratory system, diseases of the esophagus, cardiac dysrhythmias, esophagitis, gastroesophageal reflux disease (GERD), disorders of fluid balance, and pain in joints.

Thoracic aorta anatomic imaging traits and their association with disease

Figure 3 shows the aortic diameter from the aortic valve to the T12 vertebra among participants by age. The maximum thoracic aortic diameter and length were 33.4 ± 4.2 mm and 310 ± 37 mm, respectively, and distributions are shown in Supplementary Fig. S1A and S1B. There was an increase in aortic diameter with age from 28.5 ± 3.9 mm (20–39 years old) to 35.8 ± 4.7 (> 79 years old). The mean tapering angle for this data set was 1.03 ± 0.31̊.

Associations between maximum aortic diameter and EHR-reported diseases are shown in Fig. 4. The maximum diameter for each significant disease can be found in Table 2. As expected, the strongest disease association with maximum aortic diameter was aortic aneurysm (Dmax = 37.7 ± 5.8 mm). Other diseases that showed a significant association with maximum aortic diameter were obesity (Dmax = 33.7 ± 4.0 mm) and ventral hernia (Dmax = 34.5 ± 4.0 mm).

Association between maximum aortic diameter and diseases reported in the EHR (n = 3204) adjusted for aortic length, age and patient sex. The strongest disease associations with maximum aortic diameter were aneurysms, heart valve disorders, hypertension, obesity and overweight, sensorineural hearing loss, disorders of refraction and accommodation, blindness and low vision, and cardiac and circulatory congenital anomalies. The blue dashed horizontal line is the Bonferroni-corrected line of statistical significance. Solid, upward triangles indicate positive associations and empty, downward triangles indicate negative associations. The formula utilized for the PheWAS was pheCode ~ Length + Age + Sex + maxDiameter.

ROM-derived pulse pressure and its association with disease

ROM simulations were performed with 8 different resistances and 5 different inflow waveforms chosen equidistantly across the ranges of boundary conditions mentioned previously, resulting in over 125,000 simulations across 3,204 aortas. Figure 5A shows the time-varying aortic pressure for one cardiac cycle as resistance was varied from 920, 1490, 2050 and 2620 dynes-s/cm5. The peak systolic pressure at the T12 vertebra was 201 mmHg at the highest resistance of 2,620 dynes-s/cm5, and the minimum diastolic pressure at the T12 vertebra was 63.6 mmHg at the lowest resistance of 920 dynes-s/cm5. Figure 5B shows variation in the pulse pressure at T12 across the range of resistance and input flow boundary conditions.

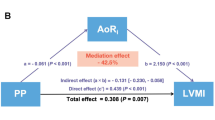

Associations between diseases and ROM-simulated pulse pressure and adjusted by age, sex and maximum aortic diameter, are shown in Fig. 6. For each patient, the average pulse pressure simulated across all boundary condition scenarios was used in the PheWAS analysis. The most significant disease associations with pulse pressure were aortic aneurysm, other aneurysm, nonrheumatic aortic valve disorders, heart valve replacement, heart valve disorders, heart valve disorders, cardiac congenital anomalies, cardiac and circulatory anomalies, other disorders of arteries and arterioles, diabetes mellitus, rheumatic disease of the heart valves, wheezing, chronic airway obstruction, diverticulosis and diverticulitis, atrial fibrillation and flutter, disorders of refraction and accommodation (p < 0.001). The diseases that were significantly associated with pulse pressure are summarized in Table 3. Several diseases were found to be significantly associated with pulse pressure, but not with aortic diameter, including diabetes mellitus, wheezing, chronic airway obstruction, diverticulosis/diverticulitis, atrial fibrillation/flutter and disorders of refraction and accommodation. There was no significant association between tapering angle and pulse pressure (r = 0.02, p = 0.22).

PheWAS for pulse pressure calculated from ROM, showing the most significant phecodes (n = 3204). The blue dashed horizontal line is the Bonferroni-corrected line of statistical significance. Solid, upward triangles indicate positive associations and empty, downward triangles indicate negative associations.

Discussion

This work used one-dimensional ROM simulations to calculate aortic pulse pressure from more than 3,000 patients in a large-scale medical biobank. Aorta segmentations were automatically obtained using deep learning and provided anatomies for simulation. Since aortic pressure and flow were not measured in these patients at the time of their imaging scan, many 1D simulations were performed to determine aortic pulse pressure spanning a range of physiologic boundary conditions. One-dimensional ROMs enabled simulations in this large cohort of patients with a low computational cost compared to three-dimensional simulations, which would have been prohibitively expensive. The ROM-simulated pulse pressures were associated with EHR-documented diseases. This analysis revealed relationships with diseases typically associated with pathologic hemodynamics such as aortic aneurysm and hypertension. However, it also revealed other diseases such as obesity that are not typically examined in CFD studies.

This study has taken a different approach to simulation of aortic hemodynamics from that of previous studies. One approach in aortic CFD modeling is to select healthy subjects or patients with aortic disease such as aortic aneurysm or coarctation and then simulate the aortic hemodynamics using anatomy and flow information obtained from a non-invasive imaging scan such as phase contrast (PC) magnetic resonance imaging (MRI)26,38,39,40,41. Alternatively, invasive or non-invasive aortic blood pressure measurements can be obtained using catheters or arterial tonometry and together combined with non-invasive imaging studies42,43. In this medical biobank research study, simulations were performed in all patients that had thoracic CT scans without first selecting them based on the presence of aortic disease. This agnostic approach has been used recently in other large-scale PheWAS of gene-disease and imaging-trait-disease associations, but it has not been yet applied to CFD simulations44,45. This approach is hypothesis-generating in that it can reveal important, previously unknown associations between aortic hemodynamics and disease. It is an important first step in identifying unknown processes that may be connected to the trait or in defining traits that may have underlying genetic or environmental contributions.

The computational efficiency of one-dimensional ROMs compared to three-dimensional CFD simulations enabled many simulations using CT-derived aortic anatomy. CT is a recommended three-dimensional non-invasive imaging procedure for corrective procedures of the aorta and is more commonly used than thoracic MRI due to the former’s more widespread availability and faster scan times46,47. Moreover, CT opportunistic screening of the thoracic aorta is important for prognosis and risk stratification48. However, unlike PC-MRI or Doppler ultrasound, CT does not encode flow information and alternative approaches to obtain hemodynamic information must be sought. While other previous studies have developed patient-specific ROMs, these studies have not been applied in a large-scale cohort43,49. This study is the first to show ROM-derived pulse pressure-disease associations in a large-scale population.

The PheWAS showed associations between maximum aortic diameter or pulse pressure and diseases recorded in the patients’ EHRs. Significant associations were observed between aortic diameter and EHR-reported conditions, including aneurysms, heart valve disorders, hypertension, obesity and overweight, and congenital anomalies of the cardiac and circulatory system. Regarding aortic diameter and EHR-reported aneurysm, normative reference values for CT-derived mean ascending aorta diameter are 29.0–37.2 mm for women and 30.8–39.1 for men50. While a maximum aortic diameter > 40 mm is considered pathologic, the lack of comprehensive population nomograms with different imaging modalities make it difficult to determine precise reference ranges by age, sex and other traits51. Importantly, this medical biobank study found strong associations between aortic diameter and EHR-reported aneurysm adjusted for age, sex and length of the aorta. As a medical biobank from a large urban US-based health center, the PMBB population consists of an ethnically diverse (30% non-European ancestry) group of patients52. These patients undergo CT as part of their clinical care, hence aortic diameter and pulse pressure were anticipated and found to be greater than healthy subjects overall.

Limitations of this study should be considered. In this study, we assumed a constant tapering angle to describe the axial change in aortic diameter, consistent with prior reduced-order models of arterial flow. This linear tapering assumption provides a physiologically reasonable approximation while maintaining numerical stability and tractability, particularly in large-scale simulations. Previous work demonstrated that linear tapering captures key features of wave propagation and reflection, and that more complex, higher-order geometric representations do not significantly alter global hemodynamic predictions21. While this approach does not account for local geometric variations or asymmetric tapering, especially relevant in patients with aortic pathologies, fitting nonlinear or patient-specific tapering profiles would require high-resolution data and per-patient optimization, which is computationally infeasible at the cohort scale. As such, our modeling choice reflects a deliberate trade-off between anatomical precision and computational scalability, enabling the efficient simulation of thousands of patient-specific geometries.

Pressure and flow measurements were not known in this cohort at the time of the CT scan due to the logistical challenges of obtaining this information during a non-invasive imaging procedure performed in routine clinical care. We addressed this limitation by simulating pulse pressure across a range of physiologic and pathophysiologic resistances and inflows. The strong associations between ROM-simulated aortic pulse pressure and aortic diseases supports that hemodynamic measurements made through purely non-invasive imaging have clinical relevance. Our modeling framework relies on simplifying assumptions for boundary conditions, including a fixed compliance value of 0.8 µm/mmHg and a half-sine inflow waveform. While these assumptions facilitate scalability and standardization across a large cohort, they do not fully capture patient-specific variations in vascular compliance or the triphasic nature of physiological aortic inflow. These simplifications may influence absolute pressure predictions by affecting pulse wave propagation and reflection. However, because the same boundary conditions were applied uniformly across all patients, relative comparisons and population-level associations remain interpretable. Future work incorporating patient-specific inflow profiles and vascular properties may enhance physiological fidelity and predictive accuracy.

Additionally, since we did not have access to ground truth pressure readings, we were unable to validate our results. However, as previously mentioned, the phenotypes most significantly associated with our ROM-derived pressures were aorta-related. As the PheWAS was conducted independently without the injection of any priors, this garners confidence in our results.

Conclusion

This work provided a methodology for gathering ROM hemodynamic information at a large scale and provided a basis for analyzing these results together with clinical information. This was done by first taking CT scan data from the PMBB, converting it to geometries that can be utilized by a ROM, and then simulating through a range of parameters. In the future work can be done to examine different outputs of the ROM, such as reflected waveforms and perform analysis on the clinical significance of them in the PMBB.

Data availability

Clinical data from a biobank was used for this study and thus, it is not possible to make the data available publicly. However, deidentified data could be shared with a qualified researcher upon request, pursuant to the rules and regulations of the biobank and the existing IRB. Please contact Walter Witschey to request data from the study.

References

Suh, G.-Y. et al. Hemodynamic changes quantified in abdominal aortic aneurysms with increasing exercise intensity using MR exercise imaging and image-based computational fluid dynamics. Ann. Biomed. Eng. 39, 2186–2202. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10439-011-0313-6 (2011).

Williams, J. G. et al. Aortic dissection is determined by specific shape and hemodynamic interactions. Ann. Biomed. Eng. 50, 1771–1786. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10439-022-02979-0 (2022).

Stehbens, W. E. The role of hemodynamics in the pathogenesis of atherosclerosis. Prog. Cardiovasc. Dis. 18, 89–103. https://doi.org/10.1016/0033-0620(75)90009-2 (1975).

Kosaki, K. et al. Cerebral and renal hemodynamics: similarities, differences, and associations with chronic kidney disease and aortic hemodynamics. Hypertens. Res. 45, 1363–1372. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41440-022-00944-x (2022).

Verbrugge, F. H., Guazzi, M., Testani, J. M. & Borlaug, B. A. Altered hemodynamics and end-organ damage in heart failure. Circulation 142, 998–1012. https://doi.org/10.1161/circulationaha.119.045409 (2020).

Weir, M. R. et al. Hemodynamic correlates of proteinuria in chronic kidney disease. Clin. J. Am. Soc. Nephrol. 6, 2403–2410. https://doi.org/10.2215/cjn.01670211 (2011).

Bradley, C. R. et al. Multi-organ assessment of compensated cirrhosis patients using quantitative magnetic resonance imaging. J. Hepatol. 69, 1015–1024. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jhep.2018.05.037 (2018).

London, G. et al. Arterial aging and arterial disease: interplay between central hemodynamics, cardiac work, and organ flow—implications for CKD and cardiovascular disease. Kidney Int. Suppl. 1, 10–12. https://doi.org/10.1038/kisup.2011.5 (2011).

Bastarache, L. Using Phecodes for research with the electronic health record: from PheWAS to PheRS. Annu. Rev. Biomed. Data Sci. 4, 1–19. https://doi.org/10.1146/annurev-biodatasci-122320-112352 (2021).

Regan, J. A. et al. Phenome-wide association study of severe COVID-19 genetic risk variants. J. Am. Heart Assoc. 11, 856. https://doi.org/10.1161/jaha.121.024004 (2022).

Yevtushenko, P. et al. Deep learning based centerline-aggregated aortic hemodynamics: an efficient alternative to numerical modeling of hemodynamics. IEEE J. Biomed. Health Inform. 26, 1815–1825. https://doi.org/10.1109/jbhi.2021.3116764 (2022).

Liang, L., Mao, W. B. & Sun, W. A feasibility study of deep learning for predicting hemodynamics of human thoracic aorta. J. Biomech. 99, 562. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jbiomech.2019.109544 (2020).

Rowley, C. W. & Dawson, S. T. M. Model reduction for flow analysis and control. Annu. Rev. Fluid Mech. 49, 387–417. https://doi.org/10.1146/annurev-fluid-010816-060042 (2017).

Westerhof, N., Elzinga, G. & Sipkema, P. An artificial arterial system for pumping hearts. J. Appl. Physiol. 31, 776–781. https://doi.org/10.1152/jappl.1971.31.5.776 (1971).

Frank, O. The basic shape of the arterial pulse. First treatise: mathematical analysis. J. Mol. Cell Cardiol. 22, 255–277. https://doi.org/10.1016/0022-2828(90)91460-o (1990).

Hughes, T. J. R. & Lubliner, J. On the one-dimensional theory of blood flow in the larger vessels. Math. Biosci. 18, 161–170. https://doi.org/10.1016/0025-5564(73)90027-8 (1973).

Alastruey, J. et al. Reduced modelling of blood flow in the cerebral circulation: Coupling 1-D, 0-D and cerebral auto-regulation models. Int. J. Numer. Meth. Fluids 56, 1061–1067. https://doi.org/10.1002/fld.1606 (2008).

Formaggia, L., Lamponi, D. & Quarteroni, A. One-dimensional models for blood flow in arteries. J. Eng. Math. 47, 251–276. https://doi.org/10.1023/b:engi.0000007980.01347.29 (2003).

Pfaller, M. R. et al. Automated generation of 0D and 1D reduced-order models of patient-specific blood flow. Int. J. Numer. Methods Biomed. Eng. 38, e3639. https://doi.org/10.1002/cnm.3639 (2022).

Bessems, D., Giannopapa, C. G., Rutten, M. C. M. & Van De Vosse, F. N. Experimental validation of a time-domain-based wave propagation model of blood flow in viscoelastic vessels. J. Biomech. 41, 284–291. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jbiomech.2007.09.014 (2008).

Olufsen, M. S. Structured tree outflow condition for blood flow in larger systemic arteries. Am. J. Physiol. 276, H257-268. https://doi.org/10.1152/ajpheart.1999.276.1.H257 (1999).

Alastruey, J. et al. Pulse wave propagation in a model human arterial network: assessment of 1-D visco-elastic simulations against in vitro measurements. J. Biomech. 44, 2250–2258. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jbiomech.2011.05.041 (2011).

Wasserthal, J. et al. TotalSegmentator: robust segmentation of 104 anatomic structures in CT Images. Radiol. Artif. Intell. 5, e230024. https://doi.org/10.1148/ryai.230024 (2023).

Isensee, F., Jaeger, P. F., Kohl, S. A. A., Petersen, J. & Maier-Hein, K. H. nnU-Net: a self-configuring method for deep learning-based biomedical image segmentation. Nat. Methods 18, 203–211. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41592-020-01008-z (2021).

Franklin, S. S. et al. Hemodynamic patterns of age-related changes in blood pressure: the Framingham Heart Study. Circulation 96, 308–315 (1997).

Mariscal-Harana, J. et al. Estimating central blood pressure from aortic flow: development and assessment of algorithms. Am. J. Physiol. Heart Circ. Physiol. 320, H494–H510. https://doi.org/10.1152/ajpheart.00241.2020 (2021).

Bai, W. et al. A population-based phenome-wide association study of cardiac and aortic structure and function. Nat. Med. 26, 1654–1662. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41591-020-1009-y (2020).

Córdova-Palomera, A. et al. Cardiac imaging of aortic valve area from 34 287 UK Biobank participants reveals novel genetic associations and shared genetic comorbidity with multiple disease phenotypes. Circul. Genom. Precis. Med. 13, 526. https://doi.org/10.1161/circgen.120.003014 (2020).

Henderson, G. E. et al. Characterizing biobank organizations in the US: results from a national survey. Genome Med. 5, 3 (2013).

Beeche, C. et al. Thoracic Aortic Three-Dimensional Geometry (Cold Spring Harbor Laboratory, 2024).

Antiga, L. et al. An image-based modeling framework for patient-specific computational hemodynamics. Med. Biol. Eng. Compu. 46, 1097–1112. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11517-008-0420-1 (2008).

Abdullateef, S., Mariscal-Harana, J. & Khir, A. W. Impact of tapering of arterial vessels on blood pressure, pulse wave velocity, and wave intensity analysis using one-dimensional computational model. Int. J. Numer. Methods Biomed. Eng. 37, e3312. https://doi.org/10.1002/cnm.3312 (2021).

Sherwin, S. J., Franke, V., Peiró, J. & Parker, K. One-dimensional modelling of a vascular network in space-time variables. J. Eng. Math. 47, 217–250. https://doi.org/10.1023/B:ENGI.0000007979.32871.e2 (2003).

Alastruey, J., Parker, K. H., Peiró, J., Byrd, S. M. & Sherwin, S. J. Modelling the circle of Willis to assess the effects of anatomical variations and occlusions on cerebral flows. J. Biomech. 40, 1794–1805. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jbiomech.2006.07.008 (2007).

Kissas, G. et al. Machine learning in cardiovascular flows modeling: predicting arterial blood pressure from non-invasive 4D flow MRI data using physics-informed neural networks. Comput. Methods Appl. Mech. Eng. 358, 526. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.cma.2019.112623 (2020).

Behnam, V. et al. Windkessel measures derived from pressure waveforms only: the Framingham heart study. J. Am. Heart Assoc. 8, e012300. https://doi.org/10.1161/JAHA.119.012300 (2019).

Haluska, B. A., Jeffriess, L., Brown, J., Carlier, S. & Marwick, T. H. A comparison of methods for assessing total arterial compliance. J. Hum. Hypertens. 24, 254–262. https://doi.org/10.1038/jhh.2009.92 (2010).

Khalifé, M. et al. Estimating absolute aortic pressure using MRI and a one-dimensional model. J. Biomech. 47, 3390–3399. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jbiomech.2014.07.018 (2014).

Ebbers, T., Wigström, L., Bolger, A. F., Engvall, J. & Karlsson, M. Estimation of relative cardiovascular pressures using time-resolved three-dimensional phase contrast MRI. Magn. Reson. Med. 45, 872–879 (2001).

Thompson, R. B. & McVeigh, E. R. Fast measurement of intracardiac pressure differences with 2D breath-hold phase-contrast MRI. Magn. Reson. Med. 49, 1056–1066 (2003).

Yang, G. Z., Kilner, P. J., Wood, N. B., Underwood, S. R. & Firmin, D. N. Computation of flow pressure fields from magnetic resonance velocity mapping. Magn. Reson. Med. 36, 520–526 (1996).

Chen, C.-H. et al. Estimation of central aortic pressure waveform by mathematical transformation of radial tonometry pressure. Circulation 95, 1827–1836. https://doi.org/10.1161/01.CIR.95.7.1827 (1997).

Zhu, Y. et al. Clinical validation and assessment of aortic hemodynamics using computational fluid dynamics simulations from computed tomography angiography. Biomed. Eng. Online 17, 53. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12938-018-0485-5 (2018).

Denny, J. C. et al. PheWAS: demonstrating the feasibility of a phenome-wide scan to discover gene–disease associations. Bioinformatics 26, 1205–1210. https://doi.org/10.1093/bioinformatics/btq126 (2010).

MacLean, M. T. et al. Quantification of abdominal fat from computed tomography using deep learning and its association with electronic health records in an academic biobank. J. Am. Med. Inform. Assoc. 28, 1178–1187. https://doi.org/10.1093/jamia/ocaa342 (2021).

Darabian, S., Zeb, I., Rezaeian, P., Razipour, A. & Budoff, M. Use of noninvasive imaging in the evaluation of coarctation of aorta. J. Comput. Assisted Tomogr. 37, 562 (2013).

Rajiah, P. CT and MRI in the evaluation of thoracic aortic diseases. Int. J. Vasc. Med. 2013, 797189. https://doi.org/10.1155/2013/797189 (2013).

Canan, A., Ghandour, A. A., Saboo, S. S. & Rajiah, P. S. Opportunistic screening at chest computed tomography: literature review of cardiovascular significance of incidental findings. Cardiovasc. Diagn. Ther. 13, 743–761. https://doi.org/10.21037/cdt-23-79 (2023).

Itu, L. et al. In 2012 9th IEEE International Symposium on Biomedical Imaging (ISBI) 832–835 (2012).

McComb, B. L. et al. Normative reference values of thoracic aortic diameter in American College of Radiology Imaging Network (ACRIN 6654) arm of National Lung Screening Trial. Clin. Imaging 40, 936–943. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.clinimag.2016.04.013 (2016).

Kallianos, K. G. & Burris, N. S. Imaging thoracic aortic aneurysm. Radiol. Clin. North Am. 58, 721–731. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.rcl.2020.02.009 (2020).

Verma, A. et al. The Penn Medicine BioBank: towards a genomics-enabled learning healthcare system to accelerate precision medicine in a diverse population. J. Pers. Med. 12, 526. https://doi.org/10.3390/jpm12121974 (2022).

Acknowledgements

The authors would like to thank the National Institutes of Health National Heart Lung and Blood Institute (R01 HL137984, R01 HL171709, R01 HL169378, T32 HL007954) and National Institute of Biomedical Imaging and Bioengineering (T32 EB009384, P41 EB029460) for their support of this project and PI Walter R.T. Witschey, PhD. We acknowledge the Penn Medicine BioBank (PMBB) for providing data and thank the patient-participants of Penn Medicine who consented to participate in this research program. We would also like to thank the Penn Medicine BioBank team and Regeneron Genetics Center for providing genetic variant data for analysis. The PMBB is approved under IRB protocol# 813913 and supported by Perelman School of Medicine at University of Pennsylvania, a gift from the Smilow family, and the National Center for Advancing Translational Sciences of the National Institutes of Health under CTSA award number UL1TR001878.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Consortia

Contributions

R.S. and A.B. contributed equally. R.S. and G.K. were involved in conceptualization of the problem statement, investigation, methodology, software development and preparation of the manuscript. A.B. contributed to the writing and review of the manuscript. E.T., C.B., S.S., J.C., S.D., A.V., P.P., D.R. were involved in conceptualization, investigation, methodology and writing of the manuscript. D.Z. and M.V. provided guidance on the methodology. C.M. was responsible for curation of the data and provided guidance on the methodology. W.W. contributed to conceptualization, investigation, methodology and writing of the manuscript as well as provided supervision for the study.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher’s note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Supplementary Information

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if you modified the licensed material. You do not have permission under this licence to share adapted material derived from this article or parts of it. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Sokolow, R., Bhattacharya, A., Kissas, G. et al. Reduced order computational fluid dynamic simulations in the thoracic aorta are associated with disease recorded in a medical biobank. Sci Rep 15, 39203 (2025). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-14401-5

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-14401-5