Abstract

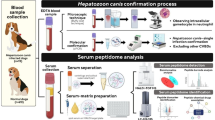

This study aimed to investigate the potential of peptide mass fingerprints (PMFs) of the serum peptidome using matrix-assisted laser desorption/ionization time-of-flight mass spectrometry (MALDI-TOF MS), in combination with machine learning algorithms—support vector machine (SVM) and random forest (RF)—for the diagnosis and classification of hepato-pancreato-biliary (HPB) cancers. Serum samples collected from healthy individuals and patients with various HPB cancers were analyzed to generate PMF profiles. The resulting data were randomly split into training and testing sets. Feature selection on the training set identified 71 informative peptide mass fingerprints, which were then used to construct predictive models using SVM and RF algorithms. Visualization using heatmap, PLS-DA, and multiclass RF analysis showed clear separation between healthy individuals and HPB cancer patients, as well as among different HPB cancer subtypes. Both models achieved high classification performance, with accuracy, AUROC, and MCC values exceeding 0.90 in both training and testing datasets. Notably, the models also exhibited strong multiclass discrimination ability. These findings demonstrate that serum PMF profiling using MALDI-TOF MS, combined with SVM and RF models, enables high-performance, non-invasive detection and classification of HPB cancers, with strong potential to support early diagnosis and inform clinical decision-making.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Hepato-pancreato-biliary (HPB) cancers, including cholangiocarcinoma (CCA), hepatocellular carcinoma (HCC), gallbladder cancer (GBC), and pancreatic ductal adenocarcinoma (PDAC), are among the most aggressive malignancies, often diagnosed at advanced stages with poor prognosis1,2. Surgery remains the only curative treatment, but resectability rates vary depending on the tumor type and stage at diagnosis3. Even in cases where surgical resection is possible, recurrence rates are high, and long-term survival remains limited3,4,5,6. Thus, early and accurate diagnosis is critical for improving patient outcomes. Current imaging techniques7such as computed tomography (CT) and magnetic resonance imaging (MRI), are essential tools for HPB cancer diagnosis but have limitations, particularly in distinguishing malignant from non-malignant conditions in early stages. Additionally, these imaging modalities require specialized expertise for accurate interpretation, which may not always be readily available. The high costs associated with CT and MRI can also limit their accessibility, particularly in resource-limited settings, further emphasizing the need for alternative diagnostic methods. Tissue biopsy, the gold standard for diagnosis, is invasive and may not always be feasible due to tumor location or patient conditions8. Meanwhile, conventional tumor biomarkers, such as carcinoembryonic antigen (CEA), carbohydrate antigen 19 − 9 (CA19-9), and alpha-fetoprotein (AFP), are widely used but suffer from poor specificity and sensitivity, particularly for early-stage disease. CA19-9, for instance, is commonly elevated in pancreatic cancer and CCA but lacks sufficient diagnostic accuracy, as it can also be increased in non-malignant biliary conditions9,10,11,12. Similarly, AFP, a commonly used biomarker for HCC, has limitations of cut-off values in detecting HCC13. These challenges highlight the need for novel, minimally invasive, and more reliable biomarkers to improve early detection and diagnosis.

Peptide biomarkers have emerged as promising candidates for cancer diagnosis, reflecting tumor progression, microenvironment changes, and metabolic alterations14,15. Peptides are small protein fragments generated from proteolytic processes, and they can be detected in biological fluids such as serum, plasma, and urine14. Their stability in circulation and potential specificity to particular cancer types make them attractive diagnostic tools16,17,18,19. In HPB cancers, peptide-based biomarkers could facilitate early detection and differentiation from non-cancerous conditions, ultimately aiding in clinical decision-making. Recent studies have demonstrated the potential of peptidome in cancer diagnostics, with mass spectrometry-based approaches identifying unique peptide signatures in multiple malignancies, including CCA and HCC20,21. Especially, matrix-assisted laser desorption/ionization time-of-flight (MALDI-TOF) mass spectrometry (MS)-based platforms, enables rapid peptide profiling and has been successfully applied to distinguish cancerous from non-cancerous conditions22,23,24,25,26. However, a comprehensive investigation of peptide biomarkers across multiple HPB cancers remains unexplored.

This study aims to identify candidate peptide mass fingerprints (PMFs) capable of distinguishing HPB cancers from healthy individuals using MALDI-TOF MS. Additionally, machine learning algorithms are applied to enhance classification accuracy and develop a predictive model for HPB cancer diagnosis. Furthermore, we evaluated the classification performance on the testing set to assess the robustness and generalizability of the model across different sample groups. These findings could contribute to the development of novel non-invasive diagnostic tools, ultimately improving HPB cancer detection and classification.

Results

Preoperative laboratory findings and tumor biomarker levels

In this study, a total of 297 participants were recruited comprising five groups: healthy control (HC; n = 50), cholangiocarcinoma (CCA; n = 138), gallbladder cancer (GBC; n = 16), hepatocellular carcinoma (HCC; n = 65), and pancreatic ductal adenocarcinoma (PDAC; n = 28). Prior to clinical and peptidome analyses, the samples were divided into a training set (n = 198) and a testing set (n = 99).

The experimental results revealed that liver function parameters (ALT, AST, ALP, bilirubin) and tumor biomarkers (CEA, CA19-9) were markedly elevated in patients with hepatobiliary and pancreatic (HPB) cancers compared to healthy individuals. Specifically, in the training set, median levels of AST and ALT in CCA patients were 32 and 29 U/L, respectively, compared to 21 and 18 U/L in healthy controls. PDAC patients showed the highest median levels of ALT (72 U/L) and AST (66 U/L), with some values reaching over 300 U/L, indicating severe hepatic involvement. Similarly, elevated total bilirubin levels were observed particularly in PDAC patients (median 4.0 mg/dL; range 0.5–31.0 mg/dL), in contrast to healthy individuals (median 0.5 mg/dL; range 0.1–6.4 mg/dL). Albumin levels tended to be slightly lower in cancer groups, reflecting impaired liver synthetic function, although the differences were not statistically significant.

In terms of tumor markers, both CEA and CA19-9 showed wide variation and tended to be higher in cancer groups; however, no statistically significant differences in these markers were found among the various cancer types. For example, median CA19-9 levels were 31.13 U/mL in CCA, 27.51 U/mL in GBC, 23.56 U/mL in HCC, and 25.5 U/mL in PDAC within the training cohort. CEA levels showed a similar pattern of elevation, particularly in CCA and PDAC cases, but again without statistical significance between cancer types.

The testing set exhibited consistent trends with the training set. Elevated liver enzymes and bilirubin levels persisted among HPB cancer patients, especially in PDAC, which had the highest AST (median 94 U/L) and ALT (median 93 U/L) levels. However, comparisons among different cancer types again did not reveal statistically significant differences in these parameters. Collectively, these results suggest that while liver function tests and tumor biomarkers can distinguish cancer patients from healthy individuals, they are insufficient to differentiate between specific cancer types in HPB malignancies (Table 1).

Peptide mass fingerprints for hepato-pancreato-biliary cancer diagnosis

A total of 1,100 peptide features were detected in serum of the training set by MALDI-TOF MS that showed markedly different patterns of peptide mass fingerprints (PMFs) between healthy and HPB cancers (Fig. 1A). The PMF spectra were transformed into expression z-scores and visualized as a heatmap to represent peptide mass fingerprint expression in healthy individuals and cancer patients. A total of 1,100 peptides within the m/z range of 1000–4000 were analyzed. In the heatmap, red indicates upregulated peptide expression, while blue indicates downregulated expression at each corresponding m/z position. The results revealed a clear distinction in PMF expression patterns between the healthy group and HPB cancers (Fig. 1B).

Peptide mass fingerprints (PMFs) of healthy controls and hepato-pancreato-biliary (HPB) cancer patients analyzed by MALDI-TOF MS. (A) Representative MALDI-TOF MS spectra showing markedly different peptide mass fingerprints between healthy individuals and HPB cancer patients within the m/z range of 1000–4000. A total of 1,100 peptide features were detected in serum samples from the training set. (B) Heatmap visualization of PMF expression after transformation into z-scores. Red indicates upregulated peptide expression, while blue indicates downregulated expression. The heatmap reveals a clear distinction in peptide expression patterns between the healthy and cancer groups.

Selection of key peptide mass fingerprints for hepato-pancreato-biliary cancer classification

Global PMF analysis was performed to identify peptide features capable of distinguishing healthy individuals from those with HPB cancers. In the training set, a total of 1,100 peptide peaks derived from MALDI-TOF MS were analyzed using MetaboAnalyst 6.0. Feature selection was carried out exclusively on the training set to prevent information leakage and to maintain the integrity of downstream analysis. Peptides with a variable importance in projection (VIP) score ≥ 1 from partial least squares discriminant analysis (PLS-DA) and statistical significance (p < 0.05) from one-way ANOVA were retained. This resulted in 71 peptides considered as informative features for distinguishing between groups.

In the training set, principal component analysis (PCA) revealed that the first two components accounted for 84.9% of the total variance (PC1 = 72.7%, PC2 = 12.2%). As illustrated in Fig. 2A, partial separation was observed between the CCA and HCC groups, whereas the healthy control, GBC, and PDAC groups tended to cluster together, suggesting shared peptide expression profiles among these latter groups. Similarly, the PLS-DA, a supervised classification method, demonstrated a comparable clustering pattern. The first two latent variables explained 84.8% of the variation (Fig. 2B), and the group distribution was consistent with the PCA results. Although PLS-DA typically improves group separation due to its supervised nature, in this case, the separation between groups was similar to that observed in PCA, indicating that intrinsic differences among groups were already evident without model supervision. These findings were further supported by the analysis of the global PMF dataset containing 1,100 peptides, which exhibited consistent distribution patterns in both the PCA and PLS-DA score plots (Supplementary Fig. S1A and B). The top 15 peptide features with the highest VIP scores were identified as key contributors to this separation (Fig. 2C). Cross-validation of the PLS-DA model demonstrated strong robustness, with increasing R² and Q² values as additional components were included. The optimal model achieved R² = 0.564 and Q² = 0.502, indicating good explanatory and predictive performance. Furthermore, permutation testing with 2,000 iterations confirmed the absence of overfitting (p < 5 × 10⁻⁴; Fig. 2D).

Multivariate analysis and classification performance based on 71 selected peptide features in the training and testing sets. (A) PCA score plot showing partial separation of CCA and HCC groups, with clustering of healthy control, GBC, and PDAC groups in the training set. (B) PLS-DA score plot demonstrating a comparable group distribution to PCA, based on the 71 selected peptides. (C) Top 15 peptide features ranked by VIP scores from the PLS-DA model. (D) PLS-DA cross-validation results showing optimal model performance (R2 = 0.564, Q2 = 0.502), with permutation testing (N = 2,000) confirming the absence of overfitting in the training set. (E) Heatmap of average peptide expression levels across groups, with peptides ordered by increasing mass. (F) Random Forest model classification results, achieving an out-of-bag (OOB) error rate of 2.2%. (G,H) PCA and PLS-DA score plots in the independent testing set, showing clustering patterns consistent with the training set. (I) Top 15 VIP-ranked peptides in the testing set, 13 of which overlapped with those identified in the training set. (J) Heatmap of average peptide expression levels across groups in the testing set, showing consistent expression trends. (K) RF classification performance in the testing set, yielding an OOB error rate of 3.5%.

The heatmap illustrating the expression patterns of 71 peptides across each group, ordered by increasing mass, based on average peptide expression per group, revealed distinct differential expression profiles (Fig. 2E). Individual peptide expression profiles for each participant were also presented in Supplementary Fig. S2A, highlighting consistent variation both within and between groups.

To further evaluate classification performance, a Random Forest (RF) model was constructed using the 71 selected peptides. This model achieved an out-of-bag (OOB) error rate of only 2.2%, substantially lower than the 5.56% error rate observed when using all 1,100 peptides (Supplementary Fig. S1C). Subgroup classification error rates were similarly low: 0% for healthy controls and PDAC, 1.8% for CCA, and 2.2% for HCC. The only notable misclassification occurred in the GBC group, with an error rate of 18.8% (Fig. 2F).

To assess the robustness and generalizability of the 71 selected peptide features, the same analytical workflow was applied to the independent testing set. Both PCA and PLS-DA score plots (Fig. 2G–H) demonstrated clustering patterns that closely mirrored those observed in the training set. Partial separation was maintained between the CCA and HCC groups, whereas the healthy control, GBC, and PDAC groups continued to cluster more closely, suggesting similar expression trends. These observations support the stability of the peptide-based classification across independent datasets. Among the top 15 features ranked by VIP scores, 13 peptides overlapped with those identified in the training set, further indicating strong reproducibility of discriminative markers (Fig. 2I). Cross-validation and permutation testing in the testing set confirmed the reliability of the PLS-DA model, with no signs of overfitting (Supplementary Fig. S3).

The heatmap of the 71 peptides, based on average expression and ordered by increasing mass, also revealed group-specific expression profiles (Fig. 2J), which was consistent with those seen in the training set. Individual-level peptide expression profiles were presented in Supplementary Fig. S2B, highlighting consistent intra- and intergroup variation.

Furthermore, the RF model demonstrated sustained classification performance in the testing set, achieving an OOB error rate of 3.5% (Fig. 2K). Collectively, these findings reinforce the discriminative power and reproducibility of the 71 selected peptides and underscore their potential utility as peptide mass fingerprint-based biomarkers for distinguishing HPB cancer subtypes from healthy individuals.

Investigation of classification performance in PMFs for hepato-pancreato-biliary cancers diagnosis using support vector machine and random forest models

To evaluate the diagnostic performance of the 71 candidate PMFs, binary classification models—Support Vector Machine (SVM) and Random Forest (RF)—were employed to distinguish healthy individuals from patients with HPB cancers, including CCA, GBC, HCC, and PDAC. These models were constructed using the web-based MetaboAnalyst platform with default settings. The performance evaluation was based on commonly calculated from confusing matrix, including accuracy, precision, recall, F1-score, and the area under the receiver operating characteristic curve (AUC-ROC). In addition, Matthews Correlation Coefficient (MCC) was also calculated to provide a more balanced assessment of classification performance. MCC is particularly valuable in binary classification problems involving imbalanced class distributions, as it considers all four categories of the confusing matrix (true positives, true negatives, false positives, and false negatives) and provides a more balanced measure than accuracy alone. An MCC value of + 1 indicates perfect prediction, 0 indicates random prediction, and − 1 indicates total disagreement between prediction and observation.

In the training set (n = 198), the SVM model demonstrated excellent classification performance, achieving 98.74% accuracy for distinguishing healthy individuals (n = 29) from all cancer cases (n = 169), with a precision of 99.70%, recall of 98.82%, F1-score of 0.99, TNR of 98.28%, MCC of 0.95, and ROC of 0.999. Individual comparisons with each cancer type revealed perfect classification for CCA, GBC, and HCC (MCC = 1.00), and nearly perfect classification for PDAC (MCC = 0.99) (Table 2; Fig. 3A). In the testing set (n = 99), SVM performance remained robust. The model yielded 98.55% accuracy for healthy vs. all cancer cases, with an MCC of 0.97, and ROC of 0.999. Comparisons between healthy individuals and each cancer type also showed high MCC values: CCA (0.99), GBC (0.94), HCC (1.00), and PDAC (0.94) (Table 2; Fig. 3A).

Receiver operating characteristic (ROC) curves and feature importance of SVM and Random Forest models based on 71 candidate peptides. (A) ROC curves comparing healthy controls and HPB cancers. (B) Top 15 peptides ranked by mean importance scores from SVM and random forest. (C–F) ROC curves for pairwise comparisons between CCA vs. HPB cancers (C), GBC vs. HPB cancers (D), HCC vs. HPB cancers (E), and PDAC vs. HPB cancers (F). Blue curves represent SVM models, while red curves indicate Random Forest models. ROC performance is reported as AUC with 95% confidence intervals. Classification metrics include TPR (true positive rate), TNR (true negative rate), FPR (false positive rate), and FNR (false negative rate), calculated from the corresponding confusion matrices.

The RF model also performed well. In the training set, the healthy vs. all cancer classification achieved 97.10% accuracy, with precision of 99.85%, recall of 96.75%, MCC of 0.90, and ROC of 0.998. Comparisons with individual cancer types showed perfect classification in all cases (MCC = 0.99–.00) (Table 3; Fig. 3A). In the testing set, RF showed slightly lower performance for the healthy vs. all cancer group (accuracy: 89.14%, MCC: 0.76, ROC: 0.988). MCC values for individual comparisons were as follows: CCA (1.00), GBC (0.81), HCC (1.00), and PDAC (0.87) (Table 3; Fig. 3A).

In addition, to identify the most important peptides for classification, a mean importance measure was calculated for both SVM and RF models. In RF, peptide importance was derived from the mean decrease in accuracy across trees, while SVM used recursive feature elimination (RFE) with cross-validation to rank features by their contribution. The mean importance score reflects the average impact of each peptide across all model iterations. The Top 15 peptides with the highest importance scores were consistent across both models, indicating that despite their different learning methods, both algorithms identified a similar set of key features (Fig. 3B). This consistency points to a robust, model-independent signature, reinforcing the biological and statistical relevance of these peptides in distinguishing the sample groups. The convergence of important features across models strengthens confidence in their predictive value, suggesting that the observed classification performance is driven by strong, reproducible signals rather than being model-specific.

In addition, we utilized 71 PMFs to develop SVM and RF models for the classification of HPB cancers using a one-vs-all (OvA) classification strategy. This approach was adopted to support potential clinical application, as HPB cancers often present with overlapping anatomical locations, making differential diagnosis challenging. Therefore, the OvA strategy was applied to enhance the discriminative power of the models in this context.

In the training set, the SVM model demonstrated excellent performance in differentiating each HPB cancer subtype from the remaining cancer types. The classification accuracy was highest for HCC vs. other HPB cancers (accuracy = 94.97%, MCC = 0.88, ROC = 0.989), followed by PDAC (accuracy = 94.67%, MCC = 0.80, ROC = 0.993), CCA (accuracy = 92.60%, MCC = 0.85, ROC = 0.989), and GBC (accuracy = 90.98%, MCC = 0.56, ROC = 0.987) (Table 4; Fig. 3C–F). Notably, precision and specificity (TNR) values reached 100% for GBC and PDAC, although recall was relatively lower, particularly for GBC (34.41%).

In the testing set, the SVM model maintained high discriminatory power across all cancer subtypes. The model achieved near-perfect classification performance for HCC (accuracy = 99.68%, MCC = 0.99, ROC = 1) and CCA (accuracy = 99.04%, MCC = 0.98, ROC = 1), followed by strong performance for GBC (accuracy = 94.87%, MCC = 0.78, ROC = 0.997) and PDAC (accuracy = 91.67%, MCC = 0.73, ROC = 0.994) (Table 4; Fig. 3C-F). These results underscore the model’s robustness and reliability, particularly in distinguishing CCA and HCC from other HPB cancer types.

Similarly, the RF model also yielded strong classification performance across most comparisons. In the training set, classification accuracy was highest for PDAC (95.12%, MCC = 0.81, ROC = 0.985), followed by CCA (94.38%, MCC = 0.89, ROC = 0.996), HCC (91.42%, MCC = 0.82, ROC = 0.989), and GBC (90.24%, MCC = 0.54, ROC = 0.981) (Table 5; Fig. 3C-F). Precision remained high across all subtypes (≥ 98.68%), but recall was markedly lower for GBC (32.65%), similar to the SVM model.

In the testing set, the RF model performed particularly well for CCA (accuracy = 97.76%, MCC = 0.96, ROC = 0.999) and HCC (accuracy = 95.51%, MCC = 0.89, ROC = 0.997), and to a slightly lesser extent for GBC (accuracy = 91.67%, MCC = 0.71, ROC = 0.989) and PDAC (accuracy = 91.99%, MCC = 0.73, ROC = 0.979) (Table 5; Fig. 3C–F). These findings confirm the consistent diagnostic potential of PMFs in differentiating between HPB cancer subtypes, with both SVM and RF models demonstrating high reliability, though SVM generally showed slightly superior performance, particularly in handling class imbalance and recall rates for certain subtypes.

To reduce model complexity, the top five discriminative peptides from each group were selected and used to construct classification models using SVM and RF algorithms under an OvA framework. As shown in Supplementary Fig. S4–S6, reducing the number of peptides to five per class resulted in a noticeable decrease in classification performance in both the training and testing sets when compared to the full model using 71 peptides. This decline was particularly reflected by the lower MCC values observed across all comparisons, as detailed in Supplementary Table S1.

In addition, to evaluate the relative diagnostic performance of peptide-based models, we constructed additional SVM and random forest models using clinical biomarkers included in the STARD checklist (ALT, AST, ALP, total bilirubin, CEA, and CA19-9). Specifically, we developed models based on (1) clinical biomarkers alone, which served as the baseline, and (2) a combination of clinical biomarkers and the 71 peptide mass features (PMFs). The baseline models trained using only the clinical biomarkers (Supplementary Table S2–3) demonstrated inferior performance compared to the models using the 71 PMFs alone, as evidenced by lower overall metrics. This finding indicates that peptide-based features possess superior discriminatory power in our dataset. Notably, adding clinical biomarkers to the 71 PMFs (Supplementary Table S4–5) did not significantly improve model performance, suggesting that the selected peptides alone are sufficient and may already capture the diagnostic information provided by conventional biomarkers.

These results suggest that PMFs provide high discriminatory power in differentiating healthy individuals from HPB cancer patients. The high MCC values across most comparisons, particularly in the SVM model, confirm the reliability and robustness of these models, even in the presence of class imbalance. Both SVM and RF classification models demonstrated strong diagnostic potential for identifying HPB cancers, with SVM performing slightly better in most scenarios, including the ability to handle class imbalance more effectively. These findings emphasize the value of PMFs as promising biomarkers for cancer diagnosis, offering both high sensitivity and specificity for clinical applications in HPB cancer screening and detection. In addition to distinguishing between healthy individuals and patients with HPB cancers, PMFs also exhibited strong classification performance in differentiating among individual HPB cancer subtypes, further supporting their utility for both general diagnosis and precise cancer subtype classification.

Discussion

Hepato-pancreato-biliary (HPB) cancers—including cholangiocarcinoma (CCA), hepatocellular carcinoma (HCC), gallbladder cancer (GBC), and pancreatic ductal adenocarcinoma (PDAC)—are associated with poor prognosis, primarily due to late-stage diagnosis and high recurrence rates, even after potentially curative surgical resection. The limitations of existing diagnostic modalities, such as computed tomography (CT), magnetic resonance imaging (MRI), and conventional tumor biomarkers, highlight the urgent need for novel, accurate, and minimally invasive diagnostic tools—particularly for the early stages of disease, when timely intervention can significantly improve clinical outcomes.

Peptide biomarkers—short chains of amino acids detectable in biological samples—play a vital role in disease diagnostics by indicating disease presence, progression, response to therapy, and clinical prognosis. Commonly used biomarkers include carcinoembryonic antigen (CEA) and cancer antigen 19 − 9 (CA 19 − 9)27 in cancer care, prostate-specific antigen (PSA) for prostate cancer28 and amyloid-beta peptides in Alzheimer’s disease17. Although some may lack specificity, these markers are essential for assessing treatment response and monitoring disease recurrence. Their capacity to capture molecular alterations makes them valuable tools for early detection, improving diagnostic precision, and advancing personalized medicine.

In this study, we evaluated the diagnostic potential of serum peptide mass fingerprints (PMFs) generated using matrix-assisted laser desorption/ionization time-of-flight mass spectrometry (MALDI-TOF MS) for HPB cancers. Based on the peptide pattern analysis (Fig. 1A–B), our findings demonstrated that this approach could reliably distinguish between healthy individuals and patients with various types of HPB malignancies. Importantly, the integration of advanced statistical and machine learning techniques enabled the identification of a panel of 71 peptide features with high discriminatory power and reproducibility (Fig. 2A–E). Furthermore, the 71 peptides selected during the feature selection process were used to train classification models and subsequently evaluated in an independent testing set. To prevent overfitting and ensure the reliability of the model, the dataset was randomly split into training and testing subsets prior to analysis. The performance of the classification model in the testing set (Fig. 2F–I) showed comparable accuracy to that observed in the training set, highlighting the robustness and generalizability of the candidate PMFs. These results suggest that the 71-peptide signature captures key molecular features associated with HPB malignancies and possesses strong potential for clinical application in HPB cancers diagnosis and classification. The consistent performance across both training and testing datasets underscores the stability of the peptide-based model and supports its utility as a reliable, non-invasive diagnostic tool.

Furthermore, the integration of machine learning models enhances the predictive capability and objectivity of the diagnostic process, potentially reducing inter-observer variability and ensuring consistent interpretation, even in resource-limited settings. Given its relatively low cost, rapid throughput, and minimal sample volume requirements, the MALDI-TOF MS-based serum peptidome presents a feasible diagnostic solution with the potential for broad clinical implementation. In this study, machine learning algorithms, including support vector machine (SVM) and Random Forest (RF), were applied via the user-friendly MetaboAnalyst platform to evaluate the classification performance of 71 selected peptides. The platform enables non-programmers, such as clinicians, to perform advanced analyses through an intuitive web interface. Subsequently, the model performance was assessed using confusing metrics, including accuracy (ACC), precision, recall, F1-score, true negative rate (TNR), area under the receiver operating characteristic curve (ROC), and the Matthews correlation coefficient (MCC). Notably, MCC provided a balanced evaluation, especially in datasets prone to class imbalance29—a challenge often encountered in clinical research. Both the SVM and RF models, developed from the 71-peptide panel, exhibited exceptional classification performance, demonstrating a robust ability to distinguish healthy individuals from patients with HPB malignancies. The models achieved high accuracy in identifying healthy controls and HPB cancers (Tables 2 and 3; Fig. 3A). These strong results across both training and testing sets emphasize the biological relevance, robustness, and diagnostic potential of the selected PMFs biomarkers for reliable disease classification.

Additionally, the study highlights the use of PMFs as input variables for machine learning models in classifying HPB cancers using the one-vs-all (OvA) strategy. This approach, essential given the overlapping anatomical locations and similar clinical presentations of HPB cancers2improves diagnostic precision and supports modular decision-making in clinical practice. The SVM model exhibited strong discriminative power, with the highest accuracy and MCC for HCC vs. others, followed by PDAC, CCA, and GBC. Precision and specificity reached 100% for GBC and PDAC, though the recall for GBC was lower, indicating difficulty in identifying all positive cases. These results were validated in the testing set, where the model performed nearly perfectly for HCC and CCA, with slightly reduced but still robust metrics for GBC and PDAC, highlighting its potential for accurate differential diagnosis of HPB cancers (Table 4; Fig. 3C-F). The RF model also performed well across most subtypes, with similar results to the SVM model, especially for CCA and HCC. The SVM model had a slight edge in handling class imbalance30 particularly for GBC, but both models showed strong diagnostic potential, evidenced by high precision and ROC values (Table 5; Fig. 3C-F). The OvA strategy, despite inherent class imbalances30 offers a translational advantage by addressing the primary clinical question of whether a specific cancer type is present. While the one-vs-one (OvO) strategy may provide better separation in early-stage analyses, it becomes less feasible as the number of cancer types increases due to computational constraints31. Thus, OvA remains a practical, scalable approach for real-world clinical applications. Despite its advantages, the OvA strategy introduces class imbalance, especially for underrepresented subtypes like GBC. While stratified sampling and class weighting mitigated this issue, the imbalance could still reduce sensitivity for certain classes. Future studies should aim to acquire more balanced datasets and explore advanced sampling techniques like synthetic minority over-sampling (SMOTE) or ensemble methods to address this challenge32. Additionally, integrating clinical variables or multi-omics data could further enhance the classification performance for challenging subtypes. By refining data balance and model design, future research could develop more accurate, clinically reliable tools for classifying HPB cancers and other cancer types.

Our findings are consistent with studies across several types of cancers, which demonstrated the broad application of peptide-based biomarkers in clinical diagnosis20,22,23,24,33,34. In CCA, PMF analysis has demonstrated robust performance in distinguishing cancer patients from healthy controls20. Importantly, this approach can further stratify CCA recurrence subtypes, offering essential prognostic information35. Given that these subtypes frequently correlate with adverse clinical outcomes regardless of disease stage, such discrimination holds significant clinical value. Similarly, in prostate cancer, MALDI-TOF MS-derived PMFs have demonstrated high discriminatory power, enabling precise differentiation between healthy individuals and prostate cancer patients with exceptional sensitivity and specificity24. In the same way, hepatocellular carcinoma, PMF analysis has revealed distinct peptide signatures that reliably distinguish cancer patients from healthy controls, underscoring their clinical utility as robust diagnostic indicators21. In cervical cancer, PMF analysis using MALDI-TOF MS has uncovered distinctive peptide signatures that effectively discriminate between healthy individuals, patients with precancerous lesions, and those at different stages of malignancy. Notably, specific mass-to-charge (m/z) peaks—1466.91, 1898.01, 3159.09, and 4299.40—were identified as robust discriminators, highlighting their potential as diagnostic biomarkers for disease stratification23. In ovarian cancer, peptide-based biomarkers identified through MALDI-TOF MS have proven highly effective in distinguishing cancer patients from healthy individuals, reflecting strong diagnostic performance36. Notably, these biomarkers also differentiated non-malignant cases—such as patients with ovarian cysts—from both healthy subjects and those with ovarian cancer, demonstrating remarkable specificity37. Additionally, they showed outstanding ability to classify different stages of ovarian cancer, with reported sensitivities between 95% and 97% and a specificity of 97%38. These findings highlight the remarkable versatility and diagnostic power of peptide-based biomarkers across multiple cancer types, positioning them as valuable tools for early detection and precise disease classification.

In addition to their role in cancer diagnostics, peptide biomarkers are increasingly being recognized in various medical fields for their potential in early disease detection and monitoring disease progression. Their non-invasive characteristics, rapid screening, and cost-effectiveness make them especially valuable for distinguishing between normal and diseased states, as well as for assessing changes throughout the course of illness.

These findings highlight the pivotal role of peptide-based biomarkers, identified through mass spectrometry (MS), in improving the diagnosis and classification of HPB cancers. Building upon this, our study employs an integrated approach that combines high-throughput screening with predictive modeling to improve HPB cancer detection and stratification. Firstly, we successfully identified candidate 71 PMFs that not only facilitate the diagnosis of HPB cancers but also differentiate among various HPB cancer types. Secondly, we implemented machine learning algorithms, including SVM and RF models, constructed from these candidate PMFs. These models achieved high classification accuracy, effectively distinguishing between disease stages and types, thereby supporting personalized diagnostics. Thirdly, we validated the performance of the candidate PMFs using testing sets that were separated prior to PMF identification. The diagnostic efficacy observed in the testing sets closely mirrored that of the training sets, demonstrating the robustness of our approach. Collectively, the integration of MALDI-TOF MS and machine learning models forms a synergistic framework that combines rapid screening and advanced classification. This comprehensive approach holds significant promise for improving the detection and diagnosis of HPB cancers.

In clinical practice, MALDI-TOF MS enables the rapid generation of patient-specific peptide profiles from serum samples, facilitating an efficient and personalized diagnostic approach. These profiles are compared against a comprehensive, established peptide biomarker database, allowing for an immediate and accurate match with known cancer-associated signatures. This innovative technique not only aids in the detection of HPB cancers but also supports the differentiation of various HPB cancer types based on their distinct peptide patterns. By integrating MALDI-TOF MS with advanced machine learning algorithms, we can enhance the diagnostic capability, enabling early detection and more precise classification of HPB cancers as shown in summary in supplementary Fig. S7. This method promises to significantly improve clinical outcomes by providing faster, more reliable diagnostics for better patient management.

While the present study demonstrates promising findings, several limitations should be considered when interpreting and applying the results. First, this study was conducted using a single-institution cohort primarily composed of patients from Northeastern Thailand, where cholangiocarcinoma and liver fluke (Opisthorchis viverrini) infection are highly prevalent. As such, the findings may be more generalizable to populations in endemic areas of Southeast Asia, but caution is warranted when extrapolating these results to non-endemic regions or populations with different etiological backgrounds. Second, the number of cases in certain cancer subtypes, such as gallbladder and pancreatic cancers, was relatively small. This limited sample size may reduce the robustness of the machine learning models, increase the risk of overfitting, and affect the reliability of biomarker identification in these groups. Finally, further subgroup analyses, such as comparisons between precancerous lesions and different cancer stages, are necessary to better understand the stage-specific characteristics and potential diagnostic applications of the identified features.

Taken together, these limitations underscore the importance of cautious interpretation and clearly indicate the need for further studies. Specifically, future multicenter investigations involving larger and more diverse populations, as well as independent external validation cohorts, are essential to confirm and strengthen the clinical applicability and generalizability of our findings. In parallel, potential PMFs that showed diagnostic value in this study will be identified using LC-MS/MS. This identification step is a critical bridge toward the development of a robust biomarker panel, which represents the ultimate goal of MS-based peptidome research for clinical application.

In summary, our study showed that PMF via MALDI-TOF MS serves as a rapid and effective screening tool for detecting peptide patterns associated with HPB cancers. By employing machine learning algorithms such as SVM and RF, we achieved high classification accuracy in distinguishing between healthy individuals and patients with various HPB malignancies across both training and testing datasets. The combined application of MALDI-TOF MS and machine learning algorithms not only improves diagnostic accuracy but also holds substantial potential as an adjunct to traditional diagnostic methods. This integrated approach offers a promising alternative for enhancing the early detection and classification of HPB cancers, thereby facilitating more informed clinical decision-making and potentially improving patient outcomes.

Materials and methods

Ethics approval and consent to participate

This study was conducted based on the principles of Good Clinical Practice, the Declaration of Helsinki, and national laws and regulations about clinical studies. In addition, informed consent was obtained from all patients. All processes of this study were accepted and approved by the Khon Kaen University Ethics Committee for Human Research under the reference number HE551404 and HE661318.

Population and sample group

In this study, a total of 297 participants were recruited and split into a training set (n = 198) and a testing set (n = 99). Participants were categorized into five groups: healthy controls (n = 50; training set, n = 29; testing set, n = 21), cholangiocarcinoma (CCA; n = 138; training set, n = 97; testing set, n = 41), gallbladder cancer (GBC; n = 16; training set, n = 8; testing set, n = 8), hepatocellular carcinoma (HCC; n = 65; training set, n = 45; testing set, n = 20), and pancreatic ductal adenocarcinoma (PDAC; n = 28; training set, n = 19; testing set, n = 9). To protect patient privacy and ensure confidentiality, all participants were assigned anonymized identifiers. The list of these anonymized patient IDs for the training and testing sets is provided in Supplementary Table S6.

Serum samples from the healthy controls were collected from individuals undergoing health screenings at the Srinagarind Hospital Blood Bank, Faculty of Medicine, Khon Kaen University, with approval granted by the Director of Srinagarind Hospital. Serum samples from the Hepato-pancreato-biliary (HPB) cancer groups were sourced from the biobank at the Cholangiocarcinoma Research Institute, Khon Kaen University. Clinical data for the patients were retrospectively collected from medical records at Srinagarind Hospital, Faculty of Medicine, Khon Kaen University, covering patient information from January, 2017, to December, 2021. Prognostic factors were gathered using a retrospective data collection form from the patient medical records, utilizing the ISAN Cohort database at the Cholangiocarcinoma Research Institute, Faculty of Medicine, Khon Kaen University. The data collected included age at diagnosis, gender, histological confirmation, tumor size, cancer grade, surgical margins, lymph and cancer staging.

Sample collection and serum preservation

Serum samples were collected from healthy individuals and patients with hepatobiliary diseases prior to surgical treatment. Blood was drawn via venipuncture into a 5-milliliter clot blood tube. It was ensured that clot formation was complete before centrifugation. The serum was then separated from red blood cells by centrifugation at 3,000–3,500 RPM at 4 °C for 10 min. The serum was carefully aspirated and aliquoted into 1-microliter portions in Eppendorf tubes to prevent repeated thawing of samples. These aliquots were stored at -80 °C in the biobank of the Cholangiocarcinoma Research Institute, Khon Kaen University, until further analysis. Protein quantification was performed using the Lowry assay.

Peptide barcode analysis using MALDI-TOF MS

Each serum sample was analyzed in quadruplicate (i.e., four technical replicates per patient) to ensure reproducibility and reduce technical variability. For each replicate, the serum was mixed with a matrix solution consisting of α-cyano-4-hydroxycinnamic acid (CHCA) in 50% acetonitrile and 0.1% trifluoroacetic acid at a sample-to-matrix ratio of 1:5. The mixture was then spotted onto a MALDI target plate (MTP 384 ground steel, JEOL, Japan), with each sample applied in 30 replicates. After drying at room temperature, the plate was analyzed using the JMS-S3000 SpiralTOF-Plus (JEOL, Japan) in a linear positive mode, targeting peptide barcodes within a mass range of 1,000 to 10,000 Da. Each sample was subjected to 1,500 laser shots. Data acquisition was performed using JEOL msTornado Control version 1.16 (JEOL, Japan), and subsequent processing was carried out with JEOL msTornado Analysis version 1.15 (JEOL, Japan). Spectra were processed using default settings for smoothing, variance stabilization, baseline correction, and peak detection, followed by export in CSV format for further analysis. Mass binning was applied at 1.0 Da intervals across the 1,000–10,000 Da range. Prior to analysis, the instrument was externally calibrated in positive-ion mode using a set of reference peptides with known mass-to-charge ratios (m/z): Angiotensin II (m/z = 1046), P14R (m/z = 1533), human ACTH fragment 18–39 (m/z = 2465), bovine insulin oxidized B chain (m/z = 3465), and bovine insulin (m/z = 5731). Calibration was performed manually using JEOL msTornado Control version 1.16, ensuring mass accuracy within ± 100 ppm.

Support vector machine model

The Support Vector Machine (SVM) model was used to classify and predict potential biomarkers from the candidate metabolites identified in serum samples. The candidate metabolites were selected based on feature selection criteria according to VIP ≥ 1 from PLS-DA analysis, ANOVA test: FDR-adjusted p < 0.05, which were considered significant for the discriminatory model. Using the MetaboAnalyst 6.0 platform, 71 PMFs from the training set were first normalized to ensure uniform scaling. The SVM model was applied using a Radial Basis Function (RBF) kernel (default kernel in MetaboAnalyst), and cross-validation techniques such as 10-fold cross-validation were used to assess the model generalizability and to avoid overfitting. The default parameters for the SVM model included a cost value of 1 and gamma value of 1/n, where n is the number of features (default settings in MetaboAnalyst). The model performance was evaluated using classification metrics such as accuracy, precision, recall, F1-score, specificity, Matthews correlation coefficient (MCC), and area under the curve (AUC) based on the training set39. The SVM model developed from the training set was then validated using an independent testing set, and model performance was further assessed through the same classification metrics (accuracy, precision, recall, F1-score, specificity, MCC and AUC) derived from the testing set.

Random forest model

The Random Forest (RF) model was employed to perform binary classification between healthy individuals and patients with HPB cancers based on the 71 selected PMFs. The analysis was conducted using the MetaboAnalyst 6.0 web-based platform40. Prior to model construction, data from the training set were normalized to ensure comparability across features. The default settings provided by MetaboAnalyst were used, which include the use of 500 decision trees (ntree = 500) and a default value of mtry (number of variables randomly sampled as candidates at each split) set to the square root of the total number of features. Model performance was evaluated using 10-fold cross-validation to prevent overfitting and to assess the generalizability of the model. Classification metrics reported included accuracy, precision, recall (sensitivity), specificity, F1-score, AUROC, and MCC. After training, the model was validated using an independent testing set, and the same metrics were calculated to assess predictive performance on unseen data.

Model performance estimation

After classification using SVM and RF models, receiver operating characteristic (ROC) curves were generated to evaluate the overall discriminative ability of each model across various classification thresholds. The AUC was calculated to provide a threshold-independent performance metric, offering an aggregate measure of model performance based on the trade-off between the true positive rate (TPR) and the false positive rate (FPR) at different thresholds. These values were derived from components of the confusion matrix—true positives (TP), false positives (FP), true negatives (TN), and false negatives (FN)—calculated at each threshold.

Following ROC analysis, a classification threshold was selected to construct the confusion matrix for each model. The confusion matrix enabled a detailed evaluation of model performance at the chosen threshold by summarizing classification outcomes into TP, FP, TN, and FN categories. Based on these values, several performance metrics were calculated, including accuracy, sensitivity (recall), specificity, precision, F1-score, and MCC. Notably, MCC was included as it provides a more informative and balanced measure for evaluating binary classification performance, particularly when class distributions are imbalanced. MCC considers all four elements of the confusion matrix and ranges from − 1 (completely incorrect classification) to + 1 (perfect classification), with 0 indicating random performance29.

Bioinformatics analysis of peptidome data

Four technical replicates (quadruplicates) were acquired per sample using MALDI-TOF MS, and these spectra were subsequently subjected to comprehensive bioinformatics analysis, including visualization and statistical assessment. Principal Component Analysis (PCA), Partial Least Squares-Discriminant Analysis (PLS-DA), differential analysis (one-way ANOVA), heatmap visualization, and machine learning approaches such as Support Vector Machine and Random Forest models were conducted using MetaboAnalyst version 6.0 (https://www.metaboanalyst.ca/). A significance threshold of p < 0.05 was applied, and p-values below this threshold were considered statistically significant.

Data availability

Raw MALDI-TOF MS data supporting the findings of this study are available from the corresponding author upon reasonable request.

References

Akhoundova, D., Fritsch, R. M. & Hussung, S. J. h. T. O. H. Precision oncology for hepato-pancreato-biliary (HPB) cancers state of the art and future directions. 5, 52–59 (2020).

Kerekes, D. M. et al. Hepatopancreatobiliary malignancies: time to treatment matters. J. Gastrointest. Oncol. 14, 833–848. https://doi.org/10.21037/jgo-22-1067 (2023).

Maspero, M., Sposito, C., Mazzaferro, V., Ercolani, G. & Cucchetti, A. Cure after surgery for hepato-pancreato-biliary cancers: A systematic review. Dig. Liver Disease. 57, 1–7. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.dld.2024.06.021 (2025).

Margonis, G. A. et al. Rates and patterns of recurrence after curative intent resection for gallbladder cancer: a multi-institution analysis from the US Extra-hepatic biliary malignancy consortium. HPB (Oxford). 18, 872–878. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.hpb.2016.05.016 (2016).

Xiang, Y. J. et al. Recurrence hazard rate in patients with hepatocellular carcinoma and bile duct tumor thrombus: a multicenter observational study. HPB 24, 1703–1710. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.hpb.2022.04.007 (2022).

Evans, D., Hajibandeh, S., Hajibandeh, S. & Athwal, T. HPB SO43 - Meta-analysis of completion pancreatectomy for local recurrence of pancreatic cancer after the index pancreatectomy. Br. J. Surg. 111 https://doi.org/10.1093/bjs/znae271.275 (2024).

Jajodia, A., Soyer, P., Barat, M. & Patlas, M. N. Imaging of hepato-pancreato-biliary emergencies in patients with cancer. Diagn. Interv. Imaging. 105, 47–56. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.diii.2023.11.002 (2024).

Elbanna, K. Y. & Kielar, A. Z. Computed tomography versus magnetic resonance imaging for hepatic lesion characterization/diagnosis. 17, 159–164 https://doi.org/10.1002/cld.1089 (2021).

Wu, C. H. et al. Comparative radiological pathological study of biliary intraductal tubulopapillary neoplasm and biliary intraductal papillary mucinous neoplasm. Abdom. Radiol. (NY). 42, 2460–2469. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00261-017-1167-7 (2017).

Fujii, M., Okamoto, Y. & Shiode, J. A case of cystic intraductal papillary neoplasm of the bile duct with associated adenocarcinoma. Clin. J. Gastroenterol. 13, 219–224. https://doi.org/10.1007/s12328-019-01040-3 (2020).

Kim, W. J. et al. Clinicopathological features and Long-Term outcomes of intraductal papillary neoplasms of the intrahepatic bile duct. J. Gastrointest. Surg. 20, 1368–1375. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11605-016-3103-5 (2016).

You, Y. et al. Recurrence after resection for intraductal papillary neoplasm of bile duct (IPNB) according to tumor location. J. Gastrointest. Surg. 24, 804–812. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11605-019-04235-8 (2020).

Hanif, H. et al. Update on the applications and limitations of alpha-fetoprotein for hepatocellular carcinoma. World J. Gastroenterol. 28, 216–229. https://doi.org/10.3748/wjg.v28.i2.216 (2022).

Zhao, H. et al. Inflammation and tumor progression: signaling pathways and targeted intervention. Signal. Transduct. Target. Ther. 6, 263. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41392-021-00658-5 (2021).

Fan, J., Ning, B., Lyon, C. J. & Hu, T. Y. Circulating peptidome and Tumor-Resident proteolysis. Enzymes 42, 1–25. https://doi.org/10.1016/bs.enz.2017.08.001 (2017).

Li, L., Wu, J., Lyon, C. J., Jiang, L. & Hu, T. Y. Clinical peptidomics: advances in instrumentation, analyses, and applications. BME Front. 4, 0019. https://doi.org/10.34133/bmef.0019 (2023).

Ostrowitzki, S. et al. A phase III randomized trial of gantenerumab in prodromal alzheimer’s disease. Alzheimers Res. Ther. 9, 95. https://doi.org/10.1186/s13195-017-0318-y (2017).

Goetze, J. P. et al. Cardiac natriuretic peptides. Nat. Reviews Cardiol. 17, 698–717. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41569-020-0381-0 (2020).

Hilf, N. et al. Actively personalized vaccination trial for newly diagnosed glioblastoma. Nature 565, 240–245. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41586-018-0810-y (2019).

Sandanayake, N. S. et al. Identification of potential serum peptide biomarkers of biliary tract cancer using MALDI MS profiling. BMC Clin. Pathol. 14 https://doi.org/10.1186/1472-6890-14-7 (2014).

Park, H. G. et al. MALDI-TOF MS-based total serum protein fingerprinting for liver cancer diagnosis. Analyst 144, 2231–2238. https://doi.org/10.1039/c8an02241k (2019).

Kim, S. S. et al. Quantifiable peptide library bridges the gap for proteomics based biomarker discovery and validation on breast cancer. Sci. Rep. 13, 8991. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-023-36159-4 (2023).

Rungkamoltip, P., Roytrakul, S. & Navakanitworakul, R. MALDI-TOF MS analysis of serum peptidome patterns in cervical cancer. Biomedicines 11 https://doi.org/10.3390/biomedicines11082327 (2023).

Sun, J. et al. Evaluation of prostate cancer based on MALDI-TOF MS fingerprinting of nanoparticle-treated serum proteins/peptides. Talanta 220, 121331. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.talanta.2020.121331 (2020).

Ploypetch, S. et al. Utilizing MALDI-TOF MS and LC-MS/MS to access serum peptidome-based biomarkers in canine oral tumors. Sci. Rep. 12, 21641. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-022-26132-y (2022).

Lee, J. W. et al. Potential of MALDI-TOF-based serum N-glycan analysis for the diagnosis and surveillance of breast cancer. Sci. Rep. 10, 19136. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-020-76195-y (2020).

Kanda, M. et al. The combination of the serum carbohydrate antigen 19 – 9 and carcinoembryonic antigen is a simple and accurate predictor of mortality in pancreatic cancer patients. Surg. Today. 44, 1692–1701. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00595-013-0752-9 (2014).

Antonarakis, E. S. et al. The natural history of metastatic progression in men with prostate-specific antigen recurrence after radical prostatectomy: long-term follow-up. 109, 32–39 https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1464-410X.2011.10422.x (2012).

Chicco, D. & Jurman, G. The advantages of the Matthews correlation coefficient (MCC) over F1 score and accuracy in binary classification evaluation. BMC Genom. 21, 6. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12864-019-6413-7 (2020).

Gao, X. et al. A multiclass classification using one-versus-all approach with the differential partition sampling ensemble. Eng. Appl. Artif. Intell. 97, 104034. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.engappai.2020.104034 (2021).

Krebs, R., Bagui, S. S., Mink, D. & Bagui, S. C. Applying Multi-CLASS support vector machines: One-vs.-One vs. One-vs.-All on the UWF-ZeekDataFall22 dataset. 13, 3916 (2024).

Yang, Y. & Mirzaei, G. Performance analysis of data resampling on class imbalance and classification techniques on multi-omics data for cancer classification. PLoS One. 19, e0293607. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0293607 (2024).

Chaiyarit, P., Taweechaisupapong, S., Jaresitthikunchai, J., Phaonakrop, N. & Roytrakul, S. Comparative evaluation of 5-15-kDa salivary proteins from patients with different oral diseases by MALDI-TOF/TOF mass spectrometry. Clin. Oral Investig. 19, 729–737. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00784-014-1293-3 (2015).

Yigitbasi, T. et al. An efficient biomarker panel for diagnosis of breast cancer using surface-enhanced laser desorption ionization time-of-flight mass spectrometry. Biomed. Rep. 8, 269–274. https://doi.org/10.3892/br.2018.1042 (2018).

Thanasukarn, V. et al. Discovery of novel serum peptide biomarkers for cholangiocarcinoma recurrence through MALDI-TOF MS and LC-MS/MS peptidome analysis. Sci. Rep. 15, 2582. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-87124-2 (2025).

Swiatly, A. et al. MALDI-TOF-MS analysis in discovery and identification of serum proteomic patterns of ovarian cancer. BMC Cancer. 17, 472. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12885-017-3467-2 (2017).

Wu, S. et al. Identification of serum biomarkers for ovarian cancer using MALDI-TOF-MS combined with magnetic beads. Int. J. Clin. Oncol. 17, 89–95. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10147-011-0259-6 (2012).

Pais, R., Grigaite, R., Lacey, J., Jardine, C. & Iles, R. A. Rapid and affordable screening tool for Early-Stage ovarian cancer detection based on MALDI-ToF MS of blood serum. Appl. Sci. 12, 3030. https://doi.org/10.3390/app12063030 (2022).

Cortes, C. & Vapnik, V. Support-vector networks. Mach. Learn. 20, 273–297. https://doi.org/10.1007/BF00994018 (1995).

Pang, Z. et al. MetaboAnalyst 6.0: towards a unified platform for metabolomics data processing, analysis and interpretation. Nucleic Acids Res. 52, W398–w406. https://doi.org/10.1093/nar/gkae253 (2024).

Acknowledgements

All authors are truly thankful for helpful discussions with the late Prof. Narong Khuntikeo at Department of Surgery, Faculty of Medicine, Khon Kaen University, Khon Kaen, Thailand, Cholangiocarcinoma Research Institute (CARI), Khon Kaen University, Khon Kaen, Thailand and Cholangiocarcinoma Screening and Care Program (CASCAP), Khon Kaen University, Khon Kaen, Thailand. We are also indebted to all members of CASCAP, particularly the cohort members, and researchers at CARI, Faculty of Medicine, Khon Kaen University for collecting and proofing of CCA patient data. We also acknowledge Professor Ross H. Andrews for editing the MS.

Funding

This work was Supported by Research Program from Research Department of Khon Kaen University and the National Research Council of Thailand through the Hub of Knowledge Grant to WL.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

Conceptualization—P.P., A.T., V.T., and W.L.; Methodology—P.P., A.T., V.T., A.J., N.K., K.R., N.N., P.K., A.W., J.C., S.K., P.S., N.M. and W.L.; Formal analysis—P.P., A.T., V.T. and W.L.; Investigation—P.P., A.T., V.T., N.M., S.C., J.J. and W.L.; Resources—A.T., S.R. and W.L.; Data curation—P.P., A.T., V.T. and W.L; Visualization—P.P., V.T. and N.M.; Supervision—A.T., S.R. and W.L.; Project administration—W.L.; Funding acquisition—W.L.; Original draft preparation—P.P.; Draft review and editing—all authors.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher’s note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Supplementary Information

Below is the link to the electronic supplementary material.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if you modified the licensed material. You do not have permission under this licence to share adapted material derived from this article or parts of it. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Prajumwongs, P., Titapun, A., Thanasukarn, V. et al. Serum peptide biomarkers by MALDI-TOF MS coupled with machine learning for diagnosis and classification of hepato-pancreato-biliary cancers. Sci Rep 15, 29169 (2025). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-14451-9

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-14451-9