Abstract

Physical activity appears to be a strong determinant of the building of peak bone mass and the degree of bone mineralization in young adult males. This study aimed to describe the impact of volleyball (V), throwing athletes (TA), climbing (CL), snowboarding participation (SN), fracture history, hand grip strength (HGS), and body composition on forearm bone mineral density (BMD) in males. BMD, bone mass content (BMC), and T-score of the distal (dis) and proximal (prox) parts of the forearm were measured by the DXA technique. The CL and TA groups showed the highest BMD, BMC, and T-score dis and prox. In the TA group, a higher prevalence of normal BMD was found in the distal part of the forearm compared to V (by 6.7%), CL (by 15.4%), and SN (by 35.7%). In the CL group a higher prevalence of normal BMD was found in the proximal part of the forearm compared to V (by 12.4%), TA (by 6.8%), and SN (by 34.6%). The highest prevalence of low bone density was observed in the SN group. Covariance analysis revealed that body height and the type of sports competition significantly affected BMD in the distal region (adj. R2 = 0.77). For BMD in the proximal region, the significant factor was sports competition (adj. R2 = 0.73). In both the distal and proximal regions of the BMC, the significant factors were handgrip strength (HGS) in newtons (N) and the type of sports competition (distal adj. R2 = 0.60; proximal adj. R2 = 0.85). Similar results were obtained for the T-score dis. The T-score prox was significantly affected only by HGS (N) (adj. R2 = 0.59). Training based on throwing and weight-bearing exercises influences higher forearm BMD. The results of the study also highlight the important role of information about past fractures, which may serve as an initial indicator of risk groups for low bone density.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Bone mineral density (BMD) is crucial for bone health, especially in professional sports where athletes experience high levels of physical stress. Physical activity appears to be a strong determinant of both the building of peak bone mass and the degree of bone mineralization in young adult males1. Studies conducted in men demonstrate the effect of sports training on BMD, especially with a high osteogenic index (OI)2. An OI has been used to predict the osteogenic potential of exercise3. The exercise based on well-chosen intensity, frequency, and duration of loading may maximize osteogenic responses in bone. However, researchers indicate that a model of the osteogenic potential of exercise for bone parameters has not yet been established4. Many new training solutions and methods of supporting the training process are emerging in professional sports5,6. Still, there is little research that addresses the issue of supporting the skeletal system of athletes.

It is well known that participation in certain sports activities is positively correlated with BMD and bone mass. The response of bones to mechanical stimuli is particularly dependent on the nature of these stimuli. Sports that subject the skeleton to high forces at high loading rates bring the greatest benefits. Among the sports considered to be the most osteogenic are gymnastics, volleyball, and football. In contrast, cycling and swimming have the least osteogenic effect7,8. An extensive meta-analysis found that swimming has no effect on the increase of BMD and is the same as in the control group, not training9.

Low bone mass poses a particular challenge for athletes because it predisposes them to stress-related bone injuries and increases the risk of osteoporosis and insufficiency fractures with aging10.

A study of over 50 young male runners found that the risk of low BMD showed a graded relationship with increasing risk factors, underscoring the importance of using bone mass optimization methods in sports11. In a study by Tenforde et al. involving nearly 30 athletes from various sports, low BMD was found in 43% of the male athletes included in the study. Athletes who practiced running and had a history of BSI had an increased risk of developing low BMD12.

A significant factor influencing BMD is the load generated by muscle contractions, which affects the local regulation of BMD near the entheses. These mechanisms help explain the high BMD in strength athletes and the regional strengthening of bones, such as strong forearm bones in tennis13. However, there is insufficient evidence regarding the intensity and duration of exercise required for this osteogenic stimulation to occur14. This is the main reason why not all physical activities have the same effect on bones.

In addition to physical activity, bone parameters are influenced by several other factors. Among them are somatic characteristics, body structure, and body composition. There is no clear opinion on which anthropometric measurement is more associated with low BMD15. In the adult population, BMD often shows a stronger correlation with body mass index (BMI) and lean body mass and a much weaker correlation with body fat mass16,17. Some studies of healthy young adults have shown that high body fat levels have no significant relationship with BMD18.

Therefore, in addition to bone parameters, we included anthropometric and body composition measurements, such as body weight, BMI, percentage of body fat, hand grip strength, and number of fractures. This study aimed to describe the impact of participation in volleyball (V), throwing sports (TA: hammer throw, discus, shot put, javelin throw), climbing (CL), and snowboarding (SN), as well as fracture history, hand grip strength, and body tissue composition, on forearm bone mineral density (BMD) in high-level male Polish athletes.

We also posed a research hypothesis that training seniority in disciplines with different osteogenic indexes would affect the degree of bone mineralization, and it is necessary to verify the direction of these interactions. Fracture history was analyzed in terms of both the type of fracture (traumatic, stress fracture) and the total number of fractures sustained over a lifetime, and its association with forearm BMD was assessed.

Methods

Participants

The study included 54 male Polish athletes aged 22.3 ± 2.2 years (aged between 19.0 and 29.9 years) from four sports competitions: volleyball (V), throwing athletes: hammer throw, discus, shot put, javelin throw (TA), climbing (CL), and snowboarding (SN). The criterion for selecting these sports for the study is the wide variation in the specific loads and types of exercises performed. These criteria provide an opportunity to study athletes from different sports for their osteogenic effects on bone. The study analyzed the Polish and European Championships medallists in these four sports competitions. The training experience in professional sports of the surveyed athletes was 9.6 ± 2.1 years. All participants were of the same ethnic origin (Caucasian). Data was collected prospectively. Inclusion criteria were as follows: written consent to participate in the study and the lack of health contraindications to densitometry. The exclusion criteria: kidney disease, cancers, rheumatoid arthritis, rickets in childhood age, bone diseases, nutritional disorders, and long-term steroid treatment. All participants were informed about the aims and schedule of the study and received their test results along with an interpretation.

The survey was conducted as part of a major project, the Scientific Working Group 2024–2026: “Determinants of Bone Mineral Density in Different Sports.” The studies were approved by the Bioethics Committee of the National Institute of Public Health—National Institute of Hygiene in Warsaw, Poland (protocol number 1/2021). The study was conducted according to the rules and regulations of the Declaration of Helsinki. The studies were conducted according to the local legislation and institutional requirements. The participants provided their written informed consent to participate in this study.

Measures

Methods for assessing bone tissue and the history of fractures

Bone mineral density (BMD in g/cm2), bone mass content (BMC in g), and T-score of the forearm were measured once by the dual X-ray absorptiometry. In this study, we consistently applied daily calibration procedures and quality control measures for pDXA. A Norland (Swissray-USA, Norland Medical Systems Madison WI, USA) densitometer was used, with the effective dose (μSv) of 0.05. We reported results as T-score (the indicator that compares bone density of the individual with the mean of the population of healthy young people) and Z-score (the indicator that compares bone density with the average for people of the same age, sex, and body size). According to the Adult Official Positions of the ISCD as updated in 2023, a Z-score of − 2.0 or lower is defined as below the expected range for age, and a Z-score above − 2.0 is within the expected range for age. The densitometer was calibrated by means of the original phantoms recommended by the manufacturer. Measurements were made on the nondominant arm with the subject in the sitting position, sideways to the densitometer. According to the methodology of forearm measurement by densitometry, two regions were measured: the distal site (radius + ulna) and the general 1/3 proximal site (radius + ulna). Regression statistics were reported for all similar areas of interest (ROIs)20,21. During the face-to-face interview, data were collected on fracture history and the number of fractures in a lifetime.

Methods for assessing somatic variables and body composition

Basic somatic measurements were carried out according to the standards proposed by the International Society for the Advancement of Kinanthropometry (ISAK)22. Body height was measured using Seca 264, Seca GmbH & co. kg, Germany with a precision of 0.1 cm, as were standing reach measurements (Seca 216, Seca GmbH & co. kg, Germany). Seca model 264 stadiometers with Seca 360° wireless technology, equipped with a heel positioner and Frankfurt plane positioner for head positioning. The measurement was taken in the morning, without shoes. Body mass (kg) and body composition such as fat mass (in kg- FM and in %—PBF), and fat-free mass (FFM in kg) were measured using the bioelectrical impedance method. The X-SCAN PLUS II Medical Body Composition Analyzer was used (Certificate No. EC0197 for medical devices).

Assessment methods–hand grip strength

Hand grip strength (HGS) was measured in this study using a dynamometer. The JAMAR® Hydraulic Hand Dynamometer (Model J00105, Lafayette Instrument Company, USA), which is well validated and considered the gold standard for hand grip assessment, was used. The measurement was taken from the non-dominant hand. Three consecutive trials were performed, and the mean value was calculated and recorded to the nearest 0.1 Newton (N)23.

Statistical analysis

All calculations were performed using STATISTICA software (v.13.3, StatSoft, USA). The normality of distribution was verified by the Shapiro–Wilk test. The assumption of the equality of variance was verified using the Levene test. The reliability coefficient for the measurements was Cronbach’s α = 0.91. The analysis of variance (ANOVA) was employed to show significant differences between the four male athlete groups (volleyball, throwing athletes, climbing, and snowboarding). Bonferroni’s post hoc test was used for intergroup comparison. Effect size was calculated as eta-squared (η2) (small effect < 0.06; medium effect 0.06–0.14; large effect > 0.14)24. The chi-squared test (χ2) was used to assess the differences in the frequency of occurrence of normal and low BMD and also fracture status in four male athlete groups according to the sport type. To determine the effect size for the chi-squared test, the phi factor (Φ) was used (small effect: 0.1; medium effect: 0.3; large effect: 0.5). To find relationships between bone parameters and somatic, body compositions, strength, training experience, and type of sports competition (as qualitative predictor) in all athletes, the ANCOVA was applied. The degree of correlation of the predictors was assessed using the variance inflation factor (VIF) collinearity test, taking a not-to-exceed value of 10. Residual analysis was also performed, testing for homoscedasticity using the White test and the degree of correlation of the residuals using the Durbin-Watson test. Two-way ANOVA analysis was applied to determine the relationships of mean T-score, sport type (volleyball, throwing athletes, climbing, and snowboarding), and fractures status (yes vs. no fractures during life), and also the number of fractures during life (no fractures vs. one vs. two and more). The statistical significance level was set at *p < 0.05, **p < 0.01, ***p < 0.001.

Results

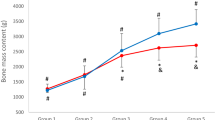

The basic characteristics of the four groups of male athletes: volleyball (V), throwing athletes (TA), climbing (CL), and snowboard (SN), including somatic features, body composition, training experience, hand grip strength, bone parameters, and the significance of differences, are presented in Table 1. The groups differed significantly (p < 0.05) in 13 of the 17 analyzed parameters. Of the 8 bone parameters, separately for the distal (dis) and proximal (prox) forearm, the groups differs in 5 parameters. The CL and TA groups observed the highest BMD, BMC, T-score and Z-score dis and prox. Significant differences were shown in BMC dis between men from different sports. The highest BMC dis was shown in the CL (F = 14.86; η2 = 0.56; large effect). Also significant differences were shown in BMC prox between men from different sport disciplines, where the highest BMC was shown in the TA (F = 29.13; η2 = 0.79; large effect). The next significant differences were shown in T-Score prox (F = 13.59; η2 = 0.75; large effect), where the highest this variable was shown in the TA. Also significant differences were shown in BMD prox (F = 13.21; η2 = 0.75; large effect) where the highest BMD prox was shown in the TA. Significant differences were shown in Z-score prox (F = 13.39; η2 = 0.71; large effect) where the highest was shown in the TA. Significant differences were found in the number of fractures. SN had significantly more fractures in their lifetime compared to the other groups of athletes (F = 4.40; η2 = 0.54; large effect), (insert Table 1 here).

Table 2 shows the prevalence of normal and low bone mineralization, within the expected range for age and below the expected range for age, and also the status of fractures in male athletes’ groups. In the TA group, more frequent (χ2 = 4.91; Φ = 0.30; medium effect) normal BMD was found in the distal part of the forearm compared to V (by 6.7%), CL (by 15.4%) and SN (by 35.7%). In the CL group, more frequent (χ2 = 4.32; Φ = 0.28; small effect) normal BMD was found in the proximal part of the forearm compared to V (by 12.4%), TA (by 6.8%) and SN (by 34.6%). The SN group had the highest prevalence of low bone density in both the distal and proximal forearms. A significantly higher prevalence of fractures was shown in SN compared to other groups of athletes (χ2 = 14.77; Φ = 0.52; large effect), (insert Table 2 here).

The relationships of the characteristics studied (somatic, body composition, hand grip strength, training experience, and type of sports competition) with individual parameters of bone mineralization status (BMD, BMC, T-score, Z-score) separately for dis, and prox segments in all athletes are presented in Table 3 (ANCOVA results). Covariance analysis indicated that the main indicators significantly affecting BMD dis were two variables: body height (cm) and type of sports competition (adj. R2 = 0.77). In turn, in BMD prox the main indicator significantly affecting was the type of sports competition (adj. R2 = 0.73). The main indicators significantly affecting BMC in the dis and prox segments of the forearm were two variables: HGS (N) and type of sports competition (in dis adj. R2 = 0.60 and in prox adj. R2 = 0.85). Similar results were obtained for T-score dis and Z-score dis, the main indicators significantly affecting were HGS (N) and type of sports competition (adj. R2 = 0.42 and 0.40). T-score prox and Z-score prox were significantly affected only by HGS (N), (adj. R2 = 0.59 and 0.58), (insert Table 3 here).

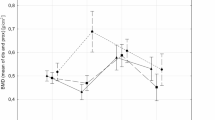

Figure 1 shows relationships of mean T-score (the arithmetic mean from two sections of the distal and proximal forearm), type of sport, and fractures during life status (two-way ANOVA results). In all groups, men without fractures in life had the most advantageous values of the forearm mean.

T-score compared to men after fractures in life (F = 3.0185, p = 0.04). Figure 2 shows the relationships of mean T-score, type of sport, and the number of fractures during life. Among all groups of athletes, the lowest T-score values were shown in men who had suffered two or more bone fractures in their lifetime (insert Figs. 1 and 2 here). Analogous analyses were conducted for the Z-score. A similar pattern of interaction was obtained as in the case of the T-score. The lowest Z-score values were shown in all groups of men who had fractures, and especially two or more fractures in their lifetime (insert Figs. 3 and 4 here).

Discussion

Muscle strength and bone mineral density are key determinants of athlete health, especially in disciplines associated with a high risk of injury and falls, such as those involving frequent impacts or potential for fractures. However, studies among athletes of sports with different osteogenic index (OI) are not numerous and often show inconclusive results.

This cross-sectional study assessed the degree of mineralization in men from 4 different sports, including winter sports. The specifics of training in these disciplines are heavily based on various upper limb and forearm exercises such as ball strikes and receptions, climbing grip, and throwing. In snowboarding, the upper limbs play a crucial role in supporting the body on the slope. However, this leads to a high risk of injury during falls, as the entire body weight may be placed on the wrists and forearms25.

Our finding of a correlation between lifetime fracture prevalence and bone T-score is consistent with previous research. Earlier studies have shown that total and regional BMD values were lower in distance runners before their first lower extremity fracture compared to athletes without injuries, indicating that low bone parameters are an intrinsic risk factor for fractures26. In the present study, it was found that among the representatives of four sports disciplines, the highest values of forearm BMD (dis and prox), BMC (dis and prox), T-score and Z-score (dis and prox) were observed in athletes participating in climbing and throwing sports, compared to volleyball players and snowboarders. In another cross-sectional study, differences in BMD were observed among male athletes from various sports disciplines, with the highest BMD values found in those participating in strength and team sports compared to cyclists, triathletes, runners, academic athletes, and a non-athlete control group27.

Considering the training load, athletes involved in climbing, throwing, and volleyball exert significantly greater pressure on the upper limbs compared to snowboarders, which is reflected in specific bone parameters. The results of this study suggest a positive effect of training on bone metabolism through loading caused by muscle contractions, leading to local adaptations28,29,30.

This study also analyzed the prevalence of reduced bone density (T-score) and BMD below the expected range for age (Z-score) in the distal and proximal segments. The study shows that the reduced bone density in the distal part of the forearm was in 35.7% of the SN group, 16.7% in the V group, and 15.4% in the CL group. In the proximal part of the forearm, the reduced bone density was in 50% of the SN group, 27.8% in the V group, 15.4% in the CL, and 22.2% in the TA. BMD below the expected range for age (Z-score) was only in the proximal segments of the forearm and only in the V group.

The frequency of normative T-score in the distal and proximal segments of the forearm varies between athletes with different specificities of mechanical loading has been studied. Studies show that athletes who specialize in sports that uniquely load the forearm (such as throwing) achieve the highest bone density in this area. In an analysis of Masters athletes, it was throwing athletes who had the highest forearm BMD values regardless of gender. This confirms that intense unilateral or local mechanical loading stimulates an increase in BMD in specific areas of the bone, as observed by the 100% T-score norm in the throwing group31.

A concerning finding is the low T-score in snowboarders, for whom the wrist and forearm are particularly often used as support during falls in this specific sport. Studies confirm that wrist fractures are the most common injury among snowboarders. They constitute from 17 to 28% of all injuries32. Interestingly, the highest percentage of wrist and forearm injuries also occurs among competitive snowboarding athletes33.

Low bone mineral density can have important implications for an athlete’s health and performance and influences the risk of bone fracture in competitive sports34. Low BMD, a risk factor for fractures, is a significant concern in professional sports, particularly among endurance athletes. Prolonged periods of low energy availability (LEA) in athletes are a major contributor to low BMD, leading to a condition called relative energy deficiency in sports (RED-S). Among the key mechanisms for the effect of RED-S on bone tissue are decreases in estrogen in women and testosterone in men. Abnormally low levels of these hormones can lead to decreased osteoblast activity and increased bone resorption. In addition, in RED-S, there is often impaired calcium and vitamin D metabolism, and this impairs bone mineralization. This can affect performance, increase injury risk, and lead to long-term health problems. Endurance athletes expend large amounts of energy during prolonged high-intensity exercise. Most endurance athletes often practice periods of dietary restriction to maintain a suitable light body shape. Several studies have analyzed the effects of low energy availability on various bone structure parameters. However, there are differences in findings and research methods, and critical summaries are lacking. Athletes find it difficult to reduce energy expenditure or increase energy intake to restore energy availability when training performance is a priority35. This is why DXA screening should be considered among athletes who are particularly susceptible to RED-S and injury.

In this study, factors that most clearly influenced bone parameters in athletes were the type of discipline practiced and hand grip strength. BMD is dependent on the specific mechanical demands of different sports. Many studies have shown that external or device-loaded exercises and high-impact sports are associated with higher BMD levels compared to inactive control groups36. Resistance training and impact-loading activities are effective at increasing or maintaining bone mass37.

An explanation for these results can be given by analyzing the specific loads of a given sport: block throwing sports such as discus, javelin, hammer throw involve large centrifugal forces transmitted by intensive muscle pulling on bone. The specificity of climbing primarily includes a strong isometric grip and frequent jumping into depth during training. Skeletal loads are caused by repeated falls to the ground. Intermittent isometric contractions of the forearms occur at the moment of grip. However, climbing also involves dynamic and static movements of the whole body, with some contractions approaching maximum intensity 38. Climbing exercises, including rock climbing and stair climbing, increase bone mineral density. Primarily by the application of mechanical stress on bones. This stress stimulates osteoblasts (bone-forming cells) and inhibits osteoclasts (bone-resorbing cells), leading to increased bone formation and reduced bone resorption. Additionally, climbing promotes changes in bone morphology, such as cortical hypertrophy, and can alter bone marrow stromal cell activity39.

Movements specific to volleyball, such as dynamic ball strikes, jumps, sprints, and quick stops, also cause high-speed and impact loads. In snowboarding, high isometric work occurs in the lower limbs, but it is the upper limbs that often absorb falls, which can also potentially be an osteogenic factor. To include a variable describing upper limb strength in the analysis, this study also evaluated hand grip strength (HGS) on a dynamometer. Covariance analysis indicated that the main indicators significantly affecting BMC in the dis and prox segments of the forearm were two variables: HGS and type of sports competition. Similar results were obtained for T-score dis, the main indicators significantly affecting were HGS and the type of sports competition. T-score prox was significantly affected only by HGS. The results of this study are consistent with those of other authors analyzing the correlation of HGS with BMD. Chan et al. (2008) showed, in a gradual regression, that HGS was a strong predictor variable for BMD in both sexes. Prediction models according to grip strength and body mass accounted for 60% and 40% of changes in BMC of various parts and BMD of the hip joint and the spine40.

Nasri et al. investigated the correlation between bone parameters and HGS in among adolescent combat sport athletes aged 17.1 ± 0.2 years. In this study, the HGS in the dominant hand was significantly correlated with BMD of both the spine and legs. However, the best predictor of BMD measurements is HGS in the nondominant hand. This study has shown the osteogenic effect of combat sports practice, especially judo and karate Kyokushin Ai. Moreover, Nasri et al. suggested that the best model predicting BMD in different sites among adolescent combat sports athletes was the HGS in the non-dominant hand41.

This study has several limitations that should be noted. First, the relatively small number of athletes and only one winter sports discipline. The study included several variables, but in future projects, it is worth expanding to include variables such as nutrition and supplementation. One of the limitations of this study—and a strong argument for continuing and expanding the research project was the lack of information on energy availability, calcium and vitamin D intake, hormonal status of the athletes, and detailed training volume. These may be confounding factors that could help explain differences between sports disciplines. Therefore, it is worth including them in future research. The multifactorial nature of BMD influences the need for further studies involving a larger group of athletes, preferably at different stages of their sports careers. In future studies, it would be worth looking more closely at the interactions of fracture history with BMD. For example, the location of the fracture and the period of ontogeny in which the fracture was suffered may be important.

Conclusion

This study has shown that athletes, especially those who participate in throwing sports and engage in isometric holding tensions, exhibit higher BMD. These results suggest that the type of sports activity may be an important factor in achieving a high peak bone mass and good mineralization of the forearm bones. The results of this study suggest that it is worth considering incorporating throwing and isometric exercises into other disciplines. It is worth considering whether screening for bone mineral status should be included in sports diagnostics. The results of the study also point to the important role of information about past fractures during life, which can initially indicate of low bone density risk groups.

Data availability

Data availability The datasets generated during and/or analysed during the current study are available from the corresponding author upon reasonable request.

References

Ferry, B., Lespessailles, E., Rochcongar, P., Duclos, M. & Courteix, D. Bone health during late adolescence: Effects of an 8-month training program on bone geometry in female athletes. Jt. Bone Spine 80(1), 57–63 (2013).

Simões, D. et al. The effect of impact exercise on bone mineral density: A longitudinal study on non-athlete adolescents. Bone 153, 116151 (2021).

Savikangas, T., Sipilä, S. & Rantalainen, T. Associations of physical activity intensities, impact intensities and osteogenic index with proximal femur bone traits among sedentary older adults. Bone 143, 115704 (2021).

Lester, M. E. et al. Influence of exercise mode and osteogenic index on bone biomarker responses during short-term physical training. Bone 45(4), 768–776 (2009).

Adamczyk, J. G. Support your recovery needs (SYRN) – a systemic approach to improve sport performance. Biomed. Hum. Kinet. 15(1), 269–279 (2023).

Boguszewski, D., Krawczyk, A., Dębek, M. & Adamczyk, J. G. The effects of foam rolling applied to delayed-onset muscle soreness of the quadriceps femoris after Tabata training. Biomed. Hum. Kinet. 16, 203–209 (2022).

Bellver, M., Del Rio, L., Jovell, E., Drobnic, F. & Trilla, A. Bone mineral density and bone mineral content among female elite athletes. Bone 127, 393–400 (2019).

Klomsten, et al. Bone health in elite Norwegian endurance cyclists and runners: a cross-sectional study. BMJ Open Sport Exerc. Med. 4(1), e000449 (2018).

Gomez-Bruton, A. et al. Swimming and peak bone mineral density: A systematic review and meta-analysis. J. Sports Sci. 36(4), 365–377 (2018).

Herbert, A. J. et al. The interactions of physical activity, exercise and genetics and their associations with bone mineral density: Implications for injury risk in elite athletes. Eur. J. Appl. Physiol. 119(1), 29–47 (2019).

Barrack, M. T., Fredericson, M., Tenforde, A. S. & Nattiv, A. Evidence of a cumulative effect for risk factors predicting low bone mass among male adolescent athletes. Br. J. Sports Med. 51(3), 200–205 (2017).

Tenforde, A. S., Parziale, A. L., Popp, K. L. & Ackerman, K. E. Low bone mineral density in male athletes is associated with bone stress injuries at anatomic sites with greater trabecular composition. Am. J. Sports Med. 46(1), 30–36 (2018).

Carter, M. I. & Hinton, P. S. Physical activity and bone health. Mo Med. 111(1), 59–64 (2014).

Kopiczko, A., Adamczyk, J. G. & Łopuszańska-Dawid, M. Bone mineral density in adolescent boys: Cross-sectional observational study. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 18(1), 245 (2020).

Kim, H. Y. et al. The role of overweight and obesity on bone health in korean adolescents with a focus on lean and fat mass. J. Korean Med. Sci. 32(10), 1633–1641 (2017).

Murat, S., Dogruoz, Karatekin, B., Demirdag, F. & Kolbasi, E. N. Anthropometric and body composition measurements related to osteoporosis in geriatric population. Medeni. Med. J. 36(4), 294–301 (2021).

Chiu, C. T. et al. The association between body mass index and osteoporosis in a Taiwanese population: A cross-sectional and longitudinal study. Sci. Rep. 14(1), 8509 (2024).

Pomeroy, E., Macintosh, A., Wells, J. C. K., Cole, T. J. & Stock, J. T. Relationship between body mass, lean mass, fat mass, and limb bone cross-sectional geometry: Implications for estimating body mass and physique from the skeleton. Am. J. Phys. Anthropol. 166(1), 56–69 (2018).

Kerkadi, A. et al. The relationship between bone mineral density and body composition among qatari women with high rate of obesity: Qatar biobank data. Front Nutr. 9, 834007 (2022).

Kopiczko, A., Gryko, K. & Łopuszańska-Dawid, M. Bone mineral density, hand grip strength, smoking status and physical activity in Polish young men. Homo 69(4), 209–216 (2018).

Norland Medical Systems pDEXA Owner’s Manual. Norland Medical Systems, Madison WI, USA, pp. viii.

Marfell-Jones, M. J., Stewart, A. D. & De Ridder, J. H. International standards for anthropometric assessment. Wellington, New Zealand: International Society for the Advancement of Kinanthropometry (2012)

Lee, S. C. et al. Validating the capability for measuring age-related changes in grip-force strength using a digital hand-held dynamometer in healthy young and elderly adults. Biomed. Res. Int. 2020, 6936879 (2022).

Grissom, R. J. & Kim, J. J. Effect Sizes for Research: Univariate and Multivariate Applications 2nd edn. (Routledge, 2012).

Gao, F. et al. Epidemiology of injuries among snowboarding athletes in the talent transfer program: A prospective cohort study of 39,880 athlete-exposures. PLoS ONE 19(7), e0306787 (2024).

Carbuhn, A. F., Yu, D., Magee, L. M., McCulloch, P. C. & Lambert, B. S. Anthropometric factors associated with bone stress injuries in collegiate distance runners: New risk metrics and screening tools?. Orthop. J. Sports Med. 10(2), 23259671211070308 (2022).

Hinrichs, T., Chae, E., Lehmann, R., Allolio, B. & Platen, P. Bone mineral density in athletes of different disciplines: A cross- sectional study. Open Sports Sci J. 3, 129–133 (2010).

Asakawa, D. & Sakamoto, M. Characteristics of counter-movements in sport climbing: A comparison between experienced climbers and beginners. J. Phys. Ther. Sci. 31(4), 349–353 (2019).

Vernillo, G., Pisoni, C. & Thiébat, G. Physiological and physical profile of snowboarding: A preliminary review. Front. Physiol. 9, 770 (2018).

Sheppard, J. M., Gabbett, T. J. & Stanganelli, L. C. An analysis of playing positions in elite men’s volleyball: Considerations for competition demands and physiologic characteristics. J. Strength. Cond. Res. 23(6), 1858–1866 (2009).

Kopiczko, A., Adamczyk, J. G., Gryko, K. & Popowczak, M. Bone mineral density in elite masters athletes: The effect of body composition and long-term exercise. Eur. Rev. Aging Phys. Act. 18(1), 7 (2021).

Quinlan, N. J., Patton, C. M., Johnson, R. J., Beynnon, B. D. & Shafritz, A. B. Wrist fractures in skiers and snowboarders: Incidence, severity, and risk factors over 40 seasons. J. Hand. Surg. Am. 45(11), 1037–1046 (2020).

Ehrnthaller, C., Kusche, H. & Gebhard, F. Differences in injury distribution in professional and recreational snowboarding. Open Access J. Sports Med. 6, 109–119 (2015).

Goolsby, M. A. & Boniquit, N. Bone health in athletes. Sports Health 9(2), 108–117 (2016).

Hutson, M. J., O’Donnell, E., Brooke-Wavell, K., Sale, C. & Blagrove, R. C. Effects of low energy availability on bone health in endurance athletes and high-impact exercise as A potential countermeasure: A narrative review. Sports Med. 51(3), 391–403 (2021).

Kopiczko, A. Factors affecting bone mineral density in young athletes of different disciplines: A cross-sectional study. Arch Budo Sci Martial Arts Extreme Sports. 19 (2023).

Hong, A. R. & Kim, S. W. Effects of resistance exercise on bone health. Endocrinol. Metab. 33(4), 435–444 (2018).

Sherk, V. D., Bemben, M. G. & Bemben, D. A. Comparisons of bone mineral density and bone quality in adult rock climbers, resistance-trained men, and untrained men. J. Strength. Cond. Res. 24(9), 2468–2474 (2010).

Mori, T. et al. Climbing exercise increases bone mass and trabecular bone turnover through transient regulation of marrow osteogenic and osteoclastogenic potentials in mice. J. Bone Miner Res. 18(11), 2002–2009 (2003).

Chan, D. C. et al. Relationship between grip strength and bone mineral density in healthy Hong Kong adolescents. Osteoporos Int. 19(10), 1485–1495 (2008).

Nasri, R. et al. Grip strength is a predictor of bone mineral density among adolescent combat sport athletes. J. Clin. Densitom. 16(1), 92–97 (2013).

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

J.B and A.K. conceptualized and supervised the study. A.K. methodology and research organization. J.B. statistical analysis. J.B and A.K formal analysis investigation. J.B. and A.K. data curation J.B writing original draft preparation all authors read and approved the final manuscript.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher’s note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if you modified the licensed material. You do not have permission under this licence to share adapted material derived from this article or parts of it. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Bałdyka, J., Kopiczko, A. Determinants of forearm bone mineral density in male athletes with different osteogenic index of training. Sci Rep 15, 32097 (2025). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-14474-2

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-14474-2