Abstract

The vaginal microbiota plays a critical role in maintaining reproductive health. Although Lactobacillus species often dominate the vaginal environment in healthy individuals, recent studies have shown that healthy microbiota compositions can also include Lactobacillus-depleted states, as described by the Community State Types (CSTs) framework. However, disruptions in the microbiota composition, such as those caused by sexually transmitted infections (STIs), can lead to increased diversity and instability, compromising host protection. This study investigates the association between vaginal microbiota composition and the prevalence of STIs in a cohort of incarcerated women in Chile. Using metataxonomic approaches targeting 16S and 18S rRNA genes, we characterized prokaryotic and eukaryotic components of the vaginal microbiota across healthy, dysbiotic, and pathogen-dominated subjects. Alpha diversity analysis using the Shannon index indicated that Lactobacillus-dominant communities were associated with lower microbial diversity correlates with reduced variability. Whereas communities dominated by pathogens including Trichomonas vaginalis, Gardnerella vaginalis, Treponema pallidum, and HIV, tended to exhibit higher diversity. The pathogen-dominated group displayed an increased prevalence of opportunistic microorganisms and reduced Lactobacillus abundance, which may reflect an imbalance in the microbial ecosystem, often interpreted as reduced stability. This study provides novel insights into the intricate dynamics between normal and altered vaginal microbiomes and their association with STIs. Understanding these community-level patterns and associations is crucial for designing targeted interventions aimed at restoring microbial balance and preventing infections.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

The human microbiota comprises a diverse array of microorganisms that reside within the human body. It is fundamental to maintaining overall health and ensuring the proper functioning of the human body. In addition to aiding in digestion and vitamin synthesis, the microbiota also plays an important role in protecting the host against pathogens and regulating the immune system1,2. Thus, maintaining balanced microbiota is essential for general health and well-being3,4. Studies of human cohorts have shown that the composition of the microbiota varies significantly between individuals and is influenced by factors such as diet, lifestyle, environment, medication use and the underlying health conditions5. These variations can have profound effects on health, as alterations in the microbiota composition have been linked to metabolic and psychiatric disorders, immune system dysfunctions, and gastrointestinal diseases6,7. Given the complexity of microbial communities across body sites and individuals, microbiome studies require specialized approaches. Metataxonomy is a widely used approach for characterizing the composition and structure (i.e., relative abundance and diversity) of microbial communities in a given sample8.

Comparatively, the vaginal microbiota has been less extensively studied than other body sites, yet its composition plays a critical role in reproductive health. In healthy premenopausal women (of European descent), it is predominantly composed of bacteria of the Lactobacillus genus, which protect against pathogens by producing antimicrobial compounds that prevent the multiplication of pathogenic microorganisms and secreting biosurfactants that inhibit bacterial adhesion, preventing the formation of biofilms9,10.

Depending on the dominant bacterial species, the vaginal microbiota falls into one of five categories: Type I A and B, dominated by Lactobacillus crispatus; Type II, Lactobacillus gasseri predominates; Type III A and B, dominated by Lactobacillus iners; Type IV-A, IV-B y IV-C, characterized by a lower abundance of Lactobacillus, in detail; CST IV-A Candidatus Lachnocurva vaginae abundance, IV-B Gardnerella vaginalis abundance, CST IV-C into 5 sub-CSTs; Prevotella, Streptococcus, Enterococcus, Bifidobacterium, Staphylococcus dominated respectively and finally Type V, dominated by Lactobacillus. Jensenii11. These distinct microbial profiles influence vaginal health, with some fostering resilience against infections while others predispose individuals to dysbiosis, inflammation, and increased susceptibility to sexually transmitted infections (STIs)12.

While culture techniques have facilitated the isolation and characterization of many of these bacterial species, molecular approaches have revealed a far more diverse vaginal ecosystem, comprising over 581 bacteria species distributed across 206 genera and 96 different families13, many of which remain nonculturable or difficult to identify14,15,16. Their influence and health and disease are mostly unknown, underscoring the need for further research into their functional significance.

The vaginal microbiota undergoes dynamic changes due to physiological factors such as the menstrual cycle17, sexual habits18 and pathological conditions including bacterial vaginosis (BV)1,19,20, candidiasis and other STIs20,21. For instance, several studies have reported a correlation between human immunodeficiency virus (HIV) infection—highly incident in certain regions22,23—and increased bacterial diversity accompanied by a decline in Lactobacillus species within the vaginal microbiota23,24. More concerningly, changes in the vaginal microbiota composition can affect the incidence of STIs. For example, vaginal dysbiosis has been linked to an increased risk of STIs22,23. According to the World Health Organization (WHO) key pathogens of interest include Trichomonas vaginalis, Chlamydia trachomatis, Neisseria gonorrhoeae, and Treponema pallidum the causative agents of trichomoniasis, chlamydia, gonorrhea and syphilis, respectively25,26. While correlations between STIs and vaginal dysbiosis are well-documented, the underlying mechanisms by which these pathogens alter microbial communities remain poorly understood27.

The complex interplay between a stable and dysbiotic vaginal microbiome has yet to be fully elucidated. To move toward understanding potential causal relationships, it is essential to examine the relationship between pathogen emergence, sexual habits, alterations in the broader vaginal microbiota and their implications for women’s health. This study aims to bridge existing knowledge gaps by investigating the vaginal microbiota composition of incarcerated women in Chile. By analyzing microbial diversity in individuals with various infectious conditions and risk factors, we seek to uncover patterns that may inform targeted interventions for STI prevention and microbiota restoration.

Materials and methods

Study design

Samples from 124 women, obtained between March and June 2019, were analyzed as part of an earlier study28. Participation was voluntary, and all participants signed an informed consent before attending the Centro de Detención Preventiva de Arica y Parinacota (CDPA) Health Center. Informed consent was obtained from all the participants prior to enrollment. Study was approved by the Ethical Scientific Committee of the University of Tarapacá (Approval Code: N° 11/2018) in accordance with national regulations for research involving human subjects (Law No. 20.120). Each detainee was interviewed and completed a structured survey designed to align with the study’s objectives, collecting data on age, risk behaviors associated with sexually transmitted infections, including sexual orientation, sexuality, drug use, age of first sexual activity, as well as other factors related to their incarceration, as reported28. For all patients in whom any pathogenic microorganism was detected, treatment and follow-up were initiated in accordance with the protocols of the CDPA Health Center.

Clinical analysis and diagnosis

A serological and microbiological analysis was conducted on the collected samples. Vaginal secretion samples were collected from 124 women using torula swabs for culture-based microbiological screening and Gram stained smear preparations. N. gonorrhoeae was cultured in Thayer-Martin medium, and yeasts were seeded in Sabouraud dextrose agar, and Cromo-Candida medium. A sterile tube containing physiological saline solution (NaCl 9‰) was used for fresh microscopic examination of Trichomonas vaginalis. Conventional microbiology methods26,29 were applied to detect these and other microorganisms, including Gardnerella vaginalis. A third Dacron torula swab was used for Chlamydia trachomatis detection via immunochromatography (FaStep Ref. CHL-S23, Inc., USA), following the manufacturer’s instructions. Briefly, The Chlamydia Rapid Test Device (Swab/Urine) detects Chlamydia trachomatis through visual interpretation of color development on the internal strip. Antigen-specific lipopolysaccharide (LPS) monoclonal antibody is immobilized on the test region of the membrane. A buffer containing anti-Chlamydia antibodies conjugated to colored particles. The presence of this colored band indicates a positive result. The appearance of a colored band at the control region serves as procedural control.

For serological testing by enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay (ELISA) techniques, venous blood samples were collected to detect antibodies against HIV-1 and HIV-2 (HIV Ag/Ab, Ref.51215, HUMAN Diagnostics, Wiesbaden, Germany) detect antibodies to HIV-1 (including group O) and HIV-2, and the HIV-1 p24 antigen in serum and plasma. Hepatitis B (HBs) HBsAg ultra sens Ref. 51,050, (HUMAN Diagnostics, Wiesbaden, Germany), for the qualitative detection of wild types and mutant variants of hepatitis B surface antigen (HBsAg) in human serum and plasma and hepatitis C (VHC) using the ELISA method 3rd generation (Wiener lab Ref. 864,118,510/00 Rosario, Argentina), for the detection of antibodies against the hepatitis C virus using recombinant antigens derived from the structural (core) and non-structural (NS3, NS4 and NS5) regions of the hepatitis C virus. All ELISA tests following the manufacturer’s instructions including positive and negative controls with which the positivity cut-off is determined in each determination. Syphilis serological diagnosis was performed using a modified VDRL test (Microgen Sclavo Diagnostics, Ref. 87,802, Solvicille, Italy), all according to the manufacturer’s instructions. Briefly, the patient’s serum inactivated at 56 °C for 30 min is challenged with the VDRL antigen is an alcoholic solution of cholesterol and phospholipids cardiolipin and lecithin, when immunoglobulins are present, it is observed the formation of clumps. Three control sera were included (Reactive, Weakly Reactive and Non-Reactive). A reactive score greater than or equal to 1:2 in the serological tests was considered positive. For HIV screening, a duplicate positive ELISA result was interpreted as preliminary possible positive and subsequently confirmed by the Arica Health Service at the Hospital Juan Noé Crevani, with further confirmation conducted at the Institute of Public Health (ISP), Chile. With the data from the results previously obtained from the clinical and microbiological traditional study, the samples with predominant Lactobacillus spp. growth were classified as "normal vaginal microbiota” (NVM) while cultures dominated by other microorganisms were categorized as "positive cultures o anormal vaginal microbiota (AVM)" according to various studies on the protective role of lactobacillus in this anatomical area and clinical diagnostic guides through the laboratory7,9,10,11,21,29,30,31,32,33.

In turn, the AVM group was subdivided into Pathogenic Cohort (PC) and Dysbiosis Cohort (DC) based on a combination of clinical diagnosis, microbiological culture results, and pathogen detection as explained in the previous paragraph. The PC group included participants with confirmed sexually transmitted infections (e.g., T. vaginalis, G. vaginalis, C. trachomatis, HIV), while the DC group included individuals with altered microbiota profiles mostly Lactobacillus depletion or Candida overgrowth but without major STI pathogens. This framework ensured biologically and clinically meaningful subgrouping for downstream analysis.

DNA sequencing and microbial community profiling

Amplicon sequencing of the 16S rRNA (targeting bacteria and archaea) and 18S rRNA gene (for eukaryotes) was performed on 48 clinical samples to characterize the vaginal microbiota (Supplementary Table 1). The DNA extraction was realized using the commercial Qiagen DNeasy PowerSoil Pro kit (catalog number 47014), following the manufacturer´s recommendations. DNA quantity and purity were assessed using a Qubit fluorometer (Thermo Fisher Scientific) and DNA integrity was verified by agarose gel electrophoresis. For 16S rRNA sequencing, the V3–V4 hypervariable region was amplified using region-specific primers with Illumina overhang adapter sequences: 341 F (5′TCGTCGGCAGCGTCAGATGTGTATAAGAGACAGCCTACGGGNGGCWGCAG-3′) and 785R (5′GTCTCGTGGGCTCGGAGATGTGTATAAGAGACAGGACTACHVGGGTATCTAATCC-3′). Normalized libraries were pooled in equimolar concentrations and denatured with 0.2 N NaOH. Sequencing was performed on an Illumina MiSeq platform using a MiSeq Reagent Kit v3 (600-cycle) to generate 2 × 300 bp paired-end reads, following the manufacturer’s instructions. A 15% PhiX control was added to increase sequence diversity. For 18S rRNA, the V9 region was targeted using primers Forward (5′-TCGTCGGCAGCGTCAGATGTGTATAAGAGACAG-3′) and Reverse (5′-GTCTCGTGGGCTCGGAGATGTGTATAAGAGACAG-3′). Libraries were prepared using the Nextera XT DNA Library Preparation Kit (Illumina) and sequenced on an Illumina MiSeq platform (2 × 300 bp paired-end reads). The average number of raw reads per sample was 68,678.98 (SD: 18,508.14) for the 16S rRNA gene and 3,981,566 (SD: 26,839.19) for the 18S rRNA gene. Raw sequencing data were processed using QIIME 2 (version 2023.2.0), following a previously described pipeline18. Sequence quality control, denoising, chimera removal, and read truncation were performed using the DADA2 plugin34 within QIIME 2. For the 16S dataset, paired-end reads were truncated at 300 bp for the forward reads and 240 bp for the reverse reads, based on the observed quality profiles. For the 18S dataset targeting the V9 region, truncation lengths were set to 210 bp (forward) and 190 bp (reverse). In both datasets, default denoising parameters were used, with the minimum fold-parent-over-abundance for chimera filtering set to 4. A full summary of read counts and filtering results is provided in Supplementary Table 1. After denoising and chimera removal, amplicon sequence variants (ASVs) were inferred and used for downstream taxonomic analysis. Taxonomic classification of ASVs was performed using the QIIME 2 plugin feature-classifier and a Naive Bayes classifier trained on full-length 99% OTUs from the SILVA15 v138 reference database (trained 2024–05-30; Sklearn v1.4.2)35. The classifier was custom-trained using full-length 99% OTUs trimmed to the amplified 16S region targeted by the specific primers used in this study, ensuring optimal resolution for this specific locus. To improve taxonomic accuracy within the genus Lactobacillus, representative ASVs assigned to this genus were further validated by BLASTn against the NCBI nt database. All sequences not corresponding to the target domain were removed from the 16S and 18S datasets to ensure kingdom-specific integrity. To assess microbial community richness, evenness, and diversity, we computed multiple alpha- and beta-diversity metrics using QIIME 216. A comprehensive list of the metrics used is provided in (Supplementary Table 2). For the beta diversity analysis, we evaluated community dissimilarities using multiple distance metrics, the selection of alpha diversity metrics was guided by the analytical framework proposed by Cassol et al. (2025)14, including Bray–Curtis, Jaccard, and weighted UniFrac. These metrics allowed us to capture differences in microbial composition including shared and unique taxa, based on distinct ecological principles: Jaccard measured community dissimilarity based on presence-absence data, Bray–Curtis accounted for relative abundance-weighted differences, and weighted UniFrac incorporated phylogenetic relationships while also considering taxon abundances. To classify the vaginal microbiota into Community State Types (CSTs), we used the Valencia tool, which infers CST profiles based on QIIME 2 output data. The CST assignment was guided by the reference framework proposed by France et al. 202011.

Statistical analysis and visualization

Statistical analyses were performed using GraphPad Prisma 6.0. This considered a bivariate analysis, relative risk (RR), and odds ratio (OR) calculations. RR and OR were calculated as in28. Continuous variables were analyzed using the Wilcoxon-Mann–Whitney test, while categorical variables were analyzed using Fisher’s exact test, with statistical significance set at p ⩽ 0.05. For multivariate analysis, Principal Coordinate Analysis (PCoA) was performed using an in-house Python script with the scikit-bio library36. The analysis was based on Bray–Curtis dissimilarity values calculated from relative taxonomic abundances. The Adonis test (999 permutations) was conducted to assess group differences. To ensure robust multivariate comparisons, homogeneity of beta-diversity variance across groups was assessed through dispersion analysis, performed using the ieggr and vegan packages in R. Additionally, ANOVA post hoc tests were performed to compare group differences. All figures were generated using an in-house script with matplotlib.

Results

Cohort description

The study included 124 women with an average age of 35.6 years (SD: 10.5 years), ranging from 19 to 57 years. The serological prevalence of sexually transmitted infections among the participants is summarized in (Supplementary Table 1). According to these results 33.1% (42/124) of the incarcerated individuals tested positive for at least one of the infections. Notably, women under the age of 34 accounted for 66.7% of the STI cases [p-value = 0.0079; RR = 2.10 (1.22–3.60); OR = 3.00 (1.38–6.51)]. Prisoners who had consumed drugs, specifically cocaine and cannabis-based paste, exhibited a higher prevalence of STIs compared to non-users, with infection rates of 43.1% and 20.0%, respectively [p-value = 0.0077; RR = 2.15 (1.19–3.99); OR = 3.02 (1.35–6.79)]. A clear association between the number of sexual partners and STI prevalence was also observed. Women with one sexual partner in the last five years had a prevalence of STIs of 26.8%, while those with two sexual partners had a prevalence of 42.4%, and those with three or more partners had a prevalence of 44.0% [p-value = 0.0540; RR = 1.64 (1.00–2.70); OR = 2.15 (1.00–4.63)]. Results of vaginal flow cultivation for the 124 fluid samples revealed that 53.2% (66/124) of participants had a positive culture result, while 46.8% (58/124) tested negative for all screened pathogens. Four individuals were co-infected with more than one pathogen.

Vaginal secretion samples (n = 48) were collected from patients who had the results of the test previously shown, according to these they were separated into normal and altered (dysbiosis or pathogen) group22,25,29,37 and utilized for microbial community pro-filing through 16S rRNA and 18S rRNA sequencing (Table 1). These 48 samples correspond to a subset of the 124 participants for whom microbiological culture and serological STI data were previously obtained. The selection included all individuals with a positive pathogen detection (n = 25), along with a group of 23 pathogen-negative participants matched by age and sexual behavior, to enable balanced comparison across microbial and clinical profiles. Based on clinical results, participants were stratified into three groups of 16 individuals each (Control, Dysbiosis, and Pathogenic cohorts), as shown in Table 1. Demographically, the control cohort consisted of 16 participants averaging 36 years, all of whom tested negative for STIs and vaginal infections. The pathogenic microbiota cohort (mean age: 33 years) had a high prevalence of infections, with 7 participants testing HIV-positive, 12 testing positive for G. vaginalis, 8 for T. vaginalis, 3 for Candida spp. infections, and multiple STIs, including syphilis (n = 3), C. trachomatis (n = 2), and N. gonorrhoeae (n = 1). In turn, the Dysbiosis Cohort (mean age: 39 years) was characterized by a Lactobacillus depletion in culture and high prevalence of Candida spp. infections (10 participants). This group was defined based on clinical findings and microbiological culture and serological study, consistent with recent definitions of vaginal dysbiosis as an ecological imbalance involving the overgrowth of opportunistic microorganisms (such as Candida spp.) and/or the loss of dominance by Lactobacillus spp., even in the absence of classical STI-associated pathogens4,11,38.

Alpha diversity of vaginal microbiota

We next assessed the microbial diversity in women with Normal Vaginal Microbiota (NVM), also referred here to as the Control Cohort (CC), and Altered Vaginal Microbiota (AVM)39. To further refine the classification, the AVM group was further subcategorized based on the presence of sexually transmitted and vaginal infections into two cohorts: Pathogenic Cohort (PC) and Dysbiosis Cohort (DC), following the study’s methodological framework. We compared microbial diversity across the prokaryotic and eukaryotic domains. A total of 25 alpha diversity analyses were computed for both the prokaryotic and eukaryotic communities (Supplementary Table 2) and Shannon, Simpson, and Fisher indices were chosen for displaying representative results (Fig. 1).

Alpha diversity metrics of vaginal microbiota across sample groups. Panel (A) displays the Shannon diversity index, indicating differences in bacterial diversity among the Control Cohort (CC), Dysbiosis (DC), and Pathogenic Cohort (PC) groups. Panel (B) shows the Simpson diversity index, emphasizing evenness in microbial communities. Panel (C) shows the Fisher alpha index, representing species richness and diversity patterns. The results indicate that the Pathogenic Cohort exhibits the highest microbial diversity compared to the Normal and Dysbiosis groups.

Statistical analysis revealed no significant variation in the alpha-diversity of prokaryotes across samples in the AVM group (p value > 0.05), independently of the index considered. Despite this fact, differences were apparent between these groups. For prokaryotes, the Shannon index was slightly higher in PC (mean: 7.259 ± 1.010) than in DC (mean: 6.791 ± 1.273), suggesting a trend toward increased microbial richness in PC (Table 1, Fig. 1). Similarly, the Simpson index aligned with this observation, indicating a more even distribution of taxa in PC. Conversely, eukaryotic diversity exhibited less pronounced differences between cohorts, with Shannon index values of 1.91 ± 0.70 for PC and 2.12 ± 0.53 for DC. Although the Pathogenic Cohort (PC) showed numerically higher alpha diversity values in prokaryotic, and less in eukaryotic communities, compared to the Dysbiosis Cohort (DC), these differences did not reach statistical significance (p > 0.05). Therefore, such trends should be interpreted cautiously and do not support definitive conclusions about cohort-level differences in microbial richness or evenness. These patterns nonetheless suggest potential ecological variation across clinical subgroups, warranting further investigation (Supplementary Table 2).

Beta diversity and microbial community differences

Beta-diversity metrics (Supplementary Table 3, Supplementary Table 4) were analyzed to assess the overall dissimilarity between cohorts. Bray–Curtis, Jaccard and Weighted UniFrac distances were used (Table 2). Bray–Curtis, Jaccard, and Weighted UniFrac distances were used as metrics (Table 2). For prokaryotic communities, PERMANOVA results showed low pseudo-F values (0.91 for Bray–Curtis, 1.06 for Jaccard, and 0.81 for Weighted UniFrac) and non-significant p-values (p > 0.3 in all cases), indicating no significant differences between groups. Similarly, eukaryotic communities also showed non-significant results, with pseudo-F values of 0.42, 0.83, and 1.12 for Bray–Curtis, Jaccard, and Weighted UniFrac respectively, and p-values ≥ 0.34. ANOSIM analyses yielded R values close to zero or negative (e.g., R = 0.002 for Bray–Curtis in prokaryotes, R = –0.05 for eukaryotes), with all p-values > 0.25. Despite the lack of statistical significance in PERMANOVA and ANOSIM, Principal Component Analysis (PCoA) and Hierarchical Clustering Dendrograms of Weighted UniFrac and Bray Curtis, respectively (Fig. 2) suggest qualitative differences in microbial community composition among groups. In the Prokaryote PCoA plot (Fig. 2A), DC and PC samples appear to form distinct clusters, represented by orange and red dashed ovals, respectively. Additionally, it was observed that the DC group shares similarities with the CC group. In the Eukaryote PCoA plot (Fig. 2B), DC samples are visibly distinguishable from other groups although it does not represent a statistically significant difference with respect to the other groups. Furthermore, Fig. 2C shows that PC samples are distributed, mainly but not exclusively, between groups 2 and 3, DC and CC samples span all three groups. In contrast, the 18S rRNA eukaryotic data did not show clear evidence of clustering (Fig. 2D), except for a notable grouping of CC samples within group 3, comprising 10 CC samples. The spatial distribution of samples in ordination space may reflect qualitative tendencies in microbial composition between clinical cohorts; however, no statistically significant differences were detected. Altogether, these observations suggest that while statistically significant differences were not detected using PERMANOVA or ANOSIM, the clustering patterns in the PCoA plots may reflect ecological or compositional differences between groups that are not fully captured by the tested beta-diversity metrics. However, these patterns should be interpreted cautiously given the limitations in taxonomic resolution.

PCoA and Hierarchical Clustering Dendrograms of vaginal microbial communities. Panel (A) shows the PCoA plot for prokaryotes with clustering of Dysbiosis (DC) and Pathogenic (PC) groups. Panel (B) displays the PCoA plot for eukaryotes, highlighting distinct separation of the DC group. Panels (C) and (D) present hierarchical clustering for prokaryotes and eukaryotes, respectively, showing sample distributions across groups. Clustering patterns are shown as qualitative tendencies and do not imply statistically significant separation between groups. Full pairwise distance matrices are provided in Supplementary Table 3 and Supplementary Table 4. The visual appreciation of a few points corresponds to an overlap of the samples in the same place.

Taxonomy composition of prokaryotic and eukaryotic of vaginal microbiota

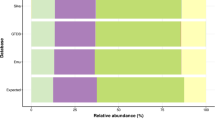

To characterize the composition of the microbiota of the AVM subjects and cohorts, microbial taxonomy assignment was performed using the QIIME2 pipeline, comparing sequences against the classifier. Analysis of taxonomic domain composition across all vaginal samples revealed a predominance of eukaryotic sequences, accounting for approximately 62.7% of total counts, followed by bacterial sequences at 35.6%, with archaeal (0.2%) and unassigned (1.5%) sequences representing minor proportions (Fig. 3A, Supplementary Table 5). At the bacterial phylum level (Fig. 3B), Firmicutes more than 90% of the bacterial community of the total bacterial abundance across all clinical groups. Notably, the CC and DC groups exhibited the highest proportions of Firmicutes (over 60%). In contrast, individuals in the PC group showed increased relative abundances of Bacteroidota and Actinobacteriota, although these remained minor constituents overall. Crenarchaeota, an archaeal phylum, was detected at low relative frequency. In the case of the eukaryotic phylum composition, among the classified taxa, members of the fungal phyla Ascomycota and Basidiomycota were frequently detected, although at lower relative abundances. Notably, the phylum Parabasalia, which includes Trichomonas vaginalis, was observed in a limited number of samples and was consistent with some Trichomonas-positive individuals.

Taxonomic composition of the vaginal microbiota. (A) Distribution at the domain level showing the relative frequency of Bacteria, Eukaryota, and Archaea. (B) Relative abundance at the phylum level across groups. (C) Heatmap of presence/absence for the top taxa considered relevant, with samples grouped by clinical condition (CC, DC, PC) and annotated by Community State Type (CST). Color-coded bars on the right indicate CST assignment for each sample.

In agreement with previous reports13, Lactobacillus was the dominant genus, accounting for over a 50% of count reads of the total prokaryotic microbiota. In the other genus level, with the highest relative abundance in the CC group and a noticeable decline in the DC and PC groups, consistent with progressive shifts toward dysbiosis. In contrast, the DC and PC groups showed a greater presence of genera from the phyla Actinobacteriota and Bacteroidota, including taxa typically associated with bacterial vaginosis, such as Prevotella (Supplementary Table 5). Community structure analysis based on the presence/absence and co-occurrence patterns of key taxa revealed a predominance of Lactobacillus crispatus-dominated profiles, typically associated with vaginal health or transitional states. In our cohort, most samples from the CC and DC subgroups exhibited taxonomic compositions consistent with CST-I or CST-I/III characteristics. (Fig. 3C, Supplementary Table 6). In contrast, CST-IV, characterized by a low abundance of Lactobacillus and higher diversity of anaerobic genera, was mainly associated with samples from the PC subgroup.

Dominance of lactobacillus genus

The absolute reads of Lactobacillus showed a significant decreasing trend across clinical cohorts (p < 0.01), with the highest levels observed in the DC group, followed by CC and finally PC (Supplementary Table 6). Specifically, Lactobacillus exceeded 50% relative abundance in 56.3% of CC samples, 62.5% of DC samples, and only 37.5% of PC samples.

In samples dominated (n = 25) by Lactobacillus (i.e., relative abundance > 50%), resented significantly lower Shannon entropy compared to non-dominant ones (n = 23), suggesting reduced microbial diversity in Lactobacillus-dominated communities (Fig. 4B), Moreover, individuals classified as having abnormal vaginal microbiota (AVM) showed higher Shannon entropy values compared to those with normal microbiota (NVM), highlighting a shift toward more diverse microbial communities in AVM cases (Fig. 4C).

Analysis of Lactobacillus abundance and Shannon entropy in vaginal microbiota across conditions. (A) Boxplot of Lactobacillus absolute reads across Control Cohort (CC), Dysbiosis Cohort (DC), and Pathogenic Cohort (PC). (B) Shannon entropy comparison between microbiota dominated (n = 25) by Lactobacillus and non-dominated (n = 23) microbiota. (C) Shannon entropy comparison between Normal Vaginal Microbiota (NVM) and Altered Vaginal Microbiota (AVM) within the Lactobacillus-dominated group. Outliers were removed from the plots for clarity.

We assessed the relative frequency of Lactobacillus in relation to the presence or absence of five infections: syphilis, HIV, Gardnerella vaginalis, Trichomonas vaginalis, and Candida (Fig. 5A, Supplementary Table 5). To explore the relationship between STIs and the dominance of Lactobacillus in the vaginal microbiota, we constructed a Sankey diagram representing the distribution of dominant and non-dominant microbiota profiles across five infections: VDRL, HIV, Gardnerella vaginalis, Trichomonas vaginalis, and Candida (Fig. 5B). Among samples positive for VDRL, most exhibited a non-dominant microbiota (3 out of 4), whereas only 1 sample was dominated by Lactobacillus. In the case of HIV-positive samples, the distribution was more balanced, with 4 dominated and 3 non-dominated profiles. For Gardnerella vaginalis and Trichomonas, a higher number of positive samples were classified as non-dominated (8 and 5, respectively), suggesting a loss of Lactobacillus dominance in these contexts. Interestingly, among Candida-positive samples, the majority (9 out of 13) maintained Lactobacillus dominance. To assess microbial diversity in relation to STIs, we analyzed Shannon entropy across samples categorized as positive or negative for VDRL, HIV, Gardnerella vaginalis, Trichomonas vaginalis, and Candida (Fig. 5C). Overall, Shannon entropy was generally higher in STI-positive samples, suggesting increased microbial diversity in association with infection. This trend was most evident in samples positive for Gardnerella vaginalis and Trichomonas vaginalis, where higher entropy values reflected the characteristic loss of Lactobacillus dominance and emergence of diverse anaerobic taxa. Conversely, HIV-positive and Candida-positive samples did not exhibit substantial differences in diversity compared to their negative counterparts.

Relationship between sexually transmitted infections and Lactobacillus dominance. (A) Barplots comparing the relative abundance between samples positive and negative for VDRL, VIH, Gardnerella vaginalis, Trichomonas vaginalis, and Total Candida. The black dot within each violin represents the median value of the distribution. (B) Sankey diagram showing the relationship between Lactobacillus dominance (Dominated vs. Non-Dominated) and STIs. The width of the connections represents the frequency of each association, with blue tones representing dominated samples and darker blue representing non-dominated samples, while the nodes are displayed in light gray for clarity. (C) Violin plots comparing the Shannon entropy between samples positive and negative for VDRL, VIH, Gardnerella vaginalis, Trichomonas vaginalis, and Total Candida. The black dot within each violin represents the median value of the distribution.

Discussion

The results obtained in this study suggests that certain factors may influence the microbial diversity in the PC group, resulting in a distinct microbial community composition. These findings underscore the importance of considering both prokaryotes and eukaryotes when studying microbial diversity and their potential implications in different sample groups. The concept that microbial consortia promote human health is ancient, especially based on the work of Döderlein (1892) and the role of Lactobacillus as protectors of the vaginal ecosystem. Metchnikoff’s work with dairy products fermented by lactobacillus also adds to this protection. Studies like this and others of human metagenomics help to understand the microbiome and its variations, especially in pathological states2. Commensal microorganisms such as Lactobacillus can promote a hostile environment for the establishment of pathogens such as Gardnerella, Mycoplasmas and others in the vaginal environment, protecting against pathogenic colonization by reducing local pH30. Lactobacilli act as a protective barrier to prevent pathogenic colonization. They also have the ability to produce antimicrobial compounds, such as hydrogen peroxide, lactic acid, and bacteriocin-like substances which are extremely important in the impairment of colonization by pathogens associated with different types of infections (for example, bacterial vaginosis, vulvovaginal candidiasis and aerobic vaginitis)32,40,41.

In the study of the oral microbiota and its interactions related to the immune system, it is associated with its ability to promote inflammasome activity that leads to the local increase of the inflammatory cytokine IL-1β42. In other anatomical sites such as the lung and vaginal mucosa, the role of commensals in tissue immunity is just being studied. For example, at the lung level, in the absence of commensal bacteria, Th2 lymphocytes and cells such as eosinophils are high, and the composition and activation state of pulmonary dendritic cells is altered during airway inflammation43. It has also been observed that the vaginal microbiota drives the innate activity of the immune response since the vaginal microbiota stimulates pattern recognition receptors (PRRs) in the epithelial cells that line the vaginal mucosa and the upper genital tract and initiates cytokine signaling cascades, such as the release of interleukin IL-1β, IL-6, IL-8, and Tumor Necrosis Factor alpha (TNF-α)44. TNF-α recruits or activates immune cells such as natural killer (NK) cells, macrophages, CD4 + T helper cells, T lymphocytes, and CD8 + cytotoxic B lymphocytes. Bacterial vaginosis (BV) is one of the most common vaginal dysbiosis due to the decrease in Lactobacillus spp. and the increase in the concentration of other bacteria associated with BV. BV pathogenic bacteria such as Gardnerella vaginalis and Prevotella bivia inhibit the inflammatory response in the host vaginal epithelium45. A study by Garcia et al. revealed that G. vaginalis infection does not cause changes in the level of proinflammatory mediators such as IL-1β, IL-6, MIP-3α, or TNF-α, while Atopobium vaginae induces a wide range of proinflammatory effects46. Cytokines, chemokines, and antimicrobial peptides including IL-1β, IL-6, IL-8, MIP-3α, TNF-α, and hBD-2. On the other hand, P. bivia induces less of the immune response; IL-1β and macrophage inflammatory protein (MIP)−3α47. This was observed in our study regarding the decrease in Lactobacillus and the increase in other opportunistic pathogenic bacteria, which may be due to changes in the immune response of the patients that would put them at risk of infections such as those studied.

In the reproductive tract of women there are structural differences in the composition of microorganisms throughout the menstrual cycle, which translates into changes in the microbiome. As a limitation to our study, vaginal samples were taken from women who were not menstruating, therefore, microorganisms from this period were not sequenced. In Du’s study, where they performed metagenomic sequencing to characterize the microbiome, differences between the cervix and the mid-vaginal mucosa throughout the menstrual cycle in healthy women showed that the bacteria in the cervix and the mid-vaginal mucosa were similar during the periovulatory phases. and luteal, with Lactobacillus being the dominant bacteria, as found in our study, but in the follicular phase it can vary to Acinetobacter, for example in the cervix24. In our study was observed that the vaginal microbiota, like the intestine, also plays a crucial role in resisting the colonization of pathogenic microbiomes, which is important to prevent STIs, urinary tract infections and vulvovaginal candidiasis. Traditionally, study methods showed that the vaginal microbiota is a community of Lactobacillus species. Additionally, the vaginal microbial community may be composed of anaerobic bacteria, including Gardnerella vaginalis, Prevotella spp., Mobiluncus spp., Ureaplasma urealyticum, and Mycoplasma hominis, but a normal healthy community identifies Lactobacilli as important and predominant members of the vaginal microbiota. To better understand the vaginal microbiota, the vaginal microbiota community of bacteria has been grouped within various types known as community state types (CST) I – V. The communities CST I, II, III y V are dominated by L. crispatus, L. gasseri, L. iners, polymicrobial flora, including Lactobacillus and bacterial vaginosis-associated bacteria (BVAB) in less dominance, and L. jensenii. Lactobacillus species provide protection by generating bactericidal and viricidal agents, including lactic acid and bacteriocins27. CST IV which did not have a high relative abundance of lactobacilli and a high relative abundance of Candidatus Lachnocurva vaginae, G. vaginalis, Atopobium vaginae and other anaerobic or facultative bacteria11. In our study we found dominance of L. crispatus (CST I) in NVM which differs with France et al. where Hispanic women presented stage CST III-A, but agrees in AVM was found by and CST IV-B profiles with G. vaginalis.

In a study by Schwebke et al. found that women treated with atypical gram-positive bacteria showed a lower risk of incidence of genital chlamydial infection48. In another study with 3,620 nonpregnant women, Brotman et al. showed an association between BV and high risk of genital infection due to gonococcal, chlamydial, and trichomonal49. On the other hand, there are studies that associate the presence of Lactobacillus with other infections such as human immunodeficiency (HIV), papillomavirus and herpes simplex virus infections45. Linking all this to resistance to vaginal colonization, it has been widely agreed that resistance to vaginal colonization plays crucial protective functions in the prevention of pathogenic infections.

Conclusion

In the study of the diversity of the alpha vaginal microbiota we have observed a high diversity, although it is not statistically significant, was observed in the group of women who were classified in the pathogenic group in prokaryotes while the group classified as dysbiosis, and normal diversity alpha was very similar. On the other hand, the analysis of beta diversity through PCoA between the groups was similar for all groups, but a clustering was evident in the samples from the group with women with control and pathogen, dysbiosis group it is distributed in the three groups. In the analysis of the taxonomic composition of the vaginal microbiota, it was observed that it is predominantly occupied by bacteria and within them the Phylum Firmicutes is the most abundant and, in turn, within the Firmicutes the most abundant genus is Lactobacillus, especially in women of the normal group followed by the dysbiosis group, being lower in the group of women with a vaginal pathogen. In the study of the dominance of Lactobacillus genus we found that clearly when they dominate the microbiome the entropy or diversity decreases, which is totally opposite to when it is not the dominant genus, as occurs in the group of women classified within the pathogen group. In this group it is observed that the presence of pathogens such as T. vaginalis, G. vaginalis, and T. pallidum, is accompanied by a significant increase in the diversity of the microbiome. Its study and determination being relevant in understanding the complex relationships established in this anatomical site between healthy and altered microbiome.

Data availability

The sequence data have been deposited in the NCBI Sequence Read Archive (SRA) under accession number PRJNA1215533.

References

Zheng, D., Liwinski, T. & Elinav, E. Interaction between microbiota and immunity in health and disease. Cell Res. 30, 492–506 (2020).

Belkaid, Y. & Hand, T. W. Role of the microbiota in immunity and inflammation. Cell 157, 121–141 (2014).

Microbiota: Current Research and Emerging Trends. Microbiota: Current Research and Emerging Trends (2019) https://doi.org/10.21775/9781910190937.

Hou, K. et al. Microbiota in health and diseases. Sig. Transduc. Targeted Ther. 7, 1–28 (2022).

Aggarwal, N. et al. Microbiome and Human Health: Current Understanding, Engineering, and Enabling Technologies. Chem. Rev. 123, 31–72 (2023).

Ogunrinola, G. A., Oyewale, J. O., Oshamika, O. O. & Olasehinde, G. I. The Human Microbiome and Its Impacts on Health. Int. J. Microbiol. 2020, 8045646 (2020).

Moreno del Castillo, M. C., Valladares-García, J. & Halabe-Cherem, J. Microbioma humano. Revista de la Facultad de Medicina (México) 61(6), 7-q9 (2018).

del Campo-Moreno, R., Alarcón-Cavero, T., D’Auria, G., Delgado-Palacio, S. & Ferrer-Martínez, M. Microbiota en la salud humana: Técnicas de caracterización y transferencia. Enferm. Infecc. Microbiol. Clin. 36, 241–245 (2018).

Alonzo Martínez, M. C. et al. Study of the Vaginal Microbiota in Healthy Women of Reproductive Age. Microorganisms 9, 1069 (2021).

Zheng, N., Guo, R., Wang, J., Zhou, W. & Ling, Z. Contribution of Lactobacillus iners to Vaginal Health and Diseases: A Systematic Review. Front. Cell Infect. Microbiol. 11, 792787 (2021).

France, M. T. et al. VALENCIA: A nearest centroid classification method for vaginal microbial communities based on composition. Microbiome 8, 1–15 (2020).

Lewis, F. M. T., Bernstein, K. T. & Aral, S. O. Vaginal microbiome and its relationship to behavior, sexual health, and sexually transmitted diseases. Obstet. Gynecol. 129, 643–654 (2017).

Diop, K., Dufour, J. C., Levasseur, A. & Fenollar, F. Exhaustive repertoire of human vaginal microbiota. Hum. Microb. J. 11, 100051 (2019).

Hughes, J. B., Hellmann, J. J., Ricketts, T. H. & Bohannan, B. J. M. Counting the Uncountable: Statistical Approaches to Estimating Microbial Diversity. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 67, 4399 (2001).

Quast, C. et al. The SILVA ribosomal RNA gene database project: Improved data processing and web-based tools. Nucleic Acids Res. 41, D590–D596 (2013).

Cassol, I., Ibañez, M. & Bustamante, J. P. Key features and guidelines for the application of microbial alpha diversity metrics. Sci. Rep. 15, 622 (2025).

Sun, Z. et al. Vulvovaginal candidiasis and vaginal microflora interaction: Microflora changes and probiotic therapy. Front. Cell Infect. Microbiol. 13, 1123026 (2023).

Bolyen, E. et al. Reproducible, interactive, scalable and extensible microbiome data science using QIIME 2. Nat. Biotechnol. 37, 852–857 (2019).

Kapinusova, G., Lopez Marin, M. A. & Uhlik, O. Reaching unreachables: Obstacles and successes of microbial cultivation and their reasons. Front. Microbiol. 14, 1089630 (2023).

Kairys, N., Carlson, K. & Garg, M. Bacterial Vaginosis. Stat Pearls 1–6 (2024).

Vazquez, F., Fernández-Blázquez, A. & García, B. Vaginosis. Microbiota vaginal. Enferm. Infecc. Microbiol. Clin. 37, 592–601 (2019).

Thurman, A. R. & Doncel, G. F. Innate Immunity and Inflammatory Response to Trichomonas vaginalis and Bacterial Vaginosis: Relationship to HIV Acquisition. Am. J. Reprod. Immunol. 65, 89–98 (2011).

Van De Wijgert, J. H. H. M. et al. The Vaginal Microbiota: What Have We Learned after a Decade of Molecular Characterization?. PLoS ONE 9, e105998 (2014).

Du, L. et al. Temporal and spatial differences in the vaginal microbiome of Chinese healthy women. PeerJ 11, e16438 (2023).

Prevalence and incidence of selected sexually transmitted infections, Chlamydia trachomatis, Neisseria gonorrhoeae, syphilis and trichomonas vaginalis : methods and results used by WHO to generate 2005 estimates. https://iris.who.int/handle/10665/44735.

Miller, J. M. et al. A Guide to Utilization of the Microbiology Laboratory for Diagnosis of Infectious Diseases: 2018 Update by the Infectious Diseases Society of America and the American Society for Microbiology. Clin. Infect. Dis. 67, e1 (2018).

Hou, K. et al. Microbiota in health and diseases. Sig. Transduct. Target Ther. 7, 135 (2022).

Bórquez, B. C. et al. Prevalencia de infecciones de transmisión sexual e infecciones vaginales en grupo de mujeres reclusas de la cárcel de Arica. Rev. Chilena Infectol. 39, 421–431 (2022).

Silva, V., Alburquenque, C., Ramírez, C., Silva, V. & Sanchez, M. Microbiología clinica y diagnóstico de laboratorio. Microbiología clínica y diagnóstico de laboratorio. 138p ISBN: 978–956–7459–35–3 (2011).

Turovskiy, Y., Sutyak Noll, K. & Chikindas, M. L. The aetiology of bacterial vaginosis. J. Appl. Microbiol. 110, 1105–1128 (2011).

Rodríguez-Arias, R. J., Guachi-Álvarez, B. O., Montalvo-Vivero, D. E. & Machado, A. Lactobacilli displacement and Candida albicans inhibition on initial adhesion assays: A probiotic analysis. BMC Res. Notes 15, 1–7 (2022).

Pacha-Herrera, D. et al. Clustering Analysis of the Multi-Microbial Consortium by Lactobacillus Species Against Vaginal Dysbiosis Among Ecuadorian Women. Front. Cell Infect. Microbiol. 12, 863208 (2022).

Miller, J. M. et al. Guide to Utilization of the Microbiology Laboratory for Diagnosis of Infectious Diseases: 2024 Update by the Infectious Diseases Society of America (IDSA) and the American Society for Microbiology (ASM). Clin. Infect. Dis. https://doi.org/10.1093/CID/CIAE104 (2024).

Callahan, B. J. et al. DADA2: High-resolution sample inference from Illumina amplicon data. Nat. Methods 13, 581–583 (2016).

Robeson, M. S. et al. RESCRIPt: Reproducible sequence taxonomy reference database management. PLoS Comput. Biol. 17, e1009581 (2021).

Namkung, J. Machine learning methods for microbiome studies. J. Microbiol. 58, 206–216 (2020).

Bórquez, C. et al. Prevalence of sexually transmitted infections and vaginal infections in women inmates of a prison in Arica city. Rev. Chilena Infectol. 39, 421–431 (2022).

Borrego-Ruiz, A. & Borrego, J. J. Microbial Pathogens Linked to Vaginal Microbiome Dysbiosis and Therapeutic Tools for Their Treatment. Acta Microbiologica Hellenica 70, 19 (2025).

Lee, S. et al. Community state types of vaginal microbiota and four types of abnormal vaginal microbiota in pregnant korean women. Front. Public Health 8, 507024 (2020).

Castillo-Juárez, I., Blancas-Luciano, B. E., García-Contreras, R. & Fernández-Presas, A. M. Antimicrobial peptides properties beyond growth inhibition and bacterial killing. PeerJ 10, e12667 (2022).

Scillato, M. et al. Antimicrobial properties of Lactobacillus cell-free supernatants against multidrug-resistant urogenital pathogens. Microbiologyopen 10, e1173 (2021).

Dixon, D. R., Reife, R. A., Cebra, J. J. & Darveau, R. P. Commensal bacteria influence innate status within gingival tissues: A pilot study. J. Periodontol. 75, 1486–1492 (2004).

Herbst, T. et al. Dysregulation of allergic airway inflammation in the absence of microbial colonization. Am. J. Respir. Crit. Care Med. 184, 198–205 (2011).

Aiyar, A. et al. Influence of the tryptophan-indole-IFNγ axis on human genital Chlamydia trachomatis infection: Role of vaginal co-infections. Front. Cell Infect. Microbiol. 4, 72 (2014).

Gilbert, N. M. et al. Gardnerella vaginalis and Prevotella bivia Trigger Distinct and Overlapping Phenotypes in a Mouse Model of Bacterial Vaginosis. J. Infect. Dis. 220, 1099–1108 (2019).

Garcia, E. M., Kraskauskiene, V., Koblinski, J. E. & Jefferson, K. K. Interaction of gardnerella vaginalis and vaginolysin with the apical versus basolateral face of a three-dimensional model of vaginal epithelium. Infect. Immun. 87, 10–1128 (2019).

Doerflinger, S. Y., Throop, A. L. & Herbst-Kralovetz, M. M. Bacteria in the Vaginal Microbiome Alter the Innate Immune Response and Barrier Properties of the Human Vaginal Epithelia in a Species-Specific Manner. J. Infect. Dis. 209, 1989–1999 (2014).

Schwebke, J. R. & Desmond, R. A randomized trial of metronidazole in asymptomatic bacterial vaginosis to prevent the acquisition of sexually transmitted diseases. Am. J. Obstet. Gynecol. 196(517), e1-517.e6 (2007).

Brotman, R. M. et al. Bacterial vaginosis assessed by gram stain and diminished colonization resistance to incident gonococcal, chlamydial, and trichomonal genital infection. J. Infect. Dis. 202, 1907–1915 (2010).

Acknowledgements

To all the staff of the Centro de Salud de Gendarmería del CDPA, Chile. Powered NLHPC: this research was partially supported by the supercomputing infrastructure of the NLHPC (CCSS210001) .

Funding

This work was supported by grants from Proyecto Investigación Mayor UTA2018:Code DIPTT 7722-20CC3657 (C.A). Competition for Research Regular Projects, year 2023, code LPR23-09, Universidad Tecnológica Metropolitana and Project supported by the Scientific and Technological Equipment Projects Competition, year 2024, code LE24-03, Universidad Tecnológica Metropolitana (A.M.-B.). Dirección de Investigación - Universidad Católica de Temuco, code 2023FIAS-MS-02 and 2023FEQUIP-RB-01. ANID/Fondecyt 1221035 and 32300527 (R.Q). Centro Ciencia & Vida, FB210008, Financiamiento Basal para Centros Científicos y Tecnológicos de Excelencia de ANID (R.Q., A.JM. M.). VRID-Universidad San Sebastián PROYECTO/USS-FIN-23-PDOC-03USS.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

Conceptualization, C.A., C.B., and A.M.-B.; methodology, A.M.-B, C.A., C.S, T.R.R, H.V.D., and C.S.S.; software, A.M.-B; formal analysis, A.M.-B, C.S., M.S, R.Q, A.JM.M, and C.A; investigation, A.M.-B, C.A.; data curation, A.M.-B, and C.A.; writing—original draft preparation, A.M.-B, and C.A; writing—review and editing, M.S., R.Q., A.JM.M; visualization, A.M.-B.; supervision, C.A.; project administration, C.A.; funding acquisition, A.M.-B, C.A., M.S, R.Q, A.JM.M. All authors reviewed the manuscript.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Ethics approval

The patients voluntarily agreed to participate and attended the health center of the Centro de Detention Preventiva de Arica y Parinacota (CDPA), after signing the informed consent. Informed consent was obtained from all the participants. Additionally, each inmate was interviewed through a survey focused on the objectives of the study. All methods were carried out in accordance with relevant guidelines and regulations.

Additional information

Publisher’s note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if you modified the licensed material. You do not have permission under this licence to share adapted material derived from this article or parts of it. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Moya-Beltrán, A., Sánchez, C., Bórquez B., C. et al. Characterization of vaginal prokaryotes and eukaryotes microbiota and its link to sexually transmitted infections. Sci Rep 15, 34073 (2025). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-14573-0

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-14573-0