Abstract

Proper lubrication is critical for ensuring the reliability and longevity of mechanical systems, yet its degradation due to factors like contamination or insufficient lubricant often leads to equipment failure. This study proposes a novel approach integrating Continuous Wavelet Transform (CWT) and Convolutional Neural Networks (CNN) for robust lubrication state identification. Vibration signals were collected from a pin-disk tribological system under three lubrication states: normal (NL), insufficient (IL), and contaminated (LC). CWT was applied to convert raw signals into time-frequency diagrams, which were preprocessed and input into a CNN model. The CNN architecture, comprising three convolutional layers, max pooling, and fully connected layers, was trained using the Adam optimizer with early stopping to prevent overfitting. Results demonstrated exceptional performance: the model achieved 99.8% training accuracy and 100% test accuracy, significantly outperforming traditional methods (RMS + CNN: 63.8%; PSD + CNN: 73.4%; CWT + SVM: 76.3%). t-SNE visualization confirmed distinct feature separation among lubrication states, and the confusion matrix revealed flawless classification on the test set. The method’s ability to capture time-frequency characteristics via CWT and leverage CNN’s deep feature learning offers a highly accurate and reliable solution for real-world lubrication monitoring.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

In mechanical systems, proper lubrication is of utmost importance. It serves to reduce friction, wear, and energy consumption, thereby ensuring the smooth operation and extending the service life of equipment1. However, lubrication conditions may progressively degrade due to factors including lubricant aging, contamination ingress, and improper maintenance practices, thereby increasing the risk of equipment failure and incurring significant production downtime2. Consequently, maintaining optimal lubrication regimes is critical for ensuring operational reliability and extending service life of mechanical systems.

Traditional methods for lubrication state monitoring mainly include oil analysis3temperature measurement4and vibration analysis5. Oil analysis can detect the physical and chemical properties of lubricants, but it is time-consuming and requires professional equipment6. Temperature measurement can reflect the operating temperature of the equipment, but it is not sensitive enough to the early stage of lubrication failure7. Vibration analysis is a commonly used method, which can detect the vibration characteristics of the equipment and infer the lubrication state8. Xinzhuo Zhang9 proposed a multi-sensor bearing lubrication monitoring method based on graph data integrating vibration, temperature, and acoustic emission signals. Serrato10 demonstrated a positive correlation between high-frequency vibration RMS (600–10 kHz) and lubrication film thickness reduction. Xiaoqiang Xu11 proposed a vibration-based lubrication starvation detection method using minimum entropy deconvolution (MED), where a spectral centroid indicator was employed to quantitatively assess lubrication deficiency in bearings. However, traditional vibration analysis methods are mainly based on time-domain or frequency-domain analysis, which cannot fully capture the time-frequency characteristics of vibration signals and have limited accuracy in identifying complex lubrication states. In addition, in engineering practice, the failure of lubrication is often caused by water mixed in the lubricating oil and wear particles pollution.

With the development of signal processing and artificial intelligence technologies, the combination of time-frequency analysis and deep learning has become a research hotspot in the field of mechanical equipment condition monitoring12,13. Continuous wavelet transform (CWT) is a powerful time-frequency analysis tool that can decompose vibration signals into different frequency bands and time intervals, and obtain the time-frequency distribution characteristics of signals14. Convolutional neural network (CNN) has excellent performance in image recognition and classification tasks, and can automatically extract features from input data15. The CWT + CNN method has achieved successful application in gearbox fault diagnosis16,17. Compared with gearbox fault diagnosis, lubrication failure involves distinct physical mechanisms, resulting in unique time-frequency patterns. This paper explores the application of the combined CWT - CNN method in identifying various types of lubrication failure states. By integrating these two techniques, we aim to fully capitalize on their respective strengths, thereby enhancing the accuracy and reliability of lubrication state identification.

Methodology

Continuous wavelet transform (CWT)

Wavelet transform is a multi-resolution analysis method. It realizes the decomposition and reconstruction of the signal by performing a convolution operation between the original signal and a set of wavelet basis functions. For the continuous wavelet transform (CWT)13,18its definition is:

where \(\:a\:\)is the scale factor, \(\:b\:\)is the translation factor, \(\:f\left(t\right)\) is the original signal, and \(\:\phi\:\left(t\right)\:\)is the wavelet basis function. The change of the scale factor \(\:a\) will change the scaling degree of the wavelet basis function, so as to analyze the different frequency components of the signal; the translation factor \(\:b\) is used to move the wavelet basis function on the time axis to cover the entire signal interval.

When performing wavelet transform on the vibration signal, an appropriate wavelet basis function and scale parameters are selected19. For each scale and time translation, the corresponding wavelet coefficients are calculated. These wavelet coefficients are plotted on a two-dimensional plane of scale and time to obtain a wavelet time-frequency diagram. In the wavelet time-frequency diagram, the abscissa represents time, the ordinate represents frequency, and the shade of gray or color represents the magnitude of the wavelet coefficient, thus intuitively reflecting the energy distribution and change of the signal in the time-frequency domain. Figure 1 shows the time-frequency diagram generated after the one-dimensional time series \(\:\text{sin}\left(100\pi\:t\right)+\text{s}\text{i}\text{n}\left(200\pi\:t\right)\) undergoes wavelet transform. It can be seen that the time-frequency characteristics of the signal can be better distinguished through wavelet transform.

Convolutional neural network

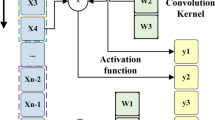

The convolutional neural network is a feed-forward neural network with a deep structure that contains clipped calculations. It is one of the representative algorithms of deep learning and has been applied to multiple fields such as image recognition and speech recognition. In recent years, it has also been applied to the field of fault diagnosis20. The convolutional neural network mainly consists of convolutional layers, pooling layers, fully connected layers, and activation functions.

The input layer processes multi-dimensional data in a standardized form, such as mean removal, normalization, and PCA.

In the convolutional layer, the convolution kernel performs a convolution operation on the output of the previous layer. The output of each layer is the result of the convolution of the input and the convolution kernel. Its mathematical model is21:

where \(\:{K}_{i}^{l}\) is the weight of the \(\:i\)-th convolution kernel at the \(\:l\)-th layer; \(\:{b}_{i}^{j}\:\)is the bias of the -th convolution kernel at the \(\:l\)-th layer; \(\:{x}^{l}\left(j\right)\:\)is the \(\:j\)-th local region at the \(\:l\)-th layer; \(\:{y}_{i}^{l+1}\left(j\right)\) is the input of the convolution at the \(\:(l+1)\)-th layer; and \(\:\:*\:\)represents the convolution operation.

A non-linear activation function is used in the convolutional layer to construct the output features. In this paper, the ReLU activation function is used to perform non-linear transformation on the logical output value of each convolution, enhancing the separability of features22. When the input value is greater than 0, the derivative value of the function is always 1, overcoming the problem of gradient dispersion. The formula of the ReLU activation function is:

Where \(\:{a}_{i}^{l+1}\left(j\right)\) is the activation value of \(\:{y}_{i}^{l+1}\left(j\right)\).

The pooling layer converts a large matrix into a small matrix through data downsampling. The purpose is to reduce the parameters of the neural network, reduce the amount of calculation, and prevent overfitting. In this method, the maximum pooling technique is adopted, and the maximum value in the region is taken as the output value. The formula for maximum pooling is:

Where \(\:{p}_{i}^{l+1}\left(j\right)\) is the value of the \(\:t\)-th neuron in the \(\:i\)-th feature of the\(\:\:\:\:l\)-th layer; \(\:W\:\)is the width of the pooling region; and \(\:{p}_{i}^{l+1}\left(j\right)\) is the value of the neuron at the \(\:\left(l+1\right)\)-th layer.

The flattening layer flattens the last pooling layer into a one-dimensional vector, which serves as the input of the fully connected layer, establishing the connection between the input vector and the output vector. The formula for the fully connected layer is:

Where \(\:{W}_{itj}^{l}\) is the connection weight between the \(\:t\)-th neuron in the \(\:i\)-th feature of the \(\:l\)-th layer and the \(\:j\)-th neuron of the (\(\:l+1)\)-th layer; \(\:{b}_{j}^{l}\:\:\)is the network bias; \(\:{a}_{i}^{l}\left(t\right)\:\:\)is the output value of the \(\:t\)-th neuron in the \(\:i\)-th feature of the previous layer \(\:l\); and \(\:f\) is the ReLU activation function.

The SoftMax classifier is used in the output layer to create classification labels. The SoftMax classifier is a form of linear classifier for multi - classification derived from logistic regression, with the formula:

where \(\:{z}^{0}\left(j\right)\) is the logical value of the \(\:j\)-th neuron in the output layer; and \(\:M\) is the total number of categories.

Lubrication state identification process

In order to achieve efficient identification of the lubrication status of mechanical equipment, this paper proposes a joint modeling method that combines time-frequency analysis and deep learning. This method aims to fully explore the discriminant features of vibration signals in the time-frequency domain, and effectively identify typical states such as normal lubrication, insufficient lubrication, and lubrication contamination by constructing a neural network model with adaptive feature learning capabilities. Based on this goal, this paper designs a set of systematic signal processing and classification processes, from the conversion of raw signals to the extraction and classification of features, to form a complete lubrication status identification framework. The overall architecture of the model is shown in Fig. 2.

This paper constructs a lubrication state recognition method based on continuous wavelet transform and convolutional neural network to complete the high-precision classification and recognition of the lubrication state of mechanical equipment. In the signal processing stage, continuous wavelet transform is used to map the collected original vibration signal from the time domain to the time-frequency domain to form a two-dimensional visualization image, whose mathematical definition is as follows:

Among them, \(\:x\left(t\right)\) is the time domain vibration signal, \(\:\phi\:*\left(t\right)\) is the mother wavelet function, \(\:a\) is the scale factor, and \(\:b\) is the time translation parameter. This transformation not only retains the instantaneous change characteristics of the signal, but also reveals the synchronous evolution of high-frequency mutations and low-frequency trends on the time axis, providing sufficient information basis for subsequent classification.

In the feature extraction and classification stage, a multi-channel convolutional neural network model with an asymmetric structure was constructed, stacking three layers of convolutional layers and maximum pooling layers in sequence to perform hierarchical feature learning on the input time-frequency graph. The convolution process can be expressed as:

Among them, \(\:{x}_{j}^{(l-1)}\) represents the \(\:j\)-th feature map of the previous layer, \(\:{w}_{jk}^{\left(l\right)}\) is the \(\:k\)-th convolution kernel of the \(\:l\)-th layer, and \(\:f\left(\right)\) is the ReLU activation function. The pooling operation uses the maximum pooling, and its expression is:

The above structure retains key signal features while reducing the dimension, and enhances the network’s ability to resist overfitting. The fully connected layer flattens the convolutional layer output and maps it to the classification space. The calculation process is:

The final output layer uses the Softmax function to achieve multi-class classification, and its expression is as follows:

In order to further improve the robustness of the model under complex working conditions, this paper introduces a feature projection regularization term to achieve high-resolution feature embedding by minimizing the intra-class distance and maximizing the inter-class interval. The loss function is as follows:

Among them, \(\:f\left({x}_{i}\right)\) is the feature representation of the network output, \(\:{c}_{{y}_{i}}\) and \(\:{c}_{j}\) are the center vectors of the correct category and other categories respectively, and \(\:\lambda\:\) is the weight of the adjustment item. By adding this constraint during the training process, the network can learn clearer category boundaries in the feature space, thereby effectively improving the recognition accuracy of complex lubrication conditions.

Experiment

Apparatus

The experimental setup is depicted in Fig. 3. Figure 3 (a) presents the schematic diagram of the experiment device, while Fig. 3 (c) shows the actual image of the Bruker UMT-3 tester. This commercial equipment is capable of precisely controlling the rotational speed of the disk and the applied load. The frictional force was measured by the built-in sensors of the apparatus. To acquire the vibration signals, a triaxial acceleration sensor (model 356B17ICP, manufactured by PCB PIEZOTRONICS Company) was affixed to the pin specimen. This sensor has a measurement range of ± 5 g and a sensitivity of 1000mv/g. The data acquisition was carried out using a data acquisition system (VibPilot, m + p international).

As shown in Fig. 3 (b) and Fig. 3 (d), the pin-disk specimen was selected as the tribological pairs for the lubricant states test. The pin sample, fabricated from 416 stainless steel with a hardness of 38HRC, a diameter of Ø6.35 mm, and a surface roughness of Sa = 2.326 μm, is characterized by a martensitic structure and is primarily composed of elements such as Fe, C, Si, Cr, P, Mn, and S. The disk sample, made of E52100 steel with a hardness of 63HRC, a diameter of Ø70mm, and a surface roughness of Sa = 0.936 μm, exhibits a tempered martensitic structure and mainly consists of elements including Fe, C, Si, P, Mn, Cr, Ni, and Cu.

Methods

The experiments were conducted under ambient conditions with a relative humidity of 43% and a temperature of 293 K. The disc was subjected to a loading force of 45 N and rotated at a speed of 120RPM. The diameter of the contact track on the disc sample was measured to be 60 mm. Great Wall L-CKT220 lubricant, which exhibits excellent extreme pressure performance, wear resistance protection ability, extremely high thermal and oxidation stability, as well as rust and corrosion resistance, was employed. At 40℃, its kinematic viscosity was determined to be 215.18 mm²/s. The contact area between the pin and the disc was submerged in an oil bath. The experiment had a duration of 30 min, during which the vibration signals were collected by a triaxial acceleration sensor with a sampling frequency of 5120 Hz.

As presented in Table 1, three lubrication states were investigated: normal lubrication (NL), insufficient lubrication (IL), and lubricant contamination (LC). For the NL state, 10 ml of the lubricating oil was utilized as the lubrication medium. The friction pair operates in a fully developed elastohydrodynamic lubrication regime with stable oil film separation. In the IL state, 5 ml of pure water was thoroughly mixed and stirred with 5 ml of the lubricating oil to form the lubrication medium. It transitions to boundary lubrication regime with direct metal-to-metal contact. In the LC state, 2 g of ferromagnetic particles were completely blended with 10 ml of the lubricating oil and homogenized to serve as the lubrication medium. A mixed lubrication regime with third-body wear occurs due to particulate entrainment. The choice of these lubrication states is representative of common issues in real-world mechanical systems. Insufficient lubrication and lubricant contamination are two major problems that can lead to equipment failure, and studying these states can provide valuable insights into lubrication state identification.

Experimental results and analysis

Results of CWT

The vibration signals corresponding to different lubrication states were processed using CWT, and the resultant time-frequency diagrams are presented in Fig. 4. A detailed examination of these diagrams reveals distinct differences in the time-frequency characteristics of the vibration signals under varying lubrication conditions.

As shown in Fig. 4(b), in the case of normal lubrication, the energy distribution of the vibration signals across the time-frequency domain is relatively homogenous. This even distribution indicates that the lubricant is effectively fulfilling its function of reducing friction and minimizing vibrations. The absence of obvious abnormal peaks implies a stable lubrication regime, where the mechanical components are operating smoothly without any significant interference. Under the condition of sufficient oil supply, the friction pair is separated by continuous oil films, forming an elastohydrodynamic lubrication state. The damping effect of the oil film suppresses high-frequency vibrations, resulting in the uniform distribution of vibration energy in the time-frequency domain. This is in line with the low-friction vibration characteristics of the fluid lubrication zone in the classic Stribeck curve.

As shown in Fig. 4(d), when it comes to insufficient lubrication, the energy in the high-frequency band of the vibration signals experiences a notable increase. This is because the reduced amount of lubricant leads to increased friction between the tribological pairs. As the surfaces come into closer contact and interact more harshly, higher-frequency vibrations are generated. These vibrations manifest as abnormal peaks in the time - frequency diagram. When the volume of the lubricant decreases by 50%, the thickness of the oil film drops below the critical value, and the friction pair enters the boundary lubrication state23. At this point, the contact between the micro-ridges intensifies, triggering transient stress fluctuations, which manifest as concentrated high-frequency vibration energy. This is consistent with Serratto’s discovery: the RMS value of high-frequency vibration is positively correlated with the reduction in oil film thicknes10.

As shown in Fig. 4(f), for lubricant contamination, the time-frequency diagram exhibits complex frequency modulation and amplitude modulation characteristics. Contaminants in the lubricant disrupt the normal lubricating film between the surfaces. This disruption leads to irregular contact and interaction between the mechanical components, resulting in complex vibration patterns. The frequency modulation occurs as the contaminants cause intermittent changes in the vibration frequencies, while the amplitude modulation is a consequence of the varying levels of interference caused by the contaminants. The introduction of hard particles leads to tribo-mechanical wear24. The random inclusion of particles in the contact area causes local rupture of the oil film, resulting in non-stationary impact vibrations. This mechanism is manifested as a complex amplitude-frequency modulation phenomenon in the time-frequency domain, and its modulation frequency is related to the particle size distribution.

These distinct differences in time-frequency characteristics serve as a crucial foundation for the subsequent identification of lubrication states by the CNN. The unique patterns associated with each lubrication state provide discriminative features that the CNN can learn and utilize for accurate classification.

Training and validation results of CNN

The division of the dataset into training and validation sets is outlined in Table 2. A total of 780 sample data points were utilized, with each individual sample having a length of 2048 data points. This sample length was carefully selected based on prior research and preliminary experiments, which indicated that it could capture the essential characteristics of the vibration signals related to different lubrication states25. Each of the three lubrication states was represented by 260 samples.

The CNN model employed in this experiment consists of three convolutional layers. The first convolutional layer is equipped with 32 convolutional kernels, each with a size of 3 × 3. These kernels are designed to detect low-level features in the input time-frequency diagrams, such as small-scale patterns and edges. The second convolutional layer has 64 convolutional kernels of the same size, which further extract more complex features by aggregating the information from the first layer. The third convolutional layer, with 128 convolutional kernels, is responsible for capturing the most intricate and high-level features specific to each lubrication state.

Max pooling with a pooling size of 2 × 2 was used as the pooling method. This pooling operation reduces the dimensionality of the data while retaining the most important features. By selecting the maximum value within each pooling region, the model can focus on the most prominent features and discard less significant information, thereby reducing the computational load and preventing overfitting.

The ReLU activation function was chosen for the convolutional layers. ReLU not only introduces non-linearity into the model, enabling it to learn complex relationships in the data, but also helps to mitigate the problem of gradient vanishing26. This ensures that the model can be trained effectively and converge to an optimal solution.

Following the convolutional layers, two fully connected layers were incorporated. The first fully connected layer, with 128 neurons, serves as an intermediate layer that further processes the features extracted by the convolutional layers. It combines and transforms these features to make them more suitable for the final classification task. The second fully connected layer has the number of neurons equal to the number of lubrication states to be classified. This layer maps the processed features to the output space, where the Softmax activation function in the output layer is applied for multi-class classification. The Softmax function converts the raw output values into probability distributions, indicating the likelihood of each sample belonging to a particular lubrication state.

The Adam optimizer was selected for the training process27with a learning rate set to 0.001. The Adam optimizer adaptively adjusts the learning rate for each parameter, allowing for faster convergence and more stable training. The batch size was set to 32, which means that during each training iteration, 32 samples are used to compute the gradients and update the model’s parameters. This batch size was determined through a series of trial - and - error experiments, as it provided a good balance between computational efficiency and training accuracy. The number of training epochs was set to 120.

During the training process, the early-stopping method was implemented to prevent overfitting28. Overfitting occurs when the model starts to memorize the training data rather than learning the underlying patterns, resulting in poor generalization performance on new data. The early-stopping mechanism monitors the performance of the model on the validation set. If the performance, such as the validation accuracy or loss, does not improve for a certain number of consecutive epochs, the training process is terminated. This ensures that the model does not over-train and can generalize well to unseen data.

The training process of the CNN model using the training set and validation with the validation set is illustrated in Fig. 5. As the number of training epochs increases, the loss rate of the model gradually decreases, while the accuracy rate gradually increases. This trend indicates that the model is learning the features of the time-frequency diagrams of different lubrication states effectively. After approximately 90 epochs of training, the performance of the model on the validation set begins to stabilize. This stabilization implies that the model has reached a point where it has learned the relevant features and is no longer improving significantly. It also demonstrates the model’s good generalization ability, as it can perform well on data that it has not seen during training.

T-SNE visualization and result analysis

T-SNE (t-Distributed Stochastic Neighbor Embedding) is a powerful dimension reduction technique that is widely used to represent high-dimensional data in a two- or three-dimensional low-dimensional space, facilitating the visualization of high-dimensional data29. In this study, the features extracted by the CNN model were visualized using t-SNE, as depicted in Fig. 6.

The visualization results show that after the training of the CNN network, the discrimination between different types of data corresponding to various lubrication states is significantly enhanced. In the t-SNE plot, the data points representing different lubrication states are clearly separated from each other. This separation indicates that the CNN has successfully learned to distinguish the unique features of each lubrication state from the time-frequency diagrams. For example, the data points for normal lubrication form a distinct cluster, separate from those of insufficient lubrication and lubricant contamination. This clear discrimination is a strong indication of the model’s good robustness. Even in the presence of noise or minor variations in the data, the model can still accurately classify the lubrication states based on the learned features.

In order to further evaluate the classification performance of the model, the test set is used for testing, and the test results are presented by using the confusion matrix. The confusion matrix provides a detailed breakdown of the classification results for each type of lubrication state, showing the proportion of correctly and incorrectly classified samples. The confusion matrix is presented in Fig. 7. The results from the confusion matrix are remarkable, with a recognition rate of 100% for samples in each lubrication state. This perfect recognition rate indicates that the proposed method has an excellent ability to accurately identify different lubrication states. It implies that the combination of CWT for feature extraction and CNN for classification is highly effective. The model can correctly classify all the samples in the test set, demonstrating its high precision and reliability.

The t-SNE visualization and confusion matrix results provide complementary evidence for the effectiveness of the proposed method. The clear separation in the t-SNE plot shows that the model can capture the distinct features of different lubrication states, while the 100% accuracy in the confusion matrix verifies the model’s ability to classify samples correctly. Together, these results not only validate the performance of the proposed method but also provide insights into how the model is learning and classifying the data.

Comparison with traditional methods

To comprehensively demonstrate the superiority of the proposed CWT + CNN approach, a rigorous comparison was made with traditional vibration analysis methods. The traditional methods included calculating the root mean square (RMS)10 value of the vibration signal to measure time - domain fluctuations and determining the power spectral density (PSD)30 of the vibration signal to analyze frequency - based characteristics.

The RMS value provides an overall measure of the magnitude of the vibration signal in the time domain. It can give an indication of the overall intensity of the vibrations but may not capture the detailed characteristics related to different lubrication states. The PSD, on the other hand, shows the distribution of power across different frequencies, which can help identify dominant frequencies in the vibration signal. However, these traditional methods lack the ability to capture the complex time-frequency relationships that are crucial for accurate lubrication state identification.

The comparison results presented in Table 3 clearly illustrate the overwhelming advantages of the proposed CWT + CNN method in lubrication state identification. The CWT + CNN method achieved an impressive 99.8% recognition rate on the training set and a perfect 100% recognition rate on the test set. These high recognition rates indicate excellent training performance and strong generalization ability. The model can not only learn the patterns in the training data effectively but also accurately classify new, unseen data.

In contrast, other methods such as RMS + CNN, PSD + CNN, and CWT + SVM showed significantly lower recognition rates. The RMS + CNN method achieved only 65.2% training and 63.8% test recognition rates, while the PSD + CNN method had 72.8% training and 73.4% test recognition rates. The CWT + SVM method, although better than RMS + CNN, still had relatively lower recognition rates of 78.5% training and 76.3% test.

The large differences in recognition rates between the proposed method and the traditional methods highlight the significantly enhanced efficacy, precision, and generalization capacity of the CWT + CNN method. The ability of CWT to extract detailed time-frequency features, combined with the powerful feature-learning and classification capabilities of CNN, enables the proposed method to outperform traditional vibration analysis methods. This makes the CWT + CNN method a more reliable and accurate solution for lubrication state identification in mechanical systems. It can provide more accurate and timely information for equipment maintenance and management, helping to prevent equipment failures and reduce production losses.

Finally, this paper also gives an anti-noise experiment. This paper adds Gaussian noise to the data and gives the experimental results under different Gaussian noises, as shown in Table 4.

From the experimental results, it can be seen that with the increase of noise intensity \(\:\sigma\:\), the recognition accuracy of the model on the training set and the test set shows a decrease to varying degrees, indicating that noise has a certain impact on the recognition performance. Under the noise-free condition, the model achieves a training accuracy of 99.8% and a test accuracy of 100%, indicating that it has extremely high recognition ability under ideal conditions. When the noise standard deviation increases to 0.1 and 0.2, the test accuracy drops to 97.5% and 94.1% respectively, but still maintains a high level, indicating that the model has good robustness. When the noise intensity further increases to 0.5, the test accuracy drops significantly to 88.6%, reflecting that high-intensity noise will interfere with the model’s ability to extract key features. This trend verifies that the model has a certain anti-interference ability in an actual industrial environment, and also reveals its performance bottleneck when facing high-intensity noise, suggesting that the robustness can be further improved by introducing an anti-noise enhancement mechanism in the future.

Conclusion

In this study, a lubrication state identification method based on continuous wavelet transform (CWT) and convolutional neural network (CNN) was proposed and validated. Under the tested conditions, our methodology reached 99.8% training accuracy and 100% test accuracy. This demonstrates the CWT-CNN framework’s efficacy in converting 1D vibration signals into time-frequency images for feature extraction and classification. This method provides a reliable tool for real-time condition monitoring and has potential for practical application in reducing equipment failures and production losses.

However, the current study is limited to evaluating lubricant contamination at discrete levels. While these results validate the model’s effectiveness for distinct states, its capacity to characterize continuous degradation processes—critical for predicting gradual wear or contamination progression—requires further investigation. Future work will prioritize addressing this limitation by incorporating datasets with graded contamination levels to model continuous degradation dynamics. Additional efforts will focus on parameter optimization, integration with advanced learning strategies, and cross-device generalization experiments to enhance the method’s universality. These steps aim to strengthen the model’s adaptability to real-world scenarios, where lubricant degradation often occurs incrementally across diverse operating conditions.

Data availability

The datasets used and analyzed within this study are not publicly available due to legal restrictions but are available from the corresponding author on reasonable request.

References

Zhang, A. S., Wang, J., Han, Y. M., Zhang, J. J. & Liu, Y. Effect of pin generatrix on the elastohydrodynamic lubrication performance of pin-bush pair in industrial roller chains. Proc. Institution Mech. Eng. Part. J-Journal Eng. Tribology. 236, 1545–1553. https://doi.org/10.1177/13506501211065954 (2022).

Wang, Y., Jacobs, G., Zhang, S., Klinghart, B. & Koenig, F. Lubrication mechanism analysis of textures in journal bearings using CFD simulations. Industrial Lubrication Tribology. 77, 2–14. https://doi.org/10.1108/ilt-01-2024-0031 (2025).

Sun, J. et al. Online oil debris monitoring of rotating machinery: A detailed review of more than three decades. Mech. Syst. Signal Process. 149 https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ymssp.2020.107341 (2021).

Pastukhov, A. G. & Timashov, E. P. Study of temperature mode of support bearing units of a car gearbox. Russian Eng. Research 44, 346–351 (2024).

Yu, H., Wei, H., Zhou, D., Li, J. & Liu, H. Reconstruction and information entropy analysis of frictional vibration signals in running-in progress. Industrial Lubrication Tribology. 73, 937–944. https://doi.org/10.1108/ilt-03-2021-0095 (2021).

Zhao, J. et al. Real-Time and online lubricating oil condition monitoring enabled by triboelectric nanogenerator. ACS Nano. 15, 11869–11879. https://doi.org/10.1021/acsnano.1c02980 (2021).

Chang, J., Liu, S. & Hu, X. A temperature measurement method for testing lubrication system or revealing scuffing failure mechanism of spur gear. Proc. Institution Mech. Eng. Part. J-Journal Eng. Tribology. 233, 831–840. https://doi.org/10.1177/1350650118799927 (2019).

Yu, H. & Wei, H. Information entropy analysis of frictional vibration under different wear States. Tribol. Trans. 65, 88–95. https://doi.org/10.1080/10402004.2021.1998739 (2021).

Zhang, X. et al. A Graph-Data-Based monitoring method of bearing lubrication using Multi-Sensor. Lubricants 12 https://doi.org/10.3390/lubricants12060229 (2024).

Serrato, R., Maru, M. M. & Padovese, L. R. Effect of lubricant viscosity grade on mechanical vibration of roller bearings. Tribol. Int. 40, 1270–1275 (2007).

Xu, X., Liao, X., Zhou, T., He, Z. & Hu, H. Vibration-based identification of lubrication starved bearing using spectral centroid indicator combined with minimum entropy Deconvolution. Measurement 226 https://doi.org/10.1016/j.measurement.2024.114156 (2024).

Tsunashima, H. in 26th Symposium of the International Association of Vehicle System Dynamics (IAVSD). 103–112 (2020).

Wang, T. et al. Automatic ECG classification using continuous wavelet transform and convolutional neural network. Entropy 23 https://doi.org/10.3390/e23010119 (2021).

Cheng, X. et al. Detection of rubber tree powdery mildew from leaf level hyperspectral data using continuous wavelet transform and machine learning[J]. Remote Sensing 16(1), 17. https://doi.org/10.3390/rs16010105 (2024).

Atwood, J. & Towsley, D. Diffusion-Convolutional neural networks. Computer Sci. https://doi.org/10.48550/arXiv.1511.02136 (2015).

Weifang, S. et al. An intelligent gear fault diagnosis methodology using a complex wavelet enhanced convolutional neural network. Materials 10, 790 (2017).

Gu, J., Peng, Y., Lu, H., Chang, X. & Chen, G. A novel fault diagnosis method of rotating machinery via VMD, CWT and improved CNN. Measurement 200. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.measurement.2022.111635(2022).

Han, D., Qi, H., Wang, S., Hou, D. & Wang, C. Adaptive stepsize forward–backward pursuit and acoustic emission-based health state assessment of high-speed train bearings. Struct. Health Monit. https://doi.org/10.1177/14759217241271036 (2024).

Ni, B., Song, F., Zhao, L., Fu, Z. & Huang, Y. Wavelet denoising of fiber optic monitoring signals in permafrost regions. Sci. Rep. 14, 9085. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-024-59941-4 (2024).

Mushtaq, S., Islam, M. M. M. & Sohaib, M. Deep learning aided Data-Driven fault diagnosis of rotatory machine: A comprehensive review. Energies 14 https://doi.org/10.3390/en14165150 (2021).

Zhang, W., Peng, G., Li, C., Chen, Y. & Zhang, Z. A. New deep learning model for fault diagnosis with good Anti-Noise and domain adaptation ability on Raw vibration signals. Sensors 17 https://doi.org/10.3390/s17020425 (2017).

Li, Y. & Yuan, Y. Convergence Analysis of Two-layer Neural Networks with ReLU Activation. (2017).

Farhat, M. H., Gelman, L., Conaghan, G., Kluis, W. & Ball, A. Novel diagnosis technologies for a lack of oil lubrication in gearmotor systems, based on motor current signature analysis. Sensors 22. https://doi.org/10.3390/s22239507 (2022).

Wu, G., Jiang, G. & Chen, P. B. An experimental study of the effects of cylinder lubricating oils on the vibration characteristics of a Two-Stroke Low-Speed marine diesel engine. Pol. Maritime Res. 30, 92–101 (2023).

Yu, H. J., Wei, H. J., Li, J. M. & Liu, H. Lubrication State Recognition Based on Energy Characteristics of Friction Vibration with EEMD and SVM. Hindawi (2021).

Li, Y., Lu, S., Mathe, P. P., Sergei, V. & Two-layer networks with the ReLU k activation function: Barron spaces and derivative approximation. Numer. Math. 156, 319–344 (2024).

Chiang, P. J. Adaptive penalty method with Adam optimizerfor enhanced convergence in optical waveguidemode solvers. Optics Express 31, 28065–28077. https://doi.org/10.1364/OE.495855 (2023).

Nguyen, M. H., Abbass, H. A. & Mckay, R. I. Stopping criteria for ensemble of evolutionary artificial neural networks. Appl. Soft Comput. 6, 100–107 (2006).

Laurens, V. D. M. & Hinton, G. Visualizing data using t-SNE. J. Mach. Learn. Res. 9, 2579–2605 (2008).

Carlos Gonçalves, A. & Rodrigues Padovese, L. Identification of lubricant contamination by biodiesel using vibration analysis and neural network. Industrial Lubrication Tribology. 64, 104–110. https://doi.org/10.1108/00368791211208714 (2012).

Acknowledgements

This research was supported by the High-level Talents Project of Hainan Tropical Ocean University (No.RHDRC202320), and the Major Science and Technology Program of Yazhou Bay Innovation Institute of Hainan Tropical Ocean University(No.2023CXYZD001).

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

Haijie Yu wrote the main manuscript text and prepared experiment, figures and tables. Haijun Wei revised the main manuscript.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher’s note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if you modified the licensed material. You do not have permission under this licence to share adapted material derived from this article or parts of it. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Yu, H., Wei, H. Lubrication state identification of vibration time-frequency characteristics based on CWT and CNN. Sci Rep 15, 28936 (2025). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-14593-w

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-14593-w