Abstract

Egyptian sweet marjoram leaves (ESML) are aromatic herbs long valued for their ability to enhance flavor and extend shelf life by inhibiting the autoxidation of food lipids. Despite their widespread use, limited research exists on how various drying techniques, air temperatures, and thin-layer thicknesses affect the drying behavior, mathematical modeling, effective moisture diffusivity (EMD), activation energy, and thermodynamic properties of ESML. This study addresses this gap by examining the drying characteristics of ESML using a hybrid solar drying system (HSDS) at three air temperatures (50, 60, and 70 °C) and three layer thicknesses (1, 2, and 3 cm), comparing with a conventional oven drying (OD). The findings revealed that HSDS at 70 °C with a 3 cm layer thickness achieved the highest equilibrium moisture content (EMC), while HSDS at the same temperature with a 1 cm layer thickness resulted in the shortest drying time, highest drying rate, and moisture ratio. Additionally, the highest activation energy was observed using HSDS at 70 °C and a 2 cm layer thickness. Notably, drying at 70 °C with a 1 cm layer thickness reduced drying time by 66.67% compared to drying at 50 °C for the same thickness. Nonlinear regression analysis of eleven thin-layer drying models identified Weibullian (I) and Midilli as the best-fitting models for HSDS and OD, respectively. The HSDS demonstrated comparable performance to the OD while utilizing solar energy as a renewable heat. These findings advance the knowledge of drying systems by demonstrating the effectiveness and sustainability of hybrid solar drying for preserving the quality and functional properties of medicinal and aromatic herbs like marjoram.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

There is a burgeoning interest in the exploration of natural antioxidants extracted from plants, largely influenced by the global shift toward the utilization of natural additives in food and cosmetic products1,2,3. Among the various sources of such antioxidants, herbs and spices represent significant avenues for research, particularly in terms of safety4,5. Sweet marjoram, a widely recognized culinary herb, has a cultivation history in Egypt that spans over three millennia, with Egypt currently accounting for approximately 90% of the global supply of this herb6. In the realm of traditional folk medicine, sweet marjoram has been employed in the form of herbal tea (infusion) to address a range of health issues, including asthma, colds, coughs, cramps, depression, dizziness, gastrointestinal disorders, hay fever, headaches, toothaches, sinus congestion, as well as acting as a diuretic and promoting menstruation7,8. The herb is composed of various bioactive compounds, including carnosic, oleanolic, and ursolic acids; cis-sabinene hydrate; flavonoids such as diosmetin, luteolin, and apigenin; hydrocarbons including P-cymene and γ-terpinene; phenolic glycosides like arbutin, methyl arbutin, vitexin, orientin, and thymonin; phenolic terpenoids such as thymol and carvacrol; tannins; sitosterol; and triacontane7,8,9,10. Moreover, sweet marjoram leaves, particularly when consumed as herbal tea, may function as an immunostimulant and aid in diminishing genotoxicity in patients undergoing chemotherapeutic treatments6. Freshly harvested spices and herbs are characterized by high MC and the presence of various microorganisms, necessitating immediate preservation to prevent biological deterioration due to their perishable nature11. Thermal drying represents the most widely employed, cost-effective method of post-harvest processing, effectively minimizing losses of these raw materials12,13. Furthermore, this process is crucial for mitigating potential safety hazards associated with toxin formation14,15.

Drying is one of the most ancient methods of food preservation and serves a vital function within the food industry16,17,18. The primary objective of this process is to reduce MC and water activity to safe levels, thereby extending product shelf life, minimizing packaging requirements, and lowering shipping weights19,20,21. Consequently, drying techniques are extensively employed for the dehydration of various food items, including vegetables, fruits, spices, herbs, and other products22,23,24,25. In contemporary markets, there is an increasing demand among consumers for processed foods that retain the original characteristics of fresh produce26,27. Therefore, it is imperative that the drying process is executed with precision to preserve the flavor, aroma, color, appearance, and nutritional value of the plants to the greatest extent possible28. Moreover, drying efficiency is an essential metric for assessing drying performance. This encompasses factors such as energy consumption, drying time, and drying rate, all of which are critical for optimizing the drying process in both quality and operational efficiency29.

Solar energy represents one of the most extensively utilized renewable energy sources for the drying of a variety of products, including fruits30,31 vegetable32,33,34,35,36 fish37,38,39,40,41 spices and herbs42,43,44,45 etc. The process of solar drying is both economical and sustainable, offering an environmentally friendly approach for agricultural products46,47,48. Solar drying methods can be categorized based on the utilization of solar energy into three primary groups: (a) direct solar drying, in which the product is directly exposed to solar radiation; (b) indirect solar drying, commonly referred to as convective solar drying; and (c) mixed mode or hybrid solar drying49,50,51,52,53. Furthermore, solar dryers can be classified into two principal categories: natural convection solar dryers and forced convection solar dryers53,54,55,56,57. From a structural perspective, solar dryers can be subdivided into three major types: greenhouse types, collector types, and heat pump-assisted types58,59.

Many previous studies were performed on drying the marjoram leaves, but all of them were focused on physicochemical properties only, such as AlJuhaimi et al.60studied the effect of drying methods on the antioxidant capacity and bioactive and phenolic constituents in the aerial parts of marjoram grown naturally in the Taurus mountains in the Mediterranean region. Ganash61 investigated the potential of using dried marjoram leaves as a green inhibitor to prevent steel from rusting in an acidic solution. Raghavan et al.62,63 studied the effect of drying methods on the flavor quality of marjoram. And Szwedziak et al.63 studied the influence of biological preparations and drying methods on the content of essential oils in basil and marjoram.

To our knowledge, no publications in the literature describe the effects of drying methods, drying temperatures, and thin layer thickness on mathematical modeling, EMD, activation energy, drying parameters, and thermodynamic properties of ESML. So, the current study aimed to use an indirect solar dryer integrated with control units for temperature, humidity, and electrical heater (HSDS) for drying ESML and compare the obtained results with another oven drying (OD) under different drying temperatures and thin layer thicknesses.

Materials and methods

Experimental procedures

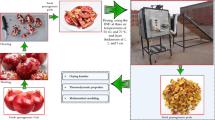

The fresh ESML (Origanum majorana L.) was collected from the Experimental Research Station, Faculty of Agriculture Farm, Moshtohor, Benha University. When initially harvested, the fresh ESML had an average MC of 82% (W.b.). Then, the fresh ESML was distributed at three-layer thicknesses of 1, 2, and 3 cm above the drying trays and put in the drying room. During the current study, two different drying systems were used for drying ESML: the first is a flat-plate solar dryer integrated with an electric heater (hybrid solar drying system (HSDS)), and the other is an oven drying (OD). Additionally, three drying system temperatures of 50, 60, and 70 °C and three-layer thicknesses of 1, 2, and 3 cm were established. To ensure uniform distribution and consistent drying conditions across all samples, drying molds with identical internal dimensions (30 cm in length, 20 cm in width, and 7 cm in height) were utilized. Based on the mold’s surface area and the bulk density of fresh marjoram leaves (0.15 g/cm³), 90 g of marjoram were evenly spread to achieve a layer thickness of approximately 1 cm. To prepare thicker layers, the sample weight was proportionally increased—180 g for a 2 cm layer and 270 g for a 3 cm layer—thereby maintaining uniform density and distribution across all tested thicknesses. The experimental design was split plot with three replicates. All tests on drying fresh ESML were done in the field at the Faculty of Agriculture Moshtohor, Benha University, Egypt, from summer 2022. These tests were done according to the rules set by International, National, and Benha University, which are in line with national and international laws and rules. During field tests, the average daily ambient air temperature, relative humidity, and solar radiation were 32.05 °C, 55.8%, and 640.05 W.h/m²/day, respectively. Where daily ambient air temperature, relative humidity, and solar radiation were recorded in Benha University, Egypt, from May to June 2022, and daily mean values were then calculated based on the obtained data. Figure 1 shows fresh and dried ESML.

Description of the HSDS

To achieve the objectives of the current study, a HSDS was designed, developed, and implemented. This system combines renewable solar energy with conventional electrical heating to provide an efficient and controllable drying environment. The HSDS is equipped with a Double Pass Flat Plate Solar Collector (DPFPSC), which functions as the primary solar heat source. Additionally, an auxiliary electric heater was integrated into the system to elevate and regulate the air temperature inside the drying chamber, particularly during periods of low solar radiation. The schematic layout of the developed HSDS is illustrated in Fig. 2a. The system comprises several key components:

-

I.

Double Pass Flat Plate Solar Collector (DPFPSC) (Fig. 2b): The collector measures 4 m in length, 1 m in width, and 20 centimeters in depth. It is covered with a 3 mm thick transparent glass sheet to minimize heat loss while allowing maximum solar radiation transmission. The internal absorber plate is made of corrugated black-painted aluminum, selected for its high thermal conductivity and efficient heat absorption. The absorber is thermally insulated using a 5 cm thick layer of thermal wool to minimize heat dissipation.

-

II.

Drying Chamber: The drying chamber, which serves as the core of the drying process, has cubic dimensions of 1.0 × 1.0 × 1.0 m. Both its inner and outer walls are constructed from 5 mm thick galvanized steel to ensure durability and resistance to corrosion. Thermal insulation is achieved through a composite of 2 cm thick thermal wool and 3 cm of foam, reducing heat losses and maintaining a stable internal temperature.

-

III.

Drying Boxes (Fig. 3a): The drying chamber contains multiple drying boxes, each fabricated from stainless steel to ensure hygiene and corrosion resistance. These boxes measure 30 cm in length, 20 cm in width, and 7 cm in height. Their perforated bottoms allow for uniform airflow distribution through the drying material, thereby enhancing drying efficiency.

-

IV.

Rotary Trays (Fig. 3a): To promote uniform drying and maximize contact between the hot air and the drying product, the chamber includes two rotary trays (shown in Fig. 3a). Each tray has a diameter of 60 cm and a height of 3 cm and is mounted on a centrally pivoted rotating axis, allowing for continuous motion and even heat exposure.

-

V.

Electric Heater (Fig. 3a): A 2000 W electric heater is installed as a supplementary heat source. It assists in elevating the air temperature, particularly during periods of insufficient solar energy, and helps in reducing the relative humidity of the circulating air. This accelerates the drying process and significantly reduces the total drying time.

-

VI.

Air Fans (Fig. 3a): Two high-performance air fans (Model C.C.P. Parm, Italy) are used in the system. These fans, each rated at 150 W with a capacity of 6.6 m³/h and a speed of 2800 rpm, are responsible for pushing heated air from the DPFPSC into the drying chamber and maintaining consistent air circulation within the chamber.

-

VII.

Control system (Fig. 3b): In this study, two distinct control systems were employed to regulate the drying environment. The first system utilized a digital PID controller (Model: REX_C100), which was responsible for modulating the air temperature and relative humidity inside the drying chamber. This was achieved by controlling both the electrical heater and the circulation fan speed, ensuring precise environmental conditions for the drying process. The second control system managed the operation of the inlet and exhaust air fans, automatically adjusting their activation to help maintain the target temperature and humidity levels within the chamber. Together, these systems provided coordinated and stable control over the internal drying conditions, thereby enhancing drying efficiency and product quality.

This hybrid configuration allows for a reliable and energy-efficient drying operation, optimizing the use of renewable solar energy while ensuring performance consistency through electrical backup.

Description of the oven drying (OD)

The drying chamber of the Hybrid Solar Drying System (HSDS) was repurposed as a conventional oven by utilizing only the electric heater, effectively isolating it from the solar component. This configuration was achieved by disengaging the intake fan connected to the solar collector and implementing a sealing gate mechanism to block the entry of hot air generated by solar radiation. As a result, heat was supplied exclusively through the electric heater, ensuring controlled and uniform temperature conditions within the drying chamber without any influence from solar input. The system setup during this mode of operation is illustrated in Fig. 3a.

Evaluations of the HSDS

Drying characteristics

Moisture content (MC)

The initial MC of the fresh ESML was estimated under laboratory conditions according to AOAC64. Additionally, during the drying of ESML in the field using both drying systems until reaching the EMC, the interval weight was measured hourly, and the MC (w.b.) was calculated using Eq. (1), as mentioned by Elghazali et al.65,66 and Eke et al.67.

where, \(\:{\text{W}}_{\text{w}}\:\text{a}\text{n}\text{d}\:{\text{W}}_{\text{d}}\) is the wet and dry weights of ESML samples.

Drying rate

The drying rate of different ESML samples were estimated using Eq. (2), as mentioned by Etim et al.68 and Ambawat et al.68 where Eq. (2), is the most widely used for estimating the drying rate because of its high accuracy.

Moisture ratio (MR)

The moisture ratio of dried ESML samples at time (t) were estimated using Eq. (3)69,54,55,56,57,

where, \(\:{M}_{0}\) is the initial MC in %, \(\:{M}_{e}\) is the EMC in %, and \(\:{M}_{t}\) is the MC at any time in %.

Effective moisture diffusivity (EMD)

Most drying studies widely recognize diffusion as the primary process that transports moisture to the surface for evaporation. The EMD can be calculated from the slope of the normalized plot of the unachieved moisture ratio, ln MR over time, utilizing the following Equation70,71.

where, Deff is the EMD in m2/s, and L is the half-thickness of n sample in m.

Finding the diffusion coefficient involves plotting experimental drying data in terms of ln (MR) versus time, s. The activation energy was also found using the law of Arrhenius, which is done in the same way as the diffusion coefficient72,73,74.

Mathematical modelling of the drying process

The drying data acquired were analyzed using nonlinear least squares regression to match eleven thin-layer drying models outlined in Table 1. Statistical analyses of the experimental data were conducted utilizing developed software produced by Öksüz and Buzrul75.

The coefficient of determination (R2, the adjusted coefficient of determination (\(\:{R}_{adj.}^{2}\)) and root mean squared error (RMSE) are fundamental criteria for selecting the optimal model to characterize the drying curves. The optimal model was identified based on the criterion of minimal RMSE values and maximal R2 and \(\:{R}_{adj.}^{2}\)82,83,84,85,86. The following Eqs. (6–8) can be employed to calculate these parameters.

where, MRexp, i is experimental MR; MRpre, i is predicted MR; N is number of observations; n is number of constants.

Thermodynamic properties

Drying is a critical unit operation in food, pharmaceutical, and agricultural industries, aimed at reducing the moisture content of materials to enhance shelf life, minimize microbial activity, and reduce weight for transport. While the kinetics of drying—such as moisture diffusivity and drying rate—have been extensively studied, understanding the thermodynamic properties associated with the drying process is equally vital. These properties provide insight into the energetic and molecular transformations that occur during moisture removal, enabling better design, control, and optimization of drying systems. The thermodynamic properties of particular interest in drying include enthalpy (ΔH), entropy (ΔS), and Gibbs free energy (ΔG). These parameters are typically derived from equilibrium moisture data and drying temperatures using the Clausius–Clapeyron equation and Gibbs–Helmholtz relation, and they help elucidate the nature of water binding and energy demands during the drying process. The thermodynamic properties related to the drying process of ESML were determined by following the methodology described by Jideani and Mpotokwana87 widely applied to several agricultural products (Eqs. 9–11).

The enthalpy change associated with the sorption process, also called the isosteric heat of sorption, represents the energy required to remove water molecules from the product surface. It is typically calculated using the Clausius–Clapeyron equation:

Entropy reflects the degree of disorder or randomness in the system. In drying, a positive ΔS implies that the transition from a bound water state to a vapor state increases system randomness, which is typical. The change in entropy is determined through:

Gibbs free energy indicates the spontaneity of the drying process. It is calculated using:

where ΔH is the enthalpy (J mol− 1), R is the universal gas constant (8.314 J mol− 1 K− 1), ΔS is the entropy (J mol− 1 K− 1), KB is the Boltzmann’s constant (1.38 × 10–23 J K− 1), Kp is the Planck’s constant (6.626 × 10− 34 J s− 1), ΔG is the Gibbs free energy (J mol− 1), D0 is the pre-exponential factor.

Practical implications

Understanding these thermodynamic properties has substantial practical value.

-

Energy Efficiency: Accurate enthalpy data help estimate the energy requirements of a drying system, allowing for the selection of optimal operating temperatures that minimize energy input.

-

Drying Behavior: Entropy changes can indicate how easily water molecules transition to vapor. For example, higher entropy at elevated temperatures suggests more disorder and faster drying.

-

Process Design and Control: Knowing whether a drying process is spontaneous (from ΔG) guides the selection of appropriate drying conditions or whether pre-treatments (e.g., salting, blanching) are needed to facilitate water removal.

-

Material Stability: The thermodynamic parameters can also signal potential quality changes, as excessive heat (linked to high ΔH) can degrade sensitive compounds in herbs, fruits, or pharmaceuticals.

In summary, thermodynamic analysis complements kinetic studies by offering a molecular-level understanding of water removal during drying. This deeper insight leads to improved system design, energy savings, and enhanced product quality.

Results and discussions

Drying characteristics

Some agricultural products lose a lot of weight, which hurts their quality and makes them less profitable. For example, they might lose shape or texture, or the color might turn bad88. The primary cause of weight loss is the process of leaching and diffusion when water-soluble elements such as vitamins, tastes, minerals, carbohydrates, sugars, and proteins are released from plant tissue into the surroundings89. The initial MC in different ESML samples on a wet basis before the drying process was 77.50%, while Fig. 4 shows the MC in different ESML samples on a wet basis due to changes in drying temperature, and layer thickness. The illustrated data in the same figure showed that the final MC and drying time of ESML did not significantly differ for both drying method, while the drying time of ESML was decreased with increasing the air temperature, where the longest drying time of ESML was observed at an air temperature of 50 °C and layer thickness of 3 cm, while the shortest drying time of ESML was observed at an air temperature of 70 °C and layer thickness of 1 cm, meaning that the weight loss increases with increasing power. Similar observations were observed by many researchers including Kidmose and Kaack90 and Wang et al.88. Additionally, different ESML samples dried in OD achieved EMC ranging between 1.75% and 2.04% (w.b.). While different ESML samples dried in HSDS achieved EMC ranging between 1.92% and 2.67% (w.b.). Where in the initial stage of the drying process, the water molecules on the surface of the leaves gain enough energy from heat to overcome intermolecular forces and escape into the surrounding air as vapor. As the surface moisture dries up, water molecules from deeper within the leaf structure need to migrate to the surface for evaporation. Water molecules within the leaf structure move from areas of higher concentration (inside the leaf cells) to areas of lower concentration (the leaf surface) through a process called diffusion. This diffusion process is slower than the initial surface evaporation, contributing to the decreasing drying rate over time. As the MC decreases, water molecules become more tightly bound to the plant tissues. This increases the energy required to remove them, further slowing down the drying process.

Figure 5 displays the relation between the moisture ratio and drying time curves of ESML at different drying air temperatures and layer thicknesses. The ESML was subjected to drying trials until they reached a state of EMC. Figure 5 demonstrates that raising the air temperature from 50 to 70 °C leads to a reduction in the time required for the finished product to dry by about 100%, 120%, and 71.4%, for layer thicknesses of 1 cm, 2 cm, and 3 cm, respectively, for OD, while the drying time was reduced by about 75%, 100%, and 71.4% for layer thicknesses of 1 cm, 2 cm, and 3 cm, respectively, for HSDS. This finding aligns with the outcomes reported by Beigi91 and Kaleta et al.92 where they found that, during the drying process, raising the air temperature from 50 to 60 °C resulted in enhanced mass transfer, decreased process duration, and lower energy usage93. Also, Kara and Doymaz’s93 reported that the increase in air temperature led to a decrease in the drying time. Additionally, Beigi91 observed that as the air temperature within the measured range rose, there was a corresponding rise in the quantity of moisture extracted from the product. Furthermore, we observed a drop in the MR curve as the hot air temperature increased, which aligns with the findings of Sharabiani et al.94. Where the inverse relationship between moisture ratio and drying time for ESML is a result of the decreasing moisture gradient within the ESML as drying progresses. This reduced gradient slows down the diffusion of water, leading to a longer drying time. Understanding this relationship is crucial for optimizing drying processes and preserving the quality of ESML.

Figure 6 shows the DR of different ESML samples at different layer thicknesses, drying air temperatures and drying methods with respect to time. Where obtained results showed that the initial drying rates of different ESML samples dried in OD ranged between 31.63 and 136.45 kg water/kg dry matter/h. While the initial drying rates of different ESML samples dried in HSDS ranged between 46.34 and 88.3 kg water/kg dry matter/h. Where the maximum drying rate recorded was 136.45 kg water/kg dry matter/h at a 1 mm layer thickness for the OD-dried samples, whereas the highest drying rate for the HSDS-dried samples was 88.3 kg water/kg dry matter/h at a 1 mm layer thickness. The MC of a leafy crop has a direct and significant impact on its drying rate. As the MC decreases, the drying rate generally slows down. This relationship can be visualized in a typical drying curve, as shown in Fig. 6. Where ESML typically has high initial MCs, about 77.50% (w.b.). This high MC facilitates rapid evaporation initially. In the initial stage, the drying rate is relatively constant. This is because the MC is high, and the surface of the crop is saturated with water. The drying rate is primarily controlled by external factors like air temperature, humidity, and airflow. As the drying progresses, the MC decreases, and the drying rate slows down. This is because the moisture within the ESML needs to migrate to the surface for evaporation. This internal diffusion becomes the rate-limiting step. Similar results were obtained by many researchers, such as Nassef et al.95Sobukola et al.96 and Madan et al.97.

Table 2 lists the drying coefficient (k) and determination coefficient (R2 for ESML at different drying temperatures and layer thicknesses for OD and HSDS. The tabulated results showed that the drying coefficient (k) increases, as the drying air temperature within both drying systems rises. Because higher drying temperatures lead to a higher vapor pressure of water within the ESML. This increased vapor pressure creates a larger driving force for water molecules to evaporate from the surface. Also, increase the kinetic energy of water molecules within the ESML. This increased kinetic energy results in faster diffusion of water molecules from the interior to the surface, where they can evaporate. On the other hand, the obtained results showed that, the drying coefficient generally decreases with increasing layer thickness. As the layer thickness increases, the distance that water molecules must travel from the interior of the ESML to the surface for evaporation also increases. This longer diffusion path leads to increased resistance to water movement and a slower drying rate. Also, thicker layers of ESML have a smaller surface area to volume ratio compared to thinner layers. This means a smaller portion of the ESML is directly exposed to the drying environment, limiting the rate of moisture removal. Additionally, in thicker layers of ESML, temperature gradients can develop within the ESML during drying. The outer surface of ESML may be significantly warmer than the inner core, leading to uneven drying and potentially hindering moisture removal from the interior. These findings conformed well to the comparable pattern observed in the drying rate data. Doymaz98 Kaleta et al.92 and Meziane99 had similar observations. According to the coefficient of determination, the tabulated data showed that it has a direct relation with layer thickness, while it has an inverse relation with drying temperature.

Effective moisture diffusivity (EMD)

Figure 7 illustrates the EMD of ESML at various drying temperatures and layer thicknesses. The EMD is influenced by the reduced distance that moisture must traverse before to evaporate into the surrounding atmosphere. Moisture gradients generated within the meal during the drying process induce strains in the cellular structure100. This may result in structural failure, causing alterations to the material’s volume, shape, or dimensions. The duration of moisture diffusion from the interior to the exterior of food is influenced by the rupture of cell walls101. This aspect must be incorporated into mathematical models to ensure accurate predictions of sample MC during drying or to determine the suitable EMD100. A variety of elements, such as the pre-treatment solution, air temperatures, and the properties of the dried materials, influenced the EMD53,102. Figure 7 illustrates the correlation between the natural logarithm of moisture rate and drying time, considering drying temperatures and thin layer thickness. The coefficient of determination (R²) ranges from 0.7896 to 0.936 for OD and from 0.7369 to 0.8828 for HSDS, allowing for further calculation of the slope. Figure 7 clearly illustrates that the natural logarithm of the moisture rate has a downward tendency, particularly at greater thickness, where higher temperatures correspond to a more rapid decline. Comparable results have also been documented in other studies regarding the drying dynamics of agricultural goods56,57,103.

Subsequently, EMD can be computed using Eq. (5) referenced above, and the results are depicted in Fig. 8. At a constant drying temperature, the EMD exhibited an upward trend as the thickness of the dry thin layer increased. Comparable detection was observed in expression at the same thin layer thickness, indicating that the water diffusion coefficient rises with an increase in temperature. At a drying temperature of 70 °C, the EMD for the 1.0, 2.0, and 3.0 cm layer thicknesses was 2.51 × 10− 9 m²·s⁻¹, 7.73 × 10− 9 m²·s⁻¹, and 14.1 × 10− 9 m²·s⁻¹, respectively, for the OD, and 2.50 × 10− 9 m²·s⁻¹, 7.67 × 10− 9 m²·s⁻¹, and 12 × 10− 9 m²·s⁻¹, respectively, for the HSDS. At a thickness of 1.0 cm, the maximum EMD was seen at a drying temperature of 70 °C, while the smallest EMD occurred at a drying temperature of 50 °C. Consequently, it can be inferred that augmenting the thickness and drying temperature of the thin layer enhances the internal pressure of the layer and elevates the activity of water molecules within the material, thereby facilitating moisture diffusion and subsequently improving the drying rate. This conclusion was corroborated by prior experiments on carrot slices104tea105 basil leaves57 and red sorghum106. Table 3 shows a comparison between the obtained EMD with previous studies.

Activation energy

The activation energy can be computed using a method analogous to that employed for determining EMD. Utilized the EMD values collected previously to construct linear correlations with the inverse of the absolute drying temperature data, as illustrated in Fig. 9.

Consequently, the activation energy is ascertained by calculating the slope of the linear correlations depicted in Fig. 10. Figure 10 illustrates that in this investigation, the activation energy values for thicknesses of 1.0, 2.0, and 3.0 cm were 31.95 kJ mol⁻¹, 34.64 kJ mol⁻¹, and 27.68 kJ mol⁻¹, respectively, for the OD, and 32.68 kJ mol⁻¹, 41.9 kJ mol⁻¹, and 27.35 kJ mol⁻¹, respectively, for the HSDS. The findings of this investigation are deemed plausible, supported by several pertinent literature sources indicating that the activation energy of vegetables and other plant-based materials ranges from 12.7 to 110 kJ mol⁻¹. Simultaneously, Luthra and Sadaka indicated that there is no substantial correlation between the augmentation of grain layer thickness and activation energy, which also elucidates the finding that the activation energy of moisture does not exhibit a definitive correlation with drying temperature and thickness observed in this study107. Moreover, these findings closely align with those reported by Shahi et al.108 who employed sun and vacuum dryers to dehydrate basil leaves at air temperatures of 45, 55, and 65 °C, indicating that the activation energy varied from 38.54 to 20.32 kJ mol⁻¹. Moreover, Martins et al.109 reported that the activation energy of basil leaves is 39.63 kJ mol⁻¹. Mbegbu et al.110 investigated the influence of varying air temperatures (30–70 °C) on the activation energy of lemon basil leaves utilizing a vacuum oven drier. They reported that the activation energy was 32.34 kJ·mol⁻¹.

Mathematical modeling

Table 4 shows the mathematical model constants and statistical parameters of OD and HSDS for ESML under different drying air temperatures and layer thicknesses. Where eleven mathematical models were used to study the drying kinetics of ESML. In the beginning, the data of the MC of different dried samples was observed at different drying air temperatures and layer thicknesses. Then, the MC was converted into the moisture ratio expression using Eq. (3), and eleven mathematical models were used to compute curve fitting. Choosing an appropriate mathematical model is essential for precisely forecasting the drying characteristics of different items111. Nevertheless, the choice of the most suitable mathematical model for characterizing the drying characteristics of spices and herbs can’t exclusively rely on the quantity of constants. The selection procedure must be driven by statistical indications that have proven effective in choosing appropriate drying models, as documented in the literature.

Hence, it’s crucial to meticulously evaluate these statistical indicators when choosing a mathematical model, guaranteeing that the mathematical model selection is based on well-informed decisions and supported by actual data. The findings of different statistical analysis, which are shown in Table 5, show that all drying kinetics had an overall high R2and \(\:{R}_{adj.}^{2}\), and low RMSE, which are examples of statistical measures that were used to assess the quality of the fitted models. Many researchers demonstrated that the mathematical model most suited for defining the thin layer drying was the one with the greatest R2and \(\:{R}_{adj.}^{2}\), and low RMSE values82,83,84. In addition, all eleven basic mathematical models were applied to predict the drying behavior of ESML during the drying process, where the Weibullian (I) drying model was the best models to represent the drying kinetics of ESML for OD, while the Midilli drying model was the best model to represent the drying kinetics of ESML for HSDS (Table 5; Figs. 11 and 12).

Thermodynamic properties

Table 6 presents the thermodynamic parameters (enthalpy, entropy, and Gibbs free energy) of OD and HSDS for ESML at various drying temperatures and layer thicknesses. The tabulated data indicated the values of enthalpy, entropy, and Gibbs free energy at various drying temperatures. As drying temperature rises, enthalpy and entropy diminish, however Gibbs free energy escalates. Enthalpy pertains to the energy required to eliminate the water associated with dry matter during drying, thereby decreasing with elevated drying temperatures112,113. Low enthalpy values at reduced temperatures signify an increased energy demand for the drying of tamarind seeds; analogous behavior was noted in the drying processes of Baru fruits examined by Resende et al.114 Bode pepper grains investigated by Rodovalho et al.115and tamarind seeds analyzed by Ferreira Junior et al.116. Entropy values (Table 6) diminish as drying temperature rises, as elevated temperatures significantly enhance the excitation of the product’s water molecules relative to lower temperatures, hence reducing the order of the water-product system116,117. Entropy, a thermodynamic property linked to the level of disorder between water and the product116,118 exhibits decreasing values with rising drying temperatures. Negative entropy values are ascribed to the presence of chemical adsorption and/or structural alterations of the adsorbent119. Positive Gibbs free energy values (Table 6) signify an endergonic reaction, necessitating the addition of energy to the air for the product’s drying process to transpire 112. Similar trends have been noted in studies113,120,121.

Conclusion

In this research, Egyptian sweet marjoram leaves (ESML) were dried using a hybrid solar drying system (HSDS) at three different temperatures of 50, 60, and 70 °C and three different layer thicknesses of 1, 2, and 3 cm. Then, the OD was used to compare the performance of the drying process with the HSDS in terms of drying characteristics, effective moisture diffusivity (EMD), mathematical modeling, activation energy, and thermodynamic properties. During the drying process, the MC reduced readings from an average MC of 77.50% to equilibrium moisture content of 1.95% and 2.15% (w.b.) for OD and HSDS, respectively. On the other hand, raising the air temperature from 50 to 70 °C leads to a reduction in the time required for the finished product to dry by about 100%, 120%, and 71.4% for layer thicknesses of 1 cm, 2 cm, and 3 cm, respectively, for OD, while the drying time was reduced by about 75%, 100%, and 71.4% for layer thicknesses of 1 cm, 2 cm, and 3 cm, respectively, for HSDS. Additionally, the EMD increases with increasing temperature and layer thickness. And the highest EMDs were 14.1 × 10− 9 m2 s− 1, and 12 × 10− 9 m2 s− 1 for the OD and HSDS, respectively. They were observed at a 70 °C drying temperature and a 3 cm layer thickness. The activation energy values for the thickness of 1.0, 2.0, and 3.0 cm ranged between 27.68 and 34.64 kJ.mol-1 and 27.35–41.9 kJ.mol-1, respectively. In addition, Weibullian (I) and Midilli were the best mathematical models to show how ESML dried for OD and HSDS, respectively. Moreover, results showed that with the increase in drying temperature, enthalpy and entropy decreased, while Gibbs free energy increased.

Future work

Future studies should focus on investigating the comparative effects of oven drying and hybrid solar drying on the physical, chemical, and quality attributes of marjoram. This includes assessing changes in essential oil content, color, texture, antioxidant activity, and overall sensory properties to determine the most efficient and quality-preserving drying method.

Practical applications

Dried Egyptian sweet marjoram leaves are widely used for their aromatic, medicinal, and preservative properties. They enhance food flavor, support digestive and respiratory health in herbal remedies, and exhibit antioxidant and antimicrobial effects. Their practical applications span culinary, pharmaceutical, and cosmetic industries, offering natural, functional ingredients with extended shelf life.

Data availability

All data is provided within the article.

References

Elwakeel, A. E. et al. Quality evaluation of dried tomato fruit and optimization of drying conditions using a modified solar dryer integrated with an automatic solar collector tracker. Sci. Rep. 15, 7659 (2025).

Sunil Kumar, T. et al. Residual effect of summer legumes incorporation on soil nutrient status and nutrient use efficiency of Kharif rice. Front Sustain. Food Syst 9, 153516 (2025).

Elwakeel, A. E. et al. Development, drying characteristics, and environmental analysis of a PV operated automatic solar dryer for drying date. Front Sustain. Food Syst 9, 1531601 (2025).

Lourenço, S. C., Moldão-Martins, M. & Alves, V. D. Antioxidants of natural plant origins: from sources to food industry applications. Molecules 24, 4132 (2019).

Gulcin, İ. Antioxidants and antioxidant methods: an updated overview. Arch. Toxicol. 94, 651–715 (2020).

Ramadan, G., El-Beih, N. M. & Zahra, M. M. Egyptian sweet marjoram leaves protect against genotoxicity, immunosuppression and other complications induced by cyclophosphamide in albino rats. Br. J. Nutr. 108, 1059–1068 (2012).

El-Ashmawy, I. M., El‐Nahas, A. F. & Salama, O. M. Protective effect of volatile oil, alcoholic and aqueous extracts of Origanum Majorana on lead acetate toxicity in mice. Basic. Clin. Pharmacol. Toxicol. 97, 238–243 (2005).

Ghaly, I. S., Said, A. & Abdel-Wahhab, M. A. Zizyphus Jujuba and Origanum Majorana extracts protect against hydroquinone-induced clastogenicity. Environ. Toxicol. Pharmacol. 25, 10–19 (2008).

Novak, J. et al. Ratios of cis-and trans-sabinene hydrate in Origanum Majorana L. and Origanum microphyllum (Bentham) Vogel. Biochem. Syst. Ecol. 28, 697–704 (2000).

Vagi, E. et al. Phenolic and triterpenoid antioxidants from Origanum Majorana L. herb and extracts obtained with different solvents. J. Agric. Food Chem. 53, 17–21 (2005).

Hordofa, T. S. & Tolossa, T. T. Cultivation and postharvest handling practices affecting yield and quality of major spices crops in ethiopia: A review. Cogent Food Agric. 6, 1788896 (2020).

Mansour, N. E. et al. Automated vacuum drying kinetics, thermodynamics, and economic analysis of Sage leaves. Sci. Rep. 15, 18779 (2025).

Farag Taha, M. et al. Emerging Technologies for Precision Crop Management Towards Agriculture 5.0: A Comprehensive Overview. 15, 582 (2025).

Parto, N. Case Study: Pathogens and SpicesPublic Health Ontario,. (2016).

Xie, L., Mujumdar, A. S., Xiao, H. W. & Gao, Z. J. Recent technologies and trends in medicinal herb drying. Preprint at (2015).

Jeevarathinam, G. et al. Infrared assisted hot air dryer for turmeric slices: effect on drying rate and quality parameters. Lwt 144, 111258 (2021).

Jayakumar, J. et al. Performance analysis of solar and heat pump dryer of small cardamom (Elettaria cardamomum Maton) using energy analysis, drying kinetics, and quality. Biomass Convers. Biorefin. 14, 20807–20821 (2024).

Jeevarathinam, G. et al. Design, development, and drying kinetics of infrared-assisted hot air dryer for turmeric slices. J. Food Process. Eng. 45, e13876 (2022).

Hamrouni-Sellami, I. et al. Total phenolics, flavonoids, and antioxidant activity of Sage (Salvia officinalis L.) plants as affected by different drying methods. Food Bioproc Tech. 6, 806–817 (2013).

Pirbalouti, A. G., Mahdad, E. & Craker, L. Effects of drying methods on qualitative and quantitative properties of essential oil of two Basil landraces. Food Chem. 141, 2440–2449 (2013).

Doymaz, İ. Drying characteristics and kinetics of Okra. J. Food Eng. 69, 275–279 (2005).

Wang, Y., Zhang, M., Mujumdar, A. S. & Mothibe, K. J. Microwave-assisted pulse-spouted bed freeze-drying of stem lettuce slices—Effect on product quality. Food Bioproc Tech. 6, 3530–3543 (2013).

Nathakaranakule, A., Jaiboon, P. & Soponronnarit, S. Far-infrared radiation assisted drying of Longan fruit. J. Food Eng. 100, 662–668 (2010).

Balasubramanian, S., Roselin, P., Singh, K. K., Zachariah, J. & Saxena, S. N. Postharvest processing and benefits of black pepper, coriander, cinnamon, fenugreek, and turmeric spices. Crit. Rev. Food Sci. Nutr. 56, 1585–1607 (2016).

Sa-Adchom, P., Swasdisevi, T., Nathakaranakule, A. & Soponronnarit, S. Drying kinetics using superheated steam and quality attributes of dried pork slices for different thickness, seasoning and fibers distribution. J. Food Eng. 104, 105–113 (2011).

Seerangurayar, T. et al. Experimental investigation and modeling of date drying under forced convection solar dryers. Biomass Convers. Biorefin. 14, 21705–21718 (2024).

Jeevarathinam, G. et al. Infrared-Assisted hot air drying of turmeric slices: effects on drying kinetics, quality, efficiency, energy considerations, and mathematical modeling. Heat. Transf. 54, 1965–2000 (2025).

Crivelli, G., Nani, R., Di Cesare, L. F. & Forni, E. Influence of processing on the quality of dried herbs [basil-oregano]. Atti VI Giornate Scientifiche SOI (Italy) 2, (2002).

Jin, W., Mujumdar, A. S., Zhang, M. & Shi, W. Novel Drying Techniques for Spices and Herbs: a Review. Food Engineering Reviews 10, 34–45 Preprint at https://doi.org/10.1007/s12393-017-9165-7 (2018).

Elghazali, M. N., Tawfeuk, H. Z., Gomaa, R. A., Abbas, A. A. & Aml, A. Effect of dehydration methods on physicochemical properties of Aswan Dry Dates. (2020).

Al-Ismaili, T. S. & Jeewantha, A. M. J. Al-Habsi, N. A. Effect of solar drying methods on color kinetics and texture of dates. Food Bioprod. Process. 116, 227–239 (2019).

Owureku-Asare, M. et al. Drying characteristics and microbiological quality assessment of solar-dried tomato. Int J Food Sci 2352327 (2022). (2022).

Zalewska, M., Marcinkowska-Lesiak, M. & Onopiuk, A. Application of different drying methods and their influence on the physicochemical properties of tomatoes. Eur. Food Res. Technol. 248, 2727–2735 (2022).

Ghoniem, E. Y. & Gamea, G. R. Design and evaluation of an enhanced solar dryer using heat storage unit for tomatoes drying. Misr J. Agricultural Eng. 31, 1025–1046 (2014).

Nabnean, S. et al. Experimental performance of a new design of solar dryer for drying osmotically dehydrated Cherry tomatoes. Renew. Energy. 94, 147–156 (2016).

Azam, M. M., Eltawil, M. A. & Amer, B. M. A. Thermal analysis of PV system and solar collector integrated with greenhouse dryer for drying tomatoes. Energy 212, 118764 (2020).

Mehta, P., Samaddar, S., Patel, P., Markam, B. & Maiti, S. Design and performance analysis of a mixed mode tent-type solar dryer for fish-drying in coastal areas. Sol. Energy. 170, 671–681 (2018).

Rizal, T. & Muhammad, Z. Fabrication and testing of hybrid solar-biomass dryer for drying fish. Case stud. Therm. Eng. 12, 489–496 (2018).

Majumdar, B. C., Afrin, F., Rasul, M. G., Khan, M. & Shah, A. K. M. Comparative study of physical, chemical, Microbiological and sensory aspects of some sun dried fishes in Bangladesh. Brazilian J. Biol. Sci. 4, 323–331 (2017).

Moneim, A. O. et al. Fish drying using different drying methods at different temperatures for fish tilapia Nilotica (Oreochromis niloticus). 83, 115–120 (2021).

Hubackova, A., Kucerova, I., Chrun, R., Chaloupkova, P. & Banout, J. Development of solar drying model for selected Cambodian fish species. Scientific World Journal 2014. (2014).

Eltawil, M. A., Azam, M. M. & Alghannam, A. O. Energy analysis of hybrid solar tunnel dryer with PV system and solar collector for drying mint (MenthaViridis). J. Clean. Prod. 181, 352–364 (2018).

Akpinar, E. K. Drying of mint leaves in a solar dryer and under open sun : modelling, performance analyses. Energy Convers. Manag. 51, 2407–2418 (2010).

El-Sebaii, A. A. & Shalaby, S. M. Experimental investigation of an indirect-mode forced convection solar dryer for drying thymus and mint. Energy Convers. Manag. 74, 109–116 (2013).

Balakrishnan, M. et al. Design, development, and evaluation of rotary drum dryer for turmeric rhizomes (Curcuma longa L). J. Food Process. Eng. 45, e14052 (2022).

Sharma, M., Atheaya, D. & Kumar, A. Performance evaluation of indirect type domestic hybrid solar dryer for tomato drying: thermal, embodied, economical and quality analysis. Therm. Sci. Eng. Progress. 42, 101882 (2023).

Prakash, O. & Kumar, A. Solar Drying Technology: Concept, Design, Testing, Modeling, Economics, and Environment (Springer, 2017).

Okoro, O. I. & Madueme, T. C. Solar energy investments in a developing economy. Renew. Energy. 29, 1599–1610 (2004).

Sharma, A., Chen, C. R. & Lan, N. V. Solar-energy drying systems: A review. Renew. Sustain. Energy Rev. 13, 1185–1210 (2009).

VijayaVenkataRaman, S., Iniyan, S. & Goic, R. A review of solar drying technologies. Renew. Sustain. Energy Rev. 16, 2652–2670 (2012).

Sontakke, M. S. & Salve, S. P. Solar drying technologies: A review. Int. J. Eng. Sci. 4, 29–35 (2015).

El-Sebaii, A. A. & Shalaby, S. M. Solar drying of agricultural products: A review. Renew. Sustain. Energy Rev. 16, 37–43 (2012).

Elwakeel, A. E., Gameh, M. A., Eissa, A. S. & Mostafa, M. B. Recent advances in solar drying technology for tomato fruits: a comprehensive review. Int. J. Appl. Energy Syst. 6, 37–44 (2024).

Eissa, A. S., Gameh, M. A., Mostafa, M. B. & Elwakeel, A. E. Some engineering factors affecting utilization of solar energy in drying tomato fruits introduction. 5, 52–68 (2024).

Elwakeel, A. E. et al. Development and Techno-Economic analysis of a tracked indirect forced solar dryer integrated photovoltaic system for drying tomatoes. Sustainability 16, 7008 (2024).

Elwakeel, A. E. et al. Drying kinetics and thermo-environmental analysis of a PV-operated tracking indirect solar dryer for tomato slices. PLoS One. 19, e0306281 (2024).

Khater, E. S. G. et al. Assessment of a LPG hybrid solar dryer assisted with smart air circulation system for drying Basil leaves. Sci. Rep. 14, 23922 (2024).

El-Mesery, H. S. et al. Optimization of dried Garlic physicochemical properties using a self-organizing map and the development of an artificial intelligence prediction model. Sci. Rep. 15, 3105 (2025).

Elmessery, W. M. et al. Deep regression analysis for enhanced thermal control in photovoltaic energy systems. Sci. Rep. 14, 30600 (2024).

AlJuhaimi, F., Ahmed, M., Özcan, I. A., Uslu, M. M. & Karrar, E. N. Effect of drying methods on the antioxidant capacity and bioactive and phenolic constituents in the Aerial Parts of Marjoram (Origanum majorana L.) Grown Naturally in the Taurus Mountains in the Mediterranean Region. Processes 12, (2024).

Ganash, A. A. Theoretical and experimental studies of dried marjoram leaves extract as green inhibitor for corrosion protection of steel substrate in acidic solution. Chem. Eng. Commun. 205, 350–362 (2018).

Raghavan, B., Rao, L. J., Singh, M. & Abraham, K. O. Effect of drying methods on the flavour quality of marjoram (Oreganum Majorana L). Food/Nahrung 41, 159–161 (1997).

Szwedziak, K., Doleżal, P. & Dąbrowska-Molenda, M. Influence of Biological Preparations and Drying Method on the Content of Essential Oils in Basiland Marjoram®. Postępy Techniki Przetwórstwa Spożywczego 19–25 (2022).

Int, A. Official methods of analysis of AOAC Int. Preprint at (2007).

Elghazali, M. N. ; H. Z. T. R. A. G. and A. A. T. Effect Dehydration Methods Physicochemical Prop. Aswan Dry. Dates Introduction : 51, 50–64 (2020).

Elghazali, M. N. ; H. Z. T. R. A. G. and A. A. T Technological Stud. Aswan Dry. Dates Prod. After Dehydration Abstract : Introduction : 51, 32–49 (2020).

Eke, A., Ben, Simonyan, K., J. Development of small scale direct & mode passive solar dryers for effective drying of tomato. J. Appl. Agricultural Res. 6, 111–119 (2014).

Ambawat, S., Sharma, A. & Saini, R. K. Mathematical modeling of thin layer drying kinetics and moisture diffusivity study of pretreated Moringa Oleifera leaves using fluidized bed dryer. Processes 10, 2464 (2022).

Rabha, D. K., Muthukumar, P. & Somayaji, C. Experimental investigation of thin layer drying kinetics of ghost Chilli pepper (Capsicum Chinense Jacq.) dried in a forced convection solar tunnel dryer. Renew. Energy. 105, 583–589 (2017).

Elwakeel, A. E. et al. Thermodynamic evaluation, and economic analysis of a PVT-Based automated indirect solar dryer for date fruits. Sustainability 17, 4571 (2025).

Crank, J. The Mathematics Ofdiffusion (Oxford University Press, 1975).

Tagnamas, Z., Idlimam, A. & Lamharrar, A. Effect of microwave pretreatment on truffle solar drying from an energetic perspective. Food Front. 5, 994–1003 (2024).

Ghanem, T. H. M. et al. Thin-layer modeling, drying parameters, and techno-enviro-economic analysis of a solar dried salted tilapia fish fillets. Sci. Rep. 15, 5073 (2025).

Younis, O. S. et al. Drying characteristics, environmental and economic analysis of a solar dryer with evacuated tube solar collector for drying nile tilapia slices. Sci. Rep. 15, 9822 (2025).

Öksüz, H. B., Buzrul, S. & DrYFiT An excel freeware tool to describe thin layer drying of foods. J. Food Process. Eng. 47, e14748 (2024).

Buzrul, S. Reassessment of thin-layer drying models for foods: a critical short communication. Processes 10, 118 (2022).

Inyang, U. E., Oboh, I. O. & Etuk, B. R. Kinetic models for drying techniques—food materials. Adv. Chem. Eng. Sci. 8, 27 (2018).

Henderson, S. M. Progress in developing the thin layer drying equation. Trans. ASAE. 17, 1167–1168 (1974).

Inyang, U. E., Oboh, I. O. & Etuk, B. R. Kinetic models for drying Techniques —. Food Mater. 27–48. https://doi.org/10.4236/aces.2018.82003 (2018).

Buzrul, S. Reassessment of Thin-Layer Drying Models for Foods : Processes 10, (2022).

Ghazanfari, A., Emami, S., Tabil, L. G. & Panigrahi, S. Thin-layer drying of flax fiber: II. Modeling drying process using semi-theoretical and empirical models. Drying Technol. 24, 1637–1642 (2006).

Akpinar, E. K., Bicer, Y. & Cetinkaya, F. Modelling of thin layer drying of parsley leaves in a convective dryer and under open sun. J. Food Eng. 75, 308–315 (2006).

Akpinar, E. K. & Bicer, Y. Mathematical modeling and experimental study on thin layer drying of strawberry. International J. Food Engineering 2(1), (2006).

Midilli, A. & Kucuk, H. Mathematical modeling of thin layer drying of pistachio by using solar energy. Energy Convers. Manag. 44, 1111–1122 (2003).

Elwakeel, A. E., Elbeltagi, A., Salem, A. & Dewidar, A. Z. Optimized design and performance evaluation of a highly precise variable rate mis-planting and replanting potato electronic-metering mechanism. Front Plant. Sci 16, (2025).

Elwakeel, A. E., Elbeltagi, A., Dewidar, A. Z., Salem, A. & Abdeen, M. A. Development and laboratory evaluation of a novel IoT-based electric-driven metering system for high precision Garlic planter. PLoS One. 20, e0317203 (2025).

Jideani, V. A. & Mpotokwana, S. M. Modeling of water absorption of Botswana Bambara varieties using peleg’s equation. J. Food Eng. 92, 182–188 (2009).

Wang, J. et al. Effects of various blanching methods on weight loss, enzymes inactivation, phytochemical contents, antioxidant capacity, ultrastructure and drying kinetics of red bell pepper (Capsicum annuum L). Lwt 77, 337–347 (2017).

Mukherjee, S. & Chattopadhyay, P. K. Whirling bed blanching of potato cubes and its effects on product quality. J. Food Eng. 78, 52–60 (2007).

Kidmose, U. & Kaack, K. Changes in texture and nutritional quality of green asparagus spears (Asparagus officinalis L.) during microwave blanching and cryogenic freezing. Acta Agriculturae Scand. Sect. B-Plant Soil. Sci. 49, 110–116 (1999).

Beigi, M. Hot air drying of Apple slices: dehydration characteristics and quality assessment. Heat Mass Transf. 52, 1435–1442 (2016).

Kaleta, A., Górnicki, K., Winiczenko, R. & Chojnacka, A. Evaluation of drying models of Apple (var. Ligol) dried in a fluidized bed dryer. Energy Convers. Manag. 67, 179–185 (2013).

Kara, C. & Doymaz, İ. Effective moisture diffusivity determination and mathematical modelling of drying curves of Apple pomace. Heat Mass Transf. 51, 983–989 (2015).

Rasooli Sharabiani, V., Kaveh, M., Abdi, R., Szymanek, M. & Tanaś, W. Estimation of moisture ratio for Apple drying by convective and microwave methods using artificial neural network modeling. Sci. Rep. 11, 1–12 (2021).

Nassef, A. M., Rahman, S. M. A., Rezk, H. & Said, Z. ANFIS-based modelling and optimal operating parameter determination to enhance cocoa beans drying-rate. IEEE Access. 8, 45964–45973 (2020).

Sobukola, O. P., Dairo, O. U., Sanni, L. O., Odunewu, A. V. & Fafiolu, B. O. Thin layer drying process of some leafy vegetables under open sun. Food Sci. Technol. Int. 13, 35–40 (2007).

Madan, A., Pare, A. & Nanje Gowda, N. A. Mathematical modelling of thin-layer drying process of bamboo (Bambusa bambos) shoots at varying temperature. Res. Rev. J. Bot. 3, 1–9 (2014).

Doymaz, İ. Evaluation of some thin-layer drying models of persimmon slices (Diospyros Kaki L). Energy Convers. Manag. 56, 199–205 (2012).

Meziane, S. Drying kinetics of Olive pomace in a fluidized bed dryer. Energy Convers. Manag. 52, 1644–1649 (2011).

Touil, A., Chemkhi, S. & Zagrouba, F. Moisture diffusivity and shrinkage of fruit and cladode of Opuntia ficus-indica during infrared drying. Journal of food processing 2014, (2014).

Mayor, L. & Sereno, A. M. Modelling shrinkage during convective drying of food materials: a review. J. Food Eng. 61, 373–386 (2004).

Osman, I. Food and bioproducts processing drying characteristics of sweet Cherry. 9, 31–38 (2010).

Coşkun, S., Doymaz, İ., Tunçkal, C. & Erdoğan, S. Investigation of drying kinetics of tomato slices dried by using a closed loop heat pump dryer. Heat Mass Transf. 53, 1863–1871 (2017).

Susanti, D. Y., Sediawan, W. B., Fahrurrozi, M. & Hidayat, M. Foam-mat drying in the encapsulation of red sorghum extract: effects of Xanthan gum addition on foam properties and drying kinetics. J. Saudi Soc. Agricultural Sci. 20, 270–279 (2021).

Zeng, Z. et al. Analysis of drying characteristic, effective moisture diffusivity and energy, exergy and environment performance indicators during thin layer drying of tea in a convective-hot air dryer. Front Sustain. Food Syst 8, (2024).

Dehghannya, J., Pourahmad, M., Ghanbarzadeh, B. & Ghaffari, H. Heat and mass transfer enhancement during foam-mat drying process of lime juice: impact of convective hot air temperature. Int. J. Therm. Sci. 135, 30–43 (2019).

Luthra, K. & Sadaka, S. Energy and exergy analysis of rough rice drying in a fluidized bed and fixed bed with ambient air dehumidification. in ASABE Annual International Virtual Meeting 1 (American Society of Agricultural and Biological Engineers, 2021). 1 (American Society of Agricultural and Biological Engineers, 2021). (2021).

Shahi, N. C., Singh, A. & Kate, A. E. Activation energy kinetics in thin layer drying of Basil leaves. Int. J. Sci. Res. 3, 1836–1840 (2014).

Martins, P., Sbaite, P., Benites, C. & Maciel, M. Thermal characterization of orange, lemongrass, and basil essential oils. in International Conference on Chemical and Process Engineering 24, 463–468 (2011).

Mbegbu, N. N., Nwajinka, C. O. & Amaefule, D. O. Thin layer drying models and characteristics of scent leaves (Ocimum gratissimum) and lemon basil leaves (Ocimum africanum). Heliyon 7, (2021).

Metwally, K. A. et al. The mathematical modeling, diffusivity, energy, and Enviro-Economic analysis (MD3E) of an automatic solar dryer for drying date fruits. Sustainability 16, 3506 (2024).

De Oliveira, G. H. H., Corrêa, P. C., Araujo, E. F., Valente, D. S. M. & Botelho, F. M. Desorption isotherms and thermodynamic properties of sweet corn cultivars (Zea Mays L). Int. J. Food Sci. Technol. 45, 546–554 (2010).

Morais, M. F. et al. Modeling and thermodynamic properties of ‘bacaba’pulp drying. Revista Brasileira De Engenharia Agrícola E Ambiental. 23, 702–708 (2019).

Resende, O., de Oliveira, D. E. C. & Costa, L. M. Ferreira júnior, W. N. Drying kinetics of Baru fruits (Dipteryx Alata Vogel). Engenharia Agrícola. 38, 103–109 (2018).

Rodovalho, R. S., da Silva, H. W., Silva, I. L. & Rossetto, C. A. V. Cinética de secagem Dos Grãos de Pimenta bode. Global Sci. Technology 8, (2015).

Ferreira Junior, W. N. et al. Modeling and thermodynamic properties of the drying of tamarind (Tamarindus indica L.) seeds. Revista Brasileira De Engenharia Agrícola E Ambiental. 25, 37–43 (2020).

Corrêa, P. C., Oliveira, G. H. H., Botelho, F. M., Goneli, A. L. D. & Carvalho, F. M. Modelagem matemática e determinação Das propriedades termodinâmicas do café (Coffea Arabica L.) Durante o processo de secagem. Revista Ceres. 57, 595–601 (2010).

de Goneli, A. L. D., Correa, P. C., de Oliveira, G. H. H. & Botelho, F. M. Water desorption and thermodynamic properties of Okra seeds. Trans. ASABE. 53, 191–197 (2010).

Moreira, R., Chenlo, F., Torres, M. D. & Vallejo, N. Thermodynamic analysis of experimental sorption isotherms of Loquat and quince fruits. J. Food Eng. 88, 514–521 (2008).

Martins, E. A. S., Lage, E. Z., Goneli, A. L. D., Filho, H., Lopes, J. G. & C. P. & Drying kinetics of Serjania marginata Casar leaves/cinetica de secagem de folhas de Timbo (Serjania marginata Casar). Revista Brasileira De Engenharia Agrícola E Ambiental. 19, 238–245 (2015).

Araujo, W. D., Goneli, A. L. D., Corrêa, P. C., Filho, H., Martins, E. A. S. & C. P. & Modelagem matemática Da secagem Dos Frutos de Amendoim Em Camada Delgada. Revista Ciência Agronômica. 48, 448–457 (2017).

Acknowledgements

The authors extend their appreciation to Ongoing Research Funding program - Research Chairs (ORF-RC-2025-5521), King Saud University, Riyadh, Saudi Arabia.

Funding

Open access funding provided by University of Pécs. This research was funded by Ongoing Research Funding program - Research Chairs (ORF-RC-2025-5521), King Saud University, Riyadh, Saudi Arabia.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

Conceptualization, E.G.K., and A.H.B., methodology, E.G.K., A.H.B., A.E.E., and K.A.M., software, E.G.K., A.H.B., A.E.E., and K.A.M., formal analysis, A.E., A.S., A.Z.D., and A.M.O., investigation, A.E.E., K.A.M., and A.A.T.O., resources, A.E.E., K.A.M., and A.A.T.O., data curation, A.E.E., K.A.M., A.E., A.S., A.Z.D., and A.M.O., writing original draft, E.G.K., A.H.B., A.E.E., and K.A.M., writing-review and editing, E.G.K., A.H.B., A.E.E., A.S., and K.A.M., visualization, A.E.E., and K.A.M., supervision, E.G.K., A.H.B., A.E.E., and K.A.M., project administration, E.G.K., A.H.B., A.E.E., and K.A.M., funding, A.E., A.S., A.Z.D., and A.M.O., all authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Corresponding authors

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Institutional review board statement

Not applicable.

Informed consent

Not applicable.

Additional information

Publisher’s note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Khater, ES.G., Bahnasawy, A.H., Oraiath, A.A.T. et al. Comparative analysis of drying kinetics, diffusivity, and thermodynamic properties of hybrid solar and oven dryers for Egyptian sweet marjoram. Sci Rep 15, 30368 (2025). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-14663-z

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-14663-z

Keywords

This article is cited by

-

Interactive effects of soaking duration and drying temperature on the drying kinetics and proximate composition of tiger nuts (Cyperus esculentus L.)

European Food Research and Technology (2026)

-

Ultrasound-assisted osmotic dehydration pretreatment enhances drying kinetics, quality attributes, bioactive compounds, microstructure, FTIR profiles, and sensory properties of Litchi

Scientific Reports (2025)