Abstract

Norovirus is a highly contagious virus and the leading cause of acute gastroenteritis worldwide. The World Health Organization (WHO) estimates that approximately 685 million cases of norovirus infection occur each year, with around 200 million affecting children under the age of five. The impact of this virus is substantial, contributing to roughly 200,000 deaths annually—about 50,000 of which are among young children—mostly in low-income countries. In addition to the human toll, norovirus imposes a significant economic burden, with global costs reaching approximately $60 billion each year due to healthcare expenses and lost productivity. In this paper, we present a fractional-order mathematical analysis of the norovirus epidemic model, focusing on its transmission dynamics, incorporating memory effects. The total population, denoted as N(t), is categorized into four compartments: susceptible, exposed, infected, and recovered. We analytically derive the equilibrium points and the basic reproduction number of the model. Furthermore, we discuss the properties of positivity, boundedness, uniqueness, and existence to ensure the model’s validity. The non-linear model is linearized around its equilibrium points, and local stability is analyzed using the eigenvalues of the Jacobian matrix. In addition, global stability is examined using the Lyapunov function and LaSalle’s invariance principle. To validate the theoretical findings, a numerical scheme based on the GL-Non-Standard Finite Difference (NSFD) method is developed, which serves to verify the theoretical analysis of the norovirus epidemic model.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

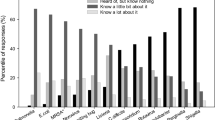

Norovirus is a highly contagious virus responsible for acute gastroenteritis, commonly causing outbreaks in highly dense areas like schools, hospitals, and other public places. Its impact is global, as it leads to millions of cases annually and represents a significant cause of foodborne illness. This makes Norovirus not only a major public health concern but also a significant topic for mathematical modeling, especially for those who focus on transmission dynamics. Norovirus was first identified in the 1970 s in Norwalk, Ohio, following a gastroenteritis outbreak in a school. Since then, it has been recognized as the leading cause of viral gastroenteritis worldwide. It spreads rapidly through direct contact, contaminated food or water, and infected surfaces. Norovirus is known for its“explosive”outbreak potential, as even a few viral particles are sufficient to infect a large number of susceptible. Norovirus can survive on surfaces for weeks, increasing the likelihood of secondary infections, and fractional-order models can represent the true behavior of the infection. Many infected individuals may be asymptomatic but infectious, and immunity after infection is generally short-term. These aspects make Norovirus a challenge for the health departments making it an appropriate case for fractional-order models. By studying Norovirus through a fractional-order epidemic model, we aim to provide insights into its transmission that can inform more effective control measures, as fractional derivatives capture the memory and hereditary properties inherent in the dynamics of infectious diseases. This approach offers a more comprehensive understanding of the virus’s spread, potentially leading to strategies that mitigate its impact in high-risk settings. In 1936 the norovirus was found in Roskilde (Denmark). The norovirus was termed a“Norwalk agent”This epidemic was found in some teenagers at Bronson Elementary School in the U.S.A. Moreover, it has different names like“Norwalk agent”, and“Norwalk virus”. In 2018, Gaythorpe et al. explored the stability in the representation of dynamical transmission of norovirus and evaluated the strength of parameters. They evaluated the stable variance in the basic reproduction number, which means that nowadays work needed to control norovirus may be reduced1. In 2019, Yang et al. described a segmented model to estimate the effect of population from different angles of observation. They concluded that 6.0 million cases of norovirus are prevented annually under the given scenario and 28% more cases might be avoided through 100% observance2. In 2018, Towers et al. analyzed a mathematical model of transmission of norovirus, by using this model they checked the comparative effectiveness of control strategies to lower the environmental or direct transfer of norovirus. They found that the outbreaks of norovirus might be avoided by promotion of good hand-washing practices and by isolating ill passengers3. In 2016, Chen et al. reported the interference of two norovirus epidemics, which focused on the significance of modeling based on verification and investigated the beginning of infection to prepare useful strategies. They found that only the closure of schools could not involve in norovirus outbreaks4. In 2018, Gaythorpe et al. introduced an age-specific and self-reporting Markov model to analyze the transmission and vaccination of norovirus with variation by age and time in Germany. The results revealed a reduction of norovirus incidence by 70.5% and strategies targeting infants and toddlers prevent infections efficiently but in older adults prevent severe infections5.

In 2016, Lopman et al. gathered a group of experts to evaluate the accountability of norovirus in the sense of globally and to check the possibility of making a vaccine for norovirus. The group estimated the area of cost of illness, hygiene, symptomatic, protection, and natural sensitivity. The group also examines how norovirus vaccines developed6. In 2016, Wang et al. introduced an artificial neural network model which is based on novel probability, to investigate the dangers of norovirus by using environmental predictors in harvesting areas of Mexico and the USA7. In 2016, Assab et al. studied a dynamics of norovirus outbreak between staff and residents8. Canales et al. proposed a two-dose–response assessment model for the prevalence of infectious disease and the contact path during the outbreak of the disease caused by norovirus9. In 2014, Shieh et al. examined the transfer of norovirus from infected to healthy tomatoes through a tomato slices in their eight sets of experiments using an 11-horizontal blade slicer10. In 2022 Wang et al. work aimed at investigating the stochastic model of noroviruses with temporal delay, including specific conditions regarding the persistence and the time of elimination of the pathogen11. In 2014, Bartsch et al. used an agent-based model to research the spread of the Norwalk virus between different hospitals in California by using contact and without contact precautions. The results revealed that reproductive rate of 1.64 and a spreading probability of 6.1% at the lower end and a reproductive rate of 3.74 and a spreading probability of 4.1–17.5% at the higher end. The results also revealed a reduction in the spreading of norovirus within hospitals and countrywide by using contact precautions12. In 2023, Raezah et al. selected a mathematical model to study the vaccination effect of norovirus by using the nonsingular operator. They also investigate the presence and exceptionality of solutions13. In 2017, Chenar et al. studied the effects of environmental factors on transmission of norovirus14. Kim et al. in 2022 investigated the replication of human norovirus (HuNoV) and the gene expression in infected zebrafish by performing three dosages of inoculation15.

In 2021, Calduch et al. studied the medical database and indirect modeling for judgment of the occurrence of hospitalization for norovirus gastroenteritis (NGE) by using patients discharged from different countries in Europe. The results revealed the rate of NGE with 3.9 per 10,000 persons, 24.8 per 10,000 children less than 5 years old, and 10.7 per 10,000 adults greater than 80 years old discharged from different hospitals in Europe per year16. In 2017, Matsuyama et al. studied the shard of norovirus eruption imputable to one living to be to other hauling has expanded with intervals, in addition, the scheduling of raised shard has corresponded with the rise in the noticed portion of genogroup. The efficacious duplication figure (\({R}_{y}\)), for annum \(y\) was assessed by examining the serial vigil calculation for spreading occurrences from 2000 to 201617. In 2021, O’Reilly et al. discussed non-pharmaceutical interventions (NPIs) to lessen the pandemic of coronavirus strain in England as well as other states that have ingrained other contagious ailments like norovirus. It is perplexing what forthcoming norovirus pandemic occurrences are inclined to be similar in hoisting all above referenced prohibitions18. In 2014, Lopman et al. studied the toxicity of norovirus is enacted. Nonetheless, norovirus is intermittently found in the manure of hearty personals. To attain a perceptive of the obvious prominent occurrence of symptom-free contagion, they evaluated a vigorous circulation sample of norovirus contagion ailment and protection. They anticipated yearly disease appearance values in infants19. In 2013, Simmons et al. discovered an analytical model to solve the problems caused by norovirus. They characterized their model by using previous investigations and data obtained from different age groups in two developed states England and Wales. If certain medications can boost the natural immunity indicated by our results, their capability to improve health and cost-effective benefits could be significant for the betterment of society20. In 2024, Kamal Shah et al. conducted an in-depth analysis of Nipah virus infection using piecewise equations in the fractional calculus framework. They proposed a SIRD-type model and assessed the solution’s feasibility based on fractional-order derivatives. Additionally, they provided numerical simulations for various compartments, employing the Runge–Kutta 4 (RK4) method. Their study also examined the transmission dynamics of the Nipah virus, utilizing new approaches in fractional calculus to enhance understanding of the disease spread21. The authors studied a finite-time stability analysis and control of stochastic SIR epidemic model: A study of COVID-19 in22. Several studies have employed fractional calculus to model complex disease dynamics, including dengue with non-linear incidence and pulse vaccination, Rift Valley fever with vaccination, water-borne disease with non-local kernels, breast cancer under chemotherapy, and chronic myelogenous leukemia—highlighting the effectiveness of fractional models in capturing memory effects in biological systems23,24,25,26,27,28. The authors studied the existence and stability results of Caputo fractional derivatives for boundary value problems involving both single and multivariable fractional orders in29,30,31. Raza and collaborators have applied stochastic fractional models to capture the complex dynamics of diseases like leukemia, Campylobacteriosis, and heroin addiction. Their work emphasizes memory effects and robust numerical schemes for accurate disease modeling32,33,34. Fractional calculus generalizes the traditional calculus which deals with the derivatives and integrals of non-integer or fractional order. Although it is as old as classical calculus, it has gained popularity in the recent past and now it is a significant area of study, especially for modelling complex real-world phenomena. It is now widely recognized that traditional integer-order models, which predict the behaviour of systems by their current states without considering the previous state capture the intricacies of certain dynamical systems, such as the spread of infectious diseases. In particular, the uncertain, nature of situations like the COVID-19 pandemic highlights the limitations of classical derivatives, which failed to address the non-linear behavior of the infection in these contexts. On the other hand, fractional epidemic models of COVID-19 illustrated all the complexities by providing realistic outcomes. Modeling scenarios with fractional derivatives have proven to be more accurate and representative of real-world processes than integer-order derivatives. The development of new fractional operators is made according the real-world problems. The fractional-order model captures norovirus’s memory effects, such as prolonged environmental persistence and short-term immunity. These features allow for a more realistic representation of reinfection risks and delayed transmission pathways.

Models developed through this extended finite difference approach-the GL-NSFD scheme fit closer to the qualitative features of the original system, including positivity, boundedness, and asymptotic stability. The GL-NSFD scheme guarantees an accurate determination of long-term behavior such as asymptotic properties of the system.

The framework of our paper is organized as follows: Section"Formulation of fractional norovirus epidemic model"introduces the mathematical model and provides its detailed analysis. The sub-sections focus on key aspects such as positivity, boundedness, stability analysis, existence, and uniqueness. Section “Numerical method” is dedicated to the numerical method, specifically NSFD, with sub-sections addressing the properties of the numerical method. This section also contains numerical simulations. Section “Conclusion” presents the final concluding remarks.

Now, we will provide some fundamental definitions.

Definition 1

Caputo fractional derivative.

Let \(g(t)\) be a function, then the Caputo derivative of \(g\left(t\right)\) of fractional order \({\varvec{\upzeta}}\) is defined as:

Where \(n-1<{\varvec{\upzeta}}<n\in {\mathbb{N}},\)

Also, its Laplace transformation can be defined as:

Definition 2

The mittag–leffler function.

Two parametric Mittag–Leffler function is defined as:

Its Laplace transformation can be defined as:

Formulation of fractional norovirus epidemic model

The whole population is represented by \(N(t)\) which can be further divided into four compartments. \(S(t)\) denotes the susceptible individuals, \(E(t)\) represents the exposed populations, \(I(t)\) contains the infected population and \(R(t)\) is the recovered population.(See Fig. 1.)

So, the entire population at the time \(t\) is like, \(N\left(t\right)=S\left(t\right)+E\left(t\right)+I\left(t\right)+R(t)\)

The parameter values of the constants are shown as follows in Table 1:

Variables and parameters

\(S(t)\): Susceptible class.

\(E(t)\): Exposed class.

\(I(t)\): Infected class.

\(R(t):\) Recovered class.

\(\Lambda\):The rate of recruitment of susceptible individuals.

\(\beta :\) Transmission rate.

\(\mu\): Natural death rate in all the compartments.

\(\theta\): Rate of latency loss.

γ: Recovery Rate.

Model equations

For \(t\ge 0,\) the fractional order differential equations of the norovirus epidemic model are as follows:

Subject to \(S(0)\ge 0\), \(E(0)\ge 0\), \(I\left(0\right)\ge 0, R\left(0\right)\ge 0 \text{for} t\ge 0.\)

Equilibria of norovirus epidemic model

In this part, we shall discuss two types of equilibria of the model norovirus-free equilibrium (NFE-\({N}^{0}\)) and norovirus existing equilibrium (NEE-\({N}^{*}\)).

and.

Positivity and boundedness

In this segment, we will study the positivity and boundedness of the norovirus-epidemic model.

And hence, \(N\left(t\right)\le M,\) whenever \(t \to \infty .\) Therefore, the feasible region can be defined as:\(\Pi =\{S\left(t\right),E\left(t\right),I\left(t\right),R\left(t\right)\in {R}_{+}^{4}: N(t)\le M\}\).

Theorem 1

For any initial data \(\left(S\left(0\right),\text{E}\left(0\right),\text{I}\left(0\right),R\left(0\right)\right)\in {\mathbb{R}}_{4}^{+} ,\) then the solution \(\left(S\left(t\right),\text{E}\left(t\right),\text{I}\left(t\right),R\left(t\right)\right)\) for the system (1) is positive invariant in \({\mathbb{R}}_{4}^{+}\) where \(\text{t}\ge 0,\) with given positive initial conditions.

Proof

We shall define the norm \({\uplambda }_{\infty }={\text{sup}}_{\text{t}\in {\text{D}}_{\uplambda }}\left|\uplambda (\text{t})\right|\), where \({\text{D}}_{\uplambda }\) is the domain of \(\lambda\), using the above norm, we have:

Let \(=\mu +\beta {I}_{\infty }\), then:

Now, by using \(L^{ - 1} \left\{ {\frac{{s^{\alpha - \beta } }}{{s^{\alpha } - m}}} \right\} = t^{\beta - 1} E_{\alpha ,\beta } \left( {mt^{\alpha } } \right)\)

For the functions \(E (t), I (t)\), and \(R (t)\), the following inequalities hold for respectively, i.e.

\(E\left(t\right)\ge 0, I\left(t\right)\ge 0, R\left(t\right)\ge 0,\forall t\ge 0\) as desired.

Theorem 2

The solutions \(\left(S,E,I,R\right)\in {R}_{+}^{4}\) of the system are bounded and remain within the region \(\Pi\).

Proof

Let us consider a population function as.

By using \({\text{L}}^{ - 1} \left\{ {\frac{{{\text{s}}^{\alpha - \beta } }}{{{\text{s}}^{\alpha } - {\text{M}}}}} \right\} = {\text{t}}^{\beta - 1} {\text{E}}_{\alpha ,\beta } \left( {{\text{Mt}}^{\alpha } } \right)\), we get:

Let \(\text{M}=\text{max}\left\{\text{N}\left(0\right),\frac{\Lambda }{\upmu }\right\}\)

This shows the boundedness of \(\text{N}\left(\text{t}\right).\)

Existence and uniqueness

The following lemma is used to prove the existence and uniqueness of the solution.

Lemma 1

Let \({}_{{t}_{0}}{}^{C}{D}_{t}^{{\varvec{\upzeta}}}\text{ x}\left(\text{t}\right)=\text{ g}\left(\text{t},\text{ x}\right), {\text{t}}_{0}> 0,\) with initial condition \(\text{x}\left({\text{t}}_{0}\right) = {\text{x}}_{{\text{t}}_{0}}\), where, \({\varvec{\upzeta}}\in \left(0, 1\right],\text{ g}:\left[{\text{t}}_{0},\infty \right)\times\Omega \to {\mathbb{R}},\Omega \subseteq {\text{C}}^{1}[{t}_{0},\infty )\), if local Lipschitz condition is satisfied by g(t, x), with respect to x, then, there exists a solution on \([{\text{t}}_{0}, \infty ) \times\Omega\) which is unique.

Theorem 3

At any given time \(t\), the solution of system (1) is guaranteed to exist and be unique.

Proof:

Consider the region \(\Sigma \times [{\text{t}}_{0},\upgamma ]\), with:

\(\Sigma =\left\{\left(S,E,I,R\right)\in {\mathbb{R}}^{4}:S,E,I,R\in {C}^{1}\left[{t}_{0},\infty \right)\wedge \left|S\right|,\left|E\right|,\left|I\right|,\left|R\right|\le Q\right\}\) and \(\upgamma < +\infty .\) Let,

Let,\(K\left(S\right)=\Lambda -\beta SI-\mu S,\)

Then, for \(\left(S,E,I,R\right)\) and \(\left(\overline{S },\overline{E },\overline{I },\overline{R }\right)\in\Sigma\),

Therefore,

Thus, \(K(S)\) satisfies the Lipschitz condition. For contraction mapping, \(\beta Q+\mu <1,\)

Also, let

Then,

Therefore,

Therefore, \(L(E)\) fulfills Lipchitz’s condition.

For contraction, \(\theta +\mu <1.\)

For the third equation of system (1),

Let,

Then,

Therefore,

Therefore, \(N(I)\) satisfies the Lipchitz condition.

For contraction mapping, \(\gamma +\mu <1\).

For the fourth equation of the system,

Let,

Then,

Therefore,

For contraction mapping, \(\mu <1\).

Therefore, \(P(R)\) satisfies the Lipchitz condition.

Let,

Also, let,

Therefore,

Therefore \(K(S), L(E), N(I), and P(R)\) are contraction mappings for \(F<1.\) Therefore, \(K(S), L(E), N(I), and P(R)\) fulfill Lipshitz conditions. Therefore, we conclude that our proposed model equations possess a unique solution, as required.

Reproduction number

The main factor of the model is the threshold number, also termed as reproduction number denoted by \({R}_{0}\) which has a crucial role in the effectiveness of disease. If we change the value of \({R}_{0}\), it can also change the dynamics of disease. If \({R}_{0} <1\), then it expresses the disease control in the population and if \({R}_{0}>1\), then it displays that the disease is proliferating in the population. We suppose the infected and recovered compartments:

The value of \(X{Y}^{-1}\) at \({N}^{0}\) is denoted by \({A}_{{{\varvec{N}}}^{0}}\)

The maximum Eigenvalue of \({A}_{{{\varvec{N}}}^{0}}\) is denoted by \({R}_{0}\) and is given by

Sensitivity analysis

Now, we investigate the sensitivity of the parameters.

Similarly for other parameters, we have the following results.

From the above calculations, it can be concluded that the parameters \(\theta ,\beta , \text{and} \mu\) are more sensitive than \(\gamma\).

Stability analysis of norovirus epidemic model

We shall prove the following well-known conclusions for local stability in both equilibrium points.

Theorem 4

The norovirus free equilibrium (NFE-\({\text{N}}^{0}\)), \({N}^{0}= \left({S}^{0}, {E}^{0}{,I}^{0}, {R}^{0}\right)\) = \(\left(\frac{\Lambda }{\upmu },\text{0,0},0\right)\) is locally asymptotical stable (LAS) if \({R}_{0}<1\), otherwise unstable when \({R}_{0}>1.\)

Proof:

Consider \(\left|J-\lambda I\right|=0\) and hence

If \({\lambda }_{4}<0\), then \(\frac{-\left(\theta +\gamma +2\mu \right)-\sqrt{{(\theta +\gamma +2\mu )}^{2}-4 \left(\theta +\mu \right)\left(\gamma +\mu \right)- \frac{\theta \Lambda \beta }{\mu }}}{2}<0\)

This shows that the system is in a locally asymptotical stable state at \({\text{N}}^{0}\).

Theorem 5

The norovirus existing equilibrium \(\left(NEE-{N}^{*}\right)\), \({N}^{*}=\left({S}^{*}, {E}^{*}, {I}^{*}, {R}^{*}\right)\) is locally asymptotical stable (LAS) if \({R}_{0}>1\).

Proof

Consider \(\left|J-\lambda I\right|=0\) and hence

Now, expanding by \({\text{R}}_{1.}\)

Now, put the values of \({\text{S}}^{*}\text{ and }{\text{I}}^{*},\text{ we get}\)

The roots of the following equation

The coefficients of above polynomial equation of \(\lambda\) are as follows:

\({C}_{1}=1>0,\) similarly,\({C}_{2}>0, {C}_{3}>0\)

and \({C}_{4}=\theta \beta\Lambda -\upmu \left(\theta +\mu \right)\left(\gamma +\mu \right)\)

If \({R}_{0}>1\), then by Routh-Hurwitz Criterion for 3rd degree polynomial, norovirus existing equilibrium \(\left(NEE-{N}^{*}\right)\), \({N}^{*}=\left({S}^{*}, {E}^{*}, {I}^{*}, {R}^{*}\right)\) is locally asymptotical stable (LAS).

Lemma 2

Let \(\text{x}:[0,\infty )\to {\mathbb{R}}^{+}\) be a continuous function and let \({\text{t}}_{0}\ge 0\). Then, for any time \(\text{t}\ge {\text{t}}_{0} , \alpha \in \left(\text{0,1}\right)\text{ and }{\text{x}}^{*}\in {\mathbb{R}}^{+} ,\) the following inequality holds:

Theorem 6

The system at \({N}^{0}=\left({S}_{0},{E}_{0},{I}_{0},{R}_{0}\right)=\left(\frac{\Lambda }{\upmu },\text{0,0},0\right)\) is globally asymptotically stable if \({R}_{0}<1\).

Proof

Let \(L=\left(S+(E+I+R)\right)-{S}_{0}-{S}_{0}log \frac{S}{{S}_{0}}\).

Observe that \({}_{0}{}^{c}{D}_{t}^{{\varvec{\upzeta}}}L<0\) when \({R}_{0}<1.\)

Therefore, norovirus-free equilibrium is globally asymptotically stable.

Theorem 7

The norovirus existing equilibrium (NEE-\({N}^{*}\)), \({N}^{*}=\)(S*, E*, I*, R*) is globally asymptotical stable (GAS) if \({R}_{0}>1\).

Proof

Consider the Lyapunov function \(Z:\Pi \to R,\) defined as.

Hence, by Lasalle’s invariance principle, norovirus existing equilibrium is globally asymptotical stable (GAS).

Numerical method

We now develop an NSFD, numerical scheme for the projected model.

Let \({}_{0}{}^{c}{D}_{t}^{{\varvec{\upzeta}}}y\left(t\right)=\text{f}\left(y(t)\right) ,\text{ y}\left(\mathcal{T}\right)={\text{y}}_{0} (0<{\varvec{\upzeta}}<1)\)

Then,

where,\({C}_{\nu }^{{\varvec{\upzeta}}}=-{\left(1\right)}^{\nu -1}\left(\begin{array}{c}{\varvec{\upzeta}}\\ \nu \end{array}\right) , {r}_{n+1}^{{\varvec{\upzeta}}}={h}^{{\varvec{\upzeta}}} {r}_{0}^{{\varvec{\upzeta}}}\left({\mathcal{T}}_{\text{n}+1}\right)={\gamma }_{0,-1}^{{\varvec{\upzeta}}}{\left(n+1\right)}^{-{\varvec{\upzeta}}}\)

And the coefficients

Lemma 3

Assume that \(0<{\varvec{\upzeta}}<1\), then \({C}_{\nu }^{{\varvec{\upzeta}}}\) are positive and \({C}_{\nu }^{{\varvec{\upzeta}}}=O(\frac{1}{{\nu }^{1+{\varvec{\upzeta}}}})\) as \(\nu \to \infty\). Further, the coefficients \({C}_{\nu }^{{\varvec{\upzeta}}}\) and \({r}_{\nu }^{{\varvec{\upzeta}}}\) satisfy for \(\nu>1\) the properties:

\(0<{C}_{\nu +1}^{{\varvec{\upzeta}}}<{C}_{\nu }^{{\varvec{\upzeta}}}<\dots <{C}_{1}^{{\varvec{\upzeta}}}={\varvec{\upzeta}}<1\) and \(0<{r}_{\nu +1}^{{\varvec{\upzeta}}}<{r}_{\nu }^{{\varvec{\upzeta}}}<\dots <{r}_{1}^{{\varvec{\upzeta}}}=\frac{1}{\Gamma (1-{\varvec{\upzeta}})}\)

Proof

It is clear that for all \({\varvec{\upzeta}}\in \left(\text{0,1}\right],\)

Moreover, for \({\varvec{\upzeta}}\in \left(\text{0,1}\right],\) is \({\varvec{\upzeta}}+\frac{1}{\Gamma (1-{\varvec{\upzeta}})}>1\)

Also, \(\sum_{\nu =1}^{\infty }{C}_{\nu }^{{\varvec{\upzeta}}}=1\)

Grunwald–Letnikov non-standard finite difference method

Divide the interval \([0, L]\) into M ∈ N subintervals and \(h =\frac{L}{M}\). The approximate solutions \(S, E, I, \text{and} R\) of will be denoted as \({S}^{n}, {E}^{n}, {I}^{n}, {and R}^{n}\), respectively, for each \(n=\text{0,1}, \dots , N.\)

The first equation of the system (1) is

Use Grunwald–Letnikov approximation

Second equation of the system (1)

Use Grunwald–Letnikov approximation

Third equation of the system (1)

Use Grunwald–Letnikov approximation

Fourth equation of the system (1)

Use Grunwald–Letnikov approximation for the above equation.

We get

Some straightforward calculations and simplifications will lead to the following expression.

Similarly,

Properties

Theorem 8

The SEIR model system (1) in its deterministic form ensures that the solution remains non-negative.

Proof

Let.

For \(n=0,\) we have:

Now, suppose that:

Based on the aforementioned findings, for any positive integer \(n\) that is, \(\text{n}\in {\mathbb{Z}}^{+}\), we deduce that,

Therefore, in the discrete model, all the state variables ensure that the solution remains non-negative, as needed.

Theorem 9

(Boundedness)

Let \(\Lambda>0, \mu>0, \theta>0, \beta>0, \gamma>0, {\left(\psi (h)\right)}^{{\varvec{\upzeta}}}>0\) For all \({\varvec{\upzeta}}\in (\text{0,1})\), then there is a constant

Such that

Proof

Consider the discretized equation for the susceptible class as given by,

By adding equations from (2) to (5) and simplifying, we have

For, \(n=0\), we reach the following expression,

Now for \(n=1\) and \({\varvec{\upzeta}}\in (\text{0,1})\), we get,

where,

Similarly, for \(n=2,\) we arrive at

Now, we suppose that for \(n\in \left\{\text{3,4},\dots ,{N}_{0}-1\right\}\) and for \({\varvec{\upzeta}}\in \left(\text{0,1}\right)\)

Thus, for \(n={N}_{0}\), we obtain

Finally, we conclude that.

as desired.

Using the MATLAB software the diagrams are created for norovirus-free equilibrium (NFE) and norovirus-existing equilibrium (NEE) by using the values of the parameters as presented in Table 1:

Results and discussion

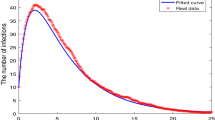

In this section, we present the simulated graphs of Norovirus for various classes of population. To start with, Fig. 1 represents the nonlinear evolution of the susceptible compartment. The figure reflects that the number of susceptible individuals increases when the virus is extinct from society. The different trajectories depict the rates of convergence against highlighted values of \(\upzeta\) as shown in the figure. The graphical templates are similar with different peak values, but they show the rates of convergence. For the greater value of \(\upzeta\), the convergence speed is higher as compared to the smaller values of \(\upzeta\). Consequently, the fractional value of \(\upzeta\) decides the speed of convergence. It is in line with the real disease phenomena. For instance, COVID-19 spread in the world at different rates. Similarly, the Fig. 2 illustrates the nonlinear behavior of the exposed class. The number of exposed individuals decreases with time as the disease dies out. Because, when the disease-free equilibrium, the exposed population approaches zero. Biologically, when the disease diminishes, the number of exposed individuals also decreases gradually and ultimately becomes zero within due course of time. The rate of convergence towards the NFE depends upon the fractional order parameters \(\upzeta\). Likewise, Fig. 3 portrays the scenario about the infected populace, which also hits the virus-free point (i.e. zero). Four graphs in the figure touch the accurate point with different speeds according to the value of \(\upzeta\). The curved graph that reaches the target point earlier than the other possesses a higher speed and greater value of \(\upzeta\). Lastly, the graphs in Fig. 4 capture the nonlinear behavior of the recovered class. It is evident from the graphs that they advanced towards the right point with different rates of convergence. Remarkably, all the graphs in Figs. 1, 2, 3, 4 reach the target with different paces. Correspondingly, Figs. 5, 6, 7, 8 outline the dynamical behavior of the susceptible, exposed, infected, and recovered classes at the NEE. Every graph converges towards the analytically calculated endemic equilibrium point with different rates depending upon the fractional value of \(\upzeta\). The graph depicts that the number of susceptible individuals decreases while the individuals’ other compartments increase when the disease persists in the community. This behavior of the graphs is by the disease phenomena. When the disease outbreaks the infected and exposed individuals start increasing and the susceptible individuals start decreasing. After some time, the infected individuals become recovered after treatment. Therefore, the size of the recovered class increases with time. Notably, fractional order \(\upzeta\) describes the rate of convergence. In practical settings, model parameters such as transmission rate, recovery rate, and latency period could be calibrated using outbreak data from schools, hospitals, or cruise ships. This calibration, through data-fitting techniques like least squares or Bayesian inference, would enhance the model’s predictive accuracy and make it more applicable for public health planning.(Fig. 9).

Conclusion

This study presents a Fractional Order Norovirus Epidemic Model that provides valuable biological insights into the transmission dynamics of Norovirus. Through analytical derivations and numerical simulations, our results illuminate the influence of various biological factors on Norovirus outbreaks, especially in environments with high contact rates. We derived the equilibrium points and the basic reproduction number \({{\varvec{R}}}_{0}\), of the model. This reproduction number plays a crucial role in understanding the conditions necessary for outbreak prevention or persistence. When \({{\varvec{R}}}_{0}>1\), the model indicates sustained transmission, aligning with observed patterns in Norovirus outbreaks, where limited immunity and environmental persistence drive recurrent infections. This highlights the high contagiousness of Norovirus and the challenges in controlling its spread in closed settings, even after initial infection peaks. The model’s ability to account for temporary immunity also emphasizes the necessity for frequent hygiene measures and disinfection to break the transmission cycle. Moreover, our stability analysis verifies that if \({{\varvec{R}}}_{0}<1\) , the infection eventually dies out, providing vital biological insight into containment strategies. The Lyapunov function and LaSalle’s invariance principle verify that, for certain conditions, global stability can be achieved, keeping outbreaks biologically under control. Numerical results generated by the NSFD scheme confirm these analytical findings. This simulation shows both biologically relevant insights, the persistence of the virus in the environment with time, and high infectivity. Fractional-order modelling will appropriately capture the memory effect of infected surfaces and objects causing further infections even after the primary cases have recovered-a reason to emphasize cleaning protocols in outbreak scenarios. Our results suggest that fractional-order models have an edge over the classical integer-order models in providing a more refined and realistic representation of Norovirus transmission dynamics. Future work might enhance the predictive capacity of the model by integrating it with real-time outbreak data from facilities such as schools, hospitals, and cruise ships, and extension of the work into several areas could also be explored. This would increase the relevance of the model to real-life situations as well as help to identify effective containment measures. As a future direction, this work can be extended by exploring the integration of quantum computing techniques to enhance the efficiency of epidemic simulations. Quantum algorithms, particularly those based on quantum differential equation solvers, could potentially accelerate the numerical solution of complex fractional-order systems. This approach may open new pathways for real-time analysis and high-dimensional optimization in infectious disease modeling, especially when dealing with large-scale data or uncertain environments.

Data availability

The data that support the findings of this study are available within the article.

References

Gaythorpe, K. A. M., Trotter, C. L., Lopman, B., Steele, M. & Conlan, A. J. K. Norovirus transmission dynamics: A modeling review. Epidemiol. Infect. 146(02), 147–158 (2018).

Yang, W., Steele, M., Lopman, B., Leon, J. S. & Hall, A. J. The population-level impacts of excluding norovirus-infected food workers from the workplace: A mathematical modeling study. Am. J. Epidemiol. 188(1), 177–187 (2019).

Towers, S. et al. Quantifying the relative effects of environmental and direct transmission of norovirus. Royal Soc. Open Sci. 05(03), 01–13 (2018).

Chen, T. et al. Evidence-Based interventions of norovirus outbreaks in China. BMC Public Health 16(01), 01–09 (2016).

Gaythorpe, K. A. M., Trotter, C. L. & Conlan, A. J. K. Modeling norovirus transmission and vaccination. Vaccine 36(37), 5565–5571 (2018).

Lopman, B. A., Steele, D., Kirkwood, C. D. & Parashar, U. D. The vast and varied global burden of norovirus: Prospects for prevention and control. PLoS Med. 13(04), 01–12 (2016).

Wang, J. & Deng, Z. Modeling and prediction of oyster norovirus outbreaks along Gulf of Mexico coast. Environ. Health Perspect. 124(05), 627–633 (2016).

Assab, R. & Temime, L. The role of hand hygiene in controlling norovirus spread in nursing homes. BMC Infect. Dis. 16(1), 01–10 (2016).

Canales, R. A. et al. Modeling the role of fomites in a norovirus outbreak. J. Occup. Environ. Hyg. 16(1), 16–26 (2019).

Shieh, Y. C., Tortorello, M. L., Fleischman, G. J., Li, D. & Schaffner, D. W. Tracking and modeling norovirus transmission during mechanical slicing of globe tomatoes. Int. J. Food Microbiol. 180(01), 13–18 (2014).

Wang, Y., Abdeljawad, T. & Din, A. Modeling the dynamics of stochastic norovirus epidemic model with time delay. Fractals 30(05), 01–13 (2022).

Bartsch, S. M., Huang, S. S., Wong, K. F., Avery, T. R. & Lee, B. Y. The spread and control of norovirus outbreaks among hospitals in a region: A simulation model. InOpen Forum Infect. Dis. 01(02), 01–07 (2014).

Raezah, A. A., Zarin, R. & Raizah, Z. Numerical approach for solving a fractional-order norovirus epidemic model with vaccination and asymptomatic carriers. Symmetry 1(1), 01–27 (2023).

Chenar, S. S. & Deng, Z. Environmental indicators for human norovirus outbreaks. Int. J. Environ. Health Res. 27(01), 40–51 (2017).

Kim, S., Vaidya, B., Cho, S., Kwon, J. & Kim, D. Human norovirus–induced gene expression biomarkers in zebrafish. J. Food Prot. 85(06), 924–929 (2022).

Calduch, E. N., Cattaert, T. & Verstraeten, T. Model estimates of hospitalization discharge rates for norovirus gastroenteritis in Europe, 2004–2015. BMC Infect. Dis. 21(01), 01–10 (2021).

Matsuyama, R., Miura, F. & Nishiura, H. The transmissibility of noroviruses: Statistical modeling of outbreak events with known route of transmission in Japan. PLoS ONE 12(3), 01–16 (2017).

O’Reilly, K. M. et al. Predicted norovirus resurgence in 2021–2022 due to the relaxation of nonpharmaceutical interventions associated with COVID-19 restrictions in England: A mathematical modeling study. BMC Med. 19(01), 01–10 (2021).

Lopman, B., Simmons, K., Gambhir, M., Vinjé, J. & Parashar, U. Epidemiologic implications of asymptomatic reinfection: A mathematical modeling study of norovirus. Am. J. Epidemiol. 179(4), 507–512 (2014).

Simmons, K., Gambhir, M., Leon, J. & Lopman, B. Duration of immunity to norovirus gastroenteritis. Emerg. Infect. Dis. 19(8), 1260 (2013).

Shah, K., Khan, A., Abdalla, B., Abdeljawad, T. & Khan, K. A. A mathematical model for Nipah virus disease by using piecewise fractional order Caputo derivative. Fractals 32(02), 2440013 (2024).

Gunasekaran, N., Vadivel, R., Zhai, G. & Vinoth, S. Finite-time stability analysis and control of stochastic SIR epidemic model: A study of COVID-19. Biomed. Signal Process. Control 86(01), 105123 (2023).

Jan, R. & Boulaaras, S. Analysis of fractional-order dynamics of dengue infection with non-linear incidence functions. Trans. Inst. Meas. Control. 44(13), 2630–2641 (2022).

Jan, A., Jan, R., Khan, H., Zobaer, M. S., & Shah, R. (2020). Fractional-order dynamics of Rift Valley fever in ruminant host with vaccination. Commun. Math. Biol. Neurosci., Article-ID. (2020).

Jan, R. & Xiao, Y. Effect of pulse vaccination on dynamics of dengue with periodic transmission functions. Adv. Difference Equ. 2019(1), 1–17 (2019).

Tang, T. Q. et al. Modeling and analysis of breast cancer with adverse reactions of chemotherapy treatment through fractional derivative. Comput. Math. Methods Med. 2022(1), 5636844 (2022).

Tang, T. Q. et al. Modeling the dynamics of chronic myelogenous leukemia through fractional-calculus. Fractals 30(10), 2240262 (2022).

Deebani, W., Jan, R., Shah, Z., Vrinceanu, N. & Racheriu, M. Modeling the transmission phenomena of water-borne disease with non-singular and non-local kernel. Comput. Methods Biomech. Biomed. Engin. 26(11), 1294–1307 (2023).

Benkerrouche, A., Souid, M. S., Chandok, S. & Hakem, A. Existence and Stability of a Caputo Variable-Order Boundary Value Problem. J. Math. 2021(1), 7967880 (2021).

Bouazza, Z., Souid, M. S. & Günerhan, H. Multiterm boundary value problem of Caputo fractional differential equations of variable order. Adv. Difference Equ. 2021(1), 400 (2021).

Benkerrouche, A., Souid, M. S., Stamov, G. & Stamova, I. Multiterm impulsive Caputo-Hadamard type differential equations of fractional variable order. Axioms 11(11), 634 (2022).

Raza, A., Minhós, F., Shafique, U. & Mohsin, M. Mathematical Modeling of Leukemia within Stochastic Fractional Delay Differential Equations. CMES-Comput. Model. Eng. Sci. 143(3), 3411–3431 (2025).

Raza, A., Minhós, F., Shafique, U., Fadhal, E. & Alfwzan, W. F. Design of Non-Standard Finite Difference and Dynamical Consistent Approximation of Campylobacteriosis Epidemic Model with Memory Effects. Fract. Fract. 9(6), 358 (2025).

Minhós, F., Raza, A., & Shafique, U. An efficient computational analysis for stochastic fractional heroin model with artificial decay term. Aims Mathematics, 10(3). (2025).

Cui, T., Liu, P. & Din, A. Fractal–fractional and stochastic analysis of norovirus transmission epidemic model with vaccination effects. Sci. Rep. 11(1), 24360 (2021).

Acknowledgements

This work was supported by the Ministry of Education, Youth and Sports of the Czech Republic through the e-INFRA CZ (ID:90254), with the financial support of the European Union under the REFRESH – Research Excellence For Region Sustainability and High-tech Industries project number CZ.10.03.01/00/22\_003/0000048 via the Operational Programme Just Transition, and by Grant of SGS No. SP2025/049, VŠB—Technical University of Ostrava, Czech Republic.

Funding

This work was supported by the Ministry of Education, Youth and Sports of the Czech Republic through the e-INFRA CZ (ID:90254), with the financial support of the European Union under the REFRESH – Research Excellence For Region Sustainability and High-tech Industries project number CZ.10.03.01/00/22\_003/0000048 via the Operational Programme Just Transition, and by Grant of SGS No. SP2025/049, VŠB—Technical University of Ostrava, Czech Republic.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

Suhail Saleem contributed to Conceptualization, Methodology, Investigation, Data curation, and Formal analysis. Ali Raza contributed to Conceptualization, Methodology, Formal analysis, Data curation, Investigation, Project administration, Validation, Visualization, and Writing – original draft. Marek Lampart contributed to Conceptualization, Investigation, Data curation, Project administration, Supervision, Funding acquisition, Resources, Validation, Visualization, and Writing – review & editing. Muhammad Rafiq and Nauman Ahmed contributed to Data curation, Resources, Investigation, Supervision, Software, Validation, Visualization, and Formal analysis. Muhammad Shoaib Arif contributed to Validation, Supervision, Visualization, and Software.

Corresponding authors

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher’s note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if you modified the licensed material. You do not have permission under this licence to share adapted material derived from this article or parts of it. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Saleem, S., Raza, A., Lampart, M. et al. Numerical solutions for norovirus epidemic spread: implications for public health control. Sci Rep 15, 29657 (2025). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-14688-4

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-14688-4

Keywords

This article is cited by

-

Numerical results of fractional order difference system for norovirus disease with feedback neural networking

Boundary Value Problems (2025)