Abstract

Music-evoked nostalgia has the potential to assist in recalling autobiographical memories and enhancing well-being. However, nostalgic music preferences vary from person to person, presenting challenges for applying nostalgia-based music interventions in clinical settings, such as a non-pharmacological approach. To address these individual differences, we developed the Nostalgia Brain-Music Interface (N-BMI), a neurofeedback system that recommends nostalgic songs tailored to each individual. This system is based on prediction models of nostalgic feelings, developed by integrating subjective nostalgia ratings, acoustic features and in-ear electroencephalographic (EEG) data during song listening. To test the effects of N-BMI on nostalgic feelings, state-level well-being, and memory recall, seventeen older and sixteen younger participants took part in the study. The N-BMI was personalized for each individual, and songs were recommended under two conditions: the “nostalgic condition“, where songs were selected to enhance nostalgic feelings, and the “non-nostalgic condition“, to reduce nostalgic feelings. We found nostalgic feelings, state-level well-being, and subjective memory vividness were significantly higher after listening to the recommended songs in the nostalgic condition compared to the non-nostalgic condition in both groups. This indicates that the N-BMI enhanced nostalgic feelings, state-level well-being, and memory recall across both groups. The N-BMI paves the way for innovative therapeutic interventions, including non-pharmacological approaches.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

The global population continues to grow and age rapidly. The proportion of the global population 60 + years old is predicted to reach about 22% in 2050 and about 32% in 21001. Therefore, from a public health perspective, supporting “healthy aging” is an important issue in modern society2. Healthy aging is defined as the process of developing and maintaining the functional ability that enables well-being in older adults3.

Nostalgia is considered a psychological resource that can support healthy aging4,5. Nostalgia is a bittersweet emotional experience associated with recollections of the past, and this emotion is frequently experienced in everyday life and across age and cultural boundaries6,7. Nostalgia has negative aspects but is mainly perceived as a positive emotion8. Nostalgic experience also has been associated with a reduction in loneliness and an increase in self-esteem, self-continuity, and optimism9,10,11,12. Also, nostalgic reminiscence is known to enhance psychological resources by acting as a buffer against anxiety arising from existential threats13,14. Thus, nostalgia is also known to contribute to improving psychological well-being in older adults5,15. In addition, nostalgia is a self-related emotion strongly linked to the recall of memories experienced by the self16,17,18. Memory loss, one of the cognitive impairments, is frequently reported with aging19. Nostalgic experience is associated with improved recall and recognition of self-relevant memories in older adults20. Therefore, nostalgia may also contribute to the maintenance of cognitive function in healthy aging4.

Nostalgia can be triggered by various senses such as sight21,smell22 and taste23 but nostalgia induced by music may enhance the effects of these nostalgic functions more effectively. Music is known to have effects such as lowering cortisol levels and reducing stress, as well as decreasing negative emotions and evoking positive ones24,25,26. Therefore, nostalgia through music may be more effective in promoting the well-being of older adults. Indeed, music-evoked nostalgia also has psychological benefits, serving a similar buffering function27. Additionally, research shows that music can help preserve long-term memory28 and because it is deeply integrated into daily life, musical memories are often associated with personal experiences and events. Thus, music can serve as a trigger for autobiographical memories29. Music that is closely tied to an individual’s past is known to promote spontaneous recall of memories in older adults30. It is possible that nostalgic music may be effective in supporting the recall of memories in older adults.

Nostalgic music may be useful not only for healthy aging but also as an intervention for dementia prevention. While the growing prevalence of dementia, pharmacological treatments remain challenging, due to the complex nature of the disease and associated side effects of the treatment31. Behavioral and psychological symptoms of dementia (BPSD), such as depression and anxiety, are significant concerns in dementia care32. Among the various music-based approaches for addressing cognitive symptoms, listening to music has been shown to alleviate these symptoms and enhance psychological health and overall well-being33,34,35. The evocation of nostalgia functions as a psychological resource for individuals with dementia and has also been confirmed to provide mnemonic benefits20,36,37. This effect of nostalgic music is especially significant in clinical settings, where it can serve as a valuable intervention tool for individuals with dementia who often face existential threats due to their condition20,37. Memory loss is a primary symptom of dementia, as well as mild cognitive impairment (MCI), a condition often seen as a precursor to dementia38,39. The phenomenon of maintaining long-term memory and autobiographical recall has been observed even in individuals with severe memory impairment, suggesting that music may play a significant role in slowing the progression of memory disorders in people with dementia40,41,42,43,44,45,46,47. Thus, nostalgic music could be effective in helping people with their recollections.

However, the impact of nostalgic music varies from person to person, as music-induced nostalgia depends on personal characteristics, contextual factors like emotional experience with the music, memory states, and the interaction of these factors48,49. For instance, previous research suggest that music-evoked nostalgia is associated with arousal and the intensity of affective valence; however, the strength of relationship between nostalgia and valence intensity is modulated by mood state, one of the individual traits48. Personalized music listening has also been recommended in conventional approaches for people with dementia50,51. By not only playing an individual’s nostalgic songs but also quantitatively assessing the emotional state associated with each song during selection, it may be possible to maximize the feeling of nostalgia and make it more effective as a form of care for individuals with older adults.

To address individual differences, we developed a Nostalgia Brain-Music Interface (N-BMI), designed to enhance feelings of nostalgia by recommending songs tailored to each individual based on prediction models of nostalgic feelings. We tested this interface on healthy younger and older adults. These models were built using rating data on subjective nostalgia, acoustic features of self-selected and other-selected nostalgic songs, and in-ear electroencephalographic (EEG) activity recorded while listening to the songs. The development of the N-BMI was inspired by previous research on EEG-based Brain-Computer Interfaces (BCIs). For instance, BCIs have been shown to modify music according to an individual’s estimated arousal and valence52 or to mediate emotions by generating personalized music53 highlighting the potential for recommending personalized music through EEG activity analysis. By decoding user preferences directly from EEG signals, real-time updates of personalized song recommendation can be made in an annotation-free manner. Thus, the Nostalgia Brain-Music Interface minimizes the need for explicit, cognitively demanding user feedback. Additionally, a prior study demonstrated that neural activation related to nostalgia can be predicted by personality traits54 suggesting the feasibility of developing a neurofeedback system based on nostalgia-related brain activity. However, no research to date has developed a neurofeedback system specifically targeting nostalgia or examined its effects on nostalgia, well-being, and memory retrieval. Therefore, our goal was to develop the N-BMI and evaluate whether the songs recommended by the N-BMI could enhance nostalgic feelings, well-being, and memory recall in both younger and older individuals.

Methods

Nostalgia Brain-Music Interface (N-BMI)

Overview

The proposed Nostalgia Brain-Music Interface (N-BMI) consisted of three steps, referred to as ‘Rec-Dec-Back’: (1) recording, (2) decoding, and (3) feedback (Fig. 1). Before the experiment, participants selected three nostalgic songs. During the recording step, they listened to both self-selected and other-selected songs and rated their subjective feelings of nostalgia, state-level well-being, and subjective memory vividness. EEG activity was recorded using an in-ear EEG device (VIE Inc., Kanagawa, Japan) while participants listened to both self-selected and other-selected songs.

In the decoding step, two models were created using MATLAB 2023b software https://www.mathworks.com): Model 1, the ‘Nostalgia Prediction Model,’ utilized nostalgia ratings and the acoustic features of self-selected and other-selected songs, to predict subjective nostalgic rating. The acoustic features were extracted using the VGGish model, a pretrained convolutional neural network developed by Google55,56. It has been shown that the CNN model’s embedding is more sensitive to emotional responses than low-level acoustic features, and we thought it would be appropriate for use in N-BMI57. Model 2, the ‘Nostalgia Decoder,’ employed Fourier-transformed multidimensional EEG power-frequency data recorded while participants listened to the self-selected and other-selected songs. This model decoded nostalgic feelings from the EEG data by estimating whether the EEG pattern was more similar to those recorded during self-selected song listening or other-selected song listening.

In the feedback step, Model 1 predicted the participant’s nostalgic feeling and recommended a song from a pool of 7,481 songs to either enhance or reduce their nostalgia. While the participant listened to the recommended song, Model 2 decoded their nostalgic feeling every 20 s. The decoded nostalgia and the acoustic features of the recommended song were then added as new supervised inputs to update Model 1. The updated Model 1 predicted the nostalgic feeling again and recommended another song from the pool. During the feedback step, each song was played for 20 s, the model was updated every 20 s, and a total of six songs were played over 120 s (two minutes). After listening to the recommended songs, participants rated their nostalgic feelings, state-level well-being, and subjective memory vividness (see Recording in the Nostalgia Brain-Machine-Interface (N-BMI) section).

‘Rec-Dec-Back’ in the Nostalgia Brain-Music Interface (N-BMI). The N-BMI followed a three-step process called ‘Rec-Dec-Back,’ which refers to (1) recording, (2) decoding, and (3) feedback. During the recording step, participants listened to both self-selected and other-selected nostalgic songs and rated their subjective feelings of nostalgia, state-level well-being, and subjective memory vividness, while EEG activity was simultaneously recorded using an in-ear EEG device. In the decoding step, two models were developed: Model 1, the ‘Nostalgia Prediction Model,’ which utilized nostalgia ratings and the acoustic features of self-selected and other-selected songs extracted through the VGGish model; and Model 2, the ‘Nostalgia Decoder,’ which analyzed Fourier-transformed EEG power-frequency data recorded during song listening. Model 2 decoded nostalgic feelings by estimating whether the EEG patterns more closely matched those recorded during self-selected or other-selected song listening. In the feedback step, Model 1 predicted the participant’s nostalgic feelings and recommended a song from a pool of 7,481 songs to either enhance or reduce nostalgia. While the participant listened to the recommended song, Model 2 decoded nostalgic feelings, and both the decoded nostalgia and the song’s acoustic features were used to update Model 1. The updated Model 1 then predicted nostalgic feelings again and recommended another song from the pool. After listening to the recommended songs, participants rated their nostalgic feelings, state-level well-being, and subjective memory vividness.

EEG data acquisition and processing

We used an in-ear EEG device developed by VIE Inc. (Kanagawa, Japan, https://www.vie.style/), which records EEG data from the left and right ear canals using ear-tip-shaped electrodes, with reference electrodes placed at the back of the neck. The system records data from the left and right ear channels, as well as the difference signal between the two channels, to exclude noise from the common reference electrode signals. The ear-tip design allows for simultaneous recording of EEG signals and music playback. A previous study confirmed the similarity between in-ear EEG signals and temporal EEG signals measured by a conventional EEG device (Brain Amp DC, BrainVision, Canada)58.

The in-ear EEG data were recorded at a sampling frequency of 600 Hz and filtered using a fourth-order Butterworth filter with a frequency range of 3 to 40 Hz. The recorded data from the left and right channels, along with the difference-signal data, were segmented into 4-second time windows with 50% overlap. A Fourier transform was applied to each segment for each time-series data (i.e., left, right, and difference signal). EEG power across the 4–40 Hz bands was calculated in 0.5 Hz steps.

To detect noise, we performed two steps. First, to remove common noise between the two channels and over time, such as noise from eye movements, we applied independent component analysis (ICA) to the EEG data from the left and right channels. One of the components, which had the larger root mean square (RMS) value of the two components, was labeled as noise and removed from the filtered data. Second, to remove independent noise from each channel or time segment, we calculated a noise flag for each segment. This flag was estimated by taking the average value of the sum of the power spectral density, RMS, maximum gradient, and kurtosis, each of which was transformed to a z-score. The resulting mean value was considered an absolute amplitude value. If this amplitude value was larger than 2.5, the noise flag was set to 1; if smaller, the noise flag was set to 0. This calculation was applied separately to the right and left channel data. We used only the epochs without noise flags. Noise quantification and rejection were performed for each segment based on criteria from a previous study59.

For the extraction of the EEG components, the power-transformed data from the left and right ear channels, along with the difference signal, were combined horizontally and compressed to a maximum of 150 dimensions using principal component analysis (PCA). If the number of these dimensions was less than 150, we used all the components. These dimensional data were then used to create Model 2, the ‘Nostalgia Decoder,’ which decoded the participants’ nostalgic state.

Recording in the Nostalgia Brain-Machine Interface (N-BMI)

Younger participants were instructed to bring three songs that made them feel nostalgic prior to the experiment. Older participants were asked to choose from a list of songs already on hand, that were popular when they were 15 years old, a period commonly associated with heightened autobiographical salience29. This approach was adopted because older participants were expected to have cognitive burden when recalling nostalgic songs, and because it was necessary to obtain all songs on the day of the experiment, while options for accessing older music were limited.

Participants wore in-ear EEG devices. During the recording step of the N-BMI, they listened to three self-selected nostalgic songs and three other-selected songs (six songs in total). To make extreme conditions of nostalgic and non-nostalgic states, other-selected songs in both younger and older participants are chosen within a participant in the younger group randomly. Each song was played for 45 s from the beginning, with the order of the songs randomized. EEG data were recorded while participants listened to the six songs. After each song, participants rated their nostalgic feelings, state-level well-being, and subjective memory vividness using a Visual Analog Scale (VAS) ranging from 0 to 100 (0 = Not at all, 100 = Strongly). The VAS was displayed on a personal computer (PC), and participants were asked to enter their ratings. For older participants who had difficulty using the PC, a printed version of the VAS was provided, and they indicated their rating by pointing to the desired value on the paper, which the experimenter then inputted into the PC.

For the rating of nostalgic feelings, we used one item: (i) ‘I felt nostalgic,’ which participants answered on the VAS. In the study, we presented “Natsukashii” in Japanese to participants scale based on the previous study60. Regarding as well-being, in this study, we define state-level well-being as positive emotional states related to mental health characterized by feelings such as cheerfulness, interest, and enjoyment of life, consistent with previous research61. Accordingly, we selected items from an abbreviated version of the 38-item Mental Health Inventory, the MHI-1861, which assesses mental health with a focus on emotional state-level well-being. For our study, we extracted eight items that contribute to the emotional state-level well-being score: (i) ‘I was interested,’ (ii) ‘I felt loved and needed by others,’ (iii) ‘I had proper non-nostalgic over my actions, thoughts, and feelings,’ (iv) ‘I felt calm and peaceful,’ (v) ‘I was emotionally calm,’ (vi) ‘I was relaxed without problems,’ (vii) ‘I was cheerful and lighthearted,’ and (viii) ‘I was a happy person’. MHI-18 measures mental health, containing the two concepts of psychological distress (e.g., symptoms of anxiety and depression) and psychological state-level well-being (e.g., feeling cheerful, interest in and enjoyment of life), which is widely used for mental health assessments. We have extracted items related to the total score in the scale. As subjective memory vividness, participants rated how strongly they felt they had retrieved a memory. For the rating of subjective memory vividness, we used three items: (i) ‘The overall memory of the event is extremely clear,’ (ii) ‘The memory of the event is extremely detailed,’ and (iii) ‘Overall, I remember the event clearly.’ These items were retrieved from the Japanese version of the Memory Characteristics Questionnaire (MCQ)62 which were related to the Clarity factor in the scale. Participants responded to these questions based on memories that came to mind while listening to the recently played song. If the participants could not remember anything, they were instructed to answer 0.

All older participants used a printed version of the VAS, and a shorter version of the state-level well-being and subjective memory vividness scales was administered based on the results of a small pilot study for older participants. In the pilot study, older adults took about 1 h to complete all procedure of the experiment with shorten questionnaires and showed signs of fatigue. Since the experiment needs to be conducted within a limited time frame at a facility, we reduced the number of items to minimize burden and ensure completion. Specifically, they answered three items for state-level well-being: (i) ‘I was interested,’ (iv) ‘I felt calm and peaceful,’ and (vii) ‘I was cheerful and lighthearted,’ and one item for subjective memory vividness: (iii) ‘Overall, I remember the event clearly.’ This modification was implemented to accommodate older participants, as they had difficulty using a computer.

Decoding in the Nostalgia Brain-Machine Interface (N-BMI)

Model 1: Nostalgia Prediction Model

Model 1 (the Nostalgia Prediction Model) consisted of a Least Absolute Shrinkage and Selection Operator (LASSO) regression model that predicted nostalgic feelings based on acoustic features. Model 1 was developed using nostalgia ratings and acoustic feature data collected during the recording phase, which values were standardized to z-scored. Acoustic features were calculated using the VGGish model, which transforms audio inputs into spectrograms and extracts 128 dimensions of acoustic features. Each of the six songs played had a duration of 45 s, and VGGish transformed this song data into a matrix with 128 acoustic feature dimensions as columns and 184 time frames as rows—the number of time frames being determined independently by VGGish based on the song’s duration. An average value was then calculated for every 10-second segment for each dimension. These features were subsequently z-scored using the mean and standard deviation of the acoustic features from the songs in our music database (7,481 songs used in the feedback phase of the N-BMI, see below). If the standard deviation of a normalized feature exceeded an absolute value of 2, it was capped at 2 or -2. To reduce dimensionality, only the normalized features with a standard deviation greater than 0.01 were retained, as features below this threshold were considered to provide minimal informational value. Each segment was paired with nostalgia ratings for the corresponding piece of music, and this data was used as training data for Model 1.

Thus, this nostalgia prediction model can be described as:

where \(\hat{y}_{i}\) is the predicted nostalgic feeling for song i. \(\hat{\beta }_{0}\) is the intercept, and \(\hat{\beta }\) is a vector of coefficients for each acoustic feature. xi is a vector of acoustic features calculated by VGGish for song i , with values that have already been capped based on their standard deviation. \(\hat{\beta }_{0}\) and \(\hat{\beta }\) are the variables of β0 and β , which minimize the loss function expressed below:

where λ is the optimal parameter to regulate overfitting, which is determined by cross validation (see Evaluation of Model Accuracy section). N represents the number of the training data, which is 6.

Model 2: Nostalgia Decoder

Model 2 (Nostalgia Decoder) consisted of a logistic LASSO regression model, which classified and calculated the likelihood that the current EEG pattern was closer to the pattern observed while listening to self-selected nostalgic songs or other-selected nostalgic songs. The model was created using the Fourier-transformed 150-dimensional EEG power-frequency data recorded during the listening sessions for both self-selected and other-selected songs (see EEG Data Acquisition and Processing section).

Consequently, this model can be described as:

Where \(\hat{Y}\) represents the odds ratio of nostalgic feeling. j is the number of EEG frequency dimensions (with a maximum value of 150), \(\hat{\gamma }_{0}\) is the intercept, and \(\hat{\gamma }_{j}\) is a vector of coefficients corresponding to each EEG frequency. The optimal was selected by 20-fold cross-validation. These values were determined to minimize the loss function of below:

where λ is the optimal parameter to regulate overfitting, which is determined by cross validation (see Evaluation of Model Accuracy section). M represents the number of the training data, which is the number of the EEG frequency. The process was the same as used in Model 1. Xj is a vector of dimensions representing EEG frequency. The model uses the EEG data in the most recent 4 s for decoding, which is performed every 1 s. After that, the decoded values for the last 5 s were averaged to smooth out sudden changes in decoding results. This moving mean value was used in the following analysis as the final decoded value. If all EEG data within the 5-second window were marked as noise, the final decoded value was treated as missing. The methodology for creating the decoder model was the same as that used in the previous study59.

Feedback using the Nostalgia Brain-Machine Interface (N-BMI)

Music database used for feedback.

We used a music database of 7,481 songs to generate music feedback in our N-BMI. The database consisted of songs that appeared in GfK Japan’s weekly music chart Top 1,000 between April 2018 and February 2023 (the earliest year the song had released was 1942, and the median was 2018; see Supplementary Table S1 and Supplementary Figure S1), as well as 600 songs popular from the 1920s to the 1980s, sourced from the “Seishun Uta Nenkan (Youth Song Yearbook)” CD collection.

Music recommendation using Model 1 and Model 2

First, Model 1 was applied to each song in the music database, and the predicted nostalgic feeling was calculated for each song. Next, we calculated the acoustic similarity (z-scored correlation coefficient) of each song in the music database relative to the averaged acoustic features of the three self-selected songs. We then summed the predicted nostalgic feeling and the acoustic similarity value to create a measure for music recommendation, which was used to rank the songs in the database. The higher the music recommendation value, the more similar the song was to the self-selected nostalgic songs and the more likely it was to induce a nostalgic feeling.

Using the music recommendation value, we recommended music under two conditions to test the effects of our N-BMI system: the “nostalgic condition,” where a song was recommended to enhance nostalgic feelings, and the “non-nostalgic condition,” where a song was recommended to reduce nostalgic feelings (see Fig. 2A and B, respectively). In the nostalgic condition, the system randomly selected a song from the top 10 songs ranked by the music recommendation value, while in the non-nostalgic condition, the system randomly selected a song from the bottom 10 songs ranked by the music recommendation value.

After the first recommended song was played for 20 s, Model 2 decoded the nostalgic feeling from in-ear EEG data (Fig. 2). Using the decoded nostalgic-feeling value (Ŷ value in (3a)) and the maximum and minimum VAS values of each participant, we calculated the value \(\hat{y}^{\prime}\) as:

The \(\hat{y}^{\prime}\) is the decoded nostalgic feeling, which approximates VAS value using the maximum and minimum VAS ratings of nostalgia in a participant. This approximate value \(\hat{y}^{\prime}\) was used for updating after standardization to z-score. \(\bar{\hat{Y}}\) is the average of the decoded nostalgic feeling over the 20 seconds of data recording. The average of \(\hat{y}^{\prime}\) value and the VGGish values of the recommended song over the 20 seconds were used to update Model 1. Thus, Model 1 was updated every 20 seconds during the music feedback. Using the updated Model 1, our system recalculated the music recommendation value and re-ranked the songs in the database. During the music feedback step, (1) was updated five times in total and recommended six songs over 120 seconds (two minutes) (Figure 2).

Schematic drawing of decoded nostalgia while listening to songs recommended by the Nostalgia Brain-Music Interface (N-BMI). The red solid and dashed lines represent the decoded nostalgia and regression line during the nostalgic condition, respectively, where the song was recommended to enhance nostalgic feelings (A). The blue solid and dashed lines represent the decoded nostalgia and regression line during the non-nostalgic condition, respectively, where the song was recommended to reduce nostalgic feelings (B). In both conditions, each recommended song was played for 20 s, and Model 1 was updated every 20 s after each song. A total of six songs were recommended over a 120-second period.

Experiment

Participants

Thirty-three participants from Japan, who are native Japanese speakers, took part in the experiment: seventeen older participants (age range: 70–87, M = 80.6, SD = 4.4 years; 3 male) from a Rehabilitation Day Care Center, and sixteen younger participants (age range: 18–47, M = 26.1, SD = 7.4 years; 8 male) from Keio University and NTT Data Institute of Management Consulting. All participants were given both oral and written explanations of the experiment, and each provided written informed consent. The study was approved by the Ethical Committee of Shiba Palace Clinic (approval number: 152115_rn-34967). All procedures were performed in accordance with the Declaration of Helsinki.

The older participants completed the Mini-Cog test63 a simple dementia screening tool that includes a recall test (maximum score: 3) and a clock drawing test (maximum score: 2). The total Mini-Cog score ranges from 0 to 5, with older participants in this study scoring between 0 and 5 (M = 3.3, SD = 1.5 points). Since a total score of 0, 1, or 2 suggests a higher likelihood of clinically significant cognitive impairment, the older participants represented individuals with varying degrees of cognitive impairment.

Experimental procedure

Younger participants were tested in a laboratory, and elderly participants were tested in a Rehabilitation Day Care Center. Both younger and older participants selected three songs that evoked feelings of nostalgia. Participants also provided demographic information (age and gender). After providing their demographic data, the older participants completed the Mini-Cog test. The experimenter then moistened and cleaned each participant’s ears and the back of their necks, where electrodes were attached, before placing the in-ear EEG device.

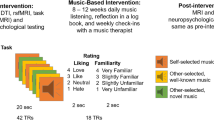

Participants then listened to six songs—three self-selected and three chosen by others—in random order (“Recording” in Fig. 3). The music for the older adult group had acoustic characteristics such as sound quality reminiscent of analog recordings, which could evoke a sense of nostalgia in the younger group through associations with the past. Thus, in the younger group, for each participant, we randomly selected another participant in the same group and assigned that participant’s three self-selected songs as the other-selected songs. In the older group, results of our pilot study indicated that participants often felt nostalgic for many of the self-selected songs of other participants in the same age group. This made it difficult to establish a non-nostalgic state, which was essential for decoder construction. Therefore, to minimize this effect, we assigned the self-selected songs of a randomly chosen participant from the younger group as the other-selected songs. After listening to each song, participants rated their nostalgic feelings, state-level well-being, and subjective memory vividness (see details above). In-ear EEG signals were recorded while participants listened to the songs. Using this data, Models 1 and 2 were generated and their accuracy for each participant was evaluated (“Decoding” in Fig. 3). Model 1 and Model 2 then recommended six songs for two conditions: the “nostalgic condition,” where songs were selected to enhance nostalgic feelings, and the “non-nostalgic condition,” where songs were chosen to reduce nostalgic feelings (“Feedback” in Fig. 3). After listening to the six songs in each condition, participants again rated their nostalgic feelings, state-level well-being, and subjective memory vividness.

Experimental Procedure. Participants listened to six songs—three self-selected and three other-selected nostalgic songs—in random order (“Recording”). After listening to each song, they subjectively rated their nostalgic feelings, state-level well-being, and subjective memory vividness. Using the recording data, Model 1 and Model 2 were created and their accuracy was evaluated for each participant (“Decoding”). Based on these models, six songs were recommended for two conditions: the “nostalgic” condition, where songs were selected to enhance nostalgic feelings, and the “non-nostalgic” condition, where songs were selected to reduce nostalgic feelings (“Feedback”). After each condition, participants again subjectively rated their nostalgic feelings, state-level well-being, and subjective memory vividness.

Analyses

Subjective ratings during recording

The subjective ratings during the recording step were analyzed as follows: First, the VAS ratings obtained for each item were averaged to measure nostalgic feelings, state-level well-being, and subjective memory vividness. Second, the averaged VAS ratings after listening to both self-selected and other-selected songs were calculated for each participant. Third, a Wilcoxon signed-rank test was conducted to compare the VAS ratings for self-selected versus other-selected songs for both the younger and older participant groups.

Evaluation of model accuracy

For Model 1 (Nostalgia Prediction Model), the correlation coefficient between predicted and measured nostalgia values after training was used as a measure of model accuracy. For Model 2 (Nostalgia Decoder), the model was trained on 90% of randomly selected EEG data windows (4-second windows with 50% overlap), and classification accuracy was calculated for the remaining 10% of the data. This was a binary classification task: self-selected nostalgic song or other-selected nostalgic song, with a chance level at 50%. During cross-validation, the optimal lambda (λ) value was chosen based on the lowest testing error. Classification accuracy was calculated for each participant and averaged across both the younger and older participant groups. One-sample t-tests were conducted to determine whether the decoding accuracies for the younger and older groups were significantly higher than the chance level at 50%. Additionally, the Area Under the Curve (AUC) was calculated for each participant and averaged for both groups.

Decoded nostalgia and subjective ratings during feedback

We calculated the mean decoded nostalgia over the entire 120-second period and the mean decoded nostalgia during the final 20 s for both the nostalgia and non-nostalgic conditions for each participant. The value of decoded nostalgia was between 0 and 1. Missing values were excluded when calculating the average value. The mean decoded nostalgia values over the 120-second period and during the last 20 s were compared between the nostalgia and non-nostalgic conditions using Wilcoxon signed-rank tests for both the younger and older participant groups.

The subjective ratings during the feedback phase were analyzed as follows: First, the VAS ratings for each item were averaged to measure nostalgic feelings, state-level well-being, and subjective memory vividness. Second, the averaged VAS ratings after listening to the six songs in the nostalgic and non-nostalgic conditions were calculated for each participant. Third, a Wilcoxon signed-rank test was conducted to compare the average VAS ratings for songs in the nostalgic versus non-nostalgic conditions for both the younger and older participant groups. All data analyses were performed using R version 4.3.3 (https://www.r-project.org) and MATLAB 2023b software (https://www.mathworks.com). A significance level of p < .05 was used for all statistical analyses. Wilcoxon signed-rank tests were employed for variables that did not meet the assumptions for parametric tests, such as normal distribution and/or homogeneity of variances, as assessed by the Shapiro-Wilk and Levene’s tests. Additionally, to examine potential age-related differences in the effects of neurofeedback intervention on nostalgia, state-level well-being, and subjective memory vividness, an aligned rank transformation was applied to each subjective evaluation measure, followed by a mixed-design analysis of variance (ANOVA). To investigate age-related differences, this analysis included only the items from the shortened version of the questionnaire used by older adults, applied to the state-level well-being and subjective memory vividness measures in the younger participant group.

Results

Subjective ratings during recording

For the younger participants, VAS ratings for nostalgic feelings, state-level well-being, and subjective memory vividness were significantly higher after listening to self-selected songs compared to other-selected songs (nostalgic feelings: p < .001, Cohen’s r = .880; state-level well-being: p = .018, Cohen’s r = .704; subjective memory vividness: p < .001, Cohen’s r = .880; see Fig. 4A).

For the older participants, VAS ratings for nostalgic feelings, state-level well-being, and subjective memory vividness were also significantly higher after listening to self-selected songs compared to other-selected songs (nostalgic feelings: p < .001, Cohen’s r = .878; state-level well-being: p < .001, Cohen’s r = .844; subjective memory vividness: p < .001, Cohen’s r = .878; see Fig. 4B).

Subjective visual analog scale (VAS) ratings for nostalgia feelings, state-level well-being, and subjective memory vividness after listening to self-selected and other-selected nostalgic songs. VAS ratings for younger and older participants are shown in panels (A) and (B), respectively. Orange represents the data after listening to self-selected songs, while green represents the data after listening to other-selected songs. Each dot corresponds to an individual participant’s data. Error bars indicate the median ± 1.5 times the interquartile range (IQR). **p < .01, ***p < .001.

Accuracy of Model 1 and Model 2

For Model 1 (Nostalgia Prediction Model, based on acoustics), the mean correlation coefficients between predicted and measured nostalgia values were high for both younger participants (r = .985) and older participants (r = .995). For Model 2 (Nostalgia Decoder, based on EEG data), the mean classification accuracy of the nostalgia decoder was 63.97 ± 16.11 (Mean ± Standard Deviation: SD) for younger participants and 71.52 ± 19.88 (Mean ± SD) for older participants. One-sample t-tests showed that the mean classification accuracy of the nostalgia decoder was significantly higher than the chance level (50%) in both groups (Younger: t(16) = 16.37, p < .01; Older: t(16) = 14.83, p < .01). The mean AUCs for younger and older participants were 0.70 and 0.81, respectively.

Decoded nostalgia during feedback

The mean decoded nostalgia over the 120-second period and during the last 20 s in the nostalgic condition was not significantly higher than in the non-nostalgic condition for the younger participants (p = .080, Cohen’s r = .362, Fig. 5A). In contrast, while the mean decoded nostalgia in the nostalgic condition was not significantly higher than in the non-nostalgic condition during the last 20 s, but was significantly higher over the full 120 s for the older participants (p = .003, Cohen’s r = .683, Fig. 5B).

Decoded nostalgia estimated by Model 2 while listening to songs recommended by the Nostalgia Brain-Music Interface (N-BMI). (A) and (B) show the mean decoded nostalgia over 120 s for the non-nostalgic (green) and nostalgia (orange) conditions in younger (A) and older (B) participants, respectively. Error bars represent the median ± 1.5 * IQR (interquartile range). n.s. = not significant. *p < .05, **p < .01, ***p < .001.

Subjective ratings during feedback

For the younger participants, VAS ratings for nostalgic feelings, state-level well-being, and subjective memory vividness were significantly higher after listening to the recommended songs in the nostalgic condition compared to the non-nostalgic condition (nostalgic feelings: p = .003, Cohen’s r = .711; state-level well-being: p = .002, Cohen’s r = .795; subjective memory vividness: p = .057, Cohen’s r = .483; see Fig. 6A).

Subjective Visual Analog Scale (VAS) ratings for nostalgic feelings, state-level well-being, and subjective memory vividness after listening to songs recommended by the Nostalgia Brain-Music Interface (N-BMI). VAS ratings for younger and older participants are shown in panels (A) and (B), respectively. Orange represents the data after listening to the song recommended to enhance nostalgic feelings (“nostalgic condition”), while green represents the data after listening to the song recommended to reduce nostalgic feelings (“non-nostalgic condition”). Each dot corresponds to data from an individual participant. Error bars represent the median ± 1.5 times the interquartile range (IQR). p < .05, *p < .01, **p < .001.

For the older participants, VAS ratings for nostalgic feelings, state-level well-being, and subjective memory vividness were also significantly higher after listening to the recommended songs in the nostalgic condition compared to the non-nostalgic condition (nostalgic feelings: p < .001, Cohen’s r = .878; state-level well-being: p < .001, Cohen’s r = .878; subjective memory vividness: p < .001, Cohen’s r = .878; see Fig. 6B).

A mixed-design ANOVA for nostalgia, state-level well-being, and subjective memory vividness, using the ART procedure, revealed a significant main effect of participants’ age group for nostalgia, F(1,31) = 4.649, p = .029, ηp2 = 0.100, and subjective memory vividness, F(1,31) = 5.678, p = .024, ηp2 = 0.123, whereas no significant main effect of age was observed for state-level well-being, F(1,31) = 2.080, p = .159. Significant main effects of condition were found for nostalgia, F(1,31) = 105.69, p < .001, ηp2 = 0.636; state-level well-being, F(1,32) = 95.778, p < .001, ηp2 = 0.682; and subjective memory vividness, F(1,31) = 87.550, p < .001, ηp2 = 0.541. Additionally, significant interactions between age and condition were found for nostalgia, F(1,31) = 24.364, p < .001, ηp2 = 0.270; state-level well-being, F(1,31) = 20.214, p < .001, ηp2 = 0.279; and subjective memory vividness, F(1,31) = 40.950, p < .001, ηp2 = 0.336.

Discussion

The aim of this study was to develop the Nostalgia Brain-Music Interface (N-BMI) and evaluate its ability to enhance nostalgic feelings, state-level well-being, and memory recall in both younger and older individuals. The N-BMI followed a three-step process called “Rec-Dec-Back,” which represents (1) recording, (2) decoding, and (3) feedback. In the recording phase, participants listened to both self-selected and other-selected nostalgic songs, rating their nostalgic feelings using the Visual Analog Scale (VAS), while in-ear EEG data were recorded throughout the session. In the decoding phase, models predicting participants’ nostalgic feelings were developed using VAS ratings, auditory features, and in-ear EEG data collected during the recording phase. In the feedback phase, the N-BMI recommended songs designed to either enhance or reduce nostalgic feelings (nostalgic vs. non-nostalgic conditions).

Our results demonstrated that VAS ratings of nostalgic feelings, state-level well-being, and subjective memory vividness were significantly higher in the nostalgic condition compared to the non-nostalgic condition for both younger and older participants. These findings indicate that the N-BMI effectively enhanced nostalgic feelings, state-level well-being, and memory recall across both age groups. While, decoded nostalgia in the nostalgic condition was significantly higher than non-nostalgic condition, only in the older adults group.

Utilizing self-selected songs to enhance and decode nostalgia

We demonstrated that VAS ratings for nostalgic feelings, state-level well-being, and subjective memory vividness were significantly higher after listening to self-selected nostalgic songs compared to other-selected songs in both younger and older participants (Fig. 4), highlighting the importance of considering individual differences when evoking nostalgic feelings. This finding supports the idea that music-evoked nostalgia varies from person to person48,49.

We propose that self-selected nostalgic songs were more closely tied to personal past experiences, inducing greater autobiographical salience compared to other-selected songs. This is consistent with the previous study44 which demonstrated that self-selected music more effectively enhanced autobiographical recall in individuals with Alzheimer’s disease compared to researcher-selected music. Our findings further support the idea that nostalgic feelings are associated with autobiographical prominence29,49. Therefore, we suggest that self-selected nostalgic songs, being deeply connected to personal past experiences, induced greater autobiographical salience and resulted in more vivid autobiographical memories.

We also found that self-selected nostalgic songs enhanced subjective state-level well-being more than other-selected songs. Previous studies have shown that music-evoked nostalgia, accompanied by autobiographical memories, enhances social bonding64 perceived meaning in life65 and self-esteem13,66. Our findings align with these studies, suggesting that music-evoked nostalgia enhances state-level well-being. This is also consistent with the idea that self-selected songs can be effective in clinical settings for supporting memory and state-level well-being in person with amnesia and dementia44,67.

Using in-ear EEG data recorded while participants listened to self-selected and other-selected songs, we developed Model 2 (Nostalgia Decoder), which predicts whether an EEG pattern is more similar to those recorded during self-selected or other-selected song listening. We demonstrated that the classification accuracy of Model 2 was significantly higher than chance level in both younger and older participants. Thus, we suggest that comparing self-selected and other-selected songs is an effective approach for developing an EEG decoder of nostalgic feelings.

The potential of the N-BMI to evoke nostalgia, enhance perceived memory recall, and improve state-level well-being

It is noteworthy that the N-BMI in this study evoked nostalgic feelings by recommending songs from a music database, even though these songs were not necessarily tied to the individual’s direct past experiences. It is possible that songs without prior listening experience evoked nostalgic feelings when recommended by the N-BMI.

Typically, nostalgia is triggered by stimuli that relate to past events and personal experiences. Previous research highlights that familiarity and autobiographical salience are key factors in the intensity of nostalgia49. Therefore, it was expected that the self-selected nostalgic songs in the recording phase of this study—songs directly experienced by the individuals and tied to personal past experiences—would evoke stronger nostalgic feelings. However, the songs recommended by the N-BMI were not necessarily tied to the individual’s direct past experiences. If so, this phenomenon may be caused by the familiarity based on the similarity to their nostalgic songs.

According to the dual-process model of recognition memory, recognition judgement consists of two distinct cognitive processes, “recollection” and “familiarity”68,69. Recollection involves retrieving specific details about a past event, while familiarity refers to a general sense that something has been encountered before, without recalling specific details69. Recollection operates through a threshold process, meaning it either occurs fully or not at all69 and involves conscious retrieval of past events. In contrast, familiarity is shaped by how well the features of a stimulus match previous experiences, with memory traces strengthening gradually through accumulated exposure70.

Since Model 1 in our N-BMI algorithm recommended songs based on acoustic feature similarity, the features of recommended songs matched those of self-selected nostalgic songs that were tied to past experiences. One possible explanation is that the songs recommended by the N-BMI might have evoked nostalgic feelings and enhanced subjective memory vividness primarily through the familiarity process rather than recollection. It could be thought that the recommended songs, with similar acoustic features to participants’ nostalgic songs, may have helped participants access more detailed past memories. This access to memory also could have increased the sense of accumulated familiarity, thereby evoking nostalgic feelings and enhancing subjective memory vividness. However, the study did not measure familiarity with the music, so further experiments are needed to verify the explanation.

The N-BMI not only enhanced subjective memory vividness but also improved state-level well-being in both younger and older participants. These results are consistent with previous research highlighting the role of music and nostalgia in promoting psychological health13,17. In the future, it may be interesting to examine whether the N-BMI not only enhances state-level well-being but also reinforces feelings of social connectedness, increases self-esteem, and reduces negative affect.

Taken together, we suggest that the N-BMI has the potential to evoke nostalgia, enhance memory, and improve state-level well-being by recommending songs from a database, even when participants had no prior listening experience with those songs.

Age-related differences in enhancing and decoding nostalgia

We found that VAS ratings for nostalgic feelings, state-level well-being, and subjective memory vividness were significantly higher after listening to the recommended songs in the nostalgic condition compared to the non-nostalgic condition for both younger and older participants (Fig. 6). However, as indicated by the results of a mixed-design ANOVA, the effect of N-BMI on nostalgia, state-level well-being, and subjective memory vividness depended on age differences. A Wilcoxon signed-rank test also showed that the effects were larger for older participants than for younger participants. Thus, although the N-BMI effectively enhanced subjective nostalgic feelings, state-level well-being, and subjective memory vividness in both age groups, its effect was greater for the older population than for the younger population.

This age-related difference was also reflected in the accuracy of Model 2, the Nostalgia Decoder. Specifically, the mean decoded nostalgia was significantly higher in the nostalgic condition than in the non-nostalgic condition for older participants (Figs. 5B), suggesting that the EEG pattern during the nostalgic condition more closely aligned with that observed while listening to self-selected nostalgic songs. In contrast, there was no significant difference in the mean decoded nostalgia between the two conditions in the younger adult group (Figs. 5A). Thus, the age-related differences in the decoded nostalgia results correspond to those observed in the VAS ratings.

We propose at least four factors to explain these age-related differences. First, variation in acoustic features between older and more recent songs in our music database may have influenced the results. Our database included popular Japanese songs in the hit chart from 2018 to 2023, likely familiar to younger participants, and songs from the 1920s to 1980s, familiar to older participants. Since songs from different eras possess distinct acoustic features, this likely affected the music recommendation process. For older participants, older songs from their youth were ranked higher, while recent songs were ranked lower (Fig. 4B), leading to the recommendation of recent songs in the non-nostalgic condition. It is plausible that older participants did not experience nostalgia in the non-nostalgic condition because recent songs are less likely to evoke nostalgia. Conversely, for younger participants, recent songs were ranked higher, while older songs were ranked lower, leading to the recommendation of older songs in the non-nostalgic condition. Younger participants may have still experienced nostalgia in the non-nostalgic condition, as older songs could be linked to cultural or collective memory. For instance, musical preferences are influenced by the music that was popular during our parents’ adolescence, a phenomenon known as the cascading reminiscence bump71,72. If younger participants were familiar with nostalgic stories related to older songs or had been exposed to those songs at an early age, they may have experienced nostalgia from them, thereby diminishing the difference between the nostalgia and non-nostalgic conditions.

Second, in the recording step, while the other-selected songs for the older group were chosen by participants from the younger group, those for the younger group were selected by another participant within the same group. This difference in the selection process for other-selected songs may have contributed to the distinct neural responses between nostalgic and non-nostalgic states, potentially influencing the accuracy of the decoder. The difference of decoded nostalgia between conditions were only significant in the older group. Because other-selected song in the younger group was chosen in same younger group, it is possible that younger participants felt more nostalgic to other-selected songs than older adults. In the feedback step, songs were recommended based on the decoder’s output. Thus, the difference in how other-selected songs were chosen between age groups may have contributed to the age-related differences in subjective ratings of the recommended songs.

Third, age-related differences in response styles may also have influenced the results. Previous study suggest that aging and cognitive decline may be associated with a tendency toward more extreme response styles73. In the present study, a similar tendency might be visually inferred from the subjective evaluations of older adults, as shown in Figs. 4 and 6. Since the VAS data collected during the recording phase was used to construct Model 1 (the Nostalgia Prediction Model), such a potential bias could have partially contributed to the relatively higher accuracy of the model for older participants compared to younger participants. It can be possible that this tendency might also help account for the more pronounced differences observed in VAS ratings during the feedback phase.

Finally, age-related differences in the subjective vividness of memory recall may have influenced the results. Older adults have been shown to exhibit reduced contextual detail in autobiographical memory compared to younger adults74. However, the subjective vividness of recollected memories—including music-evoked memories—may be comparable between older and younger adults, or even greater in older adults than in younger ones75,76. Therefore, it is possible that a similar pattern may have occurred in the present study.

Limitation and future directions

This study has several limitations in terms of generalizability. The sample size was relatively small, and all older participants were recruited from a day care center, which may limit the diversity of the sample. In addition, certain methodological differences between age groups discussed below may have influenced the results. These factors should be taken into account when interpreting the findings, and caution is warranted in drawing broad conclusions.

Our study used a music database consisting of 7,481 songs from music chart in 2018–2023 for younger participants and 600 songs from 1920s to the 1980s for older participants. This discrepancy in the number and the range of released year of available songs may have influenced the results for younger participants. This song database is large, and many of the songs were from around 2018 to 2023. Thus, this database reduces the likelihood of encountering personally familiar songs, which may, in turn, reduce the evocation of nostalgia. Since familiar songs are more likely to elicit nostalgic responses than unfamiliar ones49 it is possible that this limitation diminished the effect of N-BMI. Thus, N-BMI will be more effective when a more diverse song pool in time would be used.

Also, older participants had to select from a list, while younger adults were allowed to self-select their nostalgic songs on their own. Since the selection was not completely self-selected, the results can only be interpreted to a limited extent as self-selected vs. other-selected. This difference may also contribute to the results. We assumed that songs selected through free recall would evoke more nostalgia than songs limited to a list, but the results showed that the N-BMI effect was smaller in younger participants compared to older participants. Therefore, we consider the impact on the results of this study to be small. On the other hand, it is possible that selecting songs from a list made it difficult to immediately recall nostalgic situations, thereby effectively creating a nostalgic atmosphere. If a more personalized approach is desired, song selection through free recall may be important.

Furthermore, it should be noted that a shortened version of the questionnaire was used for the older adult group in this study. These methodological differences may be related to the results obtained.

In addition, the usefulness of Model 1 and Model 2 was not evaluated separately because this was not the primary focus of the study. Future research is needed to verify their effectiveness, determine the extent to which N-BMI offers benefits compared to conventional music selection based on acoustic similarity in music distribution services, and further improve N-BMI. In this context, one might also wonder how much added value Model 2 provides beyond Model 1. In another study using similar algorithms on music-induced chills, we have demonstrated that combining acoustic and EEG features (Model 1 + Model 2) improves predictive accuracy compared to using acoustic features alone77. However, it remains unclear whether the same advantage holds for predicting music-evoked nostalgia, and further investigation is warranted.

A potential future direction is applying the N-BMI to people with dementia and Alzheimer’s disease. Because N-BMI has a low cognitive load due to not having to select nostalgic songs through free recall, the results of this study suggest that the interface could be particularly beneficial for individuals with severe memory impairments, making it a promising area for future research. Additionally, the N-BMI may hold potential as a non-pharmacological approach to dementia prevention, offering a feasible, and low-side-effect option that can be implemented at home. For example, if a product incorporating this system were to be developed, users would first need to input nostalgic songs. As a result, the difficulty of independent use by individuals with dementia may vary depending on the severity of their symptoms. However, when used with the support of family members or medical staff at home or in daycare settings, the system is expected to demonstrate its maximum effectiveness.

Another future direction is to apply the N-BMI in broader contexts. Since the N-BMI offers a new way of recommending music using an in-ear EEG device, it could be easily adapted for use in the general population in daily life. It has the potential to enhance nostalgia, subjective memory vividness, and state-level in individuals across various demographics. Future studies could explore its impact on emotional health in diverse populations. The development of such technologies could provide significant benefits for individuals with memory and emotional regulation challenges, paving the way for innovative therapeutic interventions in a wider range of contexts.

Conclusion

We developed the Nostalgia Brain-Music Interface (N-BMI) and demonstrated that it enhanced nostalgic feelings, state-level well-being, and memory recall in both younger and older individuals. The N-BMI paves the way for innovative therapeutic interventions, including a non-pharmacological approach for people with dementia, across a wider range of contexts.

Data availability

The datasets analyzed in the current study are available in the Open Science Frameworks (OSF) repository, https://osf.io/yfcuk/.

References

Lutz, W., Sanderson, W. & Scherbov, S. The coming acceleration of global population ageing. Nature 451, 716–719 (2008).

Havighurst, R. J. Successful aging. Gerontologist 1, 8–13 (1961).

World Health Organization. World report on ageing and health (World Health Organization, 2015).

Fleury, J., Sedikides, C., Wildschut, T., Coon, D. W. & Komnenich, P. Feeling Safe and Nostalgia in Healthy Aging. Front. Psychol. 13, 843051 (2022).

Hepper, E. G., Wildschut, T., Sedikides, C., Robertson, S. & Routledge, C. D. Time capsule: Nostalgia shields psychological wellbeing from limited time horizons. Emotion 21, 644–664 (2021).

Hepper, E. G., Ritchie, T. D., Sedikides, C. & Wildschut, T. Odyssey’s end: Lay conceptions of nostalgia reflect its original Homeric meaning. Emotion 12, 102–119 (2012).

Hepper, E. G. et al. Pancultural nostalgia in action: Prevalence, triggers, and psychological functions of nostalgia across cultures. J. Exp. Psychol. Gen. 153, 754–778 (2024).

Leunissen, J., Wildschut, T., Sedikides, C. & Routledge, C. The Hedonic Character of Nostalgia: An Integrative Data Analysis. Emot. Rev. 13, 139–156 (2020).

Zhou, X. et al. The Restorative Power of Nostalgia: Thwarting Loneliness by Raising Happiness During the COVID-19 Pandemic. Soc. Psychol. Person. Sci. 13, 803–815 (2021).

Jiang, T., Cheung, W. Y., Wildschut, T. & Sedikides, C. Nostalgia, reflection, brooding: Psychological benefits and autobiographical memory functions. Conscious. Cogn. 90, 103107 (2021).

Sedikides, C. et al. Nostalgia fosters self-continuity: Uncovering the mechanism (social connectedness) and consequence (eudaimonic well-being). Emotion 16, 524–539 (2016).

Baldwin, M. & Landau, M. J. Exploring nostalgia’s influence on psychological growth. Self and Identity. 13, 162–177 (2014).

Sedikides, C., Rudich, E. A., Gregg, A. P., Kumashiro, M. & Rusbult, C. Are normal narcissists psychologically healthy?: self-esteem matters. J. Pers. Soc. Psychol. 87, 400–416 (2004).

Sedikides, C., Wildschut, T., Routledge, C. & Arndt, J. Nostalgia counteracts self-discontinuity and restores self-continuity. Eur. J. Soc. Psychol. 45, 52–61 (2015).

Synnes, O. Narratives of nostalgia in the face of death: The importance of lighter stories of the past in palliative care. J. Aging Stud. 34, 169–176 (2015).

Juhl, J., Routledge, C., Arndt, J., Sedikides, C. & Wildschut, T. Fighting the future with the past: Nostalgia buffers existential threat. J. Res. Pers. 44, 309–314 (2010).

Wildschut, T., Sedikides, C., Arndt, J. & Routledge, C. Nostalgia: Content, triggers, functions. J. Pers. Soc. Psychol. 91, 975–993 (2006).

van Tilburg, W. A. P., Wildschut, T. & Sedikides, C. Nostalgia’s place among self-relevant emotions. Cogn. Emot. 32, 742–759 (2018).

Jonker, C., Geerlings, M. I. & Schmand, B. Are memory complaints predictive for dementia? A review of clinical and population-based studies. Int. J. Geriatr. Psychiatry. 15, 983–991 (2000).

Ismail, S. et al. Psychological and Mnemonic Benefits of Nostalgia for People with Dementia. J. Alzheimers Dis. 65, 1327–1344 (2018).

Oba, K., Noriuchi, M., Atomi, T., Moriguchi, Y. & Kikuchi, Y. Memory and reward systems coproduce ‘nostalgic’ experiences in the brain. Soc. Cogn. Affect. Neurosci. 11, 1069–1077 (2016).

Reid, C. A., Green, J. D., Wildschut, T. & Sedikides, C. Scent-evoked nostalgia. Memory 23, 157–166 (2015).

Green, J. D., Reid, C. A., Kneuer, M. A. & Hedgebeth, M. V. The Proust effect: Scents, food, and nostalgia. Curr. Opin. Psychol. 50, 101562 (2023).

Koelsch, S. et al. The impact of acute stress on hormones and cytokines, and how their recovery is affected by music-evoked positive mood. Sci. Rep. 6, 23008 (2016).

Linnemann, A., Ditzen, B., Strahler, J. & Doerr, J. M. Nater, U. M. Music listening as a means of stress reduction in daily life. Psychoneuroendocrinology 60, 82–90 (2015).

Pittman, S. & Kridli, S. Music intervention and preoperative anxiety: an integrative review. Int. Nurs. Rev. 58, 157–163 (2011).

Sedikides, C., Leunissen, J. & Wildschut, T. The psychological benefits of music-evoked nostalgia. Psychol. Music. 50, 2044–2062 (2022).

Hébert, S. & Peretz, I. Recognition of music in long-term memory: Are melodic and Temporal patterns equal partners? Mem. Cognit. 25, 518–533 (1997).

Janata, P., Tomic, S. T. & Rakowski, S. K. Characterisation of music-evoked autobiographical memories. Memory 15, 845–860 (2007).

Bloom, P. A. et al. Effects of familiar music exposure on deliberate retrieval of remote episodic and semantic memories in healthy aging adults. Memory 31, 428–456 (2023).

Zucchella, C. et al. The Multidisciplinary Approach to Alzheimer’s Disease and Dementia. A Narrative Review of Non-Pharmacological Treatment. Front. Neurol. 9, 1058 (2018).

Bierman, E. J. M., Comijs, H. C., Jonker, C. & Beekman, A. T. F. Symptoms of anxiety and depression in the course of cognitive decline. Dement. Geriatr. Cogn. Disord. 24, 213–219 (2007).

Ueda, T., Suzukamo, Y., Sato, M. & Izumi, S. Effects of music therapy on behavioral and psychological symptoms of dementia: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Ageing Res. Rev. 12, 628–641 (2013).

Raglio, A. et al. Efficacy of music therapy in the treatment of behavioral and psychiatric symptoms of dementia. Alzheimer Dis. Assoc. Disord. 22, 158–162 (2008).

Särkämö, T. et al. Music, Emotion and Dementia: Insight from Neuroscientific and Clinical Research. Music Med. 4, 153–162 (2012).

Gramegna, S. M. Reminiscence and nostalgia: designing feasible solutions for dementia care. Int. J. Bus. Syst. Res. 16, 199–217 (2022).

Umar Ismail, S., Cheston, R., Christopher, G. & Meyrick, J. Nostalgia as a psychological resource for people with dementia: A systematic review and meta-analysis of evidence of effectiveness from experimental studies. Dementia 19, 330–351 (2020).

Petersen, R. C. et al. Current concepts in mild cognitive impairment. Arch. Neurol. 58, 1985–1992 (2001).

American psychiatric association. Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders, Fifth Edition, Text Revision (DSM-5-TR) (American Psychiatric Association Publishing, 2022).

Foster, N. A. & Valentine, E. R. The effect of auditory stimulation on autobiographical recall in dementia. Exp. Aging Res. 27, 215–228 (2001).

Meilán García, J. J. et al. Improvement of autobiographic memory recovery by means of sad music in Alzheimer’s Disease type dementia. Aging Clin. Exp. Res. 24, 227–232 (2012).

Fraile, E. et al. The effect of learning an individualized song on autobiographical memory recall in individuals with Alzheimer’s Disease: A pilot study. J. Clin. Exp. Neuropsychol. 41, 760–768 (2019).

El Haj, M., Fasotti, L. & Allain, P. The involuntary nature of music-evoked autobiographical memories in Alzheimer’s Disease. Conscious. Cogn. 21, 238–246 (2012).

El Haj, M., Antoine, P., Nandrino, J. L., Gély-Nargeot, M. C. & Raffard, S. Self-defining memories during exposure to music in alzheimer’s disease. Int. Psychogeriatr. 27, 1719–1730 (2015).

Cuddy, L. L., Sikka, R. & Vanstone, A. Preservation of musical memory and engagement in healthy aging and Alzheimer’s disease. Ann. N Y Acad. Sci. 1337, 223–231 (2015).

Ménard, M. C. & Belleville, S. Musical and verbal memory in Alzheimer’s disease: a study of long-term and short-term memory. Brain Cogn. 71, 38–45 (2009).

Jacobsen, J. H. et al. Why musical memory can be preserved in advanced Alzheimer’s disease. Brain 138, 2438–2450 (2015).

Hennessy, S., Greer, T., Narayanan, S. & Habibi, A. Unique affective profile of music-evoked nostalgia: An extension and conceptual replication of Barrett et al.’s (2010) study. Emotion 24, 1803–1825 (2024).

Barrett, F. S. et al. Music-evoked nostalgia: affect, memory, and personality. Emotion 10, 390–403 (2010).

Rao, C. B., Peatfield, J. C., McAdam, K. P. W. J., Nunn, A. J. & Georgieva, D. P. A Focus on the Reminiscence Bump to Personalize Music Playlists for Dementia. J. Multidiscip. Healthc. 14, 2195–2204 (2021).

Murphy, K. et al. Implementation of personalized music listening for assisted living residents with dementia. Geriatr. Nurs. 39, 560–565 (2018).

Ramirez, R., Palencia-Lefler, M., Giraldo, S. & Vamvakousis, Z. Musical neurofeedback for treating depression in elderly people. Front. Neurosci. 9, 354 (2015).

Ehrlich, S. K., Agres, K. R., Guan, C. & Cheng, G. A closed-loop, music-based brain-computer interface for emotion mediation. PLoS One. 14, e0213516 (2019).

Barrett, F. S. & Janata, P. Neural responses to nostalgia-evoking music modeled by elements of dynamic musical structure and individual differences in affective traits. Neuropsychologia 91, 234–246 (2016).

Gemmeke, J. F. et al. Audio Set: An ontology and human-labeled dataset for audio events. in. IEEE International Conference on Acoustics, Speech and Signal Processing (ICASSP) 776–780 (IEEE, 2017)https://doi.org/10.1109/ICASSP.2017.7952261

Hershey, S. et al. CNN architectures for large-scale audio classification. in. IEEE International Conference on Acoustics, Speech and Signal Processing (ICASSP) 131–135 (IEEE, 2017).https://doi.org/10.1109/ICASSP.2017.7952132

Seung-Goo, K., Tobias, O. & Daniela, S. Emotion-relevant Representations of Music Extracted by Convolutional Neural Networks Are Encoded in Medial Prefrontal Cortex. Preprint at https://doi.org/10.6084/m9.figshare.24085104.v2 (2023).

Ueda, K., Imamura, Y. & Ibaraki, T. The development of a eustress sensing system using in-ear EEG. In 43rd Annu. Int. Conf. IEEE Eng. Med. Biol. Soc. (EMBC) (IEEE, 2021). https://doi.org/10.1109/ACII.2019.8925442

Chang, M., Ibaraki, T., Naruse, Y. & Imamura, Y. A study on neural changes induced by sauna bathing: Neural basis of the “totonou” state. PLoS One. 18, e0294137 (2023).

Hepper, E. G. et al. Pancultural nostalgia: prototypical conceptions across cultures. Emotion 14, 733–747 (2014).

Veit, C. T. & Ware, J. E. Jr. The structure of psychological distress and well-being in general populations. J. Consult Clin. Psychol. 51, 730–742 (1983).

Takahashi, M. & Shimizu, H. Do you remember the day of your graduation ceremony from junior high school?: A factor structure of the Memory Characteristics Questionnaire. Jpn. Psychol. Res. 49, 275–281 (2007).

Borson, S., Scanlan, J. M., Chen, P. & Ganguli, M. The Mini-Cog as a screen for dementia: validation in a population-based sample. J. Am. Geriatr. Soc. 51, 1451–1454 (2003).

Cheung, W. Y. et al. Back to the future: nostalgia increases optimism. Pers. Soc. Psychol. Bull. 39, 1484–1496 (2013).

Routledge, C. et al. The past makes the present meaningful: nostalgia as an existential resource. J. Pers. Soc. Psychol. 101, 638–652 (2011).

Hart, C. M. et al. Nostalgic recollections of high and low narcissists. J. Res. Pers. 45, 238–242 (2011).

Arroyo-Anlló, E. M., Díaz, J. P. & Gil, R. Familiar music as an enhancer of self-consciousness in patients with Alzheimer’s disease. Biomed. Res. Int. 2013, 752965. (2013).

Diana, R. A., Reder, L. M., Arndt, J. & Park, H. Models of recognition: A review of arguments in favor of a dual-process account. Psychon. Bull. Rev. 13, 1–21 (2006).

Yonelinas, A. P. The Nature of Recollection and Familiarity: A Review of 30 Years of Research. J. Mem. Lang. 46, 441–517 (2002).

Clark, S. E. & Gronlund, S. D. Global matching models of recognition memory: How the models match the data. Psychon. Bull. Rev. 3, 37–60 (1996).

Krumhansl, C. L. & Zupnick, J. A. Cascading reminiscence bumps in popular music. Psychol. Sci. 24, 2057–2068 (2013).

Jakubowski, K., Eerola, T., Tillmann, B., Perrin, F. & Heine, L. A Cross-Sectional Study of Reminiscence Bumps for Music-Related Memories in Adulthood. Music Sci. 3 (2020).

Schneider, S. Extracting Response Style Bias from Measures of Positive and Negative Affect in Aging Research. J. Gerontol. B. Psychol. Sci. Soc. Sci. 73, 64–74 (2017).

Levine, B., Svoboda, E., Hay, J. F., Winocur, G. & Moscovitch, M. Aging and autobiographical memory: dissociating episodic from semantic retrieval. Psychol. Aging. 17, 677–689 (2002).

Jakubowski, K. & Ghosh, A. Music-evoked autobiographical memories in everyday life. Psychol. Music. 49. 649-666 (2021).

Johnson, M. K., Kuhl, B. A., Mitchell, K. J., Ankudowich, E. & Durbin, K. A. Age-related differences in the neural basis of the subjective vividness of memories: evidence from multivoxel pattern classification. Cogn. Affect. Behav. Neurosci. 15, 644–661 (2015).

Kondoh, S. et al. A chill brain-music interface for enhancing music chills with personalized playlists. bioRxiv 2024.11.07.621657 https://doi.org/10.1101/2024.11.07.621657 (2024).

Acknowledgements

We would like to thank Dr. Seung-Goo Kim for his warm advice on the study.

Funding

This study was financially supported by Towa Pharmaceutical Co., Ltd (https://www.towayakuhin.co.jp/english/). The funders had no role in study design, data collection and analysis, decision to publish, or preparation of the manuscript.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

YS: conceptualization, data curation, formal analysis, methodology, visualization, writing – original draft, writing – review & editing, validation. TK: conceptualization, methodology, data curation, writing – review & editing. SK: writing – review & editing. TE: writing – review & editing. SS: data curation, writing – review & editing. YI: conceptualization, writing – review & editing. YN: conceptualization, writing – review & editing. SF: conceptualization, software, methodology, writing – original draft, writing – review & editing. TI: conceptualization, data curation, formal analysis, visualization, methodology, software, writing – review & editing.

Corresponding authors

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors have read the journal’s policy and have the following competing interests: TI is employed by the company NTT Data Institute of Management Consulting, Inc and VIE, Inc. YS, TK, SK, TE, SS, YI, YN and SF are employed by VIE, Inc. The authors would like to declare the following patents associated with this research: WO2023074756. The authors would like to declare the following products in development associated with this research: “Uta-Memory”. This does not alter our adherence to the journal’s policies on sharing data and materials.

Additional information

Publisher’s note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Supplementary Information

Below is the link to the electronic supplementary material.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if you modified the licensed material. You do not have permission under this licence to share adapted material derived from this article or parts of it. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Sakakibara, Y., Kusutomi, T., Kondoh, S. et al. A Nostalgia Brain-Music Interface for enhancing nostalgia, well-being, and memory vividness in younger and older individuals. Sci Rep 15, 32337 (2025). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-14705-6

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-14705-6