Abstract

Forest carbon sink potential assessment in arid regions remains a critical challenge for climate change mitigation. This study integrates multi-source remote sensing and forest inventory data to model Xinjiang’s forest age and carbon density (2019 baseline: 186.76 Mg/hm2 biomass, 93.38 Mg/hm2 carbon density, 46-year average age), revealing a south-to-north “low-high-low” spatial pattern. Using predictive models excluding anthropogenic and natural disturbances, we project forest carbon stock to reach 203.71 ± 2.31 Tg C by 2030 and 283.08 ± 4.23 Tg C by 2060, with declining carbon sink rates (3.67 ± 0.57 Tg C/a in 2019–2030 vs. 2.65 ± 0.56 Tg C/a in 2031–2060). Notably, Xinjiang’s forests could offset 14.6% and 9.5% of regional CO2 emissions during these periods. Economic cost analysis via panel fixed benefit modeling identifies afforestation suitability in Northeast Xinjiang, while conservation measures are prioritized elsewhere, particularly in high-elevation ridge zones. This research provides a methodological framework for arid region carbon sink enhancement and informs region-specific forest management strategies under climate change.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

As the primary carbon storage system in terrestrial ecosystems, forests have become a hotspot and a challenge for current research based on accurate estimation and prediction of forest carbon stock and then realising the enhancement of carbon sinks1,2. Some scholars have used the forest stock conversion method to estimate forest biomass, carbon stock and carbon sequestration potential in China and provinces based on the data from the national continuous forest inventory3. Although the method is highly accurate, it is difficult to obtain data and lacks spatial continuity. Currently, LiDAR data and multi-source remote sensing techniques are extensively employed to estimate and predict forest stock, biomass, and carbon reserves at the stand scale and regional scale3,4. However, due to the complexity of forest structure, remote sensing data are limited by issues such as spatial and temporal resolution and mixed pixels5resulting in great uncertainty in the accuracy of carbon stock estimation results. Therefore, the estimation of forest carbon stock by integrating forest survey data and remote sensing data has great potential.

Some studies have shown that appropriately increasing forest harvesting may increase carbon sequestration, but there are tree species and regional variability in the spatial distribution of its harvestability and the time point of forest age6. Forestry carbon sink projects have synergistic benefits such as mitigating climate change, promoting economic growth and improving air quality, and can maximise forest carbon sequestration potential through optimal management3. Forest carbon sequestration is crucial for carbon emission reduction in China, but existing studies still do not adequately consider the costs of different forest management measures7. Therefore, in-depth studies on forest management strategies are needed to maximise the potential of forest management practices for carbon sequestration.

Xinjiang is located in a typical arid region with a fragile ecological environment. Although the forest area in Xinjiang is not large relative to the eastern part of China, it plays a key role in maintaining the ecological security of the entire arid zone ecosystem. In recent years, some studies on forest carbon cycle in Xinjiang have been conducted8. However, previous studies on the estimation and prediction of forest carbon stock in Xinjiang have mainly focused on individual tree species in the Altai Mountains, Tien Shan Mountains, and the Tahe River Basin, and all of them have used sample plots to obtain data such as diameter at breast height (DBH) forcarbon stock estimation8,9. So far there are limitations in the research on the prediction of total forest carbon stock and carbon sink enhancement methods in Xinjiang, especially the lack of accurate quantitative evaluation of the actual contribution of forest carbon sink enhancement management measures in Xinjiang7,10. Therefore, it is of practical significance to carry out carbon stock prediction and carbon sink potential enhancement research on Xinjiang forests by combining remote sensing data and forest inventory data, and it is also crucial to formulate effective regional forest management and conservation strategies on this basis.

In this study, forest age and carbon density estimation models of Xinjiang forests were established by integrating forest inventory data and tree height data obtained by LiDAR. The carbon stock and sink rate of Xinjiang’s forests in 2030 and 2060 were predicted with the exclusion of anthropogenic and natural disturbances. To enhance the carbon sink capacity of Xinjiang’s forests, a panel fixed-effects model was applied to estimate the economic costs of afforestation and conservation in five regions of Xinjiang by integrating multi-source remote sensing data and panel data. For regions with low conservation costs, logging should take into account the climatic period and growth inflection point, while for regions requiring afforestation, the growth environment of different forest types should be taken into account, so as to select forest types with a longer climatic period and a better ability to adapt to the climate for planting. This study is of great theoretical and practical value for understanding the dynamics of forest ecosystems in Xinjiang, and for formulating effective strategies for forest management and carbon sink growth.

Materials and methods

Study area

Xinjiang is located in the centre of the Eurasian continent, and as a unique geographical and ecological region in western China, its forest ecosystems play an important role in the global and regional carbon cycle11. Forests in the region not only help to absorb atmospheric carbon dioxide and mitigate the greenhouse effect, but are also important for maintaining regional biodiversity and ecological balance11,12. By predicting and studying the carbon sink potential of Xinjiang’s forests, we can better understand the performance of the region’s forest ecosystems and their contribution to the carbon cycle under current and future climate change scenarios. Despite its small forest area, it plays a crucial role in carbon sequestration12,13. This land is sparsely populated with little precipitation, showing a typical arid climate. According to statistics, the forest area in Xinjiang is only 8 × 1010 m2 (see Fig. 1), which mainly consists of 4 major parts: natural forests in mountainous areas, oasis protection forests, economic forests, and natural desert river valley forests13.

In this study, to explore the economic benefits of forest management measures in Xinjiang, Xinjiang was divided into Northwest (including the city of Karamay, Bortala Mongol Autonomous Prefecture, Ili, Tacheng and Altay regions, NW), Central (including the cities of Urumqi and Changji, C), Northeast (including the cities of Turpan and Hami regions, NE), and Southwest (including the regions of Aksu, Kizilsu Kirghiz Autonomous Prefecture and Kashgar, SW), Southeast (including Hotan and Bayinbuluk regions, SE) in five regions.

The four main forest types in Xinjiang include ENF, DNF, DBF, and MF. Among them, evergreen coniferous forests, with Picea schrenkiana as the dominant species, are distributed on the north and south slopes of NW and C, with slow growth and high density of trees; Deciduous coniferous forests with Siberian larch (Larix sibiricaLedeb) as the dominant species, distributed in the NW, rapid growth and adaptability; DBF with poplar (Populus euphratica Oliv) as the dominant species, distributed in the Tarim River Basin, rapid growth and the average age of the tree is relatively small; mixed coniferous and broad-leaved forests with Siberian spruce (Abies sibirica Ledeb) and European poplar (PopulusL.) mixed dominant, concentrated in the south slope of SE and the southeastern part of the SW, mostly sparse and short, mostly sparse and short1,14. Obovate mixed with European poplar (PopulusL), concentrated in the south slope of SE and the southeastern SW, mostly sparse and small3,15.

Overview of Study Area Location (this figure is generated in ArcGIS10.8 software, http://www.esri.com/software/arcgis).

Data acquisition and processing

As shown in Table 1, the remote sensing data used in this study include: 2019 global forest tree height data at 30 m spatial resolution, vegetation phenology period length, vector map of the administrative boundary of Xinjiang, land use data, 1,201 sample plots data from the 2011 forest inventory, forest type data from the Type II survey, Net Primary Productivity (NPP) data, DEM data, meteorological data (monthly scale air temperature, precipitation ), Net Primary Productivity (NPP), atmospheric CO2 concentration and CO2 emission data. In this study, the remote sensing data were processed with uniform projection and spatial resolution. Firstly, all remote sensing data projections were unified as WGS_1984_UTM_Zone_45N using ArcGIS 10.8 software, and the remote sensing data were cropped according to the vector map of the administrative boundary of Xinjiang in order to obtain the remote sensing data in the Xinjiang range. Subsequently, the tree height, class II forest type data, net primary productivity (NPP) data, atmospheric CO2 concentration and CO2 emission data were interpolated to a resolution of 500 m in space. The data were then used as the basis of the spatial resolution. Finally, considering the influencing factors such as temperature, precipitation, vegetation phenological period length and standardised precipitation evapotranspiration index (SPEI), they were uniformly adjusted to a spatial resolution of 0.05° by the resampling method.

Panel data include: gross domestic product (GDP), regional population, afforestation area, forest conservation area and forestry fixed asset investment. And the data related to social economy. In this study, the investment in forestry fixed assets is represented by its accumulated value of ‘investment in forestry fixed assets’. Specifically, this investment is inflation-adjusted using the fixed asset investment price index, with 2001 as the base year.

Research methodology

Methods for estimating forest biomass and forest age

Forest biomass is the aboveground biomass of the forest, including the biomass of stem, branches, leaves, roots, flowers and fruits. Forest age generally refers to the average age of a forest stand12and in this study, it refers to the average age of all forests within a forest image element. Studies indicate a good statistical relationship linking tree height, diameter at breast height, and forest biomass16. The power function model was found to be more suitable to simulate the relationship among tree height, diameter at breast height and forest biomass in Xinjiang forest by comparison and analysis by previous authors14. In this study, the sample tree heights of 1–56 m were selected based on the range of RMS values of NNGI tree height raster data, and the Xinjiang forest survey data (835) of sample biomass and stand age were randomly selected using forest types, and then the biomass and stand age estimation models of four forest types in Xinjiang established by Zhang were optimised using Matlab’s fitnlm function16. This paper developed a high-accuracy estimation model applicable to the biomass and age of Xinjiang’s four forest types. Using this model, the study evaluated the region’s forest biomass, carbon density, and age, producing corresponding spatial distribution data. According to the optimised model, forest biomass multiplied by 0.5 (including carbon factor) was used to estimate forest carbon stock in Xinjiang, and carbon stock per unit area was carbon density15. In this paper, on the basis of previous studies, the logistic model that passed the significant correlation test was selected as the optimal model, and then the model of carbon density and forest age was constructed as follows:

Where: D is the average forest diameter at breast height; H is the average forest height; B is the forest biomass, Mg/hm2; Cρ is the forest carbon density, Mg/hm2; a1, a2, a3,b, and c are the relevant parameters, A is the age of the forest, in years; B is the forest biomass, in Mg/hm2; and b1, b2, and b3 are the parameters related to the forest type.

Carbon sink rate estimation method

Carbon sink rate indicates the amount of change in carbon stock at a location during a certain period of time (relative to the amount of change in carbon stock in the base year), and the size of its value can indicate the speed of carbon sink17and in this paper, we take 2019 as the base year for calculating the carbon sink rate, and the specific formulas are as follows:

Where ∆C is the carbon sink rate (Tg C yr−1), \(\:{C}_{{t}_{2}}\) and \(\:{{C}_{t}}_{1}\) are the carbon stock (Tg C) in t2 and t1, respectively, and t1 (year) and t2 (year) are different periods.

Partial correlation analysis

In the correlation analysis of forest carbon stock to climate factors (temperature, precipitation and SPEI) and vegetation phenology in this study, mean annual temperature, mean annual precipitation and SPEI-12, and the length of vegetation phenology period were selected as the influencing factors18. For the bias correlation analyses between phenology and climate factors, forest carbon stock and impact factors, other factors were excluded and bias correlation coefficients were calculated as follows:

where Ry, x,z.w represents the partial correlation between variables x and y, controlling for the effects of variables z and w. Ry, x.z represents the partial correlation between variables x and y, controlling for the effect of variable z. Ry, w.z represents the partial correlation between variables y and w, controlling for the effect of variable z. Rx, w.z represents the partial correlation between variables x and w, controlling for the effect of variable z.

Precision evaluation

The parameters and applicability of the models were analysed and validated using four assessment metrics: coefficient of determination (r2, variance (S2, mean absolute error (MAE) and root mean square error (RMSE). When P > 0.05 indicates that there is no significant difference in the model, P < 0.05 indicates that there is a significant difference, and P < 0.01 indicates that there is a highly significant difference19. The specific formula is as follows:

where n denotes the number of samples, Xi denotes the sample value in year i, and \(\bar{X}\) represents the sample mean in year n. Xobs, i and Xmodel, i represent the measured and modelled estimates in year i, respectively. \(\overline{{X_{{{\text{obs,i}}}} }}\) observation estimates the mean value in year i.

Carbon sequestration estimation in forest vegetation

Vegetation absorbs carbon dioxide from the atmosphere, produces organic substances such as glucose through photosynthesis, and releases oxygen. The chemical reaction can be expressed as: 6CO2 + 6H2O → C6H12O6 + 6O2, which means that 1.62 g of carbon dioxide are fixed per gram of dry matter formed by vegetation. Vegetation NPP indicates the amount of dry organic matter generated by green plants per unit area20,21net of autotrophic respiration2021. Moreover, approximately 45% of the total NPP is carbon content in the dry matter. The following equation is used to determine vegetation carbon sequestration.:

where CS denotes the carbon captured by vegetation (g C/m2) and NPP is the carbon content in the dry matter of vegetation (g C/m2)21. To obtain the amount of vegetation carbon sequestration in forests, we obtained forest land data from Chinese land use records. Then, we obtained the NPP on forest land by employing the raster calculation tool in ArcGIS 10.8. Finally, based on the area of forest land, we determined the total carbon sequestration of forest vegetation.

where CSF denotes the carbon sequestered by forest vegetation (Tg C, 1 Tg C = 1012 g C) and S represents the forest area (m2).

Construction of panel fixed effects models

The panel fixed effects model was used in this study for two reasons. Firstly, it addresses the issue of biased coefficient estimates from omitted variables and allows for an accurate estimation of the marginal contributions of afforestation and conservation to carbon sequestration in forest vegetation. Second, regional dummy variables can be introduced to improve estimation robustness and reduce inefficiency caused by subsample regression21,22. Considering that afforestation and forest conservation have lagged effects on vegetation carbon sequestration, this study also examined the delayed effects of afforestation and forest conservation on CSF. In particular, we combined afforestation and forest conservation with different lags while keeping other variables under control and compared the significance of their marginal contributions to CSF. Therefore, in this study, we used Eviews 12 software to construct a fixed-benefit model for the paneldata of Xinjiang prefecture-level cities from 1996 to 2019.

In Eq. (13), CSF represents the carbon sequestration of forest vegetation, affor represents afforestation, and tend represents forest conservation. In addition, fixin represents the investment in forestry fixed assets, GDP represents the gross domestic product of each prefecture-level city in Xinjiang, popu denotes the population size of each prefecture-level city in Xinjiang, tmp is the average annual temperature, and pre is the average annual precipitation. Moreover, β1 is the marginal contribution of afforestation efforts in forests, β2 is the marginal contribution of forest conservation measures, α is the parameter of the variable, i represents prefectural cities, t is the year, and µ is the fixed effect, which \(\delta\) is the error term.

Costing of carbon sequestration by vegetation

In this study, the cost of vegetation carbon sequestration for afforestation and conservation was calculated separately, taking into account the economic value of carbon sinks and the link between capital investment and carbon sequestration per unit area, as demonstrated in the Eq. (14)21,23:

In Eq. (14), c denotes the cost of carbon sequestration by vegetation (US$/t, 1t = 106g), I denotes the capital cost per unit area (US$/104 ha), and β denotes the marginal effect of the forest measure to CSF (Eq. 13; Tg C/104 ha). Here, k denotes the forest measure and is a binary variable, 1 denotes afforestation, 2 denotes forest conservation, and j denotes area.

Results and analyses

Estimation of forest age and carbon density in Xinjiang

Forest biomass estimation

In this paper, the optimal estimation models and parameters of diameter at breast height (DBH) and biomass were obtained for evergreen coniferous forest (ENF), deciduous coniferous forest (DNF), deciduous broadleaf forest (DBF) and mixed coniferous-broadleaf forest (MF) in Xinjiang. As shown in Tables 2 and 3 (n is the number of sample plots/number), the optimal estimation models screened had r2 greater than 0.785 and P = 0.000, and the RMSE ranged from 1.873–3.165 (Table 2) to 12.204–19.459 (Table 3), respectively, and all passed the significance test.

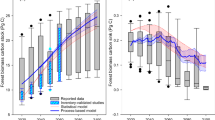

Modelling the estimation of forest carbon density and stand age

In this study, the optimal growth models and parameters of forest age and carbon density for four forest types in Xinjiang were obtained (Table 4), and the r2 of the models were all greater than 0.864, P = 0.000 (n denotes the number of sample plots/number), and the RMSE ranged from 6.53 to 14.1, which passed the significance test. The trends of carbon density changes with forest age for the four forest types in Xinjiang are shown in Fig. 2. It can be seen that with the increase of forest age, the carbon density of all four forest types gradually increased, and when the forest age is close to the mature forest, the carbon density gradually tends to stabilise. From the time taken for the carbon density of the four forest types to stabilise and the size of the carbon density after stabilisation, it can be seen that evergreen coniferous forests grow relatively fast, while mixed coniferous forests and deciduous broad-leaved forests, despite their adaptability to the environment, grow mainly in the vicinity of the more arid Tarim Basin, which in turn grows relatively slowly.

Changes in Forest Carbon Density with Forest Age in Xinjiang in 2019 (this figure is generated in EXCEL software, https://www.microsoft.com/en-us/microsoft-365/excel).

Characteristics of the spatial distribution of forest carbon age and stocks

As can be seen from Fig. 3, the average age of the four forest types in Xinjiang in 2019 estimated by this paper is 46 years. According to the division of forest age groups in the Technical Provisions for Continuous Inventory of National Forest Resources, most of the forests with an age of 34–71 years obtained in this paper belong to middle-aged forests, which are mainly distributed in the northern slopes of the SW and NW,accounting for about 72% of the total area of forests in Xinjiang, and the overall presentation of the age of the forests in the west is higher than that of the forests in the east, among which the age of the evergreen coniferous forests is The age of evergreen coniferous forests is generally higher. The average age of evergreen coniferous forests and deciduous coniferous forests is 73 years and 55 years respectively. The average age of deciduous broad-leaved forests is 39 years, and most of them belong to recent mature forests according to forest groups, dominated by poplar, elm and willow, mainly distributed on both sides of the Tarim River. The average age of mixed coniferous and broad-leaved forests is 62 years, and most of them belong to recent mature forests, with a smaller area and mainly distributed in the NW and SW.

On the basis of estimating the spatial distribution map of forest biomass in Xinjiang in 2019, we calculated and obtained the spatial distribution map of forest carbon density in Xinjiang from Fig. 3, we can see that the average carbon density of the four forest types in Xinjiang in 2019 was 93.38 Mg/hm2. Among them, the carbon density of 50–118 Mg/hm2 of the forest area is 1.51 × 1010 m2, accounting for about 84% of the total forest area in Xinjiang. The average carbon densities of evergreen coniferous forests and deciduous coniferous forests were 98.20 Mg/hm2 and 97.99 Mg/hm2, respectively, and the average carbon densities of deciduous broad-leaved forests and mixed coniferous forests were 50.31 Mg/hm2 and 88.32 Mg/hm2, respectively. The spatial distribution of forest carbon density in Xinjiang was uneven, similar to the spatial distribution characteristics of forest age.

From Figs. 3, it can be seen that forest biomass and carbon stock in Xinjiang are similar in spatial distribution, which is specifically reflected in the low-to-high distribution characteristics from south to north, and the average biomass and average carbon stock of the four forest types in Xinjiang in 2019 were 186.76 Mg/hm2 and 166.40 Tg C, respectively. among them, the carbon density of 100–236 Mg/hm2, the forest area was 1.51 × 1010 m2, accounting for about 84% of the total forest area in Xinjiang. The average carbon densities of evergreen coniferous forests and deciduous coniferous forests were 196.40 Mg-hm-2 and 195.98 Mg/hm2, respectively, and the average carbon densities of deciduous broad-leaved forests and mixed coniferous forests were 100.62 Mg/hm2 and 166.64 Mg/hm2.

Spatial distribution of forest age, carbon density, biomass and carbon stock in Xinjiang forests (this figure is generated in ArcGIS10.8 software, http://www.esri.com/software/arcgis).

Forecasting and challenges of forest carbon stock and sink rates in Xinjiang

Under the scenarios of excluding anthropogenic and natural disturbances, assuming that the future forest area in the study area remains unchanged and the forest age grows normally, based on the spatial distribution map of forest age in Xinjiang and the growth model of forest age and carbon density of the four forest types, the carbon density of the study area was predicted to obtain the carbon density in 2030 and 2060, and then the carbon density was calculated into the carbon stock and the rate of carbon sinks (Table 5). As shown in Table 5, the carbon stock of Xinjiang forests in 2030 and 2060 were (203.71 ± 2.31) Tg C and (283.08 ± 4.23) Tg C, respectively, and the carbon stock of different forest types in 2030 and 2060 were ENF > DNF > DBF > MF. Compared with 2030, the carbon sink rates of ENF, DNF, DBF and MF in 2060 decreased by 0.58 ± 0.13 Tg C a−1, 0.21 ± 0.03 Tg C a−1 0.20 ± 0.03 Tg C a− 1, 0.04 ± 0.01 Tg C a−1. In conclusion, the above results indicate that Xinjiang forests have a large potential for carbon sequestration in the future, but the decline in the rate of carbon sinks in Xinjiang forests after 2030 adds uncertainty to the future carbon sinks in Xinjiang forests.

Based on the data of carbon dioxide concentration and carbon dioxide emission in Xinjiang from 2001 to 2020, the time series plot of carbon dioxide concentration and carbon dioxide emission data from 2021 to 2060 was estimated using trend regression analysis. As shown in Fig. 4, the CO2 concentration in Xinjiang from 2001 to 2020 shows a continuous linear growth trend, while the CO2 emission also exhibits a fluctuating upward trend. Xinjiang forests can absorb 14.6% and 9.5% of CO2 emissions in 2019–2030 and 2031–2060. The RMSE of CO2 concentration and CO2 emissions were 18.225 ppm and 271.449 Mt, respectively. The slowdown in the rate of carbon sinks in Xinjiang’s forests poses a significant challenge to achieving the 2060 carbon neutrality target under the natural scenario.

Relationship between forest growth inflection points and carbon stock

As shown in Fig. 5, the growth curves of the four forest types in Xinjiang all show an ‘S’ shape, which indicates that the curves grow slowly at the initial stage, then accelerate and eventually stabilise. Specifically, DBF reached the growth inflection point at the earliest, i.e., the forest age was 63 years, and the growth rate of carbon density after reaching the growth inflection point was 0.02 Mg/hm2/yr, which was 84% lower than that before reaching the growth inflection point. The growth inflection point of MF was reached in 112 years, and the carbon density growth rate after reaching the growth inflection point was 0.08 Mg/hm2/yr, which was 93% lower than that before reaching the growth inflection point. the growth inflection points of ENF and DNF corresponded to similar stand ages, 97 and 100 years, respectively. 0.12 Mg/hm2/yr, which were 94% and 93% lower than the growth rates before reaching the growth inflection point, respectively. The carbon density growth rates of ENF, DNF, DBF and MF were 1.75, 1.73, 1.41 and 1.21 Mg/hm2/yr, respectively, before reaching the growth inflection point.

After 2030, the carbon sink rate of Xinjiang’s forests began to show a decreasing trend. In this study, combining the forest growth curve and selecting two time points, 2030 and 2050, forests whose age exceeds the inflection point of forest growth are defined as deforestation targets. As seen in Table 6; Fig. 6, the carbon sink rate of the four forest types is significantly enhanced when considering the post-cutting scenario. Specifically, compared with the case without logging, the carbon sink rate after logging increased by 0.01–0.1 Tg C/a. Here, ENF_M, DNF_M, DBF_M and MF_M represent evergreen coniferous forest, deciduous coniferous forest, deciduous broadleaf forest and mixed coniferous and broadleaf forest after logging, respectively.

Inflection Points of Forest Growth in Xinjian (this figure is generated in EXCEL software, https://www.microsoft.com/en-us/microsoft-365/excel).

Influence of different factors on the change of forest carbon stock in Xinjiang

This study extracted phenological characteristics of four forest types in Xinjiang (Table 7). The start of the growing season (SOS) for forest ecosystems primarily occurs between mid-May (day 129–141) and late August (day 211–235), with the longest growing season lengths (LOS) observed in ENFand DBF. In analyzing the relationship between LOS and carbon stocks (Fig. 7), it is essential to account for the constraints imposed by the arid environment of Xinjiang. While a longer growing season could theoretically extend the time window for photosynthesis and carbon sequestration, water availability is the primary limiting factor for forest productivity in this region. Thus, the observed correlation between LOS and carbon stocks (strongest for DBF, followed by MF, ENF, and DNF) is a secondary phenomenon constrained by water stress.

Specifically, LOS itself is not the primary driver of differences in carbon stocks. Under water-limited conditions, the extension of the growing season may exacerbate water stress and increase respiratory carbon losses throughout the extended period, failing to proportionally enhance net carbon gains and potentially even reducing carbon stocks. In contrast, carbon stocks are primarily regulated by water availability, as evidenced by significant positive correlations with precipitation and the standardized precipitation evapotranspiration index (SPEI). Precipitation shows a significant positive correlation with carbon stocks for all forest types, with DBF exhibiting the highest sensitivity. SPEI, which reflects drought conditions, also demonstrates significant correlations, albeit slightly weaker than precipitation, further confirming the role of drought in shaping carbon dynamics. Notably, ENF shows the highest sensitivity to temperature, while DNF exhibits a unique negative correlation with precipitation, warranting further investigation.

The relationship between LOS and carbon stocks likely reflects species-specific phenological adaptations and their interactions with local water conditions. For instance, the positive correlation for DBF may indicate that extending the growing season is effective under relatively favorable water conditions. However, the strength of this relationship is significantly weaker compared to the fundamental dependence of carbon stocks on precipitation and SPEI.

Therefore, for afforestation practices in Xinjiang, species selection should prioritize their tolerance to water stress, based on responses to SPEI and precipitation. LOS characteristics can serve as secondary reference indicators, particularly for distinguishing species with similar drought tolerance. Under conditions where water availability is consistently sufficient throughout the extended growing season, longer potential photosynthetic periods may provide certain advantages.

depicts the partial correlation coefficients of different forest types in response to climate and phenological factors. The orange, green, and magenta colors represent the correlations of phenology with temperature, precipitation, SPEI, and phenological period length for different forest types. *** stands for p < 0.01, ** stands for p < 0.05, * stands for p < 0.1.

Spatial distribution of deforestable areas

Through in-depth analyses, this study meticulously divides the deforestationable areas of Xinjiang’s forests, as shown in Fig. 8, into three main deforestation areas, representing the forest resources distributed within the NW, SW and C, respectively. These areas cover 95% of the total forest area in Xinjiang, and the deforestationable areas are concentrated in the ridges at higher altitudes. From an ecological point of view, these areas are ideal for sustainable utilisation and management because of their favourable forest growth environment and high ecosystem stability and complexity. In determining the harvestable areas, we used a growth modelling relationship based on forest age and carbon stock, defining forest age after the growth inflection point as harvestable forest. This approach integrates the dynamics of forest growth and the process of carbon stock accumulation to ensure the scientific validity and sustainability of the harvestable area.

As shown in Table 8, the forest area of evergreen coniferous forests that can be felled in 2030 and 2050 is 11.25 × 107 m2 and 31.30 × 107 m2, respectively, accounting for 1% and 4% of the total area of evergreen coniferous forests. The forest area of deciduous coniferous forests that can be felled in 2030 and 2050 is 15.10 × 107 m2 and 96.78 × 107 m2, respectively, accounting for In 2030 and 2050, the forest area that can be felled in deciduous broad-leaved forests is 28.30 × 107 m2 and 99.83 × 107 m2 respectively, accounting for 18% and 62% of the total area of deciduous broad-leaved forests respectively. The forest area that can be felled in mixed coniferous and broad-leaved forests is 3.53 × 107 m2 and 9.20 × 107 m2 respectively, accounting for 3.53 × 107 m2 and 9.20 × 107 m2 respectively, accounting for 9.20 × 107 m2 respectively. 107 m2 in 2030 and 2050, accounting for 4% and 11% of the total area of mixed coniferous and broad-leaved forests, respectively.

Spatial Distribution of Potential Harvesting Areas in Xinjiang Forests for 2030 and 2050 (this figure is generated in ArcGIS10.8 software, http://www.esri.com/software/arcgis).

Economic benefits of different sink enhancement measures for forests

Lagged benefits of different sink enhancement measures for forests

As shown in Table 9, we controlled for control variables when estimating the lag period for each silvicultural measure. affor_1 denotes the silvicultural area within a lag period. tend_1 represents the forested area with a lag period, and so on. Firstly, we examined the duration of forest measures’ impact on CSF. Afforestation’s effect on CSF became insignificant after 5 lags, while forest conservation’s effect became insignificant after 2 lags, suggesting that afforestation has a significantly longer impact on vegetation carbon fixation compared to forest conservation. Secondly, we analyzed the trends in the marginal contribution of forest measures to CSF. Overall, the CSF for afforestation reached its maximum at a lag period of about 4, while the CSF for forest conservation reached its maximum at a lag period of about 1. Therefore, affor and tend in Tables 4 and 5 are the contribution of afforestation with 4 lags and that of nourishment with 1 lag, respectively.

Costing of different measures to increase the remittances of forests

As shown in Table 10, fixed investment showed a highly significant positive benefit with CSF, indicating that the higher the investment, the more forestry equipment was purchased, increasing productivity and thus forest carbon sequestration. While forest carbon sequestration showed significant negative benefits with GDP and population of the city, although population growth raised the demand for forest products, which in turn heightened the pressure on land capacity, it also caused a shift in the types of forested land., the presence of irrationality in the planning of green spaces may lead to a decrease in CSF. The reason for the low significance of temperature and precipitation in relation to CSF may be due to the fact that forests are suitable only at the right range.

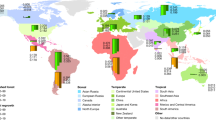

As shown in Fig. 9 the CSF cost of nurturing presents the characteristics of SW and NE being higher than other regions, showing strong spatial heterogeneity. In contrast, the CSF cost of silviculture exhibits the characteristics of high in the north and low in the south. The cost of afforestation in the NW, C and NE is generally low, with the afforestation cost in the NW region being about US$52.19/t, while the cost of afforestation in the SW and SE regions is generally high, with the cost of afforestation in the SE region being as high as US$624.23/t. The low cost of forest afforestation is mainly concentrated in the NW, C and SE regions, with the cost of afforestation in the C region being only US$9.29/t, while the cost of afforestation in the SW and The cost of afforestation is generally higher in the north-eastern region, with US$631.27/t in the south-western region, except in the south-western region where the cost of afforestation is higher than the cost of nourishment, and the rest of the regions have a lower cost of afforestation.

Distribution of Carbon Sequestration Costs for Forest Measures in Xinjiang (this figure is generated in ArcGIS10.8 software, http://www.esri.com/software/arcgis).

Discussion

Validation of results

Validation of forest tree heights

In this research, to verify the accuracy of the tree height data, we randomly screened 244 sample plot tree heights with the NNGI tree height data for validation, as shown in Fig. 10, the two tree height products have good consistency with r2 = 0.740, RMSE = 2.130 m, and MAE = 1.630 m. The two tree height products have good consistency with the NNGI tree height data. In conclusion, the above validation results indicate that the NNGI tree height products used in this study have better applicability and accuracy in the Xinjiang region and can meet the needs of this study.

Validation of forest carbon density and carbon stock

In this paper, the carbon densities of 366 forest sample plots (n is the number of sample plots/number) were used to validate the estimated carbon densities of four forest types in Xinjiang in 2019. As can be seen in Fig. 11, the slopes of the regression equations between the sample plot data and the estimation results for the four forest types ranged from 0.83 to 0.99, close to 1, with r2 greater than 0.853, and the ranges of RMSE and MAE were 13.361–18.102 Mg/hm2 and 9.251–15.998 Mg/hm2 respectively. The values of the above validation indicators are in line with the requirements of the MRV (Measuring Reporting and verification) guidelines of the REDD + programme, i.e., when estimating carbon stock using remotely sensed data, the error between the estimated and measured values of carbon density should be controlled to be within 0–20 Mg/hm2 or within 0–20%24. The deviation of the average carbon density of Xinjiang forests in 2019 estimated in this paper5,25 from the previous results ranged from 3.32 to 6.84 Mg/hm2. The deviation of carbon density of different forest types estimated in this paper from the corresponding results of some scholars26 is between 0.93 and 9.25 Mg/hm2. The above analyses indicate that the carbon densities of major forest types in Xinjiang in 2019 estimated in this paper are in good agreement with the estimation results of the previous scholars and have high accuracy.

Some scholars used forest inventory data to estimate the forest carbon stock in Xinjiang in 2020 to be 241.01 Tg C, respectively27; other scholars used remotely sensed tree height data and forest inventory data to estimate the forest carbon stock in Xinjiang in 2019 to be 174.2 Tg C, respectively25 and the deviation from the forest carbon stock in Xinjiang in 2019 estimated in this paper is 7.25–52.81 Tg C, respectively28. Although there are some deviations in the results of different studies due to differences in study years, data sources, methods, and forest areas, the total estimated amount of different carbon stock is relatively close to the total amount of carbon stock, indicating that the estimated forest carbon stock in Xinjiang estimated in this study have a strong level of reliability.

Validation of forest age

Some scholars have estimated the forest age in China based on NDVI data using the cumulative probability density distribution method28. The results show a deviation of 5 years in the average forest age in Xinjiang compared to this study. The age estimation deviation for the four forest types ranges from − 13 to 29 years. Among them, the deviation for different age groups of evergreen coniferous forests is less than 10%. The forest areas with a deviation of less than 10% for deciduous broad-leaved forests and deciduous coniferous forests are 3.9 × 109 m2 and 4.8 × 109 m2, respectively, accounting for 79% and 77% of their total areas. For mixed coniferous and broad-leaved forests, the deviation across different age groups ranges from 19 to 30%, with an area of 8.2 × 108 m2 showing a deviation of less than 25% (Table 11).These comparisons and analyses indicate that the forest age estimates obtained in this study are highly consistent with previous research results. Furthermore, the spatial resolution of forest age derived in this study is higher than that obtained by Dai Ming et al., providing a clear advantage.

Comparative analysis of carbon storage prediction results

Some scholars estimated the carbon storage of Xinjiang forests in 2050 using forest inventory data, obtaining a value of 362.66 Tg C27. Another study, utilizing remote sensing tree height data and forest inventory data, estimated the carbon storage of Xinjiang forests in 2030 and 2060 to be 219.76 Tg C and 334.99 Tg C, respectively6. Compared to this study, the deviations for 2030 and 2060 are 16.05 Tg C and 51.91 Tg C, respectively. Although differences in research years, data sources, methods, and forest areas have led to certain discrepancies among studies28the total estimated carbon storage values are relatively close. This consistency suggests that the carbon storage estimates for Xinjiang forests in this study are highly reliable.

Previous researchers used the IPCC forest carbon sink model to calculate that the carbon density of temperate forests in 2020 was 158.50 Mg/hm2, which differs from the average carbon density of forests in this study by 65.15 Mg/hm2. This difference may be due to the fact that the annual precipitation in the environment where Xinjiang’s forests are located is less than 200 mm29.

This study estimated forest carbon storage under an ideal scenario and constructed an economic benefit analysis framework through a panel data model. However, the estimation of actual forest carbon storage is affected by a variety of complex factors, including but not limited to natural disasters (such as fire, pests and diseases), climate change, human interference, and differences in the effects of different forest management measures. These factors have not been fully considered in the current idealized model, so the research results are uncertain to a certain extent. In order to improve the accuracy of carbon storage estimation and the applicability of the model, future studies can consider constructing a multi-scenario model to simulate carbon storage changes under different environmental and socio-economic conditions25. For example, a fire risk assessment module can be introduced to analyze the impact of different fire frequencies and intensities on forest carbon storage; at the same time, the impact of pests and diseases can also be included in the model to assess its potential threat to forest health and carbon storage. In addition, the long-term impact of climate change on forest growth cycles and carbon absorption capacity, as well as the dynamic impact of different forest management measures (such as afforestation, tending, logging, etc.) on carbon storage, should be the focus of future research. By adding these complex factors to the modeling, we can not only more comprehensively reflect the actual changes in forest carbon stocks, but also provide more scientific and accurate decision-making support for policy makers and forest managers. The construction of multi-scenario models will make carbon stock estimates closer to reality, help identify potential risks and opportunities, thereby optimizing forest management strategies and enhancing the role of forests in addressing climate change13. This study estimated forest carbon storage under an ideal scenario and constructed an economic benefit analysis framework through a panel data model. However, the estimation of actual forest carbon storage is affected by a variety of complex factors, including but not limited to natural disasters (such as fire, pests and diseases), climate change, human interference, and differences in the effects of different forest management measures. These factors have not been fully considered in the current idealized model, so the research results are uncertain to a certain extent. In order to improve the accuracy of carbon storage estimation and the applicability of the model, future studies can consider constructing a multi-scenario model to simulate carbon storage changes under different environmental and socio-economic conditions. For example, a fire risk assessment module can be introduced to analyze the impact of different fire frequencies and intensities on forest carbon storage; at the same time, the impact of pests and diseases can also be included in the model to assess its potential threat to forest health and carbon storage. In addition, the long-term impact of climate change on forest growth cycles and carbon absorption capacity, as well as the dynamic impact of different forest management measures (such as afforestation, tending, logging, etc.) on carbon storage, should be the focus of future research. By adding these complex factors to the modeling, we can not only more comprehensively reflect the actual changes in forest carbon stocks, but also provide more scientific and accurate decision-making support for policy makers and forest managers. The construction of multi-scenario models will make carbon stock estimates closer to reality, help identify potential risks and opportunities, thereby optimizing forest management strategies and enhancing the role of forests in addressing climate change.

Analysis of factors influencing forest carbon storage

ENF are typically distributed in high-altitude areas near the Tianshan and NW, where the climate is relatively cold with significant temperature fluctuations. Due to the small and sharp-shaped leaves of coniferous species, which result in a relatively small leaf surface area, these tree species are more sensitive to temperature changes. DBF and MF exhibit similar levels of response to temperature, with generally moderate significance. In contrast, DNF commonly found near the NW possess strong cold resistance and exhibit the lowest response to temperature variations29.

Due to the arid environment in Xinjiang, all four forest types exhibit a high correlation with precipitation, with the highest correlation observed in DBF. This forest type, dominated by Populus euphratica, is primarily distributed in the Tarim River Basin, where its resilience and high water demand are evident30. ENF and MF show similar correlations with precipitation. In contrast, DNF, which are notably shade-intolerant, exhibit a negative correlation with precipitation, as increased rainfall adversely affects the dominant species, such as larch.

The complex topography of Xinjiang’s arid regions, coupled with the influence of soil types and local microclimates, results in inconsistent forest responses to the SPEI. Moreover, the vegetation in Xinjiang’s arid areas may have adapted to the arid conditions, demonstrating a degree of drought resistance and a stronger capacity to cope with changes in SPEI.

All four forest types show highly significant correlations with vegetation phenology length, ranked as DBF > MF > ENF > DNF. This indicates significant differences in carbon storage among the forest types over the same period. The results of this study offer essential data to guide the selection of forest types with greater carbon sequestration potential.

The sources of LOS data used in this study and their possible uncertainties in arid mountainous areas30. In addition, partial correlation analysis shows statistical correlationsand cannot fully confirm causal relationships. The potential driving mechanism of LOS correlation may be the result of integrated physiological and ecological responses, and its net carbon sink benefit in arid areas may depend on water balance21. The LOS effect varies in regions with different moisture conditions. For example, in the relatively humid northern Xinjiang region, LOS shows a stronger positive correlation with carbon density, while in the extremely arid Turpan Basin, this correlation is weaker or even negative, which is consistent with the inhibitory effect of water limitation on the potential benefits of LOS16.

Feasibility analysis of forest carbon sequestration enhancement measures

This study conducted an economic analysis to compare the regional cost differences between two forest carbon sequestration enhancement measures. By integrating regions suitable for forest tending with spatially estimated harvestable forest areas, a low-cost sequestration approach was identified31. The analysis is based on a panel fixed-effects model, meaning its accuracy is significantly influenced by the quality and quantity of model parameters. In this study, authoritative parameter data were selected, forestry investments were adjusted for inflation rates, and the time-lagged effects of forest measures on carbon sequestration were factored in, ensuring the economic feasibility of the results for different sequestration measures.

This study emphasizes the effects and associated costs of various forest strategies on vegetation carbon sequestration, with a focus on afforestation and forest management. In contrast to previous studies, it presents three key contributions: (1) It employs econometric methods to isolate the actual impacts of different forest measures on vegetation’s carbon sequestration capacity, controlling for unobservable factors. (2) It identifies forest measures better adapted to regional conditions. (3) It analysis investigates the cost discrepancies in vegetation carbon sequestration across forests at different stages of growth. Overall, both afforestation and forest management play a crucial role in boosting vegetation carbon sequestration. However, from the perspective of marginal contribution, forest management demonstrates stronger sequestration potential than afforestation. While afforestation increases both forest area and total carbon storage, forest management focuses on enhancing carbon storage by improving stand structure, particularly in younger and middle-aged forests32.

Previous studies have also observed that compared to China’s extensive afforestation efforts, the United States has achieved greater carbon sequestration by focusing on forest management within smaller newly planted areas. While this comparison highlights the potential benefits of forest management, it is important to recognize the differences in forest resource endowments, policy backgrounds, and socio-economic conditions between China and the United States33,34. In China, afforestation has been a key strategy for increasing forest cover in sparsely vegetated regions, particularly in dry and semi-dry areas of Northwest China, hot and dry valleys of Southwest China, and areas affected by rocky desertification. Continued promotion of afforestation can effectively increase forest cover in these regions, thereby improving carbon sequestration. However, in regions such as C, NC, and NE, where afforestation space is limited and land-use costs are higher, forest management becomes a more suitable approach to enhance productivity, improve forest quality, and increase carbon sequestration within the constraints of limited forestland.

The findings suggest that afforestation should be the main approach to enhance carbon sequestration in NW and SW, while forest management is more suitable for enhancing total carbon sequestration in SR, NC, and NE. Available afforestation land, non-forested areas, and sparse forestlands are primarily located in the dry and semi-dry areas of Northwest China, the hot and dry valleys of Southwest China, and areas affected by rocky desertification. Consequently, continued promotion of afforestation can effectively increase forest cover in these sparsely vegetated regions, thereby improving carbon sequestration. In contrast, C, NC, and NE have limited afforestation space, offering constrained potential for increasing carbon sequestration through afforestation. Additionally, these areas are economically more advanced, characterized by higher land-use costs and greater opportunity costs for forestry development. Therefore, within the constraints of limited forestland, forest management is a more suitable approach to enhance productivity, improve forest quality, and increase carbon sequestration in these regions.

Limitations of the panel fixed-effects model

The panel fixed effects model has played a certain role in analyzing the impact of afforestation and forest tending on enhancing carbon sinks in Xinjiang’s forests, but there are also many limitations that cannot be ignored. From the perspective of model assumptions, the panel fixed effects model assumes that individual effects remain constant over time and do not change with time. However, Xinjiang has a vast territory with a complex and ever—changing ecological environment. In different time periods, climate factors such as temperature, precipitation, and sunlight will change significantly, and these changes will have a significant impact on the formation and accumulation of forest carbon sinks under afforestation and forest tending measures. For example, in recent years, extreme climate events such as intensified droughts and increased frequency of heavy rainfall in some areas of Xinjiang have disrupted the normal growth of forests and their carbon sink functions. The panel fixed effects model has difficulty dynamically capturing the impact of these complex environmental factors that change over time on forest carbon sinks, resulting in possible deviations between the model’s estimated results and the actual situation. In subsequent research, a dynamic carbon—enhancement contribution analysis model should be introduced.

Conclusion

This study focuses on forests in Xinjiang, integrating multi-source remote sensing, chlorophyll fluorescence, and forest inventory data to estimate forest biomass and age from 2010 to 2019 and to construct an age-carbon density model. By excluding disturbances, the study predicts carbon storage and sequestration rates for 2030 and 2060 and explores their responses to temperature, precipitation, SPEI, and vegetation phenology length. Using a panel fixed-effects model, the economic costs of afforestation and forest tending across five regions in Xinjiang were calculated. Recommendations for low-cost tending regions, optimal harvesting timings, and species selection strategies for afforestation were proposed to enhance Xinjiang’s forest carbon sequestration capacity. (1) The average values of biomass, carbon density, and forest age in Xinjiang’s forests in 2019 were 186.76 Mg/hm2, 93.38 Mg/hm2, and 46 years, respectively. Validation using independent sample data and comparison with prior studies demonstrate that the models constructed in this study are highly applicable to the Xinjiang region. Spatially, both forest age and carbon density exhibited strong spatial heterogeneity, with a general low-high-low distribution from south to north and a declining gradient from east to west. (2) By 2030 and 2060, Xinjiang’s forest carbon storage is projected to reach (203.71 ± 2.31) Tg C and (283.08 ± 4.23) Tg C, respectively. Compared to 2019, the carbon sequestration rates during 2019–2030 and 2031–2060 are expected to be 3.67 ± 0.57 Tg C/a and 2.65 ± 0.56 Tg C/a, respectively, showing a decreasing trend across all forest types. However, forest carbon storage is expected to increase significantly by 2030 and 2060, indicating Xinjiang’s forests have substantial carbon sequestration potential. (3) Using CO2 concentration and carbon emission data, combined with estimation and prediction methods, the study reveals that Xinjiang’s forests are projected to absorb approximately 14.6% and 9.5% of CO2 emissions during 2019–2030 and 2031–2060, respectively. From an economic perspective, afforestation is more suitable for most regions, while forest tending is preferable in the northeastern region due to lower costs. Based on the constructed forest age and carbon density models, the growth turning points for four forest types in Xinjiang were identified. Combining these with spatial forest age maps for 2030 and 2050, the study shows that harvestable areas are mainly distributed in high-altitude ridge zones, while efficient carbon-sequestering forest types for afforestation include ENF and DBF. This research provides a comprehensive framework for understanding the dynamics of forest carbon sequestration in Xinjiang and offers data-driven recommendations for enhancing forest carbon sink capacity.

Data availability

The satellite remote sensing datasets generated and/or analysed during this study are listed in Table 1 and are available from the following sources: DEM: https://www.resdc.cn/Default.aspx; NPP: https://ladsweb.modaps.eosdis.nasa.gov; CO2 Emissions: https://db.cger.nies.go.jp/dataset/ODIAC/; Land use: https://zenodo.org/records/4417810; Climatic SPEI Length: https://digital.csic.es/handle/10261/268088; Tree height: https://3decology.org/dataset-software/; Temperature: http://gre.geodata.cn; Precipitation: http://gre.geodata.cn; Data analysed via Google Earth Engine (GEE): https://earthengine.google.com/.The Xinjiang forest inventory data listed under “Forest survey data” in Table 1 are not publicly available. This proprietary dataset, provided by the forestry department, contains confidential and commercially sensitive information and is subject to confidentiality agreements. Researchers with a legitimate need to access this data may contact the corresponding author, Mei Zan, at 107622007010058@xjnu.edu.cn , to request access. Such requests will be evaluated on a case-by-case basis, and access, if granted, will be contingent upon signing appropriate confidentiality agreements and may require further approval from the relevant forestry authorities.

References

Fang, J. Y. et al. Estimation of terrestrial vegetation carbon sinks in China from 1981 to 2000. Chin. Sci. Bull. (Ser D: Earth Sci). 37 (6), 804–812 (2007).

Piao, S. L. et al. Estimation of China’s terrestrial ecosystem carbon sink: Methods, progress, and prospects. Chin. Sci. Bull. : Earth Sci. 52 (6), 1010–1020 (2022).

Piao, S. L., Fang, J. Y. & Huang, Y. Carbon balance of terrestrial ecosystems in China. China Basic. Sci. 12 (2), 20–22 (2010).

Li, H. et al. Dynamic analysis of forest resources in xinjiang: A study based on RS and GIS. Acta Geogr. Sin. 58 (1), 133–138 (2003).

Li, Q. et al. Prediction of carbon storage and carbon sequestration potential of forest arbor in China. Adv. Clim. Change Res. 14 (3), 287–294 (2018).

Liu, Y. C. et al. Estimation of forest biomass carbon sequestration potential based on forest resource inventory data. Acta Ecol. Sin. 39 (11), 4002–4010 (2019).

Li, C. M., Zhang, H. R. & Wang, Z. H. Individual survival models of larch-fir forest based on mixed-effects and survival analysis. J. Beijing Univ. 44 (1), 1–8 (2022).

Zhou, Y., Li, Y., Li, W., Li, F. & Xin, Q. Ecological responses to climate change and human activities in the arid and semi-arid regions of Xinjiang in China. Remote Sens.14 (16), 3911 (2022).

Bi, X. et al. Assessment of spatio-temporal variation and driving mechanism of ecological environment quality in the arid regions of central Asia, Xinjiang. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 18 (13), 7111 (2021).

Liang, Y., Hashimoto, S. & Liu, L. Integrated assessment of land-use/land-cover dynamics on carbon storage services in the loess plateau of China from 1995 to 2050. Ecol. Indic. 120, 106939 (2021).

Jiang, F. et al. Mapping the forest canopy height in Northern China by synergizing ICESat-2 with Sentinel-2 using a stacking algorithm. Remote Sens. 13 (8), 1535 (2021).

Zhang, C. et al. China’s forest biomass carbon sink based on seven inventories from 1973 to 2008. Clim. Change 118 (3), 933–948 (2013).

Dai, L. et al. Assessment of carbon density in natural mountain forest ecosystems at Northwest China. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public. Health. 18(4), 2098 (2021).

Aishan, T., Halik, Ü., Betz, F., Gärtner, P. & Cyffka, B. Modeling height–diameter relationship for Populus euphratica in the Tarim riparian forest ecosystem, Northwest China. J. Res. 27, 889–900 (2016).

Cai, C., Sun, W., Bai, T., Li, Q. & Cao, S. Spatial analysis of Picea schrenkiana var. Tianschanica biomass in the Tianshan mountains, Xinjiang. Forests 16 (1), 3 (2024).

Zhang, C. et al. Mapping forest stand age in China using remotely sensed forest height and observation data. J. Geophys. Res. Biogeosci. 119 (6), 1163–1179 (2014).

Fang, J., Chen, A., Peng, C., Zhao, S. & Ci, L. Changes in forest biomass carbon storage in China between 1949 and 1998. Science 292(5525), 2320–2322 (2001).

Kenett, D. Y., Huang, X., Vodenska, I., Havlin, S. & Stanley, H. E. Partial correlation analysis: Applications for financial markets. Quant. Finance 15(4), 569–578 (2015).

Chicco, D., Warrens, M. J. & Jurman, G. The coefficient of determination R-squared is more informative than SMAPE, MAE, MAPE, MSE, and RMSE in regression analysis evaluation. PeerJ Comput. Sci. 7, e623 (2021).

Zeng, L., Wardlow, B. D., Xiang, D., Hu, S. & Li, D. A review of vegetation phenological metrics extraction using time-series, multispectral satellitedata. Remote Sens. Environ. 237, 111511 (2020).

Gao, L. & Li, H. Improving carbon sequestration capacity of forest vegetation in China: Afforestation or forest management? Forests 14(6), 1077 (2023).

Brüderl, J. & Ludwig, V. Fixed-effects panel regression. Sage Handb. Regres. Anal. Causal Inference 327, 357 (2015).

Torres, A. B., Marchant, R., Lovett, J. C., Smart, J. C. & Tipper, R. Analysis of the carbon sequestration costs of afforestation and reforestation agroforestry practices and the use of cost curves to evaluate their potential for implementation of climate change mitigation. Ecol. Econ. 69 (3), 469–477 (2010).

Gupta, A., Lövbrand, E., Turnhout, E. & Vijge, M. J. In pursuit of carbon accountability: The politics of REDD + measuring, reporting, and verification systems. Curr. Opin. Environ. Sustain. 4 (6), 726–731 (2012).

Chen, Z. Z., Zan, M., Yang, X. F. & Dong, Y. Prediction study on carbon storage of forest vegetation in Xinjiang. Ecol. Environ. J. 32 (2), 226 (2023).

Zheng, S. L. Biomass, carbon storage, and spatial distribution patterns of Tianshan spruce and Siberian larch in the Altai Mountains of Xinjiang. Xinjiang Univ. (2016).

Qiu, Z., Feng, Z., Song, Y., Li, M. & Zhang, P. Carbon sequestration potential of forest vegetation in China from 2003 to 2050: Predicting forest vegetation growth based on climate and the environment. J. Clean. Prod. 252, 119715 (2020).

Dai, M., Zhou, T., Yang, L. L. & Jia, G. S. Estimating the Spatial distribution of forest age in China based on forest inventory and remote sensing data downscaling techniques. Geogr. Res. 30 (1), 172–184 (2011).

Pan, Y. et al. The enduring world forest carbon sink. Nature 631 (8021), 563–569 (2024).

Ameray, A. et al. Forest carbon management: A review of silvicultural practices and management strategies across boreal, temperate, and tropical forests. Curr. Rep. 7, 1–22 (2021).

Bambach, N. et al. Evapotranspiration uncertainty at micrometeorological scales: The impact of the eddy covariance energy imbalance and correction methods. Irrig. Sci. 40 (4), 445–461 (2022).

Huang, H., Wu, D., Fang, L. & Zheng, X. Comparison of multiple machine learning models for estimating the forest growing stock in large-scale forests using multi-source data. Forests 13 (9), 1471 (2022).

Hiltunen, M., Strandman, H. & Kilpeläinen, A. Optimizing forest management for climate impact and economic profitability under alternative initial stand age structures. Biomass Bioenergy 147, 106027 (2021).

Shanin, V., Valkonen, S., Grabarnik, P. & Mäkipää, R. Using forest ecosystem simulation model EFIMOD in planning uneven-aged forest management. Ecol. Manage. 378, 193–205 (2016).

Funding

This research was funded by the National Natural Science Foundation of China (grant number 42261013) and the Natural Science Foundation of Xinjiang Uygur Autonomous Region (grant number 2023D01A49).

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

Conceptualisation, Z. C. and M. Z.; methodology, Z. C.; software, Z. C.; validation, J. K. and Z. C.; formal analysis, M. Z.; investigation, M. Z.; resources, Z. C. and J. K.; data curation, Z. C. and M. Z.; writing—original draft preparation, C. Z. , J.K. and M. Z.; writing—review and editing, M. Z. and Z. C.; visualisation, Z. C, and J. K.; supervision, M. Z.; project administration, M. Z.; funding acquisition, M. Z. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher’s note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutionalaffiliations.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if you modified the licensed material. You do not have permission under this licence to share adapted material derived from this article or parts of it. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Chen, Z., Zan, M. & Kong, J. Assessing the potential for carbon storage enhancement in forests of Xinjiang Uygur autonomous region, China. Sci Rep 15, 29774 (2025). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-14714-5

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-14714-5