Abstract

In response to the problem that the dynamic error caused by the elasticity of the follower rod should be taken into account when designing the cam profile, the form of contact between the cam and the follower rod is chosen in the paper as nonlinear Hertzian elastic contact. In order to obtain the expected movement of the follower rod, the dynamics of the system in the two-parameter planes of \((\omega ,{f_0})\), \((\omega ,{\mu _{{\text{kn}}}})\) and \((\omega ,{\mu _{{\text{cn}}}})\) are calculated to reveal the stable operation interval, the range of failure, and the reasonable parameter combinations. The transmigration processes between the movements n-p and n-(p + 1), n-p and (n + 1)-p as well as n-p and (n + 1)-(p + 1) and some special districts induced by them are discussed. Bifurcation diagrams, phase diagrams, and mapping diagrams are used to fully reveal the correlation between cam rotational speed, pressure, nonlinear contact stiffness, and contact damping and the dynamic performance of the system, while comparing the contact force as well as the depth of intrusion at various stages of the cam input curve. It is shown that the detachment of the cam and the follower rod mainly occurs at the beginning of far dwell phase and when the descent travel turns to the near dwell phase.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Cam mechanisms are widely used in machinery, mechatronic products, and medical industries, such as engine gas distribution mechanisms1, rapier looms2, and precision motion control systems such as quadrupedal bionic robots3, by designing appropriate cam profiles to give arbitrary desired motions to the follower rod. It has been shown that such systems can be effectively modeled as single-degree-of-freedom cam-follower rod systems, where the concentrated parametric single-degree-of-freedom (SDOF) model has been demonstrated to be able to accurately predict the dynamical behavior and residual vibrations of mechanical systems4,5,6. Natali7 studied the dynamic performances of an automotive cam-follower system by means of a SDOF model and verified its correctness. In addition, the contact load between the cam and the follower rod can be assumed to simple harmonic load in SDOF model8. Although multi-degree-of-freedom mechanical models of this system have been continuously investigated, for example, exact expressions for the dynamics equations of the two-degree-of-freedom cam-follower model have been presented in the literature9,10, and three-degree-of-freedom11 and multi-degree-of-freedom dynamics models12,13 have been developed, scholars have concluded that the SDOF model is sufficient for predicting and simulating dynamical phenomena in mechanical systems4,5,6,7.

In the field of cam mechanism dynamics research, a large number of scholars have focused on the mechanism analysis and modeling of the detachment phenomenon. However, it should be pointed out that the rotary motion of the camshaft may induce significant dynamic stresses and vibration responses under high-speed operating conditions. To address this key issue, Alzate14,15 revealed the influence of cam angular velocity variation on the detachment characteristics; Tumer16 derived an analytical expression for the minimum preload force of the reset spring, which integrally takes into account key factors such as the system operating speed, damping characteristics, stiffness parameter, and mass distribution; and Groote17 used a recursive neural network algorithm to predict the follower jump trajectory, and his research results provide a theoretical basis for optimizing the cam system operating environment. The evolution mechanism of contact losses and contact modes has been a key concern18,19,20,21. In recent years, the introduction of the coefficient of recovery and the Hertzian contact theory has led to the identification of contact stiffness and contact damping as key parameters affecting the dynamic characteristics of the system. In order to suppress dynamic impacts and vibrations in cam mechanisms, researchers have proposed an analytical method based on integrated contact mechanics22. Zayas et al.23 developed a flexible multibody dynamics model to characterize the dynamic behavior of the cam-follower system, and their results emphasized the significant effect of contact stiffness parameter selection on the system response. Further, it is revealed a strong nonlinear relationship between cam speed and contact force amplitude by used a finite element method to construct an oil film normal stiffness model in literature24. Based on the above study, a nonlinear Hertzian contact model to equate the actuator-cam contact action adopted in this paper, and the optimal values of contact stiffness and damping are determined through a rigorous parameter sensitivity analysis to ensure the convergence and reliability of the numerical simulation.

The dynamic performance of cam mechanism under contact impact is the key to improve the mechanical performance of cam mechanism25. Shripad26 proposed a novel integrated dynamic model to obtain flexible systems with higher periodicity and chaotic behavior; Yousuf27,28 investigated the nonlinear dynamic response of the follower motion for different cam angular velocities and coefficients of restoration. However, this dynamic behavior also affects the tolerance design29. The dynamic behavior of a cam mechanism is related to the cam profile30,31 and contact conditions32,33. Reducing energy consumption in industrial processes is a challenge to be faced based on the goal of sustainable development34, and studies have shown that time-varying speeds and loads35 affect the operational efficiency of the cam mechanism, and therefore the cam profile displacement curve36,37 has to be reasonably optimized during the design of the cam mechanism.

Based on the purpose of studying dynamics, i.e., tuning and optimizing the parameters of mechanical systems to find the best design solution. Therefore, interesting dynamical phenomena such as periodic movement and chaos38, chattering-impact39, coexistence of multiple steady states40,41 and strange attractors42 in cam mechanisms still deserve to be investigated. Among them, the methods and approaches to study the dynamics are constantly improving, and rising bifurcation43, bare-grazing and real-grazing bifurcation44 are gradually explored and defined by various scholars. Currently, single-parameter bifurcation analysis can no longer fully reveal the correlation between the dynamics and the system parameters, and Peterka45 set a precedent for bifurcation analysis where two parameters are varied simultaneously. Since then, Luo46 has done extensive work on mechanical impact-vibration using two-parameter bifurcation analysis.

Although the dynamics of the cam mechanism has been continuously studied, the deformations resulting from the simultaneous consideration of contact stiffness and contact damping have not been investigated, and the number of separations of the follower rod has not been accurately identified, only the number of periods. In addition, the forms of movement and contact forces corresponding to the ascent travel, far dwell, descent travel, and near dwell phases of the cam input curve are not explicitly calculated. Therefore, taking the cam with flat-bottomed follower system as the research object, based on the two-parameter co-simulation method, the effect of nonlinear Hertzian contact stiffness, contact damping, pressure, and rotational speed on the dynamics of the system is focused. The contact force and intrusion depth at each stage of the cam input curve are calculated to provide a reference for the diagnosis of the system’s working condition and reasonable parameter combination.

The purpose of this paper is to analyze the separation phenomenon between cam and the follower, the layout of the article is mainly divided into three parts: the physical model of the cam with flat-bottomed follower system is introduced and different Poincaré cross sections are established for determining the number of periods and the number of separations for detachment motion in Sect. 2. The effects of rotational speed, preload, contact stiffness and contact damping on the dynamics of the system are simulated, the contact forces corresponding to different phases of the cam input curve are compared and the phases at which the separation phenomenon occurs are analyzed, and the correlation between the depth of intrusion and the dynamics parameters is determined in Sect. 3. Finally, some conclusions are drawn in Sect. 4.

Modeling methodology

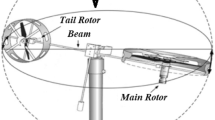

The elastic deformation between the cam and the follower makes the input excitation parameters \({Y_C}\) and \({\dot {Y}_C}\) of the cam unequal to the actual output displacements Y and speeds \(\dot {Y}\) of the follower, as shown in Fig. 1b. Therefore, the dynamic error caused by the elastic deformation of the follower must be taken into account in order to realize a certain desired movement. In addition, when the cam rotates at high speed, if the negative acceleration of the follower is too large, the inertia force caused by it exceeds the spring force and the preload force, which will inevitably result in “jumping” impacts and vibrations of the follower. However, the impacts and vibrations are periodic under certain parameters, and the regularity is determined by the Poincaré mapping method.

Input curves for the cam

Since the cam acts as the prime mover of the mechanism in a cam-follower system, it drives the follower rod to reciprocate along the guide rails on the frame. However, the various dimensional parameters of the cam mechanism are related to the established work objectives, so the law of follower movement must be established according to the work performance requirements. In this paper, the cosine acceleration motion curve is selected as the expected motion law of the follower, and its expression is as follows:

Ascent travel:

Far dwell:

Descent travel:

Near dwell:

Where h is the length of stroke, and \({\Phi _1}\) is the motion angle for ascent travel, \({\Phi _2}\) is far dwell angle, \({\Phi _3}\) is the motion angle for descent travel, \({\Phi _4}\) is the near dwell angle, \(\theta\) is the cam rotation angle displacement, \(\theta ={\omega _1}T\), and \({\omega _1}\) is its rotational angular speed. Allowing \({\Phi _1}={\Phi _3}=\frac{\pi }{3}\), \({\Phi _2}={\Phi _4}=\frac{{2\pi }}{3}\).

According to the operating principle of the cam with flat-bottomed follower mechanism and Fig. 1a, the expressions for the input displacement \({Y_{\text{c}}}\) and input velocity \({Y_{\text{c}}}\) of the cam in the y-direction are as follows:

Where \({R_b}\) is the radius of the cam base circle and N is the number of revolutions of the cam.

Mechanical model

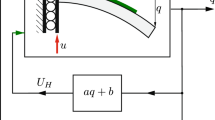

According to the literature4,5,6,7,47, the cam-follower system can be modeled as a single-degree-of-freedom model as shown in Fig. 1b. An x-B0-y coordinate system is established by choosing the contact point B0 of the cam and the follower rod as the origin of the coordinate system, the direction in which the follower rod rises along the guideway as the y-axis. The centralized mass of the follower rod is equated to \({M_1}\), and the reset spring is modeled by the stiffness K1 and damping C1. The output displacement of the follower rod along the y-axis is Y. \({Y_C}\) and \({\dot {Y}_C}\) are the input displacement and speed of the cam in the y-axis, respectively. According to references48,49 and Fig. 1b, the expression for the amount of change in the contact intrusion during the operation of the cam is:

When the cam operates at high speed, it is due to the amount of displacement variation between the cam and the follower rod resulting in the elastic deformation of the two is unavoidable. According to the references47 it is possible to equate the contact form of the two as a nonlinear Hertzian contact mode with a stiffness of Kn and a damping of Cn. The Hunt-Crossley50,51 model is chosen to calculate the force with the following expression:

where n = 1.5 is the nonlinear coefficient.

In order to analyze the dynamics of a single degree of freedom cam mechanism, the following assumptions are made:

-

1.

Both the cam and camshaft are rigid bodies;

-

2.

Only the separation and contact dynamics of the follower in the y-direction are investigated, ignoring the translational movement of the follower in the x-direction and the rotation around the z-axis;

-

3.

Considering the contact between the cam and the follower and the elasticity of the follower itself, the contact load between the two objects is no longer reduced to a simple harmonic load;

-

4.

Torsional vibration effects of the camshaft are not accounted for.

Differential equation

The differential equation for the cam-follower system is given by Newton’s second law as follows:

From Eq. (9), the actual output dynamic response of the follower rod is Y, \(\dot {Y}\), instead of \({Y_C}\), \({\dot {Y}_C}\). Therefore, Y, \(\dot {Y}\) are the expected movements when the cam profile be designed.

First, dimensionless variables and parameters are introduced:

Secondly, from the definition of \({\mu _{\text{k}}}_{{\text{n}}}\) and \({\mu _{{\text{cn}}}}\), the range of their values is \({\mu _{{\text{kn}}}} \in (0.0,\,\,1.0)\), \({\mu _{{\text{cn}}}} \in (0.0,\,\,1.0)\).

Finally, the dimensionless equation of the system is derived:

The dimensionless expression for the contact force is shown below:

where:

Similarly, the dimensionless expression for the pressure is shown below:

Poincaré mapping

Three states of contact between the cam and the follower rod exist. So, a function at the contact surface is constructed:

\({h_1}(x)=0.0\) shows that the follower rod impacts the cam; \({h_1}(x)>0.0\) indicates that the follower rod is in contact with the cam; \({h_1}(x)<0.0\) shows that the follower rod detaches from the cam. Because the impact process is extremely short, the impact and contact states are categorized as contact in the text, and only two states of the follower rod and the cam are identified in the text i.e. detachment, contact. The system exhibits periodic peculiarities under certain parameters, so the notation n-p is used to describe the type of periodic movement pattern, where n denotes the ratio of a vibration period to the period of the external excitation (\(n=1,2,3....\)), and p denotes the number of detachments. Two Poincaré cross-sections are created based on the spatial state of the system, as shown below:

The number of points on cross-section \({\sigma _n}\) is used to determine the number of periods n, and the number of points on cross-section \({\sigma _p}\) is used to count the number of detachments. When the displacement function \({h_1}(x)>0.0\), the follower rod is always in touched with the cam and do not detach, and the system behaves as an n-0 type movement.

The mapping equation for the differential equation of the system is \(Y^{\prime}=\tilde {f}(v,Y)\), where Y is a two-dimensional vector of the system, \(Y \in {{\mathbf{R}}^2}\), \(Y={({\dot {y}_+},\tau )^{\text{T}}}\), \(Y^{\prime}={({\dot {y}^{\prime}_+},\tau ^{\prime})^{\text{T}}}\), \({\dot {y}_+}\) is the velocity of the follower rod after separation, and \(\tau =\omega t+{\tau _0}\), \({\tau _0}\) is the initial phase angle. \(v \in {{\mathbf{R}}^1}\), \(\nu\) is the bifurcation parameter of the system. Thus the perturbation mapping for n-p periodic motion can be expressed as \({Y^{(i+1)}}=\tilde {f}(v,{X^i})\), where, \({Y^{(i+1)}}={Y^*}+\Delta {Y^{(i+1)}}\), \({Y^i}={Y^*}+\Delta {Y^i}\). \({Y^*}\) is an immobile point of \({\sigma _p}\) on the cross-section and the perturbation vector of \({Y^*}\) is \(\Delta {y^i}={(\Delta \dot {y}_{+}^{i},\Delta {\tau ^i})^{\text{T}}}\), \(\Delta {y^{(i+1)}}={(\Delta {\dot {y}_+}^{{(i+1)}},\Delta {\tau ^{(i+1)}})^{\text{T}}}\), then \(\Delta {Y^{(i+1)}}=\tilde {f}(v,{Y^i}) - {Y^*}\mathop =\limits^{{{\text{Def}}}} f(v,\Delta Y)\). Assuming that the dimensionless time t = 0 at the instant after the follower rod separates from the cam, then \({\tau ^{\prime}_0}{\text{=}}{\tau _0}\), and at the instant before the next separation, the dimensionless time \(t = 2n\pi /\omega\). The perturbation equation of the system can be found from Eq. (11) as follows:

where \({\omega _{d1}}=\sqrt {\omega _{1}^{2} - \eta _{1}^{2}}\), \({\eta _1}=\zeta \omega _{1}^{2}\), \({\psi _{11}}\) is the element of the regular modal matrix, \({\tilde {a}_1}\), \({\tilde {b}_1}\) are integration constants, determined by the initial conditions and modal parameters. A1, B1 are the amplitudes of the actuator vibration along the y-axis.

Boundary conditions for the perturbation equations of the system:

Substituting Eq. (18) into Eq. (17) yields:

Where

Substituting Eqs. (18) and (20) into Eq. (17) yields:

From \(\tilde {y}\left( {{t_1}} \right)={y_c}\), construct the function shown below:

This follows from the condition for the existence of an immovable point:

Supposing \({\left( {{\raise0.7ex\hbox{${\partial {g_1}}$} \!\mathord{\left/ {\vphantom {{\partial {g_1}} {\partial \Delta {\chi _1}}}}\right.\kern-0pt}\!\lower0.7ex\hbox{${\partial \Delta {\chi _1}}$}}} \right)_{\left( {0,0,0,0} \right)}} \ne 0\). By the implicit function theorem, it follows from the function g1:

Similarly, by \(\tilde {y}\left( {{t_2}} \right)={y_c}\), \(t_{2} = 2n\pi /\omega\). Constructing the function \({g_2}\left( {\Delta {{\tilde {\dot {y}}}_+},\Delta \tau ,\Delta {\chi _2}} \right)=\tilde {x}\left( {{t_2}} \right) - {y_c}\).

Substituting Eqs. (24) and (25) into Eq. (21) yields the Poincaré mapping for periodic motion:

The linearized matrix of the above mapping at the immovable point:

The system exhibits n-1 periodic motions in certain parameter intervals, and the mapping immovable point for n-1 motions is \(Y_{0}^{*}={({\dot {y}_{0+}},{\tau ^{\prime}_0})^{\text{T}}}\). The perturbation mapping is \(\Delta Y_{0}^{{(i+1)}}=\tilde {f}(v,Y_{0}^{i}) - Y_{0}^{*}\mathop =\limits^{{{\text{Def}}}} f(v,\Delta {Y_0})\), if \(\Delta {Y_0}=0.0\), then\(f(v,0)=0.0\). In the paper, the eigenvalues \({\lambda _i}\) of the Jacobi matrix of the system are applied to determine the stability of the periodic motion n-p52, i denotes the number of eigenvalues.

Parameter coupling mechanism

The variation of a single parameter can no longer meet the requirements of modern mechanical dynamics and mechanical optimization design, so it is necessary to discover the dynamics of the mechanical system under the action of multi-parameter coupling. The mechanism of multi-parameter coupling action is divided into three steps: firstly, the key non-smooth mechanical factors that cause discontinuities and strong nonlinearities in the system properties are taken as the parameter coupling objects and form the multi-parameter plane. Secondly, since the depth of revelation of the correlation between the parameters and the system dynamics depends largely on the density of the discrete points in its maximum range, the higher the degree of the parameter planes being discretized, the higher the accuracy of the solution of the equations. At the same time, in order to avoid the numerical dispersion of the kinetic equations at the discontinuous points and to meet the computational accuracy and improve the computational speed, a smaller integration step size should be chosen. In the paper, the key factors are discretized into a 400*400 grid, and the fourth-order Runge-Kutta method with variable step size is used to solve the points on Poincaré sections \({\sigma _n}\) and \({\sigma _p}\). The combination of n-p, i.e., the type of the motion pattern, can be known from the number of points. Finally, the same motion types n-p are identified in the same text and marked with the same color.

Influence of dynamical parameters on the movement of the follower

“Modeling Methodology” shows that there are impacts and vibrations between the cam and the follower, which can result in transient disengagement, changes in the output response, an increase in the dynamic load, as well as an increase wear and noise, and the reduce of the service life, among other things. This phenomenon is closely related to the dynamic parameters of the cam-follower system, which must be considered in the design of the cam mechanism. According to Eq. (11), it is known that the system has several nonlinear dynamic parameters such as Hertzian contact stiffness, contact damping, and rotational speed of the cam. Therefore, it is necessary to study the effects of these dynamics parameters on the cam mechanism.

The number of points on cross-section \({\sigma _n}\) and cross-section \({\sigma _p}\) in the text is solved by the variable-step fourth-order Runge-Kutta method, and the type of movement pattern n-p is known from the number of points. The numerical calculations are performed to avoid numerical dispersion of the cam input function at discontinuous points, and to ensure that the dynamic response of the system reaches a stabilized solution, it is necessary to choose a small integration step and start reading the results after 500 periods of system rotation. Meanwhile, in order to indicate the severity of the detachment, the duty cycle value DC of the detachment is calculated. The larger the duty cycle value is, the longer the detachment time between the two is, and when DC=1.0, it indicates that the follower and the cam are in a completely detachment state.

Influence of pressure on the movement of the follower rod

The cam-follower system shown in Fig. 2 moves in the y-direction under the combined effect of pressure and contact force. Therefore, it is worthwhile to investigate the effect of pressure on the system characteristics. After several numerical simulations, it is found that the rotational speed \(\omega\) of the cam is the main nonlinear factor leading to the higher order discontinuities of the system. Based on a multiparameter co-simulation method, where the main idea of the method is that the two dynamical parameters are varied simultaneously in a certain step size. The dynamics of the system is calculated on the \((\omega ,{f_0})\)-plane, where the values of the parameters are: \({\mu _{\text{k}}}_{{\text{n}}}=0.8\), \({\mu _{\text{c}}}_{{\text{n}}}=0.8\), \(\zeta =0.2\) and \({r_b}=5.0\).The two bifurcation parameters change simultaneously in the direction of the decreasing starting point \((\omega ,{f_0}){\text{=(6}}{\text{.0,5}}{\text{.0)}}\). \({X_0}={({y_{0+}},{\dot {y}_{0+}},{\tau _0})^{\text{T}}}={(0.0,0.0,0.0)^{\text{T}}}\) is chosen as the initial value and \(\omega \in [0.02,6.0] \cap {f_0} \in [0.01,5.0]\) as the calculation interval, and the calculation results are shown in Fig. 2. One type of movement corresponding to each point on the \((\omega ,{f_0})\)-plane, and then the same type of movement n-p is identified in the same text and marked with the same color, where chattering-impact movements are indicated by the symbol n-\(\tilde {p}\)(\(n \geqslant 1 \cap p \geqslant 7\)).

Figure 2 illustrates the dynamic response characteristics of the system on the parameter plane of \((\omega ,{f_0})\), including the type of motion pattern, distribution law, bifurcation behavior, and the evolutionary characteristics of the impact-detachment duty cycle. Among them, Fig. 2c–e are localized enlarged plots of Fig. 2a, which are used to present the key dynamics details in detail. In the low-speed interval of \(\omega <1.0\), the system mainly exhibits 1-p fundamental periodic motions as well as chattering motions 1-\(\tilde {p}\). As the cam rotation speed \(\omega\) decreases, the 1-p motion is embedded in the 1-(p + 1) motion interval by evolving through a grazing bifurcation, which leads to an increase in the number of its separations. However, since the contact between the cam and the follower is a nonlinear Hertzian elastic contact, the 1-(p + 1) motion does not continue to undergo a grazing bifurcation as \(\omega\) is further reduced, but rather a saddle-node bifurcation that leads to a decrease in the number of separations, and ultimately embedded in a 1 − 0 motion window, i.e., a continuous contact motion without detachments. In the very low-speed interval, the system exhibits a 1 − 0 motion mode with a duty cycle value of DC=0.0. The dynamical behavior of the system undergoes a significant evolution as the rotational speed \(\omega\) increases: the 1-p motion is gradually embedded into the parameter window of the subharmonic periodic motion (\(n \geqslant 2\)) through the period-doubling bifurcation and the period-adding bifurcation, which is accompanied by a monotonous incremental tendency of the duty cycle DC. The quantitative analysis in Fig. 2b shows that the rotational speed is strongly positively correlated with the separation probability. When \(\omega >5.0\), the system enters a high-frequency excitation state, resulting in a duty cycle DC asymptotically approaching 1.0.

In addition to this, the system exhibits different dynamics along the direction of pressure \({f_0}\) variation. The non-detachment motion 1 − 0 is embedded in the window of chattering-impact motion 1-\(\tilde {p}\)(\(p \geqslant 7\)) along the direction of \({f_0}\) increase, and despite the high number of detachments of this motion, the separation height is small, and the parameter domain corresponding to this type of motion has a small value of DC as shown by the distribution of duty cycle values in Fig. 2b. The higher the preload, the smaller the duty cycle value, indicating that the mechanism is less prone to detach. Meanwhile, the duty cycle value increases with velocity, indicating that the velocity is an important reason for the detachment to occur.

Distribution pattern and bifurcation characteristics of the separation motion of the follower from the cam in the \((\omega ,{f_0})\)-plane, where the two parameters, i.e., cam rotation speed and preload force are varied simultaneously. (a) global distribution of n-p periodic movements. (b) duty cycle distribution. (c) district of distribution for fundamental periodic movements 1-p in the low-speed district. (d) translational domains of periodic movements 1–1 vs. 2–2. (e) translational domains of neighboring periodic movements n-p vs. (n + 1)-(p + 1).

Figure 2c–e show the local details of Fig. 2a, and it is revealed that the transfer process and bifurcation law of the adjacent fundamental periodic movements 1-p and 1-(p + 1) in Fig. 2c. It can be seen from the figure with the rotational speed \(\omega\) decreases, the 1-p motion can occur once the grazing bifurcation embedded in the window of 1-(p + 1) motion can also be embedded in the window of 1-(p + 1) motion by a number of bifurcation changes. Priority is given to analyze the former transmigration mechanism, the force \({F_y}\) on the follower can be obtained in the y-direction when the follower impacts and detaches from the cam according to Eq. 11. The expression of \({F_y}\) is as follows:

In the above equation, \({y_c}\) represents the displacement of the follower rod when it detaches from the cam, and \({\dot {y}_ - }\) represents the instantaneous speed before detachment. If the force \({F_y}\) in the y-direction at the instant of detachment between the follower rod and the cam is directed downward, there is no more detachment but remain in contact, and the fundamental periodic movements 1-p keep the type unchanged; If the force \({F_y}\) at the instant of detachment is in the same direction as the speed \({\dot {y}_ - }\), the 1-p movement will continuously occur many times grazing bifurcation so that the number of detachments is gradually increased until the direction of the combined external force \({F_y}\) is changed and the speed of the last detachment is reduced to zero, then the detachment movement is over; If the \({F_y}=0.0\) at the instant of detachment, the follower rod remains in contact with the cam, but at this point the contact force \({P_{\text{n}}}\) begins to increase, and the system undergoes a grazing bifurcation with a 1-(p + 1) movement, with which the follower rod begins to be pushed upward. Under the action of the contact force \({P_{\text{n}}}\), the 1-p movement no longer continuously traverses its grazing bifurcation line \({{\text{G}}_{1 - p}}\), and consequently the number of detachments does not continue to increase, but there is a 1-(p-1) movement induced by a saddle-node bifurcation, as shown in Fig. 2c. The transmigration paths are as follows:

In addition to these types of transfer scenarios, there are other paths for the transfer of neighboring fundamental periodic motions 1-p and 1-(p + 1) motions, such as the transfer of the fundamental periodic motions 1–2 and 1–3 in Fig. 2c, which has the following transfer path:

\({{\text{A}}_{{\text{4-}}\tilde {p}}}\) in Eq. 19 denotes the period adding bifurcation of the 4-\(\tilde {p}\) movement. The above analysis shows that the transitions of adjacent fundamental periodic movements 1-p and 1-(p + 1) are complex and variable. The subharmonic periodic movements (\(n \geqslant 2\)) are centrally distributed between the neighboring movements, and the area shaped as a tongue is called the lingual domain in the paper. The movements such as 2n-2p, 2n-(2p-1), 2n-(2p + 1), 2n + 1-(2p + 1), 2n + 2-(2p + 1), and so on, appear in the lingual domain.

There are the distribution laws and transfer domains appearing in transition of the n-p and (n + 1)-(p + 1) motions, which are similar to the fundamental periodic motion 1-p and 1-(p + 1) transitions with two types of transfer paths in Fig. 2d,e. Combining Fig. 2d,e, it can be concluded that the lingual domain formed during the transmigration of the n-p and (n + 1)-(p + 1) motions is bounded by the period-doubling bifurcation line \({\text{P}}{{\text{D}}_{n{\text{-}}p}}\) of the n-p motion and the grazing bifurcation line \({{\text{G}}_{(n{\text{+1}}){\text{-(p+1)}}}}\) of the (n + 1)-(p + 1) motion.

In order to analyze the effect of pressure on the contact relationship between the cam and the follower, the intrusion depths corresponding to different pressures at different cam rotation speeds are calculated separately, and the results are shown in Fig. 3. It shows that the intrusion depth \(\varepsilon\)(\(\varepsilon >0.0\)) increases with increasing \({f_0}\) and the detachment height \(\varepsilon\)(\(\varepsilon <0.0\)) has the opposite trend, this result is highly consistent with the results of the literature53,54. In addition, it can be seen that the contact state between the cam and the follower gradually changes from continuous contact (\(\varepsilon >0.0\)) to detachment (\(\varepsilon <0.0\)) with the increase of cam rotation speed. If the displacement of the cam and the follower is \(\varepsilon <0.0\) in the whole cam rotation circle, that is, the cam and the follower are in the detachment state, and the cam mechanism will not work, obviously, this phenomenon does not appear in the simulation results.

The above analysis shows that the depth of intrusion increases with increasing pressure and rotational speed. Excessive depth of intrusion firstly accelerates wear between the two components and in applications where precise control is required, the follower rod may not be able to achieve the required accuracy. Secondly, an increase in the depth of intrusion, the contact force \({P_{\text{n}}}\) increases according to Eq. (12), then a larger power is required to drive the cam rotation, in the need for rapid response occasions, too large a depth of intrusion will lead to the cam mechanism response becomes sluggish, affecting the overall performance of the mechanical system. Finally, an excessive depth of intrusion can lead to stress concentrations and the risk of fracture or damage in certain areas of the cam and the follower rod. Therefore, it is necessary to choose a reasonable depth of intrusion when designing cam mechanisms to ensure the efficient and healthy operation of the mechanical system.

Influence of nonlinear Hertzian contact stiffness on the movement of the follower rod

It is shown that the cam-follower system operates smoothly and safely under a combination of pressure and contact forces in the previous section, and the influence of the pressure on the dynamic properties of the system has already been described. However, the influence of contact force still needs to be explored, which is related to contact stiffness and contact damping, two variables whose values reflect the ability of the two objects to resist deformation at the point of contact and the rate of energy dissipation. It can be seen that the contact stiffness Kn and contact damping Cn are only related to the stiffness ratio \({\mu _{{\text{kn}}}}\) and damping ratio \({\mu _{{\text{cn}}}}\) from the Eq. (10). Therefore, if the effects of contact stiffness and contact damping on the dynamic response are explored, only the effects of \({\mu _{{\text{kn}}}}\), \({\mu _{{\text{cn}}}}\) on them are analyzed. Priority is given in the paper to the analysis of the influence of \({\mu _{{\text{kn}}}}\) on the dynamical properties of the system.

It is shown that increased pre-pressure can lead to excessive depth of intrusion and the hazards of excessive depth of intrusion are described in the above section. Therefore, the values of the other parameters and the initial values of the state quantities in the simulation calculations are kept unchanged, taking the pressure \({f_0}=0.5\), \((\omega ,{\mu _{{\text{kn}}}})=(6.0,{\kern 1pt} \,0.95)\) as the starting point of the calculation, and \(\omega \in [0.02,6.0] \cap {\mu _{{\text{kn}}}} \in [0.7,0.95]\) as the simulation intervals. Based on the previous simulation method, the nonlinear dynamic response results of the system in the \((\omega ,{\mu _{{\text{kn}}}})\)-plane are shown in Fig. 4. From the figure, it can be seen that the non-detachment movement n-0 is primarily distributed in the interval of very small speed or the interval of smaller stiffness ratio, which corresponds to a duty cycle value of zero, at this time, it is good contact between the cam and the follower, and the detachment phenomenon does not occur. When \({\mu _{{\text{kn}}}}<0.8\), firstly, the subharmonic periodic non-detachment movements n-0(\(n \geqslant 2\)) is distributed along the direction of increasing speed with small duty cycle values, the n-0 movements are embedded in the rgion of n-1 movements along the direction of increasing \({\mu _{{\text{kn}}}}\) through their grazing bifurcations \({{\text{G}}_{n - 0}}\); Secondly, the n-1 movements are successively embedded in the regions of the n-2, 2n-2, etc. movements through the period-doubling and grazing bifurcation, as shown in Fig. 4b,c. When \({\mu _{{\text{kn}}}}>0.8\), the distribution district and distribution law of the periodic movements n-p change greatly. First, the subharmonic periodic non-detachment movement n-0(\(n \geqslant 2\)) in the high-speed interval disappears, and the duty cycle value increases rapidly with increasing \({\mu _{{\text{kn}}}}\); Second, the periodic movements 1–1, 2 − 1, 3 − 1 and other n-1movements are no longer sequentially arranged, but are embedded in the other movement windows through the grazing bifurcation and the periodic-doubling bifurcation; Finally, the number of detachments of the n-p movement group gradually increases with increasing \({\mu _{{\text{kn}}}}\), which exacerbates the degree of damage between the follower and the cam.

The above simulation results show that the larger the contact stiffness, the more complex the dynamics, and this conclusion is in line with the actual mechanical properties and is consistent with the results in the literature7,14,15,22,48.

Distribution pattern and bifurcation characteristics of the separation motion of the follower from the cam in the \((\omega ,{\mu _{{\text{kn}}}})\)-plane, where the two parameters, i.e., cam rotation speed and contact stiffness ratio are varied simultaneously. (a) global distribution of n-p periodic movements. (b) duty cycle distribution. (c) the group of periodic movements 1-p distribution district. (d) translational process of periodic movements 1–1 vs. 2 − 1. (e) translational.

process of adjacent periodic movements 2 − 1 vs. 3 − 1.

Figure 4c–e show the localized detail maps of Fig. 4a, and it can be observed the transmigration process of the adjacent periodic movements 1–2 and 1–3 from Fig. 4c, which can be classified into two categories. One is that the 1–2 motion and the 1–3 motion can be transited by a single grazing bifurcation or saddle-node bifurcation, and can be seen from Fig. 5a,a1, a discontinuity, i.e., jumping phenomenon, occurs when the 1–2 motion undergoes a grazing bifurcation. Since this type of transmigration process is reversible and discontinuous, there is no lingual domain. Another is the emergence of aggregated regions of subharmonic periodic motions caused by different bifurcations between the 1–2 motion and the 1–3 motion, as shown in Figs. 4c and 5b,b1. Calculating the eigenvalues at \(\omega ={\omega _{c1}}=1.1620\) in Fig. 5b1 shows that \({\lambda _{1,2}}({\omega _{c1}})= - 0.354351 \pm 0.263715{\text{i}}\), which satisfies the condition of period-doubling bifurcation, and as w increases, the eigenvalues of the Jacobi matrix at \(\omega ={\omega _{c2}}=1.4301\) are calculated to be \({\lambda _1}({\omega _{c2}})=0.263516\), \({\lambda _2}({\omega _{c2}})=0.374650\), and at this point the system becomes chaotic, and the numerical calculations are in agreement with the results of the simulation. Comparison of the two transit paths of movements 1–2 and 1–3 shows that the irreversibility of the transit caused by the period-doubling bifurcation and the grazing bifurcation is the main reason for the emergence of the lingual domains.

Figure 4d,e show the transfer process between different periodic movements n-1 and (n + 1)-1, and the transfer between 1–1 and 2 − 1 movements is taken as an example to analyze the transfer mechanism. The 1–1 movement continuously crosses the period-doubling bifurcation lines \({\text{P}}{{\text{D}}_{1 - 1}}\), \({\text{P}}{{\text{D}}_{2{\text{-}}2}}\) and \({\text{P}}{{\text{D}}_{4{\text{-}}4}}\) and transitions into the region of long-period movements. At this time, the 3 − 2 movement is detached from region of the long-period movement through the bare-grazing bifurcation, and the bare-grazing bifurcation line \({{\text{G}}^{\text{b}}}_{{3{\text{-}}2}}\) is extremely unstable, which makes the 3 − 2 movement embedded into the chaos rapidly with the increase of \(\omega\), as shown in Figs. 4d, 5c,c1. The phase diagram of the transition between 1–1 movement and 2 − 1 movement is shown in Fig. 6, where the blue dots indicate the immobilization points of periodic attractor, and the number of periods n is known from the number of dots, and the red dots indicate the phase points of the detachment, and the number of detachments p and the specific phases of the detachments can be known from the number of dots and their positions. When \(\omega {\text{=}}3.208583\), the system occurs hopf bifurcation from the period n = 1 embedded in the quasi-periodic movement, with \(\omega\) continues to increase, from the quasi-periodic movement out of the 2 − 1 movement, to which the transmigration of movement 1–1 and 2 − 1 is completed. The transmigration process of the periodic movement 2 − 1 vs. 3 − 1 is shown in Figs. 4e and 5d,d1, which is similar to the transmigration process of the 1–1 vs. 2 − 1 movement and will not be analyzed in the text.

Bifurcation diagrams of number of periods and number of detachments for the variation of a single parameter \(\omega\) when \({\mu _{{\text{kn}}}}\) takes different values. (a, a1) \({\mu _{{\text{kn}}}}{\text{=}}0.94\). (b, b1) \({\mu _{{\text{kn}}}}{\text{=}}0.90\). (c, c1) \({\mu _{{\text{kn}}}}{\text{=}}0.91\). (d, d1) \({\mu _{{\text{kn}}}}{\text{=}}0.922\).

Phase diagram and Poincaré mapping of periodic movement transitions and quasi-periodic movement under \({\mu _{{\text{kn}}}}{\text{=}}0.91\). (a) 3 − 2 movement at \(\omega {\text{=2}}{\text{.71}}\). (b) chaos at \(\omega {\text{=}}2.709\). (c) Poincaré mapping of chaos at \(\omega {\text{=}}2.709\). (d) 4–4 movement at \(\omega {\text{=2}}{\text{.83}}\). (e) 2–2 movement at \(\omega {\text{=}}3.0\). (f) 1–1 movement at \(\omega {\text{=}}3.15\). (g) quasi-periodic movement at \(\omega {\text{=}}3.208583\). (h) Poincaré mapping of quasi-periodic movement at \(\omega {\text{=}}3.208583\).

Influence of nonlinear Hertzian contact damping on the movement of the follower rod

The influence of the contact stiffness on the movement of the follower rod and the dynamics of the system in the \((\omega ,{\mu _{{\text{kn}}}})\)-plane have been analyzed in detail, but from Eq. (8), it can be seen that the contact damping is also an important factor that cannot be ignored during the operation of the cam mechanism, which can slow down the movement of the object and accelerate the vibration energy dissipation. Therefore, it is demanding to study the influence of contact damping on the dynamic characteristics of the system.

The the values of the dimensionless parameters, the initial values of the state quantities, the starting point of the calculations, and the simulation intervals are kept the same as in the previous section. When the two parameters of cam rotation speed \(\omega\) and damping coefficient \({\mu _{{\text{cn}}}}\) change at the same time, the nonlinear dynamic response in the \((\omega ,{\mu _{{\text{cn}}}})\)-plane results are shown in Fig. 7. It can be seen that the larger \({\mu _{{\text{cn}}}}\) is, the more significant the nonsmooth characteristics of the system is, the richer the pattern types of n-p motions is, and the mechanism of transmigration between different motions is more complex and variable from Fig. 7, as shown in the following. First, the number of detachments p and the duty cycle value DC of the n-p movement increase with \({\mu _{{\text{cn}}}}\). The larger the duty cycle value DC, the longer the duration of the detachment event occurs, and the event is mainly concentrated in the interval of high speed and \({\mu _{{\text{cn}}}}>0.9\). Second, the parameter domain of the non-detachment movement n-0 gradually shrinks with \({\mu _{{\text{cn}}}}\) increasing, and the parameter domain of the n-1 movement expands; Finally, although the number of detachments for the 1-p movement in the low-speed region is greater than that for the n-p(\(n \geqslant 2\)) movement in high-speed region, the duty cycle value DC is lower than those for the n-p movement, indicating a weaker vibration in the low-speed interval than in the high-speed district.

In addition, comparing Fig. 7, it is found that the pattern types, distribution laws, and bifurcation characteristics of the n-p movement of the system in the \((\omega ,{\mu _{{\text{cn}}}})\)-plane and the \((\omega ,{\mu _{{\text{kn}}}})\)-plane are consistent, which are manifested in the fact that the larger the contact stiffness and contact damping are, the more complex is the dynamic response of the system and the longer is the duration of the detachment event.

Distribution pattern and bifurcation characteristics of the separation motion in the \((\omega ,{\mu _{{\text{cn}}}})\)-plane, where the two parameters, i.e., cam rotation speed and contact damping ratio are varied simultaneously. (a) global distribution of periodic movements n-p. (b) duty cycle distribution. (c) fundamental periodic movement 1-p distribution district. (d) translational processes of neighboring periodic movements n-p and (n + 1)-(p + 1) (n = p). (e) translational process of periodic movements 2 − 1 vs. 3–3.

Figure 7c–e show the localized detail maps of Fig. 7a, which reveal the distribution law and bifurcation characteristics of n-p, n-(p + 1), and (n + 1)-(p + 1) motions in the \((\omega ,{\mu _{{\text{cn}}}})\)-plane as well as the special parameter domains, which has a similarity with the transit law of the n-p motions in the parameter \((\omega ,{\mu _{kn}})\)-plane, and thus will not be described again.

Characterization of the detachment phenomenon

The dynamics of the cam mechanism on the two-parameter planes \((\omega ,{f_0})\), \((\omega ,{\mu _{{\text{kn}}}})\) and \((\omega ,{\mu _{{\text{cn}}}})\) have been analyzed, and the results show that the increase of the preload force significantly reduces the duty cycle of separation, which effectively suppresses the separation phenomenon of the system; whereas the increase of the contact damping and the contact stiffness exacerbates the non-smooth characteristics of the system and prolongs the duration of the separation. However, existing studies have not yet elucidated the dynamic correlation between the separation motion and the cam input curve, nor have they revealed the evolution of the contact force between the cam and the follower rod. In this study, the intrusion depth is introduced as a key state variable to accurately characterize the contact/separation state of the cam and the follower rod, and based on this, the dynamic response of the contact force with the cam input curve is quantitatively analyzed.

Depth of intrusion

The height of separation and the depth of intrusion between the cam and the follower rod are very important for the proper functioning of the cam mechanism, and the disadvantages and hazards of excessive depth of intrusion are shown in the Section “Influence of pressure on the movement of the follower”. Therefore, taking \({f_0}{\text{=}}2.5\), the displacement change \(\varepsilon\) of the cam and the follower corresponding to each \({\mu _{{\text{cn}}}}\) and \({\mu _{{\text{kn}}}}\) at different rotational speeds are calculated, and the results are shown in Fig. 8, where different colors are used to indicate each \(\varepsilon\). It can be seen that increasing the contact stiffness and contact damping both help to reduce the intrusion depth (\(\varepsilon >0.0\)), correspondingly, and the detachment height increases with increasing \({\mu _{{\text{kn}}}}\) and \({\mu _{{\text{cn}}}}\). This is because the contact stiffness affects the deformation of the object, which decreases as the contact stiffness increases; and the greater the contact damping, the greater the inertial forces in the system, and the slower the response time when subjected to vibration or external forces. However, under the same conditions, it is easier to reduce the depth of intrusion by increasing \({\mu _{{\text{kn}}}}\) relative to increasing \({\mu _{{\text{cn}}}}\).

Comparing Fig. 8a–c, it can be seen that the contact state between the cam and the follower is gradually transformed from the state of continuous contact (\(\varepsilon >0.0\)) to the state of detachment (\(\varepsilon <0.0\)) with the increase of the speed \(\omega\), in addition to which the detachment height also increases, which is in line with the conclusions of the previous section, and further illustrates that the rotational speed is an important factor in inducing the phenomena of impact and detachment. It is expected that the cam and the follower to remain in contact at all times rather than separating, but as mentioned earlier, the hazards of an excessive depth of intrusion are greater than the hazards of an excessive height of separation. Excessive intrusion depth will seriously affect the dynamic performance of the mechanical system, in the cam mechanism design as long as to ensure that the cam and the follower rod do not be in a state of complete separation in a rotational, i.e., \(\varepsilon <0.0\).

Contact forces between the cam and the follower

From Fig. 1b and Eq. 8, it can be seen that when the follower detaches from the cam, then the contact force \({P_{\text{n}}}{\text{=}}0.0\); when the cam impacts the follower, then \({P_{\text{n}}}\) increases from zero. And it can be seen that the \({P_{\text{n}}}\) is a quantity that is related to the input function of the cam from Eq. 8. If one wants to explore the changing states of contact, impact, and detachment between the cam and the follower, as well as the change in the contact force \({P_{\text{n}}}\) during the ascent travel, far dwell, descent travel and near dwell phases, it is necessary to compute the contact force \({P_{\text{n}}}\) at different speeds and plot the correspondence with the cam input function \({y_c}\).

In order to deeply analyze the dynamic characteristic change law of cam-follower system and accurately determine its contact state evolution process, the time-varying characteristics of contact force \({P_{\text{n}}}\) and input function \({y_c}\) are calculated corresponding to different motion speeds under the working condition of pre-pressure \({f_0}{\text{=}}0.5\) in this paper. By synergistically visualizing the response curves of the time-domain synchronized contact force \({P_{\text{n}}}(t)\) and the input displacement \({y_c}(t)\), a comparative diagram of the coupled dynamics characteristics is constructed as shown in Fig. 9. In this figure, the red solid line is used to characterize the dynamic response curve of the contact force \({P_{\text{n}}}\), whose magnitude corresponds to the left-hand axis, while the blue solid line represents the time profile of the input displacement \({y_c}\), whose magnitude corresponds to the right-hand axis. The horizontal coordinates are calibrated with a uniform dimensionless time parameter t. The horizontal coordinates are calibrated with a uniform dimensionless time parameter t. In order to accurately identify the critical point of the contact state transition, the ● symbol is used to mark the onset of the collision, and the * symbol is used to mark the separation critical point. In Fig. 9, \({P_{\text{n}}}{\text{=}}0.0\) means that the cam and the follower rod are in a detachment state. From the figure, it can be seen that the detachment occurs in the beginning of far dwell stage and in the stage of descent travel to ascent travel, but the point of impact occurs in which stage of the cam input curve is not fixed. The time of impact is very short, as described in the Section “Poincaré Mapping”. Therefore, only two states, contact and detachment, are recognized in the text.

It can be observed that the follower is continuously pushed upward during the ascent travel phase, and the contact force \({P_{\text{n}}}\) gradually increases from zero, reaching a maximum value at the end of the ascent travel, and the \({P_{\text{n}}}\) appears to be minimum when the follower detaches from the cam from Fig. 9.

In addition to the conclusions drawn from the above analysis, the contact between the cam and the follower is equated to a nonlinear Hertzian contact mode with contact stiffness and contact damping, and it can be seen from Fig. 9 that, due to the presence of damping, hysteresis occurs, i.e., the response time of \({P_{\text{n}}}\) is lagging behind the input time of \({y_c}\).

Conclusion

In the paper, the nonlinear Hertzian contact between the cam and the follower rod is considered to solve the dynamic error of the cam mechanism due to the elasticity of the follower rod, and the correlation between the detachment height and the intrusion depth with the dynamic parameters is analyzed, while the contact force at each stage of the cam input curve are compared. Based on the multi-parameter coordinated change simulation method, the bifurcation characteristics and distribution laws of the detachment movement and non-detachment movement on the two-parameter planes of \((\omega ,{f_0})\), \((\omega ,{\mu _{{\text{kn}}}})\) as well as \((\omega ,{\mu _{{\text{cn}}}})\) are analyzed in detail. The displacement difference, \(\varepsilon =y - {y_c}\), is applied to judge the reasonableness of different parameter values. It is concluded that the cam rotation speed is an important factor leading to a system with non-smooth characteristics, and the non-detachment movement 1 − 0 is distributed in the region of low-speed. The depth of intrusion is related to cam rotation speed, pressure, nonlinear contact stiffness, and contact damping. Decreasing the pressure and cam rotation speed, increasing the contact stiffness and contact damping can reduce the intrusion depth, but increasing the contact stiffness is more effective than increasing the contact damping. The phenomenon of detachment between the cam and the follower occurs mainly in the beginning of far dwell phase and the stage of descent travel to near dwell. The impact time between the two is very short and the impact point is not fixed. The contact force gradually increases in the ascent trip phase until it reaches the maximum value at the end of the ascent travel phase, and disappears when the two are detached, i.e., \({P_{\text{n}}}=0.0\). Periodic motions n-p with (n + 1)-p, n-p with n-(p + 1) can be transduced through a single bifurcation or through multiple bifurcation forms and induced lingual domains.

Data availability

The datasets used and/or analysed during the current study available from the corresponding author on reasonable request.

References

Hu, B., Zhou, C. J., Wang, H. B. & Yin, L. R. Prediction and validation of dynamic characteristics of a valve train system with flexible components and gyroscopic effect. Mech. Mach. Theory. 157, 104222 (2021).

Qiu, H., Huang, P., Zhou, Y. & Zhang, H. Flexible modeling and dynamics simulation of four-bar beating-up system with clearance. J. Ind. Textil. 53, 15280837231184640 (2023).

Ohno, M. & Takeda, Y. Design of target trajectories for the detection of joint clearances in parallel robot based on the actuation torque measurement. Mech. Mach. Theory. 155, 104081 (2021).

Gianluca, G. & Domenico, M. On the direct control of follower vibrations in cam–follower mechanisms. Mech. Mach. Theory. 45 (1), 23–35 (2010).

Hardy, S. & M-Daragheh, M. A parametric study using a single cam-follower rod system dynamic model. Proc. Instn Mech. Eng. D-J Aut. 205 (4), 273–277 (1991).

Felszeghy, S. F. Steady-state residual vibrations in high-speed, dwell-type, rotating disk cam-follower rod systems. J. Vib. Acoust. 127 (1), 12–17 (2005).

Natali, C., Battarra, M. & Theodossiades, S. Continuation analysis of cam–follower rod mechanisms considering time-varying stiffness and loss of contact. Nonlinear Dyn. 111 (18), 16921–16938 (2023).

Yousuf, L. S. & Marghitu, D. B. Nonlinear dynamics behavior of cam-follower rod system using concave curvatures profile. Adv. Mech. Eng. 12 (9), 1687814020945920 (2020).

Freudenstein, F. On the dynamics of high-speed cam profiles. Int. J. Mech. Sci. 1 (4), 342–349 (1960).

Zhang, X. R., Luo, G. W., Wang, Z. & An, X. L. Analysis of Low-Frequency vibration characteristics of cam with Flat-Faced follower mechanisms. J. Vib. Eng. Technol. 13, 190 (2025).

Cveticanin, L. Stability of movement of the cam–follower rod system. Mech. Mach. Theory. 42 (9), 1238–1250 (2007).

Han, J. W., Jie, H. & Chen, Y. Q. Design of the high-speed cam profile for the multi-DOF follower. Inst. Mech. Eng. Part. C J. Mech. Eng. Sci. 238 (15), 7585–7592 (2024).

Zhou, C. J., Hu, B., Chen, S. Y. & He, L. P. An enhanced flexible dynamic model and experimental verification for a valve train with clearance and multi-directional deformations. J. Sound Vib. 410, 249–268 (2017).

Alzate, R., Bernardo, M., Montanaro, U. & Santini, S. Experimental and numerical verification of bifurcations and chaos in cam-follower rod impacting systems. Nonlinear Dyn. 50, 409–429 (2007).

Alzate, R., Bernardo, M. & Giordano, G. Experimental and numerical investigation of coexistence, novel bifurcations, and chaos in a cam-follower rod system. SIAM J. Appl. Dyn. Syst. 8 (2), 592–623 (2009).

Tümer, S. T. & Ünlüsoy, Y. S. Nondimensional analysis of jump phenomenon in force-closed cam mechanisms. Mech. Mach. Theory. 26 (4), 421–432 (1991).

De Groote, W., Van Hoecke, S. & Crevecoeur, G. Prediction of follower rod jumps in cam-follower rod mechanisms: the benefit of using physics-inspired features in recurrent neural networks. Mech. Syst. Signal. Pr. 166, 108453 (2022).

Flores, P., Leine, R. & Glocker, C. Application of the nonsmooth dynamics approach to model and analysis of the contact-impact events in cam-follower rod systems. Nonlinear Dyn. 69, 2117–2133 (2012).

Sundar, S., Dreyer, J. T. & Singh, R. Rotational sliding contact dynamics in a non-linear cam-follower rod system as excited by a periodic movement. J. Sound Vib. 332 (18), 4280–4295 (2013).

Sundar, S., Dreyer, J. T. & Singh, R. Estimation of impact damping parameters for a cam–follower rod system based on measurements and analytical model. Mech. Syst. Signal. Pr. 81, 294–307 (2016).

Yousuf, L. S. & Marghitu, D. B. Experimental and simulation results of a cam and a flat-bottomed follower rod mechanism. J Comput. Nonlinear Dynam. 12 (6), 061001 (2017).

Mao, J. M., Zhu, Y. D., Yan, C. & Chen, G. Dynamic performance optimization of a planar mechanism with cam clearance joint based on non-uniform rational B-spline and reinforcement learning. Nonlinear Dyn. 113, 7779–7801 (2025).

Zayas, E. E., Cardona, S. & Jordi, L. Synthesis of displacement functions by Bezier curves in constant-breadth cams with parallel flat-bottomed double translating and oscillating follower rods. Mech. Mach. Theory. 62 (1), 51–62 (2013).

Zhou, C. J., Xiao, Z. L., Chen, S. Y. & Han, X. Normal and tangential oil film stiffness of modified spur gear with non-Newtonian elastohydrodynamic lubrication. Tribol Int. 109, 319–327 (2017).

Wei, Z., Chen, J. & Jin, G. Research on dynamic analysis and simulation of cam mechanism considering contact collision. Iran. J. Sci. Technol. Trans. Mech. Eng. 48, 1177–1190 (2024).

Shripad, K. M. R., Jeevanandam, S., Jeganathan, J. & Sriram, S. Modeling and analysis of a non-linear compliant rolling-sliding contact mechanism when subjected to a periodic motion input. Nonlinear Dyn. 1–31 (2025).

Yousuf, L. S. Nonlinear dynamics investigation of contact force in cam–follower system using Lyapunov exponent parameter, power spectrum analysis, and poincare’ maps. Australian J. Mech. Eng. 22 (5), 860–881 (2023).

Yousuf, L. S. Non-periodic motion reduction in globoidal cam with roller follower mechanism. Proc. Inst. Mech. Eng. Part C J. Mech. Eng. Sci. 236 (6), 2714–2727 (2022).

Yang, J. X. et al. Anwer N. Kinematic accuracy analysis for cam mechanism considering dynamic behavior and form deviations. Precision Eng. 88, 109–116 (2024).

Rao, R. V. & Pawar, R. B. Design optimization of cam–follower mechanisms using Rao algorithms and their variants. Evol. Intel. 17, 745–770 (2024).

Yu, J. et al. A novel piecewise high-order differential interpolation with rapid convergence to construct an ultrasmooth profile of high-speed cam with optimal dynamic performance. Mech. Based Des. Struc. 52 (10), 7778–7794 (2024).

Hsu, K. L., Tung, P. & Wu, L. L. Grooved cam mechanism with a translating follower having an added Ternary-Roller intermediate link. J. Mech. Des. 144 (6), 063304 (2022).

Prajapati, D. K. & Chander, P. Study of mixed-EHL traction coefficient between cam-roller follower interface under different operating conditions. Eng. Res. Express. 5 (2), 025020 (2023).

Català, P., Veciana, J. M. & Jordi, L. Energy loss comparison between kinematically equivalent mechanisms: Slider-crank and eccentric cam. Mech. Based Des. Struc. 52 (11), 9435–9457 (2024).

Guo, H. Q. et al. Transient lubrication of floating Bush coupled with dynamics and kinematics of cam-roller in fuel supply mechanism of diesel engine. Phys. Fluids. 36 (12), 123103 (2024).

Todorović, M. et al. Cam displacement curve optimization for minimal jerk using search and rescue optimization algorithm. Proc. Inst. Mech. Eng. Part. C J. Mech. Eng. Sci. 238 (21), 10332–10343 (2024).

Chen, Y. N. & Kuan, L. H. Necessary and sufficient design conditions for Over-Constrained cam mechanisms with Flat-Faced and roller follower. J. Mech. Robot. 1–38 (2025).

Flocker, F. W. Addressing cam wear and follower jump in single-dwell cam-follower systems with an adjustable modified trapezoidal acceleration cam profile. J. Eng. Gas Turbines Power. 131 (3), 032804 (2009).

Lassaad, W., Mohamed, T. & Yassine, D. Nonlinear dynamic behaviour of a cam mechanism with oscillating roller follower rod in presence of profile error. Front. Mech. Eng. 8, 127–136 (2013).

Chithra, A. & Raja, M. I. Multiple attractors and strange nonchaotic dynamical behavior in a periodically forced system. Nonlinear Dyn. 105 (4), 3615–3635 (2021).

Alzate, R., Piiroinen, P. T. & Bernardo, M. From complete to incomplete chattering: a novel route to chaos in impacting cam-follower rod systems. Int J. Bifurcat. Chaos. 22 (05), 1250102 (2012).

Zhao, Y. F. & Zhang, Y. X. Multiple Tori intermittency routes to strange nonchaotic attractors in a quasiperiodically-forced piecewise smooth system. Nonlinear Dyn. 112 (8), 6329–6338 (2024).

Wagg, D. J. Rising phenomena and the multi-sliding bifurcation in a two-degree of freedom impact oscillator. Chaos Solit Fractals. 22 (3), 541–548 (2004).

Luo, G. W. et al. Hunting patterns and bifurcation characteristics of a three-axle locomotive bogie system in the presence of the flange contact nonlinearity. Int. J. Mech. Sci. 136, 321–338 (2018).

Peterka, F. & Blazejczyk-Okolewska, B. Some aspects of the dynamical behavior of the impact damper. J. Vib. Control. 11 (4), 459–479 (2005).

Luo, G. W. et al. Diversity and transition characteristics of sticking and non-sticking periodic impact movements of periodically forced impact systems with large dissipation. Nonlinear Dyn. 94 (2), 1047–1079 (2018).

Yousuf, L. S. Investigation of chaos in a polydyne cam with flat-bottomed follower rod mechanism. J. King Saud Univ. Eng. Sci. 33 (7), 507–516 (2021).

Ünlüsoy, Y. S. & Tümer, S. T. Non-linear dynamic model and its solution for a high speed cam mechanism with coulomb friction. J. Sound Vib. 169 (3), 395–407 (1994).

Osorio, G., Bernardo, M. & Santini, S. Corner-impact bifurcations: A novel class of discontinuity-induced bifurcations in cam-follower rod systems. SIAM J. Appl. Dyn. Syst. 7 (1), 18–38 (2008).

Machado, M., Moreira, P., Flores, P. & Lankarani, M. Compliant contact force models in multibody dynamics: evolution of the Hertz contact theory. Mech. Mach. Theory. 53, 99–121 (2012).

Xia, Y. F., Pang, J., Yang, L. & Chu, Z. G. Investigation on clearance-induced vibro-impacts of torsional system based on Hertz contact nonlinearity. Mech. Mach. Theory. 162, 104342 (2021).

Yue, Y., Xie, J. H. & Gao, X. J. Determining Lyapunov spectrum and Lyapunov dimension based on the poincaré map in a vibroimpact system. Nonlinear Dyn. 69 (3), 743–753 (2012).

Duan, C. & Singh, R. Dynamic analysis of preload nonlinearity in a mechanical oscillator. J. Sound Vib. 301 (3–5), 963–978 (2007).

Lu, H., Zhou, J., Sahmani, S. & Safaei, B. Nonlinear stability of axially compressed couple stress-based composite micropanels reinforced with random checkerboard nanofillers. Phys. Scripta. 96 (12), 125703 (2021).

Acknowledgements

The authors gratefully acknowledge the support by National Natural Science Foundation of China (12172157, 12162019) and Gansu Science and Technology Planning Project (23JRRA861).

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

Xiaorong Zhang: Formal analysis, Software, Writing-original draft. Guanwei Luo: Project administration, Conceptualization, Writing-original draft. Zheng Wang: Analysis. Xinlei An: Analysis.Fengwei Yin: Analysis.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher’s note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Supplementary Information

Below is the link to the electronic supplementary material.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if you modified the licensed material. You do not have permission under this licence to share adapted material derived from this article or parts of it. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Zhang, X., Luo, G., Wang, Z. et al. Dynamics analysis of a cam with flat-bottomed follower system. Sci Rep 15, 29200 (2025). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-14991-0

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-14991-0