Abstract

Brown rot disease, caused by species of the genus Monilinia, is a significant fungal disease affecting pome and stone fruit trees. In this study, 565 samples were collected from symptomatic trees across six provinces of Iran between 2018 and 2022. A total of 430 fungal isolates were obtained and identified using both morphological and molecular techniques. PCR assays with species-specific primers revealed that 403 isolates belonged to Monilinia laxa and 27 to Monilinia fructigena. Sequencing of the ITS and Ef-1α gene regions was performed for 12 representative isolates, and Bayesian phylogenetic analysis confirmed species-level identification. Mating-type determination was carried out using newly designed primers targeting the Mat1-1-1 and Mat1-2-1 genes, successfully detecting both mating types in the two species. Pathogenicity tests on apricot, sour cherry, sweet cherry, and plum fruits demonstrated that all selected isolates were highly pathogenic, producing visible symptoms within 3 to 4 days post-inoculation, which led to complete fruit rot and mummification within 23 days. Morphological characterization showed that M. laxa colonies exhibited lobed margins and variable pigmentation, while M. fructigena had smooth colony margins with peach-colored centers. Conidia were blastic, aseptate, and formed in chains, with distinguishable size differences between species. This study provides comprehensive data on the distribution, genetic diversity, mating-type structure, and pathogenic potential of Monilinia spp. in Iran, offering valuable insights for disease monitoring and integrated management strategies in affected orchards.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Fruit trees, particularly pome and stone fruit trees, play a significant role in Iran’s agricultural economy. Iran is one of the major contributors to the nation’s agricultural output and a prominent producer of stone fruits in Asia and worldwide. Currently, the Iranian stone fruit industry covers an area of over 214,813 hectares with 1837562.34 tons of annual production1. Various biotic and abiotic factors affect the yield and productivity of stone fruit trees, with fungal and bacterial diseases being the main factors limiting production.

Brown rot disease, caused by species of Monilinia Honey (Sclerotiniaceae), poses a major threat to fruit production globally2. These economically important pathogens affect stone and pome fruit trees that have a worldwide distribution3, such as nectarines, peaches, almonds, plums, cherries, sour cherries, apricots, apples, quinces, and pears, in all major fruit-growing areas4,5,6. The disease leads to significant crop losses annually and affects fruit in the field pre-harvest and during storage and post-harvesting distribution5,7. Typical symptoms include blossom blight in early spring, followed by fruit rot or mummification later in the season8,9,10. Various studies have highlighted the impact of brown rot disease and its symptoms on fruit trees, emphasizing the need for effective disease management strategies.

Forty-three species names listed in the Index Fungorum11 for the Monilinia genus, two species have ex-type cultures, and sequence data are available for only 27 species2,12. Six closely related species, namely M. fructicola (G. Winter) Honey, M. fructigena (Pers.) Honey, M. laxa (Aderh. & Ruhland) Honey, M. mumeicola (Y. Harada, Y. Sasaki & Sano) Sand. -Den. & Crous, M. polystroma (G.C.M. Leeuwen) Kohn, and M. yunnanensis M.J. Hu & C.X. Luo ex Sand.-Den. & Crous are known as the cause of brown rot disease, and between them, three species, including M. fructicola, M. fructigena, and M. laxa, are the main causal agents of the disease in stone and pome trees worldwide4,6. The geographic distribution of these species influences the range of hosts they affect in different regions. In some countries, one or more species are known as the causative agent of brown rot, which varies depending on the host and geographical location13. For instance, in Iran, only two out of the 43 accepted species have been reported; in Brazil M. fructicola and M. laxa were characterized from stone fruit trees14 while in China, six species have been identified as causing brown rot on various hosts15.

The main problem in Monilinia species identification lies in the fact that, while morphological traits such as conidia size, stroma formation, colony shape, germination tube characteristics, and growth rate offer some diagnostic clues, they are not always sufficient for accurate species differentiation—particularly when dealing with geographical variants of the same species or closely related species16. Morphological plasticity—variations in form and structure driven by environmental factors—can further complicate the identification process10. This variability makes it difficult to rely on morphology alone, especially when there is significant overlap in traits, as seen in different populations of M. fructigena. For example, conidia size and stroma formation, commonly used to distinguish between regional populations of M. fructigena or closely related species like M. fructicola and M. laxa, may not consistently correlate with genetic differences, thereby hindering species separation based solely on morphology. As a result, reliance on morphological traits can be misleading, particularly when closely related species or regional variants exhibit similar forms17. Conventional identification methods have limitations, prompting the adoption of molecular techniques for improved accuracy18. Various molecular-based PCR technologies have become essential tools in fungal diagnostics. PCR amplification of genomic DNA followed by sequencing of the resulting amplicons has proven to be a valuable approach for fungal identification19. Molecular detection of Monilinia spp. is primarily performed by analyzing the ribosomal ITS region, as documented by several studies17,20,21. Multilocus molecular analyzing, including analysis of genes such as β-tubulin (tub2)15, cytochrome b (cytb)15,22, Glyceraldehyde 3-phosphate dehydrogenase (g3pdh)15,23, heat shock protein 60 (hsp60), acid protease (acp1), zinc finger transcription factor (pac1)24 and laccase (lcc2)25, have proven valuable in defining species boundaries and phylogenetic relationships within the genus. Besides that, the Ef-1α gene has also been used as a barcode to find the taxonomic position of the species of this genus2. Most recently, in the study by Silan and Ozkilink26, for the first time, the use of Calmodulin, SDHA, NAD2, and NAD5 regions was found to be phylogenetically informative and utilized for the phylogenetics of Monilinia species.

Species-specific molecular markers have been developed, offering more precise and faster detection methods compared to traditional techniques. Côté et al.27 introduced a method using multiplex PCR to distinguish between four Monilinia species (M. laxa, M. fructigena, M. polystroma, and M. fructicola) based on the lengths of PCR products obtained from a genomic region of unknown function. Following this, subsequent studies, such as that of Hu et al.15, provided specific primers and multiplex PCR methods to distinguish between five Monilinia species (M. laxa, M. polystroma, M. mumecola, M. yunnanensis, and M. fructicola) and some other closely related genera. Their study used multigene molecular analysis to describe a new species of Monilinia, M. yunnanensis, from China15. This approach highlights the significance of genotypic characters in accurately identifying and distinguishing fungal species, bypassing the limitations of traditional morphological methods.

Monilinia species reproduce by sexual and asexual means. While some species are known to undergo regular sexual and asexual stages in their life cycle (e.g., M. fructicola), other species are known based on asexual reproduction, e.g., M. polystroma. Sexual reproduction plays a significant role in genetic recombination and diversity of fungal species and populations28. There is not yet a report on sexual dimorphism in fungi, particularly ascomycetes, and sexual reproduction is governed by mating type loci, which span a short length of the chromosome. The MAT1 locus plays a critical role in controlling the mating system in fungi. The mating identity in ascomycetous fungi is determined by a single mating type locus with alternative MAT1-1 and MAT1-2 alleles. These alleles are referred to as idiomorphs due to their lack of sequence homology29. Fungal isolates can be classified as either heterothallic, carrying only one idiomorph at the mating type locus, or homothallic, possessing both mating type genes. Heterothallic isolates require individuals with opposite mating types for sexual reproduction, while homothallic isolates are self-fertile and capable of undergoing sexual reproduction without the need for a compatible partner6. The family Sclerotiniaceae includes both homothallic and heterothallic species, such as Botrytis cinerea Pers. and Sclerotinia sclerotiorum (Lib.) de Bary, however, heterothallism is dominant30. Botrytis cinerea exhibits bipolar heterothallism, with self-sterile individuals carrying either the MAT1-1 or MAT1-2 idiomorphs, while S. sclerotiorum displays homothallism, with self-fertile individuals carrying both MAT1-1 and MAT1-2 idiomorphs closely linked at a single MAT1 locus4. Very limited studies have analyzed the mating types of Monilinia species. Abate et al.4 investigated the mating system of M. fructicola, M. laxa, and M. fructigena, important pathogens causing brown rot disease in fruit trees from 10 countries. A heterothallic mating system was confirmed through a mating-type-specific PCR assay, with both MAT1-1 and MAT1-2 mating types existing among the isolates. The analyses of the genetic architecture structure of the MAT1 locus was conserved across species, but intergenic regions and flanking sequences showed some variability. Phylogenetic analysis confirmed the close relationship between Monilinia and other Sclerotiniaceae species. Ozkilink et al.6 mentioned that there was no direct evidence for the development of sexual fruiting bodies of brown rot disease fungi in Turkey but detected mating types of M. fructicola and M. laxa isolates via newly designed primers, with a 1:1 ratio frequency indicating the potential for the occurrence of sexual reproduction. This information is essential for understanding the genetic mechanisms underlying sexual reproduction in fungal populations and their impact on genetic diversity and adaptation.

According to our current knowledge, there are only two species of the Monilinia genus present in Iran31,32. Monilinia laxa has been found in apricot, cherry, sour cherry, plum, and peach, while M. fructigena has been found in pear, quince, and common medlar based on morphological characteristics, and to date, there is no molecular data available for the Monilinia species from Iran until the present study. Additionally, M. fructicola has been reported as a quarantine pathogen by the Iranian Plant Protection Organization. To date, the mating-type system for Monilinia spp. has not been investigated in Iran. Understanding the diversity, distribution, and mating systems of Monilinia pathogens is essential for effective disease management strategies in orchards.

This study aimed (1) to identify the causal agents of brown rot disease in stone fruits orchards of Iran by means of morphological characteristics, molecular data, including multigene phylogeny and multiplex PCR; (2) explore the distribution of mating types alleles using newly designed primers via multiplex PCR assay in Iran.

Results

Field symptoms and species of Monilinia pathogens

Field symptoms of brown rot disease can be classified into two types in pome and stone fruit trees (Fig. 1): blossom blight (Fig. 1a-b-c), which occurs early in the growing season, and fruit rot, which develops later (Fig. 1d-e-f). At the beginning of the season, the disease initially manifests as petal necrosis, leading to the destruction of blossoms and flowers. Under favorable environmental conditions, the causative fungus gradually invades the flower stalk and spreads to the branch tips and twigs. This results in the desiccation of the blossoms, which remain attached to the tree. Over time, the vascular system at the infection site becomes obstructed, causing gum to exude at the point where the flower stalk connects to the twig. If the weather conditions are suitable for the pathogen, in organic production fields or orchards with poor maintenance, nearly 100% of the tree blossoms may be destroyed, with the second phase of the disease, related to fruit rot, not being observed due to the absence of fruit (for example, a 100% infection rate of apricot trees was reported in 2020 in Shabestar County, East Azerbaijan province). At the end of the season, as the fruit ripens, the second phase of symptoms appears, provided that temperature and humidity conditions are appropriate. Ripe or wounded fruits, caused by insect feeding or wind, are more susceptible to infection. In some areas, even unripe fruits with wounds may become infected. Infected fruits display soft, decayed tissue (Fig. 1d-e) and, over time, either fall to the ground or remain on the tree as mummified fruits (Fig. 1f).

Ultimately, a total of 430 isolates were obtained from various hosts, including apricot, almond, cherry, sour cherry, greengage, plum, peach, apple, quince, cornelian cherry, and pear, as well as Mirabelle plum, during field surveys conducted in East Azerbaijan, West Azerbaijan, Ardabil, Gorgan, and Lorestan provinces. Zanjan was the only province from which no isolates were obtained. We inspected stone fruit orchards in Zanjan province in two consecutive years and did not encounter evident symptoms of brown rot on stone fruit trees in the Zanjan region. This is important to note that the epidemics of brown rot disease in blooming stage (spring) is highly dependent on weather conditions (prolonged wet and consecutive rainy days). Given the climate condition in the Zanjan region (low precipitation and rather high temperature) during summer the incidence of brown rot symptoms on ripen fruits is uncommon. These isolates were initially assessed morphologically; however, due to overlapping morphological characteristics, molecular identification was used. In the first step, all isolates were confirmed to belong to the genus Monilinia by amplifying a 353-bp fragment using the PRCmon-F and PRCmon-R primer pair (Fig. 2). Further molecular characterization identified the species: M. laxa was confirmed by a 351-bp product, while M. fructigena was identified by a 402-bp product, both generated using the MO368-5, MO368-8R, 368-10R, and Laxa-R2 primer sets (Fig. 3). Additionally, a 501-bp product for M. laxa and a 783-bp product for M. fructigena were obtained using the P450intron6-2-fwd and P450intron6-2-rev primer pair (Fig. 4). Both molecular markers consistently provided the same results for species identification. None of the isolates produced more than one band or any unexpected products, and the negative controls yielded no amplicons for either marker system.

A total of 403 isolates were identified as M. laxa from the collected samples, while 27 isolates were classified as M. fructigena. The distribution of species varied across the provinces, as shown in Table 1. In the five provinces sampled for this study, M. laxa and M. fructigena were predominantly found, with East Azerbaijan being the only province where both species were identified. All isolates from West Azerbaijan, Ardabil, Golestan, and Lorestan were found to be M. laxa. Although East Azerbaijan yielded both species, M. laxa was the more dominant one (Table 1).

The results of a multiplex PCR assay on selected isolates of three Monilinia species were obtained using the primers MO368-8R, MO368-10R, LaxaR-2, and MO368-5, as designed by Côté et al.27. (M291–M190: isolates identified as M. laxa); (M242 and M213: isolates identified as M. fructigena); (LAX: Monilinia laxa); (FRG: Monilinia fructigena); (FRC: Monilinia fructicola); (L: 100 bp ladder); (N: negative control in the PCR reaction).

PCR results using the primer set P450intron6-2-fwd and P450intron6-2-rev designed by Hily et al.22. (G52-M190: isolates were identified as M. laxa through the amplification of a 501 bp band); (M242 and M213: isolates were identified as M. fructigena by amplifying a 783 bp band); (LAX: Monilinia laxa); (FRG: Monilinia fructigena); (FRC: Monilinia fructicola); (L: 100 bp ladder); (N: negative control).

Phylogenetic analysis

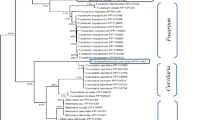

The identity of twelve isolates selected for this study was confirmed through multi-locus sequence comparison of the ITS-rDNA region and Ef-1α gene sequences. These sequences were compared to BLASTN nucleotide databases using a nucleotide query publicly available in GenBank. The final concatenated alignment included 1,063 characters (including alignment gaps), representing 52 Monilinia spp. taxa, of which 39 were obtained from NCBI and 12 were from the present study. Chlorociboria aeruginosa (Oeder) Seaver ex C.S. Ramamurthi, Korf & L.R. Batra (isolate AFTOL-ID151) was used as the outgroup. The gene boundaries for the alignment were as follows: ITS (positions 1–507) and Ef-1α (positions 508–1063). Six artificially introduced spacer characters between the partitions were excluded from the phylogenetic analysis.

Based on the model selection results from MrModelTest, Bayesian phylogenetic analyses were conducted using the GTR + G substitution model for the ITS region and the HKY + G model for the Ef-1α gene. Both models incorporated gamma rate variation with Dirichlet-distributed base frequencies. The alignment comprised 552 unique site patterns, with 184 patterns corresponding to the ITS region and 368 to the Ef-1α gene. The Bayesian analysis was run for 1,000,000 generations, and 1502 trees were sampled. After excluding the first 25% of trees as burn-in, the consensus tree and posterior probabilities (PP) were calculated from the remaining 1127 trees. Among the analysed characters, 322 were constant, 170 were variable and parsimony-uninformative, while 571 were parsimony-informative. A parsimony consensus tree was generated from the equally most parsimonious trees, with branches represented by thicker lines on the Bayesian tree (length = 1937, CI = 0.673, RI = 0.906, RC = 0.610, HI = 0.327). The resulting phylogeny, shown in Fig. 5, of the ITS and Ef-1α sequences placed 10 of the isolates within the M. laxa clade, while two isolates were grouped with M. fructigena. The sequence data generated in this study have been deposited in NCBI GenBank database (Table 2).

Consensus phylogram (50% majority rule) resulting from a Bayesian analysis of the combined ITS and Ef-1α sequence alignment using MrBayes v. 3.2.6. The Bayesian posterior probabilities (PP) and maximum parsimony bootstrap support values (MP-BS) are given at the nodes (PP/MP-BS), and the bar indicates 0.1 expected changes per site. Sequences obtained in this study are highlighted in blue. The tree is rooted with Chlorociboria aeruginosa as the outgroup.

Molecular assay of mating type distributions

Primer pairs Mat1-MoF (OD: 4.67; 21.6 nmol) (5-CGAAGAATCACGACCATGTATG-3) and Mat1-MoR (OD: 9.86; 18.1 nmol) (5-TCGATACACGGTACTCAGTATC-3) were designed for the Mat1-1-1 gene, and primer pairs Mat2-MoF (OD: 5.32; 27.6 nmol) (5-TCATCCCAGTTGTCTCATCAG-3) and Mat2-MoR (OD: 4.15; 21.9 nmol) (5-TCGTTCAACTCGGAGAATGG-3) were intended for the Mat1-2-1 gene. In examinations related to mating type detection, aimed at reducing both the testing time and laboratory consumables, and after confirming that the primers designed in this study are capable of detecting mating types in a single reaction, a protocol based on multiplex PCR was developed. The results of the multiplex PCR, designed for rapid mating-type determination of Mat1-1-1 and Mat1-2-1, showed that isolates with the Mat1-2 mating type produced a single band at 1086 base pairs, while isolates with the Mat1-1 produced a single band at 910 base pairs (Fig. 6). These mating types were detected in both M. laxa and M. fructigena, as well as in M. fructicola. The effectiveness of the primers in the multiplex protocol was demonstrated for all isolates, even when two isolates with different mating types were amplified in a single reaction. The bands corresponding to each mating type were successfully amplified separately. No bands were observed in the negative control during the experiment. The distribution of mating types in each province, along with the number of isolates corresponding to each mating type, is presented in Table 1. Our Sequence data of the mating type genes obtained in this study were 100% matched with the sequence data deposited in the core nucleotide BLAST database of NCBI for MAT1-1-1 and MAT1-2-1 gene of M. laxa (accession numbers: MG182161.1 and MG182164.1 respectivly) and MAT1-2 of M. fructigena (accession number: MG182165.1).

Touchdown multiplex PCR amplification using newly designed primers to detect the Mat1-1 and Mat1-2 genes in Monilinia laxa, M. fructigena, and M. fructicola species on a 1.2% agarose gel. Isolates with mating type MAT1 exhibit a single band at 910 bp, while those with MAT2 show a single band at 1086 bp. (LAX: Monilinia laxa); (FRG: Monilinia fructigena); (FRC: Monilinia fructicola); (L: 100 bp ladder); (N: negative control).

Morphological characterization

The isolates identified as Monilinia laxa exhibited a growth rate that resulted in colony diameters ranging from 56 to 76 mm after seven days of incubation. The mycelial growth displayed distinct layering or rose-shaped patterns with lobed colony margins; however, concentric rings were not observed. The colony color in potato dextrose agar (PDA: Merck, Germany) cultures varied among isolates, and the morphology of the mycelial growth served as a distinguishing feature for grouping the Iranian isolates. Conidia were produced on aerial mycelium after 9 to 12 days of incubation, with sporulation textures varying from gray to light brown or olive and occasionally hazel in color.

In contrast, M. fructigena isolates showed a growth rate resulting in colony diameters of 70–74 mm after seven days. The colony margins were smooth or nearly smooth, and the colony color shifted to a greyish hue, with a light peach-colored mycelial mass visible at the center. The sporulation texture of M. fructigena appeared light brown, and concentric rings were absent. Both M. laxa and M. fructigena isolates produced conidia that were blastic, limoniform (lemon-shaped), and occasionally ovoid. These conidia were aseptate and arranged in chains. The conidia of M. laxa measured 10–19 × 7–11 μm, while those of M. fructigena measured 13.14–21.9 μm × 9.4–14.9 μm. Additionally, all selected isolates for both species exhibited black arcs that developed after 12–15 days of incubation, and the sexual stage was not observed.

Pathogenicity of the selected isolates

The pathogenicity assessment of the selected isolates on different fruits revealed no significant differences among the isolates. Symptoms began to appear three to four days post-inoculation, manifesting as darkening, disintegration, and internal tissue rot. The fruits became excessively soft and, after 7 to 10 days, were completely decayed. The fungal hyphal tissue, after colonizing the internal parts of the fruit, emerged on the surface, and by days 5 to 13, the entire surface of the fruit was covered with fungal tissue. Ultimately, 23 days after inoculation, the fruits lost their moisture and became completely shriveled, leaving only cotton-like fungal tissue and mummified remains; however, after three months, no sclerotia had been observed. The negative control fruits remained healthy. After culturing the inoculated fruits using the same initial isolation method, the fungal isolates were successfully re-isolated.

Discussion

Iran plays a prominent role in the Middle East, particularly in agriculture, and stands out as a key producer of both pome and stone fruits in the region. The climatic conditions during the spring and summer are highly conducive for the development and spread of brown rot disease, caused by Monilinia species. This has made the disease a serious issue in the realm of plant protection. Although Monilinia species are known to affect stone and pome fruits globally, there is a scarcity of detailed studies on Iranian isolates, and their genetic variation remains largely unexplored. To address this gap, the current research is the first comprehensive investigation of the Monilinia species, examining the genetic diversity and distribution of collected isolates from five provinces in Iran. This was achieved through PCR amplification using species-specific primers, followed by multigene phylogenetic analysis. We conducted a thorough assessment of a total of 430 isolates obtained from five provinces using three sets of species-specific primer pairs: PRCmon-F and PRCmon-R; MO368-8R, MO368-10R, LaxaR-2, and MO368-5; and P450intron6-2-fwd and P450intron6-2-rev. This initial screening allowed us to ensure accurate species identification. To complement our analysis, we selected 12 representative isolates for sequencing, based on their geographic diversity and host, as detailed in Table 2. The amplified gene regions (ITS-rDNA and Ef-1α) for these 12 isolates demonstrated that the combined use of the two regions provided improved resolution for species differentiation, although the performance of the Ef-1α gene alone was also acceptable when compared to the rDNA-ITS region2,12,14. For the first time in Iran, ITS-rDNA region (genus-level barcode) and the Ef-1α gene (species-level barcode) were successfully amplified for 12 isolates and submitted to the GenBank database. In conclusion, the findings revealed that the majority of the isolates (93%) belonged to M. laxa, while only a small fraction (approximately 7%) were identified as M. fructigena. Monilinia laxa was detected across a wide range of fruit hosts, including apricot, almond, cherry, sour cherry, greengage, plum, peach, apple, quince, pear, and mirabelle plum, in all five provinces. Monilinia laxa is widely recognized as the predominant pathogen of brown rot disease in various regions across the globe, including Asia, Europe, America, Africa (specifically South Africa), and Oceania33. This pathogen, commonly referred to as European brown rot, has been documented in nearly all European countries34.

In contrast, M. fructigena was isolated from the cornelian cherry and quince only in East Azerbaijan. Monilinia fructigena is a key pathogen of brown rot in pome fruits, especially apples and pears, found across Europe, Asia, northern Africa, and parts of South America. It causes significant economic losses in orchards and storage, with damage varying based on climatic conditions. The pathogen infects fruit through lenticels, contact, or damage, and under favorable conditions, it leads to fruit mummification and the formation of pseudosclerotia, which serve as primary inoculum for the next season. M. fructigena is the most common cause of brown rot in Poland13.

Moreover, host specificity has not been reported among the various host ranges of Monilinia species. The host range of this genus includes plant families such as Actinidiaceae, Betulaceae, Cornaceae, Ebenaceae, Elaeagnaceae, Ericaceae, Moraceae, Myrtaceae, Rosaceae, Solanaceae, and Vitaceae12. In the present study, no evidence was found to suggest that the M. laxa isolates were specific to their respective hosts, nor were any other Monilinia species detected in Iran. The results of this study demonstrate that M. laxa is the predominant pathogen responsible for brown rot disease in Iran. Furthermore, it would be of considerable interest to monitor potential changes in the species composition over time, as such data would be instrumental in formulating effective disease management strategies.

Previous studies have demonstrated that Monilinia species exhibit a heterothallic mating system characterized by only one mating type idiomorph per isolate. A search for mating types within the genus Monilinia in academic databases, including Google Scholar and others, revealed only two relevant studies: those conducted by Abate et al.4 and Ozkilinc et al.6. A review of the literature revealed that Ozkilinc et al.6 encountered many amplification problems when employing the primer sets designed by Abate et al.4 to investigate mating types in isolates of M. fructicola and M. laxa. Consequently, Ozkilinc et al.6 proceeded to design alternative primer sets. However, the results of their study indicated that the primers designed failed to determine the mating type in some isolates and amplified non-specific 420 bp band. While they asserted that this amplified fragment was not related to the mating type gene based on sequence data, this prompted us to design primers that would, firstly, avoid the amplification of extraneous fragments, and secondly, enable multiplex PCR in a single reaction. Based on our results, in Iran, there have been no direct observations of the sexual structures of M. laxa and M. fructigena; however, our findings confirmed the presence of both mating types within each species. Interestingly, isolates with different mating types were found not only on distinct hosts but also on the same individual trees. Our field observations and sampling did not yield any signs of sexual reproduction. The fact that this population mainly reproduces through cloning, with sexual reproduction seemingly rare, could stem from several factors. First, M. laxa produces a large number of conidia at just the right time to infect vulnerable plant tissue. Second, the unfavorable weather conditions (hot and dry) prevalent in our country during summer and autumn may not favor the development of apothecia. Finally, agricultural practices such as the use of chemicals, combined with the removal of infected twigs and fruit or the burial of mummified fruit during summer, autumn and winter, may also contribute. Our results are in agreement with previous studies such as Abate et al.4 and Ozkilinc et al.6 in their study despite the presence of both mating types in various regions and species, sexual reproductive structures were not observed. No significant relationship was observed between the prevalence of a given Monilinia species and its mating type. Similar patterns have been reported from Italy, where various hosts carried different Monilinia species, and a balanced 1:1 ratio of mating types was observed in both M. fructicola and M. laxa populations4. Such distribution patterns imply the potential for sexual recombination within these populations, which may contribute to their genetic variability. In this study, we developed new primer pairs specific to each mating type and employed a touchdown multiplex PCR approach to identify mating types in isolates of M. laxa, M. fructigena, and M. fructicola. The mating type distribution for the whole Iranian M. laxa isolates collection was in a 1:1 ratio of mating types (Table 1). The M. laxa isolates exhibited both mating types across various hosts in different provinces. However, in Lorestan province, where isolates were exclusively obtained from apple, only the Mat1-1 mating type was detected. It is worth noting that the limited number of isolates from this region may have influenced this outcome. Whether apple tree infections are exclusively caused by M. laxa isolates with the Mat1-1 mating type requires further evaluation through extensive sampling. Additionally, the occurrence of infections in Cornelian cherry in East Azerbaijan by M. fructigena isolates with the Mat1-2 mating type highlights the potential for a founder effect within these populations. Among the 27 M. fructigena isolates examined, only two from quince (collected in Kaleybar County, East Azerbaijan) carried the Mat1-1 idiomorph, whereas all 25 isolates from cornelian cherry (collected in Kaleybar County, East Azerbaijan) possessed the Mat1-2 idiomorph. In this study, M. fructigena isolates with different mating type idiomorphs were obtained exclusively from quince and cornelian cherry, each host exhibiting distinct mating types within the same region.

This study provides a comprehensive characterization of Monilinia pathogens responsible for brown rot in pome and stone fruit trees in Iran. The pathogens were identified molecularly through the use of specific primers and phylogenetic analyses, along with assessments of their pathogenicity and mating types. Additionally, novel molecular markers were developed to detect the mating types of M. laxa, M. fructigena, and M. fructicola. These findings offer foundational data for further investigations into the population genetics of these species, as well as the application of LAMP (Loop-mediated Isothermal Amplification) techniques. Ongoing research into these aspects of the pathogens is underway, and the results will be shared in future publications.

Materials and methods

Sample collection and fungus isolation

Samples were collected from infected trees with typical brown rot disease symptoms from the spring of 2018 to the summer of 2022. At the journey’s end, 565 samples were collected with the permission of the landowners, mostly from orchards located in major production areas of different hosts (20 tree species) and geographical regions, including East Azerbaijan, West Azerbaijan, Ardabil, Gorgan, Zanjan, and Lorestan provinces (Fig. 7). The samples taken from hosts were cultured in acidified potato dextrose agar (PDA: 200 ml juice from 200 g potato, 20 g dextrose, and 18 g agar L− 1) after surface-sterilization except the fruit samples that transferred conidia from the fruit onto the surface of 2% water agar (WA) in Petri dishes, and incubated at 25 °C. Finally, isolates were obtained from the collected samples after purification and storage at the mycological laboratory of the University of Tabriz.

DNA extraction and specific molecular identification

For the molecular characterization, all of the isolates were cultured on Potato Dextrose Agar (PDA: 200 ml juice from 200 g potato, 20 g dextrose, and 18 g agar L− 1) for eight days and maintained at 25 °C in an incubator. The total genomic DNA from the isolates was extracted following the protocol outlined by Möller et al.35. For PCR-based identification, two multiplex PCR methods were employed in this study to screen, distinguish, and characterize the collected isolates. In the first step, to confirm that all obtained isolates belong to the genus Monilinia, the primer pairs PRCmon-F and PRCmon-R, designed by Hu et al.15 based on the G3PDH gene, were utilized. This amplification produced a 354 bp fragment from all Monilinia species and was applied to all isolates. Additionally, DNA was amplified in a multiplex PCR using the reverse primer MO368-5, which is specific for Monilinia spp., along with three species-specific forward primers: MO368-8R for M. fructigena and M. polystroma, MO368-10R for M. fructicola, and Laxa-R2 for M. laxa27. This approach aimed to amplify a non-coding region of Monilinia spp. with an unknown function. Each multiplex PCR was conducted according to the protocols described by the authors of the respective methods. In the subsequent step, a single PCR amplification was performed using primer pairs P450intron6-2-fwd and P450intron6-2-rev, as described by Hily et al.22focusing on the cytb gene structure. This amplification allowed for the distinction between M. fructicola, M. laxa, and M. fructigena, producing fragment sizes of 621 bp, 501 bp, and 783 bp, respectively.

Geographical locations of East Azerbaijan, West Azerbaijan, Ardabil, Golestan, and Lorestan provinces of Iran, from which Monilinia isolates were collected in the current study. The map was created using QGIS software (version 3.44; available at https://qgis.org/download/).

PCR amplification of rDNA-ITS region and Ef-1α gene

At this phase of the study, 12 isolates were selected for sequencing and phylogenetic studies. Accordingly, primers ITS1 and ITS436 were employed to amplify the ITS1-5.8 S-ITS2 region (DNA barcode at genus level). Subsequently, the primer set EF1-728 F and EF-214 were utilized to amplify a portion of the translation elongation factor 1-alpha (Ef-1α) gene (DNA barcode at species level). PCR amplifications were conducted in a total reaction volume of 25 µL using an MJ Mini thermal cycler PCR system (Bio-Rad Laboratories, Inc.). The protocols and conditions for standard PCR amplification of these loci adhered to the methods described by Golmohammadi et al.37. Subsequently, PCR products were sent to the services of Microsynth (Balgach, Switzerland) for sequencing, which was performed using the PCR primer.

Construction of phylogenetic trees

The raw trace files were analyzed and edited using MEGA v.7 software38, resulting in the manual generation of consensus sequences from forward reads. To identify related taxa, the newly generated sequences were subjected to BLAST analysis against the NCBI GenBank database using mega BLAST. The sequences retrieved from GenBank, in conjunction with the novel sequences obtained in this study, were aligned using the MAFFT v.7 online interface with default parameters39 for each gene and subsequently refined manually in MEGA v.7 as needed.

For phylogenetic analysis, Bayesian inference (BI) and maximum parsimony (MP) methods were employed to assess the phylogenetic relationships within the aligned combined dataset. Bayesian inference (BI) was conducted on the concatenated data from the ITS and Ef-1α loci using MrBayes 3.2.640. The optimal evolutionary model for each data partition was determined with MrModelTest v.2.341. The heating parameter was set to 0.15, and Markov Chain Monte Carlo (MCMC) analysis was run in parallel with four chains initiated from a random tree topology, continuing until the average standard deviation of split frequencies dropped below 0.01. Trees were sampled every 1,000,000 generations, with the initial 25% of the saved trees discarded as burn-in. Posterior probabilities (PP) were calculated based on the remaining trees. The Maximum parsimony phylogenetic analysis was performed using PAUP v. 4.042 with a heuristic search strategy involving tree-bisection-reconnection branch swapping. Bootstrap resampling was used to assess clade support, and tree statistics (tree length, consistency index, retention index, rescaled consistency index and homoplasy index) were calculated to evaluate phylogenetic signal. The final phylogenetic tree was visualized using FigTree v. 1.4.343. Additionally, the sequences generated during this study were submitted to the NCBI GenBank nucleotide database (http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov).

Primer design and experimental setup for MAT gene amplification

Mating type genes of three Monilinia species, including M. laxa, M. fructigena, and M. fructicola obtained from the National Center for Biotechnology Information (NCBI) database based on Abate et al.4. MAT 1-1-1 gene accession numbers for three species were MG182161, MG182162, MG182163, and MAT 1-2-1 gene accession numbers were MG182164, MG182165, and MG182166, respectively. Primer sets were developed following the approach outlined by Bakhshi and Zare44. Sequence alignment was performed using MEGA version 7 software to identify conserved regions suitable for primer binding. Based on these alignments, forward and reverse primers were designed using the OligoCalc tool for oligonucleotide property analysis45. The designed primers were synthesized by Microsynth company (Switzerland). To determine the optimal amplification conditions, a series of PCR mixtures and thermal cycling protocols were tested. This optimization aimed to establish reliable conditions for the amplification of specific regions within the Mat1-1-1 and Mat1-2-1 mating-type genes. In PCR analysis, we obtained some unexpected bands in 600–750 bp, hence, a touchdown multiplex PCR conditions were applied for Mat1-1-1 and Mat1-2-1 gene primers: initial denaturation (94 °C, 5 min), five amplification cycles (94 °C, 30 s; 61 °C, 40 s; 72 °C, 1 min), five amplification cycles (94 °C, 30 s; 59 °C, 40 s; 72 °C, 1 min), 30 amplification cycles (94 °C, 30 s; 57 °C, 40 s; 72 °C, 1 min) and a final extension (72 °C, 8 min).

The PCR reaction was conducted with a total volume of 12.5 µL per reaction mixture on a MyCycler thermal cycler system (Bio-Rad Laboratories, Inc.), which included 5 µL of Taq DNA Polymerase 2x Master Mix (red) from Ampliqon (Stenhuggervej, Denmark), 0.5 µL (18.1–27.6 nmol) of each primer, 3.5 µL of dH2O, and 1 µL (20–40 nanogram) of the DNA template. All isolates were tested using this protocol. The PCR products were visualized on a 1.2% agarose gel, stained with 0.7 µL of DNA Safe Stain (Pishgam Biotech Company, Tehran, Iran), and analyzed with the XR gel documentation system connected to Quantity One software (Bio-Rad Laboratories, Inc.). The MAT1-1 to MAT1-2 idiomorphs’ ratio was tested to determine whether the deviation was significantly different from the 1:1 ratio by Chi-square test in sampling groups from different provinces. Furthermore, partial sequences of Mat1-1-1 and Mat1-2-1 genes were obtained for several representative isolates considering different sampling locations (isolates CCTUG52 and CCTUG109 for Mat1-1 and isolates CCTUM190, CCTUG120 and CCTUM213 for Mat1-2) to confirm if targeted regions were amplified. Selected amplicons were sent to the services of Codon Genetic Group (Tehran, Iran) for sequencing.

Morphological identification of selected Monilinia spp

Cultural characteristics such as macro- and micromorphology, color, margin and colony shape, sporulation, presence of concentric rings, medium pigmentation, growth rates, conidial dimensions, and germination tube were observed. Conidiophores and conidia were examined using an Olympus BX 41 light microscope. Colony features were assessed on Potato Dextrose Agar (PDA; Merck, Germany). A five-mm diameter plug of 7-day-old actively growing mycelium was placed onto the PDA and incubated under near-ultraviolet light with a 12-hour light/dark cycle at a temperature of 25 °C. Thirty measurements of conidial dimensions were recorded. High-resolution images of the fungal structures were captured using an Olympus digital camera system (DP 25) attached to the Olympus BX 41 light microscope. The images were processed with Adobe Photoshop CS6 (Adobe Systems Inc.). The fungal isolates were deposited in the Culture Collection of Tabriz University (CCTU).

Pathogenicity assay

The pathogenicity of the obtained isolates were evaluated based on the protocol explained in Poniatowska et al.13 with some modifications. The selected isolates for molecular studies—screened according to host, geographic region, and mating type—were examined through artificial inoculation. To this end, mature, healthy, and uniform fruits of apricot, sour cherry, sweet cherry, and plum were collected during different seasons of the year. Surface sterilization of the fruits involved thoroughly washing them under running water, followed by immersion in a 3% sodium hypochlorite solution for five to eight minutes. Afterward, the fruits were placed in a 73% ethanol solution for five minutes, then rinsed three times with sterile distilled water in a laminar flow workstation, with each rinse lasting five minutes, and finally dried on sterilized paper. Based on the fruit size used in the pathogenicity test, a small cavity was created in the middle section of each fruit, and a mycelial plug from each isolate was cut to approximately the same size and placed in the cavity, with three replications for each isolate. For the negative control group, three fruits from each host were utilized, and fresh sterile agar discs were used to replace the fungal plugs.

After performing this procedure on all 12 selected isolates, the inoculated sites were sealed with Parafilm, and the fruits were placed in a transparent plastic container with approximately 95% humidity. The container was then incubated at 25 ± 2 °C. After eight days, the fruits were inspected, and the symptoms that appeared were recorded. Finally, to complete Koch’s postulates, the inoculated fruits were cultured on PDA medium after surface sterilization, following the initial isolation method.

Data availability

All isolates obtained in this study are maintained in a viable state in 2 mL microtubes containing nutrient culture medium and are preserved with their respective culture codes at the Mycology Laboratory of the University of Tabriz (Culture Collection of Tabriz University: CCTU). It should also be noted that the extracted genomes of all isolates are likewise stored at the same location. The sequencing data generated in current study have been deposited in the NCBI GenBank database (International Nucleotide Sequence Database Collaboration member participating databases) (accession numbers: PQ660175, PQ655471; PQ660176, PQ655472; PQ660177, PQ655465; PQ660178, PQ655466; PQ660179, PQ655467; PQ660180, PQ655468; PQ660181, PQ655469; PQ660182, PQ655470; PQ660183, PQ655474; PQ660185, PQ655475; PQ655448, PQ660184; PQ655473).

References

FAO. https://www.fao.org/faostat/en/#data/QCL (2025).

Marin-Felix, Y. et al. Genera of phytopathogenic fungi: GOPHY 1. Stud. Mycol. 86, 99–216. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.simyco.2017.04.002 (2017).

Vilanova, L., Valero-Jiménez, C. A. & van Kan, J. A. Deciphering the Monilinia fructicola genome to discover effector genes possibly involved in virulence. Genes 12, 568. https://www.mdpi.com/2073-4425/12/4/568# (2021).

Abate, D. et al. Mating system in the brown rot pathogens monilinia fructicola, M. laxa, and M. fructigena. Phytopathology 108, 1315–1325. https://doi.org/10.1094/PHYTO-03-18-0074-R (2018).

Marcet-Houben, M. et al. Comparative genomics used to predict virulence factors and metabolic genes among Monilinia species. J. Fungi. 7, 464. https://doi.org/10.3390/jof7060464 (2021).

Ozkilinc, H. et al. Species diversity, mating type assays and aggressiveness patterns of Monilinia pathogens causing brown rot of Peach fruit in Turkey. Eur. J. Plant Pathol. 157, 799–814. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10658-020-02040-7 (2020).

Larena, I. et al. Biological control of postharvest brown rot (Monilinia spp.) of peaches by field applications of Epicoccum nigrum. Biol. Control. 32, 305–310. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.biocontrol.2004.10.010 (2005).

Baltazar, E. et al. Morphological, molecular and genomic identification and characterisation of monilinia fructicola in Prunus persica from Portugal. Agronomy 13, 1493. https://doi.org/10.3390/agronomy13061493 (2023).

Holb, I. Brown rot: causes, detection and control of Monilinia spp. Affecting tree fruit. In Integrated Management of Diseases and Insect Pests of Tree Fruit Ch. 103–150 (Burleigh Dodds Science Publishing, 2019).

Hrustić, J., Mihajlović, M. & Tanović, B. Morphological, cultural and ecological characterization of Monilinia spp., pathogens of stone fruit in Serbia. Pestic. Phytomed. 35, 39–48. https://doi.org/10.2298/PIF2001039H (2020).

Index Fungorum. https://www.indexfungorum.org/names/Names.asp (2025).

Jayawardena, R. S. et al. One stop shop V: taxonomic update with molecular phylogeny for important phytopathogenic genera: 101–125 Fungal Diversity, 1-167, (2024). https://doi.org/10.1007/s13225-024-00542-x (2025).

Poniatowska, A., Michalecka, M. & Bielenin, A. Characteristic of Monilinia spp. Fungi causing brown rot of pome and stone fruits in Poland. Eur. J. Plant Pathol. 135, 855–865. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10658-012-0130-2 (2013).

Fischer, J., Savi, D., Aluizio, R., De Mio, M., & Glienke, C. Characterization of Monilinia species associated with brown rot in stone fruit in Brazil. Plant. Pathol. 66, 423–436. https://doi.org/10.1111/ppa.12578 (2017).

Hu, M. J., Cox, K. D., Schnabel, G. & Luo, C. X. Monilinia species causing brown rot of Peach in China. PLoS One. 6, e24990. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0024990 (2011).

Petróczy, M., Szigethy, A. & Palkovics, L. Monilinia species in hungary: morphology, culture characteristics, and molecular analysis. Trees 26, 153–164. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00468-011-0622-2 (2012).

Van Leeuwen, G. C., Baayen, R. P. & Jeger, M. J. Distinction of the Asiatic brown rot fungus Monilia Polystroma sp. Nov. From M. fructigena. Mycol. Res. 106, 444–451. https://doi.org/10.1017/S0953756202005695 (2002).

Maurer, J. J. Rapid detection and limitations of molecular techniques. Annual Rev. Food Sci. Technol. 2, 259–279. https://doi.org/10.1146/annurev.food.080708.100730 (2011).

Hariharan, G. & Prasannath, K. Recent advances in molecular diagnostics of fungal plant pathogens: a mini review. Front. Cell. Infect. Microbiol. 10, 600234. https://doi.org/10.3389/fcimb.2020.600234 (2021).

Holst-Jensen, A., Kohn, L. M., Jakobsen, K. S. & Schumacher, T. Molecular phylogeny and evolution of Monilinia (Sclerotiniaceae) based on coding and noncoding rDNA sequences. Am. J. Bot. 84, 686–701. https://doi.org/10.2307/2445905 (1997).

Ioos, R. & Frey, P. Genomic variation within Monilinia laxa, M. fructigena and M. fructicola, and application to species identification by PCR. Eur. J. Plant Pathol. 106, 373–378. https://doi.org/10.1023/A:1008798520882 (2000).

Hily, J. M., Singer, S. D., Villani, S. M. & Cox, K. D. Characterization of the cytochrome b (cyt b) gene from Monilinia species causing brown rot of stone and pome fruit and its significance in the development of QoI resistance. Pest Manag. Sci. 67, 385–396. https://doi.org/10.1002/ps.2074 (2011).

Yin, L. F. et al. Identification and characterization of three Monilinia species from Plum in China. Plant Dis. 99, 1775–1783. https://doi.org/10.1094/PDIS-12-14-1308-RE (2015).

Poniatowska, A., Michalecka, M. & Puławska, J. Phylogenetic relationships and genetic diversity of Monilinia spp. Isolated in Poland based on housekeeping-and pathogenicity‐related gene sequence analysis. Plant. Pathol. 70, 1640–1650. https://doi.org/10.1111/ppa.13401 (2021).

Zhu, X. Q., Niu, C. W., Chen, X. Y. & Guo, L. Y. Monilinia species associated with brown rot of cultivated Apple and Pear fruit in China. Plant Dis. 100, 2240–2250. https://doi.org/10.1094/PDIS-03-16-0325-RE (2016).

Silan, E. & Ozkilinc, H. Phylogenetic divergences in brown rot fungal pathogens of Monilinia species from a worldwide collection: inferences based on the nuclear versus mitochondrial genes. BMC Ecol. Evol. 22, 119. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12862-022-02079-6 (2022).

Côté, M. J., Tardif, M. C. & Meldrum, A. J. Identification of Monilinia fructigena, M. fructicola, M. laxa, and Monilia Polystroma on inoculated and naturally infected fruit using multiplex PCR. Plant Dis. 88, 1219–1225. https://doi.org/10.1094/PDIS.2004.88.11.1219 (2004).

Morrow, C. A. & Fraser, J. A. Sexual reproduction and dimorphism in the pathogenic basidiomycetes. FEMS Yeast Res. 9, 161–177. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1567-1364.2008.00475.x (2009).

Debuchy, R. & Turgeon, B. G. Mating-type structure, evolution, and function in Euascomycetes. In Growth, Differentiation and Sexuality (eds Kües, U. & Fischer, R.) 293–323 (Springer, 2006).

Wilson, A. M., Coetzee, M. P., Wingfield, M. J. & Wingfield, B. D. Needles in fungal haystacks: discovery of a putative a-factor pheromone and a unique mating strategy in the leotiomycetes. Plos One. 18, e0292619. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0292619 (2023).

Bakhshi, M., Zare, R. & Ershad, D. A detailed account on the statistics of the fungi and fungus-like taxa of Iran. Mycol. Iran. 9, 1–96. https://doi.org/10.22092/MI.2023.360819.1244 (2022).

Ershad, D. Fungi and fungal analogues of Iran. pp 695 (Ministry of Agriculture, Agricultural Research, Education and Extension Organization, Iranian Research Institute of Plant Protection, 2022).

Obi, V. I., Barriuso, J. J. & Gogorcena, Y. Peach brown rot: still in search of an ideal management option. Agriculture 8, 125. https://www.mdpi.com/2077-0472/8/8/125# (2018).

Rungjindamai, N., Jeffries, P. & Xu, X. M. Epidemiology and management of brown rot on stone fruit caused by Monilinia Laxa. Eur. J. Plant Pathol. 140, 1–17. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10658-014-0452-3 (2014).

Möller, E., Bahnweg, G., Sandermann, H. & Geiger, H. A simple and efficient protocol for isolation of high molecular weight DNA from filamentous fungi, fruit bodies, and infected plant tissues. Nucleic Acids Res. 20, 6115. https://doi.org/10.1093/nar/20.22.6115 (1992).

White, T. J., Bruns, T., Lee, S. & Taylor, J. In PCR protocols: A guide to methods and applications. In M.A. Innis, D. H. Gelfand, J.J. Sninsky & T.J. White (eds.) Ch. Amplification and direct sequencing of fungal ribosomal RNA genes for phylogenetics. 315–322 (Academic, USA, 1990).

Golmohammadi, H., Arzanlou, M. & Rabbani Nasab, H. Neofusicoccum parvum associated with pomegranate branch canker in Iran. Forest Pathol. 50, e12582. https://doi.org/10.1111/efp.12582 (2020).

Kumar, S., Stecher, G. & Tamura, K. MEGA7: molecular evolutionary genetics analysis version 7.0 for bigger datasets. Mol. Biol. Evol. 33, 1870–1874. https://doi.org/10.1093/molbev/msw054 (2016).

Katoh, K. & Standley, D. M. MAFFT multiple sequence alignment software version 7: improvements in performance and usability. Mol. Biol. Evol. 30, 772–780. https://doi.org/10.1093/molbev/mst010 (2013).

Ronquist, F. & Huelsenbeck, J. P. MrBayes 3: bayesian phylogenetic inference under mixed models. Bioinformatics 19, 1572–1574. https://doi.org/10.1093/bioinformatics/btg180 (2003).

Nylander, J. A. A. MrModeltest v. 2. Program distributed by the author. Uppsala: Evolutionary Biology Centre, Uppsala University (2004).

Swofford, D. L. PAUP^* Phylogenetic Analysis Using Parsimony (^* and Other Methods). Version 4. http://paup.csit.fsu.edu/ (2003).

Rambaut, A. FigTree, Version 1.4.3. (accessed 1 July 2016). http://tree.bio.ed.ac.uk/software/figtree/.

Bakhshi, M., Zare, R. Development of new primers based on gapdh gene for Cercospora species and new host and fungus records for Iran. Mycol. Iran. 7, 63–82. https://doi.org/10.22092/mi.2020.122549 (2020).

Kibbe, W. A. OligoCalc: an online oligonucleotide properties calculator. Nucleic Acids Res. 35, W43–W46. https://doi.org/10.1093/nar/gkm234 (2007).

Acknowledgements

We express our gratitude to the Research Deputy at the University of Tabriz for their financial support. We also would like to thank the Iran National Science Foundation, for financial support by a grant number (No. 68887079). The first author was awarded a grant (for PhD thesis) by the “Iranian Mycological Society”, which we kindly acknowledge. Additionally, we extend our sincere gratitude to the Deputy of Research and Technology at the Agricultural Research, Education, and Extension Organization of Iran (AREEO) for their generous support.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

H.G. conducted the sampling, culturing, and purification procedures, performed all laboratory experiments and analyses, and prepared the original draft of the manuscript. M.A., M.B and H.J. contributed to the conceptualization of the study, experimental design, and acquisition of funding. M.B. coordinated the project, verified the results, and oversaw the overall execution. All authors reviewed and approved the final version of the manuscript.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher’s note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if you modified the licensed material. You do not have permission under this licence to share adapted material derived from this article or parts of it. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Golmohammadi, H., Arzanlou, M., Jafary, H. et al. Polyphasic characterization and mating type allele distribution of Monilinia laxa in Iranian stone fruit orchards. Sci Rep 15, 29336 (2025). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-15129-y

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-15129-y