Abstract

Ocean acidification (OA) is a major threat to the sexual recruitment of reef-building corals. Acclimation mechanisms are critical but poorly understood in reef-building corals to OA during early life stages. Here, Acropora gemmifera, a common Indo-Pacific coral cultured in in situ seawater from Luhuitou reef at three levels of pCO2 (pH 8.14, 7.83, 7.54), showed significantly delayed larval metamorphosis and juvenile growth, but adapted to long-term high pCO2. Differentially expressed genes (DEGs) emerged as a time- and dose-dependent mode of short-term response (3 days post settlement, d p.s.) and long-term acclimation (40 d p.s.), with more DEGs responding to high pCO2 (pH 7.54) than to medium pCO2 (pH 7.83). High pCO2, a presumed threatening seawater baseline for A. gemmifera juveniles, activated DNA repair, macroautophagy, microautophagy and mitophagy mechanisms to maintain cellular homeostasis, recycle cytosolic proteins and damaged organelles, and scavenge reactive oxygen species (ROS) and H+, but at the cost of delayed development through cell cycle arrest associated with epigenetic and genetic regulation at 3 d p.s.. However, A.gemmifera juveniles acclimated to high pCO2 by up-regulating cell cycle, transcription, translation, cell proliferation, cell-extracellular matrix, cell adhesion, cell communication, signal transduction, transport, binding, Symbiodiniaceae symbiosis, development and calcification from 3 d p.s. to 40 d p.s., when energy reallocation and metabolic suppression occurred for high demand but short-term energy limitation in coral cells undergoing flexible symbiosis. All results indicate that acclimation mechanisms of complicated gene expression improve larval and juvenile resilience to OA for coral population recovery and reef restoration.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Coral reefs are among the most productive and diverse marine ecosystems, of which reef-building corals are the foundation species1,2. However, rising partial pressure of atmospheric carbon dioxide (pCO2) has caused ocean acidification (OA), which lowers seawater pH and carbonate saturation levels, severely threatening reef-building corals and reef ecosystems3,4,5, leading to reef erosion and ecological shifts3,6. The persistence, resilience and recovery of coral populations for reef restoration depends on sexual reproduction and recruitment of reef-building corals7,8,9. Nevertheless, early life stages of reef-building corals are acutely vulnerable to ongoing and expected OA10,11, which affects larval development and settlement12,13, juvenile growth and survival10,14, resulting in impaired recruitment and population and/or community dynamics5,15.

As early life stages are critical for rebuilding populations, there has been interest in the effects of OA on coral recruitment, coral response and their potential for acclimatization and/or resilience to OA9,16,17. Specifically, the physiological response, cellular processes, and molecular mechanisms by which corals cope with OA will benefit their plasticity18,19,20. To survive and grow under environmental change, reef-building corals have evolved mechanisms in gene expression20,21, autophagy22,23, epigenetics24,25, metabolism13,14 and symbiosis26,27. The effects of OA on early life stages of reef-building corals have been recently documented, but the mechanisms of coral response and/or acclimation to OA involving gene expression are still in their infancy.

Acropora corals, with simultaneous mass spawning of multicongeneric species and horizontal symbiosis of Symbiodiniaceae, dominate Indo-Pacific reefs28,29. As a common species, A. gemmifera on Luhuitou reef, northwestern South China Sea, showed tolerance to OA, which negatively affected A.gemmifera development, but not survival30 and Symbiodiniaceae symbiosis26. Yet mechanisms by which A.gemmifera copes with OA are unclear. Therefore, we assume that A.gemmifera larvae and juveniles will be affected by acute high pCO2 in terms of development and growth, while surviving corals will have the potential to acclimate to long-term high pCO2 by regulating gene expression.

To elucidate how reef-building corals respond and/or resist to OA, three levels of pCO2 (350.06 ± 30.67, 818.93 ± 76.09, 1694.92 ± 105.77 μatm) were used to mimic OA in ambient seawater to culture A.gemmifera larvae and juveniles. Developmental states and growth were recorded and gene expression were compared between corals in the three treatments at 3 days post-settlement (d p.s.) (short-term) and 40 d p.s. (long-term). Differentially expressed genes (DEGs) and their functional enrichment by Gene Ontology (GO) and Kyoto Encyclopedia of Genes and Genomes (KEGG) may reveal regulatory mechanisms of short-term response and long-term acclimation of A.gemmifera to high pCO2. Cellular and molecular mechanisms that enhance OA tolerance in A.gemmifera during early life stages could benefit efforts to recover coral populations for reef restoration through the sexual recruitment of reef-building corals.

Materials and methods

Coral larvae

Six colonies of gravid A. gemmifera (~ 40 cm diameter) were collected at 3–5 m depth (sampling site interval > 10 m) on Luhuitou reef (18° 12’ N, 109° 28’ E), Sanya Bay, China, and maintained on the reef flat near the Tropical Marine Biological Research Station in Hainan until they spawned naturally on 30 April 2015 (- 2 days around the full moon). The corals were then returned to their original location. Egg-sperm bundles from each of the two colonies were mixed in an aquarium containing 90 L of 0.5 micron filtered in situ seawater from ~ 5 m depth on Luhuitou reef for cross-fertilization. Larvae from these aquariums were transferred to the experimental in situ seawater (Fig. 1a).

The experimental design.(a) OA treatment of flow-through in situ seawater and experimental system. Ambient seawater at ~ 5 m depth from Luhuitou reef was pumped, sand-filtered and treated with three pCO2 levels (350.06, 818.93, 1694.92 μatm) in 2000 L tanks for the culture of A.gemmifera larvae and juveniles in every six 90 L aquariums (n = 3 at 3 d p.s. and 40 d p.s.).(b) Morphological characteristics (larva, flattened larvae, new recruits with 12 tentacles and 6 mesenteries, juvenile with synapticular ring 1, 2, 3, 4 and 5, respectively, juvenile with three corallites), and sampling time of A. gemmifera under high pCO2 (pH 7.54) at 2 days of settlement, 3 and 40 d p.s..

OA experiment and sampling

The OA experiment was designed and conducted as previously described26,30 to mimic current pCO2 levels, levels at the end of this century, and levels twice as high at the end of this century (IPCC 2014). Briefly, sand-filtered in situ seawater was equilibrated in three 2000-L tanks with continuous and direct bubbling of pure CO2 for three adjusted pH values (8.14 ± 0.03, 7.83 ± 0.04, 7.54 ± 0.03) using high-precision pressure gauges and valves (DC01-01, Dici, China) and a pH controller (pH2010, Weipro, China) (Table S1-1). Seawater from each tank was flowed into 6 aquariums (90 L/aquarium, three replicates at 3 and 40 d p.s., respectively) at a rate of 60 ml per minute for larval rearing (~ 1 larvae per milliliter of seawater) under a light–dark cycle of ~ 250 µmol photons photons per square meter per second, 12 h :12 h (Fig. 1a).

Pre-conditioned terracotta tiles grown with biofilm on Luhuitou reef for two weeks were placed in experimental aquariums for four-day-old larvae to settle and then grow for 42 days. To compare the development and growth of A.gemmifera larvae and juveniles in three treatment, 50 individuals per aquarium were randomly photographed using a stereomicroscope for 4 weeks when synapticular ring 4 and synapticular ring 5 were observed in all corals under the high pCO2 treatment. Morphological characteristics were observed and diameter was measured using ToupView 3.7 software. Coral diameter were expressed as mean ± standard deviation (SD) of three replicate aquariums. To identify the effects of pCO2 and/or time on coral physiology, Tukey’s HSD multiple comparisons in SPSS (v26.0) software were performed as post hoc tests when one-way analysis of variance (ANOVA) with p < 0.05 detected significant differences in developmental state and/or diameter.

Additionally, new recruits with 12 tentacles (2 days of settlement) were sampled from the control (pH 8.14) for reference transcriptome sequencing. Corals for 18 gene expression profiles (n = 3 per treatment at pH 8.14, pH 7.83 and pH 7.54, respectively) were collected at 3 d p.s. (corresponding diameter: 1275.66 ± 117.36 μm, 1229.61 ± 125.66 μm, 1166 ± 128.13 μm) and 40 d p.s. (1371.16 ± 72.79 μm, 1311.78 ± 86.64 μm, 1247.13 ± 78.76 μm) (Fig. 1b). All primary polyps (~ 80 individuals per sample, three replicates) were removed from the tiles using a sterile scalpel, immediately pooled in Trizol reagent (Life Technologies), snap frozen and stored in liquid nitrogen.

RNA extraction and sequencing

Total RNA was extracted from all samples using Trizol reagent according to the manufacturer’s instructions. A NanoPhotometer spectrophotometer (Implen, CA, USA) and an Agilent 2100 Bioanalyzer (Agilent Technologies, CA, USA) were used to evaluated RNA quantity and quality, respectively. Oligo-dT-attached magnetic beads were used to purify poly-A-containing total mRNA (> 1.00 μg / sample; RNA integrity number, RIN > 4.50), which was fragmented into small pieces using divalent cations at elevated temperatures in First Strand Synthesis Reaction Buffer (5 ×). First-strand cDNA was synthesized using random hexamer primers and M-MuL V reverse transcriptase (NEB, USA). The cleaved RNA fragments were used as templates to synthesize double-stranded cDNA, which underwent end repair, a single ‘A’ base addition, and ligation to Illumina adapters. After purification using the AMPure XP system (Beckman Coulter, Beverly, USA), the products were used together with Phusion High-Fidelity DNA Polymerase, Universal PCR primers, and Index (X) primers (NEB, USA) to amplify the transcriptome cDNA libraries, which were sequenced on the Illumina Hiseq 2000 platform (Beijing Genomics Institute, Shenzhen, China).

For the 18 gene expression profiles, the library was prepared using an Illumina Gene Expression Sample Prep Kit and Solexa Sequencing Chip (Illumina, USA) according to the manufacturer’s protocols, with the primary instrumentation consisting of an Illumina Cluster Station and an Illumina HiSeq 2000 System. After a series of sequencing, image analysis, base calling, raw tag generation and tag counting processes, all raw data in fast format was processed using Trimmomatic (v0.39)31 to remove the duplicate, low quality and/or poly-N reads and adapter sequences and to generate the clean reads.

Data analysis

Trinity (v2.8.5)32 was used to de novo assemble the clean reads into transcripts, with min_kmer_cov set to 2 by default and all other parameters set to default. Redundant transcripts were identified and removed using TGICL (v2.1) (https://sourceforge.net/projects/tgicl/files/tgicl%20v2.1/). Sequence annotation was then performed using the Blastx33 against the NCBI non-redundant (Nr), Swiss-Prot, and Pfam databases (E-value < 1e-5). Transcripts with the best possible match to a known protein were identified as unigenes (http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/UniGene/), which mapped to Acropora species34 were identified as A.gemmifera. Unigenes were functionally annotated using the Blast2GO (https://www.blast2go.com/blast2go-pro/download-b2g) and the KEGG database35.

18 gene expression profiles were analyzed based on reported methods36,37. Briefly, clean reads were mapped to the reference transcriptome using SOAP (v2.21) (http://soap.genomics.org.cn/), with mismatches ≤ 1 bp. The read count of each unigene was obtained, corrected and expressed as fragments per kilobase per million mapped reads (FPKM) using bowtie238. To explore the main effects of pCO2 and time, gene expressions (FPKM, false discovery rate < 0.01) of A.gemmifera larvae and juveniles regarding organismal and cellular response variables were performed with a general linear model, where pCO2 and days were treated as fixed factors, implemented in the stats of the R package.

DEGs were identified using the DESeq2 (v1.20.0)39 with thresholds of absolute log2 fold change ≥ 1 and p-value < 0.05. The p-value was also adjusted using the Benjamini and Hochberg approach to control for false discovery rate. DEGs were separately subjected to GO enrichment using the GOseq R package (v1.10.0)40 and KEGG enrichment using KOBAS software (v2.0.12)41. Based on down/upregulated DEGs, functional GO or KEGG enrichment was considered statistically significant at p < 0.05.

Results

Development and growth of A.gemmifera acclimated to OA during early life stages

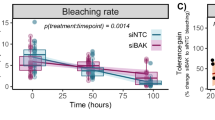

A.gemmifera larvae and juveniles gradually progressed through 8 developmental states of flattened larvae, 6 mesenteries, 12 tentacles, synapticular ring 1, synapticular ring 2, synapticular ring 3, synapticular ring 4, synapticular ring 5 until corallites appeared at 40 d p.s. (Fig. 1b, Table S1-2). Larvae in the control and medium pCO2 took 2 days to complete settlement and metamorphosis (flattened larvae 4.67% and 6.00% at 1 day, 6 mesenteries 6.67% and 9.33% at 2 days), while those in high pCO2 took 3 days (flattened larvae 2.67% at 2 days, 6 mesenteries 8.67% at 3 days). There were 85.33% and 80.00% of new recruits with 12 tentacles in the control and medium pCO2 groups at 2 days, 90.00% in the high pCO2 group at 3 days. Juveniles in high pCO2 also took longer than those in control and/or medium pCO2 to pass through the developmental states of synapticular ring 1 (2–6 days), synapticular ring 2 (3–13 days) and synapticular ring 3 (4–24 days). A.gemmifera in the control developed to synapticular ring 4 and 5 with stable percentage and diameter at 8 days, while those in medium and high pCO2 were at 17 and 26 days (Fig. 2a, Tables S1-2, S1-3).

High pCO2 also significantly (p < 0.001) delayed the metamorphosis and polyp growth of A.gemmifera (Fig. 2b and S1, Tables S1-2, S1-3). Although the mean diameter of A.gemmifera in the high pCO2 was significantly lower in the states of flattened larvae (Fig. 2b and S1a), 6 mesenteries (Fig. 2b and S1b) and 12 tentacles (Fig. 2b and S1c) than in the control and/or medium pCO2, it is similar in synapticular ring 1 (Fig. 2b and S1d), after which (synapticular ring 2, 3, 4 and 5) the diameter differed significantly (p < 0.001) in three pCO2 levels (Fig. 2b). Coral diameter in synapticular ring 2 of each treatment did not increase significantly after 3 days (Fig. S1e). The same was true for synapticular ring 3 at 4, 6, and 8 days in the control, medium and high pCO2 groups (Fig. S1f.), synapticular ring 4 at 8, 21 and 21 days , and synapticular ring 5 at 9, 15 and 21 days (Fig. S1g). Combined with percentages of developmental states, the mean diameter at all time points (1–28 days) in the control, medium and high pCO2 groups did not significantly increase after 8 (1349.15 ± 78.46 μm), 11 (1287.91 ± 96.57 μm), and 17 (1231.63 ± 97.40 μm) days, respectively (Tables S1-2, S1-3).

Data analysis of reference transcriptome and 18 gene expression profiles

The transcriptome with 64,556 assembled transcripts contained 50,097 unigenes (Table S1-4), of which 36,746 unigenes (56.92%) were annotated and assigned to cnidarians (Fig. 3a). A total of 19,096 and 8,110 unigenes were annotated in GO terms (Table S1-5) and KEGG pathways (Table S1-6), respectively. The total mapped reads of the 18 gene expression profiles were 42.76%—67.06% of the reference transcriptome (Table S1-7). Gene expression of A. gemmifera juveniles in response to OA showed a time-dependent mode, as 10,169 unigenes (20.30%) were significantly related to days, while 67 unigenes (0.13%) were related to OA and days (Fig. 3b, Tables S1-8, S1-9).

Annotation of the transcriptomic unigenes and statistics of DEGs between groups of A.gemmifera juveniles in response to CO2-mediated OA. (a) Number and percentage of the transcriptomic unigenes annotated in the Nr database. (b) Number of unigenes specifically associated with OA and days. (c) Significantly up- or down-regulated DEGs between groups. (d) Venn diagrams of DEGs between groups.

Activation of DEGs in a dose-dependent mode

Compared to the control (pH 8.14), high pCO2 (pH 7.54) activated more DEGs (3,293) than medium pCO2 (pH 7.83) (811) at 3 d p.s., whereas the difference decreased at 40 d p.s. (1,716 and 1,074) (Fig. 3c, Tables S2-1, S2-2). DEGs of the same treatment were similar in number from 3 d p.s. to 40 d p.s., with far more DEGs overlapping (1,731) than at 3 d p.s. (36) or 40 d p.s. (28) (Fig. 3d, Table S2-2). High pCO2 significantly activated the repair and acclimation mechanisms of A.gemmifera juveniles, particularly those related to autophagy, cell cycle, cell proliferation and development, cell adhesion, and epigenetic and genetic regulation. Given the above developmental and growth characteristics, the DEGs, GO and KEGG analyses focused on high pCO2 at 3 d p.s., 40 d p.s. and from 3 d p.s. to 40 d p.s. (Tables S2-2—S3-2).

Scavenging damage for cellular homeostasis in juveniles exposed to high pCO2

For superoxide radical and hydrogen peroxide (H2O2) metabolism, A.gemmifera juveniles up-regulated peroxisomal membrane protein and ROS-scavenging enzymes, including superoxide dismutase, catalase, glutathione peroxidase and NADH dehydrogenase, at 3 d p.s.. p53 and DNA damage-regulated protein was expressed at 40 d p.s., although ROS-generating enzymes were up-regulated in nitric oxide synthase but down-regulated in D-aspartate oxidase and xanthine dehydrogenase/oxidase from 3 d p.s. to 40 d p.s. (Fig. 4a, 4e, Table S2-2). Carbonic anhydrase (CA), which catalyzes CO2 and H2O to H+ and HCO3- for photosynthesis and/or calcification in coral cells, was up-regulated at 3 d p.s. and down-regulated from 3 d p.s. to 40 d p.s. (Fig. 4a, 4e, Table S2-2), resulting in increased and decreased hydrogen ion transmembrane transport (GO:1,902,600), respectively (Table S3-1). Accordingly, ROS could be produced persistently in Symbiodiniaceae and the nucleus, cytoplasm and mitochondria of coral cells, where H+ would accumulate in the absence of Symbiodiniaceae (Fig. 4a).

A.gemmifera juveniles in response to high pCO2. (a) Dissolved inorganic carbon (CO2, HCO3-, CO32+) uptake, ROS (H2O2, O2∙-) production and/or H+ accumulation in coral cells under high pCO2. For calcification (CaCO3), calicoblastic cells concentrate diffused CO2, actively transport (orange hexagon) HCO3- following CO2 hydration by carbonic anhydrase (CA), and Ca2+ into the extracellular calcifying medium. For photosynthesis, CO2 and/or HCO3- is delivered to the coral cell containing the symbiotic Symbiodiniaceae in the oral endoderm. With increasing pCO2 in seawater, there is a shift in the carbonate chemical equilibrium, leading to an accumulation of internal H+ in the cells in the absence of photosynthesis, ROS production of H2O2 and/or O2∙-from mitochondria and/or Symbiodiniaceae in host cells. (b) Schematic response in the coral nucleus to OA stress. (c) Autophagy-lysosomal pathways of macroautophagy, microautophagy and mitophagy fusing with lysosome and/or endosome in coral cell. (d) Molecular mechanism of the delayed cell cycle in coral cells at 3 d p.s.. Mitosis phase is divided into prophase, prometaphase, metaphase, anaphase, and telophase. The encircled P’s indicate phosphorylation. (e) Tables from left to right show the up-regulated (red), down-regulated (green), and/or up- and down-regulated (yellow) DEGs (Table S2-2), with expression variation of log2 fold change involved in (a), (c) and (d), respectively.

High pCO2 did not induce acidosis and bleaching (Fig. 1b) appears to be related to repair and autophagy mechanisms activated in A.gemmifera juveniles for homeostasis. Coral cells recruited a provisional cell cycle arrest against DNA damage by ROS production and/or H+ accumulation in the nucleus, where base-excision repair, mismatch repair, nucleotide-excision repair and double-strand break repair functioned at 3 d p.s. for recovery by up-regulated DNA helicase and repair protein from 3 d p.s. to 40 d p.s. (Fig. 4b, Tables 1, S2-3 and S3-1).

Autophagy for cellular homeostasis of juveniles exposed to high pCO2

To maintain cellular homeostasis, macroautophagy, mitophagy and microautophagy were activated in A.gemmifera juveniles to recycle cytosolic proteins and damaged organelles. DEGs associated with autophagy were up-regulated in autophagosome, mitochondrion, endoplasmic reticulum, Golgi membrane, and exosome, but down-regulated in endosome, Golgi apparatus, exocytosis and endocytosis at 3 d p.s., and recovered from 3 d p.s. to 40 d p.s.(Tables S2-3 and S3-1). Notably, autophagosome, fusion, vesicle and mediated transport were up-regulated at 40 d p.s. (Fig. 4b, c, Tables S3-1 and S3-2).

Macroautophagy was initiated by inhibition of the target of rapamycin (mTOR) to activate the serine/threonine protein kinase ATG1 and autophagy-related protein 101 (ATG 101) (Fig. 4c, e). Up-regulated endoplasmic reticulum membrane, Golgi membrane and associated transport increased pre-autophagosomal structure and autophagosome assembly at 3 d p.s. (Table S3-1). Phosphoinositide 3-kinase regulatory subunit 4-like (VPS15) was up-regulated from 3 d p.s. to 40 d p.s. to induce nucleation. Cytosolic proteins and damaged organelles were then engulfed by phagophore elongation mediated by the ubiquitin-like-conjugating enzyme ATG10 and the ubiquitin-like modifier-activating enzyme ATG7, which were recruited to the autophagosome membrane for maturation along with the gamma-aminobutyric acid receptor-associated protein LC3/ATG8 (Fig. 4c and S2a, Tables S2-2, S2-4 and S3-2). Up-regulated Ras-related protein Rab7 together with LC3/ATG8 facilitated transport and fusion of autophagosome and/or endosome with lysosome and/or vesicle in a SNARE-dependent manner (Fig. S2b, S2c, Tables S2-4 and S3-2) for degradation of cargoes by hydrolase (Fig. 4c, Tables S2-3 and S3-1).

Macroautophagy crosstalk with the endosome from endocytosis (Fig. 4c, S2e and S2f., Tables S2-4 and S3-2) significantly increased extracellular exosome in exocytosis of either hybrid-vesicle amphisomes by late endosome by Ras-related protein Rab11 down-regulated at 3 d p.s.. Mitophagy, a selective macroautophagy, was recruited to recycle of damaged and depolarized mitochondria via LC3/ATG8 and ATG7 from 3 d p.s. to 40 d p.s. (Fig. 4c and S2d, Tables S2-2, S3-1 and S3-2).

Microautophagy, the direct uptake of cytosolic material into lysosomes through the lysosomal lumen or vacuole membrane, was inhibited from 3 d p.s. to 40 d p.s. according to the down-regulated lysosome-associated membrane protein 1/2 (LAMP1_2). However, the up-regulated ATG7 mediated piecemeal microautophagy of nucleus at 3 d p.s. (Fig. 4c, e, Tables S2-2, S2-3 and S3-1).

Cell cycle arrest in juveniles exposed to high pCO2

Four phases of the cell cycle, Gap 1 (G1), Synthesis (S), Gap 2 (G2) and Mitosis (M), were regulated by specific cyclin/cyclin-dependent kinase complexes and three major checkpoints (G1/S, G2/M, spindle assembly checkpoint (SAC)) in A.gemmifera juveniles under high pCO2 (Fig. 4d and S3a, Tables S2-3, S2-4 and S3-1). At 3 d p.s., the interphase G1 was arrested by the down-regulation of histone acetyltransferase (HAT) and the up-regulation of histone deacetylase (HDAC), resulting in reduced transcription and a quiescent state during Gap0 (G0). Reduced histone acetylation and increased histone deacetylation delayed cellular contents duplication in Gap1, chromosome duplication (DNA replication factor Cdt1 and cyclin E) in Synthesis, preparation for division (cyclin A) in Gap2 and separation and reorganization (cell division cycle protein 20 (CDC20)) in Mitosis (Fig. 4d, e). During the metaphase-to-anaphase transition, the anaphase promoting complex/cyclosome (APC/C) was up-regulated at 3 d p.s. but repressed by the mitotic spindle assembly checkpoint protein MAD2B from 3 d p.s. to 40 d p.s., when the down-regulated mitotic checkpoint serine/threonine-protein kinase BUB1 beta activated mitosis and up-regulated cyclin D and DNA replication re-entered the cell cycle from quiescent cells (Fig. 4d, Tables S2-3 and S3-1).

At 3 d p.s., transcription, RNA transport (Fig.S3c), protein modification and localization were down-regulated, whereas spliceosome (Fig. S3b), ribosome (Fig. S3d), translation, and protein processing in endoplasmic reticulum (Fig. S3e) were significantly up-regulated (Tables S2-3, S2-4, S3-1 and S3-2). GO terms that significantly enriched down-regulated DEGs reflected the reduction of cellular content duplication, including hereditary constitution (nucleoplasm, nucleus, nuclear envelope and speck), cytoskeleton (microtubule, actin, cytoskeleton, cilium, kinesin complex and their binding, organization and assembly), and membrane system (cytoplasm, cytosol, membrane, plasma membrane, cell cortex, vesicle, channel complex, membranes and peroxisome) (Table S3-1). The cell cycle was also arrested by down-regulation of DNA-binding, chromosome, kinetochore, centrosome, centriole, spindle and cell division (midbody and cytokinesis) at 3 d p.s. (Fig. 4d) but acclimated at 40 d p.s. (Tables S2-3 and S3-1).

Epigenetic regulation and development delay in juveniles exposed to high pCO2

Methyltransferase, demethylase and methylosome protein associated with DNA or histone methylation, methylosome, methyltransferase activity, genetic imprinting, and chromatin silencing, binding, remodeling and organization were activated in A.gemmifera juveniles at 3 d p.s. by high pCO2 but not by medium pCO2 (Tables S2-2, S2-3 and S3-1). Top 10 GO enrichment involved these epigenetic regulations (3 d p.s. pH 7.54 vs 3 d p.s. pH 7.83) (Fig. S4). The cell cycle, in cooperation with epigenetic regulators, orchestrated the cell fate and development as cell differentiation, migration, proliferation, multicellular organismal development, and enzyme activities were significantly down-regulated at 3 d p.s. but up-regulated from 3 d p.s. to 40 d p.s. in A.gemmifera juveniles (Tables S2-3 and S3-1).

To respond to high pCO2 and enhance cell interaction, A.gemmifera juveniles adopted an up-regulated strategy (significantly down-regulated at 3 d p.s., but up-regulated from 3 d p.s. to 40 d p.s.) in cell-extracellular matrix, cell adhesion, signal transduction and transport. Cell-extracellular matrix included extracellular region, extracellular space, extracellular matrix, collagen and their binding (Table S3-1). Cell adhesion included cell junction, cell adhesion, focal adhesion, cell–cell adhesion, cell–matrix adhesion, cell-substrate adhesion, ECM-receptor interaction, cell adhesion molecules, hemidesmosome and their assembly (Tables S3-1 and S3-2). Signal transduction involved Notch signaling pathway, Wnt signaling pathways, small GTPase mediated signal transduction, various receptor signaling pathways and receptor activity (Tables S3-1 and S3-2). Ion homeostasis of calcium, metal, iron, magnesium, zinc and potassium, and ion binding and transport were negatively affected at 3 d p.s., but transport of ions and substances was up-regulated from 3 d p.s. to 40 d p.s., when coral calcification was delayed by significantly down-regulated skeletal organic matrix protein, secreted acidic protein, acidic skeletal organic matrix protein (Tables 1 and S3-1).

Enhanced coral-symbiodiniaceae symbiosis in juveniles exposed to high pCO2

Phagosome (ko04145) was significantly down-regulated in A.gemmifera juveniles at 40 d p.s., whereas endocytosis (GO:0006897) and exocytosis (GO:0006887) were up-regulated from 3 d p.s. to 40 d p.s. (Tables S3-1 and S3-2). High pCO2 activated DEGs on the cell membrane involved in the coral-Symbiodiniaceae symbiosis. Ficolin and pattern recognition receptors such as lectins, toll-like receptor, scavenger receptors, complement were significantly up-regulated at 3 d p.s. or from 3 d p.s. to 40 d p.s. (Table 1).

Energy reallocation and metabolic suppression in juveniles exposed to high pCO2

Cellular processes and molecular regulation were energy consuming in A.gemmifera juveniles under high pCO2. ATP was supposed to produce in mitochondria as mitochondrion, mitochondrial inner membrane, mitochondrial matrix, mitochondrial intermembrane space, mitochondrial outer membrane, mitochondrial respiratory chain complex IV (Table S3-1) and oxidative phosphorylation were significantly up-regulated at 3 d p.s. but down-regulated at 40 d p.s.(Fig S3f., Tables S2-4 and S3-2). Metabolism and/or catabolism of carbohydrate, small molecule, lipid, fatty acid, oxidation–reduction, glycerophospholipid, arachidonic acid, gluconeogenesis, phospholipid, amino acid and/or protein also used a down-regulated strategy (up-regulated at 3 d p.s. but suppressed from 3 d p.s. to 40 d p.s.), although the feeding behavior for energy reallocation was opposite (Tables S2-3, S3-1 and S3-2). Metabolic suppression reflected by down-regulated ATP binding, phosphatase binding, phospholipid binding and ATPase activity at 3 d p.s., and metabolic, catabolic, biosynthetic processes and enzyme activities from 3 d p.s. to 40 d p.s. (Table S3-1).

Discussion

OA negative affected A.gemmifera larval metamorphosis, settlement and juvenile growth. This is similar to other reef-building corals10,13. All surviving A.gemmifera completed the 8 developmental states, of which flattened larvae with smaller diameter under high pCO2 developed to synapticular ring 1, with no significant difference in diameter between the three pCO2 treatments. Moreover, there was no significant increase in the diameter of any and/or all developmental states at certain time points. Combined with the similar survivorship30, A. gemmifera originated from Luhuitou reef is resistant and adapted to long-term exposure to high pCO2 from larvae to juveniles. Long-living trans-generation coral larvae show the potential for acclimatization and adaptation to OA42.

Reef-building corals are supposed to produce ROS and/or accumulated H+ due to OA, leading to cellular and molecular regulation at the endoplasmic reticulum, mitochondrion, membrane system, and/or symbiotic Symbiodiniaceae19,43. In addition to repair and autophagy mechanisms to maintain homeostasis, A.gemmifera juveniles activated peroxisomal membrane protein, scavenging enzymes to remove ROS and/or H+ at 3 d p.s.. Given the gradual changes in developmental state from flattened larvae to synapticular ring 4 during 1–5 days exposure to high pCO2, the short-term response of juveniles at 3 d p.s. appears to involve DEGs in both development and activation of cellular mechanisms. Consistently, high pCO2 activated far more DEGs than medium pCO2 in A.gemmifera juveniles with a time-dependent mode, reflecting coral acclimatization to pH fluctuations44 and dose dependence45.

Cell cycle control in the face of damage in eukaryotes46,47, including DNA repair, cell cycle arrest and autophagy, was significantly regulated in A.gemmifera juveniles to high pCO2. Cell cycle arrest was regulated by specific genes associated with histone acetylation, which affects transcription48 and epigenetics49. In reef-building corals, OA influence DNA and histone methylation and phenotypic plasticity for adaptation9,25. A.gemmifera juveniles activated epigenetics and DNA repair, driving chromatin remodeling by methyltransferases and maintaining DNA integrity by DNA helicases50,51.

Unlike thermally induced autophagy in reef-building corals22,23,43, macroautophagy, microautophagy and mitophagy were activated under high pCO2 but not under control or medium pCO2 in A.gemmifera juveniles, which differ from adults in inducing apoptosis but not autophagy19. Piecemeal microautophagy of the nucleus required the core macroautophagy genes and facilitated nucleus homeostasis in corals. Crosstalk of endosome and/or phagosome with macroautophagy and lysosome contributes to cellular homeostasis52 and cargo sorting and release53. This crosstalk in A.gemmifera at 3 d p.s. appeared to promote the removal of ROS and/or H+ according to the up-regulated exosome but down-regulated exocytosis, which combined with the flexible symbiosis for Symbiodiniaceae proliferation26 and photosynthesis in juveniles42,54, in contrast to adults with reduced Symbiodiniaceae under OA stress19.

High pCO2 caused A.gemmifera to take longer to complete each developmental state, especially from synapticular ring 2 and 3 up to synapticular ring 4 and 5. Cell cycle arrest delayed cellular content duplication, chromosome, spindle and cell division in A.gemmifera juveniles under high pCO2 at 3 d p.s., as well as cytoskeleton and calcification like other corals19,20. However, A.gemmifera juveniles acclimated to long-term high pCO2 from 3 d p.s. to 40 d p.s. by improving cell-extracellular matrix, cell adhesion, cell communication and signal transduction, the bases for metazoan multicellularity and tissue development55,56,57, and up-regulating DNA replication, cell cycle, cell development and proliferation, and transport, similar to other corals18,19,20. The down-regulation of metal ion binding, especially calcium ion imbalance in corals under OA19, skeletal organic matrix protein, acidic skeletal organic matrix protein and galaxin20 are dedicated to the delayed calcification of A.gemmifera juveniles30.

Besides epigenetic regulation and gene expression, metabolism and energy reallocation also facilitate acclimation to OA stress in corals9,20. At 3 d p.s., A.gemmifera juveniles without symbiotic Symbiodiniaceae required massive energy to survive under high pCO2 from oxidative phosphorylation in mitocondria, metabolic process of carbohydrate, lipid or fatty acid, amino acid or protein and glycerol ether, and autophagy recycling of cytosolic proteins and damaged organelles. Therefore, metabolic suppression occurred from 3 d p.s. to 40 d p.s. when additional nutrients could be obtained from symbiotic cyanobacteria and/or Symbiodiniaceae26 and/or heterotrophy58,59. High demand but short-term energy limitation also acclimated by the impaired development and calcification30.

In conclusion, different levels of pCO2 activated DEGs in A.gemmifera juveniles in a time- and dose-dependent manner. High pCO2 appeared to be a threatening seawater baseline for A.gemmifera juveniles to activate DNA repair and autophagy mechanisms for cellular homeostasis, ROS and H+ scavenging, but at the cost of delayed development through cell cycle arrest associated with epigenetic and genetic regulation. However, A.gemmifera juveniles acclimated to long-term high pCO2 by up-regulating cell cycle, transcription, translation, cell proliferation, cell-extracellular matrix, cell adhesion, cell communication, signal transduction, transport, binding, symbiosis, development and calcification from 3 d p.s. to 40 d p.s., when energy reallocation and metabolic suppression occurred for high demand but short-term energy limitation. All results elucidate the complex acclimation mechanisms of reef-building corals that are resilient to high pCO2 during early life stages.

Data availability

RNA-seq reads of the reference transcriptome were submitted to the NCBI short Read Archive (BioProject PRJNA793713; Accession no. SRR17407354). RNA-seq reads of DEGs profiles were submitted to the NCBI Gene Expression Omnibus (GEO) database under accession number GSE96935.

References

Reaka-Kudla, M. L. Biodiversity II: Understanding and Protecting Our Biological Resources (Jeseph Henry Press, 1997).

Connell, J. H. Diversity in tropical rain forests and coral reefs. Science 199, 1302–1310. https://doi.org/10.1126/science.199.4335.1302 (1978).

Hoegh-Guldberg, O. et al. Coral reefs under rapid climatechange and ocean acidification. Science 318, 1737–1742. https://doi.org/10.1126/science.1152509 (2007).

Orr, J. C. et al. Anthropogenic ocean acidification over the twenty-first century and its impact on calcifying organisms. Nature 437, 681–686. https://doi.org/10.1038/nature04095 (2005).

Hill, T. S. & Hoogenboom, M. O. The indirect effects of ocean acidification on corals and coral communities. Coral Reefs 41, 1557–1583. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00338-022-02286-z (2022).

Hughes, T. P. et al. Coral reefs in the Anthropocene. Nature 546, 82–90. https://doi.org/10.1038/nature22901 (2017).

Randall, C. J. et al. Sexual production of corals for reef restoration in the Anthropocene. Mar. Ecol. Prog. Ser. 635, 203–232. https://doi.org/10.3354/meps13206 (2020).

Quigley, K. M., Hein, M. & Suggett, D. J. Translating the 10 golden rules of reforestation for coral reef restoration. Conserv. Biol. 36, e13890. https://doi.org/10.1111/cobi.13890 (2022).

Putnam, H. M. Avenues of reef-building coral acclimatization in response to rapid environmental change. J. Exp. Biol. 224, jeb239319. https://doi.org/10.1242/jeb.239319 (2021).

Carbonne, C. et al. Early life stages of a Mediterranean coral are vulnerable to ocean warming and acidification. Biogeosciences 19, 4767–4777. https://doi.org/10.5194/bg-19-4767-2022 (2022).

Albright, R. Reviewing the effects of ocean acidification on sexual reproduction and early life history stages of reef-building corals. J. Marine Sci. 2011, 473615. https://doi.org/10.1155/2011/473615 (2011).

Fabricius, K. E., Noonan, S. H. C., Abrego, D., Harrington, L. & De’ath, G. Low recruitment due to altered settlement substrata as primary constraint for coral communities under ocean acidification. Proc. R. Soc. B: Biol. Sci. 284, 20171536. https://doi.org/10.1098/rspb.2017.1536 (2017).

Nakamura, M., Ohki, S., Suzuki, A. & Sakai, K. Coral larvae under ocean acidification: survival, metabolism, and metamorphosis. PLoS ONE 6, e14521. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0014521 (2011).

Albright, R. & Langdon, C. Ocean acidification impacts multiple early life history processes of the Caribbean coral Porites astreoides. Glob. Change Biol. 17, 2478–2487. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1365-2486.2011.02404.x (2011).

Caroselli, E. et al. Low and variable pH decreases recruitment efficiency in populations of a temperate coral naturally present at a CO₂ vent. Limnol. Oceanogr. 64, 1059–1069 (2019).

Pitts, K. A., Campbell, J. E., Figueiredo, J. & Fogarty, N. D. Ocean acidification partially mitigates the negative effects of warming on the recruitment of the coral. Orbicella faveolata. Coral Reefs 39, 281–292. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00338-019-01888-4 (2020).

Edmunds, P. J. Coral recruitment: patterns and processes determining the dynamics of coral populations. Biol. Rev. 98, 1862–1886. https://doi.org/10.1111/brv.12987 (2023).

Barshis, D. J. et al. Genomic basis for coral resilience to climate change. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. 110, 1387–1392. https://doi.org/10.1073/pnas.1210224110 (2013).

Kaniewska, P. et al. Major cellular and physiological impacts of ocean acidification on a reef building coral. PLoS ONE 7, e34659. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0034659 (2012).

Moya, A. et al. Whole transcriptome analysis of the coral Acropora millepora reveals complex responses to CO₂-driven acidification during the initiation of calcification. Mol. Ecol. 21, 2440–2454. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1365-294X.2012.05554.x (2012).

Kenkel, C. D., Moya, A., Strahl, J., Humphrey, C. & Bay, L. K. Functional genomic analysis of corals from natural CO2 -seeps reveals core molecular responses involved in acclimatization to ocean acidification. Glob. Change Biol. 24, 158–171. https://doi.org/10.1111/gcb.13833 (2018).

Downs, C. A. et al. Symbiophagy as a cellular mechanism for coral bleaching. Autophagy 5, 211–216. https://doi.org/10.4161/auto.5.2.7405 (2009).

Camaya, A. P., Sekida, S. & Okuda, K. Changes in the ultrastructures of the coral Pocillopora damicornis after exposure to high temperature, ultraviolet and far-red radiation. Cytologia 81, 465–470. https://doi.org/10.1508/cytologia.81.465 (2016).

Chille, E. E. et al. Energetics, but not development, is impacted in coral embryos exposed to ocean acidification. J. Exp. Biol. https://doi.org/10.1242/jeb.243187 (2022).

Liew, Y. J. et al. Epigenome-associated phenotypic acclimatization to ocean acidification in a reef-building coral. Sci. Adv. 4, eaar8028. https://doi.org/10.1126/sciadv.aar8028 (2018).

Zhou, G. et al. Microbiome dynamics in early life stages of the scleractinian coral Acropora gemmifera in response to elevated pCO2. Environ. Microbiol. 19, 3342–3352. https://doi.org/10.1111/1462-2920.13840 (2017).

Terrell, A. P., Marangon, E., Webster, N. S., Cooke, I. & Quigley, K. M. The promotion of stress tolerant Symbiodiniaceae dominance in juveniles of two coral species under simulated future conditions of ocean warming and acidification. Front. Ecol. Evol. 11, 1113357. https://doi.org/10.3389/fevo.2023.1113357 (2023).

Veron, J. Corals of the World (Austrialian Institute of Marine Science and CRR Old Pty Ltd. Press, 2000).

Baird, A. H., Guest, J. R. & Willis, B. L. Systematic and biogeographical patterns in the reproductive biology of scleractinian corals. Annu Rev Ecol Evol S 40, 551–571. https://doi.org/10.1146/annurev.ecolsys.110308.120220 (2009).

Yuan, X. et al. Elevated CO2 delays the early development of scleractinian coral Acropora gemmifera. Sci. Rep. 8, 2787. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-018-21267-3 (2018).

Bolger, A. M., Lohse, M. & Usadel, B. Trimmomatic: a flexible trimmer for Illumina sequence data. Bioinformatics 30, 2114–2120. https://doi.org/10.1093/bioinformatics/btu170 (2014).

Grabherr, M. G. et al. Full-length transcriptome assembly from RNA-Seq data without a reference genome. Nat. Biotechnol. 29, 644–652. https://doi.org/10.1038/nbt.1883 (2011).

Altschul, S. F., Gish, W., Miller, W., Myers, E. W. & Lipman, D. J. Basic local alignment search tool. J. Mol. Biol. 215, 403–410. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0022-2836(05)80360-2 (1990).

Shinzato, C. et al. Eighteen coral genomes reveal the evolutionary origin of Acropora strategies to accommodate environmental changes. Mol. Biol. Evol. 38, 16–30. https://doi.org/10.1093/molbev/msaa216 (2020).

Kanehisa, M. et al. KEGG for linking genomes to life and the environment. Nucleic Acids Res. 36, D480-484. https://doi.org/10.1093/nar/gkm882 (2008).

Li, T. et al. Comparative transcriptome analysis of Penicillium citrinum cultured with cifferent carbon sources identifies genes involved in citrinin biosynthesis. Toxins 9, 69. https://doi.org/10.3390/toxins9020069 (2017).

Xiang, L.-X., He, D., Dong, W.-R., Zhang, Y.-W. & Shao, J.-Z. Deep sequencing-based transcriptome profiling analysis of bacteria-challenged Lateolabrax japonicus reveals insight into the immune-relevant genes in marine fish. BMC Genomics 11, 472. https://doi.org/10.1186/1471-2164-11-472 (2010).

Langmead, B. & Salzberg, S. L. Fast gapped-read alignment with Bowtie 2. Nat. Methods 9, 357–359. https://doi.org/10.1038/nmeth.1923 (2012).

Anders, S. & Huber, W. Differential expression of RNA-Seq data at the gene level – the DESeq package. Eur. Mol. Biol. Lab. (EMBL) 10, 1000 (2012).

Young, M. D., Wakefield, M. J., Smyth, G. K. & Oshlack, A. Gene ontology analysis for RNA-seq: accounting for selection bias. Genome Biol. 11, R14. https://doi.org/10.1186/gb-2010-11-2-r14 (2010).

Mao, X., Cai, T., Olyarchuk, J. G. & Wei, L. Automated genome annotation and pathway identification using the KEGG Orthology (KO) as a controlled vocabulary. Bioinformatics 21, 3787–3793. https://doi.org/10.1093/bioinformatics/bti430 (2005).

Kurihara, H., Suhara, Y., Mimura, I. & Golbuu, Y. Potential acclimatization and adaptive responses of adult and trans-generation coral larvae from a naturally acidified habitat. Front. Mar. Sci. 7, 581160. https://doi.org/10.3389/fmars.2020.581160 (2020).

Helgoe, J., Davy, S. K., Weis, V. M. & Rodriguez-Lanetty, M. Triggers, cascades, and endpoints: connecting the dots of coral bleaching mechanisms. Biol. Rev. 99, 715–752. https://doi.org/10.1111/brv.13042 (2024).

Gibbin, E. M. & Davy, S. K. The photo-physiological response of a model cnidarian–dinoflagellate symbiosis to CO2-induced acidification at the cellular level. J. Exp. Mar. Biol. Ecol. 457, 1–7. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jembe.2014.03.015 (2014).

McCulloch, M., Falter, J., Trotter, J. & Montagna, P. Coral resilience to ocean acidification and global warming through pH up-regulation. Nat. Clim. Chang. 2, 623–627. https://doi.org/10.1038/nclimate1473 (2012).

Anand, S. K., Sharma, A., Singh, N. & Kakkar, P. Entrenching role of cell cycle checkpoints and autophagy for maintenance of genomic integrity. DNA Repair 86, 102748. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.dnarep.2019.102748 (2020).

Clarke, P. R. & Allan, L. A. Cell-cycle control in the face of damage–a matter of life or death. Trends Cell Biol. 19, 89–98. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.tcb.2008.12.003 (2009).

Struhl, K. Histone acetylation and transcriptional regulatory mechanisms. Genes Dev. 12, 599–606. https://doi.org/10.1101/gad.12.5.599 (1998).

Turner, B. M. Histone acetylation and an epigenetic code. BioEssays 22, 836–845. https://doi.org/10.1002/1521-1878(200009)22:9%3c836::Aid-bies9%3e3.0.Co;2-x (2000).

Jaenisch, R. & Bird, A. Epigenetic regulation of gene expression: how the genome integrates intrinsic and environmental signals. Nat. Genet. 33, 245–254. https://doi.org/10.1038/ng1089 (2003).

Carusillo, A. & Mussolino, C. DNA damage: from threat to treatment. Cells 9, 1665. https://doi.org/10.3390/cells9071665 (2020).

Hassanpour, M., Rezabakhsh, A., Rezaie, J., Nouri, M. & Rahbarghazi, R. Exosomal cargos modulate autophagy in recipient cells via different signaling pathways. Cell Biosci. 10, 92. https://doi.org/10.1186/s13578-020-00455-7 (2020).

Horbay, R. et al. Role of ceramides and lysosomes in extracellular vesicle biogenesis, cargo sorting and release. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 23, 15317. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijms232315317 (2022).

Scucchia, F., Malik, A., Zaslansky, P., Putnam, H. M. & Mass, T. Combined responses of primary coral polyps and their algal endosymbionts to decreasing seawater pH. Proc. R. Soc. B: Biol. Sci. 288, 20210328. https://doi.org/10.1098/rspb.2021.0328 (2021).

Grosberg, R. K. & Strathmann, R. R. The evolution of multicellularity: a minor major transition? Annu. Rev. Ecol. Evol. Syst. 38, 621–654. https://doi.org/10.1146/annurev.ecolsys.36.102403.114735 (2007).

Tucker, R. P. & Adams, J. C. Adhesion networks of cnidarians: a postgenomic view. Int. Rev. Cell Mol. Biol. 308, 323–377. https://doi.org/10.1016/b978-0-12-800097-7.00008-7 (2014).

Scucchia, F., Malik, A., Putnam, H. M. & Mass, T. Genetic and physiological traits conferring tolerance to ocean acidification in mesophotic corals. Glob. Change Biol. 27, 5276–5294. https://doi.org/10.1111/gcb.15812 (2021).

Hulver, A. M. et al. Elevated heterotrophic capacity as a strategy for Mediterranean corals to cope with low pH at CO2 vents. PLoS ONE 19, e0306725. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0306725 (2024).

Anthony, K. R. N. & Fabricius, K. E. Shifting roles of heterotrophy and autotrophy in coral energetics under varying turbidity. J. Exp. Mar. Biol. Ecol. 252, 221–253. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0022-0981(00)00237-9 (2000).

Acknowledgements

We thank Shize Zhang for coral photography, Dajun Qiu for transcriptomic data analysis, and the staff of the Tropical Marine Biological Research Station in Hainan for logistical support.

Funding

This work was supported by the National Natural Science Foundation of China (U23A2035), National Key Research and Development Project of China (2021YFC3100500), Natural Science Foundation of Guangdong Province, China (2024A1515011041, 2018A0303130173), Hainan Province Science and Technology Special Fund (ZDKJ2019011), and Science and Technology Planning Project of Guangdong Province, China (2023B1212060047).

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

Minglan Guo, Tao Yuan and Hui Huang conceived, designed, and obtained funding for the study. Tao Yuan, Lei Jiang and Guowei Zhou performed the experiments. Minglan Guo analyzed the data, interpreted the results, prepared the figures and drafted the manuscript. Hui Huang provided overall supervision. All authors commented on the draft and revised the manuscript.

Corresponding authors

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher’s note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Supplementary Information

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if you modified the licensed material. You do not have permission under this licence to share adapted material derived from this article or parts of it. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Guo, M., Yuan, T., Jiang, L. et al. Acclimation mechanisms of reef-building coral Acropora gemmifera juveniles to long-term CO2-driven ocean acidification. Sci Rep 15, 30655 (2025). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-15145-y

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-15145-y