Abstract

Severe acute respiratory syndrome coronavirus 2 (SARS-CoV-2) infection can lead to post-acute sequelae of SARS-CoV-2 infection (PASC), or Long COVID, a chronic multisystemic condition with diverse symptoms and no objective diagnostic test. In this retrospective study, we developed a data-driven method to objectively detect persistent physiological changes using wearable device data in a large cohort of over 12,000 US military personnel. We analyzed physiological data from 663 symptomatic COVID-19 positive cases and 2,513 asymptomatic COVID-19 negative controls. Our method identified persistent physiological changes in 9.4% of COVID-19 positive individuals, most commonly manifesting as elevated nightly heart rate and reductions in some heart rate variability metrics. Our findings demonstrate that wearable technology can be used to objectively detect chronic physiological changes beyond the acute phase of COVID-19 illness. Although our method requires further clinical validation, it could potentially provide objective metrics to help standardize Long COVID diagnosis criteria.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Long COVID, also referred to as post-acute sequelae of SARS-CoV-2 infection (PASC), is characterized by the persistence of symptoms following the acute phase of COVID-19 infection1, and is associated with physiological changes that can affect multiple organ systems, leading to enduring alterations in normal body functioning2. It is estimated that between 10 and 35% of infected individuals experience Long COVID3, translating to at least 65 million cases globally4. However, there is currently no precise definition and diagnosis criteria for Long COVID, as different health organizations use different criteria. For example, the United States Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) defines Long COVID as a condition characterized by symptoms lasting at least four weeks after infection5, whereas the World Health Organization (WHO) sets a threshold of three months with symptoms persisting for at least two months6.

Symptoms associated with Long COVID may include persistent fatigue, shortness of breath, chest pain, headaches, cognitive difficulties (“brain fog”), and gastrointestinal issues1. Some patients report neurological symptoms like dizziness and cardiovascular problems such as palpitations and elevated heart rate7. In more severe cases, patients may develop conditions such as postural orthostatic tachycardia syndrome (POTS)8 or symptoms consistent with Myalgic Encephalomyelitis/Chronic Fatigue Syndrome (ME/CFS)4,9. Psychological symptoms, including anxiety and depression, often accompany physical ailments, further complicating diagnosis and treatment10. The diversity of reported symptoms and subjectivity of their severity, combined with the lack of specific biomarkers associated with Long COVID, makes objective detection and diagnosis of Long COVID challenging.

Data-driven criteria, such as specific changes in physiology measured by commercially available off-the-shelf (COTS) wearable devices, may help in establishing objective biomarkers for Long COVID diagnosis. Indeed, the COVID-19 pandemic has accelerated research in digital health and bio-surveillance technologies, and there have been numerous studies that demonstrated the potential of wearables, paired with self-reported symptoms and machine learning algorithms, for early or pre-symptomatic detection of COVID-1911. Here, we briefly summarize prior findings, organized by physiological function/domain:

-

Cardiovascular metrics: Multiple studies have identified elevated resting heart rate (RHR) and heart rate (HR) as early indicators of COVID-19 infection, often preceding symptoms by several days. These findings were observed consistently across wearables such as Apple watch12,13,14 and Fitbit tracker12,14,15,16,17,18. In addition, heart rate variability (HRV), a marker of autonomic nervous system balance, tends to decline during early infection13,18,19. In a large study using Fitbit data, HR elevations persisted for weeks in some individuals, suggesting potential long-term physiological impact18.

-

Respiratory metrics: An increase in respiratory rate (RR) could be another indicator of infection. Studies using devices such as WHOOP20 and BioButton21 have found abnormal RR patterns, particularly during pre-symptomatic phases of infection. Other studies have shown that RR and coughing patterns captured via wearables or integrated microphones were able to differentiate between COVID-19 and other respiratory conditions22. For a comprehensive overview of wearable-based sensing methods, see the review by Ding et al.23.

-

Thermal regulation (skin temperature): Elevated skin temperature is a well-established physiological marker of infection, and continuous monitoring through wearable devices has shown promise for early infection detection, including COVID-19. The TemPredict study19, which enrolled over 63,000 participants using the Oura Ring, demonstrated that continuous physiological data—including dermal temperature—could be used to detect COVID-19 onset with an average of 2.75 days before individuals sought diagnostic testing. Notably, temperature elevations were particularly apparent during sleep and preceded symptom onset in many participants. These findings highlight the utility of wearable devices with high-resolution dermal temperature sensors in detecting early physiological deviations indicative of infection.

-

Behavioral metrics (activity and sleep): Reductions in physical activity (e.g., step counts) and increased sleep duration are frequently observed among infected individuals, reflecting fatigue and malaise14,15,16,17. These behavioral signals, captured passively by devices such as Fitbit and Apple Watch, have been used to flag infection risk. For example, decreased step counts were used to optimize testing allocation for symptomatic individuals based on passive sensor data14. Similarly, increased self-reported symptoms combined with reductions in activity and increased sleep improved early COVID-19 detection accuracy16. Additionally, disruptions in sleep quality , as well as uptime (the amount of time a person spends upright during the day) and duration are increasingly being studied in the context of Long COVID[19,24,25].

While these studies have provided valuable insights into COVID-19 from the wearables perspective, many rely on self-reported survey data, which has several limitations. These include dependence on subjective symptom reporting, which introduces variability and potential under-reporting, particularly when individuals fail to recognize or accurately report their symptoms.

We previously developed a machine learning algorithm called Rapid Analysis of Threat Exposure (RATE) that uses physiological data from COTS wearable devices for early detection of COVID-19 infections26. In brief, we developed RATE in collaboration with the Defense Threat Reduction Agency (DTRA) of the US Department of Defense (DoD), with data collection occurring over a 4-year period, between June 2020 and August 2024 (contract numbers HDTRA120C0041 and HDTRA121C0006). We collected COTS wearables data using Garmin watches and Oura rings from over 12,000 military personnel and self-reported daily health surveys using a bespoke web-based app. While we did not explicitly track whether COVID positive participants developed Long COVID due to the nature of the data collection and goal of the study (pre-symptomatic infection detection), our findings from this work and a follow-up study27 demonstrated that wearables can effectively detect physiological changes during the acute infection phase, consistent with other studies12,13,14,15,16,17,18,19.

Building on our prior work, the goal of the present retrospective study was to develop an objective method for detecting chronic persistent changes in physiological parameters due to COVID-19 infection using wearables data.

Results

Study population and cohort selection

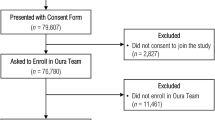

As of June 3, 2024, a total of 12,698 participants enrolled in the study over a four-year period (from June 27, 2020, to May 21, 2024). Participants underwent COVID-19 testing using RT-PCR or rapid tests. Among enrolled participants, 4,614 had at least one COVID-19 testing result. See Table 1 for characteristics of the population.

The cohort selection process is illustrated in Fig. 1, which was generated by SankeyMATIC flowchart builder28. Our analysis focused on the wearables data from these unique users, ensuring that, for users that had multiple COVID-19 tests, only data from their last COVID-19 test were included. In addition to wearing the devices, participants were asked to complete a brief daily online survey, which collected self-reported symptoms and reason for COVID-19 testing. The comprehensive list of symptoms is included in Supplementary Note 6. Participants were categorized based on their reported reason for testing. Among those who tested negative, N = 3,163 participants reported “no symptoms” at the time of testing, N = 450 reported the presence of symptoms, and 241 had no recorded reason for testing. Among those who tested positive, 212 participants reported “no symptoms”, 512 reported symptoms, and 36 had no recorded reason for testing. Among participants who tested negative for COVID-19 and reported “no symptoms” as the reason for testing (N = 3,163), 2,891 were identified as baseline asymptomatic. Participants who exhibited symptoms during the baseline window (− 42 to − 13 days prior to testing) were excluded. Among the remaining participants, those who developed symptoms during the study window (0 to + 57 days post-testing) were further excluded. This resulted in a final cohort of 2,513 COVID-19 negative, baseline asymptomatic participants.

Similarly, among COVID-19 positive users, baseline asymptomatic individuals were identified across all reason-for-testing groups. Specifically, 189 participants from the “no symptoms” group (N = 212), 443 participants from the “with symptoms” group (N = 512), and 31 participants from the “unknown reason for testing” group (N = 36) were confirmed as baseline asymptomatic. These participants comprised the final COVID-19 positive cohort (N = 663).

No additional users were excluded based on the testing or study window. By excluding individuals who reported any symptoms during the baseline period, the study aims to establish a clearer distinction between the baseline (pre-infection) physiological state and the changes observed post-infection. This conservative approach helps to reduce confounding factors and ensures that any detected changes are more likely to be associated with the effects of COVID-19, rather than being influenced by symptoms present before the testing window. Overall, the selection process resulted in two distinct cohorts for analysis: 2,513 COVID-19 negative users and 663 COVID-19 positive users. For each user, we defined three key temporal windows: a baseline window (Day − 42 to − 14 relative to the test date), a testing window (Day − 7 to + 6), and a study window (Day + 28 to + 56), as described in the Methods section and applied consistently across the analysis. The baseline window is used to compute individualized normative physiological profiles, while the testing window captures the acute infection period. These windows were applied to all physiological features used in the detection method.

Detection of persistent changes: prevalence findings, Monte Carlo simulation, and risk analysis

The results from the detection of persistent changes captured via wearables are shown in Table 2. Overall, from 663 COVID positives, 349 met the compliance criteria for the subset of physiological parameters. We defined compliance criterion as the availability of at least 60% of nightly physiological parameter measurements on both the baseline and the study windows. That corresponds to ~ 17 out of 28 days on both the baseline and the study windows. Of those 349 COVID positives users, 33 were found to have persistent physiological changes in the post-infection period by the method introduced later in this study (Section “Detection of persistent change using null distribution from negative cohorts”). Briefly, this method compares deviation patterns in multiple wearable parameters across pre- and post-infection windows and using COVID-19 negative users as a statistical control group. The persistent physiological changes detected with this method yielded a prevalence rate of 9.4%. In comparison, we performed 1000 simulations with randomly selecting 663 users (the same size as the COVID positive cohort) who tested negative for COVID. On average, the results showed 270 of those subjects met the compliance criteria, of which 5.3 on average showed a persistent change (average prevalence rate of 1.9%).

A post-hoc two-away ANalysis Of VAriance (ANOVA) was done to determine possible testing confounders. The frequency of testing was the dependent variable and the two independent variables, and their interactions were: (1) month of testing and (2) COVID group (COVID Negatives, COVID positives, and COVID positives with persistent changes). The results of ANOVA showed that only the month of testing was a significant factor (p < 0.05), with a higher testing frequency in the winter months. No difference on the frequency of testing was found to be significant across the three COVID groups and its interaction with month of testing.

Risk analysis was performed via logistic regression on the detected persistent changes in COVID-19 positive subjects, and with risk factors including sex, age category, vaccination status (none or 1 or more vaccines), and weight category. In terms of model quality, the fitted model achieved a log-likelihood ratio p-value of 0.14, indicating that the model does not reach statistical significance at the 5% level.

Among different age groups, only the middle age group (50–64 years) had a statistically significant odds ratio (OR = 3.22, p = 0.027) for the risk of persistent changes, as shown in Fig. 2. Other findings, which did not reach statistical significance at the 5% level (e.g., p-values ≥ 0.05), included the following: male subjects were overall 3.9 times more likely to develop persistent changes (p = 0.1); individuals in the highest weight category (111–123 kg) had an increased risk with an OR of 2.0 (p = 0.1); and vaccination reduced the risk of developing persistent changes by an estimated OR of 0.4 (p = 0.1). Although these patterns are notable, particularly with respect to vaccination status, only the age factor achieved statistical significance at the 5% level. The lack of significance in the sex effect may be attributed to the limited sample size. The details of the risk factor analysis are included in Supplementary Note 1 and the demographic details of the COVID positives with persistent changes are depicted in Supplementary Note 2.

Summary of persistent changes: physiological biomarkers

From the COVID-19 positive cohort of 349 individuals who met the minimum data availability (compliance) of 60% or more on both baseline and observation windows, 33 users exhibited persistent physiological changes as captured by wearable devices. Across these 33 users, a consistent pattern of elevated heart rate (on average 7 bpm elevation in the nightly heart rate corresponds to ~ 13% increase from averaged population baseline) was observed throughout the study period, accompanied by a concurrent decline in one of the prominent heart rate variability (HRV)-related features, RMSSD (on average the RMSSD dropped from ~ 65 milliseconds over the population baseline to 45 milliseconds ). The Root Mean Square of Successive Differences (RMSSD) is a commonly used time-domain measure of Heart Rate Variability, representing the variability between successive heartbeats. Specifically, RMSSD captures the short-term variability in heart rate, making it a good indicator of parasympathetic nervous system activity29. Out of 257 physiological parameters that met the feature compliance threshold of 60%, physiological features constantly triggered by > 25% of the users detected with persistent changes among COVID-19 positive cohort are depicted in Fig. 3. Highly repeated features among the COVID positives with persistent changes are increased values of 20th percentiles of nightly heart rate measurements (nightly HR_pct_20) during the study window compared to the individual baseline. See Supplementary Note 4 for the comprehensive list of physiological features.

Figure 4 captures the long-term trend of two sample physiological parameters: nightly 20th percentile of heart rate (HR_pct_20) and nightly median of the root mean square of successive differences (RMSSD) in heartbeats (rmssd_pct_50), normalized based on the individual mean and standard error of the mean over the baseline window (Day − 42 to -14) for the selected cohorts of (i) asymptomatic COVID negatives; (ii) COVID positives with persistent changes; and (iii) the rest of the COVID positives. In Fig. 4-a, we observed that COVID positive users who identified with persistent changes exhibited a pronounced and prolonged increase in normalized heart rate following the testing day (Day 0), with nightly heart rate measures that remained elevated for several months on average. This persistent elevation has a different trend compared to the rest of COVID positive group, whose heart rate returned to the baseline much quicker. The COVID negative group showed no significant deviations from baseline throughout the study window (42 days before the testing day to 56 days after the testing day). A similar pattern of elevated heartrate increase was seen in SARSCoV-2–positive individuals with persistent changes compared with other positive cases30.

Figure 4-b shows the trend of nightly median RMSSD, a key measure of HRV, demonstrating persistent but moderate reductions among the COVID positive with persistent change group relative to baseline in the post-testing period. While less pronounced than the 20th percentile of heart rate, some HRV features remain disrupted for several months following the acute phase among the group who identified with persistent changes. The rest of the COVID positive group exhibited minimal deviations from baseline HRV, indicating a faster physiological recovery. COVID negative participants showed marked fluctuations in HRV, especially for the first 50 days after the testing day, possibly due to declining sample size. As fewer participants contribute data over time, and smaller sample sizes tend to yield higher variability and can amplify variations in the measured physiological feature. The daily counts of COVID negative users, COVID positive, and COVID positive users detected with persistent physiological change are shown separately in Fig. 4-c and -d, and Fig. 4-e, respectively.

We note that the number of users contributing wearables data varied across groups and over time, which may influence the width of the confidence intervals observed for the selected physiological parameters. The group identified with persistent physiological changes consisted of only 33 users, and naturally experienced greater data attrition in later time points. This is reflected in the wider confidence bands observed beyond Day 100. In contrast, the COVID negative group maintained a substantially larger and more stable user base (with > 700 users contributing data well past Day 150), resulting in narrower variability and more consistent estimates. The rest of the COVID positive group also exhibited a moderate decline in user participation over time, but due to its larger size, it maintained more stable trends. While the increased variability in the persistent change group is an inherent limitation due to sample size, the observed sustained elevation in 20th percentile of heart rate and reduction in some HRV features remain distinguishable across both control groups. Detailed plots showing daily user counts for each group are provided in Fig. 4-c and -d, and Fig. 4-e for reference. Also, we note that in the pre-test period (Days − 60 to − 40), the persistent change group exhibits greater variability relative to other groups. This is likely due to a smaller and more dynamic sample size early in the timeline.

Long term individualized-baseline z-scored trend of two sample physiological parameters from 60 days before the testing day to 200 days after the testing day. Panels (a) and (b) show the normalized trajectories for users with detected persistent physiological change (orange), other COVID positive cases (red), and COVID negative individuals (blue). The vertical dashed red line indicates the testing day. Panels (c), (d), and (e), display the number of unique users contributing data each day: (c) COVID negative users, (d) COVID positive users, and (e) COVID positive users with detected persistent physiological change. There are N = 2,513 COVID negative users and N = 663 COVID positive users, within which N = 33 users with detected persistent physiological change are identified. The shaded areas in (a) and (b) reflect the standard deviation across individuals; note that the widening of the shaded region over time, particularly for users with detected persistent physiological change, reflects increased variability due to participant attrition.

Self-reported symptom prevalence versus wearables-only metrics

To determine whether participants detected as having persistent physiological change by wearable-only metrics also report more symptoms, we examined symptom prevalence in the study window (weeks 4–8 post-test). Daily surveys recorded the presence or absence of CDC-listed symptoms (see Supplementary Note 6). For each participant, we assigned a weekly indicator: symptom = 1 if the individual reported at least one symptom on any day of that week, otherwise 0. When analyzing the 4–8 week post-test period, symptoms occurred in 4 of 165 person-weeks (2.4%) for the persistent-change cohort versus 98 of 15,715 (0.62%) for the acute cohort (χ² = 5.71, p = 0.017; risk ratio = 3.9, 95% CI 1.4–10.4). The analysis may provide an external behavioral validation of the wearable-derived classification. Supplementary Note 8 summarizes symptom prevalence in weeks 4–8.

Figure 5 shows trends in the nightly physiological measurements – specifically, nightly percentile 20th of heart rate (HR_pct_20), nightly median RMSSD (rmssd_pct_50), as well as nightly percentile 90 of temperature (TEMPERATURE_pct_90), nightly median respiratory rate derived from IBI (RR_pct_50), and nightly median SpO2 (SPO2_pct_50) – captured via wearable devices from 42 days before to 200 days after COVID-19 testing day (Day 0) for an example COVID-19 positive user whom we identified with persistent changes in physiological parameters. This example case should be interpreted solely as a non-generalizable exemplar. It illustrates the level of temporal granularity that continuous wearable monitoring can offer.

The black lines represent the overall signal trends (average measurements during sleep), with significant changes observed in both 20th percentile of HR and some RMSSD features during the study window and beyond. The HR_pct_20 nightly values for the user show notable increases post-infection compared to their own baseline indicated by red shaded regions. Particularly, we observe a sustained elevation around the ~ 16 to ~ 150 days mark. The rmssd_pct_50 parameter similarly shows considerable deviation compared to baseline during the same period, reflecting a decline in HRV. HRV is a known marker of autonomic nervous system activity, and its perturbation indicates potential autonomic dysfunction, which has been associated with Long COVID symptoms31.

In addition, self-reported symptoms are indicated by blue diamond marks in Fig. 5. The comprehensive list of symptoms is reported in Supplementary Note 6. These symptom clusters overlap with notable variations in the physiological parameters, especially around Day 0 and a few during the study window.

Longitudinal trend of five sample physiological parameters (SpO₂, respiratory rate, skin temperature, heart rate, HRV) captured via wearables from one representative user, who identified as a Long COVID case w.r.t. the COVID-19 testing day (day = 0). The plot shows nightly measurements from day=-60 to day = + 200. The green area (day=-42 to day=-14) is the baseline window, the blue area (day=-7 to day = + 6) is the testing window, and the magenta area (day = + 28 to day = + 56) is the study window. Shaded regions represent baseline (green), testing (blue), and study (magenta) windows with horizontal bands indicating baseline 90% confidence intervals. Overlay diamond markers denote self-reported symptoms categorized by system (general, respiratory/cardiac, neurological, other) identified by the CDC guideline for Long COVID.

Discussion

Utility of wearable technology for objective detection of persistent changes and implications for Long COVID Detection

In this retrospective study, we investigated wearables data from a large cohort of US military personnel and developed an objective method to detect chronic physiological changes post COVID-19 infection, leveraging a COVID-19-negative cohort for comparison. Our results may offer new insights into the long-term impact of the infection on key health metrics. We described an objective data-driven approach using wearable physiological data such as HR, HRV, temperature, and SpO2, to minimize biases inherent in relying on self-reported symptoms for disease progression. This approach can potentially address a common issue with COTS-based health studies – low user compliance in symptom reporting – and can offer a scalable and objective method to estimate the likelihood of persistent physiological change post-infection. By focusing solely on physiological data, we were able to develop an objective, reproducible detection mechanism, which may offer an alternative approach to monitor and treat people who have persistent physiological change post-infection. Additionally, using a control group that tested negative for COVID-19 ensured clearer differentiation between long-term persistent change post COVID-19 infection and other physiological changes, potentially providing evidence to support a more comprehensive understanding of the condition. Our results indicate that wearables can effectively detect the long-term effects of COVID-19, particularly through HR and HRV, in alignment with clinical studies on post-acute sequelae of COVID-19 (PASC).

Previous studies have demonstrated similar trends, where elevated heart rate and decreased heart rate variability were reported as hallmarks of autonomic dysfunction in individuals recovering from COVID-1931,32. The consistency of these findings across the detected COVID positive with persistent change group further strengthens the hypothesis that COVID-19 induces lasting autonomic imbalances, which could contribute to prolonged symptoms and health complications in a subset of patients.

The persistent elevation in the heart rate among the detected COVID positive with persistent change users (Fig. 4-a) suggests that the virus has long-term effects on cardiovascular function, which is measurable via wearables, even after the acute phase of illness. This could be related to autonomic dysfunction or other post-viral syndromes commonly seen among the COVID positives with persistent change that extend well beyond the acute phase of infection. The variability in the trend of physiological parameters realized in the detected COVID positives with persistent change users, for example, the trend of nightly 20th percentile of heart rate over the same group, could indicate that while some individuals may experience mild heart rate elevation, others may have more significant and prolonged symptoms, emphasizing the heterogeneous nature of the persistent change. Nightly HRV depicted by RMSSD (Fig. 4-b) remains deviated from the baseline for several months following the acute phase. The persistent reduction in RMSSD observed in the detected persistent change group could potentially indicate a chronic autonomic system dysfunction. Reduced HRV is commonly associated with chronic stress, fatigue, and other physiological stressors, which are hallmarks of Long COVID. A reduction in RMSSD in the detected persistent change group may suggest chronic dysregulation of the autonomic nervous system (ANS), specifically a suppression of parasympathetic tone33. While other COVID positive users return to baseline RMSSD relatively quickly, the detected persistent change group shows either no such recovery or a much slower process.

The trend of elevated heart rate and reduced heart rate variability mirror the ongoing autonomic and cardiovascular disruptions that many Long COVID patients report7. These findings highlight a potential for wearable devices to capture subtle, long-term physiological changes that are often missed by traditional clinical assessments. The observed elevation in 20th percentile of heart rate around days ~ 15 to ~ 150 post-infection for the sample subject in Fig. 4-a, coupled with concurrent decline in HRV in Fig. 4-b, are particularly notable. Such patterns are consistent with symptoms of postural orthostatic tachycardia syndrome (POTS), which has been associated with Long COVID34. This autonomic dysfunction, characterized by abnormal heart rate responses, is further supported by the decrease in (nightly median of RMSSD) rmssd_pct_50, an indicator of reduced vagal tone and heightened sympathetic activity.

Independent validation and clinical relevance

The symptom-prevalence analysis may offer an external verification of the wearable-based algorithm. Participants showing sustained physiological deviations were roughly 4-times more likely to report symptoms during weeks 4–8 post-infection than the rest of the COVID positive cohort, which is aligned with what we found from the wearables data. During the study window (weeks 4–8), the proportion of participants who reported at least one CDC-listed symptom was consistently higher in the persistent-change group than in the rest of COVID positive group, and the pooled risk ratio was ~ 8 (Supplementary Note. 8), although only week 6 reached Holm-corrected significance. Weeks 7–8 were uninformative owing to zero events in the persistent-change cohort, highlighting the need for larger samples and longer follow-up.

Impact of vaccination on detected persistent changes on wearables and long COVID

The distribution of the subjects’ days of vaccination with respect to the testing day is included in Supplementary Note 7. Multiple studies have underscored the role of COVID-19 vaccination in reducing the risk of Long COVID. In our study, vaccination reduced the risk of developing persistent physiological changes by approximately 40%, which aligns with broader findings in the literature based on diagnosed Long COVID. For instance, a large community-based study from the UK demonstrated that individuals who received two doses of the COVID-19 vaccine at least 2 weeks before COVID infection were associated with a 41% decrease in the odds of developing Long COVID symptoms at least 12 weeks later, relative to unvaccinated individuals35. The protective effect of vaccination appears to extend across variants, although the overall risk of Long COVID has decreased over the course of the pandemic. Data from the Veterans Affairs Health Care System showed a significant reduction in the cumulative incidence of Long COVID, decreasing from 10.42 events per 100 persons in the pre-Delta variant era to 7.76 per 100 in the Omicron variant era among unvaccinated individuals36. The effect was even more substantial in vaccinated individuals, where incidence dropped from 5.34 to 3.50 events per 100 persons over the same period, with vaccination associated with 44% lower odds of developing Long COVID in the Omicron era (OR = 0.45, 95% CI, 0.43 to 0.47). This highlights the strong role of vaccination in mitigating Long COVID risk.

The reduction in Long COVID incidence in vaccinated individuals may be attributed to the boosting of immune responses. Vaccination enhances the production of neutralizing antibodies and T-cell responses, which may help prevent the viral persistence and immune dysregulation often associated with Long COVID4. This protective effect is particularly relevant for high-risk populations, as seen in our cohort, where middle-aged individuals (50–64 years) were at a significantly higher risk for persistent changes post-infection, but vaccination contributed to lowering this risk.

Impact of self-reported survey data

While our study relied on daily self-reported survey data for the development of the algorithm, a deployed algorithm solution would not rely on surveys as input. At deployment time, our algorithm would only require a COVID diagnosis and wearables data. While we admit that the issues we discussed in the Introduction section regarding self-reported surveys could have affected the quality of the information we received in the surveys in this study, we believe that they did not cause any form of systemic biases or confounding effects between the Long COVID and non-Long COVID groups.

Future direction and limitations

Looking ahead to an algorithm deployment scenario, we envision our wearable-based detection method as a practical tool for continuous, non-invasive monitoring of physiological recovery following COVID-19 infection. In contrast to traditional diagnostic practices — which typically rely on periodic physical exams, imaging, and patient-reported symptoms — our method offers an objective, longitudinal perspective by quantifying deviations from individual’s own physiological baseline using wearable devices. Importantly, this approach is not intended to replace clinical evaluation, but rather to complement existing diagnostic workflows by providing an additional, data-driven signal that may support early identification of persistent change and guide follow-up care. For instance, clinicians could use a dashboard interface to track patterns such as elevated resting heart rate or suppressed HRV, while patients could independently monitor their recovery trajectories. This system could be deployed as a decision support layer within clinical or occupational health settings, especially where Long COVID treatment remains challenging. Furthermore, our approach builds on prior work (RATE)26 for pre-symptomatic detection and could serve as a post-acute extension, forming part of a comprehensive wearable-based health monitoring framework. Real-world implementation would need to address issues such as covariate shift, data privacy, and interpretability, especially in shared-use scenarios between healthcare providers and end users.

This study has several important limitations that should be noted. A key limitation is the lack of access to clinical diagnoses of Long COVID. Without clinician-confirmed diagnoses, it is difficult to validate our methodology and findings, as the study relied solely on physiological parameters captured via wearables. While these wearables-based parameters provide objective data, they may not fully capture the complex and heterogenous nature of Long COVID. Access to clinical diagnoses would offer a standard reference point, allowing for more precise validation of the methodology.

Additionally, the compliance threshold of 60% for wearable device usage, although necessary for ensuring data quality, may have led to the exclusion of individuals who wore their devices inconsistently. This could result in selection bias, as those who consistently wore their devices might be more likely to have more severe or persistent symptoms, thus influencing the prevalence estimates. Future research should aim to improve compliance rates and data coverage by employing more user-friendly wearable systems and devices.

One key methodological limitation is the potential sensitivity of our approach to population differences between the negative (null) and testing groups. For example, males comprised 80% (vs. 20% females) of our dataset, which may have influenced our ability to detect persistent changes in females and contributed to the observed risk discrepancies between sexes. Interestingly, while the bias remains the same for acute COVID infections (81% males vs. 18% females), we do notice a substantial further increase in the sex bias for the persistent change group (90% males vs. 9% females). In addition, both the baseline and observation windows had 4-week durations, enough to capture the average full female menstrual cycle. Altogether, this would be in agreement with studies showing that females have stronger immune systems37,38. These changes are unlikely to be due to menstrual cycles, particularly the luteal phase effects. If we were to assume the luteal phase is indeed contributing to these abnormal persistent changes, then we should have observed an overall decrease in the sex bias on the COVID persistent change group and not the increase reported above.

The same however, cannot be said about the age bias persistent in our dataset. Our dataset is also biased toward a younger population, making it difficult, in the scope of this study, to understand to causality factors due to age. Addressing population imbalances in future research will be critical to improving generalizability and reducing biases of the algorithm. Towards this end, acquiring sufficient data may allow us to improve on this method by having a null distribution of the negative cohort matched across sensitive groups of interest.

Additionally, our detection method was designed to prioritize specificity at the cost of sensitivity. By requiring sustained and consistent deviations from individualized baselines and cross-referencing with a COVID-negative control group, we aimed to reduce false positives, ensuring that detected cases represent meaningful physiological changes. This was a deliberate choice to ensure that the cases we detect are easily interpretable from wearable data, with a high level of agreement between human experts. However, this approach may limit sensitivity, potentially missing milder or less consistent changes. Future research could explore alternative thresholds or methods to improve sensitivity while maintaining high specificity, providing a more comprehensive detection of users with persistent physiological changes impacts, but perhaps at the cost of losing interpretability.

Methods

Study design and data collection procedures

Here, we briefly describe details of our previous study and their relevance to the current study. For further details on the study design, data collection platform, and device selection, please see26. After enrollment, study participants were distributed a Garmin watch (Fenix 6 or Vivoactive 4 models) and/or an Oura ring. The physiological parameters used in the current study from the Garmin devices were: respiration rate (RR) and pulse oximetry (SpO2), while the physiological parameters used in the current study from the Oura device were: inter-beat interval (IBI), skin temperature, and sleep hypnogram. The physiological parameters from both Garmin and Oura wearables were aggregated per sleep episode, as determined by Oura’s hypnogram, into sets of statistics (i.e.: mean, 5th percentile, 95th percentile, standard deviation, coefficient of variation, etc.). No data outside Oura’s hypnogram periods were used. Integration with Garmin watches was achieved by creating a Garmin Connect Developer account that enabled Garmin watch participants to enroll in the data sharing study via an OAuth authentication process. Integration with Oura rings was achieved by creating an Oura Teams account that enabled Oura ring participants to consent to share their data with the study via a secure authentication step during registration. Participant data were automatically downloaded from the Oura cloud without the collection of any personally identifiable information via custom software that was scheduled to run frequently on the study platform. For further additional detailed on the data collection platform and device selection and handling please see26.

Participants were asked to complete a daily survey, which collected self-reported symptoms and fiducial points for vaccination or positive and negative test results for infection, including COVID-19. Individuals were tested by a COVID-19 RT-PCR or rapid test. Individuals reported test dates and results via a daily web-based survey. The survey data was periodically verified with the individual by study personnel for all COVID-19 positive cases to ensure the results and symptom fiducial points were accurate (see26 for more information) for additional details. For the final cohort, only one individual COVID-19 test was used per user. Thus, in this study, all users were in one of three mutually exclusive groups: COVID-19 Negative, COVID-19 Acute, or COVID-19 with persistent changes.

Ethical approval

The collection and use of the wearable dataset was approved by the Institutional Review Boards of the US Department of Defense. All methods were carried out in accordance with relevant guidelines and regulations. Informed consent was obtained from all participants.

Physiological parameters

The physiological parameters monitored in this study include direct measurements from the wearable devices and custom analytics derived from IBIs recorded during sleep (as detected by Oura’s hypnogram). We chose to focus on physiological data during sleep because sleep provides relatively stable and high-quality measurements26: pulse rate, skin temperature, and SpO2. Respiratory rate was derived from IBIs. Additional custom heart rate variability features were also computed. The complete list of physiological features collected during an entire sleep episode are summarized in Supplementary Note 4.

For each physiological parameter, a set of 23 statistics were computed in order to aggregate the physiological data during sleep. The aggregated statistics were: min, max, mean, std, skewness, kurtosis, hyperskewness, hypertailedness, pct_1 (1st percentile), pct_5, pct_10, pct_20, pct_25, pct_30, pct_40, pct_50, pct_60, pct_70, pct_75, pct_80, pct_90, pct_95, pct_99. Thus, yielding a total of 34 physiological parameter \(\:\times\:\) 23 statistics = 782 features per segment of sleep.

Data window selection

For each participant, we established three time windows: (1) a baseline window, (2) a testing window, and (3) a study window. The baseline window serves as a control reference prior to the testing date as shown in Fig. 6, and it spans over 4 weeks (28 days), from 6 weeks before testing day to 2 weeks before testing day. The infection (testing) window, defined as the time frame around the testing day when clinical testing occurred, spans over 2 weeks (14 days), from one week before the testing day to one week after the testing day. The study window spans over 4 weeks (28 days), from 4 weeks after the testing day to 8 weeks after the testing day. These parameters for start and duration of the study window were chosen based on the CDC guidelines for detecting Long COVID5,6. While the CDC defines post-COVID conditions as symptoms lasting at least four weeks post-infection, the WHO, National Academy of Sciences, and other international bodies define Long COVID more conservatively, typically requiring the presence of symptoms at least 12 weeks after acute infection. The 4–8 week study window used in this work, though informed by CDC guidance, may therefore reflect an early post-acute recovery period rather than the chronic phase of Long COVID. Accordingly, our findings should be interpreted as indicative of infection-acquired persistent physiological changes, which may represent precursors or components of Long COVID but cannot, in the absence of formal clinical diagnosis, be equated directly with WHO-defined cases.

Wearable compliance

Compliance refers to the percentage of time participants wore the wearable device(s), resulting in usable data for analysis. Data from wearable devices often have varying levels of completeness due to inconsistent usage or technical issues. In this study, we derived physiological parameters using data collected from either the Oura ring or the Garmin watch or both together. The availability of specific physiological parameters depended on the presence of corresponding raw physiological features such as HR, temperature, blood oxygen saturation (SpO2), and IBI. Consequently, aggregated statistics were only available when the corresponding raw physiological data were fully present. These factors cause varied compliance across different physiological parameters and across different users, posing a key challenge in ensuring participant compliance, as inconsistent device usage can lead to data gaps, compromising the accuracy and reliability of physiological feature extraction and analysis.

To mitigate this issue, we included only users and physiological features with at least 60% coverage (compliance) across the baseline and observation (study) windows. To give a reference, a 10% compliance threshold implies that participants wore the wearables at least 10% of total days for both baseline and observation windows, which corresponds to almost 3 days for each window, whereas, for instance, an 80% compliance indicates near-continuous usage (22 out of 28 days for both baseline and study windows). Here 60% compliance corresponds to roughly 17 days of nightly physiological measurements.

A day was considered compliant for a given physiological parameter if the participant had valid wearable-derived data covering at least one complete sleep segment, as detected by the device’s (Oura or Garmin) built-in sleep algorithm. In this study, we only considered sleep periods with ≥ 4 h of consecutive nighttime data. Days with < 4 h of usable sleep data or data recorded exclusively during waking hours were excluded from compliance calculations.

To account for the inherent variability in the availability of each wearable physiological parameter, the compliance criterion was evaluated individually for each parameter. After filtering for 60% compliance threshold on every physiological parameter, on average 31.7% of COVID positive and 22.5% of COVID negative subjects were included in the analysis. Alternative selection criteria based on other compliance thresholds and the corresponding resulting sample sizes are shown in Supplementary Note 3.

Determining infection-acquired feature deflection

To establish our methodology for detecting sustained changes long after the acute phase of COVID-19 infection, we first defined a direction of change associated with the infection for each physiological parameter. Specifically, we identified how COVID-19 viral infection might alter the baseline for each parameter during the infection period. We employed a data-driven approach to determine if deviation of a physiological parameter during the study window is in the same direction of the deviation of the same parameter during the acute infection relative to the baseline levels. For instance, with this approach, a comparison of the baseline and infection window shows an increase in heart rate in the latter, from which we then assume increases in heart rate represent an infection. We then compare the baseline window and the study window, assuming again that increases in heart rate represent the infection and decreases in heart rate are ignored or assumed normal. This approach allows us to define in a data-driven way the healthy state or direction for all features including custom ones (where healthy state may not be so obvious). In addition, by applying this conservative filtering, we aim to further reduce false positives by including only persistent changes that are related to an adverse state of health. Moreover, by integrating the direction of deflection, we were able to provide a more comprehensive understanding of how COVID-19 infection may alter physiological parameters captured via wearables.

We acknowledge the limitation that in some instances, an abnormal change may not be reflected when comparing the average value of the feature across windows, for example, abnormal changes could yield a change in variance, skewness, or tailedness rather than the central tendency. However, we expect to observe a significant deflection in at least a subset of these parameters with respect to parameters’ mean values over each window, whether it be an elevated deflection, suppressed deflection, or no-change.

For each physiological parameter, the difference between its individual mean value during the testing window and the baseline window is calculated. For each participant and each physiological parameter, the mean value during the baseline window as well as the mean value during the testing window are calculated. We compute the deflection as:

In our calculation, we used the “adjusted deflection” metric, a standardized effect size measure similar to Cohen’s d, to determine the direction of change (Eq. 1). A positive value indicates an increase, while a negative value signifies a decrease during the testing (infection) window.

For each feature across all participants, we assessed the overall trend by computing the average adjusted deflection, and we output a + or – sign named feature_direction.

In a supplementary analysis, we also reported the significance and magnitude of the average adjusted deflections for the top 10 features. See Supplementary Note 5 for more information.

Detection of persistent change using null distribution from negative cohorts

To identify users with significantly persistent physiological parameter(s) changes post-acute COVID-19 infection, here we utilized a dual-cohort approach involving users who tested positive as well as users who tested negative for COVID-19. This methodology allowed detecting individuals with persistent changes specifically attributable to the aftermath of COVID-19 while accounting for natural variability. Here the dual-cohort methodology to identify users with persistent changes post COVID-19 is explained:

-

1.

Baseline and confidence interval (CI) calculation per physiological parameter.

We began by establishing individualized baselines for each physiological parameter, derived from pre-infection data, i.e., data unaffected by COVID-19. For each subject and each physiological parameter, a 90% confidence interval (CI) was calculated in the baseline window, representing the typical range within which 90% of the baseline values are expected to fall. The CI serves upper and lower threshold for identifying deviations that are likely to be significant.

-

2.

Study window and identification of significant changes.

Significant changes post-acute infection were identified by flagging nightly measurements where a physiological parameter fell outside the 90% CI of its baseline (upper or lower the CI band) for more than 90% of the time during the 4-week study window. We call this statistic the out-of-bound percent. The metric indicates a sustained deviation from individualized pre-infection baseline, suggesting a persistent impact of COVID-19. This stringent criterion ensures that only sustained and consistent deviations, indicative of possible lingering effects of COVID-19, were flagged as significant.

-

3.

Null distribution using COVID-19 negative cohorts.

To further validate our findings, we employed data from the COVID-19 negative cohort as a null distribution. This control group consisted of individuals who tested negative for COVID-19, had no symptoms during the baseline window, and remained symptom-free throughout the testing window, as well as the study window. By applying the aforementioned criteria, we aimed to ensure that the physiological parameters of the COVID-19 negative cohort were representative of uninfected conditions.

The out-of-bound percent metric calculated in the previous step, should demonstrate a significant difference from the corresponding physiological feature in the COVID-19 negative cohort. This criterion ensures that the observed changes are specifically related to COVID-19 infection and not part of natural variability and/or biases. A significant difference was determined by comparing the out-of-bound percentage for each feature in the COVID-19 positive cohort to a null distribution derived from the COVID-19 negative cohort, using a 5% significance level. For each feature, subjects with an out-of-bound percentage exceeding the 95th percentile of the same feature in the COVID-19 negative cohort were selected.

By comparing the changes observed in the COVID-19 positive cohort against this null distribution, we were able to distinguish changes specifically attributable to the post-COVID-19 condition from those that might occur naturally or due to other unrelated factors.

-

4.

Direction of change over the study window.

The physiological feature needs to show a deflection in the same direction as that of the infection window (feature_direction). This criterion helps to reduce false positives and identify only changes that imply a deterioration in health status. Building on the infection-acquired feature deflection, we further analyzed the direction of these changes to understand their association with COVID-19 infection. Significant physiological parameter changes, identified by their sustained deviation from the 90% CI of the baseline for more than 90% of the time during the study window, were examined to determine whether these deviations indicated an increase or decrease relative to the baseline. Only the deviations that matched the sign of feature_direction were retained.

-

5.

Feature down-selection based on coverage and correlation.

After the abovementioned individual feature selection algorithms, the following detection fusion algorithm is computed as a post-hoc correction to control for the number of null tests being performed:

-

Begin with a ranked list of features, prioritizing those with the highest coverage (compliance) in the COVID-19 positive cohort.

-

Sequentially eliminate co-triggered features that have a Spearman correlation of 0.8 or higher in the population.

-

After this step, we obtain a subset of M features, where all features in this subset have detection outputs that are less than 0.8 correlated with one another.

-

6.

Per subject detection of persistent change.

By marking persistent changes per-physiological parameter, a detection on a single subject basis was triggered based on the following criteria:

a) Count available features:

-

Determine the count F, which represents how many of the M features are available and non-missing for the user (either flagged as with persistent changes or not), accounting for potential compliance issues.

b) Post-hoc correction with a binomial distribution and detection:

-

Assuming the remaining features are independent (as ensured in Step 1), model the triggering of the F random features using a binomial distribution with a success probability of p = 0.05 (corresponding to the 5% false positive rate) (Eq. 2).

-

Calculate the maximum number K of features that could be triggered while still resulting in a 5% or lower probability of occurring by chance under this binomial model (Eq. 3).

Or (Eq. 4):

-

Count S, the total number of features triggered for the user.

-

If S ≥ K, classify the user as exhibiting persistent physiological changes.

-

If S < K, assume no persistent change was detected, and interpret the triggered features as likely resulting from the expected 5% false positive rate when comparing with the Null distribution.

The flow chart in Fig. 7 shows the data-driven detection process for the candidates of persistent change.

In total, there were 782 physiological parameters that we extracted per day for every user. Due to data availability and user compliance, not all of those were available for every day from the baseline to the end of the study window time span. Considering physiological parameter availability (compliance) of 60% and above for the baseline and the study windows, physiological parameters with persistent changes post-acute infection during the study window for each user are identified. Among the physiological parameters showing persistent changes during the study window, we leveraged a statistical principle to classify the study window observation as either persistent or non-persistent change. We use a statistical approach to determine a threshold for classifying every user’s observation during the study window. This threshold is derived from a binomial distribution, which models the number of positive outcomes (i.e., physiological parameters with persistent changes) expected by random chance. Binomial distribution is employed to calculate a threshold that represents the number of physiological parameters with persistent changes needed to consider an observation significantly positive, given a predefined false positive rate of 5%. Given the probability mass function of the binomial distribution and \(\:n\) as the number of identified persistent physiological parameters, \(\:k\) is calculated so that chance reaches or exceeds 5% chance.

Symptom prevalence analysis

To test whether the “persistent-change” group identified purely from wearable data also showed a higher prevalence of self-reported symptoms, we compared weekly symptom prevalence between the COVID positive and COVID positive with persistent change groups during the five-week interval used for physiological assessment (study window, weeks 4–8 after the test date). Each daily survey captured the presence/absence of CDC-listed symptoms (Supplementary Note 6). For every participant and every week during the study window, we created a binary variable: symptom = 1 if ≥ 1 symptom was reported on any day of that week, otherwise 0. Thus, each participant contributed one independent observation per week. For each week, we constructed a 2 × 2 contingency table (group × symptom presence) and applied Fisher’s exact test (two-sided). Family-wise Type-I error across the weekly tests was controlled with Holm adjustment. We additionally pooled weeks 4–8 into a single table to obtain a more precise risk estimate for “any symptom during the study window”.

Monte Carlo analysis for comparison of prevalence rates

To evaluate whether the prevalence of persistent physiological changes observed in COVID-19 positive subjects was significantly different from what might be expected by chance, we performed a Monte Carlo simulation using COVID-19 negative cohorts as a reference.

To provide a comparison between the positive and negative cohorts, we conducted 1,000 Monte Carlo simulations using data from the COVID-19 negative cohort. Given N subjects in the COVID positive cohort, in each simulation, we randomly selected N subjects in the COVID negative cohort and applied the same compliance criteria (60% and more available nightly measurements per physiological parameter). By comparing the observed prevalence rate in the COVID-19 positive group to the distribution of rates obtained through these simulations, we were able to assess whether the observed rate of persistent changes was significantly elevated beyond what might be expected by random variation in the negative cohort.

Risk analysis using logistic regression

We performed a logistic regression to assess the association between various risk factors and persistent physiological changes in COVID-19 positive subjects. The model included sex, age group, vaccination status (none or 1 or more doses), and weight category as covariates. The outcome variable was the detection of subject with chronic persistent changes post-infection.

Data availability

The datasets generated and/or analyzed during the current study are not publicly available due it being USA controlled unclassified information. Data may be made available by contacting the sponsoring organization, Defense Threat Reduction Agency (email: dtra-joc@mail.mil), please reference project CB10763. Please note the requesting organization will need to have a valid need to know to have the data be made available.

Code availability

The underlying code for this study is not publicly available for proprietary reasons.

References

Nalbandian, A. et al. Postacute COVID-19 syndrome. Nat. Med. 27, 601–615 (2021).

Lu, S. et al. Early biological markers of postacute sequelae of SARSCoV-2 infection. Nat. Commun. 15, 7466 (2024).

Pavli, A., Theodoridou, M. & Maltezou, H. C. PostCOVID syndrome: incidence, clinical spectrum and challenges for primary healthcare professionals. Arch. Med. Res. 52, 575–581 (2021).

Davis, H. E., McCorkell, L., Vogel, J. M. & Topol, E. J. Long COVID: major findings, mechanisms and recommendations. Nat. Rev. Microbiol. 21, 133–146 (2023).

Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Clinical overview of long COVID. https://www.cdc.gov/covid/hcp/clinicaloverview/index.html (accessed Sep 2024).

Goldowitz, I. et al. A long COVID Definition: a Chronic, Systemic Disease State with Profound Consequences (National Academies, 2024).

Puntmann, V. O. et al. Longterm cardiac pathology in individuals with mild initial COVID-19 illness. Nat. Med. 28, 2117–2123 (2022).

Raj, S. R. et al. LongCOVID postural tachycardia syndrome: an American autonomic society statement. Clin. Auton. Res. 31, 365–368 (2021).

Davis, H. E. et al. Characterising long COVID in an international cohort: 7 months of symptoms and their impact. EClinicalMedicine 38, 101019 (2021).

Seighali, N. et al. The global prevalence of depression, anxiety and sleep disorder among patients with postCOVID-19 syndrome (long COVID): a systematic review and metaanalysis. BMC Psychiatry. 24, 105 (2024).

Nestor, B. et al. Machine learning COVID-19 detection from wearables. Lancet Digit. Health. 5, e182–e184 (2023).

Alavi, A. et al. Realtime alerting system for COVID-19 and other stress events using wearable data. Nat. Med. 28, 175–184 (2022).

Hirten, R. P. et al. Use of physiological data from a wearable device to identify SARSCoV-2 infection and symptoms and predict COVID-19 diagnosis: observational study. J. Med. Internet Res. 23, e26107 (2021).

Shandhi, M. M. H. et al. A method for intelligent allocation of diagnostic testing by leveraging data from commercial wearable devices: a case study on COVID-19. NPJ Digit. Med. 5, 130 (2022).

Mishra, T. et al. Presymptomatic detection of COVID-19 from smartwatch data. Nat. Biomed. Eng. 4, 1208–1220 (2020).

Quer, G. et al. Wearable sensor data and selfreported symptoms for COVID-19 detection. Nat. Med. 27, 73–77 (2021).

Shapiro, A. et al. Characterising COVID-19 and influenza illnesses in the real world via persongenerated health data. Patterns 2, 100188 (2021).

Natarajan, A., Su, H. W. & Heneghan, C. Assessment of physiological signs associated with COVID-19 measured using wearable devices. NPJ Digit. Med. 3, 156 (2020).

Mason, A. E. et al. Detection of COVID-19 using multimodal data from a wearable device: results from the first tempredict study. Sci. Rep. 12, 3463 (2022).

Leveraging WHOOP technology to predict COVID-19 risk. Available from: https://www.whoop.com/eu/en/thelocker/predict-covid-19-risk/ (accessed Jul 2025).

Xu, S. et al. Translational gaps and opportunities for medical wearables in digital health. Sci. Transl. Med. 14, eabn6036 (2022).

Miller, D. J. et al. Analysing changes in respiratory rate to predict the risk of COVID-19 infection. PLoS One. 15, e0243693 (2020).

Ding, X. et al. Wearable sensing and telehealth technology with potential applications in the coronavirus pandemic. IEEE Rev. Biomed. Eng. 14, 48–70 (2020).

Sun, Y., Vernon, S. D. & Roundy, S. System and method to determine ME/CFS and long COVID disease severity using a wearable sensor. Preprint at https://arxiv.org/abs/2404.04345 (2024).

Stewart, C. et al. Physiological presentation and risk factors of long COVID in the UK using smartphones and wearable devices: a longitudinal, citizenscience, case–control study. Lancet Digit. Health. 6, e640–e650 (2024).

Conroy, B. et al. Realtime infection prediction with wearable physiological monitoring and AI to aid military workforce readiness during COVID-19. Sci. Rep. 12, 3797 (2022).

Wang, C. et al. A randomised, tripleblinded, placebocontrolled clinical trial evaluating immune responses of typhim Vi and PPSV23 vaccines in healthy adults: the PREP study. Vaccine 43, 126292 (2024).

SankeyMATIC. SankeyMATIC diagram builder. https://sankeymatic.com (accessed Apr 2024).

Task Force of the European Society of Cardiology and the North American Society of Pacing and Electrophysiology. Heart rate variability: standards of measurement, physiological interpretation and clinical use. Circulation 93, 1043–1065 (1996).

Radin, J. M. et al. Longterm changes in wearable sensor data in people with and without long COVID. NPJ Digit. Med. 7, 246 (2024).

Mooren, F. C. et al. Autonomic dysregulation in longterm patients suffering from postCOVID-19 syndrome assessed by heart rate variability. Sci. Rep. 13, 15814 (2023).

Marques, K. C., Quaresma, J. A. S. & Falcão, L. F. M. Cardiovascular autonomic dysfunction in long COVID: pathophysiology, heart rate variability and inflammatory markers. Front. Cardiovasc. Med. 10, 1256512 (2023).

Zanin, A. et al. Parasympathetic autonomic dysfunction is more often evidenced than sympathetic autonomic dysfunction in fluctuating and polymorphic symptoms of long COVID patients. Sci. Rep. 13, 8 (2023).

Fedorowski, A. et al. Cardiovascular autonomic dysfunction in postCOVID-19 syndrome: a major healthcare burden. Nat. Rev. Cardiol. 21, 379–395 (2024).

Ayoubkhani, D. et al. Risk of long COVID in people infected with severe acute respiratory syndrome coronavirus 2 after two doses of a coronavirus disease 2019 vaccine: communitybased matched cohort study. Open. Forum Infect. Dis. 9, ofac464 (2022).

Xie, Y., Choi, T. & AlAly, Z. Postacute sequelae of SARSCoV-2 infection in the predelta, delta and Omicron eras. N Engl. J. Med. 391, 515–525 (2024).

OerteltPrigione, S. The influence of sex and gender on the immune response. Autoimmun. Rev. 11, A479–A485 (2012).

GiefingKröll, C., Berger, P., Lepperdinger, G. & GrubeckLoebenstein, B. How sex and age affect immune responses, susceptibility to infections and response to vaccination. Aging Cell. 14, 309–321 (2015).

Acknowledgements

This work is sponsored by the US Department of Defense (DoD), Defense Threat Reduction Agency (DTRA) under contracts HDTRA120C0041 and HDTRA121C0006. The views, opinions and/or findings expressed are those of the author(s) and should not be interpreted as representing the official views or policies of the Department of Defense, the Defense Threat Reduction Agency (DTRA) or the U.S. Government. We appreciate the vision, leadership, and sponsorship from the US Department of Defense and the U.S. Government: Edward Argenta, Christopher Kiley, Mark Wrobel, Katherine Delaveris, John Cusano, and Christopher Turner.

Funding

This research was developed with funding from the Defense Threat Reduction Agency (DTRA), under contract HDTRA121C0006. The views, opinions, and/or findings expressed are those of the author(s) and should not be interpreted as representing the official views or policies of the Department of Defense or the U.S. Government.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

SB: Conceptualization, Writing – review & editing, Writing – original draft, Visualization, Validation, Supervision, Methodology, Investigation, Formal analysis, Data curation, Conceptualization. IS: Conceptualization, Writing – review & editing, Writing – original draft, Visualization, Validation, Supervision, Methodology, Investigation, Formal analysis, Data curation, Conceptualization. RD: Writing – review & editing, Data curation, Software and Feature Pipeline. TF: Writing – review & editing, Supervision, Methodology, Investigation, Conceptualization, Software and Feature Pipeline. CW: Writing – review & editing, Writing – original draft. Luoluo Liu: Writing – review & editing. ES: Data curation, Software and Feature Pipeline; SM: Writing – review & editing, Writing – original draft, Project management. BC: Data curation, Resources, Software and Feature Pipeline, Funding acquisition.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher’s note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Supplementary Information

Below is the link to the electronic supplementary material.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if you modified the licensed material. You do not have permission under this licence to share adapted material derived from this article or parts of it. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Borhani, S., Silva, I., Damiano, R.J. et al. Automatic detection of persistent physiological changes after COVID infection via wearable devices with potential for long COVID management. Sci Rep 15, 29443 (2025). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-15208-0

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-15208-0