Abstract

In the first part of this study, magnetic nanoparticles were decorated with folic acid (Vitamin B9) under ultrasonic agitation in water, resulting in heterogeneous nano-biocatalysts (FA@γ-Fe2O3), which were characterized using different techniques, such as VSM, FT-IR, and FESEM. The efficiency of the as-prepared magnetic nanocatalyst was assessed in the synthesis of quinoxaline derivatives. In the second part, a Cu (II) folic acid complex was used for modifying the surface of γ-Fe2O3 (FA-Cu@γ-Fe2O3). It was used successfully in several different transformations in a one-pot reaction sequence, including the aerobic oxidation of benzylic alcohols to aldehydes and the tandem synthesis of benzimidazoles through the dehydrogenative coupling of primary benzylic alcohols and aromatic diamines. The biocatalysts maintained their efficiency and structural integrity after 4 runs, which confirmed that components are firmly bonded. The advantages of these catalytic systems include easy separation and reusability of the solid catalyst for subsequent rounds of reactions with an external magnet, demonstrating great potential for practical applications.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Nowadays, the advancement of catalytic technologies towards sustainable approaches for converting raw materials into valuable chemical products, high-value building blocks, and industrial applications is a major challenge that needs to be urgently addressed due to growing environmental concerns. Achieving green chemistry goals provides strong motivation and essential tools for improving environmental and economic issues1,2,3. Therefore, the synthesis of available, active, multi-purpose, and safe catalysts is a great goal for researchers4,5,6,7,8,9. In addition, catalytic protocols for achieving these goals should have environmentally compatible synthetic routes that are energy- and cost-efficient and operationally simple. Achieving green chemistry goals requires the use of environmentally friendly materials, mild reaction conditions, and cost and labor-saving measures, which have led to an increasing use of biocatalysts in industrial environments10. Due to the vital importance of vitamins as essential organic molecules, this category of compounds is of great interest. Vitamins can act as coenzymes, antioxidants, hormones, and active carriers in oxidation-reduction reactions such as electron transfer11,12. Also, vitamins are organic molecules containing a variety of functional groups, such as carboxyl (-COOH), amino (-NH2), and hydroxyl (-OH) groups. Their rich coordination chemistry (through the carboxylate, amino, hydroxyl groups and side chains) makes them an attractive class of organic ligands for the preparation of metal complexes. So, the researchers, considering the ability of vitamins to bind the metal in monodentate, bidentate, bidentate bridging, and tridentate-bridging coordination modes, have chosen these molecules as ligands to design novel metal complexes for biological and medical applications13,14,15,16,17,18.

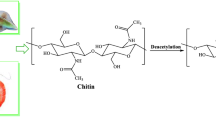

Among different vitamines, the B-group vitamins exhibit a broad spectrum of biochemical and medicinal properties in numerous studies19,20. Folic acid, a B vitamin known as vitamin B9, is a biocompatible molecule found in various foods and often consumed as a dietary supplement. The folate form of folic acid has been utilized in targeted drug delivery strategies for the imaging and elimination of tumors in cells that overexpress the folate receptor21,22,23. The molecular structure of folic acid, which consists of p-aminobenzoic acid, pteridine, and glutamic acid, renders it slightly soluble in water at neutral pH24,25. The unique chemical properties of folic acid make it a valuable tool in various biomedical applications, including drug delivery and imaging, and its compatibility synthesis conditions provide an opportunity for its integration into metal-organic frameworks for potential applications in catalysis and gas storage26. The structural diversity observed in metal complexes of folic acid can be attributed to the various modes of binding of the carboxylate groups of folic acid, which can act as either bidentate or monodentate ligands27,28,29,30,31,32.

Following our research on the development of novel strategies for organic transformation by biocatalysts16,17,18,33, we have developed green, cost-effective, and easily synthesized biocatalysts for organic reactions. These were achieved by immobilizing folic acid on iron oxide nanoparticles. To improve the catalytic properties of the biocatalyst, we incorporated a simple and readily available Cu (OAC)2 compound into folic acid-coated γ-Fe2O3 nanoparticles under ultrasonic agitation, resulting in a novel heterogeneous biocatalyst. This study presents practical and efficient synthesis methods that employ Folic acid-derived catalysts to facilitate the production of biologically significant such as quinoxaline derivatives, and one-pot synthesis of benzimidazoles under solvent-free conditions. (Scheme 1).

Quinoxaline derivatives are important in industry due to their ability to inhibit the metal corrosion34,35,36, in the preparation of the porphyrins, since their structure is similar to the chromophores in the natural system, and also in the electroluminescent materials37,38,39. In pharmacological industry, they have absorbed a great deal of attention due to their wide spectrum of biological properties. For example, they can be used against bacteria, fungi, virus, leishmania, tuberculosis, malaria, cancer, depression, and neurological activities, among others. The quinoxaline structural nucleus renders all these activities possible.

Similarly, benzimidazoles are heterocyclic compounds renowned for their diverse biological activities, including antimicrobial, antifungal, antiviral, and anticancer properties40,41.

Results and discussion

Catalyst fabrication and structural analysis

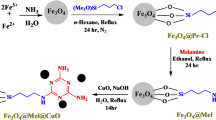

Initially, γ-Fe2O3 was prepared according to previous reports42. Then, an aqueous solution of folic acid was gradually added to γ-Fe2O3 nanoparticles dispersed in deionized (DI) water under ultrasonic agitation (FA@γ-Fe2O3). The desired Cu-containing catalyst (FA-Cu@ γ-Fe2O3) was prepared by the addition of Cu (OAc)2 to FA@γ-Fe2O3 nanohybride under ultrasonic agitation (Scheme 2, for experimental details, see the supporting information).

Comparative FT-IR spectra of γ-Fe2O3, FA@γ-Fe2O3, and FA-Cu@ γ-Fe2O3 biocatalyst depicted in Fig. 1, confirm FA coated γ-Fe2O3 and the complexation of Cu(II) with FA coated γ-Fe2O3. As depicted in Fig. 1, all of the samples show a broad peak at around 3200–3600 cm−1 corresponding to the hydroxyl groups. The bands in the region of 588 and 637 cm−1 are attributed to the stretching vibrations of Fe–O groups Fig. 1a, c, and d).

The FT-IR spectrum of the folic acid (Fig. 1b) reveals the presence of major bands at 1193, 1485, and 1607 cm−1, attributed to the stretching vibrations of C − N groups and C = C bonds in aromatic rings, respectively. Also, the weak peak at 1640 cm−1 is related to the stretching vibration of C = N and the strong peak at 1695 cm−1 is related to the stretching vibration of carbonyl amide and acidic groups. The broad peak in the area of 3400–2400 cm−1 is assigned to the O-H stretching vibration of acidic groups while, the peaks at 3325, 3416 and 3545 cm−1 are related to the amine and amide N-H stretching vibrations in the structure of folic acid43,44.

Besides, characteristic peaks of γ-Fe2O3 and folic acid appeared in Fig. 1c and d, confirm their presence in the as-prepared composites.

The XRD patterns of the γ-Fe2O3 and FA-Cu@ γ-Fe2O3 biocatalyst are shown in Fig. 2A. The obvious diffraction peaks at 2ϴ values of 30.3°, 35.7°, 43.4°, 53.9°, 57.4° and 63.7° were corresponded to (220), (311), (400), (422), (511), and (440), planes of γ-Fe2O3, clearly suggest that γ-Fe2O3 can be assigned to maghemite phase (JCPDS no. 39-1346) (Fig. 2A-a)42. The same XRD patterns of the samples confirmed that γ-Fe2O3 preserved its crystalline structure during surface modification.

To investigate the thermal behavior of the biocatalyst, thermogravimetric analysis (TGA) was performed. The TGA curve, shown in Fig. 2B, reveals two distinct stages. The first one occurring between 50 and 160 °C corresponds to the evaporation of adsorbed water. The second stage spanning from 160 to 680 °C is associated with the breakdown of the folic acid-γ-Fe2O3 complex followed by decomposition of folic acid. (Fig. 2B)

The magnetic property of FA-Cu@ γ-Fe2O3 biocatalyst was investigated by vibrating sample magnetometer (VSM) at room temperature. Based on Fig. 2C, the saturation magnetization (MS) quantities for γ-Fe2O3, FA@γ-Fe2O3, and FA-Cu@ γ-Fe2O3 biocatalyst are 70.4, 35.03 and 34.98 emu/g, respectively. The saturation magnetization of the FA-Cu γ-Fe2O3 biocatalyst was lower than that of the uncoated γ-Fe2O3 nanoparticle due to the diamagnetic effect of the organic group, which resulted in a lower mass fraction of the magnetic substance. Nevertheless, the solid could still be easily isolated from the solution using a permanent magnet.

The scanning electronic microscopy (SEM) images of FA@γ-Fe2O3 and FA-Cu@ γ-Fe2O3 nanohybride (Fig. 3a, b) displayed the sphere-like morphology with the size of 19–38 nm 12–32 nm, respectively.

The energy-dispersive X-ray spectroscopy (EDX) indicated composed elements of biocatalyst including Fe, N, C, O and Cu, as expected (Fig. 3 C). The copper content of the biocatalyst was determined to be 2.75 mmolg−1 using inductively coupled plasma atomic emission spectroscopy (ICP-OES).

Catalytic activity

The catalytic activity of FA@γ-Fe2O3 nano biocatalyst in the synthesis of quinoxalines and pyrido pyrazines

The catalytic potential of the as-prepared FA@γ-Fe2O3 nanohybrid as a green biocatalyst was assessed in the synthesis of quinoxalines. At the outset, 4, 4’-dimethoxybenzil (0.125 mmol, 0.03 g) and o-phenylenediamine (0.15 mmol, 0.016 g) were selected as model substrates to optimize the synthesis conditions (Table 1). The catalytic efficiency of FA@γ-Fe2O3 nanohybrid was tested in a range of solvents including EtOH, H2O, EtOAc, MeCN, and under solvent-free condition and the highest product yield was obtained in EtOH. The effect of temperature was investigated, and the best efficiency was obtained at 60 °C. It was also found that 2 mg of catalyst is enough to drive the reaction with high performance.

To clarify that the FA@γ-Fe2O3 nanohybrid itself and not its components act as an effective catalyst, it was replaced by material precursors with respect to the catalyst composition. The quinoxaline yield decreased to 75 and 55% in the presence of folic acid and γ-Fe2O3 respectively, under the optimized conditions after 60 min (Fig. 4).

After establishing the optimized reaction conditions for the synthesis of quinoxalines, the substrate scope of this transformation was studied. The electron-withdrawing groups on the phenyl ring in diamine derivatives (Table 2, entries 3c, 3e and 3g), as well as electron-donating groups on the phenyl ring in diketone derivatives (Table 2, entries 3d, 3e and 3i), reduce the reaction rate. Additionally, applying similar reaction conditions to the condensation of 5-bromo-2,3-diaminopyridine and various 1,2-diketones for the synthesis of pyrido[2,3-b] pyrazines resulted in high yields of the desired products (Table 2, entries 3h, 3i and 3j). As anticipated, condensation reactions involving 5-bromo-2,3-diaminopyridine with dicarbonyl compounds required longer reaction times compared to aryl 1,2-diamines.

The catalytic activity of FA-Cu@γ-Fe2O3 nano biocatalyst in the aerobic oxidation of benzyl alcohols

We began our studies using 4-chlorobenzyl alcohol (0.125 mmol) as a model substrate to investigate the optimal reaction conditions for the oxidation reaction (Table 3).

A variety of solvents including H₂O, EtOAc, MeCN, EtOH as well as solvent-free conditions, were examined, with the solvent-free setup proving to be the most optimal for this reaction. By decreasing the reaction temperature from 80 to 25 °C, the conversion of the oxidation of 4-chlorobenzyl alcohol reduced from 97 to 13%. The catalyst concentration was also screened. The increase in catalyst loading from 1 to 2 mg at 80 °C promoted the yield of the oxidation product from 40 to 60% after 180 min. Among the radical generators examined in this work, TEMPO was a superior choice. Increasing the concentration of TEMPO from 1 to 3 mg increased the oxidation yield from 30 to 97%, while further increases reduced the yield. The effect of the oxidant nature was also investigated, and the result was interesting. The lower yield of the oxidation product was achieved in the presence of O2, UHP, H2O2, TBHP, TBAOX, and Oxone. Thus, to reach the highest performance, the reaction needs air and 3 mg catalyst and 3 mg TEMPO under solvent-free conditions at 80 °C.

With the optimal reaction conditions in hand, the substrate scope was investigated. A number of aromatic benzyl alcohols with electronic requirements were examined. Benzyl alcohols substituted with electron-releasing groups demonstrated an increased conversion rate (Table 4, entries 2e, 2f, 2i, and 2k), while those substituted with electron-withdrawing groups exhibited a decreased conversion in a longer reaction time (Table 4, entries 2g, 2h).

As shown in Table 4, secondary benzylic alcohols such as 1-phenylethanol, diphenylmethanole and 1,2,3,4-Tetrahydronaphthalen-1-ol were successfully converted into their corresponding ketones (Table 4, entries 2l, 2m and 2n), achieving a moderate yield.

To evaluate the efficiency of the catalytic system turnover number (TON) was determined under a saturation regime of the reactants (10 folds 4-chlorobenzyl alcohol (1.25 mmol) with the constant catalyst loading of 8.25 µmol)50. The catalyst exhibited a turnover frequency (TOF) of 45 h⁻¹ and TON of 106, indicating of an efficient catalytic performance with sustained activity and a moderate reaction rate.

The catalytic activity of FA-Cu@γ-Fe2O3 biocatalyst in aerobic tandem synthesis of benzimidazoles using benzyl alcohols

First, we evaluated the catalytic efficiency of the FA-Cu@γ-Fe2O3 γbiocatalyst in comparison with individual components and precursor materials, namely γ-Fe2O3, folic acid, the FA@γ-Fe2O3 nanohybrid, and Cu(OAc)2 under optimized reaction conditions (Fig. 5). As illustrated in Fig. 5, FA-Cu@γ-Fe2O3 demonstrated superior catalytic performance in the synthesis of a benzimidazole derivative from 4-chlorobenzyl alcohol and 1,2-phenylenediamine, outperforming all other tested catalysts. This could be due to the oxidative activity of Cu(II) centers combined with the catalytic activity of the folic acid and γ-Fe2O3, which acts as a support.

To broaden the scope of the current catalytic system, the catalytic potential of the FA-Cu@γ-Fe2O3 nano biocatalyst was utilized for the one-pot synthesis of various biologically significant benzimidazoles using benzyl alcohols as starting materials. After completing the oxidation of alcohols (0.125 mmol) under optimized conditions obtained in the previous section, 1,2-phenylenediamine (0.15 mmol) was added to produce benzimidazoles. The results in Table 5 show that benzylic alcohols with electron-donating groups (Table 5, entries 3e, 3f, 3i, and 3k) produce the desired products with better efficiency than those bearing electron-withdrawing groups (Table 5, entreis 3g, and 3h).

Recycling experiments

The stability and reusability of the FA@γ-Fe2O3 and FA-Cu@γ-Fe2O3 biocatalysts were assessed over 4 runs (Fig. 6) in mentioned reactions. At each run’s end, an external magnet separated the catalyst from the reaction solution. A new batch of synthesis reaction was initiated using the separated nanohybrids, which were repeated for up to four runs. A slight reduction in product yields was observed after the 4th run, indicating the efficiency and reusability of the catalyst (Fig. 6). An FT-IR spectral analysis was performed on the recovered catalyst from the model reactions to document its stability, as illustrated in Figure S1. Further, the copper content of the used catalyst determined by ICP-OES analysis was found to be 2.63 mmolg−1 indicating minor leaching (4.3%) of copper during the reaction. These findings confirmed that FA@γ-Fe₂O₃ and Cu are firmly bonded.

Recycling of catalytic system for (a) the condensation 4, 4’-dimethoxybenzil (0.125 mmol) and o-phenylenediamine (0.15 mmol) using FA@γ-Fe2O3 nanohybrid (b) the aerobic oxidation of 4-chlorobenzyl alcohol (c) the condensation 4-chlorobenzyl alcohol (0.12 mmol), 1,2-phenylene diamine using FA-Cu @γ-Fe2O3 biocatalyst according to procedures mentioned in the experimental section.

Conclusion

In this study, magnetically separable biocatalysts FA@γ-Fe2O3 and FA-Cu @γ-Fe2O3 were fabricated using folic acid as a bio-ligand in water as a green solvent under ultrasonic agitation. In the first part, the efficiency of FA@γ-Fe2O3 was evaluated in the synthesis of quinoxaline derivatives. In the second part, the surface of γ-Fe2O3 modified with a Cu (II) folic acid complex under ultrasonic agitation in water (FA-Cu@γ-Fe2O3). The as-prepared magnetic nanocomplex of FA-Cu @γ-Fe2O3 successfully derived several important processes, including aerobic oxidation of benzylic alcohols to aldehydes and then the tandem synthesis of benzimidazoles through the dehydrogenative coupling of primary benzylic alcohols with aromatic diamines under solvent-free conditions. Further advantages of our work are minimizing waste, synthesizing the biocatalysts in water as an environmentally friendly solvent under ultrasonic agitation, and conducting the reaction in a solvent-free environment. These aspects demonstrate that our approach is atom-efficient and aligns with the principles of green chemistry. This strategy creates new opportunities to fabricate natural-based multi-purpose catalysts for synchronous eco-friendly processes.

Experimental section

Synthesis of Catalyst. The detailed step-by-step preparation of the FA@γ-Fe2O3 and FA-Cu@ γ-Fe2O3 biocatalysts and the experimental procedures are provided in the supporting information.

Data availability

Data is provided within the manuscript or supplementary information files.

References

O’Neil, N. J. et al. Approaches to incorporating green chemistry and safety into laboratory culture. J. Chem. Educ. 98, 84–91 (2020).

Sheldon, R. A. & Brady, D. Green chemistry, biocatalysis, and the chemical industry of the future. ChemSusChem 15, e202102628 (2022).

Alcántara, A. R. et al. Biocatalysis as key to sustainable industrial chemistry. ChemSusChem 15, e202102709 (2022).

Swinnen, S., de Azambuja, F. & Parac-Vogt, T. N. From nanozymes to Multi‐Purpose nanomaterials: the potential of Metal–Organic frameworks for proteomics applications. Adv. Healthc. Mater. 14, 2401547 (2025).

Tamoradi, T. et al. Synthesis of pomegranate Peel extract functionalized magnetic graphene oxide: production of biodiesel and quantitative determination of harmful organic colorant in environmental waters. J. Phys. Chem. Solids. 183, 111566 (2023).

Tamoradi, T. et al. A competent, atom-efficient and sustainable synthesis of bis-coumarin derivatives catalyzed over strontium-doped asparagine modified graphene oxide nanocomposite. Polycycl. Aromat. Compd. 42, 7267–7281 (2022).

Veisi, H. et al. Au NPs fabricated on biguanidine-modified Zr-UiO-66 mofs: a competent reusable heterogeneous nanocatalyst in the green synthesis of propargylamines. New. J. Chem. 46, 2829–2836 (2022).

Tamoradi, T. et al. Transesterification of rapeseed oil and waste corn oil toward the production of biodiesel over a basic high surface area magnetic nanocatalyst: application of the response surface methodology in process optimization. New. J. Chem. 45, 21116–21124 (2021).

Veisi, H., Tamoradi, T., Rashtiani, A., Hemmati, S. & Karmakar, B. Palladium nanoparticles anchored polydopamine-coated graphene oxide/Fe3O4 nanoparticles (GO/Fe3O4@ PDA/Pd) as a novel recyclable heterogeneous catalyst in the facile cyanation of haloarenes using K4 [Fe (CN) 6] as cyanide source. J. Ind. Eng. Chem. 90, 379–388 (2020).

Ye, L., Yang, C. & Yu, H. From molecular engineering to process engineering: development of high-throughput screening methods in enzyme directed evolution. Appl. Microbiol. Biotechnol. 102, 559–567 (2018).

Dewangan, S. & Bhatia, A. K. Vitamins and metabolites. In Handbook of Biomolecules (eds Verma, Ch. & Verma, D. K.) 119–131 (Elsevier, 2023).

Fernández-Villa, D. et al. Tissue engineering therapies based on folic acid and other vitamin B derivatives. Functional mechanisms and current applications in regenerative medicine. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 19, 4068 (2018).

Bagheri, S. et al. Synthesis and characterization of Pd (II)–vitamin B6 complex supported on magnetic nanoparticle as an efficient and recyclable catalyst system for C–N cross coupling of amides in deep eutectic solvents. Appl. Organomet. Chem. 34, e5723 (2020).

Rafiee, F., Abbaspour, M. & Ziarani, G. M. Immobilization of vitamin B1 on the magnetic dialdehyde starch as an efficient carbene-type support for the copper complexation and its catalytic activity examination. React. Funct. Polym. 170, 105106 (2022).

Shaterian, H. R. & Molaei, P. Fe3O4@ vitamin B1 as a sustainable superparamagnetic heterogeneous nanocatalyst promoting green synthesis of trisubstituted 1, 3-thiazole derivatives. Appl. Organomet. Chem. 33, e4964 (2019).

Rostaminasab, M. et al. Magnetic thiaminum octamolybdate nanocatalyst for oxygenation of styrenes to benzaldehydes and tandem synthesis of benzimidazoles. ACS Appl. Nano Mater. 6, 22459–22470 (2023).

Rezapour, E., Jafarpour, M. & Rezaeifard, A. Palladium niacin complex immobilized on starch-coated maghemite nanoparticles as an efficient homo-and cross-coupling catalyst for the synthesis of symmetrical and unsymmetrical biaryls. Catal. Lett. 148, 3165–3177 (2018).

Zamenraz, S. et al. Vitamin B5 copper conjugated triazine dendrimer improved the visible-light photocatalytic activity of TiO2 nanoparticles for aerobic homocoupling reactions. Sci. Rep. 14, 2691 (2024).

Malik, D. et al. Water-Soluble Vitamins (Authors and Editors). In Textbook of Nutritional Biochemistry 291–389 (Singapore, 2023).

Kennedy, D. O. B vitamins and the brain: mechanisms, dose and efficacy—a review. Nutrients 8, 68 (2016).

Bonetti, F., Brombo, G. & Zuliani, G. The role of B group vitamins and choline in cognition and brain aging. In Nutrition and Functional Foods for Healthy Aging (ed Watson, R. R.) 139–158 (Academic Press, 2017).

Fernández, M., Javaid, F. & Chudasama, V. Advances in targeting the folate receptor in the treatment/imaging of cancers. Chem. Sci. 9, 790–810 (2018).

Fatima, M. et al. Folic acid conjugated Poly (amidoamine) dendrimer as a smart nanocarriers for tracing, imaging, and treating cancers over-expressing folate receptors. Eur. Polym. J. 170, 111156 (2022).

Cieślik, E. & Cieślik, I. Occurrence and significance of folic acid. Pteridines 29, 187–195 (2018).

Premjit, Y., Pandey, S. & Mitra, J. Recent trends in folic acid (vitamin B9) encapsulation, controlled release, and mathematical modelling. Food Rev. Int. 39, 5528–5562 (2023).

Abazari, R. et al. A luminescent amine-functionalized metal–organic framework conjugated with folic acid as a targeted biocompatible pH-responsive nanocarrier for apoptosis induction in breast cancer cells. ACS Appl. Mater. Interfaces. 11, 45442–45454 (2019).

de Sousa, M. et al. Folic-acid-functionalized graphene oxide nanocarrier: synthetic approaches, characterization, drug delivery study, and antitumor screening. ACS Appl. Nano Mater. 1, 922–932 (2018).

Birlik Demirel, G. et al. Folic acid-conjugated pH and redox-sensitive ellipsoidal hybrid magnetic nanoparticles for dual-triggered drug release. ACS Appl. Bio Mater. 3, 4949–4961 (2020).

Das, S. et al. Enhancement of energy storage and photoresponse properties of folic acid–polyaniline hybrid hydrogel by in situ growth of ag nanoparticles. ACS Appl. Mater. Interfaces. 8, 28055–28067 (2016).

Roy, S. et al. Electroactive and high dielectric folic acid/pvdf composite film rooted simplistic organic photovoltaic self-charging energy storage cell with superior energy density and storage capability. ACS Appl. Mater. Interfaces. 9, 24198–24209 (2017).

He, C. et al. Palladium and platinum complexes of folic acid as new drug delivery systems for treatment of breast cancer cells. J. Mol. Struct. 1229, 129806 (2021).

Abd El-Wahed, M. G. et al. Synthesis, spectroscopic and thermal characterization of some transition metal complexes of folic acid. Spectrochimica Acta Mol. Biomol. Spectrosc. 70, 916–922 (2008).

Pourmorteza, N. et al. Cu(II)–vitamin C-complex catalyzed photo-induced homocoupling reaction of Aryl boronic acid in base-free and visible light conditions. RSC Adv. 12, 493 (2022). (also see references there).

Khatoon, H. & Faudzi, S. M. M. Exploring Quinoxaline derivatives: an overview of a new approach to combat antimicrobial resistance. Eur. J. Med. Chem. 276, 116675 (2024).

Chauhan, D. S., Singh, P. & Quraishi, M. A. Quinoxaline derivatives as efficient corrosion inhibitors: current status, challenges and future perspectives. J. Mol. Liq. 320, 114387 (2020).

Sharma, A., Deep, A., Marwaha, M. G., Marwaha, R. K. & Quinoxaline A chemical moiety with spectrum of interesting biological activities. Mini Rev. Med. Chem. 22, 927–948 (2022).

Sharma, G. Synthesis of Quinoxaline quinines and regioselectivity in their diels-Alder cycloadditions. Indian J. Chem. B. 48, 1590–1596 (2009).

Justin Thomas, K. R. et al. Chromophore-labeled Quinoxaline derivatives as efficient electroluminescent materials. Chem. Mater. 17, 1860–1866 (2005).

Chang, D. W. et al. Multifunctional Quinoxaline containing small molecules with multiple electron-donating moieties: solvatochromic and optoelectronic properties. Synth. Met. 162, 1169–1176 (2012).

Aroua, L. M. et al. Benzimidazole (s): synthons, bioactive lead structures, total synthesis, and the profiling of major bioactive categories. RSC Adv. 15, 7571–7608 (2025).

Kabi, A. K. et al. An overview on biological activity of benzimidazole derivatives. In Nanostructured Biomaterials: Basic Structures and Applications (ed Swain, B. P.) 351–378 (2022).

Tang, B. Z. et al. Processible nanostructured materials with electrical conductivity and magnetic susceptibility: Preparation and properties of maghemite/polyaniline nanocomposite films. J. Mater. Chem. 11, 1581–1589 (1999).

Freitas, L. B. D. O. et al. Mesoporous silica materials functionalized with folic acid: preparation, characterization and release profile study with methotrexate. J. Solgel Sci. Technol. 77, 186–204 (2016).

Venkatasubbu, G. D. et al. Surface modification and Paclitaxel drug delivery of folic acid modified polyethylene glycol functionalized hydroxyapatite nanoparticles. Powder Technol. 235, 437–442 (2013).

Jafarpour, M., Rezaeifard, A. & Danehchin, M. Easy access to Quinoxaline derivatives using alumina as an effective and reusable catalyst under solvent-free conditions. Appl. Catal. A. 394, 48–51 (2011).

Bardajee, G. R. et al. Palladium Schiff-base complex loaded SBA-15 as a novel nanocatalyst for the synthesis of 2, 3-disubstituted quinoxalines and pyridopyrazine derivatives. Microporous Mesoporous Mater. 169, 67–74 (2013).

Kumbhar, A. et al. Brönsted acid hydrotrope combined catalyst for environmentally benign synthesis of quinoxalines and pyrido [2, 3-b] pyrazines in aqueous medium. Tetrahedron Lett. 53, 2756–2760 (2012).

Tamuli, K. J., Nath, S. & Bordoloi, M. In water organic synthesis: introducing Itaconic acid as a recyclable acidic promoter for efficient and scalable synthesis of Quinoxaline derivatives at room temperature. J. Heterocycl. Chem. 58, 983–1002 (2021).

Kolvari, E., Zolfigol, M. A., Koukabi, N., Gilandust, M. & Kordi, A. V. Zirconium triflate: an efficient catalyst for the synthesis of Quinolines and quinoxalines. J. Iran. CHEM. SOC. 10, 1183–1191 (2013).

Kozuch, S. & Martin, J. M. L. Turning over definitions in catalytic cycles. ACS Catal. 2, 2787–2794 (2012).

Hanson, S. K., Wu, R. & Silks, L. P. Mild and selective vanadium-catalyzed oxidation of benzylic, allylic, and propargylic alcohols using air. Org. Lett. 13, 1908–1911 (2011).

Landers, B. et al. N-Heterocyclic Carbene)-Pd-Catalyzed anaerobic oxidation of secondary alcohols and domino oxidation – Arylation reactions. J. Org. Chem. 76, 1390–1397 (2011).

Gawande, M. B. et al. A recyclable ferrite-Co magnetic nanocatalyst for the oxidation of alcohols to carbonyl compounds. ChemPlusChem 77, 865–871 (2012).

Hasanpour, B. et al. A Star-Shaped Triazine‐Based vitamin B5 copper (II) nanocatalyst for tandem aerobic synthesis of Bis (indolyl) methanes. Eur. J. Org. Chem. 2020, 4122–4129 (2020).

Jafarpour, M. et al. Reusable α-MoO3 nanobelts catalyzes the green and heterogeneous condensation of 1, 2-diamines with carbonyl compounds. New. J. Chem. 37, 2087–2095 (2013).

Abdi, B. et al. TiO2/AgSbO3 nanophotocatalyst with improved photocatalytic performance in the synthesis of some benzimidazole derivatives. J. Mol. Struct. 1321, 140037 (2025).

An, W. K. et al. s-Tetrazine-functionalized hyper-crosslinked polymers for efficient photocatalytic synthesis of benzimidazoles. Green. Chem. 23, 1292–1299 (2021).

Badawy, M. A. et al. Design, synthesis, biological assessment and in Silico ADME prediction of new 2-(4-(methylsulfonyl) phenyl) benzimidazoles as selective cyclooxygenase-2 inhibitors. RSC Adv. 11, 27659–27673 (2021).

Mirfarjood, S. A., Mamaghani, M. & Sheykhan, M. Copper-incorporated fluorapatite encapsulated iron oxide nanocatalyst for synthesis of benzimidazoles. J. Nanostructure Chem. 7, 359–366 (2017).

Acknowledgements

Support for this work from the Research Council of Bu-Ali Sina University and the University of Birjand is greatly appreciated.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

(1) M. J. (corresponding author) Funding acquisition, Supervision, Conceptualization, Resources, Writing-review & editing (2) A.R. Interpretation of some analysis and results, editing the final draft (3) N. P. Synthesis, Methodology, and preparation of original draft4. R. Gh. Synthesis, Analysis, Methodology; 5. F. S. Synthesis, Analysis, Methodology.

Corresponding authors

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher’s note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Supplementary Information

Below is the link to the electronic supplementary material.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if you modified the licensed material. You do not have permission under this licence to share adapted material derived from this article or parts of it. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Jafarpour, M., Rezaeifard, A., Pourmorteza, N. et al. Magnetic nanohybrids of folic acid as green biocatalysts for the synthesis of heterocyclic compounds. Sci Rep 15, 31038 (2025). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-15308-x

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-15308-x