Abstract

Obesity is closely related to liver disease. However, few studies have focused on the impact of adipose tissue-derived extracellular vesicles (EVs) in obesity on liver disease. Therefore, we aimed to investigate the effect of adipose tissue-derived EVs from high-fat diet (HFD)-fed obese mice (EV-HFD) on liver damage induced by oxidative stress. We investigated alterations in the expression of antioxidant enzymes in adipose tissue, and the loading of those enzymes into adipose tissue-derived EVs. Furthermore, we treated alpha mouse liver 12 (AML12) cells with adipose tissue-derived EVs and induced oxidative stress. We observed that the HFD did not exert an effect on the protein expressions of antioxidant enzymes in adipose tissue. Intriguingly, the EV-HFD exhibited an upregulation in the loading of catalase (CAT) when compared to the adipose tissue-derived EVs from normal chow-fed mice (EV-NC). Notably, both types of EVs exhibited a similar capacity to mitigate cell damage when exposed to oxidative stress. Our findings indicate that obesity-induced loading of more CAT into adipose tissue-derived EVs cannot improve their antioxidant capacity in AML12 cells. We suggest that adipose tissue-derived EVs can serve as a tool to maintain homeostasis and defend against oxidative stress, thereby supporting normal physiological functions.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Obesity is a chronic disease that occurs when energy intake exceeds energy expenditure over a long period of time1,2. Obesity can increase the risk of chronic diseases, such as type 2 diabetes mellitus, cardiovascular disease, non-alcoholic fatty liver disease, and certain cancers, by exacerbating various pathophysiological processes3,4. It is well known that these obesity-mediated complications are associated with a state of chronic inflammation and oxidative stress caused by the overproduction of reactive oxygen species (ROS) in adipose tissue5. However, findings of previous studies have shown inconsistency in terms of changes observed in antioxidant enzymes, including superoxide dismutase (SOD), catalase (CAT), and glutathione peroxidase (GPx), of adipose tissue in the obese state6,7,8.

The liver plays an important role in lipid metabolism and is affected by obesity9. Individuals with obesity have enlarged adipose tissue and release greater amounts of free fatty acids into the circulation than individual without obesity, resulting in increased uptake of free fatty acids and synthesis of triglycerides that surpass the rates of oxidation and secretion in the liver10,11. The accumulation of lipid droplets in hepatocytes eventually gives rise to hepatic steatosis, which can lead to impaired liver function9. In particular, lipid accumulation in hepatocytes causes mitochondrial dysfunction, which may contribute to ROS production12. Oxidative stress induced by increased levels of intracellular ROS is suggested as a critical factor linking obesity and its related liver diseases5,13,14. Thus, in the context of obesity, dysregulated adipokine production and secretion in distantly located white adipose tissue may contribute to liver disease progression in addition to events occurring in the liver itself. Accumulating evidence demonstrates that adipose tissue-derived extracellular vesicles (EVs) can influence the development of metabolic diseases in individuals with obesity15,16,17,18,19.

EVs are particles released naturally from cells that are delimited by a lipid bilayer and do not contain a functional nucleus20. EVs are classified into exosomes, microvesicles, and apoptotic bodies based on their biogenesis, release route, size, content, and function21. Apoptotic bodies can be engulfed by phagocytes, whereas microvesicles and exosomes can interact with recipient cells by docking at the plasma membrane, fusing directly with the plasma membrane, or being endocytosed. Eventually, proteins, lipids, RNAs, miRNAs, and various bioactive compounds contained in EVs can cause physiological and pathological changes in recipient cells22,23,24. However, because it is experimentally difficult to distinguish their unique physical properties and specific markers, and because they often share similar biosynthetic origins, the collective term ‘EVs’ is widely used25.

While the roles of adipose tissue-derived EVs in metabolic diseases have been increasingly recognized, no study to date has examined changes in antioxidant enzymes within these EVs under obese conditions, nor their effects on oxidative stress in other tissues. Therefore, this study aimed to investigate the changes in antioxidant enzymes within adipose tissue-derived EVs from high-fat diet (HFD)-fed obese mice (EV-HFD) and their effects on oxidative stress-induced liver cells.

Materials and methods

Animals

C57BL/6 N mice (6 weeks old) were obtained from Central Lab Animal Inc. (Seoul, Korea). The mice were maintained under a 12 h light/12 h dark cycle in a controlled environment (23 ± 2 °C and 50 ± 10% relative humidity) with a ventilation rate of 15–20 air changes per hour. After acclimatization for 1 week, the mice were randomly assigned and were then subjected to a normal chow diet (NC, n = 6, 3 mice/cage) or a HFD (n = 6, 3 mice/cage) for 12 weeks. The normal chow diet used in this study was based on the AIN-93G formulation. The HFD consisted of 20% protein, 20% carbohydrate, and 60% fat (kcal%), as described in previous studies26. The HFD was formulated by reducing carbohydrate content and increasing fat content, primarily through the addition of lard and soybean oil. Mice were fed ad libitum, and the diets were not isocaloric. The detailed composition of both diets is provided in Supplementary Table S1. Prior to euthanasia, the mice were fasted for 6 h. Euthanasia was performed by carbon dioxide (CO2) inhalation followed by cervical dislocation after 12 weeks of feeding. The animal study protocol was approved by the Institutional Animal Care and Use Committee of Chonnam National University (CNU IACUC-YB-2021-122), and the animals were maintained in accordance with the “Guidelines for Animal Experiments” established by the university. All animal procedures were conducted in accordance with the ARRIVE guidelines.

Histological observation

The adipose tissue from mice was fixed overnight in 4% paraformaldehyde. After embedding in paraffin, it was cut into thin slices and stained with hematoxylin-eosin (H&E). Images were observed using an IX53 inverted light microscope (Olympus, Tokyo, Japan) and captured with ToupView software for Windows, version 4.8.16295.20200101 (ToupTek, Hangzhou, China; https://www.touptekphotonics.com/). Adipose tissue area was analyzed using ImageJ software version 1.53e (National Institutes of Health, Bethesda, MD, USA).

Serum biochemical analysis

Blood from mice was centrifuged at 1500 × g for 10 min at 4 °C to isolate the serum, which was then stored at − 20 °C. Fasting glucose and total cholesterol levels in mouse serum were measured using commercial assay kits (Biomax) according to the manufacturer’s instructions.

RT-PCR

RNA was extracted from adipose tissue using TRIzol (Invitrogen, Waltham, MA, USA) according to the manufacturer’s instructions. Complementary DNA (cDNA) was synthesized with 100 ng of RNA using the iScript cDNA Synthesis Kit (Bio-Rad, Hercules, CA, USA). The PCR reaction was performed using the iQ SYBR Green Supermix (Bio-Rad, Hercules, CA, USA), 1 µL of cDNA, and the custom-designed primers (Supplementary Table S2). cDNA was amplified by 40 cycles of denaturation (95 °C for 10 s) and annealing/extension (60 °C for 30 s) using the CFX Duet Real-Time PCR System (Bio-Rad, Hercules, CA, USA).

Western blotting

Proteins were extracted using 1X RIPA Lysis Buffer (Rockland, Pottstown, PA, USA) containing protease inhibitor (Thermo Fisher Scientific, Waltham, MA, USA) and phosphatase inhibitor (Thermo Fisher Scientific, Waltham, MA, USA) and were quantified by the Bradford assay. Equal amounts of protein between groups were loaded on a 4−15% SDS-PAGE gel (Bio-Rad, Hercules, CA, USA) and then transferred to a PVDF membrane (Bio-Rad, Hercules, CA, USA). The membrane was blocked with TBST containing 5% skim milk for 1 h at room temperature and then incubated overnight at 4 °C with primary antibodies against CAT, SOD1, Jun N-terminal kinase (JNK), phosphorylated JNK (p-JNK), β-actin (Cell signaling technology, Beverly, MA, USA), GPx1 (Invitrogen, Waltham, MA, USA), and cluster of differentiation 63 (CD63) (Abcam, Cambridge, UK). The membrane was subsequently incubated with HRP-conjugated secondary antibody (Bio-Rad, Hercules, CA, USA) for 1 h at room temperature. Bands were captured using the ChemiDoc Imaging System (Bio-Rad, Hercules, CA, USA) and quantified with ImageJ software version 1.53e (National Institutes of Health, Bethesda, MD, USA).

EVs isolation and analysis

To obtain adipose tissue-derived EVs, epididymal adipose tissue (EAT), visceral adipose tissue (VAT), and subcutaneous adipose tissue (SAT) were surgically isolated from mice, immediately minced into small pieces, and cultured in DMEM supplemented with 10% FBS and 1% penicillin/streptomycin for 48 h. After removing the cultured fat pads, the supernatant was collected and sequentially filtered through 0.45 μm and 0.22 μm filters. Adipose tissue-derived exosomes were isolated from the supernatant using ExoQuick-TC™ (System Biosciences, Palo Alto, CA, USA) according to the manufacturer’s instructions, and are hereafter collectively referred to as adipose tissue-derived EVs. Serum EVs (S/EVs) were immediately isolated from mouse serum using XENO-EVI™ Kit (Xenohelix, Incheon, Korea) according to the manufacturer’s instructions. The purified EVs were then resuspended in 1X PBS and stored at -80 °C. EV size was confirmed using a nanoparticle tracking analysis (NTA) system (Malvern Panalytical Ltd., Malvern, UK). The protein content of the EVs was quantified using the Bradford assay, and the presence of CD63 (Abcam, Cambridge, UK), an EV marker, was confirmed through western blotting.

CAT activity

In the case of EVs, 200 µg of EVs were used. In the case of cells, alpha mouse liver 12 (AML12) cells were seeded in a 6-well plate at a density of 2 × 105 cells/well and were treated with EVs for 24 h. When hydrogen peroxide (H2O2) treatment was required, the cells were additionally treated with 600 µM H2O2 for 2 h. CAT activity was colorimetrically measured using a CAT activity assay kit (Abcam, Cambridge, UK) according to the manufacturer’s instructions.

SOD activity

SOD activity of 200 µg of EVs was measured colorimetrically using the SOD Activity Assay Kit (Abcam, Cambridge, UK) according to the manufacturer’s instructions. SOD activity was evaluated as inhibition rate (%).

GPx activity

GPx activity of 200 µg of EVs was measured colorimetrically using the GPx Activity Assay Kit (Abcam, Cambridge, UK) according to the manufacturer’s instructions.

Cell culture and treatments

AML12 cells were (ATCC, VA, USA) maintained in DMEM supplemented with 10% fetal bovine serum (FBS, Gibco), 1% penicillin-streptomycin (Gibco), 1% insulin-transferrin-selenium (Thermo Fisher Scientific, Waltham, MA, USA), and 40 ng/mL dexamethasone (Sigma–Aldrich, St. Louis, MO, USA). RAW264.7 cells (ATCC, VA, USA), a murine macrophage cell line, were maintained in DMEM supplemented with 10% FBS and 1% penicillin-streptomycin. All cells were incubated at 37 ℃ with 5% CO2. For the treatment assay, cells were treated with 50 µg/mL of EVs for 24 h before being treated with the chemicals.

Chemicals used to induce oxidative stress in AML12 cells were 600 µM H2O2 (Sigma–Aldrich, St. Louis, MO, USA) and 200 µM palmitic acid (PA) (Sigma–Aldrich, St. Louis, MO, USA)-bovine serum albumin (BSA) (Sigma–Aldrich, St. Louis, MO, USA) complex, which were treated for 2 h and 24 h, respectively. For RAW264.7 cells, 800 µM H2O2 was treated for 2 h.

The positive control for inducing an antioxidant reaction in cells used 10 µM ascorbic acid (AA) (Sigma–Aldrich, St. Louis, MO, USA), which was treated for 2 h.

Preparation of PA-BSA complex

The 5% stock solution of BSA was prepared in PBS. PA was dissolved in ethanol to make a 100 mM solution and then mixed in a 1:10 proportion with 5% BSA. The mixture was then heated at 37 °C with shaking for 1 h to create a final 10 mM PA-BSA complex stock solution. This stock solution was then diluted to 200 µM using 5% BSA.

EVs uptake assay

AML12 cells were treated with EVs that had been previously labeled using the ExoGlow-Protein EV Labeling Kit (System Biosciences, Palo Alto, CA, USA). Non-internalized EVs were removed by washing the cells three times with 1X PBS, and the washed cells were fixed with 4% paraformaldehyde for 20 min. After washing, cells were permeabilized with 0.3% Triton X-100 at 4°C for 1 h and washed. Nuclei were labeled using ProLong™ Gold Antifade Mountant with 4’,6-diamidino-2-phenylindole (DAPI, Invitrogen, Waltham, MA, USA). The slide was covered with a cover glass and observed using a fluorescence microscope (OLYMPUS, Tokyo, Japan). Uptaken EVs were quantified using ImageJ software version 1.53e (National Institutes of Health, Bethesda, MD, USA).

Viability assay

Cell viability was evaluated using the water-soluble tetrazolium salt-based EZ-Cytox assay kit (Dogenbio, Seoul, Korea). Briefly, AML12 cells were seeded in a 96-well plate at a density of 1 × 104 cells/well, and EVs were administered. Subsequently, the cells were treated with H2O2 or PA, and the produced formazan was measured by its absorbance at 450 nm.

Intracellular ROS measurement

ROS levels were determined using the Cellular ROS Assay kit (Abcam, Cambridge, UK). Briefly, AML12 cells were seeded in a 96-well plate at a density of 1 × 104 cells/well. EVs were treated for 24 h, and the ROS red working solution was added 1 h before termination. Then, the cells were treated with H2O2 or PA, and ROS levels were measured by fluorescence intensity (520/605 nm) after the set period of time.

Annexin V/PI staining

AML12 cells were treated with EVs, followed by treatment with H2O2 or PA for a set period of time. Cells that had undergone apoptosis were labeled with the FITC Annexin V Apoptosis Detection Kit I (BD Bioscience, Franklin Lakes, NJ, USA) according to the manufacturer’s instructions. Fluorescently labeled cells were detected using a CytoFLEX Flow Cytometer (Beckman Coulter, CA, USA).

Statistical analysis

All data are presented as mean ± SD. To directly evaluate the effects of EV treatments under defined conditions, differences between two groups were assessed using Student’s t-test with IBM SPSS Statistics for Windows, version 23.0 (IBM Corp., Armonk, NY, USA; https://www.ibm.com/products/spss-statistics). Data were considered statistically significant when p < 0.05.

Results

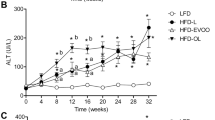

HFD did not affect the protein expression of antioxidant enzymes in adipose tissue but stimulated the loading of only CAT into adipose tissue-derived EVs

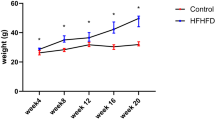

Mice were fed with NC and HFD for 12 weeks. Body weight, EAT, VAT, and SAT weight were significantly increased in the HFD group (Supplementary Fig. S1A, B). Histological analysis further revealed enlarged lipid droplets in the adipose tissue of the HFD group compared to the NC group (Supplementary Fig. S1C, D). In addition, fasting serum glucose and total cholesterol levels were significantly elevated in the HFD group, supporting the successful establishment of an HFD-induced obesity model (Supplementary Fig. S1E, F).

We explored the expression of antioxidant enzymes in adipose tissue. The mRNA expression of antioxidant enzymes in adipose tissue showed no difference in CAT and GPx1 between the groups (Fig. 1A). Although SOD1 mRNA expression was decreased in the HFD group, the protein expression of CAT, SOD1, and GPx1 showed no significant change between the groups (Fig. 1B–E).

HFD stimulated the loading of only CAT into EVs. mRNA expression of (A) CAT, SOD1, and GPx1; and protein expression (B; bands) of (C) CAT, (D) SOD1, and (E) GPx1 in adipose tissue. (F) Experimental schematic of EVs isolation from adipose tissue of mice fed NC and HFD for 12 weeks. (G) Adipose tissue-derived EVs size and vesicle observation using NanoSight (Scale bar = 500 nm). Antioxidant enzyme protein expression (H; bands), and quantification of (I) CAT in mice adipose tissue-derived EVs. Activity of (J) CAT, (K) SOD, and (L) GPx in mice adipose tissue-derived EVs. (M) S/EVs size and vesicle observation using NanoSight (Scale bar = 500 nm). (N) CAT protein expression in S/EVs. All data are presented as mean ± SD. NC vs. HFD, EV-NC vs. EV-HFD, *p < 0.05, **p < 0.01, ***p < 0.001.

Next, we isolated EVs from the adipose tissue of each group of mice (Fig. 1F). NTA showed that the peaks were mainly concentrated in the size range of 100–150 nm, typical of EV size, and confirmed the presence of CD63, an EV-specific marker (Fig. 1G, H). After confirming that EVs were successfully isolated from adipose tissue, we evaluated the expression of antioxidant enzymes loaded in EVs. Interestingly, the expression level of CAT increased 8-fold in the EV-HFD group compared to the adipose tissue-derived EVs from normal mice fed a NC (EV-NC) group, while SOD1 and GPx1 were not detected (Fig. 1H, I). Similarly, CAT activity was approximately twice as high in the EV-HFD group compared to the EV-NC group (Fig. 1J), and SOD and GPx activities did not differ between the groups (Fig. 1K, L). Therefore, these results suggest that HFD feeding does not change the levels of antioxidant enzymes in adipose tissue but upregulates CAT in adipose tissue-derived EVs compared to NC feeding.

Given the potential for adipose tissue-derived EVs to enter the circulation and affect distant organs, we next examined whether the increase in CAT observed in adipose tissue-derived EVs is also reflected in circulating EVs. To this end, we isolated S/EVs and confirmed their identity by NTA and CD63 expression (Fig. 1M, N). Consistent with our previous observations, CAT loading was significantly increased in S/EVs from HFD-fed obese mice (S/EV-HFD) compared to those from NC-fed mice (S/EV-NC) (Fig. 1N).

Adipose tissue-derived EVs protected AML12 cells from H2O2, but this effect was not due to the CAT in the EVs

Adipose tissue-derived EVs can release their loaded cargo and exert physiological effects when internalized by recipient cells. Therefore, we labeled adipose tissue-derived EVs with ExoGlow-Protein and monitored their uptake by AML12 cells. After 24 h of treatment, we stained the cell nuclei with DAPI and confirmed the extent of EV uptake. Fluorescence microscopy examination revealed that adipose tissue-derived EVs were effectively internalized by AML12 cells within 24 h (Fig. 2A). Considering the findings presented in Fig. 1, we expected that CAT, present in adipose tissue-derived EVs, might possess potential activity in AML12 cells.

Adipose tissue-derived EVs protected AML12 cells from H2O2, but this effect was not due to the CAT in the EVs. (A) Adipose tissue-derived EVs were taken up by AML12 cells after 24 h. Fluorescence microscope images show nuclei stained with DAPI (blue) and EVs labeled with ExoGlow-Protein (red) (scale bar = 50 μm). (B–D) AML12 cells were pretreated with adipose tissue-derived EVs for 24 h, followed by treatment with 600 µM H2O2 for 2 h. For cells not treated with H2O2, they were treated with adipose tissue-derived EVs for 24 h. (B) Cell viability was colorimetrically measured (450 nm). (C) ROS levels were measured by fluorescence intensity (520/605 nm) and corrected to the fluorescence intensity of an equal number of cells. (D) AML12 cells were harvested, and CAT activity was colorimetrically measured (570 nm). All data are presented as mean ± SD. *p < 0.05, **p < 0.01, ***p < 0.001. Con vs. Con + H2O2, EV-NC vs. EV-NC + H2O2, EV-HFD vs. EV-HFD + H2O2, #p < 0.05 ##p < 0.01, ###p < 0.001.

To address the question of whether adipose tissue-derived EVs internalized by AML12 cells play an antioxidant role, AML12 cells were pretreated with adipose tissue-derived EVs, followed by treatment with H2O2. Under non-stress conditions, cell viability significantly increased, and the level of ROS produced significantly decreased in both the EV-NC-treated and EV-HFD-treated groups. Surprisingly, when AML12 cells internalized either EV-NC or EV-HFD and were subsequently treated with H2O2, a significant increase in cell viability and a reduction in ROS levels were observed compared to the group treated with H2O2 alone. No significant difference was found between the effects of EV-NC and EV-HFD treatments on both cell viability and ROS levels (Fig. 2B, C). Moreover, the level of ROS reduced by adipose tissue-derived EVs was the same as that achieved with 10 µM of AA (Fig. 2C). Interestingly, there was no statistical difference in CAT activity between the groups (Fig. 2D), even though CAT was higher in EV-HFD, as shown in Fig. 1.

To determine whether adipose-derived EVs can induce antioxidant effects in other cell lines, we incorporated RAW264.7 cells. Consistent with AML12 cells, pretreatment with EV-NC and EV-HFD significantly increased cell viability and reduced ROS levels in RAW264.7 cells when subsequently treated with H2O2, compared to the group treated with H2O2 alone. There was no difference between the groups in the effects of adipose tissue-derived EVs on oxidative stress-induced RAW264.7 cells (Supplementary Fig. S2A, B). Moreover, CAT activity in RAW264.7 cells did not differ between the groups of adipose tissue-derived EVs (Supplementary Fig. S2C).

These results indicate a potential role for adipose tissue-derived EVs from both normal and obese mice in mitigating oxidative damage and suggest that HFD-induced enhancement of CAT loading into adipose tissue-derived EVs may have a limited antioxidant function.

Adipose tissue-derived EVs from both normal and obese mice showed a protective effect against H2O2-induced apoptosis

H2O2 is known to generate ROS and induce cell death. Recent research has highlighted the significance of JNK activation as a crucial downstream event responsible for H2O2-induced cell death27. Therefore, we confirmed the effect of adipose tissue-derived EVs on H2O2-induced JNK expression and apoptosis.

Interestingly, when AML12 cells were treated with H2O2 after internalizing either EV-NC or EV-HFD, the p-JNK significantly decreased compared to cells treated with H2O2 alone. Notably, there was no significant difference in p-JNK levels between the EV-NC and EV-HFD groups when treated with H2O2 (Fig. 3A, B). Next, we assessed cell death after the internalization of adipose tissue-derived EVs into AML12 cells. Upon microscopic examination, it was evident that cell density was higher and fewer blebs formed when EV-NC and EV-HFD were internalized and treated with H2O2, compared to cells treated without adipose tissue-derived EVs (Fig. 3C). Consistent with this result, treatment with EV-NC or EV-HFD, followed by H2O2, significantly inhibited apoptosis compared to treatment with H2O2 alone. Furthermore, there was no significant difference in cell apoptosis between the EV-NC and EV-HFD groups when treated with H2O2 (Fig. 3D, E).

Adipose tissue-derived EVs from both normal and obese mice showed a protective effect against H2O2-induced apoptosis. AML12 cells were pretreated with adipose tissue-derived EVs for 24 h, followed by treatment with 600 µM H2O2 for 2 h. Protein expression (A; bands) and quantification of (B) p-JNK, JNK, and β-actin by western blot. (C) Microscopic images of AML12 cells from each group. (D, E) Apoptosis measured by flow cytometry using Annexin V/PI staining. Apoptosis rate was calculated as the sum of Annexin V single positive and Annexin V and PI double positive. All data are presented as mean ± SD. *p < 0.05, **p < 0.01, ***p < 0.001.

Adipose tissue-derived EVs from both normal and obese mice also showed a protective effect against PA-induced lipotoxicity

To better simulate the obese environment in vitro, a lipotoxicity model was established using PA. When AML12 cells internalized either EV-NC or EV-HFD and were subsequently treated with PA, a significant increase in cell viability and a reduction in ROS levels were observed compared to the group treated with PA alone. Furthermore, when EV-NC or EV-HFD was internalized and then treated with PA, viability and ROS levels were restored to the same extent as in the group without PA treatment (Fig. 4A, B). Microscopic examination and Annexin V/PI staining showed that treatment with adipose tissue-derived EVs partially restored PA-induced lipotoxicity. There were no significant differences observed between the treatment groups receiving adipose tissue-derived EVs (Fig. 4C-E). These data suggest that adipose tissue-derived EVs can inhibit oxidative stress-induced apoptosis, and HFD did not affect this function.

Adipose tissue-derived EVs from both normal and obese mice also showed a protective effect against PA-induced lipotoxicity. AML12 cells were pretreated with adipose tissue-derived EVs for 24 h, followed by treatment with 200 µM PA for 24 h. (A) Cell viability was colorimetrically measured (450 nm). (B) ROS levels were measured by fluorescence intensity (520/605 nm) and corrected to the fluorescence intensity of an equal number of cells. (C) Microscopic images of AML12 cells from each group. (D, E) Apoptosis measured by flow cytometry using Annexin V/PI staining. Apoptosis rate was calculated as the sum of Annexin V single positive and Annexin V and PI double positive. All data are presented as mean ± SD. *p < 0.05, **p < 0.01, ***p < 0.001. Con vs. Con + PA, #p < 0.05 ##p < 0.01.

Discussion

Oxidative stress occurs when there is an imbalance between the production of ROS and the cell’s capacity to neutralize them through the antioxidant system. ROS, including molecules like superoxide radicals, H2O2, and hydroxyl radicals, are natural byproducts of cellular metabolism. Under normal circumstances, the body maintains a balance between ROS production and their elimination through antioxidant defense mechanisms. Antioxidant enzymes play a crucial role in maintaining this balance. They act as molecular guardians that neutralize ROS and prevent them from causing cell damage28. Their pivotal role in preserving cellular health underscores their significance for overall well-being. However, under obesity, marked shifts occur in the levels and activities of these vital enzymes, particularly within adipose tissue. These alterations contribute to the intricate interplay of factors that characterize the state of oxidative stress in obesity29,30. Understanding these mechanisms has profound implications for interventions aimed at mitigating the impact of obesity on cellular health and overall well-being.

One study analyzed the antioxidant defense in rats fed a sucrose-rich diet for 3, 15, or 30 weeks, comparing them with rats on a control diet. The results showed that the activities of SOD, CAT, GPx, and glutathione reductase in the EAT of the sucrose-rich diet group were significantly lower from as early as week 3 and remained reduced until the end of the experimental period compared with the control diet group31. Another study indicated that feeding rats a HFD for 6 weeks led to a reduction in SOD and GPx activities, but had no effect on CAT activity in adipose tissue32. A sex-specific study demonstrated that male rats fed a HFD for 11 weeks exhibited reduced SOD and GPx activities in SAT, while CAT activity remained unchanged. In contrast, female rats showed no significant changes in SOD and GPx activities, and catalase activity was increased in response to HFD feeding33. These findings indicate that, even within obesity-induced models, antioxidant enzyme activity in adipose tissue can vary depending on the animal model, sex, duration of dietary intake, and the type of diet. A human study demonstrated that both H2O2 levels (increased by 32% and 46%) and CAT activity (increased by 51% and 89%) were elevated in the visceral fat of overweight/obese (BMI ≥ 25) and centrally obese (waist-height ratio ≥ 0.5) individuals compared to lean subjects, suggesting that catalase in adipose tissue may undergo compensatory upregulation in response to obesity-induced oxidative stress30. Our present study showed that feeding mice an HFD for 12 weeks resulted in reduced mRNA expression of SOD and had no effect on the mRNA expression of CAT and GPx. However, HFD did not affect the protein expression of any of the antioxidant enzymes in the adipose tissue. The correlation between mRNA transcription and intracellular protein concentration has been reported to be very low34. Therefore, we consider protein expression to be more meaningful data and suggest that HFD did not affect antioxidant enzyme expression in adipose tissue. Interestingly, a study using a model similar to ours reported that CAT, SOD, and GPx activities were all reduced in EAT of mice fed a HFD for 12 weeks35. Taken together, these findings suggest that the expression levels and activities of antioxidant enzymes in adipose tissue do not always correlate. This discrepancy raises intriguing questions about the potential role of EVs as a regulatory mechanism in adipose tissue adaptation to systemic metabolic stress induced by obesity.

For the first time, we confirmed the expression of antioxidant enzymes in adipose tissue-derived EVs. Surprisingly, we observed an increase in CAT protein and activity in adipose tissue-derived EVs from HFD-fed obese mice. Only a limited number of studies have confirmed the existence of antioxidant enzymes loaded in EVs. One study discovered heightened levels of GPx1 in exosomes derived from hypoxic glioblastoma cells. Notably, GPx1 in these hypoxic-glioblastoma exosomes contributed significantly to oxidative stress resistance36. This suggests that contingent on the cellular stress milieu, there may be a promotion in the loading of specific antioxidant enzymes into EVs. Nevertheless, the precise molecular mechanism governing this loading process remains unknown.

Previous studies have demonstrated that adipose tissue-derived EVs from HFD-fed obese mice can induce endoplasmic reticulum stress, inflammation, insulin resistance, and lipid synthesis in hepatocytes37. Therefore, adipose tissue-derived EVs may play an important role in the development of obesity-related metabolic diseases by influencing other tissues. We investigated whether adipose tissue-derived EVs affect oxidative stress-induced hepatocyte damage. Interestingly, we found that adipose tissue-derived EVs suppressed H2O2 or PA-induced ROS production and apoptosis in the hepatocytes. Additionally, these results were not significantly different between the NC and HFD groups, even though adipose tissue-derived EVs from HFD-fed obese mice were loaded with more CAT. Previous studies have shown that CAT overexpression in mice adipose tissue did not confer systemic metabolic protection against HFD-induced obesity38. This suggests that the overexpression of catalase within adipose tissue may be insufficient to counteract the metabolic consequences of obesity. Similarly, in our study, CAT was selectively enriched in EV-HFD; however, this was not accompanied by a marked improvement in oxidative balance or protective effects in recipient cells compared with EV-NC. These findings imply that catalase loading into EVs may represent a compensatory, rather than a functionally protective, response to obesity-induced oxidative stress. In conclusion, our results indicate that obesity-induced loading of more catalase into adipose tissue-derived EVs cannot improve their antioxidant capacity. Moreover, our results suggest that adipose tissue-derived EVs can serve as a tool to maintain homeostasis and defend against oxidative stress, thereby supporting normal physiological functions (Fig. 5). However, this study has a few limitations. Given the limited yield of EVs from adipose tissue, sample availability posed a considerable restriction, making further evaluation of enzyme activity in the adipose tissue itself difficult. In addition, this study did not elucidate the specific mechanism through which EVs perform their antioxidant function. Moreover, we did not confirm whether specific pathways of ROS production, such as endoplasmic reticulum stress or mitochondrial stress, are regulated by EVs. These limitations will be the focus of future research.

Schematic diagram showing the effect of adipose tissue-derived EVs from diet-induced mice on the antioxidant properties of hepatocytes induced by oxidative stress. EV-HFD loaded approximately 8-times more CAT than EV-NC. However, when hepatocytes underwent oxidative stress, such as from H2O2 or PA, both EV-NC and EV-HFD provided similar antioxidant protective effects.

Conclusion

Despite the modern understanding that extracellular vesicles (EVs) play a critical role in intercellular communication, the antioxidant function of adipose tissue-derived EVs in obesity has not been studied. For the first time, we have found that adipose tissue-derived EVs from obese mice provide a similar antioxidant protective effect to hepatocytes under oxidative stress as those from normal mice, despite loading an 8-fold higher amount of catalase. Our findings show that adipose tissue-derived EVs provide antioxidant effects to hepatocytes regardless of their origin, and this mechanistic insight may be adopted as a therapeutic consideration in the context of obesity-liver disease.

Data availability

All data generated or analysed during this study are included in this published article (and its Supplementary Information files). For all other inquiries, contact the corresponding author.

References

Hill, J. O., Wyatt, H. R. & Peters, J. C. Energy balance and obesity. Circulation 126, 126–132. https://doi.org/10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.111.087213 (2012).

Blüher, M. Obesity: Global epidemiology and pathogenesis. Nat. Rev. Endocrinol. 15, 288–298. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41574-019-0176-8 (2019).

Wen, X. et al. Signaling pathways in obesity: Mechanisms and therapeutic interventions. Signal. Transduct. Target. Ther. 7, 298. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41392-022-01149-x (2022).

Hruby, A. & Hu, F. B. The epidemiology of obesity: A big picture. Pharmacoeconomics 33, 673–689. https://doi.org/10.1007/s40273-014-0243-x (2015).

Tun, S. et al. Therapeutic efficacy of antioxidants in ameliorating obesity phenotype and associated comorbidities. Front. Pharmacol. 11, 1234. https://doi.org/10.3389/fphar.2020.01234 (2020).

Amos, D. L. et al. Catalase overexpression modulates metabolic parameters in a new ‘stress-less’ leptin-deficient mouse model. Biochim. Biophys. Acta Mol. Basis Dis. 1863, 2293–2306. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.bbadis.2017.06.016 (2017).

Alcalá, M. et al. Increased inflammation, oxidative stress and mitochondrial respiration in brown adipose tissue from obese mice. Sci. Rep. 7, 16082. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-017-16463-6 (2017).

Piao, L. et al. Impaired peroxisomal fitness in obese mice, a vicious cycle exacerbating adipocyte dysfunction via oxidative stress. Antioxid. Redox Signal. 31, 1339–1351. https://doi.org/10.1089/ars.2018.7614 (2019).

Nguyen, P. et al. Liver lipid metabolism. J. Anim. Physiol. Anim. Nutr. (Berl). 92, 272–283. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1439-0396.2007.00752.x (2008).

Boden, G. Obesity and Free Fatty Acids. Endocrinol. Metab. Clin. North. Am. 37, 635–646. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ecl.2008.06.007 (2008).

Fabbrini, E., Sullivan, S. & Klein, S. Obesity and nonalcoholic fatty liver disease: Biochemical, metabolic, and clinical implications. Hepatology 51, 679–689. https://doi.org/10.1002/hep.23280 (2010).

Marseglia, L. et al. Oxidative stress in obesity: A critical component in human diseases. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 16, 378–400. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijms16010378 (2014).

Savini, I., Catani, M. V., Evangelista, D., Gasperi, V. & Avigliano, L. Obesity-associated oxidative stress: Strategies finalized to improve redox state. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 14, 10497–10538. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijms140510497 (2013).

Manna, P., Jain, S. K. & Obesity Oxidative stress, adipose tissue dysfunction, and the associated health risks: Causes and therapeutic strategies. Metab. Syndr. Relat. Disord. 13, 423–444. https://doi.org/10.1089/met.2015.0095 (2015).

Brahma, M. K. et al. Oxidative stress in obesity-associated hepatocellular carcinoma: Sources, signaling and therapeutic challenges. Oncogene 40, 5155–5167. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41388-021-01950-y (2021).

Wen, Z. et al. Hypertrophic adipocyte-derived exosomal miR-802-5p contributes to insulin resistance in cardiac myocytes through targeting HSP60. Obesity 28, 1932–1940. https://doi.org/10.1002/oby.22932 (2020).

Mei, R., Qin, W., Zheng, Y., Wan, Z. & Liu, L. Role of adipose tissue derived exosomes in metabolic disease. Front. Endocrinol. 13, 873865. https://doi.org/10.3389/fendo.2022.873865 (2022).

Lazar, I. et al. Adipocyte exosomes promote melanoma aggressiveness through fatty acid oxidation: A novel mechanism linking obesity and cancer. Cancer Res. 76, 4051–4057. https://doi.org/10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-16-0651 (2016).

Moraes, J. A. et al. Adipose tissue-derived extracellular vesicles and the tumor microenvironment: Revisiting the hallmarks of cancer. Cancers 13, 3328. https://doi.org/10.3390/cancers13133328 (2021).

Gul, B., Syed, F., Khan, S., Iqbal, A. & Ahmad, I. Characterization of extracellular vesicles by flow cytometry: Challenges and promises. Micron 161, 103341. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.micron.2022.103341 (2022).

Doyle, L. M. & Wang, M. Z. Overview of extracellular vesicles, their origin, composition, purpose, and methods for exosome isolation and analysis. Cells 8, 727. https://doi.org/10.3390/cells8070727 (2019).

Cheng, L. & Hill, A. F. Therapeutically harnessing extracellular vesicles. Nat. Rev. Drug Discov. 21, 379–399. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41573-022-00410-w (2022).

Mathieu, M., Martin-Jaular, L., Lavieu, G. & Théry, C. Specificities of secretion and uptake of exosomes and other extracellular vesicles for cell-to-cell communication. Nat. Cell. Biol. 21, 9–17. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41556-018-0250-9 (2019).

Raposo, G. & Stoorvogel, W. Extracellular vesicles: Exosomes, microvesicles, and friends. J. Cell. Biol. 200, 373–383. https://doi.org/10.1083/jcb.201211138 (2013).

Welsh, J. A. et al. Minimal information for studies of extracellular vesicles (MISEV2023): From basic to advanced approaches. J. Extracell. Vesicles 13, e12404. https://doi.org/10.1002/jev2.12404 (2024).

de Moura, E. et al. Diet-induced obesity in animal models: Points to consider and influence on metabolic markers. Diabetol. Metab. Syndr. 13, 32. https://doi.org/10.1186/s13098-021-00647-2 (2021).

Zhang, S. et al. c-Jun N-terminal kinase mediates hydrogen peroxide-induced cell death via sustained poly(ADP-ribose) polymerase-1 activation. Cell. Death Differ. 14, 1001–1010. https://doi.org/10.1038/sj.cdd.4402088 (2007).

Kurutas, E. B. The importance of antioxidants which play the role in cellular response against oxidative/nitrosative stress: Current state. Nutr. J. 15, 71. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12937-016-0186-5 (2016).

Alcalá, M. et al. Vitamin E reduces adipose tissue fibrosis, inflammation, and oxidative stress and improves metabolic profile in obesity. Obesity 23, 1598–1606. https://doi.org/10.1002/oby.21135 (2015).

Akl, M. G., Fawzy, E., Deif, M., Farouk, A. & Elshorbagy, A. K. Perturbed adipose tissue hydrogen peroxide metabolism in centrally obese men: Association with insulin resistance. PLoS One 12, e0177268. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0177268 (2017).

D’Alessandro, M. E., Selenscig, D., Illesca, P., Chicco, A. & Lombardo, Y. B. Time course of adipose tissue dysfunction associated with antioxidant defense, inflammatory cytokines and oxidative stress in dyslipemic insulin resistant rats. Food Funct. 6, 1299–1309. https://doi.org/10.1039/c4fo00903g (2015).

Charradi, K., Elkahoui, S., Limam, F. & Aouani, E. High-fat diet induced an oxidative stress in white adipose tissue and disturbed plasma transition metals in rat: Prevention by grape seed and skin extract. J. Physiol. Sci. 63, 445–455. https://doi.org/10.1007/s12576-013-0283-6 (2013).

Vasconcelos, R. P. et al. Sex differences in subcutaneous adipose tissue redox homeostasis and inflammation markers in control and high-fat diet fed rats. Appl. Physiol. Nutr. Metab. 44, 720–726. https://doi.org/10.1139/apnm-2018-0611 (2019).

Liu, Y., Beyer, A. & Aebersold, R. On the dependency of cellular protein levels on mRNA abundance. Cell 165, 535–550. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.cell.2016.03.014 (2016).

Illesca, P. et al. Hydroxytyrosol supplementation ameliorates the metabolic disturbances in white adipose tissue from mice fed a high-fat diet through recovery of transcription factors Nrf2, SREBP-1c, PPAR-γ and NF-κB. Biomed. Pharmacother. 109, 2472–2481. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.biopha.2018.11.120 (2019).

Lei, F. J. et al. Cellular and exosomal GPx1 are essential for controlling hydrogen peroxide balance and alleviating oxidative stress in hypoxic glioblastoma. Redox Biol. 65, 102831. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.redox.2023.102831 (2023).

Son, T. et al. Adipose tissue-derived exosomes contribute to obesity-associated liver diseases in long-term high-fat diet-fed mice, but not in short-term. Front. Nutr. 10, 1162992. https://doi.org/10.3389/fnut.2023.1162992 (2023).

Croft, A. J. et al. Overexpression of mitochondrial catalase within adipose tissue does not confer systemic metabolic protection against diet-induced obesity. Antioxid. (Basel). 12, 1137. https://doi.org/10.3390/antiox12051137 (2023).

Acknowledgements

This research was supported by Basic Science Research Program through the National Research Foundation of Korea (NRF) funded by the Ministry of Education (RS-2023-00274829).

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

Conceptualization, I.J., J.L., S.-J.P. and O.-K.K.; methodology, I.J., J.L., S.-J.P. and O.-K.K.; validation, I.J., J.L., S.-J.P. and O.-K.K.; investigation, I.J., J.L., S.-J.P. and O.-K.K.; writing—original draft preparation, I.J., J.L., S.-J.P. and O.-K.K.; I.J. and J.L. should be considered joint first authors. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Corresponding authors

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher’s note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Supplementary Information

Below is the link to the electronic supplementary material.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if you modified the licensed material. You do not have permission under this licence to share adapted material derived from this article or parts of it. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Jeong, I., Lee, J., Park, SJ. et al. High fat diet enhances catalase loading into adipose tissue derived extracellular vesicles with limited effect on oxidative stress. Sci Rep 15, 31010 (2025). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-15594-5

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-15594-5

Keywords

This article is cited by

-

Pathophysiological Roles of Obesity-Induced Alterations in Extracellular Vesicles Derived from Adipose Tissue and Adipocytes

Current Obesity Reports (2026)

-

Plant-Derived Exosomes for Enzyme Delivery in Prostate Cancer: A Narrative Perspective and Conceptual Roadmap

Bratislava Medical Journal (2025)