Abstract

Festivals and city-wide mass events are prevalent in human societies worldwide, drawing large crowds. Such events range from concerts with a dozen attendees to large-scale actions with thousands of viewers. It is the highest priority for each organizer of such an occasion to be capable of upholding a higher standard of safety and minimizing the danger of events, especially medical emergencies. Therefore, establishing sufficient safety measures is significant. There is a requirement for event organizers and emergency response personnel to identify developing, potentially critical crowd situations at an early stage during city-wide mass assemblies. In general, the localization of the global positioning system (GPS) and proximity-based tracking is employed to capture intricate crowd dynamics throughout an event. Recently, technology has been used in numerous diverse ways to achieve these large crowds. For example, computer vision-based models are employed to observe the flexibility and behaviour of crowds. In this manuscript, a model for Medical Response Efficiency in Real-Time Large Crowd Environments via Smart Coverage and Hiking Optimisation (MRELC-SCHO) is presented, aiming to maintain stable ecological health. The primary objective of this paper is to propose an effective method for enhancing medical response efficiency in large crowd environments by utilizing advanced optimization algorithms. Initially, the MRELC-SCHO model utilizes min-max normalization to transform the input data into a structured format. Furthermore, the Chimp Optimisation Algorithm (CHOA) model is employed for the feature selection (FS) process to select the most significant features from the dataset. Additionally, the MRELC-SCHO technique utilizes the bidirectional long short-term memory with an auto-encoder (BiLSTM-AE) method for classification. Finally, the parameter selection for the BiLSTM-AE model is performed by using the Hiking Optimisation Algorithm (HOA) model. The experimentation of the MRELC-SCHO approach is accomplished under the Ecological Health dataset. The comparison analysis of the MRELC-SCHO approach revealed a superior accuracy value of 98.56% compared to existing models.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Crowd management is a crucial area of study, as it directly impacts the safety and well-being of individuals. A crowd refers to a large group of people who come together, driven by a common goal or collective emotions1. Numerous motives can contribute to a crowd’s existence, including a political rally, a spiritual get-together, a concert, or a sports event. Crowd management is a challenging task that involves thorough and detailed planning, precise execution, and proactive control approaches2. The consequences of any absence or error in management will be intolerable and expensive. Old histories have documented damages and mortalities at crowded gatherings. Hence, it is vital to effectively monitor the safety of the crowd and implement essential management strategies throughout the event. In this procedure, individuals are assessed to identify potential crowd hazards3. If a hazard is found, it should be observed and recorded. Similarly, crowd assessment is used to interpret crowd actions and enhance crowd control tools. Furthermore, medical management and response are key services provided by towns at various levels4. Medical management approaches have recently been reinforced through town protocols, which will only control familiar events. However, as cities became more sophisticated and people’s behaviour evolved, nature, scale, shape, and planning for events became increasingly complex to forecast5. The prompt production and distribution of information regarding events are crucial for mobilizing response resources, coordinating efforts, evaluating circumstances, and conducting analysis, which in turn informs future prevention and preparedness approaches. This prompt provision fosters an environment of credibility and trust among urban residents in a highly dynamic atmosphere, providing rescue workers with basic information regarding events and their geographical context6. Smartphone usage has grown rapidly. As it has become more common, smartphones have also undergone drastic development: models nowadays consist of hardware, including accelerometers, GPS sensors, gyroscopic sensors, magnetic compasses, cameras, and pedometers. Furthermore, Wi-Fi and Bluetooth are also standard in new phones, permitting continuous internet connection7. Such influential sensors are used in numerous applications that operate on smartphones, such as context-aware mobile applications, which utilize the user’s location. Several applications utilize GPS-aided localization techniques specifically for external landscapes8. Computer vision (CV) methods are used for monitoring crowd movement and actions. Although significant developments have occurred in this domain, the models have become ineffective when applied on a larger scale due to their limited perspective lines and unclear detection limits9. Currently, video-assisted monitoring methods are frequently used for medical response efficiency. The current study has focused on developing computer-aided models to autonomously analyze stored acts and identify unusual and potentially unsafe crowd conditions10.

In this manuscript, a Medical Response Efficiency in Real-Time Large Crowd Environments via Smart Coverage and Hiking Optimisation (MRELC-SCHO) model for stable ecological health is presented. The primary objective of this paper is to propose an effective method for enhancing medical response efficiency in large crowd environments by utilizing advanced optimization algorithms. Initially, the MRELC-SCHO model utilizes min-max normalization to transform input data into a structured format. Furthermore, the Chimp Optimisation Algorithm (CHOA) model is employed for the feature selection (FS) process to select the most significant features from the dataset. Additionally, the MRELC-SCHO technique utilizes the bidirectional long short-term memory with an auto-encoder (BiLSTM-AE) method for classification. Finally, the parameter selection for the BiLSTM-AE model is performed by using the Hiking Optimisation Algorithm (HOA) model. The experimentation of the MRELC-SCHO approach is accomplished under the Ecological Health dataset. The significant contribution of the MRELC-SCHO approach is listed below.

-

The MRELC-SCHO technique utilizes min–max normalization to preprocess data, which scales features to a uniform range, improving consistency and mitigating bias. This preprocessing step enhances the quality of the input data, thereby improving the effectiveness of subsequent feature selection and classification, and ultimately increasing the overall accuracy and reliability of the model.

-

The MRELC-SCHO method utilizes the CHOA model to select the most relevant features, thereby enhancing the efficiency and accuracy of the learning process. By concentrating on key attributes, it mitigates dimensionality and improves classification performance. This results in faster training and better generalization on new data.

-

The MRELC-SCHO approach employs a BiLSTM-AE model to capture intrinsic temporal patterns and reconstruct key features for accurate classification. This approach enhances the model’s ability to learn sequential dependencies and mitigate noise, leading to improved accuracy and more robust predictions.

-

The MRELC-SCHO methodology utilizes the HOA technique for fine-tuning parameters, improving overall performance by effectively searching for the optimal configuration. This optimization mitigates training time and prevents overfitting, resulting in more reliable and accurate model predictions across diverse datasets.

-

The MRELC-SCHO model uniquely incorporates advanced optimization algorithms such as CHOA and HOA, with BiLSTM-AE for feature selection, classification, and parameter tuning. This integration enhances accuracy and efficiency by optimizing each stage of the learning process. Its novelty is in combining these techniques to create a comprehensive and adaptive framework that improves performance across multiple tasks.

Literature review

Cai et al.11 examined a new model for cognitive energy-efficient healthcare-based aerial computing and trajectory optimization (CEHEAT) for addressing these challenges. The presented model enhances energy efficiency by integrating cognitive IoT (CIoT) capabilities with autonomous aerial vehicles (AAVs) and aerial computing to address the diverse needs of healthcare systems. This model ensures effective data processing and collection through cognitive skills, such as dynamic resource allocation and adaptive sensing, guaranteeing reliable healthcare monitoring. Chen et al.12 proposed a smart regional health and safety monitoring and emergency treatment system that integrates IoT, cloud computing, big data, and AI techniques to facilitate understanding of cross-regional medical resource planning, telemedicine consultation, ICU bed management, and other related applications. Damaševičius et al.13 aimed to explore the utilization of IoES in disaster management and emergency response, with a concentration on the IoT devices and sensors in delivering dynamic information to the ambulance team. Zhang et al.14 introduced an original method that utilizes a hybrid Near-Field and Far-Field Non-Orthogonal Multiple Access (NOMA) approach to address the challenges of increased device bandwidth and density in emergencies. The introduced resource orchestration method perfectly stabilizes energy, Quality of Service (QoS), and quantity through a power and device matching framework for reasonable PD-NOMA entry. A real-time Actor-Critic framework for a practical multi-objective optimizer, safeguarding proper resource allocation between IoT systems.

Lv et al.15 proposed the emergency-aware distributed edge intelligence (DEI) for medical response (EDEM) model, a novel model that utilizes DEI to address these challenges. Particularly, EDEM presents a hierarchical edge collaborative computing structure, which practically builds learning fields depending on a complete medical data capability technique. Next, a deep-reinforcement-learning-driven node selection framework safeguards effective task distribution in the system. Liu et al.16 designed a PSES multiterminal fusion system (SafeCity) that leveraged the expertise of diverse mobile crowd sensing concepts. Khaer et al.17 recommended UAVs as an effective technique for dynamic data transmission and trained them to function more capably compared to human resources, with greater security. This could be a crucial model in emergencies18. Recommended a new collaborative health emergency response system in the Cooperative Intelligent Transportation Environment, such as C-HealthIER. C-HealthIER constantly monitors individuals’ health and implements supportive behaviour in response to health crises through vehicle-to-infrastructure and vehicle-to-vehicle data sharing to identify nearby healthcare professionals. Dehbozorgi, Ryabchykov, and Bocklitz19 evaluated the efficiency of various feature extraction techniques, such as statistical, radiomics, and DL, for binary classification of medical images using Principal Component Analysis–Linear Discriminant Analysis (PCA-LDA) models. The method showed superiority over recent models such as ResNet50 and DenseNet121. Nurmaini et al.20 improved cervical precancerous lesion detection by utilizing a DL technique, You Only Look Once version 8 (YOLOv8), integrated with Slicing Aided Hyper Inference (SAHI) and medical guidelines, to analyze cervicograms before and after acetic acid application for more accurate and consistent visual inspection with acetic acid (VIA) assessments.

Materials and methods

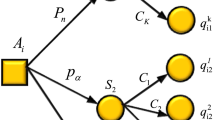

In this manuscript, the MRELC-SCHO approach for stable ecological health is presented. The primary objective of this paper is to propose an effective method for improving medical response efficiency in large crowd environments by utilizing advanced optimization algorithms. It comprises four different kinds of processes involving data normalization, attribute selection using CHOA, classification, and parameter tuning using HOA. Figure 1 exemplifies the entire procedure of the MRELC-SCHO model.

Stage I: Min–Max normalisation

Initially, the MRELC-SCHO applies a min-max normalization-based data normalization method to convert the input data21. This model is chosen for its effective scaling capability and also preserves the original distribution while ensuring uniformity across diverse features. This model preserves the relative associations of the original data, which can enhance the model’s convergence and stability. This is especially beneficial when input variables have different units or scales, as it prevents features with larger ranges from dominating the learning process. It is simple to implement, computationally efficient, and works well with algorithms sensitive to feature scaling, such as neural networks and optimization algorithms. These merits make it a reliable choice for preprocessing data in DL models.

Min-max normalization is a significant process that is utilized to measure data within a precise range, typically between 0 and 1, making it ideal for normalizing varied input variables in real-time applications. From the perspective of medical response efficiency in large crowds, min-max normalization ensures that numerous parameters, such as crowd density, response time, and resource accessibility, are on a similar scale. This enhances the efficiency of the smart coverage model, as it permits superior integration and organization of real-time data. By regularising the values, the system can generate more precise decisions, which ensures appropriate medical responses and enhances resource allocation. In large-crowd situations, this normalization aids in minimizing biases produced by fluctuating scales of input data, ultimately improving overall coordination and medical response tactics. In this approach, the method becomes more adaptable to dynamic environments, ensuring optimal performance in crowd management and medical emergencies.

Stage II: attribute optimization using CHOA

Additionally, the CHOA is employed in the FS process to select the most significant features from a dataset22. This model is chosen for its robust capability in balancing exploration and exploitation phases. The technique also shows efficiency in searching the feature space for the most relevant attributes. The method replicates the intelligent hunting behaviour of chimps, thus enabling it to avoid local optima and achieve better global solutions. It is computationally efficient and adaptable to high-dimensional data, making it appropriate for intrinsic datasets. Additionally, CHOA’s ability to dynamically adjust its search strategy improves convergence speed and accuracy in feature selection, ultimately enhancing model performance and mitigating overfitting. These advantages make CHOA an ideal choice for attribute optimization tasks.

Chimpanzees are highly social great apes closely connected to humans, and they live in a dynamic fission-fusion society where the composition and size of the group fluctuate. This social framework is reflected in the CHOA, where individual groups discover the searching area by employing diverse approaches, utilizing individual abilities to resolve complex concerns. Searching happens in exploitation and exploration. Compute pursuing prey and driving. To split the driving and succeeding prey (1) and (2) are mathematical expressions.

The vectors \(\:a\) and \(\:c\) are inspected in Eqs. (3, 4), correspondingly.

Barrier, Chaser, and Driver chimpanzees sometimes search, but attackers typically do not. The finest position of prey is unidentified in a searching area. Therefore, the other locations of chimpanzees are modified to correspond to those of better chimps, assisting them to enhance their search models.

During this primary phase, chimps abandon their roles and turn chaotic. It is stated as a fifty per cent chance of employing chaotic movement rather than the standard upgrading procedure. This enables the model to escape local optima and discover novel solutions. The searching procedure implies chimps in diverse roles, modifying their locations depending on the assessed location of prey. Parameters are adaptively adjusted to faster convergence.

Chimpanzees are arbitrarily allocated to barricades, attackers, drivers, and chasers. Every chimp employs group-based “f” coefficient upgrades. In every iteration, the barrier, attacker, driver, and chaser chimpanzees evaluate their position relative to the prey. Every possible solution modifies its prey distance depending on the approximation. The “m” and “c” vectors are adaptively adjusted to accelerate convergence and prevent local optima.

The fitness function (FF) utilized in the proposed model is designed to strike a balance between the count of designated features in all the results (smallest) and the classifier accuracy (highest) achieved by employing this nominated feature. Equation (9) signifies the FF to assess the solution.

While \(\:{\gamma\:}_{R}\left(D\right)\) implies the classifier ratio of errors, \(\:\left|R\right|\:\)denotes the cardinality of the selected subset, and \(\:\left|C\right|\) exemplifies the complete number of features. \(\:\alpha\:\) and \(\:\beta\:\) are two parameters that match the consequence of classifier quality and subset length.

Stage III: classification using the BiLSTM-AE model

Moreover, the MRELC-SCHO model incorporates the BiLSTM-AE technique for classification23. This methodology is chosen for its ability to capture long-range dependencies in sequential data by processing data in both forward and backwards directions. The AE model assists in learning effective feature representations by reconstructing input data, which mitigates noise and emphasizes crucial patterns. The approach also enhances context understanding compared to conventional LSTM or unidirectional models. This methodology presents enhanced robustness, specifically for time-series or sequential datasets, resulting in higher accuracy and better generalization compared to other classifiers. Its integrated feature learning and classification capabilities make it appropriate for intrinsic, real-world tasks where data relationships are complex. Figure 2 portrays the configuration of BiLSTM-AE.

AE is one of the neural network frameworks built from stacked layers, frequently utilizing nonlinear activation functions that are complex in modelling nonlinear relations in the information. With this ability, AE is widely utilized for reducing dimensions and extracting features in higher-dimensional datasets, offering a substrate for the following challenges of ML. A standard AE typically consists of three elements: latent representation, decoder, and encoder. The encoder mapping is a process that converts higher-dimensional input data into a lower-dimensional representation, known as a latent representation.

Now, \(\:{b}_{e}\) depicts the biased vector with dimension \(\:p\), \(\:g\) refers to the activation function, and \(\:{W}_{e}\) is the weighted matrix with dimension \(\:p\:\times\:\:m\). The dimension of the latent space \(\:z\) is denoted as \(\:p\); now, p represents a positive integer, indicating the reduced dimensionality of the input data.

The decoder employs the hidden representation \(\:z\) to rebuild the new input with high probability. The reconstructed output is depicted as X, whereas the variance between X and the new input \(\:x\) is stated as an error of reconstruction. Equation (11) standardizes the procedure of decoding, \(\:{W}_{d}\) refers to the weighted matrix with dimension \(\:m\times\:p,\) \(\:f\) indicates the function of activation, \(\:X\) specifies reconstructed input data, and \(\:{b}_{d}\) signifies the biased vector with dimension \(\:m\). Equation (12) defines the computation of reconstruction error, now \(\:m\) signifies the dimensionality of the original data, equivalent to variable counts, and \(\:L\) is the reconstruction error.

LSTM is an upgraded version of RNN that effectually alleviates the vanishing gradient concern by adaptively managing the values of output and input gates, thus regulating the forgetting or retention of data in the state of the cell. It enables LSTM to acquire and utilize temporal dependencies in time sequences. The framework of LSTM comprises three significant elements: input, output, and forget gates, with the data flow among these elements.

Now, \(\:{i}_{t}\), \(\:{\text{o}}_{t}\), and \(\:{f}_{t}\) refer to the outputs of the input, output, and forgetting gates. These outputs are \(\:n\)-dimensional vectors, where n corresponds to the number of hidden units in the hidden layer (HL) of the LSTM. \(\:{W}_{fx},{\:W}_{\stackrel{\sim}{c}x},{\:W}_{ix}\), and \(\:{W}_{ox}\) are the weighted matrices corresponding to the input at the existing time step \(\:{\chi\:}_{i}\) and the forgetting, input, and output gates, respectively. Every weighted matrix has dimensions \(\:n\) × m, where \(\:m\) refers to the dimensionality of the input vector. \(\:{b}_{f},{b}_{C},\:{b}_{j}\), and \(\:{b}_{\text{o}}\) refer to the \(\:n\)-dimensional biased vectors for the forgetting, input, and output gates, respectively. \(\:{W}_{fh},{\:W}_{\stackrel{\sim}{c}h},{\:W}_{ih}\), and \(\:{W}_{oh}\) are the weighted matrices corresponding to the forgetting, cell, input, and output, respectively, among the HL at the preceding time step ht-1. Every weighted matrix has dimensions \(\:n\times\:n.\).

LSTM is highly effective at taking temporal dependency in time sequence data. Nevertheless, it depends on previous memory that can induce errors in the task of classification and prediction. Bi-LSTM, conversely, employs bi-directional data flow by combining either past-to-future or future-to-past dependency, thus allowing for more precise inspection and time-series data processing.

Stage IV: HOA-based parameter tuning

Finally, the parameter choice of the BiLSTM-AE model is performed by using the HOA technique24. This model is chosen for its efficiency in balancing the exploration and exploitation phases, which enables it to search effectively for optimal hyperparameters. Compared to conventional tuning methods, such as grid or random search, HOA is more adaptive and can avoid getting trapped in local minima, resulting in improved model performance. This technique enables dynamic adjustment of the search process based on feedback and replicates the strategic movements of hikers. HOA is computationally efficient and appropriate for high-dimensional parameter spaces, mitigating tuning time while improving accuracy and generalization. These advantages make HOA an ideal choice for optimizing model parameters.

The HOA is stimulated by experiments faced by individuals attempting to attain the highest hills, rocks, or mountains, which depend upon the condition. Throughout a hike, individuals frequently factor in either instinctively or intentionally. Hikers are well-known for the region’s landscape and will estimate the time to reach the meeting. This leads to delays in attaining the global optimum throughout a trek. The method depends upon duplicating the task of hiking to tackle optimization problems.

The HOA mainly originated from Tobler’s Hiking Function (THF). This function employs an exponential method to evaluate a hiker’s pace. THF is mathematically formulated below:

Here, \(\:{\mathcal{W}}_{i,t}\) signifies the speed of \(\:the\:ith\) hiker, designated in km/h at \(\:t\)ime t, \(\:{and\:S}_{i,t}\) means the gradient of the trail. Also, the gradient \(\:{S}_{i,t}\) is computed below:

where, \(\:dx\) and \(\:dh\) signify the variations in distance and height moved by the hiker, respectively. Furthermore, \(\:{\theta\:}_{i,t}\) is the slope angle within the interval of \(\:[\text{0,5}0^\circ\:].\).

The HOA model influences the decision-making procedure of the cluster and the individual cognitive abilities of every hiker.

The parameter \(\:{\gamma\:}_{i,t}\) signifies a randomly generated value from a uniform distribution between \(\:0\) and 1. While \(\:{\mathcal{W}}_{i,t}\) and \(\:{\mathcal{W}}_{i,t-1}\) correspond to the hiker’s speed \(\:i\) at the present and preceding time steps, respectively. \(\:{\beta\:}_{best}\) denotes the position of the leading hiker, whereas \(\:{\alpha\:}_{i,t}\) means the SF for\(\:\:the\:ith\) hiker. The SF aids the hiker in maintaining proximity, which allows them to follow the leader’s direction and stay in sync with any signals.

Let the hiker speed \(\:i\), the novel position \(\:{\beta\:}_{i,t+1}\) for hiker \(\:i\) be computed below:

First, the way agents play a crucial part in the performance of numerous meta-heuristic techniques, namely HOA, which influences the probability of discovering feasible solutions and the convergence rate. Here, the HOA uses a randomly generated initialization model to set the initial locations of its agents. The starting locations of hikers are signified as \(\:{\beta\:}_{i,t}\), and are recognized by the upper \(\:{\varphi\:}_{j}^{2}\) and lower \(\:{\varphi\:}_{j}^{1}\) bounds, as stated by the below-mentioned formulation:

\(\:{\delta\:}_{j}\) refers to a random value from a uniform distribution between \(\:zero\) and one. \(\:{\varphi\:}_{j}^{1}\) and \(\:{\varphi\:}_{j}^{2}\) correspond to the least and highest bounds of \(\:the\:jth\) decision variable. The SF is a primary parameter that directs the balance between exploitation and exploration. Equation (21) defines the distance between the leader and the other members. The HOA is a global search model, primarily intended to identify optimizer issues in the solution space. To start the hike, the initial point of every hiker was recognized, and utilizing THF, their novel positions were proposed. In each iteration, the location of a leader is re-evaluated to ensure that the fittest hiker is the best.

Algorithm 1: Pseudocode of HAO.

The fitness choice is the key factor influencing the HOA’s performance. The parameter range process consists of an encoded method to evaluate the efficiency of candidate results. The HOA reveals accuracy as the primary measure for projecting FF, which is expressed below.

where \(\:FP\) and \(\:TP\) imply the positive rates of false and true positives.

Experimental result and analysis

The experimental outcomes of the MRELC-SCHO model are examined under the Ecological Health dataset25. The dataset comprises a total of 61,345 samples under four class labels. The complete details of this dataset are represented below in Table 1. The total number of features is 15, including Temperature, Timestamp, PM2.5, Soil_Moisture, Humidity, Nutrient_Level, Biodiversity_Index, Pollution_Level, Biochemical_Oxygen_Demand, Dissolved_Oxygen, Water_Quality, Air_Quality_Index, Soil_pH, Chemical_Oxygen_Demand, Total_Dissolved_Solids. But only 13 features are selected like Soil_Moisture, Temperature, Biodiversity_Index, Humidity, Nutrient_Level, Pollution_Level, Chemical_Oxygen_Demand, Water_Quality, Total_Dissolved_Solids, Air_Quality_Index, Soil_pH, Dissolved_Oxygen, Biochemical_Oxygen_Demand.

Figure 3 displays the classifier result of the MRELC-SCHO approach at 80%TRPHE and 20%TSPHE. Figure 3a,b establishes the confusion matrices with precise detection of 4 classes. Figure 3c shows the PR valuation, representative maximum performance among the 4 class labels. At Last, Fig. 3d exemplifies the ROC curve, representing efficient performances with elevated ROC for individual classes.

Table 2; Fig. 4 represent the classifier result of the MRELC-SCHO approach on 80%TRPHE and 20%TSPHE. With 80%TRPHE, the MRELC-SCHO approach achieves an average \(\:acc{u}_{y}\), \(\:pre{c}_{n}\), \(\:rec{a}_{l},\) \(\:{F1}_{Score}\), and \(\:{G}_{Measure}\:\)of 98.44%, 95.62%, 94.05%, 94.80%, and 94.82%, respectively. Furthermore, under 20%TSPHE, the MRELC-SCHO method achieves an average \(\:acc{u}_{y}\), \(\:pre{c}_{n}\), \(\:rec{a}_{l},\) \(\:{F1}_{Score}\), and \(\:{G}_{Measure}\:\)of 98.56%, 95.71%, 94.44%, 95.05%, and 95.06%, respectively.

In Fig. 5, the training (TRNG) \(\:acc{u}_{y}\) and validation (VALID) \(\:acc{u}_{y}\) of the MRELC-SCHO approach at 80:20 are shown. The figure emphasizes that both \(\:acc{u}_{y}\) values illustrate an increasing propensity, indicating the MRELC-SCHO approach’s effectiveness with improved performance across several iterations. Likewise, both \(\:acc{u}_{y}\) remain close to the epochs, reflecting minimal overfitting and displaying the MRELC-SCHO model’s improved outcome.

In Fig. 6, the TRNG and VALID losses outcome of the MRELC-SCHO method under 80:20 is depicted. It is noted that both values elucidate a declining trend, reporting the MRELC-SCHO approach’s capability to stabilize a trade-off amid generalization as well as data fitting. The persistent decline further suggests that the MRELC-SCHO approach will perform better.

Figure 7 illustrates the classifier result of the MRELC-SCHO method at 70%TRPHE and 30%TSPHE. Figure 7a and b exhibits the confusion matrices by precise detection of all classes. Figure 7c presents the PR evaluation, specifying the maximum outcome among every class. Lastly, Fig. 7d illustrates the ROC inspection, providing capable results with higher ROC values for separate classes.

Table 3; Fig. 8 display the classifier results of the MRELC-SCHO model on 70%TRPHE and 30%TSPHE. With 70%TRPHE, the MRELC-SCHO method achieves average \(\:acc{u}_{y}\), \(\:pre{c}_{n}\), \(\:rec{a}_{l},\) \(\:{F1}_{Score}\), and \(\:{G}_{Measure}\:\)of 96.90%, 91.69%, 90.30%, 90.91%, and 90.95%, correspondingly. Moreover, under 30%TSPHE, the MRELC-SCHO method achieves average \(\:acc{u}_{y}\), \(\:pre{c}_{n}\), \(\:rec{a}_{l},\) \(\:{F1}_{Score}\), and \(\:{G}_{Measure}\:\)of 96.82%, 91.72%, 89.83%, 90.68%, and 90.72%, respectively.

In Fig. 9, the TRNG and VALID \(\:acc{u}_{y}\) outcomes of the MRELC-SCHO method under a 70:30 ratio is depicted. The outcome underlined that both \(\:acc{u}_{y}\) values reveal a growing propensity, demonstrating the proficiency of the MRELC-SCHO with upgraded performance in various iterations. Additionally, both \(\:acc{u}_{y}\) remain close to the epochs, exhibiting representative minimal overfitting and demonstrating the MRELC-SCHO method’s greater performance.

In Fig. 10, the TRNG and VALID losses of the MRELC-SCHO technique at 70:30 are demonstrated. It is indicated that both values highlight a diminishing propensity, demonstrating the proficiency of the MRELC-SCHO method in balancing a trade-off between generalization and data fitting. The frequent decline, moreover, promises improved performance for the MRELC-SCHO method.

The comparative exploration of the MRELC-SCHO technique with current models under numerous metrics is presented in Table 4; Fig. 1119,20,26,27,28. The table values highlighted that the presented MRELC-SCHO method illustrated upgraded performance with maximum \(\:acc{u}_{y}\), \(\:pre{c}_{n}\), \(\:rec{a}_{l},\) and \(\:{F1}_{Score}\) of 98.56%, 95.71%, 94.44%, and 95.05%, respectively. Whereas, the present models, such as PCA-LDA, YOLOv8, SAHI, HealthSecureNet, SVM, k-NN, LSTM, GRU, Inception-ResNet V2, and DenseNet, attained the worst performance.

In Table 5; Fig. 12, the execution time (ET) of the MRELC-SCHO technique with existing approaches is illustrated. Depending on ET, the MRELC-SCHO technique obtains the least value of 10.56 s, while the PCA-LDA, YOLOv8, SAHI, HealthSecureNet, SVM, k-NN, LSTM, GRU, Inception-ResNet V2, and DenseNet methodologies got the highest ET of 15.99 s, 20.09 s, 22.31 s, 24.26 s, 23.30 s, 24.77 s, 14.31 s, 17.88 s, 24.82 s, and 13.10 s, correspondingly.

Conclusion

In this study, the MRELC-SCHO model for stable ecological health is introduced. The primary objective of this paper is to propose an effective method for improving medical response efficiency in large crowd environments by utilizing advanced optimization algorithms. Initially, the MRELC-SCHO technique utilizes min-max normalization for converting input data into a structured format. Additionally, the CHOA is employed in the FS process to select the most significant features from a dataset. Moreover, the MRELC-SCHO technique utilizes the BiLSTM-AE technique for classification. Finally, the hyperparameter selection of the BiLSTM-AE model is performed by using the HOA model. The experimentation of the MRELC-SCHO approach is accomplished under the Ecological Health dataset. The comparison analysis of the MRELC-SCHO approach revealed a superior accuracy value of 98.56% compared to existing models.

Data availability

The data that support the findings of this study are openly available in the Kaggle repository at https://www.kaggle.com/datasets/datasetengineer/ecological-health-dataset/data, reference number25.

References

Rajendran, L. & Shankaran, R. S. January. Bigdata enabled real-time crowd surveillance using artificial intelligence and deep learning. In 2021 IEEE International Conference on Big Data and Smart Computing (BigComp), 129–132 (IEEE, 2021).

Jabbari, A., Almalki, K. J., Choi, B. Y. & Song, S. ICE-MoCha: Intelligent crowd engineering using mobility characterization and analytics. Sensors. 19(5), 1025 (2019).

Song, X. et al. Big data and emergency management: concepts, methodologies, and applications. IEEE Trans. Big Data. 8 (2), 397–419 (2020).

Lazarou, I., Kesidis, A. L., Hloupis, G. & Tsatsaris, A. Panic detection using machine learning and real-time biometric and spatiotemporal data. ISPRS Int. J. Geo-Inf. 11(11), 552 (2022).

Rezaee, K. et al. IoMT-assisted medical vehicle routing based on UAV-Borne human crowd sensing and deep learning in smart cities. IEEE Internet Things J. 10 (21), 18529–18536 (2023).

Altamirano Guerrero, O., Hernández Calderon, R., Neri, L. E. & Ibrahim, M. Treatment option selection for medical waste management under neutrosophic sets. Int. J. Neutrosophic Sci. IJNS. 21(1). (2023).

Ahmed, S. et al. Artificial intelligence and machine learning for ensuring security in smart cities. In Data-driven Mining, Learning and Analytics for Secured Smart Cities: Trends and Advances, 23–47 (Springer International Publishing, 2021).

Lv, Z., Yu, Z., Xie, S. & Alamri, A. Deep learning-based smart predictive evaluation for interactive multimedia-enabled smart healthcare. ACM Trans. Multimed. Comput. Commun. Appl. TOMM. 18 (1s), 1–20 (2022).

Bahamid, A. & Mohd Ibrahim, A. A review on crowd analysis of evacuation and abnormality detection based on machine learning systems. Neural Comput. Appl. 34 (24), 21641–21655 (2022).

Afotey, B. & Lovely-Quao, C. Ambient air pollution monitoring and health studies using low-cost Internet-of-things (IoT) monitor within KNUST community. J. Intell. Syst. Internet Things. 10(2). (2023).

Cai, W., Xue, X. & Yang, J. Energy-efficient trajectory and resource optimization for cognitive IoT-enabled UAV aerial computing in smart healthcare systems. IEEE Internet Things J. (2025).

Chen, L., Zheng, X., Sun, Z. & Li, X. Study on the development of an intelligent regional health security monitoring and emergency medical response system in less developed regions. J. Comput. Electron. Inform. Manag. 16 (1), 74–82 (2025).

Damaševičius, R., Bacanin, N. & Misra, S. From sensors to safety: Internet of emergency services (IoES) for emergency response and disaster management. J. Sens. Actuator Netw. 12(3), 41 (2023).

Zhang, C., Hou, J., Chen, C. & Li, G. Enhanced resource orchestration in near-field and far-field NOMA communications for emergency IoT applications. IEEE Internet Things J. (2025).

Lv, J., Li, K., Slowik, A. & Jiang, H. Distributed edge intelligence for rapid In-Vehicle medical emergency response in Internet-of-Vehicles. IEEE Internet Things J. (2024).

Liu, Y., Yu, Z., Cui, H., Helal, S. & Guo, B. Safecity: A heterogeneous mobile crowd sensing system for urban public safety. IEEE Internet Things J. 10 (20), 18330–18345 (2023).

Khaer, A., Sarker, M. S. H., Progga, P. H., Lamim, S. M. & Islam, M. M. February. UAVs in green health care for energy efficiency and real-time data transmission. In International Conference on Intelligent Sustainable Systems, 773–788 (Springer Nature Singapore, 2023).

Aloqaily, M., Elayan, H. & Guizani, M. C-healthier: A cooperative health intelligent emergency response system for c-its. IEEE Trans. Intell. Transp. Syst. 24 (2), 2111–2121 (2022).

Dehbozorgi, P., Ryabchykov, O. & Bocklitz, T. W. A comparative study of statistical, radiomics, and deep learning feature extraction techniques for medical image classification in optical and radiological modalities. Comput. Biol. Med. 187, 109768 (2025).

Nurmaini, S. et al. Robust assessment of cervical precancerous lesions from pre-and post-acetic acid cervicography by combining deep learning and medical guidelines. Inform. Med. Unlocked 52, 101609 (2025).

Ashai, A., Jadhav, A. & Sarkar, B. A floating normalization scheme for deep learning-based custom-range parameter extraction in BSIM-CMG compact models. arXiv preprint arXiv:2501.15190. (2025).

Shiva, C. K., Sen, S., Basetti, V. & Reddy, C. S. Forward-thinking frequency management in islanded marine microgrid utilizing heterogeneous source of generation and nonlinear control assisted by energy storage integration. Sci. Rep. 15 (1), 1–33 (2025).

Ding, X., Wang, J., Liu, Y. & Jung, U. Multivariate time series anomaly detection using working memory connections in bi-directional long short-term memory autoencoder network. Appl. Sci. 15(5), 2861 (2025).

Samiei Moghaddam, M., Azadikhouy, M., Salehi, N. & Hosseina, M. A multi-objective optimization framework for EV-integrated distribution grids using the hiking optimization algorithm. Sci. Rep. 15(1), 13324 (2025).

https://www.kaggle.com/datasets/datasetengineer/ecological-health-dataset/data

Izhar, M. et al. Cyber-Integrated Predictive Framework for Gynecological Cancer Detection (Leveraging Machine Learning on Numerical Data amidst Cyber-Physical Attack Resilience, 2025).

Shome, A., Alam, M. M., Jannati, S. & Bairagi, A. K. Monitoring human behaviour during pandemic—Attacks on healthcare personnel scenario. Telemat. Inform. Rep. 15, 100149 (2024).

Sakib, S., Tazrin, T., Fouda, M. M., Fadlullah, Z. M. & Guizani, M. DL-CRC: deep learning-based chest radiograph classification for COVID-19 detection: a novel approach. IEEE Access. 8, 171575–171589 (2020).

Acknowledgements

The authors extend their appreciation to the Deanship of Research and Graduate Studies at King Khalid University for funding this work through LargeResearch Project under grant number RGP2/231/46. Princess Nourah bint Abdulrahman University Researchers Supporting Project number(PNURSP2025R809), Princess Nourah bint Abdulrahman University, Riyadh, Saudi Arabia. The authors extend their appreciation to the Deanship ofScientific Research at Northern Border University, Arar, KSA for funding this research work through the project number “NBU-FFR-2025- 2913-04. Theauthors are thankful to the Deanship of Graduate Studies and Scientific Research at University of Bisha for supporting this work through the Fast-TrackResearch Support Program. This study is supported via funding from Prince Sattam bin Abdulaziz University project number (PSAU/2025/R/1447).

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

A.A.A.: Conceptualization, methodology, validation, investigation, writing—original draft preparation, funding. G.M.S.E.: Conceptualization, methodology, writing—original draft preparation, writing—review and editing. M.G.: methodology, validation, writing—original draft preparation. N.A.: software, validation, data curation, writing—review and editing. N.O.A.: methodology, validation, writing—original draft preparation, writing—review and editing. T.M.A.: validation, writing—original draft preparation, writing—review and editing. H.A.: validation, writing—original draft preparation, writing—review and editing. S.A.Z.: Project administration, validation, writing—original draft preparation, writing—review and editing.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher’s note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if you modified the licensed material. You do not have permission under this licence to share adapted material derived from this article or parts of it. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Alhashmi, A.A., Elhessewi, G.M.S., Ghaleb, M. et al. Enhancing medical response efficiency in real-time large crowd environments via smart coverage and deep learning for stable ecological health monitoring. Sci Rep 15, 30000 (2025). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-15629-x

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-15629-x