Abstract

Nonmetallic pipelines are promising for medium-short distance hydrogen transport due to their lightweight, corrosion resistance, and durability. However, their low conductivity raises electrostatic safety concerns, given hydrogen’s exceptionally low ignition energy (0.017 mJ). This study employs electrostatic double-layer theory to quantify electrostatic risks under varying parameters, such as conductivity of nonmetallic materials, flow velocity, pipe diameter, and operating parameters including hydrogen pressure and temperature. The results indicate that lower electrical conductivity of nonmetallic materials, higher flow velocity and larger pipe diameter will increase the accumulation of static electricity. However, the accumulated static electricity energy in nonmetallic pipelines remains significantly below the minimum ignition potential of hydrogen, indicating a lower static electricity risk in nonmetallic pipelines. In addition, the static electricity risks of pipelines with different transportation media and pipeline materials were compared. Considering factors such as pipe surface roughness, electrical conductivity, and the ignition energy of the transportation medium, nonmetallic hydrogen pipelines exhibit lower static electricity risks. Existing applications have never reported electrostatic accidents in nonmetallic hydrogen pipelines, which also indicates that nonmetallic hydrogen pipelines have lower electrostatic risks. The results in this study could provide guidance for the application and safety evaluation of nonmetallic pipelines for hydrogen transportation.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

With the severity of environmental and energy issues, hydrogen energy has received more attention1,2. The safe transportation of hydrogen energy is crucial for its application3,4. Although metallic pipelines (e.g., API X70/X80-grade steels) remain predominant in long-distance hydrogen transportation, metallic materials are prone to hydrogen embrittlement (HE), where hydrogen infiltration into lattice defects results in brittle fracture. In contrast, non-metallic materials such as high-density polyethylene (HDPE) exhibit negligible HE susceptibility due to their amorphous microstructure5. Nonmetallic pipes, such as polyethylene and its reinforced composites, offer advantages like lightweight, good sealing, corrosion resistance, and long service life, which is an important development direction for short- and middle-distance hydrogen energy transportation in the future6. Currently, nonmetallic hydrogen transportation pipelines are in the early stages of application7,8. In the Netherlands, a 4 km long hydrogen pipeline located at the Groningen port transports green hydrogen from the North Sea to Eemshaven’s chemical and industrial facilities9. China National Pipeline Network Group has completed the first pure hydrogen blasting test of a nonmetallic pipeline under 9.45 MPa pressure. Also, there is already a large amount of nonmetallic natural gas pipeline networks available, which can also be used for hydrogen energy delivery through methods such as hydrogen doping10,11. However, the low conductivity of nonmetallic pipes leads to prolonged static electricity retention, increasing the risk of charge accumulation12. Polyethylene pipelines exhibit charge decay time constants (τ > 10³ s) orders of magnitude higher than conductive materials, allowing accumulated charges to persist through multiple transport cycles. Given hydrogen’s low minimum ignition energy of 0.017 mJ13it is easily ignited by small static electricity or other sources, raising static electricity risks for nonmetallic hydrogen transportation pipelines.

In safety risk analyses of hydrogen energy application scenarios, static electricity is one of the main sources of hydrogen explosion14. Zalosh et al.15 reported a total of 386 hydrogen explosion accidents, among which static electricity discharge, a key ignition source, was the third leading cause. In 2012, an explosion accident occurred at a hydrogen refueling station during the delivery of hydrogen gas at a pressure of 6 MPa, and the cause of the accident was static electricity generated by hydrogen gas inside the pipeline16. In a cold-tuning experiment of Venturi pipe, an explosion occurred at a liquid hydrogen flow velocity of 311 m/s, and the primary cause of the accident was static electricity generated by friction during the flow of liquid hydrogen17. These cases indicate the presence of static electricity risks in hydrogen transportation pipelines, particularly under conditions of high hydrogen flow velocity18.

Currently, research on static electricity in hydrogen transportation pipelines is limited. While foundational studies on polymeric pipelines exist in hydrocarbon transport contexts, their applicability to hydrogen systems remains unverified. Gouy-Chapman-Stern double-layer theory19,20 of static electricity is widely recognized and accepted. Building on this, Garcia et al.21 developed a model relating rush current to velocity in nonmetallic pipelines using insulating fluids. Walmsley12 systematically quantified electrostatic hazards in polyethylene petrol pipelines, yet explicitly excluded hydrogen due to its ultra-low MIE. Liu et al.22analyzed the effects of temperature, velocity, and pipe wall roughness on static electricity electrification in metallic oil pipelines through experiments and theoretical models. Wang et al.23 established a model for oil flow charging under turbulent conditions in nonmetallic pipelines, considering factors such as fluid velocity, resistivity, wall roughness, and flow state. These studies have demonstrated that factors such as velocity and conductivity have a significant impact on static electricity generation. However, due to the recent attention paid to non-metallic pipelines for hydrogen energy transportation, there is currently a lack of analysis on the static electricity risk in non-metallic hydrogen pipelines. there is currently no research on static electricity analysis for non-metallic hydrogen pipelines. Therefore, it is necessary to conduct studies on the static electricity risks in non-metallic hydrogen pipelines.

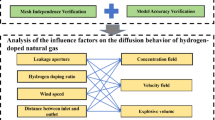

To assess the static electricity risk in nonmetallic hydrogen transportation pipelines, this study referenced the electrostatic double-layer model, integrating the electrification mechanism and theoretical calculations, and calculated the static accumulation in non-metallic hydrogen transport pipelines under different flow rates, pipe conductivity, pipe diameter, transport pressure, and temperature conditions. Factors such as conductivity of pipeline, roughness, minimum ignition energy, and impurity content were considered to compare nonmetallic hydrogen transportation pipelines with nonmetallic gas pipelines, nonmetallic oil pipelines, metallic hydrogen transportation pipelines, and metallic liquid hydrogen transportation pipelines. Additionally, based on existing cases of static electricity explosions in pipelines, the likelihood of such events in nonmetallic hydrogen transportation pipelines was comparatively analyzed. This study supports static electricity risk assessment and prevention for nonmetallic hydrogen transportation pipelines.

Static electricity theoretical model of nonmetallic hydrogen pipelines

Pipeline static electricity theoretical calculation

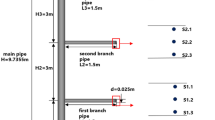

Existing pipeline static electricity analysis methods primarily are based on the electrostatic double layer theoretical model24,25. The charge transfer and distribution of the nonmetallic hydrogen transportation pipeline are as shown in Fig. 1. According to this model, positive charges in the gas phase move with the hydrogen and forms a rush current (I) in nonmetallic hydrogen transportation pipelines. The charge distribution is divided into a compact layer near the pipe wall and a diffusion layer extending into the gas, with the diffusion thickness represented by the Debye length (λ). Negative charges accumulate on the pipe wall as residual charge, while a small dissipation current flows along the wall to the ground. The static electricity potential in the pipeline is \(\:{\phi\:}_{1}\), and the static electricity potential on the pipe wall is \(\:{\phi\:}_{2}\). The key processes of static electricity phenomena include charge generation, accumulation (residual, and dissipation. Theoretically, the positive charge in the hydrogen gas equals the sum of the residual and dissipated negative charges on the pipe wall. In nonmetallic pipelines, charge accumulation occurs at a rate that surpasses its dissipation, resulting in static electricity discharge when the stored energy exceeds the minimum ignition energy of hydrogen, which may lead to an explosion.

The saturation rush current and pipe wall potential are key parameters for investigating the static electricity problem in pipelines. Based on the theoretical framework of pipeline static electricity analysis, this study examines the saturation rush current and pipe wall potential in nonmetallic pipelines used for hydrogen transport. Assuming that the charge density within hydrogen is sufficiently low to exert a negligible influence on hydrogen’s conductivity, and that conductivity is uniformly distributed across the entire flow field, with zero surge current at the pipe inlet. The analysis also incorporates considerations of fluid flow dynamics, charge relaxation effects, and pipe wall roughness. Taking molecular diffusion and other relevant factors into account, the derived formula for calculating the saturation surge current in a buried pipeline is as follows:

where \(\:C=\frac{k{\sigma\:}_{0}}{2Fe{D}_{0}^{2}}exp\left(-\frac{{W}_{\sigma\:}-2{W}_{D}}{kT}\right)\frac{N{U}_{m}^{n}}{T}\), the Debye length is \(\:\lambda\:=\sqrt{{D}_{m}\tau\:}\), and the fluid relaxation time is \(\:\tau\:=\frac{\epsilon\:}{{\sigma\:}_{1}}\); k is the Boltzmann constant, J/K; F is the Faraday constant, C/mol; e is the unit electron charge, C; T is the Kelvin temperature, K;\(\:\:{U}_{m}\) is the average flow velocity, m/s;\(\:\:{W}_{\sigma\:}\) and\(\:{\:W}_{D}\) are the activation energy of conductivity and the molecular diffusion coefficient, respectively;\(\:\:{\sigma\:}_{0}\) and D0 are the coefficient terms in the expression of fluid conductivity and the molecular diffusion coefficient in the form of activation energy, respectively; N and n are corrections for causes such as fluid aging and impurities generated; Dm is the molecular diffusion coefficient, m2/s;\(\:\:\epsilon\:\) is the permittivity of hydrogen gas, F/m;\(\:\:{\sigma\:}_{1}\) is the hydrogen conductivity, S/m; and r is the pipeline internal radius, m.

Considering parameters such as the rush current, pipeline length, pipeline and hydrogen conductivity, the calculation formula for the variation in the wall potential of the buried pipeline versus position is shown in the following equation. The subsequent comparison and analysis of the potentials are based on their absolute values.

of which, \(\:\left\{\begin{array}{c}{\beta\:}_{1}=2\pi\:{\sigma\:}_{2}/ln\left(1+d/r\right)\:\\\:{\beta\:}_{2}=\pi\:\left[{r}^{2}{\sigma\:}_{1}+\left(r+d/3\right)d{\sigma\:}_{2}+2r{\sigma\:}_{t}\right]\\\:{L}_{a}=\sqrt{\frac{{\beta\:}_{2}}{{\beta\:}_{1}}}\\\:\alpha\:=\tau\:{U}_{m}\end{array}\right.\)

where I0 is the rush current at the pipe entrance, A; x is the axial coordinate, m; L is the length of the pipeline, m;\(\:\:{\sigma\:}_{2}\) is the conductivity of pipeline, S/m; and\(\:\:{\sigma\:}_{t}\) is the wall conductivity, S/m.

Pipeline static electricity theoretical calculation parameters

The correction factors and quantify the effects of pipe wall roughness and impurity accumulation on static electricity, with specific values typically obtained through experimental testing. According to existing research, for nonmetallic petroleum pipelines ranges from 1 to 40, and ranges from 1 to 3.322,23. In this study, calculations are conducted on an HDPE pipeline with a hydrogen velocity of 10 m/s, an outer diameter of 450 mm, and an SDR11 wall thickness of 41 mm. The variations in saturation rush current and saturation potential with respect to factors and are determined using Eqs. (1) and (2), as shown in Fig. 2. Results indicate that as and increase, both the saturation surge current and wall saturation potential rise. Given that and are largely influenced by pipeline roughness and impurities—and considering that nonmetallic hydrogen pipelines have similar roughness to nonmetallic oil pipelines but significantly lower impurity levels—values for and in hydrogen pipelines are theoretically lower than those for oil pipelines. Petroleum composition is complex, containing impurities such as salts, sulfur compounds, sand, and dirt at concentrations reaching several percent. In contrast, pipeline-transported hydrogen requires a purity exceeding 99.9%, restricting impurities to the ppm level (as detailed in Sect. 4.2). Since the parameters N and n are significantly influenced by pipeline roughness and impurity levels, and given that the roughness of non-metallic hydrogen pipelines is comparable to that of non-metallic petroleum pipelines but their impurity levels are significantly lower, hydrogen pipeline pressure is theoretically lower than that of petroleum pipelines. Considering the perspective of improving the safety margin, the modification Factors N and n are set to larger values of 40 and 3.3, respectively.

Theoretical potential of the static electricity ignition of hydrogen

When the energy generated by the static electricity discharge on the pipe wall exceeds the hydrogen’s minimum ignition energy, there is a risk of hydrogen explosion. Based on the minimum ignition energy, the corresponding ignition potential \(\:\phi\:\)min can be derived using Eq. (3), while the pipe wall potential \(\:{\phi\:}_{2}\) can be calculated via Eqs. (1) and (2). Comparing the pipe wall potential\(\:\:{\phi\:}_{2}\) with the corresponding ignition potential\(\:\:\phi\:\)min, there is a risk of static electricity when the pipe wall potential\(\:{\:\phi\:}_{2}\) exceeds the theoretical potential \(\:\phi\:\)min. The relationships among the energy, electric potential and capacitance are expressed in the following Eq.

where E is the minimum ignition energy of hydrogen, J; C is the unit capacitance of pipe, F/m; and \(\:\phi\:\)min is the corresponding minimum ignition potential, V; l is the length of the discharge body, which is the length of the static electricity discharge location, m.

Equation (3) is deformed to obtain the ignition potential \(\:\phi\:\), and the calculation formula is expressed by the following Eq.

The minimum ignition energy of hydrogen is known as \(\:E\)min. According to Eq. (4), the minimum potential for igniting hydrogen gas is determined by the unit capacitance C and the length l of the discharge body\(\:\:\phi\:\)min. The nonmetallic hydrogen pipeline is regarded as a circular pipe capacitor, and the calculation is expressed by the following Eq.

where \(\epsilon\) is the material permittivity, F/m; b is the thickness of the pipe, m; and r is the inner radius of the pipe, m.

Static electricity discharge in nonmetallic pipelines typically occurs at joints, elbows, and outlets where the fluid velocity and direction change significantly; the discharge body length ranges from a few to several tens of centimeters26. For an HDPE pipe with a 450 mm diameter and an SDR11 wall thickness of 41 mm, the relationship among discharge body length, capacitance, and hydrogen ignition potential is illustrated in Fig. 3. For a discharge body of 20 cm, the capacitance is 144 pF. In comparison, Hearn et al.26 measured the capacitance of a polyethylene pipe’s electrofusion joint at approximately 4.4 pF, while metal pipe fittings do not exceed 30 pF, which is slightly lower than the calculated values here. As shown in Fig. 3 increasing discharge body length raises capacitance, lowers hydrogen ignition potential, and increases static electricity risk. Despite the capacitance calculated by Eq. (5) is relatively large, nonmetallic hydrogen transportation pipelines remain safe, which indicates the safety and reliability of static electricity. From a conservative perspective, subsequent calculations are based on a 1-meter discharge body (capacitance of 718 pF and corresponding hydrogen ignition potential of 217.6 V), which is much longer than discharge body length.

Results and discussion

Saturation rush current and pipe wall potential

The HDPE pipeline with a 450 mm outer diameter and SDR11 was selected for analyzing saturation rush current and pipe wall potential in nonmetallic hydrogen transportation pipelines (subsequent analyses focused on the SDR11 pipeline). The variation of saturation rush current and saturation potential with pipe length are shown in Fig. 4. The pipe wall potential increases along the pipe length and rapidly reaching saturation. The saturation rush current remains constant with the variation of tube length. Since hydrogen transportation pipelines in actual projects are generally longer than 5 m, static electricity reaches saturation quickly, so subsequent potential analyses in this paper focus on the saturation state.

The saturation rush current for a 25 mm nonmetallic oil pipeline at a velocity of 0.8 m/s was approximately 10–10 A22. According to Eq. (1), the saturation rush current of nonmetallic hydrogen transportation pipeline under the same velocity and diameter conditions is approximately 10–13 A. The main reason for the difference is the lower density and purity of hydrogen compared to petroleum. The above data supports the reliability of the pipe wall potential and the saturation rush current calculation formulas used in this study.

Analysis of influencing factors

Effect of hydrogen flow velocity

The hydrogen flow velocity is a critical factor influencing static electricity in nonmetallic hydrogen transportation pipelines by affecting intermolecular collisions and local charge distribution. At higher velocity, collisions between hydrogen and the pipeline wall intensify. According to Eqs. (1) and (2), the trends in pipeline saturation rush current and pipe wall saturation potential with varying velocity for a 450 mm diameter pipe are shown in Fig. 5. As velocity increases under different pressures P and temperatures T, both the saturation rush current and pipe wall saturation potential rise. This is attributed to the increased kinetic energy and collision energy of hydrogen, which enhances the probability of charge transfer and static electricity generation. Pressure and temperature are directly proportional to the static electricity value. Increased pressure raises hydrogen density, leading to more molecular friction and higher static electricity generation. Similarly, elevated temperatures increase molecular motion, hydrogen viscosity, diffusion coefficients, and overall static electricity levels.

According to ISO/TR 15,91627, the hydrogen flow velocity in pipelines should generally not exceed 10 m/s. The calculated pipe wall saturation potential is 1.42 × 10–4 V at this velocity, which is far below the theoretical ignition potential of hydrogen (217.6 V), indicating that the generated static electricity poses no risk of igniting hydrogen. To further confirm static electricity safety, calculations at a velocity of 100 m/s show a saturation potential of 0.28 V, which remains below the minimum ignition potential. Therefore, nonmetallic hydrogen transportation pipelines are safe within normal velocities from the static electricity perspective.

Effect of the pipe diameter

The pipe diameter indirectly influences the generation and accumulation of static electricity by affecting both the contact area between the pipe wall and hydrogen and the flow dynamics of hydrogen. To examine the trends in saturation rush current and pipe wall saturation potential across various diameters, pipes with outer diameters ranging from 50 mm to 630 mm were analyzed. Based on Eqs. (1) and (2), Fig. 6 illustrates these trends at a hydrogen velocity of 10 m/s. The findings show that, across different temperature and pressure conditions, an increase in pipe diameter initially leads to a rise in both saturation rush current and wall potential, which eventually stabilize.

According to the Reynolds number formula (Eq. (6)), increasing the pipe diameter at a constant flow rate raises the Reynolds number, leading to more complex hydrogen flow dynamics and a heightened likelihood of static electricity generation from hydrogen-wall interactions, thereby increasing rush current and wall potential until reaching equilibrium. Comparisons in Fig. 6 reveal that the influence of pipe diameter on saturation rush current and wall potential is less pronounced than that of velocity. This is because pipe diameter primarily affects static electricity indirectly by altering the hydrogen flow state, whereas velocity directly impacts the energy of molecular collisions, thereby exerting a more substantial effect on static electricity generation.

where Re is the Reynolds number; ρ is the density of hydrogen gas; and µ is the viscosity of hydrogen gas.

Effect of the pipe conductivity

Pipe conductivity directly affects static electricity dissipation by influencing the dissipation current along the pipe wall. Based on Eqs. (1) and (2), Fig. 7 presents the relationship between saturation rush current and pipe wall saturation potential as a function of pipe conductivity for a 450 mm diameter pipe at a hydrogen flow velocity of 10 m/s. The results show that as pipe conductivity increases, the saturation potential of the pipe wall decreases, while the saturation rush current remains nearly constant across varying temperatures and pressures. This stability arises because the saturation rush current primarily depends on the static electricity generation process, which is influenced by factors such as flow velocity, hydrogen diffusion coefficient, and pipe wall roughness, rather than conductivity. Thus, while the rush current remains stable, increased conductivity leads to a reduction in wall potential due to accelerated charge dissipation. High conductivity facilitates charge flow to the ground, reducing static electricity accumulation on the pipe wall, whereas low-conductivity materials hinder electron movement, resulting in greater charge buildup and elevated static electricity risk. For instance, an HDPE pipe (conductivity: 10–14 S/m) exhibits a wall saturation potential of approximately − 0.142 mV, whereas a low-carbon steel pipeline (conductivity: 106 S/m) shows a potential around − 1.42 × 10–24 V, indicating a substantially lower static electricity risk in metallic pipelines.

In summary, although pipe conductivity has minimal influence on the generation of static electricity, it plays a critical role in controlling its accumulation. Improving pipe conductivity can be an effective measure to mitigate static electricity risks in engineering applications.

Analysis of natural gas blended with hydrogen pipeline

Hydrogen-blended natural gas pipelines represent an important development direction for hydrogen energy transportation. In this study, we conducted calculations for nonmetallic natural gas pipelines with varying hydrogen blending ratios to assess static electricity risk. Given the similar conductivities of natural gas and hydrogen—both approximating vacuum conditions—the conductivity value was set at 10–20 S/m for computational simplicity. An HDPE pipeline with a gas velocity of 10 m/s, a diameter of 450 mm, and SDR11 specifications was selected for analysis. The results, depicted in Fig. 8, show that under different temperatures and pressures, both the saturation rush current and pipe wall saturation potential increase linearly with higher hydrogen blending ratios. These findings indicate that increasing the hydrogen content in natural gas pipelines promotes charge generation and accumulation, primarily due to hydrogen’s higher diffusion coefficient compared to natural gas. This property enhances charge transfer efficiency, facilitating static electricity generation.

Currently, the maximum hydrogen blending ratio in natural gas pipelines is approximately 30%28. At this level, the calculated saturation rush current is 2.63\(\:\times\:\)10−6 A, and the pipe wall saturation potential is −7.43 × 10−9 V, indicating a low static electricity risk. Therefore, both pure natural gas pipelines and hydrogen-blended natural gas pipelines can be considered safe from static electricity hazards.

Mechanism analysis and practical case research

Analysis of the hydrogen electrification mechanism

The calculation results indicate that the electrostatic risk associated with nonmetallic hydrogen transportation pipelines is regarded as minimal. To further validate this conclusion, this study analyzes the mechanisms of electrostatic generators and examines existing incidents.

From the perspective of static electricity electrification mechanisms, pure gases without solid or liquid impurities generally do not generate static charges without an external energy source16. This study examines cases such as gas drainage pipes, nonmetallic gas pipelines, and gas-solid fluidized beds29,30. Currently, nonmetallic hydrogen transportation pipelines are seldom used in engineering applications. In contrast, numerous static electricity explosion incidents have been reported in nonmetallic gas drainage pipes, particularly in coal mining. For instance, in 2015, a polyethylene gas drainage pipeline in a Shanxi coal mine exploded due to static discharge, resulting in a fatality31. Research indicates that in gas drainage pipelines, static electrification primarily arises from solid particle impurities, such as coal dust and cinders, with dust concentrations generally ranging from 0 to 1.5 g/cm³32,33. Nonmetallic gas pipelines have over 70 years of application history, and the natural gas extraction process introduces higher impurity levels than hydrogen. Nevertheless, there are no documented cases of static electricity causing fires or explosions in gas transportation pipelines. In a study34 using dry nitrogen at 0.7 m/s in a gas-solid fluidized bed with polyethylene particles (density 0.92 g/cm³), the measured static potential was about 1 V, well below the 46.8 V needed to ignite hydrogen. Given hydrogen’s flammable and explosive nature, hydrogen transport pipelines demand stringent impurity control. ISO/DIS 14,68735 standard mandates an industrial hydrogen purity of at least 98%, with pure hydrogen reaching 99.999%, and limits impurities to a few parts per million—substantially lower than in the previously mentioned scenarios. Thus, nonmetallic hydrogen transportation pipelines are unlikely to be compromised by large quantities of liquid or solid impurities under adherence to national standards.

Comparison of static electricity risk assessment in different pipelines

From a pipeline perspective, wall roughness primarily influences the generation of static electricity, while conductivity affects both charge accumulation on the wall and discharge of static electricity. Increased wall roughness enhances the contact area and resistance when hydrogen gas interacts with the wall, thereby raising the likelihood of static electricity generation. Metal pipelines typically have a surface roughness of approximately 0.045 mm, whereas HDPE pipelines exhibit a roughness between 0.0015 and 0.007 mm36 lower than that of metal pipes, indicating a minimum static electricity risk for HDPE pipelines based on roughness.

In terms of conductivity, HDPE has a value of approximately 10–14 S/m37, while low-carbon steel pipes have a conductivity of 106 S/m, allowing effective static electricity dissipation and reducing the risk of charge buildup. Charge accumulation is critical for static discharge; even metal pipes will not discharge without sufficient accumulation. Consequently, the risk associated with charge accumulation is greater than that of discharge. From a conductivity standpoint, the static electricity risk is ranked as nonmetallic pipes > metal pipes.

From the perspective of the conveying medium, impurity type and concentration are crucial factors influencing static electricity generation. The medium’s conductivity is associated with charge transfer, while its minimum ignition energy (MIE) relates directly to explosion hazards. Solid and liquid impurities can collide and create friction with the pipe walls, inducing electron transfer and thereby increasing the probability of static electricity generation. For example, petroleum, as per ISO 317038, has a complex composition that includes impurities such as salts, sulfur compounds, sand, and dirt, with concentrations reaching several percent. In contrast, liquid hydrogen and hydrogen require purities exceeding 99.9%, limiting impurities to ppm levels. Natural gas, according to ISO 13,68639, often contains trace solid particles due to its formation with underground minerals.

In terms of liquids, which have higher molecular weights and stronger intermolecular forces, are more prone to static electricity generation than gases. Additionally, the MIE of a medium reflects its susceptibility to ignition by small discharge energies: the lower the MIE, the higher the risk of ignition from static electricity. Hydrogen and liquid hydrogen possess lower MIE values compared to natural gas and petroleum, making them more easily ignitable and therefore more hazardous.

Table 1 provides a summary of the physical properties of these four media. Among these media, petroleum presents a substantially higher static electricity risk. Figure 9 summarizes the relative static electricity risk assessment for the five types of transportation pipelines.

The static electricity risk assessment indicates that nonmetallic hydrogen transportation pipelines present lower static electricity risks compared to nonmetallic oil, liquid metal hydrogen, and nonmetallic natural gas pipelines. Operational data and incident records further indicate that the risk of static electricity incidents in nonmetallic hydrogen pipelines remains minimal in practice. Nonmetallic oil pipelines are favored for their portability and corrosion resistance. Since 2000, China’s Changqing Oilfield has increasingly employed polyethylene (PE) pipelines, which have been used in some projects since 2005 and are now crucial to the oilfield transportation system40. Similarly, nonmetallic gas pipelines are the dominant choice for urban gas systems in the United States, the United Kingdom, Denmark, and other countries, with over 90% of newly installed urban gas pipelines in China now being nonmetallic41. Nonmetallic coal gas and natural gas pipelines have been widely implemented in urban gas networks since the 1970s42. In contrast, metal pipelines are commonly used in high-pressure applications, such as the hydrogen refueling station in Copenhagen, which operates at pressures of 35 MPa and 70 MPa to support hydrogen fuel cell taxis43. Although nonmetallic oil pipelines show a relatively higher static electricity risk than nonmetallic hydrogen pipelines, no static discharge accidents have been reported over extended operational periods. These researches indicate that the static electricity risk of nonmetallic hydrogen transportation pipelines remains exceptionally low with current standards in pipeline design, material selection, and maintenance.

Conclusion

This study quantitatively assessed static electricity risks in nonmetallic hydrogen pipelines using electrostatic double layer theory. Despite higher static charge accumulation due to low conductivity, these pipelines remain safe, with calculated electrostatic energy six orders of magnitude below hydrogen’s ignition threshold. Factors such as higher flow velocity, temperature, larger diameters, lower material conductivity, and reduced pressure increase static accumulation. A comparative assessment across various pipeline types showed that nonmetallic and metal hydrogen pipelines pose the lowest static electricity risk, while nonmetallic oil pipelines pose the highest. Notably, no static electricity accidents have been reported in nonmetallic gas pipelines.

This research shows that the risk of static electricity explosion caused by hydrogen friction in non-metallic hydrogen transportation pipelines is minimal. The static electricity risk of natural gas mixed with hydrogen pipelines also can be almost negligible.It should be noted that if there is static electricity outside the non-metallic hydrogen transport pipeline or if t there are a large amount of particle impurities such as sand and soil mixed inside the pipeline, the static electricity risk of the pipeline still needs to be considered. Therefore, considering electrostatic safety, it is recommended to deploy online sensors to dynamically detect hydrogen impurity concentration and activate emergency mechanisms in case of extreme pollution; Mandatory installation and maintenance procedures for non-metallic pipelines (such as anti-static grounding, use of cleaning tools), strengthening personnel anti-static training and case drills; In addition, when revising the hydrogen related standards for non-metallic pipelines, it may be considered to appropriately increase the flow rate limit.

Data availability

Data is provided within the manuscript.

References

Li, H. et al. Safety of hydrogen storage and transportation: an overview on mechanisms, techniques, and challenges. Energy Rep. 8, 6258–6269 (2022).

Lu, H., Xi, D., Xiang, Y., Su, Z. & Cheng, Y. Vehicle–canine collaboration for urban pipeline methane leak detection. Nat. Cities. 2, 336–343 (2025).

Du, Y. et al. Investigation on dynamic deformation and damage of steel ribbon wound vessel for hydrogen storage under fragment impact loading. Journal Press. Vessel Technology.4, 041302 (2025).

Zhang, G. & Jiang, Z. Overview of hydrogen storage and transportation technology in China. Unconv. Resour. 3, 291–296 (2023).

Genovese, M. et al. Fluid-dynamics analyses and economic investigation of offshore hydrogen transport via steel and composite pipelines. Cell. Rep. Phys. Sci. 5, 101907 (2024).

Télessy, K., Barner, L. & Holz, F. Repurposing natural gas pipelines for hydrogen: limits and options from a case study in Germany. Int. J. Hydrog Energy. 80, 821–831 (2024).

Bayrakçıl, M. D. et al. Springer, New York,. Characterization of polyethylene pipe properties through advanced metrology techniques. In Industrial Engineering in the Industry 4.0 Era 1–15 (2024).

Yang, X. et al. Investigations on the mechanical behavior of composite pipes considering process-induced residual stress. Eng. Fract. Mech. 284, 109122 (2023).

Zhang, Q. et al. Shore hydrogen deployment problem in green ports. Comput. Oper. Res. 165, 106585 (2024).

Hassan, Q. et al. Hydrogen as an energy carrier: properties, storage methods, challenges, and future implications. Environ. Syst. Decis. 44, 327–350 (2023).

Muhammed, N. S. et al. Hydrogen production, transportation, utilization, and storage: recent advances towards sustainable energy. J. Energy Storage. 73, 109207 (2023).

Walmsley, H. L. Electrostatic ignition hazards with plastic pipes at petrol stations. J. Loss Prev. Process. Ind. 25, 263–273 (2012).

Cirrone, D. et al. Numerical study of the spark ignition of hydrogen-air mixtures at ambient and cryogenic temperature. Int. J. Hydrog Energy. 79, 353–363 (2024).

Astbury, G. & Hawksworth, S. Spontaneous ignition of hydrogen leaks: A review of postulated mechanisms. Int. J. Hydrog Energy. 32, 2178–2185 (2007).

Zalosh, R. G., Short, T. P. & Marlin, G. P. Comparative analysis of hydrogen fire and explosion incidents. Report No. RC-T-54 on https://digital.library.unt.edu/ark:/67531/metadc1188733/m2/1/high_res_d/6566131.pdf (1978).

Han, Z., Lou, R. & Shan, J. Analysis on an electrostatic accident due to hydrogen gas ejection. J. Phys. Conf. Ser. 418, 12036 (2013).

Zheng, Z. Fourteen hydrogen explosion accidents. Aerosp. China. 12, 12–14 (1999).

Ferrero, F. et al. Self-ignition of tetrafluoroethylene induced by rapid valve opening in small diameter pipes. J. Loss Prev. Process. Ind. 26, 177–185 (2013).

Allagui, A., Benaoum, H. & Olendski, O. On the Gouy–Chapman–Stern model of the electrical double-layer structure with a generalized Boltzmann factor. Phys. A. 582, 126252 (2021).

Bohinc, K., Spada, S. & Maset, S. Impact of added salt on the characteristics of electric double layer composed of charged nanoparticles. J. Mol. Liq. 385, 122117 (2023).

Vazquez-Garcia, J. et al. A critical approach to measure streaming current: case of fuels flowing through conductive and insulating polymer pipes. IEEE Trans. Ind. Appl. 41, 1335–1342 (2005).

Liu, B. et al. Experimental study on static electrification rate of oil flowing through a non-metallic pipe. J. Pet. Univ. 33, 67–73 (2020).

Wang, J. & Meng, H. Calculation of oil flow electrification current in pipeline. J. China Univ. Pet. 34, 131–135 (2010).

Knijff, L., Jia, M. & Zhang, C. Electric double layer at the metal-oxide/electrolyte interface. Preprint at https://arxiv.org/pdf/2203.05486 (2022).

Wu, J. et al. Liquid-solid contact electrification and its effect on the formation of electric double layer: an atomic-level investigation. Nano Energy. 111, 108442 (2023).

Hearn, G. L. Electrostatic ignition hazards arising from fuel flow in plastic pipelines. J. Loss Prev. Process. Ind. 15, 105–109 (2002).

ISO/TR 15916. Basic considerations for the safety of hydrogen systems. International Organ. Standardization https://www.iso.org/standard/56546.html (2015).

Kim, W. J., Park, Y. & Park, D. J. Quantitative risk assessments of hydrogen blending into transmission pipeline of natural gas. J. Loss Prev. Process. Ind. 91, 105412 (2024).

Boeck, L. R., Bauwens, C. R. L. & Dorofeev, S. B. Large-scale dust explosions in vessel-pipe systems. J. Loss Prev. Process. Ind. 82, 104980 (2023).

Schwindt, N. et al. Measurement of electrostatic charging during pneumatic conveying of powders. J. Loss Prev. Process. Ind. 49, 461–471 (2017).

Liu, C., Li, J. & Zhang, D. Fuzzy fault tree analysis and safety countermeasures for coal mine ground gas transportation system. Processes 12, 344 (2024).

Murtomaa, M. et al. Effect of particle morphology on the triboelectrification in dry powder inhalers. Int. J. Pharm. 282, 107–114 (2004).

Zhao, Q. et al. Fire extinguishing and explosion suppression characteristics of explosion suppression system with N2/APP after methane/coal dust explosion. Energy 257, 124767 (2022).

Alissa, A. & Fan, L. Electrostatic charging phenomenon in gas–liquid–solid flow systems. Chem. Eng. Sci. 62, 371–386 (2007).

ISO 14687. Hydrogen fuel quality — Product specification. International Organ. Standardization https://www.iso.org/standard/69539.html (2019).

Li, X. L. et al. Multifunctional hdpe/cnts/pw composite phase change materials with excellent thermal and electrical conductivities. J. Mater. Sci. Technol. 86, 171–179 (2021).

Adamec, V. & Calderwood, J. H. On the determination of electrical conductivity in polyethylene. J. Phys. D Appl. Phys. 14, 1487 (1981).

ISO 3170. Petroleum liquids — Manual sampling. International Organ. Standardization https://www.iso.org/standard/29283.html (2004).

ISO 13686. Natural gas — Quality designation. International Organ. Standardization https://www.iso.org/standard/53058.html (2013).

Yang, H. et al. Natural gas exploration and development in Changqing oilfield and its prospect in the 13th Five-Year plan. Nat. Gas Ind. B. 3, 291–304 (2016).

Rahimi, F., Sadeghi-Niaraki, A., Ghodousi, M., Abuhmed, T. & Choi, S. M. Temporal dynamics of urban gas pipeline risks. Sci. Rep. 14, 5509 (2024).

Yeoh, K. P. & Hui, C. W. Production of town gas from natural gas in Hong Kong for a reduction in cost and greenhouse gas emissions. J. Clean. Prod. 420, 138392 (2023).

Genovese, M. & Fragiacomo, P. Hydrogen refueling station: overview of the technological status and research enhancement. J. Energy Storage. 61, 106758 (2023).

Acknowledgements

This work was supported by Key R&D Program of Shandong Province (Grant No. 2024CXGC010311), Zhejiang Provincial Natural Science Foundation of China under Grant No. LQ24E050003, and National Natural Science Foundation of China (Grant No. 52475170).

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

Wang Guanhua performed formal analysis, investigation, and methodology development, and wrote the original draft; Shi Jianfeng conceptualized the study, developed methodology, administered the project, and supervised the research; Wang Zhongzhen conducted investigation, administered the project, and supervised the research; Yao Riwu conceptualized the study, performed formal analysis, developed methodology, and reviewed and edited the manuscript. All authors reviewed and approved the final version.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher’s note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if you modified the licensed material. You do not have permission under this licence to share adapted material derived from this article or parts of it. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Wang, G., Shi, J., Wang, Z. et al. Analysis of static electricity risks in nonmetallic pipelines for hydrogen transportation. Sci Rep 15, 32100 (2025). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-16110-5

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-16110-5