Abstract

This study aimed to design a desktop application that implements machine learning algorithms to predict dental treatment time durations, assess the accuracy of the model, and assess its clinical efficiency. The Python programming language was used to develop software that uses Machine Learning and Google SerpApi service for the prediction process. The sample consisted of 2750 records, 2500 records for training, and 250 records for testing the model. Spearman correlation test result was (r (250) = 0.96, p = < 0.001), the R2 value was (0.97), which means that the actual durations can predict 97.32% of the change in predicted durations, and the Mean Absolute Error metric, yielding a result of 2.6432 min. Age and sex of participants showed no statistically significant effect. The application of Machine Learning is promising in dentistry and the medical field to help regulate the workflow. The integration of the Google SerpApi service was successful and can be helpful in cases without training data. Also, the availability of electronic patient records is necessary in all medical facilities. Finally, Python is a powerful tool in designing software that implements Machine Learning algorithms.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Efficient patient flow management is not just a necessity, but also a promising avenue for improving hospital operations, reducing delays, and enhancing patients’ overall experience, especially with the potential of AI1. When healthcare service providers effectively manage waiting times for treatments, especially emergency treatments, with the help of AI, disease severity can be prevented from increasing, thereby improving patient outcomes2,3.

When patients progress seamlessly through the healthcare delivery system, thanks to the capacity and resource utilization improvements brought about by AI, patient satisfaction and quality of care can significantly improve4.

In recent years, new technologies have emerged that exclude direct human involvement in traditional activities. Modern information technologies are fundamentally changing the nature of medical institutions’ work5. Enhancing efficiency in patient flow and satisfaction in outpatient clinics necessitates close observation of patients’ time at different service points6,7.

Artificial Intelligence (AI) is a branch of computer science that aims to train models capable of doing activities that generally require human intelligence [8]. Based on the rapid evolution of AI in the last decade, AI applications and trained models have been developed to answer some of health organizations’ most common concerns9.

Developing technologies such as AI and machine learning (ML) are implemented widely and efficiently in the medical field10. AI is a valuable diagnostic tool5,11,12,13,14,15,16,17. A study concluded that the AI prediction results were encouraging regarding effective time management; specialized knowledge is required, but the results are promising18.

Through the utilization of AI and ML, a large amount of collected data may be examined in real time19. Designing software with programming languages will significantly improve healthcare quality in the dental field. This may result in better workflow and continuous academic development for dentists and affect patient interaction with healthcare staff20.

It is no longer uncommon for hospitals to be equipped with computerized systems capable of recording all the patient’s information. The term for these documents is electronic health records, which are used to keep information about patients currently being treated at the hospital and the current condition of the facility at any given moment. As a result of the large amount of this data, implementing algorithmic approaches to managing hospitals has become increasingly possible. As a consequence, many academics have initiated the use of ML in addition to other algorithmic approaches to address the problem of increasing the number of patients who pass through hospitals. The researchers expect that by employing this algorithmic method they will be able to develop solutions that can be applied to every hospital equipped with an electronic health record system. This will allow their solutions to be “generalizable” to the rest of the hospitals21. So, this study aimed to:

-

1.

Design and create a desktop application that can predict the duration of treatment via ML algorithms.

-

2.

Evaluate the accuracy of the application in predicting dental treatment duration.

-

3.

Assess the impact of AI prediction on clinical efficiency.

Patients and methods

This experimental study was to be conducted in multiple dental hospitals and clinics to evaluate the accuracy of supervised ML in predicting treatment durations compared to actual durations. The study also assessed the impact of ML prediction on clinical workflow efficiency. All methods were performed in accordance with the relevant guidelines and regulations of the Ethics Committee at the College of Dentistry, University of Sulaimani. The ethical committee of the College of Dentistry-University of Sulaimani approved the research project with Code No. (COD-EC-25-0077) on March 24, 2025.

Inclusion criteria

Patients undergoing common dental treatments such as fillings, root canals, periodontal treatment, tooth preparation, implant visits, orthodontic treatment, extractions, or any other dental procedures were included. Eligible participants should be 18 years or older and give informed consent for their data to be used for research purposes. At the same time, some patients under 18 were included, and informed consent was taken from the parents.

Exclusion criteria

Patients with incomplete records, emergency cases requiring immediate attention, or treatments involving complex or rare procedures were excluded.

The study uses a total of 2500 patients for machine learning and 250 cases for assessing the accuracy of the model (Fig. 1).

ML model description

This study presents a supervised and optimized hybrid system for predicting dental procedure durations. It combines machine learning models with real-time online data retrieval and clinical domain knowledge. The system architecture consists of three interconnected modules designed for accuracy, efficiency, and clinical practicality.

Machine learning core

The prediction engine employs a two-tiered modeling approach using the sklearn library and Linear Regression function from that library:

-

Procedure-Specific Models: For procedures with sufficient training samples (≥ 5 records), dedicated regression models are trained using:

X_encoded = pd.get_dummies(X, columns = cat_cols, drop_first = True).

self.models[proc_name] = LinearRegression().fit(X_encoded, y).

Features include

-

Numerical: Dentist experience (years), patient age.

-

Categorical: Patient sex, dentist specialty (one-hot encoded).

Lookup Table Fallback: Procedures with sparse data (< 5 records) use precomputed averages, avoiding unreliable model fits.

Efficiency optimizations:

-

1.

Column Alignment: Prediction inputs are dynamically reindexed to match training schema (reindex(columns = model_columns, fill_value = 0)), eliminating full dataset reprocessing.

-

2.

Memory Management: Minimal Data Frames are constructed during real-time prediction.

-

3.

Parallel Training: Models are built independently per procedure, enabling scalable additions to the procedure catalog.

Online data retrieval module

The system integrates live dental guideline searches via SerpApi:

params = { “q”: f’“{procedure_name}”dental procedure duration minutes”,

“engine”: “google”,

“api_key”: api_key}

-

Asynchronous Threading: API calls run in background threads to prevent UI blocking.

-

Regex Processing: Duration patterns are extracted from search snippets using:

time_pattern = re.compile(r‘(\d{1,3}(?:\s*to\s*|-)?\d{1,3})\s*(minute|hour)s?‘, re.IGNORECASE)

-

Unit Conversion: Hours are automatically converted to minutes (×60) for consistency.

Clinical safety mechanisms

-

Domain knowledge is embedded through:

Procedure Minimums Dictionary:

-

safety_minimums = {‘root canal’: 30, ‘tooth extraction’: 8, …}.

Enforces biologically plausible times regardless of model output.

Specialty-Adjusted Predictions:

-

Endodontists receive a 40%-time reduction for root canals.

-

General dentists use baseline estimates.

-

Mismatched specialties trigger conservative multipliers.

User interface & workflow integration

(Fig. 2).

The Tkinter GUI implements:

-

Dynamic Form Validation: Real-time checks for input completeness.

-

Progressive Disclosure: Interface elements enable/disable based on system state.

-

Comparative Insights: Displays model vs. online estimates simultaneously.

Computational performance

Benchmarking on an Intel i7-1185G7 showed:

-

Model Training: 120- 450ms per procedure (depending on sample size, the study sample size was 2500 records).

-

Prediction Latency: <15ms for dedicated models, and < 2ms for lookup table.

-

Memory Footprint: <45 MB with 10,000 procedure records.

Validation Framework.

The system employs three-tier validation:

-

1.

Input Sanitization: Type checking and range validation for numerical inputs.

-

2.

Model Confidence Checking: Fallback to averages when prediction variance exceeds thresholds.

-

3.

Clinical Plausibility Gates: Final predictions are constrained by:

final_time = max(self._get_safety_minimum(proc_name), prediction).

This architecture demonstrates how hybrid AI systems can balance computational efficiency with clinical reliability in healthcare applications. The modular design permits seamless integration of additional data sources (e.g., EHR systems) while maintaining sub-second response times critical for clinical workflows.

Data collection

Data will be sourced from direct computational entry from public and private dental clinics considering different specialties. The following variables will be collected:

-

Actual treatment duration (observed and recorded by the clinician).

-

Type of dental procedure.

-

The operator’s specialty (Specialist in the field of the procedure, General practitioner, Postgraduate student, Undergraduate student).

-

Dentist’s years of experience.

-

Patient demographic information (Age and Gender).

The actual treatment durations will be calculated. Dentists or clinic workers manually record treatment duration. All dentists will be trained to record treatment duration, from history taking to patient dismissal; patients with continuous visits to the specified clinic have been excluded from the history-taking process. This data will be the training material for the software. After collecting 2500 cases, the software has been trained on these records. Another 250 cases have used to be predicted by the software and measured by the clinician to obtain two different readings: one reading is the actual duration, and the software predicts the other.

Manual data preprocessing has been conducted to unify the type of treatments and any missing fields or misspellings, the missing fields has been dealt with by two methods:

-

1.

Irrecoverable missing data have been excluded like missing any field of the raw data.

-

2.

Minor gaps, misspelled words, and unifying different names for one procedure has been addressed computationally by finding and replacing words, for example the words filling and restoration are synonymous and have been entered into the dataset.

Statistical analysis

The data will be collected using Microsoft Excel, saved as a.csv file, and analyzed using the IBM SPSS statistical package version 29, and the DATAtab Team (2024). DATAtab: Online Statistics Calculator. DATAtab e.U. Graz, Austria. The following statistical methods will be employed:

-

Descriptive statistics to summarize predicted and actual treatment durations.

-

Paired t-tests to determine the significance of differences between predicted and actual durations regarding sex, age of the patients, years of practitioner’s experience, and the practitioner’s specialty.

-

R² Score: This metric shows how much of the prediction variance is explained by the regression model.

-

Mean Absolute Error (MAE): The average difference between predictions and the actual values.

-

A p-value of < 0.05 was considered statistically significant.

Results

Processing the data started with testing for normality. The Shapiro-Wilk test result for both the actual and predicted durations was (p-value > 0.001), which means that they significantly deviated from normality. Accordingly, non-parametric analysis was used for data processing. Descriptive statistics about the actual and predicted durations are summarized in Table 1.

The analysis with Spearman correlation indicates a statistically significant, very high positive relationship between actual and predicted durations. Increases in actual duration are associated with increases in predicted duration and vice versa (r (250) = 0.96, p = < 0.001) (Fig. 3).

The R² value was 0.97, which means that the actual durations can predict 97.32% of the change in predicted durations (Table 2).

The predictive performance of the treatment duration model was strongly evaluated using the Mean Absolute Error metric, yielding a result of 2.6432 min. This low average absolute error, relative to the data’s scale and variability (standard deviation of 24.93 min), demonstrates the model’s strong predictive accuracy and its ability to provide consistently close estimates of the actual procedure times.

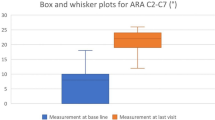

Figure 4 illustrates the actual and predicted durations in relation to the operators’ specialties. The symmetry of either side of the figure is clear evidence of the model’s accuracy and the extent of its learning.

For the actual duration and the dentist’s years of experience, the ANCOVA analysis returned (F (1, 250) = 86, p = < 0.001). Because the p-value is lower than 0.05, we conclude that the different dentists’ years of experience groups differ significantly in their impact on actual duration. The same test was run for predicted durations and returned (F(1, 241) = 85.88, p <.00), which is not different from the actual durations.

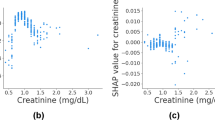

The age of individuals did not influence the durations of treatment, actual or predictable. The result of the Spearman correlation was as follows: for actual durations (r (250) = −0.02, p =.763) and for predicted durations (r (250) = 0, p =.98) (Fig. 5).

Both female and male patient groups showed p-values greater than 0.05 when analyzed with Wilcoxon Signed-Rank Test, indicating no significant difference between the actual and predicted times within each group.

The Wilcoxon Signed-Rank Test was conducted for each dental procedure, and the results showed no statistically significant difference between actual and predicted durations.

Discussion

The core element of this research involved developing a sophisticated, supervised, and optimized hybrid artificial intelligence arrangement structured for predicting dental treatment durations. This combines machine learning algorithms that deal with actual data collection, real-time online data retrieval through the SerpAPI service from Google, which permits direct retrieval of durations from web search in case of the unavailability of training data, fashioning a practical, valuable architecture.

The software was developed using Python and PyCharm Community Edition 2024. Python is a high-level, interpreted programming language known for its simplicity, readability, and versatility22.

The actual data collection comprises the core of this prediction. The datasets used and/or analysed during the current study are available from the corresponding author upon reasonable request. The source code is also available for anyone who intends to develop the software further (with the preservation of the partial ownership of the authors in case of upgrading it). The training CSV file imported dental procedures and the operator’s specialty. This means that whichever training CSV file is uploaded, the software will accommodate that training dataset. This makes the software applicable in other fields of medicine for prediction processes and workflow regulation.

The predictive engine applies a two-tiered modeling methodology employing the sklearn linear regression function. For techniques with sufficient instruction data (≥ 5 records), individual regression models were fitted, incorporating numerical characteristics like dentist experience (years) and patient age alongside categorical attributes like patient sex and dentist specialty.

The electronic health system provides a good data source23 that can be used in the training process, making applying the current software easier in hospitals and even private clinics. With this system, the simplicity of data preparation makes the use of the software in other specialties easier and no special computer skills are needed to deal with it. The communication between the model and the dataset was designed so that the software GUI adapts and modifies accordingly.

Regulation of the workflow was another goal and gap in the medical field. Software has been developed to fill the gap. The robust model design and the hybrid approach make the clinical application more valuable, which will improve the efficiency of the healthcare system24.

The result of this study showed that the accuracy of prediction using machine learning is strong and can be relied on when implementing this desktop application in the practical field. The regression line was proof of the model’s accuracy, and the R² value, which was 0.97, was a great indication that the model can successfully predict future uses. This result has been approved by other researchers in the field of machine learning and the power of prediction in the field of medicine25,26,27.

The operator specialty was also one of the factors that affected the prediction process; the model was efficient in applying this variable to the predictions.

The type of dental procedure did not affect the result and accuracy of the model; on the contrary, it was one of the key factors contributing to the model’s prediction accuracy. Another parameter was the age of individuals, as seen in Fig. 5. The symmetrical images created by the analysis indicate that the predictions were not affected by age, as the predictions remained intact.

The primary outcome of this study was the development of the prediction software, while the secondary outcome was the assessment of the software in clinical applications and workflow regulations.

Regarding the limitations of this study, they can be summarized as follows:

-

3.

Manual data analysis was used to compare the actual and predicted measurements; in reality it was done manually via SPSS and DATAtab software.

-

4.

Using the College of Dentistry and private clinics as data sources may have limited the training data.

-

5.

The training process depends on a minimum of 5 records, with any less than this Google SerpApi will replace the training. Although this is a strong point of the software, it is also a weak point in terms of depending on a less controlled data source.

Future research should assess the economic benefit of applying this method, including possible cost savings from increased efficiency, fewer delays, and better resource usage. It should also use more complicated and advanced technologies to implement deep learning concepts in prediction by recognizing patterns of work and patient histories.

Conclusions

-

1.

Using machine learning in dentistry is promising and can predict treatment durations accurately.

-

2.

Implementing the software in hospitals and private dental clinics is useful in regulating the workflow.

-

3.

Google’s SerpApi service is a powerful tool for software development. It integrates the Google search engine in the background.

-

4.

Python is a simple but powerful programming language, and the available libraries make the application of AI easy.

-

5.

Electronic patient records must be available in hospitals and clinics, as they may be training data for different aspects of management and regulations.

Data availability

The datasets used and/or analysed during the current study are available from the corresponding author upon reasonable request. The source code is also available for anyone who intends to develop the software further (with the preservation of the partial ownership of the authors in case of upgrading it).

References

Asare, E., Wang, L. & Fang, X. Conformance checking: workflow of hospitals and workflow of open-source EMRs. Ieee Access. 8, 139546–139566 (2020).

Maleki, V. S. & Forouzanfar, M. The role of AI in hospitals and clinics: transforming healthcare in the 21st century. Bioeng. (Basel). 11, 337 (2024).

Kakooei, S. et al. J. Oral Health Oral Epidemiol. 11, 140–145 (2022).

Thompson, S. M., Day, R., Garfinkel, R. & R. & In Handbook of Healthcare Operations Management: Methods and Applicationspp. 183–204 (Springer), 2013).

Chang, Z. et al. Realization of integration and working procedure on digital hospital information system. Comput. Stand. Interfaces. 25, 529–537 (2003).

Ogaji, D. S. & Mezie-Okoye, M. M. Waiting time and patient satisfaction: survey of patients seeking care at the general outpatient clinic of the university of Port Harcourt teaching hospital. Port Harcourt Med. J. 11, 148–155 (2017).

Al-Assaf, K., Bahroun, Z. & Ahmed, V. Transforming service quality in healthcare: A comprehensive review of healthcare 4.0 and its impact on healthcare service quality. Informatics 11, 96 (2024).

Mese, I., Taslicay, C. A. & Sivrioglu, A. K. Improving radiology workflow using ChatGPT and artificial intelligence. Clin. Imaging. 103, 109993 (2023).

Chen, M. & Decary, M. Artificial intelligence in healthcare: An essential guide for health leaders. Healthcare management forum. 33, 10–18 (2020). (2020).

Merkin, A., Krishnamurthi, R. & Medvedev, O. N. Machine learning, artificial intelligence and the prediction of dementia. Curr. Opin. Psych. 35, 123–129 (2022).

Al-Rawi, N. et al. The effectiveness of artificial intelligence in detection of oral cancer. Int. Dent. J. 72, 436–447 (2022).

Aminoshariae, A., Kulild, J. & Nagendrababu, V. Artificial intelligence in endodontics: current applications and future directions. J. Endod. 47, 1352–1357 (2021).

Ossowska, A., Kusiak, A. & Świetlik, D. Artificial intelligence in dentistry—Narrative review. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public. Health. 19, 3449 (2022).

Mintz, Y. & Brodie, R. Introduction to artificial intelligence in medicine. Minim. Invasive Ther. Allied Technol. 28, 73–78 (2019).

Ramesh, A. N., Kambhampati, C. & Monson, J. R. Drew pJ. Artificial intelligence in medicine. Ann. R Coll. Surg. Engl. 86, 334–338 (2004).

Chen, H. Y. et al. Artificial intelligence: emerging player in the diagnosis and treatment of digestive disease. World J. Gastroenterol. 28, 2152 (2022).

Topol, E. J. Toward the eradication of medical diagnostic errors. Science 383, eadn9602 (2024).

Xie, L., Xu, D., He, K. & Tian, X. Machine learning-based radiotherapy time prediction and treatment scheduling management. J. Appl. Clin. Med. Phys. 24, e14076 (2023).

Yazdani, M., Shahriari, S. & Haghani, M. Real-time decision support model for logistics of emergency patient transfers from hospitals via an integrated optimisation and machine learning approach. Prog Disaster Sci. 25, 100397 (2025).

Losev, F. F., Sorokina, A. A., Salakhov, A. K. & Dokin, S. P. The use of artificial intelligence in modern dentistry in the Russian federation. Stomatologiia 103, 42–45 (2024).

El-Bouri, R., Taylor, T., Youssef, A., Zhu, T. & Clifton, D. A. Machine learning in patient flow: a review. Prog Biomed. Eng. (Bristol England). 3, 022002 (2021).

Hao, J. & Ho, T. K. J. Educational Behav. Stat. 44 (3), 348–361 (2019).

Arslan, F., Marcus, J., Khatami, A., Guergachi, A. & Keshavjee, K. Towards a regulatory framework for workflow improvement in electronic medical records. Stud. Health Technol. Inf. 312, 54–58 (2024).

Khatami, A., Marcus, J., Arslan, F., Guergachi, A. & Keshavjee, K. Towards a regulatory framework for electronic medical record interoperability in Canada. Stud. Health Technol. Inf. 312, 59–63 (2024).

Arumugam, K. et al. Multiple disease prediction using machine learning algorithms. Mater. Today: Proceed. 80, 3682–3685 (2023).

Jin, W., Lin, J., Wang, P., Yang, H. & Jin, C. Screening the predictors for live birth failure in women after the first frozen embryo transfer based on the Lasso algorithm: a retrospective study. Zygote (Cambridge England). 31, 350–358 (2023).

Adnan, N. & Umer, F. Understanding deep learning - challenges and prospects. J. Pak Med. Assoc. 72, S59–S63 (2022).

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

M.M. and M.R. conceived and designed the study.T.M. wrote the introduction and the discussion of the study.K.A. and R.A collect the recordsM.M. performed the development of the softwareM.M. conducted the statistical analysis and wrote the result sectionAll authors reviewed the manuscript.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher’s note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if you modified the licensed material. You do not have permission under this licence to share adapted material derived from this article or parts of it. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Mahmood, M.A., Ahmed, K.M., Majeed, T.F. et al. Developing a hybrid machine learning model to predict treatment time duration as a workflow regulation tool in public and private dental clinics. Sci Rep 15, 31049 (2025). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-16200-4

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-16200-4