Abstract

Large language models (LLMs) hold transformative potential for medical image labeling in radiology, addressing challenges posed by linguistic variability in reports. We developed a two-stage natural language processing pipeline that combines Bidirectional Encoder Representations from Transformers (BERT) and an LLM to analyze radiology reports. In the first stage (Entity Key Classification), BERT model identifies and classifies clinically relevant entities mentioned in the text. In the second stage (Relationship Mapping), the extracted entities are incorporated into the LLM to infer relationships between entity pairs, considering actual presence of entity. The pipeline targets lesion-location mapping in chest CT and diagnosis-episode mapping in brain MRI, both of which are clinically important for structuring radiologic findings and capturing temporal patterns of disease progression. Using over 400,000 reports from Seoul Asan Medical Center, our pipeline achieved a macro F1-score of 77.39 for chest CT and 70.58 for brain MRI. These results highlight the effectiveness of integrating BERT with an LLM to enhance diagnostic accuracy in radiology report analysis.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

In the rapidly evolving landscape of artificial intelligence (AI), the integration of large language models (LLMs) into medical imaging analysis presents a transformative opportunity for healthcare1. Radiology, a field traditionally reliant on expert interpretation of computed tomography (CT) scans, X-rays, and magnetic resonance imaging (MRI), is now poised to benefit from AI-driven advancements that promise to enhance diagnostic accuracy and efficiency2.

Despite the potential of deep learning classifiers to analyze radiological images, the process of annotating these images remains labor-intensive and demands significant domain expertise3. This has led researchers to explore the utilization of existing radiology reports as a more accessible source of training data4,5,6,7. Radiology reports, often rich in clinical context and historical comparisons, offer a wealth of information that can be harnessed for AI model development8. However, discrepancies between image-based annotations and report-derived labels pose challenges due to the narrative nature of reports, which frequently include comparative analyses with prior imaging examinations9,10. These reports encapsulate nuanced details about disease progression and lesion characteristics that are not always apparent in image annotations alone.

Therefore, numerous ongoing studies aim to extract more detailed information and generate accurate labels from radiology reports. Traditional methods for extracting information from radiology reports have relied on keyword-based rules, which are prone to errors such as false positives and negatives due to the variability in report language11. Recent advancements in natural language processing (NLP), particularly with language models (LMs) like Bidirectional Encoder Representations from Transformers (BERT)12 and Generative Pre-trained Transformer-4 (GPT-4), have shown promise in overcoming these limitations by providing more accurate and context-aware information extraction capabilities3,13. For instance, fine-tuned LMs have been successfully used to classify patients based on lung cancer treatment stages from radiological reports, achieving high accuracy compared to human radiologists14. Additionally, LLMs have been applied to extract structured clinical data from imaging reports, improving the accuracy of information such as lesion characteristics and locations15.

However, there remains a critical need for methods that can seamlessly integrate these capabilities to handle complex tasks, such as matching the relationship between lesions and their anatomical locations in chest CT reports and assessing cancer episodes in brain MRI reports. Addressing such tasks is particularly important in chest CT and brain MRI, which play pivotal roles in thoracic and neurological imaging due to their high clinical demand in radiology departments16,17. Chest CT is the most commonly performed thoracic imaging modality after radiographs, enabling detailed visualization of lung parenchyma, airways, and vascular structures for accurate diagnosis of conditions like tumors or infections. Similarly, brain MRI offers superior sensitivity for detecting neurological abnormalities, such as tumors or aneurysms, making it essential for precise clinical assessment and prognosis. Extracting detailed relational information from these modalities is crucial for accurate clinical assessment and prognosis, and requires a deeper understanding of radiology narratives through carefully designed language modeling approaches.

This study addresses a critical gap in radiology report analysis: the lack of effective methods for extracting and mapping fine-grained clinical entities and their relationships from free-text reports. We propose a two-stage NLP pipeline that integrates a BERT-based model for Entity Key Classification with an LLM that performs advanced Relationship Mapping along with deeper contextual inference, such as identifying negations. The pipeline first identifies the presence of lesion and diagnosis mentions in chest CT and brain MRI reports, then leverages the LLM’s capacity for deep contextual and semantic understanding to model the relationships among those entities.

Our contributions are as follows:

-

We introduce a two-stage approach that effectively combines the lexical sensitivity of BERT-based models with the deeper contextual reasoning capabilities of LLMs.

-

Our pipeline enables complex relationship mapping with only a small number of keyword-based annotations for entity classification in the first stage.

-

The approach utilizes an open-source LLM, making it feasible for real-world healthcare applications, where the deployment of proprietary LLMs is often limited due to privacy and data sovereignty concerns.

Results

Dataset summary

In our two-stage NLP approach, a total of 447,679 reports (patients = 207,504) in the Clinical Data Warehouse (CDW) database were used in the first stage to train the entity key classification BERT model. The pre-training corpus consisted of 396,625 reports (patients = 170,622) in the CDW control group, after preprocessing and removal of duplicate texts. From the CDW case group, which included 51,054 reports, 1,000 chest CT reports and 500 brain MRI reports were randomly sampled for entity value keyword extraction annotation. These annotated reports were used to fine-tune the BERT model, while the remaining 49,554 reports were used for weak-label fine-tuning (Supplementary information, Supplementary Fig. 1).

In the second stage of relationship mapping, we utilized 417,133 reports (patients = 110,643) in the Observational Medical Outcomes Partnership Common Data Model (OMOP CDM) database after preprocessing and removing duplicated texts with the CDW annotated reports. From this dataset, 400 reports were randomly selected and pairwise annotated as the internal validation set for both chest CT and brain MRI modalities. Of these, 360 reports (90%) from each modality were used for the final evaluation of the tasks, information extraction, and relation matching (Fig. 5).

We analyzed the statistical characteristics of the report texts in the final annotated dataset, as summarized in Table 1. The average tokenized lengths per report were 56 for chest CT and 145 for brain MRI. The number of reports containing both Korean and English was 87 for chest CT and 90 for brain MRI, indicating that over 20% of the reports in both modalities included multilingual content. Among these mixed-lingual reports, the average proportion of Korean characters was 6% and 4%, respectively.

Pipeline overview

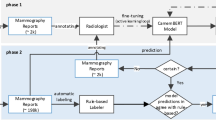

We developed a two-stage NLP pipeline that integrates a BERT-based model with Llama-3-8b18a representative open-source LLM, to extract and analyze key clinical information from chest CT and brain MRI reports. In the first stage, Entity Key Classification, fine-tuned BERT-based model12 was used to identify and classify entity keys corresponding to lesions and diagnoses. In the second stage, Relationship Mapping, Llama-3-8b was prompted without further training, to identify relationships between entity pairs, specifically lesion-location pairs in chest CT and diagnosis-episode pairs in brain MRI reports This pipeline is designed to exploit the complementary strengths of both models: the BERT model’s precision in recognizing structured medical entities, and the LLM’s ability to understand complex semantic relationships. An overview of proposed pipeline is illustrated in Fig. 1, demonstrating how these components are integrated to process radiology reports.

An overview of our two-stage modeling pipeline: 1). Entity Key Classification stage to classify the existence of entity keys on input radiology reports using pre-trained BERT encoder 2). Relationship Mapping stage to map lesion-location pairs for chest CT and diagnosis-episode pairs for brain MRI with semantic entity key classification using LLM (Llama-3-8B).

Stage 1: entity key classification performance

To evaluate classification performance at the report level, accuracy was measured as the complete correctness of extracted information. Precision was reported when model predictions were present, while recall was calculated when human annotations were available. In cases where no ground-truth annotations existed, specificity was used to assess the model’s ability to avoid generating hallucinated information.

Figure 2 shows the entity key classification performance of extracting lesions in chest CT and extracting diagnoses in brain MRI reports. With 360 internal validation test set cases, none of the lesions described in our entity keys (Table 4) were found in 49 chest CT reports and no diagnoses were found in 50 brain MRI reports. Despite having the lowest accuracy (44.4) and F1-score (80.5) for chest CT lesion key classification, the BERT model achieved the highest recall of 98.9. Our best model, which combined LLM with BERT-extracted lesion prompts, demonstrated superior performance across all metrics compared to the LLM without BERT-extracted lesion prompts. This optimized model achieved an accuracy of 73.9, an F1-score of 93.4, and a specificity of 79.6, with the latter metric particularly useful for assessing potential hallucinations in LLMs (Fig. 2). The incorporation of BERT-extracted lesion prompts substantially improved the LLM’s performance in processing and interpreting medical data, achieving a 9.7 point increase in accuracy and a 3.9 point increase in F1-score.

In contrast, BERT model’s brain MRI diagnosis key classification performance was the highest in both accuracy (80.6), which was the same as LLM with BERT extracted diagnosis prompt’s accuracy, and F1-score (91.9). LLM with BERT extracted diagnosis prompt had F1-score of 91.1 and specificity of 52.0 and were 0.8 and 12 points less than BERT’s performance, respectively. However, LLM with BERT extracted diagnosis prompt had higher scores in all the metrics than those without BERT extracted diagnosis’ performance as the same tendency of chest CT’s performance (Fig. 2; Supplementary information, Supplementary Table 4).

Entity key classification performance for chest CT and brain MRI reports. LLM without BERT extracted prompt refers to the modeling process without using BERT’s extraction information as an additional prompt string, and LLM with BERT extracted prompt uses BERT’s extraction information in the input prompt. Accuracy was calculated using the total evaluation set (n = 360) for both chest CT and brain MRI, recall was calculated using reports containing at least 1 lesion for chest CT (n = 311) and 1 diagnosis for brain MRI (n = 310), and specificity was calculated using reports that contained none of the 11 lesions (n = 49) or 5 diagnosis groups (n = 50).

Brain MRI non-tumor diagnosis entity key classification performance

A detailed entity key classification was conducted on a total of 97 reports in which non-tumor diagnoses were identified during the brain MRI entity key classification stage. Among these, 25 reports did not contain any of the following four non-tumor diagnoses: Demyelinating, Hemorrhage/Vascular lesion, Infection/Inflammation, and Stroke/Infarction. During the subsequent second entity key classification stage, 14 out of these 25 reports were correctly identified as not containing any of these four diagnoses and further analysis of these results will be provided in the Discussion section. Also, due to the false negative prediction during the first stage, the model missed 2, 20, 0, and 8 positive cases for each non-tumor diagnosis class.

Figure 3 presents the confusion matrix for each non-tumor diagnosis category. Even with the imbalanced distribution of three diagnostic classes among 97 reports—11 positive cases for demyelinating, 11 for infection/inflammation, and 28 cases for stroke/infarction—all three classes achieved high accuracy scores and F1-scores, with a minimum of 90.72 and 83.02, respectively, for stroke/infarction. However, the performance was relatively low for hemorrhage/vascular lesion, 76.29 in accuracy and 72.29 in F1-score.

Additional brain MRI entity key classification result heatmap of four non-tumor diagnoses: Demyelinating, Hemorrhage/Vascular lesion, Infection/Inflammation, and Stroke/Infarction. Additional steps were performed on 97 reports, which were classified as non-tumor diagnosis present during the brain MRI entity key classification stage.

Stage 2: relationship mapping performance

The performance of the lesion-location relationship mapping task was evaluated at the lesion level using the proposed LLM with BERT approach (Table 2). The overall macro average accuracy was 56.13, with an F1-score of 77.39. The accuracy score was relatively lower since the F1-score measures the proportion of correctly predicted location matches within each lesion, while the accuracy metric is more stringent, as it only counts a match as correct when all locations were correctly identified for a given lesion. The model achieved the highest performance for mass in chest CT scans (n = 60), with an accuracy of 80.00 and an F1-score of 89.55. In contrast, the lowest performance was observed for fibrosis (n = 98), with an accuracy of 40.82 and an F1-score of 64.00. For most chest CT lesions, the model’s precision was higher than recall, except for bronchiectasis, bronchial wall thickening and interstitial thickening, where the recall score exceeded the precision score by 5.09 points, 1.13 points and 19.75 points, respectively. The largest disparity between precision and recall in locating chest CT lesions was observed in interstitial thickening, resulting in the fourth-lowest F1-score (77.78). This large disparity was followed by atelectasis, which had the third-lowest F1-score (74.49) for lesion-location matching in chest CT reports. The LLM with BERT method consistently outperformed the rule-based method across most lesion types and evaluation metrics. Notably, the macro-averaged F1 score showed an improvement of approximately 34.42 points. For bronchial wall thickening and interstitial thickening, the rule-based method yielded a performance of 0 in certain metrics. Detailed F1-score measure for each lesion-location pair is shown in Supplementary information, Supplementary Fig. 7.

The brain MRI diagnosis-episode relationship mapping task was evaluated on a per-diagnosis basis for malignant tumors using the LLM with BERT approach (Table 3). For brain MRI reports, the overall macro average accuracy in matching malignant tumor diagnoses with their corresponding episodes was 63.12, with an F1-score of 70.58. The accuracy score was comparatively lower because it only considers a match correct when all episodes are accurately identified for a given brain MRI malignant tumor diagnosis, while the F1-score measures the proportion of correctly predicted episode matches within each diagnosis. In brain MRI analysis of malignant tumors, the model demonstrated the highest performance for matching episodes to lymphoma diagnoses, achieving an F1-score of 72.69. Conversely, the poorest performance was observed in matching episodes for metastasis diagnoses, with an F1-score of 69.07 and an accuracy of 48.5. A significant disparity between precision and recall was noted for glioma, where recall exceeded precision by 27.54 points. Both glioma and metastasis exhibited higher recall scores, indicating that the presence of multiple episode types within a single report may have negatively impacted accuracy and precision. Compared to chest CT, the macro-average scores showed 6.99 points increase in accuracy but a 6.81% point decrease in the F1-score. The rule-based baseline demonstrated substantially lower performance than the proposed model across all macro-averaged metrics except for precision. In particular, the difference in macro-average F1 score was 31.06 points. Detailed F1-score measure for each diagnosis-episode pair is shown in Supplementary information, Supplementary Fig. 8.

Assessment of patient progression in brain MRI reports using a comparative pipeline

In our proposed pipeline for brain MRI report analysis, comparisons were made with preceding reports to evaluate changes over time. Within the CDM database, a total of 7,096 patients and 27,028 reports were included, yielding an average of 3.8 reports per patient. The number of reports per patient ranged from 1 to 43, with a median of 2 reports. The average time interval between successive reports was 128.8 days, with a maximum of 3,635 days and a median of 66 days. To assess the progression status of patients over time, our pipeline was applied to the remaining CDM data. The episode mapping performed by the LLM model achieved an F1-score of 70.58, with a higher recall of 73.31, demonstrating the model’s strong ability to capture positive episode changes. We first applied entity key classification stage, which achieved an F1-score of 91.1 during internal validation, and filtered out reports lacking malignant tumor diagnoses from the first stage output. Also, patients with less than three sequential reports were excluded. Then the second step, episode mapping, was applied to the remaining set, including 999 reports classified with glioma existence, 733 reports with lymphoma, and 10,712 reports with metastasis.

Even though multiple diagnoses and episodes could be classified throughout our pipeline, we only used the reports with single diagnosis and episode, and patients with single diagnosis along the sequence of reports for better analysis. Figure 4 shows episode changes among the total of 1,707 patients after applying the above filters. Within each patient’s sequence of reports, the count was incremented only when there was a change in the episode label, limited to a maximum of four changes. For metastasis and glioma, the majority of patients had a progression episode as their first episode, whereas lymphoma patients more commonly had an improvement episode first. Overall, across all entity key labels, episodes often changed to a different label rather than remaining the same. The detailed transitions are provided in Supplementary information, Supplementary Table 7.

Sankey diagram illustrating the episode change of three malignant tumor diagnoses up to 5 time steps. The diagram begins with three initial nodes representing the cancer diagnoses: Metastasis (blue), Glioma (red), and Lymphoma (green). Links carry the diagnosis colors and connect to subsequent nodes representing time-step-specific episode states: Progression (orange), Stable (light blue), and Improvement (yellow). The flows visualize transitions across up to 5 time steps (t0 ~ t4), with link thickness indicating transition counts.

Discussion

Superiority of the integrated pipeline in entity classification

Our entity classification task achieved an improved macro-average F1-score of 93.4. To evaluate classification performance, McNemar’s test was used to assess pairwise disagreements among BERT, LLM, and our integrated pipeline. For chest CT reports, the integrated pipeline demonstrated statistically significant improvements over both individual models. In brain MRI reports, it significantly outperformed the LLM and showed comparable performance to the BERT model. These results were further supported by the 95% confidence intervals derived from bootstrap analysis of per-report F1-score (Supplementary information, Supplementary Figs. 9–10; Supplementary Table 5). Together, these findings provide statistical evidence that our approach is more effective for entity classification than using either BERT or LLM alone, across both chest CT and brain MRI datasets.

To better understand the observed performance gains, we analyzed the classification behavior of each model in detail. The BERT-based entity key classification performance showed a distinct pattern in lesion detection (Supplementary information, Supplementary Fig. 6). While the model demonstrated strong sensitivity with only 8 false negatives across 11 lesion types including zero false negatives for 7 lesion categories, it generated 371 false positives out of the total 3,960 predictions (9.4%). This led to the highest recall but the lowest precision among all models. This trade-off likely stems from the BERT model’s training approach: while it effectively learned to identify lesion-related keywords from our keyword-annotated training data, including various typographical and syntactic variations, it struggled in understanding complex semantic contexts such as negations.

The challenge of negation handling in medical texts has been well-documented in previous research. Studies have shown that BERT models often struggle with negation prediction19while larger language models typically demonstrate relative insensitivity to negated contexts20. Our internal validation test set analysis confirmed this limitation. For reports containing negated lesions (n = 186), BERT correctly classified only 1 report (0.5%), while our two-stage pipeline correctly classified 136 reports (73.1%). For reports without any negated lesions (n = 174), BERT correctly classified 159 reports (91.4%), while our pipeline correctly classified 130 reports (74.7%; Supplementary information, Supplementary Table 8). A chi-square test revealed a highly significant performance difference between negated and non-negated reports for BERT (χ2 ≈ 300.46, p < 0.001), suggesting that the BERT model is particularly sensitive to negation. In contrast, our proposed pipeline showed no statistically significant performance difference (χ2 ≈ 0.12, p = 0.73), suggesting greater robustness to negation.

These findings highlight two key insights. First, they demonstrate the complementary strengths of both models: BERT’s high sensitivity in keyword detection and the LLM’s superior ability to understand semantic context, particularly negations. Second, they validate the design of our two-stage architecture. The initial BERT stage ensures comprehensive lesion detection with high recall, while the subsequent LLM stage refines these outputs by incorporating deeper understanding, effectively filtering out false positives and handling negated contexts (Supplementary information, Supplementary Fig. 5). Overall, this architecture achieves a more balanced and robust performance than either model alone (Supplementary information, Supplementary Table 9).

Also, for the brain MRI entity classification performance, the initial identification of non-tumor diagnoses resulted in 97 positive samples, with 25 false positives, indicating a challenge in preliminary classification accuracy (Fig. 2). Interestingly, the second stage of our pipeline demonstrated improved accuracy in handling false positive non-tumor cases. Figure 3, depicting the detailed classification results, shows that 14 of the 25 false-positive samples were correctly reclassified as negative during the detailed entity key classification of non-tumor diagnoses. This improvement stems from the refinement in our prompting strategy: while the initial stage prompted the model to identify potential non-tumor diagnoses broadly, the second stage implemented more specific, targeted classification tasks for each of the four non-tumor diagnosis types. This finding highlights the critical importance of precise prompt engineering in LLM applications.

Context-aware relationship mapping beyond rule-based methods

Our integrated pipeline goes beyond disease detection by accurately mapping the corresponding locations and episodes for each identified disease, further enhancing its clinical applicability. While the rule-based mapping approach occasionally achieved higher precision, it showed significantly lower accuracy, recall and F1-score. The high precision observed in rule-based matching can be attributed to its strict criteria, where relationships are considered matched only if the lesion and location entities appear within the same sentence. In such cases, true relationships are highly likely to be captured, resulting in high precision. However, the considerably lower recall and overall accuracy indicate that a large number of valid relationships span across sentences and are thus missed by the rule-based approach. This suggests that sentence-level co-occurrence is insufficient to comprehensively capture the full range of meaningful relationship mappings and rule-based approach is only effective when clear keyword matches are present. In contrast, our integrated pipeline leverages the LLM’s ability to interpret the full context of the report, enabling more accurate and robust mapping compared to the rule-based baseline.

The model’s performance demonstrated significant variations across different imaging modalities and lesion types. In chest CT analysis, the model showed particular strength in mapping locations for mass, achieving an F1-score of 89.55. However, it showed lower accuracy in detecting fibrosis patterns, possibly due to the complex and varied presentation of fibrotic changes in imaging reports. Brain MRI analysis presented additional challenges, resulting in lower overall F1-scores compared to chest CT tasks. This difference can be attributed to several factors: the inherent complexity of neurological conditions, the more nuanced language used in brain MRI reporting, and significant data imbalances in our dataset.

Comparison with existing methods

Prior research, such as CheXbert, reported a macro-average F1-score of 79.8 in classifying the presence of 14 observations into four categories: positive, negative, uncertain, and blank21. A subsequent study, CheX-GPT, employed a similar but reversed approach to ours by first using an LLM (GPT-4) to label 50,000 MIMIC-CXR reports and then fine-tuning BERT-based encoder for binary classification of 10 diseases22. Although CheX-GPT utilized both a BERT model and an LLM, and was trained on a substantially larger fine-tuning dataset than ours, it was evaluated on 500 manually annotated MIMIC-CXR reports and achieved a macro-average F1-score of 92.79. In comparison, our entity classification —which shares similar objectives—achieved a higher macro-average F1-score of 93.4, demonstrating competitive performance of our method even with limited supervision and smaller data volume. Also, proprietary LLMs have demonstrated promising performance across various medical tasks23surpassing existing systems in several benchmarks24. However, their application in routine clinical practice is limited due to concerns around data privacy and the substantial computing resources required. In contrast, our pipeline employs a relatively lightweight open-source LLM, which can be replaced based on the user’s specific requirements and trade-offs between performance, data privacy, and computational constraints.

Additionally, many prior approaches have attempted to convert unstructured radiology reports into structured formats using NLP techniques. However, these methods often rely heavily on named entity recognition for keyword-based label extraction25limiting their ability to capture the rich and complex semantic relationships present in clinical narratives. Recent studies have proposed various relationship annotation schemes26,27,28but face challenges in labor-intensive annotation processes and varying relationship types across different imaging modalities. Extracting these various relationships across diverse modalities and tasks through human annotation is highly laborious.

In contrast, our study focused on clinically meaningful tasks, such as lesion-location and diagnosis-episode matching, without relying on any manually annotated relationship labels. Instead, we fully utilized the LLM’s capacity to infer complex relationships directly from the radiology reports. This design enables our two-stage pipeline to be flexibly adapted to diverse relation extraction tasks with minimal keyword-based annotations.

Limitations

Our modeling pipeline depends hugely on LLM’s overall performance. We chose Llama-3-8b model among various open-source LLMs considering the data privacy when using closed-source APIs and computational resources. Despite the strong capabilities of Llama-3-8b, its relatively small parameter size imposed limitations on achieving optimal performance. However, as larger-scale open-source models such as Llama-3.1 405B become available, incorporating a larger open-source LLM into our proposed approach is expected to further improve performance in both entity classification and relationship matching.

Implications

In our research, we proposed a two-stage natural language processing pipeline capable of extracting target entity key information and matching relationships between them. By integrating advanced NLP techniques, we demonstrated that open-source large language models have significant potential to understand the sophisticated semantics underlying radiology reports. A key strength of our study is the use of a locally deployed LLM instead of public models like GPT-4, ensuring compliance with data privacy and security requirements. Despite the computational constraints of smaller models, our fine-tuned implementation demonstrates that robust performance can be achieved through thoughtful system design. This approach serves as a benchmark for institutions navigating strict privacy regulations while leveraging advanced NLP capabilities.

Also, our pipeline demonstrates applicability to radiology reports written in multiple languages. Even though more than 20% of the reports included both Korean and English, and no language normalization or translation was performed, the combined LLM with BERT-extracted lesion prompts produced robust results. Moreover, BERT and LLM’s inherent capacity to understand and interpret multiple languages suggests that our pipeline can generalize well with texts written in different linguistic settings and to reports from other institutions. Therefore, we expect that as the performance of LLMs continues to advance rapidly and their utilization deepens, increasingly complex tasks can be effectively addressed.

Future work and clinical integration

Future directions include validating system performance across varying institutional reporting styles and medical terminologies, optimizing integration with hospital information systems, and addressing data imbalance to improve detection of rare conditions. Expanding the dataset, refining prompt engineering techniques, and exploring transfer learning for different radiological domains are also essential. Additionally, extending this approach to other imaging modalities, such as ultrasound or nuclear medicine, and conducting prospective validation in clinical settings will be critical to establish its broader applicability.

To translate these advances into clinical impact, seamless integration of the system as a decision support tool is essential to minimize workflow disruption. By structuring detailed information such as lesion location and disease progression into a visually interpretable format, the system can support clinicians in rapidly assessing temporal changes, facilitating timely therapeutic decisions and improved prognosis management. Ensuring clinical safety and preserving trust will also require robust privacy protection and the implementation of human-in-the-loop safeguards, such as mandatory clinician verification of AI-generated outputs. As follow-up research, we are developing a benchmark dataset to evaluate performance across diverse LLMs and advancing image-text integrated learning to enhance radiological interpretation by aligning textual knowledge from reports with visual features. We anticipate that this approach will help bridge the gap between learned clinical knowledge and its practical implementation in imaging, potentially reaching a level suitable for routine clinical use and further advancing NLP’s role in radiology for improved information extraction, organization, and enhanced clinical care and research.

Methods

Data source and cohort definition

We mainly utilized two types of radiology reports, chest CT, brain MRI throughout our total pipeline, and additionally used brain CT reports only for pre-training purposes. This overall dataset composition is illustrated in Fig. 5. The reports were extracted from CDW and OMOP CDM at Seoul Asan Medical Center. Our cohort included patients over 18 years old who had been diagnosed with infectious lung disease or respiratory infection symptoms and had chest X-ray or CT records within one and two weeks, respectively, before and after their diagnosis, between January 1, 2010, and December 31, 2021. This chest CT cohort comprised 106,154 patients. We also included patients over 18 years old, diagnosed with brain-related lesions, tumors, or hemorrhages, who had brain MRI or CT records within two weeks before and after their emergency room visit or admission, between January 1, 2010, and December 31, 2019. This brain MRI cohort included 7,125 patients. In alignment with the criteria used for the CDM database, we also retrieved radiology reports from our CDW system, Asan BiomedicaL research Environment, ABLE system, for a keyword-based training approach which will be further described in the Model Development section. For text pre-processing, we removed symbols, except for commonly used punctuation such as commas and periods, and substituted newlines and consecutive spaces into a space.

This study was approved by the Institutional Review Boards (IRB) at Asan Medical Center (IRB No. S2022-0123-0015). All methods were performed in accordance with the relevant institutional guidelines. The study analyzed de-identified radiology reports collected for routine clinical care in a retrospective manner, IRB granted a waiver of written informed consent.

Approximately 20% of the extracted radiology reports were mixed-lingual, containing both Korean and English (Table 1). We did not perform any translation or language normalization, as most key medical terms were already written in English, and translation quality between English and non-English languages can degrade significantly in domain-specific, mixed-language contexts29. Notably, our proposed pipeline demonstrated robust performance on these mixed-lingual reports without any language-specific processing. This suggests that the approach may be generalizable to radiology reports in other multilingual clinical settings, even in the absence of additional language-specific adaptation or training.

Tasks definition

Our research focused on developing NLP techniques for the analysis of radiological reports from two distinct imaging modalities: chest CT and brain MRI. For each modality, we defined specific tasks tailored to the unique clinical requirements and characteristics of the imaging type. To ensure clinical relevance and practical utility, we derived these tasks based on scenarios and demands identified through consultation with expert radiologists. This approach allowed us to align our research objectives closely with real-world clinical needs.

In the analysis of chest CT reports, we addressed two primary tasks. The first task, disease detection, involved entity key classification to determine the presence or absence of specific respiratory diseases within the report text. This approach aimed to automatically identify and categorize various pulmonary conditions described by radiologists. The second task focused on lesion-location association, utilizing pair matching between entity keys to establish relationships between detected lesions and their anatomical locations within the chest. This task was crucial for mapping the spatial distribution of abnormalities and providing a comprehensive understanding of the patient’s pulmonary status.

For brain MRI reports, we similarly defined two distinct tasks. The first task focused on disease entity key classification, aiming to detect the presence of malignant tumors, non-malignant tumors, and non-tumor diseases, with a particular emphasis on classifying the specific types of malignant tumors. This task was designed to automatically identify and categorize various types of brain diseases based on radiological descriptions. Additionally, we developed a tumor progression assessment task, which involved entity key comparison to evaluate changes only in malignant tumors over time. This longitudinal analysis aimed to automatically determine whether tumors had improved, worsened, or remained stable between successive MRI examinations, providing valuable insights into disease progression and treatment efficacy. Additionally, we performed an extra task of classifying detailed entity keys of the brain related non-tumor diagnoses.

Entity key definition

To prevent misunderstanding of the terms used in this study, we first clarify them here. “Entity type” refers to the main categories of information to extract, such as diagnosis or location. “Entity key” refers to individual items within the entity type, such as nodule or consolidation within chest CT lesion. “Entity value” refers to the keywords that act as extraction rules for each entity key that human annotators find. We also refer to the span in the report that matches the entity values as a “mention”. Examples of each term are represented in Table 4. In chest CT reports, we focused on extracting 11 lesions and 11 locations, finally forming lesion-location pairs for 9 lesions and 11 locations. Pleural effusion and pleural thickening were excluded from the pair-matching process, as their association with the “pleural” location is inherently obvious as represented in Supplementary information, Supplementary Table 2. For brain MRI reports, we focused on 4 tumor-related diagnoses including 1 entity key of non-malignant tumors, 4 non-tumor diagnoses, and 3-episode groups, forming diagnosis-episode pairs with a specific focus on the three malignant tumor diagnoses: Glioma, Lymphoma, Metastasis (Table 4).

Data annotation process

We developed a consistent annotation process for both chest CT and brain MRI reports, while addressing the unique characteristics of each modality. Our modeling consisted of five key steps: (1) defining entity types (e.g., Lesion, Location for CT; Diagnosis, Progression Status for MRI), (2) identifying specific entity keys within each type, (3) extracting relevant keywords as entity values, (4) annotating text spans matching these values, and (5) marking entity key pairs for relationship mapping tasks.

This process was applied independently to each dataset, allowing us to capture modality-specific nuances while maintaining methodological consistency. For chest CT, we focused on respiratory diseases and lesion-location associations, while for brain MRI, we targeted malignant tumor classification and progression assessment. This approach resulted in a comprehensive annotated corpus, serving as a foundation for training and evaluating our NLP models in extracting clinically relevant information from radiological reports. Data annotation details are represented in Supplementary information, Supplementary Tables 2 and 3.

NLP approach pipeline

Our NLP pipeline was designed to process the complex nature of radiological reports, which contain critical details such as diagnoses, observed lesions, their locations, and temporal changes. The pipeline consists of two main stages. In the Entity Key Classification Stage, we employed a BERT-based model12 to identify and classify entity keys for lesions and diagnoses. This stage was crucial for accurately detecting clinical entities within the nuanced context of radiological reports. The BERT model was fine-tuned in a supervised manner on our annotated and weakly labeled reports to optimize the performance for medical text analysis. In the Relationship Mapping Stage, following entity recognition, we utilized a LLM to establish relationships between the extracted entity pairs. For chest CT reports, the LLM focused on mapping lesion-location pairs, while for brain MRI reports, it targeted diagnosis-episode pairs. This stage leveraged the LLM’s advanced language understanding capabilities to interpret complex relationships within the medical text30. This stage was conducted only with prompt engineering of LLM input, without any training procedure. Notably, for location and episode entities, which are typically represented by straightforward keywords (e.g., “right lung” or “rt. lung”), we relied solely on the LLM’s capabilities without additional entity classifying using BERT. This approach aimed to enhance the accuracy and efficiency of information extraction from medical texts, potentially improving clinical decision-making processes and facilitating large-scale analysis of radiological data.

BERT encoder model

For BERT encoder to get familiar with mixed languages (Korean and English) and medical words, we trained our own tokenizer using morpheme-aware byte-level byte pair encoding and performed masked language modeling (MLM) pre-training first to train BERT model12. We used data from the control group in the CDW database, with 5% (n = 19,832) set aside as validation data for early stopping, and the rest as training data (n = 376,793). As Park et al. demonstrated that splitting words into their morphemes can improve Korean text language modeling performance, we adopted their morpheme-aware tokenizer training approach31. Also, the presence of out-of-vocabulary tokens was prevented by using byte-level byte pair encoding32. We first initialized our model with clinically pre-trained CXR-BERT model33 and then followed the original BERT’s MLM training setup without next sentence prediction.

After pre-training on a large volume of radiology reports, supervised fine-tuning was performed as the next training step. Additional classification layers, consisting of a token-wise attention layer followed by a dense layer, were added to the pre-trained BERT encoder for the purpose of multi-label classification34. For fine-tuning, we first used 80% of the data from the annotated case group in the CDW database, in which the keywords related to each entity type were extracted as entity values, comprising 800 chest CT reports and 400 brain MRI reports. To expand the training data, we applied regular expression matching to a non-annotated CDW database case set, which comprised 23,865 chest CT reports and 21,243 brain MRI reports. In other words, we performed rule-based labeling using regular expressions to generate weakly annotated reports by detecting whether keywords from annotated data were present in the non-annotated reports. For example, even if a report contains solely an expression for glioma, such as glial tumor, it would be labeled as not containing glioma-related mentions if glial tumor was not included in the previously collected keyword list. These weakly labeled reports were used as additional fine-tuning data. The final model was then employed to classify the presence of each entity key within the radiology reports.

LLM model

To ensure data privacy, we employed the most advanced open-source local small language model, Llama-3-8b18. Since Llama-3-8b possesses a high level of language understanding, relationship mapping was conducted using two-shot in-context examples without extra parameter tuning. Instructions were given to determine mapping entity types (lesion-location pairs for chest CT, and diagnosis-episode pairs in brain MRI) within the report, with an output result template to ensure the consistency of the LLM’s output response structure. Additionally, to enhance LLM’s relationship extraction performance, we provided BERT’s diagnosis/lesion classification results as complementary information by concatenating the string “### Target Lesions:” or “### Target Diseases:” with the BERT output inside the input prompt (Supplementary information, Supplementary Figs. 1–4).

For Brain MRI, the process is conducted in the same manner as previously described. However, since the relationship mapping in Brain MRI reports differs by each diagnosis, the extraction was carried out in two steps. In Step 1, we first checked the existence of five diagnoses: three malignant tumor diagnoses (Glioma, Lymphoma, Metastasis), non-malignant tumor diagnoses, and the other non-tumor diagnoses. If any malignant tumor diagnosis was found in Step 1, we proceeded Step 2; extract the episode entity key and then match the relationship between the tumor-related entity key and the episode entity key. If the other non-tumor diagnosis was found, step 2 was performed with additional entity key classification; checking for the existence of the non-tumor diagnoses’ entity keys. The input prompts for each step can be found in Supplementary information, Supplementary Figs. 1–4.

This entire process constituted our final proposed radiology report curation process. Among 800 radiology reports, we sampled 10% of the reports, 40 reports respectively for chest CT and brain MRI, for prompt development, and used the remaining 90% as the final performance evaluation.

Rule-based relationship mapping baseline

For the relationship mapping task, we additionally implemented a simple rule-based mapping approach to serve as a baseline for comparison. Using the annotated entity values obtained during the data annotation process, we matched lesion-location pairs in chest CT or diagnosis-episode pairs in brain MRI if they appeared within the same sentence. Sentence segmentation for each report was performed using the ‘en_core_web_sm’ model provided by spaCy35.

Evaluation and statistical tests

We evaluated our overall framework using two types of tasks: The first task, Entity Key Classification evaluation, assessed how well the model could extract key information—specifically, lesion and diagnosis data—from radiology reports. The second task, Relationship Mapping evaluation, evaluated the model’s ability to correctly associate each extracted lesion and diagnosis with the corresponding location and episode information.

Since a single report may contain multiple lesions or diagnoses, the accuracy of entity key classification was measured in a binary manner: a report was considered correct only if all lesions and diagnoses were correctly extracted. We also reported precision, recall, and F1-scores for data that could be calculated, since precision cannot be calculated if the model judges no lesion or diagnosis information in the report, and recall cannot be calculated if there is no human annotated label in the report. To quantify LLM’s hallucinations, we also checked specificity score, which measures the model’s ability of correctly not extracting any information when no human annotations are present. For relationship mapping performance, evaluation was conducted on each lesion for chest CT reports (or diagnosis for brain MRI reports), as one lesion could be associated with multiple locations (Supplementary information, Supplementary Table 1). In the same way, we evaluated accuracy, precision, recall, and F1-scores for each human annotated lesion and diagnosis.

To assess the statistical significance of performance differences between models (BERT, LLM, and the integrated BERT + LLM pipeline), we conducted McNemar’s test on report-level classification outcomes. Additionally, we performed paired bootstrap resampling (1,000 iterations) to estimate 95% confidence intervals for per-report F1-score differences. The detailed results are provided in the Supplementary Information, Supplementary Table 5.

Implementation details

All experiments were conducted in a Python 3.8.10 environment using the following package versions: PyTorch 2.1.2, NumPy 1.24.4, Transformers 4.44.2, and Scikit-learn 1.3.2. Model training and inference were performed on a server equipped with two Intel(R) Xeon(R) Gold 6248R CPUs (96 logical cores), 754 GB of memory, and two NVIDIA RTX A6000 GPUs (49 GB VRAM each). For experiments involving LLMs, only a single GPU was used per run.

Data availability

The raw radiology reports are not publicly available due to patient privacy concerns. De-identified text with annotation examples and the actual model output examples are provided in the Supplementary information (Supplementary Figure 1-4, Supplementary Table 6). Annotation information (e.g., entity value keywords) is available from the corresponding author upon reasonable request.

Code availability

The trained BERT checkpoints and running scripts are available on GitHub (https://github.com/chaihoyah/radiology_report_information_extraction).

Change history

30 December 2025

The original online version of this Article was revised: The original version of this Article erroneously omitted a funding source (grant number: HI22C0471) from the Acknowledgments section. The Acknowledgments section now read: “This research was supported by a grant of the Korea Health Technology R&D Project through the Korea Health Industry Development Institute (KHIDI), funded by the Ministry of Health & Welfare, Republic of Korea (grant number: HR21C0198), by a grant 2024IP0015-1 from the Asan Institute for Life Sciences, Asan Medical Center, Seoul, Korea, and by a grant of the Healthcare Big Data Curation Technology Development Project through the Korea Health Industry Development Institute (KHIDI), funded by the Ministry of Health & Welfare, Republic of Korea (grant number : HI22C0471). We would like to thank Jung Jin Kim, Mi Sun Kim, Jung Hye Kang, and Sun Young Lee for their valuable assistance in data curation and validation of this study.” The original Article has been corrected.

Abbreviations

- AI:

-

artificial intelligence

- LLM:

-

large language model

- CT:

-

computed tomography

- MRI:

-

magnetic resonance imaging

- NLP:

-

natural language processing

- LM:

-

language model

- BERT:

-

Bidirectional Encoder Representations from Transformers

- GPT:

-

Generative Pre-trained Transformer

- CDW:

-

Clinical Data Warehouse

- CDM:

-

Common Data Model

- OMOP CDM:

-

Observational Medical Outcomes Partnership Common Data Model

References

Tian, D., Jiang, S., Zhang, L., Lu, X. & Xu, Y. The role of large Language models in medical image processing: a narrative review. Quant. Imaging Med. Surg. 14, 1108 (2023).

Zhu, Q. et al. Leveraging Professional Radiologists’ Expertise to Enhance LLMs’ Evaluation for Radiology Reports. Preprint at (2024). https://doi.org/10.48550/arXiv.2401.16578

Cai, L., Gao, J. & Zhao, D. A review of the application of deep learning in medical image classification and segmentation. Annals Translational Med. 8, 713 (2020).

Reichenpfader, D., Müller, H. & Denecke, K. A scoping review of large Language model based approaches for information extraction from radiology reports. Npj Digit. Med. 7, 1–12 (2024).

Tiu, E. et al. Expert-level detection of pathologies from unannotated chest X-ray images via self-supervised learning. Nat. Biomed. Eng. 6, 1399–1406 (2022).

D’Anniballe, V. M. et al. Multi-label annotation of text reports from computed tomography of the chest, abdomen, and pelvis using deep learning. BMC Med. Inf. Decis. Mak. 22, 102 (2022).

Pereira, C., Mendonça, S., Campilho, A. M. & Sousa, A. Teixeira lopes, C. Automated image label extraction from radiology reports — A review. Artif. Intell. Med. 149, 102814 (2024).

Lee, K. et al. Detecting ground glass opacity features in patients with lung cancer: automated extraction and longitudinal analysis via deep Learning–Based natural Language processing. JMIR AI. 2, e44537 (2023).

Jain, S. et al. VisualCheXbert: Addressing the Discrepancy Between Radiology Report Labels and Image Labels. in Proceedings of the Conference on Health, Inference, and Learning 105–115 (2021). https://doi.org/10.1145/3450439.3451862

Benger, M. et al. Factors affecting the labelling accuracy of brain MRI studies relevant for deep learning abnormality detection. Front. Radiol. 3, 1251825 (2023).

Butler, J. J. et al. From technical to understandable: artificial intelligence large Language models improve the readability of knee radiology reports. Knee Surg. Sports Traumatol. Arthrosc. 32, 1077–1086 (2024).

Devlin, J., Chang, M. W., Lee, K., Toutanova, K. & BERT Pre-training of Deep Bidirectional Transformers for Language Understanding. Preprint at (2019). https://doi.org/10.48550/arXiv.1810.04805

Nazi, Z. A. & Peng, W. Large Language models in healthcare and medical domain: A review. Informatics 11, 57 (2024).

Yasaka, K., Kanzawa, J., Kanemaru, N., Koshino, S. & Abe, O. Fine-Tuned large Language model for extracting patients on pretreatment for lung cancer from a picture archiving and communication system based on radiological reports. J. Digit. Imaging Inf. Med. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10278-024-01186-8 (2024).

Li, D., Kadav, A., Gao, A., Li, R. & Bourgon, R. Automated clinical data extraction with knowledge conditioned LLMs. in Proceedings of the 31st International Conference on Computational Linguistics: Industry Track, pages 149–162, Abu Dhabi, UAE. Association for Computational Linguistics. (2025).

Moore, J. et al. Thoracic applications of spectral CT scan. CHEST 165, 417–430 (2024).

Pushparaj, E. & Arun, A. Exploring the developments in brain MRI classification-Review study, challenges and future direction. 2023 Int. Conf. Res. Methodologies Knowl. Manage. Artif. Intell. Telecommunication Eng. (RMKMATE). 1-6 https://doi.org/10.1109/RMKMATE59243.2023.10369510 (2023).

Dubey, A. et al. The Llama 3 Herd of Models. Preprint at (2024). https://doi.org/10.48550/arXiv.2407.21783

Hossain, M. M., Chinnappa, D. & Blanco, E. An Analysis of Negation in Natural Language Understanding Corpora. in Proceedings of the 60th Annual Meeting of the Association for Computational Linguistics (Volume 2: Short Papers) (eds. Muresan, S., Nakov, P. & Villavicencio, A.) 716–723Association for Computational Linguistics, Dublin, Ireland, (2022). https://doi.org/10.18653/v1/2022.acl-short.81

Truong, T. H., Baldwin, T., Verspoor, K. & Cohn, T. Language models are not naysayers: an analysis of language models on negation benchmarks. in Proceedings of the 12th Joint Conference on Lexical and Computational Semantics (*SEM 2023) (eds. Palmer, A. & Camacho-collados, J.) 101–114Association for Computational Linguistics, Toronto, Canada, (2023). https://doi.org/10.18653/v1/2023.starsem-1.10

Smit, A. et al. CheXbert: Combining Automatic Labelers and Expert Annotations for Accurate Radiology Report Labeling Using BERT. Preprint at (2020). https://doi.org/10.48550/arXiv.2004.09167

Gu, J. et al. CheX-GPT: Harnessing Large Language Models for Enhanced Chest X-ray Report Labeling. Preprint at (2024). https://doi.org/10.48550/arXiv.2401.11505

Singhal, K. et al. Toward expert-level medical question answering with large Language models. Nat. Med. 31, 943–950 (2025).

Park, K. et al. Application of Med-PaLM 2 in the refinement of MIMIC-CXR labels. https://doi.org/10.13026/A8E5-YX97

Hassanpour, S. & Langlotz, C. P. Information extraction from multi-institutional radiology reports. Artif. Intell. Med. 66, 29–39 (2016).

Steinkamp, J. M., Chambers, C., Lalevic, D., Zafar, H. M. & Cook, T. S. Toward complete structured information extraction from radiology reports using machine learning. J. Digit. Imaging. 32, 554–564 (2019).

Lau, W., Lybarger, K., Gunn, M. L. & Yetisgen, M. Event-Based clinical finding extraction from radiology reports with Pre-trained Language model. J. Digit. Imaging. 36, 91–104 (2023).

Sugimoto, K. et al. Extracting clinical information from Japanese radiology reports using a 2-Stage deep learning approach: algorithm development and validation. JMIR Med. Inf. 11, e49041 (2023).

Qiu, P. et al. Towards Building multilingual Language model for medicine. Nat. Commun. 15, 8384 (2024).

Cascella, M. et al. The breakthrough of large Language models release for medical applications: 1-Year timeline and perspectives. J. Med. Syst. 48, 22 (2024).

Park, K., Lee, J., Jang, S. & Jung, D. An Empirical Study of Tokenization Strategies for Various Korean NLP Tasks. in Proceedings of the 1st Conference of the Asia-Pacific Chapter of the Association for Computational Linguistics and the 10th International Joint Conference on Natural Language Processing (eds. Wong, K.-F., Knight, K. & Wu, H.) 133–142Association for Computational Linguistics, Suzhou, China, (2020).

Wang, C., Cho, K. & Gu, J. Neural machine translation with Byte-Level subwords. Preprint at (2019). https://doi.org/10.48550/arXiv.1909.03341

Boecking, B. et al. Making the Most of Text Semantics to Improve Biomedical Vision–Language Processing. in Computer Vision – ECCV 2022: 17th European Conference, Tel Aviv, Israel, October 23–27, 2022, Proceedings, Part XXXVI 1–21 (Springer-Verlag, Berlin, Heidelberg, (2022). https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-031-20059-5_1

Wood, D. A. et al. Deep learning to automate the labelling of head MRI datasets for computer vision applications. Eur. Radiol. 32, 725–736 (2022).

Honnibal, M., Montani, I., Van Landeghem, S. & Boyd, A. spaCy: Industrial-strength Natural Language Processing in Python. (2020). https://spacy.io

Acknowledgements

This research was supported by a grant of the Korea Health Technology R&D Project through the Korea Health Industry Development Institute (KHIDI), funded by the Ministry of Health & Welfare, Republic of Korea (grant number: HR21C0198), by a grant 2024IP0015-1 from the Asan Institute for Life Sciences, Asan Medical Center, Seoul, Korea, and by a grant of the Healthcare Big Data Curation Technology Development Project through the Korea Health Industry Development Institute (KHIDI), funded by the Ministry of Health & Welfare, Republic of Korea (grant number : HI22C0471). We would like to thank Jung Jin Kim, Mi Sun Kim, Jung Hye Kang, and Sun Young Lee for their valuable assistance in data curation and validation of this study.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

K.S.K., K.H.L, S.M.L and J.E.P contributed to the study design. S.M.L and J.E.P provided clinical insights, identified key issues, and contributed to their refinement and conceptualization. C.H.S, D.R.E, and K.H.L developed the methodology. C.H.S. and D.R.E. conducted the experiments. C.H.S. and D.R.E. wrote first draft, and K.S.K. and K.H.L. reviewed and revised final draft. All authors approved the final version of the manuscript.

Corresponding authors

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher’s note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Supplementary Information

Below is the link to the electronic supplementary material.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if you modified the licensed material. You do not have permission under this licence to share adapted material derived from this article or parts of it. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Shin, C., Eom, D., Lee, S.M. et al. Two stage large language model approach enhancing entity classification and relationship mapping in radiology reports. Sci Rep 15, 31550 (2025). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-16213-z

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-16213-z