Abstract

This study aimed to compare the number of peripapillary perforating scleral vessels (PPSVs) between eyes with and without glaucoma. A retrospective case-control analysis was performed on patients with glaucoma and control participants who underwent swept-source optical coherence tomography (SS-OCT) at a single institution. The number of PPSVs around the optic disc was counted on deep-learning assisted en face SS-OCT images created from 6 × 6 mm2 peripapillary volumetric scans. The study included 33 eyes from 33 participants (21 eyes from 21 patients with glaucoma and 12 eyes from 12 healthy controls). The number of PPSVs was significantly lower in eyes with glaucoma (95% confidence interval [CI], 16.0–20.6) than in control eyes (95% CI, 24.2–29.0; P < 0.001). It was not associated with age in patients with glaucoma (P = 0.89). The receiver operating characteristic curve had an area under the curve of 0.95 (95% CI, 0.93–0.97); at a cutoff value of 21.50, the sensitivity and specificity for identifying glaucoma were 84.6%, and 91.7%, respectively. These outcomes suggest that the decrease in PPSVs in glaucoma may be related to perfusion loss in the retina or optic nerve, and the number of PPSVs may be a biomarker for detecting the risk of glaucoma.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Glaucoma is the leading cause of irreversible blindness worldwide, and early diagnosis and treatment are crucial for preventing vision loss1. This disease is multifactorial, with numerous reported etiologies including genetic predisposition, vascular dysregulation, and mechanical factors affecting the optic nerve head (ONH). However, despite these diverse contributing factors, intraocular pressure (IOP) remains the only modifiable risk factor targeted in current therapeutic interventions2.

Optical coherence tomography (OCT) effectively measures the retinal nerve fiber layer (RNFL) thickness, thereby facilitating the diagnosis of glaucoma. Recently, a focal perfusion defect in the capillary density of the superficial vascular plexus was demonstrated in eyes with glaucoma using OCT angiography3,4,5,6 and laser speckle flowgraphy7,8. However, retinal microvascular defects may precede structural changes or visual-field defects in glaucoma5,6. Nonetheless, the associations between decreased retinal microvasculature and decreased number of branches of the short posterior ciliary arteries (SPCAs) or restricted flow within existing vessels remain unclear.

Although scleral perforating branches are not the primary source of blood supply to the optic nerve, they may serve as a supplementary source of circulation to the optic nerve sheath and the retrobulbar portion of the optic nerve. Previous studies have reported that microcirculatory disturbances in the posterior circulation, particularly involving the SPCAs, are associated with the onset and progression of glaucoma9,10. Hayreh et al. reported that in addition to autoregulatory mechanisms, the distribution and branching patterns of the SPCAs supplying the ONH vary considerably between individuals, leading to spatial and functional heterogeneity in perfusion11,12. Furthermore, anatomical variations in the thickness and structure of the peripapillary sclera may affect the sites where these vessels penetrate, potentially predisposing to localized circulatory compromise13.

Choroidal blood flow accounts for 90% of the ocular blood supply14,15, and a reduction in this flow can lead to chronic ischemia of the entire eye. Over time, this ischemia may result in damage to the retina and optic nerve. Color Doppler imaging studies have shown that in patients with normal-tension glaucoma, blood flow velocities in the SPCAs and other ocular vessels are significantly reduced, while resistive indices are elevated16,17. These findings suggest impaired autoregulatory capacity and a limited microcirculatory reserve. Moreover, decreased systolic flow and increased vascular resistance in the SPCAs and central retinal artery have been consistently reported in normal-tension glaucoma, supporting the concept of a compromised microvascular environment contributing to disease pathogenesis18.

We previously developed an algorithm for automated segmentation of the lamina cribrosa in volumetric OCT scans using a deep-learning (DL) model19,20. This algorithm removes noise from single images and achieves high robustness across various diseases without requiring noise-free ground-truth images for training.

Based on the findings in previous studies, we focused our attention on the scleral perforating branches. We applied DL techniques to enhance vascular imaging, enabling detailed morphological analysis of the choroid through the sclera, and providing better insight into peripapillary scleral vessels (PPSVs) in eyes with and without glaucoma. We hypothesized that the findings may offer new perspectives regarding the effect of microvascular changes on glaucoma pathogenesis.

Results

Demographic data

This study included 21 eyes from 21 patients with glaucoma and 11 eyes from 11 control participants. The mean (Standard deviation; SD) age, IOP, axial length (AL), and refractive error (RE) in the glaucoma and control groups were 57.8 (13.7) and 49.3 (6.4) years, 13.7 (2.7) and 14.3 (1.6) mmHg, 24.8 (0.89) and 24.7 (1.1) mm, and − 2.6 (2.1) and − 2.3 (1.6) D, respectively. The visual field mean deviation (VFMD) in patients with glaucoma was − 8.6 (6.5) dB (range, -21.3–0.46 dB). Background characteristics such as age, sex, RE, AL, and IOP, were not significantly different between the control and age-matched young glaucoma groups; however, VFMD was significantly different between the groups. Similarly, all characteristics except age were not significantly different between the young and old glaucoma groups. Demographic and clinical characteristics are summarized in Table 1.

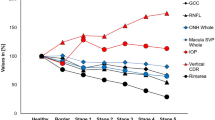

Number of PPSVs in glaucomatous eyes and diagnostic accuracy of receiver operating characteristic (ROC) analysis

Representative images of eyes with glaucoma and healthy eyes are shown in Fig. 1 and in Supplementary Videos 1 and 2, respectively. The number of PPSVs was significantly lower in the overall glaucoma group than in the control group (P < 0.001). We also analyzed a subgroup of glaucoma patients whose ages were within ± 3 years of the mean age of the control group. The number of PPSVs was significantly lower in the young glaucoma group than in the control group (mean [SD], 18.3 [3.6] vs. 26.6 [4.3]; P < 0.001) (Fig. 2). The ROC curve had an area under the curve (AUC) of 0.95 (95% confidence interval, 0.93–0.97), and the sensitivity and specificity for identifying glaucoma at a cutoff value of 21.50 were 84.6% and 91.7%, respectively. A representative case of a 49-year-old man with preperimetric glaucoma is shown in Fig. 3. The fundus photograph shows enlargement of the optic cup without RNFL defects (Fig. 3a), or visual field defects (Fig. 3b). However, OCT revealed superotemporal thinning of the RNFL (Fig. 3c). This case was independent of the study dataset. However, the patient had a reduced number of PPSVs of 21.50 (Fig. 3d and e) and is being followed-up for the potential development of glaucoma in the future.

Representative OCT images from a control participant (a, b) and a patient with glaucoma (c, d). (a) and (c) show OCT-B scans with deep-learning-based enhancement. The red lines indicate the levels of the en-face OCT images created in (b) and (d), respectively. (b) and (d) show en-face OCT images generated from the enhanced OCT B-scans. Each hyporeflective spot (red arrow) was regarded as a vessel when it was continuous in the surrounding levels of the en-face OCT images. OCT, optical coherence tomography.

Representative case of preperimetric glaucoma. (a) Fundus photograph showing increased disc cupping without RNFL defects. (b) Visual field defects are not observed; (c) OCT shows superotemporal RNFL thinning (blue arrow); (d) OCT-B scan with deep-learning enhancement. The red line in (d) indicates the level of the en-face OCT created in (e); and (e) en-face OCT image generated from the enhanced OCT-B scan. The peripapillary perforating scleral vessels (red arrows) and vascular circle of Haller and Zinn (yellow arrowhead) can be seen. RNFL, retinal nerve fiber layer; OCT, optical coherence tomography; MD, mean deviation; GHT, glaucoma hemifield test.

Correlation of PPSVs with baseline characteristics in glaucomatous eyes

The number of PPSVs was not correlated with age, VFMD, RE, AL, or IOP (all P > 0.05) (Table 2).

Discussion

This retrospective study successfully identified all blood vessels penetrating the sclera, and fewer PPSVs were observed in the glaucoma group than in the control group. PPSVs are branches of the SPCAs, which typically ramify into 10–20 branches in the peripapillary sclera, forming the choriocapillaris—a single layer of capillaries supplying the outer third of the retina21. Although previous studies using OCT have investigated these vessels in eyes with high myopia22,23, this is the first study to compare their numbers between eyes with and without glaucoma. A decrease in the number of PPSVs may impair circulation in the retinal microvasculature or ONH. This is noteworthy because glaucomatous eyes demonstrate a focal perfusion loss in the superficial vascular plexus3,4,5,6 and prelaminar region of the ONH, which receives blood supply from portions of the SPCAs that contributes to the circle of Haller and Zinn21. Such focal perfusion loss could exacerbate the development of glaucoma by reducing nutrient and oxygen delivery to the optic nerve2. Additionally, vascular impairment may increase susceptibility to oxidative stress and apoptosis, further advancing neurodegenerative processes. Studies have shown that oxidative stress markers are elevated in glaucoma, linking vascular insufficiency to cellular damage24,25.

Several studies have reported on the sequence of changes over time in glaucomatous eyes. Kiyota et al. demonstrated that reduction in the blood flow to the ONH precedes the decrease in circumpapillary RNFL thickness and corresponds to the severity of VFMD26,27. This suggests that vascular changes occur early in the disease process and may be a driving factor for structural damage in glaucoma. Similarly, in a study evaluating the temporal relationships among blood flow changes and alterations in RNFL thickness and VFMD, Higgins et al. found that VFMD changes precede blood flow changes, which in turn precede alterations in RNFL thickness28. This sequence underscores the importance of early vascular changes in the pathophysiology of glaucoma. In this study, the identification of PPSVs as a critical site for these changes highlights the importance of considering peripapillary vascular change in understanding the pathophysiology of glaucoma. As shown in Fig. 3, one control participant showed a decrease in PPSV, and an RNFL defect was subsequently confirmed using OCT. Based on these findings, the patient was diagnosed with preperimetric glaucoma and was excluded from the study. This case suggests that PPSV could potentially serve as a biomarker for detecting glaucoma.

The lack of differences in the number of PPSVs between older and younger patients with glaucoma suggests that the vessel count is consistent throughout life. Thus, the low number might be an inherent feature leading to impaired ocular circulations and possibly contributing the etiology of glaucoma. This suggests that individuals with fewer PPSVs may be at a higher risk for developing glaucoma, regardless of age. Understanding the genetic and developmental factors influencing PPSVs could provide insights into the predisposition to glaucoma and help in identifying at-risk populations for early intervention.

The vascular response to systemic hyperoxia is reduced in the ONH of eyes with glaucoma29,30,31, indicating that the ONH might be sensitive and vulnerable to hypoxia. The reduced number of PPSVs could lead to or accelerate chronic hypoxia in the ONH, which induces neurodegenerative changes. Furthermore, chronic ischemia may trigger a cascade of pathological events, including oxidative stress, mitochondrial dysfunction, and apoptotic cell death, all of which are implicated in glaucomatous optic neuropathy2. Understanding these mechanisms could facilitate development of new therapeutic interventions aimed at improving or preserving ocular blood flow, thereby mitigating the progression of glaucomatous damage.

Our findings align with those of previous studies indicating microvascular abnormalities in glaucomatous eyes2,32,33. Glaucomatous eyes exhibit various forms of microvascular impairment, including reduced blood flow and altered vascular structures, and systemic diseases that impair blood flow regulation, such as hypertension, diabetes mellitus, and obstructive sleep apnea, may contribute to the pathogenesis of glaucoma34. Hypertension can lead to microvascular damage and increased vessel-wall stiffness, potentially reducing ocular blood flow32. Conversely, hypotension can cause inadequate ONH perfusion, exacerbating ischemic damage32. Similarly, nocturnal hypoxia and increased resistance in the posterior ciliary artery have been associated with decreased RNFL thickness in obstructive sleep apnea35. Diabetes, characterized by chronic hyperglycemia, results in vascular insufficiency through osmotic damage and non-enzymatic glycosylation, increasing the risk of glaucoma36. These changes in patients with systemic conditions highlight the importance of maintaining vascular health to potentially mitigate glaucoma progression. Future studies should explore the association between systemic vascular health and ocular microvascular function to develop comprehensive management strategies for patients with glaucoma with systemic comorbidities.

This study introduced an innovative approach to examine previously unexplored anatomical sites and identified specific differences with remarkable sensitivity and specificity for distinguishing between eyes with and without glaucoma. However, this study did not track visual-field impairment or the number of PPSVs over time; focused exclusively on Japanese participants, including a considerable number of patients with normal-tension glaucoma; and had a limited sample size. Although group matching approach differs from conventional matching methods, it allowed us to effectively compare groups and examine age-related trends within the glaucoma population. The observed decrease in the number of PPSVs in glaucomatous eyes may not necessarily reflect a causal role in the pathogenesis of glaucoma. On the contrary, the reduction in PPSV count could be a secondary change resulting from glaucomatous damage. Future longitudinal studies with larger cohorts are needed to clarify the temporal sequence and causal relationship between PPSV alterations and glaucoma development. Long-term monitoring of cases with reduced PPSVs (Fig. 4) may offer important insights into early detection, disease progression, and potential strategies for managing individuals at risk.

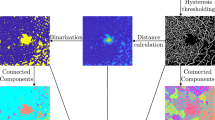

Image enhancement and en-face image creation using OCT B-scan data. (a) Original volumetric-scan image. (b) Denoised image. Deep-learning-based noise and shadow reduction have been performed for image enhancement. (c) Flattened image based on the choroid–sclera interface generated from (b). (d) En-face image generated from the flattened images. Hypo-reflective spots correspond to the cross-sections of perforating scleral vessels in the OCT B-scan image (c) (yellow arrows). OCT, optical coherence tomography.

In conclusion, the number of PPSVs was lower in eyes with glaucoma than in healthy control eyes. However, age was not associated with the number of PPSVs in eyes with glaucoma, indicating that the reduction in the number of PPSVs occurs early in the disease process. These findings suggest that a decrease in PPSVs may reflect underlying pathophysiological changes in glaucoma, such as reduced ocular perfusion and subsequent ischemia. The number of PPSVs may be a potential biomarker for glaucoma screening. However, further longitudinal studies are needed to confirm the causal relationship and explore the implications of this vascular alteration in the progression and management of glaucoma.

Methods

Study participants

This study included consecutive patients with primary open-angle glaucoma who underwent swept-source OCT (SS-OCT) between October 2017 and September 2019 at The University of Osaka Hospital. All participants underwent a complete ocular examination, including autorefractometry (ARK-530; Nidek, Aichi, Japan), AL measurement using the IOLMaster (Carl Zeiss Meditec, Jena, Germany), IOP measurement (CT-90 A; Topcon, Tokyo, Japan), slit-lamp biomicroscopy, Swedish interactive threshold algorithm standard 30-2 VF tests (Humphrey Field Analyzer; Carl Zeiss Meditec), fundus examinations, and color fundus photography (TRC-50DX; Topcon, Tokyo, Japan). The mean deviation (MD) and mean total deviation of the corresponding hemifield were evaluated. The diagnosis of glaucoma was confirmed by glaucoma specialists (N.T. and K.M.) based on the presence of RNFL defects on OCT and corresponding visual-field loss37. As part of our routine examination, we performed an anterior chamber angle assessment using the Van Herick technique with a slit-lamp microscope to differentiate between open-angle and angle-closure glaucoma. Control participants were healthy volunteers without any RNFL defects on OCT, visual-field loss, or history of ocular diseases. The right eyes were used for analysis unless they met the exclusion criteria, such as missing data or high myopia with RE<-6 D or AL> 26.5 mm.

Patients with glaucoma were recruited from a hospital setting, whereas control participants were healthy volunteers; therefore, the mean age differed between the groups. To account for this age difference, we analyzed a subgroup of young glaucoma patients whose ages were within ± 3 years of the mean age of the control group and compared them with the control group.

SS-OCT and DL algorithm

A commercially available SS-OCT device (DRI-OCT, Topcon, Tokyo, Japan) was used to obtain standard 6 × 6 mm2 volume scans of the peripapillary area with an A-scan density of 512 × 256. Since fine vessels in the original OCT volume were often obscured by speckle noise, as shown in Fig. 4a, the OCT data were processed using a previously published DL-based noise and shadow reduction algorithm19. This artificial intelligence-based denoising method enhances depth-resolved OCT volumes by reducing noise and improving the visibility of penetrating vessels in the en face images (Fig. 4b). The model was trained using the Noise2Noise paradigm, which enables the network to learn and suppress random noise using only pairs of noisy images without requiring clean ground-truth images. Specifically, a U-net-based model was trained to denoise B-scan images with a resolution of 992 × 512 pixels. OCT images of both the macula and ONH were included to increase the model’s versatility. In total, 3,895 pairs of B-scans from different retinal locations, obtained from 16 participants, were used for training. After denoising, en face images were generated by flattening the OCT data based on the choroid–sclera interface line (Fig. 4c). Hyporeflective round/oval spots on the en face images corresponded to the PPSV cross-sections. The en face OCT videos were carefully reviewed by scrolling back and forth to determine whether the hyporeflective round or oval spots corresponded with blood vessels. The course of a vessel could be traced before and after the hyporeflective spot, which facilitated identification (Fig. 4c and d). A schematic of the image enhancement and image creation process is shown in Fig. 4. Two retinal specialists and two young ophthalmologists blinded to the group allocation independently counted the number of PPSVs manually by reviewing the en face videos. The average of the four counts was used for analysis. An inter-grader analysis was performed to determine the reliability of the results (Supplementary Table 1).

Statistical analysis

Descriptive statistics such as the mean, SD, and range were computed for each variable. The number of PPSVs was compared between eyes with and without glaucoma using analysis of variance. In addition, the correlation between the number of PPSVs and baseline characteristics was analyzed in the glaucoma group. We excluded four and three eyes in the glaucoma and control groups, respectively. As control participants were healthy volunteers and glaucoma patients were recruited from a hospital setting, a difference in the mean age between the groups was observed. Patients with glaucoma were divided into two groups: a younger glaucoma group age-matched with control participants and an older glaucoma group; data from the younger glaucoma group was used for comparison. Instead of individual matching, group matching was used to minimize age-related bias while preserving sample size. A ROC curve was constructed, and the 95% confidence interval for the AUC was determined using the bootstrap method. The cutoff for the AUC was determined using the Youden index, which maximizes the sum of sensitivity and specificity. All statistical analyses were performed using JMP® Pro 13.2.1 (SAS Institute, Cary, NC). Statistical significance was set at P < 0.05.

Ethics statement

The Institutional Review Board (IRB) of The University of Osaka Hospital approved the study protocol (Work Order # 17279-6 and K21296), which adhered to the tenets of the Declaration of Helsinki and followed the Strengthening the Reporting of Observational Studies in Epidemiology (STROBE) reporting guidelines. The IRB waived the need for written informed consent of glaucoma patients because of the noninvasive and retrospective nature of the study. For healthy controls, written informed consent was obtained under the approval of the Institutional Review Board of The University of Osaka Hospital (Work Order # 17279-6).

Data availability

The datasets generated during and/or analysed during the current study are available from the corresponding author on reasonable request.

References

Tham, Y. C. et al. Global prevalence of glaucoma and projections of glaucoma burden through 2040: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Ophthalmology 121, 2081–2090 (2014).

Weinreb, R. N. et al. Primary open-angle glaucoma. Nat. Rev. Dis. Prim. 2, 16067 (2016).

Liu, L. et al. Projection-resolved optical coherence tomography angiography of the peripapillary retina in glaucoma. Am. J. Ophthalmol. 207, 99–109 (2019).

Chen, A. et al. Measuring glaucomatous focal perfusion loss in the peripapillary retina using OCT angiography. Ophthalmology 127, 484–491 (2020).

Chen, C. L. et al. Peripapillary retinal nerve fiber layer vascular microcirculation in eyes with glaucoma and single-hemifield visual field loss. JAMA Ophthalmol. 135, 461–468 (2017).

Yarmohammadi, A. et al. Peripapillary and macular vessel density in patients with primary open-angle glaucoma and unilateral visual field loss. Ophthalmology 125, 578–587 (2018).

Shiga, Y. et al. Optic nerve head blood flow, as measured by laser speckle flowgraphy, is significantly reduced in preperimetric glaucoma. Curr. Eye Res. 41, 1447–1453 (2016).

Shiga, Y. et al. Waveform analysis of ocular blood flow and the early detection of normal tension glaucoma. Invest. Ophthalmol. Vis. Sci. 54, 7699–7706 (2013).

Hayreh, S. S. The blood supply of the optic nerve head and its role in optic nerve diseases. Eye 15, 741–751 (2001).

Flammer, J. & Mozaffarieh, M. Autoregulation, a balancing act between supply and demand. Can. J. Ophthalmol. 43, 317–321 (2008).

Hayreh, S. S. & Jonas, J. B. Posterior ciliary artery circulation in health and disease: The role of anatomical variation. Prog. Retin. Eye Res. 19, 545–560 (2000).

Hayreh, S. S. Ocular blood flow in glaucoma and other ocular diseases. Prog. Retin. Eye Res. 25, 341–348 (2006).

Sigler, E. J. & Randolph, J. C. Peripapillary scleral thickness and microvascular circulation. Invest. Ophthalmol. Vis. Sci. 51, 5255–5261 (2010).

Reiner, A., Fitzgerald, M. E. C., Mar, D. & Li, C. Neural control of choroidal blood flow. Prog. Retin. Eye Res. 64, 96–130 (2018).

Agrawal, R. et al. Exploring choroidal angioarchitecture in health and disease using choroidal vascularity index. Prog. Retin. Eye Res. 77, 100829 (2020).

Kaiser, H. J. et al. Evaluation of retrobulbar circulation by color doppler imaging in normal-tension glaucoma. Am. J. Ophthalmol. 123, 320–327 (1997).

Kawai, M. & Araie, M. Color doppler imaging in glaucoma patients. Curr. Opin. Ophthalmol. 11, 113–117 (2000).

Grieshaber, M. C. & Flammer, J. Blood flow in glaucoma. Curr. Opin. Ophthalmol. 18, 133–138 (2007).

Mao, Z. et al. Deep learning based noise reduction method for automatic 3D segmentation of the anterior of lamina cribrosa in optical coherence tomography volumetric scans. Biomed. Opt. Express. 10, 5832–5851 (2019).

Fujimoto, S. et al. Three-dimensional volume calculation of intrachoroidal cavitation using deep-learning-based noise reduction of optical coherence tomography. Transl. Vis. Sci. Technol. 11, 1 (2022).

Ryan, S. J. Retina, 3rd ed. 69–70.

Pedinielli, A. et al. In vivo visualization of perforating vessels and focal scleral ectasia in pathological myopia. Invest. Ophthalmol. Vis. Sci. 54, 7637–7643 (2013).

Querques, G. et al. Lacquer cracks and perforating scleral vessels in pathologic myopia: A possible causal relationship. Am. J. Ophthalmol. 160, 759–766 (2015).

Izzotti, A., Bagnis, A. & Saccà, S. C. The role of oxidative stress in glaucoma. Mutat. Res. 612, 105–114 (2006).

Kumar, D. M. & Agarwal, N. Oxidative stress in glaucoma: A burden of evidence. J. Glaucoma 16, 334–343 (2007).

Kiyota, N., Shiga, Y., Omodaka, K. & Nakazawa, T. The relationship between choroidal blood flow and glaucoma progression in a Japanese study population. Jpn. J. Ophthalmol. 66, 425–433 (2022).

Kiyota, N., Shiga, Y., Omodaka, K., Pak, K. & Nakazawa, T. Time-course changes in optic nerve head blood flow and retinal nerve fiber layer thickness in eyes with open-angle glaucoma. Ophthalmology 128, 663–671 (2021).

Higgins, B. E., Cull, G. & Gardiner, S. K. Assessment of time lag between blood flow, retinal nerve fiber layer thickness and visual field sensitivity changes in glaucoma. Invest. Ophthalmol. Vis. Sci. 65, 7 (2024).

Kiyota, N. et al. The effect of systemic hyperoxia on optic nerve head blood flow in primary open-angle glaucoma patients. Invest. Ophthalmol. Vis. Sci. 58, 3181–3188 (2017).

Harris, A. et al. Reduced cerebrovascular blood flow velocities and vasoreactivity in open-angle glaucoma. Am. J. Ophthalmol. 135, 144–147 (2003).

Hosking, S. L. et al. Ocular haemodynamic responses to induced hypercapnia and hyperoxia in glaucoma. Br. J. Ophthalmol. 88, 406–411 (2004).

Flammer, J. & Orgül, S. Optic nerve blood-flow abnormalities in glaucoma. Prog. Retin. Eye Res. 17, 267–289 (1998).

WuDunn, D. et al. OCT angiography for the diagnosis of glaucoma: A report by the American Academy of Ophthalmology. Ophthalmology 128, 1222–1235 (2021).

Wey, S. et al. Is primary open-angle glaucoma an ocular manifestation of systemic disease? Graefes Arch. Clin. Exp. Ophthalmol. 257, 665–673 (2019).

Fındık, H. et al. The relation between retrobulbar blood flow and posterior ocular changes measured using spectral-domain optical coherence tomography in patients with obstructive sleep apnea syndrome. Int. Ophthalmol. 39, 1013–1025 (2019).

Zhao, D., Cho, J., Kim, M. H., Friedman, D. S. & Guallar, E. Diabetes, fasting glucose, and the risk of glaucoma: A meta-analysis. Ophthalmology 122, 72–78 (2015).

Kiuchi, Y. et al. The Japan glaucoma society guidelines for glaucoma. Jpn. J. Ophthalmol. 67, 189–254 (2023).

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

S.F. curated the data, performed formal analysis, prepared figures 1-4, wrote the original draft, and contributed to manuscript review and editing. Ka.M. conceived the study, developed the methodology, curated the data, performed formal analysis and validation, and contributed to manuscript review and editing. T.N. prepared figure 2 and manuscript review and editing. A.T. curated the data. Y.I. curated the data. S.L. curated the data and prepared figures 1, 3, and 4. Z.W. validated the visualization and methodology. N.S. validated the analysis. Ke.M. contributed to validation of the study. M.A. validated the visualization and methodology. K.N. supervised the study and provided resources. All authors reviewed the manuscript.

Corresponding authors

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher’s note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Supplementary Information

Below is the link to the electronic supplementary material.

Supplementary Material 2

Supplementary Material 3

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if you modified the licensed material. You do not have permission under this licence to share adapted material derived from this article or parts of it. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Fujimoto, S., Maruyama, K., Nishida, T. et al. Comparison of the number of peripapillary perforating scleral vessels between glaucomatous eyes and healthy eyes. Sci Rep 15, 31459 (2025). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-16480-w

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-16480-w