Abstract

SARS-CoV-2 pandemic has converged with the HIV epidemic. Although immunocompromised patients show an elevated risk of death due to COVID-19 compared to HIV infection, the impact remains contradictory. One reason could be the use of antiretroviral therapy (ARV). Patients with HIV receiving ARV, such as tenofovir (TDF), have fewer symptoms of COVID-19. In mice, bleomycin (BLM) induces acute lung injury, resulting in an acute inflammatory response similar to the cytokine storm and lung damage observed in COVID-19. This study aimed to evaluate the preventive role of TDF administration prior to BLM administration. A total of 64 eight-week-old C57BL/6J mice (Charles River, France), both male and female, were randomly assigned to four experimental groups (n = 8 per sex per group): (i) oral TDF administered in drinking water from day 0 to day 7, followed by oropharyngeal aspiration (OA) of saline on day 7 (TDF); (ii) oral TDF in drinking water from day 0 to day 7, followed by OA of bleomycin on day 7 (TDF-BLM); (iii) regular drinking water throughout the experiment, followed by OA of saline on day 7 (SAL); and (iv) regular drinking water throughout the experiment, followed by OA of bleomycin on day 7 (BLM). Animals were euthanized 72 h after OA (day 10), and serum and lung tissues were collected for analysis. TDF-BLM lungs showed significantly reduced bronchioalveolar lavage fluid total cell counts, specifically reduced macrophages and neutrophils counts, but an increased presence of minority lymphocytes. TDF downregulated BLM-induced levels of Il1β, Il6, TNFα, and Tgfβ mRNA. Preventive treatment with TDF counteracted BLM-induced alveolar and bronchiolar cell damage. Male mice showed more severe symptoms after BLM administration for most parameters, and the preventive action of TDF was similar in both sexes. Preventive TDF administration partially counteracted BLM-induced acute lung injury. These findings support epidemiological observations suggesting a potential benefit of TDF as a prophylactic therapy against COVID-19, at least in HIV-infected patients.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

The recent severe acute respiratory syndrome coronavirus 2 (SARS-CoV-2) pandemic has had a profound global impact and has converged with another major health pandemic, HIV infection. Although immunocompromised patients, such as those with cancer or undergoing organ transplantation show an elevated risk of death from COVID-191, the impact of HIV infection on COVID-19 outcomes remains contradictory1,2. One reason could be the use of antiretrovirals (ARVs) for HIV infection. Thus, ARVs were proposed in 2003 as a potential protective factor against SARS3. Among these, tenofovir (TDF), a nucleotide reverse transcriptase inhibitor (NRTI) is commonly employed both for the treatment of HIV, pre-exposure prophylaxis (PrEP) to prevent HIV infection, and the treatment of hepatitis B virus4,5.

During acute SARS-CoV-2 infection, the cytokine storm, characterized by elevated levels of IL6 and TNFα, has been implicated in disease severity6. Many of the pathophysiologic changes described in COVID-19 lung disease resemble those observed in pneumonitis induced by inhaled bleomycin (BLM) in mice7,8. Single-cell sequencing studies of BLM-induced lung injury in mice9 and COVID-19 lung disease10,11 have highlight the critical role of inflammatory mediators in the progression of both conditions. Autopsies findings from COVID-19 patients consistently reveal diffuse alveolar damage and acute lung injury as predominant features12. Therefore, the objective of this study was to evaluate the preventive role of TDF in mitigating BLM-induced lung injury in mice13.

Methods

Ethics statement

All animal experiments were conducted in accordance with the guidelines of the European Parliament and Council Directive 2010/63/EU and the Spanish Royal Decree 53/2013 on the protection of animals used for scientific purposes. All procedures were reviewed and approved by the CEAA/CIBIR Bioethics Committee (Ref. 00860–2023/028740). In addition, all the study was carried out in compliance with the ARRIVE guidelines (https://arriveguidelines.org).

Animals and BLM-induced acute lung injury mouse model

A total of 64 eight-week-old C57BL/6J mice (Charles River, France), both male and female, were randomly assigned to four experimental groups (n = 8 per sex per group): (i) oral TDF administered in drinking water from day 0 to day 10, followed by oropharyngeal aspiration (OA) of saline on day 7 (TDF); (ii) oral TDF in drinking water from day 0 to day 10, followed by OA of bleomycin on day 7 (TDF-BLM); (iii) regular drinking water throughout the experiment, followed by OA of saline on day 7 (SAL); and (iv) regular drinking water throughout the experiment, followed by OA of bleomycin on day 7 (BLM). Animals were euthanized 72 h after OA (day 10), and serum and lung tissues were collected for analysis. The animals were randomly assigned to receive or not receive TDF (Fig. 1A). TDF was administered orally to mice for 10 days (D0-D10); water consumption was calculated as 5 mL per day for each mouse14. The average TDF dosage was 100 mg/kg/d14. One week later (week 9) (D7 post-TDF treatment), they were randomized again and exposed to BLM by OA to induce acute lung injury. The choice of timing was based on prevention studies conducted in people living with HIV (PLWH) in which, after 7 days of treatment with TDF/FTC, protection against HIV infection was observed15.

Preventive treatment with TDF in bleomycin challenged mice reduces body weight loss. (A) Protocol to generate the four experimental groups using C57BL/6 mice (males and females, n = 8 per group and sex): (i) Oropharyngeal aspiration (OA) of saline at day (D) 7 (SAL), (ii) TDF in drinking water before SAL since D0 (TDF); (iii) OA of BLM at D7 (BLM); (iv) TDF and BLM (TDF-BLM). Animals were sacrificed at D10 and blood, BALF and lungs were collected for analyses. (B) Follow-up of body weight gain at D0, D7 and D10 in males and females challenged with BLM (D7), and under pre-treatment with TDF (D0). Mouse weight declined between D7 and D10 following BLM damage, most markedly in males, and TDF administration significantly attenuated this decline. n = 8 mice per group. #, @, $, * p < 0.05; $$,** p < 0.01; ###, @@@,, *** p < 0.001 (Student´s t-test). (C) Lung (including trachea) to body weight ratio from mice of both sexes increased after the BLM challenge but is not affected by TDF preventive administration (n = 7–8 mice per group). *p < 0.05; **p < 0.01; ***p < 0.001 (Mann-Whitney U- or Student´s t-tests). Data are expressed as mean ± SEM.

BLM (10 mg/kg) or SAL OA was delivered to the oropharyngeal cavity of mice under isoflurane anaesthesia, while the tongue was gently pulled out with forceps. Simultaneously, the nares were blocked to prevent obligated nasal breathing and forced BLM inhalation16. The mice were observed daily, weighed and all observations were recorded. Around 72 h later (D10), the OA of BLM or SAL mice were euthanized.

Serum and Bronchoalveolar lavage fluid (BALF) obtention, quantification of BALF, and lung collection

Animals were euthanized in accordance with institutional guidelines via intraperitoneal injection of sodium pentobarbital (Dolethal, 100 mg/kg in 10 mL/kg saline), followed by exsanguination. The high dose ensured rapid and humane euthanasia while minimizing distress. To preserve lung integrity for histological and biochemical analyses, thoracic procedures were avoided prior to euthanasia. Serum was obtained by centrifugation at 3000 x g for 10 min at 4 °C and stored at −80 °C until use in ELISA analyses. Bronchoalveolar lavage was performed twice (0.8 Ml phosphate-buffered saline, PBS, per wash) to collect BALF. After lavage, the lungs, including the trachea, were excised and weighed. BALF was centrifuged at 500 × g for 5 min and total protein concentration in BALF supernatants was determined using the Pierce BCA Protein Assay Kit (Thermo Fisher Scientific, Waltham, MA). Total cell counts were determined with a hemocytometer, and differential cell counts were performed on May-Grünwald/Giemsa (Sigma-Aldrich, St), counting a minimum of 300 cells per slide in a blinded manner. Cells were identified as macrophages, lymphocytes, or neutrophils based on standard morphological criteria. The right lung lobes were dissected and snap-frozen for quantitative PCR (qPCR) analysis, while the left lungs were inflated with formalin, post-fixed by immersion in formalin for 8–10 h, dehydrated, embedded in paraffin, and sectioned into 3 μm slices for histopathology and immunohistochemistry.

Histopathological and immunostaining assessments

Slides were stained with haematoxylin and eosin (H&E), observed, and photographed using a light microscope (Nikon Instruments Inc., Melville, NY). Inflamed lung areas were identified by darker H&E-stained foci and the presence of inflammatory cells, mainly lymphocytes. Two sections at different levels from six left lungs per group and sex of mice were evaluated. Lung injure score were evaluated by an expert pathologist in a blinded fashion.

CC10 and Pro-SPC antibodies were used to quantify CC10+ and SPC+ cells in the epithelial area, while Cd4 antibody was employed to evaluate pulmonary lymphocyte recruitment associated with TDF treatment. For immunostaining, paraffin-embedded sections were dewaxed and rehydrated using standard methods. Antigen retrieval was performed by immersing slides in a boiling solution (EnVision FLEX High pH GV804) for 17 min, followed by cooling in the same buffer for 30 min. Peroxidase inhibition and blocking were performed using the Novolink Polymer Detection System (Leica Biosystems, Nussloch, Germany) according to the manufacturer’s instructions. For immunohistochemical, slides were incubated at overnight at 4 °C with a primary antibody against Cd4+ (1:130; clone EPR19514; Abcam, Cambridge, UK). Sections were incubated with the Novolink Polymer Detection System (RE7150-K; Leica Biosystems, Nussloch, Germany) for 30 min, developed with 3,3′-diaminobenzidine (DAB) chromogen (K3468; Agilent Dako, Santa Clara, CA, USA), and photodocumented using a Leica DM6000B microscope equipped with a K/3 C camera (Leica Microsystems). Cd4+ staining in male mice was quantified in five different lung areas from two sections per animal (n = 5 male mice per group) in a randomized way. For fluorescence immunostaining, slides were incubated overnight at 4 °C with primary antibodies against CC10 (1:100; clone E-11; cat. no. sc-365992; Santa Cruz Biotech. Inc., Dallas, TX) and Pro-SPC (1:100; clone M-20; cat. no. sc-7706; Santa Cruz Biotech. Inc). After washing, sections were incubated for 1 h with secondary antibodies: Alexa Fluor Donkey anti-mouse 555 and anti-goat 633, both from Santa Cruz Biotech, Inc. The slides were subsequently washed, mounted in VECTASHIELD mounting medium with DAPI (Vector Laboratories, Burlingame, CA, USA), and examined using a confocal microscope (Stellaris 8 Leica Microsystems). Quantification of CC10+ and Pro-SPC+ staining areas in the terminal bronchiole epithelium was performed with Leica Application Site LAS X software (Leica Microsystems) on 6–14 terminal bronchioles per animal (n = 6 animals per group) in a randomized manner.

Lung injury score

The acute lung injury (ALI) score was calculated as described Matute-Bello et al.17. This score system includes five histological features: (A) neutrophils in the alveolar space; (B) neutrophils in the interstitial space; (C) hyaline membranes formation; (D) proteinaceous debris filling the airspace; and (E) alveolar septal thickening. Each item was assigned a score of 0, 1, or 2 based on the severity of lung injury. The final ALI score was determined using the following formula: [(20 × A) + (14 × B) + (7 × C) + (7 × D) + (2 × E)] divided by the number of fields multiplied by 100, leading to a score between zero (no lung injury) and one (severe injury) (n = 4 animals per group). Histological samples were reviewed in a blinded manner to ensure unbiased evaluation.

RNA isolation, reverse transcription and gene expression quantification via qPCR

The inferior right lung lobes were homogenized in TRIzol (15596026 Invitrogen, Carlsbad, CA, USA), and total RNA was extracted and purified using the RNA RNeasy Mini Kit (74104 Qiagen, Valencia, CA, USA). RNA samples were treated with DNase I (AM2222 Ambiom™) according to the manufacturer’s instructions. cDNA was synthesized from 1 µg of total RNA using the SuperScript III First-Strand Synthesis kit (18080051 Invitrogen) in a total volume of 30 µL following the manufacturer’s protocol. qPCR amplification was performed using SybrGreen (RR420A Takara Bio Inc., Shiga, Japan) and specific primers as follows: Glyceraldehide 3-phoshate dehydrogenase (Gadph), sense: 5´-CATGTTCCAGTATGACTCCACTC-3´, antisense: 5´-GGCCTCACCCCATTTGATGT-3´. Interleukin-6 (Il6), sense: 5´-ATGGATGCTACCAAACTGGAT-3´ and antisense: 5´-TGAAGGACTCTGGCTTTGTCT-3´. Tumor necrosis factor- α (Tnfα), sense 5´-ACGGCATGGATCTCAAAGAC-3´ and antisense 5´-AGATAGCAAATCGGCTGACG-3´. Interleukin-1 beta (Il1β), sense: 5´-CTGAACTCAACTGTGAAATGCCA-3´ and antisense: 5′-AAAGGTTTGGAAGCAGCCCT-3´. Interleukin-10 (Il10), sense: 5´-ATAACTGCACCCACTTCCCA-3´ and antisense: 5´-GGGCATCACTTCTACCAGGT-3´. Transforming growth factor- beta 1 (Tgfβ1), sense: 5´-GCAACATGTGGAACTCTACCAGAA-3´ and antisense: 5´-GACGTCAAAAGACAGCCACTCA-3´. Angiotensin I converting enzyme (peptidyl-dipeptidase A) (Ace), sense: 5´-TGAGAAAAGCACGGAGGTATCC − 3´ and antisense: 5´-AGAGTTTTGAAAGTTGCTCACATCA-3´. Angiotensin I converting enzyme (peptidyl-dipeptidase A) 2 (Ace2), sense: 5´-GGATACCTACCCTTCCTACATCAGC-3´ and antisense: 5´-CTACCCCACATATCACCAAGCA-3´. Amplification and detection of specific products were performed using the QuantStudio™ 5 system (Applied Biosystems, Foster City, CA, USA). All reactions were carried out in duplicate for each sample. Relative biomarker expression levels were calculated using the ΔΔCt method, normalized to the housekeeping gene Gapdh, as per the manufacturer’s recommendations.

Sandwich enzyme linked immunosorbent assay (ELISA)

Serum IL6 levels were measured using a mouse ELISA kit (M6000B R&D Systems). This procedure was performed according to the manufacturer’s instructions.

Statistics

All data were analyzed using Graph Pad Prism 8 (Graphd Pad Software, Inc. San Diego, CA, USA) and are expressed as mean ± standard error of the mean. Normality was assessed using the Shapiro-Wilk tests, and homogeneity of variance was evaluated with Levene’s tests. Depending on data distribution, group differences were analyzed using either the Mann-Whitney U test for nonparametric data or Student’s t-test for parametric data. A p-value < 0.05 was considered statistically significant (*p < 0.05, **p < 0.01, ***p < 0.001).

Results

Preventive TDF administration reduced mouse body weight gain and myeloid inflammatory cell presence in BALF after an acute BLM treatment

To evaluate the impact of preventive TDF treatment on BLM-induced lung injury, mice were treated with TDF at D0 and challenged with BLM at D7 (Fig. 1A). Weight gain and lung-to-body weight ratio were assessed at D10. BLM-induced lung damage reduced weight gain by D10, with a more pronounced effect in males. Preventive TDF administration mitigated this weight loss (Fig. 1B). However, the lung-to-body weight ratio increased similarly in both the BLM and TDF-BLM groups for both sexes, indicating no effect of TDF pretreatment on this parameter (Fig. 1C). Given that BLM causes an acute increase in total cells in BALF18 BALF samples from the four experimental groups, separated by sex, were analyzed at D10 (Fig. 2). In the BLM group, BALF protein concentration, total cell counts, neutrophil and macrophage counts and neutrophil-lymphocyte ratio were significantly higher compared to the SAL and TDF groups. With the exception of protein content, these increases were markedly attenuated in the TDF-BLM group for both sexes. Interestingly, the mild increase in lymphocyte numbers induced by BLM was further elevated in TDF-pretreated BLM-challenged mice (TDF-BLM group) in both sexes (p < 0.05 and p < 0.001 for males and females, respectively) (Fig. 2C). Notably, male mice exhibited a greater increase in total inflammatory cells and subtypes in BALF than females following BLM challenge. This increase was predominantly driven by neutrophils, with lymphocytes contributing to a lesser extent, while macrophage numbers showed no sex-based differences (Fig. 2C). These findings indicate that in BLM-injured lungs, preventive TDF treatment effectively reduced myeloid cell counts in BALF while enhancing lymphocyte presence. Although total cell counts were higher in male mice, the relative efficacy of TDF treatment was consistent across sexes.

Preventive treatment with TDF decreases presence of macrophages and neutrophils in BALF although increases lymphocyte numbers of both genders of BLM-treated mice. (A) Quantification of BALF protein at D10. n = 8 mice per group. (B) Representative images of BALF obtained from males. ly, lymphocyte; mФ, macrophage; ne, neutrophil. Scale bar: 50 μm. (C) Total and differential cell counts performed in cytospin preparations of BALF from the four experimental groups of both sexes. BALF, bronchoalveolar lavage fluid. n = 5–8 mice per group. Data are expressed as mean ± SEM. *p < 0.05; **p < 0.01; ***p < 0.001 (Mann-Whitney U- or Student´s t-tests).

Preventive treatment with TDF decreased BLM-mediated acute lung injury and recluted interstitial lymphocytes

Lung histology was evaluated on D10 using H&E-stained sections of the lungs. Lung inflammation, due to the accumulation of cells with lymphocyte morphology in foci, increased after the BLM challenge in both sexes (Fig. 3A-B), in accordance with the higher lymphocyte counts found in the BALF of these experimental groups (Fig. 2C). Likewise, lung injury score markedly increased in BLM-challenged mice. Interestingly, TDF treatment prior to BLM challenge resulted in a significant reduction in acute lung injury score in females (p < 0.05), while a similar trend was observed in males (p = 0.057) (Fig. 3C). In order to evaluate TDF-mediated pulmonary lymphocytes recruitment, immunostaining for Cd4+ was performed in lung sections of male mice. Of note, BLM increased Cd4+ cell counts in the lung, and preventive treatment with TDF, showed a tendency to further increase these numbers (p = 0.056) (Fig. 4).

TDF treatment decreases BLM-induced acute lung injury. (A and B) Representative images of H&E stained lung sections obtained from male (A) and female (B) mice of all experimental groups. Inflamed areas with leucocyte accumulation are indicated by arrows in BLM-treated lungs. al, alveoli; bv, blood vessel. Scale bar: 100 μm. (C) Lung injury score quantification in both sexes (n = 4 per group). Data are expressed as mean ± SEM. *p < 0.05 (Mann-Whitney U test).

TDF pretreatment diminished the expression of proinflammatory cytokines and altered angiotensin mRNA levels in lungs of BLM-challenged mice

To verify and further investigate the mechanism by which treatment of BLM-challenged mice with TDF regulates inflammatory cell recruitment to the lungs, the mRNA expression levels of pro-inflammatory (Tnfα, ll1β, Il10 and Il6) and profibrotic (Tgfβ) cytokines were determined using qPCR (Fig. 5A). As expected, mRNA levels of Tnfα, Il6, and Tgfβ were strongly induced after the BLM challenge in both sexes, and Il1β only in females. Pretreatment with TDF significantly reduced these increases in females treated with TDF-BLM. In males, only Il1β induction was significantly counteracted, although a downward trend was observed for the remaining cytokines. Apart from a significant increase in TDF females, no differences were observed in ll10 levels between BLM- and TDF-BLM-challenged mice. Serum IL6 protein levels, as assessed via ELISA, mimicked the mRNA levels found in the lungs of male mice, although no significant reduction was found in female mice (Fig. 5B).

Because angiotensin-converting enzyme (ACE) isoforms protect against acute lung injury in several animal models of ARDS19we determined the mRNA levels of Ace and Ace2. In the BLM group, Ace was upregulated in both male and female mice. However, Ace2 expression was significantly increased only in female mice, while male mice showed no significant change. Interestingly, preventive TDF treatment in BLM-challenged mice was associated with a decreasing trend in Ace and mRNA expression compared to the BLM group. Specifically, Ace expression was significantly reduced in females and showed a non-significant decrease in males, while Ace2 expression was lower in both sexes without reaching statistical significance (Fig. 5C).

Decreased levels of inflammatory markers and changes in expression levels of angiotensin converting enzymes in BLM-challenged male and female mice pretreated with TDF. (A) Lung tissue mRNA expression of proinflammatory (Tnfα, Il1β, Il10 and Il6) and profibrotic (Tgfβ) markers. (B) Serum protein levels of IL6 determined by ELISA. (C) Ace and Ace2 mRNA levels were determined by qPCR. n = 5–6 mice per group. Data are expressed as mean ± SEM. *p < 0.05; **p < 0.01 (Mann-Whitney U- or Student´s t-tests).

Preventive administration of TDF protected mouse bronchiolar epithelium against BLM-mediated acute lung injury

The first physical barrier encountered by BLM after oropharyngeal administration in mice is the respiratory airway epithelium, which suffers the most cellular damage and is therefore responsible for the initiation of the acute lung injury response and consequent cytokine storm13. To evaluate the preventive effect of TDF treatment on the bronchiolar epithelium of BLM-challenged mice of both sexes, bronchioles were assessed by histological and immunohistochemical analyses of lung sections at D10 (Fig. 6). H&E staining revealed damaged airway epithelium in the lungs of BLM-challenged males (Fig. 6C) compared to the normal morphology in the SAL and TDF groups (Fig. 6A-B). Interestingly, preventive TDF treatment in TDF-BLM mice normalized the bronchiolar epithelium histology, although it caused frequent alignments in short segments of club cells that lacked apical cupulated protrusions and had nuclei aligned at the same epithelium level (Fig. 6D).

Protective effect of TDF on bronchiolar epithelium of male mice against the BLM-mediated acute lung injury. (A-D) Representative images of H&E stained lung sections through terminal bronchioles of SAL (A), TDF (B), BLM (C) and TDF-BLM (D) groups. Images show that the damaged bronchiolar epithelium containing altered cell shapes and detached cell debris (blue arrowheads) in BLM-challenged mice (C), is standardized in TDF-BLM animals (D), mimicking SAL and TDF-groups (A, B), albeit with special features. Thus, it frequently presents alignments of club cells that lack their cupulated apical protrusions and with their nuclei also aligned at the same height (blue arrows) (D). (E-P) Representative immunostaining of CC10+ (club cells) in red (E-H) and pro-SPC+ in green (I-L), and merged staining of CC10, Pro-SPC and DAPI (nuclei in blue) (M-P) in bronchiole sections of the four groups. Club cells in bronchioles of TDF animals usually show an intense and homogeneous staining for CC10 throughout the cells (red arrow) (F, N), whereas in SAL animals the staining is more restricted to the apical dome (E, M). Presence of pro-SPC+ cells was abundant in bronchiolar epithelium of BLM mice which does not colocalize with that of CC10+ cells (green arrows) (K, O) in comparison with their paucity found in SAL (I, M), TDF (J, N) and TDF-BLM (L, P) mice. Density of pro-SPC+ stained alveolar epithelial type II cells (green arrowheads) was reduced in both BLM and TFD-BLM alveolar areas (K, O and L, P) in comparison with non-BLM challenged mice (SAL and TDF) (I, M and J, N). al: alveolar zone. tb: terminal bronchiole. Scale bars in D and P: 50 μm. (Q-R) Quantification of relative fluorescent surface of CC10+ and Pro-SPC+ in bronchiolar epithelium, respect to total bronchiolar epithelium area (n = 6 male mice per group). Data are represented as mean ± SEM. ***p < 0.001 (Mann-Whitney U- or Student´s t-tests).

The protective effect of TDF on pulmonary epithelial cells was further corroborated by immunohistochemistry (Fig. 6E-P). Thus, the club cell marker CC10/Scgb1a1 was expressed throughout the bronchiolar airway epithelium in both the SAL and TDF groups (Fig. 6E-F, M-N). However, in control SAL mice, CC10 staining was restricted to the apical dome of club cells, excluding the basal part where the nuclei were located (Fig. 6E, M), whereas in the TDF group, these cells showed more widespread and homogeneous staining surrounding the nuclei in the basal position (Fig. 6F, N). In BLM mice, club cells also showed widespread intracellular expression of CC10 but presented an irregular arrangement with frequent disruption along the epithelium (Fig. 6G, O). Interestingly, male TDF-BLM mice showed a smaller CC10+ bronchiolar area that was highly restricted to the apical side of the club cells (Fig. 6H, P). Quantification of the CC10+ area in the bronchiolar epithelium of males proved these results, resulting in a significant increase in TDF (30%) and BLM (23%), compared to SAL (p < 0.001). Preventive TDF treatment in the TDF-BLM group of males reduced the CC10+ epithelial surface by almost half compared to that in BLM animals (p < 0.001) (Fig. 6Q).

When immunohistochemistry was performed to identify the surfactant protein C precursor (pro-SPC) in males, the staining in alveolar type II cells was found to be reduced in both groups of BLM-challenged animals (BLM and TDF-BLM) with respect to SAL and TDF (Fig. 6I-P), indicating that although BLM reduced the presence of this type of alveolar cells, TDF treatment had no effect on them. However, the results differed for the bronchioles. In contrast to the sporadic presence of pro-SPC+ cells in the bronchiolar epithelium of male SAL and TDF mice (Fig. 6I, M and J, N), their scattered distribution, not coincident with CC10+ club cells, was highly abundant in BLM animals (Fig. 6K, O). This result was expected because transient pro-SPC expression was recently reported in bronchiolar cells after BLM challenge20. Notably, presence of pro-SPC+ was also scarce in the TDF-BLM group (Fig. 6L, P), indicating a protective function of TDF treatment. Quantitative determination of the relative extension of pro-SPC+ bronchiolar areas in all groups of males demonstrated a significant increase in the BLM mice (0.75% of the total area) compared to the other three experimental groups (approximately 0.1%) (p < 0.001) (Fig. 6R). Similar results, although not as significant, were obtained in females (data not shown). On the other hand, combing both genders, the administration of TDF significantly reduced lung injury scores. After analyzing by gender, this reduction was significantly observed in females, while in males there was a clear trend towards significance (Fig. 3C). Taken together, these results demonstrate that preventive treatment with TDF effectively protects against bronchiolar epithelial cell damage and BLM-mediated acute lung injury in mice.

Discusssion

This study explores the protective effects of TDF against BLM-induced lung injury in mice. Our findings reveal that TDF significantly reduces lung inflammation, as indicated by decreased total cell counts in BALF, particularly in macrophages and neutrophils, despite an increase in lymphocytes. Additionally, TDF reduced the BLM-induced upregulation of inflammatory mediators at the mRNA level and improved lung architecture, as evidenced by less bronchiolar and alveolar damage and better ALI scores. Notably, male mice exhibited greater susceptibility to BLM-induced lung injury, including increased body weight loss. However, TDF provided comparable protection in both sexes.

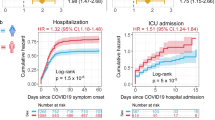

Our findings in mice align with a human study conducted in Spain by del Amo et al.21which investigated the incidence and severity of COVID-19 among PLWH in relation to the use of NRTIs. The authors observed that PLWH receiving TDF/emtricitabine (FTC) had the lowest risk of COVID-19 diagnosis and hospitalization compared to those receiving other NRTI. The authors proposed that TDF/FTC might prevent severe COVID-19 outcomes in PLWH21. In a subsequent study, del Amo et al.22 reported that estimated risk for hospitalization or intensive care unit admission were significantly lower with TDF/FTC. These findings have been corroborated by studies conducted in Spain23 South Africa24 and the United States25. However, these findings contrast with other clinical reports, such as the study by Nomah et al.26 which found no significant association between TAF/FTC or TDF/FTC use and reduced SARS-CoV-2 diagnosis or hospitalization rates in PLWH. Additionally, our results align less consistently with another Spanish study that assessed the seroprevalence and clinical manifestations of COVID-19 in individuals using TDF/FTC or TAF/FTC for HIV PrEP. This study reported a higher seroprevalence of SARS-CoV-2 in the PrEP group compared to controls, although no statistically significant differences were observed in COVID-19 clinical manifestations between the groups27. The inconsistencies across clinical studies regarding the preventive role of TDF prompted us to investigate its efficacy against BLM-induced lung injury in a mouse model.

One potential explanation for beneficial effects of TDF lie in its immunomodulatory effects by regulating inflammatory cytokine secretion in human primary cells28,29. Specifically, it reduces the secretion of CCL3 and Il8 in monocytes and CCL3 in blood mononuclear cells, while shifting the Il10/Il12 balance30. Our in vivo study further supports these findings, showing that TDF treatment for seven days prior to BLM administration reduced myeloid inflammation while increasing lymphocyte counts. Moreover, TDF exhibited antifibrotic properties by significantly lowering lung levels of Tgfβ1, a potent profibrogenic cytokine, reinforcing its protective effects. A previous study by Li et al31. evaluated the antifibrotic effects of TAF in a BLM-induced pulmonary fibrosis mouse model. Unlike our preventive approach, their study used only male mice and administered TAF intragastrically (5.125 mg/kg) once daily for 3 weeks, starting at different days (D0, D7, and D14) after intratracheal BLM instillation. They observed higher mortality rates in the BLM groups compared to the TAF-treated groups (40–50% vs. 0–20%, respectively), with significantly improved survival in mice treated on D0 compared to those treated on D7 or D14 31. Consistent with our findings, TAF-treated mice showed significantly reduced expression of Tgfβ1, along with decreased levels of collagen-3α1, α-SMA, and fibronectin compared to the BLM-only group. Further analysis showed that TAF modulates the Tgfβ1/Smad3 signaling pathway31. Notably, the antifibrotic potential of TDF extends beyond lung disease. Previous studies have demonstrated its efficacy in preventing liver fibrosis by inducing hepatic stellate cell apoptosis through downregulation of the PI3K/Akt/mTOR signaling pathway32. These findings collectively highlight the broad effects of TDF and its therapeutic potential in various fibrotic diseases.

At the molecular level, some studies suggested that NRTIs inhibit SARS-CoV-2 polymerase33,34. Notably, tenofovir diphosphate (TFV-DP), the active triphosphate form of both TAF or TDF, achieves higher serum concentrations when derived from TDF, although intracellular levels are lower35. Consistently, a ferret model of SARS-CoV-2 infection showed that the TDF/FTC-treated group had reduced viral titers and shorter duration of viral shedding in nasal wash compared to the untreated infected group36.

Studies have shown that ACE2 plays a critical role in lung health37. However, reduced ACE2 levels compromise this lung-protective function, potentially leading to alveolar epithelial cell death and exacerbating lung inflammation38. Interestingly, our study found that the preventive TDF model for BLM-induced lung disease was associated with a tendency toward reduced ACE and ACE2 levels. This observation is particularly relevant in the context of SARS-CoV-2, which employs its spike protein to bind to the human ACE2 receptor for cellular entry. Supporting this connection, Yun et al.39 investigated the potential of existing antiviral compounds to block this interaction. Their study showed that TDF exhibit a strong capacity to disrupt the binding of the SARS-CoV-2 spike protein to the ACE2 receptor, highlighting a potential mechanism for its protective effect.

BLM-induced damage to the bronchiolar airway allows access to the lung interstitium, triggering further pulmonary injury7. In this study, we observed that the bronchiolar epithelium in TDF-BLM-treated mice was protected from cell loss and damage to CC10+ club cells but did not provide similar protection to alveolar type II cells. While pro-SPC expression is uncommon in normal bronchiolar epithelium, its presence has been reported to increase following BLM injury, correlating with the presence of bronchioalveolar progenitor cells, which are critical for lung repair post-injury20,40. Interestingly, the absence of SPC+ epithelial precursors in the bronchiolar epithelium of TDF-BLM-treated lungs suggests that these cells did not undergo regeneration, likely due to the epithelium being protected from BLM-induced damage. However, the precise mechanisms underlying this protection remain to be elucidated.

Survival analyses of COVID-19 have shown that men have a significantly higher risk of severe outcomes and mortality41. In this regard, Scully et al.42 pointed out various factors linked to biological sex and immune responses that may influence COVID-19 outcomes. In our study, we mostly observed that BLM-induced lung damage and inflammatory responses were more pronounced in male mice. However, the preventive effect of TDF in mitigating lung damage were comparable between sexes, effectively counteracting BLM-induced injury in both. Consistent with our findings, previous studies have reported that male mice showed significantly greater lung injury, inflammation, proinflammatory cytokines levels, and fibrosis in response to BLM exposure compared to females. This has been attributed to sex-specific gene expression in myeloid cells43. The greater increase in myeloid cells (macrophages and neutrophils) observation in the BALF of BLM-treated male mice compared to females may explain their heightened inflammatory response and increased ALI. Conversely, contrasting findings have been reported by Gharaee-Kermani et al.44 who observed higher mortality and more severe fibrosis in female rats following BLM exposure, attributing these effects to female sex hormones. These discrepancies may stem from differences in sex-based responses between ALI and fibrosis or species-specific variations in response to BLM.

This study has several limitations that should be considered. First, although BLM-induced lung injury in mice mimics key features of acute inflammation and alveolar damage, it cannot fully reproduce the complexity of COVID-19 pathophysiology in humans. In addition, murine immune and pulmonary responses differ substantially from those of humans, which may restrict the direct translational relevance of these findings. Our experimental design also relied on a single dose and route of administration for both BLM and TDF, which may not reflect the full spectrum of clinical exposure. Finally, the use of relatively young and healthy animals under controlled conditions may overlook the heterogeneity of human patients with diverse comorbidities. Future research in alternative models and clinical settings will help address these limitations and further clarify the potential benefits of TDF as a preventive strategy.

In summary, our findings provide new insight into the role of TDF during cytokine storm and support the epidemiological hypothesis of its beneficial effects in acute inflammatory states of lung damage, such as those observed in SARS-CoV-2 infection.

Data availability

In accordance with the journal’s guidelines, the datasets used in this research are available upon request from the corresponding author.

References

Turtle, L. et al. Outcome of COVID-19 in hospitalised immunocompromised patients: an analysis of the WHO ISARIC CCP-UK prospective cohort study. PLoS Med. 20, e1004086. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pmed.1004086 (2023).

Dong, Y. et al. HIV infection and risk of COVID-19 mortality: A meta-analysis. Med. (Baltim). 100, e26573. https://doi.org/10.1097/MD.0000000000026573 (2021).

Chen, X. P. & Cao, Y. Consideration of highly active antiretroviral therapy in the prevention and treatment of severe acute respiratory syndrome. Clin. Infect. Dis. 38, 1030–1032. https://doi.org/10.1086/386340 (2004).

European AIDS Clinical Society (EACS). Guidelines version 11.1, October 2022. Available at: https://www.eacsociety.org/media/guidelines-11.1_final_09-10.pdf

Solomon, M. M. et al. The safety of Tenofovir-Emtricitabine for HIV Pre-Exposure prophylaxis (PrEP) in individuals with active hepatitis B. J. Acquir. Immune Defic. Syndr. 71, 281–286. https://doi.org/10.1097/QAI.0000000000000857 (2016).

Hu, B., Huang, S. & Yin, L. The cytokine storm and COVID-19. J. Med. Virol. 93, 250–256. https://doi.org/10.1002/jmv.26232 (2021).

Matute-Bello, G., Frevert, C. W. & Martin, T. R. Animal models of acute lung injury. Am. J. Physiol. Lung Cell. Mol. Physiol. 295, L379–399. https://doi.org/10.1152/ajplung.00010.2008 (2008).

Bordag, N. et al. Machine learning analysis of the bleomycin mouse model reveals the compartmental and Temporal inflammatory pulmonary fingerprint. iScience 23, 101819. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.isci.2020.101819 (2020).

Aran, D. et al. Reference-based analysis of lung single-cell sequencing reveals a transitional profibrotic macrophage. Nat. Immunol. 20, 163–172. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41590-018-0276-y (2019).

Liao, M. et al. Single-cell landscape of Bronchoalveolar immune cells in patients with COVID-19. Nat. Med. 26, 842–844. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41591-020-0901-9 (2020).

Wen, W. et al. Immune cell profiling of COVID-19 patients in the recovery stage by single-cell sequencing. Cell. Discov. 6, 31. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41421-020-0168-9 (2020).

Borczuk, A. C. et al. COVID-19 pulmonary pathology: a multi-institutional autopsy cohort from Italy and new York City. Mod. Pathol. 33, 2156–2168. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41379-020-00661-1 (2020).

Moeller, A., Ask, K., Warburton, D., Gauldie, J. & Kolb, M. The bleomycin animal model: a useful tool to investigate treatment options for idiopathic pulmonary fibrosis? Int. J. Biochem. Cell. Biol. 40, 362–382. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.biocel.2007.08.011 (2008).

Zhang, T. Y. et al. A unique B cell epitope-based particulate vaccine shows effective suppression of hepatitis B surface antigen in mice. Gut 69, 343–354. https://doi.org/10.1136/gutjnl-2018-317725 (2020).

Chawki, S. et al. Ex-vivo rectal tissue infection with HIV-1 to assess time to protection following oral preexposure prophylaxis with Tenofovir disoproxil/emtricitabine. AIDS 38, 455–464. https://doi.org/10.1097/QAD.0000000000003789 (2024).

Egger, C. et al. Administration of bleomycin via the oropharyngeal aspiration route leads to sustained lung fibrosis in mice and rats as quantified by UTE-MRI and histology. PLoS One. 8, e63432. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0063432 (2013).

Matute-Bello, G. et al. An official American thoracic society workshop report: features and measurements of experimental acute lung injury in animals. Am. J. Respir Cell. Mol. Biol. 44, 725–738. https://doi.org/10.1165/rcmb.2009-0210ST (2011).

Pineiro-Hermida, S. et al. IGF1R deficiency attenuates acute inflammatory response in a bleomycin-induced lung injury mouse model. Sci. Rep. 7, 4290. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-017-04561-4 (2017).

Kuba, K., Imai, Y. & Penninger, J. M. Angiotensin-converting enzyme 2 in lung diseases. Curr. Opin. Pharmacol. 6, 271–276. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.coph.2006.03.001 (2006).

Nabhan, A. N. et al. Targeted alveolar regeneration with Frizzled-specific agonists. Cell 186, 2995–3012 e2915, (2023). https://doi.org/10.1016/j.cell.2023.05.022

Del Amo, J. et al. Incidence and severity of COVID-19 in HIV-Positive persons receiving antiretroviral therapy: A cohort study. Ann. Intern. Med. 173, 536–541. https://doi.org/10.7326/M20-3689 (2020).

Del Amo, J. et al. Tenofovir disoproxil fumarate/emtricitabine and severity of coronavirus disease 2019 in people with HIV infection. AIDS 36, 2171–2179. https://doi.org/10.1097/QAD.0000000000003372 (2022).

Berenguer, J. et al. Prevalence and factors associated with SARS-CoV-2 seropositivity in the Spanish HIV research network cohort. Clin. Microbiol. Infect. 27, 1678–1684. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.cmi.2021.06.023 (2021).

Western Cape Department of Health in collaboration with the National Institute for Communicable & Diseases, S. A. Risk Factors for Coronavirus Disease 2019 (COVID-19) Death in a Population Cohort Study from the Western Cape Province, South Africa. Clin Infect Dis 73, e2005-e (2015). https://doi.org/10.1093/cid/ciaa1198 (2021).

Li, G. et al. Tenofovir disoproxil fumarate and coronavirus disease 2019 outcomes in men with HIV. AIDS 36, 1689–1696. https://doi.org/10.1097/QAD.0000000000003314 (2022).

Nomah, D. K. et al. Impact of Tenofovir on SARS-CoV-2 infection and severe outcomes among people living with HIV: a propensity score-matched study. J. Antimicrob. Chemother. 77, 2265–2273. https://doi.org/10.1093/jac/dkac177 (2022).

Ayerdi, O. et al. Preventive efficacy of tenofovir/emtricitabine against severe acute respiratory syndrome coronavirus 2 among Pre-Exposure prophylaxis users. Open. Forum Infect. Dis. 7, ofaa455. https://doi.org/10.1093/ofid/ofaa455 (2020).

Zidek, Z., Frankova, D. & Holy, A. Activation by 9-(R)-[2-(phosphonomethoxy)propyl]adenine of chemokine (RANTES, macrophage inflammatory protein 1alpha) and cytokine (tumor necrosis factor alpha, interleukin-10 [IL-10], IL-1beta) production. Antimicrob. Agents Chemother. 45, 3381–3386. https://doi.org/10.1128/AAC.45.12.3381-3386.2001 (2001).

Zidek, Z., Potmesil, P., Kmoniekova, E. & Holy, A. Immunobiological activity of N-[2-(phosphonomethoxy)alkyl] derivatives of N6-substituted adenines, and 2,6-diaminopurines. Eur. J. Pharmacol. 475, 149–159. https://doi.org/10.1016/s0014-2999(03)02110-1 (2003).

Melchjorsen, J. et al. Tenofovir selectively regulates production of inflammatory cytokines and shifts the IL-12/IL-10 balance in human primary cells. J. Acquir. Immune Defic. Syndr. 57, 265–275. https://doi.org/10.1097/QAI.0b013e3182185276 (2011).

Li, L. et al. Tenofovir Alafenamide fumarate attenuates bleomycin-induced pulmonary fibrosis by upregulating the NS5ATP9 and TGF-beta1/Smad3 signaling pathway. Respir Res. 20, 163. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12931-019-1102-2 (2019).

Lee, S. W. et al. Tenofovir disoproxil fumarate directly ameliorates liver fibrosis by inducing hepatic stellate cell apoptosis via downregulation of PI3K/Akt/mTOR signaling pathway. PLoS One. 16, e0261067. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0261067 (2021).

Chien, M. et al. Nucleotide analogues as inhibitors of SARS-CoV-2 polymerase, a key drug target for COVID-19. J. Proteome Res. 19, 4690–4697. https://doi.org/10.1021/acs.jproteome.0c00392 (2020).

Ju, J. et al. Nucleotide analogues as inhibitors of SARS-CoV polymerase. Pharmacol. Res. Perspect. 8, e00674. https://doi.org/10.1002/prp2.674 (2020).

Podany, A. T. et al. Plasma and intracellular pharmacokinetics of Tenofovir in patients switched from Tenofovir disoproxil fumarate to Tenofovir Alafenamide. AIDS 32, 761–765. https://doi.org/10.1097/QAD.0000000000001744 (2018).

Park, S. J. et al. Antiviral Efficacies of FDA-Approved Drugs against SARS-CoV-2 Infection in Ferrets. mBio 11, e01114–20. https://doi.org/10.1128/mBio.01114-20 (2020)

Ziegler, C. G. K. et al. SARS-CoV-2 receptor ACE2 is an Interferon-Stimulated gene in human airway epithelial cells and is detected in specific cell subsets across tissues. Cell 181 (e1019), 1016–1035. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.cell.2020.04.035 (2020).

Imai, Y. et al. Angiotensin-converting enzyme 2 protects from severe acute lung failure. Nature 436, 112–116. https://doi.org/10.1038/nature03712 (2005).

Yun, Y. et al. Identification of therapeutic drugs against COVID-19 through computational investigation on drug repurposing and structural modification. J. Biomed. Res. 34, 458–469. https://doi.org/10.7555/JBR.34.20200044 (2020).

Volckaert, T. & De Langhe, S. Lung epithelial stem cells and their niches: Fgf10 takes center stage. Fibrogenesis Tissue Repair. 7, 8. https://doi.org/10.1186/1755-1536-7-8 (2014).

Jin, J. M. et al. Gender differences in patients with COVID-19: focus on severity and mortality. Front. Public. Health. 8, 152. https://doi.org/10.3389/fpubh.2020.00152 (2020).

Scully, E. P., Haverfield, J., Ursin, R. L., Tannenbaum, C. & Klein, S. L. Considering how biological sex impacts immune responses and COVID-19 outcomes. Nat. Rev. Immunol. 20, 442–447. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41577-020-0348-8 (2020).

Lamichhane, R., Patial, S. & Saini, Y. Higher susceptibility of males to bleomycin-induced pulmonary inflammation is associated with sex-specific transcriptomic differences in myeloid cells. Toxicol. Appl. Pharmacol. 454, 116228. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.taap.2022.116228 (2022).

Gharaee-Kermani, M., Hatano, K., Nozaki, Y. & Phan, S. H. Gender-based differences in bleomycin-induced pulmonary fibrosis. Am. J. Pathol. 166, 1593–1606. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0002-9440(10)62470-4 (2005).

Acknowledgements

This work was supported partly by grant PID2021-127860OB-I00 funded by MCIN/AEI/10.13039/501100011033 (Spain) and by “ERDF A way of making Europe” (EU). The authors express their deep gratitude to Dr. Susana Rubio-Mediavilla for her invaluable review of the histologies.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

JRB, JGP, IPL, and LPM proposed and conceived the project and designed the experiments. EAA, IPL, LPM, LR, and MC performed the experiments. JRB, JGP, IPL, and LPM analyzed the data and interpreted the experiments. JRB, JGP, IPL, and LPM drafted and wrote the manuscript. All authors read, revised and approved the manuscript prior to submission.

Corresponding authors

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

Dr L Pérez-Martínez has received compensation for lectures from Abbvie, Bristol-Myers Squibb, Gilead Sciences, and Janssen. Dr. JR Blanco has carried out consulting work for Abbvie, Bristol-Myers Squibb, Gilead Sciences, Janssen, Merck, Moderna, Pfizer and ViiV Healthcare; has received compensation for lectures from Abbvie, Bristol-Myers Squibb, Gilead Sciences, Janssen, Merck, Pfizer and ViiV Healthcare, as well as grants and payments for the development of educational presentations for Gilead Sciences, Bristol-Myers Squibb and ViiV Healthcare. The rest of the authors declare no conflicts of interest.

Additional information

Publisher’s note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if you modified the licensed material. You do not have permission under this licence to share adapted material derived from this article or parts of it. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

López, I.P., Romero, L., Alfaro-Arnedo, E. et al. Tenofovir attenuates cytokine storm and bronchiolar damage in a mouse model of bleomycin-induced acute lung injury. Sci Rep 15, 31570 (2025). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-16560-x

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-16560-x