Abstract

Robot-assisted mirror therapy (MRT) is a cutting-edge rehabilitative treatment that combines mirror therapy and rehabilitation robots and can improve stroke patient participation in rehabilitation training. The aim of this study was to investigate the effects of MRT training in patients with right-hemisphere damage (RHD). Fifty-three RHD patients were randomly assigned to the MRT (N = 17), passive movement (PM) (N = 19), or functional occupational therapy (FOT) group (N = 17) for 4 weeks of training. All three groups received conventional medication and rehabilitation therapy, along with 20 min of FOT. In addition, the MRT group underwent 10 min of MRT, the PM group received 10 min of PM training, and the FOT group underwent 10 min of additional FOT. Upper-limb motor function was evaluated by the Fugl–Meyer Assessment–Upper Extremity (FMA-UE) and the Fugl–Meyer Assessment–Wrist and Hand (FMA-WH) before and after treatment. The daily life activities of the patients were evaluated with the modified Barthel index (MBI). Cortical activation was evaluated by functional near-infrared spectroscopy (fNIRS). Compared with the PM and FOT methods, the MRT method more effectively improved the FMA-UE score, FMA-WH score and MBI. In addition, MRT is expected to improve cortical activation in patients.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

According to the World Health Organization, 15 million people worldwide suffer from stroke annually, approximately 80% of whom experience motor dysfunction of the upper limbs, which particularly impacts the coordination and flexibility of the hands1,2,3. A study revealed that, 3 months after stroke, only 12% of survivors reported having no changes in hand function, whereas 38% reported having severe hand dysfunction4. The distal joints of the fingers require precise and complex control to achieve movement, and compared with the proximal joints, their recovery takes longer and is more difficult, and they have a lower possibility of regaining complete function5. Hand function is particularly relevant to activities of daily life. Loss of hand function in stroke patients results in a 27% decrease in function, severely affecting independence and activities of daily life; this adverse effect lasts for 3–6 months or more, and fewer than 50% of patients recover hand function in the upper extremities 6 months after stroke6,7,8.

Many studies have shown that repeated motor exercises and active participation in activities in real environments are beneficial for recovering motor function after stroke9. Rehabilitation robots can help patients move their limbs more efficiently to simulate repetitive and high-intensity movements guided by therapists, showing great benefits in the treatment process10. Rehabilitation robots are now widely used in neurological rehabilitation, providing automated and standardized rehabilitation training modes and high-dose, high-intensity and long-term training, simplifying the work of rehabilitation therapists, and improving the efficiency of rehabilitation training1,11,12. Hand rehabilitation robots can provide a full range of joint motion and prevent incorrect movement patterns from occurring while providing patients with different types of training as needed13.

Although rehabilitation robots have many advantages, their role in providing purely passive training prevents patients from actively participating in the exercises, which can easily result in fatigue and reduce patient interest in the training while yielding suboptimal rehabilitation results. Mirror therapy (MT) was initially used for the treatment of phantom limb pain in patients and is based on the principle of plane mirror imaging to provide visual feedback through mirrors, where visual information about the activity of the healthy limb is reflected through the mirror, creating the visual illusion that the affected limb is also active14,15. Altschuler et al.[14]. proposed the use of MT for the rehabilitation of hemiplegia after stroke, reported that it could improve the motor performance of patients with chronic stroke, and gradually began to use MT in the rehabilitation of motor dysfunction after stroke. Continuous mirror visual feedback can stimulate the mirror neuron system (MNS) of the brain, which is located mainly in vision-related areas of the occipital, temporal, and parietal lobes and motor areas of the frontal‒parietal lobes on both sides, connecting the sensory neurons for visual processing and the motor neurons for motor signaling[16]. It affects the electrical activity and excitability of the cortex to promote functional remodeling of the brain, which restores motor function17. Yu Wei et al.18 reported that although each intervention session was brief, four weeks of mirror therapy led to significant improvements in motor function and cortical reorganization.

To solve the problem of low patient participation under passive training regimens, mirror image rehabilitation training robots have been introduced. These devices combine the theory of MT with the design of rehabilitation robots and have emerged as leading-edge technologies in the field of rehabilitation while also engaging the brain center to improve patient motivation to train. It recognizes the movement track of the unaffected hand, perceives the patient’s active movement intention in real time, generates the movement track of the affected side, and drives the patient to complete similar training actions19. In this training mode, the degree of interaction between the patient and the robot can be improved, the subjective initiative of the patient can be increased, and personalized training movements can be provided according to the patient’s situation. The training scope is determined by the patients so that they can more actively participate in the treatment process.

Although some progress has been made in the study of MT robots, several limitations remain. One is the lack of targeted clinical trials, as only a limited number of studies have demonstrated the beneficial effects of robot-assisted mirror therapy (MRT) on stroke patients. Dong Wei et al.[20] designed a study aimed at comparing the clinical efficacy of virtual reality MT and robot-assisted virtual reality MT for stroke patients, but the results of only one protocol were published, and the comparative results are currently unpublished. Mareike Schrader et al.[21]compared the effects of standard MT with those of robot-assisted therapy and revealed that robot-assisted training had better outcomes in terms of motor function. MRT is increasingly being used for patients with neurological disorders and is expected to improve the effectiveness of training for stroke patients; however, only a few studies have explored this possibility specifically, and further trials are needed to demonstrate the effectiveness of this treatment[22].

On the basis of the above research background, the aim of this study was to design a randomized controlled trial to investigate the effects of MRT on brain remodeling in patients with right-hemisphere damage (RHD) via functional near-infrared spectroscopy (fNIRS). We hypothesized that, compared with other methods, MRT would be more effective at improving upper-limb function and brain remodeling in RHD patients.

Methods

Participants

The participants were patients with RHD who were hospitalized at the China Rehabilitation Research Center from November 2024 to February 2025. The inclusion criteria were as follows: (1) first incident of RHD confirmed by CT or MRI to reduce interindividual variability associated with lesions in different hemispheres; (2) aged between 18 and 75 years; (3) alert, capable of understanding therapist instructions, and had Mini-Mental State Examination (MMSE) scores above 24, suggesting relatively intact cognitive function; (4) had left upper-limb motor dysfunction (Brunnstrom stage ≤ II); (5) were right-handed; and (6) signed the informed consent form. The exclusion criteria were as follows: (1) major organ dysfunction; (2) upper-limb dysfunction for other reasons that influenced rehabilitation training; and (3) depression or anxiety and inability to cooperate with the treatment. The removal criteria were as follows: patients with low levels of cooperativity and who attended less than 20% or more of the total number of training sessions for various reasons, thus affecting the outcome ratings, were removed from the study.

Sample size estimation

The sample size was estimated prospectively via PASS software version 22.0.2 (NCSS, LLC. Kaysville, Utah, USA, Available from: https://www.ncss.com/download/pass/). On the basis of a previous randomized controlled study[22] we referred to the literature for the group means and standard deviations of the three groups. We set an alpha level of 0.05 and a power of 0.8, which yielded a minimum sample size of 42 participants (14 per group). Accounting for a potential dropout rate of 30%, we planned to recruit an additional 15 participants. Thus, the planned sample size was 57 participants (19 per group).

To ensure sufficient statistical power for detecting cortical activation effects via fNIRS in this study, we conducted a power analysis. Using G*Power software version 3.1.9.7(Heinrich-Heine-Universität Düsseldorf, Düsseldorf, Germany, Available from: https://www.psychologie.hhu.de/arbeitsgruppen/allgemeine-psychologie-und-arbeitspsychologie/gpower), power calculations were performed with an effect size of Cohen’s d = 0.45 derived from preliminary experimental fNIRS centroid value calculations. The significance level (α) was set at 0.05, and the statistical power (1-β) was defined as 0.8, corresponding to an 80% probability of detecting true effects. The analysis demonstrated that a sample size of N = 51 provided adequate statistical power under the assumed effect size and significance level, ensuring the statistical validity of the research findings and minimizing the risk of false-negative outcomes.

Study design

In the present study, we used a randomized controlled, assessor-blinded design. The participants who met the criteria were randomly assigned to the MRT, passive movement (PM), or functional occupational therapy (FOT) group. Random allocation was performed using a random number table generated by a computer program (https://www.randomizer.org/). To ensure allocation concealment, the randomization process was independently executed by researchers not involved in interventions or assessments, with allocation information kept concealed from all personnel until group assignment. To minimize bias, a single-blind design was implemented, ensuring assessor blinding. Clinical evaluations were conducted by a certified occupational therapist before intervention and at four weeks postintervention. Throughout the study, the therapist remained blinded to the group assignments to prevent assessment bias.

The Ethical Review Committee of the China Rehabilitation Research Center approved the study (Ethical Approval No. 2021-076-1).The experimental procedure was explained in detail to the subjects before the start of intervention, and informed consent was obtained from all the subjects and/or their legal guardian(s) in accordance with the Declaration of Helsinki. The study was registered in the Chinese Clinical Trial Registry on 18/11/2024, with the registration number ChiCTR2400092509.

Interventions

All enrolled patients received conventional medication and rehabilitation therapy, including neurodevelopmental treatment, lower extremity physical therapy, bed-standing training, and walking training. All three groups received 20 min of FOT. On this basis, the MRT group received MRT performed by the rehabilitation robot, the PM group received PM training, and the FOT group received FOT therapy, all of which lasted 10 min, 5 times per week for a total of 4 weeks of treatment.

FOT

FOT is a type of rehabilitation training method that aims to improve function and includes manual training and repetitive functional training to establish a normal movement pattern. Manual training is used by therapists to restore the range of motion of joints, enhance muscle strength and improve motor function. The quality of manual training was determined by the therapists’ professional expertise and clinical experience. Therapists who delivered interventions possessed certified occupational therapy qualifications and received regular skill-based training throughout the study period. Functional training through the unaffected hand, such as via dowel rods, abrasive boards, rollers and other training tool, is repeated to drive the activities of the affected hand, simulate the daily activity pattern, improve the coordination and control of the upper limbs and trunk as a whole, and establish a normal movement pattern. Each training session began with familiarization training led by a therapist, after which 2–3 training movements were selected and repeated according to the patient’s condition.

To minimize bias during interventions, a single therapist delivered all treatment sessions under strictly standardized operating procedures. Regular therapist supervision was conducted to ensure treatment fidelity and session-to-session consistency. Technical execution and treatment content were standardized across all sessions to reduce interindividual variability in outcome measures.

MRT

A hand movement rehabilitation robot (SRT Pavlov H1000, Beijing Softbody Robotics Technology Co., Ltd., China) with a training glove on the affected hand and a motion recognition glove on the unaffected hand was used. The mirror therapy mode was selected, the training time was 10 min, and after starting the program, the subjects used the unaffected hand to perform the experimentally preset movements, including finger grasping and stretching. Motion recognition gloves are equipped with sensors that can recognize the action performed by detecting light signals. This means that when the sensor is unable to detect the light signal, it is recognized as grasping, and when the sensor detects the light signal, it is recognized as stretching. When the motion recognition glove successfully detects and classifies optical signals, it drives the affected hand to perform synchronized movements, and the range of motion performed by the device-assisted affected hand is consistent with that of the unaffected hand (Fig. 1a). The patient was monitored closely before and during the training session. The appropriate level of force was selected according to the participant’s tolerance level.

PM training

The same equipment (SRT Pavlov H1000, Beijing Softbody Robotics Technology Co., Ltd., China) was used for passive training of finger flexion and extension of the affected hand. The subject wore the training glove on the affected hand, selected the passive mode, and chose the appropriate strength on a scale of 1–10 according to their tolerance level. Typically, the strength is set to 5, after which it is adjusted according to the patient’s muscle tone and feelings during passive movement. The patient was kept in a relaxed state during the process, and the glove assisted the affected hand in performing passive training for 10 min (Fig. 1b).

Measurements

Patient information, including age, sex (male/female), and type of stroke (ischemic/hemorrhagic), was collected before enrollment. All the subjects were assessed pretreatment and posttreatment with the Fugl–Meyer Assessment–Upper Extremity (FMA–UE) and FMA–Wrist and Hand (FMA–WH) and the modified Barthel index (MBI).

FMA

The FMA–UE is a widely used quantitative assessment for upper extremity motor function. It has high reliability and validity for the assessment of motor impairment, with an intragroup correlation coefficient of 0.97 for the upper extremity subcomponent[23]. The FMA–UE consists of 33 items scored 0–2 points each, with a total score ranging from 0 to 66 points.

The FMA–WH assesses wrist ability, hand function, and coordination. The total score is 30, with higher scores representing better patient function[24].

MBI

The MBI is a five-level, internal consistency-validated scale used to assess the ability of stroke patients to perform activities of daily life[25]. This includes assessments of bathing, grooming, feeding, dressing, defecation, bladder control, toileting, stair climbing, chair/bed transfers, and walking. The scores range from 0 to 100, with lower scores representing a substantial lack of independence in performing activities of daily living.

fNIRS

Collection

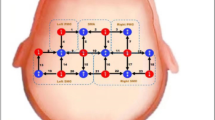

In the present study, we used an fNIRS device (LIGHTNIRS, Shimadzu Corporation, Japan) to collect cerebral blood flow data. The device operates at emission and absorption wavelengths of 780 nm, 805 nm and 830 nm, with a sampling rate of 13 Hz[18]. The device analyzes changes in oxygenated hemoglobin (Oxy-Hb) and deoxygenated Hb (Deoxy-Hb) concentrations as well as total hemoglobin (total-Hb) through the correlation of light attenuation with different concentrations of light-absorbing substances in the tissues, thus reflecting altered brain function26,27,28. The probes of the fNIRS device are arranged with reference to the international 10–20 system over the bilateral primary motor cortex (M1). The optodes were positioned with C3 and C4 as the central reference points and aligned parallel to the T3-Cz-T4 axis. A 2 × 4 grid arrangement was adopted to cover the bilateral primary motor cortices, resulting in 20 measurement channels (Fig. 2). Emitters and detectors were interleaved with a 3 cm spacing between adjacent source‒detector pairs. The detailed optode coordinates and channel configurations are provided in Fig. 2.

Before collection, the subject was fitted with a fiber optic cap, and the positions of the emitter probes and detector probes were adjusted. The hair was carefully ruffled to ensure that the probes were in close contact with the subject’s skin to obtain better signal quality. Before each collection, a signal gain check was performed to ensure the quality of data collection and that all channels showed good signals.

Task process

For the fNIRS test, we adopted a block design. The rest-task-rest paradigm was adopted with a 15–30–15 s duration. A total of 5 block tests were carried out in each cycle, with a total time of 300 s (Fig. 3). The participants were asked to begin in a relaxed seated position, and patients were instructed to avoid any movement except for the motor task required during the procedure to prevent motion artifacts from interfering with the blood oxygenation data. Before the test, the subjects were briefed in detail about the test procedure and rehearsed the exercise tasks. After the formal start of collection, the eyes were first closed and relaxed for 15 s, and the participants were asked to clear their minds as much as possible. This was followed by a 30-s task phase, in which the subject was asked to perform three passive grasping and opening maneuvers of the affected hand, assisted by the rehabilitation robot. The relaxation state continued for 15 s at the end of the task.

Data processing

The fNIRS data were preprocessed and analyzed with fNIRS system data processing software (LIGHTNIRS, Shimadzu Corporation, Japan, Available from: https://www.shimadzu.com.cn/an/products/software-informatics/labsolutions-series/labsolutions-ir/index.html) as follows: (1) Channels with significant motor artifacts were discarded, and the signals from the left and right brain regions (10 channels on each side) were superimposed and averaged separately. (2) Filter: The signal was passed through a bandpass filter with a frequency band of 0.01–0.08 Hz to remove significant periodic noise components, including heart rate noise (1 Hz), respiration (0.2–0.3 Hz), Meyer wave noise (0.1 Hz), and very low-frequency physiologic fluctuation noise (< 0.01 Hz). (3) Task-based averaging: Relative changes in oxyhemoglobin (Oxy-Hb) concentration were block-averaged (5 blocks × 15–30–15 s trial units). (4) Smoothing and baseline correction: Data were processed with Savitzky–Golay smoothing (window = 5, passes = 1) followed by baseline subtraction using two intervals29 (-15–0 s and 30–45 s). (5) The centroid value (CV) and integral value (IV) were calculated on the basis of the changes in Oxy-Hb levels. The IV, which is expressed in millimolar millimeters (mmol·mm), represents the cumulative changes in cerebral hemodynamics during the task period. The integral value is calculated using Eq. (1), where Oxy-Hb(t) denotes the Oxy-Hb concentration at time t; ttask start and ttask end represent the start and end times of the task, respectively; and d denotes the integral. A higher IV indicates stronger brain activation during the task30. The centroid value (CV) reflects the speed of brain activation. It is determined by first calculating the total change in Oxy-Hb concentration during the test period. The time at which the concentration change reaches half of the total change is defined as the CV value, which is expressed in seconds (s)26. The CV value is calculated using Eq. (2), which identifies tcv such that the equation holds true. A lower CV value indicates faster brain activation in the task. (6) The normality of the centroid and integral values before and after intervention in the two groups was assessed using the Shapiro‒Wilk test. Statistical analysis methods were selected on the basis of whether the data conformed to a normal distribution.

Statistical analysis

Statistical analyses were performed via SPSS software (version 24; SPSS Inc., Chicago, IL), and a p value < 0.05 was considered to indicate statistical significance. Continuous variables were tested for normality via the Shapiro‒Wilk test. Data that conformed to a normal distribution (age, IV, and CV) are expressed as the mean ± standard deviation (M ± SD). Repeated measures analysis of variance was used for between- and within-group comparisons. Data that did not adhere to a normal distribution (FMA–UE, FMA-UH, MBI) are expressed as medians (interquartile ranges). The Kruskal‒Wallis test was used for between-group analysis, Bonferroni correction was used for two‒two comparisons, and the Wilcoxon signed‒rank test was used for within-group analysis. The IV and CV derived from fNIRS analysis were subjected to normality tests and were found to conform to a normal distribution. Therefore, the data are presented as the means ± standard deviations and were analyzed using repeated-measures analysis of variance (ANOVA). For categorical variables (sex, stroke type) expressed as rates or %, the baseline characteristics of the three groups of patients were compared with the chi-square test or Fisher’s exact test.

Results

Participant characteristics

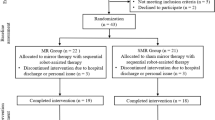

The recruitment process is shown in Fig. 4. From November 2024 to February 2025, 112 patients with RHD were recruited at the China Rehabilitation Research Center. Among them, 39 did not meet the inclusion criteria, 2 refused to participate in the trial, and 11 were excluded for other reasons. Finally, 60 patients were enrolled in the study, among whom 7 dropped out during the study because of the impact of the COVID-19 epidemic; these patients were discharged early. Ultimately, 53 patients were included, and no adverse events occurred during the experimental period.

Information on patient demographics is shown in Table 1. There were 17 participants in the MRT group, 19 in the PM group, and 17 in the FOT group. There was no significant difference among the three groups in terms of sex (x2 = 1.943, p = 0.379) or stroke type (x2 = 1.120, p = 0.571). The mean ages of the FOT, PM and MRT groups were 54.06 ± 10.22, 54.05 ± 10.59, and 54.53 ± 12.09 years, respectively, and the difference was not statistically significant (F = 0.011, p = 0.989).

The clinical baseline characteristics are shown in Table 1. Before the intervention, neither the FMA–UE (p = 0.548) nor the MBI (p = 0.300) significantly differed among the groups, and the FMA–WH score was 0 in all three groups. There were no significant differences in the distributions of any of the other baseline characteristics among the three groups.

Changes in clinical outcomes

Changes in clinical outcomes are shown in Table 2. An improvement in upper-limb dysfunction on the paralyzed side was observed in all three groups (Fig. 5a). Compared with baseline, after treatment, all three groups presented significant improvements in FMA–UE scores (p < 0.001). A comparison among the groups revealed that there was a significant difference in the FMA–UE score after the intervention (p = 0.009). Further Bonferroni correction was performed for two-by-two comparisons. The FMA–UE scores were significantly higher in the MRT group than in the PM (p = 0.020) and FOT groups (p = 0.029) after the intervention.

Compared with those at baseline, at the end of the 4-week intervention, FMA–WH scores were significantly higher in the FOT group (p = 0.017) and the MRT group (p = 0.002). However, there was no significant difference in this measure for the PM group (p = 0.063). Posttest analysis revealed that there was a significant difference in the FMA–WH score among the three groups (p = 0.004). However, the two-by-two comparison revealed that the MRT group had significantly higher FMA–WH scores than the PM group did (p = 0.003) (Fig. 5b).

In addition to improvements in upper extremity function and wrist-hand function, the ability to perform activities of daily life was also improved in all three groups. Compared with the pretest MBI scores, the posttest scores were significantly greater in all three groups (p < 0.001). Comparisons among the groups also revealed a significant difference in the MBI score (p = 0.010). Further Bonferroni correction revealed that the improvement in MBI scores in the MRT group was significantly greater than that in the FOT group (p = 0.023) and the PM group (p = 0.026) (Fig. 5c).

Clinical outcome assessment. (a) FMA–UE: Fugl–Meyer Assessment–Upper Extremity; (b) FMA–WH: Fugl–Meyer Assessment–Wrist and Hand; (c) MBI: Modified Barthel Index. “*” indicates significant changes from the pretest to the posttest, and “#” indicates a significant difference between groups. (MRT: Robot-assisted mirror therapy, PM: Passive movement, FOT: Functional occupational therapy.)

fNIRS results

Several patients had missing fNIRS data for various reasons. Data were missing for 2 patients in the MRT group and 2 patients in the PM group. Two outliers in the FOT group were removed during the process. Finally, 47 patients were included in the final analysis, including 15 each in the MRT and FOT groups and 17 in the PM group.

After the Shapiro‒Wilk test, the integral and centroid values of the left and right sides of the three groups of patients conformed to a normal distribution (p > 0.05). Repeated-measures ANOVA was used for comparisons.

The results are shown in Table 3. There was no significant difference in the integral or centroid value between the left and right sides among the three groups before intervention (p > 0.05). There was also no significant difference between the integral and centroid values of the left and right sides among the three groups after the intervention (p > 0.05).

There was no significant difference between the left and right integral values or the right center of gravity values of the three groups before and after the intervention (p > 0.05). There was a significant difference in the left centroid value in the FOT group before and after the intervention (p = 0.004) (Fig. 6).

Analysis of fNIRS data. (a) Left side IV: Left side integral value; (b) Right side IV: Right side integral value; (c) Left side CV: Left side: Left side integral value; (d) Right side CV: Right side centroid value. “*” indicates significant changes from pretest to posttest. “#” indicates a significant difference between groups. (MRT: Robot-assisted mirror therapy group; PM: Passive Movement group; FOT: Functional Occupational Therapy group).

Discussion

In this study, we performed fNIRS to investigate the effects the MRT on upper limb function and brain activation in RHD patients. The clinical outcomes of the FMA–UL and FMA–WH, the MBI and the brain activation captured by fNIRS before and after the different interventions were compared. The results demonstrated that MRT not only improved the function and daily mobility of the affected upper limb but also alleviated the appearance of abnormal brain activation. There were no adverse events or side effects during the process, demonstrating that MRT is a safe and feasible technique for poststroke rehabilitation.

After stroke, the ability of the limb on the paralyzed side to aid in performing activities of daily life decreases significantly, which can lead to functional disability in the long term31. Interestingly, the results of this study revealed that all three groups of patients experienced significant improvements in upper extremity function and daily living ability after the intervention, with the MRT group experiencing greater overall improvement. Both MT and repetitive rehabilitation are effective treatments for improving upper-limb motor function after stroke32. MRT training combines the advantages of movement observations, movement imagination and movement attempts. The patient passively imitates healthy hand movements with the assistance of the robot and performs repetitive training on both sides to establish the correct movement pattern. This method compensates for the lack of motor feedback under pure mirror image training and provides repeatable and standardized training33. The results of this study demonstrated that MRT training can activate motor neurons in the bilateral upper limbs, increase motor feedback, reduce the risk of wasting the affected limbs, and improve patients’ upper limb function, which is consistent with the results of previous studies34.

Passive and FOT training interventions provide only peripheral effects. MRT intervention combines the highly repetitive peripheral intervention of rehabilitation robots and the central intervention of MT through the engagement of opto-motor neurons35forming a closed “central–peripheral–central” loop, enhancing motor and sensory feedback and input and promoting functional improvement in stroke patients36,37,38. Ding et al.37. reported that closed-loop training based on MT could significantly improve motor function and independence in performing activities of daily life in poststroke patients. This finding is consistent with the results shown in this study, in which, after 4 weeks of intervention, the MRT group had better upper-limb function and participation in activities of daily living than the other two groups did, confirming the theory that treatment techniques based on the closed-loop rehabilitation theory are more effective in rehabilitating poststroke motor dysfunction.

Functional near-infrared spectroscopy (fNIRS) is a novel noninvasive optical imaging technique that measures changes in oxyhemoglobin and deoxyhemoglobin in brain tissue using near-infrared light39. This method indirectly reflects the activity of neurons and is an important tool and basis for studying brain function and related neural mechanisms40. After stroke, the cerebral cortex undergoes significant structural and functional plasticity changes over several weeks to months following the infarct. Compared with healthy individuals, stroke patients typically exhibit abnormal activation patterns41,42. A study analyzed the activation of bilateral motor cortices in stroke patients during a motor task and reported that during a reaching task with the paretic arm, the supplementary motor area in the affected cerebral hemisphere exhibited hyperactivation. This phenomenon may be closely related to the trunk compensation strategies employed by patients during task performance or the extent of brain damage43,44. The IV is an important parameter reflecting the degree of brain region activation. The larger the area under the oxyhemoglobin concentration change curve during the task is, the greater the value, indicating a stronger hemodynamic response in that brain region during the task45. In this study, we performed statistical analyses on the integral values of the three groups before and after the intervention. Although no significant differences were observed among the three groups, the mean integral values of the bilateral brain regions in the MRT group were lower than those in the other two groups. One study suggested that stroke patients with better neural functional recovery may exhibit lower levels of brain activation when performing specific tasks, potentially due to increased neural efficiency, which allows them to utilize fewer neural resources46. Bai et al.47. assessed the cortical activation effects of mirror visual feedback training on upper limb movement using fNIRS and reported that mirror therapy significantly reduced the activation of the primary motor cortex (M1), which is consistent with the observed decrease in mean integral values in this study. Michielsen et al.48. further revealed that mirror therapy promotes the normalization of interhemispheric activation balance, primarily through a reduction in the activation of the nonaffected M1. This finding is in line with the results of the fNIRS analysis in this study, which revealed a greater decrease in the mean integral value on the left side. This study suggests that the MRT may optimize brain activation patterns and enhance neural efficiency, thereby reducing the amount of brain activation required to perform motor tasks. This could explain the more significant functional improvements observed in the MRT group in terms of FMA-UE and MBI scores.

Under normal conditions, there is dynamic functional connectivity and mutual inhibition between the two hemispheres of the brain. However, when a stroke occurs, the function of the affected hemisphere is inhibited, which may lead to excessive excitability of the contralateral hemisphere, thereby interfering with the recovery of the affected hemisphere49. According to the theory of interhemispheric competition and inhibition, simply enhancing the excitability of the affected hemisphere is not sufficient during the rehabilitation of stroke patients. It is also necessary to modulate the excitability of the contralateral hemisphere to prevent its overactivation, thereby further promoting the recovery of the affected cerebral hemisphere50. Thus, in rehabilitation interventions, controlling the excessive excitability of the contralateral hemisphere has emerged as a key factor in improving patients’ motor functions. In this study, we observed a reduction in the centroid value of the left hemisphere in the PM group following the intervention. Although this result did not reach statistical significance, it may suggest that the activation speed of the left cortical region increased during the intervention51. This phenomenon may reflect the limitations of passive intervention methods, which fail to effectively suppress the excessive excitability of the contralateral hemisphere. This inadequacy may explain the lack of significant improvement in the FMA-WH scores of patients in the PM group. In contrast, following the intervention in the FOT group, a significant increase in the centroid value of the left hemisphere was observed, indicating that FOT training effectively modulated the excitability of the contralateral cerebral hemisphere. This regulatory effect may be attributed to the incorporation of more cognitive training and personalized treatments in the intervention process of the FOT group. By activating neurons and prolonging the activation time of the contralateral cortex, the FOT promotes interhemispheric balance, which manifests as an increased centroid value. Zheng et al.. also demonstrated that multisensory integration and interactive patterns are beneficial for improving cortical activation in stroke patients and enhancing their cognitive control abilities, findings that are consistent with the results of this study52.

A functional magnetic resonance imaging (fMRI) study revealed that in stroke patients, the connectivity between the default mode network (DMN) and the task-related network (TRN) is weakened or disrupted. This impairs the rapid and efficient transfer of information across brain regions during task execution, resulting in slower brain activation43. Without appropriate intervention, this delayed activation and slow information transfer in the brain following stroke can have negative impacts on patients’ functional recovery. It is important to provide stroke patients with sensory feedback in an appropriate manner to stimulate the activation of the primary motor cortex, which may promote functional recovery42. The results of this experiment show that, compared with the other two groups, the MRT group had the smallest mean centroid value in the right hemisphere. This may be because, under MRT training, the unaffected hand can drive the movement of the affected hand through the exoskeleton, stimulating neural activity in the motor cortex of the affected hemisphere. This process can modulate the response speed of brain regions to target tasks and optimize the activation patterns between hemispheres, prioritizing the activation of the primary motor cortex of the affected hemisphere during the affected hand’s attempt to grasp actively, thereby achieving better functional recovery outcomes. Bonnal et al.conducted a study on visual mirror feedback in healthy individuals, and the results similarly indicated that mirror feedback can more effectively reduce interhemispheric inhibition and promote neuroplasticity mechanisms in patients with brain injury53.

This study has several limitations. First, our intervention time was short; participants in each group only engaged in 10 min of robot-assisted passive training or MRT on the basis of conventional intervention times, which may have been insufficient for achieving the optimal training effect. However, the experimental design involved controlling the variables, and the intervention time was 10 min in each group to ensure that the group results were comparable. The training time should be further extended in subsequent studies. Second, the task paradigm tested in fNIRS was designed to be performed via a robot-assisted grasping task. The final fNIRS results revealed that only the left center of gravity values were significantly different. We hypothesized that the passive motor paradigm may have resulted in insignificant neural activity during the patient’s task, affecting the assessment. Therefore, we will further adjust the task paradigm design in future experiments. Moreover, the present study provides only a preliminary exploration of the intervention effects of MRT training. In future research, we will further refine the experimental design to observe the long-term intervention effects and the sustainability of the effects of mirror robot training, thereby providing more robust evidence for clinical practice.

Conclusion

In conclusion, this study fully confirms the significant efficacy of MRT for patients with RHD, which can effectively improve patients’ upper-limb motor function and daily activity ability. Moreover, through the use of a neuroimaging technique—fNIRS—the trend of the beneficial effects of MRT on the brain function of stroke patients was further validated. MRT intervention is characterized by portability and ease of operation, which allows it to be widely used in the rehabilitation training of stroke patients, providing more possibilities for patient rehabilitation treatment and important clinical application value.

Data availability

The datasets used and/or analyzed in the current study are available from the corresponding author F.H. upon reasonable request.

References

Resquín, F. et al. Hybrid robotic systems for upper limb rehabilitation after stroke: A review. Med. Eng. Phys. 38, 1279–1288. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.medengphy.2016.09.001 (2016).

Mollà-Casanova, S., Llorens, R., Borrego, A., Salinas-Martínez, B. & Serra-Añó, P. Validity, reliability, and sensitivity to motor impairment severity of a multi-touch app designed to assess hand mobility, coordination, and function after stroke. J. Neuroeng. Rehabil. 18, 70. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12984-021-00865-9 (2021).

Liu, H. et al. The interrelation of blood Urea Nitrogen-to-Albumin ratio with Three-Month clinical outcomes in acute ischemic stroke cases: A secondary analytical exploration derived from a prospective cohort study. Int. J. Gen. Med. 17, 5333–5347. https://doi.org/10.2147/ijgm.S483505 (2024).

Ranzani, R. et al. Neurocognitive robot-assisted rehabilitation of hand function: a randomized control trial on motor recovery in subacute stroke. J. Neuroeng. Rehabil. 17, 115. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12984-020-00746-7 (2020).

Lum, P. S., Godfrey, S. B., Brokaw, E. B., Holley, R. J. & Nichols, D. Robotic approaches for rehabilitation of hand function after stroke. Am. J. Phys. Med. Rehabil. 91, 242–254. https://doi.org/10.1097/PHM.0b013e31826bcedb (2012).

Wolf, S. L. et al. Effect of constraint-induced movement therapy on upper extremity function 3 to 9 months after stroke: the EXCITE randomized clinical trial. Jama 296, 2095–2104. https://doi.org/10.1001/jama.296.17.2095 (2006).

Rocha, L. S. O. et al. Constraint induced movement therapy increases functionality and quality of life after stroke. J. Stroke Cerebrovasc. Dis. 30, 105774. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jstrokecerebrovasdis.2021.105774 (2021).

Prange, G. B., Jannink, M. J., Groothuis-Oudshoorn, C. G., Hermens, H. J. & Ijzerman, M. J. Systematic review of the effect of robot-aided therapy on recovery of the hemiparetic arm after stroke. J. Rehabil Res. Dev. 43, 171–184. https://doi.org/10.1682/jrrd.2005.04.0076 (2006).

Chong, D. S. T. et al. Mirror therapy for the management of Phantom limb pain: A Single- center experience. Ann. Vasc Surg. 95, 184–187. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.avsg.2023.03.033 (2023).

Chen, Z. et al. An overview of in vitro biological neural networks for robot intelligence. Cyborg Bionic Syst. 4, 0001. https://doi.org/10.34133/cbsystems.0001 (2023).

Kim, H., Lee, E., Jung, J. & Lee, S. Utilization of mirror visual feedback for upper limb function in poststroke patients: A systematic review and Meta-Analysis. Vis. (Basel). 7. https://doi.org/10.3390/vision7040075 (2023).

Chen, Y. et al. Towards Human-like walking with Biomechanical and neuromuscular control features: personalized attachment point optimization method of Cable-Driven exoskeleton. Front. Aging Neurosci. 16, 1327397. https://doi.org/10.3389/fnagi.2024.1327397 (2024).

Zhang, Z. et al. Magnetically switchable adhesive millirobots for universal manipulation in both air and water. Adv. Mater. 37, e2420045. https://doi.org/10.1002/adma.202420045 (2025).

Altschuler, E. L. et al. Rehabilitation of hemiparesis after stroke with a mirror. Lancet 353, 2035–2036. https://doi.org/10.1016/s0140-6736(99)00920-4 (1999).

Nishi, K. et al. Mirror therapy reduces pain and preserves corticomotor excitability in human experimental skeletal muscle pain. Brain Sci. 14 https://doi.org/10.3390/brainsci14030206 (2024).

Bertani, R. et al. Effects of robot-assisted upper limb rehabilitation in stroke patients: a systematic review with meta-analysis. Neurol. Sci. 38, 1561–1569. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10072-017-2995-5 (2017).

Jihun, K. & Jaehyo, K. Robot-assisted mirroring exercise as a physical therapy for hemiparesis rehabilitation. Annu. Int. Conf. IEEE Eng. Med. Biol. Soc. 2017, 4243–4246. https://doi.org/10.1109/embc.2017.8037793 (2017).

Wei, Y. et al. Investigating the effect of different types of exercise on upper limb functional recovery in patients with right hemisphere damage based on fNIRS. J. Vis. Exp. https://doi.org/10.3791/65996 (2024).

Miao, Q., Fu, X. & Chen, Y. F. Sensing equivalent kinematics enables robot-assisted mirror rehabilitation training via a broaden learning system. Front. Bioeng. Biotechnol. 12, 1484265. https://doi.org/10.3389/fbioe.2024.1484265 (2024).

Wei, D., Hua, X. Y., Zheng, M. X., Wu, J. J. & Xu, J. G. Effectiveness of robot-assisted virtual reality mirror therapy for upper limb motor dysfunction after stroke: study protocol for a single-center randomized controlled clinical trial. BMC Neurol. 22, 307. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12883-022-02836-6 (2022).

Schrader, M. et al. The effect of mirror therapy can be improved by simultaneous robotic assistance. Restor. Neurol. Neurosci. 40, 185–194. https://doi.org/10.3233/rnn-221263 (2022).

Thieme, H. et al. Mirror therapy for patients with severe arm paresis after stroke–a randomized controlled trial. Clin. Rehabil. 27, 314–324. https://doi.org/10.1177/0269215512455651 (2013).

Sanford, J., Moreland, J., Swanson, L. R., Stratford, P. W. & Gowland, C. Reliability of the Fugl-Meyer assessment for testing motor performance in patients following stroke. Phys. Ther. 73, 447–454. https://doi.org/10.1093/ptj/73.7.447 (1993).

Zhuang, J. Y., Ding, L., Shu, B. B., Chen, D. & Jia, J. Associated Mirror Therapy Enhances Motor Recovery of the Upper Extremity and Daily Function after Stroke: A Randomized Control Study. Neural Plast 7266263 (2021). https://doi.org/10.1155/2021/7266263 (2021).

Hong, I. et al. Equating activities of daily living outcome measures: the functional independence measure and the Korean version of modified Barthel index. Disabil. Rehabil. 40, 217–224. https://doi.org/10.1080/09638288.2016.1247468 (2018).

Paulmurugan, K., Vijayaragavan, V., Ghosh, S., Padmanabhan, P. & Gulyás, B. Brain-Computer interfacing using functional Near-Infrared spectroscopy (fNIRS). Biosens. (Basel). 11. https://doi.org/10.3390/bios11100389 (2021).

Zhao, Y. N., Han, P. P., Zhang, X. Y. & Bi, X. Applications of functional Near-Infrared spectroscopy (fNIRS) neuroimaging during rehabilitation following stroke: A review. Med. Sci. Monit. 30, e943785. https://doi.org/10.12659/msm.943785 (2024).

Bernardes-Oliveira, E. et al. Spectrochemical differentiation in gestational diabetes mellitus based on attenuated total reflection Fourier-transform infrared (ATR-FTIR) spectroscopy and multivariate analysis. Sci. Rep. 10, 19259. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-020-75539-y (2020).

Takizawa, R. et al. Neuroimaging-aided differential diagnosis of the depressive state. Neuroimage 85 Pt. 1, 498–507. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.neuroimage.2013.05.126 (2014).

Ham, Y., Yang, D. S., Choi, Y. & Shin, J. H. Effectiveness of mixed reality-based rehabilitation on hands and fingers by individual finger-movement tracking in patients with stroke. J. Neuroeng. Rehabil. 21, 140. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12984-024-01418-6 (2024).

Pollock, A. et al. Interventions for improving upper limb function after stroke. Cochrane Database Syst. Rev. 2014 (Cd010820). https://doi.org/10.1002/14651858.CD010820.pub2 (2014).

Chien, W. T., Chong, Y. Y., Tse, M. K., Chien, C. W. & Cheng, H. Y. Robot-assisted therapy for upper-limb rehabilitation in subacute stroke patients: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Brain Behav. 10, e01742. https://doi.org/10.1002/brb3.1742 (2020).

Alsubiheen, A. M., Choi, W., Yu, W. & Lee, H. The effect of Task-Oriented activities training on Upper-Limb function, daily activities, and quality of life in chronic stroke patients: A randomized controlled trial. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public. Health. 19 https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph192114125 (2022).

Pournajaf, S. et al. Neurophysiological and clinical effects of upper limb Robot-Assisted rehabilitation on motor recovery in patients with subacute stroke: A multicenter randomized controlled trial study protocol. Brain Sci. 13 https://doi.org/10.3390/brainsci13040700 (2023).

Jia, J. Exploration on Neurobiological mechanisms of the central-peripheral-central closed-loop rehabilitation. Front. Cell. Neurosci. 16, 982881. https://doi.org/10.3389/fncel.2022.982881 (2022).

Gandhi, D. B., Sterba, A., Khatter, H. & Pandian, J. D. Mirror therapy in stroke rehabilitation: current perspectives. Ther. Clin. Risk Manag. 16, 75–85. https://doi.org/10.2147/tcrm.S206883 (2020).

Ding, L. et al. Camera-Based mirror visual input for priming promotes motor recovery, daily function, and brain network segregation in subacute stroke patients. Neurorehabil Neural Repair. 33, 307–318. https://doi.org/10.1177/1545968319836207 (2019).

Kinoshita, S., Tamashiro, H., Okamoto, T., Urushidani, N. & Abo, M. Association between imbalance of cortical brain activity and successful motor recovery in sub-acute stroke patients with upper limb hemiparesis: a functional near-infrared spectroscopy study. Neuroreport 30, 822–827. https://doi.org/10.1097/wnr.0000000000001283 (2019).

Liu, Z. et al. Classification of three anesthesia stages based on Near-Infrared spectroscopy signals. IEEE J. Biomed. Health Inf. 28, 5270–5279. https://doi.org/10.1109/jbhi.2024.3409163 (2024).

Puh, U., Vovk, A., Sevsek, F. & Suput, D. Increased cognitive load during simple and complex motor tasks in acute stage after stroke. Int. J. Psychophysiol. 63, 173–180. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ijpsycho.2006.03.011 (2007).

Huo, C. et al. Limb linkage rehabilitation training-related changes in cortical activation and effective connectivity after stroke: A functional near-infrared spectroscopy study. Sci. Rep. 9, 6226. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-019-42674-0 (2019).

Rehme, A. K., Eickhoff, S. B., Rottschy, C., Fink, G. R. & Grefkes, C. Activation likelihood Estimation meta-analysis of motor-related neural activity after stroke. Neuroimage 59, 2771–2782. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.neuroimage.2011.10.023 (2012).

Muller, C. O. et al. Brain-movement relationship during upper-limb functional movements in chronic post-stroke patients. J. Neuroeng. Rehabil. 21, 188. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12984-024-01461-3 (2024).

Chen, Z. et al. Heavier load alters upper limb muscle synergy with correlated fNIRS responses in BA4 and BA6. Cyborg Bionic Syst. 4, 0033. https://doi.org/10.34133/cbsystems.0033 (2023).

Leff, D. R. et al. Assessment of the cerebral cortex during motor task behaviours in adults: a systematic review of functional near infrared spectroscopy (fNIRS) studies. Neuroimage 54, 2922–2936 https://doi.org/10.1016/j.neuroimage.2010.10.058 (2011).

Lamberti, N. et al. Cortical oxygenation during a motor task to evaluate recovery in subacute stroke patients: A study with Near-Infrared spectroscopy. Neurol. Int. 14, 322–335. https://doi.org/10.3390/neurolint14020026 (2022).

Bai, Z., Fong, K. N. K., Zhang, J. & Hu, Z. Cortical mapping of mirror visual feedback training for unilateral upper extremity: A functional near-infrared spectroscopy study. Brain Behav. 10, e01489. https://doi.org/10.1002/brb3.1489 (2020).

Michielsen, M. E. et al. Motor recovery and cortical reorganization after mirror therapy in chronic stroke patients: a phase II randomized controlled trial. Neurorehabil Neural Repair. 25, 223–233. https://doi.org/10.1177/1545968310385127 (2011).

Murase, N., Duque, J., Mazzocchio, R. & Cohen, L. G. Influence of interhemispheric interactions on motor function in chronic stroke. Ann. Neurol. 55, 400–409. https://doi.org/10.1002/ana.10848 (2004).

Boddington, L. J. & Reynolds, J. N. J. Targeting interhemispheric Inhibition with neuromodulation to enhance stroke rehabilitation. Brain Stimul. 10, 214–222. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.brs.2017.01.006 (2017).

Li, X., Huang, F., Guo, T., Feng, M. & Li, S. The continuous performance test aids the diagnosis of post-stroke cognitive impairment in patients with right hemisphere damage. Front. Neurol. 14, 1173004. https://doi.org/10.3389/fneur.2023.1173004 (2023).

Zheng, J. et al. Cognitive and motor cortex activation during robot-assisted multi-sensory interactive motor rehabilitation training: an fNIRS based pilot study. Front. Hum. Neurosci. 17, 1089276. https://doi.org/10.3389/fnhum.2023.1089276 (2023).

Bonnal, J., Ozsancak, C., Prieur, F. & Auzou, P. Video mirror feedback induces more extensive brain activation compared to the mirror box: an fNIRS study in healthy adults. J. Neuroeng. Rehabil. 21, 78. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12984-024-01374-1 (2024).

Acknowledgements

This study was supported by the Project of China Rehabilitation Research Center (number: 2021zx-Q5) and Capital’s Funds for Health Improvement and Research (CFH2024-2-6015).

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

Y.W. was involved in the study design and collected the data. L.W. analyzed the data and wrote the manuscript. R.F. and J.L. collected and analyzed the data. L.L. organized the manuscript.Y.W. organized the data. F.H. participated in the experimental conceptualization and provided guidance. All the authors reviewed the scripts.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher’s note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if you modified the licensed material. You do not have permission under this licence to share adapted material derived from this article or parts of it. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Wei, Y., Wu, L., Huang, F. et al. Effects of robot assisted mirror therapy on motor function and cortical activation in patients with right hemisphere damage. Sci Rep 15, 33490 (2025). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-16686-y

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-16686-y