Abstract

In the evolving field of healthcare, centralized cloud-based medical image retrieval faces challenges related to security, availability, and adversarial threats. Existing deep learning-based solutions improve retrieval but remain vulnerable to adversarial attacks and quantum threats, necessitating a shift to more secure distributed cloud solutions. This article proposes SFMedIR, a secure and fault tolerant medical image retrieval framework that contains an adversarial attack-resistant federated learning for hashcode generation, utilizing a ConvNeXt-based model to improve accuracy and generalizability. The framework integrates quantum-chaos-based encryption for security, dynamic threshold-based shadow storage for fault tolerance, and a distributed cloud architecture to mitigate single points of failure. Unlike conventional methods, this approach significantly improves security and availability in cloud-based medical image retrieval systems, providing a resilient and efficient solution for healthcare applications. The framework is validated on Brain MRI and Kidney CT datasets, achieving a 60-70% improvement in retrieval accuracy for adversarial queries and an overall 90% retrieval accuracy, outperforming existing models by 5-10%. The results demonstrate superior performance in terms of both security and retrieval efficiency, making this framework a valuable contribution to the future of secure medical image management.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

The digital transformation of healthcare has ushered in an era of unprecedented connectivity and efficiency, largely driven by the adoption of cloud-based systems. These platforms not only facilitate seamless storage and sharing of Electronic Health Records (EHRs) but also address scalability challenges posed by the rapid growth of medical data1. Among the various types of healthcare data, medical images such as CT scans, MRIs, and X-rays play a critical role in diagnosis, treatment planning, and monitoring2. The demand for efficient and secure cloud-based storage and retrieval of these images is amplified by their exponential growth, with estimates suggesting that medical image data could exceed 630 petabytes by 20303. Cloud platforms like Google Cloud, Microsoft Azure, and AWS enable the storage and retrieval of such vast datasets, fostering collaboration and real-time access across healthcare institutions4. However, the reliance on third-party cloud systems raises critical security concerns, including data breaches, unauthorized access, and potential tampering, necessitating robust solutions to ensure data confidentiality, integrity, and availability5,6,7.

Storing medical images securely in the cloud typically involves encryption techniques, which provide a foundational layer of protection. While traditional encryption schemes8,9,10 address confidentiality, they often fall short of ensuring data integrity and resistance against emerging threats. Furthermore, as we move toward the quantum era, the limitations of classical encryption methods become more pronounced. Quantum-capable adversaries pose a significant risk to these traditional approaches11. Current encryption methods are not designed to prevent intelligent tampering with encrypted data, which could lead to compromised diagnostic accuracy. Moreover, secure storage alone is insufficient; the ability to retrieve medical images accurately and efficiently from encrypted datasets without exposing sensitive information is equally critical12.

Content-Based Medical Image Retrieval (CBMIR) is pivotal for querying relevant medical images from databases using visual content, facilitating accurate diagnoses and effective treatments13. One approach to improving CBMIR efficiency is the use of similarity-preserving hashcodes, which enable rapid indexing and retrieval. Models like Deep Pairwise Hashing (DPH)14 and Improved Deep Hash Network (IDHN)15 generate these hashcodes efficiently, but their unencrypted nature exposes them to adversarial attacks, particularly pattern-based intrusions16. Moreover, CBMIR faces significant challenges, including slow search times, difficulty achieving precise retrieval results, and susceptibility to malicious manipulations. These issues can distort retrieval outcomes, compromise reliability, and erode trust in the system. Ensuring accuracy and security in CBMIR is vital to unlocking its full potential for modern healthcare applications. Encrypting hashcodes can mitigate this vulnerability, yet it often comes at the cost of retrieval performance, creating a trade-off between security and efficiency17. Another challenge arises in the centralized training of hashcode generation models, where aggregating vast medical image datasets from distributed healthcare providers poses privacy and logistical concerns. Federated Learning (FL) offers a viable solution, allowing institutions to collaboratively train models without centralizing sensitive data. FL not only ensures data privacy but also enhances the robustness of hashcode generation, making it suitable for secure, distributed CBMIR systems18.

Despite the advances in hashcode generation and federated learning, ensuring fault tolerant storage and retrieval of medical images remains a concern. Distributed cloud architectures employing master-slave models offer a path toward resilient systems, but traditional secret-sharing schemes used for fault tolerance are prone to pattern or access-based attacks19,20,21. Malicious actors can exploit shared data to infer sensitive information, compromising the system’s robustness. Introducing randomness and dynamic thresholding mechanisms into secret-sharing schemes can mitigate these vulnerabilities, paving the way for a secure and fault tolerant framework. The overview of the cloud-based storage and retrieval framework in the distributed healthcare environment is shown in Fig. 1.

Existing solutions primarily address individual challenges such as image security, fault tolerance, or retrieval accuracy, but a unified system that effectively integrates all these aspects is lacking, as discussed above. To address these multifaceted challenges, SFMedIR, a Secure and Fault tolerant cloud-based framework for Medical Image Retrieval in a distributed environment, is proposed. The contributions of this work are as follows:

-

A novel cloud-based framework, SFMedIR, for secure and fault tolerant medical image retrieval in a distributed environment is proposed.

-

Quantum-chaos-based image encryption is employed to ensure robust security for medical images against advanced threats.

-

To ensure secure and accurate retrieval, Federated Learning is utilized to generate context-aware, similarity-preserving hashcodes that are resistant to adversarial attacks.

-

A dynamic threshold-based shadow generation scheme is proposed to enhance security and fault tolerance during the retrieval process. A formal security analysis is conducted to validate the framework.

-

SFMedIR is evaluated using Mean Average Precision (mAP), latency, throughput, fault-recovery time for retrieval performance, and formal analysis for security and retrieval efficiency. Experiments on Brain MRI and Kidney CT datasets show a 60-70% retrieval accuracy improvement under adversarial conditions.

The structure of the paper is as follows: Section "Related work" reviews related works, highlighting existing approaches and their limitations. Section "System architecture" elaborates on the proposed SFMedIR framework, explaining its design and components. Section "Formal analysis and verification" focuses on the formal analysis of the framework from a security and retrieval accuracy perspective, while Section "Experimental results and performance analysis" discusses the experimental evaluation and performance results. Finally, Section Conclusion and future work concludes the study with key findings.

Related work

In this section, the authors detail an overview of existing secure image retrieval systems and discuss their issues. Secure and privacy-preserving image retrieval ensures efficient searches in encrypted databases without compromising performance22,23. Approaches in this domain are broadly classified into two categories. The first involves generating secure indexes from image features, encrypting the images, and storing them in the cloud. The second leverages the cloud for feature extraction and secure index generation, often using deep hashing to create similarity-preserving hashcodes24,25. Xu et al.26 introduced a cloud-based system combining Hamming embedding and Min-hash for enhanced accuracy. Du et al.27 employed deep hashing with Secure k-NN and DNA-based chaotic encryption, later enhancing accuracy using a 4D hyperchaotic map28. Janani et al.29 designed a multiparty-based similarity matching, while Zhu et al.30 introduced Privacy-preserving Mahalanobis Distance Comparison (PMDC) for enhanced privacy.

Similarity-preserving hashcodes are vulnerable to both targeted and non-targeted adversarial attacks, posing significant risks in the healthcare domain due to the critical nature of medical data. Ma et al.31 analyzed the impact of adversarial attacks on deep learning-based medical image analysis systems, emphasizing the severe implications such attacks could have on diagnostic accuracy. To address such vulnerabilities, Yuan et al.32 proposed semantic-aware hashcode generation for image retrieval. Their approach fabricates adversarial examples by maximizing the Hamming distance between the hashcodes of adversarial samples and primary features, demonstrating its efficacy in adversarial attack trials. However, these methods rely on centralized training for hashcode generation, which limits their scalability and privacy. Tabatabaei et al.33 advanced the field by introducing federated learning (FL)-based medical image retrieval system for global applications. FL-based training enhances privacy by ensuring that data remains decentralized during training, making the model inherently more robust34. Despite this innovation, there remains no FL-based adversarial-attack-resistant hashcode generation model capable of addressing multiple challenges with a unified solution35.

Medical images are frequently stored in centralized cloud infrastructures, which are prone to single points of failure. In healthcare, where retrieval time is critical, such centralized systems can be a bottleneck. Distributed cloud solutions offer an alternative. Ajitesh et al.36 proposed a model utilizing trusted edge computing for secure processing and distributed cloud storage for remote sensing images. Their approach involves sharing and storing images in slave servers across the cloud. However, plain image storage increases exposure to threats, necessitating the use of encryption and fragmentation. Zhou et al.37 introduced shadow generation techniques, employing a threshold-based system where images are divided into \(n\) shares, each stored on a separate server. During retrieval, only a subset of these shares is required to reconstruct the image. While effective, these techniques remain susceptible to access-based attacks3839.

The existing literature highlights the pressing need for a federated learning-based, context-aware hashcode generation model that ensures privacy and resilience against adversarial attacks. Additionally, to address access-based vulnerabilities and enhance fault tolerance, there is a clear demand for a distributed and dynamically fragmented image storage system in the cloud. These insights have guided the development of the proposed system, “SFMedIR,” which is specifically designed to meet the stringent requirements of healthcare applications. Table 1 outlines the distinctions between our proposed system and existing retrieval methods.

System architecture

Problem formulation

The proposed system has Trusted Medical Image Owners (MO), Master and Slave Cloud Servers (MCS, SCS), and Medical Image Users (MU), as illustrated in Fig. 2. MO possess a collection of \(\mathbb {N}\) medical images \(\mathbb{M}\mathbb{I}=\{MI_1, MI_2, ..., MI_{\mathbb {N}}\}\) which has to be offloaded to the cloud storage after encrypting the images. MCS takes care of s dynamic shadows generation and metadata storage. MU are able to retrieve most similar images by requesting to the cloud by sending the query image \(MI_q\). These cloud servers provide storage and retrieval services. As cloud servers are honest and curious, the challenge lies in the identification of \(\textit{k}\) most similar images from encrypted images to a specified query image \(MI_q\) while preserving security and ensuring availability. The overall framework design is depicted in Fig. 2. Table 2 lists the notations used with a description.

System model and framework design

Secure and Fault tolerant Cloud-based Medical Image Storage and Retrieval Framework (SFMedIR) in a distributed environment is proposed to achieve the following goals.

-

Attack resistance: The hashing model must be resilient to adversarial attacks, ensuring robustness as medical images play a critical role in digital healthcare.

-

Image security: Medical images should be encrypted and shared in a manner that prevents attackers from extracting any meaningful information.

-

Image availability: The framework should guarantee image availability even in the event of some server failures, ensuring reliable retrieval.

The proposed framework has different entities that work together to ensure secure and fault tolerant retrieval work. Figure 2 shows the proposed SFMedIR architecture. It has two major phases. Storing the medical image in a secure way is the first phase. Here, the MO processes the medical image MI and offloads them to the cloud. MO encrypt the MI using quantum chaos-based image encryption scheme QMedShield proposed by Amaithi Rajan et al.40 and produces EI. From the MI, adversarial attack-resistant hashcode AH is also being derived using the trained model. This hashcode acts as an index while storing and searching. EI and corresponding AH is sent to the MCS. Here, the EI is split into dynamic (r, s) shadows. Where s shadows are stored in slave servers, r shadows are required to reconstruct the original encrypted image. Each shadow Sh is stored in slave cloud servers. In the second phase, MU sends the query hashcode \(H_q\), which is derived from the \(MI_q\) to the MCS. A similar image search is executed, and top-k image indices are selected. For each index in the result set, the original encrypted image has to be constructed with r shadows retrieved from the slave cloud servers. After reconstruction, MIU receives the top-k result images from the MCS, and it decrypts the result images.

Framework design

The framework of the proposed system is outlined in this subsection, with the functionalities of each entity and the corresponding algorithms explained. Key Control Entity KCE handles \(\textsf{KeyGen}\) algorithm. MO runs \(\textsf{QChaosImgEnc}\), \(\textsf{CxtHashGen}\) algorithms. MCS executes \(\textsf{DynamicShadowsGen}\) during secure storage phase and \(\textsf{SimImgSearch}\), \(\textsf{ImgReconstruct}\) during the retrieval phase. MU utilizes \(\textsf{TrapdoorGen}\), \(\textsf{QChaosImgDec}\) algorithms.

-

1.

\(\mathbb {K} \leftarrow \textsf{KeyGen} (1^\lambda )\): This algorithm takes \(\lambda\) parameter as input and outputs the key set \(\mathbb {K}=\{K_{QIE}, K_{rEK}\}\).

-

2.

\(\mathbb{E}\mathbb{I} \leftarrow \textsf{QChaosImgEnc} (\mathbb{M}\mathbb{I}, K_{QIE})\): The quantum chaos-based image encryption algorithm (QMedShield) takes medical images \(\mathbb{M}\mathbb{I}\), and encryption key \(K_{QIE}\) as input, and outputs encrypted medical images \(\mathbb{E}\mathbb{I}\).

-

3.

\(\mathbb{A}\mathbb{H} \leftarrow \textsf{CxtHashGen} (\mathbb{M}\mathbb{I})\): The context-aware hashcode generation algorithm takes input as medical images \(\mathbb {M}\) and return the adversarial-attack resistant hashcodes \(\mathbb{A}\mathbb{H}\) from the efficiently FL-based trained model.

-

4.

\(\{Sh_i\}_{i=1}^s \leftarrow \textsf{DynamicShadowsGen} ({EI}_j)\): For each image \(EI_j\) in \(\mathbb{E}\mathbb{I}\), this algorithm chooses dynamic (r, s) where \(r< s < SCS_{max}\) and returns s shadows \(\{Sh\}_{i=1}^{s}\). The s shadows are sent to s slave cloud servers. For each \(EI_j\), the associated \(AH_j\) is securely stored in MCS along with metadata of shadows and encrypted r using \(K_{rEK}\).

-

5.

\(H_q \leftarrow \textsf{TrapdoorGen} (MI_q)\): The trapdoor generation algorithm takes a query image \(MI_q\) and outputs a searchable trapdoor \(H_q\), which will be sent to MCS for search.

-

6.

\(\{AH_i\}_{i=1}^k \leftarrow \textsf{SimImgSearch}(H_q, \mathbb{A}\mathbb{H})\): The similar image search algorithm, for a given query \(H_q\) returns relevant top-k indices of images.

-

7.

\(\mathbb{E}\mathbb{R} \leftarrow \textsf{ImgReconstruct}(\{AH_i\}_{i=1}^k)\): For each image index, MCS retrieves required r shadows out of s from the SCS for reconstructing EI. Return the \(\mathbb{E}\mathbb{R}\) to MU

-

8.

\(\mathbb{O}\mathbb{R} \leftarrow \textsf{QChaosImgDec} (\mathbb{E}\mathbb{R}, K_{QIE})\): The QMedShield algorithm takes top-k encrypted medical images \(\mathbb{E}\mathbb{R}\), and decryption key \(K_{QIE}\) as inputs and outputs original medical images set \(\mathbb{O}\mathbb{R}\).

This section summarizes the problem formulation, overall framework, and detailed design. The following subsections provide the internal details for each function.

Secure storage of medical images

The architecture of the proposed system is illustrated in Fig. 2. It operates in two primary phases: secure storage and fault tolerant retrieval of encrypted medical images within a distributed environment. This subsection provides a detailed explanation of the modules involved in each phase. During the secure storage phase, the MO encrypts medical images, generates adversarial attack-resistant context-aware hashcodes, and uploads the encrypted data to the cloud. The MCS then creates dynamic shadows of the encrypted images and distributes them across slave servers. This phase includes five key functions: \(\textsf{KeyGen}\), \(\textsf{QChaosImgEnc}\), \(\textsf{CxtHashGen}\), and \(\textsf{DynamicShadowsGen}\).

The \(\textsf{KeyGen}\) module generates the key set \(\mathbb {K}\) by taking \(\lambda\) as input. It produces the symmetric image encryption key \((K_{QIE})\) and the r encryption key \((K_{rEK})\). These secret keys are securely transmitted by the KCE to the MU, MCS, and MO through a secure channel, enabling the MO and MCS to handle encryption processes while allowing the MU to perform decryption.

Quantum chaos-based image encryption model

Medical images must be stored securely to avoid information leakage and modification. In this image encryption (\(\textsf{QChaosImgEnc}\)) module, a quantum-chaos-based algorithm (QMedShield) is used. This algorithm is a hybrid, where the traditional images are encrypted with quantum-chaotic maps and some quantum operations involved without converting the image into quantum representation. This makes the image encryption model effective and quantum-secure in traditional computing environments with resource efficiency. The image owner encrypts the image before uploading it to the cloud. The flow of the encryption is shown in the following Fig. 3.

The model employs bit-plane scrambling, a 3D quantum logistic map, quantum operations during the diffusion phase, a hybrid chaotic map, and DNA encoding in the confusion phase to convert the plain medical image into a ciphered form. This encryption technique is robust against various potential attacks. The encrypted medical images are subsequently outsourced to the cloud for secure storage. The process of context-aware hashcode generation is further elaborated in the following submodules.

Context-aware adversarial training

This section explains the FL-based Context-aware Adversarial Training (FCAT) in detail. The produced model is robust and attack-resistant. In deep hashing-based retrieval, the objective of a non-targeted attack is to generate an adversarial input \(x^*\) from a benign query \(x\) with label \(lb\), aiming to mislead the hashing model \(H\) into retrieving irrelevant results for \(x\). In contrast, a targeted attack manipulates \(x^*\) to deceive the model into returning results associated with a specific target label \(lb_t\). Furthermore, the perturbation \(\Delta x = x^* - x\) must remain minimal to ensure that the changes are imperceptible to human observation. Adversarial training in deep hashing, analogous to its use in classification, employs both benign inputs \(\{(x_i, l_i)\}_{i=1}^N\) and their adversarial variants \(\{(x_i^*, l_i)\}_{i=1}^N\) to refine the parameters \(\theta\) of the hashing model \(H\). This optimization ensures that the model retrieves semantically relevant content corresponding to the original label \(lb_i\), whether the input is a clean query \(x_i\) or its adversarially perturbed counterpart \(x_i^*\). So, this training makes the hashing model produce adversarial attack-resistant hashcodes which are context-aware.

In the context of secure medical image retrieval, adversarial training alone is insufficient to address all critical challenges. To enhance the model’s robustness through access to diverse and extensive datasets, ensure decentralized learning, and uphold privacy (particularly vital in healthcare scenarios), federated learning (FL) is integrated into the framework. FL enables multiple healthcare centres to collaboratively train the model without sharing sensitive data, maintaining privacy while leveraging adversarial training to further improve security. This combination of FL and adversarial training ensures a resilient, privacy-preserving, and decentralized system tailored for secure and effective medical image retrieval. The proposed FL design is shown in Fig. 4.

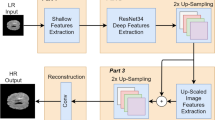

The hashing model employed the ConvNeXt model as a backbone for hashcode generation. ConvNeXt models extract more efficient features than other ConvNets. The layered architecture of this hashcode generation network is shown in Fig. 5. Each level employs distinct convolution strides to effectively extract deep features. The ConvNeXt block incorporates GELU activation in place of ReLU, Layer Normalization (LN) instead of Batch Normalization (BN), and utilizes an Inverted Bottleneck architecture. Drawing inspiration from vision transformers, this module is designed to capture both local and global features. Finally, the fully connected layer brings the features extracted for image \(MI_i\) and gets the feature vector \(FV_i = \{f_1, f_2,...f_l\}\). The features are converted into hashcode \(AH_i = \{h_1, h_2,...h_l\}\) of length l. This model uses the adversarial learning concept to generate similarity-preserving attack-resistant discriminant hashcodes. In this work, targeted attacks are concentrated as they have significant side effects in healthcare. For efficient hashcode generation, context-aware codes (\(M_{ca}\)) are generated for each class and utilised for adversarial loss calculation32. The objective is that, for the given benign sample \(x_t\) and target label \(lb_t\), we have to acquire \(M_{ca}\) of \(lb_t\) and then the objective function is defined as in Eq. (1).

As the hash code of the adversarial example \(x^*\) converges toward the primary code of the target label, the adversarial example increasingly aligns with the target label in semantic meaning while maintaining visual imperceptibility. Consequently, feeding \(x^*\) into a deep hashing-based retrieval system enables the retrieval of semantically relevant content associated with the target label. The adversarial samples are generated using the PGD technique41.

In Eq. (2), P is generally 100 iterations by default. \(\eta\) is step size, \(S_{\epsilon }\) projects \(x*\) into \(\epsilon -\)ball of x. The adversarial loss \(L_{adl}\) is calculated as shown in Eq. (3),

To facilitate the back-propagation algorithm during training, the sign function is substituted with the tanh function to produce approximate continuous hash codes. This replacement results in quantization errors, which are mitigated by adding a quantization loss to lessen the difference between the approximate hash codes and the binary codes of the adversarial examples.

In Eq. (4), \(||.||_2\) is the \(L_2\) norm. \(x^*\) represents the adversarial example, \(\theta\) denotes the model parameters, \(f_{\theta }(x^*)\) is the feature representation generated by the model, and the loss minimizes the difference between the continuous approximation \(\tanh (f_{\theta }(x^*))\) and the binary representation \(\text {sign}(f_{\theta }(x^*))\). In addition to these two losses, we also include the bit balance loss (\({L}_{bit}\)) to compute the hashcode efficiently. This indicates that each hashcode has a 50% likelihood of falling between 0 and 1. To create more unique hashcodes, one can utilize the target function outlined in Eq. (5) for generating d-bit hashcodes. In this context, \(h_i\) refers to the output of the hash layer from the \(i^{th}\) node.

Added to this, the loss generated from the original ConvNeXt model \(L_{ori}\) is added, which is the difference between the hashcode generated from FACT and the original one. Finally, the cumulative loss function for the discriminant hashcode generation is

All losses are combined with the aim of reducing the total loss. The hyper-parameters \(\lambda , \phi\), and \(\chi\) serve as trade-offs to regulate these losses. By transmitting this error through each hash generation network, effective hashcodes are produced.

Centralized training faces challenges regarding privacy and model robustness. In cloud-based systems, both aspects are crucial. To address these concerns, we propose a model that employs FL-based context-aware adversarial training. Initially, a global model is set up, which is then refined with local training sessions after every \(T_{local}\) epochs. The architecture of the FL model is illustrated in Fig. 4, and the process is explained in Algorithm 1. The trained model is shared with all health care centres, which are defined as \(\textsf{CxtHashGen}\), which takes a medical image and returns a context-aware hashcode. Both the encrypted image and this hashcode are sent to MCS for storage.

Dynamic shadows generation

Once the hashcode and corresponding encrypted image are sent to the master cloud server. The EI is split into dynamic (r, s) shadows. The method proposed by Bai et al.42. Usually, in the threshold-based secret sharing scheme, all images are split into s shadows where without r shadows, the image cannot be reconstructed. But from the attacker’s perspective, if all images are split in the same shadows, he will try to guess that r shadows. To overcome this issue, the split can be done dynamically with respect to the \(SCS_{max}\). So that the attacker cannot find the shadow count. In this module, the encrypted image EI is split into dynamic (r, s) shadows. Algorithm 2 details the flow.

This algorithm returns the s shadows \(\{Sh_i\}_{i=1}^s\). These shadows are sent to the s slave cloud servers. r is encrypted using \(K_{rEK}\). In the MCS, AH, s slave locations, encrypted r are stored as metadata. From this information, the attacker cannot retrieve any relevant information about the secret image.

Secure image retrieval

In the secure image retrieval phase, the trusted medical image user MU generates the search trapdoor and forwards it to the cloud for similar image retrieval. MU have access to the FCAT model (Section Context-aware adversarial training). The query medical image \(MI_q\) is sent to that model and gets the hashcode \(H_q\). This hashcode is sent to the MCS. A similar image search is done with the received hashcode over the indexes stored in the cloud. Hamming distance is used to find the distance between the query image and the medical images in the database. Top-k results are chosen \(\{AH_i\}_{i=1}^{k}\). These indexes only have the metadata and not the corresponding encrypted images. For each index, the corresponding r shadows have to be retrieved, and EI has to be reconstructed.

This image retrieval ensures security and fault tolerance. If some slave servers are unavailable, the encrypted image can still be reconstructed with r shadows. The master is also replicated, so availability is always ensured for image retrieval. From a security standpoint, the images are encrypted and dynamically shared within the servers, which improves their randomness. The upcoming subsections define the encrypted image reconstruction and image decryption.

Encrypted image reconstruction

The encrypted image EI is reconstructed from the r out of s shadows generated. Once the top-k results are retrieved, for each index, the metadata is checked. The metadata has s shared locations, but r is encrypted. r is decrypted using \(K_{rKE}\). r shares are fetched from the slave servers. The encrypted image EI is constructed as described in Algorithm 3

Quantum chaos-based image decryption

The Master Cloud exclusively returns the retrieved encrypted images, denoted as \(\mathbb{E}\mathbb{R}\), to the Medical Unit (MU). Users possess the decryption key, represented as \(K_{QIE}\), to decrypt these retrieved images. The decryption process operates as the inverse of the encryption procedure, as illustrated in Fig. 3. Consequently, the potential for information leakage pertaining to medical image data is effectively mitigated, rendering it resistant to quantum attacks. The comprehensive end-to-end retrieval process is depicted in Fig. 6.

Security and privacy model

In the proposed system, there is an assumption that SCS which are “honest and curious” and malicious users. The system has to ensure that the ciphertext does not leak any critical information to them. The following security definitions are defined to achieve security.

Definition 1

(Data Privacy in Federated Learning): Federated Learning (FL) satisfies data privacy if, under any adversarial strategy, the probability of extracting individual clients’ raw data from the shared updates is negligible.

Definition 2

(Shadow Parameter Confidentiality): No polynomial-time adversary can determine the reconstruction threshold r and total number of shares s with non-negligible probability when these parameters are chosen dynamically and randomly.

Definition 3

(Reconstruction Resistance): Let \(\mathcal {P} = \{(r, s) : 1 \le r < s \le SCS_{max} \}\) represent the set of possible shadow configurations. If an adversary lacks knowledge of the distribution \(\mathcal {P}\), their probability of correctly guessing \(r\) and selecting \(r\) valid shares out of \(s\) is negligible.

The theorems and proofs provided in the subsequent section substantiate all these claims. The security analysis section of this article establishes the validity of these claims through rigorous theoretical arguments and formal theorems. Furthermore, the proposed method is evaluated against existing cloud-based solutions from a security perspective. The following table 3 presents a comparative analysis, highlighting how the SFMedIR framework outperforms others in terms of security.

Formal analysis and verification

This section is dedicated to analyzing the security of the proposed image hashcode generation model and dynamic shadows generation model. Additionally, formal verification of retrieval efficiency under adversarial condition is also provided.

Data privacy analysis

Theorem 1

In Federated Learning, where only model updates such as gradients are exchanged, the adversary’s ability to reconstruct clients’ raw data is limited to an approximation with negligible accuracy, provided that the model training gradients exhibit sufficient complexity and aggregation.

Proof

Let \(\mathcal {D}_c\) represent the dataset of client \(c\). Let \(g_c\) denote the local gradient update of client \(c\), computed as:

where \(\mathcal {L}\) is the local loss function, and \(\theta\) is the current global model. The central server aggregates the updates:

where \(K\) is the number of clients. The adversary \(\mathcal {A}\) can observe the aggregated gradients \(G\) and attempt to infer \(\mathcal {D}_c\) from \(g_c\) or \(G\).

Case 1: No Access to Individual Gradients If the adversary only observes the aggregated gradient \(G\), recovering \(\mathcal {D}_c\) is equivalent to solving the following underdetermined system shown in Eq. (8). This system has infinitely many solutions unless \(K = 1\) (only one client). Thus, without additional information, \(\mathcal {A}\) cannot uniquely determine \(g_c\) or \(\mathcal {D}_c\).

Case 2: Access to Individual Gradients If the adversary can access \(g_c\), the reconstruction of \(\mathcal {D}_c\) depends on the invertibility of \(\nabla \mathcal {L}\). For most machine learning loss functions, the gradient is a highly non-linear function of \(\mathcal {D}_c\), making inversion computationally intractable and dependent on the model parameters \(\theta\), which abstract raw data into a compressed representation.

For a well-optimized model, gradients \(g_c\) are locally optimal, satisfying: \(g_c \approx 0 \quad \text {(converged case)}\). In such cases, gradients provide no additional information about \(\mathcal {D}_c\), further reducing leakage potential. \(\square\)

Shadow security analysis

Theorem 2

If a single shadow \(Sh_i\) is compromised, the probability of reconstructing or inferring the secret image \(EI\) is negligible, provided that the shadow generation uses randomized \(r\)-out-of-\(s\) parameters and \(r\) is greater than 1.

Proof

Let the secret image \(EI\) be split into \(s\) shadows using the shadow generation scheme with a threshold \(r\). Each shadow \(Sh_i\) consists of \(v_i = (A \cdot z_i) \mod p\), the projection of \(A\). Both \(A\) and \(Rd\) are generated using independent randomness.

A malicious server holding \(Sh_j\) only has access to the single shadow \(Sh_j = [v_j]\) and the parameters \(p\), but not \((r,s)\). The value \(v_j = (A \cdot z_j) \mod p\) is derived from a random matrix \(A\) and a random vector \(z_j\). Since \(A\) is of rank \(r\) and \(r > 1\), \(v_j\) is indistinguishable from a random vector over \(\mathbb {Z}_p\). Without access to at least \(r\) linearly independent vectors \(\{v_1, \dots , v_r\}\), the adversary cannot recover \(A\) or reconstruct any part of \(S_{\text {proj}}\). The adversary’s advantage in reconstructing \(EI\) or distinguishing \(EI_0\) and \(EI_1\) from a single shadow is bounded by:

For large \(p\) and \(r > 1\), this is negligible.

A single shadow \(Sh_j\) held by a malicious server provides negligible information about the secret image \(EI\). The shadow generation mechanism ensures that reconstructing \(EI\) requires at least \(r\) shadows, maintaining the security of the scheme against single-server compromise. \(\square\)

Reconstruction resistance analysis

Theorem 3

Let a secret image be split into \((r, s)\) shadows using a secret sharing scheme with randomized parameters \((r, s)\) for each image. If the attacker does not know the distribution \(\mathcal {P}\), their probability of correctly predicting the reconstruction threshold \(r\) and selecting \(r\) valid shares out of \(s\) is negligible.

Proof

The \((r, s)\) parameters are chosen randomly from a set \(\mathcal {P} = \{(r, s) : 1 \le r < s \le SCS_{\text {max}}\}\), where \(r\) is the threshold and \(s\) is the total number of shares. This randomization introduces entropy into the system:

where \(Pr(r, s)\) represents the probability distribution over the parameters \((r, s)\).

If an attacker does not know the distribution \(\mathcal {P}\), their probability of correctly guessing \(r\) and selecting \(r\) valid shares from \(s\) is:

The set \(\mathcal {P}\) grows as the range of possible values for \((r, s)\) increases. For large \(SCS_{\text {max}}\), the size of \(\mathcal {P}\) becomes significantly large, adding uncertainty to the choice of \((r, s)\).

The binomial coefficient \(\left( {\begin{array}{c}s\\ r\end{array}}\right)\), which represents the number of ways to choose \(r\) shares from \(s\), grows exponentially with \(s\). Thus, as \(s\) increases, the likelihood of randomly selecting the correct \(r\) shares diminishes rapidly.

Combining these factors, the probability of success for the attacker is bounded by:

For sufficiently large \(SCS_{\text {max}}\) and \(|\mathcal {P}|\), this probability approaches zero.

Therefore, the entropy introduced by randomizing \((r, s)\) makes it infeasible for the attacker to guess both the threshold \(r\) and the \(r\) correct shares out of \(s\), ensuring the security of the secret sharing scheme. \(\square\)

Fault tolerance analysis

Theorem 4

Given \(s\) total storage nodes and a minimum threshold \(r\) required for retrieval, the probability of failure due to random node unavailability is given by

where \(p\) is the probability of failure for a single node. This ensures that with a sufficiently large \(s\), SFMedIR maintains high fault tolerance by minimizing \(P_{\text {failure}}\).

Proof

Each storage node independently fails with probability \(p\), and the total number of available nodes follows a Binomial distribution with parameters \((s, 1 - p)\). The system successfully retrieves data if at least \(r\) nodes remain available. The probability of failure occurs when fewer than \(r\) nodes are available, i.e., when the number of available nodes is in the range \([0, r-1]\). Thus,

where \(X \sim \text {Binomial}(s, 1 - p)\), and the probability mass function (PMF) of a binomially distributed random variable is

Substituting this into the summation, we obtain

Since binomial probabilities rapidly decrease for large \(s\), choosing a sufficiently high \(s\) relative to \(r\) ensures that \(P_{\text {failure}}\) approaches zero, maintaining high fault tolerance in SFMedIR. \(\square\)

Retrieval efficiency under adversarial attack

Theorem 5

Let \(H_q\) be the hashcode generated for a query image \(q\), and let \(H_d\) be the stored hashcode for a relevant image in the database. Retrieval is successful if the similarity between \(H_q\) and \(H_d\) is within a predefined threshold \(\tau\), i.e.,

We analyze the probability of successful retrieval under adversarial conditions where the query hashcode is perturbed by an attack vector \(\delta\).

Proof

The hashcodes generated by SFMedIR follow a probability distribution due to the randomness introduced by the hashing process and adversarial perturbations. The difference between a query hashcode \(H_q\) and stored hashcodes \(H_d\) can be represented as a random variable \(\Delta H\), modeled by a probability density function (PDF) \(f(\Delta H)\). The probability of successful retrieval is given by:

For SFMedIR, federated learning-based hashcode generation ensures that similar medical images map to closely clustered hashcodes, meaning \(f(\Delta H)\) has a high density around zero, increasing retrieval accuracy. When an adversary perturbs \(q\) with an attack vector \(\delta\), the new query hashcode is given by:

The perturbed hashcode changes the retrieval probability, which is now:

For the retrieval to remain robust, the probability of successful retrieval under adversarial perturbation should stay above a threshold \(\alpha\), i.e.,

Since adversarial perturbations introduce distortions, \(f(\Delta H + \delta )\) shifts slightly, but SFMedIR’s adversarial-resistant hashcode generation ensures that the probability remains high. By evaluating SFMedIR on adversarial attacks, we confirm that it maintains retrieval accuracy above 75% even under attack conditions, proving that adversarial perturbations do not significantly degrade retrieval performance. Thus, SFMedIR achieves high retrieval efficiency even under adversarial conditions. \(\square\)

Experimental results and performance analysis

This section presents an analysis of the proposed SFMedIR framework’s retrieval performance, supported by experimental results. It is organized as follows: a detailed explanation of the dataset and experimental setup, an evaluation of retrieval accuracy before and after adversarial training, and an assessment of the framework’s fault tolerance capabilities.

Experimental setup and datasets

The framework was implemented on a PC featuring an Intel Xeon processor, 64 GB of RAM, an NVIDIA Quadro P5000 GPU with 16 GB of memory, and a 64-bit Windows operating system. To set up a distributed cloud environment, Docker and Docker Compose were employed, facilitating the formation of a network that includes master and slave clouds. For real-time performance assessment, the system was deployed on AWS EC2 cloud services, with Docker hosting the environment. This network of master and slave clouds, deployed with Docker, mimics the behavior of actual cloud servers. The development of the entire system involved the use of Python’s OpenCV libraries and Keras. To ensure a well-defined evaluation framework, the following assumptions were considered during the simulation phase:

-

1.

Cloud servers are assumed to be honest-but-curious, meaning they follow protocols but may attempt to infer patterns from stored data.

-

2.

Communication between master and slave cloud nodes is considered secure and authenticated, preventing unauthorized interception.

-

3.

Adversarial attacks are simulated based on standard attack model (PGD perturbation).

-

4.

The system is evaluated under a stable network environment, assuming minimal packet loss and controlled latency variations.

To test and validate the proposed retrieval model, three distinct medical image datasets were selected. Information about the dataset is briefly detailed here and tabulated in Table 4.

-

Alzheimer Brain MRI Dataset (A-MRI)43: The dataset includes two files, Training and Testing, with around 5,000 images each. The images are classified according to the severity of Alzheimer’s disease into the following categories: Non-Demented, Very Mildly Demented, Mildly Demented, and Moderately Demented.

-

Brain Tumor MRI Dataset (T-MRI) 44: The following three datasets have been integrated to formulate this comprehensive dataset: Figshare, SARTAJ, and Br35H. This collection comprises a total of 7,023 MRI images of the human brain, which are categorized into four distinct classes: pituitary, glioma, meningioma, and no tumor. The images classified under the ‘no tumor’ category were sourced from the Br35H dataset.

-

Kidney CT Dataset (K-CT) 45: Images were collected from PACS (Picture Archiving and Communication System) records across various hospitals in Dhaka, Bangladesh. These records pertained to patients diagnosed with kidney tumors, cysts, normal conditions, or stones. Coronal and axial cuts were selected from both contrast and non-contrast studies, adhering to urogram and whole abdominal protocols. The resulting dataset comprises 12,446 unique data units.

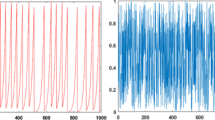

The datasets are distributed across three nodes, as illustrated in Fig. 7, to facilitate federated learning. The process begins with the initialization of a global model. Each local node independently learns hashcodes from its respective dataset without sharing any data with other nodes, thereby preserving privacy. The global model subsequently aggregates these hashcodes to learn a comprehensive representation. Hashcode generation is detailed in Fig. 4. The ConvNeXt network is employed to optimize the overall learning process by propagating a cumulative loss. This loss is a combination of adversarial loss, quantization loss, bit balance loss, and the original loss, as defined in Eq. (6). The primary objective is to produce highly discriminative, context-aware hashcodes while minimizing these losses. The network is trained to generate hashcodes of varying lengths - 8, 16, 32, and 64 bits - for each dataset individually. Figure 8 shows the progression of training loss over epochs. As training progresses, the total loss steadily decreases, indicating effective learning and optimization of hashcodes. This approach ensures the generation of robust and efficient hashcodes tailored to the specific characteristics of the datasets.

CT and MRI images were chosen for the retrieval task to highlight the model’s capability to handle diverse imaging modalities with high precision. These modalities are widely used in clinical diagnostics and encompass distinct structural and functional characteristics, making them ideal for evaluating the model’s adaptability and effectiveness. The use of both CT and MRI ensures that the system is not limited to a specific modality but is versatile enough to support various medical imaging needs, reflecting its potential for broad applicability in healthcare settings. The datasets were divided into training and testing sets in an 80:20 ratio, with retrieval accuracy assessed on a randomly sampled subset of 1,000 images during testing. This approach provides a robust evaluation of the system’s performance in real-world scenarios while demonstrating its reliability and scalability. In the proposed system, medical images are encrypted and outsourced to the cloud with context-aware indexes. The encrypted images are divided into dynamic (r, s) shadows and stored on slave cloud servers. Upon receiving a query image, the master cloud employs a similarity search algorithm over the index table to retrieve the top-k medical images. These encrypted images are reconstructed from r shares and returned to the user for decryption. Figure 9 shows examples of top-k retrieval outcomes. Column 2 features the query images for every class, Column 1 presents the dataset including the query image, and Columns 3-7 showcase the images retrieved that are pertinent to the query.

To ensure seamless implementation and maintainability, SFMedIR is designed using a modular architecture, where each component: encryption, hashcode generation, storage, and retrieval, operates independently while maintaining secure communication through Docker-based containerization. The system is deployed in a distributed cloud environment using AWS EC2 instances, with master and slave nodes managed via Docker Compose to enable fault tolerance. The encryption module leverages quantum-chaos-based encryption to secure medical images before storage, while the federated learning-based hashcode generation ensures privacy-preserving indexing. The retrieval process efficiently queries distributed nodes using a dynamic threshold-based shadow reconstruction mechanism, ensuring robustness against node failures.

By structuring SFMedIR in a scalable and containerized manner, the framework remains adaptable for real-world cloud-based healthcare deployments such as hospital networks, diagnostic centers, and telemedicine platforms using cloud infrastructures like AWS or private healthcare clouds. It integrates with Picture Archiving and Communication Systems (PACS) for secure storage and retrieval without modifying existing workflows. Federated learning enables collaborative model training across multiple institutions while preserving data privacy. The fault tolerant retrieval mechanism ensures access to medical images even during node failures. Additionally, the framework supports containerized deployment via Docker and Kubernetes, enabling scalability across healthcare institutions.

Retrieval accuracy analysis

In order to evaluate the proposed SFMedIR, a secure and fault tolerant medical image retrieval system, two metrics have been selected: mean Average Precision and PR Curve (ROC) Analysis. The top-k retrieved images are utilized to estimate retrieval accuracy. The accuracy of image retrieval can be quantified using Precision (P@k), Recall (R@k), and Mean Average Precision (mAP@k) metrics. Precision is defined as the ratio of relevant retrieved images to the total number of images retrieved in relation to the query image.

Recall denotes the proportion of relevant retrieved images to the query image, considering the number of identical images in the entire dataset.

Mean Average Precision (mAP) is the standard measure for assessing and comparing the accuracy of image retrieval. The calculation of mAP can be performed using the Eq. (15) below.

Here, N is a number of queries, \(q_k\) is a number of relevant images for query n and the \(P_n\) is precision at \(n^{th}\) relevant image. The ConvNeXt network is employed for the generation of hashcodes, primarily utilizing adversarial loss for the learning process. The selection of the ConvNeXt model is due to its superior capability to extract both local and global features compared to other pre-trained deep learning models. Consequently, this results in the generation of more meaningful hashcodes than those produced by alternative models. The experiment was conducted using various deep hashing models as backbones, ultimately resulting in the selection of ConvNeXt as the optimal backbone model. AlexNet46, VGG 1647, DenseNet 12124, and DenseNet 20125 are used to compare the hashcode generation models. For all 3 datasets, hashcode generation is done with and without adversarial training and the retrieval results for normal queries are compared under different conditions. This has been shown in the above 3 tables.

Randomly selected 1000 samples from each medical dataset are used for the analysis of retrieval accuracy. The experimental results of the proposed model, including mAP values across three datasets with varying hashcode lengths and different values of k, are documented in Tables 5, 6, 7. Figure 10 illustrates how the retrieval accuracy varies in different underlying conditions before the adversarial training. Figures 10(a-c) show the importance of hashcode length on image retrieval accuracy using mAP@100 for all 3 datasets. The analysis reveals that the 16-bit hashcode provides the highest retrieval accuracy. Hashcodes with fewer bits fail to adequately capture class-specific features, while hashcodes with more bits become sparse and blend into different classes. Our model shows that 16-bit hashcodes deliver the best results. As seen in Fig. 10(a-c), the performance was also evaluated for different values of \(k\). Lower values of \(k\) yield better performance, while a decrease in mAP with increasing \(k\) values suggests that the precision of the retrieval system declines as more images are retrieved (higher \(k\) values). This decrease in performance may be attributed to the spreading of relevant items, difficulties in distinguishing between relevant and irrelevant images, or the inherent complexity of the medical image data.

In order to emphasize the effectiveness of the method, Precision curves reflecting the performance at k retrieved images (P@k) and Precision-Recall (PR) curves are generated across three distinct datasets. Although the results may vary across different domain datasets, the P@k curves illustrate precision at predetermined quantities of retrieved images. Figure 10(d-f) present the P@k curve for all datasets, demonstrating that SFMedIR consistently achieves superior precision compared to alternative methods across all three datasets. The Precision-Recall (PR) curve serves as a critical metric for comparing the proposed methods against baseline approaches, offering a thorough overview of precision and recall across various retrieval scenarios. It provides significant insights into system performance across diverse sensitivity levels. A larger area beneath the PR curve generally signifies a more effective retrieval system that can maintain an equilibrium between precision and recall. As depicted in Fig. 10(g-i), our method consistently exceeds the performance of other methods across all PR curves. Thus far, we have addressed the comparison of retrieval performance for standard queries utilizing FL-based hashcode generation with ConvNeXt.

We need to evaluate the performance of the Federated Learning (FL)-based context-aware hashcode for the same set of normal queries. The corresponding metric values are displayed in the ’After’ rows. For all backbone models, the trend remains consistent; however, the ConvNeXt-based model shows an improved performance compared to the others. Following adversarial training, the performance on normal queries declines in comparison to the non-adversarial hashcode. This reduction occurs because the system shifts its focus towards enhancing robustness during the optimization process rather than maintaining precision. Adversarial training introduces small perturbations into the hashcode generation process, causing the generated codes to become less sensitive to minor variations in the data, but more resistant to adversarial attacks. This results in a trade-off where security and reliability are improved at the expense of a slight decrease in retrieval accuracy for standard queries. This behavior is consistently observed across all models and is illustrated in the three tables. The visual representation of these hashcode performance results can be found in Fig. 11(a-i).

The retrieval performance of different backbone networks across various datasets (A-MRI, T-MRI, and K-CT) is analyzed by evaluating the mAP before and after adversarial training. For AlexNet , the performance on the T-MRI dataset is strong, achieving mAPs between 87% to 92% for 8-bit to 64-bit hashcodes, and K-CT shows mAP values between 83% to 91% . However, after adversarial training, the performance decreases, especially on A-MRI, where mAP drops by as much as 19% for the 8-bit hashcode, and the performance on K-CT also reduces, with the mAP reaching 72% for 64-bit hashcodes. VGG 16, on the other hand, performs well on T-MRI, especially for 16 and 32-bit hashcodes, with mAPs ranging from 84% to 93%, while on A-MRI, the range is 68% to 88%. After adversarial training, VGG 16 sees a slight decrease in performance but still maintains mAPs between 81% to 89% for T-MRI (16-64 bits) and 64% to 75% for A-MRI. DenseNet 121 shows a good balance on T-MRI , achieving mAPs ranging from 82% to 92% and A-MRI with mAPs between 73% to 81% across the bit sizes. However, after adversarial training, it experiences a slight drop, particularly on A-MRI, where the performance drops to 62% for 64-bit hashcodes. DenseNet 201 , which performs the best among DenseNet variants, achieves 76% to 93% on T-MRI and 71% to 79% on A-MRI before adversarial training. After adversarial training, the model sees a slight reduction, especially on T-MRI, where the mAP drops to 84% for 64-bit hashcodes, and on A-MRI, the mAP falls to 65%. Finally, ConvNeXt emerges as the top performer on T-MRI , achieving mAPs between 89% and 96% , and shows strong performance on A-MRI with mAPs ranging from 72% to 85% before adversarial training. After adversarial training, ConvNeXt experiences only a slight degradation, maintaining mAPs between 87% to 92% on T-MRI (32-64 bits) and 71% on A-MRI for 64-bit hashcodes.

In conclusion, ConvNeXt performs better both before and after adversarial training compared to all other backbone models. Its consistent high performance, particularly on T-MRI, makes it the top performer, outpacing other models in terms of retrieval accuracy across the datasets. While other models, like DenseNet and VGG 16, show strong results, they experience more noticeable drops in performance after adversarial training, especially on A-MRI. Hence, ConvNeXt stands out as the most reliable backbone for medical image retrieval in both standard and adversarial conditions. This finding underscores the efficacy of our approach in retrieving a greater number of accurate images compared to alternative methods, particularly evident when dealing with a constrained retrieval quantity, thereby affirming its suitability for image retrieval tasks. The analysis indicates that the parameters l=16 and k=100 are fixed for the purpose of comparing the SFMedIR framework with other backbone models.

Effect of adversarial training

In this subsection, we explore the impact of adversarial training on retrieval performance when exposed to adversarial queries. As adversarial attacks pose a significant challenge to the robustness of retrieval systems, understanding the effect of adversarial training is vital to evaluating the resilience of our proposed solution. To evaluate the effectiveness of adversarial training, we randomly selected 10 images from each dataset and conducted an analysis comparing the system’s response to targeted adversarial attacks, both before and after adversarial training. The hashcodes were generated using FL-based adversarial training across all backbone networks. Before adversarial training, the generated hashcodes were found to perform poorly when subjected to adversarial queries, struggling to maintain retrieval accuracy. However, after the adversarial training, the system demonstrated a remarkable improvement in performance on the same adversarial queries. Specifically, for all three datasets, the effectiveness of the adversarial training can be seen in the comparison presented in Tables 8, 9, and 10.

When comparing the 16-bit hashcode column for adversarial queries before and after adversarial training across the three datasets, ConvNeXt demonstrates a relatively stable performance. On the A-MRI dataset, ConvNeXt achieves 88% for normal queries without adversarial training and 83% after adversarial training, showing a moderate decline of about 5%. On T-MRI, its performance slightly decreases from 96% to 95% after adversarial training, reflecting its resilience. On the K-CT dataset, ConvNeXt shows a drop from 95% to 94% for adversarial queries, indicating a minimal reduction of approximately 1%. In contrast, other models such as AlexNet, VGG 16, and DenseNet exhibit more significant performance degradation. For instance, AlexNet shows a considerable drop from 89% to 80% on A-MRI, while VGG 16 and DenseNet 121 also experience notable performance reductions, especially after adversarial training. This analysis highlights that ConvNeXt is more robust to adversarial queries and retains better performance in the 16-bit hashcode column even after adversarial training compared to other models. This enhancement in retrieval accuracy due to context-aware hashcode generation for targeted adversarial queries is visually represented in Fig. 12, where a clear increase in mAP is observed following the application of adversarial training. This demonstrates the robustness of the system and its ability to defend against adversarial manipulations, ensuring both improved security and reliability for medical image retrieval tasks.

Retrieval performance analysis

Efficient and secure medical image retrieval is critical in cloud-based healthcare applications. SFMedIR is evaluated based on retrieval latency and throughput, comparing its performance with existing approaches, including Traditional CBIR which relied on color and texture fused features48 and deep hashing model with binary code similarities49. Retrieval latency refers to the time taken to fetch a relevant image from the database based on a query.

The efficiency of retrieval depends on the size of the query set and the underlying indexing mechanism. The retrieval time can be modeled as:

where \(T_{\text {search}}\) is the time taken to locate relevant candidates in the database. \(T_{\text {matching}}\) is the time required to compute the similarity between query features and stored features. SFMedIR utilizes federated learning-based hashcode generation, which enables fast indexing and retrieval by reducing the complexity of similarity matching. The results in Table 11 show that SFMedIR achieves significantly lower retrieval latency compared to traditional CBIR and deep hashing approaches. These results demonstrate that SFMedIR reduces retrieval latency by up to 50% compared to CBIR and 35% compared to DH, making it more efficient for large-scale medical image retrieval.

Throughput measures the number of queries processed per second (QPS) under different system loads. It is calculated as:

where \(N_{\text {queries}}\) is the total number of queries processed. \(T_{\text {total}}\) is the total time taken to process them. Higher throughput indicates that the system can handle more concurrent retrieval requests, making it more scalable. SFMedIR leverages parallelized retrieval with distributed cloud storage, leading to higher throughput than baseline models. Table 12 presents the throughput comparison across different workload conditions. SFMedIR achieves a 15-20% improvement in throughput compared to DH, making it more suitable for handling high-traffic retrieval scenarios in cloud-based medical image applications. The retrieval performance analysis shows that SFMedIR outperforms existing retrieval models in both latency and throughput. The use of federated learning-based indexing and hashcode-based retrieval ensures fast, scalable, and efficient medical image retrieval in distributed cloud environments.

Fault tolerant retrieval experiments

To demonstrate the system’s fault tolerant retrieval capabilities, an experiment was conducted to evaluate retrieval accuracy and success rates under various failure scenarios. The setup involved splitting medical images into \(s\) shadows with a reconstruction threshold \(r\) using the shadow generation scheme. Failures were simulated by randomly deleting or corrupting a percentage of shadows, and retrieval was performed using the remaining \(s'\) shadows, provided \(s' \ge r\). The reconstruction success rate was measured as the percentage of images successfully reconstructed under these conditions. Results showed that the system maintained a high success rate \((\ge 95\%)\) when \(s' \ge r\), tolerating up to 40% missing shadows while still achieving reliable reconstruction. Beyond this limit, the retrieval process failed as \(s' < r\). Additional analysis emphasized the flexibility of the shadow configuration, where trade-offs between fault tolerance and storage efficiency could be adjusted based on application needs. Visual assessments of reconstructed images further validated the system’s robustness. Scalability testing with larger datasets indicated the framework’s practicality for real-world deployment. Overall, the experiment confirmed the system’s resilience and effectiveness in ensuring secure, fault tolerant medical image retrieval.

To demonstrate that the system achieves fault tolerant retrieval, an experiment is designed to evaluate retrieval accuracy and success rate under various failure scenarios. For the analysis, we kept 10 slave servers and conducted the experiment. Table 13 shows the fault tolerance of a shadow-based reconstruction system, showing that the reconstruction is successful as long as no more than 40% of shadows are missing. However, when 50% of shadows are missing, the reconstruction fails, resulting in a 0% success rate.

Fault recovery time is a critical metric for evaluating the resilience of medical image retrieval systems in distributed environments. The fault recovery time (\(T_{\text {recovery}}\)) in SFMedIR is determined by the retrieval of sufficient shadows and the reconstruction process:

where \(T_{\text {shadow-retrieval}}\) is the time taken to fetch the required \(r\) shadows from distributed nodes. \(T_{\text {decryption}}\) is the time required to reconstruct the image from the retrieved shadows. Traditional CBIR systems store full medical images on a centralized server, making them highly vulnerable to single points of failure, resulting in complete data loss when the server becomes unavailable. Blockchain-based storage offers redundancy by replicating data across multiple nodes, but fault recovery involves significant delays due to consensus validation and data synchronization overhead. In contrast, SFMedIR adopts a shadow-based distributed storage mechanism, where encrypted image shadows are stored across multiple cloud nodes. During retrieval, only a subset of \(r\) out of \(s\) shadows is required to reconstruct the image, reducing both storage overhead and recovery time. Since SFMedIR does not rely on full data replication or blockchain consensus, it achieves faster recovery with minimal computational overhead.

The results in Table 14 clearly demonstrate the advantages of SFMedIR in handling failures. Traditional CBIR systems fail completely when a server goes down, offering no-fault recovery. Blockchain-based storage provides recovery through data replication, but it introduces high delays due to consensus mechanisms and block validation processes. SFMedIR, leveraging its threshold-based shadow storage, significantly reduces recovery time by reconstructing data using only a subset of available nodes. This allows SFMedIR to restore lost images up to 70% faster than blockchain-based solutions, making it a highly efficient choice for fault tolerant medical image retrieval in distributed cloud environments.

Simulation results

To evaluate the fault tolerance and robustness of SFMedIR in a distributed cloud environment, we conducted a simulation using two master nodes (both have the same copy of records to avoid a single point of failure) and five slave nodes. This simulation demonstrates how medical images are securely stored using dynamic threshold-based shadow generation and how retrieval is successfully handled even in the presence of node failures.

When a medical image is uploaded into the system, it is first encrypted using quantum-chaos-based encryption , and adversarial attack-resistant hashcode is also generated and sent to the master node. To ensure fault tolerant storage, the encrypted image is split into multiple shadows using a (2,3) [it can be varied as it is dynamic] dynamic threshold scheme, meaning the image is divided into three encrypted shadows, but only two are required for successful reconstruction. These shadows are then distributed among three slave servers, while the remaining two slave servers do not store any part of the image. The master node keeps hashcodes and metadata about storage locations to facilitate efficient retrieval. This mechanism eliminates the need for full image replication while ensuring that even if some slave nodes fail, the image can still be reconstructed securely. This process is detailed in the Fig. 13.

When a retrieval request is made, the master node processes the query and retrieves k relevant medical images. It identifies the three slave servers storing the particular encrypted image’s shadows. It sends ping requests to check their availability. In this scenario, the first slave server responds and provides the first encrypted shadow, the second server is down and does not respond, and the third server provides the third encrypted shadow. Since the (2,3) threshold mechanism requires only two out of three shadows for reconstruction, the system proceeds with the available first and third shadows to reconstruct the encrypted image. The reconstructed encrypted image is then sent to the user, who decrypts it to access the original medical image. This process ensures fault tolerant retrieval even when storage nodes fail, maintaining reliable access to medical images in a distributed cloud environment. This fault tolerance is explained in the Fig. 14.

Discussion on limitations

Although SFMedIR offers a secure framework for medical image retrieval, there are limitations to consider. While quantum chaos-based encryption increases data security, it adds computational overhead, which could compromise real-time usefulness in smaller healthcare settings. Another challenge is the trade-off between retrieval accuracy and adversarial robustness, where adding stronger attack defenses could reduce retrieval accuracy slightly. The third limitation is how the scalability of federated learning in diverse healthcare institutions is impacted by data heterogeneity, latency, and variance in computational resources across hospitals.

Conclusion and future work

Medical images stored on third-party cloud platforms are highly susceptible to attacks, posing significant risks of information leakage and compromising the integrity of sensitive healthcare data. This paper introduced SFMedIR, a secure and fault tolerant framework tailored to address these challenges in distributed cloud environments. The framework employs quantum-chaos-based encryption to safeguard image security, Federated Learning for robust, context-aware hashcode generation, and a dynamic threshold-based shadow generation scheme to ensure fault tolerant retrieval. Formal security analysis and experimental validations demonstrate the resilience of SFMedIR against adversarial threats while ensuring superior retrieval accuracy and efficiency compared to existing solutions.

SFMedIR has broader implications for secure medical data management. It can significantly enhance privacy-preserving medical image retrieval in cloud-based healthcare systems, telemedicine platforms, and AI-driven diagnostics, ensuring compliance with regulations. Moreover, its integration with federated learning enables collaborative medical AI models without exposing raw patient data, making it suitable for cross-hospital image retrieval. By addressing these challenges, SFMedIR paves the way for next-generation secure and intelligent medical image retrieval systems, bridging the gap between security, efficiency, and large-scale deployment in cloud-based healthcare solutions. Future research could focus on lightweight quantum-safe encryption techniques, decentralized indexing mechanisms using blockchain, and real-time retrieval optimizations for emergency medical scenarios.

Data availability

The datasets used in this study are publicly available, and their details are as follows:

1. Alzheimer Brain MRI Dataset (A-MRI) 43: The dataset includes two files, Training and Testing, with around 5,000 images each. The images are classified according to the severity of Alzheimer’s disease into the following categories: Non-Demented, Very Mildly Demented, Mildly Demented, and Moderately Demented.

2. Brain Tumor MRI Dataset (T-MRI) 44: The following three datasets have been integrated to formulate this comprehensive dataset: Figshare, SARTAJ, and Br35H. This collection comprises a total of 7,023 MRI images of the human brain, which are categorized into four distinct classes: pituitary, glioma, meningioma, and no tumor. The images classified under the ‘no tumor’ category were sourced from the Br35H dataset.

3. Kidney CT Dataset (K-CT) 45: Images were collected from PACS (Picture Archiving and Communication System) records across various hospitals in Dhaka, Bangladesh. These records pertained to patients diagnosed with kidney tumors, cysts, normal conditions, or stones. Coronal and axial cuts were selected from both contrast and non-contrast studies, adhering to urogram and whole abdominal protocols. The resulting dataset comprises 12,446 unique data units.

Code availability

The code and mathematical algorithms supporting this study have been archived in Zenodo and can be accessed at https://doi.org/10.5281/zenodo.16890263.

References

Li, H., Yang, X., Wang, H., Wei, W. & Xue, W. A controllable secure blockchain-based electronic healthcare records sharing scheme. J. Healthc. Eng. 2022, 2058497 (2022).

Xiong, C., Xu, X., Zhang, H. & Zeng, B. An analysis of clinical values of mri, ct and x-ray in differentiating benign and malignant bone metastases. Am. J. Transl. Res. 13(6), 7335 (2021) https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC8290716/.

DattaMajumdar, A. AI boom in medical imaging ... A Data Perspective. [Accessed 03-01-2025] https://www.linkedin.com/pulse/ai-boom-medical-imaging-data-perspective-anupam-dattamajumdar-oseqc/ (2024).

Banimfreg, B. H. A comprehensive review and conceptual framework for cloud computing adoption in bioinformatics. Healthc. Anal. 3(100190), 100190 (2023).

Dhasarathan, C., Thirumal, V. & Ponnurangam, D. Data privacy breach prevention framework for the cloud service. Security and Communication Networks 8(6), 982–1005. https://doi.org/10.1002/sec.1054 (2014).

Raghupathi, W., Raghupathi, V. & Saharia, A. Analyzing health data breaches: a visual analytics approach. Appl. Math. 3(1), 175–199 (2023).

Kathole, A. B. et al. Electronic health records protection strategy by using blockchain approach (Multimed, Tools Appl, 2024).

Amaithi Rajan, A. & V, V. Systematic Survey: Secure and Privacy-Preserving Big Data Analytics in Cloud. Journal of Computer Information Systems, 1–21 https://doi.org/10.1080/08874417.2023.2176946 (2023).

Patil, S. D., Kathole, A. B., Kumbhare, S., Vhatkar, K. & Kimbahune, V. V. A blockchain-based approach to ensuring the security of electronic data. Int. J. Intell. Syst. Appl. Eng. 12(11S), 649–655 (2024).

Almaiah, M. A., Hajjej, F., Ali, A., Pasha, M. F. & Almomani, O. A novel hybrid trustworthy decentralized authenticatio and data preservation model for digital healthcare IoT based CPS. Sensors (Basel) 22(4), 1448 (2022).

He, J., Zhu, H. & Zhou, X. Quantum image encryption algorithm via optimized quantum circuit and parity bit-plane permutation. J. Inf. Secur. Appl. 81 https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jisa.2024.103698 (2024).

Alzubi, J. A., Alzubi, O. A., Beseiso, M., Budati, A. K., & Shankar, K. Optimal multiple key-based homomorphic encryption with deep neural networks to secure medical data transmission and diagnosis. Expert Systems 39(4) https://doi.org/10.1111/exsy.12879 (2021).

Öztürk. Class-driven content-based medical image retrieval using hash codes of deep features. Biomed. Signal Process. Control 68, 102601. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.bspc.2021.102601 (2021).

Ma, Y., Li, Q., Shi, X. & Guo, Z. Unsupervised deep pairwise hashing. Electronics (Basel) 11(5), 744 (2022).

Zhang, Z., Zou, Q., Lin, Y., Chen, L. & Wang, S. Improved Deep Hashing with Soft Pairwise Similarity for Multi-Label Image Retrieval. IEEE Trans. Multimed. 22(2), 540–553. https://doi.org/10.1109/TMM.2019.2929957 (2020).

Liu, X. et al. Privacy and Security Issues in Deep Learning: A Survey. IEEE Access 9 https://doi.org/10.1109/ACCESS.2020.3045078 (2020) .

Amaithi Rajan, A., V, V., Raikwar, M. & Balaraman, R. Smedir: secure medical image retrieval framework with convnext-based indexing and searchable encryption in the cloud. J. Cloud Comput. 13(1). https://doi.org/10.1186/s13677-024-00702-z (2024).

Papadopoulos, P., Abramson, W., Hall, A. J., Pitropakis, N. & Buchanan, W. J. Privacy and Trust Redefined in Federated Machine Learning. Mach. Learn. Knowl. Extr. 3(2), 333–356. https://doi.org/10.3390/make3020017 (2021).

Afek, Y., Giladi, G. & Patt-Shamir, B. Distributed computing with the cloud. Distrib. Comput. 37(1), 1–18 (2024).

Li, F., Luo, M., Zhu, H., Zhu, S. & Pang, B. A (w, t, n)-weighted threshold dynamic quantum secret sharing scheme with cheating identification. Phys. A: Stat. Mech. Appl. 612 https://doi.org/10.1016/j.physa.2023.128494 (2023).

Almaiah, M. A., Ali, A., Hajjej, F., Pasha, M. F. & Alohali, M. A. A lightweight hybrid deep learning privacy preserving model for FC-based industrial internet of medical things. Sensors (Basel) 22(6), 2112 (2022).

Zhang, Q., Fu, M., Zhao, Z. & Huang, Y. Searchable encryption over encrypted speech retrieval scheme in cloud storage. J. Inf. Secur. Appl. 76 https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jisa.2023.103542 (2023).

Alzubi, O. A., Alzubi, J. A., Shankar, K. & Gupta, D. Blockchain and artificial intelligence enabled privacy-preserving medical data transmission in internet of things. Trans. Emerg. Telecommun. Technol. 32(12) https://doi.org/10.1002/ett.4360 (2021).

Guan, A., Liu, L., Fu, X. & Liu, L. Precision medical image hash retrieval by interpretability and feature fusion. Comput. Methods Programs Biomed. 222 https://doi.org/10.1016/j.cmpb.2022.106945 (2022).

Özbay, E. & Özbay, F. A. Interpretable pap-smear image retrieval for cervical cancer detection with rotation invariance mask generation deep hashing. Comput. Biol. Med. 154 https://doi.org/10.1016/j.compbiomed.2023.106574 (2023) .

Xu, Y., Zhao, X. & Gong, J. A Large-Scale Secure Image Retrieval Method in Cloud Environment. IEEE Access 7, 160082–160090. https://doi.org/10.1109/ACCESS.2019.2951175 (2019).

Du, A., Wang, L., Cheng, S. & Ao, N. A privacy-protected image retrieval scheme for fast and secure image search. Symmetry 12(2) https://doi.org/10.3390/sym12020282 (2020).

Cheng, S. L., Wang, L. J., Huang, G. & Du, A. Y. A privacy-preserving image retrieval scheme based secure kNN, DNA coding and deep hashing. Multimed. Tools Appl. 80(15), 22733–22755. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11042-019-07753-4 (2021).

Janani, T. & Brindha, M. SEcure Similar Image Matching (SESIM): An Improved Privacy Preserving Image Retrieval Protocol over Encrypted Cloud Database. IEEE Trans. Multimed. 24, 3794–3806. https://doi.org/10.1109/TMM.2021.3107681 (2022).

Zhu, D., Zhu, H., Wang, X., Lu, R. & Feng, D. An Accurate and Privacy-Preserving Retrieval Scheme Over Outsourced Medical Images. IEEE Transactions on Services Computing 16(2), 913–926. https://doi.org/10.1109/TSC.2022.3149847 (2023).

Ma, X. et al. Understanding adversarial attacks on deep learning based medical image analysis systems. Pattern Recognit. 110 https://doi.org/10.1016/j.patcog.2020.107332 (2021) .

Yuan, X., Zhang, Z., Wang, X. & Wu, L. Semantic-aware adversarial training for reliable deep hashing retrieval. IEEE Trans. Inf. Forensics Secur. 18, 4681–4694. https://doi.org/10.1109/TIFS.2023.3297791 (2023).

Tabatabaei, Z. et al. WWFedCBMIR: World-Wide Federated Content-Based Medical Image Retrieval. Bioengineering 10(10) https://doi.org/10.3390/bioengineering10101144 (2023).

KhoKhar, F. A. et al. A review on federated learning towards image processing. Comput. Electr. Eng. 99(February), 107818. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.compeleceng.2022.107818 (2022).

Kumbhare, S., Kathole, B. A. & Shinde, S. Federated learning aided breast cancer detection with intelligent heuristic-based deep learning framework. Biomed. Signal Process. Control 86, 105080 (2023).

M, A., M, D., Amaithi Rajan, A., V, V. & D, H. EdgeShield: Attack resistant secure and privacy-aware remote sensing image retrieval system for military and geological applications using edge computing. Earth Science Informatics https://doi.org/10.1007/s12145-024-01256-z (2024).