Abstract

This study aims to optimize the ceramic-to-backing thickness ratio (Rth) of B4C/UHMWPE composite armor to enhance the anti-penetration performance while maintaining lightweight requirements. Its primary innovation lies in systematically quantifying, through combined finite element method (FEM) and ballistic testing, the coupling mechanism of thickness ratio (Rth: 0.4-2.0), areal density (AD: 25.0–30.0 kg/m²), and impact velocity (V0: 400.0–550.0 m/s) governing the anti-penetration performance of composite armor. The results reveal that the ballistic limit velocity (Vbl) initially increases and then decreases as Rth increases from 0.4 to 2.0, peaking at Rth = 1.4–1.6 across all AD cases. Notably, this optimal Rth range remains consistent across AD variations, with both projectile mass loss ratio (RIIm,l) and kinetic energy loss ratio (RIIke,l) during the first two penetration stages peaking within this range, demonstrating robust design applicability. Furthermore, a key finding and significant contribution is the dynamic shift in the optimal Rth for minimizing projectile residual velocity (Vre) when V0 exceeds Vbl: Under fixed AD, higher V0 reduces the optimal Rth due to shortened projectile-armor interaction time, necessitating thicker UHMWPE laminate to prevent premature ceramic fracture failure and enhance the backing-plate energy dissipation. Conversely, under constant V₀, higher AD elevates the optimal Rth, where AD and V₀ show opposite effects on the variation of optimal Rth, and the optimal Rth converges to 1.4–1.6 as the highest Vbl corresponding to given AD approaches V0. Critically, this study establishes a quantitative framework for V0-AD-Rth coupling effects, providing actionable guidelines for designing lightweight composite armor against diverse ballistic threats.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

With the continuous development of material technology and its extensive application in the military field, the conflict between armor-piercing ammunition and armor protection technology has become increasingly intense1,2. Compared to the previous homogeneous armor and metal armor, ceramic composite armor tends to exhibit higher ballistic protection efficiency3. Modern military platforms, such as armored vehicles, helicopters, and personal protection equipment, demand lightweight composite armor to meet NATO STANAG 4569 Level 3 ballistic and blast protection while ensuring mobility, such armor systems typically exhibit an areal density (AD, armor mass per unit area) range of 35.0 to 120.0 kg/m²4,5. Due to the exceptional protective performance of ceramic composite armor, scholars have systematically investigated its unique ballistic mechanism6, and explored the effects of ceramic panel layer7, and backing layer8, and projectile impact parameters, such as impact velocity9 and obliquity angle10, on the ballistic performance of composite armor. Typically, ceramic composite armor consists of a high-hardness ceramic panel and a high-toughness backplane, and its anti-penetration performance is influenced by many factors, including ceramic panel thickness, backplane thickness, constraint condition and so on11. Boron carbide (B4C) ceramic stands out among bulletproof ceramic materials due to its exceptional characteristics. It possesses the lowest density and highest hardness when compared to other ceramics such as alumina (Al2O3) and silicon carbide (SiC). Moreover, it holds significant research value and exhibits promising applications in the field of bulletproof inserts and lightweight composite armor7. Ultrahigh molecular weight polyethylene (UHMWPE) laminate, a type of fiber reinforced polymer (FRP) laminate, is fabricated by stacking and hot-pressing multiple layers of UHMWPE fiber monolayers. Compared to metal backplane, it exhibits superior specific modulus, specific strength, fracture toughness, and anti-penetration performance. Owing to these advantages, UHMWPE laminate is widely applied in aerospace, defense, and ocean engineering, emerging as a prominent research hotspot in the protective engineering field12,13,14. Hence, it is essential to investigate and evaluate the anti-penetration performance of composite armor comprising B4C ceramic panel and UHMWPE laminate to enhance its protective performance and quality protective efficiency.

Experimental testing remains a cornerstone methodology used to investigate the anti-penetration performance of composite armor. This method can provide accurate and intuitive results, whereas its high cost and time-intensive nature limit application scope. In contrast, numerical method has the advantage of low cost and comprehensive data, researchers are increasingly using the numerical method to supplement and extend the ballistic testing results15,16,17. In the ballistic testing against 7.62 mm projectiles, Den Reijer18 observed that high-hardness ceramic panels effectively fragment and decelerate projectiles, while metal backplanes provide support to prevent premature ceramic panel failure, maximizing its effectiveness in fragmenting the projectiles. Separately, Cao et al.19 investigated the damage mechanisms of ceramic composite armor against 12.7 mm armor-piercing projectiles, and found that boundary constraint conditions, backplate structural configuration have significant influence on the ballistic performance. Yu et al.20 conducted ballistic testing on ceramic/metal composite armors with different thicknesses configurations using 12.7 mm projectiles, the results indicate that increasing the backplane thickness enlarged both the half-cone angle and fracture dimension of ceramic cones, while thicker ceramic panels maintained a stable half-cone angle but reduced the overall crushing size. However, neither of the above studies have quantitatively investigated the influence of structural configuration on the ballistic performance of composite armor.

There have been numerous papers exploring the anti-penetration performance under various structural configurations. Hu et al.21 proposed a multilayer composite armor system (metal/ceramic/UHMWPE laminate) to investigate its ballistic performance against flat-nosed projectiles. Their studies revealed that the multilayer armor systems exhibit multiple failure modes. With the optimization of structural configuration, the projectile residual velocity (Vre) decreased, and the energy absorption effect of armor system improved significantly. Braga et al.22 introduced a multilayered armor system comprising alumina ceramic panel, curaua fabric-reinforced composite, and aluminum alloy backplane to investigate the effect of layer thickness/areal density on the anti-penetration performance. The results revealed that aluminum alloy layer exhibits higher efficiency rather than other layers in terms of trauma absorption, and the armor system with optimized structural configurations achieved a significant thickness reduction while maintaining ballistic performance. Wang et al.23 proposed a layered ceramic composite armor (B4C/C/UHMWPE), and conducted ballistic testing using 7.62 mm projectiles. Their numerical simulations revealed that the composite armor exhibits the optimal bulletproof performance at a B4C panel thickness of 10 mm. The above three studies primarily focus on leveraging the synergistic effects of multi-layered composite armor materials to enhance energy dissipation mechanisms, while the effect of different material layer thickness ratios on ballistic performance is not mentioned.

Si et al.24 found that when the thickness ratio between the front ceramic panel and metal backplane (Rth) is 1:2, the projectile remains at the interface for a longer residence time, resulting in a relatively high ballistic protection efficiency. Chang et al.25 studied the anti-penetration performance of lightweight ceramic/aluminum alloy composite armor under various thickness configurations, and they found that the composite armor exhibits optimal bulletproof performance at an Rth value of 4:1 between ceramic panel and aluminum alloy. Li et al.26 utilized the FEM to simulate the penetration process of 12.7 mm projectiles into composite armor. The numerical results revealed that bulletproof performance increased with increasing component thickness, whereas the bulletproof performance initially increases and then decreases as the Rth value rises. The above studies explored the anti-penetration performance of ceramic composite armor under various material and thickness configurations; however, there are still some issues that need to be further investigated. Specifically, few papers have simultaneously investigated the combined effects of Rth, AD and projectile impact velocity (V0) on the anti-penetration performance of composite armor. Even with the same thickness configuration, the composite armor may exhibit different ballistic behavior. The ceramic composite armor demonstrates distinct damage characteristics at different V0 and AD conditions, and the variations of V₀ and AD significantly alter penetration resistance. Therefore, it is necessary to investigate the influence of Rth on the anti-penetration performance of composite armor under different V0 and AD conditions.

In this paper, a composite armor system comprising B4C ceramic and UHMWPE laminate with varying thickness configurations is investigated. The ballistic behavior and anti-penetration performance of composite armor system are simulated and evaluated using numerical calculation methods, and ballistic testing is conducted on B4C/UHMWPE composite targets against 7.62 mm steel-core projectiles. Specifically, this study focuses on the influence of Rth on the anti-penetration performance and damage characteristics, and it also discusses and analyzes the influence of V0 and AD on the optimal Rth of composite armor system. This research provides a certain basis for the future structural design and thickness optimization, contributing to enhancing the protective performance of lightweight ceramic composite armor and expanding its application prospects.

Ballistic testing and finite element modeling description

Projectile and target specification

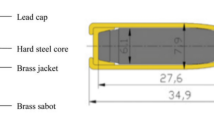

In this study, the projectile is composed of mild steel core (B2F steel), lead cover and copper-clad steel jacket, as shown in Fig. 1 (a). The projectile has a length of 32.00 mm and a weight of 9.60 g, while the mild steel core measures 23.60 mm in length and weighs 4.75 g. To improve the mesh quality and computational efficiency of the finite element (FE) model, the sharp corners of projectile components are simplified, and the simplified FE model is shown in Fig. 1 (b).

As depicted in Fig. 2 (a), the B4C/UHMWPE composite armor has a lateral dimension of 300 × 300 mm. The B4C ceramic panel is prepared through a hot-press sintering process and supplied by Dalian Jinma Boron Group Co., Ltd. The UHMWPE laminate is prepared in the laboratory using a fiber stacking method of \(\:0/{90}^{^\circ\:}/0/{90}^{^\circ\:}\), followed by a hot-pressing process. The two components are bonded together using rubber-modified epoxy resin. The densities of B4C ceramic and UHMWPE laminate are 2.5 × 103 kg/m3 and 0.98 × 103 kg/m3, respectively. The AD value of composite armor can be calculated by summing the products of the densities and thicknesses for different armor components. In the ballistic testing, the AD of B4C /UHMWPE composite targets is 25.0 kg/m2, and the FE model of composite target is shown in Fig. 2 (b).

Ballistic testing method

In this study, the ballistic testing is conducted to evaluate the anti-penetration performance of B4C/UHMWPE composite target. The ballistic testing system consists of a ballistic gun, aluminum foil targets, a time interval tester, a target holder, a high-speed camera (sample rate of 3200 fps), a scale and other components. The layout diagram of testing site is shown in Fig. 3, and some images of testing facilities are presented in Fig. 4.

Specifically, 7.62 × 54 mm steel-core projectiles are fired from a fixed ballistic gun, with different impact velocities obtained by adjusting the propellant charge of the cartridge. A combination of aluminum foil targets, placed directly in front of the testing targets, and a time interval tester is employed to measure the projectile impact velocity. The distance between the aluminum foil targets and the ceramic composite target is approximately 1.5 m. The velocity measured by the above measuring facilities can be considered as the V0 value. A high-speed camera are applied to record the penetration process. Meanwhile, when the testing facility positions are fixed, each pixel in the image captured by the high-speed camera represents an identical distance. The high-speed camera image and the scale are used to determine the Vre value in cases where the composite targets are completely penetrated.

The FE model comprises three main components: projectile, B4C ceramic panel and UHMWPE laminate. Projectiles with initial velocity V0 vertically impact the B4C/UHMWPE composite armour system. In addition, the structural parameters of both projectiles and composite armors are consistent with those obtained from ballistic testing.

Material constitutive model

Among the available material constitutive models, Johnson-Cook (J-C) model is particularly suitable for materials that undergo significant variations in strain rates and experience material softening due to adiabatic temperature increases caused by plastic heating27,28. In the present FE model, the J-C model is utilized to describe the ballistic response behavior of three projectile components. The J-C strength model is generally represented by:

The J-C damage model is represented by:

where D is the accumulated damage factor, and fracture occurs when D reaches 1. \(\:\varDelta\:{\stackrel{-}{\varepsilon\:}}_{p}\) is the incremental equivalent plastic strain during each integration cycle, while \(\:{\varepsilon\:}^{f}\)refers to the equivalent fracture strain, which is defined as:

where D 1, D 2, D 3, D 4 and D 5 represent the failure parameters, and the J-C model is comprehensively described in Ref27. Based on experimental quasi-static and dynamic compressive/tensile mechanical properties, some scholars have fitted to obtain the J-C model parameters for the above projectile components, as presented in Tables 1 and 229,30,31,32.

where \(\:{\sigma\:}_{i}^{*}\) and \(\:{\sigma\:}_{f}^{*}\) represent the intact and damaged behaviors, respectively. \(\:{D}_{0}\) refers to the accumulated damage factor (0≤ \(\:{D}_{0}\) ≤1). The above strength parameters are given by:

where A0, B0, N0, C0 and M0 are the input strength parameters. \(\:{p}^{*}\) and \(\:{t}^{*}\) are the hydrostatic pressure and maximum tensile pressure strength normalized by the Hugoniot elastic limit pressure component (\(\:{p}_{HEL}\)):

In the above equation, the plastic strain to fracture is given by:

where d1 and d2 are the fracture plastic strain parameters.

The hydrostatic pressure is expressed as:

where K1, K2 and K3 are input pressure coefficients. µ refers to the compressibility factor (µ = ρ/ρ0 -1). The main parameters of B4C ceramic panel are listed in Table 334.

The composite damage model (MAT_COMOSITE_FAILURE_SOLID_MODEL) is applied to describe the dynamic response behavior of UHMWPE laminate under the impact of projectiles. This material model includes the orthotropic elastoplastic strength model and failure criterion, and the failure criterion includes: tensile and compression failure of the fiber, tensile and compression failure of the matrix. A detailed description of the above model is in Ref35. In order to prevent some instabilities, additional failure criteria are applied to delete failure elements with excessive plastic strain. Table 4 provides the main parameters of UHMWPE laminate35]– [36.

Finite element algorithm description

This subsection focuses on the mesh topology, contact formulation, and boundary conditions of the FE model. Lagrangian formulation is applied to discretize projectiles and composite targets, necessitating the definition of contacts between different components within this FE model. Specifically, all material domains are discretized using eight-node hexahedral elements (SOLID 164). The surface-to-surface erosion contact algorithm is utilized to model the interaction between projectiles and targets. Secondly, the automatic contact algorithm is utilized to capture the interfacial interaction among different projectile components. Finally, the tie contact with failure criteria is utilized to model the interaction at the initial contact interface of different target components, and contact failure will occur once the following failure criteria are met:

where \(\:{\sigma\:}_{n}\) is the current normal stress, and \(\:{\sigma\:}_{s}\) refers to the current shear stress. NFLS is the normal failure stress, and SFLS refers to the shear failure stress. According to the previous research, when using the rubber-modified epoxy resin for interfacial bonding, the values of NFLS and SFLS are set to 43.0 MPa and 25.0 MPa, respectively37.

The boundary conditions in this ballistic testing system and the FE model are consistent. The ceramic composite target in the ballistic testing system is fixed to the target holder, which means that the freedom of ceramic composite target edges is constrained in all directions. A quarter FE model is generated to numerically describe the penetration process to enhance the computational efficiency. This model is symmetric about the XOY plane and the XOZ plane, as shown in Fig. 2 (b), and thus all nodes in the XOY and XOZ symmetry planes are imposed with translation and rotation constraints along the Z-axis and the Y-axis, respectively.

Mesh size sensitivity analysis

The damage behavior of materials is primarily achieved by removing elements that satisfy the failure criteria, However, it should be noted that this approach limits the ability to observe post-failure mechanisms of ceramic and fiber composites. Additionly, inappropriate mesh sizes cannot accurately represent the deformation and failure behavior of the material. The mesh sizes of both projectiles and targets affect the accuracy of the numerical simulation results. Therefore, it is necessary to conduct a convergence analysis for the penetration process.

In this FE model, projectiles with the same V0 are used to vertically impact composite targets with the same structure. Specifically, the V0 value is set to 432.0 m/s, and the thickness configuration of B4C/UHMWPE ceramic composite targets is 8.0 mm + 5.0 mm. To maintain the accuracy and stability of simulation calculation, it is critical to ensure similar mesh sizes at the projectile/target contact interface. Ballistic testing results from Ref38,39 indicate that ceramic panel and projectile fragment sizes are predominantly in the range of 0.10–1.0 mm, According to the verification and validation methodology prescribed in Ref40. , convergence verification was performed using four geometrically refined meshes with a constant refinement ratio of 2.0: 1.0, 0.50, 0.25, and 0.125 mm.

Table 5 details the values of V0, Vre and computational time for different mesh sizes. The simulation results show that the Vre values differ significantly when mesh sizes are 0.25 mm, 0.5 mm and 1.0 mm. In contrast, the Vre values are similar for mesh sizes of 0.125 mm and 0.25 mm. The results indicate that the simulation results have limited dependency when the mesh size is below 0.25 mm, and the computation time increases dramatically at this level. To balance the simulation accuracy and computational efficiency, the impact center region is meshed using a 0.25 mm size, while a 1.0 mm size is used for regions farther away from the impact center region. The FE model after meshing is shown in Fig. 5.

Validation of finite element method (FEM)

Ballistic testing results

The B4C/UHMWPE composite targets utilized in this ballistic testing have an AD of 25.0 kg/m2.These targets have two different thickness configurations. “Target A” comprises an 8.0 mm B4C ceramic panel and a 5.0 mm UHMWPE laminate, while “Target B” comprises a 6.0 mm B4C ceramic panel and a 10.0 mm UHMWPE laminate. The high-speed camera records several moments of the projectile penetrating Target A at 432.0 m/s, as shown in Fig. 6. The image obtained from the high-speed camera clearly shows that the target is impacted vertically by the projectile. The ballistic testing results for Target A and Target B are presented in Table 6, mainly including the penetration results, peojectile impact velocity (V0), and residual velocity (Vre).

FEM accuracy analysis

In this study, extensive numerical calculations are performed to evaluate the ballistic performance of B4C/UHMWPE composite targets, it is necessary to verify the validity of numerical calculation method firstly. The FE model needs to maintain the same initial conditions as the ballistic testing. Specifically, the projectiles in the FE model have the same V0 as those used in the ballistic testing, and the composite targets in the FE model have the same thickness configurations as Target A and Target B in the ballistic testing (described in Sect. 3.1). The penetration results of numerical calculations are also presented in Table 6. For both Target A and Target B, simulated penetration results and Vre values are in good agreement with ballistic testing results. Moreover, the Vre errors between ballistic testing and numerical calculations are within 3.8% when the projectiles completely penetrate ceramic composite targets.

When the projectiles fails to completely penetrate the composite armor, the bulge height of UHMWPE laminate increases gradually as the V0 rises. Fragments of broken projectile and ceramic panel are not fully recycled. Both Target A and Target B are not completely penetrated when the two targets are struck by projectiles with impact velocities of 408.0 m/s and 384.0 m/s, respectively. The accuracy of numerical method can be verified by comparing the bulge height error in the ballistic testing and numerical simulations at the same V0. Table 7 presents the bulge heights of UHMWPE laminates for both Target A and Target B. In Fig. 7, the bulge heights of UHMWPE laminates for Target A are 7.31 mm and 6.90 mm in ballistic testing and simulation, respectively. For Target B, the bulge heights in ballistic testing and simulation are 5.40 mm and 5.10 mm, respectively, as shown in Fig. 8. In general, the discrepancy in bulge heights between ballistic testing and simulation for both targets does not exceed 5.60%. Overall, Target A exhibits similar anti-penetration performance in ballistic testing and numerical simulation, as does Target B.

The FEM framework used in this study, while validated for the global ballistic parameters, has inherent limitations in simulating post-failure behavior. The JH-2 model (for B₄C ceramic) and the composite damage model (for UHMWPE laminate ) use element deletion to simulate material failure, preventing numerical instability but limiting the modeling of post-fragmentation effects such as secondary fragment interactions, debris friction, and the fine-scale flow of pulverized ceramic. Additionally, constitutive models based on the continuum assumptions approximate material responses phenomenologically and cannot resolve micro-fracture mechanisms. Although the above mesh sensitivity analysis confirmed the convergence of global ballistic parameters, local damage morphology remains influenced by element size. Despite these limitations, they primarily affect detailed failure visualization rather than core conclusions. Experimental validation confirms that the FEM can reliably predict the optimal ceramic-to-backing thickness ratio (Rth) and anti-penetration performance under varying V0 and AD conditions. Here, the ballistic limit velocity (Vbl) is generally applied to quantitatively evaluate the anti-penetration performance of a protective structure against a given threat.

Results and discussion

The aforementioned numerical simulation method is utilized to investigate the combined effect of Rth (between B4C ceramic panel and UHMWPE laminate), V0 and AD values on the anti-penetration performance.

Influence of R th on the V bl

Existing research demonstrates that higher areal density (AD) can enhance the anti-penetration performance of composite armor, but increases weight and cost. Optimizing the thickness configuration without altering materials or AD can also further improve its anti-penetration performance10,41. The AD range of 25.0–30.0 kg/m² based on standard requirements and practical limits of lightweight armor design4,5,10, and this Rth range of 0.4-2.0 balances comprehensiveness with realistic design limits and provides a robust parameter space for our investigation24,25. The FEM was employed to calculate the Vbl of B4C/UHMWPE composite targets with various Rth values, where Vbl is defined as the minimum velocity required for a projectile to completely penetrate a target plate with a 50% probability. This paper focuses on composite armor with moderate-to-low AD values. The AD range is selected as 25.0–30.0 kg/m² for systematic investigation, and the Rth ranges from 0.4 to 2.0 with an interval of 0.2.

Figure 9 illustrates the relationship between Vbl and Rth for B4C/UHMWPE composite targets. The Vbl exhibits a non-monotonic dependence on Rth values. For an AD of 25.0 kg/m2, Vbl increases gradually as Rth ranges from 0.4 to 1.4, pesks at Rth = 1.4–1.6, and then decreases as Rth further rises from 1.6 to 2.0. To further determine the optimal Rth corresponding to the highest Vbl, additional calculations at Rth = 1.3 and 1.5 reveal that the highest Vbl is 420.0 m/s at Rth = 1.5. Likewise, for the AD of 30.0 kg/m2, Vbl increases gradually as the Rth ranges from 0.4 to 1.5, and followed by a decrease as the Rth further ranges from 1.5 to 2.0. Overall, considering the two aforementioned ADs, the optimal Rth range for achieving the highest Vbl is 1.4–1.6. Compared to the results of previous studies, Si et al.24 found that a SiC ceramic/4340 steel composite armor achieved the highest Vbl when the Rth was 2.0 (with a total thickness of 30.0 mm). Lu et al.41 reported that an Al₂O₃ ceramic/UHMWPE laminate exhibited optimal energy dissipation performance at an Rth of 1.25, and that the thickness of front layer significantly influences the optimal Rth. Different ceramic/backing combinations require distinct optimal configurations. This study investigates B₄C panel (hardest monolithic ceramic) paired with UHMWPE laminate (highest specific strength) based on ballistic mechanisms, addressing prior limitations in AD control. Our findings reveal an optimal B₄C/UHMWPE Rth of 1.4–1.6 at medium-to-low AD ranges (25.0–30.0 kg/m2), demonstrating superior application potential.

The penetration process and damage characteristics are investigated using a B4C/UHMWPE composite target with (AD = 25.0 kg/m², Rth = 1.5), and the V0 is 420.0 m/s, which corresponds to the Vbl value. Figure 10 shows the effective strain distribution of the projectile and target at several critical moments during the penetration process (0-140 µs). In addition, Fig. 11 quantifies the temporal evolution curve of the projectile residual mass ratio (Rm = residual mass / initial mass) and projectile residual kinetic energy ratio (Rke = residual kinetic energy / initial kinetic energy). The penetration process into composite targets is briefly divided into three stages: 0–60 µs, 60–100 µs, and 100–140 µs. In the first stage (Stage I, 0–60 µs), projectile impacts ceramic panel, and the resulting compressive stress waves are propagated toward the projectile and ceramic panel, respectively. The projectile begins to fracture and erode, and the ceramic panel backside develops axial and radial cracks under the action of reflected tensile wave, preliminary forming a fractured ceramic cone, while the UHMWPE backplane exhibits only minor deformation. After Stage I, the Rm and Rke values are measured at 61.3% and 27.6%, respectively, along with measurable losses of projectile mass and velocity. During the second stage (Stage II, 60–100 µs), the projectile continues penetrating the ceramic panel until the ceramic cone zone was completely perforated. Meanwhile, the UHMWPE laminate undergoes substantial flexural and tensile deformation induced by both fragmented projectiles and ceramic fragments. Until 100 µs, the Rm and Rke values remains only 49.0% and 6.5%. In the final stage (Stage III, 100–140 µs), the fragmented projectile and ceramic fragments continues to penetrate UHMWPE laminate until the Rke is reduced to zero. Notably, the projectile exhibits a mass loss ratio of 2.5% and a kinetic energy loss ratio of 6.5%, much lower than the 51.0% and 93.5% ratios in Stages I-II. During the penetration process, the ceramic panel predominantly dissipates projectile kinetic through fragmentation and erosive wear mechanisms in Stages I-II, effectively reducing the projectile mass and velocity, thereby establishing a dual energy-attenuation pathway. Meanwhile, the UHMWPE laminate servs as a support structure to protect the ceramic panel in Stages I-II, and transforms to absorb the projectile residual kinetic energy in Stage III.

For composite targets with Rth values of 0.6, 1.0, 1.4, 1.6, and 2.0, the Vbl values are 385.0, 395.0, 410.0, 415.0, 375.0 m/s, respectively. Each composite target was subjected to projectile impact at its corresponding Vbl value. The effective strain of projectiles and composite targets after the penetration was simulated for each Rth condition, as shown in Fig. 12. The corresponding curves in Fig. 13 depict the projectile mass loss ratio during the Stages I-II (RIIm,l), the projectile mass loss ratio during the third penetration (RIIIm,l), and the projectile kinetic energy loss ratio during the Stages I-II (RIIke,l). The projectile-target interaction time refers to the duration of contact between projectile and target components, during which the projectile kinetic energy is converted into stress waves, thermal energy and so on, culminating in fracture failure of ceramic panel.

The RIIm,l and RIIke,l values increase gradually as Rth ranges from 0.6 to 1.4, peak when Rth reaches 1.4–1.6, and then decrease gradually Rth continues to rise from 1.6 to 2.0. When Rth is below 1.4, increasing the ceramic panel thickness prolongs projectile-target interaction time, which enhances the crushing and erosive effect on the projectile. For the case of V₀ < Vbl, the projectile remains in interaction with ceramic panel for a relatively longer duration, allowing cracks to expand in a quasi-static manner. This process generates characteristic conical crack patterns while dissipating most of the projectile’s kinetic energy through crack formation and frictional sliding along fracture surfaces, demonstrating the ceramic layer’s primary role in energy absorption. As a result, the final residual projectile length progressively decreases. Additionally, UHMWPE laminate within the corresponding thickness range effectively supports the ceramic panel while absorbing the projectile residual kinetic energy. When Rth is within the range of 1.4–1.6, the ceramic cone is fully developed, with both axial and radial cracks propagating extensively throughout the ceramic cone region. This crack propagation mechanism maximized the dissipation of projectile kinetic energy during the penetration process. Notably, the formation process of ceramic cone constitutes the primary energy dissipation stage throughout the penetration process. As Rth continues to rise from 1.6 to 2.0, the UHMWPE laminate progressively becomes insufficient to support and protect the ceramic panel, and crack propagation in the ceramic cone region is limited, resulting in the decline of RIIm,l and RIIke,l values. Figure 13 shows that the projectile mass loss ratio (RIIIm,l) remains largely unchanged with increased UHMWPE laminate thickness, but decreases with reduced ceramic panel thickness. Overall, the projectile final mass loss ratio (RTm,l=RIIm,l + RIIIm,l) first increased and then decreased as Rth ranges from 0.6 to 2.0. A similar rise-fall trend is observed for the projectile length loss ratio, as shown in Fig. 12. Therefore, within the optimal Rth range (1.4–1.6), adequate projectile-target interaction time facilitates controlled crack propagation in the ceramic cone region, thereby enhancing the RIIm,l and RIIke,l values. The ceramic-dominated energy dissipation mechanism in Stages I-II exhibits greater efficiency than the backplate-governed Stages III, thereby increasing the anti-penetration performance (Vbl) of composite targets.

For composite targets (AD = 30.0 kg/m2) with Rth values of 0.6, 1.0, 1.4, 1.6, and 2.0, Vbl values are 475.0, 505.0, 535.0, 530.0, 500.0 m/s, respectively. Each target was subjected to projectile impact at its corresponding Vbl value. Figure 14 presents the variation curves of RIIm,l, RIIIm,l and RIIke,l with respect to Rth. Both RIIm,l and RIIke,l values unimodal distributions within the Rth range of 0.4-2.0, peaking at 1.4–1.6. Appropriately increasing the ceramic panel thickness decreases RIIIm,l but elevates the projectile total mass loss ratio (RTm,l=RIIm,l + RIIIm,l). Insufficient thickness in either ceramic panel or UHMWPE laminate (i.e., caused by Rth being too low or too high) willl reduce the RIIm,l and RIIke,l, values. Similarly, the RIIke,l value is much higher than that in Stage III (RIIIke,l= 1 − RIIke,l). The above discussion demonstrates that maintaining an optimal thickness ratio is critical for achieving synergistic protective effects, and the optimal Rth value for achieving the highest Vbl is 1.4–1.6 when the ADs are 25.0 and 30.0 kg/m2, demonstrating superior application potential.

Influence of V 0 on the optimal R th

The previous section has discussed the influence of Rth on the Vbl value of ceramic composite targets. Results reveal that optimally designed targets (Rth = 1.4–1.6) can effectively prevent projectile penetration when V₀ remains below the Vbl threshold. To extend this protective capacity to lower AD conditions, the influence of V0 (V0 > Vbl) on the optimal Rth is systematically investigated.

For composite targets with an AD of 25.0 kg/m2, projectiles at 400.0 m/s can completely penetrate composite armors within the Rth range of 0.4–1.3 and 1.6-2.0, excluding the range of 1.3–1.6. The highest Vbl value reaches 420.0 m/s at Rth = 1.5. Therefore, projectiles at 400.0, 450.0, 500.0 and 550.0 m/s are utilized to penetrate composite armors with various Rth values, ranging from 0.4 to 2.0 with an 0.1 or 0.2 increment. Figure 15 shows the projectile final residual mass ratio after the penetration (Rm = 1 − RIIm,l − RIIIm,l) at various V0 and Rth values. When V0 is set to 400.0, 450.0, 500.0 and 550.0 m/s, the maximum differences in Rm among various Rth values (0.4-2.0) are 2.3%, 0.6%, 0.9% and 0.9%, respectively. For cases where V0 exceeds Vbl, the variation of Rm relative to Rth does not exceed 0.9%. Consequently, post-penetration Vre values are utilized to evaluate the anti-penetration performance of composite armor. Lower Vre value correlate with superior anti-penetration performance at a given V0. The selected V₀ range of 400.0–550.0 m/s is both practically attainable and representative of real-world threats, ensuring that our findings are relevant for application.

As presented in Fig. 16, for composite armors with an AD of 25.0 kg/m2 under 400.0 m/s projectile impact, the Vre initially decreases and then increases as Rth varies from 0.4 to 2.0, and the optimal Rth range for achieving the lowest Vre is 1.3–1.6. Within this Rth range, projectiles at 400.0 m/s fail to completely penetrate composite armors, resulting in a Vre value of zero. When V0 increases to 450.0 m/s, 500.0 m/s and 550.0 m/s, the Vre - Rth trend persists, while and the optimal Rth ranges are revised to 1.2–1.4, 1.0-1.2 and 0.8-1.0, respectively.

For the B4C/UHMWPE composite target (AD = 25.0 kg/m2, Rth=1.6) with a Vbl of 415.0 m/s, projectile impacts were simulated at V0 values of 400.0, 450.0, 500.0, and 550.0 m/s. Figure 17 depicts the variation curves of RIIm,l, RIIIm,land RTm,l values versus V0, along with the projectile-target interaction time in Stages I-II (TIIit). For the case of V₀ > Vbl, the interaction time is drastically reduced. The fracture mode of ceramic panel shifts from the gradual quasi-static crack growth to a rapid, dynamic brittle failure mode. We observe that cracks propagate much faster and the ceramic tends to shatter and fragment under these high-rate loading conditions. Consequently, the ceramic panel’s energy dissipation decreases, shifting the optimal ceramic-to-backing thickness ratio (Rth) due to altered energy distribution mechanisms. When V0 exceeds the Vbl, the variation of RTm,l relative to V0 remains within 1.8% across the Rth range of 0.4–2.0, as depicted in Figs. 15 and 17, indicating that V0 has a minimal effect on the RTm,l under these conditions. When V0 exceeds the Vbl, the fracture mode of ceramic panel transitions from quasi-static propagation to dynamic brittle fracture, accompanied by a substantial acceleration in crack propagation speed. Concurrently, the UHMWPE laminate fails to adequately support the B4C ceramic panel and absorb the residual kinetic energy, resulting in a sharp decline in TIIit, which subsequently causes significant reductions in RIIm,l and RTm,l Figure 18 illustrates the variation of RIIke,l and RIIIke,l with respect to various V0 values. The RIIke,l values remain significantly higher than the RIIIke,l values during the penetration process. When V0 exceeds the Vbl, RIIke,ldecreases dramatically while the RIIIke,l increases significantly, again indicating that B4C ceramic panel fails to fully fragment the projectile. In this case, increasing the UHMWPE laminate thickness contributes to the kinetic energy absorption capacity in Stages I-II by extending the interaction time TIIit and the effective load-bearing area, while also enhancing residual kinetic energy dissipation in Stage III. Consequently, the optimal Rth range gradually decreases as the V0 increases.

For composite targets with an AD of 30.0 kg/m2, the highest Vbl reaches 540.0 m/s, slightly below 550.0 m/s. Projectile penetration was simulated at V0 values of at 550.0, 600.0, 650.0 and 700.0 m/s, to penetrate composite targets with various Rth values. Figure 19 presents the variation of post-penetration Vre with respect to Rth. Similar to the case of AD = 25.0 kg/m2, Vre exhibits a trend of first decreasing and then increasing across all tested V0 values, and the optimal Rth ranges are identified as follows: 1.4–1.6, 1.2–1.4, 1.1–1.3, 1.0-1.2. Under fixed ADs, the optimal Rth for minimizing the Vre decreases with increasing V0, it can also be said that the optimal Rth decreases as the Vbl-V0 differential (at optimal Rth) widens. Overall, the anti-penetration performance of composite armor dynamically correlated with Rth and V0 values. Zhang et al.42 and Wu et al.43 demonstrated that V0 significantly affects the ballistic performance of composite armor, consequently altering its optimal thickness configuration. Prakash et al.44 further revealed that impact velocity governs internal energy distribution, with enhanced energy absorption observed until reaching a critical velocity threshold. However, these studies did not quantitatively investigate velocity-dependent optimal Rths. This work systematically quantifies how V0 (exceeding Vbl) influences the optimal Rth at given areal densities and elucidates the underlying mechanisms.

Influence of AD on the optimal R th

The preceding discussion demonstrates that for ADs ranging from 25.0 to 30.0 kg/m2, the optimal Rth consistently remains within 1.4–1.6 for achieving the highest Vbl. However, the composite armor exhibits distinct failure modes and energy dissipation distribution patterns when V0 exceeds the Vbl. Notably, Vbl varies significantly with AD, necessitating research on the optimal Rth when V0 exceeds the Vbl. Simulations are conducted for three AD values: 25.0, 27.5 and 30.0 kg/m2, and V0 is set to 550.0 m/s, exceeding the Vbl across all tested AD cases. Figure 20 illustrates the correlation between Vre and Rth under different ADs. For the above ADs, the corresponding optimal Rth ranges for achieving the lowest Vre are 0.8-1.0, 1.2–1.4, and 1.4–1.6, respectively. Furthermore,, the optimal Rth increases as the AD increases when V0 exceeds the Vbl.

For the AD of 30.0 kg/m2, the highest Vbl of composite armor fluctuates between 530.0 and 540.0 m/s, slightly below 550.0 m/s. The optimal Rth range remains 1.4–1.6 for the V0 of 550.0 m/s. As the AD decreases from 30.0 to 27.5 kg/m2, the Vbl value drops significantly below 550.0 m/s. When composite armor is fully penetrated, the projectile-target interaction time decreases and the ceramic panel crack propagation accelerates, collectively reducing the projectile energy dissipation efficiency during the first two phases. For a given AD, the variation of Rm relative to Rth remains below 0.9% when V0 exceeds Vbl, while reducing the ceramic panel thickness appropriately exhibits negligible effect on both RTm,l and RIIke,l values. Within the Vbl, ceramic panel dominates projectile energy dissipation in penetration stages I-II, maintaining optimal Rth at 1.4–1.6 for the ADs of 25.0–30.0 kg/m2. When V0 exceeds Vbl, the Vbl-V0 differential (at optimal Rth) widens with AD reduction, equivalent to the increase of V0. Consequently, increasing the UHMWPE laminate thickness enhances its ability to dissipate the projectile kinetic energy, the optimal Rth range is 1.2–1.4 for the AD of 27.5 kg/m2. When the AD further decreases to 25.0 kg/m2, the optimal Rth range further decreases to 0.8-1.0. In summary, for composite armor with AD ranging from 25.0 to 30.0 kg/m2, the optimal Rth value gradually increases with increasing AD when the projectile penetrates the composite armor at the same V0 (exceeding the Vbl), and the optimal Rth converges to 1.4–1.6 as the highest Vbl of composite armor approaches V0.

Bendor et al.45 applied Florence’s model to determine the optimal configuration of two-component ceramic-faced lightweight armor against normal ballistic impacts. Fawaz et al.46 further developed this approach by integrating Florence’s model with a hybrid evolutionary algorithm for enhanced armor design optimization. Both studies showed that the Rth (corresponding to the Vbl) decreases with increasing AD, the optimal Rth obtained from the former studies showed minimal variation at 25.0–30.0 kg/m2, which aligns with our Sect. 4.1 findings. Crucially, this section further demonstrate that when V0 exceeds Vbl, the optimal Rth increases with rising AD, which is a previously unreported relationship.

Conclusions

To guide the structural optimization of composite armor with low-to-moderate ADs (25.0–30.0 kg/m2), numerical simulations of 7.62 mm steel-core projectile through B4C/UHMWPE ceramic composite target were conducted using the FEM, validated through the ballistic testing results. The influence of Rth, V0, and AD on the anti-penetration performance is systematically investigated. The following conclusions are drawn from this study:

(1) The FEM is utilized to quantify the Rm, l and Rke, l values at various penetration stages, aiming to evaluate the ballistic performance of composite armor. Simulation results exhibit a maximum deviation of 5.60% compared to the ballistic testing results.

(2) The Vbl is significantly affected by AD and Rth values.When Rth increases from 0.4 to 2.0, the Vbl initially increases and then decreases, with the optimal Rth range stabilizing at 1.4–1.6 for ADs of 25.0 and 30.0 kg/m2. Within this range, ceramic cone cracks fully propagate, with RIIm,l and RIIke,l values peaking during penetration stages I-II, establishing the optimal protection mechanism of ceramic-dominated fragmentation and backing-plate synergistic energy dissipation.

(3) When V0 exceeds Vbl, Vre initially decreases and then increases with rising Rth, and Rth shows negligible effect on the RTm,l. Furthermore, the optimal Rth for achieving the lowest Vre decreases with rising V0, indicating that a thicker backing laminate is required to compensate the shortened projectile-target interaction time and improve the RIIIke,l value.

(4) Under constant V0 conditions where V0 exceeds Vbl, the optimal Rth range increases with increasing AD, and the optimal Rth converges to 1.4–1.6 as the highest Vbl corresponding to given AD approaches V0. Specifically, at a V0 of 550.0 m/s, the optimal Rth ranges are 0.8-1.0, 1.2–1.4 and 1.4–1.6 for ADs of 25.0, 27.5 and 30.0 kg/m2, respectively.

(5) This study quantifies the V0-AD-Rth coupling effects, providing actionable guidelines for designing lightweight composite armor against diverse ballistic threats. Given the limitations of the FEM in capturing microscale damage evolution, future work may incorporate more advanced modeling approaches, such as FEM-SPH or multiscale simulation, to better resolve the underlying mechanisms of this coupling behavior. Moreover, extending the framework to include complex loading conditions, such as varying projectile calibers, oblique impact angles, and temperature effects, would further enhance its applicability and engineering relevance.

Data availability

No datasets were generated or analysed during the current study.

References

Kartikeya, K., Chouhan, H., Ram, K., Prasad, S. & Bhatnagar, N. Ballistic evaluation of steel/uhmwpe composite armor system against hardened steel core projectiles. Int. J. Impact Eng. 164, 104211. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ijimpeng.2022.104211 (2022).

Andraskar, N. D., Tiwari, G. & Goel, M. D. Impact response of ceramic structures-A review. Ceram. Int. 48, 27262–27279. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ceramint.2022.06.313 (2022).

Gour, G., Idapalapati, S., Goh, W. L. & Shi, X. Equivalent protection factor of bi-layer ceramic metal structures. Def. Technol. 18, 384–400. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.dt.2021.01.007 (2022).

Zou, Y. et al. Structures for shielding applications against ballistic impact: A review. Thin Walled Struct. 214, 112861. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.tws.2024.112861 (2025).

Tsirogiannis, E. C., Psarommatis, F., Prospathopoulos, A. & Savaidis, G. Composite armor philosophy (CAP): holistic design methodology of multi-layered composite protection systems for armored vehicles. Def. Technol. 41, 181–197. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.dt.2024.07.009 (2024).

Sherman, D. Impact failure mechanisms in alumina tiles on finite thickness support and the effect of confinement. Int. J. Impact Eng. 24, 313–328. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0734-743X(99)00147-5 (2000).

Boldin, M. S. et al. Review of ballistic performance of alumina: comparison of alumina with silicon carbide and Boron carbide. Ceram. Int. 47, 25201–25213. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ceramint.2021.06.066 (2021).

Liu, W. et al. Influence of different back laminate layers on ballistic performance of ceramic composite armor. Mater. Des. 87, 421–427. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.matdes.2015.08.024 (2015).

Qi, F., Wang, C. & Xu, W. Ballistic protection and damage mechanism of ceramic composite armor under two-dimensional pre-stressed constraints by molten metal casting. Aerosp. Sci. Technol. 159, 110021. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ast.2025.110021 (2025).

Wang, H., Wang, J., Tang, K., Chen, X. & Li, Y. Investigation on the damage mode and anti-penetration performance of B4C/UHMWPE composite targets for different incident velocities and angles. J. Phys. Conf. Ser. 1855, 012010. https://doi.org/10.1088/1742-6596/1855/1/012010 (2021).

Zhang, Y. et al. Analysis of the influence of different constraints on the ballistic performance of B4C/C/UHMWPE composite armor. Ceram. Int. 48, 26758–26771. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ceramint.2022.05.374 (2022).

Shen, Z., Hu, D., Yang, G. & Han, X. Ballistic reliability study on sic/uhmwpe composite armor against armor-piercing bullet. Compos. Struct. 213, 209–219. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.compstruct.2019.01.078 (2019).

Zhang, R. et al. Mechanism-driven analytical modelling of UHMWPE laminates under ballistic impact. Int. J. Mech. Sci. 245, 108132. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ijmecsci.2023.108132 (2023).

Cao, M., Chen, L. & Fang, Q. Numerical method of penetration resistance of ultrahigh molecular weight polyethylene laminate. Chin. J. Energetic Mater. 29, 132–140. https://doi.org/10.11943/CJEM2020212 (2021).

Scazzosi, R., Souza, S. D. B., Amico, S. C., Giglio, M. & Manes, A. Experimental and numerical evaluation of the perforation resistance of multi-layered alumina/aramid fiber ballistic shield impacted by an armor piercing projectile. Compos. B Eng. 230, 109488. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.compositesb.2021.109488 (2022).

Xie, Y., Wang, T., Wang, L., Yang, Y. & Sha, X. Numerical investigation of ballistic performance of SiC/TC4/UHMWPE composite armor against 7.62 mm AP projectile. Ceram. Int. 48, 24079–24090. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ceramint.2022.05.088 (2022).

Signetti, S., Ryu, S. & Pugno, N. M. Impact mechanics of multilayer composite armors: analytical modeling, FEM numerical simulation, and ballistic experiments. Compos. Struct. 297, 115916. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.compstruct.2022.115916 (2022).

Reijer, P. C. D. Impact on ceramic faced armour. Ph. D. Thesis, Delft University of Technology, Netherlands (1991).

Cao, J. et al. Experiments and simulations of the ballistic response of ceramic composite armors. J. Mech. Sci. Technol. 34, 2783–2793. https://doi.org/10.1007/s12206-020-0611-8 (2020).

Yu, Y. et al. Research on ceramic fragmentation behavior of lightweight ceramic/metal composite armor during vertical penetration. Explos Shock Waves. 41, 113301. https://doi.org/10.11883/bzycj-2021-0134 (2021).

Hu, P. et al. A metal/uhmwpe/sic multi-layered composite armor against ballistic impact of flat-nosed projectile. Ceram. Int. 47, 22497–22513. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ceramint.2021.04.259 (2021).

Braga, F. O., Lopes, P. H. L. M., Oliveira, M. S. & Monteiro, S. N. Thickness assessment and statistical optimization of a 3-layered armor system with ceramic front and Curaua fabric composite/aluminum alloy backing. Compos. B Eng. 166, 48–55. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.compositesb.2018.11.128 (2019). Jr.

Wang, D. et al. Experimental and numerical simulation study on anti-projectile penetration performance of ceramic/fiber composite armor. Mater. Rep. 35, 18216–18221. https://doi.org/10.11896/cldb.20070226 (2021).

Si, P., Bai, F., Liu, Y., Yan, J. & Huang, F. Ballistic performance of ceramic/metal composite armor systems with different thickness ratios. Acta Armament. 43, 2318–2329. https://doi.org/10.12382/bgxb.2021.0844 (2022).

Chang, Z., Zhao, W., Zou, G. & Sun, H. Simulation of the lightweight ceramic/aluminum alloy composite armor for optimizing component thickness ratios. Strength. Mater. 51, 11–17. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11223-019-00044-1 (2019).

Li, Y., Xu, Y., Zhang, J., Hua, P. & Zhao, X. Test and simulation of SiC ceramic/uhmwpe fiber composite structure against 12.7 mm armor piercing incendiary projectile. Acta Armament. 43, 1355–1364. https://doi.org/10.12382/bgxb.2021.0604 (2022).

Johnson, G. R. & Cook, W. H. A constitutive model and data for materials subjected to large strains, high strain rates, and high temperatures. In Proc. 7th Int. Symp. Ballist. 541–547 (1983).

Li, Y. et al. Orthogonal optimization design and experiments on explosively formed projectiles with fins. Int. J. Impact Eng. 173, 104462. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ijimpeng.2022.104462 (2023).

Guo, Z., Gao, B., Gao, Z. & Zhang, W. Dynamic constitutive relation based on J-C model of Q235 steel. Explos Shock Waves. 38, 804–810. https://doi.org/10.11883/bzycj-2016-0333 (2018).

Guo, Z., Shu, K., Gao, B. & Zhang, W. J-C model based failure criterion and verification of Q235 steel. Explos Shock Waves. 38, 1325–1332. https://doi.org/10.11883/bzycj-2017-0163 (2018).

Wen, Y., Xu, C., Wang, S. & Batra, R. C. Analysis of behind the armor ballistic trauma. J. Mech. Behav. Biomed. Mater. 45, 11–21. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jmbbm.2015.01.010 (2015).

Bao, K., Zhang, X., Tan, M., Chen, B. & Wei, H. Ballistic test and numerical simulation on penetration of a boron-carbide-ceramic composite target by a bullet. Explos Shock Waves. 39, 123102. https://doi.org/10.11883/bzycj-2018-0462 (2019).

Johnson, G. R. & Holmquist, T. J. An improved computational constitutive model for brittle materials. AIP Conf. Proc. 309, 981–984. https://doi.org/10.1063/1.46199 (1994).

Holmquist, T. J. & Johnson, G. R. Response of Boron carbide subjected to high-velocity impact. Int. J. Impact Eng. 35, 742–752. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ijimpeng.2007.08.003 (2008).

Zhao, C. et al. Dynamic response of UHMWPE plates under combined shock and fragment loading. Def. Technol. 27, 9–23. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.dt.2022.09.011 (2023).

Hazzard, M. K., Trask, R. S., Heisserer, U., Kamp, M. V. D. & Hallett, S. R. Finite element modelling of Dyneema® composites: from quasi-static rates to ballistic impact. Compos. Part. Appl. Sci. Manuf. 115, 31–45. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.compositesa.2018.09.005 (2018).

Zaera, R., Sánchez-Sáez, S., Pérez-Castellanos, J. L. & Navarro, C. Modelling of the adhesive layer in mixed ceramic/metal armours subjected to impact. Compos. Part. Appl. Sci. Manuf. 31, 823–833. https://doi.org/10.1016/S1359-835X(00)00027-0 (2000).

Yu, Y. et al. Fragmentation characteristics of 12.7 mm armor-piercing incendiary projectile and ceramic/metal composite target during penetration. Acta Armament. 43, 2307–2317. https://doi.org/10.12382/bgxb.2021.0497 (2022).

Rahbek, D. B. & Johnsen, B. Fragmentation of an armour-piercing projectile after impact on composite-covered alumina tiles. Int. J. Impact Eng. 133, 103332. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ijimpeng.2019.103332 (2019).

Oberkampf, W. L. & Trucano, T. G. Verification and validation in computational fluid dynamics. Prog Aerosp. Sci 38, 209–272. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0376-0421(02)00005-2

Lu, W. et al. Penetration resistance of Al2O3 ceramic-ultra-high molecular weight polyethylene (UHMWPE) composite armor: experimental and numerical investigations. Theoret Appl. Mech. Lett. 14, 100550. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.taml.2024.100550 (2024).

Zhang, F. et al. Biomimetic design and impact simulation of Al2O3/Al composite armor based on armadillo shell. Sci. Rep. 14, 20216. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-024-71255-z (2024).

Wu, X. et al. Numerical simulation research on steel/ceramic composite target plate structure against penetration of high-speed projectile. Vibroeng. Proced. 34, 72–76. https://doi.org/10.21595/vp.2020.21734 (2020).

Prakash, A., Fasil, M. & Anandavalli, N. Ballistic performance of optimised light weight composite armour. For Mech 12, 100216. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.finmec.2023.100216

Ben-Dor, G., Dubinsky, A. & Elperin, T. Optimization of two-component composite armor against ballistic impact. Compos. Struct. 69, 89–94. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.compstruct.2004.05.014 (2005).

Fawaz, Z., Behdinan, K. & Xu, Y. Optimum design of two-component composite armours against high-speed impact. Compos. Struct. 73, 253–262. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.compstruct.2005.01.037 (2006).

Acknowledgements

We gratefully acknowledge the support from Nanjing University of Science and Technology and China North Vehicle Research Institute.

Funding

This research was funded by the National Natural Science Foundation of China, the two grant numbers are No. 12102202 and No. 12372361.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

HF. Wang: Conceptualization, methodology, investigation, software, writing-original draft; K.Tang and JX. Wang: Conceptualization, funding acquisition, project administration, supervision, writing-review and editing; HP. Song: Resources, supervision; YB. Li and XW. Chen: Writing-review and editing, visualization, software; HX. Gong and YM. Ma: Writing-review and editing, validation.

Corresponding authors

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher’s note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if you modified the licensed material. You do not have permission under this licence to share adapted material derived from this article or parts of it. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Wang, H., Tang, K., Wang, J. et al. Thickness configuration optimization of B4C/UHMWPE composite armor under varying impact velocities and areal densities through numerical and experimental study. Sci Rep 15, 34365 (2025). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-17013-1

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-17013-1