Abstract

This study aimed to identify candidate diagnostic miRNAs from the serum of colorectal cancer (CRC) patients using Boruta, a wrapper-based feature selection technique, in combination with decision tree-based machine learning methods. We analyzed three serum miRNA expression profile datasets from the gene expression omnibus (GEO) database to identify differentially expressed miRNAs common to both cancerous and non-cancerous samples. The GSE106817 dataset, comprising 2568 miRNAs, was used to train our models. The Boruta machine learning feature selection method was applied to identify robust and significant miRNAs associated with CRC in the training cohort. Next, random forest and XGBoost models were trained using the selected miRNAs. To validate the predictive efficacy of the identified candidate miRNAs, we tested them against two independent datasets (GSE113486 and GSE113740). Finally, we performed ontology analysis and constructed a regulatory network to explore the potential links between the selected miRNAs and CRC development. The GSE106817 dataset included 115 CRC patients and 2759 non-cancerous samples. Using Boruta, we identified 146 miRNAs as potential biomarkers for CRC diagnosis. Among these, the highest-scoring miRNAs were: hsa-miR-1228-5p, hsa-miR-6787-5p, hsa-miR-1343-3p, hsa-miR-6717-5p, hsa-miR-3184-5p, hsa-miR-1246, hsa-miR-4706, hsa-miR-8073, hsa-miR-5100. The machine learning models achieved an AUC of 100% when tested on the internal dataset. Additionally, the external validation datasets showed an AUC exceeding 95%, confirming the robustness and reliability of our findings. Furthermore, functional annotation analysis revealed the involvement of several miRNA-mediated pathways in the pathogenesis of CRC.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Colorectal cancer (CRC) is a major lethal health problem being the 3rd most common cancer worldwide with a 19.5% prevalence1,2. According to GLOBOCAN 2022 number of new cases in 2024, both sexes and all ages was 1,931,590 (10% of all cancers), and the number of deaths in 2020, both sexes and all ages was 935,173 (9.4% of all cancers)2. Regarding the genetic basis of cancer malignancy, microarray technology has recently been one of the most widely used implements to evaluate the functions of genes in cancer cases3. MicroRNAs (miRNAs) are small single-stranded non-coding RNA molecules of an average of 22 nucleotides long. miRNAs appear to regulate more than 50% of human genes, and abnormal expression of miRNAs has been implicated in many human cancers4. miRNAs are also abundant as extracellular circulating molecules released into circulation by tumor cells either through cell death or by exosome-mediated signaling5,6. Combined with its remarkable stability in the blood and other body fluids, circulating cell-free miRNAs have the potential to serve as non_invasive biomarkers for cancer screening and diagnosis7. It is a challenge to introduce more accurate, fast, and specific diagnostic and prognostic biomarkers given that CRC is a complex disease. The role of biomarkers in CRC diagnosis is becoming more important to improve early diagnosis and better treatment8,9. In addition, transcription factors (TFs) and miRNAs are two of the most well-studied elements in coregulatory modules. Different modes of regulation add another layer of complexity to the post-transcriptional regulation. Hence, the study of complex diseases at this level will reshape our understanding of pathogenesis and treatment approaches in heterogenous disorders10.

The field of miRNA-disease association (MDAs) prediction has witnessed advancements in recent years owing to large accessable miRNA expression datasets11 and innovative methods such as similaty-based predictions12 and network-based inference13 yet there is no consensus on a globally accepted stratgey to achieve this14. Computational models have become a functional tool for predicting miRNA-disease pairs and substantially reduce the number of targets for experimental validation. This can inherently reduce laboratory costs and be time-efficient15. The efficacy of computational models in introducing prospective miRNAs has been significant as most of the suggested miRNAs were eventually validated by experiments, either in the short term or in the long run16.

As such, there have been numerous efforts to introduce new miRNAs in CRC as regulatory elements17,18,19, biomarkers17,18,20,21,22 and therapeutic targets17,23, all of which have contributed to refining our understanding of CRC development, underlying molecular mechanisms and enhancing diagnostic efficiency. However, majority of the studies have focused on solid tumors or blood as the source of miRNA expression data. Therefore, there is a lack of an in-depth analysis in the current literature with regard to investigating the potential of miRNA expression datasets derived from the serum of CRC patients.

The scale and complexity of microarray data sets are increasing exponentially and machine learning (ML) is one of the essential and effective tools in analyzing highly complex data. This study involved the application of ML techniques like a wrapper method in the feature selection step and robust supervised learning models on miRNA expression datasets, derived from serum. The aim is to identify promising miRNAs and introduce them as non-invasive biomarkers of CRC. Subsequently, a comprehensive functional annotation of the candidate miRNAs was carried out to provide additional insights into their underlying regulatory mechanisms. Overall, we performed an integrated analysis using miRNA expression datasets to discover a robust set of miRNAs and highlighting their significance to be further considered for experimental validation.

Materials and methods

Microarray data collection

Three publicly available microarray datasets on the gene expression omnibus database (GEO) GSE106817, GSE113486, and GSE113740 were for analysis which all are available at available at https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/geo/. The detailed information on the three datasets is shown in (Table 1). In this study, the serum samples of cancer cases and non-cancer controls have been analyzed by microarray to obtain miRNA expression profiles. For the training set, we used GSE106817 and for validation, we used the GSE113486 and GSE113740 datasets, including miRNA expression profile data from the serum samples (Table 1). This study was approved by the Ethics Committee of Tabriz University of Medical Sciences (No: IR.TBZMED.VCR.REC.1401.270).

Differential expression analysis using GEO2R

To identify differentially expressed miRNAs, we also utilized GEO2R, an interactive web-based tool available through the Gene Expression Omnibus (GEO). The analysis was conducted on the (GSE113486 and GSE113740), comparing the cancerous group and control group. The limma package in R was employed to calculate fold changes and p-values, with a significance threshold of [p-value and adjusted p-value]. The results of significant miRNAs were listed for further analysis.

Feature selection techniques

In the analysis of microarray datasets, the number of miRNAs could be larger than the number of samples, thus leading to faulty classification and posing challenges to train the classifiers on such datasets of high dimensionality24,25. Preprocessing is an essential step to address this dimensionality problem, and then apply the classification algorithm for monitoring model complexity26. A critical sept in preprocessing is feature selection methods to overcome the curse of dimensionality27. There are three feature selection techniques in classification, i.e., filter, wrapper, and embedded methods. In the wrapper-based method, feature selection is carried out using the machine learning method and uses cross-validation to assess the feature subset score28.

Boruta

The Boruta algorithm, introduced by Miron B. Kursa and Witold R. Rudnicki in 201029,30, is a wrapper method built around the random forest classification algorithm. Its primary objective is to determine the significance of each feature in the context of the entire features, identifying which features are truly significant for predicting the target feature. Boruta Initiates the process by creating shadow features. These are copies of the original features with their values randomly shuffled, effectively acting as noise features. This step is crucial as it provides a baseline to compare the significance of original features against noise. The algorithm trains a random forest classifier on the extended dataset, which includes both the original and shadow features. The significance of each feature is measured using the mean decrease in the Gini index or any other suitable metric provided by the random forest. The significance scores of the original features are compared against the highest significance score of the shadow features. If an original feature has a significantly higher significance score than the best shadow feature, it is considered significant. Conversely, if an original feature has a lower significance score, it is deemed nonsignificant. Features that are identified as nonsignificantare subsequently excludedfrom the dataset. The process is repeated iteratively until a predefined stopping condition is met, such as a maximum number of iterations or stability in feature selection. Once iterations are finished, the features are categorized into three groups: confirmed significant, confirmed nonsignificant, and tentative. Tentative features require further analysis to determine their significance.

Boruta offers significant advantages in the domain of classification. It is highly robust to overfitting as it leverages the strength of the random forest algorithm and uses shadow features as a baseline for comparison. Unlike many feature selection methods that focus on finding a minimal optimal feature subset, Boruta aims to find all features that carry information about the target feature. By providing a clear distinction between significantand nonsignificantfeatures, Boruta enhances the interpretability of the model, Simplifying identification of features which meaningfully contribute to features contribute to predictions25,31.

Random forest

Breiman introduced random forest (RF)32. One of the significantaspects to note is that the RF algorithm can be applied to applications requiring classification and regression. The Random Forest algorithm relies on the principles of bagging (Bootstrap Aggregating) and random feature selection, which help in reducing the variance of the model and avoiding overfitting. During the construction of each tree, Random Forest selects a random subset of features at each split point. This process, known as feature bagging, ensures that the trees are decorrelated, further diminishing the risk of overfitting33,34. The significanthyperparameters should be set to implement the RF: The number of variables available for splitting at each tree node (mrty).

Extreme gradient boosting

Extreme Gradient Boosting (XGBoost) is a powerful and efficient implementation of the gradient boosting framework, designed to enhance the performance and speed of tree-based ensemble methods35. The objective function in XGBoost combines a loss function and a regularization term. The loss function measures the model’s prediction error, while the regularization term penalizes the complexity of the model, preventing overfitting. The objective function can be represented as:

where \(\:l\) denotes the loss function (e.g., mean squared error for regression), \(\:{\Omega\:}\) is the regularization term, \(\:{y}_{i}\) is the actual target, \(\:{\stackrel{\prime }{y}}_{i}\) is the predicted target, and \(\:{f}_{k}\) represents the \(\:k\)-th tree in the ensemble. XGBoost employs gradient descent to minimize the objective function. In each iteration, it fits a new tree to the negative gradient of the loss function for the current model’s predictions. This stepwise approach iteratively reduces the residual errors. XGBoost introduces both L1 (Lasso) and L 2 (Ridge) regularization to control the complexity of the model, as expressed in the regularization term Ω(\(\:{f}_{k}\)). This helps in preventing overfitting and ensures improved generalization. In the context of handling missing data, XGBoost incorporates an in-built mechanism to manage missing values by learning optimal default directions within its decision trees. This statistical method allows the algorithm to handle incomplete datasets effectively without the need for explicit imputation36. According to Chen et al.37, the XGBoost algorithm’s parameters can be separated into three groups: general parameters, booster parameters, and learning parameters. In this study, the XGBoost algorithm’s booster parameters were: 1- n rounds (max number of boosting iterations) 2- max-depth (used to control over-fitting as higher depth will allow the model to learn relations very specific to a particular sample), 3- gamma (A node is split only when the resulting split gives a positive reduction in the loss function), it specifies the minimum loss reduction required to make a split and makes the algorithm conservative. The values can vary depending on the loss function and should be tuned. 4- colsample-bytree tree denotes the fraction of columns to be randomly sampled for each tree. 5- min-child-weight used to control over-fitting and 6- subsample (lower values make the algorithm more conservative and prevent overfitting but too small values might lead to under-fitting).

Machine learning model evaluation

The analysis was carried out using three different GEO datasets (GSE106187, GSE113486 and GSE113740) as training and validating data for performance comparison with two different machine learning models including RF and XGBoost. Each model was evaluated with different evaluation metrics such as accuracy, area under the ROC curve (AUC), sensitivity, specificity, positive predictive value (PPV), and negative predictive value (NPV). To ensure robust performance evaluation of the models, we incorporated multiple validation strategies. The most commonly used k-fold cross-validation technique was applied in our experimental work. In the k-fold (here, k = 10) cross-validation technique, the dataset is randomly split into k subsets, whereby k-1 subsets are used for training, and the remaining subset serves as the test set. Ultimately, this process iterates k times.

Functional annotation of the identified MiRNAs

Based on the mean of scores (MS), the identified miRNAs with MS higher than 50% were subjected to ontology analysis. In order to identify miRNA-associated pathways, we used miRAnno (https://ophid.utoronto.ca/mirDIP/miRAnno.jsp#r), a network-based program for identifying miRNA-associated pathways38. Additionally, miRNet (https://www.mirnet.ca/miRNet/), which is a miRNA-centric network visual analytics platform was used to identify network between the identified miRNAs, target genes, and associated diseases39. Furthermore, miRNet found target genes were subjected to enrichment analysis using ToppFun (https://toppgene.cchmc.org/enrichment.jsp), which detect functional enrichment of a gene list based on transcriptome, proteome, regulome, ontologies and other features40. TransmiR41 database contains manually curated regulatory interactions between miRNAs and TFs. Our final set of miRNAs (MS > 50%) was added as an input to TransmiR database. On the other hand, the list of target genes by our top miRNAs was given to ChEA42 web server. This database allows us to retrieve overrepresented TFs based on the ChIP-X experiments. The top 5% of the most overrepresented TFs were considered for network assembly. miRNA-target genes network generated by miRNet was also merged. To this end, a TF-miRNA-Gene regulatory network around our candidate miRNAs was constructed using Cystoscope software (Version 3.10.2) from three different sources. As the final step, the top 5 TFs based on the degree of connectivity were isolated from the network, using the “Analyze Network” function within Cytoscape.

Result

Differential expressed MiRNAs in models

The workflow of our study is illustrated in Fig. 1 describing how various methods were merged into an integrative pipeline. Of 2,568 miRNAs in GSE106817, the Boruta algorithm initially selected 122 miRNA using Gini Index measurement. After fixing the tentative features, Boruta identified 146 miRNAs for the analysis. As shown in Table 2, Random Forest and XGBoosting classifiers identified 20 and 16 miRNAs respectively in the internal dataset from 146 miRNAs. In this list 10 of the identified miRNAs would be mutually common (total = 26 miRNAs). Based on the mean of scores, the set of hsa-miR-6787-5p, hsa-miR-1246, hsa-miR-8073, hsa-miR-5100, hsa-miR-6717-5p, hsa-miR-1228-5p, hsa-miR-4706, hsa-miR-3184-5p, and hsa-miR-1343-3p have significant differential expression over 50% in the random forest model all over three datasets. Also, in the XGBoost model hsa-miR-6787-5p and has-miR-1246 had over 40% significance. The results of GEO2R are presented in (Table 3). Note that the column of adjusted p-value is generally recommended as the primary statistic in the interpretation of results. The miRNAs with the smallest p-values will be the most reliable. As shown in Table 3, all of miRNAs have adjusted p-value < 0.0001. hsa-miR-1228-5p, hsa-miR-3184-5p, hsa-miR-6765-5p, and hsa-miR-1268a expressed in both external validation datasets as downregulated.

Performance evaluation

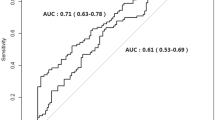

Table 4 presents the optimal hyperparameters for the machine learning models, which were identified using the selected miRNAs. The results of the different performance metrics for each classifier are presented in (Table 4; Fig. 1). In Fig. 2a the heatmap showed differences between samples in each group. In GSE106817, the samples in the right side of the figure show a significantly low miRNA expression level (red color) on the heatmap compared with that in the non-cancerous group. However, miRNA expression levels of the samples on the right side of the figure that are red, are closer to that of the cancerous group. In addition, in Fig. 2b–d for GSE106817 as internal data and external datasets: GSE113486 and GSE113740 in silico validation showed the random forest model achieved better performance with an accuracy of 99.88% and 100% AUC. The XGBoost model achieved an accuracy of 99.71% and 99.9% AUC. In external validation datasets, the models using selected miRNAs achieved, the models achieved great performance as shown in the roc curve, AUC of random forest in GSE113486 and GSE113740 were 97.8% (CI: 92.8–100) and 96.7% (CI: 89.1–100) respectively. The AUC of XGBoost model in GSE113486 and GSE113740 were 98.9% (CI: 96.6–100) and 95.8% (CI: 87.5.1–100) respectively.

Heatmap and Roc curves. Heatmap showing a promising result of the analysis using the 146 identified. miRNAs to distinguish different samples in GSE106817 between non-cancer and control patients (a). Roc curve RF and XGBoost models with selected miRNAs identified through Boruta feature selection algorithm in GSE106817 (b), and in external validation datasets (c,d).

Functional annotation of the identified MiRNAs

The random forest approach identified the following miRNAs with a mean score (MS) exceeding 50%: hsa-miR-1228-5p (MS: 83.46%), hsa-miR-6787-5p (MS: 82.31%), hsa-miR-1343-3p (MS: 81.59%), hsa-miR-6717-5p (MS: 77.57%), hsa-miR-3184-5p, (MS: 75.86%), hsa-miR-1246 (MS: 64.67%), hsa-miR-4706 (MS: 62.47%), hsa-miR-8073 (MS: 55.93%), and hsa-miR-5100 (MS: 53.45%). The XGBoost method also identified hsa-miR-6787-5p (MS: 50.57%) as the sole miRNA with a MS exceeding 50%, similarly identified by random forest as well.

Common miRNAs identified by both models which have MS of higher than 50% were subjected to pathway analysis, during which the miRAnno tool identified a list of pathways associated (P < 0.01) with these miRNAs (Supplementary file 1). Table 5 provides a summary of the cancer/tumor pathways and the top five associated molecular pathways with the selected miRNAs. The miRNet tool identified 106 diseases (Supplementary file 2) and 815 genes (Supplementary file 3) in association with the network of nine selected miRNAs. Among the identified diseases, 59 were cancer-related malignancies, including colorectal carcinoma, colonic neoplasms, and colorectal adenocarcinoma (see Supplementary file 2). Figure 3 was generated by miRNet and depicts the network between the selected miRNAs, their identified target genes, and the diseases with which they are associated. The ToppFun gene list enrichment analysis revealed that the target genes of the selected miRNAs play a significant role in 20 molecular functions and 42 biological processes (Table 6).

miRNA-centric network generated by miRNet. The figure depicts how selected nine miRNAs and their target genes and associated diseases are connected. The blue squares represent miRNAs introduced by random forest and XGBoost approaches for having special relationship with colorectal cancer with a mean score higher than 50%. Every red circle represents a disease (Supplementary file 2) and every light green circle represent a target gene (Supplementary file 3). miRNet reported 106 diseases and 815 genes associated with the selected miRNAs.

A total of 7 TFs (MECP2, BPTF, NFRKB, ZNF614, GMEB2, ZSCAN29, and HMBOX1) were found to interact with hsa-mir-3184-5p (Supplementary file 4). There was no known experimentally validated TF-miRNA interaction for other members of our selected list according to the TransmiR analysis result. TF-overrepresentation analysis introduced 1632 TFs, interacting with 815 target genes of the candidate miRNAs. We focused on the top 5% (81 TFs) having the most overlapping genes and included them to construct the final network (Supplementary file 4). The resulted network consists of 9 miRNA and their target genes, plus the reported TFs which interact with them, supported by experimental data. The final TFs-miRNAs-Genes regulatory network contains 902 nodes and 12,331 edges and is depicted in (Fig. 3a). We sought to identify the most connected TFs based on the degree of connectivity, as the network tends to be dense. The top 5 TFs in the TFs-miRNAs-Genes regulatory network are as follows: E2F1 (degree of 338), E2F4 (degree of 316), CREB1 (degree of 294), REST (degree of 287), and JUND (degree of 280). The full result of the network analysis is available in Supplementary file 4. Additionally, GMEB2 was the only TF that was common among direct regulators of miRNA and target genes of miRNA (Fig. 4a). The zoomed-in view of this particular axis is shown in (Fig. 4b).

Discussion

Three GEO datasets were employed in our study, using a robust and widely recognized feature selection method in machine learning and two distinct machine learning classifier models. We validated the models across datasets, and their performances were assessed using metrics such as accuracy, sensitivity, specificity, PPV, NPV, and AUC. The random forest method demonstrated superior performance with the GSE106187 and GSE113486 datasets, as shown in other studies43,44,45,46,47,48 revealing robustness against overfitting compared to other methods. These two models and analysis approaches have also been effective in other diseases like hepatocellular carcinoma6, gastric cancer49, and ovarian cancer45,46, Additionally, certain studies50,51,52,53,54 influenced our decision to use this method for selecting significantfeatures from the GSE113486 and GSE113740 datasets, respectively. The GSE113486 and GSE113740 datasets, which contain fewer samples of CRC, exhibited lower performance, potentially due to overfitting caused by the limited sample size relative to the model’s complexity. To address this issue and obtain a more reliable performance estimate, we employed 10-fold cross-validation. This technique evaluates the model’s generalization ability by averaging performance metrics across multiple folds, reducing the risk of overfitting. Additionally, to handle class imbalance, we applied SMOTE (Synthetic Minority Over-sampling Technique)55 within each fold of the cross-validation process. This ensures that synthetic samples are generated only from the training data, preventing data leakage and providing a more realistic estimate of model performance. To further validate the stability of our performance estimates, we conducted 100 iterations of the bootstrap method, averaging the evaluation metrics over these iterations. This approach provides a robust assessment of model performance and reduces the impact of variability in the dataset.

It is widely acknowledged that the utilization of in silico network analysis on the findings of experimental or theoretical molecular studies is beneficial in facilitating comprehension of the outcomes, particularly in the context of noncommunicable disease research, including cancer56,57. In this study, we employed the miRAnno, miRNet, and ToppFun tools to gain insight into the function and potential molecular contributions of the selected top-ranked miRNAs. In its analysis, miRAnno links several cancer pathways and molecular pathways to the identified miRNAs. (Table 5). In this section, we examine the involvement of the first-ranked pathway by miRAnno for each of the selected miRNAs in CRC.

The hsa-miR-1228-5p-associated pathway, “Metabolism of ingested SeMet, Sec, MeSec into H2Se,” is implicated in the transformation of inorganic and organic forms of selenium into the intermediate selenide through the trans-selection pathway, selenocysteine lyase, and cystathionine gamma-lyase58,59. It is well established that selenocysteine pathways are involved in some molecular phenomena associated with colon cancer, including autophagy60, sporadic colorectal carcinogenesis, and WNT signaling activity61. Moreover, they are involved in maintaining the integrity of the intestinal barrier62 and influencing a range of other molecular processes related to CRC63.

The miRAnno analysis indicates that the primary pathway associated with hsa-miR-6787-5p is FGFR1 signaling. FGFR1 amplification has been proposed as a prognostic factor in CRC64, and its inhibition has been suggested as a means of suppressing the proliferation of CRC65. The PTK6/STAT3 pathway, which is the most highly ranked in relation to hsa-miR-1343-3p, plays a role in the proliferation, migration, and impaired apoptosis of colon cancer cells66 and in the chemoresistance of CRC67. Benzo(a)pyrene (associated with hsa-miR-6717-5p), which has its origins in dietary habits, has been demonstrated to accelerate colon carcinogenesis68. The primary pathway associated with hsa-miR-3184-5p is NFG/proNGF/p75NTR, and there is a cross talk between androgens and NGF in regulating apoptosis of colon cancer cells69.

Moreover, the overexpression of p75NTR in colon cancer cells resulted in a G1 phase arrest, attenuation of invasion and colony formation, and induced apoptosis70. The saccharide sequence of dermatan sulfate (associated with hsa-miR-1246) chains from human colon cancer is altered from that in normal colon tissue71. hsa-miR-4706 is associated with the WNT ligand secretion/PORCN inhibitor LGK974 pathway. It has been demonstrated that LGK974 is an effective inhibitor of the WNT and MAPK signaling pathways, capable of arresting the cell cycle and inducing apoptosis in CRC cell lines72. Quinol/quinone metabolism (associated with hsa-miR-8073) has been demonstrated to play a role in colon tumor growth73. (S)-3-hydroxy-3-methylglutaryl-CoA degradation, which is linked to hsa-miR-5100, has been shown to be important in favorable clinicopathological characteristics74 and the outcome of statin use in colon cancer cases75,76.

The Gene Ontology (GO) list of biological processes and molecular functions (Table 6) reported by ToppFun for miRNet identified target genes (Supplementary file 3, Fig. 2) align with the findings of miRAnno (Supplementary file 1, Table 5).

TFs-miRNAs-Genes regulatory network GMEB2 is identified as the only common TF between TF regulators of miRNA and their target genes. Figure 3b shows the regulatory axis between GMEB2 and hsa-miR-3184-5p. The elevated expression of GMEB2 and its contribution to CRC progression is explained by stimulating NF-κB signaling pathway77. As shown in Table 3, the expression of hsa-miR-3184-5p is down-regulated in CRC samples. This reciprocal expression of GMEB2 and hsa-miR-3184-5p further highlights the importance of studying this axis in CRC. E2F family of TFs belong to one of the most studied class of genes in CRC, contributing to different aspects of CRC pathogenesis, from tumorigenesis and progression to drug resistance and apoptosis. E2F1 which has been implicated in CRC development and progression via different axes, was found to be the most connected TF in our TFs-miRNAs-Genes regulatory network. To the best of our knowledge, our set of 9 candidate miRNAs have no reports to be directly involved in E2F-madiated signaling. Given the fact that a unique miRNA expression pattern has been observed during CRC progression, an experimental approach to investigate the possible interactions of E2F-mediated signaling and proposed miRNAs is of great importance78. Our results emphasize the need to study the possible interaction of E2F family of TFs, especially E2F1 and E2F4, and their corresponding miRNAs in the context of CRC. Unlike E2F1, E2F4 is a canonical repressor TF in which its interaction with miRNA in CRC is not yet determined. E2F4 was found to be one of the overrepresented TF for the target genes of our 9-candidate miRNA, having 316 overlapped genes according the ChEA libraries. CREB1 is reported to be involved in CRC cell plasticity by modulating NF-κB signaling pathway via CCAT1/MYC regulatory axis79. Recently, Inhibition of JUND was proposed as a therapeutic option as it is involved in stemness of cancer stem cell in CRC80. Interestingly, hsa-miR-1343-3p which was found to have the best classification performance by the XGBoost model and among the top 3 classifiers in Random Forest model, has the highest degree (223) among our 9 candidate miRNAs. Most of these biological processes and molecular functions are fundamental phenomena of cellular life which involved in normal and malignant growth and its regulation and control. It is clear that any sustained disruption to the regulation of these fundamental processes and functions, which is the downstream action of the identified miRNAs, may result in the malignant transformation of colon cells. The provided justifications demonstrate that the identified miRNAs present a valuable opportunity to expand the study to introduce reliable biomarkers for colon cancer diagnosis and/or prognosis.

The potential contributions mentioned above are also supported by other studies, some of which we review here. Yaghoubi et al. identified hsa-miR-1228-5p as a potential biomarker in ovarian cancer81. Additionally, previous studies have suggested that hsa-miR-1228-5p exhibits high diagnostic accuracy for hepatocellular carcinoma82. Furthermore, interactions between hsa-miR-1228-5p and TRIM26 (Tripartite Motif 26) as well as SNRPB (Small Nuclear Ribonucleoprotein Polypeptides B and B1) have been proposed as a potential mechanistic axis influencing the progression of kidney clear cell carcinoma83. It is already established that TRIM26 promotes colorectal cancer growth by inactivating p5384. Moreover, in a pan-cancer analysis that included colon adenocarcinoma, Wu et al. found that SNRPB expression was significantly elevated across nearly all tumor types. They further reported that its upregulation may facilitate tumor progression, impact Tumor-Node-Metastasis (TNM) staging, and serve as a risk factor for poor prognosis across various cancers85. In a separate study, Zhong et al. identified hsa-miR-1228-5p as one of the differentially expressed miRNAs in dermatomyositis-associated interstitial lung disease, specifically in patients with anti-melanoma differentiation-associated protein 5 (MDA5) antibody-positive subsets86. Their target analysis further revealed that ZBTB22 (Zinc Finger and BTB Domain Containing 22) and MDM2 had the strongest evidence for interaction with hsa-miR-1228-5p in a miRNA-mRNA regulatory circuit86. Interestingly, Douglas et al. discovered ZBTB22 mutations in rectal cancer patients with poor response to chemoradiation and proctectomy, whereas these mutations were absent in complete responders87. The role of MDM2 in colon cancer is well established. Notably, its oncogene overexpression in colon adenocarcinoma has been shown to directly influence p53 oncoprotein levels88.

Expanding on miRNA-based biomarkers, Kamkar et al. employed weighted miRNA co-expression network analysis on 972 serum miRNA profiles across thirteen cancer types and healthy individuals. They identified hsa-miR-1228-5p, hsa-miR-1343-3p, hsa-miR-6765-5p, and hsa-miR-6787-5p as promising biomarkers for gastric cancer detection, achieving an accuracy of 87%, specificity of 90%, and sensitivity of 89%89. Similarly, Mitsunaga et al. demonstrated that hsa-miR-1343-5p, in combination with four other miRNAs, serves as a valuable biomarker for the early diagnosis of pancreatobiliary cancer90. Further supporting its role in gastrointestinal cancers, Cao et al. reported a possible interaction between hsa-miR-1343-3p and the DUOX2 (Dual Oxidase 2) gene in pancreatic cancer91. Additionally, it has been shown that DUOX2 promotes colorectal cancer progression by regulating the AKT pathway and interacting with RPL392.

Beyond cancer, Cho et al. identified hsa-miR-6717-5p as one of ten significantly downregulated miRNAs in pseudoexfoliation glaucoma patients compared to controls in a Korean population93. In a large-scale microarray analysis, Chen and Dhahbi examined datasets from 13 cancer types, including colorectal and gastric cancers, using 100 random forest models. Their analysis highlighted hsa-miR-3184-5p as a key diagnostic marker, and a combined model incorporating hsa-miR-3184-5p alongside three other miRNAs achieved an exceptional AUC of 0.9815, underscoring its potential for cancer screening94. Moreover, hsa-miR-3184-5p has been validated as a reliable biomarker for early bladder cancer detection and has a regulatory role in breast cancer95,96. In functional studies, Rajarajan et al. discovered through in vitro assays that miR-3184‐5p was the most upregulated miRNA in adipocyte-induced breast cancer cells. They further identified FOXP4 as a direct target of miR‐3184‐5p, linking it to increased cell proliferation and invasive capacity in breast cancer96. Additionally, elevated FOXP4 expression levels have been associated with advanced pathological stages in colorectal cancer patients97. Meanwhile, the contribution of hsa-miR-1246 to laryngeal squamous cell carcinoma has also been previously established (X19). Finally, hsa-miR-8073 has been introduced by Yaghoubi et al. as a potential biomarker in ovarian cancer98.

Integrating Boruta’s robust feature selection with tree-based classifiers (Random Forest and XGBoost) offers significant potential for advancing colorectal cancer research and clinical practice. The interpretability of tree-based models enables clinicians and biologists to prioritize miRNAs for mechanistic studies, such as exploring their roles in regulating oncogenic pathways and epigenetic modifications. the framework’s adaptability to multi-omics data (e.g., integrating miRNA expression with mRNA or methylation profiles) could refine CRC subtyping or predict therapeutic responses, supporting personalized treatment strategies. Finally, the method’s generalizability makes it applicable to biomarker discovery in other cancers or complex diseases where high-dimensional data and small sample sizes remain a challenge.

It is important to note that this study was subject to certain limitations. The C group sample size was relatively limited. Further limitations included the lack of pathological information, such as tumor stage, age, or other factors, which were not available in our datasets. Furthermore, there is currently no experimental data available to substantiate our theoretical findings. Future work could validate these miRNAs in prospective cohorts or integrate them with clinical variables to build risk-stratification tools for clinical deployment.

Conclusion

In this paper, we applied decision tree-based machine learning algorithms along with wrapper methods from feature selection approaches to model colorectal cancer using miRNAs expression data from serum. Our Integrated bioinformatics analysis selected 20 significantmiRNAs that could be potential biomarkers for diagnosis of CRC, achieving an AUC of over 90%. Based on our model’s results and additional filtering using MS > 50%, we further narrowed the final candidate miRNAs down to 9 miRNAs (hsa-miR-1228-5p, hsa-miR-6787-5p, hsa-miR-1343-3p, hsa-miR-6717-5p, hsa-miR-3184-5p, has-miR-1246, has-miR-4706, has-miR-8073, and has-miR-5100) which are proposed to be promising diagnostic biomarkers. As the experimental validation to further corroborate our results is missing, the accuracy of our model is sufficiently high (100% AUC) to justify further examination of potential clinical applications.

Data availability

The Gene Expression Omnibus contains the datasets used in this analysis (https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/geo/), accession numbers GSE106187, GSE113486 and GSE113740.

References

Chhikara, B. S. & Parang, K. Global cancer statistics 2022: the trends projection analysis. Chem. Biology Lett. 10 (1), 451 (2023).

Bray, F. et al. Global cancer statistics 2022: GLOBOCAN estimates of incidence and mortality worldwide for 36 cancers in 185 countries. CA Cancer J. Clin. 74 (3), 229–263 (2024).

Hephzibah Cathryn, R., Udhaya Kumar, S., Younes, S., Zayed, H. & George Priya Doss, C. A review of bioinformatics tools and web servers in different microarray platforms used in cancer research. Adv. Protein Chem. Struct. Biol. 131, 85–164 (2022).

Schwarzenbach, H., Nishida, N., Calin, G. A. & Pantel, K. Clinical relevance of Circulating cell-free MicroRNAs in cancer. Nat. Reviews Clin. Oncol. 11 (3), 145–156 (2014).

Ortiz-Quintero, B. Extracellular MicroRNAs as intercellular mediators and noninvasive biomarkers of cancer. Cancers (Basel) 12, (11). (2020).

Conti, I. et al. MiRNAs as influencers of Cell-Cell communication in tumor microenvironment. Cells 9 (1). (2020).

Mitchell, P. S. et al. Circulating microRNAs as stable blood-based markers for cancer detection. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. 105 (30), 10513-8. (2008).

Van Deusen, J. & Hsu, D. S. Predictive and prognostic biomarkers in colorectal cancer. Front. Biology. 6 (6), 482–489 (2011).

Zygulska, A. L. & Pierzchalski, P. Novel diagnostic biomarkers in colorectal cancer. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 23 (2), 852 (2022).

Zhang, Z., Zou, Z., Zhang, H. & Zhang, D-M. Regulatory network analysis based on integrated miRNA-TF reveals key genes in heart failure. Sci. Rep. 14 (1), 13896 (2024).

Huang, L., Zhang, L. & Chen, X. Updated review of advances in MicroRNAs and complex diseases: experimental results, databases, webservers and data fusion. Brief. Bioinform. 23 (6), bbac397 (2022).

Chen, X., Wang, L., Qu, J., Guan, N-N. & Li, J-Q. Predicting miRNA–disease association based on inductive matrix completion. Bioinformatics 34 (24), 4256–4265 (2018).

Chen, X., Yin, J., Qu, J. & Huang, L. MDHGI: matrix decomposition and heterogeneous graph inference for miRNA-disease association prediction. PLoS Comput. Biol. 14 (8), e1006418 (2018).

Huang, L., Zhang, L. & Chen, X. Updated review of advances in MicroRNAs and complex diseases: towards systematic evaluation of computational models. Brief. Bioinform. 23 (6), bbac407 (2022).

Chen, X., Xie, D., Zhao, Q. & You, Z-H. MicroRNAs and complex diseases: from experimental results to computational models. Brief. Bioinform. 20 (2), 515–539 (2019).

Huang, L., Zhang, L. & Chen, X. Updated review of advances in MicroRNAs and complex diseases: taxonomy, trends and challenges of computational models. Brief. Bioinform. 23 (5), bbac358 (2022).

Ma, J., Wang, P., Huang, L., Qiao, J. & Li, J. Bioinformatic analysis reveals an Exosomal miRNA-mRNA network in colorectal cancer. BMC Med. Genom. 14, 1–18 (2021).

Wang, X. et al. Identification of the MiRNA signature and key genes in colorectal cancer lymph node metastasis. Cancer Cell Int. 21, 1–12 (2021).

Horaira, M. A. et al. Bioinformatics screening of colorectal-cancer causing molecular signatures through gene expression profiles to discover therapeutic targets and candidate agents. BMC Med. Genom. 16 (1), 64 (2023).

Fonseca, A. et al. Identification of colorectal cancer associated biomarkers: an integrated analysis of MiRNA expression. Aging (albany NY). 13 (18), 21991 (2021).

Meng, T. et al. Comprehensive bioinformatics analysis of functional molecules in colorectal cancer. J. Gastrointest. Oncol. 13 (1), 231 (2022).

Wang, Y. et al. Establishing a three-miRNA signature as a prognostic model for colorectal cancer through bioinformatics analysis. Aging (Albany NY). 13 (15), 19894 (2021).

Yan, M., Song, M., Bai, R., Cheng, S. & Yan, W. Identification of potential therapeutic targets for colorectal cancer by bioinformatics analysis. Oncol. Lett. 12 (6), 5092–5098 (2016).

Hira, Z. M. & Gillies, D. F. A review of feature selection and feature extraction methods applied on microarray data. Adv. Bioinformat. (2015).

Nivedhitha, M., Durai, V., Raj, S. & Chuan-Yu, C. Machine learning based computational gene selection models: a survey, performance evaluation, open issues, and future research directions. Front. Genet. 11, 603808 (2020).

Alam, S. & Yao, N. The impact of preprocessing steps on the accuracy of machine learning algorithms in sentiment analysis. Comput. Math. Organ. Theory. 25, 319–335 (2019).

Kira, K. & Rendell, L. A. A practical approach to feature selection. Machine Learning Proceedings 1992 pp. 249–56. (Elsevier, 1992).

Liu, H. & Setiono, R. Systems Feature selection and classification–a probabilistic wrapper approach. Industrial and Engineering Applications of Artificial Intelligence and Expert CRC Press pp. 419 – 24. (1996).

Kursa, M. B., Jankowski, A. & Rudnicki, W. R. Boruta–a system for feature selection. Fundamenta Informaticae. 101 (4), 271–285 (2010).

Kursa, M. B., Rudnicki, W. R. & Kursa, M. M. B. Package ‘boruta’. R J. 15. (2018).

Degenhardt, F., Seifert, S. & Szymczak, S. Evaluation of variable selection methods for random forests and omics data sets. Brief. Bioinform. 20 (2), 492–503 (2019).

Breiman, L. Random forests. Mach. Learn. 45 (1), 5–32 (2001).

Breiman, L., Friedman, J. H., Olshen, R. A. & Stone, C. J. Classification and Regression Trees (Routledge, 2017).

Gould, A. L. Statistical Methods for Evaluating Safety in Medical Product Development (Wiley, 2015).

Chen, T. et al. Xgboost: extreme gradient boosting. R Package Version 04 – 2. 1 (4), 1–4 (2015).

Cui, Y., Cai, M. & Stanley, H. E. Comparative analysis and classification of cassette exons and constitutive exons. BioMed Res. Int. (2017).

Chen, T. et al. Xgboost: Extreme Gradient Boosting; R Package Version 0.4-2; Google Scholar There is no corresponding record for this reference. 2016. (2015).

Tokar, T. et al. MirDIP 4.1—integrative database of human MicroRNA target predictions. Nucleic Acids Res. 46 (D1), D360–D70 (2018).

Chang, L. & Xia, J. MicroRNA Regulatory Network Analysis Using miRNet 2.0. Transcription Factor Regulatory Networks p. 185–204 (Springer, 2022).

Chen, J., Bardes, E. E., Aronow, B. J. & Jegga, A. G. ToppGene suite for gene list enrichment analysis and candidate gene prioritization. Nucleic Acids Res. 37 (suppl_2), W305–W11 (2009).

Tong, Z., Cui, Q., Wang, J. & Zhou, Y. TransmiR v2. 0: an updated transcription factor-microRNA regulation database. Nucleic Acids Res. 47 (D1), D253–D8 (2019).

Lachmann, A., Xu, H., Krishnan, J., Berger, S. I. & Mazloom, A. R. Ma’ayan A. ChEA: transcription factor regulation inferred from integrating genome-wide ChIP-X experiments. Bioinformatics 26 (19), 2438–2444 (2010).

Yao, D., Zhan, X. & Kwoh, C-K. An improved random forest-based computational model for predicting novel miRNA-disease associations. BMC Bioinform. 20, 1–14 (2019).

He, Y. et al. A support vector machine and a random forest classifier indicates a 15-miRNA set related to osteosarcoma recurrence. OncoTarg. Ther. 253–269. (2018).

Hamidi, F. et al. Identifying potential Circulating MiRNA biomarkers for the diagnosis and prediction of ovarian cancer using machine-learning approach: application of Boruta. Front. Digit. Health. 5, 1187578 (2023).

Hamidi, F. et al. Exploration of potential MiRNA biomarkers and prediction for ovarian cancer using artificial intelligence. Front. Genet. 12. (2021).

Yerukala Sathipati, S. & Ho, S-Y. Novel MiRNA signature for predicting the stage of hepatocellular carcinoma. Sci. Rep. 10 (1), 14452 (2020).

Wu, Y. et al. Identification of subtype specific biomarkers of clear cell renal cell carcinoma using random forest and greedy algorithm. Biosystems 204, 104372 (2021).

Azari, H. et al. Machine learning algorithms reveal potential MiRNAs biomarkers in gastric cancer. Sci. Rep. 13 (1), 6147 (2023).

Zhang, X. et al. Construction of a nine-MicroRNA-based signature to predict the overall survival of esophageal cancer patients. Front. Genet. 12, 670405 (2021).

Zhang, Z. et al. Identification of microRNA-451a as a novel Circulating biomarker for colorectal cancer diagnosis. Biomed. Res. Int. 2020 (1), 5236236 (2020).

Yao, Y. et al. Identification of serum Circulating MicroRNAs as novel diagnostic biomarkers of gastric cancer. Front. Genet. 11, 591515 (2021).

Xu, Z. et al. Identification and validation of blood MiRNAs as diagnostic markers of gastric cancer. (2022).

Shen, C. et al. Identification of a dysregulated CircRNA-associated gene signature for predicting prognosis, immune landscape, and drug candidates in bladder cancer. Front. Oncol. 12, 1018285 (2022).

Chawla, N. V., Bowyer, K. W., Hall, L. O. & Kegelmeyer, W. P. SMOTE: synthetic minority over-sampling technique. J. Artif. Intell. Res. 16, 321–357 (2002).

Aftabi, Y. et al. Long non-coding RNAs as potential biomarkers in the prognosis and diagnosis of lung cancer: A review and target analysis. IUBMB Life. 73 (2), 307–327 (2021).

Akin, M. N. et al. Changes of miR-139-5p, TGFB1, and COL1A1 in the placental tissue of cases with gestational diabetes mellitus. Gene 897, 148061 (2024).

Esaki, N. et al. Enzymic synthesis of selenocysteine in rat liver. Biochemistry 20 (15), 4492–4496 (1981).

Pinto, J. T., Lee, J-I., Sinha, R., MacEwan, M. E. & Cooper, A. J. Chemopreventive mechanisms of α-keto acid metabolites of naturally occurring organoselenium compounds. Amino Acids. 41, 29–41 (2011).

Hsu, W-L. et al. Blockage of Nrf2 and autophagy by L-selenocystine induces selective death in Nrf2-addicted colorectal cancer cells through p62-Keap-1-Nrf2 axis. Cell Death Dis. 13 (12), 1060 (2022).

Pilat, J. M. et al. SELENOP modifies sporadic colorectal carcinogenesis and WNT signaling activity through LRP5/6 interactions. J. Clin. Investig. 133 (13). (2023).

Canter, J. A. et al. Selenium and the 15 kda Selenoprotein impact colorectal tumorigenesis by modulating intestinal barrier integrity. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 22 (19), 10651 (2021).

Peters, K. M., Carlson, B. A., Gladyshev, V. N. & Tsuji, P. A. Selenoproteins in colon cancer. Free Radic. Biol. Med. 127, 14–25 (2018).

Bae, J. M. et al. Fibroblast growth factor receptor 1 (FGFR1) amplification detected by droplet digital polymerase chain reaction (ddPCR) is a prognostic factor in colorectal cancers. Cancer Res. Treatment: Official J. Korean Cancer Association. 52 (1), 74–84 (2020).

Zhao, R. et al. Targeting FGFR1 by β, β-dimethylacrylalkannin suppresses the proliferation of colorectal cancer in cellular and xenograft models. Phytomedicine 129, 155612 (2024).

Gierut, J. et al. Disruption of the mouse protein tyrosine kinase 6 gene prevents STAT3 activation and confers resistance to azoxymethane. Gastroenterology 141 (4), 1371–1380 (2011). e2.

Liu, C. et al. Pharmacological targeting PTK6 inhibits the JAK2/STAT3 sustained stemness and reverses chemoresistance of colorectal cancer. J. Experimental Clin. Cancer Res. 40, 1–19 (2021).

Harris, K. L., Harris, K. J., Banks, L. D., Adunyah, S. E. & Ramesh, A. Acceleration of benzo (a) pyrene-induced colon carcinogenesis by Western diet in a rat model of colon cancer. Curr. Res. Toxicol. 6, 100162 (2024).

Anagnostopoulou, V. et al. Differential effects of dehydroepiandrosterone and testosterone in prostate and colon cancer cell apoptosis: the role of nerve growth factor (NGF) receptors. Endocrinology 154 (7), 2446–2456 (2013).

Yang, Z. et al. Epigenetic inactivation and tumor-suppressor behavior of NGFR in human colorectal cancer. Mol. Cancer Res. 13 (1), 107–119 (2015).

Daidouji, K. et al. Neoplastic changes in saccharide sequence of dermatan sulfate chains derived from human colon cancer. Dig. Dis. Sci. 47, 331–337 (2002).

Bagheri, M., Tabatabae Far, M. A., Mirzaei, H. & Ghasemi, F. Evaluation of antitumor effects of aspirin and LGK974 drugs on cellular signaling pathways, cell cycle and apoptosis in colorectal cancer cell lines compared to oxaliplatin drug. Fundam. Clin. Pharmacol. 34 (1), 51–64 (2020).

Oh, E-T. et al. NQO1 inhibits proteasome-mediated degradation of HIF-1α. Nat. Commun. 7 (1), 13593 (2016).

Bengtsson, E. et al. HMG-CoA reductase expression in primary colorectal cancer correlates with favourable clinicopathological characteristics and an improved clinical outcome. Diagn. Pathol. 9, 1–6 (2014).

Lipkin, S. M. et al. Genetic variation in 3-hydroxy-3-methylglutaryl coa reductase modifies the chemopreventive activity of Statins for colorectal cancer. Cancer Prev. Res. 3 (5), 597–603 (2010).

Gray, R. T. et al. Statin use, candidate mevalonate pathway biomarkers, and colon cancer survival in a population-based cohort study. Br. J. Cancer. 116 (12), 1652–1659 (2017).

Ning, Z. et al. GMEB2 promotes the growth of colorectal cancer by activating ADRM1 transcription and NF-κB signalling and is positively regulated by the m6A reader YTHDF1. Cancers 14 (24), 6046 (2022).

Xu, Z. et al. An update on the potential roles of E2F family members in colorectal cancer. Cancer Manag. Res. 5509–5521. (2021).

Li, B. et al. CREB1 contributes colorectal cancer cell plasticity by regulating LncRNA CCAT1 and NF-κB pathways. Sci. China Life Sci. 65 (8), 1481–1497 (2022).

Chang, Y. et al. USP7-mediated JUND suppresses RCAN2 transcription and elevates NFATC1 to enhance stem cell property in colorectal cancer. Cell Biol. Toxicol. 39 (6), 3121–3140 (2023).

Jing, Z., Guo, S., Zhang, P. & Liang, Z. LncRNA-associated CeRNA network reveals novel potential biomarkers of laryngeal squamous cell carcinoma. Technol. Cancer Res. Treat. 19, 1533033820985787 (2020).

Tan, Y. et al. A serum MicroRNA panel as potential biomarkers for hepatocellular carcinoma related with hepatitis B virus. PloS One. 9 (9), e107986 (2014).

Shen, J. et al. Comprehensive analysis of expression profiles and prognosis of TRIM genes in human kidney clear cell carcinoma. Aging (Albany NY). 14 (10), 4606 (2022).

Tan, Z. et al. Tripartite motif-containing protein 26 promotes colorectal cancer growth by inactivating p53. Cell. Death Differ. 1–11. (2025).

Wu, J., Lu, F., Yu, B., Wang, W. & Ye, X. The oncogenic role of SNRPB in human tumors: a pan-cancer analysis. Front. Mol. Biosci. 9, 994440 (2022).

Zhong, D. et al. Plasma-derived Exosomal hsa‐mir‐4488 and hsa‐mir‐1228‐5p: novel biomarkers for dermatomyositis‐associated interstitial lung disease with anti‐melanoma differentiation‐associated protein 5 antibody‐positive subset. Biomed. Res. Int. 2021 (1), 6676107 (2021).

Douglas, J. K. et al. Genomic variation as a marker of response to neoadjuvant therapy in locally advanced rectal cancer. Mol. Cell. Oncol. 7 (3), 1716618 (2020).

Niotis, A. et al. P53/MDM2 complex-based targeted strategies in colon adenocarcinoma. Acta Med. Academica. 52 (1), 24 (2023).

Kamkar, L., Saberi, S., Totonchi, M. & Kavousi, K. Circulating MicroRNA panels for multi-cancer detection and gastric cancer screening: leveraging a network biology approach. BMC Med. Genom. 18, 27 (2025).

Ganepola, G. A., Rutledge, J. R., Suman, P., Yiengpruksawan, A. & Chang, D. H. Novel blood-based MicroRNA biomarker panel for early diagnosis of pancreatic cancer. World J. Gastrointest. Oncol. 6 (1), 22 (2014).

Cao, M. et al. DUOX2 as a potential prognostic marker which promotes cell motility and proliferation in pancreatic cancer. Biomed. Res. Int. 2021 (1), 6530298 (2021).

Zhang, X. et al. DUOX2 promotes the progression of colorectal cancer cells by regulating the AKT pathway and interacting with RPL3. Carcinogenesis 42 (1), 105–117 (2021).

Cho, H. et al. MicroRNA profiles in aqueous humor between pseudoexfoliation glaucoma and normal tension glaucoma patients in a Korean population. Sci. Rep. 12 (1), 6217 (2022).

Chen, J. W. & Dhahbi, J. Identification of four serum MiRNAs as potential markers to screen for thirteen cancer types. PLoS One. 17 (6), e0269554 (2022).

Usuba, W. et al. Circulating MiRNA panels for specific and early detection in bladder cancer. Cancer Sci. 110 (1), 408–419 (2019).

Rajarajan, D., Selvarajan, S., Charan Raja, M. R., Kar Mahapatra, S. & Kasiappan, R. Genome-wide analysis reveals miR‐3184‐5p and miR‐181c‐3p as a critical regulator for adipocytes‐associated breast cancer. J. Cell. Physiol. 234 (10), 17959–17974 (2019).

Wu, H., Tao, Y., Zhang, W., Wang, G. & Zhang, Q. circ-0000212 promotes cell proliferation of colorectal cancer by sponging miR-491 and modulating FOXP4 expression. Mol. Med. Rep. 23 (4), 300 (2021).

Yaghoobi, H., Babaei, E., Hussen, B. M. & Emami, A. EBST: an evolutionary multi-objective optimization based tool for discovering potential biomarkers in ovarian cancer. IEEE/ACM Trans. Comput. Biol. Bioinf. 18 (6), 2384–2393 (2020).

Yokoi, A. et al. Integrated extracellular MicroRNA profiling for ovarian cancer screening. Nat. Commun. 9 (1), 1–10 (2018).

Yamamoto, Y. et al. Highly sensitive Circulating MicroRNA panel for accurate detection of hepatocellular carcinoma in patients with liver disease. Hepatol. Commun. 4 (2), 284–297 (2020).

Acknowledgements

This study was supported by Tabriz University of Medical Sciences with Grant Number 70637. The authors would like to thank all those who spent their valuable time participating in this research project, and we are also immensely grateful to the “anonymous” reviewers.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

FH, NG, and AK contributed to the conception and design of the study. FH, NG, and AK performed the statistical analysis. FH wrote the first draft of the manuscript. YA, MS and AJ wrote the biological discussion section. FH, NG, YA, MS and AJ wrote sections of the manuscript. All authors contributed to the manuscript revision and read and approved the submitted version.

Corresponding authors

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Ethics approval and consent to participate

This study was approved by the Ethics Committee of Tabriz University of Medical Sciences (No: IR.TBZMED.VCR.REC.1401.270).

Additional information

Publisher’s note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Supplementary Information

Below is the link to the electronic supplementary material.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if you modified the licensed material. You do not have permission under this licence to share adapted material derived from this article or parts of it. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Hamidi, F., Gilani, N., Kazemnejad, A. et al. Decision tree-based machine learning methods for identifying colorectal cancer-associated microRNA signatures and their regulatory networks. Sci Rep 15, 34700 (2025). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-17037-7

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-17037-7