Abstract

Burnout among midwives is a critical issue influenced by organisational and work environment factors, potentially impacting job satisfaction and overall well-being. Workplace conditions and organisational support play a crucial role in determining job satisfaction and burnout levels in healthcare professionals, particularly midwives. Understanding these relationships can inform strategies to enhance job satisfaction and reduce burnout. This study aimed to examine the relationships between organisational factors, work environment and burnout among Jordanian midwives, with job satisfaction as a mediating factor. A cross-sectional study was conducted among 182 midwives employed in Ministry of Health hospitals. Data were collected using a sociodemographic questionnaire, the McCloskey/Mueller Satisfaction Scale (MMSS), the Practice Environment Scale of the Nursing Work Index (PES-NWI), the Copenhagen Burnout Inventory (CBI) and the McCain and Marklin Social Integration (MMSI) Scale. Structural Equation Modelling (SEM) was used to test the proposed conceptual model. Results showed that 45.1% of midwives experienced high burnout, while 52.2% reported moderate burnout. SEM analysis indicated a direct association between burnout and coworker and supervisor support (β = − 0.18; p < 0.001), experience (β = 0.38; p < 0.001) and marital status (β = 0.38; p ≤ 0.001). The work area had an indirect effect on burnout (β = − 0.23; p < 0.001). Job satisfaction mediated the relationships between work environment, coworker and supervisor support and demographic factors, highlighting its role in reducing burnout. Enhancing workplace conditions and fostering supportive professional relationships may improve job satisfaction and mitigate burnout among midwives.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Midwives play a vital role in maternal and neonatal health by providing essential care during pregnancy, childbirth and the postpartum period. However, they often face high demands that contribute to a challenging work environment, adversely affecting job satisfaction and increasing the risk of burnout1.

Burnout is a prevalent condition among healthcare professionals, characterised by emotional exhaustion, depersonalisation and a diminished sense of personal accomplishment2. This not only affects individual well-being and health but also compromises the quality of care provided to mothers, newborns and healthcare teams. Midwives, as a subgroup of healthcare providers, are particularly susceptible to burnout due to heavy workloads, limited autonomy and insufficient professional recognition1.

The work environment encompasses physical, social and organisational factors, all of which influence job satisfaction and burnout levels2. Research indicates that unsupportive organisational environments, marked by poor teamwork and ineffective leadership, lower job satisfaction and contribute to higher burnout rates3,4. In contrast, positive working conditions and adequate organisational support help reduce stress and dissatisfaction, enhancing job satisfaction2, which often serves as a mediating factor between the work environment and burnout.

Demographics factors such as age, marital status, work experience and work area, alongside organisational factors, have been identified as key determinants of job satisfaction and burnout3. For instance, midwives with less than 10 years of experience are more likely to experience higher burnout levels than those with over 10 years of experience, particularly in high-demand settings, due to limited supervisor support and reduced professional autonomy1. Although there is increasing evidence on these factors in midwifery, most studies on job satisfaction among midwives have been conducted in Western countries, where individualistic societal norms prevail. In contrast, limited research has examined midwives in low- and middle-income countries, considering job satisfaction within cultural contexts5,6. Given the distinct cultural and organisational structures in midwifery practice, these relationships may vary and warrant further investigation.

This study explores the relationship between work environment, job satisfaction and burnout among Jordanian midwives, a context influenced by collectivist cultural norms where family and social dynamics play a significant role in workplace experiences7,8. It examines the impact of organisational factors on burnout and the mediating role of job satisfaction. The findings aim to guide targeted interventions to improve workplace conditions, enhance job satisfaction and reduce burnout, ultimately benefitting both midwives and the women and newborns they care for.

Theoretical framework

Theoretical framework with empirical citations

This study is based on the Job Demands-Resources (JD-R) model, a well-established framework in occupational health psychology2,9. The JD-R model explains how organisational and individual factors influence workplace outcomes, including job satisfaction and burnout. This study applies the model within the cultural and professional context of Arab midwives, who typically belong to collectivist societies. The model provides insights into the relationships among demographic factors, job resources, job satisfaction and burnout in this unique setting. It illustrates the logical connections between these constructs and emphasises their independence, suggesting that interventions should target multiple levels to effectively address burnout2. The following section outlines the model’s structure and key components.

Demographic factors such as age, experience, education and family income play a crucial role in shaping job resources, which subsequently affect job satisfaction5,6. These factors help explain individual differences that influence workplace experiences 3. The model identifies the work environment, along with psychological and social support, as key job resources essential for reducing stress and enhancing job satisfaction, thereby serving as protective factors against burnout.

Job satisfaction functions as a mediator between job resources and burnout. A supportive work environment and sufficient psychological and social support contribute to higher job satisfaction, which in turn lowers burnout levels10. Consequently, burnout reflects the outcome of inadequate psychological and social support, an unfavourable work environment and low job satisfaction1.

Applying the model to Arab midwives

Demographics in collectivist societies

In collectivist cultures, demographic factors such as age, experience, education and family responsibilities play a significant role in workplace behaviour and job satisfaction5,6,8,11. Within Arab communities, societal norms prioritise family and communal well-being over individual interests12, requiring working women to balance professional and domestic responsibilities. Seniority, both in age and experience, is highly valued in these cultures13 often dictates the level of respect and support received in professional settings. Even a small difference in age or experience can influence workplace interactions due to deeply ingrained social hierarchies. Married midwives or those with caregiving responsibilities may experience additional pressures due to cultural expectations surrounding familial roles14. For instance, married midwives with children are more likely to rely on workplace social support to navigate dual responsibilities, whereas younger and less experienced midwives often require mentorship and guidance from senior colleagues15. Additionally, family income can influence job satisfaction by affecting a midwife’s ability to manage work and family obligations, as financial stability often determines access to resources and support systems16. Research suggests that these demographic factors have a significant impact on job satisfaction and burnout, particularly in healthcare settings.

Job resources in Arab workplaces

In collectivist societies, workplace relationships often resemble familial bonds, fostering trust, respect and collaboration7,17. Support from supervisors and colleagues extends beyond professional interactions to include emotional and social dimensions, reflecting the communal nature of the work environment17. In Arab workplaces, job resources are not limited to material or procedural aspects but also encompass emotional connections, trust and mutual respect18.

Healthcare settings in Arab societies typically are typically structured hierarchically, with an emphasis on mutual respect and collective problem-solving19. Research indicates that psychological and social support from colleagues and supervisors plays a crucial role in reducing emotional exhaustion and enhancing job satisfaction17,18. Peer relationships and familial-style support networks within the workplace are particularly important in emotionally demanding environments, helping midwives cope with workplace challenges20.

Job satisfaction as a mediator

In collectivist cultures, job satisfaction is closely linked to societal approval and a sense of contributing to the greater good, rather than being solely defined by professional achievement7,19,21. It reflects an individual’s ability to fulfil both community and family expectations7,8.

Job satisfaction mediates the relationship between job resources and burnout. Feeling valued and supported in the workplace reduces emotional exhaustion and enhances a sense of accomplishment, promoting overall well-being and engagement1,8. Studies suggest that job satisfaction serves as a crucial buffer against workplace stressors, particularly for healthcare professionals facing high emotional demands1.

Burnout and job satisfaction outcomes

High job demands, combined with cultural expectations to prioritise collective needs over individual well-being, contribute to burnout. Midwives in Arab societies often work long hours, perform significant emotional labour and face the additional burden of balancing professional and family responsibilities5. These factors frequently result in emotional exhaustion and physical fatigue, as observed in studies of healthcare professionals within collectivist settings5,6.

Job satisfaction encompasses both personal and collective fulfilment7,8,19. For midwives in collectivist societies, satisfaction is influenced not only by workplace conditions but also by the recognition and support received from their community and family8. Research indicates that recognition and social support are key determinants of job satisfaction, particularly in culturally cohesive workplaces22,23. Job satisfaction plays a crucial role in mitigating burnout, especially in collectivist settings where work is perceived as a shared responsibility1. Midwives who feel valued and supported are less likely to experience emotional exhaustion and more likely to remain engaged in their roles.

Relevance of the JD-R model to Arab midwives

This study applies the JD-R model to the cultural and organisational context of Arab midwives, who work within healthcare systems influenced by collectivist values. By integrating demographic and familial factors, the framework recognises the significant impact of community and family dynamics on workplace experiences. The study underscores the mediating role of job satisfaction, demonstrating how cultural values such as interdependence and social support from colleagues and supervisors interact with job resources to reduce burnout and improve satisfaction.

Research implications for the Arab context

This study offers valuable insights into the challenges midwives face in collectivist Arab societies, particularly in managing work and family responsibilities. It highlights the need for culturally relevant workplace interventions, such as fostering supportive environments, implementing mentorship programmes and strengthening psychological and social support systems. These approaches align with collectivist values and can enhance job satisfaction while mitigating burnout. The findings contribute to policy recommendations aimed at improving workplace conditions for midwives, ultimately supporting better maternal and neonatal healthcare outcomes and ensuring workforce sustainability in Arab settings.

This study addresses a significant gap in the literature on Jordanian midwives by exploring the relationship between job satisfaction, burnout and organisational factors. While previous studies provided insights into overall job satisfaction and burnout levels, they did not assess the impact of specific organisational factors, such as the work environment and support systems, on these outcomes5,6. Moreover, they did not examine the mediating role of job satisfaction in reducing burnout. This study integrates these elements into a comprehensive framework, offering a more detailed understanding of the factors influencing midwives’ well-being and professional retention.

In Jordan’s healthcare system, where midwives play a vital role in maternal and newborn care, understanding these dynamics is essential for developing interventions that enhance job satisfaction, improve care quality and reduce burnout. By examining the mediating role of job satisfaction, this study provides valuable insights for policymakers and healthcare administrators, setting it apart from previous research and contributing meaningfully to the field of midwifery. This study offers a timely and evidence-based approach to strengthening midwifery practice in Jordan.

The following hypotheses were formulated, with Box 1 providing further details:

H1

β1, β2, β3 ≠ 0.

H1

Demographic factors (age, experience, marital status) significantly influence job resources (work environment and psychological/social support).

H2

β1, β2 ≠ 0.

H2

Work environment and psychological/social support significantly influence job satisfaction.

H3

(β1a + β1b) ⋅β2 ≠ 0.

H3

Job satisfaction mediates the relationship between the work environment, psychological support and burnout.

Methods

Design, sampling and settings

A cross-sectional design was employed to recruit 182 midwives working in healthcare settings in Jordan. As per the most recent report published in 2024, the total number of registered midwives was 844. Accordingly, the participants in our study (n = 182) represent approximately 21.6% of the total midwife population24. The study was conducted between September and December 2024. Inclusion criteria were: (a) Jordanian midwives, (b) currently employed in Jordanian healthcare setting, (c) able to speak and read Arabic, (d) with at least 1 year of experience as a midwife and (e) willing to provide written consent. Exclusion criteria were: (a) Midwives on leave or, (b) those who declined to participate were excluded.

Ethical approval

The study was approved by the Institutional Review Board at the Jordan University of Science and Technology (ethics number MBA/IRB/14,601) and conducted in accordance with the Declaration of Helsinki. Additionally, Written informed consent was obtained from all participants involved in the study.

Data collection procedure: Participants were contacted through the Jordanian Nursing Association’s database. Emails were sent to invite midwives to participate in the study, providing detailed information on the study’s purpose, objectives, procedures and confidentiality assurances. A researcher’s contact information was included for any questions or clarifications. Reminders were sent biweekly throughout the study period, from September 2024 to December 2024, to encourage participation. Eligible respondents were screened and sent a consent form. Those who provided informed consent were given a secure link to access and complete the questionnaire.

Study measures

This study used previously validated instruments to measure key constructs related to burnout, job satisfaction, work environment, and social support. Although confirmatory factor analysis (CFA) was performed as part of the structural equation modelling (SEM) process, it was done solely to assess the adequacy of the measurement model within this sample. The study’s primary objective was not to validate instruments, but to examine the relationships between these variables using a cross-sectional design guided by the Job Demands-Resources (JD-R) framework.

The survey included the following tools: the McCloskey/Mueller Satisfaction Scale (MMSS), the Practice Environment Scale of the Nursing Work Index (PES-NWI), the Copenhagen Burnout Inventory (CBI), and the McCain and Marklin Social Integration Scale (MMSI). All tools were previously validated in Arabic-speaking healthcare populations and are discussed in detail in the following paragraphs.

-

1.

Demographic characteristics: Age, marital, work experience in years, developed by researchers based on existing literature.

-

2.

McCloskey/Mueller satisfaction scale (MMSS): The MMSS is a valid survey instrument for assessing midwives’ job satisfaction in various healthcare settings25. The refined 31-item version measures eight satisfaction dimensions: external rewards, service schedules, work-family balance, coworker relationships, workplace interactions, professional development opportunities, public recognition and responsibility. These dimensions assess social support, recognition, career growth and work–life balance. Responses are recorded on a 5-point Likert scale, ranging from ‘strongly disagree’ to ‘strongly agree’. Scores are categorised from ‘very poor’ to ‘very good’. The scale showed high reliability, with Cronbach’s alpha of 0.92 among Jordanian midwives5, in this study the Cronbach’s alpha of this scale was 0.90.

-

3.

Practice environment scale of the nursing work index (PES-NWI): The PES-NWI assesses various aspects of the nursing work environment. It includes 31 items, divided into five dimensions: nurse participation in hospital affairs (9 items), foundations for quality care (10 items), leadership and support from nurse managers (5 items), staffing and resource adequacy (4 items) and collegial nurse–physician relationships (3 items)26. Items are rated on a 4-point Likert scale (1, strongly disagree; 4, strongly agree). Work environments are classified as favourable, mixed or unfavourable based on the mean subscale scores. The Arabic-validated version showed an overall Cronbach’s alpha of 0.9327. The modified version for midwives reported a Cronbach’s alpha of 0.95 according to Alnuaimi and colleagues (2020), and in this study the scale had a Cronbach’s alpha of 0.89.

-

4.

Copenhagen burnout inventory (CBI): The CBI is a self-report tool with 19 items divided into three subscales: personal burnout, work-related burnout and client-related burnout28. Twelve items assess frequency on a 5-point Likert scale (0, never/almost never; 100, always), while seven items measure intensity on a 5-point scale (1, very low degree; 5, very high degree). Subscale scores range from 0 to 100, with higher scores indicating more severe burnout: 0–49 (no burnout), 50–74 (moderate burnout), 75–99 (high burnout) and 100 (severe burnout).

-

a.

The CBI demonstrated strong reliability among Jordanian midwives, with Cronbach’s alpha values of 0.89, 0.81 and 0.86 for personal, work-related and client-related burnout, respectively6, in this study the Cronbach’s alpha of the CBI scale was 0.82.

-

a.

-

5.

McCain and Marklin social integration (MMSI) Scale: The scale assesses social support from coworkers and supervisors29. It includes eight items to measure coworker support and six items to assess supervisory support. Responses are rated on a 5-point scale from 1 (strongly disagree) to 5 (strongly agree). Scores range from 8 to 40 for coworker support and from 6 to 30 for supervisory support. The instrument showed good reliability, with a Cronbach’s alpha of 0.93 among Arab nurses30, in the current study the Cronbach’s alpha among our participants was 0.91.

The instrument was piloted with ten midwives, who found it simple and easy to understand, with no suggestions for modifications.

Statistical analysis

Data analysis was conducted using SPSS version 2431 and AMOS software for Structural Equation Modelling32. The analysis followed these steps:

-

1.

Descriptive Statistics: Sociodemographic variables and questionnaire scores were summarised using frequencies, percentages, means and standard deviations.

-

2.

Screening of Preliminary Data: Missing values, normality (skewness and kurtosis), outliers and collinearity among the independent variables were assessed. Missing data were assessed using multiple imputation techniques.

-

3.

Validation of the Measurement Model: Confirmatory factor analysis was performed to test the validity and reliability of the latent constructs. Key indices such as composite reliability, average variance extracted and factor loadings were analysed to evaluate the adequacy of the measurement model33.

-

4.

Structural Equation Modelling (SEM): SEM was employed to test the proposed relationships between job satisfaction, work environment, social support and burnout. Model fit was evaluated using standard goodness-of-fit indices, including the chi-squared to degrees of freedom ratio (χ2/df), Comparative Fit Index (CFI), Tucker–Lewis Index (TLI) and Root Mean Square Error of Approximation (RMSEA)34.

Results

The study sample had a mean age of 37.91 years (SD = 7.95) and an average of 13.19 years of work experience (SD = 9.23). The mean monthly income was 787.32 JD (SD = 359.93) and the average number of family members was 5.19 (SD = 1.72). Most participants were married (69.8%), while smaller percentages were divorced (27.5%), widowed (1.6%) or single (1.1%). In terms of educational background, 50.0% held a bachelor’s degree, 37.4% had a diploma, 9.3% possessed a master’s degree or higher and 3.3% had a high diploma (a registered midwife with a year less than a bachelor’s degree). Regarding employment, 51.1% worked in public hospitals, 34.6% in maternal and child health clinics and 14.3% in private hospitals. The average total burnout score was 56.37 (SD = 8.46), with 52.2% experiencing moderate burnout, 45.1% high burnout and 1.6% reporting low burnout. The average satisfaction level was 85.70 (SD = 24.56), with most participants indicating moderate satisfaction (65.9%), followed by low satisfaction (23.1%) and high satisfaction (11.0%). The average work environment score was 77.40 (SD = 6.72), with 69.2% rating it as moderate and 30.8% indicating a need for improvement; no respondents reported a very positive or poor work environment. The average level of coworker and supervisor support was 46.9 (SD = 12.83). Specifically, 12.6% of respondents reported low support, 3.3% very poor support, 44.5% moderate support and 39.6% strong support (Table 1).

Table 2 presents the correlation matrix for the study variables, highlighting significant relationships among the demographic, occupational and psychosocial factors. Age showed significant positive correlations with marital status (r = 0.319, p < 0.01), income (r = 0.386, p < 0.01), number of family members (r = 0.284, p < 0.01) and work environment (r = 0.167, p < 0.05). However, it had a significant negative correlation with coworker and supervisor support (r =–0.148, p < 0.05). Marital status was positively correlated with experience (r = 0.652, p < 0.01) and burnout (r = 0.440, p < 0.01) but negatively correlated with work areas (r =–0.325, p < 0.01). Experience was positively correlated with income (r = 0.394, p < 0.01) and the number of family members (r = 0.245, p < 0.01) but negatively correlated with work areas (r =–0.398, p < 0.01) and coworker and supervisor support (r =–0.142, p = 0.056). Burnout showed a negative correlation with work areas (r =– 0.356, p < 0.01) and a positive correlation with experience (r = 0.363, p < 0.01). Additionally, burnout was negatively correlated with job satisfaction (r =–0.183, p < 0.01), work environment (r =–0.236, p < 0.01) and coworker and supervisor support (r =–0.163, p < 0.05). Job satisfaction had significant positive correlations with the work environment (r = 0.596, p < 0.01) and a negative correlation with coworker and supervisor support (r = − 0.211, p < 0.01). Both the work environment and job satisfaction had positive correlations with coworker support (r = 0.261, p < 0.01) and supervisor support (r = 0.184, p < 0.05), respectively.

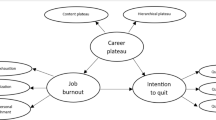

This study examined the relationships among burnout, job satisfaction, work environment and related factors using a structural equation model. Work environment and coworker & supervisor support positively influence job satisfaction (β = 0.57 and β = 0.25, respectively). Job Satisfaction negatively impacts burnout (β = −.18), indicating that higher job satisfaction reduces burnout levels (Fig. 1).

The final model (Table 3) showed an acceptable fit, with χ2/df = 2.763, RMSEA = 0.062, GFI = 0.821, AGFI = 0.802 and CFI = 0.88. Burnout was significantly influenced by multiple variables, with a squared multiple correlation (R2) of 0.33, indicating that 33% of the variance in burnout was explained by the model. Marital status was the strongest predictor of perceived work environment (β = 0.38, direct effect = 0.38, p < 0.001), followed by professional experience (β = 0.36, direct effect = 0.36, p < 0.001)), indicating that married and more experienced midwives reported more favourable perceptions of their work environment. The work environment had a negative direct effect on burnout (β = − 0.23, direct effect = − 0.23, p < 0.001) and a small indirect effect (− 0.02), resulting in a total effect of − 0.25 (p < 0.001). Job satisfaction also had a negative effect on burnout (β =–0.18, direct effect = − 0.18, p < 0.001), as did coworker and supervisory support (β =–0.16, direct effect = − 0.16, p < 0.05) with a small indirect effect (− 0.02), leading to a total effect of − 0.18 (p < 0.01). The work area was significantly negatively associated with burnout (β =–0.34, direct effect =–0.34, p < 0.001). Job satisfaction was significantly related to the work environment, age, experience and coworker and supervisory support, with an R2 of 0.41, indicating that 41% of the variance in job satisfaction was explained. The work environment had the largest direct positive effect on job satisfaction (β = 0.57, p < 0.001). Age had a moderate direct effect (β = 0.26, p < 0.001) and a small indirect effect (0.02), resulting in a total effect of 0.28 (p < 0.001). Experience (β = 0.18, direct effect = 0.18, p < 0.001) and coworker and supervisory support (β = 0.18, direct effect = 0.18, p < 0.001) also contributed positively, with the latter having a small indirect effect (0.02) and a total effect of 0.20 (p < 0.001). The work environment was influenced by coworker and supervisory support, age and work area, with an R2 of 0.18, indicating that 18% of the variance in the work environment was explained. Coworker and supervisory support had a significant positive effect (β = 0.25, p < 0.001). Age had a smaller positive effect (β = 0.15, p < 0.05), while the work area had a significant negative effect (β = − 0.24, p < 0.001) (Table 3).

Discussion

This study explores the relationship between the work environment, coworker and supervisor support, job satisfaction and burnout among midwives, with a focus on the mediating role of job satisfaction.

The results support the relevance of the JD-R model in a collectivist context, offering valuable insights into how organisational and individual factors affect midwives’ workplace outcomes. These factors directly influence job satisfaction, which subsequently impacts burnout levels, particularly within the collectivist cultural framework of Arab societies. These findings are essential for promoting midwives’ well-being and enhancing maternal and neonatal care. The data highlight that demographic factors and job resources, such as the work environment, are crucial determinants of job satisfaction, which mediates burnout levels.

The findings showed that demographics play a crucial role in shaping how individuals engage with their work environment and receive psychological and social support. Therefore, the alternative hypothesis (H₁), which posits that demographic factors (age, experience, marital status) significantly influence job resources (work environment and psychological/social support), was supported by the results in the SEM in Fig. 1.

The model shows a positive path coefficient (0.15) between age and work environment, indicating that older individuals tend to have a more favourable perception of their work environment. This may be attributed to senior healthcare workers having gained experience in developing resilience and coping mechanisms35. Our findings align with previous studies that suggested older and more experienced midwives report higher job satisfaction, as they can handle workplace challenges better and rely on long-established professional networks36. This is consistent with6, which found that Jordanian midwives aged 31–40 perceived their work environment negatively, affecting their ability to care for patients and increasing fatigue and burnout. Age appears to positively influence perceptions of job control and support, likely due to greater professional maturity and resilience. Sheehy et al. and Matthews et al. demonstrated similar findings36,37 , who similarly found that professional maturity and long-established support networks contribute to higher job satisfaction among midwives. However, our results also emphasize the cultural dimension: in Arab collectivist societies, seniority is often associated with social respect and stronger relational ties at work, amplifying the protective effect of age and experience against burnout7,17.

Conversely, a recent systematic review found that younger midwives are more likely to report burnout1. This may be due to higher expectations to perform at the same level as their more experienced colleagues, which can increase feelings of inadequacy and contribute to burnout1. These differing results suggest that the impact of age on job resources may vary depending on cultural and organisational contexts.

The results supported the second alternative hypothesis H₂: Work environment and psychological/support significantly influence job satisfaction. This was confirmed by the SEM, which showed that work resources, including the work environment and psychological support, have a significant impact on job satisfaction.

The model revealed a strong positive relationship (0.57) between the work environment and job satisfaction, consistent with recent findings1, who identified a significant link between supportive work environments and job satisfaction, highlighting that environments promoting autonomy, recognition and safety enhance satisfaction. While Albendín‐García et al. emphasised autonomy and recognition, the model presented here highlight the broader influence of the work environment1. Studies in Jordan also showed that poor work conditions in healthcare settings increase stress and reduce satisfaction, similar to the model’s findings5,6. These results are consistent across both collectivist and individualistic cultures, suggesting universal importance.

The model shows a positive relationship (0.18) between coworker/supervisor support and job satisfaction. This is consistent with Zadow et al. who found that psychological and social support from coworkers and supervisors significantly boosts job satisfaction, especially in high-stress fields like healthcare and education38. While coworker support has been found to have a stronger effect on satisfaction than supervisor support in previous studies1,4, the model does not distinguish between these roles, suggesting a broader, combined influence.

Furthermore, in collectivist societies, Huaman-Ramirez and Lahlouh, emphasised that coworker support is crucial due to the cultural emphasis on teamwork, which helps reduce both hierarchical and job content plateaus17.

Our study reinforces that job satisfaction acts as a buffer against burnout by enhancing emotional resilience. Albendín-García et al. also found that midwives with greater workplace autonomy and support experience lower emotional exhaustion1. This relationship is especially pronounced in collectivist cultures, where job satisfaction is deeply linked to social validation, teamwork, and the ability to meet communal expectations17,19. Therefore, burnout cannot be addressed solely through individual interventions, it requires system-level efforts that consider cultural context. These results align with the JD-R model, which views job satisfaction as a psychological resource that helps mitigate workplace stress and burnout38.

The SEM supports the third alternative hypothesis: H₃ (Job satisfaction mediates the relationship between work environment, psychological support and burnout), showing a statistically significant negative relationship (− 0.18) between job satisfaction and burnout. These results align with the JD-R model, which views job satisfaction as a psychological resource that helps mitigate workplace stress and burnout39. Similarly, previous research found that employees with higher job satisfaction are less prone to burnout, as satisfaction fosters emotional resilience and better stress management3. Additionally, research shows that workplace autonomy and recognition increase satisfaction and reduce emotional exhaustion1. However, the satisfaction–burnout relationship varies across contexts. In collectivist cultures, Huaman and colleagues emphasised the importance of relational factors like coworker and supervisor support in influencing satisfaction and burnout17, while in individualistic cultures, satisfaction is more strongly associated with personal growth and autonomy40. Contrasting findings suggest that the buffering effect of satisfaction lessens under high workload or unclear job roles, stressing the need for ongoing organisational support to sustain satisfaction over time41. These findings indicate that while job satisfaction is crucial in reducing burnout, other factors such as workload, role clarity and cultural differences should also be considered to fully understand the satisfaction–burnout relationship. This emphasises the need for interventions that improve job satisfaction while taking contextual and organisational factors into account.

The study supports the mediating role of job satisfaction in the relationship between job resources and burnout, aligning with previous research42. Job satisfaction helps reduce emotional exhaustion and disengagement by promoting a sense of purpose and achievement43 . For midwives, satisfaction often arises from positive workplace interactions and the ability to meet patient needs.

In Arab collectivist societies, job satisfaction goes beyond personal achievement, incorporating social approval and fulfilling communal expectations. Studies shows that healthcare professionals in collectivist cultures find identity and satisfaction in contributing to the well-being of their communities7. This further enhances the protective role of job satisfaction against burnout, highlighting its significance in designing effective workplace interventions.

Implications for Practice and Policy: These findings suggest that healthcare leaders should implement structured mentorship programs, especially for younger and less experienced midwives, and foster collaborative workplace cultures that reflect collectivist values. Regular peer support, fair workload distribution, and culturally tailored mental health services can improve job satisfaction and reduce burnout. From a policy standpoint, integrating organizational justice frameworks and continuous professional development programs focused on emotional resilience may promote workforce sustainability. These recommendations are especially relevant for health systems in the Arab region undergoing reform.

Limitations of the study

The results of this study should be interpreted with its limitations. For instance, this study used a cross-sectional design, which precludes definitive cause-and-effect relationships between organizational resources, burnout, and job satisfaction. Additionally, we recruited midwives with at least one year of experience, while this criterion was well justified. The voices of midwives with less than one year of experience were not echoed in this study, potentially affecting generalizability. Given the reported limitations, the participants of this study may not represent all Jordanian midwives. Furthermore, this study used self-report scales to collect the data, which may be subject to recall and social desirability biases. In a collectivist and hierarchical society such as Jordan, midwives may underreport burnout or dissatisfaction to avoid being seen as unprofessional or disloyal. Additionally, stigma around mental health and gendered expectations of emotional resilience may lead some participants to minimize negative experiences in their responses Nevertheless, our study was based on a robust model, which yielded several new insights and confirmed previous findings from other studies.

Conclusion and implication for practice

This study highlights the significant role of organisational and demographic factors in influencing job satisfaction, which mediates the reduction of burnout among midwives, particularly in the collectivist Arab cultural context. By addressing challenges in the work environment and promoting supportive workplace relationships, healthcare organisations can improve midwives’ well-being and reduce burnout. These efforts are essential for maintaining a sustainable midwifery workforce and ensuring quality maternal and neonatal care. The findings emphasise the importance of culturally tailored interventions to enhance workplace outcomes and support the long-term professional sustainability of midwives. Healthcare administrators in Jordan are encouraged to implement mentorship programs, ensure fair workload distribution, and offer mental health support tailored to midwives. Additionally, policy reforms could strengthen organizational justice, formalize peer support, and provide professional development that addresses the emotional demands of midwifery.

Data availability

The data supporting this study are available from the corresponding author upon reasonable request.

Abbreviations

- JD-R:

-

Job demands-resources

- H :

-

Hypothesis

- MMSS:

-

McCloskey/Mueller satisfaction scale

- PES-NWI:

-

Practice environment scale of the nursing work index

- CBI:

-

Copenhagen burnout inventory

- MMSI:

-

McCain and Marklin social integration

- SEM:

-

Structural equation modelling

- CFI:

-

Comparative fit index

- TLI:

-

Tucker–Lewis index

- RMSEA:

-

Root mean square error of approximation (RMSEA)

- SD:

-

Standard deviation

References

Albendín-García, L. et al. Prevalence, related factors, and levels of burnout among midwives: A systematic review. J. Midwifery Womens Health 66(1), 24–44 (2021).

Bakker, A. B. & Demerouti, E. Job demands–resources theory: Taking stock and looking forward. J. Occup. Health Psychol. 22(3), 273 (2017).

Tummers, L. G. & Bakker, A. B. Leadership and job demands-resources theory: A systematic review. Front. Psychol. 12, 722080 (2021).

Pires, M.L. The impact of supervisor support on employee-related outcomes through work engagement. in Eurasian Business Perspectives: Proceedings of the 29th Eurasia Business and Economics Society Conference. 2021. Springer.

Alnuaimi, K., Ali, R. & Al-Younis, N. Job satisfaction, work environment and intent to stay of Jordanian midwives. Int. Nurs. Rev. 67(3), 403–410 (2020).

Mohammad, K. et al. Personal, professional and workplace factors associated with burnout in Jordanian midwives: a national study. Midwifery 89, 102786 (2020).

Yaqoob, S. et al. Family or otherwise: Exploring the impact of family motivation on job outcomes in collectivistic society. Front. Psychol. 14, 889913 (2023).

Bourezg, M., et al., Exploring the path to job satisfaction among women in the Middle East: a contextual perspective. Gender in Management: An International Journal, 2024

Bakker, A. B. & de Vries, J. D. Job demands-resources theory and self-regulation: New explanations and remedies for job burnout. Anxiety Stress Coping 34(1), 1–21 (2021).

Tomaszewska, K. et al. Areas of professional life and job satisfaction of nurses. Front. Public Health 12, 1370052 (2024).

Ee, E. Job satisfaction among nurses working in Mansoura university hospital: Effect of socio-demographic and work characteristics. Egypt. J. Occupat. Med. 42(2), 227–240 (2018).

Al-Amer, R., Depression and self-care in Jordanian adults with diabetes: The POISE study. 2015, University of Western Sydney (Australia)

Al-Eraky, M. M. & Chandratilake, M. How medical professionalism is conceptualised in Arabian context: A validation study. Med. Teach. 34(sup1), S90–S95 (2012).

Naseem, T. et al. Corporate social responsibility engagement and firm performance in Asia Pacific: The role of enterprise risk management. Corp. Soc. Responsib. Environ. Manag. 27(2), 501–513 (2020).

Scott, I. and J. Spouse, Practice based learning in nursing, health and social care: Mentorship, facilitation and supervision. 2013: John Wiley & Sons.

Henderson, K. & Loreau, M. A model of sustainable development goals: Challenges and opportunities in promoting human well-being and environmental sustainability. Ecol. Model. 475, 110164 (2023).

Huaman-Ramirez, R. & Lahlouh, K. Understanding career plateaus and their relationship with coworker social support and organizational commitment. Public Org. Review 23(3), 1083–1104 (2023).

Ballout, S. People of Arab Heritage. In Handbook for Culturally Competent Care 97–137 (Springer, 2024).

Al-Worafi, Y. M. Interprofessional Practice in Developing Countries. In Handbook of Medical and Health Sciences in Developing Countries: Education, Practice, and Research 1–36 (Springer, 2024).

Wu, F. et al. The relationship between job stress and job burnout: the mediating effects of perceived social support and job satisfaction. Psychol. Health Med. 26(2), 204–211 (2021).

Al-Worafi, Y.M., Burnout Among Healthcare Professionals in Developing Countries. Handbook of Medical and Health Sciences in Developing Countries: Education, Practice, and Research, 2023: p. 1–29

Otoum, R., et al., Mediating Role of Job Satisfaction in the Relationship between Job Performance and Organizational Commitment Components: A Study among Nurses at One Public University Hospital in Malaysia. Malaysian Journal of Medicine & Health Sciences, 2021(3)

Popoola, S. O. & Fagbola, O. O. Work motivation, job satisfaction, work-family balance, and job commitment of library personnel in Universities in North-Central Nigeria. J. Acad. Librariansh. 49(4), 102741 (2023).

Ministry of Health Jordan. Ministry of Health annual statistical book,. 2024 [cited 2025 15/7]; Available from: https://www.moh.gov.jo/ebv4.0/root_storage/ar/eb_list_page/%D8%A7%D9%84%D8%AA%D9%82%D8%B1%D9%8A%D8%B1_%D8%A7%D9%84%D8%A7%D8%AD%D8%B5%D8%A7%D8%A6%D9%8A_%D8%A7%D9%84%D8%B3%D9%86%D9%88%D9%8A-2024_(1).pdf.

Mueller, C. W. & Mccloskey, J. C. Nurses’ job satisfaction: A proposed measure. Nurs. Res. 39(2), 113–116 (1990).

Lake, E. T. Development of the practice environment scale of the nursing work index. Res. Nurs. Health 25(3), 176–188 (2002).

Al-Hamdan, Z., Manojlovich, M. & Tanima, B. Jordanian nursing work environments, intent to stay, and job satisfaction. J. Nurs. Scholarsh. 49(1), 103–110 (2017).

Kristensen, T. S. et al. The copenhagen burnout inventory: A new tool for the assessment of burnout. Work Stress. 19(3), 192–207 (2005).

McCloskey, J. C. Two requirements for job contentment: Autonomy and social integration. Image: J. Nurs. Sch. 22(3), 140–143 (1990).

Nazari, S., A. Zamani, and P. Farokhnezhad Afshar, The relationship between received and perceived social support with ways of coping in nurses. Work, 2024(Preprint): p. 1–9

IBM, IBM SPSS statistics for windows, in Armonk, New York, USA: IBM SPSS. 2019. p. 119

IBM, IBM AMOS statistics for Windows, in Armonk, Ny: IBM Corp. 2016

Widaman, K.F. and J.L. Helm, Exploratory factor analysis and confirmatory factor analysis. 2023

Stein, C.M., N.J. Morris, and N.L. Nock, Structural equation modeling. Statistical human genetics: Methods and protocols, 2012: p. 495–512

McGuire, C.L., Preparing Future Healthcare Professionals: The Relationship Between Resilience, Emotional Intelligence, and Age. 2021

Matthews, R. et al. Factors associated with midwives’ job satisfaction and experience of work: A cross-sectional survey of midwives in a tertiary maternity hospital in Melbourne. Aust. Women Birth 35(2), e153–e162 (2022).

Sheehy, A. et al. Understanding workforce experiences in the early career period of Australian midwives: Insights into factors which strengthen job satisfaction. Midwifery 93, 102880 (2021).

Zadow, A. J. et al. Predicting new major depression symptoms from long working hours, psychosocial safety climate and work engagement: a population-based cohort study. BMJ Open 11(6), e044133 (2021).

Bakker, A. B. & Demerouti, E. The job demands-resources model: State of the art. J. Manag. Psychol. 22(3), 309–328 (2007).

Chirkov, V. et al. Differentiating autonomy from individualism and independence: a self-determination theory perspective on internalization of cultural orientations and well-being. J. Pers. Soc. Psychol. 84(1), 97 (2003).

Dodanwala, T. C., Shrestha, P. & Santoso, D. S. Role conflict related job stress among construction professionals: The moderating role of age and organization tenure. Constr. Econ. Build. 21(4), 21–37 (2021).

Faragher, E. B., Cass, M. & Cooper, C. L. The relationship between job satisfaction and health: a meta-analysis. Occup. Environ. Med. 62(2), 105–112 (2005).

Judge, T. A. et al. Job attitudes, job satisfaction, and job affect: A century of continuity and of change. J. Appl. Psychol. 102(3), 356 (2017).

Acknowledgements

The authors sincerely thank all the midwives who participated in this study for their time and effort.

Funding

No funding was received for this study.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

R.A., N.A., and M.A.: Data acquisition, data analysis, and drafting the manuscript, methodology. E. A., A.M.T., A.A., and Z.A.: Validation of the analysis, preparation of figures and tables, and drafting the manuscript. A.A., and W.O.: Drafting the manuscript, validating the methodology, and presenting the results. S.R.: Supervised, writing the final draft, and reviewed the manuscript.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Ethical approval and consent to participate

The study was approved by the Institutional Review Board at the Jordan University of Science and Technology (ethics number MBA/IRB/14601) and conducted in accordance with the Declaration of Helsinki.

Consent for publication

Written informed consent was obtained from all participants involved in the study.

Additional information

Publisher’s note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if you modified the licensed material. You do not have permission under this licence to share adapted material derived from this article or parts of it. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Al-Amer, R., Alrida, N.A., Abuadas, M.H. et al. Job satisfaction as a mediator between organizational factors, work environment, and burnout among Jordanian midwives. Sci Rep 15, 34881 (2025). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-17162-3

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-17162-3