Abstract

This study aimed to explore the impact and the effectiveness of interventions based on the Interaction Model of Client Health Behavior on the self-care behavior of chronic heart failure patients. Using convenience sampling, 80 chronic heart failure patients who met the inclusion and exclusion criteria were selected from the Cardiovascular Department of a tertiary hospital in Henan Province from January to June 2023. The first and second wards were randomly assigned to control and intervention groups, with the first ward serving as the control group and the second ward as the intervention group, each consisting of 40 cases. The control group received routine care, and the intervention group was subjected to a self-care behavior intervention scheme based on Interaction Model of Client Health Behavior. The intervention lasted for three months. Then, various indicators of the patients were assessed. The intervention group had significantly higher self-care behavior levels than the control group, significantly lower levels of disease perception than the control group, and the quality of life scores of the intervention group was lower than that of the control group. The difference in readmission rates between the two groups was statistically significant. The intervention scheme based on Interaction Model of Client Health Behavior can enhance self-care behavior in chronic heart failure patients, improve their disease perception, ameliorate their quality of life, and further decline readmission due to disease recurrence or complications.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

With the advancement of cardiovascular specialized medical technology, the treatment concept for heart failure has evolved from primarily symptomatic drug therapy to comprehensive treatment focusing on managing underlying cardiovascular diseases and other risk factors. Despite the use of medications and device implants that have somewhat delayed the progression of chronic heart failure (CHF), patients still face a variety of distressing symptoms, such as dyspnea and edema. These symptoms significantly impact their daily lives and physical and mental health, reducing their overall quality of life.

Self-care refers to the proactive and voluntary engagement of individuals in activities aimed at improving their health status. For CHF patients, self-care holds crucial significance. However, a study1 investigating 6,124 elderly CHF patients across 102 hospitals found that their self-care levels were generally mediocre, especially in symptom management and follow-up compliance. Additionally, the readmission rate within 30 days after discharge was as high as 28%2. It has been3,4 indicated that patients maintaining good self-care behaviors is pivotal in preventing and controlling disease progression, predicting their quality of life, and reducing readmission and mortality rates. Furthermore, CHF often recurs, leading to repeated symptoms of heart failure. Many patients have insufficient disease knowledge5, low disease awareness6, and a weak sense of personal responsibility7, making it difficult for them to accurately identify worsening symptoms. This further impacts their quality of life and undermines their confidence in self-care.

Previous research has shown that interventions based on scientific theories usually overlook patients’ individual characteristics, their understanding of the disease, and their emotional and psychological states. Additionally, the importance of nurse-patient interaction is easily undervalued. Comprehensive interaction not only reflects patients’ intrinsic sense of responsibility and potential for active participation in disease management but also mobilizes their subjective initiative.

The interaction model of client health behavior (IMCHB)8, developed by American nurse Cheryl Cox in the 1980s, integrates four theoretical models from the perspective of health behavior. This model delineates a dynamic and multi-angle process aimed at stimulating patient health responsibility and promoting positive health outcomes. The model consists of three parts: patient characteristics, interactions with healthcare providers, and health outcomes. Among them, interactions between patients and healthcare providers are dominant, influenced by four elements: health information, professional skills, emotional support, and decision-making control. They collectively impact the treatment process. Unlike traditional theories that emphasize healthcare providers diagnosing and initiating treatment, IMCHB recognizes that patients often have limited knowledge about their disease, which necessitates reliance on more comprehensive healthcare expertise. The model emphasizes the diversity and targeted nature of nursing interventions to meet individual patient needs. Its core philosophy is to actively guide and encourage patients to utilize their own initiative, thereby promoting better health outcomes. This model emphasizes the importance of patients honestly expressing their internal needs to healthcare providers, promoting active discussion of diagnostic and treatment plans, and sharing disease information. It encourages patients to clearly and explicitly articulate their viewpoints and attitudes, actively participating in their disease management. This approach not only highlights patient engagement but also fully leverages their vital role in health education. Interventions based on IMCHB differ from other single or fixed intervention schemes. Since patients with chronic heart failure often have low levels of self-care, this model can be used to explore and validate the various issues that heart failure patients encounter in terms of self-care.

Therefore, this study aimed to construct an intervention scheme based on IMCHB for CHF patients, apply this scheme, and evaluate its effectiveness in self-care behavior, disease perception, and quality of life among CHF patients, thereby promoting their disease outcomes.

Method

Design

Single-center quasi-experimental study.

Subject and sample size

Inclusion criteria:

-

Patients diagnosed with CHF according to the New York Heart Association (NYHA) functional classification of II-III.

-

Age ≥ 18 years, stable condition, clear consciousness, normal language and written expression abilities, no communication barriers, able to understand and accurately complete questionnaires.

-

Informed consent and voluntary participation.

Exclusion criteria:

-

Patients with complications such as renal or hepatic insufficiency, a history of mental disorders, or currently experiencing mental disorders, or critically ill.

Dropout criteria:

-

Patients whose condition deteriorates significantly during the intervention and are deemed unsuitable to continue education.

-

Patients who transfer to another hospital during the intervention.

-

Patients who participate in similar studies midway through.

The sample size was calculated using the independent sample means comparison. The two-tailed test was adopted, with α = 0.05, β = 0.1, and a sample size of 36 per group. Accounting for a 10% dropout rate, each group eventually included 40 patients. This study set the first cardiology ward as the control group and the second ward as the intervention group.

Ethical approval was obtained from the Ethics Committee. All patients voluntarily participated in the study and signed informed consent.

Data collection

The general information survey, Heart Failure Self-Care Index, and Brief Illness Perception Questionnaire were collected before intervention and at 1 and 3 months post-intervention, respectively. Readmission rates were collected uniformly at the end of the intervention, and post-discharge data were obtained during follow-up visits.

The staged intervention draft based on IMCHB was constructed using literature analysis. In order to ensure scientificity and practicality, 15 experts were selected for two rounds of consultations, and eight CHF patients underwent pilot testing to verify feasibility and effectiveness. Based on feedback, the initial draft was further refined to produce the final intervention plan.

Intervention methods for the control group

-

1.

Admission Education: Comprehensive education provided by responsible nurses upon admission, covering ward environment, attending physician information, disease-related knowledge, medication precautions, and safety education.

-

2.

Routine Health Education: 24-hour fluid intake and output records, daily weight and measurement methods, sodium intake control, and medication efficiency and side effects.

-

3.

Establishment of IMCHB Nursing Team: The intervention team consists of one attending physician, two graduate nursing students, one head nurse, and three nursing team members, each with over three years of cardiology experience and at least a bachelor’s degree. The head nurse is responsible for team member training, mainly involving CHF knowledge. The attending physician and graduate students are in charge of literature review and nursing intervention development. The nurses implement interventions and formulate the intervention plan based on IMCHB.

-

4.

Appropriate Lifestyle Interventions: Based on CHF patient needs, low-sodium and low-fat diet and appropriate micronutrient supplementation are provided to the intervention group. Fluid intake is managed according to the cardiac function of patients. Regular aerobic exercise, such as walking, is recommended. The patients are instructed to rest in bed in a semi-recumbent position and reminded to turn over frequently. During the peak period of respiratory system diseases, they are advised to pay attention to keeping warm and prevent catching a cold.

-

5.

Psychological Care: Regarding diseases related to negative emotions in patients, based on their psychological characteristics, provide effective psychological care and maintain timely communication with patients and their families to identify and resolve issues promptly. Seek the feedback of patients on IMCHB-based nursing.

-

6.

Discharge Education: One day before discharge, collaborate with patients to create follow-up plans detailing visit times and content. On the discharge day, the responsible nurse emphasizes to patients in the ward the importance of monitoring disease symptoms, balancing diet, and exercising scientifically. Post-discharge, utilize structured telephone follow-up over three months, every two weeks, and guide patients on scheduling regular check-ups (notifying patients a day in advance regarding any precautions).

Intervention methods for the intervention group

During hospitalization.

First session: Acquire disease-related information, and enhance patient disease awareness. Within 24 h of admission, conduct relevant assessments for all patients. The intervention begins on the 3rd day of admission.

Class interaction sessions are arranged as follows:

-

1.

Theoretical Lecturing: Conduct interactive health information sessions. Provide visually appealing CHF health education manuals to patients, explaining the concept of self-care, its importance, etiologies, risk factors, symptoms, medication knowledge, and lifestyle habits in an easy-to-understand manner, ensuring patients comprehensively and systematically grasp the relevant knowledge.

-

2.

Panel Discussion and Interactive Activity: Organize group discussions during 4:00 and 5:00 PM for 30–40 min (adjustable based on the comprehension of patients). Include interactive “Q&A” sessions to deepen patients’ understanding and memory of disease knowledge. Utilize tiered tutoring strategies for patients with weaker learning abilities to ensure full comprehension and mastery.

Second session: Address emotional needs and foster self-care confidence. The intervention starts from the fourth to fifth day of admission, generally in the afternoon from 4:00 PM, lasting 25–30 min. Use open-ended questions for patients: “What activities would you like to do with your family?” “How do you think your health will affect it?” and “How do you perceive the impact of your health on these relationships?”

-

1.

Positive Case Studies and Self-Relaxation Techniques: Soothing music, meditation, abdominal breathing combined with attention diversion techniques, and aerobic warm-ups for relaxation.

-

2.

Sharing Inner Voices: Encourage patients to open up and share the challenges and troubles they have faced. Nurses patiently listen, providing emotional guidance and support.

-

3.

Peer Interaction and Support Education: Invite patients with good nursing compliance or their family members to share their self-care experiences and key elements, harnessing the model effect and inspiring confidence and motivation in self-care.

-

4.

Encourage family members to support patients, affirm their positive behavior, discuss how to rectify bad behavior and errors, discover their potential and strengths, and promote their recovery and growth.

Third session:

Professional Skills: The intervention begins on the fifth day of admission, lasting 25–30 min.

-

1.

Building on initial theoretical lectures, the emphasis shifts to professional skill training. Specifically, this covers the following aspects:

-

a.

Symptom Assessment and Identification: Instruct patients to accurately assess primary symptoms, such as dyspnea, lower limb edema, and sleep conditions, ensuring they can quickly identify and cope with discomfort. For example, press the soles of the feet or legs with thumbs, and the presence of an impression indicates swelling; weight gain (a gain of > 2 kg in three days denotes edema) needs prompt treatment.

-

b.

Basic Vital Sign Measurement: Respiratory, pulse, blood pressure, and blood glucose. Understand the measurement methods and times for abdominal circumference and weight. Underline precautions for water and salt intake, diet, and exercise.

-

a.

-

2.

Interactive session with prizes for guessing knowledge about heart failure disease: Prepare a series of question cards to conduct an interactive quiz session in an appealing Q&A format. Patients compete to answer quickly. Those who answer correctly obtain the chance to win small prizes. After the interactive session, medical workers provide professional commentary and summarize the quiz content. The entire process will last approximately 20 min.

-

3.

Scenario Interpretation and Interaction: Accurately identify symptoms of heart failure and provide on-site intensive training in first aid knowledge and skills. Key aspects include how to self-rescue and relieve symptoms of heart failure during an attack; particularly, highlight emergency knowledge and skill training for the family members of elderly patients and enhance memory retention through review and association.

Fourth session:

Decision-Making Control: The intervention starts one day before the discharge, lasting 25–30 min.

-

1.

Assessing Patient Decision-Making Needs: Understand the past decision-making experiences and current concerns of patients thoroughly. Encourage them to set clearly phased goals. For example, patients can set specific daily goals such as “Every morning at 7:00 AM, I will set an alarm clock, get up on time, and use tools like a weight scale and soft ruler to measure weight, abdominal circumference, and ankle circumference, and record these data in detail;” “Because I sometimes forget to take medication, I will place the medication prominently at the bedside.” Encourage family members to participate in this process and offer necessary supervision and support. Use auxiliary tools as needed and remind patients to adhere to medication guidelines (such as alarms, dose boxes, and phone reminders). Underline the explanation of medication treatment and side effects.

-

2.

Scenario Guidance: Guide patients to examine current detrimental behaviors and habits to promote self-reflection and behavior improvement. Based on this, tailor short and long-term intervention plans according to their individual capabilities and medical history.

-

3.

Encourage patients to express their emotions to family members. Instruct family members to play a positive role and motivate them to actively participate in disease management learning.

Post-hospitalization intervention

Within 48 h after discharge, contact patients. Follow-up appointments are flexible, varying with patients’ condition and concerns. The duration is typically around 20 min.

-

1.

Follow-Up:

-

Self-care status (daily habits and the presence of conditions during heart failure attacks, such as lower limb edema and shortness of breath).

-

Current unmet needs.

-

Potential re-hospitalization and timing.

-

Daily reminders and regular check-ups are uploaded to platforms via WeChat or public accounts (for three months).

-

-

2.

Guidance Standard:

Medical personnel conduct phone follow-ups within one week, one month, and three months after discharge, including self-care (daily habits and the presence of conditions during heart failure attacks, such as lower limb edema and shortness of breath), current unmet needs, and potential re-hospitalization and timing.

Home Continuous Supervision: Encourage patients to monitor and record their conditions during follow-ups, assign corresponding homework based on assessments, strengthen doctor-patient communication, comprehensively understand their conditions, and provide personalized psychological care. Present content in an understandable and acceptable format for patients to learn repeatedly, compensating for the forgetfulness common in large classroom settings. At the next follow-up, inquire about unresolved issues from the last one and consolidate, ensuring the effectiveness of the intervention and promoting the formation and continuation of health behavior.

The control group and the intervention group adopted different intervention measures at different stages. Please refer to Table 1 for details.

Survey instrument

General information

Researchers compiled the questionnaire based on study objectives, literature review, and input from clinical nursing experts. The general information includes demographic and disease-related data. Demographic information covers age, gender, education level, payment method, and marital status. Disease-related data encompasses the classification of cardiac functions and the presence of comorbidities.

Chinese version of the self-care of heart failure index (SCHFI)

The Chinese version of the SCHFI was developed by Riegel et al.9 and revised by Chenwei et al.10, encompassing three dimensions and 22 items. Among these items, there are 10 for self-care maintenance, totaling 40 points, 6 for self-care management, totaling 24 points, and 6 for self-care confidence, totaling 24 points. Higher scores indicate better self-care behaviors. The total scale has a Cronbach’s alpha coefficient of 0.853.

Brief illness perception questionnaire (BIPQ)

The BIPQ, developed by Broadbent et al.11, consists of nine items. It evaluates disease cognition (five items), emotions (two items), and understanding of the disease (one item). The score totals 80. The higher it is, the more negative the perception of the illness is. The questionnaire’s Cronbach’s alpha coefficient is 0.77.

Minnesota living with heart failure quality of life questionnaire (MLHFQ)

The MLHFQ was formulated by Jay Cohn and translated by Zhu Yanbo12. It comprises 21 items. Each item is scored from 0 to 5, totaling 105. Lower scores indicate higher quality of life for patients. The internal consistency reliability coefficient is 0.896.

Unplanned readmission

It counts the unplanned readmission of patients within three months after discharge.

Ethics approval and consent to participate

The study was conducted in accordance with the Declaration of Helsinki and was approved by the Medical Ethics Committee of Henan University (Ethics No.HUSOM2023-441). All patients give informed consent and participate voluntarily.

Result

Comparison of general data

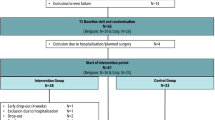

The study included 80 patients, with 40 each in the intervention and control groups. During the intervention, three patients in the control group did not participate in hospital follow-ups, one patient in the intervention group experienced worsened conditions, and another withdrew. The final analysis comprised 37 cases in the control group and 38 in the intervention group. Baseline data between the two groups showed no statistically significant differences (P > 0.05), indicating comparability (Table 2).

Comparison of self-care behavior

The total scores of the self-care index for the two groups conformed to normality and homogeneity of variance and were assessed using the independent sample t-test and repeated measures analysis of variance. However, each dimension did not follow a normal distribution. Therefore, the rank-sum test and generalized estimation equations were employed. Analysis of the generalized estimation equations revealed that in the dimensions of self-care maintenance, management, and confidence, there were statistically significant differences in time, inter-group, and interaction effects between the two groups (P < 0.05).

The results of inter-group comparisons showed that one month after intervention, the self-care index of the intervention group (53.00 ± 2.48) was significantly higher than that of the control group (48.38 ± 2.53), with a statistically significant difference (t = − 7.983, P < 0.001). Three months after the intervention, the self-care index score of the intervention group (55.74 ± 2.96) was higher than that of the control group (49.51 ± 1.69), with a statistically significant difference (t = − 13.323, P < 0.001). See Tables 3 and 4 for details.

Comparison of disease perception

Repeated measures analysis of variance showed P = 0.49 > 0.05, satisfying “sphericity.” There were statistically significant differences in time, inter-group, and interaction effects between the disease perception scores of the two groups (F (time) = 105.682, F (inter-group) = 10.896, F (interaction) = 16.924, P < 0.001). This represents that the scores increase with time, demonstrating the time effect. Differences are statistically significant. Moreover, scores differ significantly across time points due to group differences, indicating the interaction effect between intervention factors and time. Notably, one and three months post-intervention, the disease perception scores of the intervention group were lower than those of the control group, with statistically significant differences (P < 0.05), as shown in Table 5.

Comparison of quality of life

Repeated measures analysis of variance presented P = 0.002 < 0.05, indicating non-sphericity. Corrected results were used. The two groups exhibited a significant time effect in scores of the quality of life (F (time) = 66.511, P < 0.001), a profound inter-group effect (F (inter-group) = 7.629, P < 0.001), and an interaction effect between time and inter-group (F (interaction) = 15.120, P < 0.007). One month and three months after intervention, the scores of the quality of life in the intervention group were lower than those in the control group, with statistically significant differences (P < 0.001), as shown in Table 6.

Comparison of readmission rate

Three months after discharge, the unplanned readmission rate in the intervention group (10.53%) was lower than in the control group (29.73%), with statistically significant differences (P < 0.05), as shown in Table 7.

Discussion

Intervention schemes based on IMCHB can improve self-care levels in CHF patients

Self-care behavior plays a pivotal role in disease management for CHF patients, serving as the cornerstone for symptom control and halting disease progression. Inadequate self-care behavior will evidently augment the risks of hospitalization, morbidity, and mortality among CHF patients13. The average hospital stay for patients is approximately six days, which is relatively short. After transitioning from hospital care to home, where clinical treatment is no longer available, active engagement in self-care practices becomes especially crucial. This aligns with findings from Ran Xiaojing et al.14, indicating that over time, the scores of self-care behavior tend to grow, along with more pronounced improvements observed in the intervention group compared to the control group. For instance, theoretical lectures, sharing of typical cases, interactive scenarios, and panel discussions during hospitalization enhance patients’ comprehension of disease-related knowledge. Additionally, activities such as contests on heart failure knowledge, combined with interesting Q&A sessions and live demonstrations, favor patients grasping relevant skills more intuitively. Furthermore, medical staff should encourage active participation among patients, promote collaborative supervision through peer support and sharing experiences, focus on cases where substandard self-care behavior leads to disease exacerbation, and engage patients in deep discussions to stimulate their intrinsic motivation, thus yielding active improvements in self-care practices. The model’s advantages in enhancing self-care include implementing a nursing intervention program based on the IMCHB theory, focusing on three aspects: self-care management, self-care maintenance, and self-care confidence. The intervention targets patients’ symptom recognition and perception, daily behavior monitoring and maintenance, timely medical consultation, and emotional regulation. A multifaceted nursing intervention approach was adopted, characterized by its richness and flexibility, facilitating patient acceptance and encouraging a transition from passive to active learning, thereby enabling patients to acquire theoretical knowledge and practical skills related to self-care. Moreover, patients’ emotional well-being is emphasized. Therefore, patients’ self-care levels apparently advanced three months after the intervention.

Intervention schemes based on IMCHB can improve disease perception levels in CHF patients

Disease perception reflects patients’ cognitive evaluation and understanding of their disease symptoms and medical conditions, which is vital for identifying and defining symptoms and recognizing their severity15,16. For CHF patients, long-term affliction often results in inadequate or exaggerated disease perceptions15,16. Such perceptions directly impact individual disease outcomes. Higher disease perceptions can lead to more severe negative perceptions, potentially undermining the treatment compliance and confidence of patients17. Therefore, prioritizing and understanding patients’ disease perceptions is essential for enhancing their treatment compliance. The intervention Scheme in this study incorporates various forms, such as theoretical lectures, group discussions, and online Q&A, to elucidate the importance of perception levels through practical examples. Deep interactions between medical staff and patients, including explanations and analysis of questions, can effectively leverage nurse-patient communication to convey correct disease cognition, correct misconceptions, and guide patients to adopt a positive perspective toward their illness. Thus, after one month and three months of intervention, significant improvements were observed in patients’ disease perception levels. This demonstrates the effectiveness of intervention programs based on IMCHB in enhancing patients’ disease perception.

Intervention schemes based on IMCHB can enhance quality of life for CHF patients

Quality of life is an important dimension for assessing the overall status of CHF patients. Despite advances in medical technology, the prognosis for CHF patients remains concerning, significantly impacting their health-related quality of life. Simultaneously, various unfavorable factors within families and society impede patients from fulfilling their roles effectively18. Research has shown that CHF patients universally believe that improving their quality of life is equally crucial to extending life expectancy19.

This study found that after implementing IMCHB-based nursing interventions for one month and three months, there were statistically significant improvements in the total scores of the quality of life scale in time, inter-group, and interaction effects of the two groups (p < 0.05). Over time, both groups ameliorated the quality of life, which was more significant in the intervention group. It not only confirms the effectiveness of IMCHB-based nursing interventions in elevating the quality of life for patients but also suggests that the influence is prolonged.

Meanwhile, as patients stabilized post-discharge, their quality of life steadily improved. It agrees with the outcomes of Ye Lingyan et al.20. Throughout the nursing process, research team members gained deep insights into the needs and concerns of patients. The following measures were implemented: Initially, during the early stages of hospitalization, targeted nursing intervention plans were developed through communication with patients and their families. These plans progressively provided health information and guidance on professional skills, stimulating active participation among patients and their families. From hospitalization to continued home supervision post-discharge, patients received professional instruction.

Additionally, on the day of discharge, patients were provided with health diaries to record blood pressure, blood sugar, weight, and other conditions. After discharge, they were invited to join the “Care from the Heart” WeChat group, where professional heart failure-related health knowledge and life skills were shared at least 2–3 times per week. Encouraging active interactions within the group, sharing learning experiences and insights, and establishing sessions for addressing professional queries by senior nurses available online were parts of the initiative.

Intervention schemes based on IMCHB can reduce readmission rates in CHF patients

Readmission rates and the time interval post-discharge have long been a focus in cardiovascular medicine worldwide21. However, hospital stay is a potential risk factor. Its association with the readmission risk of heart failure remains opaque22,23. It is noteworthy that when CHF patients are readmitted, their cardiac function often further deteriorates, potentially accompanied by severe symptoms such as dyspnea, fatigue, insomnia, and anxiety. This not only burdens patients and their families economically but also undermines patients’ confidence in recovery and exacerbates their psychological barriers24. Therefore, refined management of CHF patients is critically important. Such management enhances patients’ quality of life and clinical outcomes and holds profound significance in diminishing healthcare costs. Upon implementing the intervention plan based on IMCHB, this study found that patients in the intervention group had lower readmission rates at three months post-discharge than the control group. It indicates that IMCHB-based nursing interventions can effectively reduce readmission rates in CHF patients, which is consistent with Geng Huijun et al.25. The reasons may be that IMCHB-based nursing interventions adhere to patient-centered, focusing on nurse-patient interactions, engaging family members in cooperative care, and leveraging peer support and experience sharing. This strategy enhances patients’ initiative and motivation in disease management, helping them build confidence in overcoming their illness. Furthermore, guiding patients in proper medication usage, symptom recognition, and monitoring empowers them with effective and sustained health management skills. Patients tangibly experience diverse care and support from various societal systems, which aids in their gradual acquisition of disease-specific knowledge, refinement of self-care behavior, and enhancement of self-care abilities, thus improving physical symptoms and declining readmission rates.

Characteristics of nursing interventions based on IMCHB and their value in clinical applications

The philosophy of nursing interventions based on IMCHB consistently sticks to the foundation of “nurse-patient interaction,” closely aligned with the learning needs of the patients. The IMCHB comprises three components: patient characteristics, interactions with healthcare providers, and health outcomes. Patient characteristics form the foundation for developing nursing interventions; interactions with healthcare providers are the core of the model; and health outcomes reflect the overall effectiveness of nurse-patient interactions. In this model, medical staff are no longer mere executors but instructors and supporters of patients. The core of this model is to identify individual differences and uniqueness among patients, thereby stimulating their intrinsic motivation and subjective initiative and encouraging active participation in nursing practices. Moreover, it integrates scientific and sound health education content and formats into targeted educational programs for patients. Subsequently, patients convert from passive to active learning, enabling them to actively acquire disease knowledge. This approach helps patients further accept and understand health education provided by nurses, thereby enhancing patients’ self-care behavior. Simultaneously, patients not only manage their health conditions better but also experience dignity and value.

This model offers a patient-centered, interaction-focused theoretical framework for nursing practice, providing valuable guidance: First, emphasizing individualized care requires comprehensive, in-depth, and dynamic assessment of patients before formulating any care plan; second, the effectiveness of care implementation heavily depends on nurse-patient communication, where nurses serve not only as information providers and technical operators but also as collaborators, supporters, and enablers; third, improvements in health outcomes are not solely the result of medical interventions but also the culmination of patient characteristics and high-quality nurse-patient interactions. Therefore, a self-care behavior program for patients with chronic heart failure based on the IMCHB theory can be approached from the perspective of nurse-patient interaction, centering on the patient, and actively engaging patients in the disease management process. This allows for the development of more comprehensive health management strategies tailored to individual patient needs. Backed by science, it is feasible while demonstrating practical value in clinical practice. Increasing studies have confirmed that this model profoundly ameliorates patients’ self-care behavior, advances their quality of life, and lessens healthcare costs. It not only aligns with the developmental trend of modern nursing concepts but also holds significant clinical application value, warranting further promotion and application.

Conclusion

Intervention schemes based on IMCHB can enhance self-care behavior, improve disease perception levels, and elevate the quality of life for CHF patients. Furthermore, they can effectively drop the readmission induced by disease recurrence or complications. This provides a theoretical basis for clinical nursing personnel in their care of CHF patients. This study has the following limitations. Firstly, this study is a single-center investigation, involving patients from only one hospital, which presents certain limitations. To enhance the generalizability and representativeness of the research, future phases could expand the sample size to include hospitals from different regions and of varying levels, thereby increasing the universality and robustness of the findings. Secondly, due to time constraints, the follow-up assessment of the intervention’s long-term effects was conducted at 1 and 3 months post-intervention. In future studies, it is recommended to consider extending the follow-up period to better evaluate the long-term impact of the intervention based on the IMCHB model on self-care behaviors and overall health outcomes. Finally, in future research, it is recommended to incorporate a more diverse patient cohort to evaluate how different demographic factors influence self-care behaviors and the effectiveness of interventions.

Data availability

The original contributions presented in the study are included in the article, and further inquiries can be directed to the corresponding author.

References

Li, D. et al. Survey on self-management status and influencing factors of elderly patients with chronic heart failure. Chin. Nurs. Manag. 20 (03), 360–366 (2020).

Senecal, L. E. & Jurgens, C. Y. Persistent heart failure symptoms at hospital discharge predicts 30-Day clinical events. J. Cardiovasc. Nurs. 37 (2), 158–166 (2020).

Sabine, A. et al. mHealth education interventions in heart failure. Cochrane Database Syst. Rev. 7 (7), CD011845 (2020).

Tinoco, J. D. et al. Effectiveness of health education in the self-care and adherence of patients with heart failure: a meta-analysis. Rev. Latinoam. Enferm. 29, e33899 (2021).

Wang, S. et al. The interactive effects of heart failure knowledge on self-care of patients with chronic heart failure and caregivers’ self-care contribution. J. Qilu Nurs. 29 (07), 5–8 (2023).

Si Yanping. Survey and analysis of disease knowledge and needs of patients with chronic heart failure. Chin. Evid. Based Nurs. 5 (03), 259–261 (2019).

Qiao Yue. A qualitative study on home-based capacity management experience of elderly patients with chronic heart failure. J. Nurs. Sci. 38 (04), 108–111 (2023).

Cox, C. L. An interaction model of client health behavior: theoretical prescription for nursing. Adv. Nurs. Sci. 5 (1), 41–56 (1982).

Riegel, B. et al. An update on the self-care of heart failure index. J. Cardiovasc. Nurs. 24 (6), 485–497 (2009).

Chen Wei, L. & Ping, L. Reliability and validity testing of the Chinese version of the self-care behavior scale for patients with heart failure. Chin. J. Nurs. 48 (7), 629–631 (2013).

Broadbent, E. et al. The brief illness perception questionnaire. J. Psychosom. Res. 60 (6), 631–637 (2006).

Zhu, Y. et al. Comparative study of responsiveness of subjective reported outcome scales for chronic heart failure (in English). J. Chin. Integr. Med. 10 (12), 1375–1381 (2012).

Belayneh, M. et al. Adherence to self-care recommendations and associated factors among adult heart failure patients in West Gojjam Zone Public Hospitals, Northwest Ethiopia. Int. J. Chronic Dis. 1–11 (2022).

Ran, X., Li, J., Cheng, W. Application of internet++ cox’s interaction mode of health behavior in discharged stroke patients. J. Qilu Nurs. 30 (01), 102–105 (2024).

Lee, S. et al. Abstract 15270: comorbidity, age, self-care maintenance, and confidence influence heart failure symptom Perception. Circulation 138 (S1), A15270–A15270 (2018).

Hagger, M. S. & Orbell, S. The common sense model of illness self-regulation: a conceptual review and proposed extended model. Health Psychol. Rev. 16 (3), 347–377 (2022).

Timmermans, I. et al. Illness perceptions in patients with heart failure and an implantable cardioverter defibrillator: dimensional structure, validity, and correlates of the brief illness perception questionnaire in dutch, French and German patients. J. Psychosom. Res. 97, 1–89 (2017).

Lewis, F. E. et al. Preferences for quality of life or survival expressed by patients with heart failure. J. Heart Lung Transplant. 20 (9), 1016–1024 (2001).

Bozkurt, B. et al. Cardiac rehabilitation for patients with heart failure. J. Am. Coll. Cardiol. 77 (11), 1454–1469 (2021).

Ye Lingyan. The influence of cox’s interaction mode of health behavior on self-management ability of malignant tumor patients under chemotherapy. J. Mod. Med. Health. 39 (23), 4038–4041 (2023).

Wang, H., Yujia, L. & Jiefu, Y. Epidemiology of heart failure. J. Clin. Cardiol. 39 (04), 243–247 (2023).

Olchanski, N. et al. Two-year outcomes and cost for heart failure patients following discharge from the hospital after an acute heart failure admission. Int. J. Cardiol. 307, 109–113 (2020).

Arundel, C. et al. Length of stay and readmission in older adults hospitalized for heart failure. Arch. Med. Sci. 17 (4), 891–899 (2021).

Ambrosy, P. A. et al. The global health and economic burden of hospitalizations for heart failure. J. Am. Coll. Cardiol. 63 (12), 1123–1133 (2014).

Geng, H. Application of cox’s interaction mode of health behavior in behavioral management of patients after first coronary stenting. Chin. Gen. Pract. Nurs. 21 (15), 2103–2106 (2023).

Funding

This work was supported by the Henan Provincial Science and Technology Research Project (242102310194) (2421023101271).

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

ZF, FC analyzed the data and drafted the manuscript.WS, J T Salvador, M B De Ala, M A Cabansag Nery, L Z, X H, S L, contributed to the interpretation of the research results and the critical revision of the important intellectual content in the manuscript. All authors have read and approved the final manuscript.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher’s note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if you modified the licensed material. You do not have permission under this licence to share adapted material derived from this article or parts of it. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Feng, Zf., Cheng, F., Shen, Wj. et al. Construction and application of a self-care behavior intervention scheme for chronic heart failure patients based on interaction model of client health behavior. Sci Rep 15, 31119 (2025). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-17169-w

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-17169-w