Abstract

Fine particulate matter (PM2.5) is a major contributor to air pollution-related mortality in Europe. The European Zero Pollution Action Plan (ZPAP) aims to reduce PM2.5-attributable deaths by 55% by 2030 relative to 2005, while the EU Directive 2024/2881 states the new Ambient Air Quality targets. The open questions are: (1) has the ZPAP and the EU Directive 2024/2881 target for PM2.5 already been reached? If not, (2) will the current policy allow the ZPAP and EU 2024/2881 target for PM2.5 to be met in 2030, or (3) is an additional policy needed? This work proposes a methodology to estimate the attributable deaths caused by PM2.5 exposure in 2005, 2019 (question 1), and 2030 projection, considering the current legislation (CLE2030, question 2) and a policy (OPT2030, question 3), solution of a multi-objective problem that minimizes PM2.5 concentration and measure costs. The methodology was tested on the Po Valley in Northern Italy, one of the most polluted areas in Europe. Results show that premature deaths decreased by 36% on average from 2005 to 2019. By 2030, under current legislation (CLE2030), 18 of the 29 major cities are projected to meet the ZPAP target, while only 2 are expected to comply with the PM2.5 target of the Directive (EU) 2024/2881. With the implementation of additional measures (OPT2030), the number of cities meeting the ZPAP target rises to 26, and 13 are projected to achieve the PM2.5 limit recommended by the Directive (EU) 2024/2881.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Global air pollution exposure is predicted to cause 8.9 million deaths annually, accounting for 7.6% of total yearly mortality1,2. The relationship between air pollution and various health outcomes has been extensively studied, showing an increased risk of strokes, heart attacks, lung cancer, and chronic obstructive pulmonary disease3,4,5,6. Despite the improvement of air quality in Europe over the last 20 years, the European Environment Agency (EEA)7 calculated that in 2023 more than 253,000 premature deaths were caused by fine particulate matter (PM2.5), 52,000 by Nitrogen Dioxide (NO2), and 22,000 by ozone (O3) exposure8.

In response to the significant health burden caused by air pollution, the European Green Deal introduced a specific target in the Zero Pollution Action Plan (ZPAP) adopted by the European Commission in May 2021, which aimed to reduce air pollution-related premature deaths (in particular to PM2.5) by at least 55% by 2030 compared to 2005 levels8.

This health target complements the European Ambient Air Quality Directives, currently defined by Directive EU 2008/50/EC9 (2008 AAQD), which sets the maximum annual limit value of PM2.5 concentration at 25 µg/m3. This limit is scheduled to be reduced to 10 µg/m3 by 2030 under Directive (EU) 2024/28810 (2024 AAQD). It is important to underline that these regulatory thresholds do not correspond to zero health risk; according to WHO, the concentration level below which no adverse health effects have been observed is estimated equal to 5 µg/m3 for long-term PM2.5 exposure11.

Among European regions, the Po Valley is known for its challenges in reaching air quality standards despite emission reduction efforts12,13,14,15. In 2015, a European study on the health impact of PM2.5 identified cities in the Po Valley as having the highest mortality burden from PM2.5 exposure in Europe16. The persistently high levels of PM2.5 can largely be attributed to emissions from the transport, domestic heating, industrial, and agricultural sectors17,18,19 worsened by the Po Valley’s specific geographical and atmospheric conditions. The basin-like topography bounded by the Alps and the Apennines, the stagnant air masses, and thermal inversions trap pollutants in the lower atmosphere, leading to persistent poor air quality20,21. Especially, secondary components play a crucial role in determining PM2.5 concentrations in the area. Agricultural and livestock activities are significant contributors to ammonia (NH3) emissions (about 96%), which combine with gaseous precursors like SO2 (Sulphur dioxide) and NOx (nitrogen oxides) to form ammonium sulfate ((NH4)2SO4) and ammonium nitrate (NH4NO3)22,23 the main components of secondary PM2.5 in the area.

In this study, a methodology was formalized and applied to analyzes both the feasibility of achieving the PM2.5 2024 AAQD and ZPAP targets.

The methodology employed a modeling approach to assess the long-term health impacts associated with PM2.5 exposure from 2005 to 2030, specifically focusing on premature deaths among adult residents aged ≥ 30 years in 29 urban areas within the Po Valley region, implementing the WHO-recommended dose-response function.

For the years 2005 and 2019, city-level PM2.5 concentrations were obtained from EEA datasets, which combine monitoring data with atmospheric modeling24.

The year 2030 was assessed using projected emissions to estimate concentrations, exposure levels, and associated health impact under two scenarios: the Current Legislation scenario (CLE2030) and an Optimized Policy scenario (OPT2030). The CLE2030 scenario reflects the policies currently planned by the Italian energy and climate plan (PNIEC, 2019)25 with a methodology similar to other studies that examined air quality and health benefits of emission reductions in 2030 projections using the National Emission Ceiling Directive (NECD, 2016)26 or considering the National Energy Strategy (NES, 2012)27 or with optimized polices for European cities28. The OPT2030 scenario evaluates the application of an optimal air quality strategy, developed by solving a multi-objective optimization problem that minimizes both PM2.5 concentrations and policy implementation costs.

Projections to 2030 were generated using the Multi-objective Air Quality (MAQ) model29 a bottom-up Integrated Assessment Model designed to support policymakers in assessing air quality plans.

Uncertainty in PM2.5 concentrations and health impacts were evaluated with a Monte Carlo analysis, accounting for uncertainties of the dose-response function and the model PM2.5 concentration projection.

Results indicate that, between 2005 and 2019, PM2.5-related premature deaths decreased by an average of 36%. Under the CLE2030 scenario, 18 of the 29 cities are projected to meet the ZPAP target, while only 2 are expected to comply with PM2.5 target of the Directive (EU) 2024/2881. With the implementation of additional measures (OPT2030), the number of cities meeting the ZPAP target rises to 26, and 13 are projected to achieve the PM2.5 limit recommended by the Directive (EU) 2024/2881.

Results

This section presents the main results of the study, organized into four parts. First, we analyzed EEA historical air quality data, focusing on PM2.5 concentrations in 29 cities for the years 2005 (EEA2005) and 2019 (EEA2019), in order to evaluate the progress achieved over time. Subsequently, future air quality projections for the year 2030 are introduced, based on current legislation (CLE2030) and an optimized policy scenario (OPT2030), developed through the MAQ model. The Health Impact Assessment (HIA) was conducted for all considered scenarios and years, quantifying the benefits of reduced PM2.5 exposure in the context of the ZPAP. Finally, the fourth part details the features in terms of emissions, measures, and costs of the optimal policy.

Exposure assessment in 2005 and 2019

PM2.5 concentrations for the ZPAP reference year 2005 and the current scenario (2019) were obtained from the European Topic Centre on Air Pollution, Transport, Noise, and Industrial Pollution (ETC/ATNI) dataset of EEA24. The datasets include the yearly average PM2.5 data computed over the administrative area for 29 cities of the domain, as reported in Table 1.

The selection of these 29 cities was based on the availability of PM2.5 concentration data for 2005; for that year, there was a restricted monitoring coverage caused by the poor distribution of measurement stations. As a result, only cities with sufficient and reliable data for both years were included in the analysis.

In 2005, 19 of the 29 selected cities exceeded the 25 µg/m3 target set by 2008 AAQD, with concentrations ranging from 19.9 µg/m3 to 34.8 µg/m3 and a median value of 27.4 µg/m3. By 2019, all cities had successfully complied with the 2008 AAQD target, showing marked decreases in PM2.5 concentrations, with a median value of 18.2 µg/m3, due to EU policy interventions and local mitigation efforts. However, all cities exceeded the new target of 10 µg/m3 at 2030 established by 2024 AAQD, which is still twice the WHO guideline value of 5 µg/m3.

Assessment of the 2024 AAQD PM2.5 target

Emission-concentration-exposure projections for the year 2030 were estimated using the MAQ model29.

The CLE2030 projection corresponds to the scenario where only prevented actions are applied. It is obtained as a projection processing GAINS 203030 estimations, based on “EU Outlook 2017” and the Italian energy and climate plan (PNIEC)25. The GAINS 2030 scenario considers existing air quality directives and policies. The PNIEC plan outlines the reduction in fuel consumption by 2030, focusing on the primary energy sectors: electricity generation, household heating, industrial combustion, and transportation (details on the energy plan are available in the supplementary material, section S5).

The GAINS 2030 scenario is therefore used as baseline and adjusted in specific energy sectors where the PNIEC set more ambitious targets.

To assess how the regional air quality could further progress, a multi-objective optimization problem was solved starting from the CLE2030 scenario.

The solutions of the multi-objective problem constitute the Pareto front (see supplementary material section S7). The optimal solution near the maximum curvature is selected as the OPT2030 scenario, incorporating additional air quality measures beyond those recommended by 2030 (see “Future projections” sections in the Methodology).

The model’s output is the yearly average concentration per cell with a resolution of 6 × 6 km2 these values were then aggregated by municipality to compare the outputs with the previous data (domain concentrations are reported in the supplementary, section S8). The last two columns of Table 1 display the yearly average PM2.5 concentrations over the administrative domain of the selected cities for CLE2030 and OPT2030 scenarios, including confidence intervals that account for model uncertainty.

In the CLE2030 scenario, annual PM2.5 concentrations range from 9.9 µg/m³ to 16.5 µg/m³, with an average reduction of approximately 53% compared to 2005. The relative reductions vary across cities, with the most pronounced decrease observed in Bergamo (77%) and the lowest in Rimini (24%). All the cities reach the target set by 2008 AAQD, while, considering the model uncertainty, a total of 27 (CI 26–29) cities will not reach the 2024 AAQD target.

Under the OPT2030 scenario, further reductions in PM2.5 concentrations are achieved across all cities. The additional mitigation efforts resulted in an average reduction of 59% compared to 2005 levels. With supplementary emission reduction measures, the number of cities over 10 µg/m3 (2024 AAQD) will decrease to 22 (CI 16–27).

ZPAP target assesment

The results in terms of attributable deaths for all the scenarios analyzed are reported in Table 2. The HIA indicates that all cities exhibited high levels of mortality for PM2.5 exposure in 2005 (16% of total natural deaths). By 2019, substantial reductions in attributable deaths (AD) were observed across all cities, with a total mean reduction of 36%. However, no city achieved the ZPAP target. The CLE2030 scenario results in 57% reductions in premature deaths for the whole area compared to 2005. 18 cities (CI 16–21) are expected to meet the ZPAP target. However, three cities do not reach 40% (Venice, Ravenna, and Rimini), indicating the need for additional interventions. Under the OPT2030, 26 cities (CI 22–27) achieve the ZPAP target, with a total average reduction of 71% relative to 2005. Despite these improvements, Venice, Ravenna, and Rimini still fail to meet the target. In this scenario, 7071 estimated premature deaths (CI 6286–7697) could be yearly prevented across the considered cities, corresponding to 11% of the total natural deaths.

These improvement on residents’ health is associated with a progressive reduction in public health costs, from 33.3 B€ in 2005 to 14.5 B€ in CLE2030 and 9.7 B€ in OPT2030. These costs refer to the population of the 29 cities included in the study and therefore represent a conservative estimate of the total potential benefits across the Po Valley domain.

2030 optimal policy features

The optimal policy scenario corresponds to a budget amount of 300 M€ per year over CLE2030, equivalent to 17% increase of the CLE2030 budget. The optimal solution corresponds to a budget allocated mostly to the residential combustion (Corinair macrosector 2, MS2) (~ 200 M€ per year), followed by agriculture (Corinair macrosector 10, MS10, ~ 53 M€ per year). The remaining budget is split between the energy production (Corinair macrosector 1, MS1) and the transport (Corinair macrosector 7 and 8, MS7-MS8).

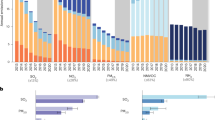

As it is represented in Fig. 1, domestic heating, particularly the use of stoves and fireplaces, is the main source of Primary PM (PPM) emissions in CLE2030 and also contributes significantly to NOx emissions (16%), mainly produced by natural gas combustion. Agriculture accounts for 98% of ammonia emissions and 36% of VOC emissions. The transport sector is the primary contributor to NOx emissions (40%), followed by industrial combustion. VOCs are emitted from the solvent and paint use sector (39%), followed by agriculture, and the production process (8%).

The implementation of the optimal set of measures (OPT2030) allows the reduction of NOx emissions by 40%, primary PM2.5 by 39%, ammonia by 28%, and VOC by 12%, as represented in the right part of Fig. 1. Additionally, energy policies lead to co-benefits in CO2 emissions, reduced by 17%.

A selection of key policies identified by the optimization problem in OPT2030 is reported in Table 3, where energy measures are represented in orange, while end-of-pipe technologies are in blue, while fuel-switch measures are not selected as efficient measures. Residential combustion (MS2) receives the largest budget allocation, primarily focusing on new performance certifications for wood stoves (25.3% application, 137.3 M€/year) and new fireplaces (98.3% diffusion, 26.4 M€/year), reducing Primary PM and VOC emissions. In agriculture, key measures involve ammonia emission reductions via covered storage and low ammonia application for liquid manure management (95% implementation for dairy and 80% for other cattle, ~ 31.3 M€/year total). Additional interventions target transport emissions, such as urban goods delivery optimization (61.6%, 1.8 M€/year) and higher efficiency on off-road agricultural vehicles (84.5%, 1.4 M€/year), resulting in NOx reductions. NH3 and NOx emission reductions limit the secondary PM production and accumulation.

Discussion

The research assessed and estimated the PM2.5 concentrations and the premature deaths attributable to chronic exposure to this pollutant for the years 2005, 2019, and projections for 2030. The research followed a two-step approach: (i) an analysis of historical air quality data, sourced from the EEA; and (ii) the generation of 2030 projections using an integrated modeling framework considering both current legislation at 2030 and an optimal air quality policies scenario. The latter represents the application of an efficient set of emission reduction measures defined by solving a multi-objective optimization problem. The analysis was performed using a regional-scale Integrated Assessment Model (IAM), capable of capturing the non-linear relationships between emission sources and pollutant concentrations and considering at the same time energy and end-of-pipe measures in the decision problem.

A Health Impact Assessment was embedded within this framework using a Monte Carlo method to account for uncertainties in exposure-response functions (RR) and air quality modeling (considering the standard deviation of Source-Receptor Model, enhancing confidence in estimation of premature deaths.

The historical analysis revealed reduced PM2.5 levels in urban areas of the Po Valley region from 2005 resulting from European and national air quality regulations. Nonetheless, none of the cities comply with the PM2.5 EU 2024/2881 target of 10 µg/m³.

Projections for 2030, based on current and planned emission reduction scenarios, suggested that further significant reductions in PM2.5 levels are possible. However, only 2 of the 29 cities are expected to meet the 2024 AAQD standards, an outcome consistent with findings from other studies27. The OPT2030 scenario showed an improved outcome: approximately 25% of the cities meet the 2024 AAQD standard, though none reach the WHO guideline value.

The HIA indicates a 36% reduction in premature deaths from 2005 to 2019, and none of the cities met the ZPAP target. Following the current legislation on air quality could prevent thousands of premature deaths by 2030, an average reduction of 57% across the 29 cities compared to 2005. However, the reductions are not-uniformly distributed in the domain, ranging from 12 to 78%, with 10 cities still failing the reaching of ZPAP target. Implementing optimized, targeted air quality strategies enables additional seven cities to meet the ZPAP target, leaving only three cities still noncompliant. These outliers likely require supplementary city-level interventions beyond the regional measures.

The modeling assessment reveals that the ZPAP PM2.5 target is more achievable than compliance with the 2024 AAQD PM2.5 target, representing a policy-relevant benchmark in highly polluted regions, as the Po Valley, where achieving strict concentration thresholds may be infeasible in the medium term. Adopting the ZPAP target as an intermediate step may thus help guide effective and regionally tailored air quality planning while still ensuring significant public health benefits.

The optimal regional strategy, derived from the multi-objective optimization framework, considers the emission reduction measures for the key precursor sources. A substantial portion of the mitigation budget was directed toward the residential combustion sector, which remains a major source of PPM2.5 emissions in the Po Valley. Specifically, the strategy emphasizes the replacement or certification of inefficient wood-burning appliances, such as stoves and fireplaces, which are widely used for domestic heating, particularly in rural and peri-urban areas. The implementation of stringent performance standards and the promotion of cleaner technologies in this sector are critical to achieving relevant reductions in PM2.5 concentrations.

In addition, the optimal strategy incorporates comprehensive measures in the agricultural sector, with a particular focus on reducing ammonia emissions, key precursors in the formation of secondary particulate matter. The model identifies improved manure management, recommending a combination of covered storage systems and low-emission application techniques for liquid manure, especially in dairy and cattle farming.

The transport sector also features in the optimized policy selection. Measures in this sector primarily aim to enhance the efficiency of urban logistics and reduce emissions from off-road vehicles used in agriculture and construction. The optimization identifies the reorganization of urban goods delivery systems, upgrades to off-road diesel vehicles, and uses of electric buses to lower NOₓ emissions.

The current study using a comprehensive assessment framework underscores the necessity of expediting the development of environmental public health policies aimed at achieving the ZPAP. Overall, the optimal policy reflects the need for integrated, cross-sectoral approaches to air quality improvement.

Strength and limitations

A strength of this research is the use of the MAQ Integrated Assessment Model, which captures non-linearities in pollutant concentrations and enables spatially refined projections. This model, enhanced by neural networks, allowed for better prediction accuracy across varying urban and rural landscapes. Additionally, the study’s HIA employed a robust Monte Carlo approach to address uncertainties in exposure and mortality risk estimates, enhancing confidence in the projections of premature mortality. This methodological approach integrated emissions reduction scenarios with health outcomes, offering a detailed evaluation of how enhanced pollution abatement strategies can align with stringent policy targets.

Comparing our findings with similar studies across Europe, we found that the estimated mortality reductions align closely with those estimated7,16,26,31,32. Yet, this study is unique in its application of scenario analysis and multi-objective decision problem to gauge the feasibility of Zero Pollution and 2024 AAQD PM 2.5 targets at a local level, a crucial approach given the persistent air quality challenges in the Po Valley due to topographical and meteorological factors.

However, certain limitations should be considered. This work assumed uniform exposure within each municipality, which might overlook localized differences in air quality that can influence individual health outcomes. The emission scenario used in this study is based on the EU Outlook 2017, which underpinned several policy assessments at the European level, including the first Clean Air Outlooks and the National Emissions Ceiling Directive. However, more recent projections are available, such as those included in the Second Clean Air Outlook, reflecting updated legislation and national measures. While the use of an older scenario may not fully capture recent policy developments, it provides a consistent reference scenario that has been widely applied in previous integrated assessments.

Finally, at the national level, the model relies on the 2019 version of Italy’s National Energy and Climate Plan, which was the most recent plan available at the time the emission projections were developed. Although an updated version has been released in 2024, the differences in projected emissions relevant to local air quality appear to be moderate. The most significant differences were found in the energy production and residential heating sectors. These changes are estimated to affect total precursor emissions by approximately 1% for NOₓ and SO₂, resulting in only marginal variations in air pollution concentrations. Therefore, the use of the 2019 plan is not expected to substantially affect the estimated pollutant concentrations or related health impacts.

Future studies should focus on refining exposure models and exploring the impacts of updated policy plans on other pollutants and their public health outcomes.

Methods

The study was performed with a two-step analysis: the first part considers the progress already reached in air quality improvements from 2005 to the current situation, in this case, the reference year is 2019. The second step corresponds to the projection evaluation to 2030 and the identification of an optimal policy to define the OPT2030 scenario. Finally, to all the years and scenarios analyzed a Health Impact Assessment was carried out to estimate the number of attributable deaths and their reduction with respect the 2005.

Step 1: historical air pollution data and City selection

The Po Valley is a geographical area located in northern Italy, roughly between 40° and 50° N latitude and 5° and 15° E longitude. The whole area is partitioned into four administrative regions: Piedmont, Lombardy, Emilia-Romagna, and Veneto. Data on PM2.5 yearly concentrations for this area were retrieved from the European Environment Agency (EEA) datahub24 specifically those provided by the European Topic Centre on Air Pollution, Transport, Noise, and Industrial Pollution (ETC/ATNI) interpolated maps in the ETC/ATNI 2021/1 report33. The pollutant concentrations were computed through a methodology that combines air quality monitoring data, chemical and transport model outputs, and supplementary datasets, including land cover, meteorological, and satellite data. This approach allowed for spatially resolved estimates of annual pollutant concentrations across Europe, with a resolution of 1 × 1 km² for both urban and rural areas33.

Data were collected for the ZPAP reference year (2005) and the current scenario (2019). The diffusion of monitoring stations of PM2.5 concentration was limited in 2005, leading to restricted data availability for this reference year. Other databases, providing concentration data for some selected cities, are evaluated, such as those presented by Southerland et al.34 but these data differ widely from measurement data and therefore, are not used for this study.

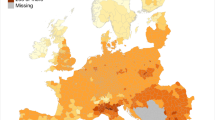

For this study, a total of 29 cities (accounting for 25% of the total Po Valley population) were analyzed, following EEA PM2.5 concentration data availability for 2005. The cities are reported in Fig. 2.

The Po Valley domain with the cities considered for this study. (Map generated using QGIS version 3.34 https://www.qgis.org with base imagery from OpenStreetMap contributors, accessed via the QuickMapServices plugin https://plugins.qgis.org/plugins/quick_map_services/. The map was edited and annotated in QGIS).

Step 2: 2030 projections and optimal policies

The CLE2030 scenario serves as a reference for identifying additional optimal policies to develop an enhanced scenario, referred to as OPT2030, which incorporates further air quality measures beyond those planned for 2030.

Accordingly, the decision problem was formulated to determine the set of policies that should be implemented to improve air quality within the domain.

The decision variables correspond to the degree of application on the overall domain of the emission reduction measures. Measures are diversified to each source activity and are mainly categorized in three groups\(\::\).

-

the end-of-pipe measures, that reduce the emissions released without altering the energy consumption of the activities.

-

the fuel switch measures, which consists of the shifting from a fuel to another with lower emissions or higher efficiency.

-

the energy measures, that directly reduces the energy consumption of a source activity.

A policy is represented by the decision variable set\(\:\:\pi\:=\left({\pi\:}_{x}\right)\), where each component\(\:\:{\pi\:}_{x}\) denotes the penetration rate of the emission reduction measure \(x \epsilon X(X\)denotes the set of emission abatement measures). The measure application can improve the air quality over the domain, which is considered as the first performance index to be minimized, AQI (Air Quality Index). At the same time, it must be considered the costs required to implement these measures, TC (Total Costs). The objective function (\(\:\text{J}\left({\pi\:}_{x}\right))\) is therefore a two-dimensional vector, containing the two performance indexes:

Where the \(\:AQI\) is the yearly mean PM2.5 concentrations, computed as a function of the emission of each precursor \(\:p\), where \(\:p=\left\{{NO}_{x},\:VOC,\:{NH}_{3},PM2.5,\:S{O}_{2}\right\}.\) The precursor emissions \(\:{E}_{p}\), are directly varied by the decision variables \(\:\left({\pi\:}_{x}\right)\). The total cost \(\:TC\) of the policy is the sum of the measures implementation cost for each fuel-activity, knowing the unit costs of each measure.

The optimal control policy \(\:{\pi\:}_{x}^{*}\) is therefore the one that minimizes\(\:\:\text{J}\left({\pi\:}_{x}\right):\)

where \(\:{\Pi\:}\) denotes the feasible set of the decision variables \(\:{\pi\:}_{x}\:\)considering technical and policy constraints (see supplementary material, section S6).

The problem does not have a singular solution that concurrently minimizes both objectives. An infinite set of Pareto optimal solutions \(\:{\mathcal{P}}^{*}\) is present in this problem, corresponding to the set of non-dominated solutions. Considering an objective function with q objectives:

Definition 1

Policy \(\:\pi\:\) dominates policy \(\:\pi\:{\prime\:}\), denoted by \(\:\pi\:\prec\:\pi\:{\prime\:}\), if: \(\:\forall\:i\in\:\left\{1,\dots\:,q\right\},\:\:{J}_{i}\left(\pi\:\right)\le\:{J}_{i}\left({\pi\:}^{{\prime\:}}\right)\wedge\:\:\exists\:j\in\:\left\{1,\dots\:,q\right\}\:\text{s}\text{u}\text{c}\text{h}\:\text{t}\text{h}\text{a}\text{t}\:{J}_{j}\left(\pi\:\right)<{J}_{j}\left({\pi\:}^{{\prime\:}}\right)\).

As the problem defined in Eq. (1) involves two objective functions, q = 2 is assumed.

Definition 2

A policy \(\:\pi\:\) is non-dominated (or Pareto optimal) if no policy \(\:\pi\:{\prime\:}\) exists such that \(\:\pi\:{\prime\:}\prec\:\pi\:\).

The collection of non-dominated solutions constitutes a Pareto curve, illustrating the optimal AQI alongside its corresponding policy cost values. There are different approaches to solve multi-objective problems, where the aim is generally to reduce the problem to a single objective optimization. In this case the problem is solved with an \(\:\mathcal{E}\)-constraint approach, where the total cost is fixed as a constraint, and the AQI is minimized. The Pareto frontier is obtained by varying the cost.

In this problem, the set of decision variables (\(\:\pi\:\)) corresponds to a total of 845 variables, combining 396 measures applicable to 110 sectors over 44 emissive activities, that are constrained following the description in Turrini et al.29 and the Supplementary material (section S6) The problem is solved with an IAM model, described in the following section.

IAM model

The MAQ system29 is a tool to support policymakers in the definition and evaluation of air quality strategies considering the health exposure and impact, policy costs, and greenhouse gas emission reduction35,36. Efficient policies reduce precursor emissions, which are converted into pollutant concentrations via nonlinear Source-Receptor Models (SRM). The tool can perform the analysis of scenarios, in which a predefined policy is applied a priori, or solve a multi-objective decision problem, where efficient policies are identified minimizing PM2.5 concentration and cost.

The MAQ input provides estimations of the spatially distributed emissions of precursors across the designated domain (in this work the Po Valley), alongside a comprehensive database that encompasses anthropogenic activities and their corresponding abatement measures. The models perform different analysis that starts from a base-case scenario. The definition of the scenario requires input data about emissions, sources, and meteorology. In this case the base case 2019 scenario.

The emissions were obtained with a merge of different inputs: (i) the local INEMAR inventory of the year 2017, developed by the Italian Regional Environment Agencies (ARPA) of the Po Valley as part of the LIFE PREPAIR project (INEMAR, https://www.lifeprepair.eu) and (ii) the national “EUoutlook2017” scenario projection to 2020, developed by IIASA with the Greenhouse Gas and Air Pollution Interactions and Synergies (GAINS) model37 which offers detail on emission factors, an extensive list of potential reduction measures for each activity, and their associated costs38. The emissions are linked to their relative concentrations with a SRM, trained with a set of scenarios obtained by a chemical and transport model. The model simulates different scenarios where the emissions are varied (individually to each precursor and combining different precursors), considering a defined meteorology, in this case, those of 2019. These steps are necessary to cover different possibilities of emission reduction variation, which could be processed with the MAQ model.

The emissions and PM2.5 concentration over the domain for the BC2019 scenario with its relative validations are available in supplementary material section S2.

Health impact assessment

HIA was performed to estimate the effect of PM2.5 exposure on natural-cause mortality for residents of each considered municipality in the years 2005, 2019, and 2030. The PM2.5 exposure-attributable deaths (AD) were estimated using an Exposure Response Function (ERF), from the latest European Topic Centre Human health and the environment report39 that quantifies the association between air pollution and mortality, following Eq. (1).

Where MR represents the all-cause mortality rate of the population aged 30 years and over in each municipality, and afPM2.5 is the attributable fraction related to PM2.5 exposure, which is computed with Eq. (2).

The Relative Risk (RR) was taken from the WHO Guidelines40 for all-cause mortality as a measure of the increase in the risk of death for an increase of 10 µg/m3 in PM2.5 concentration, and it’s equal to 1.08 (1.06–1.09). The concentration considered is the yearly average value in the municipality domain, and the cut-off was set to 5 µg/m3, below which there is no increased health risk according to WHO40. If the concentration was lower than this cut-off, the corresponding AD is zero.

The population was obtained from the Italian National Statistical Institute (ISTAT) for each municipality in the year 2019. The natural-cause mortality in people aged 30 years and over by age class and municipality was taken from ISTAT for 2005 and 2019. For future projections is used the population and mortality data of 2019.

The cost benefits associated with prevented premature deaths due to PM2.5 exposure can be expressed in terms of Value of a Statistical Life (VSL). The VSL represents “the sum of money each individual is prepared to pay for a given reduction in the risk of premature death, for example from diseases linked to air pollution”, as defined in the “Mortality Risk Valuation in Environment, Health and Transport Policies” report41. It is therefore the societal willingness to pay to avoid a statistical death, accounting for both income and the value of leisure time. This value is not a universal constant but varies across countries, as it depends on income levels, risk preferences, and cultural factors, necessitating its computation on a context-specific variables41. In the work of Sweis42the economic parameter considered is the marginal utility of consumption, ranging from 0 to 1. In this work42 is considered an intermediate value of marginal utility equal to 0.5, that corresponds to a VSL for Italy equal to 3.8 million USD42. Health damage costs were obtained by multiplying the number of attributable deaths by the VSL.

Uncertainty analyses

A Monte Carlo approach has been adopted to propagate the uncertainties, obtaining point estimates and confidence intervals (CIs) for attributable deaths.

For historical data (2005 and 2019), a single Monte Carlo was performed to propagate RR uncertainty. 1000 simulations were conducted with mean value RR and standard deviation (\(\:\sigma\:\)) as in (6), where \(\:R{R}_{inf}\) and \(\:R{R}_{sup}\) are the lower and upper bounds of the 95% confidence intervals, using the 2.5th and 97.5th percentiles of the simulated attributable deaths, respectively.

For the future projection (CLE2030 and OPT2030), a double Monte Carlo accounting for both RR and MAQ model uncertainties (corresponding to the standard deviation of the validation phase for PM2.5 SRM, reported in supplementary material, section S4) was carried out. The first estimation considered a set of 1000 simulations for each municipality, using the model’s mean value and uncertainty. For each value, a second Monte Carlo was computed on RR, as explained before.

Data availability

Dataset on pollutant concentration data for 2005 and 2019 is available at https://www.eea.europa.eu/en/datahub/datahubitem-view/49930245-dc33-4c47-93b8-9512f0622ebc. Data about the projection to 2030, whenever applicable, are available from the corresponding author upon reasonable request.

References

Adar, S. D., Filigrana, P. A., Clements, N. & Peel, J. L. Ambient coarse particulate matter and human health: A systematic review and Meta-Analysis. Curr. Environ. Health Rep. 1, 258 (2014).

Anenberg, S. C. et al. Impacts of global, regional, and sectoral black carbon emission reductions on surface air quality and human mortality. Atmos. Chem. Phys. 11, 7253–7267 (2011).

Henning, R. J. Particulate matter air pollution is a significant risk factor for cardiovascular disease. Curr Probl. Cardiol 49, (2024).

Schraufnagel, D. E. et al. Health benefits of air pollution reduction. Ann. Am. Thorac. Soc. 16, 1478–1487 (2019).

Yuan, S. et al. Long-term exposure to PM2.5 and stroke: A systematic review and meta-analysis of cohort studies. Environ Res 177, (2019).

Turner, M. C. et al. Outdoor air pollution and cancer: an overview of the current evidence and public health recommendations. CA Cancer J. Clin. 70 https://doi.org/10.3322/caac.21632 (2020).

Harm to human health from air pollution. in Europe: burden of disease 2023 — European Environment Agency. https://www.eea.europa.eu/publications/harm-to-human-health-from-air-pollution/

European Commission. Pathway to a Healthy Planet for All Action Plan: ‘Towards Zero Pollution for Air, Water and Soil’. (2021). https://environment.ec.europa.eu/strategy/zero-pollution-action-plan_en

Directive – 2008/50 - EN - EUR-Lex. https://eur-lex.europa.eu/eli/dir/2008/50/oj/eng

Directive - EU – 2024/2881 - EN. - EUR-Lex. https://eur-lex.europa.eu/eli/dir/2024/2881/oj/eng

World Health Organization. WHO global air quality guidelines. Particulate matter (PM2.5 and PM10), ozone, nitrogen dioxide, sulfur dioxide and carbon monoxide 1–360. (2021).

Colombo, L. et al. Assessing the impacts and feasibility of emissions reduction scenarios in the Po Valley. Front Environ. Sci 11, (2023).

Pozzer, A., Bacer, S., Sappadina, S. D. Z., Predicatori, F. & Caleffi, A. Long-term concentrations of fine particulate matter and impact on human health in verona, Italy. Atmos. Pollut Res. 10, 731–738 (2019).

Trivelli, L., Borrelli, P., Cadum, E., Pisoni, E. & Villani, S. Spatial-Temporal modelling of disease risk accounting for PM2.5 exposure in the Province of pavia: an area of the Po Valley. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public. Health. 18, 1–19 (2021).

Tunesi, S., Bergamaschi, W. & Russo, A. G. Estimated number of deaths attributable to NO2, PM10, and PM2.5 pollution in the municipality of Milan in 2019. Epidemiol. Prev. 48, 12–23 (2024).

Khomenko, S. et al. Premature mortality due to air pollution in European cities: a health impact assessment. Lancet Planet. Health. 5, e121–e134 (2021).

Tositti, L. et al. Source apportionment of particulate matter in a large City of southeastern Po Valley (Bologna, Italy). Environ. Sci. Pollut Res. Int. 21, 872–890 (2014).

Raffaelli, K. et al. Improving air quality in the Po valley, italy: some results by the LIFE-IP-PREPAIR project. Atmos. 2020. 11, Page 429 (11), 429 (2020).

Battini, F., Agostini, A., Tabaglio, V. & Amaducci, S. Environmental impacts of different dairy farming systems in the Po Valley. J. Clean. Prod. 112, 91–102 (2016).

Pernigotti, D., Georgieva, E., Thunis, P. & Bessagnet, B. Impact of meteorological modelling on air quality: summer and winter episodes in the Po Valley (Northern Italy). Int. J. Environ. Pollut. 50, 111–119 (2012).

Diémoz, H. et al. Transport of Po Valley aerosol pollution to the Northwestern Alps-Part 2: Long-term impact on air quality. Atmos. Chem. Phys. 19, 10129–10160 (2019).

Wyer, K. E., Kelleghan, D. B., Blanes-Vidal, V., Schauberger, G. & Curran, T. P. Ammonia emissions from agriculture and their contribution to fine particulate matter: A review of implications for human health. J. Environ. Manage. 323, 116285 (2022).

Ti, C. et al. Mitigation of agricultural NH3 emissions reduces PM2.5 pollution in china: A finer scale analysis. J. Clean. Prod. 350, 131507 (2022).

Air Quality Health Risk Assessments. https://www.eea.europa.eu/en/datahub/datahubitem-view/49930245-dc33-4c47-93b8-9512f0622ebc

Energia, C. | Ministero dell’Ambiente e della Sicurezza Energetica. (2030). https://www.mase.gov.it/energia/energia-e-clima-2030

Pisoni, E. et al. Modelling the air quality benefits of EU climate mitigation policies using two different PM2.5-related health impact methodologies. Environ. Int. 172, 107760 (2023).

Piersanti, A. et al. The Italian National air pollution control programme: air quality, health impact and cost assessment. Atmos. 2021. 12, Page 196 (12), 196 (2021).

Relvas, H. et al. Optimal air quality policies and health: a multi-objective nonlinear approach. Environ. Sci. Pollut. Res. 24, 13687–13699 (2017).

Turrini, E., Carnevale, C., Finzi, G. & Volta, M. A non-linear optimization programming model for air quality planning including co-benefits for GHG emissions. Sci. Total Environ. 621, 980–989 (2018).

Greenhouse Gas and Air Pollution Interactions and Synergies. (GAINS) | IIASA. https://iiasa.ac.at/models-tools-data/gains

Kowalski, M., Kowalska, K. & Kowalska, M. Health benefits related to the reduction of PM concentration in ambient air, Silesian voivodeship, Poland. Int. J. Occup. Med. Environ. Health. 29, 209–217 (2016).

Boldo, E. et al. Health impact assessment of a reduction in ambient PM2.5 levels in Spain. Environ. Int. 37, 342–348 (2011).

Horàlek, J. et al. Eionet Report - ETC/ATNI 2021/1 European Air Quality Maps for 2019. (2021).

Southerland, V. A. et al. Global urban Temporal trends in fine particulate matter (PM2·5) and attributable health burdens: estimates from global datasets. Lancet Planet. Health. 6, e139–e146 (2022).

Volta, M. et al. Co-benefits of changing diet. A modelling assessment at the regional scale integrating social acceptability, environmental and health impacts. Sci. Total Environ. 756, 143708 (2021).

De Angelis, E., Carnevale, C., Marcoberardino, G., Di, Turrini, E. & Volta, M. Low emission road transport scenarios: an integrated assessment of energy demand, air quality, GHG emissions, and costs. IEEE Trans. Autom. Sci. 19, 37–47 (2022).

Rafaj, P. et al. Outlook for clean air in the context of sustainable development goals. Glob Environ. Change. 53, 1–11 (2018).

Amann, M. et al. Cost-effective control of air quality and greenhouse gases in europe: modeling and policy applications. Environ. Model. Softw. 26, 1489–1501 (2011).

Amann, M., Belis, C. A., Kiesewetter, G., Pisoni, E. & Van Dingenen, R. Assessing the Health Impacts and Benefits of Ambient Air Pollution in Europe: Update to the HRAPIE Methodology. (2024). https://www.eionet.europa.eu/etcs/etc-he

Soares, J. et al. Health Risk Assessment of Air Pollution and the Impact of the New WHO Guidelines. (2022).

OECD. Mortality Risk Valuation in Environment, Health and Transport Policies (OECD Publishing, 2012).

Sweis, N. J. Revisiting the value of a statistical life: an international approach during COVID-19. Risk Manage. 24, 259–272 (2022).

Acknowledgements

The authors are grateful to Dr. Matilde Bonzani for collaborating on the research.

Funding

No external funding was received for this work.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

Laura Zecchi Writing – review & editing, Visualization, Validation, Investigation, Software, Methodology, Formal Analysis, Data Curation. Michele F. Arrighini Writing – review & editing, Visualization, Validation, Investigation, Software, Methodology, Formal Analysis, Data Curation. Claudio Marchesi Writing – original draft, Writing – review & editing, Visualization, Formal Analysis. Francesco Donato Writing – review & editing, Supervision, Methodology. Marialuisa Volta Writing – review & editing, Supervision, Resources, Project administration, Methodology, Conceptualization.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher’s note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Supplementary Information

Below is the link to the electronic supplementary material.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if you modified the licensed material. You do not have permission under this licence to share adapted material derived from this article or parts of it. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Zecchi, L., Arrighini, M.F., Marchesi, C. et al. Progress and policies to achieve the zero pollution action plan and EU 2024/2881 PM2.5 targets in Northern Italy. Sci Rep 15, 31439 (2025). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-17176-x

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-17176-x