Abstract

Emergency department (ED) overcrowding contributes to delayed patient care and worse clinical outcomes. Traditional triage systems face accuracy and consistency limitations. This study developed and internally validated a machine learning model predicting intensive care unit (ICU) admissions and resource utilization in ED patients. A retrospective analysis of 163,452 ED visits (2018–2022) from Maharaj Nakhon Chiang Mai Hospital evaluated logistic regression, random forest, and XGBoost models against the Canadian Triage and Acuity Scale (CTAS). The XGBoost model achieved superior predictive performance (AUROC 0.917 vs. 0.882, AUPRC 0.629 vs. 0.333). Key predictors included mode of arrival, patient age, and free-text chief complaints analyzed with multilingual sentence embeddings. These results demonstrate that machine learning, incorporating unstructured text data, has the potential to enhance triage accuracy and resource allocation by more effectively identifying critically ill patients compared to traditional triage methods.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Over the past decade, visits to emergency departments (ED) have steadily increased globally, resulting in overcrowding that significantly reduces the quality of patient care and satisfaction1,2,3,4,5. ED overcrowding is a critical global health issue, driven by factors such as increased patient volume, acuity, and insufficient inpatient bed capacity, leading to prolonged ED length of stay6. This phenomenon, amplified during public health crises like the COVID-19 pandemic7 ,degrades the quality of care, delays treatment for time-sensitive conditions, and is associated with increased patient mortality. In our resource-limited setting, these challenges are magnified, making accurate and timely triage not just a matter of efficiency, but a critical determinant of patient outcomes.

Triage, the initial process of identifying life-threatening conditions and prioritizing care, is vital for efficient resource allocation in the ED. Standardized triage systems, such as the Emergency Severity Index (ESI)8 and the Canadian Triage and Acuity Scale (CTAS)9, exhibit variable accuracy, ranging from 59.2 to 82.9%. These systems rely heavily on clinical judgment, which can lead to significant variability and suboptimal outcomes10,11. Inaccurate triage contributes to ED overcrowding, delays in care, and increased mortality risks12,13,14. Over-triage strains resources, while under-triage impedes timely critical care2. Furthermore, nurse-based triage is influenced by cognitive biases and sociodemographic factors, raising concerns about fairness15,16,17,18,19.

To address these limitations, data-driven predictive models have been developed to improve triage accuracy. These models incorporate predictors readily available at triage, including vital signs, coded chief complaint, and patient history20,21,22,23,24,25,26. Electronic health records (EHRs) are rich sources of data, with unstructured clinical notes representing a significant portion of patient information27,28. Natural language processing (NLP) allows machine learning models to leverage this unstructured data, such as free-text chief complaints, by transforming them into various numerical features21,22,23,26,29. However, few studies have adopted this method, representing a considerable gap in research.

This study aims to develop and internally validate a machine learning model that integrates structured data with free-text chief complaints to predict the need for critical care. Our goal is to create a clinically applicable model that can reduce variability, improve predictive accuracy, and support real-time decision-making in the ED.

Methods

Study design and participants

This retrospective cohort study utilized data from the EHRs of Maharaj Nakhon Chiang Mai Hospital, a tertiary university hospital in northern Thailand with approximately 60,000 annual ED visits. Data were collected from January 1, 2018 to December 31, 2022. This study received approval from the Research Ethics Committee, Faculty of Medicine, Chiang Mai University—Panel 5 (Institutional Review Board), including a waiver of informed consent (Research ID: 0068/Study code: EME-2566-0068). All methods were performed in accordance with relevant guidelines and regulations, including the Declaration of Helsinki and institutional ethical standards. All patient identifiers were removed before analysis. This study was conducted and reported in accordance with the Transparent Reporting of a multivariable prediction model for Individual Prognosis Or Diagnosis with Artificial Intelligence (TRIPOD + AI) guideline. A completed TRIPOD + AI checklist is provided in the supplementary materials.

We included consecutive adult patient visits (≥ 18 years). We focused on adult patients as pediatric physiology and triage considerably different and would require a dedicated model. A qualified emergency nurse manually assigned a CTAS triage for each patient based on clinical guidelines9. We excluded visits that were duplicated, had missing triage labels, were dead on arrival, left without being seen, were transferred to another hospital, or had missing ED disposition data.

Data and outcomes

Patient demographic and clinical data available at the time of triage were included. Demographic variables included patient age and sex. Arrival characteristics included the mode of arrival (walk-in, emergency medical services, or referral) and case type (trauma or non-trauma). Clinical data included vital signs (heart rate, respiratory rate, blood pressure, oxygen saturation, and temperature), level of consciousness measured by the Glasgow Coma Scale (GCS) and the chief complaint. The chief complaint was documented by the triage nurse as unstructured free text in the local language (Thai), often with English medical abbreviations. An analysis of the most frequent chief complaints is provided in Supplementary Table S1.

The primary outcome was Intensive care unit (ICU) admission directly from the ED. The prediction horizon is the point of ED disposition; the model is designed to predict this outcome using only data available at the time of triage to assist in early decision-making.

Model development

Sample size calculations were conducted using the pmsampsize module30. Based on a prior research study’s ICU admission prevalence of 0.8%21, a c-statistic of 0.85, a shrinkage factor of 0.9, and 15 predictive parameters, the required sample size was determined to be 15,713 resulting in 4.19 events per predictor variable. Our final dataset of 163,452 visits far exceeded this minimum requirement. The included visits were stratified and randomized, split into a training set (80%) and a test set (20%) to preserve a balanced distribution of outcomes.

Data preparation began with addressing missing values. The number and percentage of missing values for each predictor are reported in Table 1. We used a dual strategy for imputation: continuous numerical predictors were imputed using the K-nearest neighbors (KNN) algorithm with k = 5, while categorical predictors were imputed using the most frequent value. To assess the robustness of this imputation, a sensitivity analysis was performed by training the final XGBoost model on a complete-case dataset (n = 123,541). The minimal deviation in performance (AUROC 0.915 vs. 0.917) suggested that our imputation method did not introduce significant bias. A comparison of data distributions before and after imputation for continuous variables is provided in Supplementary Fig. S1, confirming their similarity.

For feature engineering, we processed both unstructured and structured data. Unstructured free-text chief complaints were converted into 512-dimension semantic vector representations using the pre-trained Multilingual Universal Sentence Encoder. To manage the high dimensionality of these embeddings, Principal Component Analysis (PCA) was used to reduce them to 50 principal components, which retained over 95% of the variance. Other structured input features were handled using one-hot encoding for categorical variables and standardization for continuous variables.

We developed three machine learning models of increasing complexity: logistic regression with a lasso penalty, random forest, and XGBoost (eXtreme Gradient Boosting). These models were compared to a reference model based on the CTAS triage level. We tuned hyperparameters for each model using a random search with a 5-fold cross-validation strategy on the training set. The final hyperparameters for each model are listed in Supplementary Table S2.

Model evaluation

Model performance was evaluated in the test set using the area under the receiver operating characteristic curve (AUROC) and the area under the precision-recall curve (AUPRC). While AUROC assesses discriminative performance, AUPRC offers a better measure for imbalanced datasets by emphasizing positive predictive value31. Performance metrics were reported as the mean and 95% confidence intervals generated from 1,000 bootstrapped samples. We used 500 bootstrapped samples from the test set for the prediction instability plot, mean absolute prediction error, and calibration plot to confirm the stability and reliability of predictions across datasets32,33. SHapley Additive exPlanations (SHAP) were used to interpret the final XGBoost model and identify the most important predictive features. Analyses were performed using Python version 3.10.15.

Results

Participants

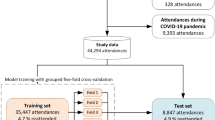

This study reviewed 172,791 patient visits during its duration. After these exclusions, the final cohort consisted of 163,452 visits (Fig. 1). Table 1 describes the characteristics of patients in this study. Overall, 13,406 visits (8.2%) resulted in ICU admission. A total of 2016 visits (1.2%) were triaged as CTAS level 3–5 and below and eventually admitted to the ICU, representing potential under-triage cases.

Model performance

The model performance metrics are shown in Table 2; Fig. 2. The XGBoost model demonstrated the highest discrimination (AUROC: 0.917 [95% CI 0.911–0.922]) and precision-recall (AUPRC: 0.629 [95% CI 0.608–0.649]). Both the random forest and XGBoost models achieved higher AUROC and AUPRC values than the logistic regression and the baseline CTAS system.

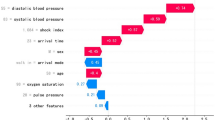

SHAP of the models revealed that the top predictors contributing to ICU admission were mode of arrival, age, vital signs, and chief complaint (Figs. 3 and 4). The waterfall plot in Fig. 4 shows how individual sampled features influence the likelihood of ICU admission for a specific prediction. The model’s average output or base value (E[f(x)]) adjusts incrementally based on the contributions of these features. The cumulative contributions from all features lead to a final log-odds of 2.812, which corresponds to a predicted probability of approximately 94.3% for ICU admission for the patient.

Discussion

This study demonstrates the potential of machine learning models to predict ICU admission from the ED more accurately than the conventional CTAS triage system. Our top-performing model, XGBoost, showed superior discrimination, a finding consistent with other studies that highlight the ability of tree-based models to capture complex, non-linear interactions among predictors20,23. The improvement in AUROC (0.917 vs. 0.882) is noteworthy, but the substantial improvement in AUPRC (0.629 vs. 0.333) is particularly compelling. AUPRC is more informative than AUROC in settings with class imbalance, such as ICU prediction, and this large gain suggests our model is significantly better at ensuring that patients flagged as high-risk are truly likely to require ICU admission, thereby improving the positive predictive value of the triage assessment. The step-like pattern observed in the CTAS ROC curve (Fig. 2) reflects its nature as a categorical scale with five discrete levels, which inherently limits its ability to provide nuanced, continuous risk stratification compared to the machine learning models.

Previous studies have shown that machine learning can improve triage outcomes using both structured and unstructured data, primarily in developed countries20,21,23,29,34. This study builds on those findings and demonstrates that such improvements are also achievable in resource-limited settings. Differences include excluding pain scores as they are subjective and unreliable for determining patient acuity35. Furthermore, the integration of NLP to analyze chief complaints in free text enabled the model to interpret textual data. Conventional triage systems, including ESI and CTAS, rely on chief complaints for categorization. The NLP approach can capture the subtle variations in clinical presentations, allowing for a broader categorization of chief complaints. Additionally, the use of multilingual embeddings effectively manages the linguistic diversity of clinical documentation in the local context, allowing the model to interpret text written in Thai with occasional English medical terms. However, reliance on free-text chief complaints introduces variability that could affect model prediction reliability.

Our findings also align with other advanced triage systems. For instance, the TriAge-Go system, a sophisticated software as a medical device (SaMD), also showed improved prediction over standard triage in a recent prospective evaluation36. While TriAge-Go represents a highly advanced implementation, our model demonstrates that significant improvements can also be achieved in resource-limited settings using readily available data.

This study shows that data-driven tools can make ED decisions more effective. By providing a real-time risk score, the model can flag high-risk patients for triage nurses, helping to mitigate under-triage and focus attention where it is most needed. It can also aid in resource management by providing more accurate forecasts for ICU bed demand.

Limitations

Several limitations should be acknowledged. First, a significant limitation is our definition of the ground truth. The primary outcome of direct ICU admission from the ED does not account for disposition errors, such as unplanned ICU transfers (UIT) from a general ward within 24 h of admission. These cases often represent patients who were under-triaged, and their exclusion may mean our model was trained on more clearly identifiable cases of critical illness, potentially overestimating its performance. Future prospective studies should incorporate UIT to create a more robust and clinically accurate composite outcome.

Second, this study is a retrospective, single-center analysis conducted on a predominantly Asian population, which inherently limits its generalizability to other settings and demographic groups. A critical challenge for all predictive models is performance degradation upon real-world, prospective implementation. Studies on models like the Rothman Index and the EPIC Sepsis Model have shown that even models validated on large retrospective datasets can experience a significant drop in performance when deployed, often due to data drift or overfitting37,38. Therefore, our model must be considered an early-stage development, and its clinical utility can only be confirmed through rigorous external and prospective validation.

Third, the reliance on free-text chief complaints, while powerful, introduces variability. The quality and detail of documentation can differ between nurses, which could affect model reliability. Future work should prioritize improving the quality of free-text inputs and exploring standardization using systems like SNOMED CT to enhance data consistency39.

Forth, the outcome was limited to ICU admissions. Certain conditions, such as anaphylaxis or reactive airway disease, require immediate attention but may not result in ICU admission. In contrast, conditions associated with high mortality, such as unconsciousness, may lead to death in the ED rather than admission to the ICU. Outcomes such as emergency procedures, early mortality, or ED resource utilization could provide a more comprehensive evaluation of patient acuity.

Finally, the absence of detailed patient history as a predictor may have constrained the model’s performance. Incorporating prior medical information could significantly enhance prediction accuracy and help address potential biases.

Conclusion

This study demonstrates that a machine learning model leveraging structured and unstructured EHR data can effectively predict the need for ICU admission with strong performance. The incorporation of free-text chief complaints and multilingual embeddings significantly enhanced prediction accuracy. While further validation is required, this work highlights a promising pathway toward more accurate, efficient, and equitable triage in the emergency department.

Data availability

The datasets generated and/or analyzed during this study are not publicly available due to hospital confidentiality policies and research grant restrictions but are available from the corresponding author upon reasonable request.

References

Higginson, I. Emergency department crowding. Emerg. Med. J. 29(6), 437–443. https://doi.org/10.1136/emermed-2011-200532 (2012).

Chen, W. et al. The effects of emergency department crowding on triage and hospital admission decisions. Am. J. Emerg. Med. 38(4), 774–779. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ajem.2019.06.039 (2020).

Hoot, N. R. et al. Does crowding influence emergency department treatment time and disposition? J. Am. Coll. Emerg. Physicians Open. 2(1), e12324. https://doi.org/10.1002/emp2.12324 (2021).

Morley, C., Unwin, M., Peterson, G. M., Stankovich, J. & Kinsman, L. Emergency department crowding: A systematic review of causes, consequences and solutions. PLoS One. 13(8), e0203316. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0203316 (2018).

Ruxin, T., Feldmeier, M., Addo, N. & Hsia, R. Y. Trends by acuity for emergency department visits and hospital admissions in california, 2012 to 2022. JAMA Netw. Open. 6(12), e2348053. https://doi.org/10.1001/jamanetworkopen.2023.48053 (2023).

Sartini, M. et al. Overcrowding in emergency department: Causes, consequences, and Solutions—A narrative review. Healthcare 10(9), 1625. https://doi.org/10.3390/healthcare10091625 (2022).

Shin, Y. et al. The development and validation of a novel deep-learning algorithm to predict in-hospital cardiac arrest in ED-ICU (emergency department-based intensive care units): A single center retrospective cohort study. Signa Vitae https://doi.org/10.22514/sv.2024.045

Gilboy, N., Tanabe, P., Travers, D. A., Rosenau, A. M. & Eitel, D. R. Emergency Severity Index, Version 4: Implementation Handbook Vol. 1 (Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality, Rockville, MD 2005).

Bullard, M. J. et al. Revisions to the Canadian Emergency Department Triage and Acuity Scale (CTAS) guidelines 2016. CJEM 19(S2), S18–S27. https://doi.org/10.1017/cem.2017.365 (2017).

Zachariasse, J. M. et al. Performance of triage systems in emergency care: A systematic review and meta-analysis. BMJ Open. 9(5), e026471. https://doi.org/10.1136/bmjopen-2018-026471 (2019).

Tam, H. L., Chung, S. F. & Lou, C. K. A review of triage accuracy and future direction. BMC Emerg. Med. 18(1), 58. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12873-018-0215-0 (2018).

Chiu, I. M. et al. The influence of crowding on clinical practice in the emergency department. Am. J. Emerg. Med. 36(1), 56–60. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ajem.2017.07.011 (2018).

Pines, J. M. & Hollander, J. E. Emergency department crowding is associated with poor care for patients with severe pain. Ann. Emerg. Med. 51(1), 1–5. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.annemergmed.2007.07.008 (2008).

Sun, B. C. et al. Effect of emergency department crowding on outcomes of admitted patients. Ann. Emerg. Med. 61(6), 605–611e6. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.annemergmed.2012.10.026 (2013).

Thirsk, L. M., Panchuk, J. T., Stahlke, S. & Hagtvedt, R. Cognitive and implicit biases in nurses’ judgment and decision-making: A scoping review. Int. J. Nurs. Stud. 133, 104284. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ijnurstu.2022.104284 (2022).

Essa, C. D., Victor, G., Khan, S. F., Ally, H. & Khan, A. S. Cognitive biases regarding utilization of emergency severity index among emergency nurses. Am. J. Emerg. Med. 73, 63–68. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ajem.2023.08.021 (2023).

Arslanian-Engoren, C. Gender and age bias in triage decisions. J. Emerg. Nurs. 26(2), 117–124. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0099-1767(00)90053-9 (2000).

Schrader, C. D. & Lewis, L. M. Racial disparity in emergency department triage. J. Emerg. Med. 44(2), 511–518. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jemermed.2012.05.010 (2013).

Vigil, J. M. et al. Ethnic disparities in emergency severity index scores among U.S. Veteran’s affairs emergency department patients. PLOS ONE. 10(5), e0126792. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0126792 (2015).

Ivanov, O. et al. Improving ED emergency severity index acuity assignment using machine learning and clinical natural Language processing. J. Emerg. Nurs. 47(2), 265–278e7. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jen.2020.11.001 (2021).

Fernandes, M. et al. Predicting intensive care unit admission among patients presenting to the emergency department using machine learning and natural Language processing. PLoS One. 15(3), e0229331. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0229331 (2020).

Sterling, N. W., Patzer, R. E., Di, M. & Schrager, J. D. Prediction of emergency department patient disposition based on natural Language processing of triage notes. Int. J. Med. Informatics. 129, 184–188. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ijmedinf.2019.06.008 (2019).

Zhang, X. et al. Prediction of emergency department hospital admission based on natural Language processing and neural networks. Methods Inf. Med. 56(05), 377–389. https://doi.org/10.3414/ME17-01-0024 (2017).

Hong, W. S., Haimovich, A. D. & Taylor, R. A. Predicting hospital admission at emergency department triage using machine learning. PLoS One. 13(7), e0201016. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0201016 (2018).

Raita, Y. et al. Emergency department triage prediction of clinical outcomes using machine learning models. Crit. Care. 23(1), 64. https://doi.org/10.1186/s13054-019-2351-7 (2019).

Joseph, J. W. et al. Deep-learning approaches to identify critically ill patients at emergency department triage using limited information. J. Am. Coll. Emerg. Physicians Open. 1(5), 773–781. https://doi.org/10.1002/emp2.12218 (2020).

Consultant, H. Why Unstructured Data Holds the Key to Intelligent Healthcare Systems (HIT Consultant, Atlanta, GA 2015).

Kong, H. J. Managing unstructured big data in healthcare system. Healthc. Inf. Res. 25(1), 1–2. https://doi.org/10.4258/hir.2019.25.1.1 (2019).

Tahayori, B., Chini-Foroush, N. & Akhlaghi, H. Advanced natural Language processing technique to predict patient disposition based on emergency triage notes. Emerg. Med. Australas. 33(3), 480–484. https://doi.org/10.1111/1742-6723.13656 (2021).

Riley, R. D. et al. Minimum sample size for developing a multivariable prediction model: PART II-binary and time-to-event outcomes. Stat. Med. 38(7), 1276–1296. https://doi.org/10.1002/sim.7992 (2019).

Davis, J. & Goadrich, M. The relationship between precision-recall and ROC curves. In: Proceedings of the 23rd International Conference on Machine Learning—ICML ’06 233–240 (ACM Press, 2006). https://doi.org/10.1145/1143844.1143874

Riley, R. D. & Collins, G. S. Stability of clinical prediction models developed using statistical or machine learning methods. Biomet. J. 65(8), 2200302. https://doi.org/10.1002/bimj.202200302 (2023).

Riley, R. D. et al. Clinical prediction models and the multiverse of madness. BMC Med. 21(1), 502. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12916-023-03212-y (2023).

Grant, L. et al. Machine learning outperforms the Canadian triage and acuity scale (CTAS) in predicting need for early critical care. Can J. Emerg. Med. https://doi.org/10.1007/s43678-024-00807-z (2024).

Ueareekul, S., Changratanakorn, C., Tianwibool, P., Meelarp, N. & Wongtanasarasin, W. Accuracy of pain scales in predicting critical diagnoses in non-traumatic abdominal pain cases; a cross-sectional study. Arch. Acad. Emerg. Med. 11(1), e68. https://doi.org/10.22037/aaem.v11i1.2131 (2023).

Taylor, R. A. et al. Impact of artificial intelligence–based triage decision support on emergency department care. NEJM AI. 2(3), AIoa2400296. https://doi.org/10.1056/AIoa2400296 (2025).

Rothman, M. J., Rothman, S. I. & Beals, J. Development and validation of a continuous measure of patient condition using the electronic medical record. J. Biomed. Inform. 46(5), 837–848. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jbi.2013.06.011 (2013).

Cull, J., Brevetta, R., Gerac, J., Kothari, S. & Blackhurst, D. Epic sepsis model inpatient predictive analytic tool: A validation study. Crit. Care Explor. 5(7), e0941. https://doi.org/10.1097/CCE.0000000000000941 (2023).

Vuokko, R., Vakkuri, A. & Palojoki, S. Systematized nomenclature of medicine–clinical terminology (SNOMED CT) clinical use cases in the context of electronic health record systems: systematic literature review. JMIR Med. Inf. 11(1), e43750. https://doi.org/10.2196/43750 (2023).

Acknowledgements

We thank Rudklao Sairai and the Research Unit of the Department of Emergency Medicine, Faculty of Medicine, Chiang Mai University, for their valuable support. We also sincerely appreciate Chiraphat Boonnag for expert guidance and Piyapong Khumrin for inspiring our enthusiasm in data science. This research was funded by the Faculty of Medicine, Chiang Mai University Research Fund (Grant No. INV08/2567).

Funding

This work was supported by the Faculty of Medicine, Chiang Mai University [grant number: INV08/2567, 2024].

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

P.S., B.W., W.S., and K.L. contributed to the study’s conceptualization and methodology. P.S. and W.S. developed software, performed validation, and carried out formal analysis, with additional input from K.L. P.S. and W.S. conducted data curation. All authors contributed to the investigation. K.L. provided resources, supervised the project, and was the corresponding author. P.S. prepared all figures and tables. P.S., B.W., and W.S. wrote the original manuscript draft, and all authors reviewed and edited the manuscript.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher’s note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Supplementary Information

Below is the link to the electronic supplementary material.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if you modified the licensed material. You do not have permission under this licence to share adapted material derived from this article or parts of it. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Sitthiprawiat, P., Wittayachamnankul, B., Sirikul, W. et al. Development and internal validation of an AI-based emergency triage model for predicting critical outcomes in emergency department. Sci Rep 15, 31212 (2025). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-17180-1

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-17180-1