Abstract

This study integrates network science and intersection graph theory to analyse the structural properties of recipe networks in Catalan cuisine. Using three distinct cookbooks, two traditional and one haute cuisine, we construct the recipe similarity networks by linking recipes based on shared ingredients, with link weights reflecting ingredient similarity. We introduce a new, ad hoc, similarity measure that overcomes some limitations of traditional similarity metrics. We explore how different methodological approaches, such as the substitution of recipes/ingredients with their composing ingredients and link weight normalisation, influence network structure and node centrality. Our analysis reveals that recipe similarity networks are highly interconnected but show structural differences across cuisines, particularly in haute cuisine, which features more specialised recipes. Node centrality metrics identify key recipes that define culinary traditions, such as “Allioli” in traditional Catalan cuisine and “Becada con brioche de su salmis” in haute cuisine. We also develop a community detection algorithm based on link removal and clique identification, which uncovers tightly-knit recipe groups. This study advances the field of computational gastronomy by providing a methodological foundation that can be integrated with artificial intelligence techniques to support recipe personalisation, food recommendations, and gastronomic innovation.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Computational gastronomy (CG) is an emerging interdisciplinary field using data-driven and computational methods to the study of food and cooking practices1,2,3. CG seeks to uncover patterns and relationships within recipes, ingredients, and cuisines by integrating concepts from food science, cultural studies, and data analytics4,5. Advances in computational technologies have enabled the application of numerical, simulation, and algorithmic approaches to analyse complex culinary datasets4,6,7,8. Research in CG employs machine learning (ML) techniques with direct applications in the field of artificial intelligence (AI)1,7,8,9. Large companies are launching ambitious projects aimed at leveraging AI in the culinary field, focusing on empowering chefs with AI and robotics to unleash creativity in recipe creation and execution (https://ai.sony/projects/gastronomy/).

Network science has experienced significant growth over the past two decades due to its ability to model diverse real-world complex systems10,11,12,13,14,15,16,17. Its application has extended to food science18 and gastronomy, where it has been used to analyse culinary systems19. Ahn et al. introduced a flavor network to study flavor compounds shared by ingredients, showing that Western cuisines tend to pair ingredients with shared flavor compounds, a pattern supporting the food pairing hypothesis, whereas East Asian cuisines favor ingredients with fewer shared compounds20. In the same year, Teng et al.21 constructed a ‘complement network’ based on the co-occurrence frequency of ingredients, revealing two dominant communities in the network: savoury and sweet.

Intersection graph theory, a branch of discrete mathematics and graph theory, models graphs based on the intersection patterns of sets22,23. The foundation of intersection graph theory can be attributed to Szpilrajn-Marczewski24, who demonstrated that all graphs can be viewed as intersection graphs25. Intersection graph theory has found applications in modeling diverse real-world problems23. In our context, the intersection graph formalism provides an intuitive and mathematically grounded way to model recipe similarity based on shared ingredients. Each recipe is treated as a set of ingredients, and links between recipes indicate the non-empty intersection of these sets. This representation aligns with the intuitive way of thinking about recipes as ingredient sets, making it not only theoretically sound but also conceptually accessible. This approach allows us to define a flexible threshold on the magnitude of the overlapping and to analyse the structure of the resulting recipes network as this threshold varies. Intersection graph theory is thus particularly well-suited for modeling systems like culinary data, where entities (recipes) are composed of overlapping subsets (ingredients), and where the similarity between entities depends on the size and structure of these intersections. Furthermore, it enables a principled way to explore how strongly recipes are connected and to identify cohesive subgroups within the recipe space using graph-theoretic tools.

In this study, we integrate network science and intersection graph theory to analyze the recipe cookbooks structure of Catalan cuisine. The dataset comprises three Catalan cookbooks: two focusing on traditional recipes and one on haute cuisine. Since all recipes are drawn from published, expert-authored sources and manually harmonized, our dataset is therefore reliable, standardized, and coherent, ensuring consistency and reliability of the input data, an aspect often lacking in studies relying on user-generated content. We construct the recipe similarity network (RSN) for each cookbook by linking recipes based on shared ingredients, where the link weights reflect the similarity of ingredients among recipes. We propose a novel similarity measure that accounts for the number of ingredients in each recipe, providing a normalized similarity score that avoids size bias and ensures a fair comparison across recipes. These RSNs are represented as complex weighted graphs, with weights indicating the magnitude of ingredient overlap between recipes.

We first investigate how methodological choices in constructing the RSN, such as simplifying recipes to their basic ingredients and normalising link weights considering the size of the ingredient sets, affect network structure and node rankings. These methodological adjustments significantly change the identification of key recipes within the network. Our analysis reveals that RSNs are highly connected, with most recipes sharing at least one ingredient. However, as the ingredient similarity threshold increases, connectivity decreases more rapidly in the haute cuisine network, highlighting the specialised and unique nature of these recipes compared to traditional cookbooks.

Next, we use node centrality measures from network science to identify pivotal recipes within the structure of the RSNs, uncovering essential dishes that define specific culinary traditions. This analysis provides insights into the interconnectedness of ingredients and recipes, shedding light on the underlying organisation of culinary systems.

Finally, we propose an algorithm that combines link removal and clique detection to identify tightly connected communities of recipes with varying levels of ingredient similarity. Technically, this approach relies on detecting maximal cliques after progressively filtering the network by increasing similarity thresholds, allowing us to extract fully connected subgraphs that represent core clusters of highly similar recipes. This algorithm has potential applications in computational gastronomy, including uncovering recipe communities that embody the ‘essence’ of a culinary tradition, generating ingredient-based recommendations, and identifying characteristic ingredients across different recipe categories. Beyond the culinary domain, the same clique-based framework can be applied to diverse fields: in biology, to detect groups of microbial communities with highly overlapping species (e.g., in microbiome studies); in ecology, to identify habitats with similar species assemblages; and in computer science, to group users or systems sharing highly overlapping access privileges or behavioral patterns.

This manuscript is organised as follows: Sect. 1 introduces computational gastronomy and its connection to network science and intersection graph theory, reviewing existing research on recipe and ingredient networks. Section 2 discusses related works, highlighting key studies and their main content. Section 3 details the dataset and methodology, including data extraction, network construction, and the proposed similarity measure build RSNs. Section 4 presents and discusses the results. Finally, Sect. 5 concludes by summarising findings, discussing implications, and suggesting future directions.

Related works

Network science is a powerful tool for characterising recipe collections and ingredient pairings by handling and analysing large, complex datasets19. By applying network analysis, researchers can reduce the complexity of recipe datasets, classify cuisines, and compare culinary traditions at both regional and global levels. This approach facilitates insights into the cultural, functional, and structural aspects of culinary systems.

Ahn et al.20 explored the use of network analysis in food science to study culinary ingredients and their chemical flavor compounds. Drawing on global online culinary databases, they construct a bipartite network linking ingredients to their flavor compounds. Then, the authors project the bipartite network into a weighted network of ingredients, where links represent shared flavor compounds. The analysis reveals modular structures within the ingredient network, corresponding to food categories such as fruits, vegetables, and meats. Furthermore, it demonstrates how shared compounds influence ingredient compatibility in different cuisines. This work laid the foundation for “computational gastronomy,” an interdisciplinary field combining data science with culinary studies2.

Kular et al.26 investigate the relationship between cuisine and culture through network analysis. They propose that recipes and their ingredients reflect the cultural origins of their creators. Their research constructs a Network of Recipes (NoR), where nodes represent recipes, and shared ingredients define edges. The NoR exhibits high connectivity between recipes, suggesting that dietary habits may be less diverse than anticipated. A PageRank analysis ranks recipes to identify universally significant dishes, showing that certain foods hold a central role across cultures. Community analysis further highlights the dominant cultural influences in specific regions, with Asian cuisine offering a clearer regional cultural identity than others.

Teng et al.21 propose a novel approach to recipe recommendations by analysing ingredient relationships within online recipe collections. They construct two types of networks: the complement network and the substitute network. In the complement network, nodes represent individual ingredients, and links indicate statistically significant co-occurrence in recipes. The substitute network, derived from user-generated suggestions, connects ingredients based on their ability to replace each other in recipes, with weighted edges reflecting substitution frequency. These networks reveal distinct clusters, such as sweeteners (sugar, honey, maple syrup) and cooking fats (butter, olive oil, margarine), showcasing functional and culinary similarities. Their study demonstrates how structured ingredient networks can support recommendation systems to individuate personal preferences, dietary needs, or ingredient availability.

Simas et al.27 explored two hypotheses in cooking, the well-known food-pairing20, and the food-bridging. Food-pairing suggests that if two ingredients share important flavor compounds, they likely occur together in recipes, while food-bridging proposes that contrasting ingredients can be connected through intermediate ones with shared affinities. The authors used network science to analyse the two hypotheses across various cuisines, identifying four culinary classes based on the prevalence of these mechanisms. They suggest that food-bridging enhances ingredient compatibility in recipes and is widespread in traditional cuisines, providing a novel perspective on culinary practices.

Caprioli et al.28 built a network of ingredient combinations in global cuisines using data from the CulinaryDB online repository, which provides structured information on recipes and ingredients (https://cosylab.iiitd.edu.in/culinarydb/). Each cuisine is represented as a network, where nodes correspond to ingredient types, and weighted links indicate how frequently ingredient pairs co-occur in recipes. A bipartite network is also modeled, connecting ingredient nodes to recipe nodes based on ingredient presence. The analysis identifies distinctive ingredient pairing patterns characterising different cuisines and reveals geo-cultural clusters formed by these combinations.

However, these studies rely on online databases that are the product of contributions from thousands of different authors, leading to a lack of standardised and curated data. This absence of uniform ingredient labeling often results in inconsistencies and inaccuracies. Herrera19 highlights the challenges of mining such data, emphasising the necessity of standardising ingredient information, and addressing biases and inaccuracies in recipe datasets.

Table 1 summarises the related works cited in this chapter, highlighting their strengths, limitations, and furnishing a comparative analysis with the approach we propose in this study.

Methods

Gastronomical database: mining and processing cookbooks

To study the recipe networks, three different compilations were selected: (1) Corpus del patrimoni culinari català (CTrad), 2011, La Magrana, Barcelona, (2) El Celler de Can Roca (Roca), 2018, Librooks, Barcelona, (3) 100 Plats indispensables de la cuina catalana (101), 2018, Cossetània, Barcelona. The CTrad book contains 1136 recipes of Catalan cuisine collected from over 400 restaurants and from interviews with people around Catalonia. The Roca contains 86 recipes representative of the cuisine developed at El Celler de Can Roca until 2016 selected by the three Roca brothers, Joan, Josep and Jordi. Finally, the 101 contains 100 recipes as representative of the Catalan cuisine carefully selected by a recognised expert, Jaume Fàbrega i Colom, PhD. Only the 779 recipes from the three cookbooks that were not categorised as desserts were included in the analysis.

Ingredient processing from each cookbook was done following an inhouse annotation guide that contains directives to overcome language related issues like synonymous naming or more culinary related issues, like decomposing complex (elaborated) ingredients (for example Chicken broth) into their unprocessed ingredients. For the analysis, each ingredient was assigned to a general base category that groups all the unelaborated varieties of the product by applying a gastronomic equivalence criterion. For example, all the ingredients written as onion, white onion, purple onion and purple onion sliced into pieces were assigned to the same general base category Onion. In a similar way all the cuts of meat from an animal were assigned to the original animal from which they were obtained. For example, minced veal, veal steaks, veal bones, veal, veal shank, diced veal trimmings, cooked veal head, legs of veal, veal heart groups in the general base category Veal. The rest of the ingredients were processed in the same way, resulting in 415 different general base categories in which the original written ingredients were grouped. The rest of the terms contained in the ingredient’s original name that could refer to its elaboration process, or properties as its origin, variety, colour, among others were also processed and assigned to different categories named Elaboration process 1, 2 or 3, and Intrinsic property 1, 2 or 3 to keep as much useful information as possible of each ingredient. Furthermore, all the terms extracted from the unprocessed original ingredients were lemmatised and underwent through a paraphrasis process to avoid multiple naming for the same ingredient. The Supplemental Material file contains the complete list of ingredients for the Ctrad (Table S1), 101 (Table S2), and Roca (Table S3) cookbooks.

Building gastronomical recipes networks with intersection graph theory

To construct the recipe similarity network (RSN), we apply principles from intersection graph theory22,23. In graph theory, a graph is a structure consisting of a set of objects called nodes (or vertices) connected by links (or edges)29. An intersection graph represents the pattern of intersections within a family of sets22.

Let be \(\:G\:=\:(N\:,\:L)\) an intersection graph where \(\:N\) is the set of nodes \(\:N=\{{n}_{1},{n}_{2},{n}_{3},\dots\:,{n}_{n}\}\) and \(\:L=\{{l}_{1},{l}_{2},{l}_{3},\dots\:,{l}_{l}\}\) the set of links. Formally, the intersection graph \(\:G\) is formed from a family of sets \(\:S=\left\{{s}_{1},{s}_{2},{s}_{3},\dots\:,{s}_{n}\right\}\) where each set \(\:{s}_{i}\) corresponds to the node \(\:{n}_{i}\). The link \(\:({n}_{i},\:{n}_{j})\) exists if and only if the corresponding sets \(\:{s}_{i}\) and \(\:{s}_{j}\) have at least one common ingredient. In other words, two nodes \(\:{n}_{i}\) and \(\:{n}_{j}\) are connected by a link if and only if the corresponding two sets \(\:{s}_{i}\) and \(\:{s}_{j}\) have a non-empty intersection:

In a recipe network, the family of sets defining the link among nodes is the recipe ingredient sets. Specifically, the set \(\:{s}_{i}\) contains the ingredients of the recipe \(\:i\), the set \(\:{s}_{j}\) contains the ingredients of the recipe \(\:j\) and so forth. A link \(\:({n}_{i},\:{n}_{j})\) exists if and only if recipes \(\:i\:\)and \(\:j\) share at least one common ingredient.

A recipe network can be described by an \(\:n\times n\) recipes matrix \(\:R\), where the element \(\:R(i,j)\) is:

Where \(\:{s}_{i}\:\cap\:\:{s}_{j}\) denotes the intersection between the ingredient sets of the recipes \(\:i\) and \(\:j\), and\(\:\left|\:{s}_{i}\:\cap\:\:{s}_{j}\right|\) indicates the cardinality of the intersection. Thus, \(\:R\left(i,j\right)=\left|\:{s}_{i}\:\cap\:\:{s}_{j}\right|\); where \(\:R\left(i,j\right)=0\) when the recipes \(\:i\) and \(\:j\) do not share ingredients, and \(\:R\left(i,j\right)\ge\:0\) if they share at least one ingredient in common between the recipes \(\:i\:\)and \(\:j\). The element \(\:R(i,j)\) quantifies the number of ingredients shared between two recipes.

Recipe similarity normalisation for computing link weight

The generic element \(\:R(i,j)\) of the weighted adjacency matrix \(\:R\) indicates the number of common ingredients between the link ending nodes/recipes. If we define the weight of the links as the cardinality of the intersection, we obtain weights that represent the number of shared ingredients between pairs of recipes. This graph can be described as a trivial weighted recipe network.

However, the number of shared ingredients depends on the total number of ingredients in each recipe. Recipes with many ingredients are more likely to share components with other recipes. Therefore, relying solely on the cardinality of the intersection may overestimate similarity, particularly for recipes with many ingredients.

To address this issue, we introduce a normalised similarity measure that accounts for the number of ingredients in each recipe. This similarity value becomes the weight \(\:{w}_{ij}\) of the link connecting recipes \(\:i\) and \(\:j\) in the network.

We calculate the weight \(\:{w}_{ij}\) of the links \(\:({n}_{i},\:{n}_{j})\) in this way:

Where \(\:\left|{s}_{i}\cap\:{s}_{j}\right|\) is the cardinality of the intersection between recipes \(\:{s}_{i}\) and \(\:{s}_{j}\), \(\:\left|{s}_{i}\right|\) is the cardinality of the ingredient set of recipe \(\:i\), and \(\:\left|{s}_{j}\right|\) is the cardinality of the ingredient set of recipe \(\:j\). This formula measures the relative similarity between \(\:{s}_{i}\) and \(\:{s}_{j}\), independent of the absolute size of their ingredient sets. \(\:{w}_{ij}\) represents a normalised similarity measure between two recipes \(\:i\) and \(\:j\) and ranges in the closed interval [0,1]. The minimum \(\:{w}_{ij}\)=0 indicates that there are no common ingredients (\(\:\left|{s}_{i}\cap\:{s}_{j}\right|=0\)). The maximum \(\:{w}_{ij}\)=1 indicates that the recipes share all their ingredients (\(\:{s}_{i}\)=\(\:{s}_{j}\)). Thus, the weight reflects the proportion of shared ingredients relative to the sizes of the ingredient sets. It assigns higher values to links connecting recipes with a significant ingredient overlap. The similarity measure we introduce offers advantages over traditional metrics such as the Jaccard index. While the Jaccard index normalises the intersection of two sets by the size of their union, our measure computes the average proportion of shared ingredients with respect to the size of each individual recipe set. This formulation reduces the bias against comparisons involving sets of differing sizes, which are often penalised by the Jaccard approach. At the same time, it retains important properties such as symmetry and normalisation within the [0,1] interval. Consequently, our measure more effectively captures meaningful overlaps in ingredient composition, particularly in cases where one recipe is fully or largely contained within another.

In summary, the RSN is an undirected weighted graph where nodes represent recipes, and link weights indicate the normalised number of shared ingredients. RSN captures the degree of similarity between recipes based on their ingredient composition. See Fig. 1 for a schematic representation of how the RSN is constructed from a database of recipe ingredients.

The recipe network assembling. (A) The process starts from the recipe sets. A recipe is a set of individual ingredients from which we compute the intersection set with another recipe. (B) The intersection set among recipes represents the common ingredients. If there are no common ingredients between two recipes, the intersection is an empty set. Each non-empty intersection corresponds to a network link connecting the two recipes sharing common ingredients in the intersection graph; (C) the intersection graph of recipes in which each link represents an intersection set of ingredients; (D) the trivial weighted network of recipes extracted from the intersection graph in panel (C); here, link weight indicates the number of common ingredients between recipes, i.e., the cardinality of the intersection; (E) the recipe similarity network (RSN) in which we compute the link weight using Eq. 3; the RSN is an undirected and weighted network where the link weight indicates the normalised average measure of ingredient similarities between recipes.

The recipe network with increasing overlapping threshold

The RSN is constructed using varying intersection threshold values, a process equivalent to removing links with weights below a specified threshold. This operation, known as link removal (or link attack), is called bond percolation in statistical physics30. Link removal is a valuable method for exploring various problems in network science31,32,33. This approach removes links with weights below the threshold, retaining only those links with higher weights. The weight \(\:w\) of a link reflects the similarity level between nodes (recipes) and increases with a higher intersection threshold. Links connecting recipes with greater ingredient overlap are stronger, indicating higher similarity.

Initially, the network is built for \(\:w>0\), where links are drawn if the intersection of ingredient sets between recipes is not empty (\(\:\cap\:\ne\: \emptyset\)), corresponding to at least one shared ingredient. At this stage, the network represents the most connected recipe network, capturing all possible links based on minimal recipe similarity. Subsequent networks are generated for progressively higher thresholds. For example, the network at \(\:w>0.1\) includes only links where the weight \(\:w\) is higher than 0.1, implying a more substantial intersection between the connected nodes. Similarly, the network at \(\:w>0.2\) considers links with \(\:w>0.2\), and this pattern continues for higher thresholds.

This approach highlights how the network connectivity decreases as the criteria for recipe similarity become more severe, providing insight into the clustering and fragmentation dynamics within the RSN.

The network properties

We analysed the RSN by adopting the basic properties of the complex network theory. Below, we outline the network properties applied in the analysis:

Node degree

The degree of a node represents the number of links connected to it16,34,35. The node degree is the most straightforward measure of node importance, accounting for how many links a node has. In the RSN, the degree \(\:k\) of a node indicates the number of recipes that share at least one common ingredient with the corresponding recipe. Nodes with higher degrees are also more central in the network.

Node strength

The strength of a node is the sum of the weights of its links11,16. Node strength is the weighted counterpart of the node degree and is also named the weighted node degree16. Node strength reflects both the number of links and their respective weights, offering a more nuanced measure of node importance11. In the RSN, node strength represents the total ingredient similarity of a recipe with all other recipes, as computed using Eq. (3).

Diameter

The network diameter is a structural measure based on the notion of node distance. The distance between nodes in the network is the minimum number of links to travel from one node to the other29. The distance between nodes is also called the shortest path length. The diameter of the network (also called the longest geodesic) is the longest distance to travel between a couple of nodes16. In the RSN, a larger diameter indicates that recipes are more distantly related in terms of ingredient similarity.

The largest connected component (LCC)

The largest connected component (LCC) is a widely used measure of network functioning34,35,36. The LCC is also known as the giant component, and it accounts for the highest number of connected nodes in the network. In the recipe network, the LCC reflects the maximum number of recipes that are connected through shared ingredients. This measure does not account for link weight heterogeneity, focusing solely on topological connectivity.

Recipes communities by finding cliques in the network

Clique identification is a central technique in community detection for complex networks37,38,39. A clique is a subset of nodes where a link directly connects every pair, forming a complete subgraph. Cliques are pivotal for understanding cohesion, clustering, and tightly-knit groups in networks40.

Formally, in graph theory, a \(\:k\)-clique is a subset of nodes where every pair of nodes is connected by a link. For instance, a 3-clique (triangle) is a complete subgraph of three nodes and represents the smallest possible clique in a simple network; 4-clique is a fully connected subgraph of four nodes, often referred to as a quadrilateral.

In weighted networks, a weighted clique forms a complete subgraph where link weights represent the intensity, cost, or strength of relationships. A maximum-weighted clique maximises the sum of link weights, while a threshold clique includes links where all weights exceed a specified threshold.

Identifying cliques in the RSN after removing links with weights lower than a specified threshold value (see Sect. 2.4 above) is a threshold clique detection that allows us to find subsets of nodes with each link weight value higher than the threshold. In our RSNs, the weight of the links represents the level of similarity between nodes (recipes). Finding cliques after removing links weaker than the threshold reveals sets of recipes with a defined minimum level of similarity. These subsets of recipes, defined by an arbitrary minimum similarity threshold, can be interpreted as recipe communities based on ingredient similarity.

Results and discussion

Comparison of different approaches to network construction

This section examines how varying methodologies influence the structure of the RSN derived from the cookbook database. Specifically, we analyse the centrality of nodes in the RSN built from the ‘Corpus del patrimoni culinari català’ (Ctrad), comparing results obtained with and without substituting recipes/ingredients with their constituent ingredients. In complex networks, node centrality measures a node’s importance or influence, often using metrics such as degree and strength to assess this from different perspectives33,41,42.

Here, we use node degree, representing the number of links connected to a node16, and node strength (weighted degree), representing the sum of the link weights connected to a node33. These metrics quantify the topological centrality, indicating the relative importance of nodes in the network.

Table 2 lists the 20 nodes with the highest degree (\(k\)) and strength (\(s\)) in the Ctrad RSN before (no substitution) and after (substitution) replacing recipes/ingredients with their basic components. The substitution affects node rankings for both metrics. For instance, by degree centrality, the top-ranked node changes from node 175 (no substitution) to node 905 (with substitution). Similarly, the highest-ranked node changes from node 144 (no substitution) to node 55 (with substitution) for strength centrality.

Node 55 becomes the most central by strength after substitution but is absent from the top 20 before substitution. Node 55 represents the “Allioli” recipe, a traditional Catalan sauce made primarily of garlic, olive oil, and salt. Known for its distinct flavor and creamy texture, Allioli is a representative sauce of the Catalan cuisine used for meat, vegetables, rice or pasta dishes. Substituting recipes with their ingredients significantly increases Allioli’s similarity to other recipes, increasing its centrality. This result highlights Allioli’s role in traditional Catalan cuisine as it is made with three of its most common ingredients, reflected by its highest strength in the substituted network.

These changes underscore the importance of methodological choices in constructing RSN. For example, replacing recipes/ingredients with their basic components resolves inconsistencies where nodes might simultaneously represent recipes and their ingredients (e.g., mayonnaise). Without such substitution, the same entity could appear as both a recipe/node and an ingredient in other recipes, introducing ambiguity into the network’s structure. Considering and clarifying how recipes/ingredients and their basic components are handled is particularly important when constructing networks from online recipe databases20,21,43, where each user can input recipes/ingredients without specifying what they consider to be the basic ingredients.

To build the recipe network, we may use the simple ingredients intersection. However, this approach doesn’t consider the overall number of ingredients in each recipe. Instead, we opt for a more nuanced approach that normalises link weight using a similarity measure that accounts for shared and total ingredients. We find that this choice significantly influences the recipe network structure.

Table 3 shows the ten nodes with the highest strength (\(s\)) in the three cookbooks before (Not norm) and after (Norm) normalisation using Eq. 3. Normalisation alters node rankings across all networks. For instance, in the 101 network, node 3 is the Allioli, a recipe composed of just three ingredients, that rises to the top after normalisation despite not being in the top 10 initially.

In the Ctrad network, before normalisation, the recipe “Platillo de pollastre amb mandonguilles i bolets” (a rich dish combining chicken, meatballs, mushrooms, and various seasonings with 19 ingredients) holds the highest strength. After normalisation, Allioli becomes the most central node in the RSN. This change reflects how normalisation accounts for ingredient set sizes: before normalisation, link weights depend on the intersection size of recipe ingredients, favoring recipes with many ingredients. After normalisation, the similarity is calculated independently of ingredient set size and may favor recipes with fewer, widely shared ingredients, like Allioli.

Previous studies have employed various methods to connect ingredients within networks. For example, Ahnert et al.20 linked ingredients based on shared aromatic compounds, using the number of shared compounds as link weights but without considering the total number of compounds per ingredient. Similarly, Caprioli et al.28 connected ingredients co-occurring in recipes with link weights based on their frequency of co-occurrence, again without accounting for the total ingredient set size. While effective, these approaches do not normalise link weights relative to the total size of ingredient or aromatic compound sets, which may alter network structure and centrality metrics. Calculating link weights while considering ingredient set sizes may ensure a more balanced representation of relationships within the network, ultimately enhancing the reliability of node importance assessments.

Our findings demonstrate that the choice of methodology, substitution of ingredients and link weight normalisation, impacts the resulting network’s structure and node centrality. Defining and applying appropriate methods to compute link weight in the network is critical, as these decisions influence key outcomes, such as node rankings and identifying essential recipes.

The recipes network properties

The statistical properties of the three RSNs are summarised in Table 4. The Ctrad RSN is the largest, with 622 nodes/recipes and 184,799 links, followed by the 101 network, with 100 nodes/recipes and 4052 links. The smallest is the Roca network, with 57 nodes/recipes and 1594 links. The average link weight \(\:<w>\) is approximately 0.38 for both the Ctrad and 101 RSNs and slightly lower at 0.32 for the Roca network.

The connectance (C) quantifies the degree of interconnectedness within a network44. It is calculated as \(\:C=\frac{L}{N\cdot(N-1)}\), representing the density of observed links relative to the total possible links. The connectance values for the Ctrad and Roca networks are near their maximum possible values and are also very high for the 101 network. This indicates that most recipes in the RSNs share at least one ingredient. In other words, the RSNs exhibit interconnectedness close to a complete graph, where all nodes are linked.

The node degree (\(\:k\)), representing the number of links connected to a node16, is high on average, reflecting the high connectivity of the RSNs. The node strength (\(\:s\)), or weighted degree, is the sum of the link weights of a node33. The average node strength (\(\:<s>\)) is lower than the average node degree (\(\:<k>\)), as expected since link weights in recipe networks range between 0 and 1.

The network diameter (\(\:D\)), the longest distance between any two nodes16, is very small for all recipe networks. It is \(\:D\)=3 for the Ctrad and 101 networks and \(\:D\)=2 for the Roca network. The largest connected component (\(\:LCC\)) encompasses all nodes (\(\:N\)) in each network, showing that the RSNs are globally connected.

These statistical properties demonstrate that the recipe networks, when constructed using the lowest similarity threshold, such as the presence of just a single shared ingredient to draw links, exhibit a high level of connectivity, with dense interrelationships between nodes and a structure approaching that of a fully connected graph.

The RSN features increasing the intersection threshold

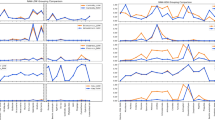

Figure 2 depicts how key network properties evolve as a function of the intersection threshold \(\:t\), which controls the minimum required ingredient overlap between recipes to establish a link. As \(\:t\) increases, weak links are progressively removed, leading to a sharp decline in connectivity metrics, including the number of links \(\:L\), average degree \(\:<k>\) and average node strength \(\:<s>\). This effect is observed in all three networks but is most pronounced in the Roca RSN, where a significant collapse occurs already for \(\:t\)>0.2.

Structural properties of the three recipe networks as a function of the intersection threshold (\(t\)). The x-axis values indicate that the intersection graph is built with increasing \(\:t\). By increasing \(\:t\), we remove weaker links from the network, performing a link removal analysis of the network’s structural properties. We remove links with weight \(\:w<t\). \(\:t\)=0 indicates that we hold links with \(\:w>0\), and it corresponds to the original network; \(\:t=0.1\) indicates that we hold links with \(\:w>0.1\) and remove links of \(\:w\le\:0.1\); \(\:t=0.2\) indicates that we hold links with \(\:w>0.2\) and remove links of \(\:w\le\:0.2\), and so on. Network structural indicators keys: number of links (\(\:L\)), average link weight (\(\:<w>\)), node degree (\(\:<k>\)), node strength (\(\:<s>\)), network diameter (\(\:D\)) and largest connected component (\(\:LCC\)). Each structural property is normalised by the maximum value for that indicator. Cookbook keys are: Corpus del patrimoni culinari català (CTrad), El Celler de Can Roca (Roca), 100 Plats indispensables de la cuina catalana (101).

This observation suggests that Roca recipes tend to have fewer common ingredients with each other, reinforcing the hypothesis that haute-cuisine recipes are more individualised and specialised, compared to traditional cookbooks. The faster decay in connectivity for Roca indicates that its links are weaker and less uniformly distributed, leading to a network that disintegrates more rapidly as stricter similarity criteria are imposed.

The average link weight \(\:<w>\), on the other hand, increases with \(\:t\), reflecting the removal of weak connections and the retention of stronger, more meaningful links. However, once \(\:t\) exceeds a certain value, the network becomes too sparse, and \(\:<w>\) collapses as no links remain, thus indicating that even the strongest similarities are too rare to sustain network connectivity under high-threshold conditions.

The network diameter \(\:D\), which captures the maximum distance between any two connected recipes, remains stable at low thresholds but increases sharply at critical values of \(\:t\), signaling network fragmentation. Once the largest connected component (\(\:LCC\)) begins to break down, \(\:D\) typically reaches a peak and then declines as only small, tightly connected clusters remain. The thresholds at which \(\:D\) peaks, \(\:t\)=0.5 for Roca, \(\:t\)=0.6 for 101, and \(\:t\)=0.75 for Ctrad, represent points of structural transition, where the network shifts from a globally connected structure to a set of isolated recipe communities.

The faster fragmentation of the Roca network is further supported by its lower average link weight (Table 4), and its left-shifted link weight distribution (Fig. 3). This distribution, bell-shaped but skewed toward lower values for Roca, confirms that ingredient overlap is weaker and less frequent in haute cuisine. In contrast, the 101 and Ctrad networks maintain stronger internal connectivity across a broader range of thresholds, suggesting greater homogeneity in ingredient usage within traditional Catalan cooking.

Link weight (\(\:w\)) frequency distribution for the three recipe networks. X-axis: link weight \(\:w\); Y-axis: probability \(\:P\left(w\right)\) to have a link weight of \(\:w\) value. Cookbook keys are: Corpus del patrimoni culinari català (CTrad), El Celler de Can Roca (Roca), 100 Plats indispensables de la cuina catalana (101).

Figure 4 provides a visual progression of the Roca RSN under increasing thresholds. As \(\:t\) rises, the network transitions from a densely connected graph (\(\:w\)>0) to a fragmented structure where only tightly similar recipes remain linked (\(\:w\)>0.2, \(\:w\)>0.3, etc.). This percolation-like process highlights the emergence of highly cohesive subgroups of recipes potentially reflecting thematic or functional clusters such as sauces, desserts, or meat dishes with consistent ingredient bases.

The Roca recipe network with increasing overlapping threshold. During the percolation process, as the intersection threshold used to construct the network increases, the weight \(\:w\) of the links grows. Thus, the similarity between the nodes/recipes connected by the links increases. The first graph, \(\:w>0\), indicates the recipes network where links are drawn if the recipes intersection is not empty (\(\:\cap\:\ne\: \emptyset\)), e.g., where at least one ingredient is in common. The graph for \(\:w>0.1\) indicates the recipes network where links among nodes are drawn if the weight \(\:w\) is above 0.1. The graph for \(\:w>0.2\) indicates the recipes network where links among nodes are drawn in the case the weight \(\:w\) is above 0.2, and so on. The last chart depicts the largest connected component (LCC) along the overlapping threshold.

These isolated components are not artefacts, but rather meaningful communities, identified through increasingly strict similarity criteria. They can be interpreted as culinary modules, where shared ingredient profiles could correspond to shared gastronomic roles, preparation methods, or flavor profiles. This opens new possibilities for automatic classification of recipes, identification of canonical preparations, or ingredient-based recommendations.

In summary, this analysis illustrates how adjusting the similarity threshold provides a multiscale view of recipe similarity, and how haute cuisine exhibits structural differences in ingredient connectivity when compared to traditional cookbooks. The method also lays the foundation for advanced applications such as clustering of recipes by style, diet, or gastronomic function, and even cross-cultural comparisons of culinary systems.

The characterising recipes

Identifying the most central nodes in a network allows researchers in various scientific fields to gather essential information about the system being analysed41. In our RSN, the most central nodes represent the recipes that show the greatest overall similarity to other recipes in the collection. We can refer to these nodes as “characterising recipes” of the culinary style the recipe set represents. In Table 5, we list the most central node in the network according to the strength (\(\:s\)) of recipes for the three cookbooks. The characterising recipe with the highest strength in the network for the Ctrad is node 55. As discussed above, node 55 represents Allioli, a very traditional Catalan sauce made primarily from garlic and olive oil.

The characterising recipe for the Roca network is node 09_2, the recipe for the Becada amb brioix del seu salmís (Woodcock with brioche of its own sauce), a reinterpretation of haute cuisine by Joan Roca of a traditional dish from Catalan cuisine. The Becada amb brioix del seu salmís is a dish where the woodcock is prepared with a rich sauce, served with a brioche, which complements the flavors of the bird. Joan Roca has described the Becada as the dish that most represents his culinary philosophy, presenting the complete recipe in a journalistic feature dedicated to the renowned Catalan chef and his restaurant (R-225 La Cocina de los Sentidos 2014, https://www.revistarestauradores.com/recetas--cocina-de-los-sentidos). Identifying the most significant recipe in Roca’s cuisine validates the effectiveness of the network science methodology proposed in this study for characterising representative recipes within a specific culinary domain.

The ingredients statistical analyses

The analysis of ingredient frequency across the three cookbooks highlights significant ingredient usage patterns, emphasising commonalities and distinct culinary preferences. The ingredient frequency follows a highly right-skewed distribution, presenting a long and heavy right tail (Fig. 5). This would indicate that most ingredients occur a few times, and a few more common ingredients occur many times. In other words, most ingredients are used sparingly, while a select few dominate the recipes. In Table 6, we list the twenty most frequent ingredients and their frequency for the three cookbooks. Salt, olive oil, water, onion, and garlic are the most common ingredients in all the cookbooks. The data reveal that these ingredients are staples and universally dominant across all three cookbooks. These ingredients form the backbone of most recipes, reflecting their fundamental role in the Catalan culinary traditions (Ctrad and 101) and Catalan haute cuisine (Roca).

Ingredient frequency for the three cookbooks analysed. (Panels A-B) X-axis: \(\:f\:\)frequency of the ingredient in recipes; Y-axis: \(\:N\left(f\right)\) number of ingredients showing frequency \(\:f\). (Panel D) X-axis: \(\:p\:\)normalised frequency of the ingredient in recipes (normalised by the total number of recipes in the cookbook); Y-axis: \(\:P\left(p\right)\) probability to have that ingredient frequency showing frequency \(\:f\). Cookbook keys are: Corpus del patrimoni culinari català (CTrad), El Celler de Can Roca (Roca), 100 Plats indispensables de la cuina catalana (101).

The Roca cookbook presents some peculiar, highly frequent ingredients not in the Ctrad and 101 recipes. The Roca cookbook stands out for its inclusion of unique, high-frequency used ingredients such as technologic ingredients (xanthan gum, agar-agar, and kudzu) or gastronomic ingredients like truffle, which are absent or not common in the other cookbooks. The presence of new and uncommon ingredients reflects a modernist culinary style, incorporating innovative techniques and ingredients that shape avant-garde cuisine as opposed to everyday cooking.

Ingredients communities

The analysis of recipe communities using clique detection in the RSN revealed several key insights into the structural organisation of recipes based on their ingredient similarity. A clique is a highly cohesive substructure, defined as a complete subgraph where every pair of nodes is connected by a link37,38. By identifying cliques, we can uncover tightly knit groups of recipes that share significant similarities in their ingredient composition.

The RSN for \(\:w>0\) (Fig. 6A) showed a high level of connectivity, indicating that most recipes share at least one ingredient. In general, RSNs show high connectivity at low thresholds. We expect lower connectivity and an increasing number of disconnected nodes for a higher threshold. Applying a stricter similarity threshold (\(\:w>0.6\)) revealed a more fragmented network structure (Fig. 6B). Several nodes became disconnected (green nodes), while the remaining recipes formed the largest connected component (\(\:LCC\), red nodes). The \(\:LCC\) emerging at a higher threshold connects only closely related recipes.

Recipe communities by finding cliques in the network. (A) 101 recipe network for \(\:w>0\), i.e., there is a link between nodes if there is at least one ingredient in common (\(\:\cap\:\ne\: \emptyset\)). The 101 recipe network for \(\:w>0\) shows a very high connectivity among nodes. (B) 101 recipe network for \(\:w>0.6\), i.e., there is a link between nodes that have weight \(\:w>0.6\). The 101 recipe network built with this link weight threshold presents disconnected nodes (green nodes), and the remaining nodes form the largest connected component (\(\:LCC\), red nodes). (C) \(\:LCC\) of the 101 recipe network for \(\:w>0.6\), where we outline a 7-clique, i.e., a complete graph of 7 nodes. (D) The 7-clique with the node identities. In our recipe networks, the weight of the links represents the level of similarity between nodes/recipes. The 7-clique in Fig. 6C is a subset of connected recipes with >0.6, thus presenting a high level of similarity. (E) Table listing the recipes composing the 7-clique.

Within the \(\:LCC\) for \(\:w>0.6\), we performed a clique detection, finding a 7-clique, i.e., a fully connected subnetwork of seven nodes (Fig. 6C). This subset represents a tightly-knit community of highly similar recipes (\(\:w>0.6\)), indicating that these recipes share a significant proportion of their ingredients. We depict the 7-clique with node identities in Fig. 6D and detail the composing recipes in Fig. 6E. These recipes represent a cohesive culinary group characterised by overlapping ingredients such as garlic, oil, and salt alongside complementary proteins (fish, seafood, and meats) and starchy bases (potatoes, rice, or beans). The presence of the 7-clique highlights how traditional recipes often cluster based on a core set of ingredients that define regional cuisines. Garlic, oil, and salt emerge as unifying components in Catalan cooking. Despite their base of common ingredients, the recipes in the 7-clique exhibit a wide variety of culinary expressions, ranging from simple sauces (Allioli) to complex dishes like country-style rice or monkfish stew. This underscores the versatility of the shared ingredient base in creating diverse culinary outcomes. What accounts for the variety of recipes with a common ingredient core? Recipes often start with a standard base of ingredients (such as garlic, oil, and salt) and then diverge based on a few distinctive elements. For example, “Monkfish stew” and “Potato and bean stew” both include water, garlic, salt, and oil. However, they are vastly different dishes due to the inclusion of monkfish (Lophius piscatorius) in one and beans and potatoes in the other. Understanding the clique structure of the network can inform recipe development, suggesting potential ingredient substitutions or combinations that align with traditional flavor profiles while fostering innovation.

In practical terms, this analysis opens the door to developing a culinary recommender system or a recipe generation algorithm.

A concrete example: using the 7-clique structure we identified (which includes recipes such as “Allioli,” “Monkfish stew,” and “Potato and bean stew”), the system could generate a novel hybrid recipe that combines the shared base ingredients with complementary elements drawn from different recipes in the clique, such as fish and potatoes. This could lead to the creation of a novel, non-catalogued dish, such as “Garlic and potato cream with steamed fish bites”, which, although absent from the original dataset, aligns with the flavor profiles and ingredient patterns identified in the network, thereby remaining consistent with the culinary style of the cookbook.

In summary, this model not only maps the semantic cohesion of existing recipes but also provides a structured framework for the guided creation of new recipes, respecting traditional flavor profiles while encouraging culinary innovation.

Conclusions

The application of network science and intersection graph theory to Catalan cuisine reveals critical insights into the interconnectedness and diversity of culinary traditions. Traditional RSNs demonstrate high connectivity, indicating higher recipe similarity, while haute cuisine RSN exhibit lower connectivity, reflecting their specialised and unique nature.

Our findings highlight that choosing methods to build the recipe networks from data, including ingredient substitution and link weight normalisation, significantly influences network structure and node centrality. Defining and applying appropriate methods is essential to accurately rank nodes and identify key recipes in RSNs.

We identified key nodes/recipes using node centrality metrics from network science, discovering characterising recipes that represent each culinary style’s essence.

Additionally, clique-based community detection reveals ingredient-based clusters that highlight traditional culinary patterns and potential innovation pathways.

The similarity measure used in this study provides a simple and interpretable representation of recipe similarity. However, it can be considered an ad hoc choice. An alternative approach could leverage statistical physics. For instance, treating the network as an ensemble of randomised realisations would allow us to assess whether the observed link weights between recipes reflect meaningful similarity or merely random chance. Future work should explore the impact of more principled network models, such as the configuration model for weighted networks45,46, on the topology and interpretability of the resulting similarity networks. Additionally, employing different similarity measures may lead to distinct network structures. We plan to investigate how alternative similarity metrics, such as the Jaccard or Bray–Curtis indices47, influence the resulting network topology.

A limitation of the present RSN construction is that all ingredients are treated uniformly without accounting for their frequency across recipes. Common ingredients such as salt, water, or olive oil are omnipresent and thus may contribute less to recipe similarity than rare ingredients. Incorporating ingredient frequency into the similarity computation may reduce this bias and provide a more discriminative network structure. Future work should address this by weighting ingredient contributions, for example, by considering the ingredient contribution inversely to its frequency. An interesting framework would also involve constructing a bipartite network connecting recipes and ingredients as two distinct node types. This representation, common in the literature20,48,49, would enable projection methods and statistical modelling that capture ingredient–recipe relationships.

Our findings highlight the importance of network-based approaches for analysing culinary heritage, while also facilitating practical applications in gastronomy, such as personalised recipe recommendations and fostering culinary innovation. The proven success of AI-driven methods in emulating creative processes, such as writing, poetry, painting, and music, has amplified interest in their application to the culinary domain, particularly for developing innovative and flavorful recipes1. Future research should explore the extension of these methodologies to diverse cuisines and their direct implementation in AI-driven culinary and gastronomic practices. In particular, the recipe similarity network we construct, with recipes as nodes and shared ingredients as weighted links, could be useful as input for graph-based machine learning models. For example, one could apply a graph neural network (GNN) to predict missing links or to recommend new recipe combinations based on ingredient similarity.

Data availability

The data of recipe networks will be available upon personal request to the corresponding author.

References

Bagler, G. Can AI give you the recipe for a perfect dish? Nat. India. https://doi.org/10.1038/d44151-024-00109-4 (2024).

Ahnert, S. E. Network analysis and data mining in food science: the emergence of computational gastronomy. Flavour 2 (2013).

Doğan, M. & Değerli, A. H. Computational gastronomy: A study to test the food pairing hypothesis in Turkish cuisine. Int. J. Gastron Food Sci. 33, 100795 (2023).

Wagner, C., Singer, P. & Strohmaier, M. The nature and evolution of online food preferences. EPJ Data Sci. 3, 1–22 (2014).

Hooton, F., Menichetti, G. & Barabási, A. L. Exploring food contents in scientific literature with foodmine. Sci. Rep. 10 (2020).

Jain, A., K, N., Bagler, G. & R. & Analysis of food pairing in regional cuisines of India. PLoS One. 10, e0139539 (2015).

Goel, M. & Bagler, G. Computational gastronomy: A data science approach to food. J. Biosci. 47, 12 (2022).

Bagler, G. & Goel, M. Computational gastronomy: capturing culinary creativity by making food computable. NPJ Syst. Biol. Appl. 10, 72 (2024).

Gilal, N. U. et al. Evaluating machine learning technologies for food computing from a data set perspective. Multimed Tools Appl. 83, 32041–32068 (2023).

Albert, R. & Barabási, A. L. Statistical mechanics of complex networks (2002).

Bellingeri, M., Bevacqua, D., Scotognella, F. & Cassi, D. The heterogeneity in link weights May decrease the robustness of real-world complex weighted networks. Sci. Rep. 9 (2019).

Montepietra, D., Bellingeri, M., Scotognella, F. & Cassi, D. Modeling the photosynthetic system I as complex interacting network. BioRxiv Preprint At. https://doi.org/10.1101/2020.05.02.074377 (2020).

Bellingeri, M., Lu, Z. M., Cassi, D. & Scotognella, F. Analyses of the response of a complex weighted network to nodes removal strategies considering links weight: the case of the Beijing urban road system. Mod. Phys. Lett. B 32 (2018).

Onnela, J. P. et al. Structure and tie strengths in mobile communication networks. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U S A. 104, 7332–7336 (2007).

Martinazzi, S. & Flori, A. The evolving topology of the lightning network: centralization, efficiency, robustness, synchronisation, and anonymity. PLoS One 15 (2020).

Boccaletti, S., Latora, V., Moreno, Y., Chavez, M. & Hwang, D. U. Complex networks: structure and dynamics. Phys. Rep. 424, 175–308 (2006).

Montoya, J. M., Pimm, S. L. & Solé, R. V. Ecological networks and their fragility. Nature 442, 259–264. https://doi.org/10.1038/nature04927 (2006).

Naughton, D. P., Nepusz, T. & Petróczi, A. Network analysis: a promising tool for food safety. Curr. Opin. Food Sci. 6, 44–48 (2015).

Herrera, J. C. S. The contribution of network science to the study of food recipes. A review paper. Appetite. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.appet.2020.105048 (2021).

Ahn, Y. Y., Ahnert, S. E., Bagrow, J. P. & Barabási, A. L. Flavor network and the principles of food pairing. Sci. Rep. 1 (2011).

Teng, C. Y., Lin, Y. R. & Adamic, L. A. Recipe recommendation using ingredient networks. in Proceedings of the 4th Annual ACM Web Science Conference 298–307 (Association for Computing Machinery, 2012). https://doi.org/10.1145/2380718.2380757

Erdös, P., Goodman, A. W. & Pósa, L. The representation of a graph by set intersections. Can. J. Math. 18, 106–112 (1966).

McKee, T. A. & McMorris, F. Topics in Intersection Graph Theory (Society for Industrial and Applied Mathematics, 1999).

Szpilrajn-Marczewski, E. Sur Deux propriétés des classes d’ensembles. Fundamenta Math. 33, 303–307 (1945).

Čulík, K. Applications of graph theory to mathematical logic and linguistics. in Theory of Graphs and its Applications (Proc. Sympos. Smolenice) 13–20 (Publishing House of the Czechoslovak Academy of Sciences, 1964).

Kular, D. K., Menezes, R. & Ribeiro, E. Using network analysis to understand the relation between cuisine and culture. in IEEE Network Science Workshop 38–45 (2011). https://doi.org/10.1109/NSW.2011.6004656.

Simas, T., Ficek, M., Diaz-Guilera, A., Obrador, P. & Rodriguez, P. R. Food-bridging: A new network construction to unveil the principles of cooking. Frontiers ICT 4 (2017).

Caprioli, C. et al. The networks of ingredient combination in cuisines around the world. Preprint At. https://doi.org/10.48550/arXiv.2408.15162 (2024).

Buckley, F. & Harary, F. Distance in Graphs (Addison-Wesley Publishing Company, 1990). https://doi.org/10.1201/b16132-64

Hu, Y. et al. Local structure can identify and quantify influential global spreaders in large scale social networks. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U S A. 115, 7468–7472 (2018).

Mengiste, S. A., Aertsen, A. & Kumar, A. Effect of edge pruning on structural controllability and observability of complex networks. Sci Rep 5 (2015).

Sun, S., Liu, X., Wang, L. & Xia, C. New link attack strategies of complex networks based on k-Core decomposition. IEEE Trans. Circuits Syst. II Express Briefs. 67, 3157–3161 (2020).

Bellingeri, M. et al. Considering weights in real social networks: A review. Front. Phys. 11 (2023).

Iyer, S., Killingback, T., Sundaram, B. & Wang, Z. Attack robustness and centrality of complex networks. PLoS One 8 (2013).

Bellingeri, M., Cassi, D. & Vincenzi, S. Efficiency of attack strategies on complex model and real-world networks. Phys. A: Stat. Mech. Its Appl. 414, 174–180 (2014).

Wandelt, S., Sun, X., Feng, D., Zanin, M. & Havlin, S. A comparative analysis of approaches to network-dismantling. Sci Rep 8 (2018).

Farkas, I. J., Ábel, D., Palla, G. & Vicsek, T. Weighted network modules. New J. Phys 9 (2007).

Kumpula, J. M., Onnela, J. P., Saramäki, J., Kertész, J. & Kaski, K. Model of community emergence in weighted social networks. Comput. Phys. Commun. 180, 517–522 (2009).

Kumpula, J. M., Kivelä, M., Kaski, K. & Saramäki, J. Sequential algorithm for fast clique percolation. Phys. Rev. E. 78, 26109 (2008).

Sajjadi, S. J., Qian, X., Zeng, B. & Adl, A. A. Network-Based methods to identify highly discriminating subsets of biomarkers. IEEE/ACM Trans. Comput. Biol. Bioinform. 11, 1029–1037 (2014).

Lü, L. et al. Vital nodes identification in complex networks. Phys. Rep. 650, 1–63. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.physrep.2016.06.007 (2016).

Lü, L., Zhou, T., Zhang, Q. M. & Stanley, H. E. The H-index of a network node and its relation to degree and coreness. Nat Commun 7 (2016).

Caprioli, C. et al. The networks of ingredient combination in cuisines around the world (2024).

Bellingeri, M. & Vincenzi, S. Robustness of empirical food webs with varying consumer’s sensitivities to loss of resources. J. Theor. Biol. 333, 18–26 (2013).

Newman, M. & Networks An Introduction. Preprint at (2010). https://doi.org/10.1093/acprof:oso/9780199206650.001.0001

Mastrandrea, R., Squartini, T., Fagiolo, G. & Garlaschelli, D. Enhanced reconstruction of weighted networks from strengths and degrees. New. J. Phys. 16, 43022 (2014).

Legendre, P. & Legendre, L. Numerical Ecologyvol. 24 (Elsevier, 2012).

Guillaume, J. L. & Latapy, M. Bipartite graphs as models of complex networks. Phys. A: Stat. Mech. Its Appl. 371, 795–813 (2006).

Saracco, F., Di Clemente, R., Gabrielli, A. & Squartini, T. Randomizing bipartite networks: the case of the world trade web. Sci. Rep. 5, 10595 (2015).

Funding

This research is funded by Ecosister project, funded under the National Recovery and Resilience Plan (NRRP), Mission 4 Component 2 Investment 1.5 - Call for tender No. 3277 of 30/12/2021 of Italian Ministry of University and Research funded by the European Union – NextGenerationEU Award Number: Project code ECS00000033, Concession Decree No. 1052 of 23/06/2022 adopted by the Italian Ministry. We acknowledge the CINECA award under the ISCRA initiative for the availability of high-performance computing resources and support. Agència de Gestió d’Ajuts Universitaris i de Recerca (grant 2021SGR00671) and Ajuntament de Santa Coloma de Gramenet. Axel Bidon-Chanal Badia and Marta Vila Rigat would like to acknowledge the participation of CLiC (Centre Llenguatge i Computació) and Ramon Garcia, Ivó Pujiula Mora, Èlia Climent Figuerola, Mar Saló Garí, Maria Pérez Leiva and Marina Maragda Ferrer Gracia in the initial project of ingredient annotation.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

M.B. wrote the simulation codes, performed the statistical analyses, drew the figures, and developed the tables. M.B., R.A., and M.T. performed the simulation analyses. R.A. and M.T. performed the simulation analyses on the HPC cluster of Parma University and the CINECA Leonardo supercomputer. A.B.C and M.V.R. organized and created the ingredients databases. D.C. and A.B.C. conceived the research. D.C. introduced the intersection graph analysis and the similarity weight. M.B. wrote the first manuscript. M.B., D.C., and A.B.C. revised the final version of the manuscript.

Corresponding authors

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher’s note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Supplementary Information

Below is the link to the electronic supplementary material.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if you modified the licensed material. You do not have permission under this licence to share adapted material derived from this article or parts of it. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Bellingeri, M., Bidon-Chanal Badia, A., Rigat, M.V. et al. The recipe similarity network: a new algorithm to extract relevant information from cookbooks. Sci Rep 15, 34380 (2025). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-17189-6

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-17189-6