Abstract

In recent years, the prevalence of obesity in children has increased rapidly, resulting in insulin resistance (IR) and metabolic dysfunction-associated steatotic liver disease (MASLD) being diagnosed with increasing frequency. The main objective of this study was to evaluate the phospholipids and fatty acids of erythrocyte cell membranes in overweight and obese children. Subsequently, patients with MASLD and IR were selected. The structural properties of the erythrocyte membrane were determined in the red blood cells using the gas–liquid chromatography method. This prospective analysis included a cohort of 68 children, among whom IR was identified in 72.06% and MASLD in 57.35% of cases. No significant differences in membrane lipid profile were observed between MASLD and non-MASLD groups. Sphingomyelin (SM) polyunsaturated fatty acids (PUFA), SM n-6 PUFA, and SM n-6/n-3 PUFA values were significantly higher in the group with IR. The group with homeostasis model assessment of insulin resistance > 2.5 also had higher values of phosphatidylethanolamine (PE) PUFA, PE n-3 PUFA and PE n-6 PUFA. These findings suggest that insulin resistance may be associated with specific changes in erythrocyte membrane lipid composition. Further studies on a larger group of patients are needed to confirm this association.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

As the prevalence of obesity increases, metabolic dysfunction-associated steatotic liver disease (MASLD) is observed to become the predominant liver disease among children. Based on previous studies, MASLD may affect up to a quarter of the pediatric population. Moreover, disease progression to fibrosis/cirrhosis has also been reported among children1,2. Insulin resistance (IR) and lipotoxicity have been described as the most important mechanisms involved in the pathogenesis of metabolic abnormalities and the development of MASLD3.

Currently, criteria for MASLD are based on the finding of cardiometabolic risk factors (excess body weight, hyperglycemia, hypertension, hypertriglyceridemia or reduced high-density lipoprotein cholesterol (HDL-C)) and liver steatosis detected by imaging or biopsy4. Children and adolescents are a special group of patients, as onset at a younger age can result in a more severe course of the disease5. Therefore, in the pediatric group, prompt recognition and monitoring of disease progression is very important.

Excess body fat plays an important role in the development of IR. Patients with IR require higher concentrations of insulin to maintain proper glucose uptake and utilization. Chronic persistence of high insulin concentrations may serve a key role in the pathogenesis of metabolic disorders. IR has been found to play an important role in the development of hepatic steatosis by participating in lipogenesis, impairing the inhibition of lipolysis and stimulating the secretion of adipokines and other cytokines6. In addition, MASLD is considered a hepatic manifestation of the metabolic syndrome7.

Liver fat accumulation is a major process in MASLD, so assessment of lipid abnormalities is a very important issue. Taking this into account, numerous studies have been conducted on serum lipid analysis of patients with hepatic steatosis, both among children and adults8,9. The lipid composition of erythrocyte cell membranes (ECM) also deserves attention in the analysis of metabolic disorders. Cell membranes are composed of sterols, fatty acids (FA), which form phospholipid fractions (phosphatidylcholine (PC), phosphatidylethanolamine (PE), phosphatidylserine (PS), phosphatidylinositol (PI) and sphingomyelin (SM))10. Studying the lipid composition of the ECM provides additional information on the metabolic pathways involved in lipid metabolism and can be used to investigate the relationship between patterns of fatty acids and phospholipids and disease occurrence or progression. It should be noted that the FA composition of red blood cell (RBC) membranes is similar to that of hepatocytes, containing saturated monounsaturated, ω-6 and ω-3 polyunsaturated FAs11. Moreover, erythrocytes are the most abundant blood cells that can interact with various organs. Given these observations, analysis of the lipid profile of ECM may be helpful in diagnosing and monitoring obesity-related diseases. Previous analyses have observed changes in the erythrocyte lipid profile in obesity and obesity-related diseases such as type 2 diabetes and hypertension in adults12,13,14. To date, no studies have been published on this topic among children as well as adults with MASLD.

Therefore, the purpose of our study was to analyze the lipid profile of EMC of children and adolescents meeting MASLD criteria compared to overweight and obese peers without liver pathology. Because of the impact of IR on the development of MASLD, we aimed to evaluate the phospholipids and FA of EMC in relation to with homeostasis model assessment of insulin resistance (HOMA-IR) values. Another focus of our study was to determine the correlation of membrane lipid parameters with biochemical markers of liver damage, carbohydrate metabolism and obesity.

Results

The prospective study included 39 (57.35%) children and adolescents diagnosed with MASLD and 29 (42.65%) overweight/obese controls (non-MASLD). The demographic data and laboratory results of each group are presented in Table 1. The parameters that were statistically higher in patients with MASLD were ALT, AST (p < 0.001), GGT activities (p = 0.006) and UA concentration (p = 0.02). While higher fasting glucose levels (p = 0.04) were observed in the group without MASLD, insulin and HOMA-IR values in both groups (p > 0.05) were comparable.

We observed no significant differences in the overall membrane lipid profile between the MASLD and non-MASLD groups (p > 0.05) (Table 2). Similarly, the analysis of total fatty acid concentrations in RBC membranes showed no statistically significant differences depending on the diagnosis of MASLD (Table 1 Suppl.). However, when examining individual FAs within specific lipid fractions, we found significantly higher levels of PE C18:3 (median: 3.68 vs. 4.91 pmol/mg of hemoglobin; p = 0.03) and PI C14:0 (median: 2.52 vs. 2.90 pmol/mg of hemoglobin; p = 0.02) in the non-MASLD group (Tables 2, 3, 4, 5 and 6 Suppl.).

Table 3 shows the characteristics of patients according to the presence of IR as assessed by HOMA-IR. Forty-nine (72.06%) children/adolescents had HOMA-RI higher than 2.5. Increased GGT (p = 0.03), TG (p = 0.01) and UA (p = 0.05) levels were noted in the IR group. On the other hand, elevated TC (p = 0.02) and LDL-C (p = 0.005) levels were observed in the group with HOMA-IR < 2.5. The incidence of MASLD was comparable in both groups (p > 0.05).

The lipid composition of erythrocyte membranes depending on HOMA-IR is shown in Table 4. The total amounts of all analyzed phospholipids were comparable in both groups. However, it should be noted that the values of SM polyunsaturated fatty acids (PUFA) (p = 0.02), SM n-6 PUFA (p = 0.01), and the SM n-6/n-3 PUFA ratio (p = 0.02) were significantly higher in the IR group. The group with HOMA-IR > 2.5 also had higher levels of PE PUFA (p = 0.008), PE n-3 PUFA (p = 0.006), and PE n-6 PUFA (p = 0.02). Moreover, individual fatty acids such as SM 18:2 (median: 2.11 vs. 1.60 pmol/mg of hemoglobin; p = 0.009), PE 20:4 (560.42 vs. 459.63 pmol/mg of hemoglobin; p = 0.005) and PE 22:6 (132.88 vs. 90.25 pmol/mg of hemoglobin; p = 0.003) were significantly elevated in the group with HOMA-IR > 2.5 group (Tables 2, 3, 4, 5 and 6 Suppl.). Despite these differences, the overall FA profile remained comparable between the groups with HOMA-IR > 2.5 and HOMA-IR < 2.5 (Table 1 Suppl.).

In order to investigate possible relationships between BMI, biochemical parameters and RBC lipid profile, Spearman’s rank correlation was performed in the whole group (n = 68). Only those phospholipids and fatty acids that had significantly different values according to the presence of IR (Table 4) were included in the correlation analysis. Positive correlations were observed between all analyzed phospholipids and HOMA-IR. What is more, the following significant correlations of SMn-6/n-3 PUFA and AST the same as PE n-6 PUFA and TC were noted, significant correlations with PE PUFA were found for LDL-C and UA; and significant correlations for n-3 PUFA were determined for GGT and UA. The correlations are summarized in Table 5.

Discussion

Despite the growing body of data on adult obesity, relatively fewer studies have been conducted on child and adolescent populations. Therefore, we decided to examine the lipid profile of ECM in overweight/obese children and adolescents in relation to clinical and laboratory data. Single studies on the composition of FAs of ECM have been conducted in pediatric patients15,16,17,18. One study evaluated only the total phospholipid composition, without distinguishing between individual phospholipid fractions (i.e., SM, PC, PE, PI, PS)19. To the best of our knowledge, no study has yet comprehensively evaluated the lipid profile of ECM in both adults and children with MASLD as well as IR. In our analysis, we assessed not only the phospholipid fractions, but also the individual fatty acids within each fraction. We divided the study group into two subgroups. The first group consisted of children with MASLD, and the second group consisted of children with IR assessed by HOMA-IR values. The lipid profile of ECMs was comparable between the MASLD and non-MASLD groups. However, significant differences were observed between patients depending on the presence of IR. Higher values of SM PUFA, SM n-6 PUFA, SM n-6/n-3 PUFA, as well as PE, PE n-3 PUFA, and PE n-6 PUFA were found in the group with HOMA-IR values > 2.5. The results may indicate the contribution of individual fatty acids, as well as phospholipids, to the presence of IR in children, which is a key factor in the development of metabolic disorders.

The molecular mechanisms underlying metabolic dysfunction and the development of IR remain still unclear. A recently published study using a targeted phospholipidomic approach observed that an increase in PE PUFA was a major feature of plasma phospholipid abnormalities associated with IR in adults20. Although our study focused on individuals younger than 18 years of age, we made similar observations. In another study, the author observed that among adults who were overweight but without diabetes, plasma insulin levels, as well as the presence of IR, were positively correlated with SM and PE content in the ECM. Moreover, multivariate regression analysis showed that PE and SM were independent predictors of insulin concentration and HOMA-IR values in both lean and obese subjects21. In contrast, in a study conducted on 9 adults with a BMI of 19.2–30.5 kg/m2, PC, but not PE, of skeletal muscle membranes was found to be of particular importance for the occurrence of IR. After administration of nicotinic acid (an inducer of IR), there was an increase in insulin levels, a decrease in peripheral insulin sensitivity, accompanied by a significant increase in PC and a decrease in n-3 FAs and PUFA22. Lee et al.23, observed that an important determinant of IR is an increased PC:PE ratio in skeletal muscle. The PC:PE ratio in skeletal muscle also correlated with intracellular lipid droplets, Ca2+ -ATP-ase of the endoplasmic reticulum, mRNA of oxidative enzymes and insulin receptors in the plasma membrane, suggesting a complex role for PC and PE in the development of IR. Based on our study and the results of the studies described above, we can conclude that changes in lipid levels are associated with IR, but there is no evidence to determine whether they are a cause or a consequence of metabolic abnormalities, thus it should be elucidated in further studies. In particular, the observed higher levels of PE n 3 PUFA in the IR group remain difficult to explain definitively. One possible explanation may be a compensatory mechanism, in which the body increases the incorporation of n 3 PUFA into membrane phospholipids (such as PE) as a protective response to metabolic stress and inflammation. This is supported by the known anti-inflammatory effects of n 3 PUFA, including the inhibition of NLRP3 inflammasome activation and the reduction of IL 1β secretion, which may enhance insulin sensitivity in the liver and adipose tissue24. However, further studies are needed to confirm these mechanisms.

There is also interest in evaluating the FA profile of ECMs in childhood obesity. Jauregibeitia et al.17, observed that membrane FA composition changed with age. Obese children had higher levels of n-6 FA and lower values of n-3 FA compared to adults, which may be related to the utilization of n-3 FA for the synthesis of cell membranes of the growing body. In our study, the two patient cohorts analyzed (with and without MASLD and with normal and abnormal HOMA-IR values) did not differ significantly in terms of age, which excludes the influence of age on our results. Another study noted that the FA profile of RBC membranes is also affected by BMI. Obese children had higher levels of n-6 PUFA and lower levels of MUFA compared to normal-weight peers15. Another study involving obese pediatric patients observed that metabolically healthy obese participants had a different FA composition of membranes than obese children with complications. The differences were mainly related to lower n-6 FA and n-6/n-3 FA values in the group without obesity-related complications16. It is well known that mediators derived from n-6 PUFA have been described in the literature as exacerbating inflammation, while obesity is considered a chronic inflammatory condition25. Our study included only obese children and adolescents, but interestingly, the group with abnormal HOMA-IR values had higher PE n-6 PUFA, PE n-6 PUFA and PE n-3 PUFA.

We did not observe differences in the composition of the membrane lipid profile in obese children and adolescents depending on the diagnosis of MASLD. Studies addressing this issue in children and adults are scarce. Bonafini et al.18, analyzing children with obesity, found an inverse correlation of n-6 PUFA of ECM with the hepatic steatosis index (calculated from BMI, waist circumference, TG, and GGT) and ALT. This study did not evaluate FA composition in relation to the presence of hepatic steatosis on imaging studies and the correlation of liver parameters with membrane FA. Therefore, it is difficult to compare the results of this study with our results. On the other hand, in a study involving adult patients with non-alcoholic fatty liver disease (NAFLD), there were no significant differences in membrane FA composition (i.e., PUFA, MUFA, and SFA) according to the degree of hepatic steatosis assessed by elastography. However, it was observed that severe NAFLD was associated with a significant decrease in saturation index, which was calculated as the ratio of stearic acid to oleic acid26. Another study involving adults with NAFLD found that after 6 months on an individualized diet, hepatic steatosis was less severe, ALT and AST values decreased, and ECM lipid composition changed. After dietary restriction, there was an increase in PUFA and a decrease in SFA in erythrocyte membranes27. Further studies are needed to determine whether the composition and FA changes of RBC can be a determinant of the severity of liver damage, as well as its progression to metabolic dysfunction-associated steatohepatitis (MASH).

Our study has several potential limitations. First, the number of patients was relatively small to draw firm conclusions. In addition, our study did not analyze participants’ dietary habits and physical activity, which could also have affected our results. Another limitation of the study was the lack of assessment of patients using the Tanner scale, a clinical tool used to determine pubertal stage. We should also mention the strength of our research. This is the first study in patients with MASLD and IR to examine the ECM lipid profile. The novelty of these results is a major strength of our study and may be a prelude to further analysis in this age group. It should also be noted that the patients included in our study did not have other metabolic complications of obesity, such as type 2 diabetes or hypertension, which excludes the influence of other diseases. Another strength of our study is that we assessed not only membrane lipid concentrations, but also analyzed associations between their levels and multiple clinical and biochemical parameters in children and adolescents with MASLD and IR.

Conclusion

In our study, we found differences in phospholipid profile, as well as FA composition in relation to IR. Surprisingly, the lipid profile of erythrocyte membranes of MALSD patients was not significantly different compared to obese peers without coexisting liver disease. Further studies on a larger group of patients are needed to determine the exact role of membrane lipids in the pathogenesis of IR and to confirm the usefulness of the ECM lipid profile in detecting and monitoring patients with IR.

Material and methods

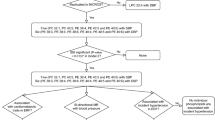

The study group

The prospective study included overweight or obese patients admitted to our department with suspected liver disease based on hepatomegaly or elevated liver enzymes or features of hepatic steatosis on ultrasound. According to the latest guidelines4,28, patients were divided into two groups (MASLD and non-MASLD) based on laboratory and ultrasound findings. Hepatic steatosis was diagnosed by abdominal ultrasonography. Subsequently, study participants were divided according to their HOMA-IR value (a value above 2.5 was considered IR29,30,31. Patients classified as non-MASLD had simple obesity, without other obesity-related comorbidities. Individuals with type 2 diabetes mellitus, arterial hypertension, obstructive sleep apnea, or any other condition beyond those listed as exclusion criteria—such as infectious hepatitis (A, B, C), infectious mononucleosis, autoimmune hepatitis and selected metabolic liver diseases (including Wilson’s disease, alpha-1-antitrypsin deficiency, and cystic fibrosis) were not included in the study. Patients using medications affecting blood pressure, lipid or carbohydrate metabolism, or consuming alcohol were also excluded.

All participants underwent a detailed medical history and physical examination with anthropometric measurements barefoot and wearing minimal clothing. Body mass index (BMI) was calculated by dividing weight (kg) by height squared (m2). Children were classified by BMI, using a pediatric age- and gender-specific z-score, as overweight (standard deviation (SD) score > 1) and obese (SD score > 2).

Written informed consent was obtained from the parents of all study participants, as well as from the patient if the participant was over the age of 13. The protocol was approved by the local bioethics committee (Medical University of Bialystok) before patient recruitment, and the study complied with the Helsinki Accords (approval number: R—002/384/2019).

Collection of samples for analysis

Blood samples were taken from all participants after a 10 h overnight fast. Two blood samples of approximately 2.7 ml each were collected. The first blood sample was used to assess membrane lipids (described below), while the second blood sample was used to measure biochemical parameters including alanine aminotransferase (ALT), aspartate aminotransferase (AST), gamma glutamyltransferase (GGT), total cholesterol (TC), low-density lipoprotein cholesterol (LDL-C), high-density lipoprotein cholesterol (HDL-C), triglycerides (TG), glucose, insulin and uric acid (UA). IR was assessed by HOMA-IR using the following formula: HOMA-IR = fasting insulin (μU/ml) × fasting plasma glucose (mmol/L)/22.5.

Red blood cells’ fatty acids and phospholipid measurements

The contents of different subclasses of phospholipid fraction (i.e., PC, PE, PI, PS, and SM) were determined in the red blood cells using the gas–liquid chromatography (GLC) method. In brief, erythrocytes were separated from plasma and other formed elements. Then, the red blood cells in the volume of 200 µl underwent extraction of lipids in a chloroform–methanol mixture (2:1, v/v). After overnight incubation, water was added to the mixture, and samples were centrifuged (10 min, 3000 rpm). Next, the lower organic layer was collected, and the total PL along with PC, PE, PI, PS, and SM subclasses were separated using thin-layer chromatography (TLC) on silica gel glass plates (Silica Plate 60, 0.25mm; Merck, Darmstadt, Germany) in a chamber containing resolving solution (chloroform/ methanol/acetic acid/water (50:37.5:3.5:2, v/v/v/v)). The above-mentioned lipid fractions were visualized under UV light, and corresponding gel bands were scrapped and collected. Later, to each sample internal standard was added, and thereafter, the procedure of transmethylation was performed using a 14% boron trifluoride-methanol solution with subsequent incubation at 100 °C for 30 min (PC, PE, PI, and PS fractions) or 90 min (SM fraction). After incubation, pentane was used to extract the fatty acid methyl esters and then evaporated under a steady stream of nitrogen gas. The last stage included dissolving the samples in 50 µl of hexane and analyzing with Hewlett–Packard 5890 Series II gas chromatograph, HP-INNOWax capillary column. The individual fatty acid methyl esters were identified and quantified using Agilent Technologies ChemStation software (version Rev. A.09.03) based on retention times and standard curves, respectively. The total contents of PC, PE, PI, PS, and SM subclasses were evaluated as the sum of individual fatty acids, i.e., myristic acid (C14:0), palmitic acid (C16:0), palmitoleic acid (C16:1), stearic acid (C18:0), oleic acid (C18:1), linoleic acid (C18:2), arachidic acid (C20:0), linolenic acid (C18:3), behenic acid (C22:0), arachidonic acid (C20:4), lignoceric acid (C24:0), eicosapentaenoic acid (C20:5), nervonic acid (C24:1), and docosahexaenoic acid (C22:6). The results were expressed as picomoles per milligram of hemoglobin (pmol/mg). In addition, in the examined phospholipid fractions, we calculated the total content of saturated fatty acids (SFAs; as the sum of C14:0, C16:0, C18:0, C20:0, C22:0, and C24:0), monounsaturated fatty acids (MUFAs; as the sum of C16:1, C18:1, and C24:1), polyunsaturated fatty acids (PUFAs; as the sum of C18:2, C18:3, C20:4, C20:5, and C22:6), n-3 PUFA (as the sum of C18:3, C20:5, and C22:6), and n-6 PUFA (as the sum of C18:2 and C20:4).

Statistical analysis

Statistical tests and calculations were performed using STATISTICA software. Continuous variables were summarized as median and quartiles (Q1–Q3) and compared using the Mann–Whitney U test; categorical variables were presented as number and percentage and compared using the Chi-square test. For the analysis of correlations between parameters, the Spearman’s rank correlation coefficient was applied. Statistical significance level was set at p < 0.05.

Data availability

The datasets generated and analyzed during the current study are available from the corresponding author on reasonable request.

References

Perumpail, B. J. et al. The prevalence and predictors of metabolic dysfunction-associated steatotic liver disease and fibrosis/cirrhosis among adolescents/young adults. J. Pediatr. Gastroenterol. Nutr. 79(1), 110–118 (2024).

Zdanowicz, K. et al. Thrombospondin-2 as a potential noninvasive biomarker of hepatocyte injury but not liver fibrosis in children with MAFLD: A preliminary study. Clin. Exp. Hepatol. 9(4), 368–374 (2023).

Targher, G., Byrne, C. D. & Tilg, H. MASLD: A systemic metabolic disorder with cardiovascular and malignant complications. Gut 73(4), 691–702 (2024).

European Society for Pediatric Gastroenterology HpaNE, (EASL) EAftSotL, North American Society for Pediatric Gastroenterology Hp, and Nutrition (NASPGHAN), Latin‐American Society for Pediatric Gastroenterology Hp, and Nutrition (LASPGHAN), Asian Pan‐Pacific Society for Pediatric Gastroenterology HpaNA, (PASPGHAN) PASfPGaN et al. Paediatric steatotic liver disease has unique characteristics: A multisociety statement endorsing the new nomenclature. J. Pediatr. Gastroenterol. Nutr. 78(5), pp. 1190–6 (2024).

Liu, C. et al. New-onset age of nonalcoholic fatty liver disease and cancer risk. JAMA Netw. Open 6(9), e2335511 (2023).

Buzzetti, E., Pinzani, M. & Tsochatzis, E. A. The multiple-hit pathogenesis of non-alcoholic fatty liver disease (NAFLD). Metabolism 65(8), 1038–1048 (2016).

Tagi, V. M., Samvelyan, S. & Chiarelli, F. An update of the consensus statement on insulin resistance in children 2010. Front. Endocrinol. 13, 1061524 (2022).

Kopiczko, N. et al. Serum concentration of fatty acids in children with obesity and nonalcoholic fatty liver disease. Nutrition 94, 111541 (2022).

Núñez-Sánchez, M. et al. Lipidomic analysis reveals alterations in hepatic FA profile associated with MASLD stage in patients with obesity. J. Clin. Endocrinol. Metab. 109(7), 1781–1792 (2024).

Ventura, R., Martínez-Ruiz, I. & Hernández-Alvarez, M. I. Phospholipid membrane transport and associated diseases. Biomedicines 10(5), 1201 (2022).

Lauritzen, L., Hansen, H. S., Jørgensen, M. H. & Michaelsen, K. F. The essentiality of long chain n-3 fatty acids in relation to development and function of the brain and retina. Prog. Lipid Res. 40(1–2), 1–94 (2001).

Jacobs, S. et al. Association between erythrocyte membrane fatty acids and biomarkers of dyslipidemia in the EPIC-potsdam study. Eur. J. Clin. Nutr. 68(4), 517–525 (2014).

Koehrer, P. et al. Erythrocyte phospholipid and polyunsaturated fatty acid composition in diabetic retinopathy. PLoS ONE 9(9), e106912 (2014).

Colussi, G., Catena, C., Mos, L. & Sechi, L. A. The metabolic syndrome and the membrane content of polyunsaturated fatty acids in hypertensive patients. Metab. Syndr. Relat. Disord. 13(8), 343–351 (2015).

Jauregibeitia, I. et al. Fatty acid profile of mature red blood cell membranes and dietary intake as a new approach to characterize children with overweight and obesity. Nutrients 12(11), 3446 (2020).

Jauregibeitia, I. et al. Potential of erythrocyte membrane lipid profile as a novel inflammatory biomarker to distinguish metabolically healthy obesity in children. J. Pers. Med. 11(5), 337 (2021).

Jauregibeitia, I. et al. Molecular differences based on erythrocyte fatty acid profile to personalize dietary strategies between adults and children with obesity. Metabolites 11(1), 43 (2021).

Bonafini, S. et al. Individual fatty acids in erythrocyte membranes are associated with several features of the metabolic syndrome in obese children. Eur. J. Nutr. 58(2), 731–742 (2019).

Perona, J. S., González-Jiménez, E., Aguilar-Cordero, M. J., Sureda, A. & Barceló, F. Structural and compositional changes in erythrocyte membrane of obese compared to normal-weight adolescents. J. Membr. Biol. 246(12), 939–947 (2013).

Pang, S. J. et al. The association between the plasma phospholipid profile and insulin resistance: A population-based cross-section study from the China adult chronic disease and nutrition surveillance. Nutrients 16(8), 1205 (2024).

Younsi, M. et al. Erythrocyte membrane phospholipid composition is related to hyperinsulinemia in obese nondiabetic women: Effects of weight loss. Metabolism 51(10), 1261–1268 (2002).

Clore, J. N. et al. Changes in phosphatidylcholine fatty acid composition are associated with altered skeletal muscle insulin responsiveness in normal man. Metabolism 49(2), 232–238 (2000).

Lee, S. et al. Skeletal muscle phosphatidylcholine and phosphatidylethanolamine respond to exercise and influence insulin sensitivity in men. Sci. Rep. 8(1), 6531 (2018).

Yu, Q. et al. High n-3 fatty acids counteract hyperglycemia-induced insulin resistance in fat-1 mice via pre-adipocyte NLRP3 inflammasome inhibition. Food Funct. 12(1), 230–240 (2021).

Mariamenatu, A. H. & Abdu, E. M. Overconsumption of omega-6 polyunsaturated fatty acids (PUFAs) versus deficiency of omega-3 PUFAs in modern-day diets: The disturbing factor for their “balanced antagonistic metabolic functions” in the human body. J. Lipids. 2021, 8848161 (2021).

Notarnicola, M. et al. Significant decrease of saturation index in erythrocytes membrane from subjects with non-alcoholic fatty liver disease (NAFLD). Lipids Health Dis. 16(1), 160 (2017).

Maciejewska, D. et al. Changes of the fatty acid profile in erythrocyte membranes of patients following 6-month dietary intervention aimed at the regression of nonalcoholic fatty liver disease (NAFLD). Can. J. Gastroenterol. Hepatol. 2018, 5856201 (2018).

Rinella, M. E. et al. A multisociety Delphi consensus statement on new fatty liver disease nomenclature. Hepatology 78(6), 1966–1986 (2023).

Muniyappa, R., Lee, S., Chen, H. & Quon, M. J. Current approaches for assessing insulin sensitivity and resistance in vivo: Advantages, limitations, and appropriate usage. Am. J. Physiol. Endocrinol. Metab. 294(1), E15-26 (2008).

Kostovski, M., Simeonovski, V., Mironska, K., Tasic, V. & Gucev, Z. Metabolic profiles in obese children and adolescents with insulin resistance. Open Access Maced. J. Med. Sci. 6(3), 511–518 (2018).

Tahapary, D. L. et al. Challenges in the diagnosis of insulin resistance: Focusing on the role of HOMA-IR and Tryglyceride/glucose index. Diabetes Metab. Syndr. 16(8), 102581 (2022).

Funding

This study was financially supported by grants from the Medical University of Bialystok, Poland., Grant No: B.SUB.25.427, Grant No: B.SUB.25.427, Grant No: B.SUB.25.427, Grant No: B.SUB.25.427, Grant No: B.SUB.25.427, Grant No: B.SUB.25.427, Grant No: B.SUB.25.427, Grant No: B.SUB.25.427, Grant No: B.SUB.25.427

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

Dr K.Z. had primary responsiblity for patient screening, enrollment, outcome assessment, preliminary data analysis and writing the manuscript. Dr E. H-S. participated in the analytical framework for the study and outcome assessment, preliminary data analysis and writing the manuscript. Drs K. S., M. W., A. B.-C., M. F.-J. and J. J. had primary responsiblity for patient screening. Prof. D. M. L. and Prof. A. C. had primary responsiblity for protocol development, supervised the design and execution of the study and contributed to the writing of the manuscript.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher’s note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Supplementary Information

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if you modified the licensed material. You do not have permission under this licence to share adapted material derived from this article or parts of it. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Zdanowicz, K., Harasim-Symbor, E., Sienkiewicz, K. et al. Erythrocyte membrane lipid profile in children and adolescents with metabolic dysfunction-associated steatotic liver disease and insulin resistance: a preliminary study. Sci Rep 15, 31511 (2025). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-17430-2

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-17430-2