Abstract

Accurate road extraction from remote sensing images is crucial for autonomous driving, urban planning, and route planning. However, existing methods struggle to address the challenges of scale variation, occlusion, and blurred boundaries. To tackle these challenges, this paper proposes a heterogeneous dual-decoder network (HDDNet), which aims to simultaneously solve the multiple problems in remote sensing road extraction by designing two decoders with complementary functions. Specifically, the main decoder incorporates the Dynamic Snake Grouping Dilation (DSGD) module, which combines road morphological features with a grouped multi-scale receptive field to enhance the capture of narrow and multi-scale road features. The auxiliary decoder integrates the Multi-directional Connectivity and Boundary Enhancement (MCBE) module, which jointly optimizes road connectivity and boundary refinement by leveraging directional consistency between the road body and edges. Finally, the Dual Attention Feature Fusion (DAFF) module is introduced to interactively learn and fuse the output features of the main decoder and the auxiliary decoder in both spatial and channel dimensions, which improves the accuracy and robustness of feature representations. We conducted systematic experiments on three representative public datasets: DeepGlobe, Ottawa, and CHN6-CUG. The results demonstrate that the proposed method significantly outperforms current mainstream approaches in the road extraction task, achieving Intersection over Union (IoU) scores of 71.36%, 91.85%, and 67.27%, respectively, which strongly validates the performance and robustness of HDDNet across diverse road scenarios.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Remote sensing imagery features wide coverage and high spatial resolution1, providing rich ground information for various tasks such as road extraction2, salient object detection (SOD)3, and change detection4. Road segmentation5 and object detection techniques6,7 serve as key supports for downstream applications such as smart city development, vehicle navigation, and autonomous driving. Consequently, accurately extracting road information from high-resolution remote sensing images has become a research hotspot in recent years8,9.

Traditional road extraction methods include clustering10, Support Vector Machines (SVM)11, and Conditional Random Fields (CRF)12. These approaches often require substantial manual intervention and suffer from limited accuracy, which hinders their application to large-scale road extraction in complex remote sensing scenes.

With the advancement of artificial intelligence, deep learning-based semantic segmentation methods have considerably advanced remote sensing road extraction technology. For example, Krizhevsky et al.13 proposed a Convolutional Neural Network (CNN) model composed of convolutional layers, max-pooling layers, and fully connected layers. Ronneberger et al.14 proposed a symmetric network architecture called U-net, which effectively captures the contextual information and detailed features of images by integrating shallow and deep features through skip connections. Following this, several specialized methods for road segmentation have emerged. Zhou et al.15 developed D-LinkNet, which employs cascaded dilated convolution modules to enlarge receptive fields and extract rich contextual information. Y. Wang’s16 NL-LinkNet incorporates a non-local operation mechanism to capture long-range pixel dependencies. Li et al.17 improved road network connectivity and boundary smoothness by combining multi-scale road information through two cascaded attention mechanisms. However, most of the methods use a single encoder-decoder architecture, resulting in these models still facing significant limitations in dealing with the road extraction task in complex scenes, making it difficult to fully capture the diverse features in the image.

To acquire richer features, homogeneous dual-decoder models have been proposed. DDU-Net18 enhances the performance of small road extraction by incorporating an auxiliary decoder to preserve detailed information. Wang et al.19 proposed an end-to-end dual-decoder U-Net model to effectively address occlusion challenges in road detection. However, multiple challenges often coexist in remote sensing road extraction. As shown in Fig. 1: The first image shows that roads are complex and diverse in type, with uneven widths, and usually present a multi-scale tubular structure. The second image shows that some road areas are similar to their surroundings, resulting in blurred road edge features and making it difficult to achieve accurate boundary localization. The third image shows that occlusion by trees and buildings leads to fragmentation of the extracted roads and low connectivity. Due to the tendency of the same decoder to learn similar features, it is difficult to cope with the above multiple problems at the same time by simply adopting the isomorphic dual-decoder architecture, and the model performance improvement is limited.

To address these challenges, this study proposes a heterogeneous dual-decoder-based road extraction network (HDDNet) for remote sensing images. The core idea of HDDNet is to reconstruct diverse road features using heterogeneous decoders with complementary functions. Specifically, this paper introduces the Dynamic Snake Group Dilation (DSGD) module into the main decoder. This module combines Dynamic Snake Convolution (DSConv)20 with grouped multi-scale dilated convolutions: DSConv is first employed to capture the tubular prior structure of roads, followed by multi-scale dilation operations to extract rich semantic information, thereby enhancing adaptability to varying road scales. Meanwhile, the Multi-directional Connectivity and Boundary Enhancement (MCBE) module is integrated into the auxiliary decoder. This module models long-range spatial dependencies between pixels using multi-directional strip convolutions21 to enhance the connectivity of roads in occluded regions. In addition, edge detection operators aligned with the strip directions are introduced to further strengthen boundary features and improve the accuracy of road boundary localization. Finally, a Dual Attention Feature Fusion (DAFF) module is introduced to deeply fuse the output features of the two decoders across both spatial and channel dimensions, effectively mitigating interference between multi-source features and fully exploiting their complementary potential. The main contributions of this paper are summarized as follows:

-

1.

A novel heterogeneous dual-decoder network, HDDNet, is proposed, which effectively addresses the multiple challenges of road extraction in complex remote sensing scenarios by leveraging the functional complementarity between the main and auxiliary decoders.

-

2.

The DSGD module is designed by combining DSConv with grouped multi-scale dilated convolutions. It accurately captures local texture and multi-scale structural features of roads, enhancing the perception of diverse road forms.

-

3.

The MCBE module is proposed by combining multi-directional strip convolutions with direction-consistent edge detectors, significantly improving road connectivity in occluded regions and enhancing the clarity of weak road boundaries.

Related works

Road segmentation methods

In recent years, a variety of approaches have been introduced to enhance the accuracy of road extraction from remote sensing imagery22,23,24,25,26,27,28,29,30,31,32,33. Gao et al.34 proposed a novel end-to-end multi-feature pyramid network (MFPN) based on PSPNet, which effectively integrates low-level spatial cues with high-level semantic information to perform multi-scale road extraction. To achieve a balance between model complexity and computational efficiency, Li et al.35 designed B-D-LinknetPlus, an improved architecture built on D-Linknet. J. Mei et al.36 introduced the CoANet, utilizing strip convolutions to capture extended contextual relations and enhancing road connectivity by modeling pixel adjacency. Dai et al.37 proposed an enhanced deformable attention module designed to capture extensive contextual relationships specific to road pixels. Deng et al.38 integrated a multi-scale adaptive module (MSAM) within the decoder, enabling the aggregation of rich contextual information across scales to better reconstruct road features. Yang et al.39 developed OARENet, an occlusion-aware decoder explicitly designed to model texture details in heavily occluded road segments, thereby reducing occlusion-related issues in road extraction. In another work, Yang et al.40 proposed a road extraction network based on global-local context awareness combined with cross-scale feature interactions, mining detailed contextual cues from deep feature maps to improve road structure prediction. Gong et al.41 presented Hard-Swish Squeeze-Excitation RoadNet, which aims to boost road extraction performance in complex regions of remote sensing images. Zhang et al.42 proposed a dual-stream collaborative network that combines local detail modeling with global context awareness. By incorporating Swin-Transformer and graph attention modules, the method effectively enhances the accuracy of remote sensing road recognition. Liu et al.43 proposed CGCNet, which achieves efficient remote sensing road extraction by introducing a compact global context block (CGCB), balancing accuracy and computational efficiency.

Although the aforementioned methods have made some progress, extracting roads from remote sensing images often presents multiple challenges simultaneously, and existing approaches struggle to address these issues adequately. Therefore, this paper proposes HDDNet, which adopts a heterogeneous dual-decoder architecture optimized for different challenges: the main decoder focuses on capturing multi-scale road features, while the auxiliary decoder aims to reduce occlusion interference and refine road boundaries. This design significantly enhances the model’s robustness and accuracy in diverse and complex scenarios.

Dynamic snake convolution for road segmentation

Tubular structures are a common characteristic of most roads; therefore, accurately perceiving local tubular shapes is crucial for improving extraction accuracy. Conventional convolutions are constrained by fixed local receptive fields and inflexible sampling positions, limiting their ability to capture complex global features and adapt to transformations. Deformable convolution44 introduces dynamic offsets that allow flexible adjustment of kernel sampling positions, enhancing the model’s capability to capture irregular shapes and complex structures. However, deformable convolution permits networks to learn unconstrained geometric variations, leading to unstable perceptual regions when processing small tubular structures. As shown in Fig. 2, dynamic snake convolution (DSConv)20 can dynamically adjust the convolution kernel’s shape, enabling it to focus on narrow and curved structures while accurately capturing irregular tubular features. This dynamic offset mechanism breaks through the fixed geometric constraints of traditional convolutions, allowing networks to autonomously adjust receptive field distributions according to road morphological characteristics, thereby enhancing representation capabilities for slender tubular structures.

Subsequently, several road extraction methods based on DSConv have demonstrated its powerful capabilities. Li et al.45 proposed DEGANet, which integrated DSConv blocks into ResNet to emphasize tubular elongated structures, thereby enhancing road feature extraction and focusing on capturing more road details. Yu et al.46 introduced DSConv as fundamental modules for low-level feature extraction in networks, aiming to capture roads’ complex shapes. Li et al.47 employed DSConv to process multimodal road data, adaptively focusing on slender and winding local structures to accurately capture tubular road features. Liu et al.48 combined the advantages of DSConv and Fourier convolution, and proposed a salient-aware dynamic convolution (SD-Conv) layer to extract faint road targets and global structures. Ma et al.49 designed a multi-scale snake-shaped convolutional decoder (MSSD) to help the model better reconstruct roads.

Although DSConv performs well in capturing local tubular road structures, it still faces limitations when dealing with complex and variable multi-scale road features. Introducing multi-scale DSConv can alleviate this issue to some extent, but it significantly increases computational overhead. To address this, this paper proposes the DSGD module, which combines DSConv with grouped dilated convolutions to effectively enhance multi-scale feature representation while avoiding a substantial increase in computational complexity.

Method

Network architecture

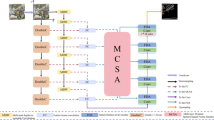

The architecture of the HDDNet framework proposed in this paper is shown in Fig. 3, and its core design adopts a two-branch heterogeneous decoder architecture to cope with the parsing challenges of complex road scenes. In the encoder part, we choose the pre-trained ResNet3450 as the backbone network, where ei (\(i = 0, 1, 2, 3, 4\)) denotes the multiscale feature maps outputted from layer i of the encoder. In order to overcome the limitations of traditional network architecture representation in complex scenarios, this framework innovatively constructs two heterogeneous decoders with complementary feature processing capabilities: The main decoder branch takes the high-level feature e4, which contains rich semantic information, as its input. It constructs local tubular structures and multi-scale feature representations through the DSGD module, significantly enhancing the network’s ability to capture variations in road topology. This design is particularly effective for handling scenarios with irregular road shapes and large scale variations. The auxiliary decoder branch focuses on the deep mining of the mid-level feature e3, which has the advantage of balancing semantic abstraction and spatial details. This branch introduces the MCBE module in the decoder, which can effectively enhance road connectivity in the case of occlusion, and utilize multi-directional edge operators to improve the boundary localization accuracy. In particular, we fuse the encoder shallow features with the corresponding features of the two decoders through cross-layer skip connections, which effectively supplements the low-level spatial detail information. Finally, the feature maps of the two decoder branches are interactively fused in the spatial and channel domains via the DAFF module, which ensures the synergistic optimization of the heterogeneous dual-decoder features and thus thereby improves the completeness and boundary accuracy of road extraction.

Dynamic snake grouping dilation module

Remote sensing images have significant scene diversity, and road targets have significant multi-scale distribution characteristics and often present complex geometric topology. Traditional convolution kernels have fixed shapes, which are difficult to adapt to the complex geometries of roads. Although dynamic snake convolution (DSConv)20 has made certain progress in local road perception by introducing a deformable convolution mechanism, it inherently lacks explicit modeling capability for multi-scale features, resulting in limited adaptability when dealing with road structures with drastic scale variations. Existing methods attempt to address this issue by introducing global feature extraction modules or employing multi-scale DSConv. However, incorporating global features alone fails to effectively tackle the multi-scale challenge, while simply stacking multi-scale DSConv significantly increases computational cost. To address these problems, we propose Dynamic Snake Grouping Dilation (DSGD) module, which is an innovative “grouping-inflation” synergetic architecture, as shown in Fig. 4. The DSGD module first employs horizontal and vertical DSConvs to extract fine-grained road shape and structural information. It then groups and cross-concatenates the extracted features with the original ones to enhance feature representation while mitigating information loss. Next, convolution operations with different dilation rates are applied to the cross-spliced features, which not only effectively control computational overhead but also enrich the multi-scale representation of features, thereby further improving the model’s ability to understand and model complex multi-scale road scenes.

Specifically, we denote the input feature mapping of DSGD as \(D \in \mathbb {R}^{H \times W \times C}\), where H, W, and C correspond to its height, width, and channel dimensions, respectively. As shown in Fig. 4, we first capture the road topology features in the horizontal and vertical directions through dynamic snake convolutions in the x and y axes, respectively, and obtains \(D_x \in \mathbb {R}^{H \times W \times C}\) and \(D_y \in \mathbb {R}^{H \times W \times C}\). Then, \(D_x\), \(D_y\) and the original feature D are partitioned into four groups along the channel dimension, denoted as \(Dx_i, Dy_i,D_i, \in \mathbb {R}^{H \times W \times C/4}\) (\(i = 1, 2, 3, 4\)). The segmented features are spliced separately to construct multi-source fusion feature groups \(G_i\in \mathbb {R}^{H \times W \times 3C/4}\) (\(i = 1, 2, 3, 4\)), each containing three different features, which maintains the flexibility of the DSConv while preserving the underlying details. The computational formula is as follows:

where \(\hbox {DSC}_x\) and \(\hbox {DSC}_y\) denote the DSConv denoting the x-axis and y-axis directions, respectively, Split denotes channel splitting, and Concat denotes channel merging. Subsequently, the spliced multi-source fusion feature set is fed into multiple dilated convolutions with dilation rates of 1, 3, 5, and 7, respectively, to perceive the information at different scales, to adapt to drastic changes in road shapes and scales in remotely sensed images. After the dilation convolution process, the feature \(Gd_i\in \mathbb {R}^{H \times W \times 3C/4}\) (\(i = 1, 2, 3, 4\)) is obtained. Next, the four sets of features processed by the dilated convolutions are concatenated along the channel dimension, followed by a \(1 \times 1\) convolution to enable cross-scale fusion and interaction, while simultaneously adjusting the number of channels to meet the subsequent requirements. Finally, the output features \(D_{out}\) are obtained after the batch normalization (BN) layer and Relu activation function. The specific calculation formula is as follows:

where \(\hbox {DConv}_{d_i}\) is used to denote the dilation convolution operation with a dilation rate of \(d_i\) and \(\hbox {Conv}_{1 \times 1}\) denotes a \(1 \times 1\) convolution.

Multi-directional connectivity and boundary enhancement module

In remote sensing road segmentation tasks, some roads share similar spectral characteristics with the surrounding environment, leading to weakened road features and making it difficult to distinguish boundary regions. Meanwhile, local occlusion caused by building shadows and vegetation seriously damages the integrity and connectivity of roads. The traditional Sobel51 edge detection operator prone to introduce pseudo edges in complex backgrounds, and these noisy edges will seriously affect the judgment of the subsequent segmentation algorithm on the real road boundary. As shown in Fig. 5, through the in-depth analysis of the road morphology characteristics, we find that there is a significant spatial correlation between the direction distribution of the road boundary and the direction of the road body. Even in the curved road section, as shown in the third image of Fig. 5, the local boundary direction still strictly remains consistent with the direction of the road body.

Based on this phenomenon, we propose the Multi-directional Connectivity and Boundary Enhancement (MCBE) module, as shown in Fig. 6. The MCBE module effectively suppresses noise interference during the boundary detection process by introducing directional consistency constraints, thereby improving the accuracy of boundary localization. Its core innovations lie in two aspects: (1) extracting road features using multi-directional strip convolution21, which leverages its long-range information perception capability to enhance the connectivity of occluded road segments while significantly strengthening the boundary response of weak road features, laying a foundation for more accurate boundary localization; (2) designing a multi-directional edge detection mechanism that spatially aligns the boundary detection process with the road geometric features by applying the Sobel operator oriented consistently with the strip convolution directions, thus achieving precise localization of true road edges. Therefore, through this two-stage synergistic mechanism, the MCBE module not only significantly improves the integrity of the road under occlusion conditions but also extracts accurate road edge information.

Specifically, we denote the input feature map as \(X \in \mathbb {R}^{H \times W \times C}\), where H, W, and C correspond to its height, width, and channel dimensions, respectively. We first apply strip convolutions along the horizontal, vertical, and two diagonal directions, each with the number of channels reduced to one quarter of the original. After processing with multi-directional strip convolutions, four feature maps \(S_i \in \mathbb {R}^{H \times W \times C/4}\) (\(i=1,2,3,4\)) are output. The formula is as follows:

where \(\text {Conv1D}_{i}\) (\(i=1,2,3,4\)) denotes one-dimensional strip convolution in different directions, respectively. Next, Sobel operators are applied along the same directions as the strip convolutions to effectively reduce the interference of false edges in each directional branch, thereby extracting more accurate multi-directional edge features. Subsequently, a nonlinear edge response mechanism is constructed by combining batch normalization (BN) and the activation function (ReLU) to enhance feature representation. Finally, a \(3 \times 3\) convolution is used to further suppress noise and refine the road boundary features. The detailed process is as follows:

where Sobel_X, Sobel_Y, Sobel_L, and Sobel_R, denote the Sobel operators in different directions, as shown in Fig. 6. \(\hbox {conv}_{3 \times 3}\) denotes the \(3 \times 3\) convolution operation, and \(B_i\) and \(E_i\) (\(i = 1, 2, 3, 4\)) represent the intermediate features obtained after multi-directional Sobel operator processing and \(3 \times 3\) convolution processing, respectively. Then, the extracted boundary features are summed with the corresponding original road features via residual connections to generate a multi-directional road representation that incorporates rich edge information. Next, the features from each sub-branch are concatenated along the channel dimension, followed by a \(1 \times 1\) convolution to achieve deep fusion and channel adjustment. Finally, the final output feature \(X_{out}\) is obtained after a batch normalization (BN) layer and ReLU activation function. The computational process is as follows:

where Concat denotes the feature splicing operation, and \(\hbox {Conv}_{1 \times 1}\) denotes a \(1 \times 1\) convolution.

Dual attention feature fusion module

The remote sensing road extraction model proposed in this paper adopts a heterogeneous dual-decoder architecture: the main decoder focuses on multi-scale road feature extraction in complex environments, while the auxiliary decoder is specialized in enhancing road connectivity and capturing boundary details. Traditional feature fusion methods, such as simple summation or concatenation, often fail to fully integrate the output features of heterogeneous decoders, leading to incomplete information extraction or feature loss. To address this issue, researchers have introduced attention mechanisms52,53,54, which dynamically assign weights across channels or spatial locations to highlight key information and enhance feature fusion. Inspired by this, we design a Dual Attention Feature Fusion (DAFF) module. As shown in Fig. 7, this module effectively realizes the complementary fusion of heterogeneous features through the dual weighting mechanism of spatial attention and channel attention, which suppresses redundant noise and significantly improves the network’s ability to focus on the road region.

Specifically, the two input feature maps are denoted as \(F1 \in \mathbb {R}^{H \times W \times C}\) and \(F2 \in \mathbb {R}^{H \times W \times C}\), where H, W, and C correspond to its height, width, and channel dimensions, respectively. First, F1 and F2 are summed and channel compression is performed using a \(1 \times 1\) convolution, followed by generating a spatial weight map \(W_s \in \mathbb {R}^{H \times W \times 1}\) via a Sigmoid activation function. Next, this spatial weight map is multiplied with the original features to obtain the spatially enhanced features \(F1_s\) and \(F2_s\), respectively. The computational formula is as follows:

The two spatially enhanced feature maps are summed to produce the composite feature map \(F_s\), which is followed by subsequent parallel execution of Global Average Pooling (GAP) and Global Maximum Pooling (GMP) operations on \(F_s\), respectively. The pooling results are summed and fed into a multi-layer perceptron (MLP) network, followed by the Sigmoid activation function is used to generate the channel attention weights \(W_c \in \mathbb {R}^{1 \times 1 \times C}\). Next, the spatial enhancement features \(F1_s\) and \(F2_s\) are multiplied with the channel weighting coefficients \(W_c\), respectively, to obtain the dual spatial and channel enhancement features \(F1_{sc}\) and \(F2_{sc}\). Finally, the original features are fused with the channel-enhanced features through residual connections to obtain the final fusion result \(F_{out}\). The computational flow is as follows:

where GAP denotes Global Average Pooling, GMP denotes Global Maximum Pooling, and MLP includes a channel-reduced \(1 \times 1\) convolution, a Relu activation function, and a channel-restored \(1 \times 1\) convolution.

Loss function

Some studies define remote-sensing image road extraction as a binary classification task, so only two categories of road and non-road are considered. In this article, we will jointly use the Binary Cross Entropy loss (\({L_\mathrm {{BCE}}}\)) and the Dice Coefficient loss (\({L_\mathrm {{dice}}}\)), which is generally used to measure the similarity of two sets \(Y_\textrm{pred}\) and the ground truth \(Y_\textrm{true}\) . \(Y_\textrm{pred}\) is the predicted value and \(Y_\textrm{true}\) is the true label in the range [0, 1]. The following definition of loss applies to this paper:

\(L_\mathrm {{BCE}}\) and \(L_\mathrm {{dice}}\) are respectively defined as:

where \(y_i \in [0,1]\) is the binary label of the i-th pixel, N is the total number of pixels, and \(\hat{y_{i}} \in (0,1)\) is the predicted probability for the i-th pixel. If predicted \(\hat{y_{i} }\) tend to 1, then the loss of value should converge to zero. Conversely, if the predicted value \(\hat{y_{i} }\) approaches 0, the loss becomes large.

Experiment

Datasets

We selected three widely used public datasets for evaluation and validation experiments. The details of each dataset are as follows.

DeepGlobe: The DeepGlobe road extraction dataset includes images from Thailand, India, and Indonesia, with pixel-level annotations distinguishing road and background classes55. The images have a spatial resolution of 50 cm/pixel and a size of \(1024 \times 1024\) pixels. We used the \(1024 \times 1024\) pixel images as inputs to the network to preserve detailed spatial information about roads. Since the DeepGlobe dataset lacks road labels for the validation and test sets, following36, all 6226 labeled samples were randomly split into 4696 training samples and 1530 test samples.

Ottawa: This dataset provides pixel-level annotated remote sensing images of size \(512 \times 512\) pixels, with a spatial resolution of 21 cm/pixel, and contains numerous buildings and occlusions56. It contains 824 images in total, among which 708 were used for training and 116 for testing. The dataset covers several typical urban areas of Ottawa, collectively spanning approximately 8 \(\mathrm {km^{2}}\) across 20 regions.

CHN6-CUG: The CHN6-CUG dataset57 comprises 4511 labeled images of size \(512 \times 512\) pixels, with a resolution of 50 cm/pixel. It is divided into 3608 training images and 903 test images for evaluation. The dataset primarily covers six different Chinese cities and includes various types of urban roads and overpasses.

Training settings

The experiments were carried out in a Python 3.8 environment utilizing the PyTorch deep learning framework. Training and evaluation of the model took place on NVIDIA RTX 3090 GPUs, each featuring 24 GB of VRAM. To improve the model’s ability to generalize and reduce overfitting, we implemented a comprehensive data augmentation scheme that includes random flips along horizontal, vertical, and diagonal axes. The Adam optimizer was selected for training, initialized with a learning rate of \(2 \times 10^{-4}\). We employed a progressive learning rate decay strategy, decreasing the rate by a factor of 5 at 50%, 85%, and 95% of the total training epochs. The DeepGlobe dataset was trained for 200 epochs, while the Ottawa and CHN6-CUG datasets underwent 100 epochs each. Ultimately, the model’s output probability maps were thresholded at 0.5 to generate the final binary road segmentation masks.

Evaluation metrics

To comprehensively evaluate the model’s performance, we selected multiple evaluation metrics, including Intersection over Union (IoU), Precision, Recall, F1 Score, and mean IoU (mIoU). Precision and Recall are mutually constrained and exhibit a trade-off; in complex tasks, it is uncommon for both to be simultaneously high. Based on this, the F1 Score, as the harmonic mean of Precision and Recall, becomes a crucial metric for assessing overall model performance. IoU calculates the ratio of the intersection over the union of the predicted road pixels and the ground truth pixels, intuitively reflecting the degree of overlap between the prediction and the actual annotation, and thus is widely used in road segmentation tasks. Overall, the F1 Score and IoU are regarded as the most representative evaluation criteria. The formal definitions of these metrics are provided below:

where TP, FP, TN, and FN represent the numbers of pixel-wise true positive, false positive, true negative, and false negative, respectively.

comparison with other road extraction models

To verify the performance of HDDNet, we compared it with the most popular road extraction methods, including D-LinkNet15, NL-LinkNet16, CoANet36, DBRANet24, DDU-Net18, DSCNet20, CFRNet30, OARENet39, Swin-GAT42, CGCNet43. To ensure fairness, all models are trained and tested on the same dataset under identical experimental conditions. In the end, our proposed model achieves the best results in IoU and F1 score on all datasets.

The DeepGlobe dataset features numerous rural and small-town roads characterized by significant variability, with many road regions closely resembling the surrounding background. Table 1 summarizes the quantitative performance on this dataset. Our approach attains an IoU score of 71.39%, surpassing the runner-up by 1.27%. While our method exhibits a slightly lower precision compared to CoANet, it achieves superior results in the more holistic metric of F1 score. These findings indicate that the proposed method successfully captures road features at multiple scales and adapts well to diverse road scenarios.

The Ottawa dataset is a commonly used urban road dataset, and the road types are mainly urban main roads, including a large number of trees, crosswalks, parking lots and other interference scenes. As can be seen from Table 2, our proposed HDDNet achieves the best results in all five performance metrics on the Ottawa dataset, with IoU of 91.85% and F1 of 95.75%. Compared with the second-ranked Swin-GAT, HDDNet improves IoU by 0.81% and F1 by 0.44%. The experimental results show that HDDNet is able to effectively suppress feature interference in non-road areas, and exhibits stronger feature selectivity during challenging scenarios such as complex textures.

The CHN6-CUG dataset comprises road imagery collected from six diverse cities, showcasing complex environments, a variety of road categories, and challenges such as occlusions and shadow interference. As illustrated in Table 3, HDDNet achieves the highest scores (67.27% IoU, 80.44% F1). When compared with the next best performing approach(OARENet), HDDNet shows improvements of 1.09% in IoU and 0.79% in F1. The quantitative comparisons presented confirm that HDDNet effectively adapts to road conditions across multiple regions, demonstrating strong robustness and generalization across different scenarios, and outperforming other state-of-the-art models in overall performance.

To provide a more intuitive demonstration of the model’s performance, we selected several representative road extraction scenarios and presented the visual extraction results of different models, as shown in Fig. 8. Among them, the first two sets of images are from DeepGlobe dataset, the middle two sets of images are from Ottawa dataset, and the last two sets of images are from CHN6-CUG dataset. For easier observation, we use red to indicate road segments that were false negatives (FN), green to represent false positives (FP), and blue boxes to highlight regions with significant performance gaps. From the results of each algorithm in the figure, our proposed algorithm performs the best in terms of overall visualization and the extraction results are closest to the ground truth. Specifically, (1) the first row of the figure is a rural road scene where the road is very similar to the environmental background, and our proposed algorithm successfully extracts a relatively complete road, while the roads extracted by the other methods are all broken to different degrees; (2) the second row of the figure is a densely populated residential area, with a large number of intersections, trees, and houses interfering. Facing the almost completely obscured path (boxed area), only HDDNet successfully recognizes and correctly extracts the road; (3) In the low-complexity scene in the third row of the figure, all mainstream models achieve more complete extraction, but our method performs better in terms of road connectivity and boundary clarity; (4) The fourth row depicts a scene with interference from parking lots, lane markings, and buildings. Only HDDNet and Swin-GAT are able to extract structurally complete roads, and our method achieves smoother boundaries; (5) The fifth row illustrates a complex urban road network. Our method, Swin-GAT, and CoANet all manage to extract relatively complete main roads. However, Swin-GAT almost completely overlooks the smaller roads, while CoANet exhibits a large number of false positive regions (marked in green); (6) In the sixth row of the narrow and curved path scenario, only HDDNet clearly extracts the road shape and preserves the overall topology.

Combining all the results, it can be seen that the model proposed in this paper provides better pixel-level segmentation and greatly reduces the problem of fragmentation of road extraction results compared to other models. The strong performance is demonstrated in a variety of challenges such as multi-scale of roads, occlusion interference, and inconspicuous texture.

Module ablation analysis

To validate the effectiveness of our proposed DSGD, MCBE, and DAFF modules, we conducted a series of ablation experiments. In these experiments, we first removed these three modules from HDDNet and then incrementally incorporated them to assess their individual contributions. Comparative studies were performed using the DeepGlobe, Ottawa and CHN6-CUG datasets. For feature fusion in the dual-decoder, we used three different approaches: Add (directly summing the output features), Concat (merging the features along the channel dimension followed by channel reduction using a \(1 \times 1\) convolution), and DAFF module.

The results of the ablation experiments of the modules are shown in Tables 4, 5 and 6. When the DSGD module is introduced alone, thanks to its multi-scale feature extraction capability, the feature extraction ability of the network for complex road structures is significantly enhanced, prompting the improvement of all the indexes.The MCBE module, through the multi-directional road connectivity enhancement and boundary enhancement mechanisms, makes the recall rate significantly higher while maintaining high precision, effectively alleviating the road breakage problem. When the DSGD and MCBE modules are jointly introduced, the heterogeneous dual-decoder architecture fully leverages their synergy, leading to a significant improvement in model performance. It is worth noting that although the introduction of the DAFF module leads to a slight decrease in accuracy and recall in some datasets, its dual-attention fusion mechanism effectively optimizes the balance between the two, thereby promoting the improvement of overall performance metrics. Compared with other feature fusion methods, the Add method fails to fully exploit the complementary advantages of different features; while the Concat method performs the most poorly due to the fact that splicing and then channel dimensionality reduction lead to a large amount of information loss. Taken together, the DAFF module achieves the best fusion performance and overall performance improvement while maintaining a balance between accuracy and recall.

Model visualization results under different model configurations. White: true positive, red: false negative, green: false positive. Images in rows 1,2 are from the DeepGlobe dataset, images in rows 3,4 are from the Ottawa dataset, and images in rows 5,6 are from the CHN6-CUG dataset. In the figure (a): baseline+Add (b): baseline+DSGD+Add (c): baseline+MCBE+Add (d): baseline+DSGD+MCBE+Add (e): baseline+DSGD+MCBE+Concat (f): HDDNet.

The visual results of the ablation experiment are shown in Fig. 9. The yellow boxes in the figure indicate a variety of complex road types and distractions similar to roads. The blue boxes in the figure indicate roads that are obscured by obstacles. As shown in the figure, in the baseline results (column (a)), many non-road areas are mistakenly identified as roads. The extracted road boundaries are rough, and many roads with similar appearance to the background are not correctly recognized. Additionally, in occluded regions, the extracted roads appear fragmented. The effect of adding the DSGD module is shown in column (b), where the unrecognized area (red area) and misrecognized area (green area) of the roads in the image are significantly reduced, especially the yellow boxed portion is significantly improved, and various narrow paths are also extracted. This proves that the DSGD module has strong modeling and recognition capabilities for multi-scale road information in various complex scenes. The results after adding the MCBE module are shown in column (c). The boundaries of the roads become clearer and more complete, and the connectivity of the occluded road areas highlighted in the blue box is also improved. This indicates that the MCBE module can effectively reduce the occlusion interference and accurately locate the road boundary. Notably, when both modules are simultaneously integrated into the network (column (d) in the figure), the accuracy of road extraction is significantly improved across the board. This improvement stems from the complementary nature of the features extracted by the DSGD and MCBE modules. The heterogeneous dual-decoder design of HDDNet further facilitates the effective integration of their respective advantages. Finally, the visualization results in columns (d), (e) and (f) of the figure are compared. Compared with traditional feature addition (Add) and channel concatenation (Concat) methods, the DAFF module effectively integrates key information and enhances the interactive fusion capability of heterogeneous decoder outputs, thereby extracting finer road details and boundaries.

Ablation study and comparative analysis of the DSGD module

To comprehensively validate the effectiveness of the proposed Dynamic Snake Grouped Dilated (DSGD) module, we conduct experiments in three aspects: (1) a quantitative comparison with representative methods based on Dynamic Snake Convolution (DSConv); (2) an ablation study on different dilation rate configurations within the DSGD module; and (3) an analysis of computational complexity (FLOPs) and parameter count (Params) using 512\(\times\)512 input images.

We select three representative DSConv-based methods for comparison: the basic DSConv structure20; FD-Conv48, which introduces lightweight DSConv and incorporates frequency-domain convolution to enhance global structural perception; and MSSD49, which employs multi-scale DSConv kernels to enlarge the receptive field. To investigate the impact of dilation settings, we implement three variants of DSGD with different dilation configurations: (d = 1, 2, 3, 4), (d = 1, 3, 5, 7), and (d = 1, 4, 7, 11). All methods are evaluated on three datasets–DeepGlobe, Ottawa, and CHN6-CUG–using Intersection over Union (IoU,%) as the evaluation metric.

As shown in Fig. 10, the DSGD variant with dilation rates (d = 1, 3, 5, 7) achieves the best overall performance across the three datasets, demonstrating strong road structure modeling capability and better cross-scale adaptability. Specifically, DSConv relies solely on a single snake offset, which limits its ability to model complex contextual relationships and results in the lowest performance. FD-Conv expands the receptive field by introducing frequency-domain features, while MSSD employs multi-scale DSConv. Although both methods improve performance to some extent, FD-Conv still suffers from limitations in detail representation and scale adaptability, and the complex design of MSSD leads to a significant increase in computational cost. The configuration with small dilation rates (d = 1, 2, 3, 4) provides a limited receptive field, hindering its ability to capture global road structures, especially in large-scale scenes. In contrast, the large dilation rate configuration (1, 4, 7, 11) achieves relatively better results on the urban road dataset Ottawa, but introduces more background noise in the other two datasets, leading to a slight performance drop.

Table 7 compares the computational complexity and parameter count of different modules. The results show that the proposed DSGD module (28.65 GFLOPs, 22.77 MParams) incurs only a marginally higher cost than the lightweight FD-Conv (27.32 GFLOPs, 22.33 MParams), while being considerably more efficient than MSSD (35.58 GFLOPs, 24.71 MParams). Overall, DSGD attains superior accuracy with relatively low computational overhead, achieving a well-balanced trade-off between performance and efficiency.

Ablation study of the MCBE module

To further evaluate the contribution of each component in the MCBE module to road extraction, we designed a series of ablation experiments, focusing on the effectiveness of directional convolution and the Sobel edge detection mechanism. The MCBE module primarily consists of two key components. First, multi-directional strip convolutions are employed to enhance the connectivity and receptive field of road structures, particularly improving the model’s response to roads in weak-texture or occluded regions. Second, direction-aligned Sobel filters (Sobel_X, Sobel_Y, Sobel_L, Sobel_R) are incorporated to strengthen edge information and guide the model toward more accurate road boundary localization. To assess the individual contributions of each component, three variants were constructed for comparison: MCBE w/o StripConv, which removes all directional strip convolutions while retaining only the edge detection branch; MCBE w/o Sobel, which excludes the Sobel edge detection mechanism and retains only the structural connectivity enhancement branch; and MCBE (Laplacian) replaces the directionally consistent Sobel operator with a non-directional second-order boundary operator, the Laplacian filter58, to evaluate the importance of directional edge guidance.

The experimental results are shown in Fig. 11. The results demonstrate that both key branches of the MCBE module–multi-directional strip convolution and directional Sobel edge detection–play important roles in improving road extraction performance. When strip convolution is removed (MCBE w/o stripconv), the IoU drops to 70.44%, 90.49%, and 65.90% on the DeepGlobe, Ottawa, and CHN6-CUG datasets, respectively, indicating that the lack of structural connectivity enhancement significantly weakens the model’s perception of occluded or weak-edge roads. When the Sobel branch is removed (MCBE w/o Sobel), the IoU also declines noticeably, showing that edge enhancement is crucial for accurate boundary modeling. Moreover, replacing directional Sobel filters with the non-directional Laplacian operator results in slightly better performance than removing the Sobel branch entirely, but still underperforms compared to the original design. This indicates that directional selectivity is critical for perceiving road geometric boundaries. Ultimately, the complete MCBE module achieves the best results across all three datasets, confirming the complementary advantages of multi-directional convolution and direction-aligned edge detection in improving road connectivity under occlusion and enhancing boundary localization accuracy.

Comparative experiments on different decoder configurations

In road extraction tasks, shallow features preserve rich geometric details (such as edges and textures) due to their high spatial resolution, which is crucial for precise road boundary localization. Conversely, deep features achieve high-level semantic abstraction and strong contextual awareness, enabling robust recognition of road bodies and understanding of their global structures. Furthermore, increasing model depth generally benefits semantic segmentation performance, but overly deep layers can cause attenuation of boundary information. To further validate the rationale behind the heterogeneous dual-decoder design–particularly the functional complementarity between the main and auxiliary decoders, as well as the impact of their layer configurations on performance–we conducted two sets of comparative experiments. These experiments examine two perspectives: (1) swapping the structures of the main and auxiliary decoders, and (2) varying the number of layers in the auxiliary decoder. Scheme A: The main decoder is fixed to 4 layers (embedding the DSGD module), while the number of layers in the auxiliary decoder (embedding the MCBE module) is varied. Scheme B: The main decoder is fixed to 4 layers (embedding the MCBE module), while the number of layers in the auxiliary decoder (embedding the DSGD module) is varied. When both decoders have 4 layers, the network architectures of the two schemes are identical. Both groups of experiments were trained and evaluated on the DeepGlobe, Ottawa, and CHN6-CUG datasets, using IoU as the core metric.

The experimental results are illustrated in Fig. 12, where Scheme A is shown in blue and Scheme B in red. Under Scheme A, increasing the auxiliary decoder layers from 1 to 3 results in stable performance improvement, while increasing to 4 layers causes a slight decline on all three datasets. Although increasing the number of layers allows extraction of more semantic information, overly deep structures weaken critical low-level geometric cues and fine boundary information. MCBE leverages rich geometric details (such as edges, textures, and directional cues) from high-resolution shallow encoder features to refine road boundaries and enhance topological connectivity, particularly in broken or weak-boundary regions. Therefore, the 3-layer setting balances preserving necessary details and avoiding the information attenuation caused by excessive depth. Under Scheme B, when the auxiliary decoder has fewer than four layers, the model performance significantly decreases and is consistently lower than Scheme A. DSGD is primarily designed to model the semantic features of road structures while addressing the challenges posed by large-scale variations and complex background interference. This relies on deep, gradual aggregation and contextual integration of multi-level encoder features (from low-level details to high-level semantics). A shallow main decoder cannot sufficiently capture and fuse the necessary global semantic and morphological features, resulting in a substantial decline in the ability to recognize the road body.

The above experiments fully demonstrate that DSGD is better suited for deep semantic modeling tasks, while MCBE is more suitable for assisting shallow boundary and topology optimization tasks. Based on this, the configuration of a 4-layer DSGD main decoder + 3-layer MCBE auxiliary decoder achieves the best performance. This structure fully exploits the main decoder’s ability to model road morphology and scale while utilizing the auxiliary decoder to enhance boundary and connectivity in shallow features, forming an efficient complementary collaboration mechanism that improves overall remote sensing road extraction performance.

Generalization ability verification of the proposed modules on different backbone architectures

To verify the universality and generalization capability of the proposed modules and overall architecture across different backbone networks, we integrated the proposed modules (DSGD, MCBE, and DAFF) into two mainstream remote sensing semantic segmentation networks: the classic U-Net59 and the Transformer-based segmentation framework Swin Transformer (SwinT)60. The corresponding heterogeneous dual-decoder versions were constructed and named HDD-Unet and HDD-SwinT, respectively. Experiments were conducted on three representative remote sensing road extraction datasets (DeepGlobe, Ottawa, and CHN6-CUG), and under the condition of input image resolution set to 512\(\times\)512, we recorded the number of parameters (Params) and floating-point operations (FLOPs) for each model to comprehensively evaluate their performance in terms of both accuracy and computational efficiency.

As shown in Table 8, the quantitative results demonstrate that integrating our modules and architecture into different backbone networks consistently leads to significant performance improvements. Taking HDD-Unet as an example, it achieves a 5.30% IoU increase over the original U-Net on CHN6-CUG, and gains of 3.23% and 5.29% on DeepGlobe and Ottawa, respectively. HDD-SwinT also performs remarkably well, with improvements of 3.47%, 3.26%, and 2.12% on DeepGlobe, Ottawa, and CHN6-CUG, respectively. These results clearly indicate that the proposed modules are not only effective within the specifically designed HDDNet architecture but also easily transferable to other mainstream models, showing strong reusability and cross-architecture adaptability. Although the introduction of the modules slightly increases the FLOPs and parameter count, the overall overhead remains within a reasonable range. Notably, under the SwinT framework, HDD-SwinT maintains a relatively low computational cost (42.67G), confirming that the modules achieve performance gains while maintaining efficiency and deployability. It is worth mentioning that HDDNet, based on ResNet-34, achieves the best performance with the lowest FLOPs and Params, further highlighting its superior balance between performance and efficiency.

To more intuitively demonstrate the enhancement effects of the proposed modules in different network architectures, we visualized the prediction results of the baseline models (U-Net and Swin Transformer) and their enhanced counterparts (HDD-Unet and HDD-SwinT) on the three datasets, as shown in Fig. 13. The results indicate that the original models tend to suffer from road discontinuity, blurred edges, and omissions in areas with complex backgrounds, occlusions, or narrow roads. In contrast, after integrating the DSGD and MCBE modules, both HDD-Unet and HDD-SwinT exhibit stronger structure recovery capabilities and clearer boundary delineation, accurately extracting continuous and complete road patterns. They show obvious advantages over the original models in detail modeling and structural connectivity. These findings further validate the excellent structure enhancement ability and cross-architecture generalization performance of the proposed modules, providing a robust and efficient general solution for remote sensing road extraction tasks.

Feature visualization comparison

In order to systematically verify the effectiveness of the proposed modules in this study, we designed a multi-dimensional feature visualization comparison experiment. Two representative road extraction scenarios were selected for the experiment. The key components in the HDDNet model architecture were visualized and analyzed, and their performance was compared with the common decoder of the classical road extraction model D-LinkNet15. We extracted the average feature maps of the three layers after the main decoder (integrated DSGD module) and the auxiliary decoder (integrated MCBE module) in HDDNet, respectively, and the average feature map after fusion by the DAFF module. As a comparison baseline, we simultaneously extracted the feature visualization results from the last three layers of the standard decoder in D-LinkNet. In this study, we selected two typical challenging scenarios for in-depth analysis, in which the red labeled regions are the key difficult regions for road extraction, and the final experimental results are shown in Figs. 14 and 15.

Figure 14 is a complex road scene, containing a main city road and several narrow winding path. From the visualization results, it can be clearly seen that the main decoder of HDDNet captures most of the main road and path junction features, and the auxiliary decoder also successfully extracts the boundary details of the road. In contrast, although the comparative D-LinkNet successfully recognizes the main urban roads, the features of the narrow paths in the feature maps are significantly blurred, and the spatial information appears cluttered, which prevents it from effectively distinguishing the road features.

Figure 15 illustrates a typical scene where there is severe occlusion. The visualization results show that the main decoder of HDDNet extracts the main features of the road, and the auxiliary decoder still carves out the precise boundary details in the case of severe occlusion interference. On the other hand, the road boundary extracted by D-LinkNet using the common decoder is obviously not smooth enough, and feature loss occurs at locations with more serious occlusion. It is worth noting that, as can be seen in both figures, the feature map after using the DAFF module, which combines the advantages of the two decoders, has more prominent road features and smoother and clearer road edge textures.

The experimental results show that the DSGD module proposed in this paper exhibits significant advantages in complex multi-scale road scene processing, and the MCBE module can significantly reduce the occlusion interference and maintain the integrity of the road boundary. The design of the heterogeneous dual-decoder enables the model to extract complementary semantic information, and combined with the DAFF feature fusion strategy, it successfully obtain a more accurate representation of the road features, and achieve significant improvements in both road integrity and boundary smoothness.

Conclusion

To address key challenges in remote sensing road extraction, such as complex road scales, significant occlusion interference, and blurred boundaries, this study proposes a novel heterogeneous dual-decoder network, HDDNet, which overcomes the feature expression limitations of traditional single-decoder and homogeneous dual-decoder architectures. Aiming at the problem of diverse road types and large morphological differences in remote sensing images, the Dynamic Snake Grouping Dilation (DSGD) module is constructed in the main decoder. This module effectively overcomes the limitations of the traditional fixed convolution kernel in curved roads and multi-scale feature extraction through the adaptive offset strategy of Dynamic Snake Convolution, together with the grouped multi-level dilation convolution strategy. To address the issues of occlusion interference and blurred boundaries, we designed the Multi-directional Connectivity and Boundary Enhancement (MCBE) module in the auxiliary decoder. This module establishes long-range road topology constraints through multi-directional strip convolutions and incorporates a direction-aware boundary enhancement mechanism based on direction-consistent Sobel operators. Finally, in order to realize the deep fusion of heterogeneous features, the Dual Attention Feature Fusion (DAFF) module is designed, which realizes the adaptive weighted fusion of heterogeneous features, reduces the redundancy, and improves the overall segmentation accuracy by establishing the spatial and channel dual-dimensional attention interaction mechanism. Comparison experiments on three public datasets, DeepGlobe, Ottawa and CHN6-CUG, show that HDDNet not only effectively extracts roads at different scales, but also has good generalization ability and robustness under complex scenes and occlusion interference, and its comprehensive performance reaches the advanced level of the current road extraction task.

This study not only provides a new technical solution for remote sensing road extraction, but also its proposed heterogeneous decoding architecture and direction-sensitive enhancement mechanism have universal reference value for similar linear feature recognition tasks such as vascular extraction and river segmentation. Although the proposed method demonstrates strong robustness and accuracy across various remote sensing road extraction scenarios, it still encounters certain limitations under extreme environmental conditions. Specifically, under conditions such as extensive cloud cover, dense fog, or low illumination, the image texture information is severely degraded, resulting in reduced performance in road boundary detection and fine structural recovery. To further enhance the model’s generalization capability, future research will explore multimodal information extraction strategies by integrating GPS trajectory data with RGB remote sensing imagery. By introducing GPS trajectory as spatial priors and aligning them with visual features across modalities, the approach is expected to significantly improve road recognition in weak-texture regions and enhance the model’s robustness and ability to accurately reconstruct road topology under challenging conditions.

Data availibility

The datasets used in this work can be downloaded as follows: DeepGlobe from http://deepglobe.org/challenge.html, Ottawa from https://open.ottawa.ca/, and CHN6-CUG from https://github.com/Z-yanan/CHN6-CUG-Roads-Dataset. All images used in Figs. 1 and 5 of this paper are sourced from the above-mentioned publicly available datasets.

Code availability

The source code of this project will be publicly released at https://github.com/lgg0606/HDDNet.

References

Hu, F., Xia, G.-S., Hu, J. & Zhang, L. Transferring deep convolutional neural networks for the scene classification of high-resolution remote sensing imagery. Remote Sens. 7, 14680–14707 (2015).

Akhtar, N. & Mandloi, M. Denseressegnet: A dense residual segnet for road detection using remote sensing images. In IEEE International Conference on Machine Intelligence and Geospatial Analytics and Remote Sensing (MIGARS) 1, 1–4. https://doi.org/10.1109/MIGARS57353.2023.10064603 (2023).

Liu, Y., Xiong, Z., Yuan, Y. & Wang, Q. Distilling knowledge from super-resolution for efficient remote sensing salient object detection. IEEE Trans. Geosci. Remote Sens. 61, 1–16 (2023).

Dong, S., Zuo, F., Chen, G., Fu, S. & Meng, X. A remote sensing image change detection method integrating layer-exchange and channel-spatial differences. IEEE J. Sel. Top. Appl. Earth Obs. Remote Sens. 18, 14804–14819. https://doi.org/10.1109/JSTARS.2025.3576831 (2025).

Abdollahi, A., Pradhan, B. & Shukla, N. Extraction of road features from uav images using a novel level set segmentation approach. Int. J. Urban Sci. 23, 391–405 (2019).

Shi, P., Dong, X., Ge, R., Liu, Z. & Yang, A. DP-M3D: Monocular 3D object detection algorithm with depth perception capability. Knowl.-Based Syst. 318, 113539. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.knosys.2025.113539 (2025).

Dong, X., Shi, P., Liang, T. & Yang, A. CTAFFNet: CNN–Transformer adaptive feature fusion object detection algorithm for complex traffic ccenarios. Transp. Res. Rec. 2679(1), 1947–1965. https://doi.org/10.1177/03611981241258753 (2024).

Hong, Z., Ming, D., Zhou, K., Guo, Y. & Lu, T. Road extraction from a high spatial resolution remote sensing image based on richer convolutional features. IEEE Access 6, 46988–47000 (2018).

Zhang, X., Zhang, C., Li, H. & Luo, Z. A road extraction method based on high resolution remote sensing image. Int. Arch. Photogramm. Remote Sens. Spatial Inf. Sci. 42, 671–676 (2020).

Alshehhi, R. & Marpu, P. R. Hierarchical graph-based segmentation for extracting road networks from high-resolution satellite images. ISPRS J. Photogramm. Remote Sens. 126, 245–260 (2017).

Song, M. & Civco, D. Road extraction using svm and image segmentation. Photogramm. Eng. Remote Sens. 70, 1365–1371 (2004).

Xiao, L., Dai, B., Liu, D., Hu, T. & Wu, T. CRF based road detection with multi-sensor fusion. In IEEE Intelligent Vehicles Symposium (IV) 192–198, https://doi.org/10.1109/IVS.2015.7225685 (2015).

Krizhevsky, A., Sutskever, I. & Hinton, G. Imagenet classification with deep convolutional neural networks. In Advances in Neural Information Processing Systems (NIPS) (2012).

Ronneberger, O., Fischer, P. & Brox, T. U-net: Convolutional networks for biomedical image segmentation. In Medical Image Computing and Computer-Assisted Intervention (MICCAI) 234–241 (Springer, 2015).

Zhou, L., Zhang, C. & Wu, M. D-Linknet: Linknet with pretrained encoder and dilated convolution for high resolution satellite imagery road extraction. In Proceedings of the IEEE Conference on Computer Vision and Pattern Recognition Workshops (CVPRW) 182–186 (2018).

Wang, Y., Seo, J. & Jeon, T. NL-Linknet: Toward lighter but more accurate road extraction with nonlocal operations. IEEE Geosci. Remote Sens. Lett. 19, 1–5 (2021).

Li, J., Liu, Y., Zhang, Y. & Zhang, Y. Cascaded attention denseunet (cadunet) for road extraction from very-high-resolution images. ISPRS Int. J. Geo-Inf. 10 (2021).

Wang, Y. et al. DDU-Net: Dual-decoder-u-net for road extraction using high-resolution remote sensing images. IEEE Trans. Geosci. Remote Sens. 60, 1–12 (2022).

Wang, R. et al. Robust road detection on high-resolution remote sensing images with occlusion by a dual-decoded unet. In IEEE International Geoscience and Remote Sensing Symposium (IGARSS) 5716–5719. https://doi.org/10.1109/IGARSS52108.2023.10281430 (2023).

Qi, Y., He, Y., Qi, X., Zhang, Y. & Yang, G. Dynamic snake convolution based on topological geometric constraints for tubular structure segmentation. In Proc. IEEE/CVF International Conference on Computer Vision (ICCV) 6070–6079 (2023).

Sun, T., Di, Z., Che, P., Liu, C. & Wang, Y. Leveraging crowdsourced gps data for road extraction from aerial imagery. In Proceedings of the IEEE/CVF Conference on Computer Vision and Pattern Recognition (CVPR) 7509–7518 (2019).

Ding, L. & Bruzzone, L. DiReSNet: Direction-aware residual network for road extraction in vhr remote sensing images. IEEE Trans. Geosci. Remote Sens. 59, 10243–10254 (2020).

Li, J. et al. Automatic road extraction from remote sensing imagery using ensemble learning and postprocessing. IEEE J. Sel. Top. Appl. Earth Obs. Remote Sens. 14, 10535–10547 (2021).

Chen, S.-B. et al. Dbranet: Road extraction by dual-branch encoder and regional attention decoder. IEEE Geosci. Remote Sens. Lett. 19, 1–5. https://doi.org/10.1109/LGRS.2021.3074524 (2022).

Wang, Q., Liu, Y., Xiong, Z. & Yuan, Y. Hybrid feature aligned network for salient object detection in optical remote sensing imagery. IEEE Trans. Geosci. Remote Sens. 60, 1–15 (2022).

Dong, S. & Chen, Z. Block multi-dimensional attention for road segmentation in remote sensing imagery. IEEE Geosci. Remote Sens. Lett. 19, 1–5. https://doi.org/10.1109/LGRS.2021.3137551 (2022).

Zhou, G., Chen, W., Gui, Q., Li, X. & Wang, L. Split depth-wise separable graph-convolution network for road extraction in complex environments from high-resolution remote-sensing images. IEEE Trans. Geosci. Remote Sens. 60, 1–15. https://doi.org/10.1109/TGRS.2021.3128033 (2022).

Wang, C. et al. Toward accurate and efficient road extraction by leveraging the characteristics of road shapes. IEEE Trans. Geosci. Remote Sens. 61, 1–16. https://doi.org/10.1109/TGRS.2023.3284478 (2023).

Liu, Y., Xiong, Z., Yuan, Y. & Wang, Q. Transcending pixels: Boosting saliency detection via scene understanding from aerial imagery. IEEE Trans. Geosci. Remote Sens. 61, 1–16 (2023).

Xiong, Y. et al. CFRNet: Road extraction in remote sensing images based on cascade fusion network. IEEE Geosci. Remote Sens. Lett. 21, 1–5. https://doi.org/10.1109/LGRS.2024.3409758 (2024).

Gao, L., Zhou, Y., Tian, J., Cai, W. & Lv, Z. Mcmcnet: A semi-supervised road extraction network for high-resolution remote sensing images via multiple consistency and multi-task constraints. IEEE Trans. Geosci. Remote Sens. (2024).

Meng, Q., Zhou, D., Zhang, X., Yang, Z. & Chen, Z. Road extraction from remote sensing images via channel attention and multilayer axial transformer. IEEE Geosci. Remote Sens. Lett. 21, 1–5. https://doi.org/10.1109/LGRS.2024.3379502 (2024).

Zhong, B. et al. FERDNet: High-resolution remote sensing road extraction network based on feature enhancement of road directionality. Remote Sens. https://doi.org/10.3390/rs17030376 (2025).

Gao, X. et al. An end-to-end neural network for road extraction from remote sensing imagery by multiple feature pyramid network. IEEE Access 6, 39401–39414. https://doi.org/10.1109/ACCESS.2018.2856088 (2018).

Li, Y. et al. Road extraction from unmanned aerial vehicle remote sensing images based on improved neural networks. Sensors. https://doi.org/10.3390/s19194115 (2019).

Mei, J., Li, R.-J., Gao, W. & Cheng, M.-M. CoANet: Connectivity attention network for road extraction from satellite imagery. IEEE Trans. Image Process. 30, 8540–8552 (2021).

Dai, L., Zhang, G. & Zhang, R. Radanet: Road augmented deformable attention network for road extraction from complex high-resolution remote-sensing images. IEEE Trans. Geosci. Remote Sens. 61, 1–13 (2023).

Deng, F. et al. UMIT-Net: A u-shaped mix-transformer network for extracting precise roads using remote sensing images. IEEE Trans. Geosci. Remote Sens. 61, 1–13. https://doi.org/10.1109/TGRS.2023.3281132 (2023).

Yang, R., Zhong, Y., Liu, Y., Lu, X. & Zhang, L. Occlusion-aware road extraction network for high-resolution remote sensing imagery IEEE Trans. Geosci. Remote Sens. (2024).

Yang, Z. et al. \(\text{ C}^{2}\)net: Road extraction via context perception and cross spatial-scale feature interaction. IEEE Trans. Geosci. Remote Sens. 62, 1–11. https://doi.org/10.1109/TGRS.2024.3491755 (2024).

Gong, X. et al. Hsroadnet: Hard-swish activation function and improved squeeze-excitation module network for road extraction using satellite remote sensing imagery. IEEE J. Sel. Top. Appl. Earth Obs. Remote Sens. 18, 4907–4920. https://doi.org/10.1109/JSTARS.2025.3533196 (2025).

Zhang, H., Yuan, H., Shao, M., Wang, J. & Liu, S. Swin-GAT fusion dual-stream hybrid network for high-resolution remote sensing road extraction. Remote Sens. 17, 2238. https://doi.org/10.3390/rs17132238 (2025).

Liu, P. et al. CGCNet: Road extraction from remote sensing image with compact global context-aware. IEEE Trans. Geosci. Remote Sens. https://doi.org/10.1109/TGRS.2025.3593017 (2025).

Dai, J. et al. Deformable convolutional networks. In 2017 IEEE International Conference on Computer Vision (ICCV) 764–773. https://doi.org/10.1109/ICCV.2017.89 (2017).

Li, H. et al. DEGANet: Road extraction using dual-branch encoder with gated attention mechanism. IEEE Geosci. Remote Sens. Lett. 21, 1–5. https://doi.org/10.1109/LGRS.2024.3464582 (2024).

Yu, W., Xie, B., Liu, D., Fang, C. & Zhang, J. Casdenet: Cascade automatic road detection network based on dynamic snake convolution and edge branch. In IEEE International Geoscience and Remote Sensing Symposium (IGARSS) 9517–9520. https://doi.org/10.1109/IGARSS53475.2024.10642645 (2024).

Li, Z., Pan, X., Yang, S., Yang, X. & Xu, K. DSMENet: A road segmentation network based on dual-branch dynamic snake convolutional encoding and multi-modal information iterative enhancement. In Advanced Intelligent Computing Technology and Applications 168–179 (Springer Nature Singapore, Singapore, 2024).

Liu, H., Zhou, X., Wang, C., Chen, S. & Kong, H. Fourier-deformable convolution network for road segmentation from remote sensing images. IEEE Trans. Geosci. Remote Sens. 62, 1–17. https://doi.org/10.1109/TGRS.2024.3476087 (2024).

Ma, X., Zhang, X., Zhou, D. & Chen, Z. StripUnet: A method for dense road extraction from remote sensing images. IEEE Trans. Intell. Veh. 9(11), 7097–7109. https://doi.org/10.1109/TIV.2024.3393508 (2024).

He, K., Zhang, X., Ren, S. & Sun, J. Deep residual learning for image recognition. In Proceedings of the IEEE Conference on Computer Vision and Pattern Recognition (CVPR) 770–778 (2016).

Kanopoulos, N., Vasanthavada, N. & Baker, R. Design of an image edge detection filter using the sobel operator. IEEE J. Solid-State Circuits 23, 358–367. https://doi.org/10.1109/4.996 (1988).

Dong, X., Shi, P., Qi, H., Yang, A. & Liang, T. TS-BEV: BEV object detection algorithm based on temporal-spatial feature fusion. Displays 84, 102814. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.displa.2024.102814 (2024).

Xu, Y., Shi, Z., Xie, X., Chen, Z. & Xie, Z. Residual channel attention fusion network for road extraction based on remote sensing images and GPS trajectories. IEEE J. Sel. Top. Appl. Earth Obs. Remote Sens. 17, 8358–8369. https://doi.org/10.1109/JSTARS.2024.3383596 (2024).

Li, L., Yi, J., Fan, H. & Lin, H. A lightweight semantic segmentation network based on self-attention mechanism and state space model for efficient urban scene segmentation. IEEE Trans. Geosci. Remote Sens. 63, 4703215. https://doi.org/10.1109/TGRS.2025.3562185 (2025).

Demir, I. et al. Deepglobe 2018: A challenge to parse the earth through satellite images. In 2018 IEEE/CVF Conference on Computer Vision and Pattern Recognition Workshops (CVPRW) 172–17209, https://doi.org/10.1109/CVPRW.2018.00031 (2018).

Liu, Y. et al. Roadnet: Learning to comprehensively analyze road networks in complex urban scenes from high-resolution remotely sensed images. IEEE Trans. Geosci. Remote Sens. 57, 2043–2056. https://doi.org/10.1109/TGRS.2018.2870871 (2019).

Zhu, Q., Zhang, Y., Wang, L., Zhong, Y. & Li, D. A global context-aware and batch-independent network for road extraction from vhr satellite imagery. ISPRS J. Photogramm. Remote Sens. 175, 353–365 (2021).

Burt, P. & Adelson, E. The Laplacian pyramid as a compact image code. IEEE Trans. Commun. 31(4), 532–540. https://doi.org/10.1109/TCOM.1983.1095851 (1983).

Ronneberger, O., Fischer, P. & Brox, T. U-Net: Convolutional networks for biomedical image segmentation. In Medical Image Computing and Computer-Assisted Intervention (MICCAI 2015), Lecture Notes in Computer Science, vol. 9351. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-319-24574-4_28 (Springer, 2015).

Liu, Z. et al. Swin transformer: Hierarchical vision transformer using shifted windows. In Proceedings of the IEEE/CVF International Conference on Computer Vision (ICCV) 10012–10022 (2021).

Acknowledgements

This research was funded by the National Natural Science Foundation of China grant number 12201185 and the Henan Science and Technology Development Plan Project grant number 242102210064.

Funding

This research was funded by the National Natural Science Foundation of China grant number 12201185 and the Henan Science and Technology Development Plan Project grant number 242102210064.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

Conceptualization, S.Q.; methodology, G.L.; software, S.Q.; validation, G.L. and X.Z.; formal analysis, Y.L.; investigation, G.L.; resources, S.Q.; data curation, X.Z.; writing—original draft preparation, S.Q. and G.L.; writing—review and editing, G.L and X.Z.; funding acquisition, S.Q. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher’s note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if you modified the licensed material. You do not have permission under this licence to share adapted material derived from this article or parts of it. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Qu, S., Liu, G., Zhang, X. et al. Heterogeneous dual-decoder network for road extraction in remote sensing images. Sci Rep 15, 31619 (2025). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-17445-9

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-17445-9