Abstract

This study examines the relationships between three built environment factors (i.e., urban density, transportation accessibility, and neighborhood design) and excess travel distance across three transportation modes: private vehicles (CAR), public transportation (PT), and active transportation (AT) in Gunsan, a medium-sized city in South Korea. Utilizing mobile phone-based mobility data, the analysis integrates Explanatory Factor Analysis, Multilevel Regression, and Extreme Gradient Boosting with Partial Dependence Plots to identify mode-specific and context-dependent patterns in travel inefficiencies. The findings indicate that increased density at both trip origins and destinations is generally associated with reduced excess travel distance, particularly for PT and AT users; however, extremely high density levels may induce inefficiencies for CAR and PT modes. Accessibility demonstrates a counterintuitive effect, where higher accessibility correlates with greater excess travel across all modes. In terms of urban design, a U-shaped relationship emerges for PT and AT modes: excess travel initially decreases at lower levels of design quality, increases at moderate levels (e.g., mid-range compactness and POI diversity), and then declines again at higher levels. This study contributes to offering (1) a more comprehensive understanding of how urban form influences travel efficiency, and (2) implications for enhancing urban efficiency and sustainability.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

As cities continue to grow and evolve, urbanization has emerged as both a driver of innovation1,2,3, economic development4,5,6, and a source of persistent challenges in spatial planning and mobility management7,8,9. Among the pressing concerns in cities is the design and operation of mobility systems that balance efficiency, equity, and sustainability10,11,12. Mobility systems are not merely logistical infrastructures to move people and goods; they can fundamentally shape environmental quality, economic productivity, and social equity13,14,15. Accordingly, understanding and mitigating inefficiencies in travel behavior is essential to improving the overall functionality and livability of urban areas.

Among these inefficiencies, excess travel, defined as travel that exceeds the minimum distance required to fulfill essential mobility needs16poses multifaceted challenges17,18. These inefficiencies manifest in multiple domains: environmentally, they increase greenhouse gas emissions, energy consumption, and pollution; economically, they raise transportation expenditures and reduce productivity; and socially, they exacerbate spatial inequities, disproportionately affecting vulnerable populations, such as low-income households and those without access to private vehicles who often face longer and less efficient commutes19,20,21,22,23. More importantly, excess travel reflects deeper structural dysfunctions embedded in urban systems, including poor land-use allocation, fragmented transportation networks, and unequal access to opportunities24,25.

From the land use planning perspective, addressing the burdens associated with excess travel is crucial for fostering sustainable, equitable, and livable urban environments20. It is imperative to identify the structural determinants that shape inefficient mobility patterns to address the excess travel. Existing literature recognizes the significance of socioeconomic factors and built environment attributes, particularly urban density, transportation accessibility, and neighborhood design features, in influencing travel behavior25,26,27. These elements of the built environment govern not only the spatial logic of travel routes but also the availability and attractiveness of modal options, ultimately conditioning both the demand and efficiency of urban travel20. For instance, Fan et al.28 demonstrated that relocating households to areas with higher density, diverse land use, and improved street connectivity can substantially reduce excess travel distances. Such findings underscore the interdependence between urban form and mobility outcomes, and highlight the potential of urban design interventions to reduce travel inefficiencies29.

Despite growing recognition of this relationship, research gaps persist in the empirical understanding of excess travel, particularly in medium-sized cities. Much of the existing research is concentrated in large metropolitan contexts, such as Seoul or New York, where high-capacity transit systems and compact urban forms are already well-developed30. Medium-sized cities, which often exhibit distinct urban morphologies and mobility patterns, have received far less attention despite their growing importance in regional development strategies31. Also, there remains limited understanding of how excess travel varies across transportation modes, such as private vehicles, public transportation, and active transportation, each of which presents unique behavioral, infrastructural, and spatial constraints32,33. Moreover, few studies explicitly consider the role of built environment characteristics at both the trip origin and destination. Lastly, most prior studies rely on traditional travel surveys and linear modeling techniques, which may be ill-suited to capture the non-linear, context-specific dynamics between built environment attributes and travel behavior20,34,35,36.

This study addresses these gaps by analyzing how built environment factors contribute to the travel inefficiencies across CAR, PT, and AT in Gunsan, a medium-sized city in South Korea. The analysis focuses on three core dimensions of the built environment (i.e., urban density, transportation accessibility, and neighborhood design) measured at both trip origins and destinations to reflect the bidirectional nature of travel. Methodologically, the study integrates Explanatory Factor Analysis (EFA) to reduce dimensionality among built environment features, Multilevel Regression (MLR) to account for hierarchical data structures, and Extreme Gradient Boosting (XGBoost) with Partial Dependence Plots (PDPs) to capture non-linear and threshold effects. Also, this research uses high-resolution mobile phone-based mobility data to enable a mode-specific analysis of individual excess travel behavior. This study contributes to a deeper understanding of how spatial form interacts with mobility behavior, reinforcing the importance of built environment interventions as levers for enhancing transportation efficiency, equity, and sustainability.

Literature review

The concept of excess travel, defined as the additional travel time or distance incurred due to suboptimal spatial configurations between origins and destinations, has long been a subject of inquiry in urban transportation research18. The seminal work of Hamilton37 critically challenged the assumptions of the monocentric urban model, which posits that commuting behavior is governed by a rational trade-off between housing and transportation costs38. According to this classical framework, individuals are expected to minimize their commuting burdens by optimizing the spatial proximity between residential and workplace locations39,40. However, Hamilton37 revealed substantial gaps between actual commuting distances and the theoretical minimum, suggesting that real-world travel behavior is shaped by factors beyond mere cost-minimization, such as residential preferences, job quality, and socio-spatial constraints19. These findings represented a pivotal turning point in urban economic theory, as they exposed the limitations of overly simplistic spatial models and catalyzed a more nuanced, empirically grounded investigation into the complexities of excess travel.

Since then, a substantial body of literature has evolved, examining excess travel from multiple perspectives, including: (1) the spatial patterns of excess commuting and (2) its environmental and societal impacts16. First, the majority of research has concentrated on excess commuting, often operationalized as the ratio between observed commuting distances and the theoretical minimum derived from spatial interaction models25. The longitudinal analysis of excess commuting in U.S. metropolitan areas by Liu and Quan41for instance, identified a temporal trend characterized by increasing excess commuting during the 1990s, followed by a decline in the subsequent decade. This trajectory was attributed to intensified spatial mismatches between housing and employment opportunities, driven by the neoliberal restructuring of housing and labor markets. While excess commuting has been extensively studied, non-commute-related excess travel has gained attention in recent years17,24,42. For example, Cheng and Chen43 studied school commutes in Xi’an, China, revealed that over half of school-related travel distances were excessive, primarily due to residential relocation, preferences for higher-quality educational institutions, and increased accessibility to motorized transport. Their findings underscore the role of institutional factors, such as the school district system, in mitigating travel inefficiencies. The phenomenon of voluntary excess travel is also evident in non-work-related trip purposes, reflecting the multifaceted nature of travel behavior that extends beyond economic rationality.

Second, the societal implications of excess travel are profound, particularly regarding environmental externalities. Wadud et al. 18 examined high-mileage car users in England and found that the top 5% of travelers disproportionately contributed to greenhouse gas emissions, highlighting the unequal distribution of environmental burdens. Their study proposed policy interventions such as mileage rationing schemes to target excessive travel behavior among high-mileage users, aligning with broader goals of sustainable transportation and emissions reduction. Such excess travel behavior exacerbates urban congestion and undermines transportation system efficiency, imposing significant social costs that necessitate strategic policy responses. Furthermore, a body of literature incorporates equity considerations into excess travel research, often employing spatial equity frameworks to examine the distributional and spatial consequences of transportation inefficiencies. For instance, a previous study in Seoul revealed that areas with limited transit accessibility and poor jobs-housing balance exhibited disproportionately high levels of excess commuting44. The application of equity perspective in transportation research has revealed the uneven spatial impacts of excess travel, particularly in regions with stark disparities in urban form and infrastructure provision.

Furthermore, a growing body of research has explored the built environment effects and consistently demonstrated that attributes such as urban density, land-use diversity, and street design significantly influence travel distances and mode choices45,46,47,48,49. For instance, a research of Fan et al.28 in the Research Triangle Area of North Carolina quantified the potential reductions in travel distances achievable through residential relocation to higher-density, mixed-use neighborhoods with enhanced street connectivity. However, their findings also highlighted trade-offs with other locational attributes, such as safety and access to high-quality schools. Similarly, an analysis of suburbanization and urban decentralization by Yang50 revealed that excess commuting often exacerbate spatial mismatches and increase commute distances, reflecting the inefficiencies associated with fragmented urban development. Cervero and Kockelman51 found local-scale built environment factors associated with excess commuting are density, diversity, and design.

Recent studies in the area have expanded the scope of inquiry by (1) integrating advanced metrics of urban form25such as sprawl indices, polycentricity indices, and job-housing balance measures, and (2) using advanced methodological approaches, such as Interpretable Machine Learning (IML), and detailed data sets, such Mobile Phone-based Mobility Data23,52. For instance, Ha et al.53 examined the effect of proximity to employment center on commuting distance, and found that increased commuting distances in Los Angeles was associated with increasing the distance to the center. Ha et al.25 estimated four indices on sprawl, polycentricity, job-housing dispersal, and central city dominance, and explored their associations with excess commuting in 206 U.S. metropolitan areas. They demonstrated that greater polycentricity tends to intensify cross-commuting, while higher central city dominance alleviates excess commuting. Their findings confirmed the detrimental impacts of urban sprawl and job-housing dispersal on commuting efficiency. Additionally, research by Zhang and Wang54 highlighted the significance of achieving a high job-household balance ratio to minimize excess commuting, while Hu et al.55 documented the inefficiencies arising from sprawling urban fabrics in major U.S. cities such as Atlanta and Los Angeles.

Despite the body of literature, there are several research gaps that remain insufficiently explored. Although the link between urban form and travel inefficiency has been widely acknowledged, empirical investigations into excess travel, particularly within medium-sized urban contexts, are still limited. Moreover, only a limited number of studies have explored how excess travel behaviors differ across various transportation modes, including CAR, PT, and AT, even though each mode is shaped by distinct spatial, infrastructural, and behavioral dynamics. Another limitation in prior research is the tendency to examine built environment characteristics solely at either the origin or the destination of trips, neglecting the combined influence of both points, despite the inherently bidirectional nature of most travel. Lastly, few studies capture the non-linear interactions and context-dependent patterns that define the relationship between built environment features and excess travel behaviors.

Materials and methods

The methodological framework of this study includes three components, as illustrated in Fig. 1.: (1) estimating excess travel distance for CAR, PT, and AT using mobile phone-based floating population data, (2) operationalizing density, accessibility, and design at both origin and destination using EFA, and (3) using MLR and PDP to explore relationships how the three built environment features are associated with the excess travel distance in Gunsan.

Study area

Gunsan, a medium-sized coastal city in southwestern South Korea, is the focus of this study. With a population of approximately 265,160 in 2022 and covering 377.7 square kilometers, the city features a mixed urban, industrial, and rural landscape (Fig. 2). Historically, Gunsan grew rapidly after the development of its port, becoming a key economic hub. However, national industrialization policies from the 1970s onward shifted focus to other regions, resulting in economic stagnation and a reduced role in spatial structure of South Korea56. In recent years, a government-led regeneration initiative has aimed to revitalize the declining downtown, create jobs, improve living conditions, and foster social integration57.

Estimating excess travel distance

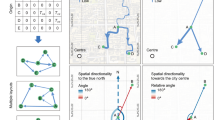

We estimate excess travel distance by following a multi-step analytical framework. First, we construct an origin-destination (OD) matrix for Gunsan using GPS signals and base-station connection logs (see Fig. 3). OD captures intra-city travel flows between H3 cells over a five-day study period (October 16–20, 2024), with each OD pair containing metadata on departure and arrival times, estimated routes, and travel distances. Second, we incorporate mode-specific, trip-level information derived from multi-sensor fusion algorithms applied to smartphone telemetry data. These algorithms classify each trip into one of three transportation modes, CAR, PT, and AT, based on movement speed, spatial trajectory, and proximity to known transit facilities. Third, we quantify excess travel distance by comparing the observed travel distance with the shortest feasible network distance between the origin and destination H3 cells.

Origin-destination matrix (The map was generated using Kepler, at https://kepler.gl).

The mobility data utilized in this study are sourced from SK Telecom (SKT), a major South Korean telecommunications provider, and are fully anonymized and aggregated under a formal research agreement. The dataset comprises high-resolution, spatiotemporally tagged mobility records, structured using the H3 hierarchical hexagonal spatial indexing system, which ensures consistent spatial granularity across the urban landscape. This data source addresses several limitations of conventional datasets58,59. Unlike static and often outdated census or survey data, mobile phone-based data enable near real-time monitoring of population dynamics and mobility flows60,61. Prior research has demonstrated its utility in modeling transportation demand and in calibrating key transportation metrics, including trip generation, distribution, and modal split62. Moreover, the fine spatial resolution, characterized by H3 cells with side lengths under 500 m, enables detailed insights into intra-urban mobility patterns, facilitating the identification of localized traffic dynamics and mobility hotspots.

The classification into three transportation modes, as shown in Table 1, is grounded in both methodological considerations and planning relevance. First, the dataset used in this study provides moderate to high-resolution spatiotemporal trajectories derived from GPS signals and base-station logs. While sufficient for identifying general travel patterns and speeds, the data lack the granularity required to reliably distinguish between sub-modes (e.g., bus vs. subway, or walking vs. micromobility). As such, broader modal categories enhance classification reliability and align with the resolution of the data. Second, this classification is consistent with established frameworks in transportation planning63capturing key differences in infrastructure use, travel behavior, and environmental impact. It offers a policy-relevant lens for interpreting excess travel and informing targeted interventions. Therefore, the three-mode framework represents a methodologically sound and context-appropriate approach that balances analytical rigor with the constraints of the dataset.

Several assumptions underlie our use of this dataset. First, it assumes that the sample of mobile phone users is broadly representative of the general population of Gunsan in terms of travel behavior, spatial distribution, and modal preferences. Second, the five-day study window is presumed to reflect typical weekday mobility conditions, although it may not capture long-term seasonal or event-driven variations. Third, we limit our analysis to inland travel, excluding maritime trips under the assumption that they fall outside the scope of urban mobility inefficiencies. Fourth, we assume that the spatial and temporal quality of the location data, including GPS accuracy and base-station density, is sufficiently consistent across the study area. Finally, the classification of transportation modes is assumed to be robust, based on well-established movement indicators, though we acknowledge the possibility of minor misclassification in some cases.

Operationalizing density, accessibility, and design

To operationalize the three built environment dimensions, we apply EFA to reduce the dimensionality of eight spatial variables collected at both trip origins and destinations. We choose the eight built environment factors based on their theoretical relevance45,48 and empirical significance in shaping urban mobility patterns, spatial accessibility, and functional characteristics of urban environments34,64,65. These variables include: (1) distance to the nearest bus stop, (2) distance to downtown, (3) distance to the nearest elementary school, (4) population density, (5) average building height, (6) average site area, (7) point-of-interest (POI) diversity, and (8) compactness index (i.e., total floor area within a 500 m x 500 m grid). There are several reasons to use EFA in this study. First, the use of EFA addresses multicollinearity concerns among the original variables, which could otherwise bias regression estimates and reduce model interpretability23,66,67. Also, by summarizing the variance of correlated indicators into distinct, uncorrelated factors, EFA improves the robustness and interpretability of our MLR and PDP models68,69,70.

To extract latent dimensions from the selected built environment variables, we first compile these variables into a unified dataset and conduct EFA. A varimax rotation is applied to improve the interpretability of factor loadings by enhancing variable differentiation across components. The scree plot of eigenvalues indicates that three or four factors may be appropriate for retention. Based on both statistical evidence and the conceptual coherence of the factor loadings45,48we retain three latent constructs, as presented in Table 2. This decision aligns with established practices in dimensionality reduction and supports the theoretical framework underlying our categorization of density, accessibility, and design35,71 (see Table 3).

Exploring relationships between excess travel distance and built environment

We explore relationship between excess travel distance and built environment factors by using MLR to analyze hierarchically nested data with two spatial dimensions: the H3 cell level and the route level. The need for MLR in this study is further underscored by its role in the preliminary analysis before applying PDP in IML. We choose MLR over ordinary least squares regression models (OLS) for the following reasons. Observations within the same spatial unit (such as an H3 cell or route) may share common characteristics, and these dependencies must be accounted for to avoid biased estimates75. OLS assumes independence between observations, which becomes problematic when data exhibits spatial or group-level correlations76. When properties within the same spatial unit are more similar to each other than to those in other units, OLS regression can underestimate standard errors, inflating statistical significance and leading to inaccurate conclusions. In contrast, MLR accounts for these nested structures, incorporating variability at each spatial level and providing more reliable estimates of relationships between property characteristics and dependent variables77.

To further investigate the non-linear and threshold effects of built environment factors on excess travel distances for the three transportation modes, we employ XGBoost, which is a highly effective machine learning algorithm, renowned for its capability to model complex, non-linear relationships and variable interactions78,79. Unlike linear models such as MLR, which assume a linear relationship between dependent and independent variables, XGBoost allows for the flexible modeling of intricate dependencies without requiring pre-specified functional forms80,81. XGBoost operates through an ensemble of decision trees, where each successive tree corrects the errors of its predecessors, resulting in a robust predictive model82. To ensure optimal performance of the XGBoost models, we apply a parameter tuning using a grid search process63,83validated using cross-validation84,85 to assess model performance on the data (see Table 4). For the IML technique, we utilize PDP to interpret the results of the XGBoost models, which provide insights into the marginal effects of individual variables or pairs of variables on the predicted outcomes86,87. PDPs are particularly effective for visualizing non-linear and threshold effects, which are often challenging to identify using regression methods like MLR88.

Variables

We analyze three dependent variables, each representing the excess travel distance associated with one of the three transportation modes (see Table 5). Figure 4 illustrates the spatial distribution of excess travel distances across trip origins and destinations for each mode, while Fig. 5 presents the results of a hot spot analysis identifying statistically significant clusters of high and low excess travel using ArcGIS Pro 3.3. The figures reveal that central urban areas (e.g., downtown districts and industrial zones) exhibit relatively higher levels of excess travel distance across all transportation modes, whereas rural and peripheral areas are associated with lower excess travel distances. This pattern may be attributed to several structural and functional characteristics. First, the concentration of economic activities and employment opportunities in central and industrial areas likely generates more complex and circuitous travel patterns, as individuals from dispersed residential locations converge on these hubs. Second, land-use intensity along wit inadequate transport infrastructure may increase congestion and reduce route efficiency, particularly for motorized and public transit modes. Third, for PT and AT users, first- and last-mile challenges, along with indirect routing through transit networks, may further contribute to excess distance when traveling to or from central locations.

The independent variables include (1) the three built environment factors and (2) control factors, such as route characteristic and spatial-temporal factors (see Table 5). The core variables, Density, Accessibility, and Design, are derived through EFA, representing foundational dimensions of the built environment48. These factors are examined at trip origin and destination points, thereby accounting for the inherently bidirectional nature of travel behavior30. To evaluate potential interdependencies among built environment variables, particularly in light of the use in the MLR and PDP analysis, we conducted a Variance Inflation Factor (VIF) assessment using an OLS model. All variables exhibited VIF values below 5, indicating that multicollinearity is not a significant concern in the present dataset. However, we recognize that the built environment operates through complex, interrelated mechanisms89,90.

To capture additional determinants of travel inefficiencies, we incorporate a set of route-specific variables, including travel time, straight-line distance, and traffic volume (see Table 5). They are central to mobility patterns91,92influencing perceived travel costs, convenience, and ultimately mode selection. In addition, spatial-temporal variables are included to capture fluctuations in travel behavior across different days and time periods93. For instance, weekend travel behavior often exhibits a greater reliance on private vehicles and a reduced use of public transit. Incorporating temporal variation enables a more accurate reflection of real-world travel dynamics94. Furthermore, H3 spatial identifiers are employed for both origins and destinations to control for localized variations in land use, urban form, and transportation infrastructure, allowing the model to account for spatial heterogeneity in excess travel.

Result

Preliminary analysis results

Table 6 presents the results of four MLR models for total trips, disaggregated by transportation mode: CAR, PT, and AT. The results reveal that higher density at both trip origins and destinations is associated with reduced excess travel distance. Negative coefficients for density (-0.70 at origins and − 0.91 at destinations) reflect the principles of compact urbanism, where densification reduces the need for excess travel by promoting spatial proximity. This effect is particularly strong for PT users (-1.02 at origins and − 1.28 at destinations), emphasizing the density-dependent efficiency of transit-oriented development (TOD) networks. Interestingly, even for car users, density coefficients (-0.77 for origin and − 0.81 for destination) suggest that dense urban morphologies improve accessibility by facilitating shorter trip generation distances.

Accessibility, defined as the ease of reaching opportunities, shows a positive relationship with excess travel distance, with coefficients of 0.21 at origins and 0.25 at destinations. Here, a higher accessibility indicator indicates greater distances to downtown, bus stops, and schools. This finding suggests that better accessibility encourages shorter trips, reflecting the mobility-oriented perspective on accessibility. The effect is particularly strong for CAR users (0.25 at origins and 0.30 at destinations), who benefit from greater trip-making freedom. For PT and AT trips, the effects are positive but less significant, reflecting their more localized travel ranges despite improved accessibility.

The design factor, operationalized as compact and diverse land-use configurations, demonstrate significant negative effects on excess travel distance (-0.07 for origins and − 0.08 for destinations). These findings indicate that well-designed urban environments enhance trip efficiency by promoting direct routing and reducing spatial detours. PT users show the greatest sensitivity to design (-0.26 for origins and − 0.28 for destinations), highlighting the reliance of transit systems on integrated land-use planning. Similarly, AT users benefit significantly from compact urban forms (-0.10 for origins and − 0.12 for destinations), which improve walkability and bikeability through better first- and last-mile connectivity.

Control covariates provide additional insights. Travel time (coefficient: 2.95) and traffic volume (coefficient: 0.42) are positively associated with excess travel distance, corroborating findings in previous studies on congestion-induced inefficiencies91. As expected, straight-line trip distance (coefficient: 5.89) is strongly correlated with excess travel distance, and weekend trips (coefficient: 0.25) are associated with slightly higher inefficiencies, likely due to discretionary trip purposes. Additionally, the random effects analysis reveals significant heterogeneity at both the trip origin and destination levels.

Non-linear effects of built environment on excess travel

PDPs visualize the marginal effect of the independent variable, in this case, density derived from EFA, on the dependent variables: excess travel distance for (a) CAR, (b) PT, and (c) AT trips. They are also illustrated separately for origin (1) and destination (2) densities. The red lines in PDPs represent the smoothed overall trends between independent variable and the excess travel distance.

First, the PDPs on the density effect in Fig. 6 reveal non-linear and fluctuating patterns that suggest varying impacts in different density ranges, which extends previous findings. For car trips, increasing origin density initially reduces excess travel distance, indicating improved accessibility and shorter trips. However, at very high densities, excess travel distance begins to rise in the medium-sized city, likely due to congestion, limited parking, or network inefficiencies. Similarly, destination density reduces excess travel distance at moderate levels but shows a slight increase at very high densities, reflecting challenges in hyper-dense urban areas. For PT trips, excess travel distance declines significantly as density increases, reaching a minimum at moderate levels before rising slightly at higher densities. This suggests that moderate densities optimize transit coverage and access but that very high densities may induce inefficiencies, such as overcrowding or transit saturation. For AT trips, increasing density consistently reduces excess travel distance, particularly at mid-to-high-density ranges, emphasizing the strong correlation between density and active transportation efficiency.

Regarding accessibility, Fig. 7 reveals that excess travel distance for the three transportation modes decreases as accessibility indicators increase (i.e., in less accessible areas). One possible explanation is that in less accessible areas (with higher accessibility indicators), drivers may consolidate trips or optimize routes more effectively, especially when destinations are farther apart, thus reducing excess travel distance in medium-sized cities. Additionally, transit networks in these areas may feature fewer but more direct routes, resulting in shorter trips despite greater distances to key locations. This suggests that PT efficiency is not solely determined by spatial accessibility but also by network design and operational characteristics. A similar trend is observed for AT trips, where excess travel distance decreases as accessibility indicators increase. A potential explanation is that AT users in less accessible areas may strategically plan their trips or select destinations within a manageable range, leading to more efficient travel behavior despite lower accessibility.

Lastly, the design effect of Fig. 8 demonstrates that design improvements (i.e., greater land-use diversity and higher compactness) consistently reduce excess travel distance for PT and AT trips. More specifically, excess travel distance for CAR initially increases with higher design indicators at the destination, consistent with potential challenges such as congestion, parking limitations, or navigation complexity in well-designed urban areas. However, this trend reverses when design indicators reach significantly high levels, leading to a reduction in excess travel distance. For PT trips, excess travel distance initially increases with higher design indicators at both origin and destination, potentially due to transit inefficiencies in compact and diverse land-use areas, such as longer access times to stops or increased passenger demand. However, as design indicators reach higher levels, excess travel distance begins to decline, suggesting that well-planned, highly integrated transit systems can eventually overcome initial inefficiencies. Lastly, AT trips reveal a similar U-shaped relationship between the design indicator and excess travel distance in both origin and destination contexts. At significantly higher levels of urban design, excess travel distance declines significantly, suggesting that well-planned, highly walkable or bikeable environments with seamless connectivity and adequate infrastructure can mitigate initial inefficiencies and promote efficient travel.

Discussions

Major findings

Our MLR model reveals that the built environment factors, density, accessibility, and design, exhibit significant associations with excess travel distance across all modes in the medium-sized city. These findings are largely consistent with those of previous studies45,48. In addition to the linear relationships, the analysis identifies non-linear patterns and threshold effects associated with the built environment characteristics. Specifically, higher density at both origins and destinations is associated with reduced excess travel distance, in line with the principles of compact urbanism72. PT users show the greatest sensitivity to density, highlighting the efficiency of dense, transit-oriented networks. However, a U-shaped relationship emerges, where excess travel distance decreases at moderate densities but increases at very high densities.

Moreover, accessibility effects show that excess travel distance decreases across all three transportation modes as accessibility indicators rise (i.e., less accessible areas to public transportation, downtown, and school in this study). This finding contrasts with the conventional assumption that proximity to key destinations reduces travel inefficiencies95,96. One explanation is that in areas with higher accessibility indicators, drivers may consolidate trips or optimize routes more effectively, particularly when destinations are further apart, resulting in shorter excess travel distances in medium-sized cities. Additionally, transit systems in these areas might have fewer but more direct routes, which can shorten trip lengths even if key destinations are farther away. A similar pattern is observed for AT trips. This may be due to AT users in less accessible areas carefully planning their trips or choosing destinations within a manageable distance, leading to more efficient travel despite lower overall accessibility.

The findings also reveal that urban design improvements, such as increased land-use diversity and compactness (i.e., total floor area within a 500 m x 500 m grid), reduce excess travel distance for PT and AT trips, which is largely aligns with previous studies34,45. For CAR trips, excess travel distance initially rises with higher design indicators due to factors like congestion and parking limitations but decreases once design indicators reach high levels. For PT trips, excess travel distance increases at first, likely due to transit inefficiencies, but decreases as design quality improves. Similarly, AT trips exhibit a U-shaped relationship, with excess travel distance declining significantly at higher levels of urban design, highlighting the importance of well-planned, integrated, and accessible environments for efficient travel.

Policy implications

The findings offer several important implications. First, the fluctuating effects of density on travel distance emphasize the importance of achieving an optimal density balance in medium-sized cities. While moderate density at both origins and destinations can reduce excess travel distance by improving accessibility and minimizing congestion, very high densities may lead to inefficiencies, such as congestion, parking limitations, and transit saturation. Policymakers should focus on identifying and maintaining density thresholds that balance the benefits of compact urbanism with the potential drawbacks of hyper-density, ensuring that density is tailored to the specific needs and capacities of each urban area.

Second, the study reveals that in less accessible areas, travel distance can be reduced through improved accessibility indicators, challenging the conventional view that proximity to key destinations always minimizes travel inefficiencies. For car users, policies should focus on improving network efficiency, such as through trip consolidation or route optimization, especially in areas with lower accessibility. For PT and AT, enhancing accessibility by integrating more direct routes, improving first- and last-mile connectivity, and ensuring well-designed infrastructure in less accessible areas can lead to more efficient travel behavior, even in areas with lower proximity to key destinations. The findings imply that the transportation policies and urban design strategies that work in large, dense cities may not be directly transferable to medium-sized cities.

Lastly, the findings suggest that urban design plays a critical role in reducing excess travel distance, especially for PT and AT trips. Well-designed urban areas with greater land-use diversity and higher compactness (i.e., total floor area) can significantly reduce travel inefficiencies. However, the study also indicates that excessively compact or diverse environments may initially introduce inefficiencies due to factors such as longer access times to transit stops or increased passenger demand. Therefore, urban policies should aim to strike a balance in design, ensuring that transit and active transportation systems are well-integrated, with seamless connectivity and sufficient capacity to handle demand. In the case of CAR trips, policymakers should focus on reducing congestion and improving navigation in densely designed areas, while also ensuring that land-use diversity supports efficient car travel.

Limitations of this study

While this study offers significant contributions to the field, it is essential to acknowledge several limitations that constrain its scope and generalizability. First and foremost, the conceptual framework utilized in this study to assess excess travel provides valuable insights but falls short of fully capturing the complexities associated with commuting inefficiencies. Accurately determining true excess commuting requires separating unavoidable commuting distances from those arising from discretionary choices. While excess travel is often viewed as inefficient, it can also reflect individual or societal priorities, such as seeking better educational opportunities, improved employment prospects, or safer living environments. This indicates that excess travel is not solely a measure of inefficiency but rather a reflection of the intricate balance between personal preferences and structural factors. However, this study could not delve into these aspects due to data limitations. Future research should employ mixed-method approaches, including qualitative analyses, to more comprehensively explore the multifaceted nature of excess travel and its broader implications for urban planning and policy development.

Furthermore, the use of mobile phone-based mobility data, although invaluable for capturing large-scale, spatiotemporal movement patterns, presents inherent limitations. Key drawbacks include sampling bias due to unequal mobile device ownership and usage; the significant preprocessing required to clean, filter, and aggregate raw data; dependency on the spatial distribution of cell towers, which can introduce locational inaccuracies in underrepresented areas; assumptions about the uniform distribution of population within grid cells; and privacy concerns associated with tracking individual movements, even if anonymized52,97. Specifically, mobile phone data may exhibit sampling biases due to disparities in mobile phone ownership and usage patterns, potentially excluding certain demographic groups (e.g., individuals without smartphones or those with limited mobility). Also, the dataset, collected during specific time period, reflects a static snapshot of mobility patterns rather than evolving dynamics. These biases necessitate caution in interpreting the results and call for the integration of complementary datasets, such as travel surveys, to enhance the robustness of the analyses.

There are additional limitations to acknowledge. For instance, the cross-sectional nature of the data employed restricts the ability to capture temporal variations or longitudinal trends in travel behavior and urban form. Moreover, the geographic focus on Gunsan inherently limits the generalizability of the findings to other urban contexts, particularly cities with distinct socioeconomic, cultural, and spatial characteristics. Additionally, while this research emphasizes key built environment attributes, it does not account for additional contextual variables, such as individual socioeconomic characteristics, trip purposes, or the influence of land-use policies, that may significantly affect travel behavior. Future studies need to address the issues to expand our understanding of the relationships.

Conclusion

This study provides empirical insights into the ways in which built environment attributes, specifically density, accessibility, and urban design, influence excess travel distances across three transportation modes (i.e., CAR, PT, and AT) in the context of Gunsan, a medium-sized city in South Korea. By integrating EFA, MLR, XGBoost, and PDP with mobile phone-based mobility data, the study captures the non-linear and threshold effects of built environment factors on mode-specific travel inefficiencies. This study contributes to the broader understanding of how urban form shapes travel behavior and offers actionable insights for planners and policymakers seeking to reduce excess travel, promote efficient transportation systems, and enhance urban livability. Also, this work expands the academic discourse on excess travel by focusing on medium-sized cities, which are often underrepresented in transportation research. The last contribution of this research lies in its multi-dimensional and data-driven approach to understanding excess travel. It moves beyond traditional linear frameworks by using high-resolution, smartphone-based mobility data and advanced modeling techniques to reveal mode-sensitive and context-dependent relationships.

Data availability

The datasets used and/or analysed during the current study available from the corresponding author on reasonable request.

References

Bartlett, A. et al. The City as an Entertainment Machine (Lexington Books, 2011).

Florida, R. The creative class and economic development. Econ. Dev. Q. 28, 196–205 (2014).

Balland, P. A., Boschma, R. & Frenken, K. Proximity and innovation: from statics to dynamics. Reg. Stud. 49, 907–920 (2015).

Glaeser, E. L. Triumph of the City: How our Greatest Invention Makes Us Richer, Smarter, Greener, Healthier, and Happier (Penguin, 2011).

Chatman, D. G. & Noland, R. B. Do public transport improvements increase agglomeration economies?? A review of literature and an agenda for research. Transp. Rev. 31, 725–742 (2011).

Credit, K. Accessibility and agglomeration: A theoretical framework for Understanding the connection between transportation modes, agglomeration benefits, and types of businesses. Geogr. Compass. 13, e12425 (2019).

Neffke, F., Henning, M., Boschma, R., Lundquist, K. J. & Olander, L. O. The dynamics of agglomeration externalities along the life cycle of industries. Reg. Stud. 45, 49–65 (2011).

Adler, M. W. & van Ommeren, J. N. Does public transit reduce car travel externalities? Quasi-natural experiments’ evidence from transit strikes. J. Urban Econ. 92, 106–119 (2016).

Florida, R. The New Urban Crisis: How our Cities Are Increasing Inequality, Deepening Segregation, and Failing the Middle Class-and What We Can Do about It (Basic Books, 2017).

Abduljabbar, R. L., Liyanage, S. & Dia, H. The role of micro-mobility in shaping sustainable cities: A systematic literature review. Transp. Res. Part. Transp. Environ. 92, 102734 (2021).

Beojone, C. V. & Geroliminis, N. On the inefficiency of ride-sourcing services towards urban congestion. Transp. Res. Part. C Emerg. Technol. 124, 102890 (2021).

Lee, S., Im, J. & Cho, K. Understanding Spatial inequalities and stratification in transportation accessibility to social infrastructures in South korea: multi-dimensional planning insights. Sci. Rep. 14, 18445 (2024).

Mouratidis, K. Urban planning and quality of life: A review of pathways linking the built environment to subjective well-being. Cities 115, 103229 (2021).

Magazzino, C. & Mele, M. On the relationship between transportation infrastructure and economic development in China. Res. Transp. Econ. 88, 100947 (2021).

Sanchez-Sepulveda, M. V., Navarro, J., Fonseca-Escudero, D., Amo-Filva, D. & Antunez-Anea, F. Exploiting urban data to address real-world challenges: enhancing urban mobility for environmental and social well-being. Cities 153, 105275 (2024).

Ma, K. & Banister, D. Excess commuting: A critical review. Transp. Rev. 26, 749–767 (2006).

Horner, M. W. & O’Kelly, M. E. Is non-work travel excessive? J. Transp. Geogr. 15, 411–416 (2007).

Wadud, Z., Adeel, M., Anable, J. & Lucas, K. A disaggregate analysis of ‘excess’ car travel and its role in decarbonisation. Transp. Res. Part. Transp. Environ. 109, 103377 (2022).

Ling, C., Niu, X., Yang, J., Zhou, J. & Yang, T. Unravelling heterogeneity and dynamics of commuting efficiency: Industry-level insights into evolving efficiency gaps based on a disaggregated excess-commuting framework. J. Transp. Geogr. 115, 103820 (2024).

Tong, Z., An, R., Zhang, Z., Liu, Y. & Luo, M. Exploring non-linear and spatially non-stationary relationships between commuting burden and built environment correlates. J. Transp. Geogr. 104, 103413 (2022).

Choi, J., Coughlin, J. F. & D’Ambrosio, L. Travel time and subjective Well-Being. Transp. Res. Rec. 2357, 100–108 (2013).

Halonen, J. I. et al. Commuting time to work and behaviour-related health: a fixed-effect analysis. Occup. Environ. Med. 77, 77–83 (2020).

Lee, S. Relationships between transportation expenditures and built environment in the united states: insights from interpretable Machine-Learning approach. J. Plan. Educ. Res. https://doi.org/10.1177/0739456X241268464 (2024).

Kanaroglou, P. S., Higgins, C. D. & Chowdhury, T. A. Excess commuting: a critical review and comparative analysis of concepts, indices, and policy implications. J. Transp. Geogr. 44, 13–23 (2015).

Ha, J., Lee, S. & Kwon, S. M. Revisiting the relationship between urban form and excess commuting in US metropolitan areas. J. Plan. Educ. Res. 41, 294–311 (2021).

Bai, X., Zhai, W., Steiner, R. L. & He, Z. Exploring extreme commuting and its relationship to land use and socioeconomics in the central Puget sound. Transp. Res. Part. Transp. Environ. 88, 102574 (2020).

Zhao, P. The determinants of the commuting burden of low-income workers: evidence from Beijing. Environ. Plan. Econ. Space. 47, 1736–1755 (2015).

Fan, Y., Khattak, A. & Rodríguez, D. Household excess travel and neighbourhood characteristics: associations and Trade-offs. Urban Stud. 48, 1235–1253 (2011).

Krizek, K. J. Residential relocation and changes in urban travel: does Neighborhood-Scale urban form matter?? J. Am. Plann. Assoc. 69, 265–281 (2003).

Li, X. et al. Effects of the built environment on travel distance in bus-oriented, medium-sized cities in China. J. Transp. Land. Use. 17, 423–455 (2024).

Muneer, T., Celik, A. N. & Caliskan, N. Sustainable transport solution for a medium-sized town in Turkey—A case study. Sustain. Cities Soc. 1, 29–37 (2011).

Páez, A. & Whalen, K. Enjoyment of commute: A comparison of different transportation modes. Transp. Res. Part. Policy Pract. 44, 537–549 (2010).

Dabbas, H. & Friedrich, B. Estimating traffic demand of different transportation modes using floating smartphone data. Transp. Transp. Sci. 0, 1–27 (2024).

Lee, S. Exploring associations between multimodality and built environment characteristics in the U.S. Sustainability 14, 6629 (2022).

Ding, C., Cao, X. & Næss, P. (eds) (Jason) Applying gradient boosting decision trees to examine non-linear effects of the built environment on driving distance in Oslo. Transp. Res. Part Policy Pract. 110, 107–117 (2018).

Lee, S., Jeon, J., Cho, K. & Im, J. Does intercity transportation accessibility matter?? Its effects on regional network centrality in South Korea. Land 14, 873 (2025).

Hamilton, B. W. & Röell, A. Wasteful commuting. J. Polit Econ. 90, 1035–1053 (1982).

Song, S. Does generalizing density functions better explain urban commuting? Some evidence from the Los Angeles region. Appl. Econ. Lett. 2, 148–150 (1995).

Alonso, W. Location and land use. Toward a general theory of land rent. Locat Land. Use Gen. Theory Land. Rent (1964).

Brueckner, J. K. The structure of urban equilibria: A unified treatment of the muth-mills model. in Handbook of Regional and Urban Economics 2 821–845 (Elsevier, (1987).

Liu, W. & Hou, Q. Excess commuting in transitional urban china: A case study of Guangzhou. Chin. Geogr. Sci. 26, 599–608 (2016).

O’Kelly, M. E. & Niedzielski, M. A. Efficient Spatial interaction: attainable reductions in metropolitan average trip length. J. Transp. Geogr. 16, 313–323 (2008).

Cheng, L. & Chen, C. Is school travel excessive? Empirical evidence from xi’an, China. J. Transp. Geogr. 117, 103895 (2024).

Park, C. & Chang, J. S. Spatial equity of excess commuting by transit in Seoul. Transp. Plan. Technol. 43, 101–112 (2020).

Aston, L., Currie, G., Delbosc, A., Kamruzzaman, M. & Teller, D. Exploring built environment impacts on transit use – an updated meta-analysis. Transp. Rev. 41, 73–96 (2021).

Park, K., Ewing, R., Scheer, B. C. & Tian, G. The impacts of built environment characteristics of rail station areas on household travel behavior. Cities 74, 277–283 (2018).

Lee, S., Yang, J., Cho, K. & Cho, D. The influence of transportation accessibility on traffic volumes in South korea: an extreme gradient boosting approach. Urban Sci. 7, 91 (2023).

Ewing, R. & Cervero, R. Travel and the built environment. J. Am. Plann. Assoc. 76, 265–294 (2010).

Handy, S. L., Boarnet, M. G., Ewing, R. & Killingsworth, R. E. How the built environment affects physical activity: views from urban planning. Am. J. Prev. Med. 23, 64–73 (2002).

Yang, J. Policy implications of excess commuting: examining the impacts of changes in US metropolitan Spatial structure. Urban Stud. 45, 391–405 (2008).

Cervero, R. & Kockelman, K. Travel demand and the 3Ds: density, diversity, and design. Transp. Res. Part. Transp. Environ. 2, 199–219 (1997).

Lee, S., Kim, J. & Cho, K. Temporal dynamics of public transportation ridership in Seoul before, during, and after COVID-19 from urban resilience perspective. Sci. Rep. 14, 8981 (2024).

Ha, J., Lee, S., Kim, J. H. & Hipp, J. R. Do employment centers matter? Consequences for commuting distance in the Los Angeles region, 2002–2019. Cities 145, 104669 (2024).

Zhang, D. & Wang, X. (eds) (Cara). Effects of Jobs–Residence Balance on Commuting Patterns: Differences in Employment Sectors and Urban Forms. Transp. Res. Rec. 2500, 80–92 (2019).

Hu, L., Yang, J., Yang, T., Tu, Y. & Zhu, J. Urban Spatial structure and travel in China. J. Plan. Lit. 35, 6–24 (2020).

Yi, C. & Ryu, J. Growth, decline and the challenges facing a policy-dependent and former-colonial city: gunsan, Korea. Cities 43, 37–47 (2015).

Chung, H. & Lee, J. Modern Industrial Heritage as Cultural Mediation in Urban Regeneration: A Case Study of Gunsan, Korea, and Taipei, Taiwan. Land 12, 792 (2023).

Abbiasov, T. et al. The 15-minute City quantified using human mobility data. Nat. Hum. Behav. 1–11. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41562-023-01770-y (2024).

Song, Y., Newman, G., Huang, X. & Ye, X. Factors influencing long-term City park visitations for mid-sized US cities: A big data study using smartphone user mobility. Sustain. Cities Soc. 80, 103815 (2022).

Ryan, R. L. The social landscape of planning: integrating social and perceptual research with Spatial planning information. Landsc. Urban Plan. 100, 361–363 (2011).

Lee, W. K., Sohn, S. Y. & Heo, J. Utilizing mobile phone-based floating population data to measure the Spatial accessibility to public transit. Appl. Geogr. 92, 123–130 (2018).

Steenbruggen, J., Borzacchiello, M. T., Nijkamp, P. & Scholten, H. Mobile phone data from GSM networks for traffic parameter and urban Spatial pattern assessment: a review of applications and opportunities. GeoJournal 78, 223–243 (2013).

Lee, S. Transportation Mode Choice Behavior in the Era of Autonomous Vehicles: the Application of Discrete Choice Modeling and Machine Learning (Portland State University, 2022).

Ewing, R. et al. Varying influences of the built environment on household travel in 15 diverse regions of the united States. Urban Stud. 52, 2330–2348 (2015).

Lee, S., Lee, S. & Putri, D. W. Multifaceted associations between built environments and POI visit patterns by trip purposes. Cities 161, 105903 (2025).

De Gruyter, C., Ma, L., Saghapour, T. & Dodson, J. How does the built environment affect transit use by train, Tram and bus? J. Transp. Land. Use. 13, 625–650 (2020).

Ashik, F. R., Sreezon, A. I. Z., Rahman, M. H., Zafri, N. M. & Labib, S. M. Built environment influences commute mode choice in a global South megacity context: insights from explainable machine learning approach. J. Transp. Geogr. 116, 103828 (2024).

Williams, B., Onsman, A. & Brown, T. Exploratory factor analysis: A Five-Step guide for novices. Australas J. Paramed. 8, 1–13 (2010).

Gaskin, C. J. & Happell, B. On exploratory factor analysis: A review of recent evidence, an assessment of current practice, and recommendations for future use. Int. J. Nurs. Stud. 51, 511–521 (2014).

Wang, S., Jiang, Z., Noland, R. B. & Mondschein, A. S. Attitudes towards privately-owned and shared autonomous vehicles. Transp. Res. Part. F Traffic Psychol. Behav. 72, 297–306 (2020).

Kang, C. D. The S + 5Ds: Spatial access to pedestrian environments and walking in Seoul. Korea Cities. 77, 130–141 (2018).

Cao, X. & Fan, Y. Exploring the influences of density on travel behavior using propensity score matching. Environ. Plan. B Plan. Des. 39, 459–470 (2012).

Abouelela, M., Durán-Rodas, D. & Antoniou, C. Do we all need shared E-scooters? An accessibility-centered Spatial equity evaluation approach. Transp. Res. Part. Policy Pract. 181, 103985 (2024).

Boarnet, M. G., Boarnet, A. P., Crane, E. M. G. & Crane, P. of U. and R. P. and R. of U. P. R. Travel by Design: The Influence of Urban Form on Travel Oxford University Press, (2001).

Austin, P. C. & Goel, V. Walraven, C. An introduction to multilevel regression models. Can. J. Public. Health. 92, 150–154 (2001). van.

Xu, H. Comparing Spatial and multilevel regression models for binary outcomes in neighborhood studies. Sociol. Methodol. 44, 229–272 (2014).

Subramanian, S., Jones, V. & Duncan, C. Multilevel methods for public health research. in Neighborhoods and Health (Oxford University Press, (2003).

Chang, Y. C., Chang, K. H. & Wu, G. J. Application of eXtreme gradient boosting trees in the construction of credit risk assessment models for financial institutions. Appl. Soft Comput. 73, 914–920 (2018).

Dong, W., Wang, N., Dong, Y. & Cao, J. Examining the nonlinear and interactive effects of built environment characteristics on travel satisfaction. J. Transp. Geogr. 123, 104111 (2025).

Liu, J., Wang, B. & Xiao, L. Non-linear associations between built environment and active travel for working and shopping: an extreme gradient boosting approach. J. Transp. Geogr. 92, 103034 (2021).

Wang, F. & Ross, C. L. Machine learning travel mode choices: comparing the performance of an extreme gradient boosting model with a multinomial logit model. Transp. Res. Rec. 2672, 35–45 (2018).

Lao, Y., Qi, F., Zhou, J. & Fang, X. A prediction method based on extreme gradient boosting tree model and its application. J. Phys. Conf. Ser. 1995, 012017 (2021).

Shams, M. Y. et al. Water quality prediction using machine learning models based on grid search method. Multimed Tools Appl. 83, 35307–35334 (2024).

Malakouti, S. M., Menhaj, M. B. & Suratgar, A. A. The usage of 10-fold cross-validation and grid search to enhance ML methods performance in solar farm power generation prediction. Clean. Eng. Technol. 15, 100664 (2023).

Refaeilzadeh, P., Tang, L. & Liu, H. Cross-Validation. in Encyclopedia of Database Systems (eds. Liu, L. & Özsu, M. T.) 1–7Springer New York, New York, NY, https://doi.org/10.1007/978-1-4899-7993-3_565-2 (2016).

Zhao, X. et al. Factors affecting traffic risks on Bridge sections of freeways based on partial dependence plots. Phys. Stat. Mech. Its Appl. 598, 127343 (2022).

Gao, K., Yang, Y., Gil, J. & Qu, X. Data-driven interpretation on interactive and nonlinear effects of the correlated built environment on shared mobility. J. Transp. Geogr. 110, 103604 (2023).

Ji, S. et al. Understanding cycling distance according to the prediction of the XGBoost and the interpretation of SHAP: A non-linear and interaction effect analysis. J. Transp. Geogr. 103, 103414 (2022).

Lee, S. Measuring the influence of transit accessibility on housing and transportation expenditures in the U.S.: A propensity score matching approach. Case Stud. Transp. Policy. 14, 101092 (2023).

Cheng, J., Hu, L., Zhang, J. & Lei, D. Understanding the synergistic effects of walking accessibility and the built environment on street vitality in High-Speed railway station areas. Sustainability 16, 5524 (2024).

Sardari, R., Hamidi, S. & Pouladi, R. Effects of traffic congestion on vehicle Miles traveled. Transp. Res. Rec. 2672, 92–102 (2018).

Frank, L., Bradley, M., Kavage, S., Chapman, J. & Lawton, T. K. Urban form, travel time, and cost relationships with tour complexity and mode choice. Transportation 35, 37–54 (2008).

Zhao, J., Wang, J. & Deng, W. Exploring bikesharing travel time and trip chain by gender and day of the week. Transp. Res. Part. C Emerg. Technol. 58, 251–264 (2015).

Corcoran, J., Li, T., Rohde, D. & Charles-Edwards, E. Mateo-Babiano, D. Spatio-temporal patterns of a public bicycle sharing program: the effect of weather and calendar events. J. Transp. Geogr. 41, 292–305 (2014).

Curl, A., Nelson, J. D. & Anable, J. Does accessibility planning address what matters? A review of current practice and practitioner perspectives. Res. Transp. Bus. Manag. 2, 3–11 (2011).

Deboosere, R., El-Geneidy, A. M. & Levinson, D. Accessibility-oriented development. J. Transp. Geogr. 70, 11–20 (2018).

Miller, H. J. & Goodchild, M. F. Data-driven geography. GeoJournal 80, 449–461 (2015).

Acknowledgements

This work is supported by the Korea Agency for Infrastructure Technology Advancement (KAIA) grant funded by the Ministry of Land, Infrastructure and Transport (Grant Number: RS-2022-00144012, Title: Creation of infrastructure for data life cycle and development of demonstration services to vitalize the land-transportation data industry).

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

S.L. K.C., and Y.J. conceived the research and revised the article; S.L. and K.C. designed the research experiment; S.L. wrote the article; K.C. and Y.J. supervised and reviewed the manuscript; S.L., K.C., and Y.J. collected, processed, and analyzed the data. All authors read and approved the final manuscript.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher’s note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if you modified the licensed material. You do not have permission under this licence to share adapted material derived from this article or parts of it. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Lee, S., Cho, K. & Jeon, Y. Travel efficiency in urban space: the role of built environment in shaping excess travel distance across transport modes. Sci Rep 15, 33372 (2025). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-17878-2

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-17878-2