Abstract

The latest developments in industrial control applications emphasize the need for incorporating intelligent algorithms for enhanced adaptability and performance. This study addresses the challenge of controlling a nonlinear, multivariable Boiler-Turbine System (BTS), which exhibits strong interactions, non-minimum phase behavior, and instability due to the integrating nature of water level dynamics. Traditional PID tuning methods often fail to manage such complexities effectively. In this work, a reinforcement learning (RL)-based approach is proposed using the Twin Delayed Deep Deterministic Policy Gradient (TD3) algorithm for adaptive PID tuning. Specifically, two novel multi-agent TD3 algorithms are introduced: Shared-Critic Multi-Agent (SCMA-TD3) and Individual-Critic Multi-Agent (ICMA-TD3). These architectures explore the use of shared versus independent critic networks, with varying actor-critic depths, to improve learning efficiency and control accuracy. The BTS control problem is meticulously modelled as an RL task, and the performance of SCMA-TD3, ICMA-TD3, and standard DDPG is compared for PID tuning under standard step signals and different disturbance scenarios. The findings highlight the capability of SCMA-TD3, ICMA-TD3 and DDPG algorithms to minimize oscillations and reduce settling time, while simultaneously enhancing efficiency and stability in BTS both qualitatively and quantitatively for the characteristics namely drum pressure, electric power and drum water level. The stability analysis of the BTS is conducted based on the computation of error metrics such as Integral Time Absolute Error (ITAE), Integral Square Error (ISE) and Integral Absolute Error (IAE). The ICMA-TD3 method demonstrates superior performance in control applications, achieving a 99.33% and 99.76% reduction in ITAE for electric power and drum water level control, respectively, compared to SCMA-TD3 and DDPG in BTS control. Additionally, ICMA-TD3 exhibits a 91.40% faster rise time and an 84.37% reduction in overshoot for electric power control. In the case of drum pressure regulation, while ICMA-TD3 achieves a 99.866% lower ITAE than SCMA-TD3, it experiences greater overshoot compared to SCMA-TD3. Furthermore, DDPG, despite its implementation, incurs a high cost function, along with excessive rise time and overshoot, making it the least effective approach for precise control applications. These results demonstrate that the proposed multi-agent TD3 frameworks offer a robust and adaptive solution for complex industrial control systems like BTS.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Boilers are vital to worldwide power generation, especially in coal or nuclear thermal power plants. Chemical production, district heating, and manufacturing sectors depend on boilers. Using a boiler that delivers steam to a single turbine, a boiler-turbine setup is able to transform the chemical energy of the fuel into mechanical energy, which is then converted into electrical energy. When it comes to the management of this system, the primary objective is to ascertain that the amount of electrical power generated is in accordance with the requirements of the electricity grid and that essential parameters such as drum pressure, electric power and drum water level are maintained within predetermined limits. The control of BTS must adhere to specific constraints regarding the rate at which the value of the fuel flow, steam flow, and drum water levels can be altered. To meet the constantly changing demand for electricity, the power plant sector must operate well in a wide range of temperature and humidity levels. Addressing the increasing demands for electricity and guaranteeing a reliable power supply for both industry and households poses a significant challenge. Process control analysis is a complex field with intricate and inherent concepts. The electricity industry relies largely on hydroelectric and thermal power sources. Thermal power plants are recognized for their efficiency and cost-effectiveness, which make them capable of meeting substantial demand reliably. Among these, BTS are commonly employed for generating electricity and are integral to diverse industries, both large- and small-scale. Such systems are valued for their dependability and adaptability with various fuel sources, which effectively generates power in line with rapidly increasing demands. A thermal power station generates energy by producing steam in boilers, with the core aim of a BTS, to maintain constant voltage and frequency to meet load demands. Achieving this goal involves optimizing thermal efficiency and implementing effective heat recovery from flue gases, which requires precise control of the plant model. BTS are typically nonlinear and operate as Multi-Input Multi-Output (MIMO) systems, presenting numerous control problems due to their nonlinearity and wide operational scope. Key control loops within BTS manage important aspects such as pressure and power, and the systems demonstrate non-minimum phase behavior along with shrink and swell effects. The need for control over the boiler is crucial to prevent disastrous occurrences. Bell and Astrom described a sophisticated third-order model for the BTS in 1987 using first-order principles, serving to devise control methods and understand the BTS’s dynamic behavior.

In real-time industrial applications, achieving a balance between fast setpoint tracking, system stability, and computational efficiency remains a significant challenge. Various conventional and hybrid control approaches have been explored in the literature to address these issues. In contrast, this research employs Reinforcement Learning (RL) techniques to optimize the PID controller in the Bell and Astrom BTS model. Specifically, this research applies advanced multi-agent Reinforcement Learning (RL) algorithms–namely, SCMA-TD3, ICMA-TD3, and DDPG to intelligently tune the parameters of the PID controller within the Bell and Astrom BTS model. These RL algorithms are selected for their ability to learn optimal control policies through continuous interaction with the environment, allowing for real-time adaptation to varying system dynamics. By using these techniques, the controller is capable of achieving superior control performance, characterized by evaluating the time-domain error metrics such as ITAE, IAE, and ISE. Furthermore, the use of multi-agent frameworks helps to distribute computational tasks, thus reducing overall computational overhead and improving the efficiency of the control system. The ultimate objective is to establish a robust, self-learning, and computationally efficient RL-based PID control strategy that enhances the dynamic response of the BTS.

The subsequent sections of the paper are outlined as follows. The literature survey section gives a detailed review on various controllers utilized for the BTS. A brief introduction of Non Linear (NL)-BTS and its linearization is provided in the Boiler turbine system section. The next section provides an in-depth description of Reinforcement Learning (RL) and discusses the role of RL agent as a supervisor to adjust the parameters of a Proportional-Integral-Derivative (PID) controller. The paper provides a detailed analysis of the Twin Delayed DDPG (TD3) and Deep Deterministic Policy Gradient (DDPG) techniques, as well as the algorithmic procedure used for tuning PID controllers. The details are found in the sections RL algorithm background and proposed RL-based BTS control. The effectiveness of the suggested algorithms, coupled with PID controller, is implemented for the BTS and the analysis is provided in results and discussions section. The analysis includes a discussion on the efficiency of adopting the recommended technique, as well as the computing time and complexity involved. The last section provides concluding remarks along with the potential for further work.

Literature survey

The literature survey section discusses the controllers used for BTS, starting from conventional controllers to advanced controllers and various ranges of intelligent controllers like bio-inspired, optimization-based, AI-based controllers, including RL-based PID controllers. Figure1 illustrates the extensive range of controllers that have been employed for the controlling, optimizing and monitoring the BTS over the last two decades.

Conventional controllers

Various conventional controllers like PID, Internal Model Controller (IMC)-PID, Gain scheduled (GS) PI controller, cascade controller, state feedback, feedforward controller, Linear Quadratic Regukator (LQR) and Linear Quadratic Gaussian (LQG) used for the BTS are reported in the literature and shown in Fig. 1. A partially decentralized IMC based PID controller is analysed for a quadruple tank system and BTS1. The simulation results show that this IMC controller works well for non-linear boiler system with interactions being reduced, zero tracking error and operates well in a wide operating range. An ideal decoupler for 3*3 MIMO BTS is examined in2. The controller modes can be changed manually without the loss of decoupling and addressing the servo problem. Decoupling, effective tuning, and constraint management are used in this multivariable PID design3 process to solve nonlinear BTS problems. Its performance matches industrial needs, making it a potential, widely applicable option. The control of the boiler drum level is analysed using cascaded PI controller4 along with feedback and feedforward control structures. The feedforward controller improves the performance of Tyreus Luyben and Zeigler Nichols tuning techniques. A 2-Degrees of Freedom (DOF) PI controller outperforms the 1-DOF controller in actuator limitations, according to the paper5. This gain scheduled 2-DOF PI controller has operating range constraints. A major change in the operating point leads to stauration of the drum level control input. The paper6 discusses BTS’s severe nonlinearities and ways of choosing the right operating range to reduce the effect due to non-linearity. A linear controller with loop-shaping H\(\infty\) and anti-windup compensation works well in this range. Two controllers7 are designed using feedback linearization and gain scheduling methods based on pole placement. The tracking objectives are compared for ‘near’, ‘far’ and ‘so far’ operating ranges. Feedback linearization approach has quick time response with more overshoot when compared to gain scheduled controller. The gain scheduled controller produces oscillation for the electric output signal which can be eliminated by reducing the speed of the tracking.

The authors in8 evaluated the system states using a linear observer, namely a Kalman filter augmented with an LQG controller. This estimation method is then validated with the performance of an LQR controller. The LQR controller aims to achieve a zero state or equilibrium state as the intended trajectory. The State Dependent Algebraic Riccatti Equation (SDRE)9 is capable of effectively tracking all operating points while taking into account the constraints of the control signals, without causing any disruptions to the system. The paper10 investigates robust decentralized control for a nonlinear drum boiler utilizing the Equivalent Subsystem Model Method (ESM) and traditional decoupler approaches. ESM is better in handling uncertainty and achieving better stability when compared to the other conventional approaches. The paper11 optimizes MIMO system control under disturbances with known dynamics but unknown initial conditions, concentrating on stability degree limitations. It proves the existence and uniqueness of a feedforward-feedback control law and shows its efficacy with a practical application. A sophisticated boiler-turbine control mechanism uses a model-based GS-PI controller12. This method compares to fixed gain PID controllers by changing gains to erroneous input, improving system performance under diverse scenarios. The GS-PI controller performs better in Integral Time Absolute Error (ITAE), Integral Square Error (ISE), and Bode stability and is complex when compared to fixed gain controllers, which makes installation and tuning difficult. This paper13 examines the LQR controller and the DMC for the BTS under unconstrained conditions. The LQR controller gives stable and optimized output under unconstrained conditions. DMC is based on future forecasting and developing efficient control even under constrained cases. Decentralized PID and decoupled PID controller for the BTS are discussed in14. In15 a detailed analysis of 5 controllers for the BTS is carried out. LQR+PI and Robust LQR controllers significantly enhance the stability and performance of BTS, achieving superior rise time, settling time, and overshoot reduction compared to PID, IMC-PID, and LQR controllers. Their effectiveness in set-point tracking and minimizing oscillations makes them ideal for efficient BTS control. From the analysis it is evident that decoupled PID is better than decentralized PID since the interactions are neglected by decoupling. This section of conventional controllers shows a variety of control solutions for BTS that handle operational issues such as nonlinearity, multivariable interactions, and operating range limits. The methods including gain scheduling, feedback linearization, and state-dependent methods, coupled with robust classic methods like PID and LQR controllers, have showed better performance in enhancing system stability, response, and robustness. To reduce interactions and maintain safe, efficient operations, decoupling and constraint management are essential. The methods like SDRE, ESM, and LQG controllers improve adaptability with performance under different operating situations. A variety of options emphasizes the need to choose control strategies that balance stability, performance, and complexity while meeting system requirements.

Advanced controllers

Tables 1 and 2 present a structured summary of various advanced controllers and control strategies applied for the BTS. This compilation provides a comparative understanding of different approaches, highlighting the effectiveness of various methods and their implications for BTS performance.

Advanced BTS control strategies like MPC, SMC, and GADRC, as well as data-driven methods like multimodel predictive control, improve disturbance, uncertainty, and input constraint handling. The methods improve tracking, robustness, and system stability. Implementation issues such as computing complexity, model correctness, and parameter adjustment persist.

Optimization-based controller and AI-based controllers

In Table 3 various studies on optimization-based controllers and AI-based controllers are summarized to illustrate methodologies, inferences and the performance effects in BTS.

The literature also records other advanced optimization algorithms like moth swarm optimization58 for tuning of fractional order fuzzy PID controller for the frequency regulation of microgrids and sunflower optimization59 for tuning fractional-order fuzzy PID controller for control of load frequency in an integrated hydrothermal system with hydrogen aqua equalizer-based fuel cells which resulted in 84.61% and 88.61% of improved ITAE and settling time respectively, over GA, Teaching learning based optimization, and conventional controllers. OPAL-RT real-time validation and sensitivity analysis demonstrate the method’s robustness and practicality under uncertain operating conditions. A Grasshopper optimization-tuned PDF plus (1 + PI) controller60 for Automatic Generation Control (AGC) in a thermal power system with Flexible AC Transmission system devices is proposed in this paper. The controller outperforms PI, PID, PIDF, GA, and PSO-based techniques in ITAE error and dynamic response. Real-time validation using OPAL-RT proves the approach’s robustness and practicality under various operational situations. This paper introduces an improved equilibrium optimization algorithm (i-EOA) to tune an F-TIDF-2 controller for load frequency regulation in freestanding microgrids with stochastic wind, solar, and load changes. The proposed solution reduces frequency deviations and improves dynamic stability better than PID, TID, and TIDF controllers. Imperialist competitive algorithm61-optimized cascade PDF(1+PI) controllers for load frequency management in AC multi-microgrid62 systems with RES, thermal, and storage units are proposed in this study. The controller outperformed PI, PID, and PIDF controllers in ITAE (up to 70.64%) and settling time under various uncertainties. The study does not address demand response variations or solar and wind energy stochasticity, limiting its practicality and requiring further investigation.

Optimization-based methods incorporated with controllers like LQR, PID tuning with PSO, and MPC variants improve control precision and efficiency while managing disturbances and restrictions. However, computational hurdles arise, especially in nonlinear BTS applications, where linearization and event-based algorithms balance performance and resource limits. The review shows a shift toward hybrid and AI-integrated control methods that balance optimization efficiency with intelligent adaptation to complicated BTS dynamics. Computational demand, stability verification, and industry accessibility are practical implementation challenges that need additional study.

Reinforcement learning

The research article63, investigates deep RL in process control, pushing AI beyond games. By constructing reward functions effectively, neural networks can learn industrial process control policies without predefined control rules, adjusting to the process environment over time. This method eliminates complex dynamic models and allows continuous on-line controller tuning, which are major enhancements over typical control algorithms. The approach’s limitations include the need for large computer resources for neural networks to learn and the reward function’s major impact on learning. Due to the novelty of deep RL in process control, such systems’ long-term stability and dependability in varied industrial contexts should be thoroughly assessed. An informative look at RL and process control sectors is available in research article64. RL’s ability to handle complicated stochastic systems and manage decision-making sequentially is useful for industrial applications with uncertain or time-varying variables. By using pre-calculated optimal solutions, RL can reduce online calculation times, which is important for systems that need computational speed. RL does not always outperform traditional MPC methods, especially when they are based on highly accurate models that guarantee globally optimal solutions. This research article65 proposes an enhanced deep deterministic actor-critic predictor to increase process control learning performance. The results show that the enhanced deep RL controller outperforms finely-tuned PID and MPC controllers, especially in nonlinear processes, and has the potential for practical application. Incorporating deep RL into practical process control settings can be difficult, ensuring consistent stability and meeting process constraints. The required substantial offline training and hyperparameter tuning limits applicability without additional technique refinement. RL in process control systems is thoroughly examined in66 where the authors developed suggestions to bridge the gap between RL theory and process control applications. These guidelines attempt to help practitioners better integrate RL into their control systems. The processing demands of RL algorithms limit them, especially in real-time situations that require fast decision-making. Although difficult, the research provides useful ideas for enhancing process control using RL.

RL-based PID

By controlling bioreactors, which are nonlinear and difficult to regulate with linear control algorithms, the research article67 makes major advancements. It presents RL-based control system that uses RL to solve difficult nonlinear control problems, making it more flexible and perhaps more successful. Due to bioprocess complexity and stochasticity, gathering enough and accurate data to train the RL algorithm is time-consuming and resource-intensive. The hyperparameters and RL model structure can affect the system’s performance, which limits the scalability of the suggested RL control technique for bigger or more variable bioreactor systems. The authors in68 have proposed a Continuous Stirred Tank Reactor (CSTR) system in a custom environment for economic optimization using RL. Three algorithms namely Proximal Policy Optimization (PPO), DDPG and TD3 algorithms are analysed and all the 3 algorithms effectively optimize the system. But TD3 algorithm outperforms the other two algorithms. In research article69, RL is used for industrial valve operations, with a focus on stiction as a substantial contribution to control inefficiencies. RL approaches the model-based policy search method Probabilistic Inference For Learning (PILCO) to reduce model bias and requires fewer trials than model-free methods by learning the probabilistic dynamics of the system and planning by incorporating model uncertainty. Non-linearity and high-frequency response rates make valve control systems difficult, requiring sophisticated and perhaps computationally expensive RL algorithms. An adaptive mechanism that allows the PID controller to modify its settings in real time to system dynamics is a fundamental contribution of the research article70. Linear and nonlinear unstable processes can be efficiently handled, by this approach which improves stability and control accuracy over typical PID controllers. Although computationally complex, the research provides useful ideas for enhancing process control using RL. An adaptive PI controller using RL method improves DC motor speed control in71. The study in72 RL-based PI tuning for a two-tank interaction system, where TD3 and DDPG agents optimize the controller using experimental data. PI controller tuned using TD3 algorithm reduces rising time, settling time, and error metrics faster and more reliably than DDPG algorithm. Real-time autonomous control parameter adjustment using an actor–critic RL framework and the TD3 is proposed in the research article. This adaptive technique lets the controller dynamically adjust to motor operating circumstances without system knowledge, optimizing performance and stability. The controller’s performance generalization across DC motor systems or other industrial applications needs further testing and validation. RL is used to tune model-free MIMO control for HVAC chillers in the research article73. Learning-based control tuners change MIMO decoupling PI controller coefficients in real-time. Due to its robustness on online information for adaptation, the methodology struggles with minimal data or initial deployment without past performance indicators. RL methods are complex, which increases the computational cost and the need for specialized knowledge to design and maintain adaptive control systems. A PID controller is tuned adaptively using the DDPG algorithm74. This method improves flexibility and stability when prior knowledge is insufficient, tackling a major difficulty in mechatronics and robotics. By adding a residual structure to the actor network, the vanishing gradient issue is addressed and allows for reward-based action in various stages. This solution reduces PID controller tracking error by 16-30% compared to conventional methods. Deep RL is used to adjust multiple Single Input Single Output (SISO) PID controllers in multivariable nonlinear systems75. The method outperforms typical PID tuning techniques in simulations of complex plant dynamics like multivariable non-minimum phase processes. One drawback in all the research work mentioned above is the need for considerable computational resources for deep RL agent training and a full plant simulation model, which can be difficult to build for complex systems. The paper76 proposes a data-driven adaptive-critic output regulation method for BTS which is a continuous linear time system with unknown dynamics and unmeasurable disturbances to stabilize and track set point optimally. This approach uses optimal feedback and feedforward control by solving regulator equation. This method is applicable for system with linear disturbance.

Research gap and problem definition

Although non-linear boiler control strategies have advanced, there is still a significant research gap in creating approaches that successfully strike a balance between two important goals: enhancing controller performance, especially in minimizing error metrics, and reducing computational costs. The practical deployment of intelligent control systems that can effectively manage the complex and dynamic behavior of BTS in modern power plants depends on resolving this issue. Effective BTS control requires minimizing error metrics such as ITAE, Integral Absolute Error (IAE) and ISE. Many advanced control strategies struggle to maintain robustness under real-world conditions, leading to trade-offs between fast setpoint tracking and stability, particularly in MIMO systems. Industrial BTS setups demand controllers that can operate in real-time, making it imperative to reduce computational complexity without compromising accuracy. RL aims to reduce computational overhead, but further refinement is needed to ensure their feasibility in large-scale power plants. Modern BTS control strategies like MPC25, SMC32, GADRC39, and data-driven multimodel predictive control are better at managing system disturbances, uncertainties, and input constraints. Setpoint tracking, system robustness, and operational stability improve greatly using these methods. These approaches have several drawbacks, including high computational needs, more model errors, and the necessity for online controller parameter tuning. Optimization-based control methods like LQR15, PSO-tuned PID48, and advanced MPC37 variants have been combined to improve control accuracy and efficiently handle dynamic constraints. In highly nonlinear BTS situations, higher computational time makes the execution difficult in real-time. To have a balance between the performance and computational feasibility, system linearization and event-triggered control techniques are used. Recent advancements in the control algorithms include hybrid control frameworks and AI-driven solutions that combine classical control qualities with machine learning’s capability and adaptability. These developing strategies show promise in controlling the BTS’s complicated multivariable interactions.

BTS has complex dynamics along with non-minimum phase behavior of the electric power and the shrink swell effect due to the integrating nature of the drum water level. The BTS is 3*3 MIMO system with interactions among each variable with high non linearity. The highly non linear system is linearized using Taylor series approximation. PID controller is an effective controller over the decades but tuning PID controller for a MIMO process is quite challenging. Therefore, RL algorithms such as Shared Critic Multi-Agent (SCMA)-TD3, Individual Critic Multi-Agent (ICMA)-TD3 and DDPG are introduced as multi-agents to fine tune the PID controller. RL can significantly upgrade the functionality of PID controllers in industrial settings when compared to classic tuning techniques. Figure 2 gives the block diagram of RL. This approach allows the controllers to adjust in real-time to system shifts and devise superior control strategies through direct interaction with the environment, augmenting performance metrics including response time, stability, capabilities of dealing with disturbances, and overall operational proficiency. RL-based PID controller is analyzed by the detailed analysis of various RL algorithms by measuring the error metrics such as ITAE, IAE and ISE to ensure the robustness of the proposed methods.

Contributions of this research

-

In this work, RL algorithms are used for fine-tuning the PID controller gains in the Bell and Astrom BTS plant model.

-

Two novel multi-agent TD3 variants – SCMA-TD3 (shared critic) and ICMA-TD3 (individual critic) are introduced in this research to explore critic sharing and actor-critic depth to enhance learning efficiency and control accuracy in BTS.

-

The performance of SCMA-TD3, ICMA-TD3, and standard DDPG is compared with different disturbance scenarios, and the stability is assessed on the BTS characteristics - electric power, drum pressure and drum water level.

-

RL-based PID controller parameter estimation evaluates the RL-driven boiler system’s performance in terms of key performance metrics like ITAE, IAE, ISE, and computational time.

-

The results are evaluated and validated under different input conditions and disturbances, reflecting the robustness and efficacy of the RL-based PID controller for the BTS model.

Boiler turbine system

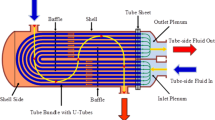

K. J. Astrom and R. D. Bell created a third-order non-linear dynamic model for boilers using fundamental principles, accurately simulating the plant’s behaviour. Bell and Astrom boiler is a natural circulation water tube boiler, in which chemical energy (coal) is converted into heat energy, then heat energy (steam) is converted into mechanical energy (turbine shaft movement), and finally mechanical energy is converted into electrical energy. BTS continues to be a significant contributor to global electricity production and energy-intensive industrial processes. The major applications of boiler in the field of control engineering are controller design and tuning, control system validation, control system training and education, optimization and energy efficiency, fault detection and diagnosis, etc. The futuristic applications of the BTS involve energy efficiency, renewable energy integration and sustainability. Control of boilers can involve multiple complexities due to the dynamics and nature of the boiler model. The Bell and Astrom boiler is a simplified representation of the BTS that captures its dynamic behavior. The complexities that are associated with it are non-linear dynamics, constraints due to control with multivariable interactions, and the shrink-swell effect due to non-minimum phase behaviour.

The mathematical model of non-linear BTS

The model for the BTS used in this work is shown in Fig. 3 and the governing equations of the systems are as follows:

where \(x_{1\text {-BTS}},\ y_{1\text {-BTS}}(t)\) denote the drum pressure of BTS (kg/cm\(^2\)), \(x_{2\text {-BTS}},\ y_{2\text {-BTS}}(t)\) denote the electric power of BTS (MW), \(x_{3\text {-BTS}}\) is the fluid density of BTS (kg/m\(^3\)), \(\dot{x}_{1\text {-BTS}}(t),\ \dot{x}_{2\text {-BTS}}(t),\ \dot{x}_{3\text {-BTS}}(t)\) are the state derivatives of \(x_{1\text {-BTS}},\ x_{2\text {-BTS}},\ x_{3\text {-BTS}}\), \(u_{1\text {-BTS}}\) is the control valve position (normalized) controlling mass flow rate of fuel, \(u_{2\text {-BTS}}\) is the control valve position controlling mass flow rate of steam to the turbine, \(u_{3\text {-BTS}}\) is the control valve position controlling mass flow rate of feedwater to the drum, \(y_{3\text {-BTS}}(t)\) is the drum water level deviation (m), \(q_{\text {ev(BTS)}}\) is the evaporation rate, and \(s_q(\text {BTS})\) is the steam quality.

The operating points (various load conditions) for the BTS are shown in Table 4. The nominal values of \(x_{1\text {-BTS}}, x_{3\text {-BTS}}\) and the controlled inputs \(u_{1\text {-BTS}}, u_{2\text {-BTS}}, u_{3\text {-BTS}}\) are determined based on the load demand \(x_{2\text {-BTS}}\)3.

The Bell and Astrom boiler model, which is initially non-linear represented by Eqs. (1)-(8), is linearized using a Taylor series approximation around its 4\(^{\text {th}}\) operating point. The non-linear model is converted into linear MIMO transfer function model as given in Eq (9).

RL algorithm: background

Reward-based RL has become a useful paradigm for addressing complicated control issues by allowing agents to learn optimal actions via environmental rewards. Trial-and-error learning reinforces environmental state-based actions in RL, which is judged by cumulative rewards77. Learning an appropriate state-action mapping maximizes the cumulative discounted reward for the agent. Bellman’s principle of optimality ensures that the agent’s policy evolves to maximize outcomes from any state, independent of initial conditions. RL agents learn via experience rather than repetitive instances, adjusting their methods depending on past actions. Due to their simplicity and efficacy, PID controllers are commonly employed for control systems. In complicated or nonlinear systems, PID controllers require accurate parameter adjustment. RL-based techniques like TD3 and DDPG improve PID controllers by using their capacity to learn optimal control policies in dynamic contexts. The agent in actor-critic RL algorithms TD3 and DDPG has two main components:

-

The Actor Network identifies the best action (a) based on the current state (s’).

-

Critic Network estimates state quality by estimating the expected cumulative discounted reward.

These algorithms directly output actions from the actor network, which can reflect physical system control signals like PID parameters. These activities are evaluated by the critic network by estimating future rewards. At each time step, the agent observes the current state (s’), selects an action (a) and receives a reward (r). The environment changes to the next state and the agent refines its policy iteratively. This methodology integrates RL algorithms like TD3 and DDPG with PID control to provide a strong foundation for adaptive and optimal control of complex systems where typical PID tuning methods may fail. This work applies RL-based approaches to tuning PID controllers, showing its potential to solve dynamic and nonlinear problems.

DDPG: exploration and exploitation

Adaptive tuning via DDPG is particularly advantageous in complex, model-free scenarios where classical methods fail to capture the dynamism inherent to the system. In the pursuit of enhancing PID controller adaptability and stability, the integration of DDPG, an RL algorithm, presents a promising approach. DDPG, suited for continuous action spaces, allows for the simultaneous learning of a policy and a Q-function. Actor and critic networks coordinate in a stepwise manner in the DDPG algorithm. In the DDPG algorithm, the actor network proposes an action based on the current state, while the critic network estimates the Q-value. The error between the predicted Q-value and the target Q-value is minimized by the critic learning. The actor updates its policy once the critic evaluates the actor’s actions. By applying Actor-Critic methods, DDPG fine-tunes the PID parameters \(k_p\) (Proportional gain), \(k_i\) (Integral gain), \(k_d\) (Derivative gain) through a policy network (Actor) (Eq. (15)) that suggests control actions and a Q-value network (Critic) (Eq.(14)) that evaluates these actions. Through trial and error, the algorithm optimizes the PID parameters to reduce tracking error and maintain stability without dependency on predefined models. In the context of DDPG for adjusting PID controller parameters, exploration is crucial, especially during the initial stages of learning. It prevents the algorithm from prematurely converging to suboptimal policies by encouraging the evaluation of a wider range of PID parameter settings. This is typically achieved by adding a noise process, such as Ornstein-Uhlenbeck or Gaussian noise, to the actor policy’s output. Such stochasticity in action selection allows the agent to discover and learn from various operational consequences, which is vital for identifying the optimal PID settings across diverse and uncertain system dynamics. On the other hand, exploitation is about using the best strategy that the agent has learned so far. As the agent gradually learns the optimal actions, the balance shifts towards exploitation, enhancing the accumulated knowledge encapsulated in the actor network to select the most effective actions. Ultimately, the aim is to diminish the exploration noise over time, stabilizing the selection of actions and converging towards an optimal policy that adaptively tunes the PID controller, thus reflecting a learned balance between exploration and exploitation. DDPG effectively tracks continuous action spaces and enables model-free control of complicated, nonlinear systems. Deterministic policy allows repeatable control actions. Sensitivity to hyperparameters is a major issue with DDPG and it can also converge slowly and be unstable in high-dimensional situations. The number of layers in the actor and critic network, activation function used for this algorithm is shown in Fig. 4. The pseudocode for DDPG algorithm65 is given below.

Pseudocode of DDPG

Input and initialization:

Input: Initial policy parameter \(\theta\).

Initially Q-function parameters \(\phi\).

Replay buffer D holds past experiences \((s, a, r, s', d)\).

Step 1: Initialize target parameters:

Set target (targ) parameters to match primary parameters:

Step 2: Repeat steps 3 to 14 until convergence or max episodes reached

Step 3: Check current state and choose action

Check the current state \(s'\).

Choose an action a using policy \(\mu _{\theta }(s)\) and exploration noise \(\epsilon\)

where \(\epsilon\) is Gaussian noise.

Step 4: Execute action

Execute a in the environment.

Step 5: Observe transition

Record the next state \(s'\), reward r, and terminal flag D.

Step 6: Store experience

Add experience tuple \((s, a, r, s', d)\) to replay buffer D.

Step 7: Reset environment if \(s'\) is terminal.

Step 8: Check update condition

Follow these steps if it’s time to update.

Step 9: Set the number of updates

Step 10: Randomly sample a batch of transitions

Step 11: Compute the goal value for each transition

where \(\gamma\) is the discount factor.

Step 12: Update the Q-function One step of gradient descent using

Step 13: Update policy using

Step 14: Soft update of target networks

where \(\rho\) regulates the update rate.

ICMA-TD3 and SCMA-TD3: exploration and exploitation

In this study, the application of the TD3 algorithm for the adaptive tuning of a PID controller is explored. The Twin Delayed Deep Deterministic Policy Gradient-TD3 algorithm, renowned for handling the overestimation of Q-values inherent in its predecessor DDPG, is utilized to optimize the PID parameters dynamically. TD3 uses twin critic networks and delayed policy updates to stabilize and reduce reinforcement learning overestimation. By incorporating a pair of critic networks to estimate the Q-function in Eq. (23) and employing delayed policy updates along with target policy smoothing mentioned in Eq. (25) and Eq. (26), the TD3 algorithm ensures a robust and stable adaptation of the PID controller to varying conditions. As a result, the PID controller continuously refines its gains based on the feedback received from the controlled system, aiming to achieve and maintain the desired performance without requiring apriori knowledge about the system dynamics. In the context of TD3 algorithm applied to PID controller tuning, exploration refers to the process by which the agent investigates various PID parameters to discover how they affect the performance of the controlled system. Exploitation, on the other hand, involves using the knowledge gained from exploration to choose the PID parameters predicted to offer the best performance. TD3 achieves a balance between exploration and exploitation by using a noise process for the policy’s action output during exploration, ensuring a sufficient variety of PID parameters are tested, and by subsequently exploiting the learned policy to fine-tune the parameters for optimal performance. Two variations of TD3 algorithm are introduced as SCMA-TD3 and ICMA-TD3 algorithm. The underlying logic behind TD3 remains the same, with only a difference in the network structure in the critic. In ICMA-TD3 two individual critics are used for the PID parameters with a shallow network to avoid the complexity and computational cost. In SCMA-TD3, shared critic with deeper structures and activation functions are used for PID parameter tuning. The individual critic structures in the network structure allows the ICMA-TD3 to capture better dynamics and enhance the PID parameters identified for the complex BTS. The number of layers in the actor and critic network, activation function used for these two algorithm is shown in Fig. 4 which shows the difference between the architectures. The pseudocode for TD3 algorithm is given below65.

Pseudocode of TD3

Step 1: Input and initialization:

Input: Initial policy parameter \(\theta\).

Initially Q-function parameters \(\phi_1, \phi_2\).

Replay buffer D holds past experiences \((s, a, r, s', d)\).

Step 2: Initialize target parameters

Set target parameters to match main parameters:

Step 3: Repeat steps 4 to 16 until convergence.

Step 4: Check state and choose Action

Check the current state.

Choose an action a using policy \(\mu _{\theta }(s)\) and exploration noise \(\epsilon\)

Step 5: Execute action

Perform action a in the environment.

Step 6: Observe transition

Record the next state \(s'\), reward r, and terminal flag D.

Step 7: Store experience

Add experience tuple \((s, a, r, s', d)\) to replay buffer D.

Step 8: Reset environment

If \(s'\) is terminal, reset the environment.

Step 9: Check update condition

If a predetermined frequency indicates an update, follow the instructions.

Step 10: Perform updates for a predefined number of iterations (j)

Step 11: Sample a batch of transitions

Step 12: Compute target action for each transition

Step 13: Compute target Vvlue

where \(\gamma\) is the discount factor.

Step 14: Update Q-functions

Perform one step of gradient descent on the Q-function loss:

Step 15: Update policy

Step 16: Soft Update target networks

where \(\rho\) regulates the update rate.

A shared critic network structure is used for all agents in SCMA-TD3 which centralizes the value estimation. The shared critic network has more layers than the TD3 critic network. This enhanced depth allows the shared network to record and process more complicated inter-agent interactions and shared environmental dynamics, which is necessary for agent coordination. SCMA-TD3 lowers computing overhead and assures consistent agent action evaluation based on a single environmental perspective by maintaining a single critic network. ICMA-TD3 assigns each agent a critic network, decentralizing the process. The SCMA-TD3 shared critic has more layers than these individual critic networks. This architecture lets ICMA-TD3 focus on each agent’s localized learning and evaluate behaviors depending on their environment interaction. This decentralized structure increases computing complexity due to agent-specific critic networks, but it allows greater flexibility and adaptability to unique agent dynamics. Both implementations use the TD3 algorithm’s strengths–delayed policy updates, target smoothing, and noise regularization–but differ in critic network architecture. SCMA-TD3’s deeper shared critic stresses coordination and inter-agent robustness, while ICMA-TD3’s individual critic networks highlight autonomous learning and network simplicity. In multi-agent RL settings, shared and individual critic designs affect performance, scalability, and computational efficiency, and this methodological comparison illuminates the trade-offs between these characteristics.

Proposed RL-based BTS control

The analysis of RL-based control strategy focuses on complex multivariable BTS with three inputs and three outputs. The main goal is to maximize the PID gains in order to achieve efficient regulation of the process. The configuration of the RL is designed to replicate real-life industrial situations where processes display complex interactions and interdependencies among their variables. The PID controllers are assigned to BTS variables, which are characterized by their proportional (P), integral (I), and derivative (D) gain characteristics and are to be tuned using the RL algorithms. The control scheme of the BTS using RL-based PID is shown in Fig. 5.

The difficulty lies in coordinating the tuning process across several controllers to guarantee the overall stability and performance of the system. To carry out the tuning procedure, three separate RL agents are utilized, with each agent assigned to a specific PID controller. Each agent is provided with a collection of state observations, including error measurements and system performance indices relevant to its respective PID controller. The agents aim to acquire policies that minimize a predetermined LQG cost function and desired performance requirements through the adjustment of their individual PID gains. Despite the emergence of advanced control methods like fuzzy logic, adaptive mechanisms, and model-based techniques, PID controllers remain dominant because of their simple design and demonstrated ability to provide reliable performance in many operating circumstances. Metrics for evaluating the performance is determined by the effectiveness of the PID controllers and it is assessed using various metrics such as the rate at which they approach the desired value, the extent to which they exceed the desired value and the error that persists in the steady state. These measurements offer a thorough understanding of the effectiveness of the SCMA-TD3, ICMA-TD3 and DDPG algorithms in acquiring suitable PID settings in a multivariable configuration.

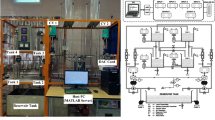

RL framework

The Simulink configuration used for both training and evaluating the RL controller is shown in Fig. 6. The multi-agent structure receives feedback from the environment through the observations vector.

Environment design

To effectively teach an agent to follow control signal trajectories, several design elements must be considered when creating the environment. They can be categorized as agent-related or environment-related. Agent-related factors include the composition of the observations vector and reward strategy. Environment-related elements include training techniques, signals, initial conditions, and criteria for terminating episodes.

Training strategy

The RL agents are trained to precisely follow the benchmark trajectory with random quantities of constant signals. The agent is further tasked with acquiring the ability to commence from a randomly initialized value. This combination constitutes an effective and versatile training approach to instruct the agent in tracking control signal trajectories. The MV-BTS is considered for this application and three agents are created for RL algorithm which captures the dynamics and interactions of the system perfectly to follow the benchmark trajectory. So each agent is responsible for each loop along with the interactions present in this highly interacting BTS system.

Observation vector and rewards strategy

The observation vector

where e = error is utilized in the training of RL controllers to the PID parameters. The reward function for the RL agent is the negative of the LQG cost function, which is given by the equation,

The RL agent maximizes this reward, thus minimizing the LQG cost. LQG’s quadratic cost functions penalize large mistakes more than smaller ones. This reduces control effort and enhances stability. For linear systems with Gaussian noise, LQG control gives a theoretically elegant solution that is optimum for the quadratic cost function. Although linear cost functions are straightforward for linear systems, they sometimes lack the desired features of quadratic cost functions. Its quadratic cost makes LQG control a potential foundation for reliable, efficient, and customizable linear system control.

Actor critic network

The structure of the actor-critic network for DDPG, SCMA-TD3 and ICMA-TD3 algorithm is shown in Figs. 7 and 8 respectively.

Results and discussions

A thorough examination of the closed-loop performance and error metrics provides insights into the efficacy of PID controller for different RL algorithms in managing the drum pressure, electric power and the drum water level inside the multivariable BTS. The RL technique helps in tuning the PID controller to get the gain value. It is important to note that these sophisticated algorithms have their own pros and cons, but ultimately aims to maximize the BTS performance and stability of the system.

PID controller parameters

PID gain values are calculated by the RL agent for the given input for 10,000 episodes. The calculated gains are presented in Table 5.

Error metrics

The SCMA-TD3, ICMA-TD3 and DDPG-RL algorithms for servo performance are analysed using errors metrics. All three algorithms are evaluated for error metrics like ITAE, IAE, and ISE when the BTS set point is introduced. The results are provided in Tables 6, 7 and 8.

-

The ITAE metric prioritizes errors that persist over time. ITAE can measure how well a system recovers from disturbances or set-point changes in stability analysis.

$$\begin{aligned} ITAE = \int t |e(t)| \, dt \end{aligned}$$(30) -

ISE measures overall error by squaring instantaneous error values of each time point and integrating them over time. A controller that reduces overall deviation from the set point has a lower ISE value, suggesting a more stable system.

$$\begin{aligned} ISE = \int e^2(t) \, dt \end{aligned}$$(31) -

IAE is calculated by adding absolute control error levels over time. A control system with a reduced IAE reduces error magnitude, which is vital to stability.

$$\begin{aligned} IAE = \int |e(t)| \, dt \end{aligned}$$(32)

Experimental analysis and discussions

The simulations are carried out for 10,000 episodes and the results obtained using the three RL algorithms namely DDPG, SCMA-TD3 and ICMA-TD3 are compared The system receives a continuous reference input without external disruptions. The controller’s steady-state responses and reference input tracking are examined. PID controller tuning is the focus of this study, which uses SCMA-TD3, ICMA-TD3, and DDPG RL algorithms. Three frequently used error metrics such as ITAE, IAE, and ISE are chosen to systematically evaluate their performance. These measurements show the controller’s transient responsiveness and steady-state performance. Figure 9 shows the overall approach implemented in this work to analyse the performance of BTS. Experiments are conducted on the three RL-based algorithms for three different input and disturbance scenarios as defined below, and the closed-loop responses are obtained.

-

Case 1: System response to constant reference input

-

Case 2: System response to time-varying reference input

-

Case 3: System response to constant reference input with disturbances at the plant input

Case 1: System response to constant reference input

Figure 10 shows the closed-loop response of the drum pressure for a constant reference input. ICMA-TD3 has the fastest settling time among the examined algorithms, SCMA-TD3 and DDPG. Although SCMA-TD3 produces the appropriate output, its oscillations compromise its stability. However, the DDPG algorithm tracks the setpoint with minimal oscillations, balancing stability and robustness. Table 6 gives the performance metrics for drum pressure. Figure 11 shows the closed-loop response of electric power for a constant reference input. Compared to SCMA-TD3, ICMA-TD3 and DDPG perform better for electric power control. SCMA-TD3 manages the overshoot, which is under tolerable level. This extensive assessment shows that ICMA-TD3 and DDPG achieve robust electric power regulation. Table 7 presents the performance measures for BTS electric power. Figure 12 shows the closed-loop response of drum water level for a constant reference input. The SCMA-TD3 algorithm has a peak overshoot, which may reduce its robustness in control applications. However, ICMA-TD3 and DDPG achieve excellent setpoint tracking with minimum variation and no overshoot, ensuring stability and robustness. This investigation shows that ICMA-TD3 and DDPG provide robust and precise drum water level management. Table 8 gives the performance metrics for drum water level.

Interms of drum pressure, ICMA-TD3 has the least ITAE (8.3848) compared to SCMA-TD3 (6.2780E+03) and DDPG (1.1335E+03), indicating better transient performance. ICMA-TD3 has a faster rise time (0.211 sec) than SCMA-TD3 (2.0 sec) and DDPG (1.886 s) and decreased overshoot of 13.907%. Least settling time is recorded by ICMA-TD3 of 1.74 sec. DDPG’s oscillatory behavior, huge overshoot (54.84%), and widened rise time make it a less suitable control algorithm to control drum pressure.

Considering electric power, ICMA-TD3 has the lowest ITAE (0.0327) and IAE (0.0219), surpassing SCMA-TD3 (4.8886, 0.2899) and DDPG (1.9439, 0.1524), thus reducing tracking errors respectively. ICMA-TD3 has the fastest rise time (0.0245 sec) and the lowest overshoot (1.2446 %) demonstrating stability of the algorithm. ICMA-TD3 algorithm records the least settling time of 0.040 sec when compared to the other two algorithms in tuning the PID controller. SCMA-TD3 and DDPG have larger error values and slower response times, showing that ICMA-TD3 is the better controller for precise electric power regulation.

ICMA-TD3 stabilizes drum water level best with the lowest ITAE (50.8423), IAE (4.8946), and ISE (1.6797). ICMA-TD3 has the fastest rise time (4.223 sec) and lowest overshoot (25.011 %) ensuring smoother operation. SCMA-TD3 had increased ITAE (2.1587E+04), overshoot (182.941), and peak response (1.730), indicating less robustness compared to the other algorithms. The settling time is 32.233 sec by the ICMA-TD3 algorithm, which is the least recorded settling time when compared to other algorithms. DDPG’s high ITAE (2.1361E+03) and extended rise time (12.139 sec) make it less effective and less robust than ICMA-TD3 for drum water level management.

Overall, it can be observed that ICMA-TD3 is the most robust controller for precise and stable performance, with the least error, less rise time, settling time and minimal oscillations across all control variables. SCMA-TD3 gives better control but with a significant amount of overshoot and oscillations. Although DDPG has a high cost function, its lengthy response times and overshoot make it unsuitable for real-time control applications. Based on the obtained results, ICMA-TD3 emerges as the effective method for optimizing the BTS. Figure 13 gives the comparison of error metrics for proposed algorithms using 100% stacked column plot. SCMA-TD3 suffers with long-term accumulated error due to significant contribution of ITAE. ICMA-TD3 achieves a more balanced performance across error metrics, particularly in electric power regulation. Higher contributions to IAE and ITAE by DDPG indicate either possible less robustness or more variations in control performance. Drum pressure and drum water level has more ITAE implying that controllers need improved adaptation mechanisms to reduce error over time.

Case 2: System response to time-varying reference input

Model-based controllers like IMC-PID controller cannot handle disturbance when sudden changes occur instantly. RL is used to train agents for random input, so even if unknown disturbances occur, they can handle without any prior knowledge, since they have learned the complete dynamics of the BTS. SCMA-TD3, ICMA-TD3, and DDPG algorithms are evaluated using ITAE, IAE, and ISE across three process variables for Case 2. The closed-loop responses of RL-PID for Case 2 are shown in Figs. 14, 15, 16. The error metrics are presented in Tables 9, 10 and 11 respectively. Case 2 scenario can occur when there is a need for varying the control signals or the control signals may be distorted due to sensor fault or any other reasons. ICMA-TD3 outperformed SCMA-TD3 and DDPG in drum pressure control with low ITAE (2.33), IAE (12.18), and ISE (13.10). In electric power, ICMA-TD3 again demonstrated excellent control with low IAE (0.50) and ISE (0.38), while SCMA-TD3 has greater ITAE (1.06E+04), indicating slower response, and DDPG has considerable tracking errors and instability. ICMA-TD3 has shown reduced IAE and ISE error for the control of drum water level, but its ITAE (1.77E+03) is moderately greater due to drum water level control’s dynamic complexity. ICMA-TD3 is the most robust controller tested, with higher accuracy and convergence. However, DDPG’s significant error metrics in all situations show its limits in addressing multivariable nonlinear interactions with variable set point tracking. ICMA-TD3 tracked all three variables of BTS with good performance and has less error margins when compared to the other two outputs.

Case 3: System response to constant reference input with disturbances at the plant input

ITAE, IAE, and ISE metrics are used for assessing the controller performance for drum pressure, electric power, and drum water level under plant input disturbance conditions for the third case. The closed loop responses of RL-PID for Case 3 are shown in Figs. 17, 18, 19. The error metrics are presented in Tables 12, 13 and 14 respectively. In Case 3, external disturbances, which are very common in industrial settings and real-world systems, are introduced to the plant input. ICMA-TD3 has outperformed SCMA-TD3 and DDPG, which has less tracking errors, for drum pressure with ITAE = 3.82E+04, IAE = 62.34, and ISE = 358.13. DDPG has a lower ISE (96.91) than SCMA-TD3 (817.99), but its IAE and ITAE are much higher than ICMA-TD3, indicating less control. In electric power tracking, ICMA-TD3 demonstrated better IAE (2.77) and comparable ISE (0.80) than SCMA-TD3, indicating improved disturbance rejection. DDPG again performed poorly with the highest ITAE (3.00E+03), IAE (10.11), and ISE (2.60), indicating its susceptibility to disturbances. ICMA-TD3 performed better than SCMA-TD3 and DDPG in drum water level with low ITAE (2.26E+04), IAE (37.11), and ISE (65.21). DDPG’s lower ISE (99.47) than SCMA-TD3 (266.44), but higher IAE value indicated delayed settling and weaker control. ICMA-TD3 is the best algorithm for real-time industrial deployment in complicated multivariable systems and regularly shows robust and dependable control under disturbances.

If sudden unknown disturbances are introduced to the plant, all the three RL algorithms are capable of handling these disturbances, with minor impact on the set point tracking with tolerable levels of oscillations and overshoot. Thus, the overall advantage of using RL for tuning PID is reduced settling time, less overshoot and less oscillations.

Given its capacity to acquire knowledge from the environment and its ability for autonomous decision-making, RL is undoubtedly advantageous for use in the field of process control. Due to the inherent non-linearity of many industrial processes, RL can provide an advantage in fine-tuning the controller’s parameters. The proposed SCMA-TD3, ICMA-TD3 and DDPG RL-PID controller in this study demonstrates effective response in controlling linear multivariable BTS. During the training phase, the RL agent is exposed to the complete spectrum of the process and its behavior. The RL agent acquires the ability to forecast the PID tuning settings for a given operating point, depending on the condition of achieving the highest reward. During the validation step, the RL agent selects suitable PID tuning settings for the process depending on its operating conditions. Nevertheless, the controller tuning parameters are continuously forecasted by the RL agent, taking into account the current process operating conditions. Once tuned, the RL-PID controller effectively handles variations in the setpoint as well as external disturbances. By using automated exploration and learning from interactions with the environment, the controller continually improves its performance to achieve the desired system response.

Implementing TD3 and DDPG has resulted in decreased oscillations and settling time, along with enhanced system efficiency and stability in comparison to conventional PID tuning techniques. RL algorithm captures the dynamics of the system and then tunes the PID controller based on the rewards function, which makes it more robust and stable. Handling system instabilities is the major challenge to be tackled when integrating RL-based approach for tuning the PID controller parameters. The SCMA-TD3, ICMA-TD3 and DDPG algorithms use the reward obtained by the agent as an evaluation criterion to decide the optimal tuning parameters of the PID controller. The evaluation criteria used here is LQG cost function. It is well known that the RL agent attempts to attain maximum rewards. But LQG cost function is a standard and well accepted performance metric. Selecting and fine tuning the cost function according to the application is a tedious and time consuming task. It is thus observed that learning progress stagnates as the agent found a sub optimal solution that leads to poor tracking performance. The choice of learning rate can significantly impact the performance. If the learning rate is too high the algorithm can skip the optimal solution. If the learning rate is too small, we will need too many iterations and it takes more time to converge. Deciding the optimal learning rate is challenging and time consuming task.

Computational cost

Table 15 shows the computational time needed by the RL agent to compute PID gains for a given input on two different system configurations. The first test is done with a system in MATLAB environment on 64-bit operating system (CPU 1), an x64-based processor with 16 GB RAM and 3.4 GHz speed. The second test is done with a system in MATLAB environment on 64-bit operating system (CPU 2), an x64-based processor with 16 GB RAM and 2.5 GHz speed. To assure accuracy and consistency, the computing procedure is done for 10,000 episodes on the three algorithms. The results show that the RL agent determines PID gains in less time, demonstrating the computational efficiency of the suggested approach. Real-time applications need rapid response from trustworthy control decisions to preserve system performance and stability. From Table 15 for CPU 1, it is evident that ICMA-TD3 (0.5 sec) takes less time to compute than SCMA-TD3 (0.6 sec) and DDPG (0.7 sec) and CPU 2 takes 1.27 sec, 0.62 sec and 0.96 sec respectively. Hence it is to be noted that adding the proposed RL agent to the existing conventional PID controller will lead to a very small overhead in terms of computational complexity. The episode reward vs iteration plot is shown in Figs. 20 - 22 along with the computational cost for CPU 2 configuration.

Conclusion

This research investigates an adaptive method to tune PID controller using RL algorithm for a multivariable BTS. The system is complex, with non-minimum phase behavior exhibiting shrink and swell effects and the integrating nature of the drum water level. Industry relies on PID controllers due to its simplicity, reliability, and durability, even as more advanced control methods emerge. Industry favors PID controllers because they work with many control loop designs, from simple SISO to complicated MIMO. A wide range of hardware and software supports PID controllers, making them easy to integrate with existing technologies. These controllers are well-suited for real-time applications with limited computational resources, as they are less computationally demanding compared to more complex control strategies. Despite non-linearity and system disturbances, PID controllers can be improved with adaptive and learning-based methods like RL algorithms. PID controllers remain popular in industrial applications because of their simple approach and ability to respond to more complicated changes. This research utilizes the advantages of RL to tune the parameters of the PID controller. SCMA-TD3, ICMA-TD3 and DDPG algorithm is successfully used to tune multivariable complex process of BTS. Implementing TD3 and DDPG has resulted in decreased oscillations and settling time, along with enhanced system efficiency and stability in comparison to conventional PID tuning techniques. The proposed ICMA-TD3 algorithm outperforms SCMA-TD3 and DDPG algorithms in reducing errors across several measures. ICMA-TD3 controls electric power and drum water level with lower error metrics and faster response while maintaining less overshoot to achieve optimal performance. SCMA-TD3 regulates drum pressure better but with a considerable amount of undershoots. DDPG has a high-cost function but is ineffective owing to more rise time and oscillation. The results indicate that ICMA-TD3 improves system performance in a balanced manner, improving the overall system performance for the BTS.

Future work can be extended to test the algorithms on real-time industrial data to ensure their practicality and robustness under plant-level disturbances and operational limitations. Other advanced RL algorithms can be used, including new actor-critic variants like Soft Actor-Critic (SAC) and Proximal Policy Optimization (PPO), to assess their performance and convergence behavior in more complex control scenarios. The convergence speed, robustness, control speed can be compared to varying initial conditions and noise levels. There is a need to develop a generalized MIMO PID tuning framework that can be applied to a wider range of industrial processes characterized by strong coupling and nonlinearities. This includes extending the approach to systems such as distillation columns, CSTRs, and other complex process applications. Future research can also focus on establishing standardized performance benchmarks under varying load conditions and disturbances. Such benchmarks would facilitate the evaluation of RL-based control techniques in real-time industrial settings by verifying algorithm scalability and adaptability through standardized disturbance profiles, load step tests, and fault injection scenarios.

Data availability

The datasets used and/or analysed during the current study available from the corresponding author on reasonable request.

Abbreviations

- BTS:

-

Boiler Turbine System

- RL:

-

Reinforcement Learning

- MIMO:

-

Multi-Input Multi-Output

- PID:

-

Proportional-Integral-Derivative

- DDPG:

-

Deep Deterministic Policy Gradient

- TD3:

-

Twin Delayed Deep Deterministic Policy Gradient

- ICMA:

-

Individual Critic Multi-Agent

- SCMA:

-

Shared Critic Multi-Agent

- CSTR:

-

Continuous Stirred Tank Reactor

- PCA:

-

Principal Component Analysis

- MSPC:

-

Multivariate Statistical Process Control

- MPC:

-

Model Predictive Controller

- EMPC:

-

Economic Model Predictive Controller

- ADRC:

-

Active Disturbance Rejection Controller

- ADP:

-

Adaptive Dynamic Programming

- ITAE:

-

Integral Time Absolute Error

- IAE:

-

Integral Absolute Error

- ISE:

-

Integral Square Error

- GS:

-

Gain Scheduling

- FO:

-

Fractional Order

- IOFL:

-

Input / Output Feedback Linearization

- PILCO:

-

Probabilistic Inference for Learning

- LSTM:

-

Long Short Term Memory

- MV:

-

Manipulated Variable

- LQG:

-

Linear Quadratic Gaussian

- NL:

-

Non-linear

- \(x_{1\text {-BTS}}, y_{1\text {-BTS}}(t)\) :

-

Drum pressure of BTS (kg/cm2)

- \(x_{2\text {-BTS}}, y_{2\text {-BTS}}(t)\) :

-

Electric power of BTS (MW)

- \(x_{3\text {-BTS}}\) :

-

Fluid density of BTS (kg/m3)

- \(\dot{x}_{1\text {-BTS}}, \dot{x}_{2\text {-BTS}}, \dot{x}_{3\text {-BTS}}\) :

-

State derivatives of BTS states

- \(u_{1\text {-BTS}}\) :

-

Fuel control valve (normalized mass flow rate)

- \(u_{2\text {-BTS}}\) :

-

Steam valve to turbine

- \(u_{3\text {-BTS}}\) :

-

Feedwater valve to drum

- \(y_{3\text {-BTS}}(t)\) :

-

Drum water level deviation (m)

- \(q_{\text {ev(BTS)}}\) :

-

Evaporation rate

- \(s_{q(\text {BTS})}\) :

-

Steam quality

- \(k_p\) :

-

Proportional gain

- \(k_i\) :

-

Integral gain

- \(\theta\) :

-

Policy parameters

- \(\Phi\) :

-

Q-function parameter

- s :

-

State

- a :

-

Action

- r :

-

Reward

- \(s'\) :

-

Next state

- d :

-

Terminal flag

- \(\text {targ}\) :

-

Target

- \(\mu _\theta (s)\) :

-

Policy

- \(\epsilon\) :

-

Exploration noise

- D :

-

Replay buffer

- B :

-

Batch of transitions

- y :

-

Goal value

- \(\gamma\) :

-

Discount factor

- Q :

-

Q function

- \(\nabla _\theta\) :

-

Gradient descent

- t :

-

Time

- e(t):

-

Error

- i :

-

Index

- j :

-

Iterations

- c :

-

Clipping threshold

- \(\rho\) :

-

Update rate

References

Fu, C. & Tan, W. Partially decentralized control based on imc for a benchmark boiler. In The 27th Chinese Control and Decision Conference (2015 CCDC), 31–35 (IEEE, 2015).

Vijula, D. A. & Devarajan, N. Decentralized pi controller design for nonlinear multivariable systems based on ideal decoupler. J. Theor. & Appl. Inf. Technol. 64 (2014).

Garrido, J., Morilla, F. & Vazquez, F. Centralized pid control by decoupling of a boiler-turbine unit. In European Control Conference (ECC), 4007–4012 (2009).

Kumaran, A. A., Bala, M. P. & Sivaraman, V. Three element boiler drum level control using cascade controller. Int. J. Res. Appl. Sci. Eng. Technol 6, 2835–2839 (2018).

Gopmandal, F., Jain, G. & Ghosh, A. Gain scheduled centralized pi control design for a boiler-turbine unit. In Seventh Indian Control Conference (ICC), 69–74 (2021).

Tan, W., Marque, H. J., Chen, T. & Liu, J. Analysis and control of a nonlinear boiler-turbine unit. J. Process. Control. 15, 883–891 (2005).

Moradi, H., Alasty, A., Saffar-Avval, M. & Bakhtiari Nejad, F. Multivariable control of an industrial boiler-turbine unit with nonlinear model: A comparison between gain scheduling & feedback linearization approaches. Sci. Iran. 20, 1485–1498 (2013).

Abokhatwa, G. S. & Goma, A. M. Lqg control design for boiler-turbine system. In Conference of Industrial Technology (CIT2017), 1–6 (2017).

Ahmadi, A., Najafi, S. & Batmani, Y. Industrial boiler-turbine-generator process control using state dependent riccati equation technique. In 6th International Conference on Control, Instrumentation and Automation (ICCIA), 1–5 (2019).

Balko, P. & Rosinová, D. Robust decentralized control of nonlinear drum boiler. IFAC-PapersOnLine 48, 432–437 (2015).

Gao, D. X. & Cui, B. T. Lqr controller design of mimo systems with external disturbances based on stability degree constraint. In IEEE International Conference on Mechatronics and Automation, 1848–1852 (2010).

Kashyap, G. S., Sant, A. V. & Yadav, A. K. Gain scheduled proportional integral control of a model based boiler turbine system. Elsevier BV 62, 7028–7034 (2022).

Vaishnavi, A., Sekhar, S. A. & Jeyanthi, R. Application of unconstrained controllers for a linearized benchmark boiler. In 2019 2nd International Conference on Power and Embedded Drive Control (ICPEDC), 64–69 (IEEE, 2019).

Chithra, K., Princess, M. R. & Prabhu, B. Design and control of ideal decoupler for boiler turbine system. Int. J. Sci. Res.(IJSR) 4, 1520-1525. (2013).

Kruthika, U. & Paneerselvam, S. Enhanced set-point tracking in a boiler turbine system via decoupled mimo linearization and comparative lqr-based control strategy. Results Eng. 25, 103914 (2025).

Moradi, H., Alasty, A. & Vossoughi, G. Nonlinear dynamics and control of bifurcation to regulate the performance of a boiler–turbine unit. Elsevier BV 68, 105–113 (2013).

Han, Z. X., Zhou, C. X. & Li, D. On a pathological mathematical model of boiler-turbine generator unit. In Asia Simulation Conference-7th International Conference on System Simulation and Scientific Computing, 1104–1109 (2008).

Wang, G., Wu, J. & Ma, X. A nonlinear state?feedback state?feedforward tracking control strategy for a boiler?turbine unit. Asian J. Control. 22, 2004–2016 (2020).

Jeyanthi, R. & Anwamsha, K. Fuzzy-based sensor validation for a nonlinear benchmark boiler under mpc. In 2016 10th International Conference on Intelligent Systems and Control (ISCO), 1–6 (2016).

Ghabraei, S., Moradi, H. & Vossoughi, G. Multivariable robust regulation of an industrial boiler-turbine with model uncertainties. In 2020 9th International Conference on Modern Circuits and Systems Technologies (MOCAST), 1–4 (IEEE, 2020).

Zrigan, A. F., Shi, G., Altrmal, H. A. & Elsouri, K. S. Control of the boiler turbine unit based on active disturbance rejection control. In 2023 IEEE 3rd International Maghreb Meeting of the Conference on Sciences and Techniques of Automatic Control and Computer Engineering (MI-STA), 223–228 (IEEE, 2023).

Rehman, I. U., Javed, S. B., Chaudhry, A. M., Azam, M. R. & Uppal, A. A. Model-based dynamic sliding mode control and adaptive kalman filter design for boiler-turbine energy conversion system. Elsevier BV 116, 221–233 (2022).

Zhao, S., Wang, S., Cajo, R., Ren, W. & Li, B. Power tracking control of marine boiler-turbine system based on fractional order model predictive control algorithm. Multidiscip. Digit. Publ. Inst. 10, 1307–1307 (2022).

Sunori, S. K., Juneja, P. K. & Jain, A. B. Model predictive control system design for boiler turbine process. Int. J. Electr.Comput. Eng. 5 (2015).

Liu, X. & Cui, J. Economic model predictive control of boiler-turbine system. Elsevier BV 66, 59–67 (2018).

Su, Z., Zhao, G. Q., Yang, J. & Li, Y. Disturbance rejection of nonlinear boiler–turbine unit using high-order sliding mode observer. Inst. Electr. Electron. Eng. 50, 5432–5443 (2020).

Zhang, J., Yang, D., Zhang, H., Wang, Y. & Zhou, B. Dynamic event-based tracking control of boiler turbine systems with guaranteed performance. Inst. Electr. Electron. Eng. 1, 1–11 (2023).

Wang, Y., Zong, G., Zhao, X. & Yi, Y. Fixed-time control of asymmetric output-constrained nonlinear systems and its application to boiler–turbine unit. Inst. Electr. Electron. Eng. 53, 7201–7209 (2023).

Wang, J., Baocang, D. & Ping, W. Modeling and finite-horizon mpc for a boiler-turbine system using minimal realization state-space model. Energies 15, 7935 (2022).

Moon, U. C. & Lee, K. Y. Step-response model development for dynamic matrix control of a drum-type boiler–turbine system. IEEE Trans. Energy Convers. 24, 423–430 (2009).

Jalali, A. A. & Golmohammad, H. An optimal multiple-model strategy to design a controller for nonlinear processes: A boiler-turbine unit. Comput. Chem. Eng. 46, 48–58 (2012).

Ghabraei, S., Moradi, H. & Vossoughi, G. Multivariable robust adaptive sliding mode control of an industrial boiler–turbine in the presence of modeling imprecisions and external disturbances: A comparison with type-i servo controller. ISA Transactions 58, 398–408 (2015).

Kruthika, U. & Paneerselvam, S. Enhancing boiler-turbine trajectory tracking with lqr-optimized pid control strategy. In International Conference on Recent Advances in Science and Engineering Technology (ICRASET), 1–7 (2023).

Wei, L. & Fang, F. H infinity lqr-based coordinated control for large coal-fired boiler–turbine generation unit. IEEE Trans. Ind. Electron. 64, 5212–5221 (2016).

Wu, J., Nguang, S. K., Shen, J., Liu, G. & Li, Y. G. Robust h infinity tracking control of boiler–turbine systems. ISA Transactions 49, 369–375 (2010).

Li, C., Zhou, J., Li, Q., An, X. & Xiang, X. A new t–s fuzzy-modeling approach to identify a boiler–turbine system. Expert Syst. Appl. 37, 2214–2221 (2010).

Sarailoo, M., Rahmani, Z. & Rezaie, B. Fuzzy predictive control of a boiler–turbine system based on a hybrid model system. Ind. Eng. Chem. Res. 53, 2362–2381 (2014).

Wu, X., Shen, J., Li, Y. & Lee, K. Y. Data-driven modeling and predictive control for boiler–turbine unit. IEEE Trans. Energy Convers. 28, 470–481 (2013).

Zhu, J., Wu, X. & Shen, J. Practical disturbance rejection control for boiler-turbine unit with input constraints. Elsevier BV 161, 114184–114184 (2019).

Kruthika, U. & Surekha, P. A hybrid linear quadratic regulator-based control strategy for multivariable boiler turbine system. In 2024 4th International Conference on Mobile Networks and Wireless Communications (ICMNWC), 1–6 (IEEE, 2024).

Abdelbaky, M. A., Kong, X., Liu, X. & Lee, K. Y. Optimal iofl-based economic model predictive control technique for boiler-turbine system. ISA Transactions 153, 143–154 (2024).

Abdelbaky, M. A., Liu, X. & Kong, X. Stable constrained model predictive control based on iofl technique for boiler-turbine system. Trans. Inst. Meas. Control 47, 1104-1116. (2024).

Ławry´nczuk, M. Nonlinear predictive control of a boiler-turbine unit: A state-space approach with successive on-line model linearisation and quadratic optimisation. Elsevier BV 67, 476–495 (2017).

Wang, L., Cai, Y. & Ding, B. Robust model predictive control with bi-level optimization for boiler-turbine system. Inst.Electr. Electron. Eng. 9, 48244–48253 (2021).

Wei, Q., Lu, J., Zhou, T., Cheng, X. & Wang, F. Event-triggered near-optimal control of discrete-time constrained nonlinear systems with application to a boiler-turbine system. Inst. Electr. Electron. Eng. 18, 3926–3935 (2022).

Das, S., Pan, I., Halder, K., Das, S. & Gupta, A. Lqr-based improved discrete pid controller design via optimum selection of weighting matrices using fractional order integral performance index. Appl. Math. Model. 37, 4253–4268 (2013).

Zhao, G. Q., Sun, Y., Su, Z. & Hao, Y. Receding galerkin optimal control with high-order sliding mode disturbance observer for a boiler-turbine unit. Multidiscip. Digit. Publ. Inst. 15, 10129–10129 (2023).