Abstract

Previous studies found that melanoma antigen genes (MAGE) were antigens expressed in various tumor cells but hardly expressed in normal tissues, and their unique expression pattern made them highly promising for cancer immunotherapy. MAGE-A10 was a member of the MAGE family, and although it was expressed in various tumors, its specific function remained unclear. In this study, we conducted a comprehensive pan-cancer analysis of MAGE-A10 expression, prognostic value, DNA methylation, genetic variation, function, immune infiltration, and drug sensitivity using multiple public databases. The results showed that MAGE-A10 was highly expressed in tumor tissues of most cancer types and was associated with poor prognosis. Additionally, MAGE-A10 was closely related to methylation levels, genetic variation, immune cell infiltration, immune therapy response, and chemotherapy resistance, possibly due to its role in regulating gene expression, cell differentiation, and immune response. Validation experiments in gastric cancer found that high expression of MAGE-A10 significantly affected patient prognosis. Gene set enrichment analysis (GSEA) indicated that high expression of MAGE-A10 was closely associated with the binding of histone deacetylases. Cell experiments showed that knocking down MAGE-A10 significantly reduced the proliferation, migration, and invasion capabilities of gastric cancer cells, which might be related to its regulation of the expression of cell adhesion molecule cadherins. In conclusion, this study indicated that MAGE-A10 was a potential tumor prognostic biomarker and immunotherapy target and played an important role in the proliferation, migration, and invasion of gastric cancer cells.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Cancer represented a significant global public health concern and ranked as the second leading cause of death worldwide1. The increasing incidence and mortality of cancer could be attributed to population growth, aging, changes in the prevalence and distribution of disease risk factors, and socio-economic development2. Research reports indicated that around 3.21 million individuals succumbed to cancer as of 20223. The latest assessment by the American Cancer Society estimated that 609,820 individuals would succumb to cancer in the United States by 20231. In recent years, rapid advancements in cancer immunotherapy, encompassing immune checkpoint blockade, tumor vaccines, adoptive cell transfer, immunocellular therapy, and innovative therapeutic strategies targeting T cell co-stimulatory and co-inhibitory receptors, significantly enhanced cancer treatment and prognosis4,5,6. The presence of specific antigens within the tumor was a fundamental prerequisite for the effectiveness of immunotherapy7. However, the availability of matching tests for immunotherapy-related biomarkers in some cancers remained limited8underscoring the urgent necessity for additional exploration of effective tumor prognostic biomarkers associated with immunotherapy to aid patients in decision-making regarding immune checkpoint inhibitor-based therapies9.

Melanoma-associated antigen (MAGE) was first identified as a tumor-associated antigen in melanoma patients10. Based on the chromosomal location of the genes and the tissue distribution of their products, MAGEs could be categorized into two groups: MAGE-I and MAGE-II. The MAGE-I proteins belonged to the wider cancer-testis antigen (CTAs) family, which included the multi-gene families MAGE-A, -B, and -C11,12. Recent studies demonstrated an association between the expression of CTAs and lymph node metastasis, tumor staging, and prognosis in lung cancer patients13. MAGE-A10 was a highly immunogenic member of the cancer/testis antigen (CTAs) family14. This nuclear protein was highly expressed in malignant tumors of the lung, skin, and urothelium. High levels of protein expression could also be detected in gynecologic malignancies and gallbladder cancer15. MAGE-A10 played a significant role in various types of tumors. For instance, studies indicated its high expression in high-grade non-muscle-invasive bladder cancer, and its association with high tumor grade and invasiveness, offering potential as a target for immunotherapy, along with other CTAs16. Furthermore, studies suggested that MAGE-A10 could serve as a predictive marker for early liver recurrence in gastric and gastroesophageal junction cancer following surgery, and that it might also be a target for immunotherapy in gastric cancer17,18. Moreover, a study by Qin H et al. revealed that high expression of MAGEA, including MAGE-A10, was correlated with poor prognosis in various cancers, especially with chemotherapy resistance, tumor growth, cancer progression, lymph node metastasis, and increased recurrence rates in pancreatic ductal adenocarcinoma (PDAC)19. Additionally, Lisica Šikić N et al. reported that the expression of MAGE-A10 could predict non-response and low sensitivity to platinum-based chemotherapy in late-stage high-grade serous ovarian cancer, and was associated with overall survival20. Nevertheless, the expression levels and clinical significance of MAGE-A10 in most types of cancer remained to be clarified.

In Fig. 1,our study study conducted a comprehensive bioinformatics analysis of MAGE-A10 using multiple databases to elucidate its expression, prognostic significance, genetic variations, DNA methylation, and associated pathways in various cancers. Additionally, it investigated the role of MAGE-A10 in the tumor immune microenvironment and assessed its correlation with immune therapy response and drug sensitivity. The expression levels of MAGE-A10 in normal stomach and stomach adenocarcinoma (STAD) tissues were also examined, along with their impact on STAD prognosis. Finally, the mRNA and protein expression levels of MAGE-A10 were validated in STAD in vitro, identifying it as an independent prognostic risk factor for stomach adenocarcinoma.

The flowchart of this study. The comprehensive pan-cancer analysis of MAGEA10 includes gene expression, Cox regression analysis, mutation, DNA methylation, enrichment analysis, immune-related analysis, and drug sensitivity analysis. For experimental validation, we used gastric cancer cells to detect the expression of MAGEA10. The biological function of MAGEA10 and its related signaling pathways were also explored in gastric cancer cell lines. The experiments included PCR, cell proliferation, cell scratch assay, colony formation, chamber invasion, and Western blotting.

Materials and methods

Pan-cancer data collection

The Human Protein Atlas (HPA) (http://www.proteinatlas.org) was an extensive network that offered comprehensive protein information on tissues and organs. This network enabled us to comprehend the localization and protein expression level of MAGE-A1021. Differential gene expression analysis of MAGE-A10 was performed using SangerBox3.0 in unpaired normal and tumor tissues, with parameter normalization to log2(x + 0.001) for sequencing data. Additionally, Supplementary Table 1 provided the abbreviations for each tumor type.

Prognostic evaluation in pan-cancer

To study the prognosis of MAGE-A10 in human cancer, we implemented a univariate Cox proportional hazards regression model based on The Cancer Genome Atlas (TCGA) database using Sangerbox3.0 (http://sangerbox.com/). This approach aimed to examine the correlation between MAGE-A10 and overall survival (OS), disease-specific survival (DSS), disease-free interval (DFI), and progression-free interval (PFI) across various tumors.

Epigenetic alteration analysis

The cBioPortal database (http://www.cbioportal.org/) was utilized to access the “PanCancer Studies” and “Pan-cancer analysis of whole genomes” module to retrieve data on the types and frequencies of genetic variations in MAGE-A10 across pan-cancer cases. Subsequently, SangerBox 3.0 was employed to visualize the copy number variations of MAGE-A10 mRNA expression in pan-cancer, followed by an independent analysis of the top 15 genes exhibiting the highest mutation frequencies within the high and low expression groups of MAGE-A10 in STAD.

DNA methylation analysis

The promoter DNA methylation status of MAGE-A10 in normal and pan-cancer tissues was available from UALCAN (http://ualcan.path.uab.edu/analysis.html)22. MethSurv (http://biit.cs.ut.ee/methsurv/) was an interactive, user-friendly platform that provided univariate and multivariate survival analyses of DNA methylation biomarkers based on the TCGA database23.

Functional enrichment analysis

The top 100 MAGE-A10-related genes were retrieved from the “Similar Gene Detection” module of the Gene Expression Profiling Interactive Analysis (GEPIA2) database(http://gepia2.cancer-pku.cn/)24. GeneMANIA (http://www.genemania.org) was a versatile and user-friendly web interface utilized for generating gene function hypotheses, analyzing gene lists, prioritizing function detection genes25and visualizing the aforementioned related genes. The String database (https://string-db.org/) selected 50 experimental interactions of MAGE-A10-binding proteins, using a confidence level of 0.150 as the minimum interaction score requirement with Homo sapiens as the target species, and then displayed them using Cytoscape (version 3.9.0) based on the degree of interaction. Finally, the R software (version 4.3.0) along with the clusterProfiler, org.Hs.eg.db, and ggplot2 packages were utilized to perform Kyoto Encyclopedia of Genes and Genomes (KEGG)26,27 and Gene Ontology (GO) analyses of MAGE-A10-binding proteins and co-expressed genes.

The correlation between MAGE-A10 expression and the tumor microenvironment (TME) and immune checkpoints

The tool for integrating tumor immune infiltration and genetic or clinical features was called Tumor Immune Estimation Resource (TIMER2.0) (http://timer.cistrome.org/)28. The “immune gene” module was utilized to examine the correlation of MAGE-A10 with M2 macrophages, natural killer (NK) cells, and cancer-associated fibroblasts (CAFs). Utilizing scatter plots, it visualized the p and correlation (cor) values obtained from the refined Spearman rank correlation test. The Tumor Immune Dysfunction and Exclusion (TIDE) database (http://tide.dfci.harvard.edu) gathered and analyzed biomarkers, large-scale histological data from CRISPR screening, non-immunotherapy tumor profiles, and published ICB trials29,30,to investigate the association between MAGE-A10 and the response to immunotherapy.

MAGE-A10 expression and its correlation with immune therapy response and drug sensitivity analysis

The ROC Plotter (http://rocplot.org) was utilized for analyzing transcriptome data and investigating the correlation between gene expression, chemotherapy response, and biomarker prediction in malignancies including breast cancer, ovarian cancer, colorectal cancer, and pleomorphic glioblastoma31. The ROC curve was employed to evaluate the predictive value of MAGE-A10 expression in cancer treatment response. Additionally, the NCI-60 cell line and the CellMiner database (https://discover.nci.nih.gov/cellminer/home.do) were used to investigate the relationship between MAGE-A10 and drug sensitivity32. RNA-seq expression data and NCI-60 chemical activity data were retrieved, and clinical trials and FDA-approved drugs were chosen. The analysis utilized the “limma”, “impute”, “ggpubr”, and “ggplot2” packages in R. Ultimately, SangerBox 3.0 was employed to conduct Pearson analysis and assess the correlation between tumor mutational burden (TMB) and microsatellite instability (MSI) for each tumor.

Obtain gene expression data profiles for gastric cancer

The GSE54129 dataset, containing 111 samples of gastric cancer tissue and 21 samples of non-cancer tissue, was acquired from the Gene Expression Omnibus (GEO) database (https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/). Additionally, the GDC/TCGA-STAD transcriptome data, consisting of 407 samples, was procured from the UCSC Xena website (https://xenabrowser.net/datapages/). Subsequently, the dataset was processed and examined to extract the expression levels of MAGE-A10 in gastric cancer tissues and normal gastric tissues using the tidyverse, stringr, GEOquery, and limma packages in R software (version 4.3.0). The ggplot2 and ggpubr packages were employed to graphically represent the data.

Construction of diagnostic models and prognosis analysis

The TCGA-STAD transcriptome data and the GSE54129 expression profile data were used to generate the ROC curve using the pROC package in R (version 4.3.0). Subsequently, the Kaplan-Meier plotter (https://kmplot.com/analysis) was used to analyze the overall survival rate (OS) and progression-free survival (PPS) of MAGE-A10.

Gene set enrichment analysis (GSEA)

The TCGA-STAD transcriptome data was used to stratify MAGE-A10 into low and high expression groups based on the median expression value across all samples. Subsequently, gene set enrichment analysis (GSEA) was conducted in R software (version 4.3.0) using the R packages tidyverse, clusterProfiler, org.Hs.eg.db, and the gseGO function. The reference gene set consisted of GO pathways, and significant enrichment was determined by |NES|>1, p.adjust < 0.05, and FDR value (q-value) < 0.25.

Results

MAGE-A10 expression and localization in normal and pan-cancer tissues

Analysis of HPA and Genotype-Tissue Expression (GTEx) data revealed high expression of MAGE-A10 in normal placental and testicular tissues (Fig. 2A). Immunohistochemical staining exhibited high expression of MAGE-A10 protein in normal placental and testicular tissues, with localization in the nucleus and cytoplasm (Fig. 2B). Additionally, immunofluorescence images of the SH-SY5Y human neuroblastoma cell line from the HPA database confirmed the nuclear and cytoplasmic localization of MAGE-A10 (Fig. 2C), consistent with the immunohistochemistry results. Subsequent analysis of MAGE-A10 mRNA expression in the TCGA database identified high expression in 15 types of tumors, including LUAD, COAD, COADREAD, ESCA, STES, KIPAN, STAD, UCEC, HNSC, KIRC, LUSC, LIHC, READ, BLCA, CHOL (p < 0.05, Fig. 2D). Given the limited number of normal samples in TCGA, an integration with the GTEx database was performed to evaluate MAGE-A10 expression in 27 types of tumors, revealing significant expression differences across these 27 tumors (p < 0.05, Fig. 2E). Subsequently, the CPTAC database was utilized to analyze the variations in MAGE-A10 protein expression levels in different malignancies. The outcomes indicated that compared to the surrounding normal tissues, MAGE-A10 protein was upregulated solely in LUSC, HNSC, and UCEC, and notably downregulated in LUAD (p < 0.05, Supplementary Fig. 1).

Expression and localization of MAGEA10. (A) mRNA expression levels of MAGEA10 in normal tissues from the HPA database. (B) Representative immunohistochemistry (IHC) images of MAGEA10 in normal testis and placenta tissues. (C) Subcellular distribution of MAGEA10 based on the HPA database. (D) Analysis of MAGEA10 mRNA expression in 15 types of tumors and normal tissues. (E) mRNA expression levels of MAGEA10 analyzed using the TCGA and GTEx databases.

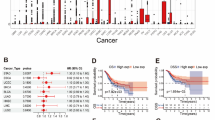

The prognostic value of MAGE-A10 in pan-cancer

Using the TCGA database, we employed Sangerbox to construct a forest plot and performed univariate Cox regression analysis to investigate the prognostic relevance of MAGE-A10 in diverse cancer types. Analysis of overall survival (OS) demonstrated a correlation between elevated MAGE-A10 expression and reduced OS in STES, KIRP, KIPAN, STAD, KIRC, LIHC, PAAD, and UVM (p < 0.05, depicted in Fig. 3A). Subsequent to DSS analysis in STES, KIRP, KIPAN, STAD, KIRC, LIHC, and UVM, it was disclosed that heightened MAGE-A10 expression posed a high-risk factor for reduced disease-specific survival (DSS) (p < 0.05, as evident in Fig. 3B). Reduced expression of MAGE-A10 led to extended disease-free interval (DFI) in KIRP, STAD, LIHC, STES, and COADREAD patients (p < 0.05, as indicated in Fig. 3C). Analysis of progression-free interval (PFI) revealed a negative correlation between MAGE-A10 expression and PFI in STES, KIRP, KIPAN, STAD, KIRC, and LIHC (p < 0.05, demonstrated in Fig. 3D).

Epigenetic alteration of MAGE-A10 in pan-cancer

We studied the genetic variants of the MAGE-A10 gene in various cancer tissues on cBioPortal. Figure 4A indicated that of 2683 samples collected from 2565 patients with diverse cancer types, 193 samples exhibited MAGE-A10 expression variations, accounting for 7% of all samples. MAGE-A10 exhibited mutation in 45 cancer types. Figure 4B demonstrated that MAGE-A10 experienced mutations in 31 types of cancer, including stomach adenocarcinoma (STAD). The predominant variation was “mutation” and “amplification” in the CNA in STAD. Subsequently, we investigated the differences between copy number alterations (CNA) of the MAGE-A10 gene in various cancer tissues and the MAGE-A10 mRNA expression. We detected notable variances in seven tumor types, including BRCA, ESCA, STES, SARC, STAD, LUSC, and MESO, as illustrated in Fig. 4C. We further analyzed the spectrum of mutations in the MAGE-A10 high/low expression groups in STAD and detected 15 mutation genes, specifically, these genes include FLG, RYR2, CSMD1, RYR1, and DNAH3, as shown in Fig. 4D.

Genetic variation analysis of MAGEA10. (A) Genetic alterations of MAGEA10 in pan-cancer tissues, accounting for 7% of alterations (alterations/profiles = 193/2683). (B) Frequency of MAGEA10 mutation types in different cancers. (C) Differences in MAGEA10 copy number alterations (CNA) and its mRNA expression in pan-cancer tissues. (D) The top 15 genes with the highest mutation frequency in the MAGEA10 high expression group and MAGEA10 low expression group in STAD.

DNA methylation of MAGE-A10 in pan-cancer

DNA methylation was of great significance in the development, differentiation, and the pathogenesis of diseases, and was considered one of the characteristics of cancer. DNA methylation primarily targeted CpG islands, such as gene promoters or enhancer elements. The UALCAN database was utilized to analyze the level of DNA methylation of the MAGE-A10 promoter. In comparison to normal tissues, tumor tissues showed lower levels of methylation as observed across BLCA, BRCA, CESC, COD, ESCA, GBM, HNSC, and KIRC, while CHOL and THYM showed elevated methylation levels (Fig. 5A). The impact of DNA methylation within MAGE-A10 CpG sites on cancer prognosis was investigated using the Methsurv database. The results indicated that the methylation level at eight CpG sites of the MAGE-A10 gene was associated with cancer prognosis, including cg25549519, cg04950711, cg05215305, cg11852385, cg13492609, cg13994408, cg19964192, and cg26982030 (p < 0.05, Supplementary Table 2). Additionally, it demonstrated that the methylation level of the MAGE-A10 CpG site cg19964192 was positively correlated with the prognosis of ACC, CESC, LIHC, SARC, SKCM, UCEC, and UVM, but was inversely correlated with prognosis (p < 0.05, Fig. 5B).

Functional enrichment analysis

In the study of MAGE-A10’s molecular mechanisms in cancer, we initially retrieved 100 MAGE-A10-related genes from the TCGA database using GEPIA. Subsequently, these genes underwent further screening and visualization using GeneMANIA, resulting in the identification of 49 related genes (Fig. 6A). Furthermore, we obtained 50 proteins that bound to MAGE-A10 from the STRING database and conducted an analysis, arranging them by degree using Cytoscape (version 3.9.0) (Fig. 6B). Additionally, KEGG and GO enrichment analyses were performed on the MAGE-A10-related proteins and genes. The KEGG analysis revealed that MAGE-A10 was principally associated with seven signaling pathways, encompassing transcriptional misregulation in cancer, melanogenesis, tyrosine metabolism, antigen processing and presentation, ATP-dependent chromatin remodeling, cell adhesion molecules, and primary immunodeficiency (Fig. 6C). The GO analysis indicated that MAGE-A10 was involved in various biological processes(BP), including pigmentation, developmental pigmentation, melanin biosynthetic process, melanin metabolic process, and secondary metabolite biosynthetic process. Moreover, the cellular components(CC) of MAGE-A10-related genes comprised melanosome, pigment granule, melanosome membrane, chitosome, and pigment granule membrane, while the molecular function(MF) analysis primarily focused on the process of histone deacetylase binding (Fig. 6D).

Enrichment analysis of MAGEA10-related genes. (A) Fifty binding proteins of MAGEA10 obtained from the STRING database, with the interaction network displayed using Cytoscape. (B) Interaction network of 49 MAGEA10-related genes using GeneMANIA. (C) GO analysis of MAGEA10. (D) KEGG analysis of MAGEA10.

Pan-cancer immunogenicity analysis

The interaction between tumour cells and the tumour microenvironment (TME) played a crucial role in cancer development33. Tumour-associated macrophages (TAMs) were a significant type of immune cells in the TME and were considered equivalent to M2 polarized macrophages. They supported tumour cell invasion, metastasis, and angiogenesis while suppressing antitumour immunity34,35,36. Subsequently, we chose to use CIBERSORT to evaluate the correlation between levels of MAGE-A10 and M2 macrophages in different cancers. The results showed that in 7 types of cancer, the levels of MAGE-A10 were positively correlated with M2 macrophages, including GBM, KIRP, LIHC, OV, READ, SKCM, and SKCM-Primary, whereas the levels of MAGE-A10 were negatively correlated with M2 macrophages in TGCT and ESCA (Fig. 7A).Natural killer (NK) cells were cytotoxic lymphocytes of the innate immune system, capable of killing virus-infected and/or cancer cells, and were an important part of cancer immunotherapy37,38. In GBM, KIRC, KIRP, LIHC, PRAD, READ, TGCT, SKCM, and SKCM-Primary, the levels of MAGE-A10 were positively correlated with NK cells evaluated by the MCPCOUNTER algorithm. On the other hand, the level of NK cells decreased as the level of MAGE-A10 in LUSC increased (Fig. 7B).Furthermore, it was demonstrated that cancer-associated fibroblasts (CAFs) in the stroma of the TME played a role in regulating the function of tumour immune cells39. We used EPIC, MCPCOUNTER, XCELL, and TIDE to comprehensively assess whether there was a relationship between levels of MAGE-A10 expression and CAF levels. It was found that CAFs were positively correlated with MAGE-A10 levels in HNSC and HNSC-HPV, while the opposite trend was observed in TGCT (Fig. 7C).

Significant advances were made in cancer immunotherapy through the use of immune checkpoint blockade (ICB)40. Nevertheless, a minority of patients responded to ICB treatment in the majority of cancer types30,40. Consequently, it was crucial to identify novel immune therapy response markers for cancer immunotherapy. Comparison of MAGE-A10 with other standardized biomarkers in predicting ICB efficacy revealed that MAGE-A10 achieved an AUC value exceeding 0.5 in 8 cohorts and was more effective in forecasting immune therapy outcomes for glioblastoma and melanoma patients (Fig. 8A). Elevated MAGE-A10 expression in the Nathanson2017_CTLA4 cohort impacted CTLA4 in melanoma patients and extended overall survival (Supplementary Fig. 2). CD8 cytotoxic T lymphocytes (CTL) are immune cells that target tumors41. Dysfunction of CTL promoted the development of adaptive immune resistance, leading to tumor immune evasion42. Our analysis using the TIDE database revealed the association between MAGE-A10 and CTL dysfunction. MAGE-A10 demonstrated a positive correlation with the degree of CTL dysfunction in multiple cancer types; however, in specific cancer types, it displayed a negative correlation (Fig. 8B). Furthermore, elevated MAGE-A10 expression in GSE1427-AML resulted in enhanced CTL infiltration, benefiting anti-tumor immunity and prolonging patient survival and clinical treatment benefits, whereas low MAGE-A10 expression did not produce these outcomes (Fig. 8C). It is noteworthy that decreased MAGE-A10 expression in GSE13507-Bladder cancer was associated with reduced CTL infiltration; nevertheless, it extended patient survival (Fig. 8D).

Correlation analysis of MAGEA10 with anti-tumor immunity. (A) Evaluating the efficacy of MAGEA10 in predicting IC B treatment compared to standardized biomarkers. (B) Correlation between MAGEA10 and CTL dysfunction in pan-cancer analyzed using the TIDE database. (C) Prognostic analysis of MAGEA10 expression and CTL infiltration in GSE1427-AML. (D) Prognostic analysis of MAGEA10 expression and CTL infiltration in GSE13507-Bladder cancer.

Drug sensitivity analysis

The analysis of the transcriptome revealed that high MAGE-A10 expression in Breast cancer and Colorectal carcinoma was associated with chemoresistance, whereas low expression in Ovarian cancer was linked to reduced chemotherapy efficacy. In Glioblastoma multiforme, MAGE-A10 expression did not significantly affect the response to chemotherapy (Fig. 9A). Furthermore, the CellMiner database was employed to explore the relationship between MAGE-A10 expression levels and drug sensitivity. The results showed a positive correlation between MAGE-A10 expression levels and the sensitivity to specific drugs, such as PD-98,059, Nandrolone phenpropionate, GW-5074, and ARRY-162. Conversely, the sensitivity to another 21 drugs, including PYRAZOLOACRIDINE, RH1, and Floxuridine, was inversely correlated with MAGE-A10 expression levels (Fig. 9B). These findings strongly linked MAGE-A10 expression with specific anti-tumor drugs, such as Floxuridine, 6-Mercaptopurine, Intedanib, VINORELBINE, Fluorouracil, Idarubicin, MITOXANTRONE, and METHOTREXATE.Finally, in the context of TMB and MSI being predictive factors for immunotherapy43we investigated the relationship between MAGE-A10 expression and TMB, as well as its correlation with MSI. Pearson correlation analysis illustrated a positive correlation between MAGE-A10 expression and TMB in LUAD (R = 0.3888, P = 2.58e-9), HNSC (R = 0.2342, P = 0.0001), LUSC (R = 0.1234, P = 0.0154), and BLCA (R = 0.1323, P = 0.0261), and a negative correlation between MAGE-A10 expression and TMB in STES (R=-0.1309, P = 0.0227) (Fig. 9C). Additionally, in CESC (R = 0.1583, P = 0.0259) and HNSC (R = 0.1474, P = 0.0157), MAGE-A10 expression levels demonstrated a positive correlation with MSI, while STES (R=-0.1730, P = 0.0024) and STAD (R=-0.1774, P = 0.0128) exhibited a negative correlation with MSI (Fig. 9D).

MAGEA10 response to chemotherapy, drug sensitivity analysis, and correlation with immunotherapy. (A) The relationship between MAGEA10 expression levels and response to chemotherapy treatment, and the predictive efficacy of MAGEA10 levels on chemotherapy response. (B) Drug sensitivity analysis of MAGEA10. (C) Correlation between MAGEA10 expression and TMB in pan-cancer. (D) Correlation between MAGEA10 expression and MSI in pan-cancer.

The expression, prognosis, and function of MAGE-A10 in gastric cancer

Based on prior research, the gene MAGE-A10 was significantly expressed in stomach cancer. Survival analysis demonstrated a strong correlation between MAGE-A10 expression and the overall survival (OS) (p = 6.6e-3), disease-specific survival (DSS) (p = 3.9e-4), progression-free survival (PFS) (p = 3.4e-3), and disease-free survival (DFS) (p = 1.4e-3), and these correlations were also found to be significant in the analysis of TMB and MSI. This was further validated in the GSE54129 dataset (n = 132) and TCGA-STAD dataset (n = 405). In comparison with normal tissue, the mRNA expression levels of MAGE-A10 were higher in STAD, with the respective areas under the ROC curve being 0.648 and 0.680, indicating that MAGE-A10 had significant diagnostic efficacy in STAD (p < 0.05, Fig. 10A-B). To comprehensively evaluate the relationship between high MAGE-A10 expression and the prognosis of STAD patients, we assessed the prognostic association of MAGE-A10 in stomach cancer using the Kaplan-Meier Plotter (Fig. 10C). The study results showed that when MAGE-A10 expression was upregulated, STAD patients had a shorter OS (logrank p = 1.34e-14) and post-progression survival (PPS) outcomes (logrank P = 5.7e − 13). Following this, GSEA enrichment analysis of MAGE-A10 in stomach cancer was conducted based on the TCGA-STAD database. The results, as shown in Fig. 10D, indicated a close association between the high expression of MAGE-A10 and binding to histone deacetylases (NES = 2.037, p.adjust = 0.018).

Knockdown of MAGE-A10 inhibits the proliferation, migration, and invasion of gastric cancer cells

To validate the role of MAGE-A10 in gastric cancer cells, we first analyzed CCLE data and observed that MAGE-A10 is among the top ten expressed cell lines in gastric cancer, as visualized in Fig. 11A. Due to the unavailability of these high-expression cell lines, we chose the commonly used HGC-27 cell line, which has relatively high expression, for subsequent experiments. Additionally, we verified the expression of MAGE-A10 in other gastric cancer cell lines (AGC, MGC-803, and MKN-45) and normal gastric cell line (GES-1) using RT-PCR and Western blot, as shown in the supplementary Fig. 3.Next, we transfected HGC-27 cells with three siRNA knockdown vectors and performed RT-PCR and Western blot analyses. As shown in Fig. 11B-D, the mRNA and protein expression levels in the transfected groups were significantly reduced compared to the control group, with si-MAGE-A10#3 exhibiting the highest knockdown efficiency, thus it was selected for further experiments. The impact of MAGE-A10 on the proliferation of gastric cancer cells was validated by CCK-8 assay (Fig. 11E) and colony formation assay (Fig. 11F, J). Results showed that MAGE-A10 knockdown significantly reduced the proliferation capacity of gastric cancer cells, which was also supported by the colony formation assay.Subsequently, we tested the migration and invasion abilities of cells after MAGE-A10 knockdown using cell scratch assay and chamber invasion assay. Results indicated that the migration and invasion abilities of HGC-27 cells were significantly weakened after MAGE-A10 knockdown (Fig. 11G-H and K-L). Finally, we examined the expression of metastasis-related proteins after MAGE-A10 knockdown by Western blot. As shown in Fig. 10I, when MAGE-A10 expression was suppressed, E-cadherin levels increased, N-cadherin levels decreased, and vimentin expression remained unchanged.

Knockdown of MAGEA10 inhibits the proliferation, migration, and invasion of HGC-27 gastric cancer cells in vitro. (A) Expression levels of MAGEA10 in different STAD cell lines. (B) RT-PCR validation of MAGEA10 knockdown efficiency in HGC-27 cells. (C) Western blot validation of MAGEA10 knockdown efficiency in HGC-27 cells. (D) Statistical analysis of grayscale values from three repeated Western blot experiments. (E) CCK-8 assay to analyze the effect of MAGEA10 knockdown on cell proliferation. (F-H) Analysis of the effects of MAGEA10 knockdown on cell proliferation, migration, and invasion through colony formation, cell scratch, and chamber invasion assays. (I) Western blotting to detect the effect of MAGEA10 knockdown on metastasis-related proteins. (J-L) Statistical analysis of results from three independent experiments of colony formation, cell scratch, and chamber invasion assays. Symbols ns, *, **, ***, and **** indicate not significant, P < 0.05, P < 0.01, P < 0.001, and P < 0.0001, respectively.

Discussion

MAGE-A10 was a member of the cancer/testis antigens (CTAs) family, aberrantly expressed in various cancers and considered a potential target for immunotherapy20. Recent studies reported T-cell receptor (TCR) engineering targeting MAGE-A10 antigens, where moderate engineering modifications produced clinically safe and high-affinity enhanced TCR T-cell therapies44. Additionally, in a phase I clinical trial for advanced non-small cell lung cancer (NSCLC), preliminary clinical trial results of ADP-A2M10 specific peptide-enhanced affinity receptor (SPEAR) T-cell therapy targeting MAGE-A10 positive patients demonstrated its safety and potential efficacy45. In summary, research on MAGE-A10 as an immunotherapy target was actively ongoing.

In our study, we first analyzed MAGE-A10 expression in normal tissues using the HPA database and found high mRNA and protein levels in the placenta and testis, localized to the nucleus and cytoplasm.A pan-cancer analysis using TCGA and GTEx showed that MAGE-A10 was upregulated in most tumors (such as LUAD, LUSC, BLCA, CHOL, LIHC, and STES), consistent with previous studies.COX regression analysis revealed that high MAGE-A10 expression in STAD, STES, KIRP, and LIHC was linked to reduced OS, DSS, DFI, and PFI.In KIPAN and KIRC, high MAGE-A10 expression was also associated with reduced OS, DSS, and PFI.These findings suggest that MAGE-A10 may serve as a reliable biomarker.

Gene sequence mutations contributed to tumor development. Acha-Sagredo A et al. highlighted the need to consider somatic variations in early cancer detection and prevention46. Therefore, we analyzed MAGE-A10 mutations in 45 cancer types and identified mutations in 31, including STAD. We then examined the relationship between MAGE-A10 copy number variations (CNAs) and mRNA expression across cancers, finding significant differences in seven types, including STAD. This suggested that MAGE-A10 expression might be regulated by a complex genetic background, with CNAs as potential key factors. Further analysis showed frequent mutations in 15 genes, such as FLG, RYR2, CSMD1, RYR1, and DNAH3, in both high and low MAGE-A10 expression groups in STAD. These mutations may relate to MAGE-A10 regulation and cancer development, offering new insights into STAD mechanisms. DNA methylation was an epigenetic modification that could be stably inherited without altering the DNA sequence. Disruption of DNA methylation control mechanisms led to various diseases, including cancer. Cancer cells typically exhibited global hypomethylation and hypermethylation of specific CpG islands, providing a molecular basis for cancer classification47,48. Considering its role in cancer progression and diagnosis, we first analyzed MAGE-A10 methylation in cancers and normal tissues. MAGE-A10 showed hypomethylation in 20 cancers, including STAD, and hypermethylation in CHOL and THYM. This indicated heterogeneous methylation patterns of MAGE-A10 across cancers, potentially influencing cancer cell behavior. Methylation of CpG islands in promoter regions generally silences gene expression49. However, in CHOL, PRAD, TGCT, and THCA, MAGE-A10 gene expression levels were positively correlated with DNA methylation levels. We speculated that this might have been similar to the findings of Harris et al., where DNA methylation could activate gene expression50. This suggests a more complex mechanism behind DNA methylation’s effect on MAGE-A10 expression, warranting further study. We then assessed how methylation at MAGE-A10 CpG sites affects prognosis across cancers, identifying eight sites (e.g., cg19964192) linked to outcomes. Specifically, cg19964192 methylation correlated positively with prognosis in ACC, CESC, LIHC, SARC, SKCM, UCEC, and UVM, but negatively in PAAD.

We conducted GO and KEGG enrichment analyses to explore the molecular mechanisms of MAGE-A10 in cancer. KEGG analysis suggested that MAGE-A10 might be involved in transcriptional dysregulation, melanogenesis, tyrosine metabolism, antigen processing, ATP-dependent chromatin remodeling, cell adhesion, and primary immunodeficiency. The GO enrichment analysis suggested that MAGE-A10 was primarily associated with histone deacetylase binding. These results implied that MAGE-A10 might play a role in cancer development by influencing gene expression regulation, cell differentiation, and immune responses. Although there were currently few studies on the function of MAGE-A10, further experimental validation of these bioinformatics predictions could help us better understand the specific role of MAGE-A10 in cancer development. This would provide an important theoretical basis for developing new cancer treatment strategies.

Immune checkpoint blockade (ICB) therapy, by blocking inhibitory receptors such as CTLA4 and PD1 on T cells, restored anti-tumor immune responses and achieved success in treating various cancers51,52. MAGE-A10 was associated with levels of M2-type tumor-associated macrophages (M2-TAM), neutrophils, and cancer-associated fibroblasts (CAF) in several cancers. We speculated that high expression of MAGE-A10 might have promoted immune evasion and treatment resistance in these cancers by promoting the infiltration of M2-TAM and neutrophils and leading to cytotoxic T lymphocyte (CTL) dysfunction. Computational models and public datasets have become valuable tools for predicting immunotherapy response and guiding personalized treatment strategies29,53.When comparing the differences between MAGE-A10 and other standardized biomarkers in predicting the efficacy of ICB therapy, we found that MAGE-A10 had an AUC value exceeding 0.5 in eight immunotherapy cohorts and showed more significant performance in predicting the efficacy of immunotherapy in patients with glioma and melanoma. MAGE-A10 expression positively correlated with CTL dysfunction in several malignancies, including acute myeloid leukemia (AML) and bladder cancer, but displayed an inverse relationship in melanoma, ovarian cancer, lung adenocarcinoma (LUAD), and lung squamous carcinoma (LUSC). In the dataset GSE1427-AML, high expression of MAGE-A10 was associated with increased CTL infiltration, extending the survival and improving the clinical outcomes of these patients. In contrast, in GSE13507-bladder cancer, low MAGE-A10 expression correlated with reduced CTL infiltration but was paradoxically associated with improved survival. These findings suggest a context-dependent role for MAGE-A10 in bladder cancer, warranting further mechanistic investigation. We next performed a drug sensitivity analysis to assess the clinical implications of MAGE-A10 expression. In breast and colorectal cancers, low MAGE-A10 expression was associated with reduced chemotherapy resistance. Conversely, in ovarian cancer, low MAGE-A10 expression correlated with reduced chemotherapy benefit. In glioblastoma multiforme, the expression of MAGE-A10 did not show a significant difference in chemotherapy response. Furthermore, we found that high expression of MAGE-A10 was negatively correlated with the sensitivity to 21 drugs. Notably, high MAGE-A10 expression conferred increased resistance to key chemotherapeutics, including Floxuridine, 6-Mercaptopurine, Intedanib, Vinorelbine, Fluorouracil, Idarubicin, Mitoxantrone, and Methotrexate. These findings offer a rationale for developing MAGE-A10-targeted therapeutic strategies in selected cancers. Finally, we examined associations between MAGE-A10 expression, tumor mutational burden (TMB), and microsatellite instability (MSI) across cancer types. Collectively, our results support MAGE-A10 as a potential predictive and prognostic biomarker for immunotherapy.

Gastric cancer is one of the most common malignancies worldwide. Due to the lack of early symptoms and regular screening, most patients are diagnosed at an advanced stage. Improving early diagnosis rates, optimizing treatment plans, and overcoming resistance to immune checkpoint inhibitors are future research directions for gastric cancer treatment54.Previous related studies indicated that MAGE-A10 might be an important molecular driver in the development of gastric cancer. Therefore, in this study, we comprehensively investigated the expression pattern, diagnostic potential, prognostic significance, and functional role of MAGE-A10 in gastric cancer. Firstly, Analysis of publicly available datasets (GSE54129 and TCGA-STAD) revealed significantly elevated MAGE-A10 expression in gastric cancer tissues compared to adjacent normal counterparts. Receiver operating characteristic (ROC) curve analysis demonstrated robust diagnostic discrimination, supporting the utility of MAGE-A10 as a potential biomarker for early detection. Kaplan-Meier survival analysis further indicated that high MAGE-A10 expression was significantly associated with reduced overall survival (OS) and progression-free survival (PFS), aligning with previous observations and highlighting its prognostic relevance in gastric cancer. Additionally, Gene set enrichment analysis (GSEA) revealed a strong association between MAGE-A10 expression and histone deacetylase (HDAC) binding, implicating epigenetic modulation as a potential mechanism underlying its oncogenic effects. Consistent with these findings, prior research by Badie et al. reported aberrant HDAC expression in gastric cancer, suggesting a possible cooperative role in tumor progression55. Finally, To experimentally validate the functional role of MAGE-A10, we performed siRNA-mediated knockdown in the HGC-27 gastric cancer cell line. Silencing MAGE-A10 significantly suppressed cellular proliferation, migration, and invasion. Western blot analysis suggested that these phenotypic effects may be partially mediated through alterations in cell adhesion molecule activity. KEGG pathway analysis of MAGE-A10-associated genes and proteins indicated enrichment in cell adhesion molecule pathways. These molecules—comprising integrins, selectins, cadherins, and members of the immunoglobulin superfamily (IgSF)—are essential mediators of intercellular adhesion, signal transduction, and migratory behavior. Dysregulation within this network can perturb immune cell trafficking and effector function within the tumor microenvironment, ultimately influencing anti-tumor immunity56. Collectively, these findings underscore the therapeutic potential of MAGE-A10 and provide a mechanistic basis for its targeting in future gastric cancer treatment strategies. Despite these promising findings, our study has several limitations. While MAGE-A10 appears to be involved in shaping the immune microenvironment, its precise relationship with immune infiltration remains insufficiently characterized and lacks experimental validation against established immunological markers. Moreover, although our data suggest that MAGE-A10 may modulate cadherin-mediated signaling to influence tumor cell behavior, the exact regulatory mechanisms remain to be elucidated. Future studies employing in vivo models and mechanistic assays are warranted to define these pathways more precisely.

Conclusion

In summary, MAGE-A10 is a potential tumor prognostic biomarker and immunotherapy target. We identified the expression, prognosis, and function of MAGE-A10 in gastric cancer, finding that it stimulates the proliferation, migration, and invasion of gastric cancer cells in vitro and might influence gastric cancer invasion and metastasis through the dysregulation of cadherins in cell adhesion molecules (CAMs). These findings provide new insights into the role of MAGE-A10 in gastric cancer and support further research on its potential as a therapeutic target and diagnostic marker.

Data availability

The datasets used and/or analysed during the current study available from the corresponding author on reasonable request.

References

Siegel, R. L., Miller, K. D., Wagle, N. S. & Jemal, A. Cancer statistics, 2023. CA Cancer J. Clin. 73, 17–48. https://doi.org/10.3322/caac.21763 (2023).

Cao, W., Chen, H. D., Yu, Y. W., Li, N. & Chen, W. Q. Changing profiles of cancer burden worldwide and in china: a secondary analysis of the global cancer statistics 2020. Chin. Med. J. 134, 783–791. https://doi.org/10.1097/cm9.0000000000001474 (2021).

Xia, C. et al. Cancer statistics in China and united states, 2022: profiles, trends, and determinants. Chin. Med. J. 135, 584–590. https://doi.org/10.1097/cm9.0000000000002108 (2022).

Kraehenbuehl, L., Weng, C. H., Eghbali, S., Wolchok, J. D. & Merghoub, T. Enhancing immunotherapy in cancer by targeting emerging Immunomodulatory pathways. Nat. Rev. Clin. Oncol. 19, 37–50. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41571-021-00552-7 (2022).

Zhu, S. et al. Combination strategies to maximize the benefits of cancer immunotherapy. J. Hematol. Oncol. 14 https://doi.org/10.1186/s13045-021-01164-5 (2021).

Rui, R., Zhou, L. & He, S. Cancer immunotherapies: advances and bottlenecks. Front. Immunol. 14, 1212476. https://doi.org/10.3389/fimmu.2023.1212476 (2023).

Lybaert, L. et al. Challenges in neoantigen-directed therapeutics. Cancer Cell. 41, 15–40. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ccell.2022.10.013 (2023).

Khemlina, G., Ikeda, S. & Kurzrock, R. The biology of hepatocellular carcinoma: implications for genomic and immune therapies. Mol. Cancer. 16 https://doi.org/10.1186/s12943-017-0712-x (2017).

Darvin, P., Toor, S. M., Nair, S., Elkord, E. & V. & Immune checkpoint inhibitors: recent progress and potential biomarkers. Exp. Mol. Med. 50, 1–11. https://doi.org/10.1038/s12276-018-0191-1 (2018).

van der Bruggen, P. et al. A gene encoding an antigen recognized by cytolytic T lymphocytes on a human melanoma. Sci. (New York N Y). 254, 1643–1647. https://doi.org/10.1126/science.1840703 (1991).

Chomez, P. et al. An overview of the MAGE gene family with the identification of all human members of the family. Cancer Res. 61, 5544–5551 (2001).

Simpson, A. J., Caballero, O. L., Jungbluth, A., Chen, Y. T. & Old, L. J. Cancer/testis antigens, gametogenesis and cancer. Nat. Rev. Cancer. 5, 615–625. https://doi.org/10.1038/nrc1669 (2005).

Jin, S. et al. Cancer/testis antigens (CTAs) expression in resected lung cancer. Onco.Targets Therapy. 11, 4491–4499. https://doi.org/10.2147/ott.S159491 (2018).

Meek, D. W. & Marcar, L. MAGE-A antigens as targets in tumour therapy. Cancer Lett. 324, 126–132. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.canlet.2012.05.011 (2012).

Schultz-Thater, E. et al. MAGE-A10 is a nuclear protein frequently expressed in high percentages of tumor cells in lung, skin and urothelial malignancies. Int. J. Cancer. 129, 1137–1148. https://doi.org/10.1002/ijc.25777 (2011).

Mengus, C. et al. MAGE-A10 cancer/testis antigen is highly expressed in high-grade non-muscle-invasive bladder carcinomas. Int. J. Cancer. 132, 2459–2463. https://doi.org/10.1002/ijc.27914 (2013).

Suzuki, S. et al. MAGE-A protein and MAGE-A10 gene expressions in liver metastasis in patients with stomach cancer. Br. J. Cancer. 99, 350–356. https://doi.org/10.1038/sj.bjc.6604476 (2008).

Fujiya, K. et al. MAGEA10 expression is a predictive marker of early hepatic recurrence after curative gastrectomy for gastric and gastroesophageal junction cancer. Gastric Cancer: Official J. Int. Gastric Cancer Association Japanese Gastric Cancer Association. 24, 341–351. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10120-020-01123-y (2021).

Qin, H. et al. Immunization with a multi-antigen targeted DNA vaccine eliminates chemoresistant pancreatic cancer by disrupting tumor-stromal cell crosstalk. J. Translational Med. 21, 702. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12967-023-04519-3 (2023).

Lisica Šikić, N. et al. MAGE-A10 protein expression in advanced high grade serous ovarian cancer is associated with resistance to First-Line Platinum-Based chemotherapy. Cancers 15 https://doi.org/10.3390/cancers15194697 (2023).

Uhlen, M. et al. A pathology atlas of the human cancer transcriptome. Sci. (New York N Y). 357 https://doi.org/10.1126/science.aan2507 (2017).

Chandrashekar, D. et al. (ed, S.) UALCAN: A portal for facilitating tumor subgroup gene expression and survival analyses. Neoplasia (New York N Y) 19 649–658 https://doi.org/10.1016/j.neo.2017.05.002 (2017).

Modhukur, V. et al. MethSurv: a web tool to perform multivariable survival analysis using DNA methylation data. Epigenomics 10, 277–288. https://doi.org/10.2217/epi-2017-0118 (2018).

Tang, Z., Kang, B., Li, C., Chen, T. & Zhang, Z. GEPIA2: an enhanced web server for large-scale expression profiling and interactive analysis. Nucleic Acids Res. 47, W556–w560. https://doi.org/10.1093/nar/gkz430 (2019).

Warde-Farley, D. et al. The genemania prediction server: biological network integration for gene prioritization and predicting gene function. Nucleic Acids Res. 38, W214–220. https://doi.org/10.1093/nar/gkq537 (2010).

Kanehisa, M. Toward Understanding the origin and evolution of cellular organisms. Protein Science: Publication Protein Soc. 28, 1947–1951. https://doi.org/10.1002/pro.3715 (2019).

Kanehisa, M., Furumichi, M., Sato, Y., Matsuura, Y. & Ishiguro-Watanabe, M. KEGG: biological systems database as a model of the real world. Nucleic Acids Res. 53, D672–d677. https://doi.org/10.1093/nar/gkae909 (2025).

Li, T. et al. TIMER2.0 for analysis of tumor-infiltrating immune cells. Nucleic Acids Res. 48, W509–w514. https://doi.org/10.1093/nar/gkaa407 (2020).

Fu, J. et al. Large-scale public data reuse to model immunotherapy response and resistance. Genome Med. 12 https://doi.org/10.1186/s13073-020-0721-z (2020).

Jiang, P. et al. Signatures of T cell dysfunction and exclusion predict cancer immunotherapy response. Nat. Med. 24, 1550–1558. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41591-018-0136-1 (2018).

Fekete, J. T. & Győrffy, B. ROCplot.org: validating predictive biomarkers of chemotherapy/hormonal therapy/anti-HER2 therapy using transcriptomic data of 3,104 breast cancer patients. Int. J. Cancer. 145, 3140–3151. https://doi.org/10.1002/ijc.32369 (2019).

Reinhold, W. C. et al. CellMiner: a web-based suite of genomic and Pharmacologic tools to explore transcript and drug patterns in the NCI-60 cell line set. Cancer Res. 72, 3499–3511. https://doi.org/10.1158/0008-5472.Can-12-1370 (2012).

Xiao, Y. & Yu, D. Tumor microenvironment as a therapeutic target in cancer. Pharmacol. Ther. 221 https://doi.org/10.1016/j.pharmthera.2020.107753 (2021).

Lan, J. et al. M2 Macrophage-Derived exosomes promote cell migration and invasion in colon cancer. Cancer Res. 79, 146–158. https://doi.org/10.1158/0008-5472.Can-18-0014 (2019).

Zhang, Y. et al. OTUD5-mediated deubiquitination of YAP in macrophage promotes M2 phenotype polarization and favors triple-negative breast cancer progression. Cancer Lett. 504, 104–115. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.canlet.2021.02.003 (2021).

Mantovani, A., Marchesi, F., Malesci, A., Laghi, L. & Allavena, P. Tumour-associated macrophages as treatment targets in oncology. Nat. Rev. Clin. Oncol. 14, 399–416. https://doi.org/10.1038/nrclinonc.2016.217 (2017).

Shimasaki, N., Jain, A. & Campana, D. NK cells for cancer immunotherapy. Nat. Rev. Drug Discov. 19, 200–218. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41573-019-0052-1 (2020).

Zhang, H., Yang, L., Wang, T. & Li, Z. NK cell-based tumor immunotherapy. Bioactive Mater. 31, 63–86. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.bioactmat.2023.08.001 (2024).

Mao, X. et al. Crosstalk between cancer-associated fibroblasts and immune cells in the tumor microenvironment: new findings and future perspectives. Mol. Cancer. 20, 131. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12943-021-01428-1 (2021).

Morad, G., Helmink, B. A., Sharma, P. & Wargo, J. A. Hallmarks of response, resistance, and toxicity to immune checkpoint Blockade. Cell 184, 5309–5337. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.cell.2021.09.020 (2021).

Farhood, B., Najafi, M. & Mortezaee, K. CD8(+) cytotoxic T lymphocytes in cancer immunotherapy: A review. J. Cell. Physiol. 234, 8509–8521. https://doi.org/10.1002/jcp.27782 (2019).

Song, J. et al. Pan-cancer analysis reveals RIPK2 predicts prognosis and promotes immune therapy resistance via triggering cytotoxic T lymphocytes dysfunction. Mol. Med. (Cambridge Mass). 28, 47. https://doi.org/10.1186/s10020-022-00475-8 (2022).

Duffy, M. J. & Crown, J. Biomarkers for predicting response to immunotherapy with immune checkpoint inhibitors in cancer patients. Clin. Chem. 65, 1228–1238. https://doi.org/10.1373/clinchem.2019.303644 (2019).

Simister, P. C., Border, E. C., Vieira, J. F. & Pumphrey, N. J. Structural insights into engineering a T-cell receptor targeting MAGE-A10 with higher affinity and specificity for cancer immunotherapy. J. Immunother. Cancer. 10 https://doi.org/10.1136/jitc-2022-004600 (2022).

Blumenschein, G. R. et al. Phase I clinical trial evaluating the safety and efficacy of ADP-A2M10 SPEAR T cells in patients with MAGE-A10 + advanced non-small cell lung cancer. J. Immunother. Cancer. 10 https://doi.org/10.1136/jitc-2021-003581 (2022).

Acha-Sagredo, A., Ganguli, P. & Ciccarelli, F. D. Somatic variation in normal tissues: friend or foe of cancer early detection? Ann. Oncol. 33, 1239–1249. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.annonc.2022.09.156 (2022).

Nishiyama, A. & Nakanishi, M. Navigating the DNA methylation landscape of cancer. Trends Genet. 37, 1012–1027. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.tig.2021.05.002 (2021).

Papanicolau-Sengos, A. & Aldape, K. D. N. A. Methylation profiling: an emerging paradigm for cancer diagnosis. Annu. Rev. Pathol. 17, 295–321. https://doi.org/10.1146/annurev-pathol-042220-022304 (2022).

Issa, J. P. CpG Island methylator phenotype in cancer. Nat. Rev. Cancer. 4, 988–993. https://doi.org/10.1038/nrc1507 (2004).

Harris, C. J. et al. A DNA methylation reader complex that enhances gene transcription. Sci. (New York N Y). 362, 1182–1186. https://doi.org/10.1126/science.aar7854 (2018).

Kubli, S. P., Berger, T., Araujo, D. V., Siu, L. L. & Mak, T. W. Beyond immune checkpoint blockade: emerging immunological strategies. Nat. Rev. Drug Discovery. 20, 899–919. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41573-021-00155-y (2021).

Budimir, N., Thomas, G. D., Dolina, J. S. & Salek-Ardakani, S. Reversing T-cell exhaustion in cancer: lessons learned from PD-1/PD-L1 immune checkpoint Blockade. Cancer Immunol. Res. 10, 146–153. https://doi.org/10.1158/2326-6066.Cir-21-0515 (2022).

Masoudi-Sobhanzadeh, Y., Omidi, Y., Amanlou, M. & Masoudi-Nejad, A. Drug databases and their contributions to drug repurposing. Genomics 112, 1087–1095. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ygeno.2019.06.021 (2020).

Guan, W. L., He, Y. & Xu, R. H. Gastric cancer treatment: recent progress and future perspectives. J. Hematol. Oncol. 16 https://doi.org/10.1186/s13045-023-01451-3 (2023).

Badie, A., Gaiddon, C. & Mellitzer, G. Histone deacetylase functions in gastric cancer. Therapeutic Target? Cancers. 14 https://doi.org/10.3390/cancers14215472 (2022).

Harjunpää, H., Asens, L., Guenther, M., Fagerholm, S. C. & C. & Cell adhesion molecules and their roles and regulation in the immune and tumor microenvironment. Front. Immunol. 10 https://doi.org/10.3389/fimmu.2019.01078 (2019).

Acknowledgements

We sincerely thank the public databases for providing us with data, as well as RStudio, BioRender and Sangerbox.

Funding

This study was supported by the National Natural Science Foundation of China (No.82260716, No.82060663), and the Key Research and Development Project in the Social Field of Ningxia Hui Autonomous Region (No. 2023BEG02010).

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

YY, JC, and TL conceived the original research project. BW and MY collected, analyzed, and visualized the data, and interpreted the data together with YY. YY, BW, MY, WL, AW, and ZL conducted the cell experiments and statistical analysis. YY, BW, and MY wrote the first draft of the manuscript, which was edited and revised by JC and TL. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Corresponding authors

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Ethical approval

The data of patients are from public database. Ethical approval is not applicable for this article. This article does not contain any studies with human or animal subjects.

Additional information

Publisher’s note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Supplementary Information

Below is the link to the electronic supplementary material.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if you modified the licensed material. You do not have permission under this licence to share adapted material derived from this article or parts of it. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Yin, Y., Wang, B., Yang, M. et al. Comprehensive analysis of MAGE-A10 in pan-cancer and its validation in gastric cancer. Sci Rep 15, 32077 (2025). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-17987-y

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-17987-y