Abstract

Rosuvastatin can block human ether-a-go-go related gene (hERG) currents and prolong the corrected QT (QTc) interval, but this effect has not been confirmed in the population. This study compared the changes of QTc interval between populations receiving atorvastatin and rosuvastatin, explained the effect of rosuvastatin on QTc interval, and the correlation between rosuvastatin and QT prolongation. The QTc interval decreased by 0.83 ms from baseline in atorvastatin group and increased by 6.57 ms in rosuvastatin group. More patients in the rosuvastatin group had an increased QTc interval (62.7% vs. 46.6%, p< 0.001). Rosuvastatin increased the risk of newly emerged QT prolongation by 42% (95% CI 1.10–1.85, p = 0.008). But there was no correlation between rosuvastatin and severe QT prolongation (RR 1.23, 95% CI 0.74–2.06, p = 0.426). In conclusion, rosuvastatin exhibits a modest adverse effect on the QTc interval. Rosuvastatin monotherapy does not appear to increase the risk of arrhythmia. But this study did not assess the usage of rosuvastatin with other QT-prolonging drugs, the potential for an additive effect should be considered when combining rosuvastatin with other QT-prolonging drugs.

Trial registration: ChiCTR2400092701 (21/11/2024)

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

QT prolongation predisposes patients to the development of torsades de pointes (TdP), which can cause cardiac arrest and sudden cardiac death. It is considered to be a surrogate marker of proarrhythmia risk. In patients with congenital long QT syndrome (LQTS), the risk of TdP increases by 5–7% for every 10ms increase in the corrected QT (QTc) interval, and 2–3 fold when the QTc interval exceeds 500ms1,2. Patients with acquired LQTS induced by QT-prolonging drugs have a 2.5–2.7 fold increased risk of cardiac arrest and sudden cardiac death, and concurrent use of two or more QT-prolonging drugs increases the risk by over fourfold3,4.

Drugs are among the most common causes of acquired LQTS. In light of the potentially fatal outcome of drug-induced QT prolongation, non-clinical (ICH S7B) and clinical (ICH E14) regulatory guidance from the International Conference on Harmonization have emphasized the importance of QT liability testing5,6. Prolonging the QTc interval is a major safety concern in the development of new drugs. QT liability and torsadogenic potential have become common reasons for the withdrawal of many drugs from the market7. Several organizations and institutions are working to provide up-to-date QT-prolonging drug lists7,8. Nevertheless, the risk of QT prolongation for many commonly prescribed medications remains uncertain9.

Rosuvastatin is a fully synthetic-selective HMG-CoA reductase inhibitor. Among the existing statins, it has the largest reduction in low-density lipoprotein cholesterol (LDL-C) and has been proven to be the most effective agent for reducing cardiovascular risk10. Rosuvastatin is the third most used statin in the US, with approximately 29 million prescriptions filled annually11. In China, it is second only to atorvastatin, accounting for 24.6% of the market share. Although the safety and tolerability of rosuvastatin have been confirmed by previous studies10,11,12,13,14, some animal and in vitro cell experiments in recent years have found that rosuvastatin can block human ether-a-go-go related gene (hERG) potassium channels and prolong the QTc interval, raising concerns about the safety of rosuvastatin15,16.

A case-control study based on real-world data showed that the proportion of patients who use rosuvastatin in the QT prolongation group was higher than that in the control group (2.7% vs. 0.9%), and rosuvastatin was associated with QT prolongation (OR 1.30, 95% CI 1.21–1.39). However, this small sample, retrospective, cohort study did not find the association between rosuvastatin and QT prolongation to be statistically significant (p = 0.065)9. In this context, more research about rosuvastatin and QT prolongation is needed .

This study aimed to compare the changes of QTc interval between patients receiving atorvastatin and rosuvastatin, explore the effect of rosuvastatin on QTc interval and explain the correlation between rosuvastatin and QT prolongation.

Methods

Study design and setting

This study was a pilot parallel, single blind, randomized controlled trial, which was conducted in accordance with the ethical standards described in the Declaration of Helsinki and was approved by the Ethics Committee of Ningbo Medical Centre Lihuili Hospital (KY2023SL211). Informed consent was obtained from all participants and/or their legal guardians. This study was retrospectively registered in Chinese Clinical Trials Registry (ChiCTR2400092701) on November 21, 2024. We followed the Consolidated Standards of Reporting Trials (CONSORT) extension for the Pilot and Feasibility Trials Statement. We also followed the recommendations of trial protocol regulations of the World Health Organization.

Selection of participants

Patients with suspected coronary artery disease (CAD) hospitalized in the Department of Cardiology, Ningbo Medical Centre Lihuili Hospital from August 2023 to May 2024 were consecutively enrolled. Exclusion criteria were: (1) taking statins within 3 months prior to admission; (2) taking known QT-prolonging drugs within 3 months prior to admission; (3) history of TdP or sudden cardiac death; and (4) severe liver and kidney dysfunction, myopathy, pregnancy, breastfeeding, or statin allergy.

Patients with the following conditions were eliminated during follow-up: (1) discontinued statin or changed statin type; (2) failed to complete the ECG as required; (3) severe arrhythmias unrelated to QT prolongation, such as atrial flutter, atrial fibrillation with fast ventricular rate, atrial tachycardia, supraventricular tachycardia, grade II type 2 and III atrioventricular block, sinus arrest, and significant sinus bradycardia rate < 50 beats per minute (bpm); (4) pacemaker implantation or cardiac radiofrequency ablation; (5) acute heart failure; (6) acute myocardial infarction; (7) severe electrolyte disturbance (serum potassium < 3.0 mmol/L or > 5.5 mmol/L; serum calcium, sodium, and magnesium deviated from the normal range); and (8) incomplete data.

Methods of measurement and interventions

Patients were screened, enrolled, and received the intervention by well-trained cardiologists following standardized procedures. All patients underwent the necessary examinations and treatments in accordance with clinical norms and national guidelines17,18,19.

Patients were grouped by random number table method with an allocation ratio of 1:1, using a random number table to generate 1000 random numbers. After the subjects were enrolled, they obtained the corresponding random number according to their serial number. Those with odd random numbers were included in the experimental group and those with even numbers were included in the control group. The experimental group received a prescribed dose of rosuvastatin (10 mg) and the control group received a prescribed dose of atorvastatin (20 mg) at 8 p.m. every day. To conceal randomization allocation, the random number was read just prior to the first statin administration.

All patients completed the standard 10-s 12-lead ECG on the day of admission. After receiving two consecutive doses of statins, ECGs were followed up again at 8–12 a.m. on the third day of admission. The QT interval was measured from the first wave of the QRS complex to the end of the T-wave which was determined by the tangent method. The QTc interval was automatically calculated using the NaLong aECG Acquisitor digital electrocardiograph system (Version 3.0) by the Bazett’s formula, and verified by at least one ECG expert. Patients and doctors could recognize the type of statins patients received, but this information was hidden from ECG experts.

Demographic characteristics and clinical data, including age, sex, height, weight, smoking, drinking, and comorbidities (hypertension, diabetes, atrial fibrillation, and chronic heart failure) were collected by trained resident physicians. Blood samples were collected by nurses before 8 a.m. on the day after admission and sent to the biochemical laboratory for analysis. Echocardiography was performed at the ultrasound diagnostic center.

Outcome measures

The primary outcome was newly emerged QT prolongation. QT prolongation was defined as a QTc interval > 450 ms for males and 470 ms for females20. Patients with normal QTc interval at baseline but with QT prolongation after statin were regarded as newly emerged QT prolongation. The secondary outcomes were increased QTc interval and severe QT prolongation. Increased QTc interval was defined as the follow-up QTc interval being longer than the baseline QTc interval. Severe QT prolongation was defined as either a follow-up QTc interval exceeding 500 ms or an increase in QTc interval exceeding 60 ms from the baseline21.

Sample size estimation

We based the sample size for statistical power on the primary outcome. A previous small sample study showed that rosuvastatin increased the risk of QT prolongation by 2.5 times (HR 2.54, 95% CI 0.94–6.80)9. We hypothesized that rosuvastatin increased the risk of newly emerged QT prolongation by 12.5% and atorvastatin by 5%. The total sample size required to detect this difference in event rates with a two-tailed alpha level of 0.05 and 80% power is 43822. We increased our sample size to 500 to take into account a projected 10% elimination during follow-up.

Statistical analysis

Categorical variables were represented as numbers (%) and analyzed using the chi-square test or Fisher’s exact test. Continuous variables were represented as mean ± S.D. and analyzed using Student’s t-test or Mann - Whitney U test. Logbinomial regression was used to estimate the relative risk (RR) of rosuvastatin with end-point events. Logistic regression analysis was used to investigate the independent correlation between rosuvastatin and QT prolongation after correcting confounding factors. Data analysis was performed using IBM SPSS Statistics, Version 25.0 (Armonk, NY, USA), with a p value of < 0.05 considered significant.

Results

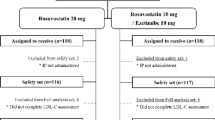

A total of 522 patients fulfilled the research criteria and were classified as research subjects. 466 patients completed follow-up and were included in the analysis, 228 in the rosuvastatin group and 238 in the atorvastatin group. The CONSORT Flow-diagram (Fig. 1) describes the flow of patients through the trial.

The general characteristics of the study population are summarized in Table 1. Compared with the rosuvastatin group, more patients in the atorvastatin group received beta-blockers (17.6% vs. 11.0%, p = 0.04). There were no significant differences in the other characteristics between the two groups (p > 0.05).

The paired Student’s t-test revealed no significant change in the QTc interval for the atorvastatin group post-therapy (430.34 ms vs. 429.51 ms, p = 0.563), whereas the rosuvastatin group exhibited an increase in the QTc interval (425.85 ms vs. 432.42 ms, p < 0.001).

ALT, alanine transaminase; AST, aspartate transaminase; LDL-C, low-density lipoprotein cholesterol; HDL-C, high-density lipoprotein cholesterol; ACEI, angiotensin-converting enzyme inhibitor; ARB, angiotensin-receptor blocker; ARNI, angiotensin receptor-neprilysin inhibitor; SGLT-2i, sodium-dependent glucose transporter 2; LVDs, left ventricular end systolic diameter; LVDd, left ventricular end diastolic diameter; IVST, interventricular septal thickness; LVPW, left ventricular posterior wall.

The changes in electrocardiographic parameters after therapy are shown in Table 2. The heart rate decreased by 4.73 ± 10.32 bpm from baseline in the atorvastatin group and 3.70 ± 9.50 bpm in the rosuvastatin group (p = 0.261). The QTc interval of the atorvastatin group was decreased by 0.83 ± 22.07 ms, while that of the rosuvastatin group increased by 6.57 ± 20.32 ms, with statistically significant (p < 0.001). More patients in the rosuvastatin group had an increased QTc interval (62.7% vs. 46.6%, p < 0.001). Patients with newly emerged QT prolongation in rosuvastatin group were significantly more than those in atorvastatin group (9.2% vs. 4.2%, p = 0.030). However, there was no significant difference in the incidence of severe QT prolongation between the two groups (2.6% vs. 1.7%, p = 0.537). During follow-up, none of the patients in either group developed TdP and severe statin adverse reactions.

As shown in Fig. 2, the correlation between statins and end-point events was analyzed by log-binomial regression. Compared with atorvastatin, rosuvastatin increased the risk of a longer QTc interval by 35% (p = 0.001), and the risk of newly emerged QT prolongation by 42% (p = 0.008), but there was no correlation between rosuvastatin and severe QT prolongation (p = 0.426).

Univariate logistic regression analysis was used to analyze the correlation between patient characteristics and QT prolongation of baseline ECG, and the results are shown in Fig. 3. Table 3 lists the factors related to QT prolongation and the results of multivariate analysis. Age was associated with QT prolongation independently, the risk of QT prolongation increased by 45% (95% CI 1.11–1.91, p = 0.007) for each additional 10 years of age. Atrial fibrillation (OR 2.89, 95% CI 1.24–6.74, p < 0.001) and heart failure (OR 3.85, 95% CI 1.83–8.12, p < 0.001) were independent risk factors closely related to QT prolongation. Serum calcium was negatively correlated with QT prolongation, an increase in serum calcium of 0.1 mmol/L was associated with a 28% reduction in the risk of QT prolongation (95% CI 0.53–0.99, p = 0.042).

The variables serum calcium and magnesium were statistically transformed to make their values 10 times those of the original, and the values of age and creatinine were statistically transformed to 0.1 times of the original. LVEF and LVD are causally related to chronic heart failure, so they were not included in the multivariate regression model.

In order to eliminate the influence of confounding factors on QT prolongation induced by rosuvastatin, logistic regression analysis was used again to anlyze the correlation between rosuvastatin and newly emerged QT prolongation. Univariate analysis showed that they were closely related (OR 2.31, 95% CI 1.06–5.03, p = 0.034). After adjusting for age, heart failure, atrial fibrillation and drug use, it showed that rosuvastatin was an independent risk factor for newly emerged QT prolongation (OR 2.57, 95% CI 1.12–5.90, p = 0.025).

Anticoagulants were associated with newly emerged QT prolongation (OR 2.91, 95% CI 1.03–8.17, p = 0.043), but the association disappeared after adjusting for atrial fibrillation. Beta-blockers (OR 1.82, 95% CI 0.75–4.42, p = 0.184) and any other drugs were not associated with newly emerged QT prolongation (p > 0.05).

Discussion

In this study, we observed that compared with the atorvastatin group, more patients in the rosuvastatin group had an increased QTc interval after therapy, and more patients with normal QTc interval at baseline developped QT prolongation. Rosuvastatin can increase the risk of QT prolongation.

Statins are the first-line treatment for lowering LDL-C, consistently recommended by national guidelines, and are widely used for primary and secondary prevention of atherosclerotic cardiovascular disease17,18,19. It is estimated that approximately 145.8 million people (2.6%) in the world are taking statins23. Previous studies have shown that atorvastatin and simvastatin can shorten the QTc interval and QTc dispersion24,25, and the mechanism may be related to the improvement of blood cholesterol level26,27,28. However, this effect was not observed in the study of rosuvastatin. In contrast, rosuvastatin can potentially disrupt the transport of immature hERG potassium channels to the membrane and increase the degradation of mature hERG potassium channels, thereby blocking the delayed rectifier potassium current (IKr) at the late phase of rapid repolarization of the myocardial action potential, resulting in increased QTc interval15– 16. Koo et al. analyzed 1,040,752 ECG results from a database and found that patients with QT prolongation had a higher rate of rosuvastatin use than those with a normal QTc interval. They speculated that rosuvastatin may be associated with QT prolongation, which provided new evidence for the effect of rosuvastatin on QTc interval9.

However, that case-control study could not infer whether exposure factor “rosuvastatin” was a cause or a result of QT prolongation, and the small sample cohort study did not find a statistically significant correlation between rosuvastatin and QT prolongation. To this end, we conducted this randomized controlled trial that was strictly controlled for potential interfering factors. Our study demonstrated that rosuvastatin can induce a longer QTc interval and increase the risk of QT prolongation. Compared with atorvastatin, rosuvastatin increased the risk of newly emerged QT prolongation by 42%, and we found that rosuvastatin alone rarely directly leads to severe QT prolongation. This explains why Koo et al. found in their investigation of the National Health Insurance Service (NHIS) database in South Korea that the long-term use of rosuvastatin does not increase mortality.

Electrolyte abnormalities are an important cause of acquired LQTS and TdP. Previous studies have shown that hypokalemia and hypocalcemia can cause QT prolongation. Hypomagnesia does not produce specific ECG changes, but the injection of magnesium sulfate inhibits the onset of TdP in patients with QT prolongation29. This study excluded patients with severe electrolyte disorders and observed that serum potassium and magnesium levels were not independently associated with QT prolongation wtinin a relatively stable concentration range, whereas serum calcium was still associated with QT prolongation. Age is strongly associated with QT prolongation. Data analyses based on several large studies have shown that QTc interval increases with age. The Swedish pharmacovigilance database survey found that the most common risk factor for drug-induced TdP was age > 65 years, occurring in 72% of cases30. In this study, the risk of QT prolongation increased by 45% for each additional 10 years of patient age group. In addition, atrial fibrillation and heart failure were independent risk factors for QT prolongation, consistent with the results observed in others31,32. Interestingly, QT prolongation indicates a higher risk of future occurrence of atrial fibrillation and heart failure33,34,35.

This study have some limitations. First, we followed the ECG at a specific time after the patient’s medication, but continuous ECG monitoring was not performed. Secondly, the follow-up period of this study was short, so it was not possible to determine whether the QTc interval would further increase with prolonged medication duration. Finally, to prevent QT-prolonging drugs and acute cardiac events from interfering with the observation of the effect of rosuvastatin on QTc interval, we excluded patients with acute heart failure, acute myocardial infarction, severe non-ventricular arrhythmias, and those on QT-prolonging drugs. Therefore, the safety of rosuvastatin in these patients could not be confirmed.

Conclusion

Rosuvastatin can induce a longer QTc interval and increase the risk of QT prolongation. But rosuvastatin alone rarely directly leads to severe QT prolongation in patients. It is unnecessary to overly worry about the arrhythmogenic effect of rosuvastatin, but for patients who take rosuvastatin and other QT-prolonging drugs at the same time, the detection of QTc interval should be strengthened.

Data availability

The datasets used and analyzed during the current study are available from the corresponding author on reasonable request.

References

Moss, A. J. et al. The long QT syndrome. Prospective longitudinal study of 328 families. Circulation 84, 1136–1144 (1991).

Zareba, W. et al. International Long-QT syndrome registry research group. N Engl. J. Med. 339, 960–965 (1998).

Straus, S. M. et al. Non-cardiac QTc-prolonging drugs and the risk of sudden cardiac death. Eur. Heart J. 26, 2007–2012 (2005).

De, Bruin, M. L. et al. In-hospital cardiac arrest is associated with use of non-antiarrhythmic QTc-prolonging drugs. Br. J. Clin. Pharmacol. 63, 216–223 (2007).

Food and Drug Administration & HHS. International conference on harmonisation; guidance on S7B nonclinical evaluation of the potential for delayed ventricular repolarization (QT interval Prolongation) by human pharmaceuticals; availability. Notice. Fed. Regist. 70, 61133–61134 (2005).

Food and Drug Administration, HHS. International conference on harmonisation; guidance on E14 clinical evaluation of qt/qtc interval prolongation and proarrhythmic potential for Non-Antiarrhythmic drugs; availability. Notice. Fed. Regist. 70, 61134–61135 (2005).

Van, Noord, C., Eijgelsheim, M. & Stricker, B. H. Drug- and non-drug-associated QT interval prolongation. Br. J. Clin. Pharmacol. 70, 16–23 (2010).

Woosley, R. L., Black, K., Heise, C. W. & Romero, K. CredibleMeds.org: what does it offer? Trends Cardiovasc. Med. 28, 94–99 (2018).

Koo, Y. et al. Evaluation of rosuvastatin-induced QT prolongation risk using real-world data, in vitro cardiomyocyte studies, and mortality assessment. Sci. Rep. 13, 8108 (2023).

Cortese, F. et al. Rosuvastatin: beyond the cholesterol-lowering effect. Pharmacol. Res. 107, 1–18 (2016).

Rosuvastatin - third-generation statin, https://www.statinanswers.com/rosuvastatin.htm

Alsheikh-Ali, A. A., Ambrose, M. S., Kuvin, J. T. & Karas, R. H. The safety of Rosuvastatin as used in common clinical practice: a postmarketing analysis. Circulation 111, 3051–3057 (2005).

Davidson, M. H. Rosuvastatin safety: lessons from the FDA review and post-approval surveillance. Expert Opin. Drug Saf. 3, 547–557 (2004).

García-Rodríguez, L. A., Massó-González, E. L., Wallander, M. A. & Johansson, S. The safety of Rosuvastatin in comparison with other Statins in over 100,000 Statin users in UK primary care. Pharmacoepidemiol. Drug Saf. 17, 943–952 (2008).

Plante, I., Vigneault, P., Drolet, B. & Turgeon, J. Rosuvastatin blocks hERG current and prolongs cardiac repolarization. J. Pharm. Sci. 101, 868–878 (2012).

Feng, P. F. et al. Intracellular mechanism of Rosuvastatin-Induced decrease in mature hERG protein expression on membrane. Mol. Pharm. 16, 1477–1488 (2019).

Virani, S. S. et al. 2023 AHA/ACC/ACCP/ASPC/NLA/PCNA guideline for the management of patients with chronic coronary disease: A report of the American heart association/american college of cardiology joint committee on clinical practice guidelines. Circulation 148, e9–e119 (2023).

Byrne, R. A. et al. 2023 ESC guidelines for the management of acute coronary syndromes. Eur. Heart J. 44, 3720–3826 (2023).

Visseren, F. L. J. et al. 2021 ESC guidelines on cardiovascular disease prevention in clinical practice. Eur. Heart J. 42, 3227–3337 (2021).

Poole, S. A., Pecoraro, A., Subramaniam, G., Woody, G. & Vetter, V. L. Presence or absence of QTc prolongation in Buprenorphine-Naloxone among youth with opioid dependence. J. Addict. Med. 10, 26–33 (2016).

Wang, C. L. et al. Incidences, risk factors, and clinical correlates of severe QT prolongation after the use of quetiapine or haloperidol. Heart Rhythm. 21, 321–328 (2024).

Piantadosi, S. Chapter 7. Clinical Trials: A methodologic perspective. (Wiley, 1997).

Blais, J. E. et al. Trends in lipid-modifying agent use in 83 countries. Atherosclerosis 328, 44–51 (2021).

Munhoz, D. B. et al. Statin use in the early phase of ST-Segment elevation myocardial infarction is associated with decreased QTc dispersion. J. Cardiovasc. Pharmacol. Ther. 25, 226–231 (2020).

Xie, R. Q. et al. Statin therapy shortens qtc, qtcd, and improves cardiac function in patients with chronic heart failure. Int. J. Cardiol. 140, 255–257 (2010).

Chun, Y. S., Oh, H. G., Park, M. K., Cho, H. & Chung, S. Cholesterol regulates HERG K + channel activation by increasing phospholipase C β1 expression. Channels (Austin). 7, 275–287 (2013).

Den, Ruijter, H. M. et al. Reconstituted high-density lipoprotein shortens cardiac repolarization. J. Am. Coll. Cardiol. 58, 40–44 (2011).

Del, Giorno, R. et al. Association between HDL cholesterol and QTc interval: A population-based epidemiological study. J. Clin. Med. 8, 1527 (2019).

El-Sherif, N. & Turitto, G. Electrolyte disorders and arrhythmogenesis. Cardiol. J. 18, 233–245 (2011).

Rabkin, S. W. Impact of age and sex on QT prolongation in patients receiving psychotropics. Can. J. Psychiatry. 60, 206–214 (2015).

Pai, G. R. & Rawles, J. M. The QT interval in atrial fibrillation. Br. Heart J. 61, 510–513 (1989).

Pai, R. G. & Padmanabhan, S. Biological correlates of QT interval and QT dispersion in 2,265 patients with left ventricular ejection fraction < or = 40%. J. Electrocardiol. 35, 223–226 (2002).

Nielsen, J. B. et al. J-shaped association between QTc interval duration and the risk of atrial fibrillation: results from the Copenhagen ECG study. J. Am. Coll. Cardiol. 61, 2557–2564 (2013).

Mandyam, M. C. et al. The QT interval and risk of incident atrial fibrillation. Heart Rhythm. 10, 1562–1568 (2013).

Zhang, S. et al. Six-Year change in QT interval duration and risk of incident heart failure - A secondary analysis of the atherosclerosis risk in communities study. Circ. J. 85, 640–646 (2021).

Funding

This study was supported by the Key Specialized Construction Project in Cardiology Department of Zhejiang Province (2023-SZZ) and the Medical and Health Science and Technology Project of Zhejiang Province (2024KY1483).

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

LJZ and QJJ designed this study. YWW and CLW led to recruitment and data acquisition. LJZ and JL completed the follow-up. LC and WJS verified ECG data. LJZ and HWG performed statistical analyses and drafted the manuscript. WYH and QJJ critically revised the manuscript. All authors revised and approved the final version of the manuscript.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher’s note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if you modified the licensed material. You do not have permission under this licence to share adapted material derived from this article or parts of it. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Zhu, L., Shen, W., Hu, W. et al. A randomized controlled trial of the short-term effect of rosuvastatin on the corrected QT interval. Sci Rep 15, 32076 (2025). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-17995-y

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-17995-y