Abstract

Rumen microorganisms are primarily essential for feed decomposition and nutrition of the host animal, playing a key role in the health and well-being of cattle as well as the efficiency of milk or meat production. However, they also generate pollutant emissions such as methane. Analysing this microbiota under different farming conditions is therefore essential for optimizing production while minimizing its environmental impact. In this study, with metataxonomic sequencing and qPCR, we analysed the composition of the cow rumen microbiota sampled through the cannula and via esophageal tubing before morning feeding under two contrasting diets, low- and high-starch contents. Buccal swabs were also collected at the same sampling times to assess their potential as a proxy for the rumen microbiota. The two rumen sampling methods resulted in similar taxonomic compositions of bacteria, Archaea, fungi and protozoa and showed similar changes after the diet shift, indicating that the use of esophageal tubing is a reliable method for capturing the microbiota structure and its potential shifts following dietary changes. In contrast, the buccal swabs did not accurately reflect the rumen microbiota under the low- and high-starch diets, even after specific stringent filtering of the buccal sequences. Furthermore, we identified microbial markers of acidogenic challenge, with Dialister spp. also detected in buccal swab samples as potential indicators.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Ruminants are very efficient herbivores capable of extracting nutrients and energy from a wide range of feedstuffs, including lignified fibres, owing to the multitude of microbes living in their rumen. These microorganisms degrade and ferment plant material into short-chain fatty acids, which serve as the primary energy source for the animal. In addition, the rumen microbes are an important source of proteins which are degraded in the small intestine of the animal1. The development of rapid DNA sequencing methods has allowed easy description of the taxonomic composition of the rumen microbiota and its evolution in response to various factors, such as the animal’s diet, age, environment and breed2. Key animal phenotypes, such as feed efficiency and methane emission, have been linked to the composition of the rumen microbiota3,4,5. Therefore, it is crucial to continue studying the dynamics and behavior of the ruminal microbiota in relation to various factors to manipulate its composition and activity toward phenotypes that benefit both the animal and the environment. More broadly, accurate characterization of the rumen microbiome is essential for improving animal health, addressing major nutritional challenges in the dairy and beef industries, and promoting more sustainable livestock production5.

One of the main challenges in studying the rumen microbiota is obtaining access to the rumen contents and collecting representative samples of the entire microbial community. The gold standard method for sampling rumen microbial contents is through a rumen cannula, which allows easy collection of rumen contents, representative sampling, and, if necessary, specific sampling of the pregastric compartments6,7. However, this method requires invasive surgery and technical expertise, so it is generally limited to a small number of animals and is typically used in well-controlled experimental farms, which are usually located in research centers. In France, nongovernmental organizations have called for the abandonment of this method because of concerns about animal welfare. Esophageal tubing is another method that provides direct access to rumen fluid and is currently used worldwide. However, this method is also invasive and can cause discomfort in animals. Moreover, it has been reported that this method can lead to contamination of rumen samples with saliva, causing bias in rumen pH determination8,9 and preventing consistent recovery of solid particles10,11. Several studies have compared the composition of the rumen microbiome obtained from rumen cannulas and esophageal tubing. Some studies have shown differences in microbial composition between these two techniques9,10,12,13whereas others have reported similar compositions8,10. Additionally, neither method can be applied to large herds of hundreds of cows. Considering the limitations of these rumen sampling methods, buccal swabbing has been proposed as a proxy for rumen microbiota sampling, as it allows for the collection of population-scale rumen microbial samples in a relatively easy manner. During rumination, ruminal content is regurgitated into the oral cavity, and it has been hypothesized that buccal swab samples might provide an accurate representation of the rumen microbiota14,15. However, studies published to date have shown that buccal swab samples display different taxonomic profiles than rumen samples, with most taxa being specific to the mouth, although rumen genera/species are also detected15,16.

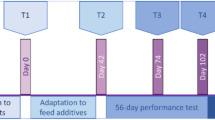

The aim of the present study was to compare the taxonomic composition of the rumen microbiota in samples collected simultaneously via esophageal tubing and cannula from six rumen-fistulated cows subjected to alternating diets: a standard corn silage-based diet (Periods 1 and 3) and a starch-enriched diet (Period 2). The primary factor affecting the composition and diversity of the rumen microbiota is diet, particularly the forage-to-concentrate ratio2,17. For this reason, the comparison of the two sampling methods was conducted under two distinct dietary compositions, with the shift from a standard diet to a starch-enriched diet constituting an acidogenic challenge that could induce subacute rumen acidosis (SARA). Rumen sampling was carried out weekly during each of the three four-week periods, enabling a longitudinal analysis of the evolution of the microbiota over the 12 weeks of the experiment. The taxonomic compositions of bacteria, Archaea and fungi were assessed through metataxonomic sequencing, ciliate protozoa were counted, and all four microbial populations were quantified via qPCR. At the same time, buccal swabs were collected to investigate their potential as a proxy for rumen microbiota sampling.

Results

Composition and comparison of the rumen and buccal microbiomes

The rumen microbiome and buccal swabs were sampled from six cows each week during three months. Rumen content was sampled using two methods, via esophageal tubing and through the cannula (12 samples X 3 sampling methods for each cow). The samples were taken on Thurdays of each week. The cows were fed a standard corn silage-based diet during the first period (Period 1, four weeks), a starch-enriched diet during Period 2 (four weeks), and returned to the standard diet in Period 3 (four weeks).

Bacteria

The taxonomic composition of the rumen microbiome sampled every week of the three experimental periods of the trial by esophageal tubing (ET) or rumen cannula (RC) and of the buccal microbiota sampled by swabbing (BS) are shown in Supplementary information 1, Figure S1, at the prokaryotic phylum and family levels. The taxonomic composition clearly revealed that the bacterial profiles of the buccal swab samples were different from those of the rumen samples collected via the two methods. Beta diversity analysis with anova (p < 0.05) and PCoA (Bray‒Curtis distance) (Supplementary information 1, Fig. S1C) confirmed this observation. We then used the indicspecies package of R18,19 to identify taxa that were specific to the buccal swab group (Supplementary information 2, Table S1). The corresponding ASVs, considered “mouth-specific taxa”, were then removed (stringent filtering) from the buccal swab abundance tables, and a new analysis was carried out. The taxonomic composition of the buccal swab samples after suppression of the mouth-specific taxa (stringent filtration of buccal swab samples) is shown in Fig. 1 with the RC and ET samples at the phylum (1A) and family (1B) levels. Alpha diversity (Fig. 1C) analysis revealed that the microbiota diversity of the ET and RC samples was not significantly different, whereas it was significantly different from that of the filtered buccal swab samples (p < 0.001). Beta diversity analysis (PERMANOVA with Bray-Curtis dissimilarity) revealed similar results, with RC and ET not differing, but both were dissimilar to the BS samples (p < 0.001). PLS-DA (partial least square discriminant analysis) also revealed that the cannula and esophageal tubing samples were grouped together (Fig. 1D). We tested several thresholds to identify and delete the “mouth-specific taxa” from BS sequences using the indicspecies package (p values ranging from 0.001 to 0.05), but the PERMANOVA (Bray-Curtis dissimilarity) indicated that BS samples were still different from the RC and ET samples.

Prokaryotic composition of the buccal swab (BS), rumen cannula (RC) and esophageal tubing (ET) samples after the suppression of specific buccal ASVs (stringent filtering). (A) Prokaryotic phyla of the BS, RC and ET samples of each cow; (B) Prokaryotic families of the BS, RC and ET samples; (C) alpha diversity analysis; (D) PLS-DA analysis of the different samples (BS, blue circles; RC, orange triangles; ET, grey cross).

Archaea and fungi

The indicspecies package did not identify BS-specific Archaea taxa, thus no filtering was applied. Archaea beta diversity was significantly different between the BS samples and the two types of rumen samples (p < 0.001) and between the RC and ET samples (p < 0.01). BS-specific fungal ITSs were identified and thus filtered (stringent filtering) for further analysis (Supplementary information 3, Table S2). Very few sequences from the Neocallimastigomycota phylum were found in the BS samples. The fungal beta diversity in the BS samples was different from that in the two other sampling methods (p < 0.001), whereas the RC and ET fungal compositions did not differ from each other.

Quantification of the rumen and buccal populations by qPCR

Bacteria, Archaea, protozoa and fungi were quantified via qPCR in rumen samples obtained via the two methods and in buccal swab samples. The qPCR results of BS, RC and ET, expressed per µg of DNA, are presented in Fig. 2. The quantification of bacteria, protozoa and fungi did not differ among the three sampling methods, except for fungi at P2W3, but Archaea were quantified at lower levels in most of the BS samples (p < 0.0001). A time effect was observed for all populations regardless of the sampling mode (p < 0.0001 for protozoa and fungi and p < 0.001 for Archaea), except for bacteria (Fig. 2). The greatest decrease in fungal, archaeal and protozoal abundances was observed in the third week of Period 2 (P2W3).

The protozoa were also quantified by counting in the ET and RC samples collected at P1W3, P2W3 and P3W3 for the 6 cows. The total protozoa counts are shown in Fig. 3. A time effect was clearly observed (p < 0.01) on the total protozoa enumeration performed the third week of each period. We also counted specific populations on the basis of their morphology, i.e., Entodiniomorphs < 100 μm and > 100 μm and Holotrichs Dasytricha and Isotricha (Supplementary Information 1, Figure S2). A time effect was also found for Entodiniomorphs. However, protozoa abundance was not significantly different in the ET and RC samples, either for total protozoa (Fig. 3) or for the specific protozoal populations (Supplementary information 1, Figure S2).

Detailed comparison of the rumen microbiota recovered from cannula and esophageal tubing samples

Rumen microbiota taxonomic composition and alpha and beta diversity were then analysed using only the sequences obtained from the ET and RC samples, excluding BS data. This allowed, on the one hand, a better comparison of the impact of these two sampling methods on the community sequencing results and, on the other hand, an in-depth analysis of the impact of the acidogenic challenge on the rumen microbiota.

Alpha and beta diversity analysis of RT and RC samples. Alpha diversity analysis of bacteria revealed that the number of observed ASVs and the Chao1 and inverse Simpson indices were significantly different between the RC and ET samples (p < 0.05) (Supplementary information 1, Table S3). The Shannon index was not different between the two sampling methods. With respect to Archaea, only the Shannon index was significantly different between the RC and ET samples, and for fungi, none of the indices differed according to the sampling method (Supplementary information 1, Table S3). Notably, for bacteria, Archaea and fungi, most of the alpha diversity indices (ANOVA) were different between the animals, and all the indices were significantly different between the sampling times (Supplementary information 1, Table S3).

Beta diversity analysis (PERMANOVA Bray-Curtis dissimilarity) revealed that the bacterial and fungal compositions did not differ between the RC and ET samples, whereas the archaeal population structure was significantly dissimilar between those samples (p = 0.01) (Supplementary information 1, Table S4). Figure 4 shows that the ET and RC bacterial ASVs clustered well together according to the sampling method (Fig. 4A), and time of sampling. Beta diversity analyses revealed significant differences between cows and time points for all targeted microbial populations (Supplementary information 1, Table S4).

Principal coordinate analysis (PCoA) based on the Bray‒Curtis distance method at the bacterial ASV level. (A) PCoA showing the samples according to the sampling method (red, RC, cannula; blue, ET, esophageal tubing); (B) PCoA showing the samples according to the time of sampling: period (P) and week (W). Samples are named by the sampling method, animal (C1 to C6) and period-week.

Community composition in the RC and ET rumen samples and impact of the diet shift. The evolution of the composition of the rumen bacteria during the three periods was compared in the RC and ET samples at the phylum and family (Fig. 1) and species levels (Fig. 5). As expected, the main observed phyla in both RC and ET were Bacillota (~ 50% of sequences) and Bacteroidota (~ 30% of sequences), followed by Actinobacteria and Proteobacteria (Fig. 1). The data clearly revealed a shift in bacterial composition in P2 compared with P1. In particular, starch diet resulted in decrease of Ruminococcaceae and Rikenellaceae while Prevotellaceae, Succinivibrionaceae, Megasphaeraceae and Selenomonaceae families were increased (Fig. 1). A shift in species was detected within the Prevotella genus (Fig. 5). Principal coordinate analysis (PCoA) of the bacterial ASVs also revealed strong evolution with time (Fig. 4B). The selected populations were analysed more precisely to compare the dynamics of their relative proportions during the three periods and according to the two sampling methods (Fig. 6). For all the selected genera or groups, except Streptococcus, the effect of time was significant (Supplementary information 1, Table S5), with a clear increase or decrease in the genera at P2W2. Indeed, the relative abundances of Lactobacillaceae, Prevotella (including Alloprevotella, Prevotella and Paraprevotella) and Megasphaera significantly increased in P2, whereas in P3, their relative proportions were similar to those in P1 (Fig. 6). In contrast, the relative proportions of the Butyrivibrio, Ruminococcus and Fibrobacter genera decreased significantly in P2, but these populations increased in P3 to reach the level found in P1. Finally, no significant effect of the sampling method was detected, except for the Prevotella group (Supplementary information 1, Table S5), with a slightly greater proportion found in the RC samples.

Relative abundance (% of total sequences belonging to the same kingdom) of selected bacterial genera/families and archaeal families retrieved from the two sampling methods during each week (W) of the three experimental periods (P). Green bars: sampling through the cannula; blue bars: sampling through esophageal tubing.

With respect to Archaea, the main family detected was Methanobacteriaceae (> 90% of sequences, mainly the Methanobrevibacter genus), followed by Methanomethylophilaceae. We also compared the relative proportions of these taxa according to time and sampling method (Fig. 6). There was a significant effect of time, but no effect of sampling method was observed for either Archaea family (Supplementary information 1, Table S5). In week 2, 3 and 4 of Period 2, an increase in the proportions of the genera Methanosphaera and Methanomethylophilaceae was observed, concomitant with a decrease in the proportion of the Methanobrevibacter genus (Supplementary information 1, Figure S3).

The main fungal family observed during the 4 weeks of Period 1 and the last 3 weeks of Period 3 was Neocallimastigaceae, whereas from P2W1 to P3W1, sequences belonging to this family nearly disappeared and were replaced by sequences affiliated with the Saccharomycetales family (Supplementary information 1, Figure S4).

As shown by qPCR and counting, and already indicated, there was a strong decrease in the protozoa concentration in P2W3 (Fig. 3). Small Entodiniomorphs and Dasytricha were hardly detected at P2W3, and the numbers of small and large Entodiniomorphs decreased significantly compared with P1W3 (Supplementary information 1, Figure S2).

Marker taxa of the acidogenic challenge in RC, ET and BS samples

Identification of markers in RC and ET samples. We then used differential analyses to identify taxa specific to each period/week to discover markers of the acidogenic challenge and compare the RC and ET sampling methods under perturbed conditions. PLS-DA revealed an evolution of the microbiota according to week, and very similar patterns were observed when comparing the RC and ET data (Fig. 7). Analysis of the components from the two sampling methods yielded rather similar results (Supplementary information 1, Figure S5), with Dialister species clearly being a marker of Period 2 (particularly P2W3) and species from the Oscillospiraceae family being a marker of Period 1. The relative abundances of the species identified as markers of weeks/period with the PLS-DA analysis are presented in Supplementary information 1, Figure S6, for the two sampling modes.

Identification of markers in BS samples. Finally, we analysed the relative abundance of selected taxa in the BS samples and their evolution with time. These taxa were chosen among those that varied the most with acidogenic challenge in the ET and RC rumen samples. High variability in their relative abundance was detected among the BS samples (Supplementary Information 1, Figure S7), and their variation with time (period) was not statistically significant, except for Dialister (p < 0.01).

Discussion

In this work, we compared the taxonomic composition of the rumen microbiota sampled through esophageal tubing and through cannula, and we evaluated the use of buccal swabs as a proxy for the rumen microbiota. The originality of this study lies in the fact that these analyses were conducted over a three-month period on cows subjected to a dietary shift intended to generate subacute ruminal acidosis, which was successfully triggered, as previously described20. The recovery period following starch challenge was also monitored to assess the resilience of the microbial community. Another novel aspect of this work is that all microbial populations in the rumen, including bacteria, Archaea, fungi and protozoa, were specifically analysed throughout the experiment. Most similar studies have focused only on rumen bacteria in animals on a single diet and for just one or a few days8,9,10,12.

Relevance of the buccal swabbing method

Because esophageal tubing and rumen cannulation are invasive methods that can affect animal welfare and cannot be applied to large-scale animal experiments, several studies have evaluated the use of BS samples as a proxy for rumen microbiota profiling in cows and sheep14,15,16,21,22. These studies revealed that the buccal swab microbiota does not fully reflect the rumen microbiota, although rumen taxa can be identified in buccal swab samples. To obtain valuable information on the composition of the rumen microbiome, it was necessary to remove potential oral or feed taxa from libraries of samples collected via buccal swabs15,16,21. Sampling time has been shown to be a potential confounding factor in profiling the rumen microbial community through buccal swabbing. Sampling before the morning feeding, as was done in the present study, produced more concordant results between the rumen and buccal microbiota compositions16. Here, we used the indicspecies package in R18 to identify specific ASVs of the oral cavity and filtered with high stringency these sequences from our analyses. The beta diversity of the BS samples was distinct from that of the RC and ET samples, although the composition profiles of the major taxa appeared similar. Although previous studies concluded that buccal swabs provide accurate information on the bacterial composition of the rumen microbiome after filtering oral sequences14,15,16,21,22differences emerged upon deeper data analysis. Amplicon sequencing near the full-length 16S rRNA gene via specific PCR conditions and MinION technology revealed good correlation between predominant bacterial taxa in buccal swabs and rumen samples21. However, as in previous works, the buccal swabbing method in our study produced low DNA yields, particularly for fungi and protozoa, making PCR amplification less reliable16,21,22. This is a key limitation for the detection and quantification of rumen eukaryotic taxa in BS samples via qPCR. Finally, although we obtained taxonomic bacterial profiles rather similar to those of the rumen samples after the buccal taxa were filtered out with high stringency, BS samples were unable to accurately capture the microbiota shifts during the acidogenic challenge. Only Dialister sequences increased significantly in P2 in the BS samples, as observed in the rumen ET and RC samples. Overall, our results suggest that while buccal swab samples are not fully representative of rumen samples, they may still be useful for detecting markers of microbiota dysbiosis during nutritional challenges in large-scale studies. Additionally, the buccal swabbing technique could be improved for more reliable results, for example, by increasing the swabbing duration or optimizing the sampling time to better coincide with rumination.

Esophageal tubing and cannula sampling lead to similar taxonomic compositions of the rumen microbiota

In most previous studies, no significant differences in microbiota composition were reported between cannula and esophageal tube samples, although the methods used varied. In the work of da Cunha et al.8 dairy cows were sampled 5–6 h after morning feeding, and samples were taken from combined cranial, caudal, dorsal, and ventral regions of the rumen through a cannula. Two other studies also reported no differences in richness or community composition between RC and ET rumen samples from cows and steers10,23. In these two studies, the rumen contents were collected postfeeding. In the present study, we collected samples before the morning feeding, and for the cannula samples, we used both the reticulum and the ventral part of the rumen. Despite these differences in sampling time and localization compared with the studies mentioned above, our results were consistent. Ramos-Morales et al. also reported similarities in the rumen microbiota of sheep and goats via RC and ET, as analysed by DGGE and qPCR of selected populations24. However, other studies have reported differences between ET and RC samples. For example, de Assis Lage et al. and Pathak et al. reported that bacterial composition was influenced by the sampling method9,12. In de Assis Lage et al., samples were collected between 0 and 12 h after morning feeding, revealing an interaction between the sampling method and sampling time. Pathak et al. sampled samples 4 h after feeding and reported similar alpha diversity between RC and ET samples but different Firmicutes/Bacteroidetes ratios9. Hagey et al.13 reported that, compared with RC samples, ET samples presented lower richness and lower abundance of certain bacterial taxa, such as Lachnospiraceae and Fibrobacter. Notably, in our work, the relative abundance of these taxa did not differ between the ET and RC samples. Hagey et al. also concluded that ET samples were rather representative of the rumen liquid phase and suggested that including particulate matter is important for an accurate representation of rumen bacteria13. In their study, Paz et al. enriched ET samples with particulate matter by including particles attached to the strainer10. Notably, in some studies, differences in the ruminal parameters and microbiota may be attributed more to the sampling location within the rumen than to the sampling method (ET or RC). Additionally, the DNA extraction methodology may contribute to differences between studies, particularly in microbial diversity and bacterial relative abundance25. A comparison of data from the literature suggests that the results are more consistent for samples taken before the morning feeding. Finally, although some metrics of alpha diversity were different between RC and ET, our results indicate that ET samples can accurately reflect the composition of the rumen microbiota, as well as its changes over time and with dietary shifts. The bacterial and fungal compositions (beta diversity) and their evolution over time were similarly revealed by both ET and RC. For Archaea, although beta diversity differed between the two sampling methods, the dominant taxa and their changes over time were comparable.

Impact of acidogenic challenge on the rumen microbiota

The nutritional challenge, which was based on a high-energy diet used in this study, successfully induced subacute acidosis in Period 2, as previously demonstrated20. Specifically, SCFA levels were significantly reduced, with an acetate/propionate ratio less than 3, which is associated with the onset of ruminal acidosis26. Additionally, the mean rumen pH was notably lower 5 h postfeeding in Period 2 (−0.64 pH units) than in Period 1, although it remained stable at mean values close to 7.0 before the morning feeding, regardless of the period20. This finding is consistent with other studies indicating that the pH value per se does not signal rumen acidosis, and that relative pH indicators must be calculated to detect SARA27.

In the present work, the acidogenic challenge resulted in shifts in several bacterial species and a sharp decline in fungal and protozoal populations, regardless of the sampling method, despite the near-neutral pH at the time of sampling. A reduction in fungi following subacute rumen acidosis (SARA) has been reported previously, although Entodinium protozoa often remain at high levels in the rumen of SARA animals28,29,30. A decrease in rumen protozoa in P2 has also been observed in similar experimental designs27. In terms of bacterial changes, the increased starch in the diet led to the proliferation of starch degraders and lactate utilizers, such as members of the Prevotellaceae, Selenomonaceae and Megasphaeraceae families, a pattern observed in many studies17,29,30,31,32,33,34,35,36. As in most of these studies, a decrease in Ruminococcaceae was also noted in our data, along with a significant reduction in fibre-degrading genera such as Ruminococcus, Fibrobacter and Butyrivibrio. Within the Prevotellaceae, we observed a shift in the Prevotella species between P1 and P2. The genus Prevotella is phenotypically, ecologically and functionally diverse, with broad activities, including amylolytic, proteolytic and hemicellulolytic capabilities37. Recent genomic analyses have separated Prevotella into seven clades, with rumen isolates distributed across several of these clades38. For example, the well-known rumen Prevotella species P. albensis, P. bryantii and P. ruminicola37 were reclassified into Segatella albensis, Segatella bryantii and Xylanibacter ruminicola, respectively38. It is possible that hemicellulolytic species from these clades were predominant in P1, whereas amylolytic species dominated in P2.

Differential analyses allowed us to identify marker taxa of the acidogenic challenge, which were consistent in both the ET and RC samples. These include the genus Dialister, which emerged as a marker of the acidogenic period in both rumen sampling methods and in buccal swab samples, as previously noted. The Oscillospiraceae NK4A214 group, Christensenellaceae R-7 and Anaerorhabdus furcosa were also identified as markers and significantly decreased in P2. In the human gut, members of the genus Dialister are considered proinflammatory because of their ability to induce the release of inflammatory mediators by immune cells. Indeed, relative enrichment of Dialister has been observed in irritable bowel disease (IBD) patients, along with simultaneous depletion of Christensenellaceae39. In the rumen of lactating dairy cows, Dialister was more abundant in cows with high-grain-induced SARA, whereas Christensenellaceae R-7 abundance decreased, similar to our findings40. In an in vitro simulation of SARA, a decrease in pH also increased the abundance of Dialister in the fermenter41. In another recent study, a greater abundance of Dialister and lower abundances of Oscillospiraceae NK4A214, Christensenellaceae R-7 and Rikenellaceae RC9 were associated with a low nonglucogenic (acetate and butyrate)-to-glucogenic (propionate) SCFA ratio (NGR)42. This ratio is an indicator of rumen propionate production and is correlated with reduced enteric methane emissions and SARA, where the acetate/propionate ratio decreases. Additionally, Dialister has been linked to higher feed efficiency and average daily gain in steers43and it was increased in cows with high yields of rumen microbial protein, suggesting a role in ruminal NH3 metabolism44. Dialister is known to produce lactate, and some species, such as D. succinatiphilus, can use succinate to produce propionate42. Together with our results, these findings indicate that Dialister might be a reliable marker of SARA onset, indicating that further research is needed to better characterize its properties.

In addition to the significant shifts in bacterial composition, the acidogenic challenge led to changes in methanogenic genera and to the disappearance of Neocallimastigomycota. This shift in dominant methanogenic genera may explain the maintenance of methane emissions with high-grain diets, as previously reported45. However, in P3, the proportions of Archaea and fungal taxa returned to levels similar to those measured in P1.

A remarkable property of the rumen microbiota, highlighted in this study, is its robustness and resilience to dietary perturbation, as observed in earlier work46,47. The rumen microbiota exhibited rapid adaptation to the dietary shift (P1 to P2) and, importantly, strong resilience, as the initial relative abundance of the various taxa analysed in P3 recovered. This may be attributed to the progressive increase in dietary starch used in the present study, which has been shown to prevent more acute forms of rumen acidosis27 and support microbiota adaptation and resilience48.

Conclusion

Although some metrics of alpha diversity were different between RC and ET, the overall composition showed by beta diversity analysis, presents a similar evolution between ruminal samples (RC and ET) over time as well as after a diet shift. Our data suggest that, in samples taken before morning feeding, ET is a reliable sampling method for capturing microbiota structure and potential shifts following dietary changes. However, the relevance of this practice needs to be evaluated for repeated sampling over time, considering its potential impact on animal welfare and human‒animal interactions. Regarding buccal swabs, they were unable to accurately capture the microbiota shifts during the acidogenic challenge, although we obtained taxonomic bacterial profiles similar to those of the rumen samples after buccal taxa stringent filtering. Finally, we identified microbial markers of SARA both in ET and RC samples, with Dialister spp. also detected as indicators in buccal swab samples. Even though BS samples are not fully representative of rumen samples, they may still be useful for detecting markers of microbiota dysbiosis during nutritional challenges in large-scale studies.

Methods

Animals and diet

The animal trial was conducted at the animal facilities of the INRAE Experimental Unit “Dairy Nutrition and Physiology” (IE PL, 35650 Le Rheu, France, https://doi.org/10.15454/yk9q-pf68). Procedures involving animals were carried out in accordance with the guidelines for animal research of the French Ministry of Agriculture and all other applicable national and European guidelines and regulations for experimentation with animals. The protocol was approved by the Regional Ethics Committee on Animal Experimentation (CREEA) and authorized by the French ministry with reference number APAFiS #26894-2020081715322100_v2.

Six rumen-fistulated multiparous Holstein cows in early lactation were included in the study (mean weight, 686 ± 72 kg). The animal experiment is detailed in a previous publication20. After an adaptation period of 3 weeks (to control diet and barn), the cows received 3 diets distributed twice a day as total mixed rations (TMRs) (Supplementary information 1, Table S6). During the first and third experimental periods (P1 and P3), cows received a control diet with a low amount of production concentrate (12% DM) and starch (18% starch DM). During the second period (P2), cows received a challenging diet corresponding to a high-energy diet (55% DM of concentrate) with a high starch content (29% DM). The diet transitions were gradual: in P2, the high-starch diet was progressively introduced to the cows over 10 days to avoid acute rumen acidosis, and in P3, two days of progressive transition were applied20. Each period lasted four weeks (Supplementary information 1, Figure S8).

This study is reported in accordance with ARRIVE guidelines. We did not use any anesthesia or euthanasia methods in this study.

Sample collection

Rumen content and buccal swabs were collected on Thursdays of each week, during 12 weeks (Supplementary information 1, Figure S8).

Rumen sampling

The rumen content was collected just before the morning feeding, either via esophageal tubing or through the rumen cannula. Esophageal tube placement was performed as previously described20 via a PVC tube 2.5 cm in diameter. A vacuum pump equipped with a glass container was connected to the tube, and the rumen content was collected through vacuum pressure in the tube. The first 200 mL were discarded to avoid contamination with saliva and mucus. Then, approximately 1 L of rumen content was collected. Samples from the rumen cannula were taken to represent the combined reticulum and ventral sac of the rumen (50/50, v/v). The samples contained both fluid and particulate fractions to cover the overall composition of the rumen contents. This sampling corresponded to our reference method for cannula sampling. All samples from both the esophageal tubing and the cannula were filtered through a nylon cloth (400 μm porosity) and then divided into three subsamples: one was treated for analysis of short-chain fatty acids (SCFAs), one for protozoa enumeration, and the other was immediately frozen in liquid nitrogen and transported to the laboratory. The samples were then stored at − 80 °C until DNA extraction for microbiota analysis via qPCR and sequencing. During all the collections, the ruminal pH was measured immediately after sampling.

Buccal swabbing

Buccal swab samples were collected from the mouths of the animals before morning feeding via a dedicated Zymo kit (DNA/RNA Shield Collection Tube w/Swab ref R1109). Two swabs were inserted into the oral cavity of each animal and gently swabbed across the inner side of the cheek for approximately 10 s. The buccal swabs were then placed in a dedicated tube and frozen in liquid nitrogen before being stored at −80 °C.

Microbiota analysis

Protozoa were enumerated in a Neubauer chamber under a microscope after fixation and staining in formaldehyde and methyl green dye solutions as previously described27,49.

DNA was extracted from at least 250 mg of rumen content via the ProSoil Plus Kit (Qiagen, Courtaboeuf, France) according to the manufacturer’s recommendations. The kit procedure involves chemical and mechanical lysis, including a bead-beating homogenization step. For the buccal swabs, DNA was extracted from the total swab using the same Prosoil Plus kit and suspended in a smaller volume in the final step of the kit. DNA yield and quality were determined after Nanodrop 1000 and Qubit spectrophotometric quantifications. The DNA extracts were stored at −20 °C until analysis.

qPCR quantification of microbial populations

Microbial populations were quantified via the qPCR method, with specific primer sets and PCR conditions targeting ribosomal RNA genes of total bacteria, Archaea, rumen fungi and protozoa, as previously described50,51. The PCR targets and primers used are summarized in Supplementary Information 1, Table S7. Standards were used to determine the absolute abundance of each target, expressed as the Log10 number of gene copies per microgram of pelleted rumen when RC and ET were compared and expressed as the log10 number of gene copies per ng of extracted DNA when BS was compared to ET and RC. For total bacteria and for protozoa and fungi, standard curves were prepared according to Mosoni et al.50. and Bayat et al.52. Briefly, for protozoa the standard curve was prepared using pSC-A-amp/kan plasmids (Strataclone PCR cloning kit, Agilent Technologies) containing the near full 18 S rRNA gene from Polyplastron multivesiculatum, Eudiplodinium maggii, and Ostracodinium dentatum mixed in equal amounts. For fungi, the ITS1 fragment from Piromyces spp. was amplified using qPCR primers M13P8 and M13P753 and cloned using the pCR2.1 Topo TA Cloning kit (Invitrogen, Life Technologies, Saint Aubin, France). For bacteria, the standard curve was established using equal amount of the rrs DNA fragment amplified from genomic DNA of 11 bacterial species, as described in Mosoni et al.50. The standard curve targeting methanogenic Archaea was determined using the mcrA DNA fragment amplified from genomic DNA of Methanobrevibacter smithii DSM861 and PCR conditions and primers already described54.

Metataxonomic analysis

Microbiota diversity and taxonomic composition were analysed via 16S rRNA gene and ITS amplicon sequencing. DNA samples were quantified with a Qubit spectrophotometer to adjust concentrations to at least 20 ng/µL, and a volume of 30 µL per sample was sent to the Roy J. Carver Biotechnology Centre (University of Illinois, Urbana-Champaign, USA). The diversity and composition of the rumen and buccal microbiota were studied via high-throughput sequencing with the Illumina NovaSeq SP 250nt pair-end read lane (Illumina, San Diego, CA). The primer sets used were proposed by the Roy J. Carver Biotechnology Centre, and are indicated in Supplementary information 1, Table S7. The DNA regions targeted by these primers are 16S rDNA V4 for bacteria and 349 F/806R for Archaea, and ITS3-ITS4 for fungi. PCR amplification, library construction and NovaSeq Illumina sequencing were carried out by the Roy J. Carver Centre. Bacterial and fungal taxonomic assignment was performed via the rANOMALY55 pipeline based on the DADA2 package and was performed in R 4.3.2 (R Core Team (2021). R: A language and environment for statistical computing. R Foundation for Statistical Computing, Vienna, Austria. URL https://www.R-project.org/) for the pipeline’s steps of filtering, trimming, and dereplication to infer the sample composition and to remove chimeras. Multiple-sequence alignment was performed via the DECIPHER R package56. The SILVA nr v.138 database was used to assign bacterial taxonomies from kingdom to genus. Fungal sequences were assigned using the SILVA 18S fungi and Unite fungi v8.2 databases. Stringent ASV filtering was applied according to Husso et al57. All the diversity analyses were performed with the rANOMALY55 pipeline based on the Phyloseq R package58. Raw ASV abundances were used for the alpha diversity analyses. Beta diversity analyses were performed via a transformed abundance table with DESeq2’s variance stabilizing transformation59. The overall dissimilarity of the microbial community between groups and periods was evaluated with principal coordinate analysis (PCoA) on the basis of Bray‒Curtis dissimilarity. The significance of differences between groups was tested by analysis of similarity (ANOVA). The microbiome differential abundance testing and log2fold change estimation60 were performed with the default multiple-inference correction of DESeq2 (Benjamini‒Hochberg). Indicator species were identified using “multilevel pattern analysis” via the “indicspecies” (v1.7.14) package in R (4.3.2)18,19. This function studies the associations between species patterns and combinations of groups and thus identifies species that are specific to one group with high fidelity. For this purpose, a genus-level identity ASV table was used as input. Each genus ecological niche preference (period at each sampling day) was identified by Pearson’s phi coefficient of association (corrected for unequal sample sizes) using the “indicspecies” package and 10,000 permutations. All the samples were considered independent.

For stringent filtering the buccal swab sequences, ASVs specific from the mouth were identified using the “indicspecies” package in R as explained above. We tested several thresholds to identify and delete the “mouth-specific taxa” from BS sequences (p values ranging from 0.001 to 0.05).

Amplicon sequences were deposited in the NCBI SRA repository under the bioproject number PRJNA1279625.

Statistical analysis

Statistical analyses were performed using GraphPad Prism 10.2.3. Following Villot et al.26 a linear mixed model was applied to identify the variables significantly modified across the 12 weeks of experiment (4 weeks in P1, 4 weeks in P2 and 4 weeks in P3), considering as fixed effects the Week nested in Period and the Sampling location (Rumen cannula RC, esophageal tubing ET and Buccal Swab BS) while animal was considered as a random effect. Week was considered as a repeated measure.

Multiple comparisons were examined with Tukey’s adjustment on log10-transformed microbial qPCR data and protozoal enumeration. Statistical significance was determined at a p value < 0.05, and trends were discussed at a p value < 0.10.

Data availability

Sequencing data have been deposited in the NCBI SRA repository under the bioproject number PRJNA1279625. All other relevant data have been integrated into the manuscript and in the supplementary information files.

References

Huws, S. A. et al. Addressing global ruminant agricultural challenges through Understanding the rumen microbiome: past, present, and future. Front. Microbiol. 9, 2161 (2018).

Newbold, C. J., Ramos-Morales, E. & Review Ruminal Microbiome and microbial metabolome: effects of diet and ruminant host. Animal 14, s78–s86 (2020).

Mizrahi, I., Wallace, R. J. & Moraïs, S. The rumen microbiome: balancing food security and environmental impacts. Nat. Rev. Microbiol. 19, 553–566 (2021).

Monteiro, H. F. et al. Rumen and lower gut microbiomes relationship with feed efficiency and production traits throughout the lactation of Holstein dairy cows. Sci. Rep. 12, 4904 (2022).

Tapio, M., Fischer, D., Mäntysaari, P. & Tapio, I. Rumen microbiota predicts feed efficiency of primiparous nordic red dairy cows. Microorganisms 11, 1116 (2023).

Fatehi, F., Krizsan, S. J., Gidlund, H. & Huhtanen, P. A comparison of ruminal or reticular digesta sampling as an alternative to sampling from the Omasum of lactating dairy cows. J. Dairy. Sci. 98, 3274–3283 (2015).

Huhtanen, P., Brotz, P. G. & Satter, L. D. Omasal sampling technique for assessing fermentative digestion in the forestomach of dairy cows2. J. Anim. Sci. 75, 1380–1392 (1997).

da Cunha, L. L. et al. Characterization of rumen Microbiome and metabolome from oro-esophageal tubing and rumen cannula in Holstein dairy cows. Sci. Rep. 13, 5854 (2023).

Pathak, N. et al. Comparing rumen fluid collection methods on fermentation profile and microbial population in lactating dairy cows. JDS Commun. https://doi.org/10.3168/jdsc.2024-0566 (2024).

Paz, H. A., Anderson, C. L., Muller, M. J., Kononoff, P. J. & Fernando, S. C. Rumen bacterial community composition in Holstein and Jersey cows is different under same dietary condition and is not affected by sampling method. Frontiers Microbiology 7, (2016).

Shen, J. S., Chai, Z., Song, L. J., Liu, J. X. & Wu, Y. M. Insertion depth of oral stomach tubes May affect the fermentation parameters of ruminal fluid collected in dairy cows. J. Dairy. Sci. 95, 5978–5984 (2012).

de Assis Lage, C. F. et al. Comparison of two sampling techniques for evaluating ruminal fermentation and microbiota in the planktonic phase of rumen digesta in dairy cows. Front. Microbiol. 11, 618032 (2020).

Hagey, J. V., Laabs, M., Maga, E. A. & DePeters, E. J. Rumen sampling methods bias bacterial communities observed. PLOS ONE. 17, e0258176 (2022).

Amin, N. et al. Evolution of rumen and oral microbiota in calves is influenced by age and time of weaning. Anim. Microbiome. 3, 31 (2021).

Kittelmann, S., Kirk, M. R., Jonker, A., McCulloch, A. & Janssen, P. H. Buccal swabbing as a noninvasive method to determine bacterial, archaeal, and eukaryotic microbial community structures in the rumen. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 81, 7470–7483 (2015).

Young, J. et al. Validating the use of bovine buccal sampling as a proxy for the rumen microbiota by using a time course and random forest classification approach. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 86, e00861–e00820 (2020).

Zhang, J. et al. Effect of dietary forage to concentrate ratios on dynamic profile changes and interactions of ruminal microbiota and metabolites in Holstein heifers. Front. Microbiol. 8, 2206 (2017).

De Cáceres, M. & Legendre, P. Associations between species and groups of sites: indices and statistical inference. Ecology 90, 3566–3574 (2009).

Legendre, P. & De Cáceres, M. Beta diversity as the variance of community data: dissimilarity coefficients and partitioning. Ecol. Lett. 16, 951–963 (2013).

Boudon, A. et al. Oral-stomach sampling to replace rumen-fistulated animals in ruminant nutrition research - a case study. 01.17.633359 Preprint at (2025). https://doi.org/10.1101/2025.01.17.633359 (2025).

Miura, H. et al. Application of minion amplicon sequencing to buccal swab samples for improving resolution and throughput of rumen microbiota analysis. Frontiers Microbiology 13, (2022).

Tapio, I. et al. Oral samples as Non-Invasive proxies for assessing the composition of the rumen microbial community. PLOS ONE. 11, e0151220 (2016).

Song, J. et al. Effects of sampling techniques and sites on rumen Microbiome and fermentation parameters in Hanwoo steers. 28, 1700–1705 (2018).

Ramos-Morales, E. et al. Use of stomach tubing as an alternative to rumen cannulation to study ruminal fermentation and microbiota in sheep and goats. Anim. Feed Sci. Technol. 198, 57–66 (2014).

Fernández-Pato, A. et al. Choice of DNA extraction method affects stool Microbiome recovery and subsequent phenotypic association analyses. Sci. Rep. 14, 3911 (2024).

Sauvant, D. & Peyraud, J. L. Calculs de ration et évaluation du risque d’acidose. INRAE Productions Animales. 23, 333–342 (2010).

Villot, C., Meunier, B., Bodin, J., Martin, C. & Silberberg, M. Relative reticulo-rumen pH indicators for subacute ruminal acidosis detection in dairy cows. Animal 12, 481–490 (2018).

Belanche, A. et al. Shifts in the rumen microbiota due to the type of carbohydrate and level of protein ingested by dairy cattle are associated with changes in rumen fermentation. J. Nutr. 142, 1684–1692 (2012).

Elmhadi, M. E., Ali, D. K., Khogali, M. K. & Wang, H. Subacute ruminal acidosis in dairy herds: Microbiological and nutritional causes, consequences, and prevention strategies. Anim. Nutr. 10, 148–155 (2022).

Zhang, T. et al. Responsive changes of rumen Microbiome and metabolome in dairy cows with different susceptibility to subacute ruminal acidosis. Anim. Nutr. 8, 331–340 (2021).

Khafipour, E., Li, S., Plaizier, J. C. & Krause, D. O. Rumen Microbiome composition determined using two nutritional models of subacute ruminal acidosis. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 75, 7115–7124 (2009).

McCann, J. C. et al. Induction of subacute ruminal acidosis affects the ruminal Microbiome and epithelium. Frontiers Microbiology 7, (2016).

Plaizier, J. C. et al. Changes in microbiota in rumen digesta and feces due to a Grain-Based subacute ruminal acidosis (SARA) challenge. Microb. Ecol. 74, 485–495 (2017).

Stevenson, D. M. & Weimer, P. J. Dominance of prevotella and low abundance of classical ruminal bacterial species in the bovine rumen revealed by relative quantification real-time PCR. Appl. Microbiol. Biotechnol. 75, 165–174 (2007).

Tajima, K. et al. Diet-dependent shifts in the bacterial population of the rumen revealed with real-time PCR. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 67, 2766–2774 (2001).

Tajima, K. et al. Rumen bacterial community transition during adaptation to High-grain diet. Anaerobe 6, 273–284 (2000).

Avgustin, G., Wallace, R. J. & Flint, H. J. Phenotypic diversity among ruminai isolates of prevotella ruminicola: proposal of prevotella brevis sp. Nov., prevotella Bryantii sp. Nov., And prevotella albensis sp. Nov. And redefinition of prevotella ruminicola. Int. J. Syst. Evol. MicroBiol. 47, 284–288 (1997).

Hitch, T. C. A. et al. A taxonomic note on the genus Prevotella: description of four novel genera and emended description of the genera Hallella and Xylanibacter. Syst. Appl. Microbiol. 45, 126354 (2022).

Čipčić Paljetak, H. et al. Gut microbiota in mucosa and feces of newly diagnosed, treatment-naïve adult inflammatory bowel disease and irritable bowel syndrome patients. Gut Microbes 14, 2083419 .

Mu, Y., Qi, W., Zhang, T., Zhang, J. & Mao, S. Multi-omics analysis revealed coordinated responses of rumen Microbiome and epithelium to High-Grain-Induced subacute rumen acidosis in lactating dairy cows. mSystems 7, e0149021 (2022).

Guo, T. et al. Rumen bacteria abundance and fermentation profile during subacute ruminal acidosis and its modulation by Aspergillus oryzae culture in RUSITEC system. Fermentation 8, 329 (2022).

Takizawa, S. et al. Rumen microbial composition associated with the non-glucogenic to glucogenic short-chain fatty acids ratio in Holstein cows. Anim. Sci. J. 94, e13829 (2023).

Myer, P. R., Smith, T. P. L., Wells, J. E., Kuehn, L. A. & Freetly, H. C. Rumen Microbiome from steers differing in feed efficiency. PLOS ONE. 10, e0129174 (2015).

Amin, A. B., Zhang, L., Zhang, J. & Mao, S. Metagenomics analysis reveals differences in rumen microbiota in cows with low and high milk protein percentage. Appl. Microbiol. Biotechnol. 107, 4887–4902 (2023).

Hünerberg, M. et al. Impact of ruminal pH on enteric methane emissions. J. Anim. Sci. 93, 1760–1766 (2015).

Costa-Roura, S., Villalba, D. & Balcells, J. De La fuente, G. First steps into ruminal microbiota robustness. Anim. (Basel). 12, 2366 (2022).

Weimer, P. J. Redundancy, resilience, and host specificity of the ruminal microbiota: implications for engineering improved ruminal fermentations. Front. Microbiol. 6, 296 (2015).

Ricci, S. et al. Progressive microbial adaptation of the bovine rumen and hindgut in response to a step-wise increase in dietary starch and the influence of phytogenic supplementation. Front. Microbiol. 13, 920427 (2022).

Silberberg, M. et al. Repeated acidosis challenges and live yeast supplementation shape rumen microbiota and fermentations and modulate inflammatory status in sheep. Animal 7, 1910–1920 (2013).

Mosoni, P., Martin, C., Forano, E. & Morgavi, D. Long-term defaunation increases the abundance of cellulolytic Ruminococci and methanogens but does not affect the bacterial and methanogen diversity in the rumen of sheep. J. Anim. Sci. 89, 783–791 (2011).

Mosoni, P., Chaucheyras-Durand, F., Béra-Maillet, C. & Forano, E. Quantification by real-time PCR of cellulolytic bacteria in the rumen of sheep after supplementation of a forage diet with readily fermentable carbohydrates: effect of a yeast additive. J. Appl. Microbiol. 103, 2676–2685 (2007).

Bayat, A. R. et al. Effect of camelina oil or live yeasts (Saccharomyces cerevisiae) on ruminal methane production, rumen fermentation, and milk fatty acid composition in lactating cows fed grass silage diets. J. Dairy. Sci. 98, 3166–3181 (2015).

Lwin, K. O., Hayakawa, M., Ban-Tokuda, T. & Matsui, H. Real-Time PCR assays for monitoring anaerobic fungal biomass and population size in the rumen. Curr. Microbiol. 62, 1147–1151 (2011).

Ohene-Adjei, S., Teather, R. M., Ivan, M. & Forster, R. J. Postinoculation protozoan establishment and association patterns of methanogenic archaea in the ovine rumen. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 73, 4609–4618 (2007).

Theil, S. & Rifa, E. rANOMALY: amplicon wOrkflow for microbial community analysis. F1000Res 10, 7 (2021).

Wright, E. S. & Using DECIPHER v2.0 to analyze big biological sequence data in R. R J. 8, 352–359 (2016).

Husso, A. et al. The composition of the perinatal intestinal microbiota in horse. Sci. Rep. 10, 441 (2020).

McMurdie, P. J. & Holmes, S. Phyloseq: an R package for reproducible interactive analysis and graphics of Microbiome census data. PLOS ONE. 8, e61217 (2013).

Love, M. I., Huber, W. & Anders, S. Moderated Estimation of fold change and dispersion for RNA-seq data with DESeq2. Genome Biol. 15, 550 (2014).

Anders, S. & Huber, W. Differential expression analysis for sequence count data. Genome Biol. 11, R106 (2010).

Acknowledgements

This research was supported by the INRAE Animal Physiology and Livestock Systems and the Microbiology and Food Chain divisions. The authors also thank ADISSEO, CARGILL, CCPA-DELTAVIT, CMI-ROUILLER, LALLEMAND, MG2MIX, PHILEO-LESAFFRE, and PROVIMI for funding and helpful discussion. The authors thank Philippe Lamberton for his help in the design of the experiment and his expertise in the formulation of acidogenic diets; Jean-Yves Thebault, Jean-Luc and Anthony Herouet for animal care and sampling at the experimental farm; and Maryline Lemarchand, Séverine Urvoix and Maryvonne Texier for sample preparation. The authors are grateful to Jeanne Danon and Alexandra Durand from MEDIS (INRAE), Yacine Lebbaoui and Laurie Guillot (LALLEMAND) and Dominique Graviou and Yassmine Radouani from UMRH (INRAE) for sample treatments and analyses. They thank Diego Morgavi and Milka Popova for helpful discussions.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

AB, PN, MS and EF designed the animal experiment and sampling. AB and MS contributed to animal sampling. LD, FCD, MS and EF treated and analysed the samples. PR, LD, FCD, MS and EF analysed the data. LD, FCD and EF interpreted the data. EF wrote the first draft of the manuscript. PR, LD, FCD, MS and EF prepared the figures. PN was the project administrator. All the authors reviewed, edited and approved the manuscript.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Financial support statement

This research was supported by the INRAE Animal Physiology and Livestock Systems Division and the INRAE Microbiology and Food Chain division, as well as the companies ADISSEO, CARGILL, CCPA-DELTAVIT, CMI-ROULLIER, LALLEMAND, MG2MIX, PHILEO-LESAFFRE, and PROVIMI.

Additional information

Publisher’s note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Supplementary Information

Below is the link to the electronic supplementary material.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if you modified the licensed material. You do not have permission under this licence to share adapted material derived from this article or parts of it. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Dunière, L., Ruiz, P., Chaucheyras-Durand, F. et al. Evaluation of esophageal tubing and buccal swabbing versus rumen cannula to characterize ruminal microbiota in cows fed contrasting diets. Sci Rep 15, 34582 (2025). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-18063-1

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-18063-1