Abstract

Polycystic ovary syndrome; is a prevalent endocrine disorder, characterized by hormonal imbalances, inflammation, and oxidative stress. Natural remedies, including Murcott and Merav (Citrus reticulata varieties, Family: Rutaceae) fruits and leaves extracts, have demonstrated promising therapeutic effects in alleviating these symptoms. This study aimed to evaluate the efficacy of these extracts concerning their metabolomics in modulating hormonal levels, enhancing lipid metabolism while alleviating inflammation and oxidative stress in mice with polycystic ovary syndrome through the regulation of miR-33b-5P and miR-145 gene expression. UPLC-T-TOF-MS/MS analysis identified and quantified One hundred-seven bioactive metabolites. These metabolites were categorized into various classes according to their chemical structures, including phenolic types such as 68 flavonoids, 4 coumarins and 7 phenolic acids in addition to, 3 nitrogenous compounds, 7 terpenes and terpenoids, 6 fatty acids and their conjugates and 12 miscellaneous compounds. and various biochemical assays were performed. Blood samples were collected to measure plasma FSH, testosterone, LH, and lipid profiles. Oxidative stress biomarkers, including malondialdehyde (MDA) and superoxide dismutase (SOD), and COX-2 and NF-kB levels were assessed using ELISA kits. Micro-RNA gene expression, miR-33b-5P and miR-145, related to inflammation and oxidative stress, was analyzed using qRT-PCR. Ovarian tissues were examined histologically to assess morphological changes. These findings highlight that Murcott and Merav extracts could be a promising alternative natural treatment for PCOS, balancing hormonal levels, improving lipid profiles, and reducing inflammation and oxidative stress. Merav leaves emerged as the most promising candidate for PCOS therapy, attributed to their high levels of methylated kaempferol, a key bioactive flavonoid.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

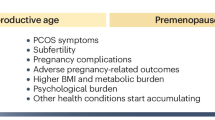

Polycystic ovary syndrome (PCOS) is a prevalent endocrine condition that affects around 20% of women during their reproductive years. It is characterized by the presence of multiple ovarian cysts on ultrasound and is often accompanied by symptoms such as menstrual irregularities, excess androgen production, and challenges with fertility. It is a leading cause of female infertility and is linked to long-term metabolic and inflammatory complications. Up to 70% of affected women remain undiagnosed1,2. The condition is characterized by hormonal imbalances, including low follicle-stimulating hormone (FSH), elevated luteinizing hormone (LH), and high testosterone levels, which disrupt ovarian function and exacerbate symptoms such as irregular ovulation and excessive hair growth. Moreover, inflammation and oxidative stress are critical contributors to PCOS pathology, with decreased antioxidant defenses [reduced glutathione (GSH), superoxide dismutase (SOD), and catalase (CAT)] while, increased malondialdehyde (MDA), Cyclooxygenase-2 (COX-2), and Nuclear factor kappa-light-chain-enhancer of activated B cells (NF-kB) levels, contributing to disease progression3,4.

While pharmacological treatments for PCOS are effective in symptom management, they are frequently accompanied by undesirable side effects. This has led researchers to explore alternative therapies with better tolerability. Medicinal plants have gained attention due to their ethnopharmacological relevance and diverse phytochemical constituents, which may offer comparable benefits with reduced side effects. Herbs such as Matricaria chamomilla (Chamomile), Glycyrrhiza glabra (liquorice), Panax ginseng, and Mentha spicata (spearmint) have shown efficacy in alleviating PCOS-related issues. For instance, spearmint has been found to reduce testosterone levels and improve ovarian histology, while ginseng and liquorice help regulate blood glucose and lipid profiles, common comorbidities associated with PCOS but chamomile may help alleviate PCOS-related symptoms in ovarian tissue, promote the development of uterine follicles, and enhance LH secretion5. Also, Vitex agnus-castus (chasteberry) is well documented for its ability to regulate and maintain a healthy balance between estrogen and progesterone levels, thereby promoting menstrual regularity and reducing ovarian cyst formation. The capacity to neutralize free radicals and suppress inflammation of Curcuma longa (turmeric) and Zingiber officinale (ginger) further contribute to reducing oxidative stress, which is often elevated in PCOS patients. Additionally, plants like Foeniculum vulgare (fennel) and Trigonella foenum-graecum (fenugreek) have been noted for their estrogenic properties and ability to normalize menstrual cycles, making them valuable adjuncts in PCOS treatment6,7,8.

C. reticulata var. Murcott and C. reticulata var. Merav belong to the family Rutaceae, are both tangor hybrids and are economically valuable citrus fruits. Murcott, also known as “Honey Tangerine,” is a late-maturing variety (December–March) known for its large, juicy, seed-rich fruit with easy-to-peel skin9. In contrast, Merav is a smaller, seedless, sweeter mandarin with a deep orange, glossy appearance, easy to peel, and typically segmented into 7 to 14 parts10. C. reticulata was rich in phenolic compounds that are present in major concentrations11 while phenolic compounds have a potential activity against PCOS12. Kaempferol and its derivatives, a natural flavonoid, have shown promising potential in managing PCOS through their progestogenic and gene-regulatory effects. They act as a phytoprogestin that selectively modulates progesterone-related signaling pathways and downregulates PCOS-associated genes in mouse uterine tissue13. Additionally, kaempferol and related flavonoids have been shown in animal studies to improve ovarian structure and reduce hormonal imbalances, such as elevated LH and free testosterone levels14. Methylation of flavonoids such as kaempferide can show an enhanced bioavailability and metabolic stability due to the methylated form showing improved absorption compared to non-methylated counterparts15. Also, structural modifications like methylation may amplify anti-androgenic and antioxidant effects, which are key mechanisms in PCOS management15,16. This study aims to characterize the metabolite profile of Murcott and Merav fruit and leaf extracts using ultra-performance liquid chromatography combined with electrospray ionization and triple time-of-flight mass spectrometry (UPLC-ESI-T-TOF-MS/MS) and assess their impact on oxidative stress, hormonal imbalances, and ovarian function in PCOS models. By investigating their potential as natural treatments for PCOS, this research contributes to the development of alternative, plant-based therapeutic strategies.

Materials and methods

Plant material and extraction process

Leaves and ripe fruits rind of C. reticulata Blanco Cultivars; Merav and Murcott were collected from El-Batoul Farm for Citrus fruits, Nubariah City, El-Beheira Governorate, Egypt in June 2023 for the leaves and in February 2024 for the ripe rind. Professor Dr. Wafaa Amer, who specializes in Taxonomy at Cairo University in Egypt, confirmed their identities. In the herbarium of the Department of Pharmacognosy and Medicinal Plants, Faculty of Pharmacy (Girls), Al-Azhar University, four samples have been placed with vouchers CRL23 for Merav leaves in 2023, CML23 for Murcott leaves in 2023, CRF24 for Merav fruit rind in 2024 and CMF24 for Murcott fruit rind in 2024.

Leaves and ripe fruits rind of C. reticulata Blanco Cultivars; Merav and Murcott (2 kg, each) were powdered and extracted separately in a Soxhlet (Alderich® soxhlet, Darmstadt, Germany) with methanol (3 × 5 L, 70%) under reflux (65 °C). After filtration, the methanol extracts were concentrated at 45 °C under vacuum using a BÜCHI Rotavapor® system to obtain a brown crude extract of 160, 200, 190 and 250 g for Murcott fruit (MTF), Murcott leaves (MTL), Merav fruit (MVF) and Merav leaves (MVL), respectively. The obtained dried extracts were used for biological and chemical investigations17. All methods were carried out in accordance with relevant guidelines and regulations.

The dose of 500 mg/kg b.w. for Murcott and Merav fruit and leaf extracts was selected based on dose ranges commonly used in phytopharmacological investigations evaluating the anti-inflammatory, antioxidant, and hormone-modulating activities of citrus-derived phenolics. According to Zhang et al. (2022)14 and Yuan et al. (2025)12plant extract doses between 200 and 600 mg/kg b.w. have shown reproducible therapeutic benefits in PCOS animal models.

UPLC-ESI-T-TOF-MS/MS analysis

UPLC-ESI-T-TOF-MS/MS was employed to analyze active fractions (MTL, MVL, MTF, and MVF) at the Proteomics and Metabolomics Lab, Children’s Cancer Hospital Egypt 57,357. The analysis utilized a Waters UPLC system with an X Select HSS T3 column (2.5 μm, 2.1 × 150 mm) and an in-line filter (0.5 μm pore size, 3.0 mm diameter) to prevent particulate contamination. Sample preparation involved dissolving 50 mg of each extract in a 50:25:25 mixture of deionized water, methanol, and acetonitrile, followed by vortexing, sonication, and centrifugation. A 10 µL aliquot of the prepared solution (2.5 µg/µL) was injected for analysis. Using UPLC-ESI-T-TOF-MS/MS, phytochemical profiling was achieved under both negative and positive ionization conditions. A gradient elution was performed with solvent A (5 mM ammonium formate buffer, pH 8, with 1% methanol) and solvent B (100% acetonitrile) at a flow rate of 0.3 mL/min. Data collection and analysis were conducted using Peak View 2.2 and MS-DIAL 4.6. Tentative compound identification was achieved by comparing retention times, molecular masses, and fragmentation patterns against databases including Respect (positive and negative), the Human Metabolome Database (HMDB), and NIST libraries, as well as published literature18,19,20.

Experimental design

Forty-two albino mice, weighing 35 ± 2.5 g each, were purchased from the Cancer Institute at Cairo University. Animal studies were performed in accordance with ARRIVE guidelines with ethical approval granted by the Research Ethics Committee of the Faculty of Pharmacy for Girls, Al-Azhar University, Egypt (Ethics Approval No. 468).

The mice were housed in polypropylene cages with industry-standard humidity levels and a natural light-dark cycle. They had access to water and normal pellets, which were supplied by the Cantacuzino Institute in Bucharest, Romania. Dyets Inc. (Bethlehem, PA, USA) provided the regular diet. The high-fat diet (HFD) consisted of 200 g of fat per kg and 1% (w/w) cholesterol, as previously described by Shahid et al.21 and Kafali et al.22 to induce PCOS-like metabolic disturbances in rodents. Seven groups were formed by randomly dividing the mice, with six mice in each group, as illustrated in (Table 1). At the end of the experiment, cervical dislocation was used for euthanizing animals. It involved the rapid dislocation of the cervical vertebrae from the skull. The procedure is performed swiftly to ensure immediate unconsciousness and death.

Body weights were recorded every two weeks. At the end of the experiment, the mice were anesthetized with 50 mg of thiopental sodium and then sacrificed for blood and tissue collection. Blood samples were collected in fluoride tubes and centrifuged24. Plasma levels of FSH, testosterone, and LH were measured using ELISA kits from Abbexa (UK), My Biosciences (USA), and Abcam (USA). Plasma COX-2 levels were determined using an ELISA kit (ab210574, Abcam, USA). Immediately after isolation, the ovaries were washed with saline and divided into three sections. The first Sect. (100 mg) was homogenized in 1 ml of phosphate-buffered saline (pH 7.4) for 15 min. The homogenate was split into two parts, with the first part being centrifuged at 1000 rpm and filtered. The obtained supernatant was used for the estimation of GSH, SOD, CAT and MDA. A chloroform-methanol mixture (2:1, 1 ml) was used to extract the second portion of the homogenate (0.2 ml), and the extract was then concentrated using a nitrogen stream. This extract was used for the estimation of ovarian NF-kβ and MDA using ELISA kits (ab176648, Abcam, USA) and (MBS741034, My Biosciences, USA), respectively25,26,27.

Quantitative Real-Time PCR

Using Sepasol-RNA1Super (Nakarai Tesque), total RNA was extracted from a portion of the ovarian tissue designated for gene expression analysis as per the manufacturer’s protocol. Real-time quantitative PCR (RT-PCR) was used to assess miR-33b-5P and miR-145 gene expression in Sects. (10–15 g) of the recovered RNA. The PCR reaction mixture comprised PCR buffer, 1.5 mM MgCl2, 0.2 mM of each dNTP, and 0.4 µM of the appropriate primers (Table 2), with assays conducted in a 50 µl single-plex mixture. The PCR conditions included 40 cycles of 95 °C for 15 s and 60 °C for 1 min, with pre-incubation steps at 50 °C for 2 min and 95 °C for 10 min. GAPDH mRNA was used for internal control normalization28.

Histological assessment

After fixation in 10% neutral formalin, the third part of the ovarian tissue was dehydrated in graded alcohol, embedded in paraffin, and sectioned. The slices were stained with Hematoxylin and Eosin (H&E), mounted on slides, and analyzed under a light microscope according to the Bancroft and Steven method29.

Statistical evaluation

Gene expression was measured quantitatively by PCR in triplicate, and spectrophotometric and ELISA analyses were conducted in six separate replicates. The results were presented as mean ± standard deviation (SD). Statistical comparisons were made using SPSS version 20, applying one-way ANOVA followed by the Bonferroni post hoc test for multiple comparisons. A p-value of < 0.05 was considered statistically significant30.

Results and discussion

UPLC-T-TOF-MS/MS analysis of Murcott and Merav leaves and fruits

The leaves and fruits rind of C. reticulata var. Murcott and Merav showed a wide variety of polyphenolic metabolites, according to the total ion chromatograms (TIC) in negative and positive modes (Figs. 1 and 2). For the identified metabolites, Table 3 presents the retention times (Rt), observed molecular masses m/z, molecular formulas (MFs), selected daughter fragments and error (ppm) values. The elution order was used to assign the peak numbers. In total, one hundred-seven metabolites were detected of diverse chemical classes in both parts of Murcott and Merav varieties extracts. The identification of these metabolites is predicated on the confirmation of the aforementioned corresponding parameters in conjunction with the extracted ion chromatograms (XIC), tandem mass spectral selective fragments in MS1 and/or MS2 two-stage fragmentation spectra, and their complete correspondence with the information reported for each identified metabolite and the corresponding convenient library database (MoNA; Mass Bank of North America). These metabolites were categorized into various classes according to their chemical structures, including phenolic types such as 68 flavonoids, 4 coumarins and 7 phenolic acids. In addition to, 3 nitrogenous compounds, 7 terpenes and terpenoids, 6 fatty acids and their conjugates and 12 miscellaneous compounds. Numerous flavonoid types, including flavanones, flavones, isoflavones, flavonols, anthocyanidins, aurones, chalcones, and their related glycosides, were found in C. reticulata. Sixteen flavonoid aglycone and/or their glycosides were present in all extracts of MTL, MTF, MVL and MVF represented in Table 3 peaks ID. (1/2/5/6/7/8/14/15/24/28/34/37/54/56/59/64). In addition, there are twenty-three flavonoid aglycone and/or glycosides found in the fruits rind of Murcott and/ or Merav while absent in their leaves (3/4/16/20/22/25/26/27/29/32/36/38/39/43/44/46/51/58/60/62/63/65/67). Twelve were detected only in MTL and/ or MVL (9/17/18/23/30/35/40/45/47/49/52/57).

Flavanones

As shown in Table 3, a total of nine flavanones were identified. Six of these were found across all four extracts, corresponding to peaks 1, 2, 5, 6, 7, and 8. Peaks 3 and 4 were detected only in the MTF extract, while the ninth peak appeared exclusively in the MTL extract. Naringenin, a flavanone predominantly found in Citrus fruits, was assigned to peak (7). Its MS² spectrum displayed a deprotonated molecular ion [M–H]⁻ at m/z 271.0605, with two characteristic daughter ions at m/z 151.0036 [M − H−C₈H₈O]⁻ and m/z 119.0498 [M − H−C₇H₄O₄]⁻, which were created by the Retro Diels-Alder reaction on the chemical bonds 1 and 331. The second flavanone common to all four extracts was peak (1), which displayed a deprotonated ion [M–H]⁻ at m/z 433.1185. The MS² spectrum showed a major fragment ion at m/z 271.0610 [M − H−162]⁻, indicating the loss of a hexose moiety and suggesting naringenin as the aglycone. Protonated ions [M + H]⁺ at m/z 435.1262 and aglycone ion at m/z 273.0559 [M + H − 162]⁺ were also detected. The fragmentation pattern matched well with the database for naringenin 7-O-hexoside32. Similarly, peak (6), present in all four extracts, showed a protonated molecular ion [M + H]⁺ at m/z 595.2019 and a deprotonated ion [M–H]⁻ at m/z 593.1902. A characteristic aglycone ion appeared at m/z 287.0906 [M + H − 309]⁺, suggesting the compound is isosakuranetin 7-O-neohesperidoside, an O-methylated flavonoid and a 4’-methoxy derivative of naringenin33. Peak (8) showed a deprotonated molecular ion [M–H]⁻ at m/z 301.0720 and a protonated ion [M + H]⁺ at m/z 303.0844. Its MS² spectrum exhibited a key fragment at m/z 286.0478 [M–H–CH₃]⁻ and additional fragments matching the reported fragmentation of hesperetin, the 4’-methoxy derivative of eriodictyol34. Peak (5) displayed [M–H]⁻ at m/z 609.1833 and [M + H]⁺ at m/z 611.2517. The MS² spectrum revealed a fragment at m/z 301.0713 [M–H–rutinoside]⁻, characteristic of the hesperetin aglycone. Based on the structure, it was identified as hesperidin, a disaccharide derivative of hesperetin linked via a glycosidic bond to a rhamnosyl-glucosyl moiety35. Peak (4), present only in MTF showed a deprotonated molecular ion [M–H]⁻ at m/z 609.1738. The MS² spectrum exhibited a fragment at m/z 301.0713 [M–H − 308]⁻, corresponding to the loss of a neohesperidoside moiety (308 Da), characteristic of the hesperetin aglycone. Thus, it was tentatively identified as hesperetin 7-O-neohesperidoside35. Peak (2), present in all four extracts, showed a deprotonated molecular ion [M–H]⁻ at m/z 595.1640. The MS² spectrum revealed product ions at m/z 449.1302 [M–H–146]⁻ and 287.0571 [M–H–308]⁻, indicating losses of rhamnose and neohesperidoside moieties, respectively. It was tentatively identified as eriodictyol 7-O-neohesperidoside (neoeriocitrin)31. Finally, flavanomarein, eluted exclusively from MTF (peak 3), exhibited a molecular ion [M–H]⁻ at m/z 449.1027. The MS² spectrum showed fragment ions at m/z 287.0549 [M–H–glucose]⁻ and 269.0427 [M–H–glucose–H₂O]⁻, along with cleavage fragments at m/z 151.01132 and 135.0497 due to cleavage of the C-ring, allowing for tentative identification as isookanin 7-O-hexoside36.

Chalcones

Three chalcones were identified (Table 3), all exhibiting fragmentation patterns similar to those of flavanones. Marein (peak 66) was detected exclusively in Merav extracts and displayed a molecular ion [M–H]⁻ at m/z 449.0889 and a fragment at m/z 287.2334 [M–H–162]⁻, corresponding to the loss of a glucose moiety. Based on these data, it was tentatively identified as okanin 4’-O-hexoside (marein)36. Neohesperidin dihydrochalcone (peak 67) was detected only in MTF, its MS spectrum showed a molecular ion [M–H]⁻ at m/z 611.1354 along with characteristic fragment ions resulting from the sequential loss of rhamnose and glucose units, as well as multiple (CH₂O) losses typical of C-glycosides37. Additionally, phlorizin (peak 68) was identified exclusively in Murcott extracts. It exhibited a protonated molecular ion [M + H]⁺ at m/z 437.1937 and a deprotonated ion [M–H]⁻ at m/z 435.2028, releasing a major fragment at m/z 273.1481 [M–H–162]⁻, corresponding to the loss of a hexosyl moiety, thus confirming its identity as phlorizin38.

Flavones

The main fragmentation pathway for flavone aglycones is the retro-Diels-Alder (RDA) reaction, often accompanied by the loss of small neutral molecules such as H₂O, CO, CO₂, and C₃O₂. In this study, fifteen flavones (peaks 10–24) were identified, mainly corresponding to luteolin and apigenin derivatives. Among the luteolin derivatives, peak 24 was identified as luteolin (5,7,3’,4’-tetrahydroxyflavone), showing strong signals at [M + H]+ m/z 287.0881 and [M-H]− m/z 285.0768, with fragmentation patterns consistent with known standards39. Peak 10 was assigned to luteolin 7,3’-di-O-hexoside ([M-H]− at m/z 609.0918), with a characteristic fragment ion at m/z 283.0968 [M-3 H-2 × 162]- identified through the loss of two hexosyl units40. Peaks 11 and 12 were identified as luteolin 8-C-glucoside (orientin) and luteolin 6-C-glucoside (isoorientin), respectively, both displaying a [M-H]− ion at m/z 447.0936 and 447.0912, respectively. And distinguished by characteristic sugar cleavages ([M-H-90]− and [M-H-120]−) in their MS² spectra41 (Table 3). Peak 22 was confirmed as luteolin 4’-O-hexoside ([M + H]+ at m/z 449.1597), based on the observed loss of a glucose moiety42.

Regarding apigenin derivatives, peak 14 was identified as apigenin 8-C-glucoside (vitexin) with [M + H]+ at m/z 433.1492, characterized by typical C-type hexoside fragment losses43. Peak 15 corresponded to apigenin 7-O-neohesperidoside (rhoifolin) ([M-H]− at m/z 577.1533), fragmenting to yield apigenin ([m/z 269.0453 M-H-146-162]-)44. Peak 18 was identified as apigenin 7-O-hexoside ([M-H]− at m/z 431.0963), showing the loss of a hexosyl moiety (m/z 268.-390 [M-2 H-162]-)45. Peak 20 was assigned to acacetin 7-O-neohesperidoside ([M-H]− at m/z 591.1814) based on the loss of a neohesperidoside group45while peak 23 was confirmed to be apigenin aglycone ([M-H]− at m/z 269.0452) by characteristic C-ring cleavages (m/z 117.0344 and 151.0038)46. Peak 19 was identified as acacetin (the 4’-methyl ether derivative of apigenin) with a deprotonated molecular ion at m/z 283.062047, and peak 21 corresponded to acacetin 7-O-rutinoside (linarin) ([M-H]− at m/z 591.3115), indicated by the loss of a rutinoside moiety20. Finally, peak 17 was identified as baicalein 7-O-glucuronide ([M-H]− at m/z 445.1099), based on sequential neutral losses of CO, CO₂, H₂O, and a glucuronide moiety39.

Isoflavones

Six isoflavones (peaks 25–30) were identified as either aglycones or glycosides. Peak 25, detected only in MVF, exhibited a protonated molecular ion at m/z 255.1450. Its Ms2 spectrum exhibited product ions at m/z 236.9890 [M + H-H2O]+, 165.9184 [M + H-H2O-CO-CO2]+and 122.9401 [M + H-3CO2]+ all these data matched with daidzein48. Peak 28 was found in all samples. It demonstrated a deprotonated molecular ion at m/z 415.1227 [M − H]−. The MS² spectrum revealed a major fragment ion at m/z 371.1811 [M − H−CO2]−, aligning with puerarin (daidzein 8-C-hexoside)48. Peaks 27 and 29 were observed in both MTF and MVF. Peak 27 showed a molecular ion at m/z 271.1186 [M + H]+, with fragment ions resulting from losses of water (m/z 252.9485 [M + H − H2O]+) and carbon monoxide (m/z 242.9196), supporting its identification as genistein49. Peak 26, present only in MTF, exhibited a precursor ion at m/z 431.1562. Fragmentation produced ions at m/z 269.1088 (loss of glucosyl group, − 162 Da) and 226.9483, with further loss yielding a fragment at m/z 254.0554 (loss of CH₃ and CO). This matched the reported pattern for ononin50. Peak 29 was assigned to 5-hydroxy ononin (sissotrin), showing a protonated ion at m/z 447.1677 [M + H]+. Its MS² spectrum displayed the aglycone ion at m/z 285.1139 [M + H − 162]+, indicating the loss of a glucosyl group50. Finally, Peak 30, detected only in MVL, showed a deprotonated ion at m/z 267.1938 (C₁₆H₁₂O₄). Fragmentation led to four product ions at m/z 252.0462 (loss of CH₃, − 15 Da), 224.0521 (loss of CH₃+CO, − 43 Da), 211.0458 (loss of 2CO, − 56 Da), and 195.0514 (loss of CO + CO₂, − 72 Da), identifying it as formononetin51.

Flavonols

In the two plants studied, a total of twenty-six flavonols were detected, including eight kaempferol derivatives, nine quercetin derivatives, three isorhamnetin derivatives, two syringetin derivatives, two myricetin derivatives, and individual detections of taxifolin and gossypin. Taxifolin was identified exclusively in the MTF sample (peak 32) with a molecular ion at m/z 305.1297 [M + H]+ and a characteristic fragment at m/z 287.1295 [M + H–18]+, consistent with loss of H₂O52. Two peaks were attributed to myricetin derivatives; peak 31, identified as myricetin aglycone, was present in MTL, MVL, and MVF), showing [M + H]+ at m/z 319.0969 and [M–H]– at m/z 317.055053. Also, peak 47 was identified as myricetin 3-O-rhamnoside (myricitrin), observed only in MTL, with [M–H]– at m/z 463.117354. Kaempferol derivatives were widely detected. Peak 33, found in MTL and MTF, showed [M–H]– at m/z 461.1724 and a fragment at m/z 285.09616, indicating loss of a glucuronide moiety, tentatively identified as kaempferol 3-O-glucuronide54. Peak 34 was attributed to kaempferol 7-O-neohesperidoside54 with [M–H]– at m/z 593.1493 and a fragment at m/z 285.0437. Peak 38, seen in MTF and MVF, was identified as kaempferol 3-O-robinoside-7-O-rhamnoside, with [M + H]+ at m/z 741.2368 and fragments from rhamnose and robinose losses55. Peak 42, with [M–H]– at m/z 431.1905 and a loss of rhamnose to yield m/z 285.1485, was assigned as kaempferol 3-O-α-L-rhamnoside56. Peaks 44 to 46 indicated various kaempferol glycosides: peak 44 (kaempferol 3-O-rutinoside)57 with [M + H]+ at m/z 595.1741 and fragment at m/z 287.07844; peak 45 (kaempferol 3-O-(6-p-coumaroyl)-hexoside)57 with [M–H]– at m/z 593.1507 and fragment at m/z 285.0403; and peak 46 (kaempferol 3-O-hexoside)58 with [M + H]+ at m/z 449.1830 and fragment at m/z 287.1305. Peak 54 present in the four plants, was assigned as kaempferide (kaempferol 4’-O-methyl ether)59with [M–H]– at m/z 299.0562 and a product ion at m/z 284.0330. Syringetin derivatives were represented by peaks 48 and 49, both with [M–H]– at m/z 507.1148 and 507.1167, respectively, and aglycone ions at m/z 345.0618 and 344.0563 due to loss of hexoside moiety. These were identified as syringetin 3-O-galactoside and syringetin 3-O-hexoside, respectively60. Quercetin derivatives included peaks 35, 39, 40, 41, 43, 51, 52, 53, and 56. Peak 53 (quercetin aglycone) was present in MTL and MTF, showing [M–H]– at m/z 301.0736 and [M + H]+ at m/z 303.1436 with typical RDA fragments31. Peak 40 was identified as quercetin 3-O-α-L-rhamnoside (quercitrin)61 with [M–H]– at m/z 447.1960 and a fragment at m/z 301.1678. Peak 43, identified as quercetin 3-O-rutinoside (rutin)62showed [M–H]– at m/z 611.1714 and a fragment at m/z 303.0598. Peaks 51 and 52 were assigned to isoquercitrin and quercetin 4’-O-hexoside based on MS2 fragments at m/z 303.0920 and m/z 301.0728, respectively63. Peak 35, seen only in MTL, showed [M–H]– at m/z 433.1754 and a fragment at m/z 301.1076, identified as quercetin 3-O-xyloside64. Isorhamnetin derivatives were represented by peaks 37, 50, and 55. Peak 37 was identified as isorhamnetin 3-O-rutinoside with [M–H]– at m/z 623.1601 and fragment at m/z 315.1159. Peak 50, with [M–H]– at m/z 477.1062 and a fragment at m/z 315.0541, was assigned as isorhamnetin 3-O-hexoside65. Finally, peak 55, prominent in MTL, was identified as isorhamnetin aglycone with [M–H]– at m/z 315.0877 and [M + H]+ at m/z 317.0682, confirming it as 5,7,4’-trihydroxy-3’-methoxy flavonol65.

Anthocyanin

A total of seven anthocyanin-type flavonoids were identified, with only peaks 59 and 64 being common to all four extracts, while peaks 62, 63, and 65 were exclusive to MTF, peak 61 was found in both parts of Merav, and peak 60 was detected in the fruit of both plants. Peak 59 had an oxidative molecular ion at m/z 609.1468 [M-2 H]– and a key aglycone fragment at m/z 301.0354 [M-H-308]–, indicating the loss of a rutinoside moiety, along with other oxidative fragments (299.1257 and 300.0286) and C-ring cleavage fragments (151.0025, 163.06029, and 271.0573). It was tentatively identified as delphinidin 3-O-(6ꞌꞌ-O-α-rhamnopyranosyl-β-glucopyranoside)66. Peak 61, found mainly in MVL, was identified as delphinidin aglycone66 with an oxidative ion at m/z 301.0749 [M-2 H]–. Peaks 62, 63, and 65 were classified as malvidin glycosides based on their aglycone fragments: peak 62 (m/z 493.1328 [M]+, 491.1202 [M–2 H]–) showed a fragment at m/z 329.0817 [M–H–162]– due to galactose loss, identifying it as malvidin 3-O-galactoside; peak 65 (m/z 491.1162 [M–2 H]–) had a fragment at m/z 329.0668 [M–H–162]– indicating glucoside loss, identified as malvidin 3-O-glucoside; and peak 63 (m/z 655.1688 [M]+) displayed fragments at m/z 493.1399 [M–162]+ and 331.2114 [M + 324]+, leading to identification as malvidin 3,5-di-O-glucoside66. Peak 64, presented molecular ions at m/z 461.1078 [M–2 H]– and 463.1289 [M]+ and an aglycone fragment at m/z 299.8789 [M–H–162]–, corresponding to the loss of a hexose moiety, and was identified as peonidin 3-O-hexoside66.

Coumarins

Four coumarins were detected in all four extracts, as indicated in Table 3; two were detected at MTL, MVL and MTF, which were assigned to peaks 82 and 83, while peak 84 was detected in MTF only. The last was peak 85 which was detected in MVL, MTF and MVF. The characteristic fragmentation patterns of coumarins include the sequential loss of CO and/or CO2. Peak 82 was tentatively identified as scopoletin67 as it displayed a deprotonated molecular ion at m/z 191.0349, In its negative MS2 spectrum, the characteristic product ions were interpreted at m/z 176.0123 [M-H-CH3]–, and 148.1174 [M-H-CH3-CO]–. Peak 83 was assigned to daphnetin68 that showed a molecular ion peak at m/z 177.0566 [M-H]–. Its MS2 spectrum showed the aglycone ion at m/z 133.02689 [M–H– 44]– corresponding to the loss of CO2. Peak 84 displayed a deprotonated ion at m/z 174.9582. In its MS2 spectrum, the characteristic product ions were interpreted at m/z 156.9518 [M-H-OH]– and 130.5520 [M-H-CO2]– that was in complete agreement with the library database and reported data of 7-hydroxy-4-methyl-coumarin67. Moreover, peak 85 was assigned to be di-hydroxycoumarin hexoside, where it showed a deprotonated molecular ion peak at m/z 339.2768 [M-H]– and protonated ion m/z 341.1190 [M + H]+. Two distinctive product ions were visible in its negative MS2 spectra at m/z 177.1507 [M-H-162]- and 131.0757 [M-H-162-44]-, which corresponded to the loss of the hexoside moiety and (hexoside + CO2), respectively. Based on published data, this metabolite was tentatively identified as esculin42.

Phenolic acids

Eight phenolic acids were detected across all four extracts, corresponding to peaks 69–75, and were primarily characterized by common fragmentation patterns including dehydration (-H₂O, 18 amu) and decarboxylation (-CO₂, 44 amu). Peak 69 showed a molecular ion at m/z 353.1095 [M–H]⁻ and was identified as chlorogenic acid69. Peak 70 displayed m/z 385.0780 [M–H]⁻ with an aglycone fragment at m/z 223.0448 [M–H–162]⁻ indicating the loss of a hexose and confirming it as 1-O-β-D-glucopyranosyl sinapate70. Peak 71, found in MVL and MVF, showed m/z 147.0397 [M–H]⁻ and a fragment at m/z 103.0584 [M–H–44]⁻, and was identified as trans-cinnamate71. Peak 72 appeared only in MTF with m/z 165.0587 [M + H]+ and a major fragment at m/z 120.9609 from decarboxylation, indicating p-coumaric acid. Peak 73 had a protonated ion at m/z 225.0932 with MS2 ions at m/z 210.1461, 195.0495, and 151.0554 corresponding to methyl losses and CO₂, confirming sinapic acid identity72. Peak 74, dominant in MVL showed m/z 179.0305 [M–H]⁻ with a fragment at m/z 135.0468 [M–H–44]⁻, aligning with caffeic acid73. Finally, peak 75 appeared only in MTL with m/z 359.1731 [M–H]⁻ and diagnostic fragments at m/z 197.1208 and 179.0981, along with further dehydrated and decarboxylated fragments at m/z 161.0424 and 135.0345, confirming it as rosmarinic acid74.

Body weight evaluation

Body weight was tracked biweekly and displayed in Table 4. The Letrozole + HFD-treated mice experienced a notable weight gain of 12.76% compared to the control group. In contrast, the body weight of HFD-treated mice given Murcott and Merav fruit and leaf extracts (500 mg each) and metformin (300 mg) individually decreased by 7.89%, 14.51%, 10.53%, 24.41%, and 27.63%, respectively, compared to PCOS-induced mice (p < 0.05).

Although specific toxicity assessments were not part of the current study, no adverse behavioral changes or mortality were observed during the experimental period. Future investigations will incorporate detailed acute and sub-chronic toxicity studies to ensure safety and determine the therapeutic index.

Effect of Murcott and Merav on plasma lipid profile in PCOS-induced mice

In Letrozole-treated mice on a high-fat diet, plasma total cholesterol (TC) and triglyceride (TG) levels rose significantly by 51.28% and 91.44%, respectively, while plasma HDL-C levels dropped by 58.70% (Table 5). Compared to Letrozole + HFD-treated mice, plasma TC and TG levels in PCOS-induced mice treated with MTF, MTL, MVF and MVL extracts (500 mg) were significantly lower (p < 0.05) by (20.35 and 12.06%), (26.50 and 26.21%), (23.61 and 19.71%), and (30.26 and 32.44%), respectively. Additionally, HDL-C levels were significantly higher by 86.94, 126.67, 106.42 and 170.67% (p < 0.05). Treatment with metformin (300 mg/kg.b.w) also significantly reduced TG and TC levels by 33.15% and 36.51%, respectively, and increased HDL-C levels by 178.21% (p < 0.05) compared to PCO-induced mice.

Effect of Murcott and Merav on ovarian oxidative stress markers in PCOS-induced mice

Table 6 illustrates the levels of ovarian GSH, SOD, CAT, and MDA in normal and PCOS-induced mice treated with MTF, MTL, MVF and MVL extracts. Compared to normal mice (Group I), there was a significant decrease (p < 0.05) in ovarian GSH, SOD, and CAT levels by 64.19%, 160.89%, and 52.60%, respectively, and a significant increase in ovarian MDA by 54.28% after 8 weeks of Letrozole + HFD administration. Mice receiving MTF (500 mg/kg.b.w.) showed 59.50%, 45.79%, and 37.78% higher ovarian GSH, SOD, and CAT levels, respectively, and a significant decrease in ovarian MDA by 23.18% compared to PCOS-induced mice (p < 0.05). Treatment with MTL (500 mg/kg.b.w.) led to a significant increase in GSH, SOD, and CAT levels by 103.08%, 78.41%, and 57.01%, respectively, and a 29.21% reduction in MDA levels in comparison to the PCOS-induced mice (p < 0.05). Mice receiving MVF (500 mg) showed significant increases in GSH, SOD, and CAT levels by 69.28%, 58.32%, and 47.51%, respectively, and a decrease in MDA levels by 26.83% relative to PCOS-induced mice after 8 weeks (p < 0.05). Mice receiving MVL (500 mg) showed significant increases in GSH, SOD, and CAT levels by 139.95%, 211.88%, and 83.67%, respectively, and a decrease in MDA levels by 33.20% relative to PCOS-induced mice after 8 weeks (p < 0.05). Additionally, mice receiving Metformin (300 mg) showed significant increases in GSH, SOD, and CAT levels by 75.59%, 47.52%, and 28.05%, respectively, and a decrease in MDA levels by 18.03% relative to PCOS-induced mice after 8 weeks (p < 0.05).

Effect of Murcott and Merav on plasma FSH, LH and testosterone levels in PCOS-induced mice

Table 7 shows significant changes in ovarian hormone levels in normal and treated mice. In PCOS-induced mice, ovarian FSH decreased by 67%, while testosterone and LH levels increased by 1204.77% and 181.66%, respectively. Treatment with MTF significantly increased ovarian FSH by 93.79% and reduced testosterone and LH levels by 77.46% and 41.08%, respectively (p < 0.05). MTL treatment increased ovarian FSH by 122.98% and reduced testosterone and LH levels by 90.32% and 54.41%, respectively (p < 0.05). MVF treatment increased ovarian FSH by 101.63% and reduced testosterone and LH levels by 86.09% and 45.11%, respectively (p < 0.05). MVL treatment increased ovarian FSH by 175.41% and reduced testosterone and LH levels by 92.51% and 68%, respectively (p < 0.05). Metformin treatment increased ovarian FSH by 117.02% and reduced testosterone and LH levels by 76.27% and 59.69%, respectively (p < 0.05).

Effect of Murcott and Merav on plasma COX-2 and ovarian NF-kβ levels in PCOS-induced mice

In PCO-induced animals, ovarian COX-2 and NF-kβ levels were markedly increased by 437.15% and 178.11%, respectively, compared to control mice (p < 0.05) (Table 8). MTF (500 mg/kg.b.w.) treatment significantly decreased these levels by 53.25% and 36.74%, respectively, compared to the PCO-induced group (p < 0.05). MTL treatment resulted in even larger reductions in ovarian COX-2 and NF-kβ levels, showing decreases of 66.13% and 56.16%, respectively, compared to the PCOS group. MVF treatment also significantly reduced ovarian COX-2 and NF-kβ levels by 75.82% and 43.04%, respectively, compared to the PCOS-induced mice. MVL supplementation brought about the most notable reductions, with ovarian COX-2 and NF-kβ levels declining by 81.50% and 69.02%, respectively, compared to the PCOS group (p < 0.05). Lastly, Metformin treatment significantly lowered ovarian COX-2 and NF-kβ levels by 44.80% and 30.97%, respectively, compared to the PCOS-induced group (p < 0.05).

Effect of Murcott and Merav on ovarian miR-33b-5P and miR-145 gene expression in PCOS-induced mice

Figure 3 shows the expression levels of ovarian miR-33b-5P and miR-145 genes in normal and PCOS-induced mice. Compared to normal mice, miR-33b-5P was significantly higher by 451.41%, while miR-145 was downregulated by 54.36% in Letrozole + HFD-administered mice. In comparison to PCOS-induced mice, MTF (500 mg/kg b.w.) treatment significantly reduced ovarian miR-33b-5P expression by 38.42% and significantly increased miR-145 gene expression by 55.32% (p < 0.05). Similarly, MTL (500 mg/kg b.w.) treatment resulted in a significant decrease in ovarian miR-33b-5P by 39.66% and a significant increase in miR-145 gene expression by 63.84% (p < 0.05). MVF (500 mg/kg b.w.) administration resulted in a notable reduction in ovarian miR-33b-5P by 53.05% and a significant upregulation of miR-145 gene expression by 72.34% (p < 0.05). MVL treatment significantly decreased ovarian miR-33b-5P by 66.27% and significantly upregulated miR-145 gene expression by 85.11% (p < 0.05). Furthermore, Metformin treatment resulted in substantial reductions, with ovarian miR-33b-5P decreasing by 46.10% and miR-145 gene expression increasing by 45.80%, compared to PCOS-induced mice (p < 0.05). All the previous data were shown in Fig. 3.

Impact of Murcott and Merav fruits and leaves on ovarian nuclear miR-33b-5P and miR-145 gene expression in mice. The data are presented as the mean ± standard deviation based on the number of observations for each treatment. F: F for One way ANOVA test, pairwise comparison between each groups was done using Post Hoc Test (Tukey). *: Statistically significant at p ≤ 0.05. a: Significant with Group I, b: Significant with Group II, c: Significant with Group III, d: Significant with Group IV, e: Significant with Group V, f: Significant with Group VI. Murcott Fruit (MTF), Murcott Leaves (MTL), Merav Fruit (MVF), and Merav Leaves (MVL).

Histological examination of mice ovarian tissues of targeted groups compared to control group

In the control group, ovarian tissues showed normal histology, with a cortex containing primordial follicles (single layer of flattened cells), primary follicles (one or multiple layers of cuboidal granulosa cells), secondary follicles (with multilayered granulosa cells, oocyte, and antral cavities), and a healthy stroma. The outer cortex also displayed corpora lutea with foamy acidophilic cytoplasm and pale nuclei, along with atretic follicles and mature Graafian follicles characterized by organized granulosa layers, liquid folliculi, corona radiata, zona pellucida, and a fibrous theca externa. In contrast, PCOS-induced mice exhibited severe ovarian damage, including degenerated follicles with black pyknotic nuclei, disorganized and vacuolated granulosa cells, a significant reduction in primary follicles, very few corpora lutea, absence of primary and secondary follicles, and extensive stromal cell infiltration. Treatment with MTF (500 mg/kg) successfully restored normal ovarian architecture, with various developing follicles and small clusters of large lutein cells in the corpus luteum. MTL-treated mice showed multilaminar primary and secondary follicles, normal stroma, and some follicles with darkly stained nuclei. MVF treatment effectively reestablished typical ovarian structure, featuring mature Graafian follicles, numerous primary follicles, few degenerated follicles, and large corpora lutea with mildly eosinophilic cytoplasm. Similarly, MVL treatment resulted in ovarian tissue closely resembling the control group, with a defined cortex and medulla containing primordial, primary, secondary, and few atretic follicles, alongside well-formed corpora lutea and a healthy stroma. Finally, metformin treatment at 300 mg/kg also promoted recovery, as shown by the presence of multiple developing follicles, corpora lutea, and normal stromal architecture, despite occasional strongly stained nuclei. Overall, these treatments, especially at higher doses, effectively reversed PCOS-induced ovarian damage and restored normal histological features. As illustrated in Fig. 4.

Histological analysis of ovarian tissue sections from mice, stained with hematoxylin and eosin (H&E; 200x), was performed for various groups and compared to the control group. (a): Group I: Normal control; (b): Group II: PCOS group, Was administrative Letrozole (90 µg/kg) and fed HFD; (c): Group III: PCO induced mice treated with MTF(500 mg/kg); (d): Group IV: PCO induced mice treated with MTL(500 mg/kg); (e): Group V: PCO induced mice treated with MVF(500 mg/kg); (f): Group VI: PCO induced mice treated with MVL(500 mg/kg); and (g): Group VII: PCO induced mice treated with Metformin (300 mg/kg b.w). Primary follicles (PF), secondary follicles (SF), corpora lutea (CL). MTL follicles displayed nuclei that were strongly stained (bifid arrow), primordial follicles (dotted arrow), normal stroma (S), atretic follicles (AF) and degenerated follicles (DF).

Conclusion

This study highlights the therapeutic potential of Murcott and Merav (Citrus reticulata) fruit and leaf extracts in managing polycystic ovary syndrome (PCOS) through their ability to restore hormonal balance, reduce oxidative stress, improve lipid profiles, regulate inflammatory markers, and correct ovarian tissue morphology. In the PCOS-induced model, letrozole combined with a high-fat diet resulted in significant metabolic and histological alterations, consistent with typical PCOS pathology, including increased body weight, dyslipidemia, elevated testosterone and LH levels, suppressed FSH, oxidative stress, and inflammation, alongside ovarian structural damage with follicular degeneration and stromal infiltration.

Treatment with Murcott and Merav extracts (MTF, MTL, MVF, MVL) at 500 mg/kg markedly reversed these pathological features. Particularly, MVL demonstrated the most potent therapeutic effects, significantly improving body weight, reducing cholesterol and triglyceride levels, increasing HDL-C, enhancing antioxidant defense (GSH, SOD, CAT), and reducing oxidative marker MDA. MVL also achieved the most substantial reduction in inflammatory mediators COX-2 and NF-kβ. On the molecular level, MVL upregulated miR-145 expression and downregulated miR-33b-5P more effectively than the other treatments, highlighting its role in modulating oxidative stress and inflammation at the genetic level.

The observed modulation of LH, FSH, and testosterone levels reflects a restoration of the hypothalamic–pituitary–ovarian (HPO) axis, which is typically disrupted in PCOS. Elevated LH and testosterone, along with reduced FSH, are hallmarks of PCOS and contribute to anovulation and follicular arrest. The extracts’ ability to normalize these hormones suggests a rebalancing of gonadotropin secretion and androgen synthesis. Furthermore, the significant downregulation of COX-2 and NF-kβ indicates suppression of chronic inflammation, a key driver of ovarian dysfunction in PCOS. The upregulation of miR-145 and downregulation of miR-33b-5P further support this anti-inflammatory and antioxidative effect, as these miRNAs are known to regulate genes involved in lipid metabolism, oxidative stress, and inflammatory signaling. miR-145, in particular, has been shown to promote granulosa cell function and follicular development, while miR-33b-5P is associated with lipid dysregulation and inflammation. Thus, the extracts may exert their therapeutic effects by targeting both endocrine and molecular pathways central to PCOS pathogenesis.

Histologically, treatment with MTF, MTL, MVF, and MVL restored normal ovarian architecture, with the reappearance of various stages of developing follicles and corpora lutea, reduction of atretic and degenerated follicles, and normalization of the stromal tissue. MVL treatment achieved the most complete histological recovery, closely resembling the normal control group. Compared to standard treatment with metformin (300 mg/kg), the citrus extracts, particularly MVL, showed comparable or superior effects across most parameters, suggesting that natural bioactive compounds, especially methylated flavonoids such as methylated kaempferol present in Merav leaves, might offer effective and safer alternatives for PCOS management. These findings support previous research showing that flavonoids and other phenolic compounds have powerful antioxidant, anti-inflammatory, and hormone-regulating properties, making them potential therapeutic options for PCOS. Thus, the Murcott and Merav varieties, particularly the Merav leaf extract, represent promising natural therapeutic agents for mitigating PCOS symptoms, improving reproductive health, and addressing associated metabolic and inflammatory disturbances.

Study limitations

A limitation of the current study is the use of a single dose (500 mg/kg b.w.) for evaluating the therapeutic effects of the extracts. While this dose was selected based on literature precedent and demonstrated significant efficacy, future studies should include multiple dose levels to establish a clearer dose-response relationship. This would enhance the pharmacological relevance of the findings and support more precise therapeutic recommendations. On the other hand, the combination of HFD and letrozole has been widely used to induce both metabolic and reproductive features of PCOS, including hyperandrogenism and ovarian dysfunction. We acknowledge that insulin resistance was not evaluated through markers such as fasting insulin, glucose tolerance, or HOMA-IR. Future studies are warranted to include these parameters to better characterize the metabolic phenotype of the model and to explore whether the tested extracts exert beneficial effects on insulin sensitivity.

Data availability

All data analyzed during this study are presented and included in this article and supplementary file.

References

Helmy, W. et al. El-hakeem Voice analysis in women with polycystic ovary syndrome. Egypt. J. Otolaryngol. 40, 117 (2024).

Lotfy, E. et al. An educational program for females regarding polycystic ovarian syndrome based on the health belief model. Int. J. Nov Res. Healthc. Nurs. 11, 213–226 (2024).

Fauser, B. C. J. M. Revised 2003 consensus on diagnostic criteria and long-term health risks related to polycystic ovary syndrome. Fertil. Steril. 81, 19–25 (2004).

Kyrou, I., Weickert, M. O. & Randeva, H. S. Diagnosis and management of polycystic ovary syndrome (PCOS). Endocrinol. Diabetes Case Stud. Quest Comment. 99–113. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-1-4471-2789-5_13/TABLES/2 (2015).

Manouchehri, A. et al. Polycystic ovaries and herbal remedies: A systematic review. JBRA Assist. Reprod. 27, 85 (2023).

Malik, S. et al. Alternative treatment of polycystic ovary syndrome: pre-clinical and clinical basis for using plant-based drugs. Front. Endocrinol. (Lausanne). 14, 1294406 (2023).

Sharma, A., Bansal, K. & Bajpai, M. The role of different medicinal herbs in treatment of polycystic ovarysyndrome: A review. Nat. Prod. J. 14, 68–76 (2023).

Lakshmi, J. N. et al. Herbs as a Source for the Treatment of Polycystic Ovarian Syndrome: A Systematic Review. BioTech 12, 4 (2023).

Elnagar, I., Fahmy, M. A., Abd-Alrazik, A. M. & Sultan, M. Z. Effect of some postharvest treatments with edible coating materials on storability and quality of Murcott Tangor fruits during cold storage. Al-Azhar J. Agric. Res. 46, 16–27 (2021).

Yang, L. et al. Fruit characteristics and seed anatomy of ‘majia’ pomelo pollinated with cobalt-60 gamma-ray-irradiated pollen. Sci. Hortic. (Amsterdam). 267, 109335 (2020).

Bentahar, A., Bouaziz, A., Djidel, S. & Khennouf, S. Phenolic content and antioxidant activity of ethanolic extracts from citrus sinensis L. and citrus reticulata L. fruits. J. Drug Deliv Ther. 10, 308–313 (2020).

Yuan, J., Li, Z., Yu, Y., Wang, X. & Zhao, Y. Natural compounds in the management of polycystic ovary syndrome: a comprehensive review of hormonal regulation and therapeutic potential. Front. Nutr. 12, 1520695 (2025).

Bergsten, T. M., Li, K., Lantvit, D. D., Murphy, B. T. & Burdette, J. E. Kaempferol, a phytoprogestin, induces a subset of Progesterone-Regulated genes in the uterus. Nutrients 15, 1407 (2023).

Zhang, J. et al. Efficacy of flavonoids on animal models of polycystic ovary syndrome: A systematic review and Meta-Analysis. Nutrients 14, 4128 (2022).

Ma, C., Xiang, Q., Song, G. & Wang, X. Quercetin and polycystic ovary syndrome. Front. Pharmacol. 13, 1006678 (2022).

Jiang, Y. et al. Flavonoid supplementation is beneficial for polycystic ovary syndrome: A systematic review and Meta-analysis. Nutr Rev 83, e829–e837 (2024).

Azmir, J. et al. Techniques for extraction of bioactive compounds from plant materials: A review. J. Food Eng. 117, 426–436 (2013).

El El-Haddad Alaadin, G. H. A., Attia Yasmin, E., Fahim Sally, M. & Zafer Mai, A. Vitro cytotoxic activity and phytochemical characterization (UPLC/T-TOF-MS/MS) of the watermelon (Citrullus lanatus) rind extract. Molecules 27, 1–19 (2022).

Tsugawa, H. et al. MS-DIAL: data-independent MS/MS Deconvolution for comprehensive metabolome analysis. Nat. Methods. 12, 523–526 (2015).

Mahrous, F. S., Mohammed, H. S., Sabour, R., Ismail, L. D. & LC-ESI-QTOF-MS / MS of holoptelea integrifolia (Roxb.) planch. Leaves and in Silico study of phenolic compounds ’ antiviral activity against the HSV1 virus. Azhar Int. J. Pharm. Med. Sci. 1, 91–101 (2021).

Shahid, R. et al. Diet and lifestyle modifications for effective management of polycystic ovarian syndrome (PCOS). J Food Biochem 46, 14117 (2022).

Kafali, H., Iriadam, M., Ozardali, I. & Demir, N. Letrozole-induced polycystic ovaries in the rat: a new model for cystic ovarian disease. Arch. Med. Res. 35, 103–108 (2004).

Di Pietro, M. et al. Metformin regulates ovarian angiogenesis and follicular development in a female polycystic ovary syndrome rat model. Endocrinology 156, 1453–1463 (2015).

Troisi, R. J., Cowie, C. C. & Harris, M. I. Diurnal variation in fasting plasma glucose: implications for diagnosis of diabetes in patients examined in the afternoon. JAMA 284, 3157–3159 (2000).

Owen, J. B. Allan butterfiel, D. Measurement of oxidized/reduced glutathione ratio. Methods Mol. Biol. 648, 269–277 (2010).

Bartosz, G. Use of spectroscopic probes for detection of reactive oxygen species. Clin. Chim. Acta. 368, 53–76 (2006).

Maiorino, F. M. et al. Diversity of glutathione peroxidases. Methods Enzymol. 252, 38–53 (1995).

Boshra, S. A. & Astaxanthin Attenuates Adiponectin Calprotectin, miRNA222 and miRNA378 in obesity induced by High-Fat diet in rats. Curr. Pharm. Biotechnol. 23, 609–618 (2021).

Bancroft, G. D. & Steven, A. No TitleTheory and Practice of Histological Technique, 4th edition. Churchill Livingstone, New York 99–112 (1983).

McHugh, M. L. Multiple comparison analysis testing in ANOVA. Biochem. Med. 21, 203–209 (2011).

He, Y. J. et al. Comparative investigation of phytochemicals among ten citrus herbs by ultra high performance liquid chromatography coupled with electrospray ionization quadrupole time-of-flight mass spectrometry and evaluation of their antioxidant properties. J. Sep. Sci. 43, 3349–3358 (2020).

Taleghani, A., Eghbali, S., Moghimi, R. & Mokaber-Esfahani, M. Crataegus Pentagyna willd. Fruits, leaves and roots: phytochemicals, antioxidant and antimicrobial potentials. BMC Complement. Med. Ther. 24, 1–20 (2024).

Lou, S., Lai, Y., Huang, J., Ho, C. & Ferng, L. A. Drying effect on flavonoid composition and antioxidant activity of immature Kumquat. Food Chem. 171, 356–363 (2015).

Jiao, Q. et al. Metabolism study of Hesperetin and hesperidin in rats by UHPLC-LTQ-Orbitrap MSn. Xenobiotica 50, 1311–1322 (2020).

Phucharoenrak, P., Muangnoi, C. & Trachootham, D. A. Green extraction method to achieve the highest yield of. Molecules 27, 1–12 (2022).

Yang, Y. et al. Quantitative and qualitative analysis of flavonoids and phenolic acids in snow chrysanthemum (Coreopsis tinctoria Nutt.) by HPLC-DAD and UPLC-ESI-QTOF-MS. Molecules 21, (2016).

Zhang, F. X. et al. Dissection of the potential Pharmacological function of neohesperidin dihydrochalcone-a food additive-by: in vivo substances profiling and network Pharmacology. Food Funct. 12, 4325–4336 (2021).

Du, J. et al. Lc-esi-qtof-ms/ms profiling and antioxidant activity of phenolics from custard Apple fruit and by-products. Separations 8, 1–26 (2021).

El-zawahry, H. M. E., Shakour, Z. T. A., El-shafei, A. A. & El-tantawy, M. E. Larvicidal and cytotoxic activity of Cordyline terminalis Kunth and its metabolites profiling via UPLC-MS / MS. Azhar Int. J. Pharm. Med. Sci. 5, 141–151 (2025).

Śliwka-Kaszyńska, M., Anusiewicz, I. & Skurski, P. The mechanism of a Retro-Diels–Alder fragmentation of luteolin: theoretical studies supported by electrospray ionization tandem mass spectrometry results. Mol. 2022. 27, 1032 (2022).

Shao, S. Y., Ting, Y., Wang, J., Sun, J. & Guo, X. F. Characterization and identification of the major flavonoids in phyllostachys Edulis leaf extract by UPLC-QTOF-MS/MS. Acta Chromatogr. 32, 228–237 (2020).

Abdl Aziz, F., Temraz, A. & Hassan, M. Metabolites profiling by LC-ESI-MS/MS technique And in-vitro antioxidant activity of bauhinia Madagascariensis desv. And bauhinia purpurea L. aerial parts cultivated in egypt: a comparative study. Azhar Int. J. Pharm. Med. Sci. 4, 169–188 (2024).

Pereira, C. A. M., Yariwake, J. H. & McCullagh, M. Distinction of the C-glycosylfavone isomer pairs orientin/isoorientin and vitexin/isovitexin using HPLC-MS exact mass measurement and in-source CID. Phytochem Anal. 16, 295–301 (2005).

Negm, W. A. et al. Wound-Healing potential of Rhoifolin-Rich fraction isolated from Sanguisorba officinalis roots supported by enhancing Re-Epithelization, angiogenesis, Anti-Inflammatory, and antimicrobial effects. Pharmaceuticals 15, 178 (2022).

Iwashina, T., Mizuno, T. & Devkota, H. P. Further identification of flavonoids deposited in the National museum of nature and science in Japan-Flavonoids isolated from cirsium taxa and carduus nutans (Asteraceae). Bull. Natl. Mus. Nat. Sci. Ser. B. 46, 195–214 (2020).

Sung, B., Chung, H. Y. & Kim, N. D. Role of apigenin in cancer prevention via the induction of apoptosis and autophagy. J. Cancer Prev. 21, 216 (2016).

Yin, J. et al. A systematic study of the metabolites of dietary Acacetin in vivo and in vitro based on UHPLC-Q-TOF-MS/MS analysis. J. Agric. Food Chem. 67, 5530–5543 (2019).

Zhao, W. et al. Rapid screening and identification of Daidzein metabolites in rats based on UHPLC-LTQ-Orbitrap mass spectrometry coupled with Data-Mining technologies. Mol. J. Synth. Chem. Nat. Prod. Chem. 23, 151 (2018).

Liang, Y. et al. A comprehensive screening and identification of genistin metabolites in rats based on multiple metabolite templates combined with UHPLC-HRMS analysis. Mol. J. Synth. Chem. Nat. Prod. Chem. 23, 1862 (2018).

Xu, X., Li, X. & Liang, X. Application of ultra-performance liquid chromatography coupled with quadrupole time-of-flight mass spectrometry in identification of three isoflavone glycosides and their corresponding metabolites. Rapid Commun. Mass. Spectrom. 32, 262–268 (2018).

-Aal, A. E., Mohammed, F., Ibrahim, H., Ismail, L. & M. & Chemical profiling of polyphenols in thunbergia Alata and in Silico virtual screening of their antiviral activities against COVID-19. Azhar Int. J. Pharm. Med. Sci. 1, 94–100 (2021).

Stenger Moura, F. C. et al. Taxifolin stability: in Silico prediction and in vitro degradation with HPLC-UV/UPLC–ESI-MS monitoring. J. Pharm. Anal. 11, 232–240 (2021).

Pereira, P., Cebola, M. J., Oliveira, M. C. & Bernardo Gil, M. G. Antioxidant capacity and identification of bioactive compounds of Myrtus communis L. extract obtained by ultrasound-assisted extraction. J. Food Sci. Technol. 54, 4362 (2017).

Hwang, I. W. & Chung, S. K. Isolation and identification of myricitrin, an antioxidant flavonoid, from Daebong persimmon Peel. Prev. Nutr. Food Sci. 23, 341 (2018).

Silva, L. M. P. et al. Isolation and identification of the five novel flavonoids from Genipa Americana leaves. Mol. 2018. 23, 2521 (2018).

Lu, Y. et al. Systematic characterization of flavonoids from Siraitia grosvenorii leaf extract using an integrated strategy of high-speed counter-current chromatography combined with ultra high performance liquid chromatography and electrospray ionization quadrupole Ti. J. Sep. Sci. 43, 852–864 (2020).

Abd Elkarim, A. S. & Taie, H. A. A. Characterization of flavonoids from combretum indicum L. Growing in Egypt as antioxidant and antitumor agents. Egypt. J. Chem. 66, 2291–2305 (2023).

Beszterda, M. & Frański, R. Elucidation of glycosylation sites of Kaempferol di-O-glycosides from methanolic extract of the leaves of Prunus domestica subsp. Syriaca. Rapid Commun. Mass. Spectrom. 35, e9100 (2021).

Zhou, Y. et al. Qualitative analysis and componential differences of chemical constituents in lysimachiae herba from different habitats (Sichuan Basin) by UFLC-Triple TOF-MS/MS. Mol. 2022. 27, 4600 (2022).

De Rosso, M. et al. Identification of new flavonols in hybrid grapes by combined liquid chromatography-mass spectrometry approaches. Food Chem. 163, 244–251 (2014).

Da Costa, J. D. C. et al. Development and validation of a sensitive UFLC-MS/MS method for quantification of Quercitrin in plasma: application to a tissue distribution study. ACS Omega. 4, 3527–3533 (2019).

Choi, S. S., Park, H. R. & Lee, K. A. A comparative study of Rutin and Rutin glycoside: antioxidant activity, Anti-Inflammatory effect, effect on platelet aggregation and blood coagulation. Antioxid. 2021. 10, Page 1696 (10), 1696 (2021).

Elkhedir, A. E., Abker, A. M., Elsadig, M., Mohammed, J. K. & Xu, X. Identification, structure elucidation, and isomer differentiation of phenolic compounds of Chinese pepper cultivars by UPLC-ESI-Q-TOF-MS and their antioxidant activity. J. Mass. Spectrom. 59, e5033 (2024).

Osztie, R. et al. Comprehensive characterization of phytochemical composition, membrane permeability, and antiproliferative activity of juglans Nigra polyphenols. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 25, 6930 (2024).

Wang, H. et al. Structures, Sources, Identification/Quantification Methods, Health Benefits, Bioaccessibility, and Products of Isorhamnetin Glycosides as Phytonutrients. Nutr. 2023, Vol. 15, Page 1947 15, (2023). (1947).

Yuzuak, S., Ballington, J., Li, G. & Xie, D. Y. High-Performance liquid Chromatography–Quadrupole Time-of-Flight tandem mass Spectrometry-Based profiling reveals anthocyanin profile alterations in berries of hybrid muscadine variety FLH 13 – 11 in two continuous cropping seasons. Agronomy 14, 442 (2024).

Zeng, Y. et al. Validated LC-MS/MS method for the determination of Scopoletin in rat plasma and its application to Pharmacokinetic studies. Molecules 20, 18988 (2015).

Wang, Z. et al. Determination of Daphnetin and its 8-O-Methylated metabolite in rat plasma by UFLC-MS/MS: application to a Pharmacokinetic study. Chromatographia 85, 333–341 (2022).

Nemzer, B., Abshiru, N. & Al-Taher, F. Identification of phytochemical compounds in coffea Arabica whole coffee cherries and their extracts by LC-MS/MS. J. Agric. Food Chem. 69, 3430–3438 (2021).

Engels, C. et al. Characterization of phenolic compounds in Jocote (Spondias purpurea L.) peels by ultra high-performance liquid chromatography/electrospray ionization mass spectrometry. Food Res. Int. 46, 557–562 (2012).

Jaiswal, R., Sovdat, T., Vivan, F. & Kuhnert, N. Profiling and characterization by LC-MSn of the chlorogenic acids and Hydroxycinnamoylshikimate esters in maté (Ilex paraguariensis). J. Agric. Food Chem. 58, 5471–5484 (2010).

Karlsson, O. Degree project in chemical engineering and technology, first level stockholm, Sweden 2020 ferulic Acid-A valuable natural compound for sustainable materials Oskar Karlsson. KTH Eng. Sci. Chem. Biotechnol. Heal 1, 233–290 (2020).

Clifford, M. N., Wu, W., Kirkpatrick, J. & Kuhnert, N. Profiling the chlorogenic acids and other caffeic acid derivatives of herbal chrysanthemum by LC – MSn. J. Agric. Food Chem. 55, 929–936 (2007).

Sik, B., Kapcsándi, V., Székelyhidi, R., Hanczné, E. L. & Ajtony, Z. Recent advances in the analysis of Rosmarinic acid from herbs in the lamiaceae family. Nat Prod. Commun 14, 1–10 (2019).

Acknowledgements

The authors are grateful to Prof. Dr. Wafaa Amer, Professor of Taxonomy, Faculty of Science, Cairo University, Cairo, Egypt, for her contribution to identifying the two cultivars of C. reticulata Blanco mandarin.

Funding

Open access funding provided by The Science, Technology & Innovation Funding Authority (STDF) in cooperation with The Egyptian Knowledge Bank (EKB).

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

Shaimaa A. El Zanaty: done the practical work, analysis results, writing manuscriptSalwa A. Abu El Wafa: revise results, revise manuscriptMohammed A Hussein: biological design, revise manuscriptHeba A. El Gizawy: conceptualization, correlating results, revise manuscriptAbeer Temraz: conceptualization, correlating results, revise manuscriptAll authors reviewed the manuscript and agreed it.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Ethics approval

These Animal studies were performed in accordance with ARRIVE guidelines with ethical approval granted by the Research Ethics Committee of the Faculty of Pharmacy for Girls, Al-Azhar University, Egypt (Ethics Approval No. 468).

Additional information

Publisher’s note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Supplementary Information

Below is the link to the electronic supplementary material.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

El Zanaty, S.A., El Wafa, S.A.A., Hussein, M.A. et al. Metabolic identification of bioactive compounds of Citrus reticulata cultivars extracts for a novel approach to polycystic ovary syndrome. Sci Rep 15, 32454 (2025). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-18116-5

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-18116-5