Abstract

This study aimed to investigate the association between stress hyperglycemia ratio (SHR) and the risk of acute respiratory distress syndrome (ARDS) in patients with sepsis. Data were extracted from the Medical Information Mart for Intensive Care - IV database in this retrospective cohort study. Participants were stratified into four groups based on the interquartile range of SHR. The primary outcome measure was the incidence of in-hospital ARDS. Multivariate Cox proportional-hazards regression and restricted cubic splines models were employed to evaluate the correlation between the SHR index and ARDS risk in patients with sepsis. Subgroup analysis and K-M survival curve analysis were also conducted. A total of 1,946 patients (59% male) were included in the study. The incidence of ARDS and in-hospital mortality was 34% and 13%, respectively. Multivariate Cox regression analysis revealed that the SHR index was independently associated with an increased risk of in-hospital ARDS and mortality. The RCS model indicated an approximately linear increase in the risk of both ARDS and in-hospital mortality with a rising SHR index. Subgroup analysis demonstrated consistent results. In conclusion, elevated SHR was significantly associated with a higher risk of ARDS and in-hospital all-cause mortality in sepsis patients.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Sepsis is widely recognized as a severe infectious disease, with the lungs commonly serving a primary target organ. Its key pathological features encompass diffuse alveolar damage, interstitial pulmonary edema, extensive inflammatory cell infiltration, and hypoxemia. These factors contribute to hypoxia and tissue necrosis in the lungs, specifically manifesting as acute lung injury (ALI), or, in more severe cases, acute respiratory distress syndrome (ARDS)1. Due to its high mortality and poor prognosis, ARDS remains one of the most life-threatening conditions encountered in the intensive care unit (ICU). Early prediction of ARDS is crucial for improving the prognosis of patients.

Currently, numerous studies, both domestic and international, focus on the early prediction of ARDS. As our understanding of ARDS pathogenesis continues to evolve, current studies increasingly target the prediction of ARDS using various indicators2,3,4. The pathogenesis of ARDS is complex and multifaceted, involving inflammatory response, alveolar-capillary damage, cytokine release, and other links. Several studies5,6 have unearthed that glucose metabolism disorders, especially hyperglycemia, may exacerbate the condition of ARDS patients. Hyperglycemic states can amplify inflammatory response, thereby accelerating ARDS progression. In addition, hyperglycemic states may impair vascular endothelial cell function, disrupt pulmonary microcirculation, and further aggravate the lung injury. Notably, glucose metabolism is often dysregulated in sepsis patients with ARDS. Given that ARDS patients are often in a state of stress, these alterations may elevate glucocorticoid levels in patients, thereby affecting glucose metabolism and inducing hyperglycemia. This stress-induced hyperglycaemia is reflected by an elevated stress hyperglycemia ratio (SHR)7.

SHR has been reported to be strongly correlated with adverse clinical outcomes in critically ill patients, including persistent organ failure in acute pancreatitis8poor prognosis in patients with pulmonary hypertension9ICU death, and one-year all-cause mortality10. A recent study11 has unveiled that SHR is a superior predictor of mortality and adverse outcomes in COVID-19 patients compared to admission blood glucose. In addition, the findings of Yan et al.12 have revealed a close association between elevated SHR and increased mortality in critically ill patients with sepsis, suggesting that a high SHR is a strong predictor of adverse clinical events. These findings underscore the potential of SHR as a predictor of adverse outcomes in sepsis patients.

However, the association between SHR and the risk of ARDS in sepsis patients remains unclear. Therefore, the objective of this study is to conduct a retrospective cohort study using the Medical Information Mart for Intensive Care-IV (MIMIC-IV) database to investigate the potential relationship between SHR and the risk of ARDS in sepsis patients, thus identifying a novel indicator for early ARDS prediction in sepsis patients.

Materials and methods

Study population

A retrospective cohort study design was adopted in the study. The original data were sourced from the MIMIC-IV database (version 2.2). This is a comprehensive, single-center database maintained by the Laboratory for Computational Physiology at the Massachusetts Institute of Technology. Author Xianwei Ji was granted access to the data set (ID: 62696052) and was responsible for data extraction. Patients diagnosed with sepsis were included based on the Sepsis-3.0 definition, which requires the presence of infection along with a Sequential Organ Failure Assessment (SOFA) score of ≥ 2 13. To identify eligible patients, a previously published approach14 was employed. This approach involved screening the MIMIC-IV database to identify eligible sepsis patients. Inclusion criteria were as follows: (a) Admission to the ICU; (b) A diagnosis of sepsis according to Sepsis 3.0. Exclusion criteria were as follows: (a) ARDS occurring before sepsis diagnosis; (b) Unavailable glucose data; (c) Unavailable glycosylated hemoglobin data (Supplementary Fig. 1). For patients with multiple admissions, only data from the first admission were included.

Variable

In this study, Structured Query Language (SQL) and the PostgreSQL database system (version 14.2) were utilized to efficiently extract baseline characteristic data of patients. These characteristics encompassed patient demographics (status, time, marital status, age, gender, body mass index [BMI], and race), vital signs (systolic blood pressure, and diastolic blood pressure), comorbidities (acute pancreatitis, cerebrovascular disease, central nervous system [CNS] inflammation, chronic obstructive pulmonary disease [COPD], diabetes, hypertension, respiratory failure), laboratory indicators (albumin, alkaline phosphatase [ALP], alanine aminotransferase [ALT], aspartate aminotransferase [AST], basophils, creatinine kinase MB, creatinine, eosinophils, glucose, hemoglobin A1c [HbA1c], lactate, lymphocytes, neutrophils, alveolar partial pressure of carbon dioxide [PaCO2], platelets, partial pressure of oxygen [PaO2], potassium, urea nitrogen, white blood cells [WBC]), severity at admission (assessed by Logistic organ dysfunction score [LODS], Oxford acute severity of illness score [OASIS], systemic inflammatory response syndrome [SIRS] score, SOFA score).

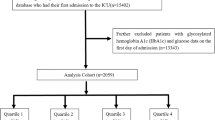

SHR was calculated with the following formula: SHR = Glucose (mg/dL)/(28.7 × HbA1c (%)−46.7). As no established normal reference range for SHR exists, it was categorized according to its quartiles in accordance with previously published methods15. For patients admitted to the ICU multiple times due to sepsis, only data from their first admission were extracted. Regarding laboratory indicators, the first measurement within 72 h was analyzed. To minimize the risk of reverse causality, laboratory indicators measured after the onset of the outcome were excluded. To reduce bias caused by sample exclusion, the percentage of missing values for each continuous variable was calculated. For variables with less than 20% missing values, a multiple imputation based on a random forest model was employed to predict missing values. For variables with more than 20% missing values, missing values were categorized and incorporated as dummy variables in the analysis.

Outcomes

The primary outcome was the risk of ARDS, defined by the PaO₂/FiO₂ ratio. ARDS severity was further categorized as follows: Mild ARDS: PaO₂/FiO₂ ≤ 300 mmHg with PEEP or CPAP ≥ 5 cm H₂O; Moderate ARDS: PaO₂/FiO₂ ≤ 200 mmHg with PEEP ≥ 5 cm H₂O; Severe ARDS: PaO₂/FiO₂ ≤ 100 mmHg with PEEP ≥ 5 cm H₂O. The secondary outcome was in-hospital mortality. The follow-up period spanned from admission until the occurrence of the outcome or the patient’s discharge, whichever occurred first.

Statistical analysis

Continuous variables were expressed as mean (standard deviation [SD]) or median (interquartile range [IQR]). Student’s t-tests or non-parametric tests were applied as appropriate for comparison. Categorical variables were presented as frequencies and percentages (%), and Pearson’s chi-square test or Fisher’s exact test was applied for comparisons between groups. Hazard ratios (HRs) and 95% confidence intervals (CIs) for SHR and ARDS were calculated using the Cox proportional hazards model. Multivariate adjustments were performed. Model 1 represented the unadjusted analysis. Model 2 was adjusted for age, gender, marital status, and race. Model 3 included adjustments for age and gender, marital status, BMI, albumin, ALT, AST, basophils, ALP, creatinine, PaCO2, PaO2, platelets, potassium, urea nitrogen, acute pancreatitis, cerebrovascular disease, CNS inflammation, COPD, diabetes, hypertension, respiratory failure, insulin, LODS, OASIS, SIRS, and race. To avoid multicollinearity in Model 3, collinearity was assessed by calculating the variance inflation factor (VIF), and variables with VIF > 5 were excluded. In addition, to explore the potential nonlinear relationship between SHR and outcomes, restricted cubic spline (RCS) plots were generated. Subgroup analyses were conducted to explore the consistency of SHR and outcomes across populations with varying characteristics. The likelihood ratio test was employed to evaluate the association between SHR and outcome variables. All statistical analyses were conducted using R version 4.4.0 (The R Foundation for Statistical Computing, Vienna, Austria). The two-tailed p-value was less than 0.05.

Ethical declarations

The MIMIC-IV database was approved by the Massachusetts Institute of Technology (Cambridge, MA) and Beth Israel Deaconess Medical Center (Boston, MA), and consent was obtained for the collection of original data. All procedures performed in studies involving human participants were in accordance with the ethical standards of the institutional and national research committee and with the 1964 Declaration of Helsinki and its later amendments or comparable ethical standards. Hence, this study may qualify for exemption from institutional review board approval and the requirement for informed consent owing to its retrospective design, lack of direct patient intervention, and utilization of de-identified data.

Results

Baseline characteristics of patients

A total of 1,946 patients were included in the study. Comparison of variables before and after multiple interpolation revealed no statistically significant differences (p > 0.05, Supplementary Table 1). In the total study cohort, 664 developed ARDS, and 262 experienced in-hospital mortality. The median length of stay was 12 days. Patients predominantly consisted of male white patients aged over 60 years. Patients in the ARDS group exhibited higher in-hospital mortality and longer hospital stays. They also demonstrated lower ALP levels, higher AST levels, lower creatinine levels, higher glucose levels, lower platelet counts, higher potassium levels, lower urea nitrogen levels, higher WBC counts, and a higher incidence of lactate ≥ 2 mmol/L. In addition, they showed a higher incidence of acute pancreatitis, a lower incidence of cerebrovascular disease and diabetes, a higher incidence of hypertension and respiratory failure, and higher scores on LODS, OASIS, and SOFA, and higher SHR values (continuous) (all P < 0.05) (Table 1).

The baseline characteristics of patients who were divided into quartiles according to SHR are shown in Table 2 (interquartile ranges: Q1 = 0.193–0.905, Q2 = 0.905–1.138, Q3 = 1.138–1.461, Q4 = 1.461–7.413). Patients in the Q4 group exhibited the highest in-hospital mortality, the longest hospital stays, and the highest levels of creatinine kinase MB (≥ 10 ng/mL), creatinine, and glucose. In addition, they showed the lowest levels of lactate < 2 mmol/L but the highest levels of lactate ≥ 2 mmol/L, potassium, and urea nitrogen. They also presented the lowest incidence of WBC and cerebrovascular disease and hypertension, while conversely showing the highest incidence of respiratory failure. Furthermore, they exhibited the highest scores on LODS, OASIS, SIRS 4, and SOFA, along with the highest SHR values (P < 0.05).

Elevated SHR is significantly associated with increased risk of ARDS

Table 3 presents the results of the Cox regression analysis for the relationship between SHR and risk of ARDS and in-hospital mortality. The risk of ARDS and in-hospital mortality was significantly elevated with increasing SHR. This association remained significant after adjusting for all confounding factors (ARDS: HR [95% CI] = 1.425 [1.260, 1.612]; in-hospital mortality: HR [95% CI] = 1.408 [1.144, 1.733]). SHR was divided into quartiles and included as a categorical variable in the analysis. Compared to patients with low SHR levels (Q1), those with high SHR levels (Q4) were associated with a significantly heightened risk of ARDS. The risk associated with SHR was consistent across patients with mild and moderate ARDS. However, no statistically significant association was observed between SHR and the development of severe ARDS.

SHR approximately linearly associated with ARDS risk

An RCS plot analysis revealed an approximately linear elevation in the risk of ARDS and in-hospital mortality with rising SHR values (P > 0.05). This association remained consistent after adjusting for multiple confounding factors (Fig. 1). Furthermore, SHR was 1.141 when HR was 1. The sensitivity analyses were performed by dividing SHR into two groups: ≤1.141 and > 1.141. The results showed that the risk of ARDS was significantly higher in those with SHR > 1.141 compared to those with SHR ≤ 1.141 and remained significant after adjusting for confounding factors (HR [95% CI]: ARDS = 1.350 [1.144, 1.594]; Mild ARDS = 1.568 [1.211, 2.030]; Moderate ARDS = 1.438 [1.094, 1.889]) (Supplementary Table 2).

Results of RCS analyses. (A-C) SHR and risk of ARDS in patients with sepsis; (D-F) SHR and risk of in-hospital death in patients with sepsis. Model 1: unadjusted. Model 2: adjusted for age, gender, race and marital status. Model 3: adjusted for age, gender, race, marital status, BMI, albumin, ALT, AST, ALP, basophils, creatinine kinase MB, WBC, creatinine, PaCO2, platelets, PaO2, potassium, urea nitrogen, acute pancreatitis, cerebrovascular disease, CNS inflammation, COPD, DB, hypertension, respiratory failure, LODS, OASIS, SIRS.

Results of subgroup analysis

Subgroup analyses were performed based on gender, COPD, diabetes, hypertension, respiratory failure, insulin and acute pancreatitis. The results revealed a significant positive correlation between SHR and the risk of ARDS across various subgroups, including males (or females), individuals with/without COPD, those without diabetes, patients with/without hypertension, individuals with/without respiratory failure, and those without acute pancreatitis (all P < 0.05). An interaction between diabetes and SHR was also observed (Fig. 2).

Significant differences in prognosis and incidence of ARDS in patients with different SHR levels

To analyze the incidence of ARDS across SHR quartiles, cumulative event occurrence curves were employed to illustrate the probability distributions. During follow-up, significant differences in ARDS incidence were observed among the four SHR groups (Fig. 3A, P < 0.0001). To further evaluate the impacts of SHR on the secondary endpoint across the entire study population, a Kaplan-Meier survival curve analysis was conducted. The analysis results showed significant differences in the in-hospital mortality among all study populations classified based on SHR quartiles (Fig. 3B, P = 0.00019).

Discussion

This retrospective cohort study is the first to demonstrate the predictive value of SHR for ARDS risk and in-hospital mortality among sepsis patients. Elevated SHR was identified as a significant independent risk factor for severe ARDS and increased in-hospital mortality in this population, with this association remaining significant after adjustment for potential confounding factors. In addition, the study revealed a nearly linear correlation between SHR values and the incidence of ARDS and in-hospital mortality among sepsis patients.

Previous studies suggest that hyperglycaemia may increase the risk of ARDS through several mechanisms. Firstly, hyperglycaemia promotes oxidative stress and inflammatory responses by up-regulating the expression of pro-inflammatory cytokines, such as TNF-α and IL-6, while inhibiting anti-inflammatory mediators. This imbalance exacerbates lung endothelial cell injury and alveolar capillary barrier disruption16. Secondly, hyperglycaemia facilitates the accumulation of glycosylation end-products, which further aggravates lung inflammation and fibrosis through activation of RAGE receptors17. In addition, insulin resistance and hyperglycaemia may impair sodium channel (ENaC) function in alveolar epithelial cells, leading to reduced alveolar fluid clearance and exacerbating pulmonary oedema18. Collectively, these mechanisms underscore a biologically plausible link between hyperglycaemia and ARDS and identify potential targets for clinical intervention.

According to the results of the Cox proportional risk model analysis, elevated SHR remained significantly associated with an increased risk of ARDS after adjustment for multiple confounders (model 3). When SHR was analyzed as a continuous variable, all hazard ratios (HR) exceeded 1.2, with significant statistical significance (p < 0.05). Specifically, the HR for SHR (continuous variable) in Model 3 was 1.211 (95% CI: 1.063–1.379), with a p-value of 0.004. When SHR was divided into quartiles, the results of the trend analysis showed a significant increase in the risk of ARDS with increasing SHR. In particular, the highest quartile (Q4) had an HR of 1.570 (95% CI: 1.262–1.952) compared to the lowest quartile (Q1), with a p-value of < 0.001. This result indicated that the severity of stress hyperglycemia was strongly associated with the development of ARDS. This further confirmed the important role of stress hyperglycemia in ARDS19. Further stratified analysis by severity of ARDS revealed that SHR was associated with a significantly increased risk across patients with mild, moderate and severe ARDS. In particular, the risk ratio for SHR was highest in patients with severe ARDS. For example, in patients with severe ARDS, the HR for SHR (continuous variable) in model 3 was 1.418 (95% CI: 1.138–1.767), with a p-value of 0.002. This result suggests that stress hyperglycemia may serve as a stronger predictor of the development of severe ARDS. Sepsis is frequently complicated by organ dysfunction, with the lungs being among the most commonly affected organs20,21,22. In a retrospective cohort study involving macroscopic autopsies of critically ill surgical patients who died of sepsis or septic shock, approximately 90% of patients exhibit lung tissue damage23. ARDS is considered a potentially fatal outcome of severe sepsis. Gong et al.24 suggested that approximately 30% of all sepsis patients may develop ARDS25. A study26 has identified several risk factors associated with the development of ARDS in sepsis patients within 6 h of admission, including acute physiology and chronic health evaluation II score, shock status, pulmonary infectious agents, pancreatitis, and acute abdomen. A recent study27 using machine learning techniques found that ARDS patients with higher blood glucose levels had the highest mortality rates, uncovering that hyperglycemia may serve as a detrimental factor in prognostic outcomes in ARDS patients. Consistently, Vught et al.28 demonstrated that sepsis patients with hyperglycemia at admission were significantly correlated with poor prognostic outcomes, irrespective of the presence of diabetes. This finding was further supported by Hartmann et al.29who indicated that the variability in hyperglycemia during ICU admission was associated with a significant increase in all-cause mortality in patients admitted to the ICU due to COVID-19-related ARDS. Notably, this effect still existed even after adjusting for clinically predetermined confounding factors, such as diabetes, median procalcitonin, and fasting plasma glucose. In conclusion, our findings provide further evidence that high levels of SHR may increase the risk of ARDS in septic patients.

In addition, this study analyzed the relationship between SHR and the risk of in-hospital death. The findings demonstrated a significant association between elevated SHR and increased risk of in-hospital death. After adjusting for confounders, the HR for SHR (continuous variable) was 1.400 (95% CI: 1.158–1.693) in Model 3, with a p-value of < 0.001. The results of the trend analyses further supported this conclusion. When SHR was categorized into quartiles, the highest quartile (Q4) was associated with a significantly increased risk of in-hospital death compared to the lowest quartile (Q1), with an HR of 1.755 (95% CI: 1.223–2.520) and a p-value of < 0.001. These results suggested that stress hyperglycemia not only contributed to the development of ARDS, but also increased the in-hospital mortality of patients with sepsis risk. During sepsis, the body releases significant amounts of stress hormones, such as cortisol and catecholamines30,31. These hormones raise blood glucose levels to ensure sufficient energy supply to vital organs such as the brain and heart during stressful conditions. In addition, sepsis can induce insulin resistance, which is characterized by weakened cellular responsiveness to insulin, causing an elevation in blood glucose levels7,32,33. Therefore, sepsis patients may experience a persistent stressful hyperglycemic state during their illness. Our findings are consistent with several previous studies. The study by Leonidou et al.34 revealed that patients with stress hyperglycemic sepsis exhibited a higher 28-day in-hospital mortality rate compared to patients with diabetic sepsis and those with normal glucose levels. In addition, patients with stress hyperglycemic sepsis are closely associated with elevated production of inflammatory factors and adverse clinical outcomes, whereas stress hyperglycemia is a contributor to reduced glutathione synthesis. Given that glutathione exerts crucial effects on cellular defense against oxidative and nitrosative stress, this impact further exacerbates redox imbalances and stress responses in sepsis patients35. This disruption can impair energy utilization and contribute to a persistent elevation in blood glucose, creating a positive feedback loop.

RCS analysis in the present study revealed an approximately linear dose-response relationship between SHR and the risk of ARDS and in-hospital death. This finding deviates from the U-shaped associations reported in some previous studies. For instance, one study identified a U-shaped relationship between SHR and mortality36. Several factors may account for this discrepancy. Firstly, the narrow distribution of SHR in the present study population may have limited the ability to detect the non-linear trend at extreme exposure levels. Secondly, the adjustment strategies for potential confounders in different studies may influence the observed shape of the association. In addition, variations may also exist in the details of data cleaning, such as the timing of laboratory indicator extraction.

Our findings suggest that in the clinical management of sepsis patients, close monitoring and control of blood glucose levels may help reduce the risk of ARDS and improve patient prognosis. Specifically, early identification of sepsis patients with high SHR and aggressive glycaemic control measures, such as insulin therapy, may reduce the incidence of ARDS. Meanwhile, patients with high SHR require close monitoring for changes in pulmonary function and prompt intervention to mitigate respiratory deterioration. In addition, for septic patients who have already developed ARDS, the impact of stress hyperglycaemia on their prognosis should be considered, and treatment strategies should be adjusted accordingly to improve patient survival.

However, certain limitations still exist in this study. Firstly, the generalizability of these findings may be limited, as all enrolled patients are from the United States and are predominantly of White ethnicity. Secondly, the retrospective and observational nature of the study precludes the establishment of a definitive causal relationship. Thirdly, as a single-center study with a limited sample size, potential data bias may still persist due to residual confounding factors, despite the use of multivariate adjustments and subgroup analyses. Lastly, prospective cohort studies are necessitated to validate our findings.

Conclusions

Elevated SHR is closely associated with heightened in-hospital all-cause mortality among sepsis patients. The study results demonstrate that SHR can facilitate the early detection of ARDS in sepsis patients, promoting risk assessment and guiding subsequent interventions. However, further prospective studies are warranted to corroborate these findings.

Data availability

The datasets generated during and/or analyzed during the current study are available from the corresponding author on reasonable request.

References

Zhu, W., Zhang, Y. & Wang, Y. Immunotherapy strategies and prospects for acute lung injury: focus on immune cells and cytokines. Front. Pharmacol. 13, 1103309 (2022).

Sun, C. et al. Serum Mrp 8/14 as a potential biomarker for predicting the occurrence of acute respiratory distress syndrome induced by sepsis: A retrospective controlled study. J. Inflamm. Research, 2939–2949 (2024).

Monchi, M. et al. Early predictive factors of survival in the acute respiratory distress syndrome: a multivariate analysis. Am. J. Respir. Crit Care Med. 158, 1076–1081 (1998).

Chen, F., Huang, F. & Zhan, F. Correlation between serum transforming growth factor β1, interleukin–6 and neonatal respiratory distress syndrome. Experimental Therapeutic Med. 18, 671–677 (2019).

Lazzeri, C. et al. The prognostic role of hyperglycemia and glucose variability in covid-related acute respiratory distress syndrome. Diabetes Res. Clin. Pract. 175, 108789 (2021).

Reiterer, M. et al. Hyperglycemia in acute COVID-19 is characterized by insulin resistance and adipose tissue infectivity by SARS-CoV-2. Cell Metabol. 33, 2174–2188 (2021). e2175.

Marik, P. E. & Raghavan, M. Stress-hyperglycemia, insulin and Immunomodulation in sepsis. Intensive Care Med. 30, 748–756 (2004).

Yang, X. et al. Stress hyperglycemia is independently associated with persistent organ failure in acute pancreatitis. Dig. Dis. Sci. 67, 1879–1889 (2022).

Long, C., Fan, W., Liu, Y. & Hong, K. Stress hyperglycemia is associated with poor outcome in critically ill patients with pulmonary hypertension. Front. Endocrinol. 15, 1302537 (2024).

Zhang, C. et al. Relationship between stress hyperglycemia ratio and allcause mortality in critically ill patients: results from the MIMIC-IV database. Front. Endocrinol. 14, 1111026 (2023).

Li, L. et al. Prognostic significance of the stress hyperglycemia ratio in critically ill patients. Cardiovasc. Diabetol. 22, 275 (2023).

Yan, F. et al. Association between the stress hyperglycemia ratio and 28-day all-cause mortality in critically ill patients with sepsis: a retrospective cohort study and predictive model establishment based on machine learning. Cardiovasc. Diabetol. 23, 163 (2024).

Singer, M. et al. The third international consensus definitions for sepsis and septic shock (Sepsis-3). Jama 315, 801–810 (2016).

Hu, W. et al. Identification of indications for albumin administration in septic patients with liver cirrhosis. Crit. Care. 27, 300 (2023).

Liu, J. et al. Impact of stress hyperglycemia ratio on mortality in patients with critical acute myocardial infarction: insight from American MIMIC-IV and the Chinese CIN-II study. Cardiovasc. Diabetol. 22, 281 (2023).

Clemmer, J. S., Xiang, L., Lu, S., Mittwede, P. N. & Hester, R. L. Hyperglycemia-mediated oxidative stress increases pulmonary vascular permeability. Microcirculation 23, 221–229 (2016).

Guo, W. A., Knight, P. R. & Raghavendran, K. The receptor for advanced glycation end products and acute lung injury/acute respiratory distress syndrome. Intensive Care Med. 38, 1588–1598 (2012).

Zhang, L. et al. Diabetic endothelial microangiopathy and pulmonary dysfunction. Front. Endocrinol. 14, 1073878 (2023).

Vincent, J. L. et al. Sepsis in European intensive care units: results of the SOAP study. Crit. Care Med. 34, 344–353 (2006).

Sun, B. et al. Acute lung injury caused by sepsis: how does it happen? Front. Med. 10, 1289194 (2023).

Sygitowicz, G. & Sitkiewicz, D. Molecular mechanisms of organ damage in sepsis: an overview. Brazilian J. Infect. Dis. 24, 552–560 (2021).

Liu, Y. et al. GPA peptide attenuates sepsis-induced acute lung injury in mice via inhibiting oxidative stress and pyroptosis of alveolar macrophage. Oxid. Med. Cell. Longev. 2021, 5589472 (2021).

Torgersen, C. et al. Macroscopic postmortem findings in 235 surgical intensive care patients with sepsis. Anesth. Analgesia. 108, 1841–1847 (2009).

Gong, H. et al. Advanced development and mechanism of sepsis-related acute respiratory distress syndrome. Front. Med. 9, 1043859 (2022).

Bernard, G. R. et al. The American-European Consensus Conference on ARDS: Definitions, mechanisms, relevant outcomes, and clinical trial coordination. Am. J. Respir. Crit. Care Med. 149, 818–824 (1994).

Seethala, R. R. et al. Early risk factors and the role of fluid administration in developing acute respiratory distress syndrome in septic patients. Ann. Intensiv. Care. 7, 1–9 (2017).

Bai, Y., Xia, J., Huang, X., Chen, S. & Zhan, Q. Using machine learning for the early prediction of sepsis-associated ARDS in the ICU and identification of clinical phenotypes with differential responses to treatment. Front. Physiol. 13, 1050849 (2022).

van Vught, L. A. et al. Admission hyperglycemia in critically ill sepsis patients: association with outcome and host response. Crit. Care Med. 44, 1338–1346 (2016).

Hartmann, B. et al. Glycaemic variability is associated with all-cause mortality in COVID-19 patients with ARDS, a retrospective subcohort study. Sci. Rep. 12, 9862 (2022).

Mesotten, D., Vanhorebeek, I. & Van den Berghe, G. The altered adrenal axis and treatment with glucocorticoids during critical illness. Nat. Clin. Pract. Endocrinol. Metab. 4, 496–505 (2008).

Liu, W., Liu, T., Zheng, Y. & Xia, Z. Metabolic reprogramming and its regulatory mechanism in sepsis-mediated inflammation. J. Inflamm. Res. 1195–1207 (2023).

Aleman, L. & Guerrero, J. Hiperglicemia Por sepsis: Del mecanismo a La clínica. Revista Médica De Chile. 146, 502–510 (2018).

Wang, J., Zhu, C. K., Yu, J. Q., Tan, R. & Yang, P. L. Hypoglycemia and mortality in sepsis patients: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Heart Lung. 50, 933–940 (2021).

Leonidou, L. et al. Cytokine production and hospital mortality in patients with sepsis-induced stress hyperglycemia. J. Infect. 55, 340–346 (2007).

Biolo, G., Antonione, R. & De Cicco, M. Glutathione metabolism in sepsis. Crit. Care Med. 35, S591–S595 (2007).

Li, L. et al. Association of stress hyperglycemia ratio and mortality in patients with sepsis: results from 13,199 patients. Infection 1–10 (2024).

Acknowledgements

Not applicable.

Funding

This study was supported by the National Natural Science Foundation of China [grant number 82360245].

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

All authors contributed to the study conception and design. Writing - original draft preparation: Xianwei Jin; Writing - review and editing: Xianwei Jin, Wei Deng, Qiaoling Weng, Jia Min, Fen Liu; Conceptualization: Qiaoling Weng, Jia Min, Fen Liu; Methodology: Qiaoling Weng, Jia Min, Fen Liu; Formal analysis and investigation: Xianwei Jin, Wei Deng, Qiaoling Weng, Jia Min, Fen Liu; Resources: Jia Min, Fen Liu; Funding acquisition: Jia Min; Supervision: Jia Min, Fen Liu, and all authors commented on previous versions of the manuscript. All authors read and approved the final manuscript.

Corresponding authors

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher’s note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Supplementary Information

Below is the link to the electronic supplementary material.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if you modified the licensed material. You do not have permission under this licence to share adapted material derived from this article or parts of it. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Jin, X., Deng, W., Weng, Q. et al. Correlation between stress hyperglycemia ratio and risk of acute respiratory distress syndrome in patients with sepsis: a MIMIC-IV cohort study. Sci Rep 15, 34737 (2025). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-18349-4

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-18349-4