Abstract

This study aims to explore the association between the lactate-to-albumin ratio (LAR) and the risk of mortality in critically ill patients with hypertension. This is a retrospective cohort study utilizing data from the Medical Information Mart for Intensive Care IV (MIMIC-IV, v3.1) database. Participants were categorized into tertiles based on LAR levels (low: <0.46, intermediate: 0.46–0.81, high: >0.81). The primary outcome was 28-day mortality. Kaplan-Meier curves were used to compare survival probabilities among patients in different LAR tertiles. Multivariable COX proportional hazards regression analysis and restricted cubic spline (RCS) regression were employed to assess the association between LAR levels and mortality in hypertensive patients. Additionally, subgroup and mediation analyses were conducted. A total of 4,504 patients were included in this study. Kaplan-Meier survival curves revealed that hypertensive patients in the highest LAR tertile had the highest mortality rate (log-rank test, P < 0.001). Multivariable COX regression analysis demonstrated that higher LAR levels were independently associated with an increased risk of 28-day mortality (HR: 1.240, 95% CI: 1.138–1.351, P < 0.001). Compared to the lowest LAR tertile, patients in the highest LAR tertile had a significantly increased 28-day mortality risk (HR = 1.229, 95% CI: 1.035–1.459, P = 0.019). In the fully adjusted model (Model 5), the highest LAR tertile was independently associated with a 22.9% increased mortality risk (HR = 1.229, 95% CI: 1.035–1.459, P = 0.019) compared to the lowest tertile. Restricted cubic spline (RCS) regression indicated a non-linear relationship between LAR levels and mortality risk in the unadjusted model (non-linear P-value = 0.026). Subgroup analysis further identified interactions between BMI, antihypertensive therapy, and mortality in hypertensive patients. Finally, mediation analysis suggested that SOFA and SAPS II scores partially mediated the association between LAR and ICU survival time. LAR demonstrates utility as a prognostic marker for 28-day mortality in critically ill hypertensive patients, particularly in those with obesity or untreated hypertension.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Hypertension, a leading global chronic disease, has doubled in prevalence over the past three decades, affecting over 1.3 billion adults and increasingly younger populations1. Hypertension contributes to target organ damage through various mechanisms, impacting the cardiovascular system, kidneys, brain, retina, and microcirculation. Ultimately, it leads to severe complications such as cardiovascular diseases, stroke, and chronic kidney disease, making it a major risk factor for global morbidity and mortality2,3. Despite significant advancements in diagnosis and treatment, hypertension control rates remain suboptimal, particularly among critically ill patients, where management poses substantial challenges. This is especially true for patients admitted to intensive care units (ICUs), who often present with complex and rapidly progressing conditions. These individuals frequently suffer from multi-organ dysfunction, including heart failure, renal insufficiency, and stroke, which significantly complicates their treatment4. Furthermore, ICU patients with hypertension often exhibit severe hemodynamic instability, characterized by marked blood pressure fluctuations that are difficult to manage with conventional medications5. Studies have shown that short-term mortality rates among ICU hypertensive patients are significantly higher than those with stable hypertension, and their long-term prognosis is also poorer6. In hypertensive disease, persistent elevation of systemic vascular resistance leads to microvascular damage and impaired oxygen delivery, predisposing patients to lactate accumulation. Simultaneously, hypoalbuminemia is frequently observed in hypertensive patients with comorbidities such as chronic kidney disease and heart failure, reflecting both inflammatory and nutritional deficits. Thus, LAR is not only a marker of metabolic stress but also of systemic inflammation in hypertensive populations, making it a biologically plausible and clinically relevant prognostic biomarker. Therefore, early identification of high-risk patients and the implementation of proactive interventions are critical for improving outcomes.

However, current tools for assessing the prognosis of critically ill hypertensive patients remain limited. Traditional biomarkers, such as blood pressure, heart rate, and renal function indicators, provide some insight into patient conditions but have restricted predictive value7. Additionally, the dynamic nature of ICU patients’ health status makes it challenging to rely solely on single indicators to comprehensively evaluate their overall condition. Consequently, identifying a biomarker that integrates metabolic status, inflammatory response, and organ function could significantly enhance prognostic evaluation in critically ill hypertensive patients.

In recent years, there has been growing interest in exploring novel biomarkers for critical care applications. For instance, lactate, a marker of tissue hypoxia and metabolic dysfunction, has been widely used for early diagnosis, prognosis assessment, and risk stratification in patients with septic shock8. Albumin, an acute-phase reactant protein synthesized by the liver, promotes the formation of anti-inflammatory mediators such as protectins and resolvins, playing a role in inflammation resolution and anti-inflammatory processes9. Clinically, albumin levels are monitored to assess nutritional status and the severity of inflammatory responses. While traditional biomarkers (e.g., blood pressure, renal function) offer limited prognostic value in dynamic ICU settings, composite markers like LAR—integrating lactate (tissue hypoxia) and albumin (inflammation/nutrition)—may better reflect systemic stress10. Recent studies have highlighted the application of LAR in the diagnosis, treatment, and prognosis of various critical conditions, including severe pneumonia, acute kidney injury, and sepsis11,12,13,14,15. However, research on LAR’s predictive utility in critically ill hypertensive patients remains limited, necessitating further investigation.

This study aims to explore the relationship between LAR levels and all-cause mortality in critically ill hypertensive patients, providing valuable insights into their short- and long-term prognosis. The findings may serve as a basis for developing strategies to improve survival and recovery outcomes in this high-risk population.

Methods

Data source

In this retrospective cohort study, we utilized data obtained from the Medical Information Mart for Intensive Care IV (MIMIC-IV, v3.1) database. This publicly accessible, de-identified dataset is provided by Beth Israel Deaconess Medical Center (BIDMC) in Boston, Massachusetts16,17. The dataset includes patient demographics, laboratory measurements, medication records, and detailed clinical notes, making it a valuable resource for comprehensive healthcare research.

One of the authors Zhichao Zhao was granted full access to the MIMIC-IV database and extracted the relevant data for this study using certification number [Certification Number: 64701219]. The use of MIMIC-IV was approved by the Institutional Review Board (IRB) of BIDMC, and the requirement for individual patient consent was waived as the dataset fully complies with the Health Insurance Portability and Accountability Act (HIPAA) regulations.

This study was reported in accordance with the Strengthening the Reporting of Observational Studies in Epidemiology (STROBE) guidelines for observational research18.

Selection of participants

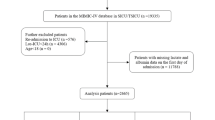

The inclusion criteria for this study were as follows (Fig. 1):

1) Patients diagnosed with hypertension, identified using International Classification of Diseases (ICD) codes (Supplementary Table 1).

2) Patients aged 18 years or older.

3) Patients admitted to the ICU for the first time.

The exclusion criteria were as follows:

1) Patients with missing survival data.

2) Patients with missing LAR or BMI data.

3) Patients with erroneous survival time or baseline data due to medical record errors.

Finally, extreme LAR values outside the 1st–99th percentiles were removed (n = 90), leading to a final study population of 4,504 patients for analysis. Data extraction was performed using Structured Query Language (SQL). For patients with multiple hospital admissions, only the first ICU admission was considered to ensure data accuracy and consistency.

Exposure

The primary exposure variable in this study was the LAR19. To minimize the influence of subsequent treatments on lactate and albumin levels, the first recorded blood lactate concentration and serum albumin levels after ICU admission were used.Tertile classification was selected to provide equal group sizes and to enhance reproducibility in future studies. Alternative methods (e.g., quartiles or clinical cutoffs) were considered, but tertiles provided stable sample distribution and statistical power. Thus, participants were categorized into three tertiles based on LAR levels: <0.46, 0.46–0.81, and > 0.81. Extreme LAR values (outside the 1st–99th percentiles) were excluded to mitigate outliers, a common practice in biomarker studies.

Variable extraction

The key variables extracted for analysis included demographics (age, body mass index [BMI], sex, and race); clinical comorbidities (heart failure [HF], myocardial infarction [MI], chronic obstructive pulmonary disease [COPD], type 2 diabetes mellitus [T2DM], cancer [CA], chronic kidney disease [CKD], and acute kidney injury [AKI]); initial ICU laboratory results (hemoglobin, red blood cell count, platelet count, creatinine, blood urea nitrogen, sodium, chloride, potassium, calcium, and white blood cell count); treatment measures (antihypertensive medications and glucocorticoids); vital signs (non-invasive blood pressure monitoring [NBPM], respiratory rate [RR], oxygen saturation [SpO₂], and temperature in Fahrenheit [Temperaturef]); and severity scores, including the Sequential Organ Failure Assessment (SOFA) score, Simplified Acute Physiology Score II (SAPS II), and Glasgow Coma Scale (GCS) score. APACHE II was not included due to extensive missingness in MIMIC-IV and collinearity with SOFA and SAPS II, which were more consistently available and demonstrated robust prognostic value.

Due to excessive missing data for BMI, samples with missing BMI values were excluded. For other variables with missing data of ≤ 20%, multiple imputation was performed to handle missing values20.

Statistical analyses

Continuous variables following a normal distribution were presented as mean ± standard deviation (SD) and compared using the t-test. Non-normally distributed continuous variables were expressed as median (interquartile range [IQR]) and compared using the Mann-Whitney U test. Categorical variables were presented as percentages and compared using the χ² test. The t-test was strictly applied to normally distributed variables, confirmed via Shapiro-Wilk test. For non-normal variables, Mann-Whitney U was applied. This ensures appropriate statistical testing.

To evaluate the 28-day survival differences among the three patient groups after ICU admission, Kaplan-Meier (KM) curves were first applied. Subsequently, a Cox proportional hazards regression model was used to assess the prognostic impact of LAR on survival, analyzing it as both a continuous and categorical variable. Candidate variables for Cox regression were selected a priori based on clinical relevance, prior literature, and data availability. A total of six Cox regression models were constructed, with each model progressively incorporating more covariates. The unadjusted model included no covariates, while Model 1 was adjusted for baseline demographic characteristics. Model 2 further adjusted for comorbidities, and Model 3 additionally incorporated treatment measures and vital signs within the ICU. Model 4 included the first recorded laboratory results in the ICU, and Model 5 further incorporated clinical severity scores.

To assess multicollinearity, the variance inflation factor (VIF) was calculated for all models, with VIF > 10 indicating significant collinearity (Supplementary Table 2)21. If the proportional hazards assumption was violated, the hazard ratio (HR) was interpreted as the time-weighted average over the entire follow-up period (Supplementary Table 3)22– 23.

To further clarify the relationship between LAR and survival prognosis. Sensitivity analyses, including restricted cubic spline (RCS) regression and subgroup analyses, were conducted to verify the robustness of the findings. RCS analysis with four knots was applied across all six Cox models. Cox models were adjusted stepwise for demographics, comorbidities, treatments, labs, and severity scores (SOFA, SAPS II). RCS with four knots tested nonlinear associations. Subgroup analyses were performed based on comorbidities and treatment measures. Additionally, a mediation analysis was conducted to explore the potential mechanisms by which LAR influences 28-day ICU survival. This mediation analysis specifically tested whether illness severity (SOFA and SAPS II) explained part of the LAR effect on mortality. By quantifying direct and indirect effects, we demonstrated that although severity scores mediate part of the relationship, a significant direct effect of LAR remained, strengthening the evidence for LAR as an independent biomarker. The cumulative effect of LAR on survival was divided into the average direct effect (ADE), while the average causal mediation effect (ACME) represented the effect mediated through an intermediate variable. Mediation was considered statistically significant if both the association between X and M and the association between M and Y were significant24 .

A two-tailed p-value < 0.05 was considered statistically significant. All statistical analyses were performed using R software (version 4.3.1).

Results

Baseline characteristics stratified by LAR tertiles revealed significant differences across multiple clinical parameters (Table 1). Patients with higher LAR levels exhibited elevated lactate and decreased albumin concentrations (P < 0.001). They also had higher white blood cell counts, serum creatinine, blood urea nitrogen, and potassium levels, while red blood cell counts, hemoglobin, platelet levels, and calcium concentrations were lower (P < 0.001). Acute kidney injury and type 2 diabetes were more prevalent in higher LAR groups (P < 0.001 and P = 0.013, respectively), whereas chronic obstructive pulmonary disease was less common (P = 0.001). Higher LAR was associated with increased severity of illness, as indicated by significantly higher SOFA and SAPS II scores (P < 0.001), as well as more frequent vasopressor use (P < 0.001). Mean arterial pressure was lower with increasing LAR (P < 0.001), and mortality rates progressively increased, with the highest LAR group experiencing the greatest 28-day mortality (P < 0.001).

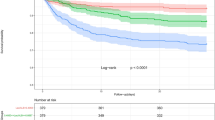

Kaplan-Meier survival analysis

Kaplan-Meier survival analysis demonstrated a significant association between LAR and 28-day survival probability (Fig. 2). Patients in the highest LAR tertile (> 0.81) exhibited the lowest survival probability over time, followed by the intermediate (0.46–0.81) and lowest (< 0.46) LAR groups. The survival curves diverged early and continued to separate throughout the observation period, with significantly lower survival in the highest LAR group (log-rank test, P < 0.001).

Cox regression analysis

Cox regression analysis revealed that LAR was significantly associated with 28-day ICU mortality in both continuous and categorical models (Table 2). In the continuous model, each unit increase in LAR was associated with a higher mortality risk (HR = 1.240, 95% CI: 1.138–1.351, P < 0.001) after full adjustment. In the categorical model, patients in the highest LAR tertile had a significantly increased risk of mortality compared to the lowest tertile (HR = 1.229, 95% CI: 1.035–1.459, P = 0.019), even after adjusting for demographic factors, comorbidities, treatments, and clinical severity scores. However, the intermediate LAR tertile did not show a statistically significant association in the fully adjusted model (P = 0.104), suggesting that the mortality risk is primarily driven by those with markedly elevated LAR levels. These results highlight the independent prognostic value of LAR, although part of its association may be mediated by illness severity.

RCS analysis

RCS analysis showed a nonlinear association between LAR and 28-day ICU mortality in the unadjusted model (P for nonlinearity = 0.026), with mortality risk increasing as LAR levels rose (Fig. 3). This nonlinear trend remained significant after adjusting for demographic factors (P = 0.036) but weakened with further adjustments for comorbidities and treatment factors. In the fully adjusted model, the association became more linear, and the nonlinearity was no longer statistically significant (P = 0.205), suggesting that the impact of LAR on mortality may be influenced by overall illness severity.

Subgroup analysis

Subgroup analysis demonstrated that the association between LAR and 28-day ICU mortality remained significant across most subgroups (Fig. 4). Higher LAR was consistently associated with increased mortality risk, with no significant interactions observed for age, CA, AKI, T2DM, COPD, MI, or HF (P for interaction > 0.05). However, the association was stronger in patients with a BMI > 30 (HR = 1.352, 95% CI: 1.193–1.533, P < 0.001) compared to those with lower BMI (P for interaction = 0.008), suggesting a potential modifying effect of obesity. Additionally, patients not receiving antihypertensive treatment exhibited a higher mortality risk (HR = 1.399, 95% CI: 1.201–1.631, P < 0.001) compared to those on antihypertensive therapy (P for interaction < 0.001), indicating that medication use may influence outcomes. These findings suggest that while LAR is a robust predictor of mortality, certain clinical factors may modify its prognostic impact.

Mediation analysis

Mediation analysis demonstrated that SOFA and SAPS II partially mediated the association between LAR and ICU survival time (Fig. 5). In the SOFA model, the ACME was significant (P < 0.001), with 42.2% (95% CI: 33.7–54.1%) of the total effect mediated through SOFA. Similarly, in the SAPS II model, the proportion of mediation was 46.3% (95% CI: 38.9–58.0%, P < 0.001), indicating a stronger mediating effect. The ADE remained significant in both models (P < 0.001), suggesting that while illness severity explains part of the relationship, LAR independently contributes to survival outcomes. These findings indicate that LAR’s predictive value for ICU survival is partly mediated by clinical severity scores, reinforcing its role as a prognostic marker.

Discussion

This study utilizes the extensive MIMIC-IV database to explore the relationship between LAR levels and mortality in critically ill hypertensive patients. Our findings indicate that even after accounting for other factors that may influence the risk of mortality in critically ill hypertensive patients, higher LAR levels are still associated with an increased risk of death. Importantly, the mediation analysis is presented as a supporting analysis and indicates that illness severity mediates part—but not all—of LAR’s association with mortality. Furthermore, the RCS analysis reveals that this association is non-linear. Additionally, subgroup analysis further identifies an interaction between BMI, hypertension treatment, and mortality in hypertensive patients. Lastly, mediation analysis demonstrates that SOFA and SAPS II scores partially mediate the association between LAR and ICU survival time. Although APACHE II was excluded due to missingness and collinearity concerns, a subset sensitivity analysis with available APACHE II data showed consistent associations.

LAR, as a novel biomarker, has demonstrated significant value in the prognosis assessment of various critical illnesses in recent years. A single-center retrospective cohort study revealed25 that critically ill COVID-19 patients with a median LAR value of 0.53 had an ICU mortality rate as high as 44.8%, and an elevated LAR was significantly associated with decreased survival rates (hazard ratio HR = 1.39, 95% CI: 1.27–1.52). The area under the ROC curve (AUC) indicated that LAR’s predictive performance for ICU mortality was superior to traditional indicators such as lactate or albumin used alone. Additionally, in sepsis-related acute respiratory distress syndrome (ARDS), elevated lactate levels have been identified as an independent risk factor (OR = 1.684), while hypoalbuminemia may further worsen prognosis by exacerbating inflammatory responses and microvascular leakage26. Similarly, in bacterial sepsis patients with cirrhosis, albumin infusion significantly improved hemodynamics (e.g., OR = 3.9 for reversing hypotension) and reduced the risk of hyperlactatemia, suggesting that the clinical value of LAR may extend to prognosis stratification in conditions such as septic shock27. Notably, the predictive value of LAR is not limited to infectious diseases. In organ dysfunction assessment, LAR is significantly correlated with the Sequential Organ Failure Assessment (SOFA) score and the Acute Physiology and Chronic Health Evaluation II (APACHE II) score, potentially reflecting the combined state of systemic oxidative stress, microcirculatory dysfunction, and energy metabolism disturbances28. Therefore, as a composite indicator integrating lactate (a marker of tissue hypoxia) and albumin (a marker of inflammation/nutritional status), LAR has broad applicability in various critical illnesses in the ICU.

We explicitly defined variable selection as based on clinical relevance, prior literature, and data availability to support model robustness. We restated tertile cutoffs (< 0.46, 0.46–0.81, > 0.81) and rationale for balanced distribution and reproducibility. Although our study did not delve deeply into the association between elevated LAR levels and increased mortality risk in critically ill hypertensive patients, we hypothesize that the inverse relationship between the two may be attributed to several physiological mechanisms. First, tissue hypoxia and lactate metabolism dysfunction: Hypertensive crises can lead to vascular endothelial dysfunction and inadequate microcirculatory perfusion, resulting in increased anaerobic metabolism and lactate accumulation. Literature suggests that elevated lactate levels are associated with high anion gap (AG) metabolic acidosis in critically ill patients, and unmeasured organic anions (UOAs) may further exacerbate lactate’s inhibition of mitochondrial function29. Additionally, hypertensive patients often have concurrent cardiac and renal insufficiency, and reduced lactate clearance capacity may amplify its toxic effects. Second, the multifaceted pathological effects of hypoalbuminemia: Albumin is not only crucial for maintaining colloid osmotic pressure but also possesses anti-inflammatory, antioxidant, and endothelial protective properties. Hypoalbuminemia in critically ill hypertensive patients may stem from capillary leakage, reduced hepatic synthesis, or inflammatory consumption (e.g., IL-6-mediated acute phase response)30. Low albumin levels can impair free radical scavenging capacity, exacerbate oxidative stress damage, and promote increased vascular permeability and organ edema, further worsening hypertension-related cardiac, cerebral, and renal injuries27. Third, the inflammatory-metabolic vicious cycle: Elevated LAR may signify the interplay between systemic inflammatory response syndrome (SIRS) and metabolic imbalance. High sympathetic nervous system activity in hypertensive patients can activate the NF-κB pathway, promoting the release of pro-inflammatory cytokines (e.g., IL-6, TNF-α), which in turn suppress albumin synthesis and accelerate lactate production28,30. Moreover, the loss of albumin’s antioxidant function may exacerbate mitochondrial dysfunction, creating a vicious cycle of “lactate-inflammation-oxidative stress”28,31. Fourth, the association between hemodynamics and organ perfusion: Elevated LAR may reflect insufficient effective circulating blood volume. Studies have shown that albumin infusion can reduce lactate production by improving hemodynamics (e.g., lowering heart rate, reversing hypotension), while abnormal vascular tone regulation in critically ill hypertensive patients may disrupt this mechanism27. Simultaneously, lactate accumulation can inhibit myocardial contractility, exacerbating cardiac insufficiency in hypertensive patients and leading to secondary injuries such as cardiorenal syndrome26,31. In summary, as an integrative indicator of tissue hypoxia, inflammatory response, and metabolic disturbances, LAR may influence the prognosis of critically ill hypertensive patients through multi-organ interaction mechanisms. Future studies are needed to further validate the threshold effects and intervention targets of LAR in this population.

In our study, restricted cubic spline (RCS) analysis further confirmed the existence of a non-linear relationship, with an increasing risk of mortality as LAR levels rise. Subgroup analysis revealed that among critically ill hypertensive patients, those with a BMI > 30 and those not receiving hypertension treatment had a higher risk of mortality. This may be related to the unique metabolic disturbances and chronic inflammatory state associated with obesity. Studies have shown32 that obesity (BMI ≥ 24 kg/m²) is an independent risk factor for mortality in septic patients, and patients with a BMI > 30 may exhibit more pronounced insulin resistance, adipose tissue inflammation, and oxidative stress, leading to lactate accumulation and reduced albumin synthesis, thereby amplifying the prognostic value of LAR. Additionally, obese patients often have concurrent multi-organ dysfunction (e.g., fatty liver, renal insufficiency), which may further impair the metabolic clearance of albumin and exacerbate the pathophysiological effects of LAR33. On the other hand, uncontrolled hypertension may accelerate endothelial dysfunction, microcirculatory perfusion insufficiency, and organ ischemia-hypoxia, resulting in increased lactate production and exacerbated albumin loss. Simultaneously, the progression of underlying diseases in untreated patients may be more severe, with poorer organ reserve function, making LAR a more sensitive marker of stress and metabolic imbalance32,33. Furthermore, antihypertensive medications (e.g., ACEI/ARB or beta-blockers) may indirectly reduce lactate levels or stabilize albumin metabolism by improving hemodynamics and microcirculatory perfusion, thereby attenuating the prognostic association of LAR33. LAR’s prognostic value persisted after adjusting for illness severity (SOFA/SAPS II), supporting its role as an accessible biomarker for risk stratification. Mediation analysis indicates that SOFA and SAPS II scores partially mediate the association between LAR and survival time in ICU hypertensive patients. First, the SOFA score, as a quantitative indicator of sequential organ failure, reflects the cumulative effects of multi-organ dysfunction. Elevated LAR may directly impair mitochondrial function and induce oxidative stress through lactate accumulation, or exacerbate capillary leakage and inflammatory responses through hypoalbuminemia, ultimately leading to the deterioration of organ functions such as the heart, kidneys, and liver32,33. This pathway aligns with the causal chain of LAR → SOFA score → survival time, supporting organ failure as a significant mediator of LAR’s impact on prognosis. Second, the SAPS II score integrates age, physiological parameters, and chronic disease status, and its partial mediating role suggests that LAR may indirectly shorten survival time by affecting systemic physiological stability (e.g., acid-base balance, hemodynamics). For instance, hyperlactatemia may exacerbate metabolic acidosis, leading to abnormal vascular tone and myocardial suppression, while hypoalbuminemia may worsen pulmonary or systemic edema through reduced colloid osmotic pressure, further increasing the respiratory and circulatory system scores in the SAPS II score33. This mechanism is consistent with the strong predictive ability of SAPS II for prognosis in septic patients32. Notably, SOFA and SAPS II only partially mediate the association between LAR and prognosis, suggesting the existence of other unaccounted mediating factors, such as microcirculatory dysfunction, immune suppression, or activation of specific inflammatory pathways (e.g., IL-6, TNF-α). Future studies could incorporate additional biological markers (e.g., CRP, cytokines) to further elucidate the complete pathways through which LAR influences prognosis.

However, our study has several limitations that warrant discussion. First, as a retrospective cohort analysis, this study cannot entirely avoid the influence of confounding factors. For instance, variations in patient fluid resuscitation strategies and comorbidity management may affect lactate and albumin levels, but these treatment details were not fully recorded in the database. Additionally, the MIMIC-IV database lacks certain indicators closely related to the pathophysiology of hypertension (e.g., inflammatory cytokine levels, oxidative stress markers), which may limit a deeper exploration of the mechanisms underlying the association between LAR and prognosis. Second, although MIMIC-IV is a rich resource, its data originate from a single center, which may restrict the generalizability of our findings.

Data availability

The datasets generated and analyzed during the current study are available in the MIMIC-IV database deposited in https://physionet.org.

Abbreviations

- MIMIC-IV:

-

Medical information mart for intensive care-IV, a comprehensive database from the Beth Israel deaconess medical center

- ICU:

-

Intensive care unit, where critical patients are treated

- BIDMC:

-

Beth Israel deaconess medical center, the source hospital for MIMIC-IV data

- IRB:

-

Institutional review board, overseeing ethical research conduct

- HIPAA:

-

Health insurance portability and accountability act, ensuring patient data privacy

- STROBE:

-

Strengthening the reporting of observational studies in epidemiology, guidelines for reporting observational data

- ICD:

-

International classification of diseases, a standardized code system for diseases

- SQL:

-

Structured query language, used for managing database information

- COX:

-

Cox proportional hazards model, a statistical technique for time-to-event data analysis

- HR:

-

Hazard ratio, measures the effect of a treatment or risk factor

- CI:

-

Confidence interval, indicates the reliability of an estimate

- SD:

-

Standard deviation, measures the amount of variation in a set of values

- IQR:

-

Interquartile range, a measure of statistical dispersion

- KM:

-

Kaplan–Meier, a method for estimating survival rates

- RCS:

-

Restricted cubic spline, used for modeling nonlinear relationships

- VIF:

-

Variance inflation factor, assesses multicollinearity in regression analyses

- ADE:

-

Average direct effect, part of causal mediation analysis

- ACME:

-

Average causal mediation effect, another component of causal mediation analysis

- Lac:

-

Lactate, an indicator of metabolic stress

- Alb:

-

Albumin, a protein used to assess nutritional status

- LAR:

-

Lactate-to-Albumin ratio, a prognostic marker in critical care

- BMI:

-

Body mass index, a measure of body fat based on height and weight

- WBC:

-

White blood cell, part of the immune system response

- RBC:

-

Red blood cell, essential for oxygen transport

- Hb:

-

Hemoglobin, an iron-containing protein in red blood cells

- PLT:

-

Platelet, crucial for blood clotting

- Cr:

-

Creatinine, a marker of kidney function

- BUN:

-

Blood urea nitrogen, another kidney function indicator

- Na:

-

Sodium, an essential electrolyte

- Cl:

-

Chloride, an important electrolyte

- K:

-

Potassium, crucial for nerve and muscle function

- Ca:

-

Calcium, vital for bone health and cellular functions

- HF:

-

Heart Failure, a chronic condition affecting heart function

- MI:

-

Myocardial Infarction, commonly known as a heart attack

- COPD:

-

Chronic obstructive pulmonary disease, a lung condition

- T2DM:

-

Type 2 diabetes mellitus, a metabolic disorder

- CA:

-

Cancer, a group of diseases involving abnormal cell growth

- CKD:

-

Chronic kidney disease, the gradual loss of kidney function

- AKI:

-

Acute kidney injury, sudden episode of kidney failure or damage

- NBPM:

-

Non-invasive blood pressure monitoring, for tracking blood pressure

- RR:

-

Respiratory rate, the number of breaths per minute

- SpO₂:

-

Oxygen saturation, the level of oxygen in the blood

- Temperaturef:

-

Temperature in Fahrenheit, measuring body heat

- SOFA:

-

Sequential organ failure assessment, scoring to assess organ function

- SAPS II:

-

Simplified acute physiology score II, used to predict ICU mortality

- GCS:

-

Glasgow coma scale, assesses the level of consciousness

References

Natale, F., Franzese, R., Franzese, R. & Luisi, E. Luisi, Ettore. The increasing problem of resistant hypertension: We’ll manage till help comes! medical sciences (Basel, Switzerland, (2024).

Liu, X., Liu, X., Yang, M., Yang, M. & Lip, Gregory, Y. H. Plasma biomarkers for hypertension-mediated organ damage detection (A Narrative Review. Biomedicines, 2024).

Fountoulakis, P., Kourampi, I., Theofilis, P. & Marathonitis Anastasios., Papamikroulis, Georgios Angelos. Oxidative stress biomarkers in hypertension (Current medicinal chemistry, 2025).

Mayer, S. A. et al. Clinical practices, complications, and mortality in neurological patients with acute severe hypertension: the studying the treatment of acute hypertension registry. Crit. Care Med. 39, 2330–2336 (2011).

Peng, Y., Meng, K., He, M., Zhu, R. & Guan, H. Clinical characteristics and prognosis of 244 cardiovascular patients suffering from coronavirus disease in wuhan, China. J. Am. Heart Association. 9 (19), e016796 (2020).

Vincent, J. L. & De Backer, D. Circulatory shock. N. Engl. J. Med. 369 (18), 1726–1734 (2013).

Jimeno, S., Jimeno, S., Jimeno, S., Ventura, P. S. & Ventura, Paula, S. Prognostic implications of neutrophil-lymphocyte ratio in COVID-19. Eur. J. Clin. Invest. 51 (1), e13404 (2020).

Evans, L. et al. Surviving sepsis campaign: international guidelines for management of sepsis and septic shock 2021 [J]. Crit. Care Med. 49 (11), e1063 (2021). e1143.

Lu, Y. et al. Association between lactate/albumin ratio and all cause mortality in patients with acute respiratory failure: A retrospective analysis [J]. PloS One. 16 (8), e0255744 (2021).

Liu, Q. et al. Association between lactate to albumin ratio and 28 days all cause mortality in patients with acute pancreatitis: A retrospective analysis of the MIMIC⁃IV database [J]. Front. Immunol. 13, 1076121 (2022).

Erdoğan, M. & Findikli, H. A. Prognostic value of the lactate/albumin ratio for predicting mortality in patients with Pneumosepsis in intensive care units [J]. Medicine(Baltimore) 101 (4), e28748 (2022).

Ailustaoglu, B. A., Aksay, E. & Oray, N. C. Lactate measurements accurately predicts 1 week mortality in emergency department patients with acute kidney injury [J]. Turk. J. Emerg. Med. 19 (4), 136–140 (2019).

Zhu, X. et al. The lactate/albumin ratio predicts mortality in critically ill patients with acute kidney injury: an observational multicenter study on the eICU database [J]. Int. J. Gen. Med. 14, 10511–10525 (2021).

rnauBarrés, I. et al. Serum albumin is a strong predictor of sepsis outcome in elderly patients [J]. Eur. J. Clin. Microbiol. Infect. Dis. 38 (4), 743–746 (2019).

Cakir, E. & Turan, I. O. Lactate/albumin ratio is more effective than lactate or albumin alone in predicting clinical outcomes in intensive care patients with sepsis. Scand. J. Clin. Lab. Invest. 81 (3), 225–229 (2021).

Johnson, A. et al. MIMIC-IV (version 3.0). In: PhysioNet, (2024). https://doi.org/10.13026/hxp0-hg59

Johnson, A. E. W. et al. MIMIC-IV, a freely accessible electronic health record dataset. Sci. Data. 10 (1), 1. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41597-022-01899-x (2023).

Vandenbroucke, J. P. et al. Strengthening the reporting of observational studies in epidemiology (STROBE): explanation and elaboration. PLoS Med. 4 (10). https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pmed.0040297 (2007). e297.

Lichtenauer, M. et al. and C. Jung: The lactate/albumin ratio: a valuable tool for risk stratification in septic patients admitted to ICU. Int J Mol Sci, 18(9) (2017). https://doi.org/10.3390/ijms18091893

Austin, P. C., White, I. R., Lee, D. S. & van Buuren, S. Missing data in clinical research: A tutorial on multiple imputation. Can. J. Cardiol. 37 (9), 1322–1331. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.cjca.2020.11.010 (2021).

Nunez, E. R. et al. Wiener: adherence to follow-up testing recommendations in US veterans screened for lung cancer, 2015–2019. JAMA Netw. Open. 4 (7). https://doi.org/10.1001/jamanetworkopen.2021.16233 (2021). e2116233.

Sjolander, A. & Dickman, P. W. Why test for proportional hazards-or any other model assumptions? Am. J. Epidemiol. 193 (6), 926–927. https://doi.org/10.1093/aje/kwae002 (2024).

Stensrud, M. J. & Hernan, M. A. Why test for proportional hazards?? JAMA 323 (14), 1401–1402. https://doi.org/10.1001/jama.2020.1267 (2020).

Imai, K., Keele, L. & Tingley, D. A general approach to causal mediation analysis. Psychol. Methods. 15 (4), 309–334. https://doi.org/10.1037/a0020761 (2010).

Kokkoris, S., Gkoufa, A., Katsaros, D. E. & Karageorgiou, S. Kavallieratos, Fotios. Lactate to albumin ratio and mortality in patients with severe coronavirus disease-2019 admitted to an intensive care unit (Journal of clinical medicine, 2024).

Zhao, C., Li, Y., Wang, Q. & Yu, G. Hu, Peng. Establishment of risk prediction nomograph model for sepsis related acute respiratory distress syndrome (Zhonghua wei zhong bing ji jiu yi xue, 2023).

Philips, C. A., Maiwall, R., Sharma, M. K. & Jindal, A. Choudhury, Ashok kumar. Comparison of 5% human albumin and normal saline for fluid resuscitation in sepsis induced hypotension among patients with cirrhosis (FRISC study): a randomized controlled trial. Hep. Intl., 15(4). (2021).

Jamialahmadi, T., Jamialahmadi, T., Panahi, Y., Safarpour, M. A. & Ganjali, S. Association of serum PCSK9 levels with antibiotic resistance and severity of disease in patients with bacterial infections admitted to intensive care units. J. Clin. Med., 8(10). (2019).

Hussain, M., Zaki, K. E., Asef, M. A., Song, H. & Treger, R. M. Unmeasured organic anions as predictors of clinical outcomes in lactic acidosis due to sepsis. J. Intensive Care Med.,. (2023).

Çakırca, T. D., Çakırca, G., Torun, A. & Bindal, A. Üstünel, Murat. comparing the predictive values of procalcitonin/albumin ratio and other inflammatory markers in determining COVID-19 severity (Pakistan journal of medical sciences, 2023).

Hu, X., Yang, H. C., Chen, Y. & Zhong, J. Ping. Clinical characteristics and risk factors for severity of COVID-19 outside wuhan: a double-center retrospective cohort study of 213 cases in hunan, China. Ther. Adv. Respir. Dis., 14. (2020).

Chen, X., Zhou, X., Zhao, H., Wang, Y. & Pan, H. Clinical value of the lactate/albumin ratio and lactate/albumin ratio × age score in the assessment of prognosis in patients with sepsis. Front. Med., 8. (2021).

Basile-Filho, A., Lago, A. F., Menegueti, M. G. & Nicolini, E. A. Lorena aparecida de brito. The use of APACHE II, SOFA, SAPS 3, C-reactive protein/albumin ratio, and lactate to predict mortality of surgical critically ill patients: A retrospective cohort study. Medicine 98 (26), e16204 (2019).

Acknowledgements

We acknowledge the support from the affiliated Yangming hospital of ningbo university, Maoming People’s Hospital and Renji College, Wenzhou Medical University and the valuable feedback from anonymous reviewers.

Funding

The study was censored and approved by the Yuyao Municipal HealthScience and Technology PlanProject (Key Project; No 2025YZD02).

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

Kaifeng Han and Guode Li conceived the study; Chen Chen, Xian Wei, Jijiong Yu and Yujie Lv performed data analysis; Junlin Huang and Wenbin Wang drafted the manuscript; Zhichao Zhao supervised and revised the work. All authors approved the final version.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Ethics approval and consent to participate

The use of the MIMIC database for research purposes has been approved by the Committee on the Use of Human Subjects (COUHES) at the Massachusetts Institute of Technology (MIT), and no additional ethical approval was required for this study.

The data used in this study were de-identified, i.e., all personal health information (PHI) was removed or encrypted to protect patient privacy. Therefore, this retrospective analysis did not require informed consent from individual patients.

Additional information

Publisher’s note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Supplementary Information

Below is the link to the electronic supplementary material.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if you modified the licensed material. You do not have permission under this licence to share adapted material derived from this article or parts of it. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Han, K., Li, G., Wei, X. et al. Lactate-to-albumin ratio as an independent predictor of 28-day ICU mortality in patients with hypertension: a retrospective cohort study. Sci Rep 15, 33018 (2025). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-18481-1

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-18481-1