Abstract

This work explores a novel integration of experimental conversion of waste cooking oil (WCO) into biodiesel with advanced machine learning modeling to optimize transesterification outcomes. A reusable CaO catalyst derived from egg shells was employed, delivering a more affordable and sustainable option compared to typical homogeneous catalysts. A total of 16 experimental runs were conducted to investigate the effects of catalyst concentration (CC), reaction temperature (RT), and methanol-to-oil molar ratio (MOR) on biodiesel yield. Four boosted ML algorithms XGBoost, AdaBoost, Gradient Boosting Machine (GBM), and CatBoost were applied to model the process, with hyperparameter tuning via grid search and validation through k-fold cross-validation (k = 5) and residual plots to ensure reliability and mitigate overfitting. CatBoost emerged as the best-performing model (R² = 0.955, RMSE = 0.83, MSE = 0.68, MAE = 0.52), predicting a maximum biodiesel yield of 95% at 3% CC, 80 °C RT, and a 6:1 MOR. Feature importance and partial dependence plots identified MOR and CC as the most influential parameters. Engine performance tests further validated the practical viability of CaO-based biodiesel, showing 26% lower CO emissions and 13% lower smoke emissions compared to diesel, resulting in a marginal 2.83% decline in brake thermal efficiency alongside a 4.31% rise in fuel consumption. This interdisciplinary approach combining green catalyst development with interpretable machine learning demonstrates a promising pathway for cleaner energy applications and data-driven optimization in biodiesel research.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

In recent decades, the search for alternative diesel fuels has intensified due to concerns over emissions, resource depletion, and rising fuel costs1. The conversion of waste and biomass into useful energy has gained attention as a sustainable fuel exploration strategy, offering numerous environmental and economic benefits2,3. Among various feedstocks, WCO has emerged as a promising source for biodiesel production due to its high availability and cost-effectiveness4,5. The global generation of WCO has increased significantly with the growth of the food industry and rising populations, making it a viable alternative to conventional biofuels. Unlike raw vegetable oils, WCO eliminates the need for additional cultivation or extraction, minimizing operational expenses and ecological footprint. However, the direct use of WCO in diesel engines, generators, and marine engines presents challenges such as high carbon footprint, increased fuel consumption, and lower efficiency, necessitating fuel upgrading techniques6,7,8.

Transesterification remains the most effective method for biodiesel conversion, where alcohols and catalysts enhance production yield. Catalyst type and concentration, along with alcohol selection, significantly influence fuel properties and conversion efficiency. Methanol serves as a preferred choice due to its high reactivity, cost-effectiveness, and availability, making it the preferred alcohol in biodiesel production9,10. Catalysts play a critical role in transesterification, influencing reaction efficiency, biodiesel properties, and yield. They facilitate the chemical transformation of triglycerides in biofuel, yielding biodiesel and glycerol. Common catalysts include homogeneous catalysts, like NaOH, KOH, and H₂SO₄, which provide high reaction rates but require extensive purification and generate chemical wastewater11,12. Heterogeneous catalysts like CaO, MgO, Al₂O₃-based oxides and etc. offer advantages such as reusability, easy separation, and minimal environmental impact, improving reaction efficiency13,14. Enzymatic catalysts, particularly lipases, allow biodiesel production under mild conditions, eliminating soap formation, though their high cost and long reaction times limit industrial applications15,16. Nano-catalysts provide enhanced surface area, higher catalytic efficiency, and lower energy consumption, optimizing transesterification reactions17,18.

Biomass-sourced catalytic materials are increasingly recognized for their low cost, eco-friendly nature, and reusability. Derived from natural waste materials, they promote sustainable transesterification while reducing chemical waste. Agricultural residues such as rice husk ash, palm kernel shells, and sugarcane bagasse ash exhibit high silica and calcium content, improving biodiesel yield19,20,21. Egg shell-derived CaO, a widely explored biomass catalyst, provides high catalytic efficiency and reusability, making it a sustainable alternative22,23. Industrial byproducts such as red mud, fly ash, and spent bleaching earth contribute to waste valorization, requiring modifications to improve catalytic activity24,25. Nano-enhanced biomass catalysts, such as nano-modified CaO or biochar-supported catalysts, improve reactant diffusion and conversion rates, minimizing reliance on synthetic chemical catalysts26,27.

The RT, MOR, and process duration significantly impact yield and quality. Optimizing these parameters ensures maximum efficiency, but conventional iterative experimentation often demands substantial time and resources. To overcome these challenges, researchers have employed DOE tools such as ANOVA and RSM. However, these methods struggle with nonlinear interactions and exhibit higher error rates when analyzing complex reaction dynamics28,29. The rapid evolution of AI and ML technologies has facilitated data-driven optimization approaches for biodiesel production. ML algorithms such as Boosted Decision Trees (XGBoost, AdaBoost), SVR, and ANN enhance predictive accuracy and optimization capabilities. These models automate parameter selection, reduce experimental costs, and maximize biodiesel yield by learning intricate relationships between CC, RT, MOR, and mixing speed30,31.

Additionally, ML-driven interpretability tools such as SHAP analysis, Pearson correlation heatmaps, and partial dependence plots allow researchers to fine-tune catalyst efficiency. Advanced hyperparameter tuning ensures optimal algorithm performance, minimizing bias-variance trade-offs and improving regression accuracy in biodiesel yield predictions32,33. ML integration also enables real-time process optimization, linking sensor-based monitoring systems for continuous parameter adjustments. Ensemble learning techniques further improve biodiesel conversion accuracy, process reliability, and scalability for industrial applications34,35.

Despite extensive studies on biodiesel production from WCO, limited research has explored the synergistic use of biomass-derived heterogeneous catalysts particularly CaO synthesized from waste egg shells in conjunction with machine learning optimization techniques. Existing approaches often rely on conventional homogeneous catalysts (e.g., KOH, NaOH), which pose environmental and separation challenges. This study addresses the gap by synthesizing a sustainable CaO catalyst from biomass waste and applying advanced boosted machine learning algorithms (CatBoost, XGBoost, AdaBoost, GBM) to predict and optimize biodiesel yield. The models were rigorously cross-validated and assessed for overfitting and generalization performance, ensuring robust predictive accuracy. Furthermore, the produced biodiesel was tested in diesel engines, and its performance was benchmarked against biodiesel derived from homogeneous catalysts to evaluate environmental impact, fuel efficiency, and operational viability. This integrative approach represents a novel contribution by combining green catalyst synthesis, AI-driven process optimization, and real-world engine validation, paving the way for scalable and eco-friendly biodiesel production.

Materials and methodology

The Feedstock of biodiesel were collected from local restaurants, university hostels and hotels. The alcohol (methanol) and catalyst (KOH and NaOH) were procured from local scientific store.

Synthesis of egg-shell CaO catalyst

Egg shells, sourced from local restaurants, were thoroughly cleaned using distilled water to remove residual organic matter and contaminants. The washing process was conducted in multiple stages to ensure complete elimination of impurities. The shells were air-dried and subjected to a second rinse with distilled water to further boost purity. Following this, the cleaned shells were placed in a furnace at 60 °C for 12 h to moisture elimination and facilitate brittleness, which aids in efficient grinding.

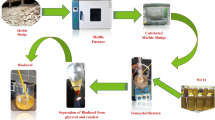

The dried egg shells underwent mechanical comminution using a planetary ball milling technique to obtain fine powder, ensuring uniform particle size distribution to promote greater surface exposure and catalytic efficiency of the final product. The powdered material was further exposed to a calcination process at 600 °C for 6 h, a crucial thermal treatment step to facilitate the decomposition of calcium carbonate (CaCO₃) into calcium oxide (CaO). Calcination at this temperature optimizes the crystalline structure of CaO, improving its reactivity and catalytic potential for transesterification reactions in biodiesel production23,36. The obtained CaO catalyst was sealed in an airtight container to inhibit external interference, which could lead to CaO hydration and reduce its catalytic performance. The synthesis process is visually summarized in the schematic shown in Fig. 1, illustrating each step from raw material preparation to final catalyst formation.

Procedure of biodiesel production

The transesterification of WCO was conducted using three different catalysts: egg-shell-derived CaO, KOH, and NaOH. Each catalyst was used separately in three distinct transesterification reactions, and the resulting biodiesel products were stored separately for comparative analysis. While the process parameters for KOH and NaOH were obtained from literature, machine learning optimization was applied exclusively to the CaO-catalyzed reaction to enhance biodiesel yield. The procedure begins with the pre-treatment of WCO, where the oil is filtered to separate undesired constituents and heated to eliminate moisture. Since the FFA content was high, an acid elimination treatment was performed using H₂SO₄ to reduce FFA levels before transesterification. In this step, a required amount of methanol and H₂SO₄ was added to the pre-treated WCO and stirred under controlled conditions at 70 °C. The reaction proceeded under elevated thermal conditions to enhance the translation of FFAs into methyl esters while minimizing soap formation. After completion, the mixture was neutralized and washed to remove excess acid and impurities37.

For each transesterification reaction, a required amount of methanol and catalyst was mixed with the esterified WCO in a reactor. The mixture was stirred continuously to ensure efficient mass transfer and reaction kinetics. To prevent methanol loss, all reactions were conducted in a closed system equipped with a reflux condenser, which effectively condensed methanol vapours and returned them to the reaction mixture38,39. In the transesterification process, triglycerides interact with methanol under catalytic conditions, resulting in the production of FAME and glycerol. After completion, the reaction mixture was allowed to settle, facilitating the separation of biodiesel from glycerol and residual impurities. The biodiesel phase was washed multiple times with warm water to remove contaminants, followed by drying to eliminate excess methanol. The final biodiesel product was characterized using analytical techniques to confirm purity and compliance with fuel standards. The schematic of the acid-catalyzed esterification and transesterification setup is shown in Fig. 2.

Background of boosted ML model

As an ensemble learning strategy, boosting enhances predictive performance by sequentially combining weak learners. Unlike traditional ensemble methods, boosting dynamically adjusts model weights based on misclassification rates, ensuring improved generalization and minimized bias over successive iterations. This approach allows for continuous refinement of predictions, making it particularly effective in complex, nonlinear datasets. In this research, four distinct boosting models XGBoost, AdaBoost, GBM, and CatBoost are employed to optimize biodiesel yield predictions. XGBoost is a highly efficient gradient boosting framework known for its scalability and regularization mechanisms,

preventing overfitting while delivering high-performance predictive modeling. AdaBoost sequentially improves weak classifiers by assigning greater weights to misclassified instances, thereby fine-tuning decision boundaries to enhance accuracy. GBM, another powerful gradient-based method, iteratively refines models through gradient descent optimization, effectively capturing intricate patterns within datasets while requiring careful hyperparameter tuning to maintain stability. CatBoost, specifically designed for categorical data, mitigates overfitting through ordered boosting and efficient handling of categorical features, making it particularly suitable for structured datasets with high cardinality variables. These models collectively improve prediction reliability by leveraging adaptive weighting mechanisms and sequential learning, ensuring robust and interpretable results in biodiesel optimization applications39,40,41. To contextualize the selection of boosted models in this study, we compared our approach with recent machine learning applications in biodiesel research. Table 1 summarizes key studies published that employed ML algorithms including ensemble methods for biodiesel yield prediction, engine performance modeling, and fuel optimization. The table outlines the algorithms used, dataset characteristics, validation strategies, and performance metrics. This comparative analysis highlights the growing preference for boosted models such as Ad boost, XGBoost, CatBoost, and GBM due to their superior accuracy, interpretability, and scalability. Our study builds upon these findings by integrating experimental data with advanced ML workflows, including hyperparameter tuning, k-fold validation, and residual diagnostics, to ensure robust and generalizable predictions. Also, the schematic flow diagram exposes the step-by-step work flow involved which was shown in Fig. 3.

Data collection

The data used for machine learning optimization were collected from trial-and-error experimental outputs. A total of 16 datasets were gathered, with 80% utilized for training and 20% for testing to run the model. The inputs included CC, MOR, and RT, while the output parameter was biodiesel yield. The collected data spanned the following ranges: CaO varied from 100 ppm to 300 ppm, MOR ranged from 4 to 12, and RT was between 60 and 140 min. These data points are represented using violin plot, as shown in Fig. 4.

To ensure robust reliability and adaptability before integrating the learning algorithm into real-time engineering applications, it underwent extensive validation using key performance metrics. These included the R², RMSE, MSE, and MAE. By applying these metrics across multiple learning models, the objective was to refine accuracy and establish a dependable predictive framework.

The selection of the most effective model was driven by a systematic validation process, involving continuous evaluation of prediction accuracy against the experimental dataset. Emphasis was placed on understanding the dynamic interactions between input constraints and output responses. Assessment of model precision was conducted via the validation metrics outlined below.

R2 =\(\:\:1-\frac{\sum\:{\left({y}_{i}-\widehat{{y}_{i}}\right)}^{2}\:}{\sum\:{\left({y}_{i}-\stackrel{-}{y}\right)}^{2}}\:\:\:\:\:\:\:\:\:\:\:\:\:\:\:\:\:\:\:\:\:\:\:\:\:\:\:\:\:\:\:\:\:\:\:\:\:\:\)

where:

\(\:{y}_{i}\)= True values

\(\:\widehat{{y}_{i}}\)= Anticipated values

\(\:\stackrel{-}{y}\) = Mean of true values

RMSE = \(\:\sqrt{\frac{1}{n}\sum\:{\left({y}_{i}-\widehat{{y}_{i}}\right)}^{2}}\:\:\:\:\:\:\:\:\:\:\:\:\:\:\:\:\:\:\:\:\:\:\:\:\:\:\:\:\:\:\:\:\:\:\:\)

MSE = \(\:\frac{1}{n}\sum\:{\left({y}_{i}-\widehat{{y}_{i}}\right)}^{2}\)

MAE = \(\:\frac{1}{n}\sum\:\left|{y}_{i}-\widehat{{y}_{i}}\right|\)

Data pre-processing

Prior to model training, the dataset underwent a series of pre-processing steps to ensure consistency, reliability, and optimal performance. The raw data, obtained from controlled transesterification experiments, was first subjected to rigorous cleaning procedures. This included the identification and removal of outliers, as well as verification of input-output relationships to maintain physical plausibility across all samples. The dataset was randomly shuffled before splitting into training and testing subsets to eliminate any ordering bias. Additionally, the distribution of key input parameters like MOR, CC, and RT was examined to confirm that the dataset was reasonably balanced across the experimental domain. This diversity in conditions helped improve the generalizability of the model.

Overview of hyper parameter tunning

To achieve superior performance in predictive modeling tasks, hyperparameter tuning was conducted using the Grid Search technique. This process was applied to all ensemble algorithms used in the study XGBoost, AdaBoost, Gradient Boosting Machine (GBM), and CatBoost. Grid Search systematically evaluates a predefined set of hyperparameter combinations to determine the configuration that maximizes model performance. The procedure begins by selecting the learning algorithm and defining a parameter grid, which includes a range of candidate values for each hyperparameter. These combinations are then exhaustively evaluated by training the model on the training dataset and assessing its performance using the coefficient of determination (R²) as the primary metric. The hyperparameter set that achieves the highest R² score is selected as the optimal configuration for each model. This tuning process ensures that the models are not only accurate but also generalizable across unseen data. The specific parameter ranges explored for each algorithm are summarized in Table 2, and the final selected values are discussed in the Results section.

Overview of cross validation

To assess the reliability and generalizability of the ML models, k-5 validation was employed. Conventional single-partition validation methods such as an 80:20 train-test split can introduce bias and increase the risk of overfitting, particularly when working with limited datasets. To mitigate these issues, this study adopted a 5-fold cross-validation strategy. In this approach, the dataset is split into five equally proportioned subsets. The model is trained and tested five times, with each fold serving once as the testing set while the remaining four folds are used for training. This iterative process, promoting balanced utilization of the dataset and reducing variance in performance estimates. The average R² score across the five folds provides a more robust and unbiased evaluation of model accuracy. This method is especially valuable in experimental studies with constrained sample sizes, where maximizing data efficiency is critical. A schematic illustration of the cross-validation workflow is provided in Fig. 5.

Experimental setup and protocols

The tests were conducted using an agriculture-based Kirloskar model TV1 diesel engine. The engine equipped with an air-fuel induction system, emission analyzers including a smoke meter and an AVL five-gas analyzer, an eddy current dynamometer, and temperature measurement panels. The engine has a stroke length of 112 mm, a bore diameter of 86.6 mm, and a compression ratio of 17:1. It delivers a power output of 5.2 kW and operates at a constant speed of 1500 rpm. The emission analyzer was connected to the exhaust tailpipe of the engine via a gas analyzer probe for precise monitoring, and all emission measurements were conducted in accordance with the ISO 8178 standard, as shown in Fig. 6.

Before initiating the engine experiments, a thorough inspection was conducted to verify the integrity of essential components, including checking for oil leaks, ensuring proper connections, and confirming adequate levels of coolant and lubricants. After completing the verification process, diesel fuel was initially supplied to operate the engine, allowing it to reach steady-state conditions. Once the engine stabilized under diesel operation, the fuel system was drained completely to eliminate residual effects before introducing the test fuels50,51. The trials were performed using various test fuels, and measurements were recorded under different loading conditions: idle, 25%, 50%, 75%, and full load. To ensure the reliability and repeatability of results, each fuel type was tested three times, and the recorded values were averaged for subsequent analysis and plotting. The averaged data points were used to evaluate performance indicators and exhaust emissions, ensuring robust and reproducible findings.

Uncertainty report

To enhance the accuracy and repeatability of experimental results, a comprehensive uncertainty analysis was conducted. This process is essential for identifying and minimizing potential sources of error that may affect the reliability of the final outcomes. During experimentation, various types of errors were encountered, including human error, instrumental limitations, environmental fluctuations, and other miscellaneous factors. By systematically evaluating these uncertainties, we aim to reduce measurement variability and improve the credibility of performance and emission data. The uncertainty values associated with key instruments and measured parameters are summarized in Table 3. The total uncertainty for each performance and emission parameter was calculated using.

= √ {(total performance metrics) 2+ (total emission metrics) 2}

= √ {(UCBTE) 2 + (UCBSEC) 2 + (UCCO) 2 + (UCNOx) 2+(UCSMOKE) 2}

=√ {(0.5) 2 + (0.7) 2 + (0.14) 2 + (0.7) 2 + (0.7) 2}

=±1.318

Results and discussions

Performance enhancement via hyperparameter tuning

Table 4 presents a comparative summary of default and optimized hyperparameter configurations for the four boosted learning models used in biodiesel yield prediction. Initially, all models shared default settings of n_estimators (ne) = 100, learning_rate (lr) = 0.1, and max_depth (md) = None, which remained unchanged for AdaBoost due to its limited tuneable parameters and stable performance. However, after systematic tuning, notable adjustments were made to the other models. For both XGBoost and GBM, the optimal configuration was identified as ne = 100, lr = 0.05, and md = 5. In contrast, CatBoost achieved its best performance with ne = 150, lr = 0.1, and md = 5.

Figure 7 illustrates the impact of hyperparameter optimization on model performance, measured by the coefficient of determination (R²). As expected, AdaBoost showed no change in R² values due to unchanged parameters. However, the other models demonstrated clear improvements. For XGBoost, R² increased from 0.79 to 0.82 following tuning, while GBM improved from 0.73 to 0.79. The most significant enhancement was observed in CatBoost, where R² rose from 0.92 to 0.95, confirming its superior predictive capability under optimized conditions.

ML model selection and validation

Four boosted learning models XGBoost, AdaBoost, GBM, and CatBoost were implemented to train and test the prediction of biodiesel oil yield using experimental data. Each model processed the dataset, learning patterns and relationships between the input variables and the corresponding yield. The goal was to determine the most accurate model for prediction. To assess performance, the predicted yield from each model was compared against the actual experimental yield. A graphical representation, shown in Fig. 8, illustrates this comparison.

The representation includes a fit line (blue line), training set (yellow dots), and testing set (green dots) to assess the most accurate model for predicting and validating the experimental outputs. Among all models, the CatBoost model exhibited the strongest relationship with the experimental output, showing a high degree of similarity to the actual results. Compared to other learning models, CatBoost’s training and testing sets had minimal deviations from each other and closely aligned with the fit line. In contrast, the remaining models including AdaBoost, XGBoost, and GBM displayed a perfect alignment between the training set and the fit line, following almost the same trend. However, the testing points showed greater deviations, indicating that these models did not accurately predict the experimental output trends. The accuracy of each model was confirmed using evaluation metrics, including R², RMSE, MSE, and MAE. A model with a high R² and low error values was considered more accurate for assessing the experimental data. The evaluation metrics also confirmed that the CatBoost learning model was the best choice for future assessments, based on its performance indicators (R² = 0.9554, RMSE = 0.83, MSE = 0.68, MAE = 0.52). This was presented in the Fig. 9. From the figure, it was observed that, except for CatBoost, the remaining models had R² values ranging from 0.791 to 0.820. CatBoost demonstrated a significantly higher R² 20–22% greater than the other models.

Outcome of cross validation (K-fold)

A comprehensive k-fold analysis was performed to assess the reliability and generalization capability of the boosted learning models. Each algorithm contributed five R² values across five folds, resulting in a total of 20 performance scores. These values were averaged to compute the mean R² for each model, as summarized in Table 5. The results indicate that the CatBoost algorithm consistently achieved the highest average R² among all models, demonstrating its superior predictive accuracy and robustness. Its ability to maintain strong performance across multiple fold iterations highlights its effectiveness in modeling biodiesel yield under varying training conditions. The cross-validation procedure further validates CatBoost’s stability and reliability, making it a suitable choice for structured experimental datasets with limited sample sizes.

Overfitting assessment for best model

Residual plots serve as essential diagnostic tools for assessing the performance and generalization capability of ML models. By plotting the residuals distinct as the difference between experimental and predicted values against the predicted outputs, these plots reveal whether the model captures the underlying data distribution without systematic bias. For a well-fitted model, residuals are expected to be evenly distributed about the horizontal axis at zero, reflecting the absence of systematic error. In the context of overfitting assessment, key indicators include disproportionate clustering of training residuals compared to the test set, or visible trends in residual dispersion. Overfitting is typically suggested when the model performs exceptionally well on training data but exhibits high variance or poor accuracy on unseen test data. As illustrated in Fig. 10, the residual plot for the CatBoost model demonstrates a well-balanced and tightly clustered distribution of residuals for both training (blue) and testing (green) datasets. The residuals are concentrated near the zero line, with no apparent heteroscedasticity or systematic deviation. This uniformity across both data partitions confirms that the CatBoost model achieves high predictive accuracy while maintaining generalization capability. The absence of large residuals or directional patterns further supports the conclusion that the model avoids overfitting and performs reliably under varying training conditions.

Model interpretation

Model interpretation is essential for understanding the impact of different input features on predictions. Conducting feature importance analysis helps identify the most influential variables, guiding future model improvements and decision-making. Additionally, partial dependence analysis provides insights into how specific features affect model predictions, ensuring transparency and reliability in machine learning applications52,53. Figure 11 illustrate the feature importance scores and partial dependence trends for the best-performing learning model.

Figure 11a reveals the feature importance scores for the CatBoost model, indicating that MOR holds the highest importance in oil yield prediction, with a magnitude coefficient approaching 50. This suggests that MOR has a substantial impact on biodiesel yield optimization. Catalyst concentration emerges as the second most impactful variable, exhibiting an importance score close to 35, further reinforcing its critical role in biodiesel yield improvement. These insights highlight that both variables significantly contribute to optimizing biodiesel production efficiency.

Partial dependence analysis offers enhanced insight how input features influence the model’s predictions. The trend analysis indicates that CC consistently augments biodiesel yield as its CC increases. However, beyond a certain threshold, a diminishing return effect is observed. MOR exhibits an increasing trend in yield generation up to a value of 9, after which its impact reverses, leading to a decrease in yield. This suggests an optimal range for MOR that must be maintained for maximum efficiency. Reaction time follows a similar trend to MOR, Exhibiting a positive association with biodiesel up to 100 min. A diminishing trend in yield is observed beyond this threshold, indicating a potential oversaturation or unwanted side reactions affecting the process which was represented in Fig. 11b. These findings emphasize the necessity of determining optimal operating conditions for biodiesel production while considering both feature interactions and diminishing returns. The combination of feature importance and partial dependence analysis provides a comprehensive framework for refining model predictions and enhancing process efficiency.

Process parameter optimization for biodiesel production

To maximize oil yield in biodiesel production, process parameters were optimized using the CatBoost learning model, selected as the best predictive tool based on evaluation metrics, including R2, RMSE, MSE, and MAE, as well as comparisons with experimental results. The CatBoost model was trained using experimental biodiesel yield data, where CC, MOR, and RT served as input features. The model was validated to ensure predictive accuracy, and feature importance examination was conducted to assess the relative impact of each parameter on oil yield.

The optimization process involved systematically varying one parameter while keeping the others constant, enabling an isolated assessment of its effect. As illustrated in Fig. 8, the optimization results highlight the influence of these parameters on biodiesel yield using a 2D representation. The final optimized values 80 min reaction time, 9:1 MOR, and 3 wt% catalyst concentration were identified based on the highest predicted yield, consistent with experimental validation. These optimized parameters are summarized in Table 6.

In Fig. 12a, the reaction time was varied while CC and MOR remained constant. The scrutiny determined that the optimal RT for attaining extreme oil yield was 80 min, resulting in a yield of 95.083%. Oil yield progressively increased from 60 min, reaching its peak at 80 min. However, beyond 120 min, the yield declined, suggesting an upper threshold where excessive reaction time negatively impacts reaction kinetics. This decline indicates that prolonged exposure may lead to adverse thermal effects or side reactions, reducing biodiesel conversion efficiency. Optimizing reaction time is crucial to maximizing yield while preventing unnecessary degradation or secondary reactions.

Similarly, Fig. 12b presents the effect of MOR variation, while CC and RT were kept constant. The results showed that the optimal MOR for achieving maximum oil yield was 9:1, yielding 95.083%. The oil yield increased steadily from 6:1, reaching its peak at 9:1, after which further increases in MOR resulted in a decline. This decline suggests that excessive methanol may disrupt the reaction equilibrium, leading to inefficient transesterification or unwanted side reactions. Maintaining the optimal MOR is essential for ensuring complete conversion while avoiding excess methanol, which could increase purification costs and reduce process efficiency. These findings emphasize the importance of precise MOR control in biodiesel production.

Finally, Fig. 12c illustrates the effect of catalyst concentration variation while keeping RT and MOR constant. The analysis revealed that the optimal catalyst concentration for maximum oil yield was 3 wt%, yielding 95.083%. Oil yield steadily increased from 1 wt%, peaking at 3 wt%, before declining at higher concentrations. This decline suggests that excessive catalyst may lead to unwanted side reactions, soap formation, or mass transfer limitations, negatively affecting biodiesel production efficiency. Maintaining the correct catalyst concentration is crucial for achieving high yield while preventing excess catalyst usage, which could complicate purification steps and increase production costs. These results highlight the importance of optimizing catalyst concentration to ensure efficient transesterification and maximum biodiesel yield which was presented in Table 6.

Yield assessment and error calculation in biodiesel production

The production of biodiesel using a CaO-based catalyst and WCO was conducted with 1000 mL of pretreated WCO under optimized process conditions. The process parameters included a MOR of 6:1, a RT of 80 °C, and a CC of 151 ppm. To determine the necessary methanol volume, calculations were based on the molar mass of triglycerides and methanol. With an estimated oil density of 0.91 g/mL, the total oil mass is 910 g, corresponding to 1.034 moles of triglycerides. Applying the 6:1 molar ratio, this equates to 6.204 moles of methanol. Given methanol’s density of 0.791 g/mL and molar mass of 32 g/mol, the required methanol volume is 251 mL. The catalyst concentration of 151 ppm translates to 137.41 mg for this oil quantity.

The biodiesel production process begins by heating the pretreated oil to 80 °C in a reactor equipped with stirring. Methanol (251 mL) is gradually added, followed by the CaO catalyst (137.41 mg), ensuring thorough mixing. The reaction is maintained under constant agitation for 2–3 h, allowing complete transesterification. After completion, the mixture is left to settle for 6–12 h, during which biodiesel separates from the glycerol layer. Washing the biodiesel with warm water removes residual methanol and catalyst impurities, followed by mild heating or vacuum drying to ensure purity. Once the biodiesel was purified, the final yield was measured to verify process efficiency. Based on a predicted 95.38% yield, the expected biodiesel volume is 1000 mL × 95.38% = 953.8 mL. However, the actual yield obtained was 945 mL, resulting in a discrepancy of 8.8 mL. The percentage error is calculated as follows:

Percentage Error = [(Predicted Yield – Actual Yield) / Predicted Yield] ×100

= [(953.8–945) / 953.8] × 100

≈ 0.92% error

For biodiesel production using NaOH and KOH catalysts, a RT of 60 °C, a 6:1 MOR, and 10 g of catalyst were used. This process yielded 950 to 960 mL of biodiesel.

Yield comparisons among the different catalyst

A comparison of biodiesel yield using CaO-based catalysts and conventional KOH and NaOH catalysts provides insight into efficiency and sustainability. Literature suggests that biodiesel conversion using KOH and NaOH, as homogeneous catalysts, typically achieves yields exceeding 95%, depending on reaction conditions. For example, biodiesel conversion using KOH at 60 °C, a 6:1 MOR, and 1 g KOH per 100 mL of feedstock resulted in a 95% yield, while further optimization with 0.8 g KOH at 55 °C increased the yield to 96%54,55,56. Studies on used frying oils reported biodiesel yields of 92–96% using NaOH and KOH, with variations in reaction time and catalyst concentration. Research on vegetable oil-based biodiesel found that KOH catalysts generally provide higher yields than NaOH, with KOH achieving up to 97% yield, while NaOH yielded slightly lower values55,57.

In contrast, the CaO-based catalyst achieved a yield of 945 mL from 1000 mL of oil, corresponding to 94.5%, which is slightly lower than the optimized KOH-based biodiesel yields but remains highly efficient. The 0.92% error in yield calculation suggests minor losses due to reaction kinetics, catalyst dispersion, or purification steps. While KOH and NaOH catalysts provide high biodiesel conversion rates, they present significant challenges, particularly soap formation due to saponification, which complicates downstream purification. This issue necessitates additional processing steps, increases material loss, and adds to overall production costs, making the purification phase more labor-intensive and less sustainable. In contrast, CaO-based catalysts, despite achieving yields comparable to or slightly lower than conventional catalysts, offer distinct advantages that justify their application in biodiesel production.

Being heterogeneous, CaO catalysts allow for straightforward separation, eliminating the need for excessive washing steps and reducing unwanted chemical byproducts. Their recyclability enables multiple reaction cycles, minimizing waste generation and lowering overall catalyst consumption. Additionally, CaO-derived catalysts contribute to greater environmental sustainability, as they avoid the harsh chemical interactions that NaOH and KOH undergo in liquid-phase transesterification. The long-term benefits of CaO catalysts including efficiency in process handling, reduced purification requirements, and lower environmental impact position them as a compelling alternative for biodiesel synthesis, even if yield figures are marginally lower than conventional alkaline catalysts58,59,60. After storing the biodiesel in a proper container, it underwent thermos-physical property analysis, and the results were tabulated in Table 7. The property analysis was conducted in accordance with ASTM standards.

Engine outcomes

Figure 13 presents the Brake Thermal Efficiency (BTE) output across various load states for different test fuels, including diesel, CaO biodiesel, KOH biodiesel, and NaOH biodiesel. The trend specifies that BTE increases with rising engine load due to better fuel atomization and amended air-fuel mixing, leading to higher combustion efficiency61. At higher loads, diesel exhibited the highest BTE at 31.89%, followed by CaO biodiesel at 28.06%, KOH biodiesel at 27.16%, and NaOH biodiesel at 26.02%. The superior BTE of diesel is attributed to its higher CV and lower viscosity, which enhance combustion efficiency and energy conversion. Among the biodiesel variants, CaO biodiesel demonstrated the highest BTE among biodiesel fuels, showing a 2.8% reduction compared to diesel. This is due to its higher CN and oxidative stability, which promote more complete combustion. KOH biodiesel exhibited a 5.8% reduction in BTE compared to diesel, indicating slightly lower combustion efficiency due to elevated viscosity and lower cetane number. NaOH biodiesel showed the lowest BTE, with an 6.4% reduction compared to diesel, confirming its higher viscosity and lower CV, which negatively impact fuel atomization and combustion efficiency. Overall, while biodiesel blends exhibit slightly lower BTE than diesel, their renewable nature and lower emissions make them promising alternatives for sustainable diesel engine applications. CaO biodiesel remains the most efficient biodiesel option, because closer BTE with diesel than other test cases.

Figure 14 presents the BSEC output across various load states for different test fuels, including diesel, CaO biodiesel, KOH biodiesel, and NaOH biodiesel. The trend shows that BSEC decreases as engine load increases for all test fuels due to improved combustion efficiency and better energy utilization per unit of fuel62. At higher loads, diesel exhibited the lowest BSEC at 10.25 MJ/kWh, confirming its superior calorific value and atomization characteristics. Among the biodiesel variants, CaO biodiesel demonstrated the lowest BSEC at 14.71 MJ/kWh, indicating better energy utilization compared to KOH biodiesel (17.39 MJ/kWh) and NaOH biodiesel (18.79 MJ/kWh). This advantage is attributed to CaO biodiesel’s higher cetane number and oxidative stability, promoting more complete combustion. The percentage increase in BSEC compared to diesel at higher loads further highlights efficiency differences. CaO biodiesel shows a 4.31% increase, making it the most efficient biodiesel option. In comparison, KOH biodiesel exhibits a 6.97% increase, demonstrating higher fuel consumption due to viscosity-related atomization issues. NaOH biodiesel shows the highest BSEC increase, reaching 8.33%, confirming its poorer atomization and greater fuel consumption under high-load conditions. Overall, while biodiesel fuels exhibit slightly higher BSEC than diesel at peak loads, among which CaO biodiesel remains the most efficient biodiesel option, because closer BSEC with diesel than other test cases.

Figure 15 presents the carbon monoxide (CO) emissions across various load states for different test fuels, including diesel, CaO biodiesel, KOH biodiesel, and NaOH biodiesel. The trend shows that CO emissions decrease as engine load increases for all test fuels. This is because higher loads improve combustion efficiency, leading to more complete oxidation of fuel and reducing CO formation63,64. At higher loads, diesel exhibited the highest CO emissions at 3.02 g/kWh, primarily due to incomplete combustion and lower oxygen content in the fuel. Among the biodiesel variants, CaO biodiesel demonstrated the lowest CO emissions at 2.22 g/kWh, indicating better oxygen availability and improved combustion efficiency compared to KOH biodiesel (2.71 g/kWh) and NaOH biodiesel (2.89 g/kWh). The percentage reduction in CO emissions compared to diesel at higher loads further highlights the advantages of biodiesel fuels. CaO biodiesel shows a 26.5% reduction, making it the cleanest-burning biodiesel option. In comparison, KOH biodiesel exhibits a 10.3% reduction, while NaOH biodiesel shows a 4.3% reduction, confirming its slightly poorer combustion efficiency due to elevated viscosity and lower atomization quality. Overall, CaO biodiesel blend significantly diminishes CO emissions associated to diesel.

Figure 16 presents the NOx emissions across various load states for different test fuels, including diesel, CaO biodiesel, KOH biodiesel, and NaOH biodiesel. The trend shows that NOx increases as engine load increases. This is primarily due to peak combustion temperatures at elevated loads, which promote thermal NOx65,66. At higher loads, diesel exhibited the lowest NOx emissions at 8.21 g/kWh, while CaO biodiesel recorded 10.2 g/kWh, followed by KOH biodiesel at 11.9 g/kWh, and NaOH biodiesel at 12.35 g/kWh. The increase in NOx emissions for biodiesel blends is attributed to their higher O2, which accelerating NOx. The percentage rise in NOx than diesel at higher loads further highlights the impact of biodiesel combustion characteristics. CaO biodiesel shows a 24.2% increase, making it the least NOx-intensive biodiesel option. In comparison, KOH biodiesel exhibits a 45.0% increase, while NaOH biodiesel shows the highest NOx increase at 50.5%, confirming its higher combustion temperature and oxygen content. Overall, CaO biodiesel blend chosen was best option for lower NOx intensity.

Figure 17 presents the smoke emissions across various load states for different test fuels, including diesel, CaO biodiesel, KOH biodiesel, and NaOH biodiesel. The trend indicates that smoke emissions increase with rising engine load due to increased rate of fuel injection, leading to increased particulate matter formation67,68,69. At higher loads, diesel exhibited the highest smoke emissions at 51.5%, while CaO biodiesel recorded 44.5%, KOH biodiesel at 42.01%, and NaOH biodiesel at 41.67%. The reduction in smoke for biodiesel blends than diesel is primarily due to their higher O2, which promotes more complete combustion and diminishes soot formation. Among the biodiesel variants, CaO biodiesel showed a 13.6% reduction in smoke emissions compared to diesel, indicating moderate particulate matter reduction. KOH biodiesel exhibited an 18.5% reduction, demonstrating better atomization characteristics, while NaOH biodiesel showed the highest smoke reduction at 19.1%, confirming improved oxygen-enhanced combustion efficiency and better fuel-air mixing. The higher smoke emissions of diesel compared to biodiesel blends can be attributed to its lower oxygen availability, leading to fuel-rich zones and increased soot formation. In contrast, NaOH biodiesel, with superior oxygen content and improved spray characteristics, exhibited the lowest smoke emissions among all test fuels. Overall, while diesel produces the highest smoke emissions, biodiesel blends provide significant reductions, with NaOH biodiesel offering the most effective soot reduction, followed by KOH and CaO biodiesel. This demonstrates the role of fuel oxygenation and viscosity in controlling particulate emissions, making biodiesel a promising alternative for reducing smoke in diesel engine applications.

Practical implications and future directions

The discoveries of this study present several practical implications for industrial application and future research in sustainable biofuel systems. The successful use of biomass-derived CaO catalysts highlights a resource-efficient and environmentally conscious method for producing biodiesel, particularly suitable for decentralized and rural settings where agricultural waste is abundant. The optimized biodiesel blends, validated through engine performance and emission testing, demonstrate compatibility with existing diesel engines, offering a pathway to reduce emissions without requiring significant engine modifications. Furthermore, the integration of ML models such as CatBoost and XGBoost Offers a comprehensive structure for predictive modeling and process optimization. These models can be embedded into industrial control systems to enable real-time monitoring, fault detection, and adaptive tuning, thereby improving operational efficiency and reducing downtime. Future research should focus on catalyst regeneration and long-term stability across multiple reaction cycles, as well as conducting comprehensive lifecycle assessments to evaluate environmental and economic impacts. The development of hybrid ML frameworks that combine data-driven models with physics-based simulations could enhance prediction accuracy and deepen understanding of reaction kinetics and engine thermodynamics. Additionally, pilot-scale trials and techno-economic scrutinizes are vital to assess the scalability and market competitiveness of the proposed biodiesel production route. Finally, the outcomes of this study align with policy goals aimed at decarbonizing the transport and agricultural sectors, and collaboration with regulatory bodies could facilitate certification and broader deployment of biofuel technologies.

Conclusion

-

This study demonstrates the effective integration of ML techniques with experimental biodiesel synthesis, offering a reliable framework for optimizing yield and evaluating engine performance. Among the boosted learning models evaluated, CatBoost exhibited superior predictive accuracy (R2 = 0.955) and minimal error metrics, confirming its robustness for biodiesel process modeling. Feature importance and partial dependence analyses revealed that MOR and CC were the most influential parameters, enabling precise process adjustments. Under optimized conditions MOR of 9:1, CC of 3 wt%, and RT of 80 min a maximum biodiesel yield of 95.083% was achieved, with CatBoost accurately predicting these outcomes. Although CaO-based catalysts produced slightly lower yields than NaOH and KOH, they offer significant advantages in sustainability, recyclability, and ease of separation, positioning them as promising alternatives for scalable biodiesel production.

-

Engine performance testing further confirmed the viability of CaO biodiesel, which demonstrated reduced CO and smoke emissions compared to diesel, despite a moderate increase in NOx. BTE for CaO biodiesel reached 28.06%, while BSEC increased by 43.5%, indicating a trade-off between combustion efficiency and emissions control. However, the overall cleaner-burning profile reinforces its potential for sustainable diesel engine applications.

-

Despite these encouraging results, the study is limited by the use of a single-cylinder engine, a relatively small dataset, and the absence of long-term catalyst durability assessments. These constraints may affect the generalizability and industrial readiness of the findings. To discourse these gaps, future research should focus on field-scale validation of CaO biodiesel in multi-cylinder engines under variable load conditions, the application of deep learning models for multi-objective optimization, and comprehensive techno-economic and lifecycle analyses to evaluate scalability and environmental impact. These efforts will be essential to transition biodiesel technologies from laboratory success to real-world deployment.

Data availability

Relevant data are accessible through the corresponding authors, subject to reasonable academic inquiry.

References

Munimathan, A. et al. ML techniques increasing the power factor of a compression ignition engine that is powered by Annona biodiesel using SATACOM. Sci. Rep. 15 (1). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-91162-1 (2025).

Bora, A., Gupta, D. & Durbha, K. Sewage sludge to bio-fuel: A review on the sustainable approach of transforming sewage waste to alternative fuel. Fuel 259, 116262. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.fuel.2019.116262 (2020).

Lee, S. et al. Waste to bioenergy: a review on the recent conversion technologies. BMC Energy. 1, 1–22. https://doi.org/10.1186/S42500-019-0004-7 (2019).

Janaki, D. V., Ranjit, P. S. & Balakrishna, B. Impact of magnesium oxide nanoparticles and hydrogen enrichment on CI engine performance with Mahua oil biodiesel using machine learning. Heat Mass Transf. 61 (8). https://doi.org/10.1007/s00231-025-03610-3 (2025).

Anbazhaghan, N. et al. A review of combustion geometry profiles in biodiesel-fueled compression ignition engines: technical insights into combustion, performance, and emission characteristics. Discover Appl. Sci. 7 (6). https://doi.org/10.1007/s42452-025-07219-3 (2025).

Ramalingam, K. et al. Substitution of diesel fuel in conventional compression ignition engine with waste biomass-based fuel and its validation using artificial neural networks. Process Saf. Environ. Prot. 177, 1234–1248 (2023).

Krishnamoorthy, R., Asaithambi, K., Balasubramanian, D., Murugesan, P. & Rajarajan, A. Effect of Cobalt chromite on the investigation of traditional CI engine powered with Raw Citronella fuel for the future sustainable renewable source. SAE Int. J. Adv. Curr. Practices Mobil. 3 (2020-28-0445), 843–850 (2020).

Sarno, M. & Iuliano, M. Biodiesel production from waste cooking oil. Green. Process. Synthesis. 8, 828–836. https://doi.org/10.1515/gps-2019-0053 (2019).

Wang, B., Wang, B., Shukla, S. & Wang, R. Enabling catalysts for biodiesel production via transesterification. Catalysts https://doi.org/10.3390/catal13040740 (2023).

Amini, Z., Ilham, Z., Ong, H., Mazaheri, H. & Chen, W. State of the Art and prospective of lipase-catalyzed transesterification reaction for biodiesel production. Energy. Conv. Manag. 141, 339–353. https://doi.org/10.1016/J.ENCONMAN.2016.09.049 (2017).

Liu, X. et al. Current application of MOFs based heterogeneous catalysts in catalyzing transesterification/esterification for biodiesel production: A review. Energy. Conv. Manag. 229, 113760. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.enconman.2020.113760 (2021).

Shan, R., Lu, L., Shi, Y., Yuan, H. & Shi, J. Catalysts from renewable resources for biodiesel production. Energy. Conv. Manag. https://doi.org/10.1016/J.ENCONMAN.2018.10.032 (2018).

Zhang, J. et al. Importance of species heterogeneity in supported metal catalysts. J. Am. Chem. Soc. https://doi.org/10.1021/jacs.2c00202 (2022).

Zhu, C. et al. Heterogeneous Fe-Co dual-atom catalyst outdistances the homogeneous counterpart for peroxymonosulfate-assisted water decontamination: new surface collision oxidation path and diatomic synergy. Water Res. 241, 120164. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.watres.2023.120164 (2023).

Ching-Velasquez, J. et al. Production and characterization of biodiesel from oil of fish waste by enzymatic catalysis. Renew. Energy. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.renene.2020.02.100 (2020).

Moazeni, F., Chen, Y. & Zhang, G. Enzymatic transesterification for biodiesel production from used cooking oil, a review. J. Clean. Prod. https://doi.org/10.1016/J.JCLEPRO.2019.01.181 (2019).

Ahmad, S., Chaudhary, S., Pathak, V., Kothari, R. & Tyagi, V. Optimization of direct transesterification of chlorella pyrenoidosa catalyzed by waste egg shell based heterogenous nano – CaO catalyst. Renew. Energy. 160, 86–97. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.renene.2020.06.010 (2020).

Parandi, E. et al. Optimization of microreactor-intensified transesterification reaction of Sesame cake oil (sesame waste) for biodiesel production using magnetically immobilized lipase nano-biocatalyst. Energy. Conv. Manag. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.enconman.2023.117616 (2023).

Dwivedi, G. et al. Impact analysis of biodiesel production parameters for different catalyst. Environ. Dev. Sustain. 1–21. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10668-021-02073-w (2022).

Sarkar, A. et al. Parkia speciosa: A basic heterogeneous catalyst for production of soybean oil-based biodiesel. Fuel https://doi.org/10.1016/j.fuel.2023.128537 (2023).

Quevedo-Amador, R., Reynel-Ávila, H., Mendoza-Castillo, D., Badawi, M. & Bonilla-Petriciolet, A. Functionalized hydrochar-based catalysts for biodiesel production via oil transesterification: optimum Preparation conditions and performance assessment. Fuel https://doi.org/10.1016/j.fuel.2021.122731 (2022).

Rahman, W. et al. Biodiesel synthesis from Eucalyptus oil by utilizing waste egg shell derived calcium based metal oxide catalyst. Process Saf. Environ. Prot. https://doi.org/10.1016/J.PSEP.2018.12.015 (2019).

Erchamo, Y., Mamo, T., Workneh, G. & Mekonnen, Y. Improved biodiesel production from waste cooking oil with mixed methanol–ethanol using enhanced eggshell-derived CaO nano-catalyst. Sci. Rep. 11 https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-021-86062-z (2021).

Gil, A. Challenges on Waste-to-energy for the valorization of industrial wastes: electricity, heat and cold, bioliquids and biofuels. Environ. Nanatechnol. Monit. Manage. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.enmm.2021.100615 (2021).

Iwuozor, K. et al. Valorization of sugar industry’s By-products: A perspective. Sugar Tech. 24, 1052–1078. https://doi.org/10.1007/s12355-022-01143-1 (2022).

Wang, J. et al. Double Unit-Cell silicogermanate nanosheets developed by Salting-Out mechanism for biomass conversion. J. Am. Chem. Soc. https://doi.org/10.1021/jacs.4c03732 (2024).

Sudarsanam, P., Peeters, E., Makshina, E., Pârvulescu, V. & Sels, B. Advances in porous and nanoscale catalysts for viable biomass conversion. Chem. Soc. Rev. 48 8, 2366–2421. https://doi.org/10.1039/c8cs00452h (2019).

Pali, H., Sharma, A., Kumar, N. & Singh, Y. Biodiesel yield and properties optimization from Kusum oil by RSM. Fuel 291, pp120218. https://doi.org/10.1016/J.FUEL.2021.120218 (2021).

Ganesha, T. et al. Biodiesel yield optimization from ternary (animal fat-cotton seed and rice bran) oils using response surface methodology and grey Wolf optimizer. Ind. Crops Prod. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.indcrop.2023.117569 (2023).

Ahmad, A., Yadav, A. K. & Singh, A. Application of machine learning and genetic algorithms to the prediction and optimization of biodiesel yield from waste cooking oil. Korean J. Chem. Eng. 40 (12), 2941–2956 (2023).

Ahmad, A., Yadav, A. K., Singh, A. & Singh, D. K. A machine learning-response surface optimization approach to enhance the performance of diesel engine using novel blends of Aloe Vera biodiesel with MWCNT nanoparticles and hydrogen. Process Saf. Environ. Prot. 186, 738–755 (2024).

Pasha, M., Dai, L., Liu, D., Du, W. & Guo, M. A hybrid soft sensor framework for Real-Time biodiesel yield prediction: integrating mechanistic models and machine learning algorithms. Renew. Energy. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.renene.2024.121888 (2024).

Bukkarapu, K. & Krishnasamy, A. Investigations on the applicability of machine learning algorithms to optimize biodiesel composition for improved engine fuel properties. Int. J. Engine Res. 25, 1299–1314. https://doi.org/10.1177/14680874241227540 (2024).

Ahmad, A., Yadav, A., Singh, A. & Singh, D. A machine learning–genetic algorithm based models for optimization of intensification process through microwave reactor: A new approach for rapid and sustainable synthesis of biodiesel from novel Hiptage benghalensis seed oil. Fuel https://doi.org/10.1016/j.fuel.2024.132470 (2024).

Dubey, A., Prasad, R. S., Singh, J. K. & Nayyar, A. Optimization of diesel engine performance and emissions with biodiesel-diesel blends and EGR using response surface methodology (RSM). Clean. Eng. Technol. 8 100509. (2022).

Osagiede, C. & Aisien, F. Biochar-based bi-functional catalyst derived from rubber seed shell and eggshell for biodiesel production from waste cooking oil. Fuel https://doi.org/10.1016/j.fuel.2023.130076 (2024).

Dubey, A., Prasad, R. S. & Singh, J. K. An analytical and economical assessment of the waste cooking oil based biodiesel using optimized conditions on the process variables. Energy Sour. Part A Recover. Utilization Environ. Eff. 47 (1), 1997–2012 (2025).

Kumar, S. et al. Production of Methyl esters from waste cooking oil and chicken fat oil via simultaneous esterification and transesterification using acid catalyst. Energy. Conv. Manag. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.enconman.2020.113366 (2020).

Kamal, W. et al. Development of multiple machine-learning computational techniques for optimization of heterogenous catalytic biodiesel production from waste vegetable oil. Arab. J. Chem. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.arabjc.2022.103843 (2022).

Zhao, C. et al. Improving the performance of microbial fuel cell stacks via capacitive-hydrogel bioanodes. Int. J. Hydrog. Energy. 97, 708–717 (2025).

Fu, L. A novel robust control for disturbed uncertain microbial fuel cell with noisy output. J. New. Mater. Electrochem. Syst. 28 (1). (2025).

Sanjeevannavar, M. B. et al. Machine learning prediction and optimization of performance and emissions characteristics of IC engine. Sustainability 15 (18), 13825. (2023).

Siqueira-Filho, E. A., Lira, M. F. A., Converti, A., Siqueira, H. V. & Bastos-Filho, C. J. Predicting thermoelectric power plants diesel/heavy fuel oil engine fuel consumption using univariate forecasting and XGBoost machine learning models. Energies 16 (7), 2942. (2023).

Kardani, N., Marzbali, H., Shah, M., Zhou, A. & K. and Machine learning prediction of the conversion of lignocellulosic biomass during hydrothermal carbonization. Biofuels 13 (6), 703–715 (2022).

Chen, X. et al. Enhanced bio-oil production from biomass catalytic pyrolysis using machine learning. Renew. Sustain. Energy Rev. 209 115099. (2025).

Jin, X. et al. Investigation and optimization of biodiesel production based on multiple machine learning technologies. Fuel 348 128546. (2023).

Yahya, I., Gassoumi, M., Attia, M. & Ennetta, R. Application of AI and machine learning techniques to improve microwave-assisted biodiesel yield prediction. Biomass Bioenergy 202 108250. (2025).

Almohana, A. I. et al. Theoretical investigation on optimization of biodiesel production using waste cooking oil: machine learning modeling and experimental validation. Energy Rep. 8, 11938–11951 (2022).

Sumayli, A. Development of advanced machine learning models for optimization of Methyl ester biofuel production from Papaya oil: Gaussian process regression (GPR), multilayer perceptron (MLP), and K-nearest neighbor (KNN) regression models. Arab. J. Chem. 16 (7), 104833 (2023).

Ramalingam, K. et al. An experimental and ANN analysis of ammonia energy integration in biofuel powered low-temperature combustion engine to enhance cleaner combustion. Case Stud. Thermal Eng. 63 105284. (2024).

Vellaiyan, S. et al. Maximizing waste plastic oil yield and enhancing energy and environmental metrics through pyrolysis process optimization and fuel modification. Res. Eng. 22 102066. (2024).

Brenning, A. Interpreting machine-learning models in transformed feature space with an application to remote-sensing classification. Mach. Learn. 112, 3455–3471. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10994-023-06327-8 (2021).

Molnar, C., Konig, G., Bischl, B. & Casalicchio, G. Model-agnostic feature importance and effects with dependent features - A conditional subgroup approach. Data Min. Knowl. Discov. 38, 2903–2941. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10618-022-00901-9 (2020).

Noiroj, K., Intarapong, P., Luengnaruemitchai, A. & Jai-In, S. A comparative study of KOH/Al2O3 and koh/nay catalysts for biodiesel production via transesterification from palm oil. Renew. Energy. 34, 1145–1150. https://doi.org/10.1016/J.RENENE.2008.06.015 (2009).

Cercado, A., Ballesteros, F. & Capareda, S. Biodiesel from three microalgae transesterification processes using different homogenous catalysts. Int. J. Technol. https://doi.org/10.14716/IJTECH.V9I4.1145 (2018).

Dias, J., Alvim-Ferraz, M. & Almeida, M. Comparison of the performance of different homogeneous alkali catalysts during transesterification of waste and Virgin oils and evaluation of biodiesel quality. Fuel 87, 3572–3578. https://doi.org/10.1016/J.FUEL.2008.06.014 (2008).

Ramirez, J., Buestán, L., López-Maldonado, E. & Pinos-Vélez, V. Preparation and physicochemical characterization of biodiesel from recycled vegetable oil in cuenca, Ecuador by transesterification catalyzed by KOH and NaOH. Eng https://doi.org/10.3390/eng4010056 (2023).

Chong, N. et al. Preparation and characterization of Shell-Based CaO catalysts for Ultrasonication-Assisted production of biodiesel to reduce toxicants in diesel generator emissions. Energies https://doi.org/10.3390/en16145408 (2023).

Li, H. et al. A novel magnetic CaO-based catalyst synthesis and characterization: enhancing the catalytic activity and stability of CaO for biodiesel production. Chem. Eng. J. 391, 123549. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.cej.2019.123549 (2020).

Huang, J. et al. Fabrication of Hollow cage-like CaO catalyst for the enhanced biodiesel production via transesterification of soybean oil and methanol. Fuel 290, 119799. https://doi.org/10.1016/J.FUEL.2020.119799 (2021).

Aydın, M., Uslu, S. & Çelik, B. Performance and emission prediction of a compression ignition engine fueled with biodiesel-diesel blends: A combined application of ANN and RSM based optimization. Fuel 269, 117472. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.fuel.2020.117472 (2020).

Rai, R. & Sahoo, R. Diesel engine operational and emissions attributes optimization through Taguchi–Grey experiment design: exploring the impact of Al2O3–CNT impregnated orange Peel biodiesel–diesel blend fuel. J. Therm. Anal. Calorim. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10973-024-13081-z (2024).

Hasan, A. et al. An experimental study of engine characteristics and tailpipe emissions from modern DI diesel engine fuelled with methanol/diesel blends. Fuel Process. Technol. 220 106901. https://doi.org/10.1016/J.FUPROC.2021.106901 (2021).

Solmaz, H., Ardebili, S., Calam, A., Yılmaz, E. & Ipci, D. Prediction of performance and exhaust emissions of a CI engine fueled with multi-wall carbon nanotube doped biodiesel-diesel blends using response surface method. Energy https://doi.org/10.1016/J.ENERGY.2021.120518 (2021).

Dev, S., Lafrance, S., Liko, B. & Guo, H. A study on effect of engine operating parameters on nox emissions and exhaust temperatures of a heavy-duty diesel engine during idling. Int. J. Engine Res. 24, 982–998. https://doi.org/10.1177/14680874221076087 (2022).

Qian, F. et al. Ammonia energy fraction effect on the combustion and reduced NOX emission of ammonia/diesel dual fuel. Environ. Res. 119530. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.envres.2024.119530 (2024).

Apicella, B. et al. Effect of after-treatment systems on particulate matter emissions in diesel engine exhaust. Exp. Thermal Fluid Sci. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.expthermflusci.2020.110107 (2020).

Rajak, U., Nashine, P. & Verma, T. Numerical study on emission characteristics of a diesel engine fuelled with diesel-spirulina microalgae-ethanol blends at various operating conditions. Fuel 262, 116519. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.fuel.2019.116519 (2020).

M, P., Zhang, H. & S, P., B, K. V., T, D., & Investigating the impact of oxygenated additives (DEE, DME &MTBE) on engine performance and emission reductions in simarouba methyl ester blends. Int. Res. J. Multidisc.Tech. 112–123. https://doi.org/10.54392/irjmt25310 (2025).

Acknowledgements

The authors gratefully acknowledge the Universiti Sains Malaysia Engineering Campus for its generous support and provision of research facilities.

Funding

Guangxi Science and Technology Program (No. AA24010001, Research Project for Young and Middle-aged Teachers in Guangxi Universities (No.2024KY0624).

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

Conceptualization, Data curation, Writing-original draft – Krishnamoorthy Ramalingam, Mohd. Zulkifly Abdullah, Elumalai PV, Formal analysis, Funding acquisition – Xu Young, Investigation, Methodology, Resources, Supervision - Kashi Sai Prasad, Choon Kit Chan, review & editing - Choon Kit Chan, Prabhakar S, Bai Yuqi.

Corresponding authors

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher’s note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if you modified the licensed material. You do not have permission under this licence to share adapted material derived from this article or parts of it. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Ramalingam, K., Abdullah, M.Z., Elumalai, P.V. et al. An evaluation of maximizing production and usage of biofuel by machine learning and experimental approach. Sci Rep 15, 33265 (2025). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-18757-6

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-18757-6