Abstract

Non-invasive preimplantation genetic testing for aneuploidy (niPGT-A), which analyzes cell-free DNA (cfDNA) from spent culture media (SCM), has emerged as a proposed alternative to trophectoderm (TE) biopsy in in vitro fertilization (IVF). However, its clinical reliability remains unproven. This prospective paired-sample study compared niPGT-A and TE biopsy in 212 blastocysts from 98 couples undergoing IVF, evaluating diagnostic performance and clinical outcome correlation. All embryos underwent simultaneous niPGT-A and TE biopsy, analyzed using next-generation sequencing, with embryo transfers based solely on TE biopsy results. Extended culture to Day 6 significantly improved the informative rate of niPGT-A (from 69.4 to 97.9%). The overall ploidy concordance between niPGT-A and TE biopsy was 75.9%. niPGT-A classified more embryos as aneuploid (75.3%) than TE biopsy (58.5%), including 33 false positives. While niPGT-A showed high sensitivity (91.6%) for aneuploid detection, its specificity was low (50.7%), and discordant embryos (euploid by TE, aneuploid by niPGT-A) achieved unexpectedly high pregnancy (94%) and live birth (88%) rates. These findings highlight that false-positive classification by niPGT-A may result in the unnecessary exclusion of transferable embryos. Despite its non-invasive appeal, niPGT-A lacks sufficient diagnostic accuracy for clinical use. Further refinement of cfDNA analysis, contamination control, and standardization are needed before niPGT-A can be considered for routine clinical implementation.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Preimplantation genetic testing for aneuploidy (PGT-A) is widely employed in in vitro fertilization (IVF) to deselect embryos with chromosomal abnormalities, thereby improving implantation rates and reducing miscarriage risks in selected cases of recurrent pregnancy loss1,2,3. Currently, PGT-A relies on TE biopsy, an invasive procedure that involves extracting embryonic cells for genetic analysis. Although concerns have been raised regarding the invasiveness of TE biopsy, multiple studies have shown that when performed by experienced operators, TE biopsy does not adversely impact implantation potential or neonatal outcomes4,5,6.

In an effort to eliminate biopsy-associated risks, non-invasive PGT-A (niPGT-A) has been proposed. This method analyzes cfDNA released by the embryo into the surrounding spent culture medium (SCM)7. By avoiding direct embryonic manipulation, niPGT-A is conceptually appealing and may offer an alternative to conventional biopsy. Although niPGT-A eliminates the biopsy step, the notion that it reduces procedural risk is unproven. There is currently insufficient evidence that omitting TE biopsy improves overall IVF safety or outcomes8.

While niPGT-A avoids biopsy risks, its diagnostic accuracy remains controversial due to biological and technical limitations, including maternal contamination and variable cfDNA shedding. A key limitation lies in the biological origin and consistency of cfDNA. cfDNA in SCM may be fragmented, contaminated by maternal DNA, or fail to represent the chromosomal status of the embryo’s inner cell mass9,10,11. Moreover, cfDNA yield and integrity vary across embryos, depending on factors such as apoptotic activity, zona pellucida integrity, and culture conditions. To increase cfDNA availability, extended blastocyst culture (e.g., to Day 6) has been suggested12,13. However, prolonged in vitro culture may affect embryo physiology, and it remains unclear whether improved DNA yield actually enhances diagnostic performance. As such, the potential trade-offs between sensitivity, specificity, and clinical safety must be carefully evaluated. These biological and technical challenges limit the diagnostic accuracy of niPGT-A. While some studies have reported encouraging concordance rates with TE biopsy12,14 others highlight frequent false-positive or false-negative results and poor correlation with clinical outcomes15,16,17.

Despite growing commercial interest in niPGT-A, standardized protocols for media collection, DNA amplification, and data interpretation are still lacking. Moreover, most studies to date have not incorporated prospective embryo transfer outcomes or included blinded embryo-level analyses. These gaps underscore the need for rigorous paired-sample studies with direct comparisons to biopsy-based results.

Therefore, this study aimed to evaluate the diagnostic performance of niPGT-A in comparison to TE biopsy, focusing on sensitivity, specificity, and clinical outcome correlation. We also examined whether extending embryo culture enhances cfDNA yield and whether this contributes to improved diagnostic reliability. Our findings aim to clarify whether niPGT-A, in its current form, is appropriate for clinical use—or if fundamental limitations persist.

Materials and methods

We conducted a prospective, single-center cohort study comparing the results of non-invasive and invasive preimplantation genetic testing using SCM and TE biopsy samples from patients who underwent in vitro fertilization (IVF) with intracytoplasmic sperm injection (ICSI) at Lee Women’s Hospital between March 2021 and December 2022. A total of 212 TE biopsy samples and their corresponding spent culture media (SCM) were analyzed, involving 98 couples undergoing preimplantation genetic testing for aneuploidy (PGT-A) cycles. DNA was extracted from both SCM and TE biopsy samples to assess chromosomal abnormalities. The study was conducted with the approval of the institutional review board (IRB: CS1-21005). During the study period, all embryos were cultured to the blastocyst stage. Patients enrolled in the study underwent noninvasive PGT-A (niPGT-A) using SCM in addition to standard PGT-A with TE biopsy, both analyzed using a targeted next-generation sequencing (NGS) platform. Clinical decisions regarding embryo transfer were based on TE biopsy results, as the niPGT-A findings were blinded to patients, clinicians, and embryologists.

In vitro fertilization, embryo culture, TE biopsy, SCM collection and frozen embryo transfer

The ovarian stimulation protocols have been previously described. 2 All patients underwent controlled ovarian hyperstimulation using either GnRH antagonist protocol or progesterone-primed ovarian stimulation (PPOS) protocol. Oocyte retrieval, micromanipulation, embryo culture, TE biopsy, and embryo vitrification or warming were performed in accordance with established protocols9.

To minimize maternal contamination, cumulus cells were carefully removed before microinjection in ICSI cycles. On day 3, each embryo was washed three times in fresh medium, transferred into an individual 20-µL drop and cultured until blastocyst formation. Blastocysts were graded on day 5 or 6 using the Gardner Blastocyst Morphologic Scoring System. Expanded blastocysts were assessed for quality immediately prior to TE biopsy. Based on Gardner’s criteria, blastocysts with at least moderate-quality inner cell mass (ICM) and TE (grades AA, BA, CA, AB, BB, CB, AC, and BC) were classified as good quality. Approximately 5–10 TE cells were biopsied from good-quality blastocysts on day 5 or 6 using laser-assisted hatching, after which the blastocysts were vitrified.

To prevent DNA contamination caused by sample handling, embryos and their culture media were processed under sterile conditions. All operators (including embryologists and genetic technologists) wore gloves, masks, and caps during the procedure. For non-invasive PGT-A (niPGT-A) analysis, SCM was collected immediately before performing the TE biopsy18. After transferring the embryo to a biopsy dish, approximately 10 µL of embryo culture media was collected as an niPGT-A sample using sterile, single-use pipettes14. The samples were then placed into sterile, RNase- and DNase-free PCR tubes and stored at − 80 °C until further analysis. Blank media controls were included in each of the 15 sequencing runs (24 samples per run), resulting in a total of 15 blank controls analyzed in parallel with SCM samples. The media was collected on culture day 5 or 6, depending on the developmental progression of each embryo.

Whole-genome amplification (WGA) of cfDNA from both TE biopsy and SCM samples was performed using the SurePlex WGA system (VeriSeq PGS Kit, Illumina). We followed the manufacturer’s recommendations (VeriSeq PGS Kit, Illumina), requiring a minimum post-WGA DNA concentration and sequencing quality (Q30 and mapping rates). Specifically, for post-WGA DNA, we used a cutoff of 0.5 ng/µL for 1/10 diluted WGA product to ensure a minimum input for sequencing. Sequencing quality criteria included ≥ 250,000 reads after filtering and an overall noise (DLR - Derivative Log Ratio) below 0.4. Samples failing library preparation or falling below quality thresholds were excluded. DNA libraries were subsequently prepared and sequenced on the Illumina MiSeq platform. Chromosome ploidy levels were analyzed using BlueFuse Multi software (Illumina), with the results independently verified by two technicians to ensure accuracy.

All patients underwent frozen embryo transfer (FET) using either a natural cycle or an artificial cycle for endometrial preparation. Artificial cycles involved estradiol and progesterone supplementation, with a required endometrial thickness of at least 8 mm before proceeding with FET19.

Statistical analysis

Chi-squared and Fisher’s exact tests were used to assess the concordance rates between SCM-based non-invasive PGT-A (niPGT-A) and TE-based PGT-A in detecting chromosomal abnormalities. Sensitivity and specificity were calculated to evaluate the diagnostic accuracy of niPGT-A. Statistical significance was defined as p < 0.05.

Results

PGT-A outcomes and DNA yield: analysis of TE biopsy and spent culture media

A total of 212 TE biopsy samples and their corresponding SCM from 98 couples undergoing preimplantation genetic testing for aneuploidy (PGT-A) cycles were analyzed. Based on PGT-A results from TE biopsy, 88 blastocysts were classified as euploid, while 124 were aneuploid. The maternal age of participants ranged from 20 to 45 years, with a mean age of 38.4 ± 3.6 years. Maternal age was comparable between Day 5 (38.4 ± 3.6 years) and Day 6 (38.7 ± 3.7 years) groups.

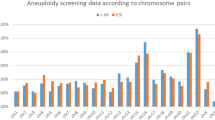

The results presented in Table 1 demonstrate significant findings regarding the informative rate and NGS aneuploidy detection across different methodologies and developmental stages. The informative rate for TE biopsy was consistently 100% across Day 5 (D5), Day 6 (D6), and the total cohort (212/212), indicating that all samples yielded usable results. In contrast, the informative rate for SCM was significantly lower at 69.4% on D5 but increased markedly to 97.9% on D6, resulting in an overall rate of 82.1% (174/212), with a statistically significant difference between Day 5/Day 6 (P < 0.001). The lower informativity of SCM compared to TE biopsy may be attributed to DNA amplification failures in some specimens. As embryo culture duration increased, cfDNA concentration in the medium also rose, supporting the hypothesis that extended culture promotes cfDNA release. This finding underscores the potential for improved SCM-based diagnostics with longer cultivation periods.

Regarding the NGS aneuploidy rate, TE biopsy showed a consistent rate of 58.5% across D5, D6, and the total cohort (124/212), with varying levels of statistical significance (P < 0.05, P < 0.01, and P < 0.001). SCM, however, displayed higher aneuploidy rates of 73.2% on D5, 77.2% on D6, and 75.3% overall (131/174), with significant differences observed across days. These findings highlight the robustness of TE biopsy in providing consistent results, while SCM exhibits variability in both informative rate and aneuploidy detection, albeit with a higher overall aneuploidy rate compared to TE biopsy.

Concordance rates between TE biopsy and SCM in day 5 and day 6 blastocysts

The concordance results were categorized into total concordance, full concordance, partial concordance, and concordance rates for sex determination. Detailed data for all samples are presented in Table 2. The overall total concordance for ploidy was 75.9% (132/174), with comparable rates between D5 (76.8%, 63/82) and D6 (73.4%, 69/94) blastocysts. This indicates that the duration of culture did not significantly affect the overall ploidy concordance between TE biopsy and SCM.

Full concordance, where SCM and TE biopsy results were completely consistent, was observed in 50.0% of samples (87/174). The rate was slightly lower for D5 blastocysts (46.3%, 38/82) compared to D6 blastocysts (52.1%, 49/94). Similarly, partial concordance, where SCM and TE biopsy results were partially consistent, was noted in 25.9% of samples (45/174), with rates of 30.5% (25/82) for D5 and 21.3% (20/94) for D6. These findings suggest that extending the duration of culture from D5 to D6 does not significantly impact the concordance rates between SCM and TE biopsy, demonstrating the consistency of the non-invasive method across different developmental stages.

For sex determination, there was complete concordance at 100% across D5, D6, and the total cohort (174/174). These findings underline the high reliability of SCM for sex determination, while the ploidy concordance demonstrates moderate agreement with TE biopsy results, without significant variation between developmental stages.

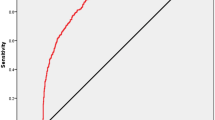

Diagnostic accuracy of SCM versus TE biopsy for PGT-A: sensitivity and specificity analysis

The diagnostic sensitivity of niPGT-A, representing its ability to correctly identify aneuploid embryos, was found to be 91.6%. (Table 3) This high sensitivity indicates that niPGT-A is effective in detecting chromosomal abnormalities when compared to the standard TE biopsy-based PGT-A. However, the specificity of niPGT-A, which measures its ability to correctly identify euploid embryos, was lower, at 50.7%. These findings indicate that while niPGT-A effectively detects aneuploid embryos, its low specificity limits its ability to reliably confirm euploidy, increasing false-positive risk.

Notably, the sensitivity and specificity of niPGT-A were consistent across Day 5 and Day 6 blastocysts, with only minor variations observed. This stability in diagnostic performance across different developmental stages is encouraging, as it implies that the timing of biopsy within the blastocyst stage does not significantly affect the accuracy of niPGT-A. Nevertheless, the relatively low specificity highlights the need for further refinement of the method to improve its reliability in clinical settings.

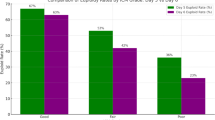

Clinical outcomes post-embryo transfer

To evaluate the clinical implications of niPGT-A findings, a total of 23 blastocysts were transferred. Among these, 7 blastocysts were categorized as euploid by both SCM-based niPGT-A and TE biopsy-based PGT-A, while the remaining 16 showed discordant results between the two testing methods. Notably, all transferred embryos were selected based on TE biopsy results; niPGT-A findings were blinded and did not influence clinical decision-making.

The euploid SCM group demonstrated a clinical pregnancy rate of 57% (4/7), whereas the aneuploid SCM group had a significantly higher rate of 94% (15/16). Miscarriage rates were 25% (1/4) in the euploid SCM group compared to 6% (1/15) in the aneuploid SCM group. Live births were recorded in 3 cases within the euploid SCM group and 14 cases in the aneuploid SCM group. (Table 4)

These unexpected outcomes suggest that niPGT-A, while promising as a non-invasive diagnostic tool, may currently lack predictive validity for clinical outcomes, particularly in cases of discordance with TE biopsy results. The findings highlight the complexity of embryonic development and the potential limitations of relying solely on niPGT-A results for clinical decision-making.

Discussion

Our study provides a comprehensive evaluation of niPGT-A by comparing its outcomes with TE biopsy-based PGT-A. The results highlight both the potential and the challenges of niPGT-A, particularly regarding its diagnostic accuracy, concordance rates, and clinical utility.

Our data revealed that culture duration significantly impacts the informative rate of niPGT-A. The increase in informative rate from 69.4% on Day 5 to 97.9% on Day 6 suggests that extended culture time enhances cfDNA availability in SCM. This finding aligns with prior research indicating that prolonged incubation improves cfDNA recovery, likely due to increased cellular turnover and DNA shedding. This finding is also consistent with the review by Sakkas et al.20 who emphasized that modifications in embryo culture protocols to support niPGT-A do not compromise embryo viability. Our findings also align with recent work by Takeuchi et al.21 who reported that zona pellucida integrity and early blastocyst development impact cfDNA content and its correlation with TE biopsy results. Taken together, these results suggest that adjusting culture conditions may enhance niPGT-A reliability, though additional studies are required to evaluate the long-term impact on embryo quality and implantation potential.

The observed total concordance rate of 75.9% between niPGT-A and TE biopsy suggests moderate agreement in ploidy assessment. However, the variability between full concordance (50.0%) and partial concordance (25.9%) underscores the need for methodological refinement. The higher aneuploidy detection rate in niPGT-A (75.3%) compared to TE biopsy (58.5%) raises concerns about potential false-positive results, particularly given niPGT-A’s relatively low specificity (50.7%). This suggests that niPGT-A may overestimate aneuploidy due to factors such as maternal DNA contamination or the presence of apoptotic embryonic cells. The origin of SCM cfDNA is poorly understood, likely stemming from apoptotic embryonic cells or maternal contaminants. This obscures its representation of true embryonic ploidy, limiting clinical reliability. Volovsky et al. highlighted that maternal DNA contamination remains a persistent issue that may overestimate aneuploidy in niPGT-A analysis16. Future studies should explore novel methods to selectively enrich embryonic cfDNA while minimizing contamination.

A major strength of niPGT-A observed in this study is its high sensitivity (91.6%) in detecting aneuploid embryos, suggesting its potential as an effective screening tool to rule out chromosomally abnormal embryos. However, its lower specificity (50.7%) presents a critical limitation. Despite its high diagnostic sensitivity, the elevated false-positive rate significantly limits niPGT-A’s clinical applicability. This discrepancy may stem from cfDNA degradation, amplification failures, or maternal contamination, highlighting the urgent need for methodological improvements to enhance specificity.

Our findings challenge the assumption that niPGT-A can reliably predict clinical outcomes. Notably, the clinical pregnancy rate for embryos classified as euploid by both niPGT-A and TE biopsy was 57%, whereas discordant embryos (classified as aneuploid by niPGT-A but euploid by TE biopsy) had a remarkably higher pregnancy rate of 94%. Similarly, live birth rates were higher in the discordant group, suggesting that niPGT-A’s classification of aneuploid embryos may not always align with true implantation potential. These results reinforce previous reports that cfDNA in SCM might not always reflect the chromosomal status of the inner cell mass, leading to misclassification. This finding is consistent with Bednarska-Czerwińska et al.13 who reported that niPGT-A often misclassifies euploid embryos due to amplification failures and cfDNA degradation, affecting implantation potential.

The unexpected success of embryos classified as aneuploid by niPGT-A but euploid by TE biopsy suggests a need to refine cfDNA analysis to distinguish between biologically relevant aneuploidy and transient chromosomal mosaicism. This finding further supports the notion that niPGT-A alone should not be used as the sole determinant for embryo selection at this stage.

Internationally, several commercial platforms for niPGT-A have emerged, with some undergoing Conformité Européenne (CE) marking and early-stage validation in Europe and Asia. However, standardized protocols for sample collection, cfDNA extraction, and bioinformatics pipelines remain lacking. Most studies to date have not included clinical outcome correlation or prospective blinded designs, limiting their translational applicability. Our study contributes to this evolving field by providing matched embryo-level analysis and clinical follow-up data under blinded conditions. These findings may inform future multicenter efforts to establish standardized niPGT-A workflows and regulatory guidelines.

Several limitations should be acknowledged when interpreting the results of this study. First, the sample size, although moderate, may not fully capture the variability across different patient populations or clinical protocols. Clinical outcomes are preliminary and should be interpreted with caution and warrant validation in larger cohorts. Larger niPGT-A-guided transfer studies are needed to validate predictive value. Second, the presence of maternal DNA contamination in SCM remains a technical challenge that could compromise the specificity of niPGT-A. Third, the cfDNA yield varied among embryos, possibly reflecting biological heterogeneity or technical inconsistencies in DNA release and amplification. The possibility that Y-chromosome detection in cfDNA may be more robust due to its unique sequence composition. The 100% concordance for sex suggests robust detection of sex chromosomes, particularly the Y chromosome. However, this result should be interpreted cautiously, as sex chromosomes constitute only a small portion of the genome and may not represent overall chromosomal concordance. Another critical limitation of our study is the absence of per-chromosome concordance analysis. Evaluating concordance only at the aggregate ploidy level may mask chromosome-specific inaccuracies, thereby potentially inflating the estimated diagnostic performance of niPGT-A. In populations with high aneuploidy prevalence, such as advanced maternal age groups, this can lead to systematic misclassification. To ensure reliable clinical interpretation, future validation studies should incorporate per-chromosome concordance analysis as a minimum reporting standard. Additionally, amplification failure in early-stage embryos may contribute to data loss and diagnostic uncertainty. Moreover, although our design ensured blinding of niPGT-A results during clinical decision-making, the lack of prospective clinical validation using niPGT-A-guided transfer limits our ability to draw definitive conclusions about its predictive value. Lastly, while extended embryo culture appeared to improve cfDNA yield, the potential effects of prolonged in vitro culture on embryo quality and developmental competence remain uncertain and warrant further investigation.

Conclusions

While non-invasive PGT-A (niPGT-A) represents a promising approach to embryo screening without the need for biopsy, our findings highlight important limitations that must be addressed before routine clinical implementation. Although niPGT-A demonstrated high sensitivity in detecting aneuploid embryos, its low specificity and the observed discordance with clinical outcomes suggest that the current methodology may lead to the misclassification of viable embryos. These issues underscore the need for further optimization in cfDNA recovery, contamination control, and bioinformatic interpretation. At present, niPGT-A is not ready for clinical application. Substantial improvements in specificity and contamination control are essential, and it should not replace trophectoderm biopsy in clinical decision-making until its diagnostic accuracy is reliably established.

Data availability

The datasets generated and analyzed during the current study are available from the corresponding author on reasonable request.

References

Munne, S. et al. Preimplantation genetic testing for aneuploidy versus morphology as selection criteria for single frozen-thawed embryo transfer in good-prognosis patients: A multicenter randomized clinical trial. Fertil. Steril. 112(e1077), 1071–1079. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.fertnstert.2019.07.1346 (2019).

Carvalho, B. R. Great challenges remain for niPGT-A reliability. Rev. Bras. Ginecol. Obstet. 44, 721–722. https://doi.org/10.1055/s-0042-1744291 (2022).

Mumusoglu, S., Telek, S. B. & Ata, B. Preimplantation genetic testing for aneuploidy in unexplained recurrent pregnancy loss: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Fertil. Steril. 123, 121–136. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.fertnstert.2024.08.326 (2025).

Scott, K. L., Hong, K. H. & Scott, R. T. Jr. Selecting the optimal time to perform biopsy for preimplantation genetic testing. Fertil. Steril. 100, 608–614. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.fertnstert.2013.07.004 (2013).

Zhang, W. Y. et al. Maternal and neonatal outcomes associated with trophectoderm biopsy. Fertil Steril 112, 283–290 e282, (2019). https://doi.org/10.1016/j.fertnstert.2019.03.033

Li, S. et al. Non-Assisted hatching trophectoderm biopsy does not increase the risks of most adverse maternal and neonatal outcome and May be more practical for busy clinics: Evidence from China. Front. Endocrinol. (Lausanne) 13, 819963. https://doi.org/10.3389/fendo.2022.819963 (2022).

Huang, L. et al. Noninvasive preimplantation genetic testing for aneuploidy in spent medium May be more reliable than trophectoderm biopsy. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U S A 116, 14105–14112. https://doi.org/10.1073/pnas.1907472116 (2019).

De Vos, A. & De Munck, N. Trophectoderm biopsy: Present state of the Art. Genes (Basel) 16 https://doi.org/10.3390/genes16020134 (2025).

Chen, H. H. et al. Optimal timing of blastocyst vitrification after trophectoderm biopsy for preimplantation genetic screening. PLoS One 12, e0185747. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0185747 (2017).

Hanson, B. M. et al. Noninvasive preimplantation genetic testing for aneuploidy exhibits high rates of deoxyribonucleic acid amplification failure and poor correlation with results obtained using trophectoderm biopsy. Fertil. Steril. 115, 1461–1470. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.fertnstert.2021.01.028 (2021).

Nakhuda, G., Rodriguez, S., Tormasi, S. & Welch, C. A pilot study to investigate the clinically predictive values of copy number variations detected by next-generation sequencing of cell-free deoxyribonucleic acid in spent culture media. Fertil. Steril. 122, 42–51. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.fertnstert.2024.02.030 (2024).

Chow, J. F. C. et al. Optimizing non-invasive preimplantation genetic testing: Investigating culture conditions, sample collection, and IVF treatment for improved non-invasive PGT-A results. J. Assist. Reprod. Genet. 41, 465–472. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10815-023-03015-3 (2024).

Bednarska-Czerwińska, A. et al. Comparison of Non-Invasive and minimally invasive preimplantation genetic testing for aneuploidy using samples derived from the same embryo culture. J. Clin. Med. 14 https://doi.org/10.3390/jcm14010033 (2024).

Rubio, C. et al. Multicenter prospective study of concordance between embryonic cell-free DNA and trophectoderm biopsies from 1301 human blastocysts. Am. J. Obstet. Gynecol. 223, 751 e751–751 e713. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ajog.2020.04.035 (2020).

de Albornoz, E. C. et al. Non invasive preimplantation testing for aneuploidies in assisted reproduction: A SWOT analysis. Reprod. Sci. 32, 1–14. https://doi.org/10.1007/s43032-024-01698-2 (2025).

Volovsky, M., Scott, R. T. Jr. & Seli, E. Non-invasive preimplantation genetic testing for aneuploidy: Is the promise real? Hum. Reprod. 39, 1899–1908. https://doi.org/10.1093/humrep/deae151 (2024).

Lledo, B., Morales, R., Antonio Ortiz, J., Bernabeu, A. & Bernabeu, R. Noninvasive preimplantation genetic testing using the embryo spent culture medium: An update. Curr. Opin. Obstet. Gynecol. 35, 294–299. https://doi.org/10.1097/gco.0000000000000881 (2023).

Goodrich, D. et al. A randomized and blinded comparison of qPCR and NGS-based detection of aneuploidy in a cell line mixture model of blastocyst biopsy mosaicism. J. Assist. Reprod. Genet. 33, 1473–1480. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10815-016-0784-3 (2016).

Lee, C. I. et al. Embryo morphokinetics is potentially associated with clinical outcomes of single-embryo transfers in preimplantation genetic testing for aneuploidy cycles. Reprod. Biomed. Online 39, 569–579. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.rbmo.2019.05.020 (2019).

Sakkas, D. et al. The impact of implementing a non-invasive preimplantation genetic testing for aneuploidies (niPGT-A) embryo culture protocol on embryo viability and clinical outcomes. Hum. Reprod. 39, 1952–1959. https://doi.org/10.1093/humrep/deae156 (2024).

Takeuchi, H. et al. Conditions for improved accuracy of noninvasive preimplantation genetic testing for aneuploidy: Focusing on the Zona pellucida and early blastocysts. Reprod. Med. Biol. 23, e12604. https://doi.org/10.1002/rmb2.12604 (2024).

Acknowledgements

The authors would like to thank the medical and laboratory teams at Lee Women’s Hospital for their valuable assistance throughout the study. We also sincerely appreciate the participation and cooperation of all the patients involved.

Funding

This research received no external funding.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

Ting-Feng Wu wrote the initial manuscript and revised by Pin-Yao Lin. Hui-Hsin Shih analyzed the data and generated tables. Pin-Yao Lin, Chun-I Lee and Tsung-Hsien Lee assisted in collection of cases and discussed findings of the study. En-Hui Cheng and Hui-Hsin Shih, conducted experiments, generated figures and analyzed the NGS data. Chun-Chia Huang supervised IVF lab and facilitated all IVF-ET procedures. Maw-Sheng Lee made substantial contributions to the design of the study, recruitments of participants and monitoring clinical outcomes. All authors read and approved the final manuscript.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Ethics approval and consent to participate

This study was conducted in accordance with the ethical standards of the institutional and/or national research committee and with the 1964 Helsinki Declaration and its later amendments or comparable ethical standards. Ethical approval was obtained from the Institutional Review Board of Chung Shan Medical University Hospital (IRB number: CS1-21005). Written informed consent to participate in this study was obtained from all individual participants.

Consent for publication

All participants provided written consent for the publication of anonymized data related to this study. No identifying information is included in this manuscript.

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher’s note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if you modified the licensed material. You do not have permission under this licence to share adapted material derived from this article or parts of it. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Wu, TF., Lee, CI., Shih, HH. et al. Extended blastocyst culture improves DNA yield in non-invasive preimplantation genetic testing for aneuploidy but diagnostic specificity remains limited. Sci Rep 15, 34906 (2025). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-18764-7

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-18764-7