Abstract

Numerous urinary acidic free-glycan tumor marker candidates have been identified based on the glycan structure profiles of human cancer tissues. In this study, to identify novel glycan tumor markers, we performed precise glycan structural analysis focusing on neutral free-glycans in colorectal cancer tissues. Our analysis detected one free-glycan that was significantly elevated in colorectal cancer cells by comparison to the corresponding normal epithelial cells. Structural studies of this glycan revealed it to comprise a free-N-glycan with a difucosylated type-1 lactosamine structure (Lewis B antigen), rather than a conventional type-2 lactosamine structure. The presence of N-glycans with type-1 lactosamine structure has rarely been reported in humans. To investigate its clinical usefulness, the level of this free-glycan in the urine of 121 healthy subjects, 141 gastric cancer patients, 87 colorectal cancer patients, 55 pancreatic cancer patients, 13 bile duct cancer patients and 79 rare cancer patients were measured using a liquid chromatography-selected reaction monitoring assay. Significant differences were detected in cancer patient samples compared to healthy controls, with a marked increase in some rare-types of cancer patient samples, such as AFP-producing gastric cancer.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Liquid biopsy is a means of capturing heterogeneity within cancers. Significant research effort is focused on searching for tumor biomarkers in biological fluids that are less invasive. Blood markers currently in clinical use include α-fetoprotein (AFP), carcinoembryonic antigen (CEA), and carbohydrate antigen 19-9 (CA19-9), which are used to confirm treatment efficacy and monitor cancer recurrence. The most frequently used tumor marker, mainly for pancreatic cancer, is CA19-9, which is detected as a cancer antigen by antibodies that recognize the altered glycan structure sialyl Lewis A on the cancer cell membrane1,2. AFP, which is used to monitor the development of hepatocellular carcinoma, has been reported to have oncogenic glycan mutations and its cancer specificity is increased as fucosylated AFP (AFP-L3)3,4. Thus, aberrant glycan structures on cancer cells have been used for cancer detection and can act as valuable diagnostic tools in clinical practice. However, there are many cancer patients for whom existing tumor markers are not elevated. CA19-9 cannot be used as a tumor marker in people with a deficiency of Lewis enzyme, which is the enzyme that synthesizes its target glycan structure. Additionally, certain individuals might be incorrectly identified as positive cases. Furthermore, most markers are unable to detect early-stage cancer. Therefore, there is an urgent need to develop novel markers.

Alterations in glycan structure have been observed in many cancer cells, which are the result of changes in the expression levels of glycosyltransferases. Consequently, abnormal glycoconjugates with synthesis defects, such as aberrant extensions or branching structures, appear on the cell surface. The detection of these aberrant glycan structures in cancer cells is linked to the discovery of novel tumor markers5. The search for cancer antigens has conventionally relied on monoclonal antibodies against cancer tissues and cell lines6. Subsequently, mass spectrometry-based and lectin-based glycomics have been utilized to detect such cancer antigens7,8. We have also comprehensively analyzed glycan structures using cancer patient tissues with the aim of identifying novel tumor markers. First, glycosphingolipid (GSL) glycan analysis of colon cancer tissue revealed novel glycan structures associated with malignant transformation of cancer9,10,11. Based on these findings, glycomics using high-performance liquid chromatography (HPLC) was applied to O-glycan structures added to glycoproteins in cancer patient sera, leading to the discovery of many acidic glycan structures that were significantly elevated in cancer patients, including sulfated glycans and Sda antigens12,13,14,15. Furthermore, we identified the accumulation of acidic free-glycans, such as Neu5Ac, KDN or sulfate addition, in pancreatic, prostate and colorectal cancer tissues, respectively16,17 (our unpublished data). These findings led us to profile urinary free-glycans in both cancer patients and healthy subjects. Glycomics analysis of urinary free-glycans in cancer patients helped identify many acidic free-glycans as potential tumor marker candidates, which could be useful tools for cancer diagnosis18,19. The clinical utility of these acidic tumor marker candidates was validated using the urine from a large number of cancer patients20.

In addition to acidic tumor marker candidates found in body fluids, neutral free-glycans are also tumor marker candidates. We previously reported the identification of d-arabinose containing neutral free-N-glycans in urine from cancer patients, which were not thought to be present in humans21. These observations prompted us to focus on neutral glycans in cancer tissues as a means of identifying novel tumor marker candidates. In the present study, we examined neutral free-glycans significantly elevated in colon cancer tissues and detected a unique glycan structure. Quantification of the levels of this glycan in urine from a large number of cancer patients and healthy controls showed it to be markedly elevated in several rare-types of cancer.

Results

Comparison of neutral free-glycan profiles of colorectal cancer cells and normal colonic epithelial cells

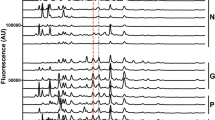

To conduct a tumor marker search focusing on neutral components, surgical specimens from 16 colorectal cancer patients with various clinical symptoms were obtained (Table S1)10. Neutral free-glycans and GSL glycans were extracted from cells of primary colorectal cancer and surrounding normal colonic mucosa purified with anti-CD326 antibody, an epithelial cell marker10. Neutral free-glycans were fluorescently labeled with 2-aminopyridine (PA) by reductive amination. The neutral PA-labelled glycan mixtures derived from cancerous and non-cancerous parts of the same patient were each fractionated by normal phase-HPLC, and the fractions were further separated by reversed phase-HPLC. Comparison of the elution patterns allowed us to ascertain whether the composition of free-glycans in the cancer cells was altered. This analysis highlighted a peak that was detected in some colorectal cancer specimens but was either not observed or barely detectable in the corresponding chromatograms of non-cancer specimens (Fig. 1 and Figure S1). This peak was collected for glycan structural analysis.

Comparison of normal phase- and reversed phase-HPLC profiles of neutral PA-oligosaccharides obtained from primary lesions of colorectal cancers and their surrounding normal colorectal mucosa. The patterns of PA-oligosaccharides eluted by normal phase-HPLC (A) and by reversed phase-HPLC (B) are shown. Chromatograms of the neutral fraction from colon cancer cells (a, c) and normal colonic cells (b, d) of No. 10 and No. 14 patients (Table S1), respectively. The peaks of gray zones in normal phase-chromatograms were collected, and then subjected to reversed phase-HPLC. Asterisks in (A) indicate GSL glycans containing Lewis A and X. The peaks indicated by a single asterisk were high-mannose type free-N-glycans (M5A’) and the peak indicated by a double asterisk was GSL glycan with A-blood antigen (ALeb) in (B). These GSL glycans were previously reported by Misonou et al10.

Structural analysis of the neutral free-glycan

First, the glycan structural components of the peak observed in several cancer tissue samples (5 of 16 specimens) were predicted by mass spectrometry. The expression of this peak was not dependent on the histological differentiation of the cancer, but was clearly observed in cancer specimens. This glycan was composed of Hex3HexNAc2dHex2-PA (m/z 1281 [M + H]+), comprising a Hex-HexNAc-Hex-Hex-HexNAc backbone with two fucose residues, the difucosylated Gn1 type N-glycan (Fig. 2). Next, an exoglycosidase digestion of the sample was performed followed by two-dimensional mapping using isomaltooligosaccharides and reference compounds combined with mass spectrometry analysis (Fig. 3). The sequential digestion of neutral glycan with α1,2-l-fucosidase and α1,3/4-l-fucosidase resulted in conversion to a Hex-HexNAc-Hex-Hex-HexNAc backbone and revealed the presence of α1,2-linked and α1,3/4-linked fucose residues, respectively. Notably, the defucosylated backbone structure could be digested with β1,3-galactosidase or Lacto-N-biosidase, but not β1,4-galactosidase, indicating that the backbone structure was an N-glycan with a type-1 lactosamine (Galβ1,3GlcNAc) rather than a more typical type-2 lactosamine (Galβ1,4GlcNAc). Such an N-glycan with a type-1 lactosamine has rarely been reported in human glycoproteins. The resulting digestion product after β1,3-galactosidase treatment was identical to a Gn1 type N-glycan with an α1,3-mannose arm extended β1,4 branching N-acetylglucosamine on the two-dimensional map. The glycan structure was estimated to be an N-glycan possessing a difucosylated type-1 lactosamine, known as Lewis B blood group antigen, Fucα1,2Galβ1,3(Fucα1,4)GlcNAcβ1,4Manα1,3Manβ1,4GlcNAc-PA.

Two-dimensional mapping of the neutral N-glycan sequentially digested with glycosidase. Elution positions of PA-glycans on normal phase- and reversed phase-HPLC are represented by glucose units (GU) on the y-axis and x-axis, respectively. Closed black circles indicate the position of the neutral difucosylated N-glycan or its products by sequential enzymatic digestions. Closed gray circles show the positions of the authentic compounds. Enzymes used for glycan structural analyses are abbreviated as follows: 2F, α1,2-l-fucosidase; 34F, α1,3/4-l-fucosidase; 3G, β1,3-d-galactosidase; L-Bio, Lacto-N-biosidase. Symbol representations of glycans are as follows; galactose, yellow circle; mannose, green circle; GlcNAc, blue square; fucose, red triangle.

Measurement of the urinary type-1 free-N-glycan having Lewis B antigen

Free-glycans present in the blood are quickly excreted into the urine. The clinical utility of this neutral free-glycan for cancer diagnosis was assessed by measuring its urinary level in patients with various cancers. Measurements were performed using the selected reaction monitoring (SRM) quantitative method, as previously reported20. Briefly, free-glycans were extracted from urine equivalent to 200 µg creatinine spiked with an internal standard. Samples were fluorescently labeled and then the PA-labeled glycan mixture was subjected to SRM. Relative quantification was performed from the area ratio of the target glycan to the internal standard. The SRM method was optimized for the target difucosylated type-1 free-glycan. Because the optimized SRM for measurement of this glycan structure showed linearity up to an order of magnitude > 2, we measured the free-glycans in urine equivalent to 10 μg creatinine of patient urine samples (Figure S2 and Table S2). The urinary levels of type-1 N-glycan having Lewis B antigen were determined using each PA-glycan mixture prepared from the urine of 121 healthy subjects, 141 gastric cancer patients, 87 colorectal cancer patients, 55 pancreatic cancer patients, 13 bile duct cancer patients, and 79 rare cancer patients (Tables S3 and S4). The limit of quantitation (LOQ) for this glycan was determined to be 50 fmol (Figure S2 and Table S2). Urinary samples that showed values below the LOQ were excluded. The final measurable number of samples were 98 healthy subjects, 115 gastric cancer patients, 75 colorectal cancer patients, 46 pancreatic cancer patients, 13 bile duct cancer patients, and 58 rare cancer patients. The quantitative results of SRM showed that this neutral free-glycan was significantly elevated in gastric, colorectal, pancreatic, and bile duct cancers (gastric cancer; p = 0.0237, colorectal cancer; p = 0.0111, pancreatic cancer; p = 0.0001 and bile duct cancer; p < 0.0001) (Fig. 4). The significant differences were confirmed for colorectal, pancreatic and bile duct cancers, even without excluding cases showing values below the LOQ (colorectal cancer; p = 0.0241, pancreatic cancer; p = 0.0317 and bile duct cancer; p < 0.0001). Conversely, there were no significant differences in the levels of this neutral free-glycan in the rare cancer samples (Table S4). The specimen that gave the highest level by far of this glycan was from a patient with advanced AFP-producing gastric cancer. Specifically, the urinary level in the patient was > 70 times higher than the highest value found in healthy subjects (Fig. 4, Dot No.1 indicated by arrow). The next highest level was found in a patient with colon cancer and bone/brain metastases, with a level more than six times higher than the highest value found in the healthy controls (Fig. 4, Dot No.2 indicated by arrow). The next highest levels of this glycan were from a patient with neuroendocrine carcinoma (NEC), classified as a rare cancer, a patient with scirrhous gastric cancer, and a patient with ascending colon cancer (Fig. 4, Dot Nos.3, 4 and 5, respectively; indicated by arrows). Clinical information for the top five patients along with the corresponding high glycan levels is shown in Table 1. Colorectal cancer with brain and bone metastases has been reported to have elevated CEA22. However, the CEA level of the patient who showed the second highest neutral free-glycan level was in the normal range, and other markers such as CA19-9, AFP, CA125, SCC and CA15-3 were also negative (No. 2 patient in Table 1 and data not shown).

The urinary levels of difucosylated type-1 N-glycan determined by the SRM assay. The levels of type-1 free-glycan in the urine of control individuals and various cancer patients are shown. The numbers in the graph correspond to the patient numbers shown in Table 1. Abbreviations indicate the following: N, normal control; G, gastric cancer; C, colorectal cancer; P, pancreatic cancer; B, bile duct cancer; R, rare cancer. The values shown on the y-axis are expressed on a logarithmic 10 scale. The red lines represent the respective median. Mann–Whitney test was used to verify significant differences. Single asterisks indicate the p-value of 0.05 > , double asterisks the p-value of 0.0001 or less, and nd no significant difference.

Discussion

Our previous search for cancer tissue-specific glycan structures contributed greatly to the discovery of acidic tumor marker candidates in the serum and urine of cancer patients. In this study, we focused on the analysis of neutral free-glycans in cancer tissues. We identified a novel tumor-specific glycan structure, N-glycan having difucosylated type-1 lactosamine, that has rarely been reported before in human. Urinary level measurements by SRM of this neutral free-glycan showed it to be significantly elevated in cancer patients, although some samples were below the limit of detection. This unique glycan structure showed particularly high urinary concentrations in some patients with rare-types of cancer.

Although the presence of the unique free-glycan in the urine of cancer patients has been demonstrated, it remains to be confirmed whether this directly reflects the corresponding level present in the cancer tissue. Nonetheless, in our previous research, we found that free-glycans present at elevated levels in cancerous tissue often display high levels in the urine of cancer patients17,18. Therefore, we speculate that glycan structures showing high levels in the urine of cancer patients are likely to have originated from cancerous tissue.

The SRM measurements revealed a small number of samples with conspicuously high levels of urinary type-1 free-N-glycan having Lewis B antigen. The specimen with an extremely high level was from the patient with advanced gastric cancer, diagnosed as a rare-type of the gastric cancer, known as AFP-producing gastric cancer. AFP-producing gastric cancer, which accounts for less than 10% of all gastric cancer cases, shows aggressive features and has an extremely poor prognosis. Patients with AFP-producing gastric cancer are particularly prone to vascular invasion, as well as lymph node and liver metastasis23,24. The next highest level of the glycan was from a patient with a form of colon cancer associated with bone and brain metastases. Colorectal cancer generally metastasizes to the liver and lungs, whereas brain and bone metastases are rare (0.6–3.2 and 2.7–6.12%, respectively)25,26,27. Other cancer types that displayed high levels of this glycan were neuroendocrine carcinoma, a rare cancer (fewer than six cases per 100,000 population), and scirrhous gastric carcinoma, an uncommon type of gastric cancer. In summary, the level of type-1 free-N-glycan with Lewis B antigen was slightly elevated in many cancer samples, but those with significantly increased glycan levels were all rare-types of cancer with multiple metastases (Table 1). The mechanism of the patient-specific increase of this free-N-glycan structure is unknown, but it may be an indicator of diverse cancerous changes.

Furthermore, the levels of type-1 free-N-glycan with Lewis B antigen were measured in urine samples from patients with benign diseases such as lipomas and bone cysts. Although additional investigation is necessary due to the small number of samples, none of these analyzed samples contained extremely high levels of the glycan. However, no significant differences were found between the benign disease group and the sample group of other cancers excluding bile duct cancer and the healthy control. We performed univariate analysis, but the area under curve (AUC) values on the receiver operating characteristic (ROC) curve were low (0.566 for gastric cancer, 0.589 for colorectal cancer, 0.6 for pancreatic cancer) because the number of samples showing high values was too small. Further investigation is necessary to establish whether this glycan structure can be utilized for cancer detection.

The nonreducing terminal structure of the difucosylated free-N-glycan is known as the Lewis B blood group antigen. This moiety is synthesized by β1,3 galactosyltransferase (β3GalT), α1,2 fucosyltransferase (H enzyme) and α1,4 fucosyltransferase (Lewis enzyme, also called FUT3)28. The Lewis enzyme lacks its activity in approximately 10% of humans due to homozygotes with inactive Lewis gene alleles29,30. Like the sialyl Lewis A (CA19-9) antigen and Lewis A structure, Lewis negative individuals are unable to synthesize the Lewis B structure31,32,33. This may explain why some specimens were below the LOQ for this type-1 N-glycan having Lewis B. Unfortunately, the corresponding Lewis type of the clinical samples used in this study are unknown. However, no correlation was found between the levels of free-N-glycan with Lewis B and CA19-9 values of 2 or less (Lewis negative or low CA19-9 value) in the patients analyzed in this study. Indeed, we identified CA19-9 negative patients with measurable free-N-glycan including Lewis B, and vice versa. Previous studies have detected the glycolipid structure with Lewis B in tumor tissues from Lewis negative cancer patients. These findings suggest Lewis negative individuals cannot make Lewis A structures but can synthesize Lewis B structures, presumably by utilizing FUT511. There may be enzymes or mechanisms that add fucose residues to the free-glycan backbone structure regardless of the presence or absence of Lewis enzymes.

Human complex-type N-glycan has type-2 lactosamine cores, which is characteristic of vertebrates in evolutionary lineages. By contrast, type-1 N-glycan is present in plants and invertebrates34,35,36,37, although type-1 N-glycan-attached glycoproteins have been reported in some vertebrates38,39,40. Conventional type-2 lactosamine is synthesized by β1,4 galactosyltransferase (β4GalT). Analysis of β4GalT knockout mice revealed that the non-reducing terminal structure of N-glycan is replaced by a type-1 instead of type-2 core, indicating that the linkage form of the lactosamine structure in N-glycan is influenced by the relative levels of β3- and β4-GalT expression41. Human type-1 lactosamine is thought to be synthesized by β3GalT-1, 2 or 542. In some cancers, high expression of β3GalT was associated with poor prognosis43,44. Therefore, this type-1 free-N-glycan may be the product of altered expression of a synthetic enzyme in the cancer cell.

At this point, the question arises as to whether the type-1 N-glycan having a Lewis B structure can be detected in its protein-bound form. To evaluate this question, we liberated N-glycans from glycoproteins derived from colorectal cancer cells in which type-1 N-glycan having a Lewis B moiety was detected as the major free-glycan, or from serum glycoproteins in patients with the highest urinary level of type-1 free-N-glycan with a Lewis B structure. The resulting glycan mixtures were then carefully analyzed. However, no type-1 N-glycans could be detected in the samples. Presumably in human, either type-1 N-glycan is not actively synthesized or is present in such small amounts that it is too difficult to detect. In one rare case, aberrant sialylation glycoproteins in the serum of a patient with a HNF1α variant and liver adenomatosis have been reported, suggesting that it is probably a type-1 N-glycan45. In addition, recent N-glycomes, generated using mass spectrometry, have shown the presence of N-glycan with a Lewis B/Y structure in human colorectal cancer cell lines and human intestinal enteroids, but it has yet to be determined whether it is a type-1 or type-2 lactosamine46,47. Nonetheless, a monoclonal antibody mAb-A4 that detects type-1 lactosamine and H type-1 showed binding to N-glycans of several ovarian cancer cell lines. However, the antibody was subsequently shown to bind type-1 lactosamine at the nonreducing terminal side of the polylactosamine of extended N-glycans, rather than to the mannose arm48.

At present, glycomics and glycoproteomics are rapidly advancing for the development of cancer diagnosis using liquid biopsy7,8. Additionally, N-glycome analysis for the development of bladder cancer diagnostic markers also utilize extracellular vesicles in urine49. Because cancer diagnosis using urine samples is non-invasive, we anticipate this approach will become more widespread.

In the present study, we detected a unique type-1 free-N-glycan having Lewis B as a cancer cell-specific glycan antigen. We evaluated its clinical usefulness for cancer screening by a method to noninvasively detect this free-glycan. Moreover, we measured the level of this glycan in urine samples from patients with various types of cancer. Currently, the mechanism of synthesis and significance of this rare and unique glycan structure detected in human cancer tissues is unknown. Nonetheless, a statistically significant difference was detected in cancer patient samples compared to healthy controls, with a particularly marked increase in some rare-types of cancer. The results of this study suggest further investigation into cancer diagnosis using type-1 free-N-glycan with Lewis B is warranted.

Methods

Patients

All human specimens were obtained from Osaka International Cancer Institute. Informed consent was obtained from all the volunteers and cancer patients. All experiments in this study were approved by the Local Ethics Committee of Osaka International Cancer Institute (no. 24047) and conducted in accordance with relevant guidelines and regulations.

Preparation of free-glycan from colorectal cancer cells and normal colorectal epithelial cells

The procedure used to prepare free-glycans from cell samples was as described in a previous paper10. In brief, the primary lesions of colorectal cancer tissues and their surrounding normal colorectal mucosa dissected from surgical specimens were treated with 2 mg/ml collagenase (Sigma-Aldrich, St Louis, MO, USA) in DMEM/F12 for 1 h at 37 °C. After washing in PBS supplemented with 10 mM EDTA, the cell mass was passed through 100 μm mesh. Flow-through cells were selected using magnetically labeled anti-CD326 microbeads (Miltenyi Biotec, Bergisch Gladbach, Germany) according to the manufacture’s protocol. The CD326 positive cells obtained from cancerous and normal tissues (1 × 106) were used for analysis. Free-glycans along with GSLs were extracted from CD326 positive cells with 1200 μl of chloroform/methanol (2:1, v/v), followed by 800 μl of chloroform/methanol/water (1.0:2.0:0.8, v/v/v). The extracts were loaded onto a DEAE-Sephadex A25 column, and flow-through fractions collected as neutral free-glycan and GSLs. Neutral fraction dissolved in chloroform/methanol (2:1, v/v) was precipitated with acetone at 4 °C overnight to remove cholesterol. The pellets were incubated in 0.1 M NaOH in chloroform/methanol/water (5:5:1, v/v/v) at 37 °C for 1 h and desalted by gel filtration on a HW-40C column (TOSOH, Tokyo, Japan) equilibrated with chloroform/methanol/water (5:5:1, v/v/v). Neutral GSLs and free-glycans were then treated with recombinant endoglycoceramidase II from Rhodococcus sp. (Takara Bio, Shiga, Japan) for GSL glycan recovery10. This is a convenient and useful method that allows comparison of the amount of free-glycans and GSL glycans. Neutral free-glycans and GSL glycans were labeled with 2-aminopyridine. The PA-glycan mixture was separated on a Shimadzu LC-20A HPLC system (Shimadzu, Kyoto, Japan). A detailed description of the conditions used for normal phase-HPLC and reversed phase-HPLC were reported previously (Table S5, (1) and (2))10.

Urine samples

Urine samples were obtained from cancer-free control volunteers (n = 121; female 59, male 62, mean age 64.49 years), patients with gastric cancer (n = 141; female 59, male 82, mean age 64.85 years), colorectal cancer (n = 87; female 48, male 39, mean age 62.37 years), pancreatic cancer (n = 55; female 23, male 32, mean age 63.84 years), bile duct cancer (n = 13; female 5, male 8, mean age 72.85 years) and rare cancer (n = 79; female 37, male 42, mean age 63.08 years) at the Osaka International Cancer Institute (OICI). None of the cancer patients were receiving anticancer drugs. Clinical information is shown in Table S3 and the subtypes of rare cancer patients enrolled in this study are listed in Table S4. All urine specimens were stored at − 80 °C until use.

Preparation and pyridylamination of free-glycans from urine samples

Free-glycans in urine were prepared as previously reported18,20. Briefly, urine specimens equivalent to 200 µg creatinine were spiked with internal standards (GlcNAc derivatives, GlcNGc) and purified by Dowex 50W-X8 (H+ form, 100–200 mesh, FUJIFILM Wako Pure Chemical, Osaka, Japan). Samples were then passed through a graphite carbon cartridge (InertSepGC 300 mg; GL Science, Tokyo, Japan). Eluates were used for labelling with 2-aminopyridine as previously reported50,51. PA-labelled glycans were subjected to phenol/chloroform extraction and cation exchange chromatography for removal of free 2-aminopyridine and then further purified on a graphite carbon cartridge (InertSepGC 150 mg; GL Science)52. The PA-glycan mixture was dissolved in 400 µl of water and stored at − 20 °C until measurement. It has been previously reported that long-term storage and freezing/thawing of urine samples do not affect the preparation of free-glycans20,53.

Glycan structural analysis

For glycosidase digestion, α1,3/4-l-fucosidase and Lacto-N-biosidase from Streptomyces sp.142 (Takara Bio) and α1,2-l-fucosidase and β1,3-galactosidase from Xanthomonas manihotis (New England Biolabs, Ipswich, MA, USA) were used in 1 × GlycoBuffer 1 (50 mM sodium acetate and 5 mM CaCl2 pH 5.5; New England Biolabs) with 1 × bovine serum albumin at 37 °C overnight. Authentic standard glycans were purchased from Takara Bio and prepared by enzymatic treatment as required. Gn1 type N-glycan having an α1,3-mannose arm extended β1,4 branching N-acetylglucosamine was prepared as described previously21.

The retention time of each PA-oligosaccharide is shown converted to glucose units based on the elution time of PA-isomaltooligosaccharides. The two glucose units obtained from the retention times of the amide and ODS columns were used to identify the glycan structures, corresponding to coordinates on the two-dimensional map.

Glycosidase digested products eluted by reversed phase-HPLC were analyzed using an LTQ XL linear ion trap mass spectrometer fitted with a HESI-II probe (Thermo Scientific, San Jose, CA, USA). PA-glycans were trapped on a InertSustain AQ-C18 column (3 μm, 1 × 100 mm; GL Sciences) and eluted with 50% acetonitrile, at a flow rate of 50 µl/min and a temperature of 35 °C (Table S5 (3)). The mass spectrometer parameters were set to positive-ion mode, as follows: sheath gas and auxiliary gas, 30 and 5 units; spray voltage, 3 kV; ion source temperature, 250 °C; ion transfer capillary temperature, 300 °C; tube lens voltage, 125 V. MS2 experiments were performed in data-dependent mode or by specifying the value of the precursor ion.

SRM for measurement of glycans

SRM was used to determine the glycan level as previously reported 20. Urinary PA-glycan mixtures corresponding to 10 μg of creatinine were separated on a Shim-pack Scepter C18-120 column (2.1 × 150 mm, 3 μm; Shimadzu) using a gradient from solvent A (10 mM acetic acid with triethylamine (pH 6.0)) to solvent B (10 mM acetic acid with triethylamine (pH 6.0) in 50% acetonitrile) at 35 °C (Table S5 (4)). The eluate was analyzed by electrospray ionization with post-column addition of acetonitrile using a 4500 QTRAP hybrid triple quadrupole/linear ion trap mass spectrometer (AB SCIEX, Framingham, MA, USA). Quality control mixtures, prepared from pooled urinary PA-glycan control samples, were analyzed every 15 runs to monitor the analysis. Data acquisition was performed with an ion spray voltage of 5 kV, curtain gas of 30 psi, collision gas of 9 psi, nebulizer gas (GS1) of 65 psi, turbo gas (GS2) of 55 psi, an interface heater temperature of 500 °C and dwell time of 50 ms. Two SRM transitions were monitored and acquired at low resolution both in the Q1 and Q3 quadrupoles. The respective values are shown in Table S6. SRM data acquired on the 4500 QTRAP were analyzed by SCIEX OS (AB SCIEX).

The validation of the SRM method for measurement of free-glycan was performed as previously reported (Figure S2)20. The urine specimen of the patient with a value below the LOQ for type-1 N-glycan having Lewis B was used as matrix. The standard type-1 N-glycan having Lewis B was prepared from the urinary specimen with the highest value. Each of the seven concentrations of standard glycan and IS were spiked with the urinary matrix to check for linearity. All analyses were repeated five times.

Data availability

All data generated or analyzed during the study are included either in this published article and its supplementary information file or can be made available from the corresponding author on reasonable request.

References

Chia, D. et al. Use of monoclonal antibodies to sialylated Lewisx and sialylated Lewisa for serological tests of cancer. Can. Res. 45, 435–437 (1985).

Del Villano, B. C. et al. Radioimmunometric assay for a monoclonal antibody-defined tumor marker, CA 19–9. Clin. Chem. 29, 549–552 (1983).

Taketa, K. & Hirai, H. Lectin affinity electrophoresis of alpha-fetoprotein in cancer diagnosis. Electrophoresis 10, 562–567. https://doi.org/10.1002/elps.1150100805 (1989).

Taketa, K. et al. Lectin-reactive profiles of alpha-fetoprotein characterizing hepatocellular carcinoma and related conditions. Gastroenterology 99, 508–518. https://doi.org/10.1016/0016-5085(90)91034-4 (1990).

Pinho, S. S. & Reis, C. A. Glycosylation in cancer: Mechanisms and clinical implications. Nat. Rev. Cancer 15, 540–555. https://doi.org/10.1038/nrc3982 (2015).

Koprowski, H. et al. Colorectal carcinoma antigens detected by hybridoma antibodies. Somatic Cell Genet. 5, 957–971. https://doi.org/10.1007/bf01542654 (1979).

Guo, Y., Jia, W., Yang, J. & Zhan, X. Cancer glycomics offers potential biomarkers and therapeutic targets in the framework of 3P medicine. Front. Endocrinol. 13, 970489. https://doi.org/10.3389/fendo.2022.970489 (2022).

Haga, Y. & Ueda, K. Glycosylation in cancer: Its application as a biomarker and recent advances of analytical techniques. Glycoconj. J. 39, 303–313. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10719-022-10043-1 (2022).

Korekane, H. et al. Novel fucogangliosides found in human colon adenocarcinoma tissues by means of glycomic analysis. Anal. Biochem. 364, 37–50. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ab.2007.01.034 (2007).

Misonou, Y. et al. Comprehensive clinico-glycomic study of 16 colorectal cancer specimens: elucidation of aberrant glycosylation and its mechanistic causes in colorectal cancer cells. J. Proteome Res. 8, 2990–3005. https://doi.org/10.1021/pr900092r (2009).

Shida, K. et al. Novel ganglioside found in adenocarcinoma cells of Lewis-negative patients. Glycobiology 20, 1594–1606. https://doi.org/10.1093/glycob/cwq108 (2010).

Tanaka-Okamoto, M. et al. Identification of internally sialylated carbohydrate tumor marker candidates, including Sda/CAD antigens, by focused glycomic analyses utilizing the substrate specificity of neuraminidase. Glycobiology 28, 247–260. https://doi.org/10.1093/glycob/cwy010 (2018).

Tanaka-Okamoto, M. et al. Correlation of serum sialyl Tn antigen values determined by immunoassay and SRM based method. Anal. Biochem. 544, 42–48. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ab.2017.12.026 (2018).

Tanaka-Okamoto, M. et al. Various sulfated carbohydrate tumor marker candidates identified by focused glycomic analyses. Glycobiology 27, 400–415. https://doi.org/10.1093/glycob/cww133 (2017).

Tanaka-Okamoto, M. et al. Elevation of CA19-9-related novel marker, core 1 sialyl lewis A, in sera of adenocarcinoma patients verified by a SRM-based method. J. Proteome Res. 15, 152–165. https://doi.org/10.1021/acs.jproteome.5b00893 (2016).

Yabu, M. et al. Occurrence of free deaminoneuraminic acid (KDN)-containing complex-type N-glycans in human prostate cancers. Glycobiology 23, 634–642. https://doi.org/10.1093/glycob/cws132 (2013).

Yabu, M. et al. Accumulation of free Neu5Ac-containing complex-type N-glycans in human pancreatic cancers. Glycoconj. J. 30, 247–256. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10719-012-9435-9 (2013).

Hanzawa, K. et al. Investigation of acidic free-glycans in urine and their alteration in cancer. Glycobiology 31, 391–409. https://doi.org/10.1093/glycob/cwaa100 (2021).

Hanzawa, K. et al. Increased levels of acidic free-N-glycans, including multi-antennary and fucosylated structures, in the urine of cancer patients. PLoS ONE 17, e0266927. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0266927 (2022).

Tanaka-Okamoto, M. et al. Combination of urinary free-glycan markers for the diagnosis of various malignant tumors. Sci. Rep. 15, 10109. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-94496-y (2025).

Tanaka-Okamoto, M. et al. Occurrence of a D-arabinose-containing complex-type free-N-glycan in the urine of cancer patients. Sci. Rep. 12, 4889. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-022-08790-0 (2022).

Noura, S. et al. Brain metastasis from colorectal cancer: Prognostic factors and survival. J. Surg. Oncol. 106, 144–148. https://doi.org/10.1002/jso.23055 (2012).

He, R. et al. Clinicopathologic and prognostic characteristics of alpha-fetoprotein-producing gastric cancer. Oncotarget 8, 23817–23830. https://doi.org/10.18632/oncotarget.15909 (2017).

Kono, K. et al. Clinicopathologic features of gastric cancers producing alpha-fetoprotein. Digestive Surg. 19, 359–365. https://doi.org/10.1159/000065838 (2002) (discussion 365).

Christensen, T. D., Spindler, K. L., Palshof, J. A. & Nielsen, D. L. Systematic review: Brain metastases from colorectal cancer–Incidence and patient characteristics. BMC Cancer 16, 260. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12885-016-2290-5 (2016).

Park, H. S. et al. Clinical features and KRAS mutation in colorectal cancer with bone metastasis. Sci. Rep. 10, 21180. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-020-78253-x (2020).

Lei, S. et al. Colorectal cancer metastases to brain or bone and the relationship to primary tumor location: A population-based study. J. Gastrointestinal Surg. 24, 1833–1842. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11605-019-04308-8 (2020).

Kukowska-Latallo, J. F., Larsen, R. D., Nair, R. P. & Lowe, J. B. A cloned human cDNA determines expression of a mouse stage-specific embryonic antigen and the Lewis blood group alpha(1,3/1,4)fucosyltransferase. Genes Dev. 4, 1288–1303. https://doi.org/10.1101/gad.4.8.1288 (1990).

Mollicone, R. et al. Molecular basis for Lewis alpha(1,3/1,4)-fucosyltransferase gene deficiency (FUT3) found in Lewis-negative Indonesian pedigrees. J. Biol. Chem. 269, 20987–20994. https://doi.org/10.1016/s0021-9258(17)31919-1 (1994).

Nishihara, S. et al. Molecular genetic analysis of the human Lewis histo-blood group system. J. Biol. Chem. 269, 29271–29278. https://doi.org/10.1016/s0021-9258(19)62041-7 (1994).

Narimatsu, H. et al. Genetic evidence for the Lewis enzyme, which synthesizes type-1 Lewis antigens in colon tissue, and intracellular localization of the enzyme. Can. Res. 56, 330–338 (1996).

Nishihara, S. et al. Molecular behavior of mutant Lewis enzymes in vivo. Glycobiology 9, 373–382. https://doi.org/10.1093/glycob/9.4.373 (1999).

Yazawa, S. et al. Genetic and enzymatic evidence for Lewis enzyme expression in Lewis-negative cancer patients. Can. Res. 55, 1473–1478 (1995).

Eckmair, B. et al. Glycosylation at an evolutionary nexus: The brittle star Ophiactis savignyi expresses both vertebrate and invertebrate N-glycomic features. J. Biol. Chem. 295, 3173–3188. https://doi.org/10.1074/jbc.RA119.011703 (2020).

Fitchette, A. C. et al. Biosynthesis and immunolocalization of Lewis a-containing N-glycans in the plant cell. Plant Physiol. 121, 333–344. https://doi.org/10.1104/pp.121.2.333 (1999).

Strasser, R. et al. A unique beta1,3-galactosyltransferase is indispensable for the biosynthesis of N-glycans containing Lewis a structures in Arabidopsis thaliana. Plant Cell 19, 2278–2292. https://doi.org/10.1105/tpc.107.052985 (2007).

Vanbeselaere, J., Jin, C., Eckmair, B., Wilson, I. B. H. & Paschinger, K. Sulfated and sialylated N-glycans in the echinoderm Holothuria atra reflect its marine habitat and phylogeny. J. Biol. Chem. 295, 3159–3172. https://doi.org/10.1074/jbc.RA119.011701 (2020).

Kimura, Y. et al. First evidence for occurrence of Galbeta1-3GlcNAcbeta1-4Man unit in N-glycans of insect glycoprotein: beta1-3Gal and beta1-4GlcNAc transferases are involved in N-glycan processing of royal jelly glycoproteins. Biosci. Biotechnol. Biochem. 67, 1852–1856. https://doi.org/10.1271/bbb.67.1852 (2003).

Sumiyoshi, W. et al. Hypersialylated type-I lactosamine-containing N-glycans found in Artiodactyla sera are potential xenoantigens. Glycobiology 22, 1031–1041. https://doi.org/10.1093/glycob/cws069 (2012).

Torii, T. et al. Determination of major sialylated N-glycans and identification of branched sialylated N-glycans that dynamically change their content during development in the mouse cerebral cortex. Glycoconj. J. 31, 671–683. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10719-014-9566-2 (2014).

Kotani, N., Asano, M., Iwakura, Y. & Takasaki, S. Knockout of mouse beta 1,4-galactosyltransferase-1 gene results in a dramatic shift of outer chain moieties of N-glycans from type 2 to type 1 chains in hepatic membrane and plasma glycoproteins. Biochem. J. 357, 827–834. https://doi.org/10.1042/0264-6021:3570827 (2001).

Petit, D., Teppa, R. E. & Harduin-Lepers, A. A phylogenetic view and functional annotation of the animal β1,3-glycosyltransferases of the GT31 CAZy family. Glycobiology 31, 243–259. https://doi.org/10.1093/glycob/cwaa086 (2021).

Kuo, H. H. et al. High expression FUT1 and B3GALT5 is an independent predictor of postoperative recurrence and survival in hepatocellular carcinoma. Sci. Rep. 7, 10750. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-017-11136-w (2017).

Liao, Y. M. et al. High B3GALT5 expression confers poor clinical outcome and contributes to tumor progression and metastasis in breast cancer. Breast Cancer Res. BCR 23, 5. https://doi.org/10.1186/s13058-020-01381-9 (2021).

Sturiale, L. et al. Aberrant sialylation in a patient with a HNF1α variant and liver adenomatosis. iScience 24, 102323. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.isci.2021.102323 (2021).

Nilsson, J. et al. N-glycoproteomic analyses of human intestinal enteroids, varying in histo-blood group geno- and phenotypes, reveal a wide repertoire of fucosylated glycoproteins. Glycobiology https://doi.org/10.1093/glycob/cwae029 (2024).

Wang, D. et al. In-depth analysis of the N-glycome of colorectal cancer cell lines. Int. J. Mol. Sci. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijms24054842 (2023).

Choo, M. et al. Characterization of H type 1 and type 1 N-acetyllactosamine glycan epitopes on ovarian cancer specifically recognized by the anti-glycan monoclonal antibody mAb-A4. J. Biol. Chem. 292, 6163–6176. https://doi.org/10.1074/jbc.M116.768887 (2017).

Li, Y. et al. Urinary extracellular vesicle N-glycomics identifies diagnostic glycosignatures for bladder cancer. Nat. Commun. 16, 2292. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41467-025-57633-9 (2025).

Hase, S., Ikenaka, T. & Matsushima, Y. Structure analyses of oligosaccharides by tagging of the reducing end sugars with a fluorescent compound. Biochem. Biophys. Res. Commun. 85, 257–263. https://doi.org/10.1016/s0006-291x(78)80037-0 (1978).

Kuraya, N. & Hase, S. Release of O-linked sugar chains from glycoproteins with anhydrous hydrazine and pyridylamination of the sugar chains with improved reaction conditions. J. Biochem. 112, 122–126. https://doi.org/10.1093/oxfordjournals.jbchem.a123850 (1992).

Natsuka, S., Hirohata, Y., Nakakita, S., Sumiyoshi, W. & Hase, S. Structural analysis of N-glycans of the planarian Dugesia japonica. FEBS J. 278, 452–460. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1742-4658.2010.07966.x (2011).

Auray-Blais, C. et al. Efficient analysis of urinary glycosaminoglycans by LC-MS/MS in mucopolysaccharidoses type I, II and VI. Mol. Genet. Metab. 102, 49–56. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ymgme.2010.09.003 (2011).

Funding

This work was supported in part by Grant-in-Aid for Scientific Research (C) no. 23K06880 from the Ministry of Education, Culture, Sports, Science and Technology of Japan, Research Grant from Nakatani Foundation, and Medical Research Grant Program (A), Osaka Foundation for the Prevention of Cancer and Cardiovascular Diseases.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

M. T-O., K. H. and Y. M. conceived the study, designed the experiments, analyzed and interpreted the data. M. T-O. wrote the first draft of the manuscript. T. Yamamoto, K. O., K. Y., S. T., M. O. and T. Yamasaki collected study material. Y. M. reviewed and edited the manuscript. All authors reviewed the final manuscript.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher’s note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Supplementary Information

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if you modified the licensed material. You do not have permission under this licence to share adapted material derived from this article or parts of it. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Tanaka-Okamoto, M., Hanzawa, K., Yamamoto, T. et al. Identification of a free-N-glycan with difucosylated type-1 lactosamine in cancerous tissue and its validation for cancer diagnosis by urinary testing. Sci Rep 15, 33592 (2025). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-18781-6

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-18781-6