Abstract

The design of high-performance marathon running shoes plays a critical role in optimizing energy return, reducing fatigue, and enhancing comfort for elite athletes. A comprehensive understanding of the internal deformation mechanisms within these complex, multi-material structures is essential for developing new strategies to optimize their performance under realistic loading conditions. In this study, we have integrated x-ray micro-computed tomography (XCT) and digital volume correlation (DVC) to investigate the internal mechanics of a marathon shoe’s stiffening element, a critical component used for optimization of energy return and stability to the athlete. Using XCT, we non-destructively imaged the shoe’s internal architecture, revealing the intricate geometry of midsole and the stiffening elements within the sole of the shoe. Using a unique 3D printed bending frame, were able to deform the midsole of the shoe and used DVC analyses to quantify the three-dimensional displacement and strain fields under the simulated loading conditions. Our results demonstrate that localized strain patterns near the metatarsophalangeal joint can be used to accurately replicate and understand the foot’s natural biomechanics during propulsion. By bridging advanced imaging techniques and computational modeling, this research provides actionable insights for the rapid prototyping of next-generation marathon shoes. The findings and frameworks discussed here help contribute to optimizing performance, setting a new standard for athletic footwear design tailored to the rigorous demands of endurance running.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

The development of high-performance running shoes has become a cornerstone of innovation in competitive sports, especially in elite marathon events, where innovations in shoe materials and design can translate into a significant competitive advantage1. Advances in materials engineering, biomechanics, and computational modeling have enabled the creation of shoes designed to optimize energy return, enhance comfort, and mitigate fatigue2. Just as past advancements were driven by novel experimental techniques, future breakthroughs in these multi-material structures can be expected to emerge from fundamental understanding of their microscopic deformation mechanisms. In this context, x-ray micro-computed tomography (XCT) and digital volume correlation (DVC) can be leveraged as powerful tools, offering fundamental insights into the mechanical behavior of running shoes.

X-ray micro-computed tomography (XCT) has proven invaluable in materials science for characterizing the internal structures of complex materials3. Its ability to provide high-resolution, three-dimensional (3D) imaging of heterogeneous materials is particularly well-suited for analyzing the intricate microstructure and localized deformation in the midsole of marathon shoes. Elite marathon running shoes typically feature a sophisticated combination of foams, textiles, and polymer composites, often enhanced with cutting-edge components like carbon fiber plates and supercritical foams4. By enabling high-resolution visualization of the microstructures and their deformation under loading, time-resolved or four-dimensional XCT (4D XCT) can provide critical information on how these materials behave. Furthermore, unlike destructive imaging techniques, non-destructive micro-CT approach preserves the specimen’s shape and morphology, allowing for repeated imaging and testing, which is essential for iterative design and evaluation. Despite its numerous advantages, to the best of the authors’ knowledge, no studies in the existing literature have utilized 4D XCT to investigate the deformation mechanisms of marathon shoes.

While 3D micro-CT data has been used to understand the structure of footwear materials and athletic gear5,6,7,8,9as well as the structure of the entire shoe9,10extracting quantitative deformation data from 4D micro-CT datasets can be challenging. Digital Volume Correlation (DVC) provides a highly effective and reliable method for achieving this goal11,12,13,14,15. The DVC technique enables the calculation of displacement and strain fields by comparing three-dimensional XCT datasets captured at different states of deformation. Through voxel (3D pixel) -level correlation, DVC enables the measurement of localized strain distributions and deformations offering insights into the mechanics of deformation at a microscopic level. For instance, for the case of a marathon shoe, DVC can reveal how strains are distributed across the midsole, outsole, upper materials of a shoe as well as embedded stiffening elements that help in optimizing energy return. This data not only helps designers understand the mechanical coupling between different components of an elite running shoe but also provides critical information for optimizing material properties and geometries to enhance performance through factors such as cushioning, energy return, and durability. Further, the experimental insight from XCT and DVC can also prove to be critical for validating the finite element models that are increasingly used to accelerate design cycles, ensuring that simulations accurately reflect real-world mechanics.

The synergistic use of micro-CT and DVC represents a transformative approach to studying sports footwear, offering a comprehensive, non-destructive methodology to investigate deformation mechanisms. This tandem approach offers distinct advantages, such as enabling non-destructive iterative testing of the same specimen, facilitating multi-scale analysis by connecting material microstructure with macroscopic performance, and accelerating the development of new designs through 3D microstructural evaluations. These benefits are particularly relevant to elite marathon athletes, where shoes play a critical role in performance1,16. Therefore, in this study, we have utilized x-ray micro-CT and Digital Volume Correlation (DVC) to explore the deformation mechanisms of marathon shoes under realistic loading conditions. To simulate these conditions, we employed unique, custom-designed 3D-printed bending frames, which enable deformation of the midsole in biomechanically relevant ways. The deformed midsoles were then scanned using a lab-scale x-ray microscope, capturing high-resolution 3D tomographic data. Subsequently, using DVC, we analyzed the XCT data from both deformed and undeformed midsoles to calculate the displacement and strain fields within the carbon-fiber rods (stiffening elements) embedded in the midsole. Furthermore, we compared the displacement and strain fields resulting from the different bending frame configurations, highlighting how certain frames more accurately replicate realistic deformation patterns.

Materials and methods

This section provides a comprehensive overview of the marathon shoe, including its key features and relevance to the study. We describe the design and use of custom loading frames, which deform the shoe into specific shapes that simulate real-world conditions, making them suitable for XCT scanning. The X-ray Computed Tomography (XCT) system used for capturing high-resolution scans is then described. Finally, we explore the Digital Volume Correlation (DVC) analysis technique, which is employed to quantify deformation and strain fields within the shoe samples.

Marathon shoe sample

The Adidas Adizero Adios Pro 3 running shoe was studied in this work. These marathon shoes have a lightweight stiffening element embedded into the midsole of the shoe. Composed primarily of a carbon fiber infused polymer resin, the embedded stiffening element is lightweight and stiff, thereby enhancing the athlete’s running economy. Figure 1a shows an image of the marathon running shoe in its intact form. In this work, we focused on examining the deformation characteristics of the stiffening element under various boundary conditions. These conditions were simulated using different bending frames, with x-ray Computed Tomography employed to capture detailed structural responses. Therefore, prior to scanning the shoe using the XCT scanner, the fabric upper of the shoe was removed by carefully cutting the fabric where it connects with the midsole – ensuring that the midsole was not damaged during the cutting process. Figure 1b and c show the top and the side views of the sole, respectively, prior to insertion in the frame and scanning. Note that while this initial preparation step is destructive to the fabric upper part of the shoe, the subsequent XCT imaging and DVC analysis of the midsole component is entirely non-destructive. This approach preserves the specimen’s integrity, enabling iterative testing of the same sample under different loading condition.

Running shoe used for current study: (a) Adidas Adizero Adios Pro 3 shoe sample (size UK 5.5) showing the misole and fabric upper, (b) top view of the sole of the Adizero shoe sample with the fabric upper removed to facilitate X-ray Computed Tomography scans showing the insole and the midsole of the shoe, (c) side view of the bottom unit showing the insole, outsole, and midsole of the shoe sample. The shoe has an embedded stiffenning element that is captured in 3D using XCT scanning.

Loading frames for bending experiments

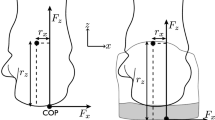

After cutting off the fabric upper, the bottom unit of the shoe – the outsole and insole were kept attached to the midsole – was inserted into the bending frame, see Fig. 2a. The bending frames were 3D printed using a Lulzbot Taz FDM Printers with a 3 mm diameter Hatchbox PLA printer filament. Each bending frame consisted of a front and back segment, with its size and thickness carefully optimized to minimize material usage while preserving the necessary stiffness to effectively bend the sole sample. The front and back bending frames were connected using a metal tie at the top and bottom of the bending frames. The positioning of the metal tie ensured that they did not interfere with the x-ray imaging. As shown in Fig. 2b and c, two bending frame shapes were adopted. The first bending frame, the reference bending frame or bending frame 1 (BF1), was shaped in the form of a curved surface. In addition to this frame, another frame was designed and built, bending frame 2 (or BF2), which was shaped in the form of a sledge with a flat surface near the heel, followed by an inclined surface at an angle of 15° to the flat surface near the toe of the sole. BF2 was designed to mimic the bending of the foot at the metatarsophalangeal (MTP) joint with an angle of 15° to simulate the approximate angle at which the foot bends when running17.

Bending frames were used to simulate the distortion of the midsole under different conditions: (a) image showing the curved bending frame with the midsole sandwiched in between the front (in contact with insole) and back frames (in contact with outsole) and held together using metal ties away from the region being scanned in the X-ray Microscope, (b) Bending Frame – I (BF1) has a curved inner and outer frame; the curved frame may not be very accurate in the capturing of the bending of the foot, therefore (c) another bending frame (BF2) was used to mimic the bending of the foot at the metatarsophalangeal (MTP) joint with an angle of 15° to simulate the angle at which the foot bends when running17.

X-ray computed tomography (XCT)

Once the sole sample was placed inside the bending frames, the assembled frame and sole sample were placed inside an x-ray microscope (VERSA 620, Zeiss Dublin CA). The bending frame and sole sample assembly were scanned at a source voltage of 60 kV, 6.5 W using the Flat panel detector at a scanning resolution of 100 μm/voxel. Scanning conditions and resolution were chosen to optimize the contrast between the different phases within the sole sample, while at the same time capturing the entire sample. Due to the elongated shape of the sole sample, the scan was carried out by vertically “digitally stitching” the XCT data from upper and lower half of the shoe. For each half, a total of 1600 projections were captured during the XCT scans with an exposure time of 0.5 s, results in a total scan time of approximately 1 h. A total of three scans were carried on the sole sample: one under undeformed conditions and two scans under deformed conditions – in the two bending frames. The first scan under undeformed conditions was taken as the reference dataset and two scans under the deformed conditions were analyzed using XCT to capture deformation of the sample using Digital Volume Correlation analyses.

Digital volume correlation (DVC) analyses

Digital Volume Correlation (DVC) is a technique used to measure 3D displacement and strain fields from XCT datasets11,12,15. As described in Fig. 3, DVC works by comparing a reference (undeformed) volume with a deformed volume, identifying corresponding features across the two datasets. DVC employs a computational grid to divide the volume into sub-volumes or subsets, tracking their deformation by maximizing a correlation function. Local DVC analyzes deformation at the subset level, allowing high spatial resolution but may be sensitive to noise and less accurate in capturing global continuity12. Global DVC uses a single optimization over the entire volume, enforcing physical constraints and ensuring smoothness but requiring higher computational power15. The analyses presented in this paper was carried out in the DVC module in the commercial software Avizo (Thermo Fisher Scientific, St Bend OR). In Avizo, DVC is performed by importing the XCT datasets, defining regions of interest, setting correlation parameters, and computing displacement fields using either local or global methods, often with interactive visualization of the results. The current samples were initially analyzed using a local DVC approach to get a coarse assessment of the displacement field. After the initial local DVC analyses, the output from the local DVC analyses was used as a starting point for the global DVC analyses. After completion of the global DVC analyses, the displacement and strain fields for the stiffening element were calculated for the two deformation conditions.

Digital Volume Correlation (DVC) analysis is a technique used to measure and quantify the internal deformation of materials by comparing two volumetric datasets obtained at different states or time steps. A sub-volume from a reference dataset at Time Step 1 is tracked and matched to its corresponding deformed position in a subsequent dataset at Time Step 2, yielding displacement and strain fields. The approach relies on correlating grayscale intensity patterns within sub-volumes across 3D datasets. When applied to X-ray Computed Tomography (XCT) data of the Marathon Midsole sample, DVC allows non-destructive, high-resolution characterization of internal material deformation and strain evolution during mechanical loading (modified after Chawla and Ganju3.

Results and discussion

This section begins with an examination of the internal structure of the shoe, followed by a presentation of the DVC analysis results and the displacement fields obtained from the bending experiments. Lastly, we explore the internal strain fields during bending.

Internal structure of running shoe

Figure 4 shows the internal structure of the marathon shoes. In Fig. 4a, we see the 3D rendering of the structure of the shoe sample, while Fig. 4b shows a rendering of the stiffening element within the midsole. From Fig. 4b we can see that the stiffening element has a unique shape. The stiffening element is a 3D structure with intertwined, elongated strands forming a symmetrical, looped arrangement at the top (heel section) and flaring outward at the bottom (toe section) into 5 “fingers.” The intersecting lines have a braided or woven configuration, making it a multi-functional and unique compared to stiffening plates used in other running shoes.

Visualization of the internal structure of a running shoe using X-ray computed tomography: (a) 3D translucent rendering of the midsole, viewed from the insole side, highlighting the positions of the heel and toe along with the placement of the stiffening element within the shoe; (b) detailed 3D rendering of the stiffening element, showing its shape and design, obtained through interactive thresholding of the corresponding voxels.

Stiffening element deformation

As previously noted, two different bending frames were utilized to evaluate the varying deformation characteristics of the stiffening element within the midsole of the marathon shoe. Figure 5 illustrates the deformation and bending of a stiffening element in the shoe during simulated motion. In Fig. 5a, the stiffening element transitions from an undeformed state (blue) to progressively bent configurations (frames 1 and 2, shown in red and green, respectively). These frames mimic the bending that occurs during running, particularly when the foot pushes off the ground. Figure 5 (b) highlights the areas of maximum bending in the stiffening element as it conforms to the bending frame used to mimic the foot’s motion. By using the bending captured in frame #2, it was possible to closely replicate the shape the stiffening element takes during a runner’s stride. This is critical for mimicking the natural biomechanics of the foot, as the stiffening element supports propulsion while minimizing energy loss17. Note that to establish a reference, the deformation of all three samples was measured with the heel in a consistent, aligned position.

The deformation field analysis of the stiffening element reveals its evolution from the undeformed state (blue) to Frame 1 (red) and Frame 2 (green), with Frame 1 representing an intermediate deformation state and Frame 2 closely resembling the natural curvature of the foot during running (To establish a reference, the deformation of all three samples was measured with the heel in a consistent, aligned position): (a) The bending deformation is concentrated near the metatarsophalangeal (MTP) joint, characterized by significant curvature changes in Frame 2; (b) this localized bending mimics the biomechanics of the foot during the push-off phase of running, where the MTP joint plays a vital role in energy transfer and propulsion. The analysis underscores the structural adaptability of the stiffening element, demonstrating its ability to meet the functional demands of foot motion during dynamic activities, particularly in high-stress regions like the MTP joint.

One analysis was carried out for each of the two bending frames shown in Fig. 2. Figure 6a-d shows the four steps for the Digital Volume Correlation analyses. The process begins with the acquisition of high-resolution XCT images of the sample in both its reference (undeformed) state and deformed states. These datasets serve as the input for the analysis. A region of interest (ROI) is defined within the 3D volumes to focus on areas where deformation occurs. The analysis progresses through two main stages: local DVC and global DVC.

In the first stage, local DVC analysis divides the ROI into 12 cubic sub-volumes or subsets. Grayscale intensity patterns within these subsets in the reference volume are compared with those in the deformed volume, tracking the movement of the subsets by identifying the best match through a correlation coefficient12. This approach provides a preliminary displacement field albeit with a relatively coarse spatial resolution. Further, since each sub-volume is treated independently, local DVC does not ensure continuity in the deformation field and is more susceptible to noise15.

The second stage employs global DVC analysis, which uses the displacement field from local DVC as an initial estimate. Unlike local DVC, global DVC applies a single optimization process over the entire region of interest (ROI), incorporating physical constraints such as continuity and smoothness to refine the displacement field. This method leverages continuum mechanics-based models to ensure that the deformation results are physically accurate and globally consistent across the ROI. Although more computationally demanding, global DVC produces high-resolution displacement and strain fields that reflect the material’s true behavior under loading. For further discussions on the mathematical aspects of the global DVC, the reader is directed to the paper by Madi et al.15 in which the authors discuss the local and global DVC technique as applied to deformation in porous implants.

The outputs of the DVC analysis include detailed displacement and strain maps, which can be visualized in 3D to reveal regions of localized deformation. By combining the initial resolution of local DVC with the refinement and physical accuracy of global DVC, this methodology provides a comprehensive understanding of material deformation. To ensure the validity of the displacement field obtained from DVC analyses, the distance was manually measured from the XCT data and compared to the displacement field obtained from DVC. Figure 6e shows good agreement between the DVC approach and manually measured vertical displacement in the stiffening element near the toe region.

Strains in stiffening element

Capturing the strain in the deformed stiffening element provided valuable insights into the stress distribution, flexibility, and material performance under dynamic conditions. Such analyses allow for the optimization of materials, geometry, and stiffness of these elements, enabling the design of more efficient and durable stiffening components in marathon shoes. These advancements can improve energy return, reduce fatigue, and enhance overall running performance, particularly in endurance events like marathons.

Overview of the four stages of Digital Volume Correlation (DVC) analysis for the stiffening element: (a) Heel-aligned samples ensure consistent positioning of the stiffening element geometry; (b) Coarse local DVC analyses identify large-scale deformation patterns; (c) Fine global DVC analyses refine displacement fields from local DVC using higher-resolution voxel data; (d) 3D strain and displacement maps provide high-resolution quantification of the mechanical response; (e) Vertical displacement visualization shows localized deformation, with vertical movements ranging from 0 mm to 17 mm, peaking near the heel.

Figure 7 illustrates strain distribution maps for a stiffening element under deformed conditions in the two different bending frames, emphasizing how the choice of bending frame affects the deformation patterns. In Fig. 7a, corresponding to BF1, the strain is diffused along the entire length of the stiffening element in the metatarsophalangeal (MTP) joint region. This uniform distribution indicates that the element experiences more gentle deformation, which does not align closely with the specific bending behavior of the foot during running. Conversely, in Fig. 7b, which corresponds to BF2, the strain is highly localized near the metatarsophalangeal (MTP) joint. This localization in strain is more relevant as the MTP region is where the foot naturally bends during propulsion, showing that frame #2 more accurately replicates real-world running conditions.

The distinction between diffused and localized strain patterns has critical implications for the design of marathon shoe stiffening elements. In frame #1, the diffused strain suggests a less biomechanically accurate deformation pattern. However, the localized strain in frame #2 near the MTP joint demonstrates how the stiffening element can effectively adapt to the foot’s natural mechanics, particularly during the toe-off phase of running18. This highlights the importance of selecting the correct bending frame to study deformation, as it directly impacts the ability to design optimized stiffening elements that enhance running performance.

Using bending frame #2, which closely mimics the foot’s deformation during running, provides actionable data for improving the design of stiffening elements in marathon shoes. Specifically, this data can inform material selection, geometry optimization, and placement of the stiffening element within the shoe midsole to achieve several benefits. Additionally, the strain map from frame #2 helps ensure that the stiffening element supports the natural bending motion of the foot, aligning with biomechanical needs.

Therefore, strain mapping insights play a pivotal role in injury prevention. A well-designed stiffening element can effectively distribute stresses, particularly around the metatarsophalangeal (MTP) joint, a critical area susceptible to overloading during running. Using high-resolution 3D tomographic data of the athlete’s foot within the shoe, this research underscores the importance of biomechanically accurate bending frames, such as frame #2, for studying deformation in stiffening elements of marathon shoes. By replicating realistic deformation patterns, this approach ensures that the stiffening elements are optimized for performance, comfort, and durability. Such research is instrumental in developing next-generation marathon shoes that enhance energy efficiency, safeguard athletes, and elevate overall running performance.

Strain distribution maps of the stiffening element during bending: (a) The strain map for Frame 1 shows diffused strain distribution throughout the structure, with relatively low strain near the heel and toe regions. This diffused strain suggests that deformation is more evenly distributed across the stiffening element in this intermediate bending stage; (b) The strain map for Frame 2 reveals more localized strain, particularly concentrated near the metatarsophalangeal (MTP) joint, where the structure experiences significant curvature during bending in the bending frame 2. The localized strain in Frame 2 aligns with the bending of the foot during running, where the MTP joint acts as a critical point for energy transfer and propulsion. In both frames, strain remains minimal near the heel and toe, reflecting structural stability in these regions.

Perspectives on XCT and multimodal analyses for athletic gear development

This research presents a comprehensive and innovative framework for understanding the mechanics and development of marathon shoes by integrating advanced imaging techniques, material analysis, and simulation-driven optimization. The study focuses on understanding the behavior of the internal stiffening element embedded within the shoe’s midsole under realistic deformation conditions, utilizing x-ray Computed Tomography (XCT) and Digital Volume Correlation (DVC) analysis. By combining these methodologies, the research bridges the gap between visual experimental observation and quantitative characterization of strains in the marathon shoes, offering a robust approach for the rapid co-design of shoes and their components to enhance athletic performance.

A key aspect of the study is the use of XCT for non-destructive, high-resolution 3D imaging of the internal components of the shoe, particularly the stiffening element. XCT enables detailed visualization of the stiffening element’s intricate geometry and structural arrangement. This data is critical for understanding how the element interacts with the foot during running. Time-resolved XCT studies further enrich the understanding of the stiffening element’s behavior under simulated loading conditions. The use of bending frames that mimic different foot motions during running enables the investigation of strain distribution and deformation. Bending frame #2, designed to replicate the bending of the foot at the metatarsophalangeal (MTP) joint, proves particularly insightful. It demonstrates localized strain near the MTP joint, a critical region for propulsion during the toe-off phase. This realistic simulation captures the mechanical response of the stiffening element under dynamic conditions, providing valuable insights into its fatigue behavior and long-term durability. The study’s ability to identify high-stress regions and potential failure zones is crucial for optimizing the design of stiffening elements to enhance performance and longevity.

The XCT-derived data can be instrumental in validating FEM simulations19,20,21which predict the deformation and stress response of the shoe under various conditions. Future studies can help further marathon shoe development by comparing the experimentally observed strain fields from DVC analyses with FEM-predicted deformation. Such studies will ensure that the computational models accurately reflect real-world behavior. This validation step enhances the predictive power of FEM simulations, enabling faster and more reliable design iterations without the need for extensive physical prototyping. Such future work, relying on the coherent integration of XCT, DVC, and FEM, will help establish a pathway for rapid co-design of running shoes, where material properties, geometry, and placement of the stiffening element can be optimized simultaneously. Insights from strain mapping allow the tailoring the stiffness, weight, and durability of the stiffening element to meet specific athlete needs. This iterative approach ensures that each design iteration improves key performance metrics, such as energy return and running efficiency. By mimicking realistic foot motions, the study addresses the critical challenge of designing shoes that align with the biomechanics of the foot, especially for endurance events like marathons where marginal gains in performance can significantly impact outcomes.

Furthermore, this framework provides the foundational data necessary to tackle the inverse design problem: rather than analyzing a known geometry, future efforts can aim to computationally generate novel designs based on prescribed performance criteria. The strain and displacement fields obtained from XCT and DVC can serve as benchmark data for validating computationally generate designs with prescribed boundary, loading, and deformation conditions. By defining desired outcomes—such as specific energy return profiles, targeted stiffness at the MTP joint, or minimal stress concentrations—these advanced computational tools could predict optimal stiffening element geometries and material compositions. This shift from analysis to synthesis represents the next frontier in athletic footwear, enabling the creation of bespoke, high-performance components tailored not just to an event, but to an individual athlete’s unique biomechanics.

Conclusions

This study successfully demonstrated the integration of X-ray micro-computed tomography (XCT) and digital volume correlation (DVC) to analyze the deformation mechanisms of carbon-fiber stiffening element embedded in marathon running shoes under realistic loading conditions. XCT data provided high-resolution, three-dimensional imaging of the internal structure of the shoe, enabling non-destructive visualization of the stiffening element’s geometry and mechanical behavior. DVC helped quantify three-dimensional strain and displacement fields, offering detailed insights into how the stiffening element responds to biomechanically relevant deformation patterns. Key conclusions from this work include:

1. XCT as a Non-Destructive Tool: XCT enabled the detailed visualization of the internal geometry of the shoe’s stiffening element without compromising the structural integrity of the sample, facilitating iterative testing and analysis.

2. DVC for Quantitative Deformation Analysis: DVC provided precise, voxel-level mapping of strain distributions within the stiffening element, revealing localized deformation patterns that align closely with real-world biomechanics.

3. Importance of Well-Designed Experimental Fixtures to Replicate Running Mechanics: The use of a biomechanically accurate bending frame (Frame #2) enabled the replication of natural foot motion during propulsion, highlighting its critical role in capturing realistic deformation and strain behavior.

4. Insights for Shoe Design: Strain mapping demonstrated how the stiffening element supports efficient energy transfer and adapts to foot biomechanics, providing actionable data for optimizing energy return, comfort, and durability in marathon shoes.

Building on the framework established in this study, future research can focus on several key areas. Incorporating real-world foot-shoe interaction data using Finite Element Method based simulations with XCT and DVC for validation could provide deeper insights into the stress localization and deformation behavior of shoes during athlete use. The integration of XCT-DVC data into finite element models (FEM) can enhance the accuracy of predictive simulations, accelerating the development of optimized designs. Studies on the fatigue behavior of stiffening elements under repetitive loading conditions, akin to marathon running, would be valuable for improving durability and to understand key failure points within the shoe. While our current ex-situ analysis provides critical insights at discrete deformation states, future work could employ time-resolved 4D XCT to capture the continuous evolution of strain during a dynamic bending cycle. Such in-situ experiments would allow for the characterization of nonlinear material behavior and provide an even more comprehensive understanding of the shoe’s biomechanical response. Extending the analysis to include multi-component interactions between the midsole, outsole, and upper materials can provide a holistic understanding of shoe performance. Additionally, this framework can be applied to custom shoe designs tailored to individual biomechanics, as well as to other sports footwear and high-performance materials, broadening the impact of this innovative methodology.

Data availability

Some of the data presented in this paper is available from the corresponding author upon reasonable request.

References

Frederick, E. C. Let’s just call it advanced footwear technology (AFT). Footwear Sci. 14, 131–131. https://doi.org/10.1080/19424280.2022.2127526 (2022).

Hoogkamer, W. et al. A comparison of the energetic cost of running in marathon racing shoes. Sports Med. 48, 1009–1019. https://doi.org/10.1007/s40279-017-0811-2 (2017).

Chawla, N. & Ganju, E. 4D Materials Science: Time Resolved X-ray Microcomputed Tomography MRS Bulletin Accepted (2025).

Zhou, Y., Tian, Y. & Peng, X. Applications and challenges of supercritical foaming technology. Polym. (Basel). 15 https://doi.org/10.3390/polym15020402 (2023).

Singaravelu, A. S. S. et al. In situ X-ray microtomography of the compression behaviour of eTPU bead foams with a unique graded structure. J. Mater. Sci. 56, 5082–5099. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10853-020-05621-3 (2020).

Singaravelu, A. S. S. Deformation behavior of adidas BOOST™ foams using In Situ X-ray Tomography and Correlative Microscopy, Arizona State University, (2020).

Lumafield. 2004, Summer Olympics Super Shoes, https://www.lumafield.com/article/2024-summer-olympics-super-shoes-nike-alphafly-3-and-adidas-adizero-adios-pro-evo-1 (2024).

Lumafield The Engineer’s Guide to Athletic Equipment Defects, (2024). https://voyager.lumafield.com/projects

Lumafield XCT datasets of Athletic Gear, (2024). https://voyager.lumafield.com/projects

Wittmann, J., Herl, G. & Hiller, J. Generation of a 3D model of the inside volume of shoes for e-commerce applications using industrial x-ray computed tomography. Eng. Res. Express. 3 https://doi.org/10.1088/2631-8695/ac43c8 (2021).

Smith, T. S., Bay, B. K. & Rashid, M. M. Digital volume correlation including rotational degrees of freedom during minimization. Exp. Mech. 42, 272–278. https://doi.org/10.1007/bf02410982 (2002).

Bay, B. K., Smith, T. S., Fyhrie, D. P. & Saad, M. Digital volume correlation: Three-dimensional strain mapping using X-ray tomography. Exp. Mech. 39, 217–226. https://doi.org/10.1007/bf02323555 (1999).

Leclerc, H., Périé, J. N., Roux, S. & Hild, F. Voxel-Scale digital volume correlation. Exp. Mech. 51, 479–490. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11340-010-9407-6 (2010).

Hild, F. et al. Toward 4D mechanical correlation. Adv. Model. Simul. Eng. Sci. 3 https://doi.org/10.1186/s40323-016-0070-z (2016).

Madi, K. et al. Computation of full-field displacements in a scaffold implant using digital volume correlation and finite element analysis. Med. Eng. Phys. 35, 1298–1312. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.medengphy.2013.02.001 (2013).

Rodrigo-Carranza, V. et al. Impact of advanced footwear technology on critical speed and performance in elite runners. Footwear Sci. 15, 9–15. https://doi.org/10.1080/19424280.2022.2164624 (2023).

Hoogkamer, W., Kipp, S. & Kram, R. The biomechanics of competitive male runners in three marathon racing shoes: A randomized crossover study. Sports Med. 49, 133–143. https://doi.org/10.1007/s40279-018-1024-z (2019).

Sichting, F., Holowka, N. B., Hansen, O. B. & Lieberman, D. E. Effect of the upward curvature of toe springs on walking biomechanics in humans. Sci. Rep. 10, 14643. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-020-71247-9 (2020).

Cheung, J. & Zhang, M. in ABAQUS users’ conference. 145–158.

Li, Y., Leong, K. F. & Gu, Y. Construction and finite element analysis of a coupled finite element model of foot and barefoot running footwear. Proc. Institution Mech. Eng. Part. P: J. Sports Eng. Technol. 233, 101–109. https://doi.org/10.1177/1754337118803540 (2018).

Song, Y., Shao, E., Biro, I., Baker, J. S. & Gu, Y. Finite element modelling for footwear design and evaluation: A systematic scoping review. Heliyon 8, e10940. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.heliyon.2022.e10940 (2022).

Acknowledgements

EG and NC acknowledge continued support for this research through adidas AG.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

Please see manuscript.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher’s note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if you modified the licensed material. You do not have permission under this licence to share adapted material derived from this article or parts of it. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Ganju, E., Hanson, H., Wormser, M. et al. Deformation mechanisms in marathon running shoes elucidated by X-ray micro-computed tomography and digital volume correlation analysis. Sci Rep 15, 40679 (2025). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-19043-1

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-19043-1