Abstract

Triple-negative breast cancer (TNBC) is an aggressive subtype lacking ER, PR, and HER2 receptors making it highly clinically challenging subtype pf breast cancer. In this study, we investigated the effect of exogenous Kisspeptin-10 (Kp-10), on MDA-MB-231 and MDA-MB-468 cells. TNBC cells using both in vitro and in silico approaches. Kp-10 treatment significantly reduced cell viability and migration and induced a dose-dependent upregulation of KISS1 mRNA, suggesting a positive feedback loop. Alongside this, Kp-10 modulated key transcription factors—upregulating GATA2, CDX2, and FLI1 while downregulating ZEB1—indicating a shift towards a less aggressive transcriptional state. EMT reversal was evident from increased E-cadherin and β-catenin, and reduced N-cadherin, CD44, and Vimentin. Pro-apoptotic genes CASP3, CASP8, CASP9, and BAX were upregulated, while BCL2 was suppressed, suggesting activation of both apoptotic pathways. Metabolomics profile unveiled the changes in pathways related to apoptosis, anti-angiogenesis, and redox homeostasis. In silico analyses confirmed reduced KISS1 expression in metastatic TNBC tissues and highlighted a correlation between high GATA2/CASP9 levels and improved survival. Kisspeptin-10 reactivates KISS1 and induces anti-tumor effects via transcriptional, apoptotic, and metabolic reprogramming, highlighting its potential as a therapeutic agent in triple-negative breast cancer.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Cancer is one of the major global health concerns; among them, one of the most challenging and aggressive is Triple-negative breast cancer (TNBC), a subtype of breast cancer. As it is established that TNBC lacks three major receptors: the estrogen receptor (ER), progesterone receptor (PR), and human epidermal growth factor receptor 2 (HER2), which are commonly used as the phenotypic markers in advanced breast cancer1,2. Therefore, Patients with TNBC can only receive cytotoxic chemotherapy and are not eligible for hormone or HER2-directed therapies. Chemotherapy’s effectiveness in TNBC is a bottleneck because patients typically have early relapse, distant metastases, and moderate survival. TNBC is noted inordinately in younger, premenopausal women and women of African origin, and it accounts for upto 15–20% of all cases of breast cancer3,4,5. These patterns show socioeconomic and demographic ramifications in addition to its biological aggression of TNBC.

In the context of clinical complications, TNBC is characterized by its high molecular heterogeneity1. Broadly TNBC encircles various intrinsic subtypes characterized by different transcriptomic signatures, such as basal-like, mesenchymal-like, immunomodulatory, and luminal androgen receptor (LAR)–positive groups, each representing variable prognostic and treatment responses6,7,8. High proliferative indices and TP53 mutations in DNA damage mechanism pathways are elevated in TNBC9. Conversely, mesenchymal-like tumors showed elevated expression of genes responsible for extracellular matrix remodelling and stemness in epithelial–mesenchymal transition (EMT), making them more invasive and metastatic. The development of effective and broad applicable targeted therapies is impeded by the biological and emphasize the need of identifying novel and advanced regulatory mechanisms that can be used across TNBC subtypes43,47.

The two important molecular features of TNBC are transcriptional networks and oncogenic signaling pathways 10. Various transcription factors such as SP1, C-MYC, HDAC2, ZEB1, CDX2, GATA2, and FLI1, are commonly overexpressed or atypically activated in TNBC36. These molecules initiate tumor progression by activating cell cycle progression, immune evasion, chromatin remodelling and EMT induction11. Simultaneously, signaling molecules like PKA, PKR, PLCB1, and CJUN play a vital role in cellular stress adaptation, inflammation, and resistance to apoptosis. Synergistically, these factors help TNBC cells to survive in hostile microenvironments and under therapeutic pressure. Adding these alterations, TNBC cells rapidly undergo metabolic reprogramming, initiating a shift towards increased glycolysis, enhanced glutamine uptake, and alternative nutrient use to underpin their growth and metastasis under hypoxia42,43.

Amid these multiplex alterations, kisspeptin, a peptide encoded by the KISS1 gene, has evident potential to modulate tumor progression, based on the metastasis suppression in melanoma12. Kisspeptin is extensively studied for its regulatory roles in reproductive endocrinology,however, in cancer biology, its expression and functional relevance have procured its relevance. In different types of cancers, specifically melanoma and trophoblastic tumors, kisspeptin has been proposed to modulate its expression through feedback mechanisms. Such observations indicate the possibility that exogenous kisspeptin supplementation may modulate endogenous KISS1 gene regulation in cancer cells49, potentially reenforcing suppressive signaling in environments where this regulatory axis is partially intact13. The availability of kisspeptin could reset decreased signaling towards the invasiveness, enhanced differentiation, and pro-apoptotic responses. This idea becomes especially relevant in tumours where KISS1 is expressed but likely functionally uncoupled, it could be due to deficient ligand levels or dominant alternative pathways35,. From the recent observations, this notion has been supported by showing that exogenous kisspeptin administration can regulate various molecular targets beyond those directly linked to EMT or migration41. These suggest that kisspeptin may act as a regulatory molecule in TNBC48, influencing numerous cancer-relevant axes when reintroduced into the tumor system. Kisspeptin may exert regulated pressure across various transcriptional, apoptotic, and metabolic programs, effectively shifting the tumor cell phenotype toward a less aggressive state rather than indicating a single defined pathway32

Regardless of tumor-suppressive profile, various transcriptomic and patient-based reports have highlighted increased KISS1 expression in more invasive breast cancer subtypes, including basal-like and mesenchymal TNBCs. It is strongly evident that KISS1 expression alone does not uniformly predict a suppressive outcome, and its biological role may change depending on the cellular context and molecular surroundings of the tumor. The functional importance of KISS1 upregulation in aggressive TNBC entails research paucity55. It may indicate a stress-initiated or compensatory response of tumor cells, an incomplete34 or contextually overridden regulatory circuit, or a marker of broader differentiation pathways that are no longer effective in halting disease progression. 50This lack of consistency emphasizes the need to explore the behaviour of kisspeptin in TNBC concerning downstream signaling37, ligand–gene feedback, and crosstalk50 with other pro-tumorigenic pathways36,52.

Thus, this study aims to elucidate the detailed role of kisspeptin in TNBC, focusing on its expression, functional significance, and therapeutic potential51. By exploring its influence on key cancer hallmarks such as EMT, apoptosis, and cellular metabolism, and seeks to uncover new insights into the potential of kisspeptin as a regulator of tumor progression and a candidate for targeted therapy in TNBC34.

Materials and methods

Cell culture maintenance

MDA-MB-231 and MDA-MB-468 cells, a human TNBC cell line, were obtained from the National Centre for Cell Sciences (NCCS), Pune and used as an experimental model. Cells were cultured in Leibovitz’s L-15 medium (HiMedia, AL011A) and was supplemented with 10% fetal bovine serum (FBS; Gibco; 26,140,079), with 1% penicillin–streptomycin to provide essential growth. The cells were maintained at 37 °C under atmospheric conditions. Kisspeptin-10 (YNWNSFGLRF-NH2) was acquired from Sigma Aldrich (Catalogue No.: K2644) and exogenous treatment regime was carried out.

Overall experimental regime

This study employed an integrated in vitro- in silico experimental framework to investigate the molecular effects of Kisspeptin-10 in TNBC. MDA-MB-231 cells (5000–10,000 cells/ well) seeded in a 96-well multi-well plates and treated with increasing concentrations of Kisspeptin-10 (10, 25, 50, 100, 200, 500, 1000 nM) for 24 h. Cell proliferation was assessed using MTT assay (HiMedia: TC191). MDA-MB-231 and MDA-MB-468 cells were treated with the inhibitory concentration 10 (IC10) and 50 (IC50) doses of Kisspeptin-10 as determined by MTT assay (Johan van Meerloo et al., 2011), with untreated and Doxorubicin-treated cells (IC10, IC50) (Doxorubicin-HCl: HiMedia: TC420-10MG) serving as negative and positive controls, respectively. All experiments were independently repeated at least three times with appropriate technical and biological replicates to ensure homogeneity in the results. The following doses were used: Kisspeptin-10-IC₁₀: 12.13 nM, Kisspeptin-10- IC₅₀: 110.21 nM Doxorubicin-HCL-IC₁₀: 62.38 nM, Doxorubicin-HCL- IC₅₀: 442.30 nM.

Hence, there are five groups:

Control: Untreated Cells.

Kisspeptin-10-IC₁₀: 12.13 nM (K10) for MDA-MB-231 and 9.31 nM (K10) for MDA-MB-468.

Kisspeptin-10- IC₅₀: 110.21 nM (K50) for MDA-MB-231 and 88.35 nM (K50) for MDA-MB-468.

Doxorubicin-HCL-IC₁₀ (positive control): 62.38 nM(D10) for MDA-MB-231 and 39.24 (D10) for MDA-MB-468.

Doxorubicin-HCL- IC₅₀ (positive control): 442.30 nM(D50) for MDA-MB-231 and 378.35(D50) for MDA-MB-468.

Cell migration assay

A wound healing assay was used to determine the migratory response of MDA-MB-231 and MDA-MB-486 cells to kisspeptin treatment. Cells were grown to 80% confluency and 2 × 105 cells/well seeded in 6-well plates, and a uniform scratch was made using a sterile 200 µL pipette tip. Detached cells were removed with PBS, and cells were incubated with or without kisspeptin for 24–48 h. Wound closure was imaged at 0, 12, and 24 h using an inverted phase-contrast microscope, and the migration distance was quantified using ImageJ software.

RNA isolation, cDNA synthesis and qRT-PCR

Total RNA was extracted from treated and control cells, after washing with PBS, using TRIzol reagent. Total RNA was isolated by14 protocol. RNA was quantified and purity was confirmed using a nanodrop spectrometer (Shimadzu BioSpec-nano). The cDNA was synthesized from total RNA using High-Capacity cDNA Reverse Transcription Kit (Thermo Fischer: 4,368,814). Gene-specific primers were designed for the following markers: SP1, CDX2, GATA2, C-MYC, FLI1, ZEB1, PKA, PKR, PLCB1, CJUN, E-cadherin, N-cadherin, Vimentin, β-catenin, CD44, BCL2, BAX, CASPASE 3, CASPASE 8, and CASPASE 9 using NCBI, as outlined in Supplementary Table 1 and normalisation was done using ß-actin as internal control. Quantitative real-time PCR was performed using SYBR Green master mix (Thermo Fisher: A25742) for 40 cycles as per the protocol employed. The “∆∆Ct,” “2^-∆∆Ct” was computed in Microsoft Excel and relative fold change of gene of interest was calculated.

Western blot analysis

For protein expression analysis, cells were lysed in RIPA buffer supplemented with 10% protease inhibitor (Sigma: S8820) and centrifuged at 12,000 RPM for 10 min at 4 °C. The supernatant was then used to quantify the total protein concentrations using the Bradford method. (Kielkopf et al., 202058). The samples were then prepared in Laemmli buffer (HiMedia: ML021) and then stored at −20 °C. A total of 40 µg were loaded and separated by SEMS-PAGE using a 5% stacking gel and 12% resolving gel. After electrophoresis, proteins were transferred onto PVDF membranes (Immunobilon), blocked with 5% BSA, prepared in TBST for 1 h. The blots were then incubated with a primary antibody (Invitrogen and AbClonal) at a dilution of 1:1000 to 1:1500, overnight at 4 °C. This was followed by incubation with HRP-conjugated secondary antibodies (1:250) (Invitrogen) for 2 h. The crossreactivity of all the antibodies were evaluated and validated prior to the conduction of experiment. The detection was performed with DAB reagents. Band intensities were quantified using ImageJ software and were normalized to β-actin. The details of the monoclonal antibodies used are mentioned in Supplementary Table 2.

Metabolomic profiling

Untargeted metabolomics was performed for Control and Kisspeptin-treated MDA-MB-231 cells to investigate the metabolite alteration trends. Cold methanol: waAssay for Determining Protein Concentrationter (80:20, v/v) was used to extract the metabolites, which were then vortexed and centrifuged for 10 min at 4 °C at 14,000 rpm. Both positive and negative electrospray ionisation modes of liquid chromatography–mass spectrometry (LC–MS) were used to analyse the supernatants. MS Converter software was used to process the raw data, identify the metabolites, and create a qualitative volcano plot. Pathway enrichment analysis and metabolite network pathway were then conducted using Cytoscape. Changed biochemical pathways were highlighted by the visualisation of metabolic networks.

In silico expression and prognostic analysis

Publicly available transcriptomic datasets were accessed to validate experimental findings and assess the clinical relevance of key genes. UALCAN (http://ualcan.path.uab.edu) was used to analyse differential gene expression between TNBC and normal tissues using TCGA data. TNMplot (https://tnmplot.com) was employed to visualize tumor-versus-normal expression33 differences for KISS1 and related markers26. Kaplan–Meier survival curves were generated using KM Plotter (http://kmplot.com) to evaluate the association between gene expression and overall survival in breast cancer patients for following genes: SP1, C-MYC, HDAC2, ZEB1, CDX2, GATA2, and FLI1, PRKACA (PKA), EIF2AK2 (PKR), PLCB1, and CJUN, E-cadherin, N-cadherin, Vimentin, β-catenin, CD44, BCL2, BAX, CASPASE 3, CASPASE 8, and CASPASE 9.

Computational transcriptomics analysis of public gene expression datasets in TNBC and non-TNBC samples

Two publicly available transcriptomic datasets, GDS4069 and GDS825, were retrieved from the NCBI Gene Expression Omnibus (GEO) database to investigate gene expression patterns specific to triple-negative breast cancer (TNBC). These datasets were chosen based on their inclusion of well-annotated TNBC and non-TNBC breast cancer samples. For datasets with raw CEL files, preprocessing and normalization were performed using the affy and limma packages in R, while datasets with available normalized expression matrices were directly imported and log₂-transformed. Gene annotation was conducted using the corresponding GEO platform files, and in cases where multiple probes mapped to a single gene, the probe with the highest average expression across samples was retained. Genes with low expression across all samples were filtered out using an empirical threshold. Differential gene expression analysis was then conducted to identify transcriptional changes distinguishing TNBC from non-TNBC subtypes within each dataset. The limma package was used for microarray data, and the DESeq2 package was applied where RNA-seq data were involved. Adjusted p-values were computed using the Benjamini–Hochberg method, and genes with |log₂ fold-change|> 1 and adjusted p < 0.05 were considered significantly differentially expressed. Volcano plots were generated to visualize genome-wide expression changes in terms of both magnitude and statistical significance. To ensure robustness, only DEGs consistently observed across both GDS4069 and GDS825 were retained for downstream analysis. These shared DEGs (~ 70 genes) were subjected to hierarchical clustering following z-score normalization, and visualized via heatmaps using the pheatmap package in R. Clustering was based on Euclidean distance and complete linkage to highlight similarities in gene expression patterns between TNBC and non-TNBC groups. To investigate regulatory influences, a list of approximately 20 transcription factors and regulatory proteins (e.g., SP1, ZEB1, TCF12, CASP3, PKA) was curated from literature and databases such as TFLINK, focusing on factors involved in transcription, metastasis, apoptosis, and chromatin remodelling. Known or predicted regulatory interactions between these regulators and the shared DEGs were compiled and used to construct a bipartite gene–regulator network in Cytoscape v3.10.0. In the final network visualization, regulators were colored orange, DEGs green, and node size was scaled by degree of connectivity, offering insights into the transcriptional regulatory landscape of TNBC.

Data analysis

All statistical analysis was performed using GraphPad Prism version 8.0. The data were presented as mean ± SEM unless stated otherwise and was analyzed by one-way ANOVA followed by Duncan’s new multiple range post hoc test. The statistical significance was noted at * p < 0.05, ** p < 0.01, *** p < 0.001. All the observations were following normal distribution and homogeneity.

Results

Kisspeptin-10 regulates transcriptional networks, suppresses proliferation, and shows prognostic relevance in triple-negative breast cancer

MDA-MB-231 and MDA-MB-486 cells were treated with Kisspeptin-10 for 24 h, and cell viability was assessed using the MTT assay. The half-maximal inhibitory concentration (IC₅₀) of Kisspeptin-10 was determined to be 110.21 nM, while the IC₁₀ was 12.13 nM. Doxorubicin-HCl was used as a positive control, showed an IC₅₀ of 442.30 nM and an IC₁₀ of 62.38 nM (Fig. 1a). Further, for MDA-MB-486, the half maximal inhibitory concentration of Kisspeptin-10 was determined as 88.35 nM and for Doxorubicin-HCl it was 378.35 nM, while the IC10 was 9.31 nM and 39.24 nM respectively for Kisspeptin-10 and Doxorubicin-HCl.

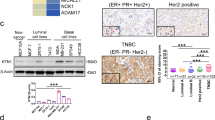

(a) Dose–response curve showing the effect of increasing concentrations of Kisspeptin-10 on cell viability in MDA-MB-231 and MDA-MB-468 cells. A concentration-dependent reduction in viability is observed. Doxorubicin-HCl is included as a positive control. (b) Heatmap showing differential expression of KISS1/KISS1R signaling components, transcription factors, EMT markers, and adhesion molecules in TNBC (tumor) vs. normal breast tissue samples (TCGA-BRCA dataset). Blue to red color scale represents low to high expression (log₂ TPM + 1). (c) Kaplan–Meier overall survival analyses for selected transcription factors (SP1, FLI1, ZEB1, MYCN, GATA2, CDX2) in breast cancer patients. High expression levels of several factors are associated with poor prognosis. (d) RT-qPCR analysis of MDA-MB-231 and MDA-MB-468 cells treated with Kisspeptin-10 at IC₁₀ and IC₅₀ concentrations of SP1, GATA2, CDX2, MYCN, ZEB1, FLI1, and upregulation of KISS1 and KISS1R. Doxorubicin-treated groups are included as positive controls. Data represent mean ± SEM; statistical analysis by one-way ANOVA (*p < 0.05, **p < 0.01, ***p < 0.001). (e) Validation of transcriptional changes at the protein level in MDA-MB-231 and MDA-MB-468 cells treated with Kisspeptin-10 (IC₅₀). Bar graphs show fold changes in mRNA expression, while accompanying Western blots show reduced levels of SP1, GATA2, CDX2, MYCN, ZEB1, FLI1, and increased KISS1 and KISS1R protein levels. β-actin is used as the loading control.

To investigate the transcriptional impact of Kisspeptin-10, we assessed mRNA expression levels of key transcription factors (SP1, GATA2, CDX2, MYCN, ZEB1, and FLI1) and KISS1/KISS1R via qPCR following treatment at IC₁₀ (K10) and IC₅₀ (K50). Significant upregulation of SP1 was observed at both K10 (**p < 0.01) and K50 (***p < 0.001). GATA2 and CDX2 also exhibited marked upregulation in K10-treated cells (***p < 0.001), with sustained elevation at K50. MYCN expression was significantly increased in the K10 group (**p < 0.05). In contrast, EMT-associated transcription factors ZEB1 and were downregulated in a dose-dependent manner (**p < 0.01 and ***p < 0.001), indicating a potential reversal of EMT. Importantly, KISS1 and KISS1R mRNA levels were significantly upregulated following Kisspeptin-10 treatment, suggesting a positive feedback regulatory loop (Fig. 1d). Western blot analysis confirmed the transcriptional findings at the protein level. SP1 and GATA2 showed substantial, dose-dependent upregulation in response to Kisspeptin-10. FLI1 protein levels modestly increased in both K10 and K50 treatment groups. ZEB1 protein expression significantly decreased (p < 0.05), supporting the mRNA data and suggesting EMT inhibition. MYCN expression was strongly upregulated at K50, while CDX2 showed a marginal reduction at the higher dose (Fig. 1e).

UALCAN-based transcriptomic profiling using TCGA datasets revealed significant differential expression patterns of Kisspeptin-associated genes in TNBC tissues versus normal breast tissues. Transcription factors such as CDX2, GATA2, FLI1, and KISS1 were markedly downregulated in TNBC, while ZEB1, SP1, MYCN, JUN, and HDAC2 were upregulated. Similarly, EMT-associated genes like VIM, CD44, CTNNB1, TWIST1, PLCB1, and PKA showed increased expression, whereas epithelial marker E-CADHERIN (CDH1) was notably downregulated (Fig. 4). These patterns validate the relevance of our experimental findings in a clinical context and highlight the tumor-suppressive role of Kisspeptin-regulated networks (Fig. 1b).

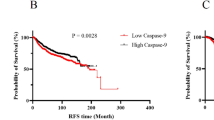

Kaplan–Meier survival analysis was performed to determine the clinical significance of Kisspeptin-regulated transcription factors in breast cancer. High expression of SP1 (HR = 0.62, CI 0.49–0.79, ***p < 0.001), ZEB1 (HR = 0.69, CI 0.60–0.81, ***p < 0.001), FLI1 (HR = 0.79, CI: 0.64–0.99, p = 0.042), and GATA2 (HR = 0.47, CI 0.37–0.59, ***p < 0.001) correlated with improved overall survival. Conversely, elevated HDAC2 was associated with poor prognosis (HR = 1.65, CI 1.49–1.83, p < 0.0001), and MYCN had a modest but significant adverse impact (HR = 0.89, CI 0.80–0.98, p = 0.024). CDX2 expression did not exhibit a statistically significant correlation with survival outcomes (HR = 1.20, CI 0.95–1.51, p = 0.12) (Fig. 1c).

Kisspeptin-10 modulates stress, inflammation, and proliferation-associated signalling in MDA-MB-231 cells and their prognostic relevance in breast cancer

The expression levels of four key signaling genes—CJUN, PKA, PLCB1, and PKR (EIF2AK2)—were evaluated at both mRNA and protein levels in MDA-MB-231 and MDA-MB-468 cells following treatment with Kisspeptin-10 at IC₁₀ (K10) and IC₅₀ (K50) concentrations. CJUN mRNA expression was significantly downregulated in the K50 group (p < 0.01), while no significant change was observed in the K10 group in both the cell lines. This transcriptional suppression was mirrored at the protein level, with Western blotting showing a notable reduction in CJUN protein expression, particularly at K50. In contrast, PKA was significantly upregulated at the mRNA level in both K10 (p < 0.05) and K50 (p < 0.01) groups, and this increase was confirmed at the protein level through Western blot analysis, indicating dose-dependent activation of PKA expression in both the cell lines. PLCB1 showed a modest but statistically significant increase in mRNA expression only in the K50 group (p < 0.05), with no change in the K10 group; consistent with this, PLCB1 protein levels were elevated at the higher dose, suggesting a transcriptionally driven translational regulation while showed no significant change in MDA-MB-468 groups.

PKR (EIF2AK2) mRNA expression was significantly upregulated in both K10 (p < 0.05) and K50 (p < 0.01) groups; however, its protein expression was not assessed in the present study. Together, these results demonstrate that Kisspeptin-10 modulates critical signaling mediators associated with proliferation, stress response, and inflammation in a dose-dependent manner, with consistent trends observed between transcript and protein levels where assessed. (Fig. 2a, b) Kaplan–Meier survival analysis was performed using KMplotter for EIF2AK2, PLCB1, PKA and CJUN in breast cancer patients. Elevated EIF2AK2 expression was significantly associated with poorer overall survival (HR = 1.13, CI 1.02–1.25, p = 0.017), highlighting its potential prognostic significance in breast cancer. In contrast, neither PLCB1 (HR = 1.06, CI: 0.96–1.17, p = 0.24) nor JUN (HR = 0.99, CI: 0.89–1.09, p = 0.78) expression levels were significantly correlated with patient survival. The survival curve for CJUN was unavailable or incomplete, likely due to the absence of probe-specific data or insufficient sample size in the dataset. These findings suggest that EIF2AK2 may serve as a prognostic biomarker in breast cancer, while the roles of PLCB1 and JUN may be context-specific and warrant further investigation. (Fig. 2c).

(a) mRNA expression of signaling molecules upon Kisspeptin-10 treatment. Quantitative PCR analysis of CJUN, PKA, PKR (EIF2AK2), and PLCB1 mRNA levels in MDA-MB-231 and MDA-MB-468 cells treated with Kisspeptin-10 at IC₁₀ (K10) and IC₅₀ (K50) concentrations. CJUN mRNA was significantly downregulated at K50; PKA was upregulated at both K10 and K50; PKR and PLCB1 were significantly increased at K50. (b) Protein expression of key signaling molecules following Kisspeptin-10 exposure. (c) Survival analysis of signaling molecules in breast cancer. Kaplan–Meier plots from KMplotter for EIF2AK2, PLCB1, CJUN, and JUN. Statistical significance is denoted as: *p < 0.05, **p < 0.01, **p < 0.001; ns = not significant.

Kisspeptin-10 attenuates migration, regulates EMT and apoptosis, and influences prognostic markers in TNBC

At baseline (0 h), the wound width was comparable across all groups. For MDA-MB-231 by 12 h, the control group demonstrated a noticeable decrease in wound width, while the K10 and K50 groups showed slower closure. At 24 h, the control group exhibited the greatest wound closure, followed by K10, and the slowest closure was observed in the K50 group (Fig. 3a).

While for MDA0MB-468, microscopic observations at 0, 12, and 24 h revealed progressive wound closure in control cells, with nearly complete healing by 24 h, whereas K10- and K50-treated groups showed markedly reduced closure over time. Quantitative analysis confirmed that control cells achieved approximately 85% wound closure, while K10 and K50 treatments resulted in only ~ 40% and ~ 25% closure, respectively, at 24 h. These findings indicate that Kisspeptin-10 significantly inhibits cell migration, with a stronger effect at higher concentrations, suggesting its potential role in suppressing cellular motility relevant to anti-metastatic activity. (Fig. 3b).

For evaluation of the effect of Kisspeptin-10 on epithelial–mesenchymal transition (EMT) and metastasis-related gene expression in both the TNBC cells, mRNA levels of E-Cadherin, N-Cadherin, CD44, β-Catenin, and Vimentin. E-Cadherin, a classical epithelial marker, was significantly upregulated in the K50 group (p* < 0.05), while K10 showed no significant change in both the cell lines. N-Cadherin and CD44, both mesenchymal and stemness markers respectively, were significantly downregulated in both K10 (p * < 0.05) and K50 (p ** < 0.01) groups in MDA-MB-231 while both of them showed non-significant downregulation in MDA-MB-468 cells. β-Catenin, a dual-function molecule involved in Wnt signaling and cell adhesion, was significantly upregulated in Kisspeptin-treated cells (*p < 0.05 and p** < 0.01 for K10 and K50, respectively) similarly with MDA-MB-468 cells. While, Vimentin a hallmark mesenchymal intermediate filament protein, was significantly downregulated in both Kisspeptin-treated groups (**p < 0.05 and ***p < 0.001), with expression decreasing in a dose-dependent manner in both the cell lines. Also, TNM plot analysis showed significant variation in KISS1 expression across tissue types (***p < 0.0001). Among the three groups, tumor samples exhibited the highest KISS1 expression, while normal and metastatic samples showed lower levels. The median KISS1 expression was lowest in the metastatic group, suggesting differential regulation of KISS1 during breast cancer progression and metastasis. (Fig. 4).

Fold change in mRNA expression levels of E-cadherin, N-Cadherin, CD44, Vimentin and B-Catenin following treatment with Kisspeptin-10 at IC₁₀ (K10) and IC₅₀ (K50), relative to the untreated control. Data represent mean ± SEM from three independent experiments. Statistical significance was determined by one-way ANOVA followed by post-hoc analysis. (*p < 0.05, **p < 0.01, ***p < 0.001, ns: not significant. TNM Box-whisker pot showcasing KISS1 expression in normal, tumour and metastatic breast cancer. (***p < 0.001).

For apoptotic gene expression following genes CASPASE 3, CASPASE 8, CASPASE 9, BAX, and BCL2 were assessed after treatment with Kisspeptin-10 (K10, K50) and Doxorubicin (D10, D50). Caspase 9, a critical initiator of the intrinsic apoptotic pathway, was significantly upregulated in both Kisspeptin-treated groups (p ** < 0.01 for K10 and ***p < 0.001 for K50) in MDA-MB-231 and was non-significantly upregulated in MDA-MB-468. Similarly, Caspase 3, a key effector caspase, exhibited transcriptional activation upon Kisspeptin exposure, with K50 showing the highest fold change (***p < 0.001) in MDA-MB-231 but non-significant upregulation with MDA-MB-468 cells. For both the cell lines, Caspase 8, representing the extrinsic apoptotic arm, was moderately elevated in K50 (p < 0.01). BAX, a pro-apoptotic member of the BCL2 family, was significantly downregulated in K10 (p ** < 0.01) and higher in K50 (***p < 0.001), aligning with observed caspase activation in both the cell lines. In contrast, BCL2, an anti-apoptotic gene, was downregulated Kisspeptin groups, with K50 showing a significant decrease (p ** < 0.01) compared to control (Fig. 5).

Relative mRNA expression levels of apoptotic markers— CASPASE 9, CASPASE 3, BAX, BCL2, and CASPASE 8—were assessed by qRT-PCR after 24 h treatment with Kisspeptin-10 at IC₁₀ (K10) and IC₅₀ (K50) doses. Data represent mean ± SEM from three independent experiments. Statistical significance was determined by one-way ANOVA followed by post-hoc analysis. (*p < 0.05, **p < 0.01, ***p < 0.001, ns: not significant).

Prognostic implications of EMT migration and stemness markers

CDH1, an epithelial marker, was significantly associated with improved overall survival (HR = 1.2, CI: 0.76–0.93, p = 0.00036). While, elevated levels of CDH2, a mesenchymal marker, correlated with reduced survival probability (HR = 1.13, CI 1.02–1.25, p = 0.021). VIM expression demonstrated a weak, non-significant trend toward favorable prognosis (HR = 0.92, CI 0.83–1.02, p = 0.095), suggesting variability in its functional impact across breast cancer subtypes. Likewise, CTNNB1, a central regulator of Wnt/β-catenin signaling, showed no significant correlation with survival (HR = 1.02, CI 0.87–1.18, p = 0.84), indicating a limited role in patient stratification based on its expression alone. CD44, a known cancer stem cell marker, exhibited a statistically significant association with improved survival (HR = 0.78, CI 0.67–0.91, p = 0.0015) (Fig. 6).

High expression of the anti-apoptotic gene BCL2 was significantly associated with improved overall survival (HR = 0.73, CI 0.66–0.81, p = 1.2e − 09), CASP9, a key initiator caspase in the intrinsic apoptosis pathway, showed a strong favorable prognostic value (HR = 0.63, CI 0.57–0.70, p < 1e − 16). CASP3 (Apopain), a central effector of apoptosis, exhibited a significantly worse prognosis with higher expression levels (HR = 1.27, CI 1.15–1.41, p = 3e − 06). For CASP8, a death receptor pathway caspase, and BAX, a pro-apoptotic BCL2 family protein, no statistically significant correlation with overall survival was observed (HR = 0.95, p = 0.36 and HR = 1.06, p = 0.28, respectively). (Fig. 6).

Metabolomic profiling reveals kisspeptin-10 mediated modulation of cellular metabolism in TNBC

Volcano plot of metabolite changes (Fig. 7a) showcases the varied altercations of different metabolites across the control versus the Kisspeptin-10 treated groups K10 and K50 which implies that Gingerdiol/Norcapsaicin, Usambarensine, S-Prenyl-L-cysteine, Peptide-like metabolites, and Tetrahydropterin derivatives, were absent in controls but consistently present in kisspeptin-treated samples. Others, such as DL-Tryptophan, Cadaverine, Octopamine, and L-Isoleucine/L-Leucine, were common across all groups but showed variable presence intensity. The data was also semi-quantitatively measured for the absence and presences in the three groups as Control, K10 and K50 in Supplementary Table 3.

(a) Volcano plot depicting log₂ fold change versus –log₁₀(p-value) of metabolite abundance in IC₁₀ and IC₅₀ Kisspeptin-10-treated cells compared to control. Several significantly altered metabolites, including Gingerdiol/Norcapsaicin, Peptide-like metabolites, L-Norleucine, and Acyclovir, are annotated. (b) Bar plot of top enriched biological themes and pathways classified by metabolite function, including angiogenesis/anti-proliferative, neurotransmitter metabolism, apoptosis/cytotoxicity, and glutathione/redox metabolism, with the number of metabolites involved shown on the x-axis. (c) Alluvial plot linking experimental conditions (Control, IC₁₀, IC₅₀) to affected pathways and specific metabolites, highlighting pathway shifts associated with Kisspeptin-10 treatment. (d) Metabolite–pathway association network showing interactions between significantly altered metabolites and their corresponding metabolic pathways. Colored nodes represent either metabolites (green) or pathways (orange), providing a visual overview of metabolomic reprogramming upon Kisspeptin-10 exposure.

The pathway enrichment analysis revealed that metabolites altered by kisspeptin treatment were primarily associated with angiogenesis and anti-proliferative processes, which showed the highest enrichment ratio among all categories. This was followed by notable representation in cytotoxicity, glutathione/redox regulation, and apoptosis. Moderate enrichment was also observed for amino acid metabolism, natural alkaloids, nucleotide/purine metabolism, and lipid/stress-related metabolic pathways. To dissect the compound-level relationships driving these enrichments, a Sankey-style compound–pathway flow visualization was generated. This network illustrated that metabolite such as DL-Tryptophan and Octopamine contributed prominently and amino acid metabolism, indicating potential overlaps in signaling and biosynthetic responses. Similarly, amino acid derivatives like L-Isoleucine / L-Leucine, L-Noreucine, and S-Prenyl-L-cysteine were centrally mapped under the amino acid metabolism axis. (Fig. 7b).

The alluvial plot depicts the relationships between experimental conditions (Control, K10, and K50), affected metabolic pathways, and corresponding metabolites. Notably, treatment with Kisspeptin-10 at both IC₁₀ (K10) and IC₅₀ (K50) concentrations led to differential regulation of pathways involved in amino acid metabolism, fatty acid metabolism, the TCA cycle, glycolysis, and purine metabolism. Metabolites such as L-valine, succinate, uracil, fumarate, and citric acid were enriched in Kisspeptin-treated groups, particularly in K50, indicating enhanced flux through the TCA cycle and amino acid biosynthesis. Furthermore, xenobiotic, and flavonoid metabolism appeared specifically linked to Kisspeptin treatment, highlighting potential detoxification or stress response mechanisms activated by KP-10. (Fig. 7c).

Metabolites such as Usambarensine and Indoleacrylic acid were linked to purine and nucleotide metabolism, while Pyroglutamic Acid, 2-Acetyl-5-methyl-pyridine, and Fluticasone were mapped under glutathione and antioxidant pathways, highlighting a redox-sensitive metabolic reprogramming. Furthermore, Methyl 2-(10-heptadecenyl)-6-hydroxybenzoate, (Menthane) Polyols, and Sarcostin were associated with cell death and cytotoxicity-related categories, reinforcing the apoptotic influence observed in treated cells. These metabolite–pathway associations collectively demonstrate that kisspeptin exposure elicits a coordinated biochemical response that spans cell survival, redox homeostasis, neurotransmission, and anti-proliferative signaling, underlining the systemic nature of kisspeptin’s impact on TNBC cellular metabolism. (Fig. 7d).

Transcriptomic landscape of triple-negative breast cancer reveals coordinated gene dysregulation and regulatory hubs

Comprehensive transcriptomic analysis of triple-negative breast cancer (TNBC) using two publicly available datasets (GDS4069 and GDS825) revealed consistent and widespread gene expression alterations distinguishing TNBC from non-TNBC breast cancer subtypes. Differential gene expression analysis using adjusted p-values (< 0.05) and log₂ fold-change thresholds (|log₂FC|> 1) identified numerous significantly dysregulated genes in both datasets, as depicted by symmetrical volcano plots. Notably, upregulated genes included SPARC, GDF15, KLK11, and TCF19, which are involved in extracellular matrix remodelling, stress response, and transcriptional regulation. In contrast, key downregulated genes such as CDH1 (ECAD), SLC22A18AS, and CDH8 signified loss of epithelial characteristics and tumor suppressor activity, hallmarks commonly associated with the TNBC phenotype. Cross-comparison of DEGs from both datasets yielded approximately 70 shared genes that showed consistent expression patterns across TNBC cohorts. Hierarchical clustering of these shared DEGs using z-score normalization generated a clear separation of TNBC samples from other subtypes, reinforcing the robustness of the TNBC-specific gene signature. Within the heatmap, genes like GAS2, RARFG3, SLC1A1, and FGB were markedly upregulated, while MAP1B, TCF19, and ECAD were consistently downregulated, further supporting their classification as candidate biomarkers for TNBC. To gain mechanistic insights into transcriptional regulation, a gene–regulator network was constructed using 20 literature-curated transcription factors and signaling proteins relevant to cancer biology. The network revealed that SP1 was connected to eight DEGs, indicating its broad regulatory influence, while ZEB1—a known driver of epithelial–mesenchymal transition (EMT)—was linked to repression of epithelial markers such as ECAD and SPARC. Pro-apoptotic regulators like CASPASE3, CASPASE8, and BAX were connected to genes involved in cell death pathways (e.g., MAP1B, CDH8), suggesting attenuated apoptotic signaling in TNBC. Additional nodes such as KMT2D and TCF12 showed regulatory connections to genes involved in transcriptional control and chromatin dynamics, implying broader epigenetic remodeling in TNBC cells.To complement these findings, Gene Ontology (GO) enrichment analysis was performed on the shared DEGs. The results revealed significant enrichment in cellular components such as phagocytic vesicles, specific granules, and actin cytoskeleton, indicating active cytoskeletal remodeling and altered vesicular trafficking. Enriched biological processes included extracellular matrix organization, RNA capping, granulocyte activation, and fatty acid biosynthesis, highlighting a convergence of structural, immunological, and metabolic adaptations in TNBC. Moreover, molecular function terms such as zinc ion binding, dipeptidyl-peptidase activity, and calcium ion transmembrane transport suggested disruptions in key enzymatic and signaling processes. Together, these integrated findings delineate a robust TNBC-specific gene signature underpinned by coordinated regulatory networks and functional pathways that likely drive the aggressive phenotype of this breast cancer subtype. (Fig. 8).

Integrated transcriptomic analysis reveals shared differentially expressed genes, regulatory interactions, and enriched functional pathways in triple-negative breast cancer (TNBC). (A) Gene–Regulator Association Network constructed from shared DEGs across GDS825 and GDS5099 datasets. Orange nodes represent regulatory factors (e.g., SP1, GATA2, ZEB1, HDAC2), and green nodes represent target genes. Edges denote regulatory interactions, highlighting transcriptional hubs in TNBC. (B) Heatmap of shared DEGs depicting expression profiles across TNBC (MDA-MB-436) and non-TNBC (HCC1954) samples. Samples are grouped by condition, and gene expression is scaled and clustered. Red indicates upregulation, and blue indicates downregulation. (C) Volcano plot of DEGs from GDS825 (MDA-MB-436 vs. HCC1954), showing the distribution of genes based on log₂ fold change and statistical significance (adjusted p-value). Green points indicate significantly differentially expressed genes. (D) Venn diagram illustrating the overlap of DEGs between datasets GDS825 and GDS5099. A total of 234 DEGs were shared and used for downstream analyses. (E) KEGG pathway enrichment analysis showing top enriched pathways among shared DEGs, including apoptosis, p53 signaling, and cell cycle regulation. Bar color intensity corresponds to adjusted p-values. (F) Gene Ontology (GO) enrichment analysis highlighting the most enriched biological processes, such as execution phase of apoptosis and microtubule cytoskeleton organization. Bars represent the number of genes involved in each term.

Discussion

Triple-negative breast cancer (TNBC) remains one of the most clinically aggressive and biologically complex breast cancer subtypes, lacking targeted therapies due to the absence of ER, PR, and HER2 expression. The dynamic interplay of oncogenic signaling, dysregulated transcription, epithelial-to-mesenchymal transition (EMT), apoptotic resistance, and metabolic adaptation in TNBC underscores the need for multipronged molecular therapeutics. In this study, we propose Kisspeptin-10 (Kp-10), a peptide product encoded by the metastasis suppressor gene KISS1, as a potential multi-target agent capable of modulating diverse molecular hallmarks in TNBC57. Kisspeptin’s role in breast cancer has historically been dichotomous, functioning as a metastasis suppressor in some contexts while paradoxically exhibiting pro-tumorigenic associations in others, particularly in triple-negative contexts where its receptor KISS1R has been reported to be overexpressed15. Considering this complexity, a comprehensive analysis integrating phenotypic assays, molecular profiling, and metabolomics to dissect the mechanisms underlying Kp-10 action was performed in MDA-MB-231 cells. The study showcased how Kisspeptin-10 (KP-10) acts as a potent modulator in triple-negative breast cancer (TNBC), altering the expression profile of several transcription factors critically involved in tumor progression, epithelial-to-mesenchymal transition (EMT), and chromatin regulation27.

In MDA-MB-231 cells, treatment with low (IC₁₀) and high (IC₅₀) doses of KP-10 significantly upregulated SP1, GATA2, CDX240, and MYCN, while downregulating ZEB1. These changes were confirmed at both the mRNA and protein levels via qPCR and Western blotting, respectively. Notably, SP1—a factor traditionally associated with oncogenic pathways—has also been shown to mediate pro-differentiation and apoptotic programs42 in context to KISS1 overexpression in TNBC16.

Its upregulation by KP-10 aligns with favourable survival outcomes observed in breast cancer cohorts (KMPlot, HR = 0.62), suggesting it may have tumor-suppressive function, particularly when paired with other KP-responsive changes. Similarly, GATA2 and CDX2, both linked to lineage determination and reduced tumor aggressiveness56, were significantly induced by KP-10. GATA2 is known to suppress metastasis via modulation of chromatin accessibility and stemness signatures, while CDX2 has been implicated in epithelial identity and loss of invasiveness in gastrointestinal and breast tumours

On the other hand, downregulation of ZEB1 and HDAC2—a hallmark of EMT suppression—suggests that KP-10 may alter the levels of mRNA transcript leading towards a less invasive phenotype. ZEB1 represses E-cadherin and promotes mesenchymal markers like N-cadherin and vimentin, which facilitate metastasis and chemotherapy resistance. Its suppression by KP-10 is consistent with findings in endometrial cancer, where KP-10 treatment led to downregulation of N-cadherin, β-catenin, and Twist, and upregulation of E-cadherin, thereby inhibiting motility and invasion52. HDAC2, a class I histone deacetylase, silences tumor suppressor genes and enhances chromatin condensation and cellular plasticity. Elevated HDAC2 expression is often linked with worse outcomes and chemoresistance in breast and other solid tumours16. Thus, its repression by KP-10 reinforces the compound’s potential role in re-sensitizing TNBC cells to epigenetic control and improving clinical outcomes.

Furthermore, gene expression data from UALCAN analysis validated the clinical relevance of these findings: SP1, GATA2, CDX2, and FLI1—genes upregulated by KP-10—are generally under expressed in TNBC tumours compared to normal breast tissue, while ZEB1, HDAC2, and MYCN—those downregulated or selectively regulated—are overexpressed in tumours. This indicates that KP-10 restores an expression profile resembling that of non-tumorigenic tissue, suggesting transcriptional reprogramming toward a less aggressive phenotype. Importantly, the prognostic data further support this mechanism, as KP-10–upregulated genes like GATA2 (HR = 0.47), SP1 (HR = 0.62), and FLI1 (HR = 0.79) are associated with better survival, whereas HDAC2 (HR = 1.65) and MYCN (HR = 0.89) predict poorer outcomes. Taken together, these findings propose a model wherein exogenous KP-10 restores transcriptional homeostasis in TNBC by activating differentiation-associated transcription factors and repressing pro-metastatic and chromatin-condensing regulators. This supports the concept that Kisspeptin signaling, despite its roles in cancer, can be therapeutically exploited to rewire oncogenic transcriptional networks when delivered under controlled conditions. Future studies could explore the downstream signaling cascades—such as MAPK/ERK and PI3K/AKT—that mediate these regulatory shifts, as previous studies have shown that KISS1R activation can converge on these pathways in ERα-negative tumours. Kisspeptin-10 exposure in MDA-MB-231 cells resulted in pronounced anti-migratory effects, as demonstrated by the wound healing assay. Compared to the control group, both IC₁₀ and IC₅₀ doses significantly delayed wound closure, with the IC₅₀ group exhibiting the most reduced migration at 24 h. These results corroborate earlier findings on the anti-metastatic role of Kisspeptin via KISS1/GPR54 signaling, which is known to inhibit cell motility through modulation of cytoskeletal and adhesion dynamics ( Nash et al.,17. The intracellular signaling orchestration in triple-negative breast cancer (TNBC) is often characterized by hyperactivated stress, proliferation, and inflammatory pathways that drive aggressive tumor behaviou r. In this study, we examined the modulatory effects of Kisspeptin-10 on key molecular regulators—CJUN, PKA, PKR (EIF2AK2), and PLCB1—to delineate its influence on cellular signaling dynamics in MDA-MB-231 cells.

Quantitative PCR revealed that CJUN, a critical component of the AP-1 transcription factor complex and a downstream effector of the MAPK/JNK signaling axis, was significantly downregulated upon K50 treatment, but not at the lower K10 dose. This reduction in CJUN expression suggests that Kisspeptin-10 may dampen proliferative and inflammatory signaling cascades, particularly under high-dose conditions. This finding was corroborated at the protein level via Western blot, where CJUN expression also declined significantly with both IC₁₀ and IC₅₀ concentrations. These observations are particularly relevant given that chronic activation of CJUN is implicated in tumorigenesis, invasion, and chemoresistance in TNBC (Vleugel et al., 2006). However, Kaplan–Meier survival analysis of JUN and CJUN did not demonstrate a significant correlation with patient prognosis, implying that while Kisspeptin may alter their expression, the clinical predictive value of CJUN remains context-dependent or may vary with tumor subtype and stage. Conversely, PKA (Protein Kinase A), a central mediator of cAMP-dependent signaling, was significantly upregulated at both mRNA and protein levels in Kisspeptin-treated cells. The elevation of PKA suggests an activation of the cAMP/PKA axis, which is known to exert context-specific effects in breast cancer, ranging from anti-proliferative to pro-apoptotic outcomes18. Notably, PKA has been reported to inhibit Ras/Raf/MEK/ERK signaling through phosphorylation of Raf-1, thereby counteracting MAPK-driven oncogenesis—a mechanism that may underlie Kisspeptin’s tumor-suppressive potential in this context. This aligns with our earlier findings showing suppressed proliferation and enhanced apoptosis following Kisspeptin-10 treatment, suggesting that PKA activation might contribute to growth inhibition and pro-apoptotic signaling. The PKR (EIF2AK2) gene, a serine-threonine kinase activated by double-stranded RNA and involved in translational repression and stress granule formation, was also significantly upregulated at both K10 and K50 doses. As a component of the integrated stress response (ISR), PKR is involved in phosphorylating eIF2α, thereby inhibiting global protein synthesis and triggering cell death under severe stress conditions19. Its increased expression in response to Kisspeptin-10 implies activation of stress surveillance mechanisms that may contribute to anti-proliferative and pro-apoptotic cellular fates28. Importantly, KMplotter analysis showed that elevated EIF2AK2 expression was significantly associated with poorer overall survival in breast cancer patients (HR = 1.13, *p < 0.05), indicating that its regulation may carry clinical significance. While this might seem contradictory to its tumor-suppressive function in vitro, it could reflect tumor adaptation or compensatory survival mechanisms in vivo, particularly under therapeutic stress. PLCB1, a phospholipase involved in hydrolyzing PIP2 into IP3 and DAG, thus initiating calcium mobilization and PKC activation, was also modestly upregulated at the mRNA and protein level, especially at K50. While its role in breast cancer remains somewhat ambiguous, increased PLCB1 expression has been associated with altered calcium signaling and resistance phenotypes in certain cancer types. However, KMplotter analysis did not reveal any significant correlation between PLCB1 expression and survival outcomes in breast cancer, suggesting its role may be more mechanistic than prognostic. Nonetheless, the increase in PLCB1 may reflect Kisspeptin-induced modulation of intracellular calcium dynamics, which warrants further exploration in the context of cell motility and apoptosis. While CJUN and PKA were upregulated, PLCB1 was downregulated, underscoring the mechanistic differences between traditional chemotherapeutic agents and peptide-based regulators like Kisspeptin-10. The divergent expression trends suggest that Kisspeptin-10 may operate via non-canonical signaling axes, potentially offering additive or synergistic benefits when combined with cytotoxic drugs. Collectively, these findings demonstrate that Kisspeptin-10 exerts pleiotropic effects on TNBC signaling pathways by suppressing oncogenic transcription factors like CJUN, while simultaneously activating stress and cAMP-mediated protective kinases such as PKR and PKA. These molecular alterations likely contribute to the observed inhibition of cell proliferation and induction of apoptosis in MDA-MB-231 cells, supporting the therapeutic promise of Kisspeptin-10 in aggressive breast cancer phenotypes.

In parallel, transcriptional analysis of EMT and metastasis-related genes revealed a dose-dependent upregulation of CDH1 (E-Cadherin) and significant downregulation of CDH2 (N-Cadherin), CD44, and VIM (Vimentin), establishing Kisspeptin’s capacity to reverse EMT. This reversal of mesenchymal traits is a hallmark of reduced metastatic potential. Upregulation of E-Cadherin, a key epithelial marker, supports restoration of cell–cell adhesion and epithelial polarity, while suppression of Vimentin and N-Cadherin dampens cytoskeletal plasticity and migratory ability—crucial for invasive progression20,21,. Downregulation of CD44, a known stemness and invasion-associated marker, further suggests impaired cancer stem cell–like behavior and metastatic competency 22. Furthermore, Kisspeptin-10 promoted apoptotic reprogramming, as evident from transcriptional upregulation of key apoptotic genes including Caspase 9, Caspase 3, Caspase 8, and BAX, particularly at IC₅₀. The significant downregulation of BCL2, an anti-apoptotic gene, provides compelling evidence of intrinsic apoptosis pathway activation. Notably, Caspase 9 acts upstream in mitochondrial-mediated apoptosis and was the most strongly induced gene, suggesting mitochondrial involvement in the Kisspeptin-triggered death cascade23. Caspase 3, a terminal executioner caspase, showed high expression levels, implying effective cleavage of downstream substrates and commitment to apoptosis. The implications of these findings are further reinforced by prognostic survival analyses. Elevated CDH1 expression was significantly associated with improved overall survival (**p < 0.001), while higher levels of CDH2 were correlated with poorer prognosis (**p < 0.05), aligning with the EMT-suppressive effect of Kisspeptin-10. Interestingly, although Vimentin showed significant downregulation following treatment, its survival correlation was not statistically significant (p = 0.095), suggesting context-dependent variability in its prognostic relevance. Among apoptosis-related markers, high expression of BCL2 and CASP9 correlated with better survival (**p < 0.001), consistent with their roles in survival regulation and treatment sensitivity. Conversely, elevated CASP3 expression was paradoxically linked to worse outcomes (**p < 0.001), possibly reflecting compensatory overexpression in more aggressive tumours rather than therapeutic induction39. Collectively, these findings suggest that Kisspeptin-10 reprograms TNBC cells toward a less invasive, more apoptotically primed phenotype by downregulating key drivers of EMT and metastasis, while activating mitochondrial and extrinsic apoptotic machinery. This coordinated molecular response reflects the tumor-suppressive potential of Kisspeptin, offering mechanistic insights into its dual roles as both a metastasis suppressor and apoptosis inducer in aggressive breast cancer phenotypes. Future in vivo validations and mechanistic dissection of the KISS1-GPR54 axis will be essential to assess its translational value as a therapeutic modulator in TNBC38.

Further assessment of the transcriptional and translational impact of exogenous Kisspeptin-10 treatment in two triple-negative breast cancer (TNBC) cell lines—MDA-MB-231 (mesenchymal-like) and MDA-MB-468 (basal-like)—at IC₁₀ and IC₅₀ doses revealed significant subtype-specific responses. A consistent upregulation of KISS1 and KISS1R was observed in both cell lines, with a more pronounced fold increase in MDA-MB-468, indicating a potentially stronger autocrine activation in basal-like cells. However, the downstream effects were markedly more significant in MDA-MB-231. Transcription factors associated with proliferation and EMT, including SP1, CDX2, FLI1, GATA2, and NMYC, were substantially downregulated at the protein level in MDA-MB-231 following Kisspeptin-10 exposure, particularly at IC₅₀, suggesting effective suppression of mesenchymal aggressiveness53,54. In contrast, MDA-MB-468 exhibited relatively moderate changes, consistent with its less invasive and more epithelial-like phenotype. Moreover, mesenchymal markers such as N-cadherin, Vimentin, ZEB1, and CD44 were significantly suppressed in MDA-MB-231, while epithelial markers like E-cadherin were concurrently upregulated, indicative of a robust mesenchymal-to-epithelial transition (MET). This transition was less pronounced in MDA-MB-468. β-Catenin downregulation, a hallmark of reduced Wnt signaling and stemness, was more evident in MDA-MB-231, further supporting the notion of inhibited invasiveness. Additionally, pro-apoptotic markers (BAX, cleaved Caspase-3/8/9) were elevated and anti-apoptotic BCL2 downregulated in both cell lines; however, apoptosis was more robustly induced in MDA-MB-231. The signaling mediators CJUN, PKR, PKA, and PLCB1 also exhibited greater repression in MDA-MB-231, reflecting broader suppression of survival pathways. Altogether, while both TNBC cell lines responded to Kisspeptin-10 treatment, the mesenchymal-like MDA-MB-231 cells demonstrated a more pronounced phenotypic reversion, greater apoptosis induction, and broader oncogenic signaling suppression than the basal-like MDA-MB-468, underscoring the potential of Kisspeptin-10 as a more effective therapeutic strategy for highly aggressive, mesenchymal TNBC subtypes.

The metabolomic analysis unveiled that Kisspeptin-10 exposure induces a broad metabolic reprogramming in MDA-MB-231 cells, marked by a clear dose-dependent shift in the presence and intensity of key metabolites46. This shift is not merely metabolic in isolation but rather reflects a deeper cellular recalibration intricately tied to transcriptional regulation, intracellular signaling, and apoptotic execution29. Notably, metabolites such as Gingerdiol/Norcapsaicin, Usambarensine, and S-Prenyl-L-cysteine were exclusively present in Kisspeptin-treated cells and absent in controls, pointing to Kisspeptin-10’s role in activating specialized metabolic pathways. These compounds have previously been linked to anti-inflammatory, cytotoxic, and redox regulatory functions, implying a redirection of cellular resources from proliferation to survival defense and controlled cell death10,17,. The early emergence of these metabolites even at IC₁₀ suggests Kisspeptin’s ability to prime cells for stress adaptation, while the pronounced metabolic presence at IC₅₀ indicates a threshold of irreversible apoptotic commitment24. This metabolic shift is paralleled by transcriptional changes in critical regulators44. Upregulation of GATA2, MYCN, and SP1, especially under IC₅₀ treatment, aligns with elevated expression of amino acid and neurotransmitter-associated metabolites such as DL-Tryptophan, Octopamine, and L-Noreucine. These transcription factors are known to regulate cellular stress responses, chromatin accessibility, and growth control25. For instance, SP1, a zinc-finger transcription factor, directly modulates antioxidant genes and apoptotic regulators,its upregulation here corresponds with enrichment of glutathione and redox-related pathways, including metabolites like Pyroglutamic acid and Fluticasone, indicating a feedback loop between transcription and redox adaptation31. Moreover, the suppression of ZEB1, a classical EMT transcriptional driver, in Kisspeptin-treated groups supports the anti-migratory phenotype. This is mechanistically reinforced by the metabolomic signature: reduced levels of lipid and cytoskeletal remodeling intermediates in K10 and K50 samples. Such findings are in tandem with previously observed repression of mesenchymal markers like VIMENTIN and NCAD, and upregulation of ECAD, consolidating Kisspeptin’s EMT-inhibitory role via both transcriptomic and metabolic checkpoints.

From a signaling perspective, elevated activity of PKA and PLCB1, observed in parallel experiments, is consistent with the presence of bioamines and secondary messengers such as Octopamine, which function as intermediates in G-protein-coupled receptor (GPCR) signaling45. This aligns with Kisspeptin’s known action through the GPR54 receptor, where downstream activation of CJUN and EIF2K2 may further amplify stress granule formation and pro-apoptotic signaling cascades30. These events orchestrate a broader regulatory program that extends into nucleotide and purine metabolism, with metabolites such as Usambarensine and Indoleacrylic acid suggesting modulation of nucleic acid turnover and transcriptional kinetics. Importantly, several of the altered metabolites, including Sarcostin and Methyl 2-(10-heptadecenyl)-6-hydroxybenzoate, are linked to cytotoxicity and programmed cell death, echoing the transcriptional upregulation of pro-apoptotic markers such as BAX, CASPASE-3/8/9, and downregulation of BCL2. This reinforces a consistent narrative: Kisspeptin-10 drives TNBC cells toward apoptosis by harmonizing metabolic shutdown with gene-level directives, rather than isolated molecular switches.

The comprehensive transcriptomic landscape outlined in this study provides critical insights into the molecular underpinnings of triple-negative breast cancer (TNBC), reinforcing its distinct biological identity among breast cancer subtypes. The identification of consistent differentially expressed genes (DEGs) across two independent datasets not only validates the robustness of the TNBC gene signature but also underscores the reproducibility of these findings. Upregulated genes such as SPARC, GDF15, and TCF19, known to be involved in extracellular matrix remodelling, stress adaptation, and transcriptional regulation, point toward active tissue remodelling and heightened cellular plasticity—hallmarks of aggressive tumor behaviour. Conversely, the downregulation of key epithelial and tumor suppressor genes such as CDH1 (E-cadherin), CDH8, and SLC22A18AS suggests a loss of epithelial integrity and increased metastatic potential, both characteristic of the mesenchymal-like features commonly observed in TNBC. The identification of approximately 70 consistently dysregulated genes across datasets and their clear hierarchical clustering supports their potential utility as diagnostic or prognostic biomarkers.

Importantly, regulatory network analysis illuminated central transcriptional hubs driving these alterations. SP1 emerged as a major transcriptional regulator, interfacing with multiple DEGs and potentially orchestrating a broad spectrum of oncogenic processes. ZEB1, a master regulator of EMT, was implicated in repressing epithelial markers like ECAD, reinforcing its role in promoting the mesenchymal phenotype. The apparent disconnection of apoptotic regulators such as CASPASE3 and BAX from their downstream effectors suggests that apoptotic evasion is an entrenched feature of TNBC transcriptomics. Furthermore, the enrichment of GO terms related to cytoskeletal architecture, vesicular transport, and immune modulation reflects the dynamic microenvironmental interactions that support TNBC progression. The overrepresentation of zinc ion binding, dipeptidyl peptidase activity, and calcium ion transport functions points to disruptions in key enzymatic and signaling cascades, which may serve as actionable vulnerabilities.

Together, this systems-level reprogramming demonstrates that Kisspeptin-10 functions not just as a metastatic suppressor but as a master regulator of TNBC cell fate, bridging transcription factor dynamics, signaling pathway flux, metabolic remodelling, and apoptotic execution. The overlap between pathways governing neurotransmission, redox balance, amino acid turnover, and cell death presents compelling evidence that Kisspeptin elicits a concerted anti-cancer response, fundamentally reconfiguring the metabolic architecture of malignant cells. Future studies leveraging stable isotope tracing and metabolic flux analysis could further delineate the causal sequence of events and clarify whether these metabolic shifts are upstream signals or downstream consequences of transcriptional rewiring. Nevertheless, these findings position Kisspeptin-10 as a potent multi-target candidate for metabolic and signaling-based interventions in triple-negative breast cancer.

Conclusion

The exogenous administration of Kisspeptin-10 restores KISS1 expression and exerts multifaceted anti-tumorigenic effects in triple-negative breast cancer (TNBC) cells. Kisspeptin-10 administration suppresses cell proliferation, inhibits migration, reverses epithelial-to-mesenchymal transition, and activates intrinsic and extrinsic apoptotic pathways. Transcriptional and metabolic reprogramming further reinforce a shift toward a less aggressive tumor phenotype. These findings indicate Kisspeptin-10 as a potential therapeutic candidate capable of reactivating tumor suppressor networks in TNBC. Although this is a preliminary work based on in vitro and in silico analyses, further in vivo validation and mechanistic exploration are required to establish its clinical applicability. This study signifies the therapeutic relevance of Kisspeptin signaling modulation in addressing the challenges of aggressive breast cancer subtypes.

Data availability

The datasets generated during and/or analysed during the current study are available from the corresponding author on reasonable request.

References

Metzger-Filho, O. et al. Dissecting the heterogeneity of triple-negative breast cancer. J. Clin. Oncol. 30(15), 1879–1887. https://doi.org/10.1200/jco.2011.38.2010 (2012).

Upadhyay, K., Patel, F., Ramachandran, A. V., Robin, E. & Baxi, D. Breaching the barriers of chemotherapeutics for breast cancer with alternative medicine. J Endocrinol Reprod 25(1), 23–35. https://doi.org/10.18311/jer/2021/27792 (2021).

Bianchini, G., Balko, J. M., Mayer, I. A., Sanders, M. E. & Gianni, L. Triple-negative breast cancer: Challenges and opportunities of a heterogeneous disease. Nat. Rev. Clin. Oncol. 13(11), 674–690. https://doi.org/10.1038/nrclinonc.2016.66 (2016).

Carey, L. A. et al. Race, breast cancer subtypes, and survival in the Carolina breast cancer study. JAMA 295(21), 2492–2502. https://doi.org/10.1001/jama.295.21.2492 (2006).

Dent, R. et al. Triple-negative breast cancer: Clinical features and patterns of recurrence. Clin Cancer Res: Off J Am Assoc Cancer Res 13(15 Pt 1), 4429–4434. https://doi.org/10.1158/1078-0432.CCR-06-3045 (2007).

Burstein, M. D. et al. Comprehensive genomic analysis identifies novel subtypes and targets of triple-negative breast cancer. Clin Cancer Res: Off J Am Assoc Cancer Res 21(7), 1688–1698. https://doi.org/10.1158/1078-0432.CCR-14-0432 (2015).

Curtis, C., Shah, S. P., Chin, S. F., Turashvili, G., Rueda, O. M., Dunning, M. J., Speed, D., Lynch, A. G., Samarajiwa, S., Yuan, Y., Gräf, S., Ha, G., Haffari, G., Bashashati, A., Russell, R., McKinney, S., METABRIC Group, Langerød, A., Green, A., Provenzano, E., Aparicio, S. The genomic and transcriptomic architecture of 2000 breast tumours reveals novel subgroups. Nature 486(7403), 346–352. https://doi.org/10.1038/nature10983 (2012).

Lehmann, B. D. et al. Identification of human triple-negative breast cancer subtypes and preclinical models for selection of targeted therapies. J. Clin. Investig. 121(7), 2750–2767. https://doi.org/10.1172/JCI45014 (2011).

Sporikova, Z., Koudelakova, V., Trojanec, R. & Hajduch, M. Genetic markers in triple-negative breast cancer. Clin. Breast Cancer 18(5), e841–e850. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.clbc.2018.07.023 (2018).

Sun, X. et al. Metabolic reprogramming in triple-negative breast cancer. Front. Oncol. 10, 428. https://doi.org/10.3389/fonc.2020.00428 (2020).

Wang, Z., Jiang, Q. & Dong, C. Metabolic reprogramming in triple-negative breast cancer. Cancer Biol Med 17(1), 44–59. https://doi.org/10.20892/j.issn.2095-3941.2019.0210 (2020).

Lee, J. H. et al. KiSS-1, a novel human malignant melanoma metastasis-suppressor gene. J. Natl Cancer Inst. 88(23), 1731–1737. https://doi.org/10.1093/jnci/88.23.1731 (1996).

Nash, K. T. & Welch, D. R. The KISS1 metastasis suppressor: Mechanistic insights and clinical utility. Front Biosci 11, 647–659. https://doi.org/10.2741/1824 (2006).

Dan, N. et al. Decoding the effect of photoperiodic cues in transducing kisspeptin-melatonin circuit during the pubertal onset in common carp. Mol Reprod Dev https://doi.org/10.1002/mrd.23744 (2024).

Ciaramella, V., Della Corte, C. M., Ciardiello, F. & Morgillo, F. Kisspeptin and Cancer: molecular interaction, biological functions, and future perspectives. Front. Endocrinol. 9, 115. https://doi.org/10.3389/fendo.2018.00115 (2018).

Blake, A. et al. G protein-coupled KISS1 receptor is overexpressed in triple negative breast cancer and promotes drug resistance. Sci. Rep. 7, 46525. https://doi.org/10.1038/srep46525 (2017).

Sahu, S. et al. Ongoing repair of migration-coupled DNA damage allows planarian adult stem cells to reach wound sites. Elife 23(10), e63779 (2021).

Zhang, H. et al. Complex roles of cAMP–PKA–CREB signaling in cancer. Exp Hematol Oncol 9, 32. https://doi.org/10.1186/s40164-020-00191-1 (2020).

Gal-Ben-Ari, S., Barrera, I., Ehrlich, M. & Rosenblum, K. PKR: A kinase to remember. Front. Mol. Neurosci. 11, 480. https://doi.org/10.3389/fnmol.2018.00480 (2019).

Lamouille, S., Xu, J. & Derynck, R. Molecular mechanisms of epithelial–mesenchymal transition. Nat Rev Mol Cell Biol 15, 178–196. https://doi.org/10.1038/nrm3758 (2014).

Nieto, M. A., Huang, R. Y., Jackson, R. A. & Thiery, J. P. EMT: 2016. Cell 166(1), 21. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.cell.2016.06.028 (2016).

Yan, Y., Zuo, X. & Wei, D. Concise review: Emerging role of CD44 in cancer stem cells: A promising biomarker and therapeutic target. Stem Cells Transl. Med. 4(9), 1033–1043. https://doi.org/10.5966/sctm.2015-0048 (2015).

Elmore, S. Apoptosis: A review of programmed cell death. Toxicol. Pathol. 35(4), 495–516. https://doi.org/10.1080/01926230701320337 (2007).

Armitage, E. G. & Barbas, C. Metabolomics in cancer biomarker discovery: Current trends and future perspectives. J. Pharm. Biomed. Anal. 87, 1–11. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jpba.2013.08.041 (2014).

Hao, Y., Baker, D. & Ten Dijke, P. TGF-β-mediated epithelial-mesenchymal transition and cancer metastasis. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 20(11), 2767. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijms20112767 (2019).

Bartha, Á. & Győrffy, B. TNMplot.com: A web tool for the comparison of gene expression in normal, tumor and metastatic tissues. Int J Mol Sci 22(5), 2622. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijms22052622 (2021).

Bates, R. C. & Mercurio, A. M. The epithelial-mesenchymal transition (EMT) and colorectal cancer progression. Cancer Biol. Ther. 4(4), 365–370. https://doi.org/10.4161/cbt.4.4.1655 (2005).

Ukhueduan, B., Chukwurah, E. & Patel, R. C. Regulation of PKR activation and apoptosis during oxidative stress by TRBP phosphorylation. Int. J. Biochem. Cell Biol. 137, 106030–106030. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.biocel.2021.106030 (2021).

Cao, M. D. et al. Metabolic characterization of triple negative breast cancer. BMC Cancer 14, 941. https://doi.org/10.1186/1471-2407-14-941 (2014).

Castaño, J. P. et al. Intracellular signaling pathways activated by kisspeptins through GPR54: Do multiple signals underlie function diversity?. Peptides 30(1), 10–15. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.peptides.2008.07.025 (2009).

Castellano, J. M., & Tena-Sempere, M. (2013). Metabolic Regulation of Kisspeptin (pp. 363–383). https://doi.org/10.1007/978-1-4614-6199-9_17

Chaffer, C. L. & Weinberg, R. A. A perspective on cancer cell metastasis. Science 331(6024), 1559–1564. https://doi.org/10.1126/science.1203543 (2011).

Chandrashekar, D. S. et al. UALCAN: An update to the integrated cancer data analysis platform. Neoplasia 25, 18–27. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.neo.2022.01.001 (2022).

Cho, S. G. & Choi, E. J. Apoptotic signaling pathways: Caspases and stress-activated protein kinases. J. Biochem. Mol. Biol. 35(1), 24–27. https://doi.org/10.5483/bmbrep.2002.35.1.024 (2002).

Cvetković, D., Babwah, A. V. & Bhattacharya, M. Kisspeptin/KISS1R system in breast cancer. J. Cancer 4(8), 653–661. https://doi.org/10.7150/jca.7626 (2013).

Dang, C. V. MYC on the path to cancer. Cell 149(1), 22–35. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.cell.2012.03.003 (2012).

De Opakua, A. I. et al. The metastasis suppressor KISS1 is an intrinsically disordered protein slightly more extended than a random coil. PLoS ONE https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0172507 (2017).

de Roux, N. et al. Hypogonadotropic hypogonadism due to loss of function of the KiSS1-derived peptide receptor GPR54. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. 100(19), 10972–10976. https://doi.org/10.1073/pnas.1834399100 (2003).

Fratangelo, F., Carriero, M. V. & Motti, M. L. Controversial role of kisspeptins/KISS1R signaling system in tumor development. Front Endocrinol https://doi.org/10.3389/fendo.2018.00192 (2018).

Goto, T. et al. Identification of hypothalamic arcuate nucleus-specific enhancer region of Kiss1 gene in mice. Mol. Endocrinol. 29(1), 121–129. https://doi.org/10.1210/me.2014-1289 (2015).

Győrffy, B. Integrated analysis of public datasets for the discovery and validation of survival-associated genes in solid tumors. Innovation 5(3), 100625. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.xinn.2024.100625 (2024).

Li, D. et al. Estrogen regulates KiSS1 gene expression through estrogen receptor α and SP protein complexes. Endocrinology 148(10), 4821–4828. https://doi.org/10.1210/en.2007-0154 (2007).

Li, S. et al. Structural and functional multiplicity of the kisspeptin/GPR54 system in goldfish (Carassius auratus). J. Endocrinol. 201(3), 407–418. https://doi.org/10.1677/JOE-09-0016 (2009).

Li, X., Liang, C. & Yan, Y. Novel insight into the role of the kiss1/GPR54 System in energy metabolism in major metabolic organs. In Cells https://doi.org/10.3390/cells11193148 (2022).

Li, X., Liang, C. & Yan, Y. Novel insight into the role of the kiss1/GPR54 system in energy metabolism in major metabolic organs. Cells 11(19), 3148. https://doi.org/10.3390/cells1119314 (2022).

Liu, S. et al. Metabolic reprogramming and therapeutic resistance in primary and metastatic breast cancer. Mol Cancer 23, 261. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12943-024-02165-x (2024).

Motti, M. L. & Meccariello, R. Minireview: The Epigenetic modulation of KISS1 in reproduction and cancer. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 16(14), 2607. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph16142607 (2019).

Motti, M. L. & Meccariello, R. Minireview: The epigenetic modulation of kiss1 in reproduction and cancer. Int J Environ Res Public Health https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph16142607 (2019).

Pasquier, J. et al. MOLECULAR EVOLUTION OF GPCRS: Kisspeptin/kisspeptin receptors. J. Mol. Endocrinol. 52(3), T101–T117. https://doi.org/10.1530/JME-13-0224 (2014).

Prabhu, V. V., Sakthive, K. M. & Guruvayoorappan, C. Kisspeptins (KISS1): Essential players in suppressing tumor metastasis. Asian Pac J Cancer Prev https://doi.org/10.7314/APJCP.2013.14.11.6215 (2013).

Rather, M. A. et al. Characterization, molecular docking, dynamics simulation and metadynamics of kisspeptin receptor with kisspeptin. Int J Biol Macromol 101, 241–253. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ijbiomac.2017.03.102 (2017a).

Roseweir, A. K., Katz, A. A. & Millar, R. P. Kisspeptin-10 inhibits cell migration in vitro via a receptor-GSK3 beta-FAK feedback loop in HTR8SVneo cells. Placenta 33(5), 408–415. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.placenta.2012.02.001 (2012).

Scheiber, M. N. et al. FLI1 expression is correlated with breast cancer cellular growth, migration, and invasion and altered gene expression. Neoplasia 16(10), 801–813. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.neo.2014.08.007 (2014).

Shan, W., Jiang, Y., Yu, H., Huang, Q., Liu, L., Guo, X., Li, L., Mi, Q., Zhang, K., & Yang, Z. (2017). Original Article HDAC2 overexpression correlates with aggressive clinicopathological features and DNA-damage response pathway of breast cancer. In Am J Cancer Res (Vol. 7, Issue 5). www.ajcr.us/

Tng, E. Kisspeptin signalling and its roles in humans. Singap Med J 56(12), 649–656. https://doi.org/10.11622/smedj.2015183 (2015).

Wang, Y. et al. Silencing LINC01021 inhibits gastric cancer through upregulation of KISS1 expression by blocking CDK2-dependent phosphorylation of CDX2. Mol Therapy Nucleic Acids 24, 832–844. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.omtn.2021.01.025 (2021).

Zhu, N., Zhao, M., Song, Y., Ding, L. & Ni, Y. The KISS1/GPR54 system: Essential roles in physiological homeostasis and cancer biology. Genes Diseases 9(1), 28–40. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.gendis.2020.07.008 (2022).

Kielkopf, Clara L., et al. “Bradford Assay for Determining Protein Concentration.” Cold Spring Harbor Protocols, 2020(4), https://doi.org/10.1101/pdb.prot102269.

Acknowledgements

We express our gratitude towards Navrachana University for providing the infrastructure facility.

Funding

No funding was received for the present study.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

Hetvi Shah: Investigation, working on the methodology, curation of data and writing the original draft. Parth Pandya: Conceptualization, Funding acquisition, Project Supervision and Validation, Writing Review and Editing. Lipi Buch: Conceptualization, Funding acquisition, Project Supervision and Validation, Writing Review and Editing. Adikrishna Murali: Prognostic Bioinformatics analysis.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The contributing authors show no competing interests.

Informed consent

This study did not involve human participants, human data, or material that required patient consent hence patient consent statement not applicable.

Declaration of generative AI and AI-assisted technologies in the writing process

During the preparation of this work the authors used Grammarly/Quilbot in order to check the grammer and language. After using this tool/service, the authors reviewed and edited the content as needed and takes full responsibility for the content of the publication.

Additional information

Publisher’s note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Supplementary Information

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if you modified the licensed material. You do not have permission under this licence to share adapted material derived from this article or parts of it. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article