Abstract

Protein biomarkers from plasma extracellular vesicles (EVs) have been extensively identified in various diseases. To explore biomarkers associated with diabetic retinopathy (DR) progression, we designed two cohorts, discovery and validation cohorts, including four groups: healthy control, type 2 diabetes mellitus, non-proliferative DR (NPDR), and proliferative DR (PDR). A total of 32 differentially expressed proteins (DEPs) were screened by proteomic analysis in the four groups of the discovery cohort. Among them, four hub proteins, CELA3A, CELA3B, GLUD1, and CTRC, were identified to be related to DR progression, and their correlation with clinical characteristics was further analyzed. Subsequently, enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay in the validation cohort confirmed that the expression levels of CELA3A, CELA3B, and CTRC were consistent with the proteomic results. Receiver operator characteristic curve analysis found that the AUC values of three hub proteins and their composed panels distinguishing NPDR/PDR from DM were all > 0.7, except for DM-NPDR of CELA3B. In addition, CELA3A, CELA3B, and CTRC proteins were significantly correlated with some clinical indicators of DR. This study indicates that the plasma EV proteins CELA3A, CELA3B, and CTRC are expected to become biomarkers to monitor DR progression and provide guidance for DR diagnosis.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Diabetic retinopathy (DR) is a common microvascular complication of diabetes, contributing to significant visual impairment and blindness in the working-age population1. In 2020, approximately 103.12 million adults globally were affected by DR, with projections estimating this number to rise to 160.5 million by 20452. In China, the prevalence of DR is 16.3%, affecting about 23.3 million adults with diabetes3. According to the degree of disease progression, DR is clinically divided into two categories: non-proliferative DR (NPDR) and proliferative DR (PDR)4. Diabetic macular edema (DME) can occur at any stage of DR5. Visual impairment typically appears in advanced DME or PDR5. However, traditional therapies, including laser therapy, vitrectomy, and anti-vascular endothelial growth factor (VEGF) drugs, are primarily indicated for patients with advanced DR6. Therefore, exploring novel biomarkers for DR diagnosis, treatment, and prevention is critical.

Extracellular vesicles (EVs) are nano- to micro-sized particles with lipid bilayer structures that can be categorized as exosomes, microvesicles, and others based on their biogenesis pathway and size7,8. EVs, widely distributed in various biological fluids, are enriched with nucleic acids, proteins, lipids, and metabolites, and serve as important intercellular communication carriers to regulate physiological and pathological processes9,10. Increasing studies have demonstrated that EVs play an important role in DR11,12. Mighty et al. found that Junction Plakoglobin was a promising biomarker for DR diagnosis through proteomic analysis of retinal tissue and urine-derived EVs13. Wang et al. found that plasma EVs affected retinal angiogenesis through a miR-30b-dependent mechanism, thereby promoting the PDR progression14. Given the unique advantages of plasma EVs in reflecting systemic-retinal interactions and non-invasive acquisition, it is necessary to analyze their protein profiles.

In this study, we investigated the protein profiles of EVs isolated from patients at different stages of DR to identify differentially expressed proteins (DEPs), followed by functional enrichment analysis and protein-protein interaction (PPI) network construction. Subsequently, the hub proteins were screened, and clinical correlation analysis was performed. Finally, enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay (ELISA) was performed to validate the expression level of hub proteins. Our study may provide novel insights into the understanding of the pathophysiological mechanism of DR progression.

Methods

Participants and sample collection

In this study, the discovery cohort included 6 controls, 6 type 2 diabetes mellitus (DM) patients without clinically apparent retinopathy, 6 NPDR patients, and 5 PDR patients. The validation cohort included 26 controls, 30 type 2 DM patients, 26 NPDR patients, and 25 PDR patients. The study population of two cohorts ranged from 40 to 80 years old. Glycated hemoglobin (HbA1c) level was 7.0%−10.5% in the diseased populations. The NPDR and PDR patients were diagnosed by fundus fluorescein angiography. If disease severity differed between eyes, the more severely affected eye determined group assignment. The demographics and characteristics of the study population are shown in Table 1, with a p-value < 0.05 indicating statistical significance. Patients with intraocular pressure > 21mmHg, glaucoma, retinal vascular diseases, uveitis, optic nerve diseases, hereditary eye diseases, high myopia (>−6.0D) and other eye diseases, as well as infectious diseases (AIDS, syphilis, hepatitis B, etc.), autoimmune diseases, malignant tumors, systemic persistent infections, cerebral hemorrhage within 90 days and/or cerebral infarction and other serious systemic diseases were excluded. This study design complied with the principles of the Declaration of Helsinki and was approved by the Ethics Committee of Xuanwu Hospital of Capital Medical University (2023-046). Written informed consents were obtained from all individuals. Peripheral blood samples were collected from the above two cohorts. The plasma was extracted by centrifuging at 1,500 g for 20 min at 4 °C and stored at −80 °C.

Extraction of plasma EVs

Plasma samples were thawed and centrifuged at 2,000 g for 10 min at 4 °C to collect the supernatant. This supernatant was then centrifuged at 10,000 g for 30 min at 4 °C to remove large vesicles, after which it was transferred to a new tube for subsequent use. EVs were isolated using the qEV original Size Exclusion Column (Cat. No.: SP1, IZON Science, New Zealand). Prior to sample loading, the qEV column was sequentially washed with 10 mL of 1× PBS (Cat. No.: 20012-043, Gibco, USA), 10 mL of 0.5 M NaOH (Cat. No.: 1310-73-2, Millipore, Germany), and 20 mL of 1× PBS (three times). Subsequently, the supernatant was loaded onto the qEV column. Once the supernatant completely entered the sieve plate at the column top, 2.5 mL of 1× PBS was added. After discarding the 3 mL of void volume, 1.5 mL of eluate was collected, representing the relatively high-purity EV solution. Finally, the EVs were further enriched using magnetic beads. After washing the magnetic beads (10 µL) with PBS, they were resuspended in 25 µL of 1× PBS and added to the collected EV solution. The mixture was gently inverted 5 times to mix thoroughly, then incubated for 5 min. This process was repeated once, after which the tube was placed on a magnetic rack for 1 min. Once the magnetic beads were fully adsorbed to the tube wall, the supernatant was discarded to complete the EVs enrichment.

Nanoparticle tracking analysis (NTA)

The pelleted EVs were resuspended in 100 µL PBS. A 5 µL EV solution was diluted 1,000-fold using PBS and injected into the Nanosight NS300 nanoparticle tracking analyzer (Malvern Panalytical Ltd., UK) to size and count the EVs.

Transmission electron microscopy (TEM)

A 4 µL EV solution was loaded on a 400-copper mesh (Cat. No.: AZH50, Beijing Zhongjingkeyi Technology Co., Ltd, China) and incubated for 1 min at room temperature (RT), followed by absorbing the excess liquid with filter paper (Cat. No.: F503344, Sangon, China). Then, 7 µL uranyl acetate dihydrate (Cat. No.: CD106833, Codow, China) was added for 1 min, and the excess liquid was discarded. EVs’ morphology was observed by JEM-1400 TEM (JEOL, Akishima, Japan) after drying at RT.

Western blotting

Western blotting was carried out to detect EV surface-specific markers CD63, HSP70, and negative control Calnexin. The EVs were lysed with 100 µL of lysis solution containing 2% sodium dodecyl sulfate (SDS, Cat. No.: 1722586, Beijing Zhongjingkeyi Technology Co., Ltd, China) and protease inhibitors (final concentration 1×, Cat. No.: 78428, Thermo Scientific, USA), followed by centrifugation at 12,000 rpm for 20 min at 4℃ to obtain the protein supernatant. The protein concentration was detected by Bicinchoninic acid (BCA, BCA protein quantification kit [Cat. No.: 23227, Thermo Scientific, USA]) method. The 10% SDS-polyacrylamide gel electrophoresis (SDS-PAGE) fast preparation kit (Cat. No.: WB2102, Biotides, China) was used to prepare gels for protein sample loading and electrophoresis. Proteins were transferred to polyvinylidene fluoride (PVDF) membranes (Cat. No.: 1620177, Bio-Rad, USA) and blocked with skim milk. Membranes were incubated with primary antibodies for CD63 (1:1000, Cat. No.: 52090, Cell Signaling Technology, USA), HSP70 (1:1000, Cat. No.: 4872, Cell Signaling Technology, USA), TSG101 (1:1000, Cat. No.: bs-1365R, Bioss, China), and Calnexin (1:1000, Cat. No.: CSB-PA00899A0Rb, Cusabio, Wuhan China), followed by secondary HRP-linked antibodies (1:10000, Cat. No.: 7074, Cell Signaling Technology, USA). Chemiluminescence was performed using the Omni-ECL™ Femto Light Kit (Cat. No.: SQ201, Epizyme, China), and images were captured with the Touch Imager™ Electronic Compression Imager (eBolt, China).

LC-MS analysis for plasma EV protein detection

4D-label free quantitative proteomics analysis was conducted using a timsTOF Pro2 mass spectrometer (Brucker, Germany) coupled with the Brucker NanoElute (Brucker, Germany) liquid chromatography system. In brief, Proteins were extracted using the EasyPept Ex Trace Protein Extraction Kit (Cat. No.: OSFP0001, Shanghai Omicsolution Co., Ltd., China), and the concentration was determined by BCA method. A total of 30 µg of protein from each sample was reduced, alkylated, digested, and desalted using the EasyPept Ex kit, and concentrated by a Speedvac (SPD111V, Thermo Scientific, USA). Next, a 0.3 µg sample was resolubilized in mobile phase A (100% H2O, 0.1% formic acid) and centrifuged at 20,000 g for 10 min. The supernatant was injected into the NanoElute liquid chromatography system for separation. The sample first entered the trap column (Cat. No.: 174500, Thermo Scientific, USA) for enrichment and desalting, followed by a gradient elution on a self-assembled C18 column (75 μm I.D. × 250 cm, 1.8 μm) at a 300 nL/min flow rate. The gradient elution program was as follows: 0 min, 2% mobile phase B (100% acetonitrile and 0.1% formic acid); 0–45 min, 2%−22% B; 45–50 min, 22%−35% B;50–55 min, 35%−80% B; 55–60 min, 80% B.

The NanoElute liquid chromatography terminal was directly connected to the mass spectrometer. The separated peptides were ionized by CaptiveSpray source and then entered the tandem mass spectrometer timsTOF Pro2 for DIA (data-independent acquisition) mode detection. The parameters were set as follows: the ion source voltage was set to 1.5 kV, and the ion mobility range was 0.76–1.29 V s/cm². The primary mass spectrum scan range was 452–1152 m/z, and only ion signals with peak intensities ≥ 2500 were collected. The scan range (452–1152 m/z) was divided into four steps, with each step containing seven windows (mass window width = 25). The Number of Mobility Windows was set to 2, generating a total of 56 windows for continuous window fragmentation and information acquisition. The collision-induced dissociation mode was used, and the collision energy range was set to 20–59 eV. The cycle time for a single DIA scan was 1.59 s.

Identification and quantitation of proteins

The acquired raw data of mass spectrometry were imported into Parallel Database Search Engine in Real-time (PaSER, Version 3.0) software15, and the searches were performed using the TIMScore algorithm against the Homo sapiens proteome from the Swissprot database (Version 2024_02). The parameters were set as follows: the fixed modification was set as carbamido-methylation of cysteine, and the variable modifications were oxidation of methionine and acetylation of protein N-terminal; trypsin digestion was used, the maximum missed cleavage sites allowed was 2, and the minimum peptide length was 6; the ion mass tolerance was set to 10 ppm, and the target false discovery rate (FDR) of 0.01 (strict) and 0.05 (relaxed) was applied to the identification of peptides and proteins. The intensity of each protein precursor ion peak was normalized to obtain NORM_INTENSITY, followed by quantitative analysis.

Identification of differentially expressed proteins (DEPs) and enrichment analysis

The average expression level of each protein across the four groups was calculated, and then the fold change (FC) of each protein was determined based on their average values in DM vs. HC, NPDR vs. DM, and PDR vs. NPDR groups. Subsequently, the proteins with FC > 1.2 in three groups were selected16. Finally, the DEPs with p-value < 0.05 were identified using the ‘Kruskal-Wallis test’ function of the ‘stats’ package (version 4.4.3). The DAVID 2021 database (https://david.ncifcrf.gov/) was utilized for functional enrichment analysis of DEPs, including Gene Ontology (GO) and Kyoto Encyclopedia of Genes and Genomes (KEGG) enrichment analysis17,18,19,20. The term with p-value < 0.05 was considered statistically significant. The STRING database (https://cn.string-db.org/) was used to build the PPI networks for DEPs21.

Identification of hub proteins and clinical correlation analysis

The hub proteins were identified by comparing DEPs’ expression between two adjacent groups (HC vs. DM, DM vs. NPDR, NPDR vs. PDR) using the ‘wilcox.test’ function of the ‘stats’ package (version 4.4.3). Proteins with significant differential expression in all adjacent comparisons were visualized using box plots. The relationship between the glycemic indicators (HbA1c and fasting plasma glucose [FPG]) and hub proteins was investigated through Spearman correlation analysis. Additionally, the expression levels of hub proteins in different clinical groups were compared using the Wilcox test.

Validation of the expression levels of hub proteins by ELISA

Plasma EVs were extracted from the validation cohort patients (n = 107), and the expression level of hub proteins was determined by ELISA. Perform the following operations according to the ELISA kit instructions for CELA3A (Cat. No.: HM11975, Bioswamp, Wuhan, China), CELA3B (Cat. No.: JOT-EK6849Hu, Jotbody, Hong Kong), GLUD1 (Cat. No.: HM13755, Bioswamp, Wuhan, China), and CTRC (Cat. No.: SYP-H0971, UpingBio, Hangzhou, China): Gradient-diluted standards and test samples were added to monoclonal antibody-coated microplates. After adding biotinylated antibody and HRP-conjugated reagent, plates were incubated at 37℃ for 1 h, and washed 5 times. Then, chromogen solutions A and B were added to incubate for 10 min in the dark. After the reaction was stopped, and absorbance was measured to calculate analyte concentrations. Significance between groups was determined by one-way ANOVA.

Receiver operating characteristic (ROC) analysis for hub proteins and correlation analysis between hub proteins and clinical indicators

The ROC curves for CELA3A, CELA3B, and CTRC protein were plotted using GraphPad Prism 9, and the area under the curve (AUC) was calculated to represent their performance in predicting disease occurrence. Meanwhile, we used the R package “glmnet” (version 4.1-8), taking the expression levels of CELA3A, CELA3B, and CTRC as input variables, to fit a logistic regression model. Based on the predicted probability values output from this model, we performed ROC analysis to comprehensively evaluate the predictive performance of the panel (composed of these 3 hub proteins). The clinical characteristics among the four groups were compared using the “compareGroups” package (version 4.9.1)22. Pearson correlation analysis was conducted to evaluate the correlation between the expression levels of hub proteins and clinical indicators, with a p-value < 0.05 indicating statistical significance.

Results

The characterization of plasma EVs

The size of the EVs ranged from 30 nm to 200 nm, with a peak size at 100 nm, and the concentration of these EVs was 1011 particles/mL (Fig. 1A). Western blotting results showed that the extracted EVs were rich in transmembrane protein CD63 and solute protein HSP70 and TSG101 (positive markers of EVs23,24, while the intracellular protein Calnexin (negative marker of EVs23 was absent (Fig. 1B-Supplementary Fig. 1). The cup-shaped round particles with a diameter of around 100 nm were observed using TEM, consistent with the morphological characteristics of EVs (Fig. 1C). The above results indicated that plasma EVs were successfully isolated and structurally intact, which can be used for further analysis.

The characterization of EVs. (A) Nanoparticle tracking analysis. (B) Western blotting of EV markers CD63, HSP70, TSG101, and Calnexin. The full blots are shown in Supplementary Figures. (C) Transmission electron micrographs of EVs. HC, healthy control; DM, diabetes mellitus; NPDR, non-proliferative diabetic retinopathy; PDR, proliferative diabetic retinopathy.

Identification of deps

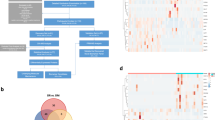

4D-label free technology identified a total of 12,021 peptides and 1,830 proteins (Supplementary Table 1). Among them, a total of 32 DEPs were obtained with FC > 1.2 and p-value < 0.05 (Supplementary Table 2). GO analysis showed that these proteins were primarily located in synapses and mitochondria, and involved in synaptic transmission, such as chemical synaptic transmission, neuromuscular process controlling balance, positive regulation of insulin secretion, neurotransmitter uptake, regulation of neurotransmitter secretion, and synaptic vesicle exocytosis (Fig. 2A, Supplementary Table 3). KEGG analysis indicated that DEPs were mainly associated with neurodegeneration, diabetic cardiomyopathy, pancreatic secretion, and synaptic vesicle cycle (Fig. 2B, Supplementary Table 3). There are 44 interaction pairs involving 25 proteins in the PPI networks. Among these, SNAP25 has the highest degree, interacting with 11 proteins. In the entire PPI network, there are two interaction pairs with scores above 0.95: NDUFS3 with SDHB and SLC25A4 with VDAC1 (Supplementary Fig. 2).

Enrichment analysis of DEPs. (A) The bubble plot displays the GO functional enrichment analysis results of DEPs. Bubble size indicates the number of proteins enriched in the term, and bubble color represents the P-value. The lines connecting proteins to GO terms indicate that the proteins are involved in this function. Gene.Ratio represents the number of DEPs enriched in the GO term as a proportion of the total number of DEPs. (B) Chord diagram displays the KEGG enrichment analysis results of DEPs. The right side represents the enriched pathway, while the left side shows DEPs arranged from large to small according to the P-value. The connection between the two indicates protein enrichment in this pathway. DEPs, differentially expressed proteins; GO, gene ontology; BP, biological process; CC, cellular component; MF, molecular function; KEGG, Kyoto Encyclopedia of Genes and Genomes.

Identification of hub proteins and clinical correlation analysis

A total of 4 hub proteins (CELA3A, CELA3B, CTRC, and GLUD1) were identified using the Wilcox test (Fig. 3). We found that the expression levels of CELA3A and CTRC were significantly increased in HC vs. DM, DM vs. NPDR, and NPDR vs. PDR groups (Fig. 3A-B). Meanwhile, the expression levels of CELA3B and GLUD1 were significantly up-regulated in the DM vs. NPDR and NPDR vs. PDR groups (Fig. 3C-D). Correlation analysis showed that HbA1c was significantly positively correlated with CELA3A and CTRC, and FPG was significantly related to CELA3A (Supplementary Fig. 3). This preliminary finding suggests a potential association between glycemic indicators and these proteins. Additionally, the expression levels of hub proteins were explored in different clinical groups. The expression levels of CELA3A, CELA3B, CTRC, and GLUD1 were significantly higher in the patients with DME and retinal hemorrhage groups (Supplementary Fig. 4).

Verification of the CELA3A, CELA3B, GLUD1 and CTRC expression levels

ELISA results of the independent validation cohort (n = 107) showed that, except for GLUD1, the overall trend of CELA3A, CELA3B, and CTRC protein expression was consistent with the proteomic results (Fig. 4). Interestingly, CELA3A, CELA3B, and CTRC protein expression levels were significantly different between the PDR and HC/DM groups, but there was no significant difference between the NPDR and PDR groups. In addition, CELA3A and CTRC were significantly different between the NPDR and HC/DM groups. This indicates that these three proteins may be involved in the progression from DM to DR.

ROC analysis for proteins CELA3A, CELA3B, CTRC

To further investigate the diagnostic values of three proteins, we plotted ROC curves, as shown in Fig. 5. All three hub proteins showed good diagnostic value between the DM and PDR groups, with AUC values of 0.908 for CELA3A, 0.715 for CELA3B, and 0.935 for CTRC. Notably, CELA3A and CTRC also exhibited predictive potential between DM and NPDR groups, with AUC values of 0.889 and 0.791, respectively. However, the diagnostic accuracy was lower in the NPDR and PDR groups, with AUC < 0.6. In addition, the AUC value of CELA3A in the HC and DM groups was 0.724. The diagnostic accuracy of CELA3B was relatively low, with AUC = 0.608 between DM and NPDR groups, and AUC = 0.635 between NPDR and PDR groups. The diagnostic efficacy of a panel (composed of 3 hub proteins) was further evaluated in DR staging. The ROC curves revealed high diagnostic efficacy in DM vs. NPDR (AUC = 0.868) and DM vs. PDR (AUC = 0.958) groups, whereas AUC values for HC vs. DM and NPDR vs. PDR were both < 0.7. The above results indicate that CELA3A, CELA3B, and CTRC may serve as effective biomarkers for distinguishing NPDR/PDR from DM.

ROC curves of three hub proteins for stage-specific diagnosis in DR. (A-D) CELA3A; (E-H) CELA3B; (I-L) CTRC; (M-P) The panel of 3 hub proteins. ROC, receiver operating characteristic; DR, diabetic retinopathy; HC, healthy control; DM, diabetes mellitus; NPDR, non-proliferative diabetic retinopathy; PDR, proliferative diabetic retinopathy.

Correlation analysis between clinical indicators and proteins CELA3A, CELA3B, CTRC

The clinical characteristics of the patients included in the validation cohort were shown in Table 2. The data showed that there were statistically significant differences in duration of DR, FPG, HbA1c, diastolic blood pressure (DBP), triglyceride (TG), and high-density lipoprotein (HDL). The correlation between three hub proteins and clinical indicators was further analyzed (Fig. 6). The results showed that CELA3A was significantly positively correlated with duration of DR, TG, and aspartate aminotransferase (AST), and significantly negatively correlated with potassium (K). CELA3B was significantly positively correlated with TG and calcium (Ca), and significantly negatively correlated with HDL. CTRC was significantly positively correlated with duration of DR and TG, and significantly negatively correlated with HDL. Furthermore, the panel composed of the 3 hub proteins showed positive correlation with the significantly differential clinical characteristics (duration of DR, DME, retinal hemorrhage) in the discovery cohort, with duration of DR and DME being statistically significant (Supplementary Fig. 5).

Correlation analysis between clinical indicators and proteins CELA3A, CELA3B, and CTRC. Red represents positive correlation, blue represents negative correlation. *p < 0.05, **p < 0.01. CELA3A was positively correlated with duration of DR, TG, and AST, and negatively correlated with K. CELA3B was positively correlated with TG and Ca, and negatively correlated with HDL. CTRC was positively correlated with duration of DR and TG, and negatively correlated with HDL. DR, diabetic retinopathy; TG, triglyceride; Ca, calcium; ALT, alanine aminotransferase; AST, aspartate aminotransferase; DBP, diastolic blood pressure; SBP, systolic blood pressure; IOP_OS, intraocular pressure left eye; HbA1c, glycated hemoglobin; FPG, fasting plasma glucose; BMI, body mass index; IOP_OD, intraocular pressure right eye; TC, total cholesterol; LDL, low density lipoprotein; HDL, high density lipoprotein; K, potassium.

Discussion

DR, a major diabetic microvascular complication, closely interacts with blood circulation, with hemodynamic changes and microvascular dysfunction collectively driving disease progression25. EVs are important material carriers and signaling mediators that spread via blood circulation to remotely regulate other cells and tissues and have been used to screen biomarkers in disease diagnosis and prognosis26. Our study identified four hub proteins (CELA3A, CELA3B, GLUD1, and CTRC) by investigating the plasma EV protein expression profile of patients at different stages of DR, which may be associated with the disease progression. Subsequently, the expression of four hub proteins was verified by ELISA in clinical samples with an expanded sample size. Considering the consistency with proteomic results, CELA3A, CELA3B, and CTRC were finally determined for further analysis. The ROC analysis found that they performed well in distinguishing NPDR/PDR from DM. In addition, there is a significant correlation between CELA3A, CELA3B, and CTRC proteins and some clinical indicators of DR. These findings may provide new insights into the identification of biomarkers in the progression of DR and are expected to guide clinical diagnosis.

In this study, we found that the majority of DEPs were located in synapses and mitochondria, participating in synaptic transmission functions such as neurotransmitter uptake and secretion regulation. The occurrence of DR is caused by long-term hyperglycemia in DM patients, damaging retinal neural and vascular components27 and gradually deteriorating from NPDR to PDR as the condition progresses. It was reported that retinal neurodegeneration in DR was triggered by the disruption of synaptic and mitochondrial functions28. A study showed that neurotransmitters such as GABA, glutamate, and VEGF co-participated in the occurrence and development of PDR by regulating the excitability of retinal neurons and affecting the structure and function of retinal blood vessels29. Miller et al. found that mechanisms, such as impaired mitochondrial function and oxidative stress, may lead to abnormal energy metabolism of retinal neurons and abnormal vascular structural function in DR30. In summary, the present study, together with the existing evidence, reveals that the dysregulation of synaptic transmission and mitochondrial dysfunction are pivotal in DR progression, potentially disrupting the homeostasis of retinal neuro-vascular components and driving its pathological process.

CELA3A and CELA3B are isoforms of human chymotrypsin Like elastase family member 3 (CELA3) and secreted by the pancreas31. A study found that CELA3A protoform and CELA3B active form existed in the islet microenvironment of type 2 diabetic patients, and the latter played a role by regulating endocrine cell function32. The specific expression of CELA3A in mucinous pancreatic cysts suggested that it may affect the normal function of the pancreas33. CELA3B gene mutation increased its translation rate, thereby increasing the total amount of active enzymes, leading to pancreatic dysfunction and increasing the incidence of diabetes in patients with pancreatitis34. CTRC, named as chymotrypsin C, protects pancreatic function by degrading activated trypsinogen35. A study found that the frequency of the c.738_761del mutation in the CTRC gene was significantly higher in diabetic patients than in non-diabetic patients36, suggesting that CTRC may be involved in DM development by affecting pancreatic function. Although no study has directly reported the association of CELA3A, CELA3B, or CTRC with DR, insufficient insulin secretion and poor blood glucose control caused by abnormal pancreatic function have been confirmed to be the key factors in the occurrence and development of DR37,38. Therefore, it is speculated that these proteins may affect DR progression by regulating pancreatic secretory function to influence blood glucose homeostasis and retinal health. Furthermore, ROC curve analysis confirmed that the AUC values of the three hub proteins and their composed panels in distinguishing NPDR/PDR from DM were all > 0.7, except for DM-NPDR of CELA3B. Collectively, the plasma EV proteins CELA3A, CELA3B, and CTRC may serve as biomarkers for monitoring the progression from DM to DR, and affect pancreatic function to regulate the DR progression.

In addition, clinical indicators have important guiding significance for the different stages of DR. Our study revealed the correlations between CELA3A/CELA3B/CTRC and clinical indicators during the DR progression. The positive correlation of CELA3A/CTRC with the duration of DR and TG levels may reflect its potential role in lipid metabolism disorders during chronic hyperglycemia. This was consistent with the previous report that TG was an important determinant of elevated plasma pigment epithelium-derived factor levels, which was in turn correlated with DR progression39. In addition, a prospective 15-year follow-up study revealed that HDL cholesterol was a protective predictor of DR occurrence and progression40. Our study’s finding of a negative correlation between CELA3B/CTRC and HDL during DR progression aligned with the above report, further supporting HDL’s protective role in DR. Similarly, the positive correlation between CELA3B and Ca levels paralleled the previously reported elevation in serum Ca gradient from DM to NPDR and then to PDR41, suggesting possible involvement in vascular calcification processes. These coordinated associations implied that these three hub proteins might serve as a molecular bridge between metabolic disturbances and microvascular damage. This provides a theoretical basis for explaining why some patients with chronic dyslipidemia tend to develop a more severe DR phenotype42,43.

This study identified potential DR biomarkers CELA3A, CELA3B, and CTRC through proteomic analysis of plasma EVs across DR stages. These findings deepened the understanding of DR progression characteristics and enriched the types of biomarkers in previous studies, such as antimicrobial peptides and inflammatory mediators in tears, and IgG Fc glycosylation patterns and lipid metabolites in serum44,45,46. Future research could further integrate these biomarkers to explore their combined application potential in DR diagnosis. However, our research still has some limitations and deficiencies. Firstly, the research scale of the discovery and validation cohorts was relatively small. Secondly, the expression level of GLUD1 verified by ELISA was inconsistent with the proteomic results, which may be caused by the large heterogeneity of clinical samples. We will expand the sample size for verification in the future. Thirdly, plasma EV proteins, CELA3A, CELA3B, and CTRC, showed promise as DR progression biomarkers, but their clinical application was limited by the complex EV isolation and purification, high detection costs, and lack of standardized procedures. Future work will compare the performance of these markers in EVs and total plasma and optimize EV detection protocols to promote their application. Finally, we found that DR progression may be related to impaired pancreatic function, and no relevant reports have confirmed this association between them. Therefore, further in vivo and in vitro experiments are needed to verify how hub proteins regulate pancreatic function to participate in DR Progression. Despite some shortcomings, the preliminary research still provides relatively meaningful and instructive findings.

Conclusions

Taken together, 32 DEPs were identified by investigating the protein profile of plasma EVs from patients at different stages of DR. ELISA experiments further determined three hub proteins (CELA3A, CELA3B, and CTRC), whose expression level was consistent with proteomics results. ROC analysis showed AUC values > 0.7 for three hub proteins and their panels in distinguishing NPDR/PDR from DM, except for CELA3B in DM-NPDR. These findings indicate that CELA3A, CELA3B, and CTRC are expected to serve as biomarkers for monitoring the progression from DM to DR and providing effective guidance for disease diagnosis.

Data availability

The raw data had been uploaded to the PRIDE data storage platform (https://www.ebi.ac.uk/pride/archive) under ProteomeXchange, with the identifier PXD064059.

References

Cheung, N., Mitchell, P. & Wong, T. Y. Diabetic retinopathy. Lancet 376, 124–136. https://doi.org/10.1016/s0140-6736(09)62124-3 (2010).

Teo, Z. L. et al. Global prevalence of diabetic retinopathy and projection of burden through 2045: systematic review and Meta-analysis. Ophthalmology 128, 1580–1591. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ophtha.2021.04.027 (2021).

Hou, X. et al. Prevalence of diabetic retinopathy and vision-threatening diabetic retinopathy in adults with diabetes in China. Nat. Commun. 14, 4296. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41467-023-39864-w (2023).

Wang, W. & Lo, A. C. Y. Diabetic retinopathy: pathophysiology and treatments. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 19 https://doi.org/10.3390/ijms19061816 (2018).

Stitt, A. W. et al. The progress in Understanding and treatment of diabetic retinopathy. Prog Retin Eye Res. 51, 156–186. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.preteyeres.2015.08.001 (2016).

Liu, Y. & Wu, N. Progress of nanotechnology in diabetic retinopathy treatment. Int. J. Nanomed. 16, 1391–1403. https://doi.org/10.2147/ijn.S294807 (2021).

Welsh, J. A. et al. Minimal information for studies of extracellular vesicles (MISEV2023): from basic to advanced approaches. J. Extracell. Vesicles. 13, e12404. https://doi.org/10.1002/jev2.12404 (2024).

Cocozza, F. et al. Extracellular Vesicles. Cell. 182, 262–262 e261 (2020). https://doi.org/10.1016/j.cell.2020.04.054

Hua, Y., Jiang, P., Dai, C. & Li, M. Extracellular vesicle autoantibodies. J. Autoimmun. 149, 103322. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jaut.2024.103322 (2024).

Zhang, Y. et al. Advances in therapeutic applications of extracellular vesicles. Int. J. Nanomed. 18, 3285–3307. https://doi.org/10.2147/IJN.S409588 (2023).

Zhu, J., Huang, J., Sun, Y., Xu, W. & Qian, H. Emerging role of extracellular vesicles in diabetic retinopathy. Theranostics 14, 1631–1646. https://doi.org/10.7150/thno.92463 (2024).

Chen, T., Wang, F., Wei, J. & Feng, L. Extracellular vesicles derived from different sources play various roles in diabetic retinopathy. Front. Endocrinol. (Lausanne). 13, 1064415. https://doi.org/10.3389/fendo.2022.1064415 (2022).

Mighty, J. et al. Extracellular vesicles of human diabetic retinopathy retinal tissue and urine of diabetic retinopathy patients are enriched for the junction Plakoglo Bin protein. Front. Endocrinol. (Lausanne). 13, 1077644. https://doi.org/10.3389/fendo.2022.1077644 (2022).

Wang, P. et al. Effect of plasma-derived extracellular vesicles on angiogenesis and the ensuing proliferative diabetic retinopathy through a miR-30b-dependent mechanism. Diabetol. Metab. Syndr. 14, 188. https://doi.org/10.1186/s13098-022-00937-3 (2022).

Li, N. et al. Potent prophylactic cancer vaccines Harnessing surface antigens shared by tumour cells and induced pluripotent stem cells. Nat. Biomed. Eng. 9, 215–233. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41551-024-01309-0 (2025).

Shen, H. P. et al. Protein profiles and novel molecular biomarkers of schizophrenia based on 4D-DIA proteomics. J. Proteome Res. 23, 2376–2385. https://doi.org/10.1021/acs.jproteome.4c00040 (2024).

Sherman, B. T. et al. DAVID: a web server for functional enrichment analysis and functional annotation of gene lists (2021 update). Nucleic Acids Res. 50, W216–w221. https://doi.org/10.1093/nar/gkac194 (2022).

Huang da, W., Sherman, B. T. & Lempicki, R. A. Systematic and integrative analysis of large gene lists using DAVID bioinformatics resources. Nat. Protoc. 4, 44–57. https://doi.org/10.1038/nprot.2008.211 (2009).

Kanehisa, M., Sato, Y., Kawashima, M., Furumichi, M. & Tanabe, M. KEGG as a reference resource for gene and protein annotation. Nucleic Acids Res. 44, D457–462. https://doi.org/10.1093/nar/gkv1070 (2016).

Kanehisa, M. & Goto, S. KEGG: Kyoto encyclopedia of genes and genomes. Nucleic Acids Res. 28, 27–30. https://doi.org/10.1093/nar/28.1.27 (2000).

Szklarczyk, D. et al. The STRING database in 2023: protein-protein association networks and functional enrichment analyses for any sequenced genome of interest. Nucleic Acids Res. 51, D638–d646. https://doi.org/10.1093/nar/gkac1000 (2023).

Subirana, I., Sanz, H. & Vila, J. Building bivariate tables: the comparegroups package for R. J. Stat. Softw. 57, 1–16. https://doi.org/10.18637/jss.v057.i12 (2014).

Samaeekia, R. et al. Effect of human corneal mesenchymal stromal Cell-derived exosomes on corneal epithelial wound healing. Invest. Ophthalmol. Vis. Sci. 59, 5194–5200. https://doi.org/10.1167/iovs.18-24803 (2018).

Xiao, Q. et al. Brain-Derived Exosomal MiRNA profiles upon experimental SAE rats and their comparison with peripheral exosomes. Mol. Neurobiol. 61, 772–782. https://doi.org/10.1007/s12035-023-03569-4 (2024).

Curtis, T. M., Gardiner, T. A. & Stitt, A. W. Microvascular lesions of diabetic retinopathy: clues towards Understanding pathogenesis? Eye (Lond). 23, 1496–1508. https://doi.org/10.1038/eye.2009.108 (2009).

Alberro, A., Iparraguirre, L., Fernandes, A. & Otaegui, D. Extracellular vesicles in blood: sources, effects, and applications. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 22 https://doi.org/10.3390/ijms22158163 (2021).

Serikbaeva, A., Li, Y., Ma, S., Yi, D. & Kazlauskas, A. Resilience to diabetic retinopathy. Prog Retin Eye Res. 101, 101271. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.preteyeres.2024.101271 (2024).

Zhu, H. et al. GSK3beta-mediated Tau hyperphosphorylation triggers diabetic retinal neurodegeneration by disrupting synaptic and mitochondrial functions. Mol. Neurodegener. 13, 62. https://doi.org/10.1186/s13024-018-0295-z (2018).

Ambati, J. et al. Elevated gamma-aminobutyric acid, glutamate, and vascular endothelial growth factor levels in the vitreous of patients with proliferative diabetic retinopathy. Arch. Ophthalmol. 115, 1161–1166. https://doi.org/10.1001/archopht.1997.01100160331011 (1997).

Miller, D. J., Cascio, M. A. & Rosca, M. G. Diabetic retinopathy: the role of mitochondria in the neural retina and microvascular disease. Antioxid. (Basel). 9 https://doi.org/10.3390/antiox9100905 (2020).

Boros, E. et al. Overlapping specificity of duplicated human pancreatic elastase 3 isoforms and archetypal Porcine elastase 1 provides clues to evolution of digestive enzymes. J. Biol. Chem. 292, 2690–2702. https://doi.org/10.1074/jbc.M116.770560 (2017).

Basile, G. et al. Excess pancreatic elastase alters acinar-beta cell communication by impairing the mechano-signaling and the PAR2 pathways. Cell. Metab. 35, 1242–1260. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.cmet.2023.05.007 (2023). e1249.

Park, J. et al. Discovery and validation of biomarkers that distinguish mucinous and nonmucinous pancreatic cysts. Cancer Res. 75, 3227–3235. https://doi.org/10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-14-2896 (2015).

Moore, P. C. et al. Elastase 3B mutation links to Familial pancreatitis with diabetes and pancreatic adenocarcinoma. J. Clin. Invest. 129, 4676–4681. https://doi.org/10.1172/JCI129961 (2019).

Stefanovics, R. et al. Novel chymotrypsin C (CTRC) variants from real-world genetic testing of pediatric chronic pancreatitis cases. Pancreatology 24, 690–697. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.pan.2024.06.003 (2024).

Cichoz-Lach, H., Michalak-Wojnowska, M., Lis-Janczarek, E., Wojcierowski, J. & Hydzik, M. Do CTRC mutations affect the development of alcoholic chronic pancreatitis and its course among poles: preliminary study. Adv. Clin. Exp. Med. 28, 307–312. https://doi.org/10.17219/acem/76130 (2019).

Matthews, J. et al. Determining the role of SGLT2 Inhibition with empagliflozin in the development of diabetic retinopathy. Biosci. Rep. 42 https://doi.org/10.1042/BSR20212209 (2022).

Ipp, E. Diabetic retinopathy and insulin insufficiency: beta cell replacement as a strategy to prevent blindness. Front. Endocrinol. (Lausanne). 12, 734360. https://doi.org/10.3389/fendo.2021.734360 (2021).

Ogata, N. et al. Plasma concentration of pigment epithelium-derived factor in patients with diabetic retinopathy. J. Clin. Endocrinol. Metab. 92, 1176–1179. https://doi.org/10.1210/jc.2006-2249 (2007).

Tomic, M., Vrabec, R., Bulum, T. & Ljubic, S. HDL cholesterol is a protective predictor in the development and progression of retinopathy in type 1 diabetes: A 15-year follow-up study. Diabetes Res. Clin. Pract. 186, 109814. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.diabres.2022.109814 (2022).

Ankita et al. Retinal photoreceptor apoptosis is associated with impaired serum ionized calcium homeostasis in diabetic retinopathy: an in-vivo analysis. J. Diabetes Complications. 33, 208–211. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jdiacomp.2018.12.003 (2019).

Zhang, X. et al. Dysregulated serum lipid metabolism promotes the occurrence and development of diabetic retinopathy associated with upregulated Circulating levels of VEGF-A, VEGF-D, and PlGF. Front. Med. (Lausanne). 8, 779413. https://doi.org/10.3389/fmed.2021.779413 (2021).

Srinivasan, S., Raman, R., Kulothungan, V., Swaminathan, G. & Sharma, T. Influence of serum lipids on the incidence and progression of diabetic retinopathy and macular oedema: Sankara Nethralaya diabetic retinopathy epidemiology and molecular genetics Study-II. Clin. Exp. Ophthalmol. 45, 894–900. https://doi.org/10.1111/ceo.12990 (2017).

Amorim, M. et al. Putative biomarkers in tears for diabetic retinopathy diagnosis. Front. Med. (Lausanne). 9, 873483. https://doi.org/10.3389/fmed.2022.873483 (2022).

Mao, Y. et al. Serum Disease-Specific IgG Fc glycosylation as potential biomarkers for nonproliferative and proliferative diabetic retinopathy using mass spectrometry. Mol. Cell. Proteom. 24, 100967. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.mcpro.2025.100967 (2025).

Sun, W. et al. Clinical serum lipidomic profiling revealed potential lipid biomarkers for early diabetic retinopathy. Sci. Rep. 14, 15148. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-024-66157-z (2024).

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

Hang Wu and Zhen Li conceived and designed this study. Zhen Li, Xiaojing Pang, Junyuan Zhang, and Zhili Wang collected and organized the sample data. Hang Wu, Zhen Li and Xiaojing Pang analyzed the experimental data, wrote and revised the manuscript. All authors read and approved the final manuscript.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Ethics approval and consent to participate

This study design complied with the principles of the Declaration of Helsinki and was approved by the Ethics Committee of Xuanwu Hospital of Capital Medical University (2023-046). Written informed consents were obtained from all individuals.

Additional information

Publisher’s note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Supplementary Information

Below is the link to the electronic supplementary material.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if you modified the licensed material. You do not have permission under this licence to share adapted material derived from this article or parts of it. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Li, Z., Pang, X., Wu, H. et al. Identification of plasma extracellular vesicle protein biomarkers in diabetic retinopathy progression. Sci Rep 15, 35384 (2025). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-19223-z

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-19223-z