Abstract

This article presents an optimized low-power, energy-efficient, high-resolution Sigma-Delta Analog-to-Digital Converter (\(\Sigma\)-\(\Delta\) ADC) for biomedical IoT (Internet of Things) applications. Advances in technology demand IoT devices to process huge data with high precision and lower power dissipation. This increases the expectations from data converters used in these portable devices. The \(\Sigma\)-\(\Delta\) ADC proposed in this work is designed and analyzed using a 180 nm SCL CMOS technology node in the Cadence Virtuoso environment. \(\Sigma\)-\(\Delta\) modulator uses a folded-cascode and a two-stage amplifier to achieve an optimal balance between power consumption and accuracy. The folded-cascode amplifier exhibits a gain of 76 dB, a phase margin of \(56^\circ\), and a power consumption of 250 \(\upmu \hbox {W}\). In comparison, the two-stage amplifier produces a gain of 80.5 dB, a phase margin of \(64^\circ\), and a significantly lower power dissipation of 72 \(\upmu \hbox {W}\). To further reduce power, a dynamic comparator circuit is employed in the binary quantizer to replace the two-stage amplifier. The modulator samples at a clock frequency of 1.28 MHz and converts the analog signal into high-frequency digital bit streams. The digital filter and decimation block are designed together. A second-order Cascoded Integrator Comb (CIC) filter is designed. The designed filter replaces the traditional integrator with a counter to optimize power consumption. The filter decimates the high-frequency pulse code modulated bit stream into a 14-bit resolution digital signal. This article also presents in-depth the transistor-level designs of all components used, along with certain important aspects of the design procedure. The post layout results demonstrate that the \(\Sigma\)-\(\Delta\) converter attains an Effective Number of Bits (ENOB) of 13.995, a Signal-to-Noise Ratio (SNR) of 84.8 dB, and a Figure of Merit (FOM) of 20.41 fJ/conversion. With an oversampling ratio (OSR) of 128, the ADC operates efficiently, consuming only 0.498 mW of power. The layout area of the proposed ADC is \(0.0896~\text {mm}^2\). The proposed ADC design meets the performance requirements of biomedical IoT devices.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

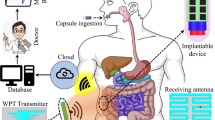

Analog techniques have historically been the foundation of signal processing, known for their precision and simplicity. However, the advancement of digital technology has resulted in a growing shift toward digital techniques in this domain1. Various Analog-to-Digital Converters (ADCs) exist, each suited for different applications. Successive Approximation Register (SAR) ADCs offer moderate resolution and power efficiency, making them ideal for medium-speed applications2,3. Flash ADCs provide extremely high-speed conversion but at the cost of significant power consumption and hardware complexity4. Pipeline ADCs achieve high resolution and speed but require multiple processing stages, increasing latency and power usage5. In contrast, \(\Sigma\)-\(\Delta\) ADCs are exceptionally appropriate for applications requiring low power consumption and high resolution, such as biomedical signal acquisition and sensor-based IoT systems6. They exemplify the evolution of mixed-signal design with a hybrid architecture, consisting of approximately 75% digital and 25% analog circuitry7. By leveraging oversampling and noise shaping, \(\Sigma\)-\(\Delta\) ADCs achieve superior Signal-to-Noise Ratio (SNR) and Effective Number Of Bits (ENOB) while minimizing quantization noise in the desired bandwidth. This makes them the preferred choice for applications that demand precise, low-frequency signal conversion with minimal power constraints. This unique architecture enables \(\Sigma\)-\(\Delta\) ADC to achieve high resolution, effective noise shaping, and the ability to convert analog signals across a wide frequency spectrum, ranging from DC to several megahertz8. In the context of the biomedical Internet of Things (IoT) applications, where continuous, accurate, and energy-efficient monitoring is essential, \(\Sigma\)-\(\Delta\) ADCs have emerged as a cornerstone technology9. The Analog Front End (AFE) in biomedical IoT devices is responsible for acquiring and processing physiological signals such as electrocardiograms (ECG)10, electroencephalograms (EEG)11, and photoplethysmograms (PPG)12, which typically exhibit low amplitude and low frequency13,14. To meet the stringent requirements of high precision, noise resilience, and low power consumption, the AFE is highly dependent on the \(\Sigma\)-\(\Delta\) ADC15.

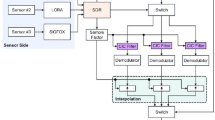

Analog Front End (AFE) for biomedical IoT applications, comprising biomedical sensors(implantable, non-implantable), a \(\Sigma\)-\(\Delta\) modulator, a digital filter, and a decimator. The AFE facilitates the accurate acquisition and conversion of physiological signals into high-resolution digital outputs, enabling efficient real-time monitoring and analysis.

This ADC leverages oversampling and noise-shaping techniques to ensure high-resolution data acquisition while suppressing quantization noise, enabling clean and accurate signal processing even in noisy environments or during patient movement28. Table 1 shows the list of abbreviations used in this paper. The development of \(\Sigma\)-\(\Delta\) ADC has seen significant advancements over the years. Early \(\Sigma\)-\(\Delta\) converters introduced oversampling and noise-shaping techniques to achieve high resolution, but their high power consumption and large silicon area limited their application in resource-constrained environments such as IoT and biomedical systems29. Subsequent efforts improved Signal-to-Noise Ratio (SNR) and Effective Number of Bits (ENOB) through higher-order modulators and advanced noise-shaping techniques30. However, these designs increased circuit complexity and power requirements, making them unsuitable for wearable and implantable devices requiring low-power operation31. Research into AFEs for biomedical IoT highlighted the need for ADCs capable of precise low-frequency signal acquisition while operating efficiently under strict power constraints2. Traditional CIC filters used for digital decimation further faced challenges in power consumption due to their adder-based integrators, which occupied substantial silicon area32.

Biomedical IoT devices, such as wearable health monitors and implantable systems, operate under strict power constraints and require compact form factors33,34. The inherently low power consumption of \(\Sigma\)-\(\Delta\) ADC extends the battery life, enabling continuous monitoring in these applications35. Also, their compact integration allows them to be seamlessly incorporated into small-scale devices like wearable health monitors and portable diagnostic tools36. By processing low-frequency signals (e.g., 0.05–1000 Hz for ECG) with minimal distortion, \(\Sigma\)-\(\Delta\) ADC captures subtle physiological variations critical for accurate diagnostics37. Table 1 highlights the requirements for a 14-bit \(\Sigma\)-\(\Delta\) ADC across biomedical applications like ECG, EEG, and pulse oximetry, with sampling rates ranging from 1 Hz to 20 kHz, signal amplitudes from 0.01 to 200 mVpp, and power consumption under 300 \(\upmu \hbox {W}\). These specifications ensure energy-efficient and accurate signal conversion for each application. Combined with IoT-enabled communication systems, the AFE facilitates real-time data acquisition, seamless transmission to cloud platforms, and remote monitoring as shown in Figure 1. This article presents the design and implementation of an energy-efficient and high-resolution \(\Sigma\)-\(\Delta\) ADC optimized for IoT applications. The proposed design, implemented using a 180 nm technology node in the Cadence Virtuoso environment, incorporates innovative techniques to balance power efficiency and performance. It features a first-order \(\Sigma\)-\(\Delta\) modulator and a second-order Cascaded Integrator Comb (CIC) filter. The modulator employs two distinct operational amplifier architectures: a folded-cascode topology for stability and a two-stage amplifier for minimizing power consumption. The CIC filter uses a counter-based integrator, significantly reducing both power consumption and silicon area. The study highlights the practical effectiveness of \(\Sigma\)-\(\Delta\) ADCs in addressing the energy constraints of biomedical IoT applications, while laying a robust groundwork for future enhancements. Advancements such as higher-order modulator designs, sophisticated digital filtering techniques, and the adoption of more advanced CMOS technology nodes can further optimize energy efficiency and enhance precision.

This paper is organized as follows: Section “Novelty in propsed \(\Sigma\)-\(\Delta\) modulator design” introduces the innovative aspects of the proposed work, highlighting the integration of techniques such as virtual ground implementation, hybrid operational amplifier architectures, and counter-based integrators in the Cascaded Integrator Comb (CIC) filter, aimed at optimizing power, resolution, and energy efficiency. Section “Sigma-delta ADC: design methodology” provides a detailed explanation of the working principle and architecture of the proposed \(\Sigma\)-\(\Delta\) modulator, focusing on key components such as the summing amplifier, integrator, comparator, and feedback loop, and illustrating how oversampling and noise shaping contribute to enhanced resolution. Section “Proposed modulator designing blocks” details the design of the proposed modulator blocks, focusing on the implementation of operational amplifiers and dynamic comparators, with a particular emphasis on optimizing power efficiency and ensuring accuracy. Section “Proposed digital filter design” describes the design of the digital filter, focusing on how it processes the high-frequency bitstream generated by the modulator. Section “VI” presents the simulation results, validating the proposed design in terms of signal-to-noise ratio (SNR), effective number of bits (ENOB), figure of merit (FOM) for energy efficiency, and power consumption. Section “Design methodology for CIC filter” details the Design Methodology for the CIC filter, including the integration of counter-based integrators to achieve efficient power consumption and reduced silicon area. Finally, Section “Conclusion” concludes the paper, summarizing the findings and suggesting future research directions, such as exploring higher-order modulators and transitioning to advanced CMOS technology nodes.

Novelty in propsed \(\Sigma\)-\(\Delta\) modulator design

This work introduces several innovative techniques in the design of a \(\Sigma\)-\(\Delta\) ADC for energy-efficient and high-resolution IoT applications. The novelty of the design lies in the integration of unique circuit-level optimizations and architectural choices to achieve a balance between power consumption, resolution, and area efficiency.

-

1.

Virtual Ground Implementation: A novel virtual ground concept is employed within the \(\Sigma\)-\(\Delta\) modulator. By utilizing a summing amplifier instead of a traditional difference amplifier, the input signal is shifted to match the required voltage range for the integrator. This approach ensures effective charging and discharging of the integrator capacitor without the need for dual-supply configurations or voltage clipping. The virtual ground implementation simplifies the design and enhances the overall stability of the modulator.

-

2.

Hybrid Operational Amplifier Architectures: To address the conflicting requirements of performance and power efficiency, two distinct operational amplifier (op-amp) designs are integrated into the modulator. A folded-cascode amplifier with Wide-Swing Cascode Current Mirror (WSCCM) biasing is used in the summing amplifier to achieve high gain, wide output swing, and robust stability. A two-stage amplifier is utilized for the integrator and binary quantizer (comparator), effectively minimizing power consumption while maintaining adequate gain and phase margins. This hybrid design reduces the modulator’s total power consumption by 356 \(\upmu \hbox {W}\) (43.95%), enhancing its efficiency for IoT applications. To achieve further power savings, dynamic comparator circuits can replace operational amplifiers in the binary quantizer, offering a more energy-efficient solution.

-

3.

Counter-Based Integrator in the Digital Filter: The design replaces traditional adder-based integrators in the Cascaded Integrator Comb (CIC) filter with a counter-based implementation. This substitution minimizes the power dissipation of the digital filter by 30%. The counter-based integrator also simplifies the design process and enhances the filter’s scalability for future modifications.

These innovations collectively contribute to a highly optimized \(\Sigma\)-\(\Delta\) ADC that operates efficiently within the power and performance constraints of IoT devices. By combining virtual ground techniques, hybrid op-amp architectures, and power-saving digital filter designs, this work sets a foundation for further advancements in energy-efficient, high-resolution data converters.

Sigma-delta ADC: design methodology

A fundamental \(\Sigma\)-\(\Delta\) converter functions as a single-bit sampling system. It necessitates that the input analog signal change gradually, allowing the converter to sample it several times, a technique called oversampling. The sampling rate is much higher than the rate at which the digital outputs are generated. Each sample is integrated over time and combined with other input signal samples using the digital filter. This converter primarily consists of two key components: the \(\Sigma\)-\(\Delta\) modulator and the digital/decimation filter. The \(\Sigma\)-\(\Delta\) modulator, as shown in Figure 2, performs coarse sampling of the input signal at an extremely high rate, converting it into a 1-bit data stream. This stream is then processed by the digital filter, which transforms the sampled data into a high-resolution, slower digital output. Unlike conventional converters with a single sample rate, the \(\Sigma\)-\(\Delta\) converter operates with two distinct rates: the input sampling rate (\(F_S\)) and the output data rate (\(F_D\)).

Block diagram of a complete \(\Sigma\)-\(\Delta\) proposed modulator illustrating its primary components: the summing amplifier, analog integrator, and binary quantizer. The summing amplifier combines the input signal (\(V_s\)) with feedback (\(Q_z\)) using capacitive coupling (\(C_{add1}\) and \(C_{add2}\)). The analog integrator, consisting of resistors (\(R_{in}\)) and a feedback capacitor (\(C_f\)), accumulates the signal over time. The binary quantizer, implemented with a comparator (\(V_{comp}\)) and latch, converts the analog signal into a digital output (\(Q_z\)). This architecture enables the redistribution of quantization noise and enhances the signal-to-noise ratio in the desired frequency band.

Modulator working principle

The \(\Sigma\)-\(\Delta\) modulator serves as the core of the \(\Sigma\)-\(\Delta\) ADC. The working principle of the \(\Sigma\)-\(\Delta\) modulator revolves around oversampling and noise shaping to achieve high-resolution signal conversion. It operates by first oversampling the input analog signal at a rate significantly higher than the Nyquist rate, which spreads the quantization noise over a wider frequency band. The architecture typically consists of a differential amplifier, an integrator, a 1-bit quantizer (ADC), and a feedback loop incorporating a digital-to-analog converter (DAC). The integrator accumulates the difference between the input signal and the feedback signal, effectively shaping the quantization noise by pushing it to higher frequencies, where it can be filtered out. The 1-bit quantizer converts the analog signal into a high-frequency digital bitstream, while the feedback loop ensures stability and minimizes distortion. This modulated bitstream is then processed by a digital filter and decimator, which extract the desired signal band and reduce the sampling rate, producing a high-resolution digital output suitable for subsequent processing. This architecture makes the \(\Sigma\)-\(\Delta\) modulator particularly effective for low-frequency, high-precision applications, such as biomedical signal acquisition in IoT devices.

Oversampling in \(\Sigma\)-\(\Delta\) ADC

Oversampling in \(\Sigma\)-\(\Delta\) ADC is crucial in achieving high-resolution and low-noise performance by leveraging mathematical relationships between sampling frequency, noise shaping, and signal-to-noise ratio (SNR). The oversampling ratio (OSR) is mathematically defined in Eq. 1 as the ratio of the sampling frequency \(f_s\) to twice the signal bandwidth \(f_B\):

Increasing the OSR spreads the quantization noise over a broader frequency range. The total quantization noise power (\(P_Q\)) in a Nyquist ADC is expressed in Eq. 2:

where \(\Delta\) represents the quantization step size. For an oversampled system, only a fraction of this noise power falls within the signal bandwidth, as shown in Eq. 3:

This reduction in in-band quantization noise enhances the SNR, which for a first-order \(\Sigma\)-\(\Delta\) modulator is given by Eq. 4:

Here, N represents the effective number of bits (ENOB). Higher-order modulators further improve the SNR by aggressively shaping the quantization noise. The general SNR for an Lth-order modulator is approximated by Eq. 5:

As seen from Eq. 5, increasing the OSR or the modulator order L results in a substantial improvement in SNR. This enables higher resolution, which is crucial for precision-demanding applications. However, higher OSR and modulator orders demand more power and complexity, particularly in the digital decimation filter that removes out-of-band noise. Another significant advantage of oversampling is the relaxed design of the anti-aliasing filter. Since the sampling frequency \(F_s\) is much higher than the Nyquist rate, the cutoff frequency of the filter can be relaxed, allowing the use of lower-order analog filters. Oversampling combined with noise shaping provides a mathematical framework to achieve high-resolution data conversion in \(\Sigma\)-\(\Delta\) ADC, essential for biomedical signal monitoring and audio signal processing applications.

Noise shaping

Noise shaping is a fundamental feature of \(\Sigma\)-\(\Delta\) converters that enhances their resolution and accuracy by effectively managing quantization noise. In a \(\Sigma\)-\(\Delta\) modulator, the quantization noise is redistributed across the frequency spectrum through oversampling and feedback. The integrator within the modulator plays a key role by accumulating the error between the input signal and the feedback signal, thereby pushing the majority of the quantization noise to higher frequencies outside the signal bandwidth. This process reduces the noise within the desired signal band, enabling precise representation. A digital low-pass filter and decimator then process the output bitstream, removing the high-frequency noise while downsampling to the required rate. This noise-shaping technique makes \(\Sigma\)-\(\Delta\) ADC highly suitable for low-frequency and high-precision applications, such as biomedical signal acquisition, where capturing subtle variations with minimal noise interference is critical. The Figure 3 illustrates the progression of quantization noise management in a \(\Sigma\)-\(\Delta\) modulation system. Initially, quantization noise is uniformly distributed across the frequency spectrum up to the Nyquist frequency (\(F_s/2\)), as shown in the leftmost plot. This is typical in conventional quantization, where noise affects the entire frequency range equally. In the middle plot, noise shaping is introduced, a technique that redistributes quantization noise, pushing most of the noise energy to higher frequencies beyond the Nyquist limit (\(K \cdot F_s/2\), where \(K > 1\)). This reduces the noise within the desired low-frequency signal band, thereby improving the signal-to-noise ratio (SNR) in this region. At the end, the rightmost plot demonstrates the effect of combining noise shaping with digital filtering. The high-frequency noise introduced by noise shaping is effectively removed using a digital low-pass filter, leaving a cleaner, high-resolution signal in the target frequency band. This process is fundamental in oversampled ADC and digital signal processing, enabling precise signal reconstruction with minimal quantization noise.

Illustration of quantization noise distribution in three scenarios: (1) Uniform quantization noise across the frequency spectrum up to the Nyquist frequency (Fs/2); (2) Redistribution of quantization noise using noise shaping, which pushes noise energy to higher frequencies beyond the Nyquist limit; (3) Application of noise shaping combined with digital filtering to remove high-frequency quantization noise, improving signal quality within the desired frequency range.

Virtual ground

In the context of the Sigma-Delta (\(\Sigma\)-\(\Delta\)) ADC used in this work, the virtual ground concept plays a pivotal role in maintaining the accuracy and stability of the modulator’s operation. A \(\Sigma\)-\(\Delta\) ADC relies heavily on precision components such as operational amplifiers (op-amps) and feedback loops to shape and suppress noise. Within the \(\Sigma\)-\(\Delta\) modulator, the virtual ground serves as a stable reference point at a fixed voltage, often set at mid-supply, ensuring that the input signal and feedback signal are processed with minimal interference. In this configuration, the inverting input of the amplifier serves as a virtual ground. Although it is not physically connected to ground, this node is held at a stable potential due to the high gain of the operational amplifier and the presence of negative feedback. As a result, it behaves like a ground from the perspective of the signal path, allowing precise charge sharing between the input and feedback capacitors. This virtual ground behavior is critical for accurate integration of the input and DAC signals.

In this architecture, the virtual ground ensures that the inverting input of the op-amp, used in the integrator stage, operates at the same potential as the non-inverting input. This allows for precise integration of the input signal and accurate conversion of the analog signal into a 1-bit digital stream. By providing a stable reference, the virtual ground minimizes common-mode noise, reduces errors caused by voltage fluctuations, and enhances the linearity of the system. This stability is particularly critical in applications where the \(\Sigma\)-\(\Delta\) ADC must process low-amplitude biomedical signals, such as ECG or EEG, with high fidelity. The virtual ground concept thus contributes to the overall efficiency and precision of the \(\Sigma\)-\(\Delta\) ADC, making it a robust choice for energy-efficient and high-resolution IoT-enabled biomedical devices.

Proposed modulator designing blocks

The design of the proposed \(\Sigma\)-\(\Delta\) modulator centers around key building blocks, each contributing to its high-resolution and energy-efficient operation. The operational amplifier (op-amp) serves as a critical component in the integrator and comparator stages. Two distinct op-amp architectures are used: a folded-cascode design for stability and precision, and a two-stage design for reduced power consumption. The folded-cascode amplifier, biased using a Wide-Swing Cascode Current Mirror (WSCCM), as shown in Fig. 4a, provides high DC gain, wide output swing, and excellent stability. The folded-cascode configuration increases output resistance by stacking transistors in a cascode arrangement. This high output resistance, combined with high transconductance in the input stage, results in a high open-loop gain. The use of WSCCM biasing enhances voltage headroom by allowing both NMOS and PMOS current mirrors to operate efficiently near the supply rails. This improves the output voltage range without compromising bias stability. Unlike conventional cascode mirrors, WSCCM allows for greater drain voltage swing by ensuring that the cascoded transistors are not strictly limited by \(V_{DS}\) (sat) of the upper devices. The folded-cascode architecture naturally provides greater phase margin and good common-mode rejection, which helps stabilize feedback loops in the presence of signal or power supply variations. Also, the use of a common-mode feedback (CMFB) circuit ensures that the output common-mode level is tightly regulated, further enhancing stability across PVT corners. In contrast, the two-stage op-amp, illustrated in Fig. 4b, focuses on reducing power consumption while meeting essential performance requirements such as phase margin, unity-gain bandwidth (UGB), and noise minimization. In addition, the dynamic latch technique is used to design comparators, as demonstrated in the Fig. 538. These dynamic comparators offer an energy-efficient alternative to op-amps, further optimizing the modulator’s overall power consumption for resource-constrained applications.

In this work, four dynamic comparator topologies, Modified Strong-Arm, Miyahara, Three-Stage, and Footless, were considered for evaluation based on their relevance in low-power and high-speed ADC architectures. Each structure was simulated and benchmarked across key performance parameters, including delay, power consumption, energy per comparison, input-referred noise, and kickback noise. The Footless comparator was selected for implementation in the \(\Sigma\)-\(\Delta\) modulator due to its balanced performance profile. It offers the optimum performance among the compared structures, making it well-suited for biomedical IoT applications where energy efficiency and precision are critical.

The summing amplifier is another essential block, responsible for virtual ground generation. In this design, a non-inverting summing amplifier configuration with capacitive feedback was used to combine the input signal and DAC feedback signal. The feedback and input capacitors were carefully sized to ensure signal stability and to maintain accuracy across the modulator’s operating range. By shifting the reference voltage to 1 V, the summing amplifier enables the integrator to handle input signals without requiring dual-supply circuits, thereby simplifying the design. The integrator, which is at the heart of noise shaping, was designed with a real integrator transfer function. The integrator uses the virtual ground as its reference point, allowing it to charge or discharge based on the input signal relative to the reference voltage. The resistor and capacitor values were carefully selected to achieve the desired cut-off frequency and ensure smooth signal processing. This design ensures efficient accumulation of the input signal while shaping quantization noise to higher frequencies. The binary quantizer is composed of a comparator and a D flip-flop. The comparator is implemented using a two-stage op-amp and detects differential voltages, converting them into a binary output. The D flip-flop, based on a master-slave architecture with clocked inverters, synchronizes the comparator output with the system clock. This synchronization ensures that the modulator produces a precise 1-bit digital stream for further processing by the digital filter. The complete modulator integrates all these blocks into a cohesive system. The summing amplifier combines the input signal and DAC feedback, the integrator accumulates the difference, and the comparator quantizes the output into a 1-bit stream. The flip-flop then synchronizes this output with the clock signal. The modulator operates with a clock frequency of 1.28 MHz, achieves an oversampling ratio of 128, and processes signals within a low bandwidth of 0–5 kHz. This integrated design ensures accurate signal conversion while maintaining low power consumption, making it highly suitable for IoT applications.

Proposed digital filter design

The digital filter in the \(\Sigma\)-\(\Delta\) ADC processes the high-frequency bitstream generated by the modulator. Figure 6 shows the proposed architecture of a CIC filter designed for this purpose. The CIC filter comprises two integrator stages, a decimator, and two differentiator stages. The first integrator employs a counter and a delay element (\(z^{-1}\)) to compute the cumulative sum of input samples, while the second integrator uses a traditional adder and register array for additional accumulation. This counter-based design in the first stage reduces power consumption and silicon area compared to traditional implementations. Following the integrators, the decimation block reduces the sampling rate by the oversampling ratio (OSR). This is followed by the differentiator stages, characterized by the transfer function \(H_{comb}(z) = 1 - z^{-OSR \cdot M}\), which remove low-frequency components and refine the signal. Each differentiator uses an adder and a delay element (\(z^{-1}\)) to compute the difference between successive samples. This design implements a second-order CIC filter optimized for oversampled systems like the \(\Sigma\)-\(\Delta\) ADC.

The CIC filter is a multiplierless linear-phase Finite Impulse Response (FIR) filter, widely used for sample rate conversion (SRC) in digital communication systems. Its architecture is particularly effective for high-sampling-rate applications such as digital downconversion. The CIC filter consists of two primary sections: the integrator and the comb, connected via a decimator. The integrator is a first-order Infinite Impulse Response (IIR) filter, and its operation is described by the difference equation, approximated by Eq. 6:

where \(x[n]\) is the input signal and \(y[n]\) is the output. The corresponding transfer function of the integrator is given by Eq. 7:

The frequency response of the integrator section is expressed by Eq. 8:

The phase response is described by Eq. 9:

and the group delay is approximated by Eq. 10:

The comb section, operating at a reduced sampling rate, is defined by the difference equation in Eq. 11:

where \(OSR\) is the decimation factor, and \(M\) is the differential delay, typically set to 1 or 2. The corresponding transfer function of the comb section is described by Eq. 12:

The differentiator stages in the CIC filter serve to remove low-frequency components and refine the signal by acting as high-pass filters. Each differentiator computes the difference between successive samples, effectively canceling out slowly varying or DC components in the signal. This process sharpens the signal transitions and reduces low-frequency quantization noise. Mathematically, the transfer function of a differentiator is given by Eq. 12. This function introduces a spectral null at DC and attenuates low-frequency components, enhancing the selectivity of the overall CIC filter. When cascaded, the differentiator stages significantly improve the stopband attenuation, thereby refining the digital output by suppressing residual low-frequency noise artifacts introduced during modulation.

The frequency response of the comb section is given by Eq. 13:

The phase response is defined by Eq. 14:

and the group delay is approximated by Eq. 15:

The complete CIC filter is formed by cascading \(N = 2\) integrator and comb sections. The resulting transfer function is expressed by Eq. 16:

where \(OSR\) is the decimation ratio, \(M\) is the number of samples per stage, and \(N\) is the number of cascaded stages.

This design enables efficient sample rate conversion by combining integrator and comb operations in a multiplier-free architecture, minimizing hardware complexity and power consumption. The decimator block reduces the sampling rate of the bitstream from the modulator. It uses a frequency divider to generate a lower clock frequency for the differentiator stages. This downsampling is essential for converting the high-frequency bitstream into a manageable data rate. The decimator design employs a simple clock division circuit with delay flip-flops, ensuring minimal power consumption and precise timing. The differentiators, also referred to as comb stages, subtract consecutive samples to suppress high-frequency quantization noise. The digital subtraction is performed using a 2’s complement binary adder, with one input inverted and the carry-in set to high. The differentiator stages are designed with bit widths that decrease progressively as the signal transitions through the stages, reducing hardware requirements without compromising accuracy.

Excel-based simulation of the CIC filter. The simulation demonstrates the operation of integrator and differentiator stages for an OSR of 128. The bit-width calculations for each stage are shown, along with the resolution (14 bits) and the difference output (\(CIC_{out}\)) plotted graphically for visualization.

Design methodology for CIC filter

The design of the CIC filter is initiated through simulations performed in Excel, as shown in Fig. 7. This simulation-based approach helped analyze the relationship between the output resolution, oversampling ratio (OSR), and CIC filter order. The resolution of the CIC filter is mathematically expressed as Eq. 17:

Given a sampling frequency (\(F_s\)) of 1.28 MHz and an output frequency (\(F_{\text {out}}\)) of 10 kHz, an OSR of 128 was selected. Using a 2nd-order CIC filter, the achievable resolution was calculated as Eq. 18:

The design of the CIC filter further requires determining the bit-width of registers and the size of integrators and differentiators, which depend on the OSR and the filter order.

Register and stage size calculation

-

1.

Integrator 1: The bit-width for the first integrator is determined as Eq. 19:

$$\begin{aligned} \text {Bits} = 14 + \log _2(128) = 14 + 7 = 21 \, \text {bits} \end{aligned}$$(19) -

2.

Integrator 2: The bit-width for the second integrator is calculated by adding the bit-width of the first integrator to \(\log _2(\text {OSR})\) as Eq. 20:

$$\begin{aligned} \text {Bits} = 21 + \log _2(128) = 21 + 7 = 28 \, \text {bits} \end{aligned}$$(20) -

3.

Differentiator 1: For the first differentiator, the bit-width reduces by \(\log _2(\text {OSR})\) as Eq. 21:

$$\begin{aligned} \text {Bits} = 28 - \log _2(128) = 28 - 7 = 21 \, \text {bits} \end{aligned}$$(21) -

4.

Differentiator 2: The bit-width for the second differentiator further reduces as Eq. 22:

$$\begin{aligned} \text {Bits} = 21 - \log _2(128) = 21 - 7 = 14 \, \text {bits} \end{aligned}$$(22)

Saturation and reset mechanism

To ensure the robustness of the CIC filter, a filter-wide reset mechanism is implemented to handle the saturation of integrators. When saturation occurs, the filter is reset to prevent erroneous outputs and maintain stability in the operation. This methodology establishes a systematic approach for determining the key design parameters of a CIC filter, ensuring it meets resolution and operational requirements for specific applications.

Results and discussion

This section evaluates the performance of the proposed \(\Sigma\)-\(\Delta\) ADC design, focusing on its individual components, including operational amplifiers, the \(\Sigma\)-\(\Delta\) modulator, and the CIC filter. The results highlight the effectiveness of the novel design strategies in achieving energy efficiency and high resolution. Simulations are conducted using the 180 nm technology node in the Cadence Virtuoso environment. Key performance metrics, including the SNR, effective number of bits (ENOB), and power consumption, are evaluated to benchmark the design against conventional approaches.

The discussion also includes the implications of the proposed techniques for power-constrained IoT applications and their impact on ADC performance.

Modulator output for a 0.5 V DC input. Refer to the block diagram in Fig. 2 for waveform label details.

Modulator output for 0 V dc input. Refer to the block diagram in Fig. 2 for waveform label details.

Modulator output for 1 V dc input. Refer to the block diagram in Fig. 2 for waveform label details.

Modulator output for Sinusoidal input. Refer to the block diagram in Fig. 2 for waveform label details.

The transient analysis (gain, and phase plot) of the folded-cascode amplifier is presented in Fig. 8. This architecture (Fig. 4a) was selected due to its ability to achieve a high DC gain of 76 dB, a unity-gain bandwidth (UGB) of over 100 MHz, and a phase margin of \(56^\circ\). The folded-cascode topology is further enhanced with a Wide-Swing Cascode Current Mirror (WSCCM), which improves voltage headroom, output resistance, and linearity. The amplifier’s design ensures precise biasing through the WSCCM and uses a common-mode feedback circuit to maintain stability across varying process corners. While this amplifier provides excellent performance, it consumes approximately 250 \(\upmu \hbox {W}\) of power, making it suitable for applications requiring high stability but less ideal for power-constrained environments such as IoT devices. The transient analysis of two-stage amplifier (Fig. 4b), depicted in Fig. 9, addresses the power constraints of IoT applications by reducing power consumption while maintaining adequate gain and bandwidth. The architecture consists of a differential cascode-loaded first stage and a common-source amplifier as the second stage, achieving a DC gain of 80.5 dB, a UGB of 101 MHz, and a phase margin of \(64^\circ\). While the output swing (1.45 V) and stability are slightly compromised compared to the folded-cascode design, this two-stage amplifier significantly reduces power consumption to just 72 \(\upmu \hbox {W}\). The circuit employs a Miller compensation technique to stabilize the inherently unstable two-stage topology, optimizing the phase margin for robust performance.

This design achieves an optimal balance between performance and energy efficiency, making it highly suitable for portable and battery-powered devices in IoT applications. Its performance is compared with state-of-the-art designs available in the literature, as summarized in Table 2. Table 3 presents the detailed results of PVT (Process, Voltage, Temperature) corner simulations for the proposed folded-cascode and two-stage operational amplifiers. Simulations were performed across all standard process corners (TT, SS, FF, SF, FS), a supply voltage range of \(\pm 10\%\) around the nominal 1.8 V (i.e., 1.62–1.98 V), and temperatures from – 40 to \(85\,^{\circ }\textrm{C}\).

Figure 10 presents the results of Monte Carlo simulations (500 runs) illustrating the statistical distribution of key performance metrics gain, phase margin, and power consumption for Folded-Cascode and Two-Stage amplifier designs under PVT (Process, Voltage, and Temperature) variations. The top row (A-C) corresponds to the Folded-Cascode amplifier, while the bottom row (D-F) corresponds to the Two-Stage amplifier. Plots (A) and (D) show the gain distribution, where the Folded-Cascode design centers around 76 dB and the Two-Stage design around 80-81 dB, with the latter exhibiting a slightly wider spread. Plots (B) and (E) depict the phase margin, with the Folded-Cascode showing a peak near \(56^\circ\) and the Two-Stage amplifier centered around \(64^\circ\), indicating better phase stability for the latter. Plots (C) and (F) represent power consumption, with the Folded-Cascode amplifier drawing higher power (\(\sim 250\) \(\mu \hbox {W}\)) compared to the Two-Stage amplifier (\(\sim 70\) \(\mu \hbox {W}\)), which also demonstrates a narrower distribution. These results emphasize the improved power efficiency and phase margin robustness of the Two-Stage design, while the Folded-Cascode architecture offers competitive gain performance.

Moreover, Table 4 presents an alternative choice of an op-amp, specifically a dynamic comparator, for the quantizer circuit. In quantizer circuits, replacing operational amplifier with these comparators can significantly reduce power consumption while maintaining or improving performance. This approach leverages the advantages of comparators, such as lower transistor count and reduced complexity, to achieve efficient analog-to-digital conversion. Among the designs analyzed, the Footless comparator emerges as the best choice for such applications, providing a balanced trade-off between power efficiency, speed, and noise performance. The comparative analysis of the performance parameters indicates that the Footless Comparator demonstrates superior overall efficiency and performance compared to other designs. With a power consumption of just 4.74 \(\upmu \hbox {W}\), it achieves one of the lowest energy per comparison values 0.82 pJ while maintaining minimal delay 173.2 ps at a supply voltage of 1.8 V. Furthermore, it exhibits the lowest kickback noise 10.005 \(\upmu \hbox {W}\)A, ensuring reduced interference in sensitive applications. The equivalent input noise 0.451 \(\hbox {mV/}\sqrt{Hz}\) is also competitive, showcasing its ability to handle low-noise requirements effectively. These attributes make the Footless Comparator particularly well-suited for high-speed, low-power applications, especially in biomedical and IoT systems where efficiency is paramount.

In this design, a \(\Sigma\)-\(\Delta\) modulator is implemented with the input signal to the ADC restricted to positive values, ranging from 0 to 1 V. However, the 1-bit DAC in the feedback loop is required to generate feedback voltages of either -1 V or 1 V, assuming a reference voltage of 0 V. Generating negative voltages in single-ended supply circuits is highly complex, so a virtual ground was introduced at 1 V to address this challenge. By shifting the integrator’s reference voltage to 1 V, the feedback output from the DAC is also shifted by 1 V. Consequently, when the DAC output is 0 V, the integrator input ranges from 0 to 1 V, and when the DAC output is 1 V, the input shifts to a range of 1 to 2 V. To achieve this functionality, a summing amplifier is used in place of a traditional difference amplifier. For instance, when the input signal is 0.7 V, the output of the summing amplifier becomes either 0.7 V or 1.7 V, depending on the DAC output. Since the integrator’s reference point is set at 1 V, it charges when the summing amplifier’s output exceeds 1 V (e.g., 1.7 V) and discharges when the output is below 1 V (e.g., 0.7 V). The difference between the reference voltage and the summing amplifier’s output determines the rate of charging or discharging of the integrator capacitor. This dynamic adjustment results in a varying density of 1s and 0s in the output bitstream, which accurately corresponds to the amplitude of the input signal.

A second-order CIC filter (sinc2 filter) has been employed in this design, comprising two integrators, a decimator, and two differentiators (combs). The data rate of the filter is determined by the modulator rate and the oversampling ratio (OSR). With a modulator clock frequency of 1.28 MHz, a sinc filter order of 2, and an OSR of 128, the data rate is calculated to be 10 kHz. The latency, which is the amount of time required to deliver the correct output, is determined by the filter order and data rate, resulting in a latency of 0.2 ms. While sinc filters are non-ideal low-pass filters with passbands, stopbands, and ripples in the stopband, higher-order filters such as sinc2 reduce these ripples, enhancing resolution compared to lower-order filters like sinc1. The sinc2 filter in this design averages 256 samples per output, doubling the latency of a sinc1 filter that averages 128 samples. The frequency responses of first-order (sinc1) and second-order (sinc2) CIC filters are shown in Figure 11. The sinc1 filter exhibits higher ripple in the stopband, while the sinc2 filter significantly reduces the ripple at the cost of increased latency. The normalized frequency plot demonstrates the effectiveness of the second-order filter in suppressing high-frequency components, which is critical for achieving high-resolution digital outputs. CIC filters were selected due to their efficient decimation, combining filtering and downsampling in one structure, their multiplier-free architecture relying only on adders and subtractors, and their ability to handle high-rate data from sigma-delta ADCs effectively while reducing high-frequency quantization noise. The use of a counter-based integrator in the first stage further reduces power consumption and silicon area, ensuring the filter meets the stringent power and performance requirements of IoT applications. This simplified, noise-reducing, and energy-efficient design supports the \(\Sigma\)-\(\Delta\) ADC in delivering accurate and high-resolution digital outputs suitable for biomedical devices.

The presented waveforms illustrate the behavior of a \(\Sigma\)-\(\Delta\) modulator when processing both DC and sinusoidal input signals. The modulator generates a bitstream of 0s and 1s, where the density of 1s in the stream reflects the amplitude of the input signal. As the input signal varies between 0 V and 1 V, the modulator adjusts the density of 1s dynamically to encode the input. Figure 12 demonstrates the modulator’s response to a 0.5 V DC input signal. In this case, the bitstream alternates between 0s and 1s at the clock frequency, maintaining an average density indicative of the 0.5 V input amplitude. Figures 13 and 14 show the modulator’s behavior for 0 V and 1 V DC input signals, respectively. For a 0 V input, the bitstream predominantly consists of 0s, indicating minimal density of 1s. Conversely, for a 1 V input, the output is dominated by 1s, reflecting maximum density. Furthermore, the modulator’s response to a sinusoidal input signal is shown in Fig. 15. Here, the bit density varies dynamically as the sinusoidal input oscillates between its peak and trough values. The bit density increases during the positive half-cycles of the sinusoidal signal, representing a higher proportion of 1s, while decreasing during the negative half-cycles, where 0s dominate. This demonstrates the modulator’s ability to track and encode time-varying input signals effectively. In all cases, the waveform labeled Q represents the final modulator output. The initial stages of the output exhibit a lower density of 1s, with a higher count of 0s. Over time, the output dynamically adjusts to accurately represent the input signal’s amplitude or variations, as observed in both the DC and sinusoidal cases. This adaptive bit density highlights the modulator’s capability to encode both static and dynamic input signals through a varying density of 1s and 0s in its output stream.

Figure 16 presents key performance characteristics of the \(\Sigma\)-\(\Delta\) ADC. Figure 16a illustrates the relationship between the SNR and the OSR for first-, second-, and third-order modulators. Higher-order modulators achieve a steeper SNR improvement with increasing OSR. A specific data point is highlighted at OSR = 128, where an SNR of 89.5 dB is achieved for the second-order modulator, as indicated by the red marker. Figure 16b displays the power spectral density (PSD) of the modulator output across a range of frequencies. The noise shaping characteristic of the \(\Sigma\)-\(\Delta\) ADC is visible, where quantization noise is effectively pushed towards higher frequencies. The peak at lower frequencies represents the input signal, while the shaped noise floor increases at higher frequencies. This spectral analysis validates the effectiveness of noise shaping, which is crucial for achieving high-resolution conversion after digital filtering and decimation. Figure 17 illustrates the post-layout view of the implemented Sigma-Delta ADC in the 180-nm CMOS process. The left side of the figure shows the top-level chip layout with clearly marked I/O pads, including power (VDD), ground (GND), input, and output pads, as well as dummy insertion for symmetry. The right-hand side provides a zoomed-in view of the active circuit area, where the top portion highlights the Sigma-Delta modulator, and the bottom part shows the decimation filter. The core layout occupies an area of \(320~\mu \text {m} \times 280~\mu \text {m}\). Figure 18 illustrates the power distribution among various components in the system. The majority of the power is consumed by op-amps, indicating their significant role in the overall power budget. The clock driver and oscillator also contribute notably to the power consumption, highlighting the impact of clocking circuits on energy efficiency. Other key contributors include digital circuits, comparators, and DACs, each playing a role in the system’s functionality. A smaller fraction of the power is attributed to other miscellaneous components, which together form the remaining share of power utilization. This breakdown provides insight into the dominant power-consuming blocks, emphasizing areas where optimization efforts can be focused for improved efficiency. Table 5 provides a comparative analysis of \(\Sigma\)-\(\Delta\) ADCs, highlighting key parameters such as technology node, modulator order, sampling frequency, SNR, ENOB, power consumption, and FoM. It showcases the trade-offs between performance and energy efficiency across different designs, helping assess the suitability of ADC architectures for low-power and high-precision applications.

Conclusion

This paper presents a novel low-power, energy-efficient \(\Sigma\)-\(\Delta\) ADC optimized for biomedical IoT applications. The proposed design, implemented in a 180 nm technology node, integrates a second-order modulator and a Cascaded Integrator Comb (CIC) filter, ensuring high efficiency. In the modulator part, the hybrid use of a folded-cascode amplifier with Wide-Swing Cascode Current Mirror biasing and a two-stage amplifier balances precision, stability, and power efficiency. Monte Carlo simulations for 500 runs with PVT (Process, Voltage, Temperature) variations confirm robust operation across process corners and mismatch conditions. The \(\Sigma\)-\(\Delta\) modulator achieves a high SNR of 84.8 dB, an ENOB of 13.995 bits, and a competitive FoM of 20.41 fJ/conversion at a power consumption of just 498 \(\mu\)W. To further reduce power consumption in the modulator, various dynamic comparator topologies for the quantizer circuit are presented. In this work, we have done the simulation of these present state-of-the-art comparators. In the filter part, the adoption of a counter-based integrator in the CIC filter reduced digital power by approximately 30% while maintaining 14-bit resolution at a 10 kHz output rate. The post-layout area occupies \(320~\mu \text {m} \times 280~\mu \text {m}\) in the 180-nm CMOS process. Overall, this work demonstrates a compact and low-power ADC architecture that meets the stringent requirements of wearable biomedical systems. Future directions include exploring higher-order modulators and advanced CMOS nodes for further performance gains.

Data availability

Data is provided within the manuscript.

Abbreviations

- AFE:

-

Analog front end

- CIC:

-

Cascaded integrator comb

- DAC:

-

Digital-to-analog converter

- ECG:

-

Electrocardiogram

- EEG:

-

Electroencephalogram

- EMG:

-

Electromyogram

- ENOB:

-

Effective number of bits

- EOG:

-

Electrooculogram

- FIR:

-

Finite impulse response

- FOM:

-

Figure-of-merit

- \(F_D\) :

-

Output data rate

- \(F_S\) :

-

Sampling frequency

- IIR:

-

Infinite impulse response

- IoT:

-

Internet of things

- Op-Amp:

-

Operational amplifier

- OSR:

-

Oversampling ratio

- PPG:

-

Photoplethysmogram

- SCG:

-

Seismocardiogram

- SNR:

-

Signal-to-noise ratio

- \(\Sigma\)-\(\Delta\) ADC:

-

Sigma-delta analog-to-digital converter

- WSCCM:

-

Wide-swing cascode current mirror

References

Tenoudji, F. C. Analog and digital signal analysis (Springer, 2016).

Sharma, B. P., Sarma, I., Gupta, A. & Shekhar, C. A 12.11 mw, 99 pj/conv.-step sar adc with optimal power efficiency for iot. In 2024 IEEE Industrial Electronics and Applications Conference (IEACon), 236–240 (IEEE, 2024).

Sharma, B. P., Gupta, A. & Shekhar, C. Data converter design space exploration for IoT applications: An overview of challenges and future directions 111–130 (Springer, 2023).

Lin, J., Mano, I., Miyahara, M. & Matsuzawa, A. Ultralow-voltage high-speed flash adc design strategy based on fom-delay product. IEEE Trans. Very Large Scale Integr. (VLSI) Syst. 23, 1518–1527 (2014).

Chiu, Y., Gray, P. R. & Nikolic, B. A 14-b 12-ms/s cmos pipeline adc with over 100-db sfdr. IEEE J. Solid-State Circuits 39, 2139–2151 (2004).

Sharma, B. P., Peelam, M. S., Gupta, A., Shekhar, C. & Chamola, V. A comprehensive survey on data converters for iot applications: Scope, issues and future directions. IEEE Internet Things J. https://doi.org/10.1109/JIOT.2025.3553153 (2025).

Barros, M. F., Guilherme, J. M. & Horta, N. C. Analog circuits and systems optimization based on evolutionary computation techniques Vol. 9 (Springer, 2010).

Verreault, A., Cicek, P.-V. & Robichaud, A. Oversampling adc: A review of recent design trends. IEEE Access (2024).

Raikar, A. S. et al. Neuromorphic computing for modeling neurological and psychiatric disorders: implications for drug development. Artif. Intell. Rev. 57, 318 (2024).

Maron, B. J. et al. Assessment of the 12-lead electrocardiogram as a screening test for detection of cardiovascular disease in healthy general populations of young people (12–25 years of age) a scientific statement from the American Heart Association and the American College of Cardiology. J. Am. Coll. Cardiol. 64, 1479–1514 (2014).

Kerwin, L. J., Keller, C. J., Wu, W., Narayan, M. & Etkin, A. Test-retest reliability of transcranial magnetic stimulation eeg evoked potentials. Brain Stimul. 11, 536–544 (2018).

Béres, S. & Hejjel, L. The minimal sampling frequency of the photoplethysmogram for accurate pulse rate variability parameters in healthy volunteers. Biomed. Signal Process. Control 68, 102589 (2021).

Pamula, V. R., Hoof, C. & Verhelst, M. Analog-and-algorithm-assisted ultra-low power biosignal acquisition systems (Springer, 2019).

Miranda, J. A., Canabal, M. F., Gutiérrez-Martín, L., Lanza-Gutiérrez, J. M. & López-Ongil, C. A design space exploration for heart rate variability in a wearable smart device. In 2020 XXXV Conference on Design of Circuits and Integrated Systems (DCIS), 1–6 (IEEE, 2020).

Yan, F. & Liu, J. Analog front-end input-impedance boosting techniques for bio-potential monitoring-a review. IEEE Trans. Instrum. Meas. (2024).

Xiao, Z. et al. An implantable rfid sensor tag toward continuous glucose monitoring. IEEE J. Biomed. Health Inform. 19, 910–919 (2015).

Sinex, J. E. Pulse oximetry: principles and limitations. Am. J. Emerg. Med. 17, 59–66 (1999).

Kwon, K. et al. A battery-less wireless implant for the continuous monitoring of vascular pressure, flow rate and temperature. Nat. Biomed. Eng. 7, 1215–1228 (2023).

Li, C. et al. Brain temperature measurement: A study of in vitro accuracy and stability of smart catheter temperature sensors. Biomed. Microdevice 14, 109–118 (2012).

Benning, M., Boyd, S., Cochrane, A. & Uddenberg, D. The experimental portable eeg/emg amplifier. ELEC 499A Report, University of Victoria, Faculty of Engineering (2003).

Gupta, R. Biomedical sensors and data acquisition. In Health Monitoring Systems, 19–56 (CRC Press, 2019).

Paul, A., Lee, M. S., Xu, Y., Deiss, S. R. & Cauwenberghs, G. A versatile in-ear biosensing system and body-area network for unobtrusive continuous health monitoring. IEEE Trans. Biomed. Circuits Syst. 17, 483–494 (2023).

Egorova, M., Akimov, A. & Khorunzhii, G. Time scale of adaptation at the tonal sequence processing in the awake mice auditory cortex neurons. J. Evol. Biochem. Physiol. 60, 332–341 (2024).

Gao, F. et al. Feasibility of oscillating and pulsed gradient diffusion mri to assess neonatal hypoxia-ischemia on clinical systems. J. Cerebral Blood Flow Metab. 41, 1240–1250 (2021).

Kocharyan, A., Fernandes, P., Tong, X.-K., Vaucher, E. & Hamel, E. Specific subtypes of cortical gaba interneurons contribute to the neurovascular coupling response to basal forebrain stimulation. J. Cerebral Blood Flow Metab. 28, 221–231 (2008).

Li, H. et al. E-tattoos: Toward functional but imperceptible interfacing with human skin. Chem. Rev. 124, 3220–3283 (2024).

Shin, B. et al. All-in-one wearable drug efficacy assessment systems for bulbar muscle function using amyotrophic lateral sclerosis animal models. Nat. Commun. 15, 6803 (2024).

Vranic, I. I. Characterization of cardiac electrophysiology including ecg-analysis. Drug Discov. Eval. Methods Clin. Pharmacol. 51–80 (2020).

Chatterjee, B. Energy-Efficient Sensing and Communication for Secure Internet of Bodies (IOB). Ph.D. thesis, Purdue University (2022).

Idler, W. & Buchali, F. Higher-order modulation formats–concepts and enabling devices. Fibre Opt. Commun. Key Devices 291–357 (2017).

Dinis, H. & Mendes, P. A comprehensive review of powering methods used in state-of-the-art miniaturized implantable electronic devices. Biosens. Bioelectron. 172, 112781 (2021).

Chinnapparaj, S. Certain investigations on design and implementation of digital fir filter using low power and high speed multipliers. Ph.D. thesis, ANNA UNIVERSITY CHENNAI (2019).

Aledhari, M., Razzak, R., Qolomany, B., Al-Fuqaha, A. & Saeed, F. Biomedical iot: enabling technologies, architectural elements, challenges, and future directions. IEEE Access 10, 31306–31339 (2022).

Shafik, W. Smart biomedical devices for smart healthcare. In Machine Learning Models and Architectures for Biomedical Signal Processing, 421–448 (Elsevier, 2025).

Nyamathulla, S. & Dhanamjayulu, C. A review of battery energy storage systems and advanced battery management system for different applications: Challenges and recommendations. J. Energy Storage 86, 111179 (2024).

Vaezi, M. et al. Cellular, wide-area, and non-terrestrial iot: A survey on 5g advances and the road toward 6g. IEEE Commun. Surv. Tutor. 24, 1117–1174 (2022).

Zhang, D., Zuo, W. & Wang, P. Computational pulse signal analysis (Springer, 2018).

Sharma, B. P., Gupta, A. & Shekhar, C. Design & analysis of performance-efficient comparator for iot application. In 2022 IEEE 9th Uttar Pradesh section international conference on electrical, electronics and computer engineering (UPCON), 1–6 (IEEE, 2022).

Sharma, B. P. et al. Design and analysis of modified strong arm latch comparator with reduced kickback noise. In International Symposium on VLSI Design and Test, 317–329 (Springer, 2023).

Zhuang, H., Cao, W., Peng, X. & Tang, H. A three-stage comparator and its modified version with fast speed and low kickback. IEEE Trans. Very Large Scale Integr. (VLSI) Syst. 29, 1485–1489 (2021).

Miyahara, M., Asada, Y., Paik, D. & Matsuzawa, A. A low-noise self-calibrating dynamic comparator for high-speed adcs. In 2008 IEEE Asian Solid-State Circuits Conference, 269–272 (IEEE, 2008).

Sharma, B. P., Rajagopal, R., Sekhar, R., Gupta, A. & Shekhar, C. A three-stage dynamic comparator for sar adc optimized for reduced kickback noise and ultra-low delay. J. Circuits Syst. Comput. 2550063 (2024).

Schlogl, F. & Zimmermann, H. 1.5 ghz opamp in 120nm digital cmos. In Proceedings of the 30th European Solid-State Circuits Conference, 239–242 (IEEE, 2004).

Sharma, B. P. & Mehra, R. Design of cmos instrumentation amplifier with improved gain & cmrr for low power sensor applications. In 2016 2nd International Conference on Next Generation Computing Technologies (NGCT), 72–77 (IEEE, 2016).

Aparna, T., Polineni, S. & Bhat, M. A three-stage operational transconductance amplifier for delta sigma modulator. In 2018 IEEE Distributed Computing, VLSI, Electrical Circuits and Robotics (DISCOVER), 152–157 (IEEE, 2018).

Bonthala, S., Uppoor, Y., Nayak, A., Polineni, S. & Bhat, M. Design of high resolution delta sigma modulator in 180 nm cmos technology. In 2019 9th International Symposium on Embedded Computing and System Design (ISED), 1–6 (IEEE, 2019).

Fazli Yeknami, A. A 300-mv \(\delta\)\(\sigma\) modulator using a gain-enhanced, inverter-based amplifier for medical implant devices. J. Low Power Electron. Appl. 6, 4 (2016).

Basak, D., Li, D. & Pun, K.-P. A gm-c delta-sigma modulator with a merged input-feedback gm circuit for nonlinearity cancellation and power efficiency enhancement. IEEE Trans. Circuits Syst. I Regul. Pap. 65, 1196–1209 (2017).

Han, J.-H. et al. A 96db dynamic range 2khz bandwidth 2nd order delta-sigma modulator using modified feed-forward architecture with delayed feedback. IEEE Trans. Circuits Syst. II Express Briefs 68, 1645–1649 (2021).

Baluni, A. & Pavan, S. Analysis and design of a 20-mhz bandwidth continuous-time delta-sigma modulator with time-interleaved virtual-ground-switched fir feedback. IEEE J. Solid-State Circuits 56, 729–738 (2020).

Cho, Y.-K. A single op-amp resonator-based continuous-time sigma-delta modulator with time-division switching for excess loop delay compensation (Express Briefs, IEEE Transactions on Circuits and Systems II, 2023).

Acknowledgements

The author sincerely thanks Prof. Sudhir Kumar Barai, Director of BITS Pilani, Prof. Navneet Gupta, Head of the EEE Department, Prof. Abhijit Asati and Prof. Nitin Chaturvedi, EEE Department, for their continuous support and guidance throughout this research. The authors also acknowledge the “Chips to Startup (C2S)” program, a national initiative by the Ministry of Electronics and Information Technology (MeitY), Government of India, through which Cadence EDA tools and supporting infrastructure were made available for academic research and innovation.

Funding

The authors declare that no funding was received for the above work.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

Buddhi Prakash Sharma: Original draft writing, methodology, conceptualization. Anu Gupta: Results analysis, resources, supervision. Chandra Shekhar: Supervision, resources, manuscript review. Raman Chauhan: Literature review & data curation. Vinay Chamola: Review & editing.

Corresponding authors

Ethics declarations

Competing Interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher’s note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if you modified the licensed material. You do not have permission under this licence to share adapted material derived from this article or parts of it. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Sharma, B.P., Gupta, A., Shekhar, C. et al. Design of low power energy efficient sigma-delta ADC for biomedical IoT applications. Sci Rep 15, 36165 (2025). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-19272-4

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-19272-4